Abstract

Postoperative urinary retention (POUR) is one of the most common problems following pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery, the risk factors associated with its occurrence have been reported inconsistently across studies. We aim to synthesize the risk factors of urinary retention after POP surgery using a meta-analysis approach. Databases of the PubMed, The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, CBM, CNKI, WanFang and VIP were systematically searched through December 31, 2024. A total of 2065 studies were identified, 19 of which were included in this meta-analysis and 14 risk factors were analyzed. older age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [1.01, 1.06], P = 0.01), age ≥ 60 years (OR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.05, 1.59], P = 0.01) and being menopausal (OR = 1.44, 95% CI [1.10, 1.88], P = 0.01), severe cystocele (OR = 3.15, 95% CI [1.92, 5.16], P < 0.01), preoperative post-void residual (PVR) > 200 mL(OR = 2.34, 95% CI [1.46, 3.76], P < 0.01), procedure time(OR = 1.11, 95% CI[1.04, 1.18], P < 0.01), anterior repair (OR = 1.97, 95% CI [1.55, 2.51], P < 0.01), anti-incontinence procedures (OR = 2.15, 95% CI [1.40, 3.28], P < 0.01), and hysterectomy (OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.13, 1.75], P < 0.01) were associated with an increased risk of POUR. These findings aid in the preoperative identification of patients at high risk for POUR, enabling optimization of preoperative education strategies, guiding surgical decision-making and POUR prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

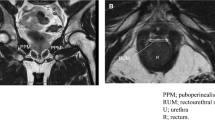

POP is a common health issue among adult women and is caused by weakened or damaged pelvic support structures that result in the descent of pelvic organs (such as the bladder, uterus, and rectum) from their normal anatomical positions. This condition often leads to bothersome symptoms such as vaginal bulging, urinary and bowel difficulties, and sexual dysfunction, significantly impacting the quality of life for women and potentially leading to psychological issues such as anxiety and depression1,2,3. The prevalence of POP has been reported to range from 3 to 50%4,5,6. As the global ageing trend increases, this issue may become even more serious, with an anticipated 48.2% increase in women undergoing surgery for POP by 2050 compared with 20107.

Surgery is one of the primary treatment options for pelvic organ prolapse, with a subjective improvement rate of 81.5% among patients8. However, POUR is a common complication following the procedure. Currently, there are no definitive standards for the assessment methods and definitions of POUR. The assessment methods include retrograde voiding trials or spontaneous voiding trials combined with PVR ultrasound or catheterization9,10. There is a greater preference for using retrograde voiding trials internationally because they tends to have higher success rates and lower catheter usage upon discharge than spontaneous voiding trials11. The definition of POUR relies primarily on PVR; however, specific cut-off values vary among studies, with most studies considering PVR > 100 mL or PVR > 150 mL as standards9,10,12,13. Some studies also consider maximum bladder capacity, suggesting that this approach may be more scientific14,15,16. POUR can also be classified as acute or delayed17, with this study focusing on acute urinary retention occurring after surgery. Due to variations in specific surgical types and definitions of POUR, the incidence of POUR following POP surgery ranges from 3.5% to 48.6%12,13,14,15,18. Severe urinary retention can lead to urinary tract infections and renal function impairment, thereby affecting patient recovery, prolonging hospitalization, and increasing medical costs18,19,20. Recent research showed that the average hospitalization cost for patients who experienced POUR was 100,630 US dollars, significantly higher than that for patients who did not experience POUR, with postdischarge costs related to POUR events reaching as high as 9,418 US dollars20.

A comprehensive understanding of the high-risk factors for POUR during the perioperative period, along with the identification of high-risk populations, can facilitate the implementation of preventive intervention strategies, optimize clinical pathways, and improve patient outcomes while reducing economic costs. Although numerous studies12,13,14,15,18 have explored risk factors for urinary retention following POP surgery—such as age, diabetes status, preoperative urodynamic parameters, anaesthesia type, and surgical approach—these studies have yielded inconsistent results and lack systematic comprehensive analyses. Therefore, this study aims to integrate existing research data through meta-analysis and systematically evaluate the risk factors for urinary retention following POP surgery, thereby providing theoretical support for individualized treatment, reducing the incidence of POUR, and improving patients’ surgical outcomes and quality of life.

