Abstract

Only a few dogs in the world are label-learners, with the ability to process and retain a vast number of object referents. Here we present data from a battery of cognitive tests that could explain why they outperform their conspecifics. In a citizen science approach, we instructed dog owners across five different countries, on how to administer a series of eight cognitive tests to their dogs. The group of label-learner dogs (N = 11) was then compared to control dogs (N = 11) that did not have that label learning ability. Our experiment demonstrates, for the first time, that the label-learner dogs’ ability might be based on measurable individual differences in three specific cognitive domains: their interest in novel objects, their targeted interest in objects and their inhibitory skills. Future research, replicating the results on a larger sample, can explore if the label-learner dogs’ outstanding cognitive skills are already present at the puppy stage or develop over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The extent to which word learning is based on cognitive abilities that are unique to humans, is a matter of continuous debate. In 2004, Kaminski and colleagues presented a Border Collie, named Rico, who was able to distinguish more than 200 objects by their labels. Rico was also able to learn the labels for new objects through fast mapping, which was formerly thought to be a uniquely human word learning principle1. Later, Chaser, a then 4-year-old Border Collie, was shown to recognize over 1000 objects by their labels2 and reports of a few more dog individuals with similar skills followed3,4. Worldwide recruitment attempts produced only a handful of these label-learner dogs, indicating that such dogs are extremely rare5. These dogs have been labelled ‘genius’ dogs6, for their ability to process and retain more object referents than was recorded for any other non-human animal1,2. The key question is what abilities enable these individuals to outperform their conspecifics5.

In general, dogs seem highly adapted to use human communication successfully7. During 30.000 years of domestication8, dogs have evolved to communicate with humans with a flexibility that cannot be found in any other species including humans’ closest living relative, the chimpanzee9,10, as well as dogs’ closest living relative, the wolf11. This is unlikely to be the result of skill acquisition during ontogeny as puppies as young as six weeks communicate effectively with humans12,13. Therefore, dogs’ skills in this domain seem to be an evolved adaptation to their special habitat, the human environment13. Dogs also use and pay particular attention to human speech. Recent research using fMRI technology has revealed that dogs distinguish between separate ‘words’ in a sentence14 and further distinguish between ‘novel’ and ‘nonsense’ words15,16. Dogs also seem to identify word boundaries for novel words17 and distinguish the language of their owner from any other language18. There is, however, no evidence for any area in the dog brain particularly adapted to “understand” humans’ speech, but rather speech is processed by the dogs’ brain like any other sounds19. Interestingly, while dogs seem good at acquiring action words (like ‘sit’ or ‘come’), learning nouns appears to be much harder20. Only a very small number of individual dogs seem to readily learn larger numbers of object referents (labels, see above), suggesting tremendous individual differences5. In the current study, we aimed to identify distinct features of the label-learner dogs’ cognition in comparison to dogs that do not show this trait. To achieve this, we administered a battery of cognitive tests to a group of label-learner dogs (N = 11) and to a group of control dogs (N = 11), matched in age, sex and breed, in a global citizen science project.

Results

Label-learner dogs and control dogs were compared in eight cognitive tests, investigating curiosity, problem solving, learning, memory, and human communication (Table 1).

To assess whether there was a meaningful underlying latent variable, we ran an exploratory factor analysis across all tests, which returned a factor that could account for 15% of the total variance of the original variables. We estimated the factor score for each dog. This factor was normally distributed and variance between groups was comparable. Crucially, a t-test revealed a significant group difference, t(19) = 2.50, p =.022, with a large effect size d = 1.15, 95%-CI: [0.17, 2.11]. The loading pattern (see Fig. S9) indicated several variables associated with learning, object interest and inhibitory control. It suggests accuracy for “Associative Learning”, more inspection of the rubber object and being tactile with the rubber object in the “Curiosity Task”, and the duration of looking at the novel object all loaded positively on the factor. In contrast, accuracy with the referential gazing cue, looking at a person during the “Persistence Task”, the frequencies of inspections and tactile interactions of the closed side during the “Inhibition Task”, as well as the latency of solving the “Inhibition task” all loaded negatively on the factor (see detailed description in the supplemental results). Please note that this factor analysis was based on unusually few observations, due to the small sample size, which can lead to problems like overfitting and limited replicability. Therefore, findings need to be interpreted with caution.

