Abstract

Cancer is the plague of the 20th and 21st centuries, affecting sick individuals, their families, and entire micro- and macro-communities. Despite the efforts of scientists to search for new diagnostic and therapeutic methods, the statistics regarding cases of illness and deaths are becoming more and more alarming. Therefore, it is extremely important to look for theranostic tools that enable the initiation of therapy during the diagnostic process. Theranostics involves the use of a tool that is one construct that simultaneously performs two functions: imaging (diagnostics) and selective cytotoxicity towards cancer cells (therapeutics). Currently, due to its low invasiveness and extremely high sensitivity, fluorescence imaging is attracting attention in the development of theranostics. Therefore, the impact of structural modifications on the biological activity of fluorescently labeled isothiocyanate (ITC) derivatives was designed, synthesized and studied. The covalent combination of a fluorescent marker enabling imaging and an isothiocyanate group responsible for biological activity, connected via a linker, allowed for obtaining constructs with high application potential, which combine diagnostic and therapeutic functions. To verify the therapeutic potential of the synthesized derivatives, the influence of the type of fluorophore and the length of the linker on the anticancer effect of ITC group was examined. Moreover, the ability of the obtained compounds to pass through the cell membrane and their retention time in the cell after penetration were monitored to verify their diagnostic potential. Model cell lines of breast cancer (T47D) and prostate cancer (PC3) were used to study the activity. Healthy dermal fibroblast cell line (HDFa) was used to test selectivity. The reference compound used was sulforaphane (SFN), one of the best-studied active ITC derivatives. During the research, it was found that all compounds have higher anti-cancer activity than the reference compound. The anticancer activity depends on both the type of fluorophore and the length of the linker. The most active compound has an IC50 value that is over 30 times lower for prostate cancer cells and almost 30 times lower for breast cancer cells than SFN. Studies of the anticancer activity of the synthesized analogues allowed us to conclude that the ITC group is responsible for the activity of these compounds, while the presence of a fluorophore enhances it. Moreover, it was found that all tested compounds penetrate the cell membrane. The accumulation of the dye in the cell was visible after 5 min of treatment with compounds at low concentrations. Moreover, after removing the dye from the medium, cell fluorescence could be recorded even after 24 h at higher contrast. The research confirmed that compounds combining potential diagnostic and therapeutic functions were obtained. Therefore, fluorescently labeled ITC derivatives represent super promising theranostic tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensitive methods for monitoring both the human body and its environment are critically important for ensuring public health and safety. For many years, oncologists have described that cancer is the plague of the 20th and 21st centuries. This is supported by statistics showing cancer as the second leading cause of premature death worldwide. It is estimated that within the next 10 years, cancer will be the most common cause of death among people under the age of 65. Current statistics reveal that women in this age group already die twice as often from cancer as from cardiovascular diseases. In the fight against cancer, both therapy and diagnosis play crucial roles. However, early diagnosis is highlighted by the WHO as one of the key factors limiting mortality from cancer. Therefore, the search for theranostic tools that enable simultaneous diagnosis and therapy is of paramount importance.

Among the instrumental techniques with high application potential in medicine, fluorescence spectroscopy is recognized as one of the most sensitive. Its high sensitivity enables working with very small amounts and detecting even subtle changes in the system under study. Among fluorescence-based methods, fluorescence microscopy is particularly valuable for studying biological systems. Fluorescence imaging of cells allows tracking the fate of the labeled object in real time. From a biological perspective, a fundamental requirement for using a fluorophore in cell imaging is its ability to penetrate cells. An additional prerequisite for imaging living cells is the low cytotoxicity of the fluorophore when it is intended solely for diagnostic purposes. However, high but selective cytotoxicity towards aberrant cells allows the fluorophore to be used for combined diagnostics with therapy (theranostics).

Fluorescence of biologically active compounds enables tracking of migration paths of compounds in the analyzed system, visualization and analysis of objects in which accumulation of fluorophore occurs, which can be helpful in diagnostics and in the study of the mechanism of action. An example of a compound showing both fluorescence and anticancer activity is doxorubicin (DOX), an anthracycline antibiotic that has been used since the 1970’s1,2,3 for the treatment of leukemia, ovarian, prostate, brain and lung cancers, and in particular breast cancer2,4. The fluorescence quantum yield of Dox is low; however, due to the extreme sensitivity of fluorescence techniques, Dox is detectable even at nanomolar concentrations. Dox penetrates cells by passive diffusion and accumulates in the nuclear compartments5. The mechanism of Dox action is based on the intercalation of the compound into the DNA, inhibition of topoisomerase II and impairment of DNA synthesis6. In addition, doxorubicin generates free radicals that damage DNA and the cell membrane7. Unfortunately, Dox is not selective for cancer cells. It also damages the healthy cells and organs of the patient undergoing therapy, disrupting the heart, brain, kidneys and liver. Due to the wide-ranging side effects, this fluorescent drug is not used as a theranostic tool, but it is still used as a therapeutic, despite the disadvantages described above. Therefore, the search for new selective and effective diagnostic, therapeutic and theranostic tools is extremely important as it might give a chance for longer lives of cancer patients.

