Abstract

This study aims to develop and validate a machine learning-based mortality risk prediction model for V-A ECMO patients to improve the precision of clinical decision-making. This multicenter retrospective cohort study included 280 patients receiving V-A ECMO from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Yulin First People’s Hospital, and the MIMIC-IV database. The data from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University and the MIMIC-IV database were merged and randomly divided in a 7:3 ratio into a training set and an internal validation set, respectively. The dataset from Yulin First People’s Hospital was reserved as an external validation cohort. The primary study outcome was defined as in-hospital mortality.Feature selection was conducted using Lasso regression, followed by the development of six machine learning models: Logistic Regression, Random Forest (RF), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), LightGBM, and CatBoost. Model performance was assessed using the Area Under the Curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score. Model validation was performed through calibration and decision curve analysis. Feature importance was evaluated using SHAP, and subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the model’s applicability across different clinical scenarios. In internal validation, the Logistic Regression model performed the best, with an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77–0.93), accuracy of 0.76, sensitivity of 0.73, specificity of 0.79, and an F1 score of 0.73. It outperformed other models (RF: AUC = 0.79, DNN: AUC = 0.78, SVM: AUC = 0.76, LightGBM: AUC = 0.71, CatBoost: AUC = 0.77). External validation yielded consistent results, with the Logistic Regression model’s AUC at 0.75 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92), accuracy of 0.69, sensitivity of 0.64, specificity of 0.73, and an F1 score of 0.66. Calibration curve analysis revealed that the Logistic Regression model had the lowest Brier score (0.1496), indicating the most reliable predicted probabilities. Decision curve analysis demonstrated that the model provided the highest net benefit across most decision thresholds. SHAP analysis identified lactate, age, and albumin as key predictors of mortality, with lactate and age positively correlated, and albumin negatively correlated. Subgroup analysis revealed better performance in the cardiac arrest group (AUC = 0.81), non-sepsis group (AUC = 0.75), and non-diabetes group (AUC = 0.78). The Logistic Regression-based mortality risk prediction model for V-A ECMO patients demonstrated comparable or even favorable performance to more complex machine learning models, with the advantage of higher interpretability.By explicitly incorporating lactate, age, and albumin as the principal predictors, this model facilitates precise risk stratification and provides practical support for clinical decision-making in ECMO management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is an advanced life support technology used to treat patients with severe cardiopulmonary failure. It functions by drawing blood from the body, oxygenating it through a membrane lung, and removing carbon dioxide before returning it to the body, temporarily substituting heart and lung function to allow for organ recovery1. Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (V-A ECMO) provides simultaneous support for both the heart and lungs and is widely used in the management of critically ill patients, including those with cardiogenic shock, post-cardiac surgery shock, severe heart failure, and refractory cardiac arrest2,3,4,5.

Despite significant advancements in ECMO technology, its clinical application still faces numerous challenges. These include high medical costs, complex procedural techniques, and potential complications6, as well as the complexities of ECMO configuration choices and anticoagulation management strategies7,8, all of which limit its widespread use. Studies have shown that the overall mortality rate for ECMO patients remains as high as 40%8. However, current clinical practice lacks standardized patient selection criteria and is also deficient in high-quality randomized controlled trials. This gap complicates the identification of patients most likely to benefit from ECMO9,10. Therefore, the development of an efficient and reliable ECMO prognosis prediction model is of significant clinical importance.

ECMO prognosis models are generally classified into two types based on their operational modes: VV-ECMO and V-A ECMO. Among these, V-A ECMO prognosis models are more prevalent in both quantity and clinical application11 likely due to their broader range of indications. However, existing V-A ECMO prognosis models still have considerable potential for improvement in terms of data sources, research methodologies, and external validation. This study aims to integrate multi-center clinical data and apply machine learning techniques to develop and validate an efficient in-hospital mortality risk prediction model for V-A ECMO patients, offering more precise support for clinical ECMO decision-making.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This study employed a retrospective cohort design to develop and validate an in-hospital mortality risk prediction model for V-A ECMO patients using multi-center data. The study data were sourced from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (117 cases, 2018–2024), the MIMIC-IV database (134 cases, 2008–2022), and Yulin First People’s Hospital (29 cases, 2022–2024), ensuring diversity and comprehensiveness in data sources. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Approval No: 2024-KY(1112)) and Yulin First People’s Hospital (Approval No: YLSY-IRB-SR-2024121). All patient data were de-identified to ensure privacy and security. Prior to accessing the MIMIC-IV database, the research team completed the “Protecting Human Research Participants” training and received certification (Record ID: 68089798), with no additional informed consent required.All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal surrogates before inclusion in the study.