Methods

This meta-analysis is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement21 and was registered at the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols(INPLASY number:202310088).

Literature search strategy

We conducted a systematic search for relevant studies published through September 13, 2023 and updated the search until December 31, 2024, including four international databases and four Chinese databases: the PubMed, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, Chinese Biological Medicine Database (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database (CNKI), WanFang Digital Periodicals Database (WFDP), and the VIP Database. We used the following as key words: ‘urinary retention’, ‘pelvic organ prolapse’ ‘pelvic floor reconstructive surgery’, and their synonyms and hyponyms. All search terms were subject search and non-subject search terms. The search strategy is presented in Supplementary file 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

(1)

Types of studies

All Chinese and English cohort studies, case‒control studies and cross-sectional studies were included.

-

(2)

Types of participants

The subjects were patients with clinically diagnosed pelvic organ prolapse—involving the anterior, apical, or posterior compartments—who needed pelvic floor reconstruction surgery, with or without concomitant anti-incontinence procedures. Patients with preoperative urinary retention, urinary tract infection, bladder injury, or difficult micturition were excluded.

-

(3)

Types of outcome

The outcome index was acute postoperative urinary retention, irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used.

Exclusion criteria:

(1) Repeatedly published studies, (2) studies for which the full text could not be obtained, and (3) studies with incomplete data or obvious errors were excluded.

Literature screening and data extraction

Literature screening and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers (Linlin Zhou and Shuang Hu) according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria; discrepancies were resolved in a consensus meeting, or if agreement could not be reached, they were resolved by referral to a third researcher (Ling Dai). The extracted data included the first author, publication year, study design, number of patients, surgical procedure undertaken, risk factors examined, definition of POUR, effect size odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI). If neither the OR nor the 95% CI was reported, we will extracted the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the occurrence frequency and sample size for the metric. The baseline characteristics, including the risk factors, were tabulated in a spreadsheet to facilitate subsequent pooling and comparative analysis of the results.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (Linlin Zhou and Shuang Hu) independently evaluated the quality of the studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the risk of bias of cohort studies and case‒control studies. The NOS scale consists of 8 items with a total score of 9, and a score of 4 or below is considered low quality, a score of 5 to 6 is deemed moderate quality, and a score of 7 or above is considered high quality22. The quality evaluation criteria of cross-sectional studies recommended by American health care quality and research institutions (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ) were adopted to evaluate the quality of the included cross-sectional studies, which included 11 items with a total score of 11. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion with the author (Ling Dai) until consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Stata 17.0 was used to conduct the meta-analysis, with the statistical effect size being the OR and 95% CI. For studies that did not report ORs and 95% CIs, we used the method described by Friedrich et al.23 to convert the means and SDs into ORs and 95% CIs. Additionally, we employed Review Manager 5.3 to convert occurrence frequencies and sample sizes into ORs and 95% CIs. All of these conversions were considered the results of univariate analysis. If an indicator included more than two results for both univariate and multivariate analyses, a subgroup analysis was conducted. Heterogeneity among the included results was assessed using the χ2 test and I2 statistic. I2 ≤ 25% indicates low heterogeneity between studies, I2 > 25% and I2 ≤ 50% indicate moderate heterogeneity, and I2 > 50% indicates high heterogeneity. If P ≥ 0.10 and I2 ≤ 50%, a fixed effects model was applied for meta-analysis; if P < 0.10 and/or I2 > 50%, the source of heterogeneity was further analysed, and a random effects model was used for meta-analysis after the influence of obvious clinical heterogeneity was excluded. A sensitivity analysis of all the outcomes was performed to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis findings in this study. For exposure factors with ≥ 10 references, publication bias was analysed using a funnel plot and Egger’s test at a significance level α = 0.05.

Certainty of evidence

We (Linlin Zhou and Shuang Hu) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for the relevant outcomes using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) framework24. Following GRADE guidance, evidence from observational studies started with an initial rating of 'low certainty.' This rating was then systematically examined for potential factors that would warrant downgrading or upgrading, ultimately classifying the evidence into one of four grades: high, moderate, low, or very low. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third author (Ling Dai).