ITCs are known for their selective anti-cancer activity8. Research on this promising group of compounds has been ongoing for many years but to the best of our knowledge, no one has yet elucidated how their activity will be affected by the presence of a covalently attached fluorophore, which would enable the use of fluorescence spectroscopy for studying the mechanism of action of these compounds, and perhaps their use for diagnostic combined with therapeutic purposes, i.e. in theranostics. One of the best-known representatives of ITCs is sulforaphane (SFN). It is present in many edible vegetables, such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts or cauliflower9. Its chemopreventive and anticancer properties have been confirmed in a variety of experimental models. Animal studies have shown that SFN reduces the incidence of chemically induced breast cancer and retards tumor growth at the stages of initiation, promotion and progression of carcinogenesis10. It also inhibits the process of angiogenesis as well as the incidence of metastases. Importantly, SFN is quite selective for cancer cells and does not cause side effects in animals.

We decided to design, synthesize and study fluorescently labeled SFN analogues to obtain innovative compounds - biologically active ITCs with intrinsic fluorescence. The application potential of such compounds is considerable. They can be used for cellular imaging and for quantifying the amount of the compound within cells, tissues and physiological fluids through straightforward fluorescence microscopy or spectroscopy measurements. In addition, analysis using fluorescence spectroscopy enables real-time tracking of compounds and is a safe alternative to radioactive labeling. However, since SFN is a small molecule, the inclusion of the fluorophore significantly modifies its structure. Therefore, in the presented study, we synthesized a set of analogs that allowed us to determine whether the presence and type of fluorophore and the length of the linker connecting the fluorophore with the active group affect the biological activity. Moreover, the synthesis of control compounds for the designed analogs made it possible to verify the importance of individual structural elements of the synthesized derivatives for their biological activity.

Result and discussion

Chemical synthesis

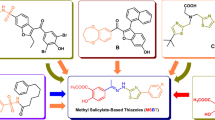

To carry out the planned studies, fluorescently labeled SFN analogs were synthesized using commercially available or home-modified markers. The effect of the fluorophore on the activity of SFN analogs has been studied based on ITC derivatives containing four carbon atoms in the chain (similar to SFN) and various fluorophores, i.e. 7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD), 5-(dimethylamino)naphtalene (DNS), 9,10-dihydroacridone (Akr), and 10-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridone (MeAkr) linked to the carbon chain by a nitrogen atom. Moreover, a selected ITC derivative containing two additional methylene groups in the carbon chain and NBD fluorophore was synthesized to study the effect of chain length on the biological activity. To investigate the influence of the above-mentioned structural elements on biological properties, 5 derivatives (Fig. 1) were synthesized. For a more detailed description of synthesis, see ESI. The identity of the compounds was confirmed by MS and 1H NMR spectra. Details are provided in ESI (Fig. S1-S10). The synthesis and studies of analogs not containing a fluorescent marker in their structure allowed to verify whether the presence of a fluorophore affects the activity of ITC derivatives. In this control group of compounds, in place of a fluorophore, mesyl and tosyl substituents were introduced (Fig. 2). For a more detailed description of synthesis conditions, see ESI. The identity of the compounds was confirmed by MS and 1H NMR spectra. Details are provided in ESI (Fig. S11-S14). To verify whether the ITC group is responsible for the anticancer activity of the obtained derivatives, analogs of fluorescently labeled derivatives containing four carbon atoms in the chain with an N-acetyl group instead of an ITC group were synthesized. In this control group, analogs of all the previously used fluorescent markers were synthesized (Fig. 3). For a more detailed description of synthesis conditions, see ESI. The identity of the compounds was confirmed by MS and 1H NMR spectra. Details are provided in ESI (Fig. S15-S22).

To identify suitable conditions for cellular imaging, such as excitation and emission ranges using the tested derivatives, absorption and fluorescence spectra were measured to determine the longest-wavelength absorption and emission peaks. The data in Table 1 were recorded in PBS buffer, which has a pH of 7.4, corresponding to physiological conditions, and therefore reflect values under these conditions.

The purity of the studied compounds was verified using qualitative analyses of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (LC-20AD, Shimadzu) and is over 95% (chromatograms for all compounds are included in ESI Fig. S23-S33).

Biological activity

Fluorescent derivatives of Sulforaphane are active against cancer cells

To determine whether a fluorophore conjugation to ITC group affects its biological activities, the impact of the derivative with NBD fluorophore (NBDC4NCS) on model cancer cells of the prostate (PC3 cell line) and breast (T47D cell line) was investigated by MTT test. Cells treated with a vehicle (DMSO) served as a negative control, whereas those treated with SFN – as a reference. Viability of control cells (0 µM) treated with pure vehicle (DMSO) was taken as 100%. The diagrams show the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance of differences was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

After 24 h of treatment, NBDC4NCS effectively reduced the viability of both prostate (PC3) and breast (T47D) cancer cells and, noteworthy, to a significantly greater extent than the reference compound – SFN (Fig. 4). While IC50 values for SFN were 33.5 µM and 30.4 µM for PC3 and T47D cell lines, respectively, for NBDC4NCS were 3.3 µM and 2.8 µM, respectively (Table 1). Thus, for both tested cancer cell lines, the NBDC4NCS derivative causes a 50% reduction in viability at a concentration ~ 10 times lower than SFN. We also confirmed the accumulation of the derivative inside prostate cancer cells by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4C).