Study subjects

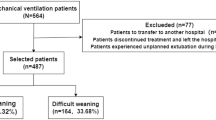

This study focused on patients aged ≥ 18 years who received V-A ECMO treatment for the first time and had complete data records. To ensure scientific rigor and data reliability, exclusion criteria included: age < 18 years, use of mixed ECMO or transition between ECMO modes, missing more than 50% of key variables, non-first-time ECMO, and ECMO used as a bridge for surgery or organ transplantation. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1) were applied to ensure homogeneity among the study population, providing high-quality baseline data for subsequent analysis.

Data collection and processing

Based on previous studies12 and clinical experience, this study collected multidimensional variables that may influence mortality risk in V-A ECMO patients, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, body mass index), comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, chronic heart failure), pre-ECMO treatments (e.g., mechanical ventilation duration, vasopressor use), laboratory indicators. Laboratory parameters such as lactate, albumin, and prothrombin time were collected as the worst values within 6 h prior to ECMO initiation; for patients undergoing ECPR, the first available blood sample after cannulation was used. Organ function scores (e.g., Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Glasgow Coma Scale). Data preprocessing followed a systematic process, including outlier detection and treatment (using the interquartile range method), missing data imputation (variables with > 30% missing data were excluded, while variables with < 30% missing data were imputed using multiple imputation), Z-score normalization for continuous variables, and one-hot encoding for categorical variables. The datasets from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University and MIMIC-IV were split into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets for model training and internal validation. Data from Yulin First People’s Hospital served as an external validation set to assess the model’s generalizability. Additionally, to address class imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to the training set to enhance the model’s ability to recognize minority classes.

Variable selection

For variable selection, this study employed Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (Lasso) regression combined with bootstrap resampling. Continuous variables were first Z-score normalized, and then 5-fold cross-validation was used to determine the optimal regularization parameter λ (search range: 10⁻⁴ to 10²), with Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the optimization metric. The curve of MSE versus λ was plotted to select the λ value that minimized MSE. Lasso regression was then applied, and variables with non-zero regression coefficients were selected. To validate the robustness of the selected variables, 1000 bootstrap resamplings were performed. The frequency of each variable being selected was calculated, with a selection threshold set at 50% (i.e., a variable was considered selected if it appeared in more than 500 of the 1000 resamplings).

Model construction and evaluation

Based on the selected key variables, this study constructed six machine learning models: Logistic Regression (LR), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost). All models were optimized using 10-fold cross-validation on the training set, along with grid search, regularization, and early stopping strategies to prevent overfitting. Model performance was evaluated using multiple metrics, including Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score, with both internal and external validation. Additionally, calibration curves were used to assess the consistency between predicted probabilities and actual incidence rates. Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) was employed to evaluate the net benefit of the model at different decision thresholds, providing scientific evidence to support clinical decision-making. Detailed hyperparameter tuning protocols, cross-validation strategies, and final best parameters for each model are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Subgroup analysis and model interpretability

To comprehensively assess the model’s applicability across different patient groups, this study performed subgroup analyses based on clinical characteristics, including: sepsis vs. non-sepsis, cardiac arrest vs. non-cardiac arrest, diabetes vs. non-diabetes, high lactate (> 9 mmol/L) vs. low lactate (≤ 9 mmol/L), elderly (> 60 years) vs. young (≤ 60 years), and short-term mechanical ventilation (≤ 30 h) vs. long-term mechanical ventilation (> 30 h). Lactate, age, and pre-ECMO mechanical ventilation duration were grouped based on the mean values of these variables in the reference sample data. For each subgroup, AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score were calculated to evaluate the model’s classification performance, ensuring its stability and reliability across different clinical contexts.

In terms of model interpretability, this study applied Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) to interpret the predictions of the optimal model. Global analysis was conducted by calculating SHAP feature importance and generating SHAP summary plots, which revealed the contribution and direction of each feature to the prediction results. Local case analysis involved randomly selecting patients, calculating individual SHAP values, and creating SHAP waterfall plots to visualize the impact of features on individual patient survival predictions. By combining the log-odds prediction value f(x), individual mortality probabilities were calculated using the formula: \(\:\text{P}\left(\text{d}\text{e}\text{a}\text{t}\text{h}\right)=\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-\text{f}\left(\text{x}\right)}}\), providing personalized prediction explanations to support precise clinical decision-making.

This study conducted statistical analysis and machine learning model construction in a Python 3.12 environment. For the comparison of continuous variables between groups, t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were applied, depending on normality and variance homogeneity. For categorical variables, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used. Machine learning models were built using the scikit-learn, tensorflow.keras, catboost, and lightgbm libraries. Scikit-learn was used for feature standardization, cross-validation, and model evaluation; tensorflow.keras was employed for deep neural network training; and catboost and lightgbm were utilized to build the respective models.

