Abstract

The compound occurrence of extreme heat and the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased mortality risk beyond the impact of each factor alone. However, the interaction between these two risk factors and their combined effect on mortality has not been adequately quantified. We conducted a time-stratified case-crossover analysis of daily all-cause mortality, minimum temperature, and COVID-19 case counts in Flanders over the period 2018–2021. We applied a distributed lag nonlinear model (DLNM) with a conditional quasi-Poisson regression to estimate the cumulative effects (lag 0–14 days) of extreme heat. The relative risk (RR) was quantified at the 99th percentile (P99) of minimum temperature compared to 50th percentile (P50). To assess effect modification, we used a binary interaction approach (pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19) and a linear interaction approach. We used a 15-day moving average of daily confirmed cases and centered it at three reference points representing 25th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the distribution, corresponding to low, mild and high intensity levels, respectively. We observed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of mortality associated with extreme heat was significantly elevated (RR = 1.55; 95% CI: 1.18–2.02), compared to a weaker and non-significant association during pre-COVID-19 (RR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.72–1.58). The heat-mortality curve showed a sharper increase during the pandemic, specifically above the 14 °C (P50). An increased association was observed together with rising COVID-19 incidence. On days when COVID-19 intensity was low, the relative risk (RR) of heat-related mortality was 1.18 (95% CI: 0.64–2.18). This risk increased under moderate incidence, with an RR of 1.95 (95% CI: 1.1.03–3.70), and rose markedly during high cases, reaching an RR of 3.57 (95% CI: 1.10-11.61). Our findings suggest an increased risk of heat-related mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially as COVID-19 transmission intensified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, the global burden of disease associated with climate change has increasingly drawn attention, and in particular extreme heat events. Approximately five million deaths globally can be attributable to temperature every year, which account for almost 10% of all deaths1. As a result of climate change, extreme heat-related events become more frequent and intense, leading to population-level health risks in Europe2. The 2024 Lancet Countdown report revealed that in Belgium, during 2014–2023, people experienced a 109% increase in heatwave days compared to 1986–2005, where the heatwave in Belgium is defined as periods when the maximum daily temperature reaches at least 25 °C for five consecutive days, with at least three of those days exceeding 30 °C. It also reported that the heat-related mortality rate in Belgium increased by 11 deaths per 100,000 population between 2013 and 20223. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 introduced new complexities to public health systems, overlapping with ongoing heat-related health risks. The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been linked to substantial excess mortality and behavioral changes, including lockdowns and social distancing measures. Similarly, heat increases the risk of cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes, particularly among older adults and individuals with pre-existing health conditions4. People with respiratory diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), may also experience symptom exacerbation during extreme heat, leading to more severe health outcomes5. However, the extent to which the coexistence of heat and COVID-19 has modified the heat–mortality relationship remains poorly understood.

Heat–pathogen interactions likely influence COVID-19 mortality, as vulnerable populations overlap: the elderly, chronically ill, and those requiring care. In Europe, France recorded the highest number of deaths, with 166,8116. Despite increasing concern over interactions between extreme heat and infectious disease, few studies have empirically investigated the joint effects of heat and COVID-19 on mortality. Existing literature has primarily focused on conceptual frameworks rather than quantitative analysis7,8.

Such quantification would be particularly relevant for Belgium given its most severe heatwave ever recorded was in August 2020, when COVID-19 emerged. Belgium was hit by two major COVID-19 waves: the first wave went from March to June 2020, in which Belgian health authorities reported attributable 9,712 deaths9,10. In Belgium, the overall crude mortality rate due to COVID-19 was estimated as 281 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, with higher in Wallonia (331 per 100,000 inhabitants) followed by Brussels-capital region (297 per 100,000 inhabitants), and finally Flanders (252 per 100,000 inhabitants)11.

The central hypothesis for this study is that there may have been a non-spurious correlation between heat and COVID-19 pandemic, and that the pandemic may have amplified the mortality burden associated with heat. Several mechanisms support this hypothesis. First, lockdown measures and stay-at-home orders may have increased indoor heat exposure12. Second, reduced social contact and lack of community support during lockdowns may have left individuals socially isolated without assistance or a reminder to take protective actions, such as staying hydrated13,14. Third, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health services were often overwhelmed or repurposed for the outbreaks, reducing capacity for timely warnings and supporting vulnerable individuals. This disruption may have limited public awareness and access to protective measures, thereby reducing the population’s ability to respond to high temperatures15,16. Therefore, we investigated the overlapping impact of heat and COVID-19 on mortality.

