Abstract

Endophytic fungi play a crucial role in plant health, contributing to stress tolerance, disease resistance, and ecological adaptation. However, the diversity and richness of endophytic fungal communities associated with Capparis spinosa L. in the Alborz, Tehran, and Qom provinces—ranging from semi-arid and slightly temperate to arid and desert climatic conditions—have not yet been investigated. Using morphological and molecular methods, we identified a diverse fungal assemblage comprising 3 phyla, 7 classes, 14 orders, 28 families, and 36 genera. Among the genera shared across all three provinces, Alternaria (28.8%) was the most dominant among the isolates, whereas Simplicillium (1.6%) was the least abundant. Analysis of the isolates using diversity indices revealed that species distribution in all three provinces tended toward evenness, with a similar pattern observed across different tissues. Qom exhibited the highest diversity and richness of fungal species. Additionally, a detailed comparison of different plant tissues revealed that roots consistently harbored the greatest variety and the highest number of isolates compared to stems, leaves, and fruits. Diversity metrics suggest a potential link between climatic gradients and endophyte diversity. These findings enhance our understanding of fungal-plant interactions and provide insights into the microbial contributions to C. spinosa resilience in harsh environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants are complex ecosystems that host diverse microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses1. Among these are endophytic fungi that live symbiotically within plant tissues without causing harm. These fungi, present in numerous plant species, enhance growth and resistance to stress and produce bioactive compounds2. Moreover, their diverse distribution is influenced by both the host plant species and the environment in which they thrive3. Despite their evolutionary diversity, only approximately 150,000 of the estimated three million fungal species have been identified, highlighting untapped research opportunities4.

The genus Capparis, established by Linnaeus in 1753, belongs to the Capparidaceae family and comprises 350 species, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions. C. spinosa, a hybrid of C. orientalis Veill. and C. sicula Veill., thrives across diverse regions from the Canary Islands to Iran, North Africa, Europe, and beyond. With its robust root system, this plant adapts to varied environments, including arid, sandy, and nutrient-poor soils5,6.

Endophytic fungi, harmlessly residing within plant tissues, are essential for ecosystem health and stability. Their diversity and population are shaped by host traits, interactions within plant parts, and environmental factors7. Climate change endangers global agriculture, causing abiotic stresses like drought and salinization that reduce productivity. An integrative approach, including the use of endophytes, particularly endophytic fungi, offers potential solutions to mitigate these stresses8. Endophytic fungi enhance root function, increasing water and nutrient absorption, particularly under water stress. They regulate plant growth and boost resilience to environmental challenges9. Furthermore, the diversity and functional roles of root-associated endophytic fungi contribute to promoting plant vitality under adverse conditions10. Endophytic fungi contain bioactive compounds with vital health benefits, such as antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects, derived from components like flavonoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids. Medicinal plants provide ideal conditions for endophytic fungi, enabling the production of unique bioactive substances11,12.

Given C. spinosa’s resilience in challenging environments and its medicinal properties, it is crucial to investigate its largely unexplored endophytic fungi. Studying these fungi is vital for understanding the symbiotic relationships that bolster plant health and resilience. The objectives of this study included: (a) isolation of endophytic fungi from C. spinosa growing in Iran using culture-dependent methods, (b) identification of the isolated endophytic fungi from various plant organs using morphological and molecular methods, and (c) investigation of the impact of diverse tissues and geographical locations on the endophytic fungal communities.

Results

Isolation and taxonomic study of endophytic fungi

No fungal growth was detected on PDA (Potato dextrose agar) plates in the control group, confirming the effectiveness of the surface sterilization process. Therefore, all the fungi isolated in this study are confirmed to be endophytes, as pure single clones were successfully obtained from each tissue. In total, 711 endophytic fungal isolates were recovered from 1800 cultured tissue segments of C. spinosa collected from Alborz, Tehran, and Qom provinces. These isolates belonged to 3 phyla, 7 classes, 14 orders, 28 families, and 36 genera (Supplementary Fig. S1). After thoroughly examining the characteristics and growth patterns of the colonies, 76 distinct morphotypes were identified, reflecting the diversity among the total isolates (Supplementary Table S2, Fig. S2, S3). Relative abundance (RA%)of endophytic fungal isolates was determined by considering the number of isolates obtained from various tissues of C. spinosa across three different provinces: Qom, Alborz, and Tehran (Supplementary Fig. S4–S6). In Qom province, 243 isolates were obtained, resulting in a colonization frequency (CF) of 36.82% including 124 from root (75.15%), 80 from stem (48.48%), 35 from leaf (21.21%), and 4 from fruit (2.42%). In Alborz, 255 endophytic fungal isolates were obtained, with a CF of 42.50%. This includes 107 isolates from root (71.33%), 78 from stem (52.00%), 53 from leaf (35.33%), and 17 from fruit (11.33%). Similarly, from Tehran province, 213 strains were isolated, with a CF of 39.44%, consisting of 117 from root (86.67%), 58 from stem (42.96%), 34 from leaf (25.19%), and 4 from fruit (2.96%) (Supplementary Table S3). Alborz exhibited the highest CF at 42.50%, with the greatest number of endophytic fungal isolates (n = 255), followed by Tehran at 39.44% and Qom at 36.82%. Most isolates were obtained from the roots (n = 348), while the fruits yielded the fewest isolates (n = 25) (Supplementary Table S3).