Results

Search results

As of September 13, 2023, we initially retrieved 1,909 articles and conducted supplementary searches until December 31, 2024, resulting in an additional 156 articles, for a total of 2,065 articles. After 409 duplicate publications were excluded and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, a final total of 19 articles were included. The literature screening process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Included studies and characteristics

A total of 6,520 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 1900 had urinary retention. All patients underwent pelvic surgery due to POP with or without SUI, including mesh repair, SacralColpopexy, and vaginal hysterectomy. Fourteen studies reported the time of catheter removal after surgery, which was mostly one or two days after surgery. Fourteen factors were investigated in two or more manuscripts and were therefore suitable for meta-analysis: age, body mass index (BMI), menopausal status, diabetes status, higher grade of cystocele, prolapse stage ≥ Ⅲ, preoperative PVR, intraspinal anaesthesia, estimated blood loss (EBL), procedure time, hysterectomy, anterior repair, anti-incontinence procedure, and sacrospinous fixation. A summary of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Methodological quality

Among the 19 included studies, 125 was a case‒control study, and 1812,13,14,15,18,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 were cohort studies. The NOS was used to assess the quality of cohort studies and the case–control study. Fourteen studies12,14,15,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,38 were defined as high quality, and five studies13,18,35,36,37 were deemed to be of fair quality. The included studies scored well on the selection of study populations and measurement of exposure and outcomes; however, some studies failed to score well in terms of the accessibility of observational indicators and comparability between groups (Table 1).

Outcomes of the meta-analysis

General patient conditions

Eleven studies described the relationships between age, BMI, and POUR. Given the different types of data, a meta-analysis was conducted. With respect to the categorical variables, those aged > 62.4 years from the study by Bekos et al.36 were classified into the ≥ 60 years group, while those with a BMI within a margin of 1 were classified as having a BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2. The results indicated that older age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [1.01, 1.06], P = 0.01) and age ≥ 60 years (OR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.05, 1.59], P = 0.01) were related to an increased risk of POUR after POP surgery, while a greater BMI (OR = 0.99, 95% CI [0.97, 1.00], P = 0.16) and a BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 (OR = 0.79, 95% CI [0.59, 1.07], P = 0.13) were not associated with POUR. The combined results from four studies15,18,30,38 suggested that menopausal status is a risk factor for POUR after POP surgery (OR = 1.44, 95% CI [1.10, 1.88], P = 0.01) (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Disease-related factors

The results from nine studies12,13,14,18,30,32,33,35,36 revealed that diabetes is not related to POUR following POP surgery (OR = 1.33, 95% CI [0.99, 1.79], P = 0.06). Pooled results from five studies12,13,15,25,36 revealed that a prolapse stage ≥ Ⅲ did not increase the risk of POUR (OR = 1.82, 95% CI [0.78, 4.21], P = 0.16). However, analyses of only three studies14,30,37 revealed that severe cystocele significantly increased the risk of POUR in patients with POP (OR = 3.15, 95% CI [1.92, 5.16], P < 0.01). The pooled results of two studies18,38 indicated that a PVR > 200 mL is a significant risk factor for POUR (OR = 2.34, 95% CI [1.46, 3.76], P < 0.01) (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Surgery-related factors

A pool of five studies14,15,30,31,38 revealed that spinal anaesthesia is not associated with an increased risk of POUR following POP surgery (OR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.57, 1.13], P = 0.20). Eight studies12,14,15,33,34,35,36,38 analysed the relationship between EBL and POUR. The meta-analysis revealed no association between EBL > 100 mL (OR = 1.05, 95% CI [0.77, 1.44], P = 0.74) or higher EBL (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.99, 1.07], P = 0.13) and POUR. The summarized results from four studies12,15,26,30 suggested that longer procedure times increase the risk of POUR (OR = 1.11, 95% CI [1.04, 1.18], P < 0.01) (Fig. 4, Table 2).