The viability of model cancer cells of the prostate (PC3) (A) and breast (T47D) (B), and normal cells (HDFa) after treatment with increasing concentrations of NBDC4NCS (D) or SFN (E) for 24 h; C. Accumulation of NBDC4NCS in prostate cancer cells (PC3) after 24 h of treatment (at a concentration of 3.5 µM), determined by fluorescence microscopy after excitation of the sample fluorescence (FLUO; Em/Ex: 450–490/500–550 nm; lower panel). DIC - differential interference contrast (upper panel). The scale bar is 50 μm.

Due to the fact that the selectivity aspect is extremely important, in the next step we examined the effect of NBDC4NCS derivative on the viability of normal cells - human dermal fibroblasts (HDFa). At concentrations close to IC50 for tested cancer cells (i.e. 3.3 and 2.8 µM; Table 2), the viability of fibroblasts was circa 70%. (Fig. 4D). The same viability (circa 70%) was obtained when fibroblasts were treated with the reference agent at concentrations close to its IC50 for prostate and breast cancer cells (33.5 and 30.4 µM, respectively; Table 2; Fig. 4E). Thus, NBDC4NCS derivative, despite increased anti-tumor activity, remains selective for cancer cells to the same extent as SFN.

To deepen our investigation on the impact of fluorophore conjugation on derivatives’ activity, we tested analogs with the same carbon chain and ITC group but conjugated with different fluorophores: MeAkrC4NCS, DNSC4NCS and AkrC4NCS. Their anticancer activity against prostate and breast cancer cells was tested by the MTT test (Fig. 5A-F) and the obtained IC50 values are shown in Table 1. Their analysis indicated that the type of particular fluorophore has a strong impact on the activity of the compound (for example, the IC50 value in prostate cancer cells for the DNSC4NCS was 16.8 µM and for MeAkrC4NCS − 4.0 µM; Table 2), however, the anticancer activity of fluorescent derivatives is similar (AkrC4NCS) or higher (other derivatives) than of the original agent – SFN. We also confirmed an accumulation of the derivatives inside prostate cancer cells by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5G).

Viability of prostate (PC3) (A, B, C) and breast (T47D) (D, E, F) cancer cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of SFN or MeAkrC4NCS, DNSC4NCS or AkrC4NCS for 24 h; G. Prostate cancer cells (PC3) were treated for 24 h with fluorescent sulforaphane derivatives, MeAkrC4NCS (7.5 µM), DNSC4NCS (20 µM) and AkrC4NCS (20 µM), then observed under a fluorescence microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC; left panel) or after excitation of samples fluorescence (FLUO: Ex/Em: 340–380 nm/450–490 nm; right panel). The scale bar is 50 μm.

Next, we investigated the impact of the derivatives on the viability of normal cells (Fig. 6) which appeared more resistant to tested agents than cancer cells.

However, since the range of concentrations effectively reducing cell viability varies significantly between the tested compounds, it is difficult to compare whether the shift of the IC50 values between cancer cells and healthy cells is similar, smaller or larger than the reference compound, sulforaphane. To enable such a comparison, we introduced a selectivity index (SI, Eq. 1). The obtained results indicated that the fluorescently labeled SFN derivatives are selective toward cancer cells, as their SI values are greater than 1. Moreover, they show higher selectivity than the reference compound, SFN (Table 2; Fig. 7).

The selectivity index for fluorescent SFN derivatives was calculated according to Eq. 1. The dashed line indicates the level of selectivity of the reference compound - SFN.

To verify whether the observed effect of the derivative on cell viability depends on the presence of the ITC group or results solely from the biological activity of the fluorophore, experiments using fluorescent analogs lacking an ITC group (-N = C = S) which was replaced with N-acetyl substituent (Fig. 3) were performed. The absence of the ITC group resulted in the complete elimination of the anticancer properties of the compounds in both cancer cell lines irrespective of the type of conjugated fluorophore (Fig. S34).

Moreover, the anticancer activity of derivatives where fluorophore was replaced with mesyl (MesC4NCS) or tosyl (TosC4NCS) group was tested and compared to fluorophore-conjugated derivative, NBDC4NCS (Fig. S35). Both of the agents retained anticancer properties, however, their impact on cancer cell viability was much lower than fluorophore-containing derivatives (Table 3).

In the next step, we addressed a question of the impact of aliphatic chain length on the anticancer activity of fluorescent derivatives. Comparison between derivatives with 4- and 6-carbon atom chains (NBDC4NCS and NBDC6NCS, respectively) showed that extending the aliphatic chain from 4 to 6 carbon atoms significantly increased the anticancer activity of the compound (Fig. S36; Table 2). Its selectivity was also greater than that of SFN (Fig. 7).