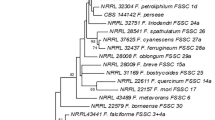

The morphological and molecular characterization of 243 endophytic fungi isolated from Qom province revealed that they belonged to three phyla: Ascomycota, Zoopagomycota, and Oomycota. These fungi were categorized into 7 classes, 12 orders, 22 families, and 27 genera. Among them, 237 (97.5%) endophytic fungal strains were in the phylum Ascomycota, distributed across the classes of Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Dothideomycetes, Pezizomycetes, and Leotiomycetes. Additionally, three strains (1.23%) were identified as Basidiobolomycetes from the phylum Zoopagomycota, and another three strains (1.23%) were classified as Peronosporomycetes from the phylum Oomycota (Fig. 1). Alborz province had 255 isolates, all classified within the Ascomycota phylum. These isolates are distributed across 3 classes, 6 orders, 12 families, and 13 genera (Fig. 2). The most strains were in the Dothideomycetes order (146 strains, 57.25%), followed by Sordariomycetes (60 strains, 23.52%) and Eurotiomycetes (49 strains, 19.21%). 213 endophytic fungi isolated from Tehran province belonged to Ascomycota phyla with 3 classes, 6 orders, 12 families, and 15 genera (Fig. 3).There were 93 (43.66%) strains in the Dothideomycetes, 74 strains (34.74%) in Eurotiomycetes, and Sordariomycetes with 46 strains (21.59%).

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S7, the genera Alternaria, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, and Simplicillium are present in all three provinces. Chaetosphaeronema, Cladosporium, Corynespora, Phoma, and Preussia are common between Qom and Tehran provinces. Chaetomium and Stilbocrea are shared between Qom and Alborz, while Devriesia and Neosetophoma are found in both Tehran and Alborz provinces. Additionally, Acremonium, Basidiobolus, Botryotrichum, Clarireedia, Coniothyrium, Lasiobolidium, Lophiostoma, Microascus, Neodidymelliopsis, Schizothecium, Paecilomyces, Pestalotiopsis, Phaeoacremonium, Phytophthora, and Stolonocarpus were exclusive to Qom province. Several genera were specific to Alborz (Acrocalymma, Diaporthe, Kalmusia, and Paramicrosphaeropsis) and Tehran (Bulbithecium, Myceliophthora, and Talaromyces) provinces. The fungal endophytes of Qom province exhibited the greatest abundance and variety.

Alpha diversity assessment of endophytic fungi in C. spinosa across Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces

Fungal species isolated from each tissue corresponding to each province are presented in Figs. 4, 5 and 6.

The Shannon–Wiener index (H) and Simpson dominance index (D) revealed that the endophytic fungal population recovered from each province exhibits the highest diversity in root (H = 3.34, D = 0.034; H = 2.886, D = 0.055; H = 3.084, D = 0.052 respectively, Qom Alborz, Tehran provinces), while the lowest diversity is observed in fruit in Alborz (H = 1.318, D = 0.243), and leaf tissue in Qom (H = 2.292, D = 0.076) and Tehran (H = 2.224, D = 0.89). These results indicate that the diversity of culturable endophytic fungi species in C. spinosa is significantly influenced by the type of plant tissue (Table 1).

Understanding the relationship between abundance and diversity in fungal endophytic communities is crucial. Figure 7 demonstrates that the frequency distribution of fungal endophyte species isolated from Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces align with a Poisson distribution.

Fisher’s alpha index is a highly valuable parametric measure that effectively determines species diversity within the framework of logarithmic series distribution models. The abundance of fungal endophyte species isolated from each province was calculated using Fisher’s series for root, stem, leaf, and fruit tissues (the dashed line shown in Fig. 7). The correlation between observed and calculated data for fungal endophytes isolated from various tissues in all three provinces was significant.

Fisher’s alpha index (Table 2) for all isolated fungal endophytes was 16.796 for Qom, 9.246 for Alborz, and 10.927 for Tehran province, indicating the highest diversity in Qom, followed by Tehran and Alborz provinces, respectively. Additionally, the highest diversity within each province was observed in root tissues, with values of 13.975 for Qom, 7.814 for Alborz, and 11.663 for Tehran. Conversely, the lowest diversity was recorded in fruit tissues, with values of 0.428 for both Qom and Tehran, and 1.648 for Alborz province.

Beta diversity analysis of endophytic fungi in different C. spinosa tissues across three provinces

The values of the classic Sorensen and Jaccard indices, used to compare the endophytic fungal species composition across different tissues within each province and between provinces, revealed several notable similarities. Specifically, the endophytic fungal species in the root and stem tissues in Qom province were highly similar. In Alborz, the leaf tissues exhibited significant similarity with both the root and fruit tissues. In Tehran, the stem tissues were similar to both root and leaf tissues. Additionally, notable similarities were observed between the stem tissues from Qom and the leaf tissues from Tehran, as well as between the stem tissues from Qom and the root tissues from Alborz. Lastly, the root tissues of Alborz province showed significant similarity with the root tissues of Tehran province (Supplementary Table S4).

Richness of the species

Supplementary Table S5 illustrates the total count of species (S) as a direct measure of species diversity. The greatest number of species was recovered from Qom, followed by Tehran and Alborz provinces. When examining the number of individuals within each province, it was observed that root tissues had the highest number of isolated endophytic fungi, whereas fruit tissues had the lowest number of isolates.

