Abstract

With the rapid advancement of emerging technologies, design education is undergoing a model transformation. This study employs a mixed-methods approach that combines semantic textual analysis with semi-structured interviews, which aims to examine the development strategies of 71 design education institutions worldwide to systematically analyze the pathways through which technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR), Big Data, and Robotics are integrated into design education. Four major models of intervention are identified: lab-driven innovation, industry incubation, interdisciplinary fusion, and curriculum integration. The research reveals that emerging technologies primarily intervene in areas such as instructional support, pedagogy, and curriculum structure, while remaining underrepresented in strategic dimensions such as regional distribution of DEIs, degree types, and stakeholder types. It also highlights key challenges including resource disparity, lack of accreditation frameworks, overreliance on technology, and ethical risks. In response, it proposes strategic solutions such as regional resource sharing, modular accreditation systems, human-AI collaborative teaching, industry-driven curriculum optimization, and ethical governance of technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of technology, emerging innovations such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), digital fabrication, and data-driven design decision-making are profoundly reshaping the design industry1,2,3,4,5. These technologies not only transform how design practices are conducted but also place new demands on design education. Consequently, design schools must thoroughly consider the influence of these emerging technologies to ensure their curricula and research agendas align with evolving industry trends6.

Some researchers indicate that an increasing number of design education institutions (DEIs) are enhancing students’ creative capacities through technology-driven pedagogical approaches (In this paper, “DEIs” is used as an abbreviation for “design education institutions,” referring to higher education institutions that impart design theory and practical knowledge. This includes universities, colleges, and their subordinate entities such as schools). For instance, some DEIs have begun implementing AI-based design tools to support more efficient and expansive creative exploration7. Additionally, VR and AR technologies are being utilized to simulate immersive design environments, enabling students to grasp complex design concepts in a more intuitive manner8. DEIs that successfully integrate emerging technologies tend to be more adaptable, better positioned to respond to industry shifts, and more capable of equipping students with competitive skills.

Responding to the situation mentioned above, DEIs should adopt flexible strategies and models to accommodate future uncertainties in order to take the initiative. For instance, some studies suggest that DEIs should employ data-informed decision-making strategies to dynamically adjust their future direction and maximize the educational benefits of technological integration9,10.

Through a qualitative empirical research and case analyses, this study categorizes emerging technological elements in design education and seeks to answer the following research questions:

What intervention models of emerging technologies have been integrated into design education?

What are the perspectives of different stakeholders on these models?

Through semi-structured interviews, this study abstracts four emerging-technology intervened models and offers recommendations for the future direction of DEIs under a technology-driven context.

Literature review

The historical integration and evolutionary trends of emerging technologies in the development of DEIs

As incubators of innovation and creativity, DEIs have been influenced by emerging technologies in the context of continuous technological advancement. From traditional craftsmanship to digital design, and further to the integration of AI and XR, emerging technologies have increasingly become essential to both design education and research. This study explores how these technologies have contributed to the development of DEIs under integrated models.

Iterative trends of emerging technologies in DEIs

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the rise of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and computer graphics marked the initial integration of digital technologies into the curricula of DEIs. The widespread adoption of CAD software significantly improved precision in architectural and industrial design, while also transforming traditional hand-drawing teaching methods11.

In the 21st century, the proliferation of internet technologies fostered the growth of online education, leading to the rapid development of remote learning and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). DEIs began utilizing online platforms to expand access to design knowledge12. Additionally, internet-based collaborative tools such as AutoCAD 360 and SketchUp enabled cloud-based teamwork among students, enhancing design efficiency.

Since 2010, interaction design has emerged as a major direction within the design discipline, with AR and VR technologies being increasingly adopted in design education. Many DEIs have established VR laboratories that allow students to immerse themselves in spatial design and interface interaction7. Moreover, the rise of AI technologies—such as machine learning and computer vision—has led to the development of intelligent design tools (e.g., Adobe Sensei), which assist the creative process and enhance innovation efficiency13. During this stage, DEIs also began to experiment with digital education models, incorporating online and blended learning methods. For instance, Menon and Suresh14 investigated how strategic IT flexibility influences the sustainable development of private schools, arguing that early technological adaptability plays a critical role in institutional competitiveness.

In recent years, AI and big data analytics have emerged as core driving forces in the development of DEIs. AI-generated design technologies, such as image generation through Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), are reshaping the design process, enabling personalized and automated creation. Big data analytics, on the other hand, enhances the precision of design decisions by helping designers better understand user needs15. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, remote education became mainstream, leading to rapid growth in smart learning platforms and AI-based teaching assistants16.

As of 2024, DEIs are entering the era of “Intelligent Plus”, characterized by the convergence of AI, XR, blockchain, and other technologies. Schwoerer17 argues that future institutional strategies must be developed in tandem with emerging technologies to ensure sustainable growth.

Pathways of emerging technology integration in design education

DEIs have been cultivating new educational ecosystems by deepening collaborations among industry, university and research (IUR). On one hand, leading technology companies and universities have co-established joint laboratories, introducing industrial-grade tools such as AutoML-based automated design systems and AR content production platforms into educational settings. On the other hand, the adoption of a “dual-mentor” model enables students to engage in real-world project-based training, participating in the full product development cycle—from user research to prototype testing18. This collaborative model yields triple benefits: enterprises receive innovative solutions, DEIs update their practical teaching resources, and students gain hands-on experience with industry-grade projects. Notably, successful collaboration requires institutional safeguards such as intellectual property allocation mechanisms and incentives for outcome commercialization, to avoid tokenistic engagement.

Technology-driven disciplinary convergence is reshaping the epistemological landscape of design education. In the emerging field of ‘computational design,’ which lies at the intersection of AI and interaction design, disciplines such as computer graphics, cognitive psychology, and design methodology are being integrated. Typical applications include generative advertising and performance-driven architectural modeling13. This convergence is characterized by three key features: (1) Hybrid knowledge structures, exemplified by Tongji University’s dual-degree program groups’(https://tjdi.tongji.edu.cn/about.do?ID=68&lang=_en); (2) Empirical research methods, such as the MIT Media Lab’s use of eye-tracking and EEG data to optimize interaction design (https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/confusion/overview/); (3) Diversified innovation actors, like Huawei’s UCD Center (https://www.huawei.com/en/media-center/multimedia/photos/facilities/shanghai-research-center), where interdisciplinary teams consist of designers, engineers, and sociologists.

