Abstract

Stigma is a prevalent sociocultural phenomenon that substantially negatively affects individuals with anxiety disorders. This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale (SASS) using Rasch analysis and to employ this instrument in assessing stigma among Chinese adults diagnosed with anxiety disorders. The Rasch analysis incorporated multiple psychometric evaluations. Additionally, multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify factors independently associated with stigma. Rasch analysis demonstrated that the 6-item Chinese version of the SASS showed good measurement properties. It demonstrated unidimensionality, with well-fitting items and logically ordered response categories. Differential item functioning analysis revealed cross-gender measurement invariance. The results showed that family history of mental illness (β=-0.277, P < 0.001), objective support (β=-0.357, P < 0.001), and subjective support (β = 0.330, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with stigma. In summary, the psychometric evaluation results of the Chinese SASS met standard criteria, supporting its use as a valid tool for assessing anxiety stigma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety Disorder (AD) is the most common mental health problem, which is commonly found in two forms: General anxiety disorder (GAD) and Panic disorder (PD)1. The lifetime prevalence in the Chinese population is about 7.6%2, and showing an upward trend. In traditional Chinese culture, the concept of “face” is deeply rooted, and people find it difficult to talk about issues related to mental illness3. There is an inherent public bias and discrimination against mental illnesses such as anxiety disorders, and as a result, there is a stigma associated with anxiety disorders4. Available evidence indicates that the stigma faced by individuals suffering from anxiety disorders is on par with that encountered by patients with other psychological disorders5,6. Stigma represents a complex, multidisciplinary challenge spanning sociology, medicine, psychology, and related fields. It has evolved into a widespread sociocultural phenomenon with significant detrimental effects on patients with anxiety disorders4,7. Notably, stigma had stood as one of the primary reasons behind the low consultation rates and suboptimal treatment outcomes among individuals with anxiety disorders2,8,9. Therefore, we must prioritize addressing the stigma surrounding individuals with anxiety disorders, encompassing both the development of objective assessment methodologies and the implementation of strategies to alleviate and reduce this stigma.

Some recent systematic reviews in the realm of stigma research have revealed a significant underrepresentation of anxiety disorders, particularly in the discussion of their stigmatization and the barriers encountered in their treatment3,6,10. Dr. Casey A. Schofield5 focused on the research of stigma in people with anxiety disorders, and compiled the Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale in 2020, which is a single-dimensional scale with 7 items, scoring in the form of percentage, each topic has 5% points of “0%-25%-50%-75%-100%”, totaling a score of 0 to 10 points. A score of 0 signifies complete disagreement, while a score of 10 indicates strong agreement with the corresponding statement, and a score of 70 indicates higher stigma. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.88, demonstrating its good internal consistency and reliability. It is a widely acknowledged fact that patients suffering from anxiety disorders often tend to conceal their genuine thoughts and feelings. Consequently, traditional direct measurement methods may encounter difficulties in accurately capturing the subjects’ thoughts and attitudes towards stigma, thereby resulting in assessments that fail to truly reflect the severity of their stigmatization11. To address this issue, the Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale employed an indirect and covert survey methodology. By framing the questionnaire as a knowledge-based assessment on anxiety disorders, it strategically concealed its primary objective of evaluating stigma. This approach facilitated a more accurate quantification of the actual prevalence and intensity of stigma associated with anxiety, as respondents were less inclined to modify their responses due to awareness of the assessment’s true purpose11.

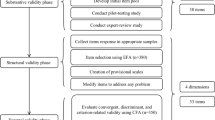

Dr. Casey A. Schofield’s group5 followed a rigorous scale development methodology, with qualitative research and measurement tests resulting in scales that are scientifically valid and highly usable. While the assessment of stigma among individuals with mental illness in China has primarily focused on conditions such as depression and schizophrenia, with research gradually expanding toward psychological interventions. Relatively little attention has been paid to anxiety disorders, which remain in an early, exploratory phase of investigation12. In our previous research, we obtained the consent of the scale’s original designers to adapt the tool for the Chinese context and assess its reliability. Tests among Chinese adults showed that the content validity index(S-CVI) was 0.902, and the cumulative variance contribution rate was 54.754%. The Perceived Devaluation - Discrimination Scale and the Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale were used to test the calibration validity, showing moderate correlation. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.719 and the retest reliability 0.855. Confirmatory factor analysis also showed that the model fitted well. The findings revealed that the Chinese version of the scale exhibited logical measurement outcomes among the Chinese population. However, item 4 of the original Chinese version of the scale showed unsatisfactory results in terms of structural validity. Therefore, in view of the scale’s popularized use in the Chinese population, it is necessary not only to validate entry 4 again, but also to rigorously conduct the measurement test again13.

