Abstract

Assessing water corrosivity indices is vital for sustainable management, since it damages infrastructure, increase costs, and threaten public health. In this study, the corrosive and scaling behavior of groundwater was modeled and predicted using, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS), and Random Forest (RF). Three indices were employed: the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI), the Ryznar Stability Index (RSI), and the Puckorius Scaling Index (PSI). The models were developed using 25 years of daily groundwater data from the Dezful-Andimeshk plain in southwestern Iran. In the study area, LSI values ranged from − 8.91 to 0.27, RSI from 8.46 to 18.72, and PSI from − 5.83 to 3.62, indicating that groundwater exhibits both corrosive and scaling tendencies depending on location. SAR (Sodium Adsorption Ratio), pH, and TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) were used as input variables for model development. Among the tested algorithms. The SVM model, performance metrics during the testing phase were as follows: LSI (R² = 0.92, RMSE = 0.11), RSI (R² = 0.81, RMSE = 0.21), and PSI (R² = 0.82, RMSE = 0.21). Overall, model comparisons indicated that all four algorithms achieved acceptable accuracy (R² = 0.80–0.93). However, MARS and ANN consistently provided superior and more stable performance, effectively capturing nonlinear and interactive relationships among the predictors. RF produced competitive results but did not show clear dominance over the other models in this dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groundwater is a vital natural resource crucial in meeting essential needs across various sectors, including domestic, agricultural, and industrial uses. Among all available water sources, groundwater is the most decentralized and dependable, serving millions of rural and urban households. Over the years, increasing water demand has led to significant water scarcity in many parts of the world1. In this context, evaluating the hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater has become a key priority2.

Multiple factors, such as geological formations, the extent of chemical weathering, recharge quality, water table level, and surface-derived elements, influence groundwater quality. Consequently, groundwater quality is governed by the interplay between geological and hydrological processes. Groundwater is only valuable when its quality is suitable for drinking, agricultural, and industrial applications. Its appropriateness for a specific use depends on established water quality standards. As such, groundwater quality is a critical parameter in regional water resource management and significantly affects water usage patterns3,4.

Among the key indicators for assessing groundwater quality are its corrosive and scaling potential. Water can corrode pipelines and distribution systems or cause the formation of thick deposits on the surfaces of heat exchange equipment. Corrosion is a physicochemical reaction between materials and their surrounding environment, leading to material degradation. This process results in the dissolution and release of micro-contaminants, such as copper, lead, cadmium, zinc, iron, and manganese, into the water, negatively affecting both water aesthetics and safety, and creating significant economic and health concerns. On the other hand, scaling increases the hydraulic roughness of water distribution networks, leading to higher energy costs and system wear5.

Several indices have been developed to evaluate water’s scaling and corrosive characteristics, including the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI), Ryznar Stability Index (RSI), and Puckorius Scaling Index (PSI). These indices rely on hydrochemical parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), temperature, total hardness (TH), and alkalinity6,7.

Numerous studies have investigated groundwater and surface water corrosion and scaling potential. For instance, Asghari et al.8 assessed the corrosive and scaling tendencies of drinking water distribution networks in the cities of Khoy (groundwater) and Maku (surface water) using LSI, RSI, PSI, Larson Index, and Aggressiveness Index. Their measurements included physical, chemical, and microbial parameters such as pH, electrical conductivity, TDS, total hardness, alkalinity, sulfate, chloride, and residual chlorine. The findings indicated that the water in both cities tended to be corrosive, with significant seasonal variations in corrosion indices.

Similarly, Omeka et al.9 evaluated groundwater’s hydrogeochemical characteristics, water quality, and scaling/corrosion potential in Ogbaru, Nigeria. Their results revealed that the groundwater was typically warm, acidic, and temporarily hard, with only 21.05% of samples suitable for drinking. Most samples were found to be hazardous to metal distribution systems.

Zhang et al.10 reviewed corrosion and scale formation in unlined cast iron pipes in drinking water distribution systems (DWDSs) in locations such as Beijing and Hangzhou (China) and Flint, Michigan, and Tucson, Arizona (USA). Using LSI, RSI, and the Aggressiveness Index (AI), they found that corrosion can be uniform or localized (e.g., pitting or crevice corrosion), often degrading water quality. They also observed that scales tend to be multilayered, with inner layers composed of Fe(OH)₂ and outer layers consisting of FeOOH, Fe₃O₄, and Fe₂O₃. Over time, unstable phases such as γ-FeOOH transition into stable ones like α-FeOOH and Fe₃O₄.

Kuznietsov11 analyzed the corrosion and scaling potential in the cooling water system of the Rivne nuclear power plant (Ukraine), using physicochemical monitoring data. Water samples were collected three times daily from 2022 to 2023, and parameters such as pH, temperature, TDS, TH, and total alkalinity (TA) were measured. LSI and RSI were computed, showing average values of 1.51 ± 0.39 and 5.74 ± 0.69, respectively, indicating a strong tendency toward scale formation. A strong negative Pearson correlation (ρ = − 0.9635) was observed between LSI and RSI, while the correlation between φ–ψ and the indices was weaker. These insights could aid in optimizing water treatment strategies in nuclear facilities.

