Abstract

Protective coal seam mining is an important technical method used to strengthen the effect of gas extraction and prevent accidents caused by gases. However, it is necessary to thoroughly study the selection of the first coal seam to be mined and its effects related to pressure relief and permeability enhancement under the complex conditions of a coal seam group. This includes studying the relationships that govern pressure relief and permeability enhancement and the mechanism of the extraction of gas. In this study, a certain mine was used as engineering background. A damage-permeability model of a coal rock body undergoing mining disturbance was constructed based on experimental results and related theories. COMSOL Multiphysics software was used to perform numerical calculations with the model. The distribution of gas pressure in a coal seam was simulated under different mining conditions for the first mining seam. The first mining layer for protective coal seam mining of a coal seam group was identified. On this basis, the changes in parameters such as coal seam gas content, vertical stress and seepage velocity were studied during the advancement of the working face of the first mining seam. Furthermore, the numerical simulation was used to analyze the arrangement of boreholes for gas extraction from the bottom extraction roadway and the effect of extraction on pressure relief and permeability enhancement during protective coal seam mining. The results of the study showed the following: (1) Selecting 6# coal seam as the first mining seam had the best pressure relief effect on the adjacent seam, followed by 4# coal seam, and 8# coal seam had the worst pressure relief effect. (2) With the advancement of the 6# coal seam working face, the range of the pressure relief of the protected seam gradually expanded, the maximum stress relief degree of 4# coal seam was 25%, and the maximum decrease in gas content was 28.1%. The maximum stress relief degree of 8# coal seam was 60%, and the maximum decrease in gas content was 45.9%. (3) The gas content of coal seams decreased rapidly after extraction using boreholes; the gas contents of 4# coal seam and 8# coal seam decreased 81.25% and 99%, respectively, compared with the original values after 50 days of extraction. The efficiency of extraction by drill holes was related to the degree of decompression in the coal seam.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal and gas outbursts are a powerful phenomena that occur when a large amount of coal rock in the coal rock body around a mining space carries a large amount of gas and is suddenly thrown into the mining space, which seriously threatens the development of the coal industry and the safety of workers. China is one of the countries where coal gas outbursts are the most significant in the world, and according to statistics, between 2011 and 2020, 93 gas accidents with 645 fatalities occurred in China and caused very great economic losses1,2,3,4. Protective coal seam mining is currently one of the most effective methods for the prevention and control of coal and gas outbursts, and an in-depth study of the pressure release mechanism during protective coal seam mining is of great significance for the prevention of accidents in coal mines caused by the violent release of gases.

Over the years, related researchers have conducted research on mechanisms for unloading pressure unloading in protective coal seam mining and achieved fruitful results. Chen et al.5 analyzed the mechanical evolution law and pressure relief and permeability enhancement mechanism of protective layer mining under complex structural stress through FLAC3D-COMSOL coupled simulation. Wang et al.6studied the influence of interbed lithology on the mining of protective seams on the basis of a statistical analysis of data on the protective effect of mining protective seams with different relative layer spacings in various mining areas. Wang et al.7 proposed the method of protective range expansion for the difficult problem that protected seams could not be mined continuously due to the small protection range. Liu et al.8,9,10,11studied the evolution of fractures in the overlying coal rock seam in a quarry during the sequential back mining of the double-protective coal seam by using physical simulation and numerical simulation and concluded that the equilibrium state of the overlying rock stress in the quarry during secondary mining after back mining of the first protective coal seam was very easily destroyed, which increased the protective range of pressure relief of the protective coal seam. Ma et al.12 proposed a composite coal rock protection seam in the absence of a coal seam of suitable thickness as a protection seam and conducted a series of simulations and empirical engineering studies on the protective effect under coal rock composite protective coal seam mining. With the mining of a composite protective seam, the pressure in the protective seam began to be released, and the gas release was significantly increased compared with that before the mining of the duplicate protection seam. Cheng et al.13,14analyzed the effect of multiple protective mining on the pressure release from the protected seam by establishing a coupled stress-gas flow model for coal rock mining. Zhou et al.15 studied the collapse of the overburden rock and the gas enrichment relationships of a protected seam under the influence of double coal seam mining by using similar simulation and theoretical analysis methods. Kou et al.16,17studied the effect of pressure unloading on the lower protected seam after mining the upper protective seam under the condition of overlapping and staggered arrangements of working faces of each coal group in space by FLAC3D numerical simulations and field measurements. X Cheng et al.18analyzed the effect of the mining dynamics of different mining methods of the protective seam on the coal rock body and revealed the mechanism of pressure unloading of the protective seam mining. The research results enriched the theory of pressure relief mining of protective seams. Niu et al.19used a combination of numerical simulation and field tests to systematically study the stress distribution in the overburden rock, displacement of the protected seam, and thickness change and distribution in the damage zone after mining of the protective coal seam. Yang et al.20proposed the concept of an effective pressure relief protective range based on the analysis of stress release and plastic zone development in a lower protected seam and established a model of stress change and fracture development in the lower protected seam. Li et al.21studied the evolution and distribution of the stress field in the bottom plate of the mining area during the recovery process of the protective coal seam by theoretical analysis and numerical simulation and found that the bottom plate of the mining area tends to be concave and the striking surface is an “O”-shaped spherical shell. Yin et al.22proposed the concept of an effective pressure relief protective range based on the pressure relief and plastic zone of the subducting coal body, established the development of a model of stress change and fracture development in a subducting coal body and derived the pressure relief principle of the subducting coal body when the coal seam is protected at different heights. Liu et al.23studied the stress distribution at the boundary of the stress-relaxation zone during protective coal seam mining through laboratory experiments and field measurements and proposed effective measures to prevent and control disasters caused by the violent release of coal and gas. Yuan et al.24established a theoretical model for the calculation of vertical stress, horizontal stress and shear stress in the bottom coal rock seam according to the semi-infinite plane model in the theory of elastic mechanics and derived the stress expression at any point of the bottom plate under the distributed force. An expression for stress under the action of distributed forces at any point of the bottom slab was derived, and the range of pressure relief after mining of the upper protective layer was determined. Yue et al.25 systematically investigated the water transport law during spontaneous seepage of loaded coal by self-developed experimental system, and the results showed that water would compete with gas after entering the micropores of the coal body, leading to the reconfiguration of the permeability channels of the coal body, and thus altering the desorption and transport characteristics of the gas. Yue et al.26 pointed out that the formation of stagnant water by the injection of water into the coal seam would significantly affect the desorption characteristics of the gas-containing coal in different migration stages, and that water–gas competition adsorption and pore wetting effects could enhance the permeability and promote the release of the gas. The water–gas competition adsorption and pore wetting effect can improve the permeability of coal body and promote the release of gas. These studies have deepened the understanding of permeability enhancement in the mining process of protective seams from the micro-mechanism, and provided new ideas for the interpretation of the decompression effect under the complex conditions of the coal seam group.