Summarizing, the obtained results indicate that the ITC group is responsible for the anti-cancer activity of fluorescent derivatives, while the presence of the fluorophore and the length of the carbon chain potentiate this activity.

Fluorophore tagging of SFN derivatives enables their tracking in a cell

The idea underlying tagging SFN derivatives with fluorophores was to enable easy analysis of their accumulation and localization in a cell by fluorescent microscopy. Representative images in Figs. 4C and 5G proved that, indeed, all tested fluorescently labeled SFN derivatives can be easily detected inside cells. In addition, the fluorescent properties of the derivatives enable the monitoring and ratiometric determination of the rate of their accumulation in cells based on the fluorescence intensity as well as the determination of the subcellular localization of compounds. In PC3 prostate cancer cells treated with NBDC4NCS for increasing periods of time, the presence (fluorescence) of compounds inside cells was detectable already after 5 min and increased concomitantly with the time of treatment, indicating accumulation of compounds inside cells (Fig. 8). It is noteworthy that initially, in addition to the cytoplasm, the compounds accumulated particularly in mitochondria-like cellular structures (Fig. 8B), suggesting that these organelles may be one of the main targets of ITCs in a cell. With a longer exposure time, the derivative was also observed in the nucleus and vesicular structures.

Accumulation of fluorescent SFN derivatives in cells shown on the example of NBDC4NCS and PC3 prostate cancer cells analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. A. Cells were treated with a 3.5 µM NBDC4NCS for the indicated time, then washed and observed in a fluorescence microscope under white light using differential interference contrast (DIC) or fluorescence (FLUO; Ex/Em: 450–490/500–550 nm). B. Image, enabling observation of the subcellular localization of NBDC4NCS, is an enlargement of the framed fragment. The bar is 50 μm.

Further, we demonstrated that differences in the concentration of the derivatives inside cells can be easily detected by fluorescence microscopy. Prostate and breast cancer cells were treated for 1 h with different concentrations of NBDC6NCS, which led to a dose-dependent fluorescence intensity (Fig. 9).

Accumulation of fluorescent SFN derivatives in cells shown on the example of NBDC6NCS and PC3 prostate (A) and T47D breast (B) cancer cells. Cells were treated with NBDC6NCS at the indicated concentrations for 1 h, washed and observed in a fluorescence microscope under white light with differential interference contrast (DIC; left panel) or fluorescence (Ex/Em: 450–490/500–550 nm; right panel).

We also investigated whether fluorescent properties of derivatives can be used to monitor retention of the compounds inside a cell by fluorescence microscopy. For this, T47D cells were treated with 2.5 µM NBDC6NCS for 5 min, then washed and cultured in normal (the compound-free) medium for up to 24 h. Cell fluorescence was significantly decreased 30–60 min after washout, indicating NBDC6NCS removal due to its degradation and/or efflux from cells. However, it was detectable even after 24 h and still observed in mitochondria in particular (Fig. 10).

Cells fluorescence: (1) before treatment; (2) after treatment with 2.5 µM NBDC6NCS; (3) after washout and further culturing the cells in compound-free medium for an indicated period of time. The fluorescence intensity in the cells was monitored using a fluorescence microscope (Ex /Em: 450–490 nm/500–550 nm). The fluorescence image of the cells after 24 h with increased contrast proves that the compound is still present in the cells even 24 h after treatment. Bar is 50 µM.

Conclusions

This project aimed to verify the properties and application potential of new fluorescently labeled ITC derivatives. The influence of the selected fluorophore and the structure of the aliphatic chain - the linker between the fluorophore and the ITC group - on the selectivity and antiproliferative activity of the synthesized compounds was investigated. Moreover, it was verified whether the obtained conjugates enable monitoring the rate of compound accumulation, determining their localization and their retention in cells using fluorescence microscopy. Presented results allow us to conclude that SFN derivatives coupled with fluorophores retain biological activity and exhibit anticancer properties even better than the original agent – SFN. Since both, structure of an aliphatic chain as well as the type of attached fluorophore significantly modify the properties of obtained derivatives, it might be suspected that increased knowledge about this effect might allow for designing in the future “a supermolecule” with increased anticancer potency as well as selectivity.

It is worth emphasizing that in addition to the potential application of selected derivatives as improved anticancer agents, due to the presence of a fluorophore in their structure, they can be used as a unique tool for studying the mechanisms of ITC activity in cells and whole organisms. Such compounds have enormous research and implementation potential through a wide range of possible applications, including real-time monitoring of their accumulation inside cells, their half-life in a cell or organism, the rate of their removal with urine, penetration into tissues or crossing the blood-brain barrier, etc. These compounds are part of a new medical trend, constituting potential fluorescent theranostic probes. They meet the premise of theranostic tools in which both components, the one performing a diagnostic role (imaging using a fluorophore) and the one performing a therapeutic function (anti-cancer activity of the ITC group), are combined into one construct11.