Nowadays, with the advanced adoption of machine learning techniques in the field of water engineering, many issues are being investigated and modeled using these tools12,13,14,15. For example, El Bilali et al.16 employed machine learning algorithms to predict groundwater quality for agricultural use in the Berrechid aquifer, Morocco. Their dataset included 520 samples with 14 water quality parameters. Inputs such as EC, temperature, and pH were used to model outputs including TDS, potential salinity (PS), sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR), and residual sodium carbonate (RSC). Among the evaluated models—Adaboost, RF, ANN, and SVR—Adaboost and RF had the highest prediction accuracy, while ANN and SVR demonstrated better generalization and stability.

Sahour et al.17 evaluated machine learning models for groundwater quality prediction in an unconfined aquifer in northern Iran. Data from 248 monitoring wells were used to calculate and classify the Groundwater Quality Index (GWQI). Influential factors such as proximity to industrial and residential areas, population density, aquifer transmissivity, precipitation, evaporation, geology, and elevation were incorporated into a GIS environment. Among six ML models (XGB, RF, SVM, ANN, KNN, GCM), the RF model showed the highest performance with an accuracy of 0.92 and an ROC of 0.95.

Haggerty et al.18 conducted a comprehensive review of machine learning (ML) applications in groundwater quality modeling. The study analyzed supervised, semi-supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid models for predicting water quality parameters. Iran and the U.S. were among the studied regions, with nitrate being the most frequently modeled parameter. The review identified neural networks as the most commonly used ML models in groundwater quality research.

Torres-Martínez et al.19 also reviewed ML applications in groundwater quality prediction, analyzing 230 peer-reviewed articles. 83% of studies overlooked data preprocessing, and only 15% addressed model interpretability: tree-based models, particularly RF and XGB, significantly enhanced prediction accuracy.

Ruiz et al.20 investigated corrosion rate prediction in industrial cooling water pipelines using advanced ML techniques. Data were collected from a steel plant, including pH, temperature, free chlorine, conductivity, and redox potential. Two modeling approaches were explored: developing a virtual sensor to estimate corrosion rates and building a predictive tool for future corrosion trends. Among the applied models—deep neural networks, LSTM, and CNN—the dense neural network performed best for corrosion rate estimation, while CNN outperformed others in trend prediction.

Khaledi et al.21 developed an intelligent model using AI techniques to predict corrosion and scaling potential (CSP) in industrial cooling water systems. They used nine years of water quality data from electric arc furnaces in Khuzestan Steel Company, including pH, alkalinity, TH, TDS, chloride, turbidity, suspended solids, and dissolved iron. Four models—multiple linear regression (MLR), multiple nonlinear regression (MNLR), and multilayer perceptron artificial neural network (ANN-MLP)—were evaluated. ANN-MLP performed best (R² = 0.75, MAE = 0.34, RMSE = 0.35). Total hardness and chloride were identified as the most influential variables.

A review of the literature reveals that evaluating the scaling and corrosive indices of water is a critical component in assessing water quality. Moreover, existing studies indicate that the potential of machine learning models has not yet been fully explored for predicting these specific characteristics. Therefore, this study employs advanced machine learning techniques including artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machines (SVM), multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), and random forests (RF) to estimate the scaling and corrosive potential of groundwater based on the indices as mentioned earlier.

The research gap addressed in this study lies in the fact that many previous works have either relied on classical models or focused on a single machine learning algorithm, while often overlooking long-term spatiotemporal information and model generalizability. By using 25 years of data and simultaneously comparing four diverse algorithms (ANN, SVM, MARS, RF), this study aims to propose alternative, cost-effective approaches for estimating corrosivity and scaling indices—particularly in cases where key parameters (e.g., Ca or alkalinity) are unavailable.

Materials and methods

Study area

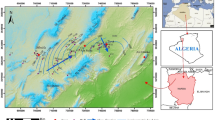

The Dezful-Andimeshk Plain is one of Iran’s most significant agricultural plains and the largest within the Dez River basin. It covers an area of 2,286 square kilometers and is located in the southwestern region of Iran (Fig. 1: Generated by QGIS version 3.40 (https://qgis.org)), within Khuzestan Province. It extends from the mountainous northern part of the province to the lower-elevation central areas. Geographically, the plain lies between latitudes 31°51′ and 33°35′ N, and longitudes 45°50′ and 48°14′ E.

This region experiences a hot and arid climate and is classified as semi-arid based on the De Martonne classification method. The average annual temperature ranges from 24 to 24.6 °C, with the highest monthly average reaching up to 32 °C in July. The lowest temperatures are recorded in January, ranging from 15 to 16.2 °C.