Materials and methods

Population and study design

The study was conducted in Flanders, the northern Dutch-speaking region of Belgium, which represents more than half of the country’s population, with approximately 6.8 million residents out of Belgium’s total populations of about 11.8 million17. We used retrospective daily aggregated data of the four summers in the years 2018 to 2021, each from May to September. This period captures the two years before and the two years during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing a comparison of the temperature-mortality association and the effect modification due to the pandemic. We obtained data from Intego, a well-established general practice-based morbidity database managed by the Academic Center for General Practice, KU Leuven. Intego systematically collects clinical and diagnostic data from general practitioners (GPs) using standardized coding systems, providing insights into acute health conditions and temporal trends in primary healthcare use. A detailed description of Intego’s coverage can be consulted in our previous study18. Mortality data within Intego database are obtained through linkage with the national registry for mortality data, which enables the identification of deaths among individuals registered in the Intego database. Laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection data were selected using the following Medidoc codes: 15362B.R, 15,365 A.A, 15,364 A.R, 15,362 J.R, 15,362 L.R, 15362K2R, 15,362 K.R, 15362Q.R, 15362Z.R, 15,362 M.R, 15,362 F.R, 15362K1R, 15362D.R, 15362E.R, 15362X.R. The daily minimum- and maximum temperature, were sourced from the Royal Meteorological Institute (RMI) of Belgium, measured at the Uccle weather station, and linked to the Intego registry.

To examine the short-term effects of heat and COVID-19 on mortality, we employed a time-stratified case-crossover design using aggregated daily mortality data. In this approach, each day with observed deaths serves as a case day. We defined strata based on Day-of-Weak (DOW), Month and Year (DOW-Month-Year). This matching strategy enables comparisons within narrowly defined temporal strata, effectively controlling for time-invariant confounders as well as long-term and seasonal trends19,20,21.

Exposures and health outcome

We considered two primary exposures: daily minimum temperature and daily confirmed COVID-19 case counts. Based on our previous work18, daily minimum temperature was selected as primary meteorological exposure, which showed a stronger and more consistent association compared to mean and maximum temperatures. The daily minimum temperature also plays a critical role to capture nighttime heat stress. The outcome of interest in this study was all-cause daily mortality.

Data analysis

Within a time-stratified case-crossover design, we fitted conditional quasi-Poisson regression, integrated with a distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) to account for overdispersion in mortality counts and to capture the non-linear and delayed effects of temperature20,22.

The modeling approach centered on the interaction effects of heat and COVID-19. We first obtained a cross-basis matrix for a daily minimum temperature, which flexibly captures the potentially nonlinear and delayed association between exposure and outcome. For the exposure dimension, we specified a natural cubic spline (NS) with 3 degrees of freedom (df), and for lag effects, a NS with 2 df was used, allowing a maximum lag of 14 days. Knots for the exposure dimension were placed at equally spaced quantiles of the temperature distribution, whereas knots for the lag dimension were placed equally on the log scale of lag days (0–14), allowing greater flexibility at shorter lags23. Given that our analysis was restricted to the Belgian warm season (May to September), the df in the definition of the splines terms were decided carefully to minimize potential overfitting while preserving flexibility to capture key patterns.

We assessed the overlapping effects of heat and the COVID-19 pandemic through two complementary interaction-based approaches. The first introduced an interaction term between the temperature cross-basis and a binary indicator distinguishing pre-pandemic (2018–2019) and pandemic period (2020–2021). This led to creating two interaction terms by multiplying the full cross-basis by each period indicator, enabling us to have two separate cross-bases: one representing the temperature-mortality association before the pandemic, and the second capturing how this association may have changed during the pandemic. This allows us to estimate the temperature-lag-mortality association while quantifying whether the pandemic intensified the mortality risk associated with heat.