Publications indicate that in vitro and in vivo studies on ITC derivatives and SFN itself discover new properties of these compounds, increasing their application potential in the treatment of cancer, including prostate, breast, ovarian, lung, colon and gastric cancers12,13,14,15,16 and also others, such as neurodegenerative diseases (for instance Parkinson’s disease). It has also been suggested that SFN is an effective inhibitor of cancer stem cells (CSC) of various cancers17, including but not limited to leukemia18, lung19,20, breast12,21, prostate22,23,24, colon25,26, gastric27,28 and pancreatic29,30,31,32 cancers. The therapeutic usefulness of SFN as a sensitizer or synergistic agent in combination with chemotherapeutic agents was also reported. For instance, combinations of SFN with DOX33,34, nanometformin35, quercetin31, cisplatin, DOX, gemcitabine, 5-flurouracil29, curcumin, dihydrocaffeic acid36 have been shown effective. However, the combination of components described above is not covalent and involves simultaneous application.

Although currently fluorescence imaging is gaining attention in the context of theranostic development37,38,39, there are no reports on the synthesis and study of a fluorophore covalently bound with ITCs, so this approach and studied fluorescently labeled ITC derivatives are innovative and unique on a global scale and have extremely wide application potential. Our research indicates that when looking for such a super molecule with theranostic potential, the ITC group is a good choice, and among the fluorophores tested, the suggested choice would be NDB. This fluorophore has many advantages and is often used as a sensor of small molecules and proteins in biological systems. The results of our research coincide with the predictions of Yi and other co-authors, who suggest that NBD-based probes will become extremely important tools in the study of biological mechanisms as well as in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases40. The combination of the fluorophore with the linker by the C-N bond used by us is safe and stable. Connections of this type are stable under reducing conditions, in the presence of glutathione and hydrogen sulfide. This is evidenced by the observed fluorescence of these compounds even after 24 h of treatment. Also literature data confirm the stability of NBD-NH-R connections in the presence of H2S tested in vivo41. In contrast to connection NBD-O-R (ether) or NBD-S-R (thiol), which are not stable under reducing conditions. The instability of such (NBD-O-R and NBD-S-R) bonds is used to detect H2S in living cells42,43,44,45. Moreover, these unstable thioether and thiol systems often transform into -NH-NBD systems upon contact with a trigger, which indicates the stability of the NBD bond via the secondary nitrogen atom used by us46,47,48,49.

The combination of a structural fragment exhibiting selective anticancer activity (ITC group) and a fluorescent probe (e.g. NBD) has proven to be effective. Both fragments have retained or even improved their properties, and when combined into one construct, they create a system with extended application potential. Combining a fragment with therapeutic potential with a specific type of flashlight (fluorophore) allows for real-time drug imaging and enables initiation of therapy during the diagnostic process.

Our results indicate that a combination of ITC group with a fluorophore increases activity and selectivity of such compounds toward cancer cells; however it should be noted that the effect of obtained compounds on cell viability was investigated after 24-h exposure. Further research, with longer treatment times and investigation of mechanisms underlying the activity of presented derivatives in vitro and in vivo, is essential for discovering their full potential.

In conclusion, fluorescently labeled ITC derivatives presented in this work constitute promising new tools in the hands of scientists and medics, may contribute to the development of theranostics, and give patients hope for successful treatment.

Methods

General chemistry materials and methods

All general reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used as supplied.

Commercially available dansyl chloride and 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan were used in the synthesis, while 9,10-dihydroacridone sulfochloride and 10-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridone sulfochloride were home-made by methylation of 9,10-dihydroacridone (9,10-dihydroacridone 1 eq, iodomethane 1.2 eq, silver oxide 1 eq, THF/DMF, 70 °C), and sulfonation of 9,10-dihydroacridone and its methyl derivative (9,10-dihydroacridone/10-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridone 1 eq, chlorosulfuric acid 10 eq). For the synthesis of fluorescently labeled sulforaphane analogs, diamino derivatives containing a four- and six-carbon chain, respectively, were used, in which one of the functional groups had a protecting group - tert-Butyloxycarbonyl (Boc). In the first step of the planned synthesis pathway, a fluorophore was attached to the unprotected amine group (a). The conditions of these reactions depended on the chosen fluorophore derivative (A, B, C). The Boc protecting group was then removed by a standard method (dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) 1:1 (v/v)) (b) and then amino group was converted to an isothiocyanate group using carbon sulfide (CS2) (10 eq) and 2-(1 H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate; HBTU) (1 eq) (c)50(Fig. 11).

Pathway for the synthesis of planned fluorescently labeled isothiocyanate derivatives. Structures of fluorophore derivatives (fluorophore-Cl), which are substrates in the synthesis of fluorescently labeled isothiocyanate derivatives (sulforaphane analogs). The conditions of the corresponding reactions are pointed out as A, B or C. NBD-Cl 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan; DNS-Cl 5-(dimethylamino)naphthalene-1-sulfonyl chloride; Akr-Cl 9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridine-2-sulfonyl chloride; MetAkr-Cl 10-methyl-9-oxo-9,10-dihydroacridine-2-sulfonyl chloride.