Annual precipitation varies across the region, with approximately 634 mm recorded in the mountainous zones and 300 to 345 mm in the plain areas. The mean annual evaporation rate is estimated to be between 2,470 and 2,524 mm22.

The Dezful-Andimeshk Plain is primarily used for agricultural purposes, with over 90% of irrigation water supplied by the downstream irrigation network of the Dez Dam. The general direction of groundwater flow is from the north and northwest towards the south and southeast. Groundwater table elevations range from a maximum of 140 m in the northern part of the plain to a minimum of 55 m in the southern areas23.

Study area and sampling locations. Map generated using QGIS version 3.40 (Available at https://qgis.org).

The statistical properties of the groundwater quality data of the study area, such as minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation, were calculated and summarized in Table 1. The violin graph of parameters of Table 1 are shown in Fig. 2. The violin plots were generated (Fig. 2) to visualize the distribution and concentration of each variable. These plots are particularly useful in identifying outliers and understanding the data distribution.

Review on corrosivity and scaling indices

In this study, to examine the corrosivity and sedimentation behavior of groundwater in the studied region, the following indices were used: the Langlier Saturation Index (LSI), Ryznar Stability Index (RSI), and Puckorius Stability Index (PSI).

The Langlier Saturation Index (Eq. 1) is a key indicator for assessing the potential of water to form calcium carbonate deposits. Calcium carbonate is one of the most common minerals found in water and is considered the primary element responsible for deposit formation24.

The Ryznar Stability Index indicates the effect of parameters such as calcium, total alkalinity, dissolved solids, and temperature on the calculation of saturation pH (pHs). This index is a modified version of the Langlier index, and unlike the Langlier, it yields positive values.

The Puckorius Stability Index evaluates the potential for water to be either corrosive or sediment-forming. The numerical values of this index indicate the water’s status, as given in Table 2, where it is categorized as either corrosive or sediment-forming. This index is also known as the Practical Sedimentation Index. Unlike the other three indices, it is not directly related to the actual pH of the water. Instead, the values of this index are influenced by the water’s buffering capacity, and for this calculation, the pH of saturation (pHs) is used instead of the actual pH of the water.

In this context:

-

pHs refers to the pH of water saturated with calcium carbonate,

-

A represents the TDS values of water (mg/L),

-

B is the water temperature (°C),

-

C refers to calcium hardness (mg/L as CaCO₃), and.

-

D denotes the water alkalinity (mg/L as CaCO₃)25.

The relevant data for the mentioned indices are presented in Table 2.

To comprehensively assess the performance of different machine learning approaches for predicting groundwater corrosion and scaling indices, we selected four widely used models: Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS), and Random Forest (RF). These models were chosen to represent diverse modeling strategies: ANN is well-suited for capturing complex nonlinear relationships, SVM performs robustly with high-dimensional data and limited samples, MARS effectively identifies nonlinear interactions between predictors, and RF provides high accuracy and resilience against overfitting through ensemble learning. By including these models, we aim to compare their predictive capabilities and identify the most effective approach for our dataset, ensuring a thorough and reliable analysis aligned with the study objectives28,29.

Artificial neural networks

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are powerful tools in the field of soft computing, utilized for modeling and predicting complex and nonlinear phenomena in water30. These networks are inspired by the human brain’s structure and functioning, and they can learn complex patterns from data. An artificial neural network comprises small processing units known as “neurons,” organized into various layers. Each neuron receives input data, combines it with specific weights, and then applies an activation function to generate an output. The overall structure of neural networks consists of three layers:

-

Input Layer: This layer receives the input data that enters the network.

-

Hidden Layers: These layers extract features and learn complex patterns from the data.

-

Output Layer: The final results of the model are extracted from this layer.

Each neuron in the artificial neural network operates as follows:

Where: \(\:{x}_{i}\:\)represents the neuron’s inputs, \(\:{w}_{i}\) denotes the weights corresponding to each input, \(\:b\) is the bias, and \(\:z\) is the weighted sum of the inputs. The output of the neuron is then calculated by applying an activation function \(\:f\) as follows:

Some common activation functions are as follows:

The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm is a numerical optimization method for training neural networks and minimizing error functions. This algorithm is a combination of “gradient descent” and the “Gauss-Newton method” and is particularly suitable for nonlinear least squares problems due to its fast convergence speed28.

Support vector machine (SVM)

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a powerful machine learning method used for classification and regression. This model is widely applied in water engineering to model and predict complex and nonlinear phenomena. SVM separates data in the feature space using an optimal hyperplane, making it an excellent tool for solving complex problems in the water domain, especially when dealing with high-dimensional and nonlinear data. The primary goal of SVM in classification tasks is to find an optimal hyperplane that separates data from two classes with the maximum margin. For linearly separable data, this hyperplane is defined as follows:

In this equation:

-

\(\:w\) represents the weight vector,

-

\(\:x\) represents the input feature vector,

-

\(\:b\) is the bias term.