The above research results are of great significance for understanding and controlling pressure release from protective coal seams and improving the effect of gas extraction, but further research is needed on the selection of the first mining seam and its pressure release effect under the complex conditions of a coal seam group. Therefore, based on laboratory experiments and related research results and theories, this study established a permeability model considering the influence of coal and rock damage failure under the influence of mining disturbance and applies it to the engineering practice of protective coal seam mining. Through the comparison of different protective coal seam mining schemes, the first mining unloading layer was selected, and the numerical simulation method was applied to investigate the unloading effect of protective coal seam mining and the gas transport characteristics of coal rock seams. On this basis, the spatial and temporal effects of pressure relief during protective coal seam mining were fully considered to analyze the effect of gas extraction on bottom extraction stopes. The results of this research are of great significance to reveal the mechanism of pressure relief in protective coal seam mining and to prevent accidents caused by the violent release of coal and gas.

Coal rock seepage experiment

Specimen preparation and experiment

The coal samples used for the experiment were taken from the eastern mining area of the second level of a certain mine. Fresh coal samples with large, complete and regular shapes were taken from the mine and transported back to the test room safely and without damage. The coal was processed into 50 mm × 100 mm cylindrical standard coal samples. Before the experiment, the coal samples were dried in an oven at 105 °C to eliminate the effect of moisture. The test was conducted using the RLW-500G triaxial creep-percolation test system that was developed in this laboratory, and the principle diagram of the experimental system is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Experimental system diagram. (1) vacuum pump, (2) vacuum gauge, (3). gas valve, (4) gas cylinder, (5) pressure gauge, (6) regulator, (7) outlet pressure gauge, (8) electronic flow meter, (9) specimen, (10) Axial pressure loading system, (11) pressure chamber, (12) circumferential pressure loading system.

The experimental setting was 10 MPa for the surrounding pressure, 1 MPa, 2 MPa or 3 MPa for the gas pressure, and 99.99% gas by volume fraction. After starting the experiment, the coal sample was first wrapped with a heat-shrinkable tube and put into the pressure cylinder, after which axial and radial extensometers were installed. Finally, the gas inlet and outlet gas pipes at both ends of the coal sample were connected well, and the stability and gas tightness of the coal sample connection were checked. Then, loading was started through the control to apply three-dimensional hydrostatic pressure 10 MPa to the sample. Then, the air pressure was raised to a predetermined value, and the gas pressure was kept unchanged. After the methane gas was fully adsorbed, the surrounding pressure was kept unchanged and loading continued, using the force control mode to increase the axial pressure according to the rate of 100 N/s. To protect the experimental equipment, when the coal rock is in the post-peak state, it was loaded according to the displacement control mode. The change in outlet gas flow rate was recorded throughout the experiment, and the data collection period was 3 s. The coal sample permeability was calculated from the outlet flow rate, and the gas permeability of the coal sample was calculated by the formula, The gas permeability of the coal sample is

where: \(p_{1}\) is the gas pressure at the inlet end; \(p_{2}\) is the gas pressure at the outlet end; \(q\) is the gas flow rate at the outlet end; \(\mu\) is the gas viscosity coefficient; and \(L\) is the length of the coal sample.

Experimental results and analysis

Coal permeability curves under different gas pressures were obtained through the experiments, as shown in the following Fig. 2.

As shown in the figure, under experimental conditions with gas pressures set at 1 MPa, 2 MPa, and 3 MPa, the following observations can be made: When the coal sample is in the pre-peak stage, as the external load continues to increase, the fractures within the coal gradually close, and the permeability exhibits a decreasing trend. When the external load reaches a critical value, the coal sample transitions from the pre-peak stage to the post-peak stage. At this point, the load-bearing capacity of the coal sample begins to decrease, stress levels drop, and internal damage and fracture occur within the coal sample. A large number of fractures expand and develop, forming favorable gas flow pathways, resulting in a significant increase in permeability. In summary, both during the pre-peak and post-peak stages of the coal body, the permeability of the coal sample exhibits an exponential trend with respect to stress.

Numerical simulation coupling modeling

Model assumptions and definitions

During coal seam mining, the disturbance caused by the advancement of the mining face leads to stress concentration in the coal body ahead of the face and in the rock masses flanking the coal seam. This results in damage and failure of both the coal body and rock masses, ultimately causing changes in permeability. Simultaneously, due to the adsorption–desorption behavior of coal towards gas, under mining disturbance and decompression conditions, gas desorbs from the coal and transforms into free gas. This causes significant changes in permeability during the loading process of coal samples. Therefore, based on the aforementioned experimental results and relevant theories, separate coal-damage permeability models and rock-damage permeability models under mining disturbance were established.