While previous validations of the SASS, including our own earlier work in, have established its general reliability and factorial structure, the current study extends this evidence in several important ways. Unlike prior studies that relied primarily on Classical Test Theory, this validation utilized Rasch analysis, which provides interval-level measurement, rigorous examination of unidimensionality, and detailed evaluation of item-level performance, offering a more nuanced and sample-independent assessment of the scale’s psychometric properties. Our analysis included explicit examination of differential item functioning by gender, ensuring that the scale performs consistently across subgroups14,15. In addition to examining reliability and validity metrics, this study identified specific predictors of stigma using multivariate regression, thereby connecting psychometric evaluation with clinically actionable insights.

Rasch analysis is a statistical method widely used in the evaluation of the reliability and validity of measurement scales, particularly in the fields of psychology and sociology16,17. Rasch analysis offers distinct advantages over traditional validation methods such as Classical Test Theory in evaluating measurement scales18,19. While Classical Test Theory remains useful for initial assessments of reliability and dimensionality, Rasch analysis delivers a more robust, linear, and clinically interpretable metric, enabling finer-grained insights into individual item performance and person measures. This makes it particularly valuable for developing and refining scales intended for use in individualized measurement, such as in clinical assessment or patient-reported outcomes20,21. To date, Rasch analysis has been applied to the scales of stigma16, but there have been no accounts of Rasch analysis evaluating the Chinese version of The Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale.

Therefore, to address the critical gap in culturally and psychometrically robust instruments, our study applied Rasch analysis to validate the anxiety stigma scale before its implementation in Chinese adults. This methodological approach provides a foundation for enhancing the precision and cultural appropriateness of anxiety stigma research in this population.

Methods

Study populations and procedure

Convenience sampling was used to select adults and undergraduate students from a large hospital health management center and a university in China in 2024.Participants were briefed on the study’s objectives, significance, and procedural requirements by two trained researchers using a standardized protocol. Following the provision of informed consent, participants were instructed to complete the electronic questionnaire independently and with honesty. Prior to this, the researchers explicitly communicated the principles of confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntary participation to ensure the ethical rights and interests of all participants were rigorously upheld. Exclusion criteria encompassed individuals under the age of 18 and those lacking adequate reading, writing, and communication abilities. The electronic questionnaires submitted by participants were retrieved from the survey platform, systematically organized, and summarized by an independent researcher. The compiled data were subsequently verified by the two administering researchers to guarantee the authenticity and accuracy of the study findings. The study procedure was granted approval by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (approval number: 2021-K051) and rigorously adhered to the principles of confidentiality, non-maleficence, and informed consent, in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Demographic information

The participant information collected included: age, family history of mental illness, educational level, religion, BMI, chronic disease, tobacco use, alcohol use, and residence.

Overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS)

The scale has 5 items, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.930. This brief measure assesses symptoms across anxiety disorders. The scoring range for each item is from 0 to 4, and a cutoff score of 8 is used. A total self-assessment score above 8 is considered indicative of anxiety disorder22.Cronbach’s alpha from the current study sample was 0.773.

Chinese version Skidmore anxiety stigma scale (The Skidmore anxiety stigma scale, SASS)

Dr. Casey A. Schofield’s group5 followed a rigorous scale development methodology developed The Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale in 2020, and our research team obtained the right to use the scale in 2021, applying the original scale to the Chinese population after Chemicalization and cultural adaptation. After being validated through the Rasch model in our study, resulted in the Chinese-version scale consisting of 7 items. Each item’s answers are scored according to the corresponding values of “0-25-50-75-100,” and the total score is calculated by summing the scores of all items and then dividing by 10. All items use a positive scoring method, with a score range of 0 to 70.A score of 0 indicates the absence of stigma. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety stigma among the participants.

Attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help (ATSPPH-SF)

This scale consists of 10 descriptive sentences within a single dimension, encompassing items like “I would be embarrassed to seek professional psychological help”, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.780. It employs a Likert 4-point rating scale, ranging from 0 (disagree) to 3 (agree), where a higher score indicates a more positive attitude of the respondents towards seeking professional psychological help23.Cronbach’s alpha from the current study sample was 0.790.