The margin is defined as the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data points of each class. SVM aims to maximize this margin, equivalent to minimizing the norm of the weight vector \(\:{‖w‖}^{2}\). Thus, the optimization problem is formulated as follows:

Subject to:

Where \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the class label (+ 1 or – 1) for the data point \(\:{x}_{i}\) . For data that is not linearly separable, the kernel trick is used29,31,32. In this approach, the data are mapped to a higher-dimensional space in which they become linearly separable. Some commonly used kernel functions are as follows:

In the regression problem, the goal is to predict a continuous value.

Multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS)

The multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) model is a powerful technique for modeling nonlinear and complex relationships between input and output variables. This method uses a combination of basis functions to create a flexible and adaptive model. MARS is widely used in water engineering for modeling and predicting complex phenomena such as river flow, water quality, and precipitation.

Basis functions

MARS uses piecewise linear basis functions to model nonlinear relationships. These functions are defined as follows:

Where:

-

x is the input variable.

-

c is the knot point, where the slope of the function changes.

The MARS model is defined as a combination of piecewise linear basis functions, which are expressed as follows:

Where:

-

\(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\) is the intercept (bias term).

-

\(\:{\beta\:}_{m}\) are the model coefficients.

-

\(\:{h}_{m}\left(x\right)\) are the basis functions.

In this case, the MARS model is expressed as a sum of basis functions \(\:{h}_{m}\left(x\right)\) weighted by the coefficients \(\:{\beta\:}_{m}\), with the intercept \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\)included as the base term. This structure allows the model to capture both linear and nonlinear patterns in the data, where the basis functions \(\:{h}_{m}\left(x\right)\) represent the piecewise linear segments, and the coefficients \(\:{\beta\:}_{m}\) control the contribution of each segment to the final prediction.

The MARS training process consists of two stages32:

1. Forward Pass: In this stage, basis functions are recursively added to the model to create the best approximation of the data. The best knot point c and the best basis function hmx are selected at each step.

2. Backward Pass: In this stage, less important basis functions are removed from the model to prevent overfitting.

Mathematical foundations of the random forest algorithm

Random Forest is one of the most powerful machine learning algorithms for classification and regression tasks. It operates by constructing an ensemble of decision trees and has demonstrated significant effectiveness in modeling and predicting complex, nonlinear phenomena, especially in water engineering. By applying techniques such as bagging and random feature selection, Random Forest mitigates the risk of overfitting and produces reliable and robust results33.

Decision tree

A decision tree is a predictive model that utilizes a tree-like structure to split the dataset into subsets based on feature values. Each internal node represents a feature, each branch corresponds to a decision rule, and each leaf node indicates an output (either a class or a value). Decision trees commonly use splitting criteria such as entropy or the Gini index to partition the data.

Entropy

Entropy is a metric that quantifies the impurity or uncertainty within a dataset. For a dataset S consisting of \(\:C\) classes, entropy is calculated as follows:

Where: \(\:{p}_{i}\) is the proportion of samples belonging to class i in dataset S, \(\:{log}_{2}\left({p}_{i}\right)\) is the base-2 logarithm of the probability \(\:{p}_{i}\).

The lower the entropy, the less impurity exists within the dataset. Therefore, a dataset with low entropy is more homogeneous. The primary objective of constructing a decision tree is to minimize entropy at each split, ensuring that each resulting subset contains more uniform data.

Gini index

The Gini Index is another metric used to evaluate the impurity or diversity of a dataset. It is calculated as follows:

Where:

\(\:{p}_{i}\:\)represents the proportion of samples belonging to class i in the dataset S.

Similar to entropy, the Gini Index measures the impurity of a dataset. A lower Gini value indicates a purer node with less impurity in the data. Therefore, minimizing the Gini Index at each split enhances the homogeneity of the resulting subsets34,35.

Simulation scenarios and evaluation criteria

To develop each machine learning model (MLM), input variables including SAR, pH, and TDS data from the statistical period were used. Notably, the target variable for the model development was one of the three indices mentioned. The performance of utilized MLM two quantitative statistics: (1) coefficient of determination (R2), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) where their formula are given in Table 3, were used, P̅ the average of expected values, and G̅ the average of observed values36,37.

Results and discussion

This section presents the results of modeling and estimating the indices that characterize groundwater’s scaling and corrosive properties using the aforementioned soft computing models. As these models are data-driven, the initial step in their development involved preprocessing and validating the collected dataset. Subsequently, the correlation between the input variables—pH, TDS, and SAR—and the target indices (three indicators related to scaling and corrosion potential) was evaluated. The results of this correlation analysis are illustrated in Fig. 3, which demonstrates the relationships between pH, TDS, SAR, and the selected indices.