The progress of all reactions was monitored by TLC (Kieselgel 60 F254, Merck). Column chromatography was performed with silica gel 60 (particle size 0.040–0.063 μm) with the mobile phase as specified. The purity of the compounds was over 95% and was verified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) qualitative analyses (LC-20AD, Shimadzu) on a reverse-phase column (250 mm long, i.d. 4.6 mm; Supleco Discovery Analytical column) containing C-8 material (5 μm particle size). Elution was performed at a flow rate of 1 ml / min under the linear gradient of the mixture of the two solvent systems A and B in 60 min (0-100% B), where A is water with the addition of TFA (0.1%) and B is 80% acetonitrile in water with the addition of TFA (0.08%). Before each injection, the column was equilibrated in system A for at least 15 min. The analysis was monitored using a photodiode array detector (SPD-M20A; Shimadzu) over the range 190 to 800 nm. The identity of the compounds was confirmed using a mass spectrum obtained with a Bruker Daltonics HCT Ultra spectrometer with ion trap electrospray ionization (a) or HiRes TripleTOF 5600 + AB SCIEX spectrometer (b) or Shimadzu LCMS-ESI-IT-TOF spectrometer (c) and using 1H NMR spectra in specified solvent recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III (500 MHz) spectrometer. A detailed description of the syntheses and characterization of all the obtained derivatives is included in the ESI (The 1H NMR spectra were recorded over the full chemical shift range (0–12 ppm). For the sake of clarity and readability, the spectrum is shown up to 10 ppm when no additional signals are present (Figs. S2, S4, S6, S8, S10, S12, S14, S16, S18, S20, S22)).

General biology materials and methods

Reagents

D, L-SFN (99% purity) was purchased from LKT Laboratories. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture, and trypsin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Thermo Scientific. Culture media was purchased from Corning Life Sciences.

Cell lines and cell culture

Human dermal adult fibroblasts (HDFa) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Product Line Cascade Biologics™). Prostate cancer PC3 cells were kindly provided by Prof. Danuta Duś (Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences). Breast cancer T47D cells were obtained from Cell Line Service (CLS).

Monolayer cultures of prostate cancer cells (PC3 cell line) were maintained in F12-K Nutrient Mixture medium supplemented with 8% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Human dermal adult fibroblasts (HDFa) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Breast cancer cells (T47D cell line) were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Each cell line was maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. D, L-SFN and tested derivatives were prepared in DMSO at a stock concentration of 0,5–100 mM and stored at -20°C. Control cells were treated with an equal amount of pure DMSO (final concentration 0,1%).

MTT test

The MTT test indirectly measures the number of viable, metabolically active cells in a sample, which is referred to as viability. Cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 10³ cells per well in a 96-well plate in triplicate and allowed to attach overnight. The medium was replaced with a fresh one supplemented with DMSO (0.1% v/v; control) or the indicated concentration of the tested compound for 24 h. After incubation, 25 µl of MTT solution (4 mg/ml in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for a further 3 h. Next, the medium was removed and formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µl of DMSO. The absorbance of the solutions was determined spectrophotometrically at 570 nm and 660 nm (reference) with a plate reader (Victor³, Perkin Elmer). The absorbance of the control cells was taken as 100%. The experiment was performed in at least three independent replicates.

Analysis of the accumulation of compounds in cells by fluorescence microscopy

Prostate cancer cells (PC3 cell line) were plated on coverslips, incubated overnight and treated with fluorescently labeled sulforaphane derivatives for 5, 15, 30 and 60 min and/or for 24 h. Control cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO). After incubation, the cells were immediately washed with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analyzed under a Leica DMI4000B inverted fluorescence microscope under a 100x immersion oil-objective with appropriate filters (Ex: 450–490 nm/Em: 500–550 nm for NBD, Ex: 340–380 nm/Em: 450–490 nm for DNS, Akr and MeAkr) or in a differential interference contrast (DIC). Parameters of acquisition were set with a control (DMSO-treated cells) so that no autofluorescence was detectable (blank sample) and fixed throughout the entire experiment. The experiment was performed in at least two independent replicates.

Analysis of the retention of compounds in cells using fluorescence microscopy

Breast cancer cells (T47D) were plated on coverslips, incubated overnight and treated with 2.5 µM fluorescently labeled sulforaphane derivative – NBDC6NCS for 5 min. After this time, the medium containing the compound was removed, the cells were washed with warm sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and further cultured in standard medium (containing no test compound) for the designated times (15, 30, 60 min and 24 h). After the end of incubation, the cells were immediately washed with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analyzed under a Leica DMI4000B inverted fluorescence microscope under a 100x immersion oil-objective with appropriate filters (Ex: 450–490 nm/Em: 500–550 nm). Parameters of acquisition were set with a control (DMSO-treated cells) so that no autofluorescence was detectable (blank sample) and fixed throughout the entire experiment. The experiment was performed in at least two independent replicates.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Changenet-Barret, P., Gustavsson, T., Markovitsi, D., Manet, I. & Monti, S. Unravelling molecular mechanisms in the fluorescence spectra of doxorubicin in aqueous solution by femtosecond fluorescence spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (8), 2937 (2013).