Such transformations demand the restructuring of training programs. For example, the Academy of Arts and Design at Tsinghua University has launched a cross-disciplinary master’s program in Arts and Technology, with integration of AI, innovative engineering technology, and the digital economy (https://www.ad.tsinghua.edu.cn/info/1487/31333.htm). These cross-disciplinary initiatives not only give rise to new research domains (e.g., affective computing in design) but also facilitate a model shift in design education from experience-driven to science-oriented models.

The rapid evolution of emerging technologies prompts systematic adjustments to traditional curricula. Technological innovations—such as AI, big data, and XR—are fundamentally transforming the tools, methodologies, and cognitive frameworks of the design industry. To address this shift, leading DEIs around the world have introduced forward-looking courses. For instance, ‘Computational Design’ emphasizes algorithmic generation and parametric modeling; ‘Intelligent Design’ focuses on machine learning for design optimization; and ‘VR Interaction Design’ trains students in crafting immersive user experiences2. These curricular innovations not only update content but also reconfigure the knowledge structure for cultivating designers.

Impacts of emerging technologies on design education

In recent years, the development of emerging technologies such as AI, VR, AR, three-dimensional (3D) printing, and Big Data has brought profound transformations to design education. Traditional design education was primarily based on theoretical instruction and manual practice. However, the integration of these new technologies has reshaped teaching methodologies, influencing students’ creativity, learning processes, and job readiness19. This section analyzes recent studies on the application of emerging technologies in design education, highlights their impacts, and identifies existing research gaps.

VR and AR

VR and AR technologies are significantly transforming design practice and are widely applied in architectural, product, and fashion design education. These technologies offer immersive design experimentation environments, reducing material costs and enhancing students’ spatial awareness and design thinking20. AR, in particular, enriches interactive learning by overlaying digital information onto physical environments, allowing students to test and revise designs in real time, thus optimizing the overall design process21,22.

Stasolla et al.23 suggest that combining deep learning and reinforcement learning with game-based technologies can further improve user engagement and interaction quality in design education. More broadly, VR and AR not only extend students’ capabilities in modeling, prototyping, and spatial design but also provide technological pathways to alleviate fatigue from human-computer interaction24. Papadaki and Watson25 argue that the integration of VR/AR with personalized learning methods can enhance both teaching quality and curriculum structure. Additionally, these technologies are reshaping DEIs’ strategic management by supporting smart campus construction and data-driven decision systems.

AI and computational design

AI applications in design education mainly include intelligent design assistance, personalized learning path recommendations, and automated evaluation26. Shahidi Hamedani and Aslam27 emphasize that AI not only transforms business operations but also significantly impacts education, especially the curriculum and pedagogy of design disciplines. Through machine learning and GANs, students can use AI tools to aid creative tasks and enhance efficiency. For example, Nguyen and colleagues have explored the role of generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) in design education, finding that it fosters conceptual exploration and streamlines design workflows28,29. Peikos and Stavrou30 further highlight, through experimental studies, that generative AI enhances students’ creative thinking and design abilities. However, some scholars warn that overreliance on AI may suppress independent thinking and innovation31,32. Moreover, AI-based evaluation tools are improving the intelligence of educational governance33. The integration of AI into curricula promotes innovation in course design, such as teaching computational design capabilities34. Weng et al.35 examine how case-based teaching improves creativity and entrepreneurial skills in design students. Overall, AI is redefining both the core concepts and practices of design education.

3D printing and digital fabrication

3D printing has seen widespread adoption in design education, allowing students to iterate rapidly and produce physical prototypes. Grizioti et al.36 find that the use of 3D printing significantly enhances students’ experimental competence and engineering thinking in product design courses. Nevertheless, many institutions still lack the necessary hardware and qualified instructors, which limits the widespread implementation of 3D printing instruction23.

Big data and personalized learning

The introduction of big data analytics has enabled DEIs to formulate curricula and teaching strategies with greater precision. Mensah and Adukpo37 point out that big data-driven financial technologies (FinTech) not only influence business models but also have a profound impact on the management models of DEIs. In terms of curriculum optimization, Cui et al.38 emphasize that big data analytics can help DEIs assess teaching quality and enhance the overall student learning experience.

Specifically, Cantabella et al.39 found that integrating Learning Management Systems (LMS) with big data analytics allows for real-time tracking of students’ learning paths, task completion status, and interaction frequency.

However, despite the broad potential of big data technologies in the education sector, Giannakos, Horn, and Cukurova40 note that their application in design education remains in its early stages. Due to the highly creative and unstructured nature of design education—often involving open-ended exploration, critical thinking, and diverse forms of expression—standardized data collection and quantitative analysis present considerable challenges.

Remote and blended learning

Enamorado-Díaz et al.22 highlight that remote collaborative design platforms—such as Miro, Figma, Zoom, and Google Jamboard—overcome physical boundaries and allow students to participate in global design projects. These technologies enhance cross-cultural communication, project management skills, and international collaboration experience, boosting global competitiveness.

The integration of AI-assisted tools further supports efficient modeling and iteration of complex design tasks in virtual settings. However, digital transformation also introduces new challenges. Rasheed et al.41 note that the absence of face-to-face interaction hampers hands-on practice, material perception, and immediate feedback—core components of design learning. Remote adaptation of practical courses remains difficult, often leading to misinterpretations of material properties, scale, and spatial relationships.

Moreover, while online collaboration offers convenience, it can reduce communication efficiency and create imbalances in task distribution, affecting project quality and equitable learning outcomes.

Summary

Despite the transformative potential of emerging technologies in design education, current research faces several limitations:

First, there is a lack of integration between theory and practice. Some research overemphasizes technical functionality while ignoring implementation barriers—e.g., studies on 3D printing focus on creative potential but overlook hardware costs and faculty training. Al-Kamzari and Alias42 point out that research on the integration of pedagogy and technology remains fragmented and urgently needs systematic synthesis.