Social support rating scale (SSRS)

The SSRS comprises three dimensions: support utilization, subjective support, and objective support, encompassing items like “How many close friends do you have who could provide support and assistance?” Scores on this scale span from 11 to 66, with higher scores indicating a greater perception of social support24.Cronbach’s alpha from the current study sample was 0.782.

Sample size calculation

Rasch analysis: A relatively stable Rasch model generally requires a sample size of more than 200 cases. Considering approximately 10% of invalid questionnaires, a sample size of 220 cases was required. Multivariate analysis: According to methodological standards, the minimum sample size should be 10–20 times the number of independent variables. With planned inclusion of 15 variables and considering approximately 10% invalid questionnaires, the calculated sample size was 165–330 cases.

Statistical analysis

The Rasch analysis was performed using the WINSTEPS software, Version 3.72.3. The psychometric qualities tested by the Rasch analysis were: (1) Unidimensionality: Rasch analysis examines dimensionality based on principal components of the residuals (PCA) in WINSTEPS software. The first criterion for unidimensionality was that the variance explained by the measurement dimension be at least 40%25, and unexplained variance in the first extracted component should account for a small percentage of the remaining variance (less than 5%). (2) Infit and outfit MNSQ were used to indicate the fitness of items, and values less than 2.0 were considered acceptable for model fit26. The Point Measure Correlation is used to assess the direction and strength of the relationship between an item and the latent trait measured by the entire scale. The ideal and robust acceptable range for this statistic is 0.4 to 0.8. If the value is too low, it indicates a weak relationship between the item and the latent variable, resulting in poor discrimination among respondents. This may suggest that the item measures a slightly different dimension or is ambiguously worded. In such cases, modification or deletion of the item is recommended. Item 4 exhibited a point-measure correlation value of 0.09, so the entry is deleted.(3) Threshold Values and Category Fit: Thresholds should increase by at least 1, 4 logits between categories but not more than 5 logits to avoid large gaps27.Theoretically the level difficulty increases monotonically with the level of the option, and the thresholds for each entry should be ranked from smallest to largest. The entry options in this study were Likert level 5, so 4 thresholds existed(β1<β2<β3<β4)28. (4) Differential Item Functioning (DIF): A test item behaves differently between two groups despite measuring the same underlying trait29. (5) The Wright map illustrated the test items ranked based on individual ability, offering a visual synopsis of the distribution of item difficulty and personal ability, both represented on the same logit scale interval30. (6) Person Separation Index (PSI) serves as a crucial reliability metric in Rasch analysis, which is similar to Cronbach’s alpha. Once the individual items are deemed satisfactory, the overall fit to the model is acceptable, and unidimensionality is validated, the Rasch analysis is considered complete30. Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 26.0 in this part. Descriptive analysis: Kolmogorov–Smirnov, skewness and kurtosis was used to test the normality of data distribution. Skewed distributions were described utilizing descriptive statistics, which were represented as medians (25th and 75th percentiles). Univariate analysis: Spearman correlations were used to analyze the relationship between anxiety stigma and social support, and attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help. Non-parametric test method was used to compare the difference and single factor analysis of stigma in participates. Mann–Whitney U test was used for two independent samples, and Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for several independent samples. Multivariate analysis: the variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in a multiple linear regression model to analyze the factors affecting the anxiety stigma. False discovery rate was used to recalibrate the results of multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

Participants

This study randomly enrolled 1000 participants, of which 225 were deemed anxious with an OASIS score exceeding 8. Consequently, the sample size for the Rasch analysis and validation phase in this study comprised 225 individuals, including 99 males (44%) and 126 females. The second component of the study involved an analysis of the risk factors associated with anxiety-related stigma, and a total of 162 fully completed questionnaires were ultimately obtained for this phase of the investigation, of these, 71 males(43.82%),148 participants<45years old (91.36%),90 participants had bachelor’s degree or above(55.56%),47 participants had chronic diseases(20.01%),and 54 participants had family history of mental illness (33.33%) (Table 2).