It is important to note that the S is influenced by the sample size, which limits its utility as a comparative index. To evaluate species richness more effectively, Margalef and Menhinick indices, renowned for their lack of reliance on sample size, were employed. The indices exhibited higher values for endophytic fungi obtained from Qom in contrast to those from Tehran and Alborz provinces. Within each province, root tissues demonstrated the highest species richness compared to other tissues, such as stem, leaf, and fruit. When comparing isolates from the three provinces, Qom displayed the lowest Berger–Parker dominance index, followed by Alborz province. This index, along with its reciprocal, demonstrated the highest dominance and lowest diversity in endophytic fungi isolated from the roots in Tehran province, followed by Alborz and Qom provinces (Tables 1 and 2).

The Chao metric revealed that the endophytic fungal community collected from Qom demonstrated the greatest species abundance at 48.250, with Alborz exhibiting the least at 31.000 (Table 1).

Species evenness

The species distribution in the fungal communities isolated from all tissues in each province is depicted in Supplementary Fig. S8–S10.

The evenness (E) values for Tehran, Alborz, and Qom provinces were 0.686, 0.738, and 0.802, respectively. These values suggest that species distribution in these provinces leans towards evenness. A similar trend was observed across the root, stem, leaf, and fruit tissues in each province. Additionally, the Pielou Evenness index (J) values mirrored this pattern. In Qom province, the Pielou index values for root, stem, and leaf tissues were 0.956, 0.942, and 0.996, respectively, indicating that leaf tissues exhibit the highest evenness in the fungal community. In Alborz province, the J values for root, stem, leaf, and fruit tissues were 0.948, 0.951, 0.931, and 0.951, respectively, showing that stem and fruit tissues have the highest evenness, while leaf tissues have the lowest. For Tehran province, the J values were calculated as 0.926 for root, 0.928 for stem, and 0.966 for leaf tissues, revealing that leaf tissues demonstrate the highest evenness within the fungal community. Camargo’s uniformity index was calculated for the fungal communities each province (Table 2). A uniform distribution of species was observed across all types of tissue in the provinces, particularly in the leaf tissues of all three provinces and the fruit tissues in Alborz province and the stem tissues in Tehran province.

The Simpson’s Dominance values for all isolates obtained from each province are close to zero, indicating a stable fungal community structure. This trend was consistent across the endophyte fungal communities of plant tissues in each province, except for fruit tissues in Qom and Tehran. Consequently, it can be inferred that the fungal community structure is stable across all three provinces, except for the fruit tissue in Qom and Tehran provinces (Table 1). According to Table 1, the endophytic fungal community is diverse in the studied areas. This conclusion is based on the analysis of all isolates from the three provinces and each tissue type within those provinces, except for fruit tissue in Qom and Tehran provinces.

Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was conducted using diversity indices for the endophytic fungal species community isolated from Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces. The results indicate that the data align well with the model. The first principal component (PC1) explains 93.31% of the variation, showing high dominance coefficients for the Camargo, Simpson, and Berger-Parker indices. The second principal component (PC2) accounts for 6.69% of the total variation, with the Menhinick index richness index displaying a high positive coefficient for this component. According to Fig. 8 (A), Tehran province demonstrates the highest species dominance, while Qom province exhibits the highest species richness and, consequently, the greatest species diversity. Based on these findings, the primary and secondary principal components can be interpreted as factors estimating dominance and richness, respectively.

Based on the same diversity indices, a dendrogram was constructed (Fig. 8B), showing that Qom and Alborz provinces exhibit greater similarity to each other, as they clustered together at a lower dissimilarity level. In contrast, Tehran province shows less similarity to Qom and Alborz, joining the cluster at a higher dissimilarity level. This analysis helps in understanding the overall structure and diversity within the endophytic fungal communities, providing insights into the diversity and distribution of these fungi across different regions.

Principal component analysis (A) and classification dendrogram (B) based on calculated diversity indices for fungal species from Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces.Chao, Chao richness estimator; DMg, Margalef diversity index; H′, Shannon–Wiener diversity index; D, Simpson dominance index; 1-D, Simpson diversity index; 1/D, Reciprocal of Simpson index; d, Berger–Parker dominance index; 1/d, Reciprocal of Berger–Parker index; J, Pielou evenness index; Dmn, Menhinick index; EC, Camargo index; E, Evenness_(e^H′)/S; Fisher alpha.

Community structuring and categorization

Cluster analysis, a tool for community classification, was used to examine the fungal communities in Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces, based on the Jaccard similarity index (Fig. 9). The dendrogram analysis indicates that Tehran and Alborz provinces are clustered together, while Qom has a distinct fungal community. This could indicate closer ecological relationships between Tehran and Alborz and a more unique environment in Qom province.

Specificity of community composition

Among the studied endophytic fungi, five common genera—Alternaria, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, and Simplicillium—were found across Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces. Of these, the genus Alternaria was the most abundant in all three provinces. Additionally, the specific genera isolated from each province suggest that the climate of each region significantly influences the fungal community associated with C. spinosa. A heat map (Fig. 10) and bar chart (Supplementary Fig. S11) were created based on the relative abundance of endophytic fungal genera and isolates from Qom, Alborz, and Tehran provinces at the genus level. In general, these analyses revealed that Qom province exhibited the highest frequency of fungal genera, followed by Tehran and Alborz provinces, respectively. This indicates that the diversity and presence of endophytic fungi are more prominent in Qom compared to the other studied regions. Furthermore, when examining the relative abundance of specific genera, it was found that Alternaria dominated the fungal community. Aspergillus and Fusarium were also relatively abundant but to a lesser extent than Alternaria.