Next, there is insufficient investigation into the depth and continuity of technology adoption. Many studies focus only on short-term effects, such as AI’s role in aiding creativity, while neglecting long-term impacts on independent thinking and innovation. How to sustainably integrate new technologies into curricula remains an open question.

Lastly, interaction and equity challenges in remote learning are pronounced. Few studies address how to enhance the remote collaborative experience. Some researchers43,44 highlight the dual challenges of economic constraints and infrastructural gaps faced by developing countries, exposing the geographic limitations of current research coverage.

Methodology

Strategic planning not only provides direction for the long-term development of DEIs, but also enables them to maintain competitiveness in an challenging environment with emerging technology advancing45. The strategic goals of DEIs typically encompass industry collaboration, student training, curriculum development, and research focus. Therefore, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining semantic textual analysis with semi-structured interviews, to explore the development strategies of DEIs worldwide and their models for integrating emerging technologies.

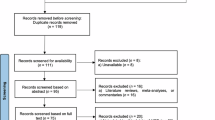

Data sources and selection criteria

The targeted DEIs for this study were drawn from QS World University Rankings databases (QS). Choosing QS was based on the fact that it provides a dedicated Art & Design subject ranking, a classification system that has been in place for over ten years and is increasingly recognized by practitioners and researchers in the field. The author acknowledges that this ranking system does not fully reflect the actual inclusion or true quality levels of institutions in the field (In the QS rankings framework, Art & Design and Linguistics are both sub‑fields under the broad Arts & Humanities category. They are evaluated using the same methodological framework, including indicators like academic reputation, employer reputation, and research impact. However, these two subjects differ substantially in their disciplinary nature, educational models, and evaluation approaches, which raises concerns about the reliability and fairness of comparing their ranking outcomes directly. For details on the ranking methodology, see: https://support.qs.com/hc/en-gb/articles/4539968720924-QS-Subject-Categorisation?utm_source=chatgpt.com); however, amid more than ten thousand universities worldwide (There are currently approximately 21,000 higher education institutions. This data comes from: https://www.whed.net/home.php), it would be extremely difficult to identify suitable study subjects in a short time. Therefore, based on expert interviews (see Appendix 1), the author selected from the 262 art & design institutions ranked by QS. In the future, the authors plans to continue tracking qualified institutions from a broader range to contribute toward greater diversity and equity in design education research.

Initially, a qualitative textual analysis was conducted on strategic development documents (For example, NEXT: School of the Art Institute of Chicago Strategic Plan. https://www.saic.edu/strategic-initiatives), official statements (For example, About the Lab-Imagine what we can become. https://www.media.mit.edu/about/overview/), et al. related to DEIs within QS databases to identify and extract representative educational strategies and the emerging technologies referenced within them.

In the data selection process, 71 representative DEIs were chosen, which located across 25 countries including the United States, Canada, Colombia, Peru, the United Kingdom, Finland, Italy, China, India, Australia, and New Zealand (Appendix 2). The selection criteria were:

-

a.

High academic reputation and international influence along with regional representativeness;

-

b.

Explicit mention of emerging technologies in connection with design education in official documents;

-

c.

Ongoing interdisciplinary innovation collaborations or participation in international cooperation networks at the strategic or policy level.

To ensure representativeness, the selection of research objects was refined through semi-structured interviews.

Semantic textual analysis

Within the selected 71 DEIs, the authors conducted a semantic textual analysis of their strategic development documents. The primary objectives of this analysis were as follows: first, to identify elements of emerging technologies within the strategic plans of DEIs; second, to categorize these technological elements and analyze specific cases in depth to explore their application models in design education; and finally, to synthesize the various strategic-level approaches adopted by different DEIs for integrating emerging technologies.

Semi-structured interviews

To complement the limitations of textual analysis and gain deeper insight into the paradigms of technology integration in design education, semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interviewees consisted of four groups of stakeholders, with a total of eight representative participants. Details of the interviewees are provided in Table 1.

Through these interviews, the study explores how various stakeholders perceive the strategic development of DEIs, with particular attention to the role and positioning of emerging technologies within educational systems.

Findings

Proportion statistics of DEIs by country

According to the statistics (Fig. 1), the 71 DEIs are distributed across 25 countries spanning five continents. Among them, the United States has the largest representation, with 19 DEIs included. Following the U.S., Australia, the United Kingdom, and China each have five or more DEIs represented. Countries with three DEIs selected are mainly located in Asia, while those with two DEIs primarily come from Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Additionally, several South American countries each have one DEI included. Overall, a higher number of North American DEIs emphasize the role of emerging technologies in the development of design education (20 out of 71), followed by European DEIs (17 out of 71), then Asian institutions (22 out of 71), and finally DEIs from Australia (8 out of 71) and South America (4 out of 71).

Classification of emerging technologies and their frequency of mention

Within the strategic plans of the 71 DEIs analyzed, the types of emerging technologies mentioned and their frequency of occurrence exhibit a clear hierarchical distribution (Fig. 2). This pattern reflects current priorities in the application of technology within design education, as well as future developmental trajectories. AR, VR, and AI are the most frequently referenced technologies, effectively forming the core focus of design education strategies.

Following closely behind are Big Data and Data Science. These technologies play significant roles in information design, smart city development, and health monitoring, positioning them as important components in the strategic planning of design education.

Robotics and digital fabrication, including 3D printing, occupy a mid-level range in terms of frequency. These technologies are primarily associated with intelligent manufacturing and product design.

In contrast, technologies such as game technology, human-computer interaction (HCI), internet of things (IoT), generative technologies, and digital twins appear less frequently.

In sum, the variety and frequency distribution of emerging technologies in the strategic plans of the 71 DEIs reflect a diverse set of demands and evolving priorities within design education. The high frequency of intelligent, interactive, and data-driven technologies underscores the sector’s current focus, while the inclusion of mid- and low-frequency technologies indicates expanding interest.

Models of emerging technology integration in design education

This study adopts an inductive approach to summarize four distinct models through which emerging technologies are integrated into design education, and analyzes each model through case studies (Appendix 2).

Model 1: lab-driven innovation

This model emphasizes the establishment of dedicated labs to deeply integrate cutting-edge technology research with education, often leveraging Project-Based Learning (PBL) and industry partnerships to enhance the practical application of technology.