Results of Rasch analysis

This result of Principal Component Analysis basically supports the conclusion that the scale was unidimensional. The thresholds for each entry were ranked from smallest to largest. By comparing the distribution of person’s ability and item difficulty, person’s ability and item difficulty concentrated in the range (–1.0–+1.0). In this sample, the person reliability was 0.73 and item reliability was 0.94, which demonstrates that the scale possesses excellent measurement stability. The results of the model constructed on the scale for the 6 items are as follows: (1) The PCA of the standardized residuals showed that the proportion of variance explained by the SASS was 52.6%, substantially in line with recommended values. The ratio of the variance in the measurement dimension compared to the variance of the first principal component was 3.75:1. Part of the reason for the high level of unexplained variance was thought to be due to the small number of items on the Skidmore Anxiety Stigma Scale. This result basically supports the conclusion that the scale is unidimensional31. (2) Fit statistics showed no redundancy or outliers among the items. Infit mean square varied between 0.72 and 2.25, and outfit mean square varied between 0.71 and 2.03. The point-measurement correlation value of each item was between 0.43 and 0.76, which indicate that the fit of the items to the measurement target meets statistical criteria (Table 1). (3) The thresholds between the two neighboring options are respectively: β1=-0.94, β2=-0.50, β3=-0.04, β4 = 0.27, which requirements met: β1<β2<β3<β4, indicating that the response options of the scale are appropriately structured.(4) DIF: Analysis of the DIF based on the SASS for gender in participants showed that the uniform DIF item ranged from − 0.10 to 0.06 (P > 0.05).The scale demonstrated measurement invariance across genders.(5) As depicted in Fig. 1, the Wright map presents the joint person and item representations along the latent variable in the identical common metric scale that expresses item difficulty from negative infinity to positive infinity (often ranging from − 1 to 1 logits), indicated that the level of difficulty in answering the items were reasonable. The 6 items of the SASS are plotted in descending order of difficulty from easiest (Item 3 on the bottom) to most difficult (Item 4 at the top) on the right side of the map. (6) PSI: The PSI was 0.73, which is analogous to Cronbach’s alpha in classical test theory, indicates acceptable reliability for group-level comparisons.

Scores and correlations of stigma, social support, and attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help in participants with anxiety disorders

Participants’ anxiety sickness stigma scores were 30(14.5,37.5), minimum-maxmum:0-52.5. The score of ATSPPH-SF was 17(15,23), objective support 8(6,8), subjective support 15(12,18), support utilization 6(5,7). The correlation between stigma and ATSPPH-SF was (r =-0.683, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Multivariate linear regression results of the factors associated with stigma on participants with anxiety disorders

The results of univariate analysis on the factors of stigma in participants with anxiety disorders showed that there were differences in 5 variables. Age (Z = -2.146, P = 0.032), educational level (Z = -2.929, P = 0.003), religion (Z = -2.227, P = 0.026), family history of mental illness (Z =-4.361, P < 0.001), and blood (Z = 11.982, P = 0.007) had effects on stigma. Psychosocial characteristics associated with stigma were objective social support (r = 0.221, P = 0.005), and subjective social support (r = 0.351, P < 0.001) (Table 2). The results showed that family history of mental illness (β=-0.277, P < 0.001), objective support (β=-0.357, P < 0.001), and subjective support (β = 0.330, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with stigma. Additionally, although the results of multiple regression indicate that education was a factor influencing stigma, the model corrected using FDR (False Discovery Rate) showed that P > 0.05. Therefore, we did not consider education to be one of the influencing factors (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, item analysis theory was used to further measure the SASS, and after modeling, a 6-item version of the Chinese version of the scale was formed. Compared with the 7-item version, the final 6-item version demonstrated relatively superior model fit indices and enhanced psychometric properties. This study represents the first comprehensive item-analytic and psychometric evaluation of the SASS within a Chinese population. The reliability indices for the scores met the requisite thresholds. This result supports the applicability of the SASS as a source of robust scores for assessing stigma in this demographic.

SASS is a unidimensional assessment tool, and this unidimensionality is crucial for ensuring that the scale measures a specific psychological construct without interference from extraneous factors25. Compared to original validation works, this study adopted item analysis theory to conduct a more rigorous validation process. Building on earlier findings, we made the careful decision to remove original item 4. Our previous study on the Chinese version similarly revealed suboptimal factor loading for Item 4 in exploratory factor analysis. Furthermore, in the current validation study, this item demonstrated inadequate performance in item response theory-based tests. Given its consistently unsatisfactory psychometric performance across both methodological approaches, the final exclusion of Item 4 was determined to enhance the scale’s applicability within Chinese populations32. Rasch analysis results demonstrate that the items in the assessment tool exhibit good fit to the statistical criteria, with no redundancy or outliers, acceptable Infit and Outfit mean square values, and moderate to strong point-measurement correlations, provide evidence supporting the validity and reliability of the items33.