The findings indicate that pH is the most influential factor affecting the scaling indices. A strong positive correlation (r = 0.83) between pH and LSI suggests that an increase in pH directly raises the LSI value, enhancing the likelihood of scale formation. Conversely, pH negatively correlates with the RSI (Ryznar Stability Index) (r = -0.5), indicating that higher pH levels reduce RSI values, making the water less corrosive. A moderate positive correlation (r = 0.48) was also observed between pH and PSI, confirming the effect of pH on this index.

Among the remaining parameters, TDS also has a notable influence on scaling indices, although to a lesser extent than pH. The moderate positive correlation between TDS and LSI (r = 0.16) indicates a marginal impact of dissolved solids on scale formation. TDS is negatively correlated with RSI, suggesting that higher concentrations of dissolved solids may reduce these indices. Additionally, TDS shows a moderate positive correlation with PSI (r = 0.36), highlighting its potential role in increasing this index.

On the other hand, SAR (Sodium Adsorption Ratio) exhibits the least impact on the scaling indices. The correlation between SAR and all indices is negligible, implying that SAR does not directly influence either the scaling or the corrosiveness of the water in this study.

Overall, the results suggest that pH is critical in controlling scaling indices, with TDS acting as a secondary factor. In contrast, SAR can be considered negligible in this context. Accordingly, water quality management should primarily focus on pH regulation and monitoring TDS levels to prevent scale formation or corrosion.

These findings align with the results reported by Kuznietsov11, which similarly emphasize the dominant influence of pH on scaling indices. The Kuznietsov study confirms a strong positive correlation between pH and LSI and a negative correlation with RSI, which is consistent with the present research. Both studies agree that increasing pH leads to higher LSI values (more scaling) and lower RSI values (less corrosiveness).

Both investigations acknowledge TDS’s moderate effect on the indices, though less significant than that of pH. Kuznietsov11 reported positive correlations between TDS and both LSI and PSI and negative correlations with RSI and PRI—findings that closely align with those of this study. This supports the role of TDS as a complementary factor, albeit secondary to pH.

However, a slight divergence arises concerning the influence of SAR. While this study reports negligible correlation values for SAR, the Kuznietsov11 study attributes slightly more importance to SAR, particularly under specific water quality conditions. Their analysis focused on the cooling water of the Rivne nuclear power plant in Ukraine, characterized by unique physicochemical properties—such as high total hardness (TH), total alkalinity (TA), and chloride content—that may amplify the role of SAR.

This discrepancy likely stems from the differing sample compositions across the two studies. Nevertheless, the Kuznietsov11 study essentially confirms the key findings of the present research, particularly the dominant role of pH and the supporting role of TDS in scaling behavior. The difference regarding SAR highlights the need for further investigation to precisely determine the impact of this parameter under various water quality conditions. The distribution of all three corrosivity and sedimentation indices (LSI, RSI, and PSI) about the input parameters (SAR, pH, and TDS) is illustrated in Fig. 4. The histograms of these input parameters are also presented in the exact figure.

To develop the soft computing models, the collected data must be divided into two categories: training (for model development and calibration) and testing (for validation). Typically, data allocation follows ratios of 70 − 30 or 80 − 20. This means that 70% or 80% of the data is used for training and calibrating the models, while the remaining 30% or 20%, which did not participate in the calibration phase, is used for validation. Given the nature of the data, a random selection approach was employed to assign the data to the training and testing groups. Notably, during the data allocation process, both 70 − 30 and 80 − 20 ratios were considered. Initial assessments indicated that increasing the training set’s share from 70% to 80% did not significantly impact model performance due to the large data volume.

For the development of the multilayer artificial neural network (MLPNN) model, a trial-and-error approach was applied to design the network structure, although leveraging the experiences of other researchers in this area is also valuable. The design of the multilayer artificial neural network involves determining the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons in each layer, and the activation function governing each neuron. The structure of the developed neural network model is shown in Fig. 4. As indicated by this figure, the developed model consists of two hidden layers, with 5 neurons in the first layer and 3 neurons in the second layer. After testing various activation functions, the hyperbolic tangent function demonstrated optimal performance.

The statistical evaluation indicators for the performance of the MLPNN model in predicting each of the three scaling and corrosivity indices (LSI, RSI, and PSI) during both the training and testing phases are presented in Table 4. As shown in the table, the statistical indices of the MLPNN model for predicting the LSI index in the testing phase are R² = 0.90 and RMSE = 0.11, for RSI R² = 0.78 and RMSE = 0.23, for PSI R² = 0.80 and RMSE = 0.22. A comparison of the MLPNN model’s performance in predicting each scaling and corrosivity indices, further discussed in the table, shows that the model performs satisfactorily in estimating the LSI index but has weaker performance in evaluating the other indices. This can be attributed to the greater variability in the values of these indices.