For example, the MIT Media Lab focuses on fields including AI, interactive technologies, wearable devices, VR/AR, and machine learning. It aims to explore the future of HCI while highlighting the profound societal impacts of technology. Its “Life with AI” research theme includes projects such as the Moodeng AI Challenge, which aim to foster a deeper connection between humans and nature while exploring the applications of AI in healthcare and human behavior (https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/moodeng-ai/overview/).

The Virtual Production Institute at Texas A&M University (https://vpi.tamu.edu/) conducts research on extended reality (XR), VR/AR, AI, real-time 3D graphics, simulation, and digital twins. It provides immersive environments for film production, architecture, game development, and medical training, while integrating industry collaboration to ensure real-world applicability.

At the University of Chicago, the MADD Center (https://www.studentarts.uchicago.edu/maddcenter) concentrates on game design, data visualization, interactive media, and VR/AR. It leverages advanced facilities like the Hack Arts Lab, Weston Game Lab, and GIS Lab to explore the frontiers of AI-generated art and immersive interaction.

ImaginationLancaster (https://imagination.lancaster.ac.uk/) at Lancaster University, through its ‘Beyond Imagination’ initiative, investigates the application of AI, digital worlds, and data analytics in areas such as aging societies, health, and sustainability.

The d.school at Stanford University is renowned for its focus on design thinking. Using methodologies like ‘Synthesize Information’ and ‘Experiment Rapidly,’ it explores the potential of generative AI in design innovation. For example, a chatbot named “Riff” was developed to support students in reflecting on their learning process and to foster the development of creative thinking (https://dschool.stanford.edu/stories/reflecting-with-ai?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

The Data-Driven Art Lab at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) is dedicated to applying AI in creative generation and artistic design, promoting deep integration of computer vision and machine learning in the arts. RISD has also partnered with AI image generation company Invoke to provide students with advanced tools for exploring the potential of AI in artistic creation (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-school-partners-ai-company-risd-invoke-2602338).

University of Washington houses DXARTS and HCDE labs, which specialize in experimental media research, including AI-generated art, affective computing, and social innovation. For example, the HCDE Lab has developed tools such as “AI Puzzlers” to help children think critically about AI and understand its limitations (https://www.hcde.washington.edu/news/hcde-impact/ai-puzzlers).

Model 2: industry incubation

The model of industry collaboration and technology incubation aims to cultivate students’ competencies in technology application through deep partnerships with industry, while supporting the development of AI-driven innovative products via entrepreneurship incubators. This model emphasizes practice-driven learning, enabling students to explore emerging technologies within real-world industry contexts and apply them across diverse fields such as design, computer science, user experience, and digital arts46.

At the University of Southern California (USC), the Iovine and Young Academy adopts a Challenge-Based Reflective Learning (CBRL, https://iovine-young.usc.edu/the-learning-experience/challenge-based-reflective-learning), requiring students to directly engage in solving real industry problems in cutting-edge areas such as AI, Extended Reality (XR), and interactive technologies. This prepares students with both industry adaptability and innovative thinking.

At Manchester Metropolitan University, the School of Digital Arts (SODA) integrates AI technologies into areas like game design, animation, and user experience design, allowing students to gain hands-on industry experience and participate in real-world project partnerships. Modal gallery hosts exhibitions on game‑engine culture (e.g., using Unity and Unreal) and reveals how students and artists explore interactive, XR-informed storytelling and design prototypes in real public showcases (https://www.schoolofdigitalarts.mmu.ac.uk/modal-new-school-of-digital-arts-gallery-launches-with-game-engine-culture-exhibition/?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

TU Berlin offers a Design & Computation, M.A. program (https://www.tu.berlin/en/studying/study-programs/all-programs-offered/study-course/design-computation-m-a) that emphasizes AI-generated design. Through collaborations with technical companies, the program explores topics such as the algorithmization of everyday life and the digitalization of production and labor, advancing the application of AI in design and manufacturing.

Model 3: interdisciplinary fusion

The interdisciplinary model emphasizes the close collaboration between design, computer science, and the social sciences. It aims to cultivate designers who possess both technical proficiency and humanistic insight, enabling them to carry out innovative practices within complex sociotechnical environments. The core focus of this model is to explore how technology influences society, culture, and human experience, while advancing the deep integration of design with AI, HCI, and data science.

For instance, the Design Tech (https://designtech.cornell.edu/academics/designtech) track at Cornell University integrates disciplines such as design, HCI, digital media, computer science, and materials engineering. It explores AI-powered interaction design and data-intensive design methodologies, promoting technological innovation in design applications.

Aalto University combines art, technology, and philosophy to investigate the ‘Grey Area Between Human and Machine (https://aaltouniversity.shorthandstories.com/future-of-arts/), delving into the role of AI in art, gaming, and visual representation.

At the Royal College of Art (RCA), the course “Design Robotics and Gaming” merges design with AI, robotics, and gaming, training students to master frontier technologies and apply them creatively. For instance, the “Getting a Grip” project developed a soft robotic system for conducting inspections in hazardous environments; a wind turbine blade maintenance robotic arm enables remote automated repairs of wind turbine blades; the “Reminisys” initiative created an AI‑assisted wearable device designed to support individuals with dementia (https://www.rca.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/5-ways-rca-robotics-laboratory-making-world-more-safe-sustainable-and-inclusive/?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

From a social impact perspective, the Keller Center at Princeton University integrates design with social innovation, leveraging AI and data analytics to drive projects focused on public good and sustainable development.

Meanwhile, the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) prioritizes interdisciplinary development across architecture, AI, and data science. It explores AI applications in smart cities and intelligent manufacturing, promoting tech-driven urban transformation and industrial upgrading.

Model 4: curriculum integration

Some DEIs are directly embedding emerging technologies into their curricular frameworks to cultivate students with industry competitiveness. These technologies are not only explicitly mentioned in program descriptions or degree offerings, but are also embedded in course content to ensure students apply it in practice.

For example, at The University of Queensland, the Information Environments (https://programs-courses.uq.edu.au/plan.html?acad_plan=INENVC2454) program emphasizes instruction in coding, data, and HCI, equipping students to use big data and digital technologies to solve real-world problems.