The second assessed the modifying effect of daily confirmed COVID-19 cases. We calculated a 15-day moving average of daily confirmed COVID-19 case counts, centered such that the index day corresponded to the last day of the moving window. This smoothing captures short-term variations and better reflected local transmission intensity. The analysis for this approach was restricted to the pandemic years (2020–2021). We then centered the moving average at three reference points representing 25th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the distribution, corresponding to low, mild and high intensity levels of COVID-19, respectively. This formulation allows us to quantify the temperature–mortality association across the COVID-19 intensity, capturing potential modification of heat effects under different epidemic conditions. We have also included the 15-day moving average of COVID-19 cases and temperature cross-basis as the main effect in the model alongside the interaction term.

All models were adjusted for potential covariates and confounders. We included an NS for relative humidity with 3 df to account for its non-linear influence on mortality. We quantified the cumulative relative risk (across 0–14 lag days) at the 99th percentile (P99) of daily minimum temperature compared to the 50th percentile (P50). To evaluate whether COVID-19 amplifies the heat-mortality association, we performed z-tests24. Pairwise comparisons were conducted both between the pre- and during-COVID-19 periods and across different COVID-19 intensity levels.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to check robustness of our findings. First, we assessed the cumulative risk over multiple lag periods, including lag 0, lag 0–3, lag 0–7 and lag 0–10 days. Second, we repeated the analysis using daily maximum temperature instead of minimum temperature.

All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.125, using the dlnm package22 and the gnm package20.

Results

The characteristics of daily all-cause mortality, confirmed COVID-19 cases and environmental variables was presented in Table 1. In total, 5,668 (May-September 2018–2021) mortality events and 5,967 (May-September 2020–2021) confirmed COVID-19 cases were included in the analysis. These represents a subset of the total mortality (14,065) and COVID-19 cases (63,680) recorded over the full years. The sex distribution was relatively balanced, with females accounting for 53% of deaths and 52% of COVID-19 cases. Most deaths occurred among older adults, with 42% in the 85 + and 40% in the 65–84 age group. COVID-19 cases, however, were predominantly acquired by those aged 0–64. Mortality was higher in 2020 and 2021 compared to the two years before, which likely corresponds to excess mortality during the pandemic.

The daily minimum temperatures ranged from 3.5 °C to 23.5 °C, whereas the minimum and maximum daily relative humidity was 34.1% and 90.8%, respectively.

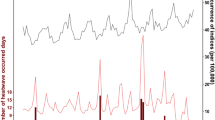

Figure 1 presents the time series of daily confirmed COVID-19 cases, all-cause mortality, and minimum temperature. From mid-2020 onwards, COVID-19 cases show notable peaks, particularly during the summer of 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 1, bottom panel). Mortality was relatively stable during 2018 and 2019,while an increase in daily mortality is observed in 2020 and 2021, coinciding temporally with the onset and progression of the pandemic. The minimum temperature is consistent across all years, peaking during summer.

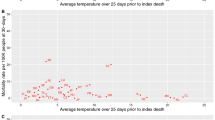

The cumulative RR for the association between daily minimum temperature and all-cause mortality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 2, top panel) and the intensity of daily COVID-19 transmission (Fig. 2, bottom panel), with low, mild, and high intensities corresponding to approximately 7, 31, and 49 cases per day, respectively. The curves exhibit a J-shaped pattern, suggesting that heat had a more pronounced impact on mortality, with elevated risks observed at higher temperatures.

We observed that the RR of mortality associated with high minimum temperatures increased more steeply during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the pandemic (top panel). While the pre-COVID-19 curve showed only a modest elevation in risk above the P50 (14 °C), the during-COVID-19 curve indicated a notably sharper rise. This suggests that extreme heat was associated with a substantially higher mortality risk during the pandemic. Based on the interaction of heat and COVID-19 intensity, we observed that the association between high temperature and mortality was significantly more pronounced on days with higher COVID-19 incidence. We observed minimal differences in the shape of association when we use maximum temperature instead of minimum temperature (Appendix Fig. S3). However, the confidence interval became wider, particularly at higher temperatures. This pattern was consistent across both binary and linear approaches.

Cumulative (lag 0–14 days) RR for the association between daily minimum temperature and all-cause mortality, estimated for pre- and during-COVID-19 periods (top panel) and levels of daily COVID-19 transmission intensity (bottom panel). The vertical dashed lines represent the 1st, 50th, and 99th percentiles of minimum temperatures. Shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of the estimates.