Further statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.3.2. For the analysis of the Associative Learning task and the Referential Communication task, a multilevel logistic regression using the glmer-command of the lme4 package21, with a binominal distribution, a logit-link function and Laplace approximation were conducted. Goodness-of-fit evaluation was based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and visual inspection of the data. Differences in the AIC between models were tested for significance using χ²-tests. The p-values of main and interaction effects were calculated with the mixed-command from the afex-package22 using a likelihood ratio test.

Novel object task

11 label-learner dogs (LL) and 11 control dogs (C) entered analysis

Two-sample t-tests revealed longer looking duration in label learners (MLL = 33.70 ± 5.35 SEM) compared to control dogs (MC = 14.94 ± 5.15 SEM; |t(20)| = 2.53, p =.020, d = 1.13, 95%-CI [0.17, 2.06]), as well as marginally higher frequencies of looking (MLL = 7.27 ± 1.39 SEM; MC = 4.27 ± 0.79 SEM; |t(20)| = 1.89, p =.075, d = 0.84, 95%-CI [−0.08, 1.74]). There was no group difference for the dependent variable latency to approach (|t(20)| = 0.50, p =.620).

Inhibition task

11 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We ran mixed-effects 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVAS with the within-subject factors Behavior (inspect, tactile) and Side (closed-side, open-side) and the between-subject factor Group (Label Learners, Controls) on the dependent variable Duration (in sec). However, we found no significant main effects or interactions. Further, a planned t-test on the Latency (when dogs solve the problem) did not reveal any differences between label-learners and control dogs (|t(19)| = 0.64, p =.529). Note that the latency value of one control dog is missing, because they did not solve the task in 90 s.

Persistence task

9 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We ran mixed-effects 3 × 2 ANOVAs with the within-subject factor Behavior (inspect-box, looking-at-person, tactile-box) and the between-subject factor Group (Label Learners, Controls) on the dependent variable Duration (in sec).

We observed a main effect for Behavior (F(2,36) = 6.03, p =.010, ηp2 = 0.25). Post-hoc testing of the Behavior effect revealed that although numerically dogs looked longest at the person (M = 57.7 s ± 10.2 SEM), that did not differ significantly from tactile behavior (M = 32.9 s ± 8.5 SEM, |t(19)| = 1.60, p =.127). However, there was a trend that dogs showed least engagement with the box (M = 15.5 s ± 3.2 SEM, |t(20)| = 1.80, p =.088, d = 0.41, 95%-CI [−0.06, 0.88]). Note, however, that the Duration variable has considerable outliers, which can bias the ANOVA. To address this, we repeated the ANOVA with Duration converted to rank, and replicated the Condition main effect (F(2,36) = 3.92, p =.029, ηp2 = 0.18).

Associative learning task

10 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We estimated a logistic function with the following syntax:

AccuracyTrial ~ Session × Group + (Session | Dog).

Session coded testing session from 1 to 6, Group coded label-learners vs. control dogs. We opted for a random effects structure (AIC = 1900.6, BIC = 1937.7), because the model was significantly better than a random intercept model (χ² = 10.98, p =.004).

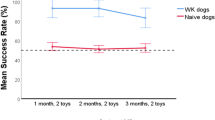

The model showed a significant effect of Session (β = 0.22 ± 0.07 SEM, χ² = 19.53, p <.001), but no main effects and interactions involving the factor Group (ps ≥ 0.318). Figure 1 shows that dogs improved on accuracy across sessions.

Overview over test results for label-learner versus control dogs. (A) Novel Object Task: Boxplot of looking duration. (B) Novel Object Task: Frequency of looking. (C) Inhibition Task: Duration of inspection and tactile interaction with the cylinder. Note that a non-linear y-axis was chosen for better visibility. (D) Inhibition Task: Latency the dog required to solve the task. (E) Persistence Task: Duration of the different behaviors: inspection of the box, tactile interaction with the box and looking at person. (F) Referential Communication: Mean accuracy in the two conditions Gazing and Pointing. (G) Memory Task: Number of dogs who solved the task correctly after 30 min, 2 h and 24 h. (H) Curiosity Task: Duration of behaviors inspection and tactile interaction with objects of different texture (fabric and rubber). (I) Associative Learning Task: Mean accuracy per session. The lines depict the trajectories of each individual dog. All durations and latencies are displayed in seconds.