The following assumptions were made to simplify the calculation process:

-

1.

The coal body and rock body had elastic double pore structure.

-

2.

The effect of temperature on the dynamic viscosity of the gas was neglected.

-

3.

The gas was an ideal gas and conformed to the ideal gas equation of state.

-

4.

The coal was saturated with gas.

-

5.

The pressure difference between the matrix pores and fracture was neglected.

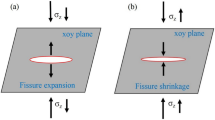

To study the permeability of coal and rock bodies under mining disturbance, they were considered as double pore structure, as shown in Fig. 3(a):

The coal and rock structure can be viewed as double pore structure consisting of matrix blocks and fracture pores. The coal matrix block was a cubic block of length with fracture width b. Its size depended on the burial depth, pore pressure, stress field and physical properties of the coal. The pore system was the main storage space of gas, while the fracture system was the main channel of gas seepage.

Coal body damage-permeability model

Coal body deformation control equation

As an adsorptive double pore medium, the deformation of the coal body is affected by external stress, pore pressure and gas adsorption expansion at the same time. Based on the generalized Hooke’s law, the deformation control equation of the coal body was obtained as27:

where \(ui\) is the displacement component \(v\) is the fluid velocity, \(G\) is the shear modulus, \(\alpha\) is the Biot coefficient \(\alpha = 1 - K/Ks\), \(Ks\) is the bulk modulus of the skeleton, \(K\) is the matrix bulk modulus, \(p\) is the gas pressure, \(\varepsilon_{L}\) is the Langmuir bulk strain, \(P_{L}\) is the Langmuir pressure constant, and \(f_{i}\) is the bulk force component. The above equation reflects the effect of gas flow on the deformation of a coal body.

Coal body gas flow control equation

The gas flow in the coal body includes free gas and adsorbed gas due to the adsorption–desorption of the coal body. Based on the double pore structure, the gas flow control equation of the coal body can be obtained as:

where \(\phi_{m}\) is the matrix porosity, \(\rho_{c}\) is the density of the coal body, \(V_{L}\) is the Langmuir volume constant, \(k\) is the permeability, and \(\mu\) is the viscosity coefficient of the gas.

Permeability equation of the coal body considering the effect of damage

The permeability change is influenced by the pores and fractures, where the evolution of the pores of the coal body is mainly influenced by the effective stress and pore pressure, and the pore evolution equation of the coal body is:

where \(M = \varepsilon_{V} + \frac{1}{{K_{s} }}p - \varepsilon_{s}\) , \(M_{0} = \varepsilon_{V0} + \frac{1}{{K_{s} }}p_{0} - \varepsilon_{L} p_{0} /\left( {p_{0} + p_{L} } \right)\) , \(\varepsilon_{V}\) is the volume strain.

The fracture evolution is due to the change in effective stress, and the equation of fracture evolution of the coal body is:

where \(\phi_{f}\) is the fracture porosity, \(\varepsilon_{s} = \frac{{\varepsilon_{L} p}}{{P_{L} + p}}\) is the gas adsorption strain, \(E\) is the coal and rock mass elastic modulus, and \(Em\) is the matrix elastic modulus.

However, under the disturbance of protective coal seam mining, stress concentration occurs in the coal seam in front and on both side of the rock body, and damage failure occurs inside both coal and rock body. The accumulation of damage within the coal and rock masses manifests itself macroscopically as the initiation and expansion of microcracks that eventually form through fractures and changes in permeability. To consider the effect of damage failure of coal and rock bodies, the fracture evolution equation considering damage failure was studied, and here, it was considered that the coal matrix unit continued to failure under mining disturbance, as shown in Fig. 3(b).

Considering the coal and rock mass as an elastic system composed of matrix and fractures, which was considered to undergo only elastic continuous deformation, the relationship between the elastic modulus of the matrix and the fracture unit was found:

where \(E_{f}\) is the modulus of elasticity of the fracture unit.

According to the strain equivalence hypothesis, the damage variable D is defined as:

where \(E_{0}\) is the modulus of elasticity of the coal and rock mass in the undamaged state.

Substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (6) yields:

To determine the damage variables of the numerical analysis unit, the maximum tensile stress criterion and the Mohr‒Coulomb criterion were used to determine the tensile and shear damage. The defining equation is:

where \(\sigma_{1}\) and \(\sigma_{3}\) are the maximum principal stress and minimum principal stress, respectively, \(f_{t}\) and \(f_{c}\) the uniaxial tensile strength and compressive strength of the rock mass, respectively. Then, the stress type damage variable of the cell can be expressed as:

where \(\sigma_{t}\) and \(\sigma_{c}\) are the maximum positive stress and minimum positive stress, and \(f_{t0}\) and are \(f_{c0}\) the tensile stress and shear stress, respectively.

The fracture evolution equation considering damage failure is obtained by substituting Eq. (9) into Eq. (6) as:

The permeability of coal body can be expressed as the sum of the permeability of pores and fractures, which can be expressed as:

where \(k_{f}\) is the fracture permeability and \(k_{m}\) is the pore permeability.

Since a cubic relationship is satisfied between the pore, fracture and corresponding permeability of the micro-scale element body, the pore permeability equation and fracture permeability equation obtained by calculating Eq. (4) and Eq. (11) are substituted into Eq. (12) to obtain the permeability equation of the coal body considering the influence of damage as:

where the subscript 0 indicates the initial state.