The cumulative RRs of all-cause mortality associated with extreme heat exposure, quantified at the P99 of minimum temperature relative to P50, were estimated using the binary- and linear interaction approach (Table 2). Using the binary approach, we observed a significantly elevated risk of mortality associated with extreme heat during COVID-19, with a RR of 1.55 (95% CI: 1.18–2.02). Although the pre-COVID-19 period also showed an increased risk (RR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.72–1.58), the association was weaker and did not reach statistical significance.

In the linear interaction models, which modeled heat as a function of smoothed COVID-19 case counts (using moving averages centered at different intensity levels), there was a clear exposure-response relationship, with extreme heat being strongly associated with an increased mortality risk as COVID-19 cases intensified. At lag 0–14, the RR of heat-related mortality increased with the level of daily COVID-19 case counts: it was 1.18 (95% CI: 0.64–2.18) when case counts were low, increased to 1.95 (95% CI: 1.03–3.70) during periods of mild case counts, and reached a markedly elevated RR of 3.57 (95% CI: 1.10, 11.61) when the intensity were high.

To complement these main findings, we also examined shorter lag periods. For lag 0 (same-day exposure), the RR was elevated during the COVID-19 (RR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.31–1.93). In contrast to the findings for the cumulative lag 0–14 days, we observed a significantly elevated risk during the pre- COVID-19 period at lag 0 (RR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.06–1.75; however, the magnitude of risk was lower than that observed during the COVID-19 period. This pattern persisted across lag 0–3, lag 0–7 and lag 0–10, where the difference between the two periods remained evident. Notably, while the pre-COVID-19 estimates tended to attenuate at longer lag (lag 0–10 and 0–14), the during-COVID-19 estimates remained stronger, highlighting an extended and stronger cumulative heat effect during the pandemic period. Similarly, in the linear interaction models, estimates across shorter lags, including lag 0–3, 0–7, and 0–10, consistently showed increased risk with increasing COVID-19 burden.

The Z-test comparison of period-specific RRs using the binary interaction approach suggested a borderline increase in heat-related mortality during the pandemic (z = 1.97, p = 0.049). The results from linear interaction approach on the other hand indicated an increase in heat-related mortality with higher COVID-19 intensity: low vs. mild (z = 1.68, p = 0.09), low vs. high (z = 2.35, p = 0.02), and mild vs. high (z = 3.49, p = 0.0005), with pairwise comparison presented in table S2 (see Appendix) .

The cumulative RR for maximum temperature relative to P50 is presented in Table S1 (see Appendix). The findings were generally similar to those for maximum temperature; however, the effect sizes were slightly lower, particularly at mild and high COVID-19 intensity.

Figure S1 (See appendix) shows the lag-response associations for heat-related mortality at the P99 of minimum temperature based on the binary (top panel) and linear (middle and bottom panels) interactions approach. Under the binary interaction approach, we observed an increased risk of mortality a few days after the exposure, and it persisted for a few more days, followed by a gradual decline in risk over subsequent days. In contrast, during the pre-COVID-19 period, although a short-term increase in risk was observed at lag 0, the magnitude of the association was notably smaller and did not reach statistical significance. A strong association was also observed using the linear interaction method, especially for mild and high COVID-19 intensity, several days after the exposure.

As a result of the exposure-lag-mortality risk association, we did not observe a strong rise in mortality risk when COVID-19 intensity were low (See Appendix Fig. S2). We observed an increase in the heat-related mortality risk during COVID-19 few days after the exposure and tend to decrease after about seven lag days. However, the RR for the pre-COVID-19 was consistently slightly above 1, but did not reached statistical significance. The risk becomes significantly increasing (at mild and high intensity), mostly at the late lag days, with notable effect of heat when viral transmission is more intense.

Discussion

Our study provides strong evidence that the impact of heat on all-cause mortality was significantly amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. We observed a relatively modest mortality risk associated with increasing daily minimum temperatures before the pandemic, however, the risk was sharper and more pronounced during the pandemic. On days with a higher intensity of COVID-19 cases, the excess risk associated with heat became increasingly pronounced. These results indicate that the pandemic introduced a new mortality risk on its own and amplified existing environmental risks, particularly extreme heat. These patterns persisted across various lag periods, with the pronounced cumulative effects observed over extended periods (lag 0–14 days), suggesting that the cumulative heat burden was greater when COVID-19 cases were high.