Referential communication task

10 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We estimated a logistic function with the following syntax:

AccuracyTrial ~ Condition × Group + (Condition | Dog).

Condition coded either Pointing or Gazing of the owner, Group coded label-learners vs. control dogs. We opted for a random effects structure (AIC = 550.3, BIC = 579.7), because the model was significantly better than a random intercept model (χ² = 6.13, p =.047).

The model showed a significant effect of Condition (χ² = 12.32, p <.001), with performance being better for Pointing (MAccuracy = 0.83 ± 0.07 SEM) than for Gazing (MAccuracy = 0.65 ± 0.07 SEM). However, there were no main effects and interactions involving the factor Group (ps ≥ 0.255). Planned t-tests on the aggregated accuracy data against chance level of 0.5 revealed that both in the gazing (|t(20)| = 9.33, p <.001, d = 2.09, 95%-CI [1.30, 2.85]) and in the pointing condition (|t(20)| = 4.46, p <.001, d = 1.00, 95%-CI [0.45, 1.53]), dogs performed well above chance.

Memory task

9 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We first calculated the total number of correct trials per dog (ranging from 0 to 3, see Table S3). A Fisher test revealed a significant relationship between Group (label learner vs. test) and the distribution of correct trials (p =.042). As Table S3 shows, control dogs performed overall better. Subsequently, we ran separate Fisher tests for each delay condition (30 min, 2 h, 24 h) comparing correct and incorrect responses between Group (see Table S4 for descriptive data). However, although numerically control dogs always seemed to outperform label learners, we did not observe a significant effect for 30 min (p =.362) or 2 h (p =.653), and only a trend for 24 h (p =.070). Note that the data of one control dog is missing in the 24 h condition.

Curiosity task

11 label-learner dogs and 11 control dogs entered analysis

We first ran 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVAs with the within-subject factors Behavior (inspect, tactile) and Object Texture (Fabric, Rubber) and Object Shape (long, round) on the dependent variable Duration (in sec). For Duration, we found no main effects or interaction involving the factor Object Shape. We therefore aggregated across this factor and subsequently ran a mixed effects ANOVA where we added the between-subject factor Group (Label Learners, Controls). First, we found a main effect for Behavior (F(1,20) = 15.60, p =.001, ηp2 = 0.44), because the dogs showed a lot more tactile behavior (16.7 s ± 3.6 SEM) than engagement (3.9 s ± 1.1 SEM). Second, we found a main effect for Object Texture (F(1,20) = 7.45, p =.013, ηp2 = 0.27), because dogs interacted more with the rubber (15.6 s ± 3.9 SEM) than with the fabric object (5.0 s ± 1.7 SEM). Those main effects were qualified by an interaction (F(1,20) = 5.23, p =.033, ηp2 = 0.21), because the difference between fabric and rubber was more pronounced for tactile than for engagement behavior (see Fig. 1). Finally, we found a trend for an interaction of Group and Object Texture (F(1,20) = 4.04, p =.058, ηp2 = 0.17). Numerically, it seemed as if label-learner dogs showed a stronger preference for rubber over fabric than control dogs, but respective post-hoc t-tests were non-significant (p ≥.111).

Note, however, that the Duration variable has considerable outliers, which can bias the ANOVA. To address this, we repeated the ANOVA with Duration converted to rank. We replicated the main effects of Behavior (F(1,20) = 6.75, p =.017, ηp2 = 0.25) and Object Texture (F(1,20) = 12.28, p =.002, ηp2 = 0.38). However, this time we found a significant interaction of Group and Object Texture (F(1,20) = 14.98, p =.001, ηp2 = 0.43), indicating that label learner dogs preferred rubber objects compared to control dogs (|t(20)| = 2.57, p =.018, d = 1.15, 95%-CI [0.19, 2.08]), while there was no difference for the fabric object (|t(20)| = 1.44, p =.166, d = 0.64, 95%-CI [−0.26, 1.53]). See Fig. 1 for an overview of all data.

Discussion

Our experiment demonstrates for the first time that the label-learner dogs’ ability to retain such a vast number of object-referents is linked to measurable individual differences in three specific cognitive domains: First, the label-learners were significantly more interested in novel objects. These results, if replicated by future studies, might indicate a deeply rooted object-related curiosity in the label-learner dogs but not the control dogs. This is supported by evidence indicating that curiosity is a core personality trait in dogs, characterized by significant individual differences23,24.