Surgical approach factors

Seven studies14,15,29,30,35,36,37 described the relationship between anterior repair and POUR after POP surgery and revealed that anterior repair is a risk factor for POUR (OR = 1.97, 95% CI [1.55, 2.51], P < 0.01). The overall findings of eleven studies12,13,15,18,26,29,32,34,35,37,38 revealed that anti-incontinence procedures significantly increased the risk of POUR (OR = 2.15, 95% CI [1.40, 3.28], P < 0.01). Pooled results from nine studies12,13,25,26,30,33,35,36,37 demonstrated that hysterectomy is statistically associated with a higher risk of POUR (OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.13, 1.75], P < 0.01). In contrast, the combined results from only three studies25,29,37 revealed no association between sacrospinous fixation and POUR (OR = 1.37, 95% CI [0.86, 2.18], P = 0.19) (Fig. 5, Table 2).

Heterogeneity testing and subgroup analysis

The studies on the nine outcome indicators exhibited low heterogeneity, while another three indicators indicated moderate heterogeneity, and there was significantly high heterogeneity among the studies for five outcome indicators (Table 2). For the five indicators with significant heterogeneity, we further explored the sources of this heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted for the indicators of older age and anti-incontinence procedure, based on whether the OR had been adjusted. The results revealed that the heterogeneity in the multivariate results group was significantly reduced, while that in the univariate outcome group remained relatively high (I2 > 50%).

For the remaining three indicators, we noted that only for the indicator of prolapse ≥ stage Ⅲ did one result25 come from the multivariate analysis of a case‒control study. The other studies for these indicators were based on univariate analyses of cohort studies. Additionally, there were certain differences in the definitions of urinary retention and catheter removal timing among the studies, but due to the dispersed or ambiguous category data, further subgroup analyses were not conducted.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We assessed the stability of each outcome indicator’s results through a sequential removal method. The results indicated that the findings for the five outcome indicators—age ≥ 60 years, menopausal status, prolapse ≥ stage Ⅲ, hysterectomy, and procedure time—lack stability, while the meta-analysis results for the other indicators were relatively stable. The studies by Schmidt et al.26 affected the stability of the results for the indicator age ≥ 60 years, with the stability of the menopausal status indicator being influenced by the research conducted by Anglim et al.15. Furthermore, one study12 impacted the stability of the results for prolapse ≥ stage Ⅲ, one study26 affected the stability of the hysterectomy indicator, and three studies12,15,26 influenced the stability of the procedure time indicator. Removing these studies resulted in the corresponding indicators yielding results contrary to the original findings.

A funnel plot was created for the risk factors for anti-incontinence procedures, with 11 studies included, and Egger’s test was employed to analyse publication bias. Although the funnel plot appears to be somewhat asymmetrical (Fig. 6), the p value from Egger’s test is 0.56, indicating a low likelihood of publication bias in this study.

GRADE certainty of evidence

In our study, two outcomes (severe cystocele, preoperative PVR > 200 ml) were graded as moderate certainty, five outcomes (age ≥ 60 y, menopausal, anterior repair, anti-incontinence procedure, hysterectomy) were graded as low certainty, and the rest as very low certainty. All rationales for upgrading or downgrading the evidence are provided to ensure transparency (Table 3)in the supplementary materials.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to comprehensively analyse the risk factors for postoperative urinary retention following pelvic floor reconstruction. This meta-analysis revealed that older age, age ≥ 60 years, menopausal status, higher grade of cystocele, preoperative PVR > 200 mL, longer surgical time, anterior repair, anti-incontinence surgery, and hysterectomy increased the risk for POUR following POP surgery.

Increased age has been reported to significantly increase the risk of POUR39, which is similar to our findings. However, age could be widely distributed. Therefore, we further analysed studies that reported a relationship between age ≥ 60 years and POUR. The results indicated that age ≥ 60 years significantly increased the risk of POUR after POP surgery, with an OR of 1.29, which was greater than the OR of 1.03 for older patients. Additionally, we found that menopausal status is a risk factor for POUR, likely due to the decline in the function of pelvic floor muscles, ligaments, and nerves with increasing age and the onset of menopause, which is particularly pronounced in the elderly stage. A study by Alas et al.14 suggested that women under 55 years old have a higher likelihood of urinary retention, possibly because younger patients are more sensitive to pain and pelvic muscle tension during urination. It seems that such a situation exists in clinical practice, but more research is needed to confirm this finding. A study by Barr et al.40 revealed that a lower BMI is associated with POUR following anti-incontinence surgery. Our study did not find a correlation between BMI and POUR, possibly due to inconsistencies in the types of BMI data recorded in the included studies, which weakened the combined effect. Future research could further explore risk stratification analyses based on age and BMI.