City University of Hong Kong offers courses in new media art, HCI, computer graphics, and AI, covering topics such as machine learning, playable media, and interactive art, aiming to nurture versatile talents with both technical and creative capabilities (https://www.scm.cityu.edu.hk/).

Meanwhile, Chang Jung Christian University integrates art and game technology in its programs on interactive art, game design, and VR/AR/XR, preparing students for roles in interface and visual interaction design (https://dweb.cjcu.edu.tw/camd/article/2462).

At Sungkyunkwan University, emerging technologies are actively incorporated into programs in information design and game design. The former leverages big data analytics to support user demand forecasting and design optimization, while the latter focuses on game art and market insight in the AI era, aiming to train the next generation of “Super Game Designers (https://art.skku.edu/eng_art/game_intro.do).”

Distribution of the 71 DEIs across the four models

As shown in Fig. 3, Model 4 accounts for the highest proportion, followed by Model 3 and 1, with Model 2 being the least represented. This indicates that most DEIs tend to integrate emerging technologies directly into course instruction. Interdisciplinary collaboration and laboratory-driven technological exploration extend classroom teaching horizontally and vertically, respectively: students are encouraged to discuss the application of emerging technologies and tools with peers from different fields across various contexts, while deepening their technical knowledge and research skills by working alongside experts in laboratory settings. Finally, only about one-tenth of the DEIs emphasize Model 2 based on emerging technologies.

Based on the distribution of models across countries (Fig. 4), a clear pattern emerges: Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK, and the US exhibit a higher proportion of DEIs in Model 1; China and Spain have a greater share in Model 3; while Australia, Denmark, India, Italy, Singapore, South Korea, and Switzerland show elevated representation in Model 4. This reflects the differentiated attitudes among DEIs in different countries toward models of applying emerging technologies.

Discussion

The integration of emerging technologies into design education systems

A wide variety of design education models have been developed to date. These include the Bauhaus model, which emphasizes the integration of art and technology, the unification of theory and practice, and interdisciplinary learning47,48; Design Thinking Pedagogy, which centers on user-focused innovation49,50; Reflective Practice, which enhances design skills through iterative reflection on the design process51,52; and the Apprenticeship Model, which emphasizes learning through close collaboration with experienced designers53. Other approaches include Problem-Based Learning (PBL), where students actively explore real-world problems; Studio-Based Learning, which is project-driven54; and the cultivation of “T-shaped talents,” who possess deep disciplinary knowledge alongside broad interdisciplinary abilities55.

However, a systematic framework for design education that integrates these models from the perspective of emerging technologies has not yet been widely discussed. Such a system responds to the challenges posed by the rapid iteration of technology and offers strategies for adapting design education accordingly. This study attempts to inductively identify and reflect on this system, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Based on the analysis of the four models in section “Models of emerging technology integration in design education”, the origin where Model 4 is located represents physical or virtual environments such as classrooms, workshops, and seminars, where design instructors and students engage together. This serves as the starting point for students’ exposure to the professional field and the initial bridge for building teacher-student relationships. The vertical axis where Model 1 is situated focuses on cultivating students’ in-depth expertise and the acquisition of necessary knowledge and skills within a specific domain, through real-world projects and guided mentorship in laboratories. Model 3 emphasizes expanding interdisciplinary knowledge alongside specialization, enriching students’ learning and research inspiration within their primary field. Model 2, distinct from the dimensions of professional learning and research, focuses on developing students’ abilities in collaboration, communication, resource integration, and practical implementation, marking a critical step toward entering the real world. Overall, the design education system composed of these four models offers stakeholders a framework for evaluating the integration of emerging technologies into design education and provides a basis for the archiving and classification of related educational resources.

Reflections on the four models

Chen56, focusing on doctoral-level design education, proposed a structural framework comprising six key components: regional distribution of DEIs, degree types, stakeholder types, educational support, teaching schedule, and curriculum. This framework provides a classification for the vast and complex elements of design education and offers stakeholders a structured lens through which to examine related issues. It also serves as a valuable reference for this study.

By comparing the four models with Chen’s six-component framework, it becomes evident that emerging technologies primarily intervene in the areas of support, teaching, and curriculum (Fig. 6).

However, at the strategic level, emerging technologies have shown limited impact on the distribution of DEIs, degree types, and stakeholders.

To provide a more comprehensive understanding of these models, the authors conducted semi-structured interviews with various stakeholders. These discussions offer diverse perspectives and critical insights, contributing to a more nuanced interpretation of the models.

Challenges and suggestions in the integration of emerging technologies into design education

The author has organized the interview content into charts (Figs. 7 and 8) and provided explanations of the key points by referencing the interview transcripts (Appendix 3–5).

Shared resource modes in design education

Although emerging technologies have facilitated the distribution of educational resources in design education, significant challenges remain in practice-based courses, particularly regarding the need for physical spaces, face-to-face social interactions, and the preservation of cultural atmospheres, as well as the risk of exacerbating the digital divide due to technology dependence. Practice-based courses, such as prototype making and material perception, require in-person environments, as virtual technologies cannot fully replicate the experience of hands-on activities and direct material engagement. Online education also struggles to reproduce the social interactions, teamwork, and cultural atmosphere found on campuses, while face-to-face communication is crucial for fostering creativity, communication, and collaboration skills. Additionally, disparities in technological infrastructure between regions may further exacerbate inequalities in educational resource distribution. Underdeveloped areas often lack adequate hardware and network conditions, turning technology into a new barrier.

To address these challenges, establishing regional technology hubs and sharing hardware resources are considered viable solutions. For example, setting up regional practice centers or distributed educational hubs that combine online core courses with offline practical sessions can alleviate the infrastructure burden on individual institutions and expand access to high-quality resources. At the policy level, greater investment in infrastructure is needed, especially to enhance high-speed internet coverage and device availability in remote areas, with collaboration between governments and industries helping to bridge the digital divide. In terms of teaching, a blended approach that integrates online theoretical instruction with offline practical workshops is expected. This approach leverages the broad reach and flexibility of online education while preserving opportunities for face-to-face interaction, hands-on practice, and close industry collaboration.