Alternatively, one could argue that this could be a direct result of the label-learners more frequent engagement in object-related games in their daily life compared to the control dogs. However, no human playmate was present during the “Novel Object Task” suggesting that the dogs’ focus on the novel objects could be driven by internal factors, such as heightened curiosity, rather than learnt and socially directed behaviors. In human children, curiosity is a relatively stable personality trait25, and there seem to be significant individual differences but also breed differences when it comes to curiosity or information seeking around objects in children and some non-human animal species including dogs28. Thus, it is possible that the label-learners are on average more curious than other dogs.

Second, we further isolated a factor which significantly distinguishes the label-learner dogs from other, regular dogs and which is best explained as a targeted interest for objects. This interestingly corresponds with recent research, which suggests a link between ‘interest in objects’ and word learning in children. Children’s particular interests in objects and object categories guide their object category specific vocabulary as well as their retention of words in specific areas29,30. Thus, their interest in objects might enable the label-learner dogs to learn the labels of these objects. In a study based on questionnaires given to the dogs’ owners, Fugazza et al. (2022) compared the owners’ perceived personality traits of label-learner dogs to ‘typical’ dogs. While no differences were found in fearfulness or aggression, and ‘object interest’ was insufficient as an explanatory trait for label-learning, the label-learner dogs scored significantly higher in activity/excitability and responsiveness to training. Specifically, the subjects displayed a significantly higher level of playfulness than is typical of the canine species. This finding is consistent with the results of the present study31.

Third, the label-learners showed better inhibitory skills. Inhibitory control is an important cognitive skill that prevents impulsive reactions as it requires the individual to exert control to behave or choose correctly32. Thus, inhibitory control might be the essential cognitive building block underlying the label-learners ‘genius’ ability, as subjects must inhibit their preference for certain features of the objects they fetch (see also33). Interestingly, human-focused behaviors, like e.g. accuracy with the referential gazing cue and looking at a person during the “Persistence Task, were found to be associated with the control group rather than the label-learner group. This suggests that independence, or a stronger focus on environmental stimuli, may be a contributing factor to the label-learner dogs’ success.

One potential limitation of our study is the small sample size. However, this is an inherent challenge given the rarity of label-learner dogs, as evidenced by the fact that our participants came from five different countries. This geographic diversity underscores just how uncommon these dogs are. Despite the limited sample size, the emergence of significant group differences is particularly noteworthy and may indicate that these effects are both robust and meaningful.

Interestingly, the combination of traits also resembles traits that are subtypes of autistic symptoms in humans: “attention to detail” and “social interaction”34. Neurotypical individuals with autistic traits, as measured by the Autism Quotient, AQ35, show increased attention to detail and decreased motivation for social interaction, resembling the profile we found in the label-learner dog individuals. In a recent study, Yuan et al. (2025) investigated atypical face processing in dogs with a Shank3 mutation. They proposed that these dogs have face recognition deficits similar to those seen in humans with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)36. It would be very interesting to see if the label learning dogs in the current study are carriers of the Shank3 mutation and to use cognitive test batteries, like the one we developed, to explore the presence of autistic traits in dogs empirically37.

Taken together, our study suggests, for the first time, that cognitive abilities related to label learning are associated with measurable individual differences, and future research should explore whether these traits are part of the make-up of some dog individuals from the puppy stage, or whether they develop over time and can be influenced by training. This would open avenues for selecting specific dog individuals with these traits, as e.g. service dogs, who could then be taught to retrieve a large number of household objects by name.

Materials and methods

The study animals were all normal family dogs, living with their owners and recruited specifically for the purpose of this study. Because the label-learner dogs are so rare and had to be recruited globally (USA, UK, Germany, Netherlands and Switzerland), we conducted this study as a ‘citizen-science’ project, where the experimenter was the owner of the dog. Dogs and owners of the label-learner group were recruited through international advertisements for the study and through recruitment videos. These videos were translated into German, French, Mandarin as well as other languages to reach as many dog owners as possible. Following the advertisements, 86 owners initially applied and indicated for their dog to be a label-learner. These 86 owners were pre-screened to identify if what their dog was doing really fit the criteria for label-learner dogs (e.g. being able to fetch correct objects based on their label with their owner out of sight). Out of those, 34 owners were then further invited for their dog to participate in the pre-test to verify that their dogs can distinguish objects by their labels (based on Kaminski et al. 2004). Fifteen dogs passed that pre-test successfully (see more detailed description below and in the supplemental information). Due to loss of interest or contact, four participants had to be excluded resulting in a total label-learner group size of 11 owners and their dogs.