In addition, PCA was used to analyze the data and visualize the fungal genus diversity patterns. The PCA chart (Supplementary Fig. S12) presents the distribution of endophytic fungi abundance. The PC1 accounts for 61.24% of the total variance, while the PC2 accounts for 38.76%. The findings suggest that among the prevalent genera in the three provinces, Alternaria stands out as the most abundant, showing a notably significant presence in Alborz province. This dominance underscores the significant role of Alternaria in the fungal community of this region. Additionally, out of the 36 genera identified in this study, 15 were exclusively found in Qom province. This finding highlights the distinct regional differences in fungal diversity.

Discussion

The present study is unique because it reveals significant variations in endophytic fungal communities across different plant tissues and regions, providing valuable insights into the ecological and functional roles of these fungi. Distinctive patterns in the presence of endophytic fungal species were observed in C. spinosa plants collected from the three provinces (Fig. S1), highlighting the unique regional diversity of these fungi. As the climate gradient shifted toward higher temperatures and more arid regions—from Alborz to Tehran and then Qom—fungal diversity and richness increased. Similarly, previous studies have investigated the impact of geographical origin and increasing temperature levels on endophytic microbiomes13,14.

The results showed that a wide range of fungal species coexist with C. spinosa. All 711 isolates were morphologically and molecularly classified into 76 morphotypes, with most belonging to the phylum Ascomycota. This aligns with the findings of Yeh and Kirschner15, who identified three fungal phyla—Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Zygomycota—in their study, with Ascomycota being the dominant phylum among their isolates.

Different patterns in the presence of endophytic fungal species in C. spinosa were observed across the three provinces of Qom, Tehran, and Alborz, indicating a unique diversity and symbiotic association in plants from arid and desert regions. The diversity of host-specific endophytic microbiomes in desert plants has been previously reported16. In a previous study conducted in Iran, researchers collected four C. spinosa plant samples from ten regions—predominantly mountainous, cold, and dry environments—and successfully isolated 72 fungal strains belonging to ten genera17. While our study focused on warmer, semi-arid to arid environments, the unique distribution of endophytic fungal species in these climates may indicate a specific functional role of symbiotic fungi. Fungal endophytes are widespread symbionts in plants and can directly influence plant drought resistance. These effects include drought avoidance strategies, such as enhanced water uptake or reduced transpiration rates, as well as drought tolerance mechanisms through osmotic regulation18,19.

The fungal frequency and diversity indices in the fruit, leaves, stem, and roots of C. spinosa showed that the abundance of endophytic fungi was significantly higher in the roots and in general, the diversity of endophytic microorganisms decreases after moving upwards or from the root to the fruits20. This can be attributed to the roots’ direct contact with the soil, which acts as a microbial reservoir, and the soil’s ability to buffer temperature and humidity fluctuations, thereby creating a stable environment for microbial colonization21. Plant roots play a crucial role in initiating plant-microbe interactions within the soil. Through root exudates, they facilitate the formation and stability of specialized microbial communities, tailored to support the host’s needs. This highlights how the influence of root exudates extends the gene expression profiles of associated endophytes, shaping their functional dynamics22. The higher number of fungal species in the roots can also be explained by the growth capability of the host plant in arid and semi-arid regions. In such environments, existing plants often possess sophisticated underground networks that create nutrient-rich zones. These extensive root systems, combined with the presence of various hosts and substrates, provide ample opportunities for fungi to survive. Consequently, desert environments with well-developed root structures may exhibit higher colony-forming units (CFU) and greater fungal species diversity in the roots compared to other plant parts21,23.

Given the significance of C. spinosa in arid and semi-arid landscapes, this study aimed to provide a comprehensive assessment of its fungal diversity using a culture-dependent approach. Among these, various fungal genera were identified as endophytes in this study. Some of them, observed to be present without causing harm to the host in this research, may exhibit pathogenic behavior in other hosts. Phytophthora24, for instance, is widely regarded as a plant pathogen, yet its presence as an endophyte in C. spinosa may be linked to host-dependent interactions and balanced antagonism. This implies that endophytes that engage in mutualistic interactions with their hosts under specific conditions may become pathogenic when the host is stressed, causing the balance of antagonism to shift in favor of the fungus25.

This research facilitates the identification of novel fungi and their metabolites, while also aiding in research on biotic and abiotic stress resilience.

Conclusions

In total, 711 isolates of endophytic fungi were obtained from four different tissues sampled in three provinces. These isolates were classified in three phyla, seven classes, fourteen orders, 28 families, and 36 genera. Caper plant tissues in each province showed different fungal community composition, dominant genera, indigenous genera, and different levels of biodiversity. These patterns reflect the distribution of endophytes within different geographic regions and organ specialization or tissue preference (a factor contributing to diversity in the fungal community), which may vary depending on environmental conditions (e.g., seasonal changes or plant developmental stages). Investigating the diversity of endophytic fungi will not only contribute to the understanding of intricate plant-fungal interactions but also hold potential for stimulating plant growth, producing bioactive compounds, and protecting against biotic and abiotic stresses. Further studies using culture-independent metagenomics approaches may elucidate the entire range of these interactions and ultimately demonstrate the possibilities for endophytic fungi to expand their applications in agriculture and pharmaceuticals.