Credentialing systems and Cross-Industry collaboration

As emerging technologies drive the evolution of degrees and certification formats, the current lack of standardized accreditation systems and the unstable market recognition of new qualifications have raised widespread concerns. Flexible forms of certification, such as micro-credentials and nano degrees, offer the advantage of quickly responding to industry changes, but their market acceptance varies, highlighting the urgent need to establish standardized certification systems and cross-enterprise, cross-institution credit transfer mechanisms to ensure students’ career development is not adversely affected. Meanwhile, the excessive fragmentation of degree types risks leading to knowledge fragmentation and the weakening of design thinking, underscoring the importance of maintaining systemic thinking and core design principles while deepening specialized skills. Additionally, due to the slower pace of academic reform compared to technological advancement, a gap has emerged between curriculum content and industry needs.

To address these issues, future design education must build more flexible and personalized learning pathways. This includes modular degrees and the cultivation of “T-shaped talents,” balancing foundational design literacy with technical expertise. Moreover, collaboration between universities, industry partners, and professional associations is essential to jointly establish certification standards for emerging fields. Cross-institution and cross-industry credit recognition systems are key to promoting lifelong learning and skills upgrading, with initiatives such as the European Union’s European Skills Passport (https://europass.europa.eu/en/what-europass-skills-passport) providing valuable references. Although enterprises may not be directly involved in course design, to ensure that new types of degrees remain competitive in the market, DEIs must strengthen their dialogue with industry, continuously updating curricula based on real market demands. This approach will foster a new generation of designers.

Ethical issues during IUR collaboration

In the collaboration between education and industry, it is crucial to remain cautious against the excessive influence of commercial interests on curriculum content and educational direction. Commercial pressures may lead to an over-reliance on specific technologies or software, resulting in homogenized teaching, restricted space for innovative thinking, and even the risk of DEIs becoming mere certification bodies. Furthermore, technology companies may indirectly shape curricula through product design, weakening the autonomy of universities and educators in course development. At the same time, students’ data privacy and intellectual property rights are at risk when using technology platforms, potentially compromising educational quality and academic integrity. Therefore, while promoting the integration of technology into education, it is essential to safeguard educational independence and uphold ethical standards.

To ensure academic independence and educational equity, DEIs must maintain leadership roles in partnerships with industry. They should establish governance mechanisms such as advisory boards and consortium committees to define the boundaries of intellectual property and data privacy, and to prevent excessive commercialization of curricula. In parallel, ethical review systems and guidelines for technology use should be established to protect student rights. Governments can further support this effort through funding initiatives and regulatory frameworks that set clear limits on corporate involvement in education, fostering a healthy integration of education and industry. Looking ahead, the promotion of open technological standards will be critical to preventing monopolies, ensuring platform interoperability, and encouraging DEIs and enterprises to collaborate.

Sustainable development to educational resource

Under the pressures of high costs and rapid technological iteration, the field of design education faces severe infrastructure challenges. Emerging technologies impose increasingly demanding requirements on hardware, with frequent updates to high-performance equipment, which forces DEIs to make recurrent investments in hardware upgrades and maintenance. However, utilization rates are often suboptimal, leading to resource wastage. Traditional education funding mechanisms struggle to keep pace with fast-changing technology cycles, exacerbating resource disparities between DEIs and limiting the widespread adoption of emerging technologies.

To address this issue, it is urgent to explore diversified funding sources, such as government subsidies, corporate sponsorships, and shared economy models, and to establish more flexible budgeting mechanisms to strengthen infrastructure development and enhance adaptability to technological change. DEIs should prioritize scalable, cloud-compatible hardware procurement strategies—for example, adopting a “cloud rendering + lightweight terminal” model to reduce investment costs. DEIs should also participate in policy pilot programs (such as technology sandbox projects) to access more flexible support. At the governmental level, dedicated budgets should be established to support educational technology updates, with special emphasis on supporting underdeveloped regions, while also collaborating with industry to develop legal and ethical frameworks for AI copyright, data security, and related issues. Enterprises can contribute by offering hardware leasing or subscription-based services (such as Hardware-as-a-Service model, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/hardware-as-a-service), helping DEIs reduce procurement burdens.

Teaching that balance Human–AI collaboration and traditional skills

Overreliance on technology may lead to a weakening of students’ fundamental design skills, such as hand-drawing and physical prototype-making, which are increasingly being overlooked. Moreover, the integration of technology could diminish the emotional connection between teachers and students, reducing the importance of face-to-face mentorship and, in turn, eroding the core values of design thinking and humanistic care that are central to design education. At the same time, the inherent instability of technological systems—such as equipment failures and network interruptions—can disrupt teaching activities, highlighting the need for contingency plans to ensure the continuity of instruction. These perspectives remind us that while taking advantage of the conveniences brought by emerging technologies, it is crucial to remain alert to risks.

To address these challenges, the DEIs community advocates for the development of human-machine collaborative teaching models. Teachers are encouraged to shift from traditional knowledge transmitters to designers of learning experiences and must receive training in new educational technologies. A dual-track teaching model should be promoted, combining the use of technological tools with the cultivation of traditional skills, allowing AI to assist in standardized task while teachers focus on fostering creativity and providing personalized guidance. At the same time, foundational courses should be retained to strengthen students’ sensory and hands-on abilities. Exploration of multimodal interaction technologies that integrate tactile and visual feedback should be encouraged to enhance virtual learning experiences. On the policy side, support should be given to hybrid teaching pilot projects, with dynamic evaluations of technological applications to ensure the achievement of educational quality and learning objectives.

A dynamic curriculum framework balancing technology and ethics

As design education continues to shift towards greater technological integration, the overemphasis on technology introduces multiple risks. While emerging technologies have enhanced students’ competitiveness, excessive reliance on technical tools can undermine the importance of traditional design training. This may lead to fragmented curricula and weaken the cultivation of critical thinking and humanistic care. In technology-driven curriculum reforms, it is essential to establish evaluation systems that balance technical rationality with ethical awareness, preventing students from focusing solely on efficiency and tool usage while neglecting the social responsibilities and ethical reflections. Technology should not dominate the creative process, adhering to the principle that technology must serve creativity. At the same time, faculty development and resource allocation face challenges, requiring initiatives such as introducing “technology teaching assistants” and establishing “technology transfer teaching studios” to strengthen teachers’ technological literacy.