The slightly higher values (up to 2.25 for infit and 2.03 for outfit) may indicate minor deviations from the model, but they are not severe enough to warrant concern34. These deviations could be due to slight inconsistencies in responses. SASS possesses monotonically increasing properties that justify the 5-point scale. Additionally, Rasch analysis conducted to examine DIF based on the survey of attitudes toward SASS for gender among participants revealed that the SASS is free from gender-based bias35. In contrast to the previous confirmatory factor analysis, establishing measurement invariance indicates that the psychological construct being measured exhibits equivalent structure and meaning across genders, thereby supporting its universality. The White graph analysis in this study revealed that participants’ response distributions were predominantly concentrated in the central region, which further supports the construct validity of the instrument. Furthermore, the alignment and near-parallelism between the mean response values of participants and the mean difficulty levels of the scale items indicate that the scale effectively spans the full spectrum of the target population’s scores. This implies that the scale items are capable of comprehensively capturing the psychological traits of the sampled population. The most difficult item for the participants was Item 4 (“What’s the percentage of patients with anxiety disorders attracting others’ attention through their symptoms?”). The easiest item was Item 3 (“What’s the percentage of anxiety sufferers who are too weak to overcome their symptoms?”), indicating that it reflects a common and readily acknowledged core experience within this population. This can serve as an empathic foundation for psychological counselors to connect with patients, as well as a focal point for treatment and an effective entry point for intervention36. Overall, the results of the SASS Rasch analysis test met the criteria for the measurement scale, and the optimized 6-item SASS in this study has practicality and generalizability for use in the measurement of anxiety stigma.

Participants’ anxiety disorder stigma scores were 30(14.5,37.5), which mean that the severity of anxiety disorder stigma is moderately severe. Consistent with previous findings, participants with high levels of anxiety disorder stigma had low intentions to seek professional psychological help2,5,37. Therefore, accurate assessment and alleviation of stigma is necessary to improve attendance and treatment outcomes for anxiety disorders. This study next applied the SASS to survey participants to obtain variables that may influence anxiety stigma, and the results of the multiple linear regression analysis showed that a family history of mental illness, low levels of objective social support, and high levels of subjective social support were identified as significant factors for severe stigma experienced by individuals with anxiety disorders.

Firstly, genetic analysis indicated that a family history of mental illness might increase a patient’s genetic susceptibility to anxiety, which in turn heightened stigma38. Secondly, Stigma theory posits that society tends to attribute anxiety to “family heredity” or “failed family education.” Similarly, individuals with a family history may be more inclined to define themselves through the lens of their diagnosis, “I was born this way”, rather than viewing the condition as a manageable health issue39. Additionally, from the perspective of patients’ self-perception, patients tended to be more sensitive to their own mental health due to their family history of the disease, worrying that they would be viewed in the same way, which led to increased stigma40.

The association between objective social support and stigma observed in this study was consistent with findings from previous research, indicating that low levels of objective social support served as a contributing factor to heightened stigma among participants with anxiety disorders41. Social support is a crucial factor in alleviating stress and improving mental health. When individuals with anxiety disorders experienced low levels of objective social support, they often lacked practical emotional, informational, or material assistance, which led to a diminished ability to cope with anxiety42. This absence of support left them feeling isolated and helpless, thereby exacerbating their sense of stigma and reinforcing beliefs that they were misunderstood or unaccepted by others. Scholarly research showed that the establishment of an Internet information management platform and online information interventions for patients were effective in alleviating the sense of shame in patients with anxiety disorders43. It was suggested that healthcare professionals could invest in online interventions to discover better ways to alleviate stigma.