For model evaluation, calibration curve analysis was used to assess the accuracy of predicted probabilities, and decision curve analysis was performed to evaluate clinical benefit. A two-tailed p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline data and dataset characteristics

A total of 280 patients who received V-A ECMO treatment were included in this study, recruited from three centers. The MIMIC-IV database contributed 134 patients with a crude in-hospital mortality of 49.7%, with approximate distributions of acute myocardial infarction (29.9%), cardiac arrest (14.9%), myocarditis (3.0%), sepsis (13.4%), and other causes (38.8%). The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University included 117 patients with a crude mortality of 34.1%, with distributions of acute myocardial infarction (27.4%), cardiac arrest (13.7%), myocarditis (2.6%), sepsis (12.8%), and other causes (43.6%). Yulin First People’s Hospital contributed 29 patients with a crude mortality of 48.2%, with approximate distributions of acute myocardial infarction (30%), cardiac arrest (15%), myocarditis (5%), sepsis (15%), and other causes (35%). These distributions support the generalizability of the dataset for V-A ECMO patients across diverse clinical settings.

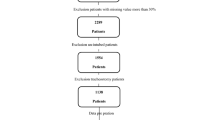

Initially, 63 clinical variables were considered, covering demographics, vital signs, laboratory parameters, treatment measures, and a wide range of comorbidities, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis, immunosuppressive status, malignancy, organ transplantation, and neurological dysfunction, in addition to diabetes and chronic heart failure. Due to a missing data rate exceeding 30%, 13 variables were excluded, including neurological dysfunction, liver cirrhosis, corticosteroid use, HIV/AIDS, malignancy, organ transplantation, prone positioning, lung recruitment, IABP use, bicarbonate infusion, history of cardiac surgery, history of cardiac intervention, and central venous pressure, leaving 50 variables for subsequent analysis.

The baseline data for the training and testing sets (Table 1) showed that the test set had a lower white blood cell count (p = 0.0047). No significant differences were observed between the two groups for the other variables (p > 0.05). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the mortality rate distribution between the training and testing sets (p = 0.8551), indicating similar clinical outcomes between the two groups. Although there were differences in certain variables in the test set, the overall data distribution was balanced, ensuring the scientific validity and reliability of subsequent analyses.

Feature selection

Prior to machine learning model construction, the optimal regularization parameter was determined as λ = 0.037 based on the Mean Squared Error (MSE) curve of the Lasso regression model (Fig. 2A). At this λ value, nine key features were selected from the original 50 variables: age, body mass index (BMI), bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻), lactate (Lac), mean arterial pressure (MAP), albumin (Alb), prothrombin time (PT), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) (Fig. 2B).

Lasso regularization path and optimal lambda selection for regression coefficients. (A) Shows how the mean squared error (MSE) of the Lasso regression model changes with different values of the regularization parameter λ. The x-axis represents λ on a logarithmic scale, and the y-axis shows the MSE. The error bars indicate the MSE range from cross-validation. As λ increases, MSE decreases and stabilizes, but if λ becomes too large, the model underfits and MSE increases again. The dashed vertical line shows the optimal λ, selected through cross-validation. (B) Illustrates how the regression coefficients for various features change with increasing λ. The x-axis represents λ, and the y-axis represents the regression coefficients. Colored curves represent key features (e.g., age, BMI, HCO3-, Lac, MAP, Alb, PT, GCS, and SAPSII), while gray curves show other variables. As λ increases, the coefficients of less important variables shrink towards zero. The dashed vertical line indicates the optimal λ, selected by cross-validation.

Model development and performance evaluation

Based on the nine variables selected through Lasso regression, six machine learning models were developed: Random Forest (RF), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), CatBoost, and Logistic Regression. In internal validation (Table 2), the Logistic Regression model demonstrated the best overall performance, with an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77–0.93), accuracy of 0.76, sensitivity of 0.73, specificity of 0.79, and an F1 score of 0.73. The RF model achieved the highest sensitivity (0.76), but its specificity was relatively low (0.55). In contrast, the SVM model showed the highest specificity (0.88) but the lowest sensitivity (0.45). Both the DNN and CatBoost models performed well in terms of AUC and accuracy, although slightly inferior to Logistic Regression. LightGBM exhibited the weakest predictive performance, with an AUC of only 0.71.