Chen, N. et al. Probing the dynamics of Doxorubicin-DNA intercalation during the initial activation of apoptosis by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). PLoS One 7 (11), e44947 (2012).

Motlagh, N. S. H., Parvin, P., Ghasemi, F. & Atyabi, F. Fluorescence properties of several chemotherapy drugs: doxorubicin, Paclitaxel and bleomycin. Biomed. Opt. Express. 7 (6), 2400 (2016).

Piscitelli, S. C., Rodvold, K. A., Rushing, D. A. & Tewksbury, D. A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of doxorubicin in patients with small cell lung cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 53, 555 (1993).

Tacar, O., Sriamornsak, P. & Dass., C. R. An update on anticancer molecular Action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 65 (2), 157 (2013).

Momparler, R. L., Karon, M., Siegel, S. E. & Avila, F. Effect of adriamycin on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in cell-free systems and intact cells. Cancer Res. 36 (8), 2891 (1976).

Wang, S. et al. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB during doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells and myocytes is pro-apoptotic: the role of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J. 36, 729 (2002).

Oliviero, T., Verkerk, R. & Dekker, M. Isothiocyanates from brassica vegetables—Effects of processing, cooking, mastication, and digestion. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62, 1701069 (2018).

West., L. G. et al. Glucoraphanin and 4-hydroxyglucobrassicin contents in seeds of 59 cultivars of broccoli, raab, kohlrabi, radish, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kale, and cabbage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 (4), 916 (2004).

Clarke, J. D., Dashwood, R. H. & Ho, E. Multi-targeted prevention of cancer by Sulforaphane. Cancer Lett. 269 (2), 291 (2008).

Sharma, P. et al. Theranostic fluorescent probes. Chem. Rev. 124 (5), 2699 (2024).

Castro, N. P. et al. Sulforaphane suppresses the growth of triplenegative breast cancer stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev. Res. 12, 147 (2019).

Kan, S. F., Wang, J. & Sun, G. X. Sulforaphane regulates apoptosis- and proliferationrelated signaling pathways and synergizes with cisplatin to suppress human ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 42, 2447 (2018).

Zheng, Z. et al. Sulforaphane metabolites inhibit migration and invasion via microtubule-mediated claudins dysfunction or Inhibition of autolysosome formation in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cell. Death Dis. 10, 259 (2019).

Rutz, J., Thaler, S., Maxeiner, S. & Chun, F. K. H. Blaheta Sulforaphane reduces prostate cancer cell growth and proliferation in vitro by modulating the cdk-cyclin axis and expression of the CD44 variants 4, 5, and 7. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Sulforaphane induces sphase arrest and apoptosis via p53-dependent manner in gastric cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 2504 (2021).

de Lima Couthinho, L., Citrangulo Tortelli, T. Jr & Rangel, M. C. Sulforaphane: an emergent anticancer stem cell agent. Front. Oncol. 13, 1089115 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Sulforaphane regulates the proliferation of leukemia stem-like cells via Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 919, 174824 (2022).

Wang, D. X. et al. Sulforaphane suppresses EMT and metastasis in human lung cancer through miR-616-5p-mediated GSK3b/b-catenin signaling pathways. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 38, 241 (2017).

Chanvorachote, P., Sriratanasak, N. & Nonpanya, N. C-myc contributes to malignancy of lung cancer: A potential anticancer drug target. Anticancer Res. 40, 609 (2020).

Bagheri, M., Fazli, M., Saeednia, S., Gholami Kha-Ranagh, M. & Ahmadiankia, N. Sulforaphane modulates cell migration and expression of b-catenin and epithelial mesenchymal transition markers in breast cancer cells. Iran. J. Public. Health. 49, 77 (2020).

Peng, X. et al. Sulforaphane inhibits invasion by phosphorylating ERK1/2 to regulate e-cadherin and CD44v6 in human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Oncol. Rep. 34, 1565 (2015).

Vyas, A. R., Moura, M. B., Hahm, E. R., Singh, K. B. & Singh, S. V. Sulforaphane inhibits c- Myc-Mediated prostate cancer stem-like traits. J. Cell. Biochem. 117, 2482 (2016).

Traka, M. H. et al. Mithen transcriptional changes in prostate of men on active surveillance after a 12-mo glucoraphanin-rich broccoli intervention-results from the effect of Sulforaphane on prostate cancer prevention (ESCAPE) randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1133 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and mesenchymal States reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem Cell. Rep. 2, 78 (2014).

Martin, S. L., Kala, R. & Tollefsbol, T. O. Mechanisms for the Inhibition of colon cancer cells by Sulforaphane through epigenetic modulation of MicroRNA-21 and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) down-regulation. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 18, 97 (2018).

Ge, M. et al. Sulforaphane inhibits gastric cancer stem cells via suppressing Sonic Hedgehog pathway. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 70, 570 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Sulforaphane improves chemotherapy efficacy by targeting cancer stem cell-like properties via the miR-124/IL- 6R/STAT3 axis. Sci. Rep. 6, 36796 (2016).

Kallifatidis, G. et al. Sulforaphane targets pancreatic tumour-initiating cells by NF-kB-induced antiapoptotic signalling. Gut 58, 949 (2009).