Rock damage-permeability model

Rock deformation control equation

In addition, considering the rock mass as a dual-pore medium, its deformation is governed by external stresses, pore pressure, and related factors. Building upon the deformation control equation of the coal body presented above, the deformation control equation of the rock mass is formulated as follows:

This equation removes the effect of gas adsorption on deformation relative to the coal body deformation control equation.

Rock gas flow control equation

The gas flow control equation for the rock mass can be directly expressed by Darcy’s law as follows:

where \(\vec{q}\) is the Darcy velocity of the fluid, \(\rho_{f}\) is the density of the gas, \(g\) is the acceleration of gravity and \(\nabla z\) is the unit vector in the direction of gravitational action.

Permeability equation of rock considering the effect of damage

The permeability variation of the rock is also influenced by pore space and fracture, where the pore evolution equation of the rock is the same as that of the coal body. For the evolution equation of the fracture of the rock, the effect of gas adsorption is neglected with respect to the coal body. Thus, the fracture evolution equation of the rock body considering damage failure is obtained as:

The same calculation as in Eq. (4) and Eq. (16) yields the pore permeability equation and the fracture permeability equation, which are finally substituted into Eq. (12) to obtain the permeability equation of the rock body considering the influence of damage as:

Model coupling

The above Eqs. (2) Eq. (3) Eq. (13) and Eq. (14) Eq. (15) Eq. (17) constitute the coal-body damage-permeability model and rock damage-permeability model under mining disturbance, respectively. The two permeability models differ due to the adsorption–desorption of gas by the coal body, but the overall coupling equations were similar. As the working face advances, the effective stress of the coal rock layer near the mining area changes, causing changes in the porosity and fracture rate of the coal and rock body. This leads to an increase in the permeability of coal and rock bodies, the gas in the coal body undergoes desorption and diffusion, and seepage occurs in the coal and rock bodies. The specific coupling relationship is shown in Fig. 4.

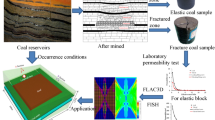

Model validation

In order to verify the reliability of the theoretical model, a three-dimensional industrial CT scanning test was introduced to reveal the changing rules of fissure expansion and permeability of the coal samples before and after the loaded rupture. The phoenix v| tome |x s industrial CT system was used to scan the coal samples at different stages of the triaxial loading process, and high-resolution images of the internal fracture evolution were obtained. Figure 5(a) shows that, in the pre-peak stage, only a few discrete microfractures existed in the coal samples, and the fracture morphology was dominated by the isolation distribution, and the overall connectivity was relatively poor; whereas, in the post-peak stage, the fracture was significantly expanded and connected, forming a macroscopic fracture zone with the dominant seepage. However, in the post-peak stage, the fissures were significantly expanded and connected, forming macroscopic fissure zones and dominant seepage channels. On this basis, Comsol was further used to carry out numerical simulation to reconstruct the dynamic evolution of the coal body fissure field and seepage field. As can be seen in Fig. 5(b), the seepage field in the pre-peak stage is limited by the fissure closure, which is only a localized and weakly connected flow path; in the post-peak stage, the fissure structure is drastically opened and the seepage channel is obviously strengthened to form a highly efficient transport path, which leads to a sudden increase in overall permeability and the evolution of the seepage field. The evolution of the seepage field is highly coupled with the expansion of the fracture field.

Combining the experimental data and the above theoretical model, the comparison graph between the test and the theoretical model of the permeability change during the full stress–strain process of coal samples was obtained. As shown in Fig. 6: the coal sample is in the pre-peak stage at the initial loading, with the increasing load, the strain also increases gradually, the coal body fissures close gradually, so the permeability of the coal sample decreases, when entering the post-peak stage, the damage occurs inside the coal sample, a large number of coal body fissures develop, and a good gas seepage channel is formed inside the coal body, and the permeability rises rapidly. The above rule is highly consistent with the phenomenon of “sudden increase of permeability after peak” observed in the triaxial permeability test, which verifies the correctness and reasonableness of the theoretical model, and provides theoretical support for the subsequent research on the unloading of pressure and gas transportation characteristics of coal seams.

Numerical simulation study and analysis

Establishment of numerical model

This paper takes the sampled mining area as the research object, where the coal seam burial depth is 800 m, and the main coal seams are 8#coal, 6#coal, and 4#coal. The average thickness of 8# coal is 3.4 m, the average thickness of 6# coal is 2.91 m, and the average thickness of 4# coal is 2.29 m. The spacing between 8# coal and 6# coal, and between 6# coal and 4# coal is 33 m and 26 m, respectively, and the angle of inclination of the coal seams is 13°. The measured maximum gas pressures at the current mining level are 1.56 MPa, 1.31 MPa, and 1.71 MPa, and the maximum gas contents are 6.1 m3/t, 6.2 m3/t, and 6.4 m3/t, respectively. Figure 7 shows the contour map of the coal seam floor.

To study the relationships of unloading and penetration of protective coal seam mining as well as gas transportation and the effect of unloading gas extraction, a numerical model for the calculation protective coal seam mining was established using the software COMSOL Multiphysics, as shown in Fig. 8. The mining method of the coal seam was toward longwall mining, and the drilling arrangement was bottom extraction roadway tendency interception drilling. Two vertical surfaces along the tendency and strike were selected as the study surface, and the strike protective coal seam mining model and the tendency borehole extraction model were established, as shown in Fig. 9.