Severe cystocele was the most significant risk factor for POUR, with a high OR of 3.15 in our analysis. For these patients, the degree of bladder neck elevation during surgery may be significant and can lead to urinary obstruction. Additionally, oedema of the surrounding urethral tissue is expected to be more obvious, thereby increasing the risk of POUR30. This could explain the increased risk of POUR in patients who underwent anterior repair. Research on prolapse stage ≥ Ⅲ yielded nonsignificant results, potentially due to a lack of clear classification of pelvic organ prolapse, because theoretically, prolapse in the middle and posterior pelvis has less impact on the urethra and bladder during surgery. PVR refers to the volume of urine remaining in the bladder after voiding; a consistently high PVR typically indicates increased bladder outlet resistance and/or decreased bladder contractility27. Our pooled results confirm that a preoperative PVR > 200 mL significantly increases the risk of urinary retention following POP surgery; the differing classification criteria used in the other two studies27,31 prevented their inclusion in the meta-analysis, but their results were similar to those of our study. Miller et al.41 reported that preoperative urodynamic parameters such as peak flow rate, detrusor instability, and PVR were not associated with POUR. This study focused on patients who underwent pubovaginal sling surgery with an allograft and had a small sample size. Future research could further explore the influence of urodynamic data on POUR. Multiple meta-analyses39,42 have suggested an association between diabetes and POUR, but this study did not find such a correlation, which may be related to differences in study populations.

Our study revealed that a prolonged surgical time is a risk factor for POUR. A longer surgical time implies a longer anaesthesia duration and increased medication administration, potentially affecting bladder autonomic function. This may also be related to increased intravenous fluid administration during longer procedures15. The current literature presents inconsistent data regarding the effect of spinal anaesthesia on POUR; some studies have reported increased risk43, but our meta-analysis did not find a correlation. A study by Hakvoort et al.30 revealed that for every 100 mL increase in EBL, the risk of POUR increases by 1.4 times, but this study was not included in the meta-analysis due to differing analytical methods. Furthermore, Verma’s study25 revealed no significant differences between groups regarding intraoperative blood loss, anaesthesia time, or intravenous fluid volume, suggesting the need for further exploration of intraoperative factors related to POUR.

Anti-incontinence surgery significantly increased the risk of POUR following POP surgery in our study, which may be related to the anatomical changes associated with the surgical site and technique. Postoperative oedema around the urethra or overly tight sling placement may more readily lead to bladder outlet obstruction. Research by Misal M et al.44 revealed that the rate of urinary retention in patients who underwent hysterectomy was twice that in patients who underwent similar gynaecological surgeries without hysterectomy. This aligns with our findings, possibly related to the loss of bladder support and changes in the urethral angle following hysterectomy that affect urination44. Although Verma et al.25 reported that the risk of urinary retention after sacrospinous fixation is 2.6 times higher than that in patients who underwent alternative surgeries, the combined results were not statistically significant, likely due to their focus on vaginal sacrospinous fixation, which requires extensive exploration and manipulation during the procedure, potentially leading to tissue oedema and damage to the nerve plexus25.