In external validation (Table 3), Logistic Regression again outperformed the other models, with an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92), accuracy of 0.69, sensitivity of 0.64, specificity of 0.73, and an F1 score of 0.66. The SVM and DNN models exhibited relatively stable performance, each achieving an AUC of 0.73. In contrast, RF and LightGBM had lower AUCs of 0.66 and 0.65, respectively.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis further confirmed the classification performance of each model (Fig. 3). In this study, ROC curves were plotted for three datasets: the training set (Fig. 3A), the internal validation set (Fig. 3B), and the external validation set (Fig. 3C). The Logistic Regression model demonstrated superior discriminatory ability in both the test and external validation sets, with AUCs of 0.83 and 0.75, respectively, outperforming all other models. The difference from the AUC of 0.86 in Table 2 is due to cross-validation results versus the independent test set. Calibration curves (Fig. 4A) showed that the Logistic Regression model had the lowest Brier score (0.1496), indicating the highest reliability in probability estimation. Decision Curve Analysis (Fig. 4B) revealed that the Logistic Regression model offered the greatest net benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities, further supporting its clinical utility. Furthermore, to enhance the practical applicability of the model in bedside decision-making, we conducted an additional analysis to determine the optimal classification cutoff probability based on the Youden index, as well as to stratify patients into clinically meaningful risk categories.The optimal classification threshold determined by the Youden index was 1.000, which achieved a sensitivity of 0.900 and a specificity of 0.321. As the predicted probabilities were strongly shifted toward the positive class, no patients were classified in the intermediate-risk group (30–60%). Among the high-risk group (> 60%), 48% of patients died (120/249) and 52% survived (129/249), while only two patients were categorized as low risk (< 30%) and both survived. These findings suggest that the logistic regression model tended to overestimate mortality probabilities, which may require recalibration in future applications.

ROC Curves for different machine learning models. (A) ROC curves for different machine learning models on the training dataset, with the x-axis representing the False Positive Rate (FPR) and the y-axis representing the True Positive Rate (TPR). Random Forest (AUC = 0.97) and CatBoost (AUC = 0.97) show the best performance, with Logistic Regression having the lowest AUC (0.79). (B) ROC curves for different machine learning models on the test dataset. Logistic Regression (AUC = 0.83) performs best, followed by Random Forest (AUC = 0.79) and DNN (AUC = 0.80). The models generally show good performance on the test data. (C) ROC curves for different machine learning models on the external validation dataset. DNN (AUC = 0.73) and SVM (AUC = 0.73) show the best performance, while Random Forest (AUC = 0.66) performs the worst. Overall, models tend to perform worse on the external validation data compared to the training and test datasets.

Calibration and DCA for machine learning models. (A) Calibration curves for different models, showing the relationship between predicted probabilities (x-axis) and actual positive rates (y-axis). The dashed line represents perfect calibration. The Brier score (in parentheses) indicates calibration performance, with lower values indicating better calibration. Logistic Regression has the lowest Brier score (0.1496), indicating the best calibration. (B) DCA for different models. The x-axis represents the decision threshold probability, and the y-axis shows net benefit. “Treat All” (red line) and “Treat None” (black line) are the reference strategies. Logistic Regression, SVM, and DNN show the highest net benefits, indicating superior clinical utility across various thresholds. *DCA: Decision curve analysis.

Subgroup analysis of the logistic regression model

Table 4 summarizes the performance metrics of the Logistic Regression model across various subgroups, including AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s predictive capability. The results suggest that the model maintains good predictive accuracy in patient subgroups with well-defined pathophysiological profiles, but its performance decreases in other subgroups, which may be influenced by unaccounted confounding factors, treatment heterogeneity, or sample size limitations.The model demonstrated strong performance in the non-sepsis group (AUC = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.70–0.80) and the non-diabetic group (AUC = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.71–0.83). However, its performance declined in the sepsis group (AUC = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.23–0.87) and the diabetic group (AUC = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.39–0.84). The highest AUC was observed in the cardiac arrest group (AUC = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.63–1.00), with an accuracy of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.58–0.99), indicating robust predictive ability in this population.

Notably, the model also performed well in the high lactate subgroup (lactate > 9 mmol/L), achieving an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.53–0.89) and a sensitivity of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.56–0.99). In the elderly subgroup (age > 60 years), the model achieved an AUC of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.86) and an accuracy of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.66–0.80), reflecting good predictive performance. Conversely, in the younger subgroup (age ≤ 60 years), the model’s AUC was lower (0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.74), with a sensitivity of only 0.46 (95% CI: 0.31–0.61), indicating reduced predictive accuracy in this group.