The mining model for advancing toward the protective layer, as shown in Fig. 9(a), is primarily used to investigate the pressure-relief effects of protective layer mining and the gas migration characteristics within coal and rock strata. Based on these findings, the initial coal seam to be mined under group coal seam mining conditions is determined. The model dimensions are 360 m × 140 m, comprising 23 rock/coal strata layers. Key physical and mechanical parameters are listed in Table 1. Regarding seepage boundary conditions, the model’s left–right, top–bottom, and front-back boundaries are set as no-flow boundaries, with internal gas pressure in the goaf maintained at 1 atmosphere. For mechanical boundary conditions, horizontal displacement is constrained on both sides, while vertical displacement is constrained at the bottom. Using the regression formula for vertical stress versus burial depth in coal mines proposed by Kang28, the theoretical self-weight stress of the overburden at a burial depth of approximately 800 m is calculated to be about 19.6 MPa. This result is consistent with actual measurement data from the mining area. To ensure boundary condition rationality and simplify calculations, a vertical stress of 20 MPa was applied at the model top to simulate the gravitational stress from 800 m of overburden. According to the regression formula, the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses are approximately 20.48 MPa and 10.99 MPa, respectively, placing the overall stress and vertical stress within the same magnitude range. Given this study’s focus on vertical unloading effects induced by protective layer mining and their impact on gas migration patterns, the model did not apply separate horizontal stress. Instead, it approximated the in-situ stress environment by constraining horizontal displacement while applying vertical stress. This approach ensures numerical stability and convergence while highlighting the primary effects under investigation.

The drilling extraction model is shown in Fig. 9(b). After the first mining seam was determined, the coal seam unloading and drilling gas extraction engineering conditions were considered comprehensively, and the gas extraction effect of the bottom extraction roadway drilling under the first mining seam mining pressure relief was analyzed. The model size was 360 m × 225 m, and the main coal rock layer physical parameters and model boundary conditions were the same as the protective coal seam mining along the strike model.

Selection of the first mining coal seam

Figures 10 and 11 present the gas pressure distributions of coal seams under different first-mining scenarios when the working face advances to 160 m. After mining the protective layer, gas escapes into the mined-out area and the pressure decreases significantly, though to varying degrees. When the 8# coal was mined first, the pressures of the 4# and 6# coals decreased from 1.71 MPa to 1.62 MPa and from 1.31 MPa to 0.96 MPa, respectively—reductions of only 5.2% and 26.7%, indicating a limited relief effect. When the 4# coal was mined first, the pressure of the 6# coal dropped sharply from 1.31 MPa to 0.43 MPa (67.4%), while the pressure of the 8# coal decreased only from 1.56 MPa to 1.20 MPa (23.6%), showing an unbalanced unloading effect between the upper and lower seams. In contrast, mining the 6# coal first reduced the pressure of the 4# coal from 1.71 MPa to 0.81 MPa (52.6%) and the 8# coal from 1.56 MPa to 0.44 MPa (71.6%), demonstrating the strongest overall pressure-relief performance.

This outcome is closely related to inter-seam mechanics and seepage mechanisms: being centrally located within the coal seam group, the 6# coal can both release stress in the overlying 8# coal—facilitating fracture propagation and permeability enhancement—and transmit depressurization downward to promote gas desorption and migration from the 4# coal. Thus, a broader and more balanced pressure-relief effect is achieved. In summary, the 8# coal as the first-mining seam shows the weakest effect, the 4# coal provides partial but uneven relief, whereas the 6# coal delivers the optimal depressurization performance. Therefore, the 6# coal is determined to be the preferred first-mining seam under coal seam group conditions.

Research on the effect of pressure relief on protective coal seam mining

Based on the selection of 6# coal as the first mining seam, the changes in coal seam gas content, vertical stress, seepage velocity and other pressure relief parameters during the advance of the working face of 6# coal first mining seam were studied, the pressure relief effect of the protected seam under the mining of purely protective coal seam was analyzed, and support for the study of pressure relief gas extraction relationships in the next section was provided.

Vertical stress variation in the stope

Figure 12 shows the variation in the vertical stress in the stope with the advance of the working face under the mining conditions of the protective coal seam. The overall stress distribution was approximately symmetrical, with the middle of the mining face as the axis; the stress was concentrated in the middle and decreased at both ends of the mining face; and the further the excavation distance was, the less symmetrical it was. Closer to the mining face, the magnitude of stress change was greater, the working face advanced farther, and the range of the affected stress area was wider. This was because the process of advancing the mining face applied an external force on the overlying coal rock layer. Thus at positions closer to the mining face, the influence of the external force was greater, and the magnitude of the stress change was greater. The farther the working face advanced was equivalent to the application of greater external force, and the range of the affected stress area was wider.

Figure 13 shows the vertical stress variation curves for different coal seams as the working face advances. To ensure comparability of stress relief levels, this study uses the vertical stress calculated based on the overburden self-weight theory (approximately 19.6 MPa) as the baseline stress, and calculates the stress relief ratio accordingly. The figure reveals that for 8#coal: at 40 m advance, maximum stress relief reached approximately 25%; at 80 m advance, it reached approximately 55%; at 120 m and 160 m advances, maximum stress relief stabilized around 60%. For 4#coal, when the working face advanced to 40 m, the maximum stress relief was approximately 10%; at 80 m, it reached about 20%; and at 120 m and 160 m, the maximum stress relief remained around 25%. It should be noted that after the working face advanced to 120 m, the maximum stress relief in the protected layer slightly decreased. This was due to the expansion of the stress relief zone increasing the pressure-bearing area in the mining area, leading to local stress redistribution. However, overall, the stress relief zone continued to expand with the advancement of the working face. From the above stress change contour maps and curves of the protected layer, it can be seen that the mining of the protective layer had a good stress relief effect on 8#coal.

Change in gas content of the protected seam

Figure 14 shows a cloud chart of the change in coal seam gas content with the advance of the working face. As the working face advanced, 4# and 8# coal seam gas gushed out of the coal in the direction of the mining area, the coal seam gas content decreased, and the range of the gas seepage field gradually became larger. This was because the pressure relief effect of 6# coal seam mining changed the stress state of the surrounding rock, and the fractures in the coal rock body expanded, leading to an increase in its permeability. Under the effect of a gas pressure gradient, the gas in 4# and 8# coal seams underwent desorption and transport, and the gas content decreased.