The main limitations of our meta-analysis include the following: (1) The inclusion of only cohort and case–control studies limited the certainty of the evidence for the outcomes and consequently weakens the interpretation of the findings. (2) Although some studies reported multivariate analysis results, some studies provided only univariate analysis results, which may be influenced by confounding factors to some extent. This could lead to increased heterogeneity during subgroup analyses of the univariate analysis groups. (3) Some studies did not consistently classify outcome indicators, which may contribute to heterogeneity among the studies, and we made efforts to merge similar classifications for analysis, such as those for age and BMI, because we believe that the clinical differences are minimal. Despite this, some indicators from certain studies could not undergo combined analysis, which may introduce bias in the accuracy of the study results and lead to the omission of some potential risk factors or protective factors, such as EBL, catheter removal time, maximum urine flow rate, and BMI. (4) Owing to the generalized conceptualization of pelvic organ prolapse in the literature, most original studies did not report specific prolapse subtypes. This, coupled with the inclusion of multiple prolapse types in some studies, precluded further analysis of outcome measures based on precise clinical diagnoses. (5) There were inconsistencies in the definitions of POUR and catheter removal timing among the studies, which might be important reasons for the high heterogeneity among some studies; however, due to the dispersion or ambiguity in data classification, subgroup analyses could not be conducted to explore in depth the sources of heterogeneity.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis revealed that general factors (older age, age ≥ 60 years, menopausal state), disease-related factors (severe cystocele and preoperative PVR > 200 mL), surgical-related factors (procedure time), and surgical approach factors (anterior repair, anti-incontinence surgery and hysterectomy) were risk factors for POUR after POP surgery. The results of this study have significant implications for individualized preoperative consultations and the selection of surgical methods. Nonetheless, considering the inconsistencies in the definition of POUR, future recommendations should focus on standardizing its definition. Furthermore, because most of the included studies were retrospective, single-centre observational studies, we recommend conducting large, prospective, multicentre cohort studies or RCTs to overcome these limitations and improve the persuasiveness of the results. Finally, it is advisable to utilize large models to develop precise predictive models and assessment tools for the risk of POUR across different surgical approaches for POP, which would help accurately predict the risk of POUR and further guide clinical practice to improve patient outcomes.

Data availability

Data is available in the supplementary file.

References

Rada, M. P. et al. A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on pelvic organ prolapse for the development of core outcome sets. Neurourol. Urodyn. 39, 880–889 (2020).

Collins, S. & Lewicky-Gaupp, C. Pelvic organ prolapse. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 51, 177–193 (2022).

Ghetti, C. et al. The emotional burden of pelvic organ prolapse in women seeking treatment: A qualitative study. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 21, 332–338 (2015).

Weintraub, A. Y., Glinter, H. & Marcus-Braun, N. Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 46, 5–14 (2020).

Peinado-Molina, R. A. et al. Pelvic floor dysfunction: Prevalence and associated factors. BMC Public Health 23, 2005–2015 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. An epidemiologic study of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women: A population-based sample in China. Climacteric 22, 79–84 (2019).

Wu, J. M. et al. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 205, 230–231 (2011).

van der Vaart, L. R. et al. Effect of pessary vs surgery on patient-reported improvement in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 328, 2312–2323 (2022).

Charles W Nager, M.D., Jasmine Tan-Kim, M.D. Surgical management of stress urinary incontinence in females: Retropubic midurethral slings https://www-uptodate-cn-s--zhe.cnu100.libcar.top/contents/surgical-management-of-stress-urinary-incontinence-in-females-retropubic-midurethral-slings(2024).

Elizabeth R Mueller, MD, MSME, FACS. Postoperative urinary retention in females https://www-uptodate-cn-s--zhe.cnu100.libcar.top/contents/postoperative-urinary-retention-in-females (2023).

Drangsholt, S. et al. Active compared with passive voiding trials after midurethral sling surgery: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 143, 633–643 (2024).

Turner, L. C., Kantartzis, K. & Shepherd, J. P. Predictors of postoperative acute urinary retention in women undergoing minimally invasive sacral colpopexy. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 21, 39–42 (2015).

Loo, Z. X. et al. Predictors of voiding dysfunction following Uphold mesh repair for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 255, 34–39 (2020).

Alas, A. et al. Does spinal anesthesia lead to postoperative urinary retention in same-day urogynecology surgery? A retrospective review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 30, 1283–1289 (2019).

Anglim, B. C. et al. A risk calculator for postoperative urinary retention (POUR) following vaginal pelvic floor surgery: Multivariable prediction modelling. BJOG 129, 2203–2213 (2022).

Brouwer, T. A. et al. Postoperative urinary retention: Risk factors, bladder filling rate and time to catheterization: An observational study as part of a randomized controlled trial. Perioper Med. (Lond). 10, 2–12 (2021).

Sappenfield, E. C. et al. Predictors of delayed postoperative urinary retention after female pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 32, 603–608 (2021).

Lo, T. S. et al. Predictors of voiding dysfunction following extensive vaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 28, 575–582 (2017).