Dogs and owners of the control group were either recruited from the dog database of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology (MPI GEA) or via social media. This resulted in a total control group size of eleven dogs and their owners (see supplemental information, table S1).

The study was ethically approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB, No522A) at the University of Portsmouth. The animal research complies with the “Guidelines for the Treatment of Animals in Behavioral Research and Teaching” of the Association for the Study of Animal Behavior (ASAB) as well as the guidelines of Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE). The owners of the dogs were instructed to feed their dogs according to their normal daily routine and not food deprive them in any way. Water was available to the dogs ad libitum. Owners were further instructed to ensure that their dogs receive regular breaks and to stop observations if their dogs showed any sign of stress.

In a pre-test, the label-learner dogs were tested for their ability to reliably distinguish objects (dog’s or children’s toys) by their label. For the pretest, dogs had to fetch the correct object out of several objects and without having visual access to their owner (or any other person) while making the choice. Following the original procedures from Kaminski et al. (2004), objects were randomly assigned to sets of 10. The owner then requested their dog to bring two randomly chosen items (one after the other) from the adjacent room. While the dogs searched for the requested item, they could not see their owner and vice versa. Only dogs that passed the pre-test and with a vocabulary of over 20 object referents were categorized as label-learners. Every trial was video recorded by the owners and later analyzed from video. We measured if dogs fetched the correct or incorrect object (see supplemental information).

Subsequently, dogs in the label-learner and control group were presented with a test battery of eight different tasks (Table 1) all based on previously conducted research with non-human animals. More detailed description of the procedures of each task can be found in the supplemental materials.

-

1.

“Novel object task”38: a blinking, noisy object, novel to the dogs, was placed in the middle of the room with no human around for 1 min. This was to see how dogs would interact with a strange object.

-

2.

“Inhibition task”13: For this task a transparent cylinder was placed on the floor, which was accessible to the dogs from one end but not the other. A reward was placed inside the cylinder and presented to the dogs first with the open end easily accessible end directed at them for four consecutive trials. After that, the cylinder was turned around and now the closed end was directed at the dogs. We measured how long it would take the dogs to get the reward and how good they were in inhibiting their learned response of approaching the cylinder from the end directed at them in favor of moving around to the other end.

-

3.

“Persistence task”11: A reward was placed in a plastic box which was placed on the ground. For four trials, the box was loosely covered with a lid, which the dogs could easily remove to reach the food. In the fifth trial, the lid was then fixed such that the dogs could no longer open it. This was to see to what extent the dogs would persist in their attempt to open the box or look back at their owner.

-

4.

“Associative learning task”39,40: the dogs’ owners placed three containers of different shapes and colors in front of the dog, with food always being hidden under the same color (and shape) container, despite containers changing location between trials. We measured accuracy of choice and measured how many trials dogs needed to associate the specific container with food.

-

5.

“Referential communication task”41: The owners hid food in one of two containers, out of sight of the dog, and then communicated the location of the food by using a pointing or gazing cue. We measured the number of times that the dog followed the cue and found the food.

-

6.

“Memory task”42: Here the owners presented the dogs with three identical cups set up in a row. We placed a reward under one of three cups in full view of the dogs. We then measured how successful the dogs were at recalling the location of the reward after 30 min, 2 h, and 24 h, respectively.

-

7.

“Sound discrimination task”43: Owners waited for a moment when their dog was laying down with their head resting on the ground. The owner then played back pre-prepared recordings of the same sentence, spoken in the owner’s main language, with the dog’s name embedded. Depending on the condition, the spelling of the dog’s name varied with either a modified consonant or vowel. This was compared to a control condition in which the dogs unaltered name was used. We measured the dogs’ responses (head or ear movement) upon hearing the recording.

-

8.

“Curiosity task”44: To see if the dogs were generally interested in new objects as well as discriminate objects based on specific features, we presented them with two sets of two toys which differed in texture and form that were all new to the dogs. The toys were placed in a random order in a line on the ground and the dogs were then led into the room and left by themselves with the toys for 3 min. We coded if and how dogs interacted with the toys.