SHAP analysis of the logistic regression model

Global SHAP Analysis The SHAP feature importance analysis (Fig. 5A) identified lactate, age, and albumin as the most influential predictors of mortality risk in V-A ECMO patients. Lactate demonstrated the highest mean SHAP values across the training, test, and external validation sets (0.545, 0.518, and 0.573, respectively), followed by age (0.412, 0.411, and 0.421) and albumin (0.368, 0.362, and 0.390). SHAP summary plots (Fig. 5B) further illustrated the direction and magnitude of each feature’s effect on model predictions. Elevated lactate levels were associated with higher SHAP values and an increased risk of mortality. Similarly, older age contributed positively to the predicted risk, indicating higher mortality among elderly patients. In contrast, albumin showed a negative correlation with SHAP values, suggesting that higher albumin levels were protective and associated with improved survival outcomes.

SHAP analysis for feature importance and model predictions. (A) This panel shows the feature importance analysis for the model across three datasets: the training set, test set, and external validation set. The x-axis represents the average SHAP values, indicating the contribution of each feature to the model’s prediction. The higher the SHAP value, the greater the influence of that feature on the model. The features are ranked by their importance, with Lac and age consistently appearing as top contributors across all sets. (B) This panel displays SHAP summary plots for the three datasets. Each dot represents a single sample, with the x-axis showing the SHAP value that indicates how much each feature contributes to the model’s prediction. The color of the dots represents the feature value: red indicates higher values, and blue indicates lower values. The plot shows how the influence of features like Lac and age changes across the prediction range, with higher values of Lac and age generally leading to more positive model predictions. (C) This panel provides a SHAP case analysis for an individual sample from the training set. The x-axis shows the cumulative SHAP contributions, with each feature’s contribution to the final prediction represented by bars. Red bars indicate features contributing positively to the prediction, while blue bars indicate negative contributions. The baseline prediction (E[f(X)]) represents the average prediction for the dataset, and the sum of the SHAP values from all features determines the model’s final prediction for this specific sample. (D) This panel shows the SHAP case analysis for a sample from the test set, similar to (C) but on a different dataset. The cumulative SHAP values for each feature are displayed, with red bars for positive contributions and blue bars for negative contributions. The final prediction is calculated by summing the individual SHAP values, with the baseline prediction (E[f(X)]) representing the average across all samples in the test set. (E) This panel displays the SHAP case analysis for a sample from the external validation set. The methodology is the same as in the previous panels, where the SHAP values for each feature are accumulated to generate the model’s final prediction. The baseline prediction (E[f(X)]) serves as the reference, with the sum of individual SHAP values determining how much each feature contributes to the final outcome.

Local SHAP Case Analysis One patient was randomly selected from each of the training, test, and external validation sets for individualized SHAP analysis using waterfall plots (Fig. 5C–E). In the training set, the selected patient had a predicted log-odds of 1.155, corresponding to a mortality probability of 76.1%. The primary contributing features were lactate (+ 0.40), albumin (+ 0.28), age (+ 0.28), and bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻, + 0.27). In the test set, another patient had a predicted log-odds of 2.432, equating to a 91.9% probability of death. The most influential predictors were lactate (+ 0.69), age (+ 0.62), mean arterial pressure (MAP, + 0.50), and SAPS II (+ 0.45). In the external validation set, the selected patient had a log-odds prediction of − 1.846, corresponding to a mortality probability of 13.6%. Key protective factors included albumin (− 0.68), age (− 0.41), and lactate (− 0.25).

Discussion

This study systematically compared the performance of Logistic Regression with that of RF, CatBoost, LightGBM, SVM, and DNN in predicting the prognosis of patients undergoing V-A ECMO. The results demonstrated that Logistic Regression achieved the best predictive performance in the external validation cohort, with an AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92) and the lowest Brier score (0.1496), significantly outperforming the other models (RF: 0.1957; CatBoost: 0.2426; LightGBM: 0.2574).

Decision Curve Analysis further confirmed that Logistic Regression provided the highest net clinical benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities, highlighting its practical value in supporting clinical decision-making. These findings underscore the importance of model interpretability and stability when evaluating V-A ECMO candidacy.

The results of this study are consistent with previous research. Lee et al. reported an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.80–0.93) for a Logistic Regression model developed using data from 112 V-A ECMO patients13. Similarly, the ENCOURAGE score—a prognostic model for patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock treated with V-A ECMO—achieved an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.77–0.91) in a cohort of 138 patients14, further supporting the clinical utility of Logistic Regression models in this setting. In addition, the (survival after veno-arterial ECMO, SAVE) score, a well-established logistic regression-based tool for V-A ECMO outcome prediction, was developed on a larger international cohort of 3,846 patients and achieved an AUC of 0.9015. It is exclusively based on pre-ECMO variables—such as etiology of cardiogenic shock, lowest bicarbonate within 6 h before cannulation, and duration of intubation—making it both parsimonious and clinically practical. By comparison, our study explored a different methodological perspective. Although our model included composite severity indices such as GCS and SAPS II in addition to basic laboratory markers (lactate, age, albumin), which may appear more complex than SAVE, our main innovation lies in integrating SHAP analysis to provide individualized interpretability. Rather than aiming to replace the SAVE score, our model seeks to complement existing tools by highlighting physiologically relevant predictors and offering transparent insights into how these variables contribute to risk stratification. This approach may facilitate more personalized decision-making in the early assessment of V-A ECMO candidates.