Materials and methods

Sampling and fungal isolation

Ten mature C. spinosa plants in the active growth stage were randomly sampled from Alborz, Tehran, and Qom provinces during summer and autumn 2022. Climate information for each region is provided in Table S1. The samples were legally collected from unprotected areas, and all procedures were conducted in strict accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The plant specimens were identified by Prof. Mostafa Assadi at the Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands in Tehran, Iran. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Central Herbarium of Iran (Alborz: TARI111953, Tehran: TARI111951, Qom: TARI111952), located at the National Botanical Garden of Iran. Samples, transported to the Plant Pathology Laboratory at Tarbiat Modares University within 48 h, were rinsed with water to remove dust and epiphytic fungi. After ensuring that the selected tissues were healthy and viable, plant surfaces (ripe fruits, leaves, stems, roots) were sterilized with ethanol before segmenting: leaves, fruits, and main roots into 5 mm² pieces; stems and finer roots into 3 × 5 mm pieces. Following a modified Kusari et al. 26 protocol, disinfection involved two rounds of ethanol treatment (70%), lasting 30 s to 2 min based on tissue type. Segments were rinsed thrice with sterilized distilled water, dried on filter paper, and cultured on PDA containing 250 mg/L Ampicillin. Sterility was verified by streaking the final rinse water onto PDA medium. Samples were incubated at 25 ± 2 °C for 3–20 days for fungal growth. Afterward, isolates were purified using the hyphal tip27 or single spore28 culture method.

Morphological identification of endophytic fungi

Fungal morphology was assessed both macroscopically and microscopically. Macroscopic observations included colony surface and reverse colors, tissue type, and growth patterns. Microscopically, fruiting bodies, conidiophores, spores, and their arrangements were examined using lactophenol-based staining under an Olympus BH2 microscope29,30. Photomicrographs were captured with an Olympus DP72 camera on a BX51 microscope with differential interference contrast. A series of genera were identified using identification keys and authoritative articles, focusing on microscopic assessment31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

Molecular identification of endophytic fungi

After examining the microscopic slides of the isolates and identifying several genera based on reputable articles and identification keys, molecular identification was performed on the endophytic isolates that were mycelial or required final confirmation. In fact, morphological analysis was also supplemented with molecular techniques for isolates lacking conclusive identification. The ITS region was used for most mycelial isolates and some spore-producing ones that could be differentiated, while gene regions like gpdh, β-tub, CaM, and EF-1α were selected for samples requiring genus-specific differentiation. DNA extraction from mycelia cultured on PDA at 25 ± 2 °C for 7–10 days, as described by Safaie et al.47. PCR amplifications employed primers specific to target genes: ITS1/ITS4 for ITS48, gpdh1-F/gpdh2-R for gapdh49, EF1/ EF2 for EF-1α 50, Btub2Fd and Btub4Rd51 for β-tubulin and Cmd5/ Cmd6 for the CaM52 genes.

The 25 µl PCR mixture included 9 µl sterile deionized water, 12 µl 2X PCR Master mix (Pishgam Co.), 1 pmol primers, and 2 µl of 30 ng/µl DNA. PCR was performed using a Thermal cycler (Epgradiant, Eppendorf) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s; annealing at 58 °C (ITS), 52 °C (gapdh), 54 °C (EF-1α), 52 °C (β-tub), or 55 °C (CaM); extension at 72 °C for 60 s; and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were sequenced by Microsynth Company (www.microsynth.com).

After obtaining and editing the sequences, they were compared with existing sequences in the GenBank database using the BLAST search tool53 to ensure data accuracy. After confirming the quality and read length of the fragment, the sequences were submitted to the GenBank database (NCBI), and accession numbers were obtained for them (Supplementary Table S2).

Diversity analysis of endophytic fungi

Diversity measures the variety of life forms within a site or ecosystem, combining species richness and evenness, which increase biodiversity54,55. The variety of endophytes within different C. spinosa plant tissues and regions was examined. The combination and redundancy of these endophytic fungi should be assessed by counting the quantity of fungal isolates (\(\:N\)) and using species as the statistical element. Macroscopic study allows for the differentiation of the morphotypes21. In this context, abundance (\(\:N\)) refers to the number of isolates, while richness (\(\:S\)) denotes the numerical values of species present within a particular sample population.

To evaluate the suitability of each tissue type of C. spinosa from various regions as a colonization substrate for the fungi, we enumerated the samples colonized by specific fungi. The colonization frequency (CF) was then calculated using Eq. (1) described by Hata and Futai56.

Isolation frequency (IF) measures the incidence of specific fungal species within a set of isolates. It’s calculated by dividing the number of isolates for a particular species by the total number of isolates in all species, giving a percentage known as relative abundance (RA%). The formula is described by Huang et al.57 and given in Eq. (2).

The Chao1 estimator is a non-parametric method used to estimate species richness in a community. This method is based on the principle that rare species provide the most information about the number of undetected species. The Chao1 estimator emphasizes low-abundance species, utilizing only singletons and doubletons (species expressed by one and two individuals, respectively) to approximate the number of missing species. As a result, datasets with a bias toward species with low abundances derive the greatest advantage from this index. The Chao1 richness predictor is calculated using Eq. (3), which was described by Chao58. Where \(\:{S}_{obs}\)shows the observed number of species, \(\:{F}_{1}\)and \(\:{F}_{2}\) denote the number of singletons and doubletons, respectively.

Species richness of different fungal isolates was calculated using the Menhinick index (Dmn) utilizing the following formula (Eq. (4)) introduced by Whittaker59. In this formula, \(\:S\) represents the count of distinct fungal species per sample, and \(\:N\) shows the total number of fungal isolates within that specific sample.