For each task we coded a series of behavioral measures like frequency and duration of ‘looking behavior’, ‘approach behavior’ etc. (see Table 2 and a more detailed description of the procedures and a detailed list of all coded behaviors in the supplemental information).

We systematically analyzed if there were any differences between the label-learner and the control dogs in how they behaved in the different tasks. Apart from the “Sound Discrimination Task”, all other tests yielded data that could be analyzed (see Fig. 1). All trials were video recorded and coded from video by the research team and for reliability purposes, a subset of 27% of all videos were coded by a second person who was blind to the study goal and hypothesis (see Table 2 and supplemental information for more details).

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Kaminski, J., Call, J. & Fischer, J. Word learning in a domestic dog: evidence for fast mapping. Science 304, 1682–1683 (2004).

Pilley, J. W. & Reid, A. K. Border collie comprehends object names as verbal referents. Behav. Processes. 86, 184–195 (2011).

Griebel, U. & Oller, D. K. Vocabulary learning in a Yorkshire terrier: slow mapping of spoken words. PLOs One. 7, e30182 (2012).

Fugazza, C., Dror, S., Sommese, A., Temesi, A. & Miklósi, Á. Word learning dogs (Canis familiaris) provide an animal model for studying exceptional performance. Sci. Rep. 11, 14070 (2021).

Bräuer, J. & Kaminski, J. Communication between dogs and humans. In What Dogs Know 95–118 (Springer International Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89533-4_7.

Pilley, J. W. & Hinzmann, H. Chaser: Unlocking the Genius of the Dog who Knows 1000 Words (Simon and Schuster, 2014).

Hare, B., Brown, M., Williamson, C. & Tomasello, M. The domestication of social cognition in dogs. Science 298, 1634–1636 (2002).

Thalmann, O. et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient Canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science 342, 871–874 (2013).

Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Primate Cognition: Volume 1: Social Cognition (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Kirchhofer, K. C., Zimmermann, F., Kaminski, J. & Tomasello, M. Dogs (Canis familiaris), but not chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), understand imperative pointing. PloS One. 7, e30913 (2012).

Miklosi, A. et al. A simple reason for a big difference: wolves do not look back at Humans, but dogs do. Curr. Biol. 13, 763–766 (2003).

Riedel, J., Schumann, K., Kaminski, J., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. The early ontogeny of human–dog communication. Anim. Behav. 75, 1003–1014 (2008).

Bray, E. E. et al. Early-emerging and highly heritable sensitivity to human communication in dogs. Curr Biol. 31 (14), 3132–3136 (2021).

Fukuzawa, M., Mills, D. S. & Cooper, J. J. More than just a word: non-semantic command variables affect obedience in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 91, 129–141 (2005).

Andics, A. et al. Neural mechanisms for lexical processing in dogs. Science 353, 1030–1032 (2016).

Gábor, A. et al. Multilevel fMRI adaptation for spoken word processing in the awake dog brain. Sci. Rep. 10, 11968 (2020).

Boros, M. et al. Neural processes underlying statistical learning for speech segmentation in dogs. Curr. Biol. 31, 5512–5521 (2021).

Cuaya, L. V., Hernández-Pérez, R., Boros, M., Deme, A. & Andics, A. Speech naturalness detection and Language representation in the dog brain. NeuroImage 248, 118811 (2022).

Andics, A., Gácsi, M., Faragó, T., Kis, A. & Miklósi, Á. Voice-sensitive regions in the dog and human brain are revealed by comparative fMRI. Curr. Biol. 24, 574–578 (2014).

Ramos, D. & Mills, D. S. Limitations in the learning of verbal content by dogs during the training of OBJECT and ACTION commands. J. Vet. Behav. 31, 92–99 (2019).

Bates, D. M. lme4: Mixed-effects modeling with R. (2010).

Singmann, H. et al. Package ‘afex’. URL Httpafex Singmann Sci. Httpsgithub Comsingmannafex. (2015).

Sundman, A., Johnsson, M., Wright, D. & Jensen, P. Similar recent selection criteria associated with different behavioural effects in two dog breeds. Genes Brain Behav. 15, 750–756 (2016).

Svartberg, K., Tapper, I., Temrin, H., Radesäter, T. & Thorman, S. Consistency of personality traits in dogs. Anim. Behav. 69, 283–291 (2005).