Next, a SVM model was developed to estimate the deposition and corrosivity indices. It is important to note that the same training and testing data used for producing the MLPNN model were also used to create the SVM model. The most critical aspect of developing the SVM model is the selection of the kernel function. This study examined three kernel functions—polynomial, radial, and linear. As given in Table 5, the radial basis function (RBF) kernel provided the best performance. The statistical indicators for the developed SVM model (considering the performance of different kernel functions) in both the training and testing phases are presented in Table 5.

The statistical indicators for the SVM model (Tables 4 and 5) in estimating the LSI index during the training phase are R² = 0.92 and RMSE = 0.11. For the RSI index, R² = 0.81 and RMSE = 0.21; for the PSI index, R² = 0.82 and RMSE = 0.21. A comparison of the performance of the SVM model with the MLPNN model, referring to Table 4, reveals that, in both the training and testing phases, the statistical indicators are almost identical. It is worth noting that the values of gamma (γ) and the sigma parameter for the radial kernel function in estimating each index are as follows: for LSI, δ = 23.27 and γ = 1.54; for RSI, δ = 19.65 and γ = 0.77; for PSI, δ = 14.25 and γ = 0.63; and for PRI, δ = 8.94 and γ = 0.48.

The results of modeling and predicting the corrosivity and deposition indices using the MARS model are presented below. For this purpose, the same training and testing datasets (used for developing the MLPNN and SVM models) were also used for calibrating and validating the MARS model. The mathematical model derived from the MARS model for estimating the LSI index is presented in Eq. 18, with the coefficients of each of the basic functions provided in Table 6.

Reviewing this table shows that, in the developed mathematical model based on MARS, the SAR and pH parameters play the most significant roles, respectively. Notably, the initial partition of the input variable space is done by the pH parameter, followed by the SAR parameter. The mathematical model derived from the MARS model for estimating the LSI index is presented in Eq. 19, and the coefficients of each basic function are shown in Table 7.

This table indicates that in the developed model, the TDS and SAR parameters play the most significant roles, respectively. The initial partition of the input space is again done by the pH parameter, followed by the aforementioned parameters. Similarly, the mathematical model derived from MARS for estimating the PSI index is presented in Eq. 20, and the coefficients of the basic functions are shown in Table 8.

A comparison of the performance of the MARS model with the two SVM and MLPNN algorithms indicates that, in both training and testing phases, the statistical indices for estimating the examined indices are nearly identical.

Next, the results from modeling and estimating the corrosivity and deposition indices using the Random Forest model are presented. In the Random Forest model, the most influential parameters are identified. To develop the Random Forest model for estimating the LSI index, 400 trees were considered, and the final model converged with around 100 trees, with adding more trees not resulting in significant improvements in the model’s accuracy. The error changes versus the number of trees are shown in Fig. 5. The performance evaluation indices for the Random Forest model in the training and testing phases for estimating the three indices LSI, RSI, and PSI are provided in Table 4. The performance comparison of the RF model with the previous three models indicates that during the training phase, its accuracy is comparable to—and in some cases slightly higher than—the other models, whereas in the testing phase, its accuracy remains comparable but is slightly lower than that of the other models. The distribution of the results of the Random Forest model in the training and testing phases for estimating each of the three indices is shown in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. As indicated, the results of the Random Forest model are closely aligned with the excellent fit line, demonstrating the model’s precision and reliability.

It is worth noting that the performance of these models was evaluated and compared using Taylor diagrams in the training and testing phases, as shown in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the performance of four machine learning models (ANN, SVM, MARS, and RF) in predicting the LSI, RSI, and PSI indices during the training and testing phases, respectively, using Taylor diagrams. These diagrams allow simultaneous comparison of three key metrics—correlation coefficient, standard deviation, and RMS error—thereby providing a comprehensive overview of model accuracy and stability. During the training phase (Fig. 8), MARS and ANN exhibited the highest correlation with observed values, and their standard deviations closely matched the observed data, highlighting the superior capability of these models to capture nonlinear and complex relationships between input variables and the indices. SVM also delivered satisfactory performance, though its accuracy for some indices was slightly lower than that of ANN and MARS. In contrast, RF demonstrated reasonable accuracy during training but showed greater deviation from the reference point, indicating a lower tendency to overfit and a more balanced trade-off between accuracy and stability. In the testing phase (Fig. 9), which serves as the primary criterion for evaluating model generalizability, a similar pattern emerged. MARS and ANN maintained their superiority, achieving higher correlations with observed data than the other models. SVM performed comparably, although minor drops in accuracy were observed for certain indices. RF produced competitive results, yet it did not outperform the other models, with correlations slightly lower than those of the top-performing models.

Overall, the results from Figs. 8 and 9 indicate that all four models are capable of predicting sedimentation and corrosion indices effectively. However, MARS and ANN demonstrated greater stability and accuracy across both training and testing phases. These findings underscore the importance of selecting models that align with the nature of the data and the structure of the indices, suggesting that flexible models such as MARS and ANN can provide more reliable tools for monitoring and managing groundwater quality in semi-arid regions.