Bernard, D., Quatannens, B., Vandenbunder, B. & Abbadie, C. Rel/NF-kB transcription factors protect against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis by up-regulating the TRAIL decoy receptor DcR1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27322 (2001).

Li, S. H., Fu, J., Watkins, D. N., Srivastava, R. K. & Shankar, S. Sulforaphane regulates selfrenewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells through the modulation of Sonic hedgehog-GLI pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 373, 217 (2013).

Srivastava, R. K., Tang, S. N., Zhu, W. & Meeker, D. Shankarn Sulforaphane synergizes with Quercetin to inhibit self-renewal capacity of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Front. Biosci. 3, 515 (2014).

Rutz, J., Thaler, S., Maxeiner, S., Chun, F. K. H. & Blaheta, R. A. Sulforaphane reduces prostate cancer cell growth and proliferation in vitro by modulating the cdk-cyclin axis and expression of the CD44 variants 4, 5, and 7. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1 (2020).

Rong, Y. et al. Co-Administration of Sulforaphane and doxorubicin attenuates Brest cancer growth by preventing the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Lett. 28, 189 (2020).

Keshandehghan, S., Nikkhah, H., Tahermansouri, S., Heidari-Keshel, M. & Gardaneh Co-Treatment with Sulforaphane and nano-metformin molecules accelerates apoptosis in HER2+ breast cancer cells by inhibiting key molecules. Nutr. Cancer. 72, 835 (2020).

Santana-Gálvez, J., Villela-Castrejón, J., Serna-Saldı́var, S. O., Cisneros-Zevallos, L. & Jacobo-Velázquez, D. A. Synergistic combinations of curcumin, sulforaphane, and dihydrocaffeic acid against human colon cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3108 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Optical molecular imaging for tumor detection and image guided surgery. Biomaterials 157, 62 (2018).

Gioux, S., Choi, H. S. & Frangioni, J. V. Image-guided surgery using invisible near-infrared light: fundamentals of clinical translation. Mol. Imaging. 9 (5), 7290 (2010).

Owens, E. A., Henary, M., El Fakhri, G. & Choi, H. S. Tissue specific near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Acc. Chem. Res. 49 (9), 1731 (2016).

Jiamg, C. et al. NBD-based synthetic probes for sensing small molecules and proteins: design, sensing mechanisms and biological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 7436 (2021).

Hartle, M. D. & Pluth, M. D. A practical guide to working with H2S at the interface of chemistry and biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6108 (2016).

Wei, C. et al. NBD-based colorimetric and fluorescent turn-on probes for hydrogen sulfide. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 479 (2014).

Huang, Z., Ding, S., Yu, D., Huang, F. & Feng, G. Aldehyde group assisted thiolysis of Dinitrophenyl ether:a new promising approach for efficient hydrogen sulfide probes. Chem. Commun. 50, 9185 (2014).

Ding, S. S., Feng, W. Y. & Feng, G. Q. Rapid and highly selective detection of H2S by nitrobenzofurazan (NBD) ether-based fluorescent probes with an aldehyde group, Sens. Actuators, B 238, 619 (2017).

Hou, P., Li, H. M. & Chen, S. A highly selective and sensitive 3-hydroxyflavone-based colorimetric and fluorescent probe for hydrogen sulfide with a large Stokes shift. Tetrahedron 72, 3531 (2016).

Wang, J. M., Shao, X. M., Wang, J. H. & Shao, S. J. An NBDbased fluorescent turn-on probe for the detection of homocysteine over cysteine and its imaging applications. Chem. Lett. 46, 442 (2017).

Gu, X.-H. et al. Tetrahydro[5]helicene fused Nitrobenzoxadiazole as a fluorescent probe for hydrogen sulfide, cysteine/homocysteine and glutathione. Spectrochim Acta Part. A. 229, 118003 (2020).

Zhu, H. C. et al. A novel highly sensitive fluorescent probe for bioimaging biothiols and its applications in distinguishing cancer cells from normal cells. Analyst 144, 7010 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Two-photon small molecular fluorogenic probe visualizing biothiols and sulfides in live cells, mice brain slices and zebrafish. Sens. Actuators B. 323, 128673 (2020).

Grzywa, R. et al. Synthesis and biological activity of diisothiocyanate-derived mercapturic acids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 667 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by the University of Gdańsk, Poland: project grant no. 538-L200-B505-17) (A.H.). This research was also funded in part by the MINIATURA 2021/05/X/NZ7/00289 from The National Science Centre (NCN, Poland) (I.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. H. – conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, formal analysis, writing original draft, project administration, funding acquisition, M. S-C. - investigation, M. S. - investigation, A. S. - investigation, (A) H-A. - supervision, proofreading; W. W. - conceptualization, supervision; I. (B) - conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing original draft, proofreading, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hać, A., Sildatk-Czoska, M., Szyszkowska, M. et al. New fluorescently labeled isothiocyanate derivatives as a potential cancer theranostic tool. Sci Rep 15, 41714 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25713-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25713-x