This compounded risk aligns with emerging biological and epidemiological evidence that simultaneous exposure, such as viral infection and heat stress, can overwhelm public health systems. Several studies have shown that both heat and COVID-19 contribute to mortality26,27,28,29. Our findings align with and extend the existing literature on heat-related mortality and the pandemic effects. Before the pandemic, several studies had already investigated that extreme temperatures are associated with elevated mortality26,27,28,29,30. The limited studies on the compounding effects of extreme heat and the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality mostly focused on the theoretical justification, with some trying to quantify the overlapping effects, leaving important gaps regarding the dynamic interplay of these risks. For example, Lo et al., (2024) analysed UK mortality data from 2020 to 2022, demonstrating that the impact of extreme heat during COVID-19 led to greater excess mortality31. However, their analysis treated COVID-19 as a contextual factor rather than directly including it in their statistical models, which missed accounting for the time-varying interactions and how the risk was different from the period before COVID-19. Nevertheless, they also found a diminished cold-related effects on mortality in the pandemic period compared to pre-pandemic years, suggesting that behavioral and societal changes during the COVID-19 may have differently influenced vulnerability to heat and cold. Our approach was built to explicitly address these gaps through binary and continuous effect modifiers, which enable us to robustly test whether and how the pandemic intensified heat-related mortality risk.

Recent studies highlighted excess mortalities due to heat and vulnerability patterns during the pandemic. According to Sousa et al. (2022), heat-related mortality in 2020 was indirectly amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, attributing this to reduced healthcare access and delayed heat adaptation strategies8. A study conducted in New York using a multi-hazard risk analysis found an overlapping mortality risk associated with heat and COVID-1932. In agreement with their findings, we also observed a more pronounced association between heat and mortality during COVID-19 than before. We also observed an increased risk, together with the increase in the intensity of the pandemic. Another recent study examined the association of heat and mortality, using pre-COVID-19 (2015–2019) and during COVID-19 (2020–2023) Eurostat data, covering 805 contiguous regions across 32 European countries. They observed a significant increase in heat-mortality risks in southern and western regions, including Belgium, during the pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period33. Studies also found an increase in heat-related mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic8,34. While earlier studies often attributed this amplification to indirect effects, such as social restrictions including lockdowns, or individuals not seeking healthcare due to fear of infection, our study provided deeper insights. In the current analysis, we showed that the rise of COVID-19 transmission rates themselves contributed substantially to the increased risk, which might be due to physiological strain, healthcare system pressure, or overlapping vulnerabilities in affected populations. This highlights that both behavioural disruptions and infectious disease burdens can interact with environmental hazards to exacerbate public health outcomes.

Our findings indicate that environmental and epidemiological burdens overlap, where the occurrence of extreme heat and outbreaks of infections resulted in elevated health risk31,35. Overall, the justification of these findings can be biological and epidemiological. From a biological point of view, the co-occurrence of multiple stressors, like heat and COVID-19, can exceed the adaptive capacity of individuals, especially for vulnerable population groups. The pandemic introduced physiological, psychological, and social stress, including restricted healthcare access, delayed treatment, social isolation, and anxiety, all of which may have amplified vulnerability to heat36,37. These findings may provide useful insights for public health planning and response. This suggests the importance of developing preparedness strategies that consider heat and pandemics jointly rather than as separate threats38,39. Our study provides actionable evidence supporting the integration of heat and a COVID-19 peak, particularly during periods of high disease transmission. Moreover, our study provided the methodological framework for future studies and a practical foundation for public health interventions. This remains relevant for national preparedness strategies, as future pandemics may emerge unpredictably. Unlike influenza, which typically peaks in winter, COVID-19 has shown significant impact during the hot season as well.

Interestingly, our study showed different pattern for the lag-specific heat-related mortality between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, though the association was weak across several lags. The decrease of heat-related risk after approximately 7 days of lag might be due to a degree of short-term mortality displacement. This pattern contrasts with the pre-COVID-19 period, where RRs remained slightly above 1 across all lags, reflecting a more persistent heat effect with limited evidence of displacement. An increased risk observed during periods of higher COVID-19 transmission was most evident at longer lag days, suggests that prolonged heat exposure may have had a relatively stronger cumulative effect on mortality.