Conclusion

By integrating long-term hydrochemical records (25 years) with four soft computing techniques (ANN, SVM, MARS, and RF), this study assessed the predictive capacity of artificial intelligence models for groundwater scaling and corrosivity indices. Results demonstrated that pH is the dominant factor governing index dynamics, exerting a significant and direct influence on increasing LSI and reducing RSI. TDS was identified as a secondary yet meaningful driver for some indices, whereas SAR exhibited only minor effects. Performance evaluation confirmed that all four algorithms achieved reliable predictions, though MARS and ANN showed distinct advantages in modeling nonlinear and complex interactions. While RF yielded stable and accurate predictions, it did not consistently outperform the competing models, indicating that model selection should be guided by data characteristics, index structure, and management objectives rather than algorithm popularity. From a management perspective, the findings emphasize the critical importance of closely monitoring pH and TDS in semi-arid groundwater systems. Artificial intelligence models provide a proactive decision-support tool, enabling water managers to anticipate potential scaling and corrosion challenges and implement corrective measures before severe impacts arise in supply networks. For future research, we recommend extending model development by incorporating additional hydrochemical parameters (e.g., total alkalinity, total hardness, and temperature), applying advanced spatiotemporal validation techniques, and testing model transferability across diverse climatic and geological domains. Such advancements could foster the establishment of a comprehensive, transferable framework for intelligent groundwater monitoring and sustainable resource management.

Data availability

Data supporting this study are openly available from the corresponding author.

References

Ali, S. & Negm, A. Groundwater in Developing Countries: Case Studies from MENA, Asia and West Africa. (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-79122-2.

Jha, R., Singh, V. P., Singh, V., Roy, L. B. & Thendiyath, R. Groundwater and Water Quality: Hydraulics, Water Resources and Coastal Engineering. vol. 119 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

Tajbakhshian, M. Groundwater quality and hydrogeochemical challenges in the Sarakhs Plain, NE Iran: a call for sustainable management. Environ. Geochem. Health. 47, 75 (2025).

Vesali Naseh, M., Noori, R., Berndtsson, R., Adamowski, J. & Sadatipour, E. Groundwater pollution sources apportionment in the Ghaen Plain, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 15, 172 (2018).

Alipour, V., Dindarloo, K., Mahvi, A. H. & Rezaei, L. Evaluation of corrosion and scaling tendency indices in a drinking water distribution system: a case study of Bandar Abbas city, Iran. J. Water Health. 13, 203–209 (2015).

Eslami, F., Salari, M., Yousefi, N. & Mahvi, A. H. Evaluation of quality, scaling and corrosion potential of groundwater resources using stability index; case study Kerman Province (Iran). Desalin. Water Treat. 179, 19–27 (2020).

Gholizadeh, A. et al. Assessment of corrosion and scaling potential in groundwater resources; a case study of Yazd-Ardakan Plain, Iran. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 5, 59–65 (2017).

Asghari, F. B., Jaafari, J., Yousefi, M., Mohammadi, A. A. & Dehghanzadeh, R. Evaluation of water corrosion, scaling extent and heterotrophic plate count bacteria in asbestos and polyethylene pipes in drinking water distribution system. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 24, 1138–1149 (2018).

Omeka, M. E., Egbueri, J. C. & Unigwe, C. O. Investigating the hydrogeochemistry, corrosivity and scaling tendencies of groundwater in an agrarian area (Nigeria) using graphical, indexical and statistical modelling. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1233 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Review on corrosion and corrosion scale formation upon unlined cast iron pipes in drinking water distribution systems. J. Environ. Sci. 117, 173–189 (2022).

Kuznietsov, P. Evaluation of the scaling and corrosive potential of the cooling water supply system of a nuclear power plant based on the physicochemical control dataset. Data Brief. 54, 110347 (2024).

Bordbar, M., Neshat, A., Javadi, S. & Shahdany, S. M. H. A hybrid approach based on statistical method and Meta-heuristic optimization algorithm for coastal aquifer vulnerability assessment. Environ. Model. Assess. 26, 325–338 (2021).

Goodarzi, M. R., Niknam, A. R. R., Barzkar, A. & Shishebori, D. River water flow prediction rate based on machine learning algorithms: a case study of Dez River, Iran. in River, Sediment and Hydrological Extremes: Causes, Impacts and Management (eds (eds Pandey, M., Gupta, A. K. & Oliveto, G.) 203–219 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4811-6_11. (2023).

Niknam, A. R. R., Sabaghzadeh, M., Barzkar, A. & Shishebori, D. Comparing ARIMA and various deep learning models for long-term water quality index forecasting in Dez River, Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 32, 10206–10222 (2024).

Paryani, S., Neshat, A. & Pradhan, B. Spatial landslide susceptibility mapping using integrating an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) with two multi-criteria decision-making approaches. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 146, 489–509 (2021).