This consistently favorable and interpretable performance underscores several key advantages of the Logistic Regression model. First, as a type of generalized linear model, Logistic Regression has a well-established mathematical foundation and provides transparent interpretation of variable weights, thereby enhancing the credibility and acceptance of clinical decision-making16. Second, SHAP analysis improved model interpretability by elucidating the contributions of key predictors—such as lactate, age, and albumin—to mortality risk, offering a scientific basis for individualized treatment strategies.

Third, under conditions of limited sample size (training set n = 175), Logistic Regression effectively mitigated the risk of overfitting, demonstrating strong stability and generalizability. In contrast, although more complex machine learning models such as RF (AUC = 0.97) and CatBoost (AUC = 0.96) achieved excellent performance in the training set, their predictive power declined markedly in the external validation set (dropping to 0.66–0.73). Moreover, their “black-box” nature limits interpretability, which may reduce clinician trust and introduce potential risks in critical decision-making17. It should be noted that to ensure a fair comparison, all competing models (RF, CatBoost, LightGBM, SVM, DNN) underwent model-specific hyperparameter tuning with 10-fold cross-validation. Despite these optimization efforts, Logistic Regression remained the most stable and generalizable model across both internal and external validation.

Building on this foundation, Lasso regression was applied to enhance the model’s predictive efficiency by systematically identifying key prognostic factors, including lactate, age, and albumin. The study further examined the distinct clinical relevance of these variables in outcome prediction.

First, lactate has been widely validated as an independent predictor of mortality. Laimoud et al.18 reported that patients in the non-survivor group had significantly higher lactate levels than survivors (7.2 ± 2 mmol/L vs. 4.4 ± 1.5 mmol/L, P < 0.001). Our findings further support that elevated lactate levels prior to V-A ECMO initiation serve as an early warning marker for mortality risk, providing timely and reliable guidance for clinical decision-making. Second, age emerged as a pivotal predictor in our model and has consistently been associated with mortality risk in prior studies. A multicenter study in Korea found that each additional year of age increased the risk of death by 4.4% (OR = 1.044, AUC = 0.67), and patients aged over 65 had significantly lower survival rates compared to the overall cohort (31.4% vs. 45.9%)19.

However, it is important to note that the definition of “advanced age” varies across prognostic tools. For instance, the SAVE score15 identifies patients aged 38 years or younger as having a favorable prognosis, whereas the ENCOURAGE score14 classifies patients over 60 years as high-risk. These discrepancies underscore the importance of comprehensive, individualized assessment in clinical practice.

Finally, serum albumin levels were significantly and inversely associated with in-hospital mortality, a relationship well supported by evidence from multicenter studies20,21. For example, Raja et al.21 found that patients with albumin levels ≤ 3 g/dL had a significantly higher mortality rate than those with levels > 3 g/dL (44.9% vs. 27.5%, P = 0.002), and each 1 g/dL increase in albumin was associated with a 32% reduction in mortality risk (OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.48–0.96, P = 0.03). Our study further validates the critical role of albumin in risk stratification for V-A ECMO patients.

Notably, the findings of this study suggest that in the assessment of V-A ECMO candidacy, model interpretability is as crucial as predictive performance. Due to its simplicity and transparency, Logistic Regression functions not only as a robust tool for population-level risk stratification but also as a practical foundation for personalized clinical decision support. These insights underscore the importance of balancing model complexity with data availability when selecting predictive tools in clinical settings. Greater emphasis should be placed on the model’s practical utility, offering a valuable methodological framework for optimizing the management of V-A ECMO patients.

Further analysis revealed that the Logistic Regression model demonstrated favorable predictive performance across various clinical subgroups, although some degree of heterogeneity was observed. The model performed best in the cardiac arrest subgroup (AUC = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.63–1.00) and showed good performance in the non-sepsis and non-diabetic groups (AUC = 0.75 and 0.78, respectively). Although the model showed lower AUC values in the sepsis (0.57) and diabetic (0.66) subgroups, these results should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and the potential heterogeneity of these patient populations. Additionally, the model performed better in the short-term mechanical ventilation group (≤ 30 h, AUC = 0.74) compared to the long-term ventilation group (> 30 h, AUC = 0.65), suggesting that prognosis prediction is more challenging in patients with more complex clinical conditions.