Our study has several strengths. First, we employed a rigorous and methodologically robust frame- work to capture the complex interplay between heat and the COVID-19 pandemic. By combining DLNM with interaction-based approaches, we were able to flexibly model both immediate and delayed effects of heat on mortality while explicitly assessing how these effects varied when using dual strategies, including pre- and during-pandemic periods and incorporating real-time COVID-19 case intensity. This allowed us to assess structural shifts and dynamic amplifications in heat-related mortality risks. Second, our study covered the years 2018–2021, enabling a clear comparison between the pre- and during pandemic periods. Third, by focusing on the warm season and using a parsimonious modelling approach, we minimized overfitting while preserving sensitivity to detect meaningful patterns. Fourth, our findings are highly interpretable and policy-relevant, shedding light on how the overlapping extreme heat and infectious disease outbreaks can jointly exacerbate vulnerability, which may give insight on integrating early warning systems and health preparedness strategies during concurrent crises of pandemics and extreme heat events.

We also acknowledge some limitations. First, the association can also be bidirectional, as heat may have exacerbated underlying cardiovascular or respiratory conditions, leading to severe outcomes in individuals with COVID-19 cases. However, in the current study, we are unable to explore this reverse association due to a lack of deaths directly attributable to COVID-19. Second, while we adjusted for daily COVID-19 case counts using a smoothed moving average, these reported cases may still be subject to reporting delays, especially in the early phases of the pandemic, which might lead to exposure misclassification. Third, the COVID-19 case data used in this study are based on laboratory results recorded in primary care. This may not fully reflect the true disease burden at the time, as many cases where diagnosed in COVID-19 testing centers and hospitals. The availability of tests and the testing schedule may also affect how many cases are recorded.

Data availability

The authors are not allowed to share the data. Requests for aggregated INTEGO data can be made by sending a reasonable inquiry to [dpo.healthdata@sciensano.be.](mailto: dpo.healthdata@sciensano.be).

References

Zhao, Q. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health. 5, e415–e425 (2021).

Romanello, M. et al. Tracking progress on health and climate change in Europe. Lancet Public. Health. 6, e858–e865 (2021).

Lancet, Belgium LANCE, T COUNTDOWN ON HEALTH & AND CLIMATE CHANGE. : Health and climate change in Belgium. https://lancetcountdown.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Lancet-Countdown-2024_BELGIUM.pdf (2024).

Phung, D. et al. Ambient temperature and risk of cardiovascular hospitalization: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 550, 1084–1102 (2016).

Cui, J. & Sinoway, L. I. Cardiovascular responses to heat stress in chronic heart failure. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 11, 139–145 (2014).

Sanyaolu, A. et al. Global pandemicity of COVID-19: situation report as of June 9, 2020. Infect. Diseases: Res. Treat. 14, 1178633721991260 (2021).

Bose-O’Reilly, S. et al. COVID-19 and heat waves: new challenges for healthcare systems. Environ. Res. 198, 111153 (2021).

Sousa, P. M. et al. Heat-related mortality amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Biometeorol. 66, 457–468 (2022).

Renard, F. et al. Establishing an ad hoc COVID-19 mortality surveillance during the first epidemic wave in Belgium, 1 March to 21 June 2020. Eurosurveillance 26, 2001402 (2021).

Sciensano & Belgium COVID-19 epidemiological situation deaths. https://datastudio.google.com/embed/reporting/c14a5cfc-cab7-4812-848c-0369173148ab/page/QTSKB (2020).

Sciensano Surveillance of COVID-19 mortality in Belgium, epidemiology and methodology during 1st and 2nd wave. https://www.sciensano.be/en/biblio/surveillance-covid-19-mortality-belgium-epidemiology-and-methodology-during-1st-and-2nd-wave-march’ (2021).

Boni, Z., Bertel, D. & Adler, V. To stay or not to stay at home? The unintended consequences of public health advice for older adults in the context of Covid-19 and urban heat. Soc. Sci. Med. 348, 116838 (2024).

Pietrabissa, G. & Simpson, S. G. Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 11, (2020).

Sommerlad, A. et al. Social relationships and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analysis of the COVID-19 social study. Psychol. Med. 52, 3381–3390 (2022).

Haldane, V. et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 27, 964–980 (2021).

Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J. & Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health (1978). 74, 964–968 (2020).

StatBel. Structure of the population. https://statbel.fgov.be/en/themes/population/structure-population (2024).