Figure 15 shows a curve of the change in coal seam gas content with the advance of the working face. The gas content of coal seam 4# experienced a drop from 6.4 m3/t to a minimum of 6.18 m3/t, with a maximum decrease of 3.4%, when the working face advanced to 40 m. However, as the working face advanced further to 80 m, the gas content of the coal seam dropped significantly, with a maximum decline of around 28.1%. Similarly, for coal seam 8#, the gas content decreased from 6.1 m3/t to a minimum of 5.6 m3/t, with a maximum drop of 8.2%, when the working face advanced to 40 m. And as the working face advanced to 80 m, the gas content of the coal seam experienced a significant decrease, with a maximum decline of approximately 45.9%. Through the mining of the protective seam (6# coal), the 8# coal seam experienced a more significant pressure relief effect, which was more pronounced compared with the 4# coal seam.

Gas flow field variation in the stope

Figure 16 shows a cloud chart of the change in the gas seepage field in the stope during the advance of the working face. With the continuous advancement of the working face of the protective coal seam, the free gas and desorbed gas in the protected seam were continuously transported to the mining area under the action of mining pressure relief, the seepage rate increased, and the scope of seepage field expanded. The seepage field was basically trapezoidal in shape, with the maximum seepage velocity in the middle, and decreased at the edges until it tended to zero.

Research on gas extraction during protective coal seam mining with pressure relief

According to the above study, purely relying on the protective coal seam mining pressure relief cannot completely achieve the effect of abatement, and drilling extraction measures should be taken. However, due to the low original permeability of the coal body, it was difficult to achieve effective extraction without mining pressure relief. Thus the spatial and temporal effects of pressure relief by protective coal seam mining should be fully considered, and the two should cooperate to achieve efficient extraction of gas and achieve the effect of coal seam ablation.

Prior to mining the protective layer, gas extraction boreholes should be pre-arranged to ensure sufficient time and space for gas control, enabling efficient gas extraction during the pressure-relief permeability enhancement phase. In determining the location of the bottom gas extraction roadway, this paper primarily relies on the vertical stress distribution and decompression range obtained from numerical simulations. It also comprehensively considers engineering factors such as coal seam stratigraphic conditions and drilling feasibility to establish a representative layout position. Simultaneously, based on the transmission of extraction negative pressure and the size of the extraction radius, combined with the actual conditions at the mine site, the spacing and layout pattern of the drill holes are determined.

Change in the gas flow field in the stope during drilling and extraction

Figure 17 shows a cloud chart of the variation in the gas flow field with extraction time in the quarry under the mining conditions of protective coal seam. Under the negative pressure of bottom extraction, the gas flowed more in the direction of the drill hole, but under the pressure relief of mining, some gas continued to move to the extraction area. The gas seepage vector arrow near the borehole for gas extraction was significantly larger than the surrounding rock, which indicated that the borehole was more effective in extracting gas.

Change in gas content of the protected seam during drilling and extraction

Figure 18 shows a cloud chart of the variation in gas content in the quarry with extraction time under the mining conditions of the protective coal seam. With increasing extraction time, the free gas in the protected seam was continuously transported to the extraction borehole under the action of negative extraction pressure, and the gas content of the protected seam was continuously reduced. The gas content of the coal seam was approximately elliptically distributed with the borehole as the center, and the gas content gradually increased from the borehole to the outside.

Figure 19 shows a curve of the change in coal seam gas content with extraction time. The gas content of 4# coal seam decreases slowly as the extraction time increases. At 10 days of extraction, the gas content near the extraction borehole is approximately 2.6 m3/t. After 30 days, it decreases to around 2.0 m3/t, and after 50 days, it drops to about 1.2 m3/t. This translates to an 81.25% reduction in the gas content of the coal seam in the extraction area. In contrast, for 8# coal seam, the gas content near the extraction borehole decreases rapidly with increasing extraction time. After 10 days, it drops to approximately 0.8 m3/t, and after 50 days, it further decreases to about 0.06 m3/t. Consequently, the gas content of the coal seam in the extraction area is reduced by 99%. The gas content of the protected seam is significantly reduced through proper drilling and extraction. Additionally, the extraction effectiveness of 8# coal drilling is superior to 4# coal drilling.

Variation in the velocity of extraction of drilling gas

Figure 20 shows a curve of the change in extraction velocity with extraction time. In the early stage of extraction, the gas extraction rate of both coal seams decreases rapidly, with a larger magnitude of decrease. However, as time goes on, the overall trend of gas extraction rate decreases. In the middle and late stage of extraction, the change in gas extraction rate becomes small, and it tends to stabilize. The initial gas extraction rate for 4# coal seam was 7.5 m3/d. After 15 days, the gas extraction rate decreased rapidly to 0.9 m3/d, and then stabilized at 0.06 m3/d. Similarly, for 8# coal seam, the initial gas extraction rate was 16.5 m3/d. At 15 days, the gas extraction rate dropped quickly to 0.4 m3/d, and subsequently stabilized at 0.04 m3/d. On the one hand, the initial gas extraction rate of the borehole is larger because of the desorption and transformation of a significant amount of adsorbed gas in the coal seam from an adsorbed state to a free state. This results in a rapid increase in the content of free gas. On the other hand, the stress state of the surrounding rock body is altered by the unloading effect of coal seam mining. This leads to the expansion of coal rock body fissures and an increase in permeability. Consequently, favorable conditions for gas extraction from the borehole are provided. The initial gas extraction rate of the 8# coal seam is higher than that of the 4# coal seam, which confirms that protective coal seam mining is more effective in reducing pressure on the 8# coal seam.