The conclusions of previous studies were consistent, suggesting that patients with a high sense of social support were less likely to perceive feelings of illness and stigma44. However, few studies had discussed social support categorically, and the present study analyzed objective and subjective support separately, with the interesting result that participants with high levels of subjective social support perceived a more severe sense of anxiety stigma. This observed association between high subjective social support and an increased sense of stigma among individuals with anxiety disorders can be explained through the following psychological theories. Based on the social comparison theory perspective45, people with anxiety disorders felt high levels of social support, but they compared themselves to “normal” people and perceived their anxiety symptoms as a sign of abnormality or weakness, resulting in a sense of stigma. Classical self-stigmatization theory suggested that individuals internalized negative social stereotypes of mental illness39, leading to self-depreciation. Individuals with anxiety disorders internalized negative societal stereotypes of anxiety, such as “fragile,” “incompetent”. Moreover, heightened social support may paradoxically intensify their concern about others’ perceptions, due to increased fear of being negatively labeled. From the perspective of attribution theory46, it was proposed that individuals with anxiety disorders tended to attribute the receipt of social support to their own perceived “neediness” or “pathology,” a cognitive bias that potentially exacerbated feelings of shame. Consequently, despite experiencing high levels of subjective social support, individuals with anxiety disorders frequently endured significant stigma, influenced by mechanisms such as social comparison, self-stigmatization, attachment-related conflicts, and maladaptive attributions. This phenomenon reflected the complex relationship between social support and stigma. Previous studies lacked robust theoretical evidence to substantiate this finding, and the present study merely provided a plausible explanation for the observed results, while the causal relationship remained to be elucidated through further research. Additionally, this finding suggested that healthcare professionals need to be careful in evaluating psychological therapies that increase social support before adopting them, as the psychological impact of such approaches on individuals with anxiety disorders was not yet fully understood.

This study resulted in a measure of anxiety disorder stigma that is applicable to the Chinese population. It is crucial to emphasize that the findings of this study are designed to establish reliable measurement tools for the clinical management of anxiety disorders, which serve as essential instruments for evaluating the efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions. Previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of a novel psychological intervention, termed the “Coping Internalized Stigma Program” (PAREI)47, an integrative approach including psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and mutual support, in addressing stigma among patients with mental illness. This finding underscores the imperative for healthcare professionals to incorporate innovative therapeutic approaches to develop comprehensive, multidisciplinary psychological intervention programs.

Limitations

Firstly, this study ensured the adequacy and comprehensiveness of the assessment of stigma and help-seeking intentions through extensive collection of questionnaire data. However, the findings may have certain limitations due to the constrained sample size. Secondly, compared to using clinical diagnosis as an inclusion criterion, the use of OASIS as a screening tool is methodologically less rigorous. While this approach can efficiently identify individuals with significant anxiety symptoms, it may include false positives. Consequently, the generalizability of our Rasch analysis results to formally diagnosed clinical populations may be limited. Future studies should consider incorporating standardized diagnostic interviews to confirm anxiety disorder diagnoses. Thirdly, the use of a convenience sample may limit the generalizability of our findings. The participants may not be fully representative of the broader community, which could introduce selection bias. Future studies should employ more robust and representative sampling strategies, to confirm and extend our results. Fourthly, in the present study, measurement invariance was tested only across gender groups. Future studies with an expanded sample size should examine invariance across key socio-demographic variables such as socioeconomic status and educational attainment. Given that stigma may fluctuate over time and with disease progression, we plan to conduct follow-up studies to analyze its longitudinal trajectories. Furthermore, the present study did not classify the severity of anxiety disorders among the participants, thus precluding intergroup comparisons across different levels of anxiety disorder severity. The second part of the research was unable to establish causal relationships between anxiety-related stigma and the studied variables. Additionally, further work is needed to determine the cutoff values and the receiver operating characteristics (ROC)48 for the scale used in this study.

Conclusions

This study provides initial evidence for the adequate reliability and validity of the scores produced by the Chinese version of the SASS within the Chinese population. Preliminary application of the scale in clinical settings further supports its utility as a reliable assessment tool for evaluating stigma associated with anxiety disorders. Furthermore, multivariate analysis revealed that a family history of psychiatric disorders, diminished objective social support, and elevated subjective social support emerged as significant predictors influencing the severity of stigma experienced by patients with anxiety disorders.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tyrer, P. & Baldwin, D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet 368, 2156–2166. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69865-6 (2006).

Huang, Y. et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in china: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 6, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X (2019).

Xu, Z., Rusch, N., Huang, F. & Kosters, M. Challenging mental health related stigma in china: systematic review and meta-analysis. I. Interventions among the general public. Psychiatry Res. 255, 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.008 (2017).

Zhu, J., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z. & Hu, B. Public attitudes toward anxiety disorder on Sina weibo: content analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e45777. https://doi.org/10.2196/45777 (2023).