Ali, E. A. et al. Associations of heat with diseases and specific symptoms in Flanders, belgium: an 8-year retrospective study of general practitioner registration data. Environ. Int. 193, 109097 (2024).

Tobias, A., Kim, Y. & Madaniyazi, L. Time-stratified case-crossover studies for aggregated data in environmental epidemiology: a tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 53, dyae020 (2024).

Armstrong, B., Gasparrini, A. & Tobias, A. Conditional Poisson models: a flexible alternative to conditional logistic case cross-over analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 1–6 (2014).

Wu, Y., Li, S. & Guo, Y. Space-time-stratified case-crossover design in environmental epidemiology study. Health Data Sci. 2021. (2021).

Gasparrini, A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: the package Dlnm. J. Stat. Softw. 43, 1 (2011).

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Kenward, M. G. Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat. Med. 29, 2224–2234 (2010).

Altman, D. G. Statistics notes: interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 326, 219–219 (2003).

R-team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org (2022).

Chen, T. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, china: a single-centered, retrospective study. Journals Gerontology: Ser. A. 75, 1788–1795 (2020).

Stokes, A. C. et al. COVID-19 and excess mortality in the united states: A county-level analysis. PLoS Med. 18, e1003571 (2021).

De Troeyer, K. et al. Heat related mortality in the two largest Belgian urban areas: A time series analysis. Environ. Res. 188, 109848 (2020).

Benmarhnia, T., Deguen, S., Kaufman, J. S. & Smargiassi, A. Vulnerability to heat-related mortality: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiology 26, 781–793 (2015).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 386, 369–375 (2015).

Lo, Y. T. E., Mitchell, D. M. & Gasparrini, A. Compound mortality impacts from extreme temperatures and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Commun. 15, 4289 (2024).

Ortiz, L., Mustafa, A., Cantis, P. H. & McPhearson, T. Overlapping heat and COVID-19 risk in new York City. Urban Clim. 41, 101081 (2022).

Paniello-Castillo, B., Quijal-Zamorano, M., Gallo, E., Basagaña, X. & Ballester, J. Regional changes in temperature-related mortality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a continental modelling analysis in 805 European regions. Environ. Res. 121697 (2025).

Lo, Y. T. E., Mitchell, D. M., Thompson, R., O’Connell, E. & Gasparrini, A. Estimating heat-related mortality in near real time for National heatwave plans. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 24017 (2022).

Morabito, M. et al. Heat warning and public and workers’ health at the time of COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140347 (2020).

Czeisler, M. É. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 69, (2020).

Park, H., Lee, S. M., Kim, W. J. & Chae, Y. Analysis of compound health impacts of heatwave and COVID-19 in Korea from May to September in 2020. Sci. Rep. 13, 14880 (2023).

Martinez, G. S., Kendrovski, V., Salazar, M. A., de’Donato, F. & Boeckmann, M. Heat-health action planning in the WHO European region: status and policy implications. Environ. Res. 214, 113709 (2022).

Zaitchik, B. F. et al. Planning for compound hazards during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of climate information systems. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, E704–E709 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Royal Meteorological Institute (RMI) of Belgium for providing environmental data.

Funding

Intego receives structural funding from the Flemish Department of Care. This specific study and Endale are supported by the Flanders Department of Care under the name SO Intego MGZ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Endale Alemayehu Ali** : Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software, Conceptualization. **Raf Aerts** : Writing—review & editing, Supervision. **Bert Vaes** : Writing—review & editing, Project administration. **Charlotte Scheerens** : Writing—review & editing, Supervision. **Simon Gabriel Beerten** : Writing—review & editing. **Elisa Duarte** : Writing—review & editing, methodology. **Gijs Van Pottelberg** : Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical consideration

For this specific study, approval were received from the ethical review board of the Medical School of the KU Leuven (S70796). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. INTEGO procedures were also approved by the Belgian Privacy Commission (no. SCSZG/13/079), and the ethical review board of the Medical School of the KU Leuven (no. ML 1723) (Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven), waived the requirement of informed consent and approved the INTEGO protocol.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, E.A., Aerts, R., Vaes, B. et al. The overlapping impacts of heat and COVID-19 on mortality in Flanders, Belgium: a time-stratified case-crossover analysis. Sci Rep 15, 44275 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25481-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25481-8