DEIs need to build dynamic curriculum frameworks that balance technology and ethics, regularly reviewing and adjusting course content to ensure both scientific rigor and forward-looking relevance. Strengthening IUR collaboration is crucial to co-develop technical modules, helping bridge the technological gap among educators. At the policy level, support can be provided through funding interdisciplinary pilot programs and promoting joint IUR certification mechanisms, ensuring curricula align with industry demands. Additionally, emerging technologies can be leveraged to analyze employment data and design case studies in real-time.

Limitations

Although this study explored the integration models of emerging technologies in the strategic development of DEIs through a combination of textual analysis and semi-structured interviews, several limitations remain:

First, due to constraints in sample accessibility and language differences, the study exhibits regional bias. DEIs from Africa and Latin America are underrepresented, which may affect the comprehensiveness of the global understanding of technology integration in design education.

Second, although semi-structured interviews were used to enhance the explanatory power of the quantitative findings, the number of interviewees was limited and concentrated in high-ranking educational institutions. The experiences of vocational and regional universities were not adequately captured, which limits the generalizability of the results across different tiers of institutions.

Third, while the study identified four models, it did not conduct quantitative assessments of causal mechanisms or educational outcomes associated with each model. There is a lack of in-depth discussion on questions such as “which model is more effective” or “under what conditions a specific model is more suitable.”

Lastly, in the dimension of ethics and governance, although numerous challenges were highlighted through interviews, the study has not yet established an actionable ethical evaluation framework.

Conclusion

Through empirical research, the authors have addressed the two proposed scientific questions.

Firstly, taking the strategic development of DEIs as its perspective, this study analyzed four models through which emerging technologies are integrated into design education: lab-driven innovation, industry incubation, interdisciplinary fusion, and curriculum integration. These models reflect the multifaceted roles of emerging technologies—as tools, media, and forms of knowledge—and reveal that their influence is concentrated in the areas of support, pedagogy, and curriculum. However, their penetration at the strategic level—particularly in dimensions such as regional planning of resource, degree types, and stakeholder types, remaining limited.

Secondly, the semi-structured interview also revealed that while the widespread application of emerging technologies is reshaping design education, it presents a range of systemic challenges, including resource disparities, technological dependency, unclear accreditation systems, and ethical risks. In particular, during strategic planning, DEIs must uphold academic independence, remain cautious against excessive commercial influence, and carefully manage the power dynamics among diverse stakeholders—including technology providers, faculty systems, and policy mechanisms.

In the future, the technological transformation of design education should evolve toward a resource framework characterized by “regional sharing + policy support”, a degree system based on “modular structure + credit recognition”, a teaching paradigm grounded in “human–AI collaboration”, a curriculum optimization mechanism “driven by industry feedback”, and a governance framework built on “co-development of technological ethics”. Together, these pathways aim to foster sustainable and high-quality development in design education.

Data availability

The data is included in this paper.

References

Shi, Y. et al. Understanding design collaboration between designers and artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review. In J. Nichols (Ed.), Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 1–35). Association for Computing Machinery. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1145/3610217

de Freitas, F. V., Gomes, M. V. M. & Winkler, I. Benefits and challenges of virtual-reality-based industrial usability testing and design reviews: A patents landscape and literature review. Appl. Sci. 12 (3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031755 (2022).

Santi, G. M. et al. Augmented reality in industry 4.0 and future innovation programs. Technologies 9 (2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies9020033 (2021).

Tuvayanond, W. & Prasittisopin, L. Design for manufacture and assembly of digital fabrication and additive manufacturing in construction. Rev. Build. 13 (2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020429 (2023).

Lin, X. F. et al. Teachers’ perceptions of teaching sustainable artificial intelligence: A design frame perspective. Sustainability 14 (13), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137811 (2022).

Faludi, J. et al. Sustainability in the future of design education. She Ji: J. Des. Econ. Innov. 9 (2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2023.04.004 (2023).

Wu, R. et al. Key factors influencing design learners’ behavioral intention in Human-AI collaboration within the educational metaverse. Sustainability 16 (22), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229942 (2024).

Al-Ansi, A. M. et al. Analyzing augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) recent development in education. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open. 8 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100532 (2023).

Le Masson, P., Weil, B. & Hatchuel, A. Strategic Management of Innovation and Design (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Brosens, L. et al. How future proof is design education? A systematic review. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 33, 663–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09743-4 (2023).

Shih, Y. T. & Sher, W. Exploring the role of CAD and its application in design education. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 18 (6), 1410–1424. https://doi.org/10.14733/cadaps.2021.1410-1424 (2021).

Tang, T., Li, P. & Tang, Q. New strategies and practices of design education under the background of artificial intelligence technology: Online animation design studio. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.767295 (2022).

Zhou, C., Zhang, X. & Yu, C. How does AI promote design iteration? The optimal time to integrate AI into the design process. J. Eng. Des. 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544828.2023.2290915 (2023).

Menon, S. & Suresh, M. Factors influencing organizational agility in higher education. Benchmark. Int. J., 28(1), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-04-2020-0151

Mortati, M. et al. Data in design: How big data and thick data inform design thinking projects. Technovation, 122, (1–14). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102688 (2023).

Oliveira, G. et al. An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Edu. Technol. 52, 1357–1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13112 (2021).

Schwoerer, K. Designing with end-users in mind: principles and practices for accessible, usable, and inclusive open government platforms. Res. Handb. Open. Government. 239–252. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781035301652.00025 (2025).

Gao, Y. et al. The role of virtual reality technology in medical education in the context of emerging medical discipline. J. Sichuan Univ. (Medical Sci. edition). 52 (2), 182–187. https://doi.org/10.12182/20210260301 (2021).

Li, X., Wu, Z. & Gan, W. The influence of new educational technology system represented by artificial intelligence on planning education. Res. High. Educ. Eng., (1), (pp. 47–53 ). (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Effectiveness of virtual reality technology in rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 20 (3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314766 (2025).

Hajirasouli, A. & Banihashemi, S. Augmented reality in architecture and construction education: State of the field and opportunities. International J. Educational Technol. High. Education. 19, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00343-9 (2022).