Schofield, C. A. & Ponzini, G. T. The Skidmore anxiety stigma scale (SASS): A Covert and brief self-report measure. J. Anxiety Disord. 74, 102259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102259 (2020).

Ociskova, M. et al. Self-stigma and treatment effectiveness in patients with anxiety disorders - a mediation analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 14, 383–392. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S152208 (2018).

Hogg, B. et al. Supporting employees with mental illness and reducing mental illness-related stigma in the workplace: an expert survey. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 273, 739–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01443-3 (2023).

Calear, A. L., Batterham, P. J., Torok, M. & McCallum, S. Help-seeking attitudes and intentions for generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents: the role of anxiety literacy and stigma. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 30, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01512-9 (2021).

Vally, Z., Cody, B. L., Albloshi, M. A. & Alsheraifi, S. N. M. Public stigma and attitudes toward psychological help-seeking in the united Arab emirates: the mediational role of self-stigma. Perspect. Psychiatr Care. 54, 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12282 (2018).

Xu, Z., Huang, F., Kosters, M. & Rusch, N. Challenging mental health related stigma in china: systematic review and meta-analysis. II. Interventions among people with mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 255, 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.002 (2017).

Corrigan, P. W. & Shapiro, J. R. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.004 (2010).

Lu, S., Oldenburg, B., Li, W., He, Y. & Reavley, N. Population-based surveys and interventions for mental health literacy in China during 1997–2018: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry. 19, 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2307-0 (2019).

Sensky, T. Giovanni fava’s contributions to the conceptualization and evidence base of clinimetrics. Psychother. Psychosom. 92, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528027 (2023).

McNeish, D. & Wolf, M. G. Dynamic fit index cutoffs for confirmatory factor analysis models. Psychol. Methods. 28, 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000425 (2023).

Portoghese, I. et al. Stress among university students: factorial structure and measurement invariance of the Italian version of the Effort-Reward imbalance student questionnaire. BMC Psychol. 7, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0343-7 (2019).

Chang, C. C. et al. Rasch analysis suggested three unidimensional domains for affiliate stigma scale: additional psychometric evaluation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.018 (2015).

Ekbladh, E., Yngve, M. & Melin, J. Initial evaluation of measurement properties of the work environment impact questionnaire (WEIQ) - using Rasch analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 22, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-024-02260-z (2024).

Christensen, K. S., Cosci, F., Carrozzino, D. & Sensky, T. Rasch analysis and its relevance to psychosomatic medicine. Psychother. Psychosom. 93, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1159/000535633 (2024).

Hecht, M., Hardt, K., Driver, C. C. & Voelkle, M. C. Bayesian continuous-time Rasch models. Psychol. Methods. 24, 516–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000205 (2019).

Balsis, S., Ruchensky, J. R. & Busch, A. J. Item response theory applications in personality disorder research. Personal Disord. 8, 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000209 (2017).

Cosci, F. Clinimetric perspectives in clinical psychology and psychiatry. Psychother. Psychosom. 90, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517028 (2021).

Moore, S. A. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) in individuals seeking outpatient specialty treatment for anxiety-related disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.041 (2015).

Qiu, L., Xu, H., Li, Y., Zhao, Y. & Yang, Q. Gender differences in attitudes towards psychological help-seeking among Chinese medical students: a comparative analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18826-x (2024).

Zou, Z. et al. Validity and reliability of the physical activity and social support scale among Chinese established adults. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 53, 101793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2023.101793 (2023).

Stolt, M., Kottorp, A. & Suhonen, R. The use and quality of reporting of Rasch analysis in nursing research: A methodological scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 132, 104244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104244 (2022).

Wu, M. H., Chong, K. S., Huey, N. G., Ou, H. T. & Lin, C. Y. Quality of life with pregnancy outcomes: further evaluating item properties for refined taiwan’s fertiqol. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 120, 939–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2020.09.015 (2021).

Savalei, V. Improving fit indices in structural equation modeling with categorical data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 56, 390–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2020.1717922 (2021).

Iramaneerat, C., Yudkowsky, R., Myford, C. M. & Downing, S. M. Quality control of an OSCE using generalizability theory and many-faceted Rasch measurement. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 13, 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9060-8 (2008).

Belzak, W. C. M. Testing differential item functioning in small samples. Multivar. Behav. Res. 55, 722–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1671162 (2020).