Although these variables demonstrated predictive relevance in subgroup analyses, they did not reach statistical significance in the Lasso regression and were therefore not included in the final feature set. This finding differs from previous studies12,22, which may be explained by differences in study design or population characteristics. Moreover, prior single-center studies have reported an overall survival rate of up to 60% among sepsis patients treated with V-A ECMO23,24, suggesting that sepsis may not be a major risk factor for poor outcomes in this population—an observation that further supports the conclusions of the present study.

Among the core predictive variables, lactate demonstrated significant prognostic value. In the high lactate subgroup (≥ 9.0 mmol/L), the model achieved a sensitivity of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.56–0.99), consistent with the findings reported by Kim et al.25. Age also emerged as a key predictor. The elderly subgroup (≥ 60 years) showed an AUC of 0.79, notably higher than that of the younger subgroup (< 60 years, AUC = 0.67), which aligns with results from previous studies13,18,26. These findings reinforce the practical utility of the Logistic Regression model across diverse clinical scenarios and underscore the influence of disease complexity on predictive performance. Collectively, the results provide further evidence supporting more accurate and individualized outcome prediction in V-A ECMO patients.

Based on these findings, this study further underscores the importance of individual patient characteristics in the assessment of ECMO indications. Although certain variables were not included in the final model, their impact within specific subgroups remains clinically meaningful. From a methodological standpoint, this study implemented systematic optimizations in data sourcing, model validation, variable selection, and clinical applicability, resulting in several innovative outcomes.

By integrating multicenter data from the MIMIC-IV database, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, and Yulin First People’s Hospital, the model’s generalizability was significantly enhanced—overcoming the limitations of small sample size and limited representativeness associated with single-center studies12. External validation showed that the Logistic Regression model achieved an AUC of 0.75. Decision Curve Analysis further demonstrated a consistently high net clinical benefit across a broad range of threshold probabilities, confirming the model’s practical utility. Moreover, this study innovatively incorporated pre-ECMO variables into the predictive model and demonstrated that elevated lactate levels prior to ECMO initiation were significantly associated with increased mortality risk. This provides new evidence to support early decision-making regarding V-A ECMO initiation. While most previous studies have focused on variables collected during ECMO support—such as lactate levels and lactate clearance20—limited attention has been given to pre-initiation indicators. Although intra-ECMO variables are useful for monitoring patient status, their clinical value in guiding initiation decisions is inherently limited.

Subgroup analyses further revealed that the Logistic Regression model performed better in patients with cardiac arrest and in those without diabetes or sepsis, suggesting that underlying disease conditions may influence prognostic patterns. These findings highlight the need for future research into individualized risk assessment.

Taken together, these systematic enhancements and innovative insights not only improved the model’s predictive performance but also provided a robust scientific foundation for clinical implementation—offering meaningful implications for real-world decision-making.

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the relatively limited sample size may affect the model’s generalizability to larger or more heterogeneous populations, and therefore the external validation should be regarded as exploratory, with conclusions interpreted with caution. Second, Logistic Regression inherently lacks the ability to capture complex non-linear relationships. Third, as the data were collected from three institutions in different regions, variations in patient characteristics and clinical practices may have introduced bias. Additionally, inconsistencies in variable definitions, coding standards, and data quality control measures may have impacted the model’s overall reliability. Fourth, although the logistic regression model showed acceptable discrimination based on the AUC, the extreme threshold value of 1.000 and the concentration of predicted probabilities indicate a potential overestimation of mortality risk.Finally, we were unable to perform a direct comparison with the SAVE score due to incomplete data for some of its variables, and our model included composite indices (e.g., GCS, SAPS II), which may reduce simplicity compared with SAVE. Moreover, the model failed to clearly identify a low-risk subgroup, limiting its immediate clinical applicability.

Future research should aim to enhance model development through larger-scale, multicenter, and multisource datasets. Expanding the sample size and incorporating international multicenter data would further improve the model’s external validity. Developing hybrid models that integrate Logistic Regression with non-linear algorithms may also enhance predictive accuracy. Moreover, future research should consider recalibrating the model to improve probability scaling and better support clinical risk stratification. Integration of the model into real-time clinical decision support systems is encouraged to maximize its practical utility. Additionally, incorporating multidimensional data—such as genomics and medical imaging—may further refine risk stratification and strengthen the model’s predictive capabilities, ultimately advancing the goals of precision medicine.