Enamorado-Díaz, E. et al. Metaverse applications: Challenges, limitations and opportunities—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 182, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2025.107701 (2025).

Stasolla, F. et al. Combined deep and reinforcement learning with gaming to promote healthcare in neurodevelopmental disorders: A new hypothesis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 19, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2025.1557826 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Investigating virtual reality for alleviating human-computer interaction fatigue: A multimodal assessment and comparison with flat video. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 31 (5), 3580–3590. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2025.3549581 (2025).

Papadaki, E. & Watson, D. Integrating personalised learning in a school of design: The role of practice-based research, emerging technologies, and interdisciplinary collaboration. In E. Papadaki & D. Watson (Ed.), Integrating Personalized Learning Methods Into STEAM Education. IGI Global. (2025). https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-7718-5.ch010

Ye, X. et al. Authentic or artificial intelligence? Faculty’s perspectives on the chatgpt’s impact on U.S. Urban planning Ph.D. Programs. Front. Urban Rural Plann. 2, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44243-024-00046-x (2024).

Shahidi Hamedani, S., Aslam, S. & Shahidi Hamedani, S. AI in business operations: Driving urban growth and societal sustainability. Front. Artif. Intell. 8, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2025.1568210 (2025).

Yim, I. H. Y. & Su, J. Artificial intelligence (AI) learning tools in K-12 education: A scoping review. J. Comput. Educ. 12, 93–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00304-9 (2025).

Mai, X. T. & Nguyen, T. Trust in Generative Artificial Intelligence (Routledge, 2025).

Peikos, G. & Stavrou, D. ChatGPT for science lesson planning: An exploratory study based on pedagogical content knowledge. Educ. Sci. 15 (3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030338 (2025).

Borenstein, J. & Howard, A. Emerging challenges in AI and the need for AI ethics education. AI Ethics. 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-020-00002-7 (2021). 1.

Holmes, W. et al. Ethics of AI in education: Towards a community-wide framework. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 32, 504–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-021-00239-1 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 252, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124167 (2024).

Yang, W. Artificial intelligence education for young children: Why, what, and how in curriculum design and implementation. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 3, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100061 (2022).

Weng, X. et al. Satisfying higher education students’ psychological needs through case-based instruction for fostering creativity and entrepreneurship. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04597-2 (2025).

Grizioti, M., Kynigos, C. & Nikolaou, M. S. Enhancing computational thinking with 3D printing: Imagining, designing, and printing 3D objects to solve real-world problems. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1145/3628516.3655810

Mensah, N. & Adukpo, T. K. Financial technology and its effects on small and medium-scale enterprises in ghana: An explanatory research. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Acc. 25 (3), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajeba/2025/v25i31709 (2025).

Cui, Y. et al. A survey on big data-enabled innovative online education systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Innov. Knowl. 8 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100295 (2023).

Cantabella, M. et al. Analysis of student behavior in learning management systems through a big data framework. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 90, 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2018.08.003 (2019).

Giannakos, M., Horn, M. & Cukurova, M. Learning, design and technology in the age of AI. Behav. Inform. Technol. 44 (5), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2025.2469394 (2025).

Rasheed, T. et al. Leveraging AI to mitigate educational inequality: Personalized learning resources, accessibility, and student outcomes. Crit. Rev. Soc. Sci. Stud. 3 (1), 2399–2412. https://doi.org/10.59075/j4959m50 (2025).

Al-Kamzari, F. & Alias, N. A systematic literature review of project-based learning in secondary school physics: Theoretical foundations, design principles, and implementation strategies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04579-4 (2025).

Su, H. & Mokmin, N. A. M. Unveiling the canvas: Sustainable integration of AI in visual Art education. Sustainability 16 (17), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177849 (2024).

Sarapak, C. et al. Applying the TPACK framework to enhance instructional design for high school students in Surin province: A needs analysis and improvement strategy. J. Innov. Adv. Methodol. STEM Educ. 2 (1), 10–24 (2025).

Demir, F. et al. Strategic improvement planning in schools: A sociotechnical approach for Understanding current practices and design recommendations. Manage. Educ. 33 (4), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/08920206198476 (2019).

Huangfu, J. et al. Fostering continuous innovation in creative education: A Multi-Path configurational analysis of continuous collaboration with AIGC in Chinese ACG educational contexts. Sustainability 17 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010144 (2025).

Gropius, W. The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (MIT Press, 1965).

Droste, M. Bauhaus (Taschen, 2006).

Wrigley, C. & Mosely, G. Design Thinking Pedagogy: Facilitating Innovation and Impact in Tertiary Education (Routledge, 2019).

Li, T. & Zhan, Z. A systematic review on design thinking integrated learning in K-12 education. Appl. Sci. 12 (16), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168077 (2022).

Dewey, J. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking To the Educative Process (Heath & Co, 1933).

Schön, D. A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (Routledge, 1992). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

Pandolfo, B., Bohemia, E. & Harman, K. Rediscovering Apprenticeship Models in Design Education. In Proceedings of the 6th European Academy of Design Conference: Designing Critical Design, 1–10 (2005).

Crawford, T. C. Foundations of American Design Education (North Carolina State University, 2013).

Lou, Y. Q. & Ma, J. A Three-Dimensional T-Shaped design education framework. In Emerging Practices: Professions, Values, and Pathways in Design, 228–251 (eds Ma, J. & Lou, Y. Q.). China Architecture & Building (2014).

Chen, F. Research on systems for doctoral education in design. Des. J. 25 (4), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2088099 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Funding

This research was funded by CHINA POSTDOCTORAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (GZC20231938); International Science and Technology Cooperation Project of the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development of China (H20220017); National Natural Science Foundation of China (52308082). The APC was funded by TONGJI UNIVERSITY.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and Z.L.; methodology, F.C.; software, F.C.; formal analysis, F.C., X.L. and Z.L.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, F.C.; supervision, Z.L.; funding acquisition, F.C. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research procedures involving human participants have been approved by the interviewees and ethical related approval of Tongji University, which are also in accordence with 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Lin, Z. & Li, X. Research on the emerging technological intervention models in design education from a strategic perspective of global design education institutions. Sci Rep 15, 41366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25272-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25272-1