The Camargo evenness index is a measure used to determine the evenness of species distribution within a community60. It is calculated using Eq. (5). Where \(\:{D}_{mn}\) is species richness.

The Shannon diversity index61 is a fundamental metric used to assess the diversity within fungal endophyte communities in different tissues. It is expressed through Eq. (6).

Where \(\:{p}_{i\:\:}\)represents the relative abundance (RA) of each species within a sample. The index value \(\:{H}^{{\prime\:}}\) can vary significantly. It considers both the number of species (richness) and the evenness of species abundances. It reaches 0 when only one species is present (indicating no diversity) and increases with higher diversity and a more even species distribution57. Thus, higher \(\:{H}^{{\prime\:}}\)values signal greater uncertainty in predicting the species of an individual organism, reflecting a more evenly distributed community.

Pielou’s evenness index, which is a common measure applied to assess how evenly individuals are distributed among species in a community62, was calculated using Eq. (7).

In this formula, represents Pielou’s measure of species evenness, stands for the Shannon-Wiener index in the sample, and indicates the total number of species within the sample.

Equation (8), which was introduced by Muthukrishnan et al. 63, was utilized to compute the evenness index (E).

Beta diversity is a concept introduced by Whittaker64, and measures the difference in species composition between ecosystems within a specific region. Two of the most common non-parametric indices to calculate beta diversity are the Sorensen index (βSor)65 and the Jaccard index (βJac)66.

The Sorensen similarity index quantifies the ratio of the double count of common species between two communities to the overall species count within each community. This index was determined utilizing Eq. (9) 65. Here, c represents the number of common fungal species found in both samples, while a and b indicate the species that are unique to each sample.

The Jaccard similarity index measures the proportion of species common between two communities relative to the total species count in both communities. This index is expressed using Eq. (10)66.

Where c is the number of species common to both samples, a and b represent the number of species unique to each sample.

Both indices compare the presence and absence of species between two communities, emphasizing the shared species. However, they differ slightly in their calculations. The Sorensen index gives more weight to shared species, making it more sensitive to common species, while the Jaccard index treats all species equally.

Fisher’s alpha is a parametric index used to estimate species diversity if the abundances of species follow a logarithmic distribution. This index was calculated using Eq. (11)67.

Where defines the number of species in the sample, shows the total number of endophytic fungal isolates, and is Fisher’s alpha, which represents the diversity index.

The Berger-Parker dominance index measures the relative abundance of the most dominant species in a community, highlighting its numerical importance.The formula for the Berger-Parker index is represented in Eq. (12)68.

Where \(\:{n}_{max}\)represents the count of individuals in the most plentiful species, while N denotes the total count of individuals in the sample.

The reciprocal of the Berger-Parker index (\(\:1/d\)) is commonly used, and an increase in this value indicates greater diversity and reduced dominance by the most abundant species.

The Simpson dominance index was employed to evaluate species diversity, indicating the likelihood that two randomly chosen isolates from a sample will be of the same species (Eq. (13))69.

Where \(\:{n}_{i}\)is the number of isolates of species, \(\:i\) and \(\:N\) are the total number of isolates across all species. Simpson’s Dominance Index (D) ranges from 0 to 1. A value close to 0 indicates high species diversity and community stability, with no single species dominating. Conversely, a value near 1 suggests low diversity, dominance by one or a few species, and potential ecosystem instability due to ecological pressures70.

Additionally, both the complement of the Simpson diversity index (1–D) and the reciprocal of the Simpson index (1–D) were computed. The Simpson diversity index (1-D) measures species diversity in a community. Higher values (close to 1) suggest high diversity, while lower values (close to 0) indicate low diversity71,72.

Species richness was assessed with the Margalef index (Eq. (14))73.

Where signifies the number of species and denotes the total count of isolates.

Eventually, data analysis and visualization were conducted using Minitab 18.1, Excel 2013, GraphPad Prism 10, and SR Plot (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en. Accessed on Jan, 2025).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A. & Dufresne, A. The importance of the Microbiome of the plant holobiont. New. Phytol.. 206, 1196–1206 (2015).

Rojas López-Menchero, J., Andrés, M. F. & Gonzalez-Coloma, A. & González García, V. Endophytic Fungi: Taxonomy, Isolation, and Current Applications. IntechOpen (2024).

Gowtham, H. G. et al. Fungal endophytes as mitigators against biotic and abiotic stresses in crop plants. J. Fungi. 10, 116 (2024).

Bhunjun, C. S. et al. Do all fungi have ancestors with endophytic lifestyles? Fungal Divers. 125, 73–98 (2024).

Inocencio, C., Rivera, D., Obón, M. C., Alcaraz, F. & Barreña J.-A. A systematic revision of capparis section capparis (Capparaceae) 1, 2. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 93, 122–149 (2006).

Chedraoui, S. et al. Capparis spinosa L. in a systematic review: A xerophilous species of multi values and promising potentialities for agrosystems under the threat of global warming. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1845 (2017).

Kuźniar, A., Kruczyńska, A., Włodarczyk, K., Vangronsveld, J. & Wolińska, A. Endophytes as permanent or Temporal inhabitants of different ecological niches in sustainable agriculture. Appl. Sci. 15, 1253 (2025).

Nurrahma, A. H. I., Harsonowati, W., Putri, H. H. & Iqbal, R. Current research trends in endophytic fungi modulating plant adaptation to climate Change-associated soil salinity stress. J Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr 1–21 (2024).