Conclusion

The Logistic Regression-based model for predicting mortality risk in V-A ECMO patients achieved comparable and robust performance to more complex machine learning models, while retaining superior interpretability to support precise clinical decision-making. By incorporating lactate, age, and albumin as the core predictors, the model enables accurate risk stratification and offers meaningful, practical support for clinical decision-making in the management of V-A ECMO patients.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Richardson, A. S. C. et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Adults. Interim guideline consensus statement from the extracorporeal life support organization. Asaio J. 67(3), 221–228 (2021).

Choudhury, T. A. et al. Left heart decompression on veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in children with dilated cardiomyopathy and myocarditis: an extracorporeal life support organization registry review. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 22(12), 1026–1032 (2021).

Kowalewski, M. et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy shock-analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Crit. Care Med. 49(7), 1107–1117 (2021).

Hong, J. A. et al. Comparison of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation configurations for patients listed for heart transplantation. Korean Circ. J. 53(8), 535–547 (2023).

Taccone, F. S. et al. Impact of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation on neurological prognosis and survival in adult patients after cardiac arrest: an individual pooled patient data meta-analysis. Resuscitation 202, 110357 (2024).

Peek, G. J. et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374 (9698), 1351–1363 (2009).

Biancari, F. et al. Central versus peripheral postcardiotomy veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 24 (2022).

Levy, J. H., Staudinger, T. & Steiner, M. E. How to manage anticoagulation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 48 (8), 1076–1079 (2022).

Mehta, A. et al. Contemporary approach to cardiogenic shock care: a state-of-the-art review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1354158 (2024).

Lorusso, R. et al. 2020 EACTS/ELSO/STS/AATS expert consensus on post-cardiotomy extracorporeal life support in adult patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 111(1), 327–369 (2021).

Pladet, L. C. A. et al. Prognostic models for mortality risk in patients requiring ECMO. Intensive Care Med. 49 (2), 131–141 (2023).

Giordano, L. et al. Predictive models in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 12 (1), 44 (2023).

Siao, F. Y. et al. Can we predict patient outcome before extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiac arrest? Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 28 (1), 58 (2020).

Muller, G. et al. The ENCOURAGE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after VA-ECMO for acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. Intensive Care Med. 42 (3), 370–378 (2016).

Schmidt, M. et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur. Heart J. 36 (33), 2246–2256 (2015).

Zabor, E. C., Reddy, C. A., Tendulkar, R. D. & Patil, S. Logistic regression in clinical studies. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 112 (2), 271–277 (2022).

Anjara, S. G. et al. Examining explainable clinical decision support systems with think aloud protocols. PLoS One. 18 (9), e0291443 (2023).

Laimoud, M. & Alanazi, M. The clinical significance of blood lactate levels in evaluation of adult patients with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Egypt. Heart J. 72 (1), 74 (2020).

Baek, M. S. et al. Age is major factor for predicting survival in patients with acute respiratory failure on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a Korean multicenter study. J. Thorac. Dis. 10 (3), 1406–1417 (2018).

Jeon, J. B. et al. Hypoalbuminemia and albumin replacement during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with cardiogenic shock. J. Chest Surg. 56 (4), 244–251 (2023).

Raja, K. M. et al. Hypoalbuminemia is a predictor of mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock requiring veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 40 (5), 1193–1201 (2025).

Jeong, J. H. et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality after successful weaning of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 17529 (2023).

Riera, J., Argudo, E., Ruiz-Rodríguez, J. C. & Ferrer, R. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adults with refractory septic shock. Asaio j. 65 (8), 760–768 (2019).

Vogel, D. J. et al. Veno-arterio-venous ECMO for septic cardiomyopathy: a single-centre experience. Perfusion 33 (1_suppl), 57–64 (2018).

Kim, E. et al. Prediction of 6-month mortality using pre-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation lactate in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing veno-arterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Chest Surg. 55(2), 143–150 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Predicting mortality in patients undergoing VA-ECMO after coronary artery bypass grafting: the REMEMBER score. Crit. Care. 23 (1), 11 (2019).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2021YFC2701700 and 2021YFC2701703), the Key Research & Development Program of Guangxi (Grant No. GuiKeAB22080088),Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST(2022QNRC001), Beijing Nova Program(20220484053),National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82360372), the Joint Project on Regional High-Incidence Diseases Research of Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023GXNSFDA026023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JYL and SLL designed the study and supervised the overall research process. HMG and XLH was responsible for data analysis, model development, and drafting the initial manuscript. KHZ, YC, YCL and CLM contributed to data collection and preprocessing, and assisted in reviewing and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Huang, X., Zhou, K. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning model for predicting mortality risk in veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients. Sci Rep 15, 41581 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25423-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25423-4