Golubovsky, J. L. et al. Risk factors and associated complications for postoperative urinary retention after lumbar surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine J. 18(9), 1533–1539 (2018).

Wang, W. et al. Economic impact of postoperative urinary retention in the US Hospital setting. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 11, 29–34 (2024).

Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339, b2700 (2009).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Friedrich, J. O. et al. Ratio of means for analyzing continuous outcomes in meta-analysis performed as well as mean difference methods. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 556–564 (2011).

Balshem, H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 401–406 (2011).

Verma, V. et al. Risk factors for postoperative voiding dysfunction following surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 263, 127–131 (2021).

Schmidt, P. et al. The association of preoperative medication administration and preoperative and intraoperative factors with postoperative urinary retention after urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 27, 527–531 (2021).

Son, E. J. et al. Predictors of acute postoperative urinary retention after transvaginal uterosacral suspension surgery. J. Menopausal Med. 24, 163–168 (2018).

Chong, C. et al. Risk factors for urinary retention after vaginal hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 59, 137–143 (2016).

Eto, C. et al. Retrospective cohort study on the perioperative risk factors for transient voiding dysfunction after apical prolapse repair. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 25, 167–171 (2019).

Hakvoort, R. A. et al. Predicting short-term urinary retention after vaginal prolapse surgery. Neurourol. Urodyn. 28, 225–228 (2009).

Ghafar, M. A. et al. Size of urogenital hiatus as a potential risk factor for emptying disorders after pelvic prolapse repair. J. Urol. 190, 603–607 (2013).

Yune, J. J. et al. Postoperative urinary retention after pelvic organ prolapse repair: Vaginal versus robotic transabdominal approach. Neurourol. Urodyn. 37, 1794–1800 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Short-term effects on voiding function after mesh-related surgical repair of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause 22, 993–999 (2015).

Zuo, S. W. et al. Frailty and acute postoperative urinary retention in older women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Urogynecology (Phila). 29, 168–174 (2023).

Steinberg, B. J. et al. Postoperative urinary retention following vaginal mesh procedures for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 1491–1498 (2010).

Bekos, C. et al. Uterus preservation in case of vaginal prolapse surgery acts as a protector against postoperative urinary retention. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3773–3781 (2020).

Priyatini, T. & Sari, J. M. Incidence of postoperative urinary retention after pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Cipto Mangunkusumo National General Hospital. Med. J. Indones. 23, 218–222 (2014).

Zhang, B. Y. et al. Risk factors for urinary retention after urogynecologic surgery: A retrospective cohort study and prediction model. Neurourol. Urodyn. 40, 1182–1191 (2021).

Chang, Y. et al. Risk factors for postoperative urinary retention following elective spine surgery: A meta-analysis. Spine J. 21, 1802–1811 (2021).

Barr, S. A. et al. Incidence of successful voiding and predictors of early voiding dysfunction after retropubic sling. Int. Urogynecol. J. 27, 1209–1214 (2016).

Miller, E. A. et al. Preoperative urodynamic evaluation may predict voiding dysfunction in women undergoing pubovaginal sling. J. Urol. 169, 2234–2237 (2003).

Huang, L. et al. Risk factors for postoperative urinary retention in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 37, 2409–2420 (2022).

Hernandez, N. S. et al. Assessing the impact of spinal versus general anesthesia on postoperative urinary retention in elective spinal surgery patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 222, 107454 (2022).

Misal, M. et al. Is hysterectomy a risk factor for urinary retention? A retrospective matched case control study. J. Min. Invasive Gynecol. 27, 1598–1602 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Dongqing Gu of Women and Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University for her guidance on meta-analysis methodology

Funding

This study were funded by Science-Health Joint Medical Scientific Research Project of Chongqing (grant number: 2023MSXM055) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82171622).The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z LL designed the work, conducted the review, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript. H S and D L made substantial contributions to the literature search and revision of the manuscript. D L, S CY and Z TT helped to analyze the data. Z TT and H P have contributed to this work through figure preparation, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. S CY had the idea for and designed the study, interpreted data, drafted, and critically revised the report and supervised the study. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and approved the final version of the manuscript accepted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Dai, L., Hu, S. et al. Risk factors for postoperative urinary retention following pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 41715 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25652-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25652-7