Sarkar, S. et al. Fungal endophyte: an interactive endosymbiont with the capability of modulating host physiology in myriad ways. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 701800 (2021).

Bi, B. et al. Diversity and functional roles of root-associated endophytic fungi in two dominant pioneer trees reclaimed from a metal mine slag heap in southwest China. Microorganisms 12, (2024). (2067).

Hashem, A. H. et al. Bioactive compounds and biomedical applications of endophytic fungi: a recent review. Microb. Cell. Fact. 22, 107 (2023).

Gupta, A. et al. Fungal endophytes: microfactories of novel bioactive compounds with therapeutic interventions; A comprehensive review on the biotechnological developments in the field of fungal endophytic biology over the last decade. Biomolecules 13, 1038 (2023).

Goncalves, H. V. et al. Endophytic fungus diversity in soybean plants submitted to conditions of elevated atmospheric CO2 and temperature. Can. J. Microbiol. 67, 290–300 (2021).

Maitra, P., Hrynkiewicz, K., Szuba, A., Niestrawska, A. & Mucha, J. The effects of Pinus sylvestris L. geographical origin on the community and co-occurrence of fungal and bacterial endophytes in a common garden experiment. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e00807–e00824 (2024).

Yeh, Y. H. & Kirschner, R. Study of endophytic fungi of Ipomoea pes-caprae reveals the superiority of in situ plant conservation over ex situ conservation from a mycological view. Sci. Rep. 15, (2025). (2040).

Massimo, N. C. et al. Fungal endophytes in aboveground tissues of desert plants: infrequent in culture, but highly diverse and distinctive symbionts. Microb. Ecol. 70, 61–76 (2015).

Rajabi, M., Azimi Moghadam, M. R., Azizi, A. & Soltani, J. Isolation and molecular identification of two rutin-producing endophytic fungi from caper (Capparis spinosa L). J. Microb. Biol. 11, 169–180 (2022).

Giauque, H. & Hawkes, C. V. Climate affects symbiotic fungal endophyte diversity and performance. Am. J. Bot. 100, 1435–1444 (2013).

Nombamba, A., Fadiji, A. E. & Babalola, O. O. Exploring the role of endophytic fungi in the amelioration of drought stress in plants. Plant Prot. Sci. 60, (2024).

Pathak, P. et al. Plant-endophyte interaction during biotic stress management. Plants 11, 2203 (2022).

Safaie, N. et al. Culture-based diversity of endophytic fungi of three species of ferula grown in Iran. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1363158 (2024).

Zhao, C., Onyino, J. & Gao, X. Current advances in the functional diversity and mechanisms underlying endophyte–plant interactions. Microorganisms 12, 779 (2024).

Zuo, Y. et al. Plant cover of ammopiptanthus mongolicus and soil factors shape soil microbial community and catabolic functional diversity in the arid desert in Northwest China. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 147, 103389 (2020).

Hardham, A. R. The cell biology behind phytophthora pathogenicity. Australas Plant. Pathol. 30, 91–98 (2001).

Schulz, B. & Boyle, C. The endophytic continuum. Mycol Res. 109, 661–686 (2005).

Kusari, S., Lamshöft, M. & Spiteller, M. Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius, an endophytic fungus from Juniperus communis L. Horstmann as a novel source of the anticancer pro-drug deoxypodophyllotoxin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107, 1019–1030 (2009).

Nelson, P. E., Toussoun, T. A. & Marasas, W. F. O. Fusarium species. An Illustrated Manual for Identification. Pennsylvania State University Press (1983).

Booth, C. Methods in microbiology. Vol. 4. Academic Press (1971).

Vyzantiadis, T. A. A., Johnson, E. M. & Kibbler, C. C. From the patient to the clinical mycology laboratory: how can we optimise microscopy and culture methods for mould identification? J. Clin. Pathol. 65, 475–483 (2012).

Petersen, J. & McLaughlin, S. Laboratory exercises in microbiology: discovering the unseen world through hands-on investigation. Queensborough Commun. Coll. (2016).

Boerema, G. H. Phoma identification manual: differentiation of specific and infra-specific taxa in culture. CABI Publishing (2004).

Leslie, J. F. & Summerell, B. A. The Fusarium laboratory manual. Blackwell Publishing (2006).

Sandoval-Denis, M. et al. Redefining Microascus, scopulariopsis and allied genera. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 36, 1–36 (2016).

Burgess, T. I. et al. New species from phytophthora clade 6a: evidence for recent radiation. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 41, 1–17 (2018).

Sandberg, D. C., del Olmo-Ruiz, M., Sykes, B. E., Woods, D. O. & Arnold, A. E. Three distinctive preussia (Sporormiaceae) from photosynthetic stems of ephedra trifurca (Ephedraceae, Gnetophyta) in southeastern Arizona, USA. Plant. Fungal Syst. 67, 63–74 (2022).

Joseph, M. R. P. et al. Identification of Basidiobolus species from the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) and their association with isolates from human basidiobolomycosis. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 16, 178–183 (2022).

Lee, W. et al. Diversity of cladosporium (Cladosporiales, Cladosporiaceae) species in marine environments and report on five new species. MycoKeys 98, 87 (2023).

Yin, C., Zhang, Z., Wang, S., Ma, L. & Zhang, X. Three new species of Pestalotiopsis (Amphisphaeriales, Sporocadaceae) were identified by morphology and multigene phylogeny from Hainan and Yunnan, China. MycoKeys 107, 51 (2024).