Ainley, M. Curiosity and interest: emergence and divergence. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 31, 789–806 (2019).

Asp, H. E., Fikse, W. F., Nilsson, K. & Strandberg, E. Breed differences in everyday behaviour of dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 169, 69–77 (2015).

Henderson, B. & Moore, S. G. Children’s responses to objects differing in novelty in relation to level of curiosity and adult behavior. Child Dev. 457–465, June (1980).

Massen, J. J. M., Antonides, A., Arnold, A. K., Bionda, T. & Koski, S. E. A behavioral view on chimpanzee personality: exploration tendency, persistence, boldness, and tool-orientation measured with group experiments. Am. J. Primatol. 75, 947–958 (2013).

Ackermann, L. et al. The role of interest in young children’s retention of words. Infant Child. Dev. 33, e2466 (2024).

Madhavan, R. & Mani, N. (submitted) Children’s individual interests are sustained across development and predict later vocabulary development.

Fugazza, C. et al. A comparison of personality traits of gifted word learner and typical border collies. Anim. Cogn. 25, 1645–1652 (2022).

Gnanadesikan, G. E., Hare, B., Snyder-Mackler, N. & MacLean, E. L. Estimating the heritability of cognitive traits across dog breeds reveals highly heritable inhibitory control and communication factors. Anim. Cogn. 23, 953–964 (2020).

Fugazza, C. et al. Shape and texture biases in dogs’ generalization of trained objects. Sci. Rep. 14, 28077 (2024).

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M., Cath, D. C. & Boomsma, D. I. Factor Structure, reliability and criterion validity of the Autism-Spectrum quotient (AQ): A study in Dutch population and patient groups. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 38, 1555–1566 (2008).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J. & Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, Malesand females, scientists and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31, 5–17 (2001).

Yuan, S. et al. Autism-like atypical face processing in Shank3 mutant dogs. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu3793 (2025).

Topál, J., Román, V. & Turcsán, B. The dog (Canis familiaris) as a translational model of autism: it is high time we move from promise to reality. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 10, e1495 (2019).

Herrmann, E., Misch, A., Hernandez-Lloreda, V. & Tomasello, M. Uniquely human self‐control begins at school age. Dev. Sci. 18, 979–993 (2015).

Call, J. Inferences by exclusion in the great apes: the effect of age and species. Anim. Cogn. 9, 393–403 (2006).

Hanus, D. & Call, J. Chimpanzee problem-solving: contrasting the use of causal and arbitrary cues. Anim. Cogn. 14, 871–878 (2011).

Bräuer, J., Kaminski, J., Riedel, J., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Making inferences about the location of hidden food: social dog, causal ape. J. Comp. Psychol. 120, 38 (2006).

Martin-Ordas, G. & Call, J. Memory processing in great apes: the effect of time and sleep. Biol. Lett. 7, 829–832 (2011).

McReynolds, L. V. Operant conditioning for investigating speech sound discrimination in aphasic children. J. Speech Hear. Res. 9, 519–528 (1966).

Horst, J. S. et al. Toddlers can adaptively change how they categorize: same objects, same session, two different categorical distinctions. Dev. Sci. 12, 96–105 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank first and foremost the dog owners who participated in this study. Without their tremendous effort and support, this research would not have been possible. We also want to thank Luisa Motz, Sarah Achtmann, Paolina Kaube, Omar Edrees, Stephanie Brietz, Annabell Diem and Anne Riefling for help with piloting the procedures. We further thank Marine Joly and Lea Ulverich for reviewing the statistical scripts. We thank Sabine Grimme for help with reliability coding of the video material and Paul Morris for proofreading the manuscript.A very special thank you to Michelle O’Reilly and Hans Sell for producing and promoting our recruitment video, and for designing the webpage for dog owners.

Funding

This project was partly funded by internal university funding given to JK. JB was supported by the DFG grant BR 3601/7–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: JK, JBMethodology: JK, JB, FKData Coding: SC, JK, JB, FKData analysis: ChN, JK, JBData visualisation: ChNWriting – original draft: JK, JBWriting – review & editing: JK, JB, ChN, FK, SC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaminski, J., Capitain, S., Kühr, F. et al. What makes a dog a label-learner: individual cognitive differences underlying label-learning abilities in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Sci Rep 15, 41616 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25646-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25646-5