Cleanthous, S., Barbic, S. P., Smith, S. & Regnault, A. Psychometric performance of the PROMIS(R) depression item bank: a comparison of the 28- and 51-item versions using Rasch measurement theory. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes. 3, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-019-0131-4 (2019).

Smith, E. V. Jr. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J. Appl. Meas. 3, 205–231 (2002).

Cai, T. et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) among patients with breast cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 21, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02164-4 (2023).

Danielsson, L., Elfstrom, M. L., Galan Henche, J. & Melin, J. Measurement properties of the Swedish clinical outcomes in routine evaluation outcome measures (CORE-OM): Rasch analysis and short version for depressed and anxious out-patients in a multicultural area. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 20, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-01937-7 (2022).

Canto-Cerdan, M., Cacho-Martinez, P., Lara-Lacarcel, F. & Garcia-Munoz, A. Rasch analysis for development and reduction of symptom questionnaire for visual dysfunctions (SQVD). Sci. Rep. 11, 14855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94166-9 (2021).

Huang, T. W., Wu, P. C. & Mok, M. M. C. Examination of Gender-Related differential item functioning through Poly-BW indices. Front. Psychol. 13, 821459. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.821459 (2022).

Melin, J., Bonn, S. E., Pendrill, L. & Trolle Lagerros, Y. A questionnaire for assessing user satisfaction with mobile health apps: development using Rasch measurement theory. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 8, e15909. https://doi.org/10.2196/15909 (2020).

Kim, E. J., Yu, J. H. & Kim, E. Y. Pathways linking mental health literacy to professional help-seeking intentions in Korean college students. J. Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 27, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12593 (2020).

Meier, S. M. & Deckert, J. Genetics of anxiety disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21, 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1002-7 (2019).

Andersen, M. M., Varga, S. & Folker, A. P. On the definition of stigma. J. Eval Clin. Pract. 28, 847–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13684 (2022).

Al-Dwaikat, T. N., Rababa, M. & Alaloul, F. Relationship of stigmatization and social support with depression and anxiety among cognitively intact older adults. Heliyon 8, e10722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10722 (2022).

Oti-Boadi, M., Andoh-Arthur, J., Abekah-Carter, K. & Abukuri, D. N. Internalized stigma: social support, coping, psychological distress, and mental well-being among older adults in Ghana. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 70, 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640241227128 (2024).

Karacar, Y. & Bademli, K. Relationship between perceived social support and self stigma in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 68, 670–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211001886 (2022).

Taylor-Rodgers, E. & Batterham, P. J. Evaluation of an online psychoeducation intervention to promote mental health help seeking attitudes and intentions among young adults: randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 168, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.047 (2014).

Wang, D. F. et al. Social support and depressive symptoms: exploring stigma and self-efficacy in a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry. 22, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03740-6 (2022).

Li, J., Liu, X., Ma, L. & Zhang, W. Users’ intention to continue using social fitness-tracking apps: expectation confirmation theory and social comparison theory perspective. Inf. Health Soc. Care. 44, 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2018.1434179 (2019).

Sattler, S., Zolala, F., Baneshi, M. R., Ghasemi, J. & Amirzadeh Googhari, S. Public stigma toward female and male opium and heroin Users. An experimental test of attribution theory and the familiarity hypothesis. Front. Public. Health. 9, 652876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.652876 (2021).

Diaz-Mandado, O. & Perianez, J. A. An effective psychological intervention in reducing internalized stigma and improving recovery outcomes in people with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 295, 113635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113635 (2021).

Hiller, T. S., Hoffmann, S., Teismann, T., Lukaschek, K. & Gensichen, J. Psychometric evaluation and Rasch analyses of the German overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS-D). Sci. Rep. 13, 6840. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33355-0 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Greatly appreciate every participant who filled out the questionnaire.

Funding

This study was supported by Nantong Municipal Health Commission, Grant Number: QNZ2024010; Science and technology Project of Nantong City, China, Grant Number: MS2023025, MS2023024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YQ. L., XQ.X., and XM.Z. involved in the study’s conception, design investigation, and data analysis. JJ.Z. and Y.S. were involved in the data analysis. YQ.L., JC.Y., Y.S. involved in data collection. YQ. L. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study procedure was granted approval by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (approval number: 2021-K051) and rigorously adhered to the principles of confidentiality, non-maleficence, and informed consent, in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhang, J., Sheng, Y. et al. Rasch analysis and application research of the Chinese version of the Skidmore anxiety stigma scale: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 41412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25301-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25301-z