Crous, P. W. et al. Phylogenetic lineages in the capnodiales. Stud. Mycol. 64, 17–47 (2009).

Houbraken, J., Verweij, P. E., Rijs, A. J. M. M., Borman, A. M. & Samson, R. A. Identification of paecilomyces variotii in clinical samples and settings. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 2754–2761 (2010).

Aveskamp, M. M., de Gruyter, J., Woudenberg, J. H. C., Verkley, G. J. M. & Crous, P. W. Highlights of the didymellaceae: a polyphasic approach to characterise phoma and related pleosporalean genera. Stud. Mycol. 65, 1–60 (2010).

Perdomo, H. et al. Spectrum of clinically relevant acremonium species in the united States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 243–256 (2011).

Woudenberg, J. H. C., Groenewald, J. Z., Binder, M. & Crous, P. W. Alternaria redefined. Stud. Mycol. 75, 171–212 (2013).

Samson, R. A. et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 78, 141–173 (2014).

Visagie, C. M. et al. Identification and nomenclature of the genus penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 78, 343–371 (2014).

Nyongesa, B. W., Okoth, S. & Ayugi, V. Identification key for Aspergillus species isolated from maize and soil of Nandi County, Kenya. Adv. Microbiol. 5, 205 (2015).

Safaie, N., Alizadeh, A. A., Saeidi, A., Adam, G. & Rahimian, H. Molecular characterization and genetic diversity among Iranian populations of fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of wheat headblight. Iran. J. Plant. Pathol. 41, 171–189 (2005).

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guid Methods Appl. 18, 315–322 (1990).

Berbee, M. L., Pirseyedi, M. & Hubbard, S. Cochliobolus phylogenetics and the origin of known, highly virulent pathogens, inferred from ITS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene sequences. Mycologia 91, 964–977 (1999).

O’Donnell, K., Kistler, H. C., Tacke, B. K. & Casper, H. H. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 7905–7910 (2000).

Glass, N. L. & Donaldson, G. C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1323–1330 (1995).

Hong, S. B., Cho, H. S., Shin, H. D., Frisvad, J. C. & Samson, R. A. Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 477–486 (2006).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Soininen, J., Passy, S. & Hillebrand, H. The relationship between species richness and evenness: a meta-analysis of studies across aquatic ecosystems. Oecologia 169, 803–809 (2012).

Blowes, S. A. et al. Local biodiversity change reflects interactions among changing abundance, evenness, and richness. Ecology 103, e3820 (2022).

Hata, K. & Futai, K. Endophytic fungi associated with healthy pine needles and needles infested by the pine needle gall midge, thecodiplosis japonensis. Can. J. Bot. 73, 384–390 (1995).

Huang, W. Y., Cai, Y. Z., Hyde, K. D., Corke, H. & Sun, M. Biodiversity of endophytic fungi associated with 29 traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Fungal Divers. 33, 61–75 (2008).

Chao, A. Nonparametric Estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand J. Stat 265–270 (1984).

RH, W. Evolution of species diversity in land communities. Evol. Biol. 10, 1–67 (1977).

Camargo, J. A. Temporal and Spatial variations in dominance, diversity and biotic indices along a limestone stream receiving a trout farm effluent. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 63, 343–359 (1992).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Pielou, E. C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 13, 131–144 (1966).

Muthukrishnan, S., Sanjayan, K. P. & Jahir, H. K. Species composition, seasonal changes and community ordination of alkalotolerant micro fungal diversity in a natural scrub jungle ecosystem of Tamil Nadu, India. Mycosphere 3, 92–109 (2012).

Whittaker, R. H. Vegetation of the Siskiyou mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol. Monogr. 30, 279–338 (1960).

Sorensen, T. A method of Establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biol. Skr. 5, 1–34 (1948).

Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. 1. New. Phytol.. 11, 37–50 (1912).

Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S. & Williams, C. B. The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. J. Anim. Ecol. 42–58 (1943).

Berger, W. H. & Parker, F. L. Diversity of planktonic foraminifera in deep-sea sediments. Sci. (80-). 168, 1345–1347 (1970).

Simpson, E. H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163, 688 (1949).

Oktavianti, R. & Purwanti, F. Kelimpahan echinodermata Pada Ekosistem Padang Lamun Di Pulau Panggang, Kepulauan Seribu, Jakarta. Manag Aquat. Resour. J. 3, 243–249 (2014).

Kim, B. R. et al. Deciphering diversity indices for a better Understanding of microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 2089–2093 (2017).

Tiffeau-Mayer, A. Unbiased Estimation of sampling variance for simpson’s diversity index. Phys. Rev. E. 109, 64411 (2024).

Margalef, R. Temporal Succession and Spatial Heterogeneity in Phytoplankton In AA Buzzati-Traverso (ed), Perspective in Marine Biology. 323–349 (1958).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of Tarbiat Modares University and also Modares Science and Technology Park for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S. designed and supervised the project and validated the data. S.K. performed sampling, isolation, and identification of fungi. Sh.M. guided data processing. L.E. advised on fungal identification. N.S. and S.K. carried out diversity analyses. S.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. N.S. approved the final version. All authors contributed to the preparation and review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Permission

Capparis spinosa L. samples were collected legally from non-protected natural areas with permission from the relevant authorities.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimzadeh, S., Safaie, N., Mojerlou, S. et al. Identity and diversity of culturable endophytic fungi associated with Capparis spinosa L. in Iran. Sci Rep 15, 41502 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25257-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25257-0