Analysis of the effects of drilling and extraction

To quantitatively analyze the effect of unloading gas in coal seams extracted by drilling, numerical simulations were conducted to obtain the variation in average gas pressure with time for coal seams extracted by drilling and not extracted under protective coal seam mining, as shown in Fig. 21. The changes in the average gas pressures of seams of 4# and 8# coal seams were basically the same, with a decaying trend over time, which was in line with the general rule. Both with and without extraction, the average gas pressure decreased rapidly at the beginning and slowly and gradually stabilized in the middle and late stages. For 4# coal seam, the average gas pressure decreased from 1.71 MPa to 1.37 MPa at 5 days without drilling and to 1.29 MPa at 50 days, a decrease of 24.7%. When drilling was performed, the average gas pressure decreased from 1.71 MPa to 1.29 MPa at 5 days and to 1.16 MPa at 50 days, a decrease of 32.2%. For 8# coal seam, the average gas pressure decreased from 1.56 MPa to 1.18 MPa at 5 days without drilling and 1.08 MPa at 50 days, a decrease of 30.8%, while the average gas pressure decreased from 1.56 MPa to 1.06 MPa at 5 days with drilling and 0.96 MPa at 50 days, a decrease of 38. 5%. This was because a large amount of gas desorbed and diffused after the protective coal seam was mined. When no drilling was arranged for extraction, the free state gas was transported to the mining area only under the action of the pressure gradient after mining, and the transport speed was slow, while after arranging extraction drilling, the gas in the coal seam was rapidly reduced under the action of negative pressure of extraction, and the average gas content of the coal seam rapidly decreased. Extraction of gas using boreholes can make good use of the pressure relief effect of protective coal seam mining and greatly improve the rate of gas extraction.

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, after mining the protective layer, the stress in the protected coal seam is effectively released, demonstrating significant stress relief effects. As the working face advances continuously, the stress relief zone of the protective layer and the induced seepage field gradually expand, indicating that mining the protective layer can continuously improve the permeability conditions of adjacent layers both spatially and temporally. The fundamental reason lies in the redistribution of stress within the coal-rock mass during face advancement. Localized stress concentrations are released, causing the coal body to transition from a compacted state to a damaged failure state. Fractures expand and interconnect, leading to a marked increase in permeability and enhanced gas permeability. The subsequent gas desorption converts adsorbed gas into free gas, which migrates toward the goaf driven by pressure gradients, as shown in Fig. 22.

Simulation results indicate that relying solely on pressure relief from protective layer mining cannot completely eliminate the risk of outbursts. This is because, while protective layer pressure relief significantly improves coal permeability, its effects are limited: on one hand, the pressure relief and permeability enhancement have spatial boundaries, making it difficult to cover the entire area; on the other hand, its effective timeframe is limited. If gas extraction is not performed promptly, gas desorption may still lead to localized accumulation. Therefore, to more efficiently reduce coal seam gas content, it is necessary to rationally arrange drilling and extraction operations on top of the pressure relief achieved through protective layer mining, thereby fully leveraging the permeability enhancement effect brought by protective layer mining. Drill hole design must comprehensively consider spatial and temporal effects: Spatially, it should integrate the vertical stress relief range of the mining area with the gas extraction radius, taking into account coal seam burial depth, drilling conditions, and roadway layout to determine optimal locations for bottom extraction roadways, as well as drill hole spacing and arrangement patterns. Temporally, drill holes should be pre-arranged before protective layer mining to enable efficient extraction during the critical time window when the coal body enters the decompression permeability enhancement phase, thereby maximizing gas control efficiency.

The simulation results of this study not only provide theoretical support for the gas migration and production mechanism under protective layer mining conditions but also offer important references for optimizing integrated stress relief, permeability enhancement, and gas extraction technologies. By precisely grasping the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the stress relief process, field operations can be guided to achieve precise layout and timing control of gas extraction projects, demonstrating clear practical value for promoting the safe and efficient mining of deep coal seams.

Conclusions

In order to investigate the pressure-relief and permeability-enhancement effects of protective layer mining, this study, based on the actual engineering geological conditions of the mine, establishes a coal–rock mass damage–seepage coupling model and carries out numerical simulations, from which the following main conclusions are obtained:

-

(1)

Under different primary mining conditions, gas pressure in the protected layer decreased, though the magnitude varied. When the 8th coal seam was initially mined, the pressure relief effect was limited. Although the 4th coal seam provided good protection for the lower coal seams, its effect on the upper coal seams was insufficient. When the 6th coal seam was initially mined, the pressures in the 4th and 8th coal seams decreased by approximately 52.6% and 71.6%, respectively. Both the adjacent upper and lower coal seams achieved significant pressure relief, indicating that the 6th coal seam is the optimal choice for the initial mining layer.

-

(2)

As the protective seam working face advanced, the stress and seepage field of the protected seam gradually expanded, manifested as continuous extension of the vertical stress relief zone and gas content reduction zone. The maximum stress relief in the 8th seam reached approximately 60%, with the maximum gas content reduction at about 45.9%, indicating more pronounced pressure relief effects on the upper seam from protective seam mining.

-

(3)

Relying solely on protective layer mining cannot fully achieve outburst prevention objectives. Integrating borehole extraction measures allows full utilization of mining space and time effects to significantly enhance extraction efficiency. For instance, after 50 days of extraction, gas content in the 4th coal seam decreased by over 80%, while that in the 8th coal seam decreased by nearly 99%, indicating that borehole extraction efficiency is closely related to the degree of coal seam decompression.