El Bilali, A., Taleb, A. & Brouziyne, Y. Groundwater quality forecasting using machine learning algorithms for irrigation purposes. Agric. Water Manag. 245, 106625 (2021).

Sahour, S. et al. Evaluation of machine learning algorithms for groundwater quality modeling. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 46004–46021 (2023).

Haggerty, R., Sun, J., Yu, H. & Li, Y. Application of machine learning in groundwater quality modeling—a comprehensive review. Water Res. 233, 119745 (2023).

Torres-Martínez, J. A., Mahlknecht, J., Kumar, M., Loge, F. J. & Kaown, D. Advancing groundwater quality predictions: machine learning challenges and solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 949, 174973 (2024).

Ruiz, D., Casas, A., Escobar, C. A., Perez, A. & Gonzalez, V. Advanced machine learning techniques for corrosion rate estimation and prediction in industrial cooling water pipelines. Sensors 24, 3564 (2024).

Khaledi, M., Mehrabadi, A. R. & Mirabi, M. Developing an innovative corrosion and scaling index for industrial cooling water using artificial intelligence. J. Water Process. Eng. 65, 105838 (2024).

Hoseinizade, A., Seyed Kaboli, H., Zarei, H. & Akhond ALi, A. M. The intensity and return period of drought under future climate change scenarios in Dezful, Iran. Irrig. Sci. Eng. 39, 33–43 (2016).

Rezaei, M., Mousavi, S. F., Moridi, A., Eshaghi Gordji, M. & Karami, H. A new hybrid framework based on integration of optimization algorithms and numerical method for estimating monthly groundwater level. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 994 (2021).

Antony, A. et al. Scale formation and control in high pressure membrane water treatment systems: a review. J. Membr. Sci. 383, 1–16 (2011).

Agbasi, J. C., Abu, M. & Egbueri, J. C. Towards sustainable industrial development: modelling the quality, scaling potential and corrosivity of groundwater using GIS, Spatial statistics, soft computing and index-based methods. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-05105-3 (2024).

Langelier, W. F. The analytical control of Anti-Corrosion water treatment. J. AWWA. 28, 1500–1521 (1936).

Ryznar, J. W. A new index for determining amount of calcium carbonate scale formed by a water. J. AWWA. 36, 472–483 (1944).

Bijanvand, S., Asgharzadeh-Bonab, A., Parsaie, A. & Afaridegan, E. Enhanced prediction of discharge coefficients in harmonic plan circular weirs using advanced machine learning and ensemble techniques. Flow. Meas. Instrum. 102, 102812 (2025).

Parsaie, A. et al. Novel hybrid intelligence predictive model based on successive variational mode decomposition algorithm for monthly runoff series. J. Hydrol. 634, 131041 (2024).

Neshat, A., Shobeiri, S. & Sharafati, A. Evaluation of the ECMWF precipitation product over various regions of Iran. J. Meteorol. Res. 35, 1125–1135 (2021).

Farzad, R., Sharafati, A., Ahmadi, F. & Hosseini, S. A. Reservoir evaporation prediction with integrated development of deep neural network models and meta-heuristic algorithms (Case study: Dez Dam). Earth Sci. Inf. 18, 210 (2025).

Seyedian, S. M., Kisi, O., Parsaie, A. & Kashani, M. Improving the reliability of compound channel discharge prediction using machine learning techniques and resampling methods. Water Resour. Manag. 38, 4685–4709 (2024).

Eslamitabar, V., Ahmadi, F., Sharafati, A. & Rezaverdinejad, V. River flow simulation based on empirical mode function signals and random forest algorithm. Acta Geophys. 73, 1801–1817 (2024).

Ghasemlounia, R., Gharehbaghi, A., Ahmadi, F. & Albaji, M. Developing a novel hybrid model based on deep neural networks and discrete wavelet transform algorithm for prediction of daily air temperature. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 17, 2723–2737 (2024).

Shirvan, S. H., Pirzadeh, B., Rajaei, S. H. & Shafai Bejestan, M. Multi-approaches evaluation for prediction of discharge coefficient of porous broad-crested weirs under upstream partial blockage. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 49, 4913–4925 (2025).

Gorjizade, A. & Shahbazi, A. Analysis of spatial distribution of precipitation using hydrological modeling of watersheds (Case study: Dez dam Watershed). Earth Sci. Inf. 18, 154 (2025).

Gorjizade, A. & Moridi, A. Comparative analysis of the performance of gridded precipitation products over Iran. Water Harvest. Res. 7, 175–193 (2024).

Funding

There is no fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ali Gorjizade: simulation and coding, Abbas Parsaie: idea and writing*,

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gorjizade, A., Parsaie, A. AI-based forecasting of groundwater corrosion and scaling indices in semi-arid regions using 25-year data analysis. Sci Rep 15, 41654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25615-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25615-y