-

(4)

The damage-seepage coupling model developed in this study effectively captures stress redistribution, fracture propagation, and gas migration characteristics during protective layer mining. However, the model simplifies coal seam heterogeneity and complex geological structures, with certain parameters relying on experimental fitting, thus presenting limitations. Future research will integrate field measurements with multi-source parameter inversion methods to enhance model accuracy. Incorporating more complex tectonic structures and multi-field coupling mechanisms will provide a more reliable theoretical basis for gas control in coal seam groups.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Nie, B. S. et al. Micro-scale mechanism of coal and gas outburst: A preliminary study. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 51(2), 207–220 (2022).

Cao, J. Analysis of the statistical laws and dynamic effect characteristics of coal and gas outburst accidents in China in recent 10 years. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 51(3), 36–42 (2024).

Zhang, C. L. et al. Spatial-temporal distribution of outburst accidents from 2001to 2020 in China and suggestions for prevention and control. Coal Geology & Exploration 49(4), 134–141 (2021).

Yuan, L. et al. Research progress of coal and rock dynamic disasters and scientific and technological problems in China. J. China Coal Soc. 48(5), 1825–1845 (2023).

Chen, X. X. et al. Mechanism and quantitative traceability of anomalous out-flow of unloaded gas from protective layer mining under complex tectonics. J. China Coal Soc. 50(5), 2509–2526 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Influence of key layers on the protective effect of protection layer mining under sharp slopes[J]. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 40(1), 23–28 (2011).

Wang, H. F. et al. Study on the extension of the protection range of protected layer and continuous mining technology. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 30(4), 595–599 (2013).

Liu, Y. K., Wen, X. J. & Jiang, M. J. Study on the distribution and evolution characteristics of fracture field in overlying coal seam under double protection layer mining conditions. J. Xuzhou Eng. Coll. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 35(01), 12–18 (2020).

Lin, Y. K. et al. An experimental and numerical investigation on the deformation of overlying coal seams above double-seam extraction for controlling coal mine methane emissions[J]. Int. J. Coal Geol. 87(2), 139–149 (2011).

Liu, Y. K. et al. An investigation of the key factors influencing methane recovery by surface boreholes. J. Min. Sci. 48(2), 286–297 (2012).

Liu, Y. K. Research on pressure relief characteristics of remote lower protection layer mining and drilling and extraction to eliminate protrusion. J. China Coal Soc. 37(06), 1067–1068 (2012).

Ma, J., Hou, C. & Hou, J. Numerical and similarity simulation study on the protection effect of composite protective layer mining with gently inclined thick coal seam. Shock Vib. 2021, 6679199 (2021).

Cheng, Z. H. et al. Experimental study on the dynamic evolution characteristics of mining stress-fracture in close coal seam group stacked mining. J. China Coal Soc. 41(02), 367–375 (2016).

Hou, J. J. et al. Overburden fracture evolution and pressure relief gas extraction in superimposed coal seam group mining. Coal Eng. 56(09), 78–85 (2024).

Zhou, Y. B. et al. Gas enrichment law of overburden rock under the influence of double mining in the underlying protected layer[J]. Ind. Min. Autom. 46(04), 23–27 (2020).

Kou, J. X. et al. Research on pressure relief effect of overlapping mining on large spacing protective layer. Coal Mine Saf. 51(09), 179–186 (2020).

Ren, Z. H. et al. Overlying rock movement law of long-distance multi-coal overlapping mining under the action of coal pillars. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 40(1), 7–13 (2021).

Cheng, X. et al. Mining-induced pressure-relief mechanism of coal-rock mass for different protective layer mining modes. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 3598541 (2021).

Niu, X. et al. Stress distribution and gas concentration evolution during protective coal seam mining. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 6644142 (2021).

Yang, W. et al. Mechanism of strata deformation under protective seam and its application for relieved methane control. Int. J. Coal Geol. 85(3–4), 300–306 (2011).

Li, C. Study on the temporal and spatial effect of the relief pressure of upper protective layer mining[C]//MATEC web of conferences. EDP Sci. 100, 03038 (2017).

Yin, W. et al. Mechanical analysis of effective pressure relief protection range of upper protective seam mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27(3), 537–543 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Stress distribution characteristic analysis and control of coal and gas outburst disaster in a pressure-relief boundary area in protective layer mining. Arab. J. Geosci. 10(16), 1–15 (2017).

Yuan, B. Q., Zhang, Y. J., Cao, J. J., et al. Study on Pressure Relief Scope of Underlying Coal Rock with Upper Protective Layer Mining. Advanced Materials Research. 734, 661–665, Trans Tech Publications Ltd, (2013).

Yue, J. W. et al. Law of water migration during spontaneous imbibition in loaded coal and its influence mechanism. J. China Coal Soc. 47(11), 4069–4082 (2022).

Yue, J. W. et al. Gas desorption characteristics in different stages for retained water infiltration gas-bearing coal and its influence mechanism. Energy 293, 130688 (2024).

Lin, B. Q., Liu, H. & Yang, W. Establishment and application of a multi-field coupling model for coal seams based on dynamic diffusion. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 47(1), 32–40 (2018).

Kang, H. P. et al. Database and characteristics of underground in-situ stress distribution in Chinese coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 44(1), 23–33 (2019).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52274193), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M741846), and the Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (242102321172). The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the above-mentioned funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J. conceived the research idea. W.M. designed the methodology. Y.B. reviewed and revised the initial draft. S.L. and P.Z. wrote the original manuscript. W.Z. visualized the experimental results. C.Z. verified the experimental design. Y.B.Q. curated the data. P.Z. also performed the final checks. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jianguo, Z., Man, W., Banghua, Y. et al. Study of the mechanism of enhanced gas extraction by pressure relief and permeability enhancement in protective mining in a coal seam group. Sci Rep 15, 41790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25680-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25680-3