Abstract

To compare the clinical outcomes and learning curve characteristics of unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion (UBE-TLIF) and percutaneous uniportal full-endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (Endo-TLIF) in patients with single-segment lumbar degenerative diseases (LDD). A retrospective study was conducted from January 2022 to July 2023, involving a total of 95 patients with single-segment LDD, who were divided into two groups: the Endo-TLIF group and the UBE-TLIF group. The demographic characteristics, radiographic and clinical outcomes, as well as complications were meticulously recorded and analyzed in both groups. The mean operation time of Endo-TLIF group was 224.08 ± 58.90 min, which was significantly longer than that of UBE-TLIF group (169.93 ± 30.86 min) (P < 0.05). The perspective times were significantly shortened in the UBE-TLIF group compared with the Endo-TLIF group (P < 0.05). The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores showed significant improvement post-operation in both groups (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in VAS, ODI and modified Macnab criteria during the last follow-up periods (P > 0.05). Both groups exhibited similar complication rates and fusion rates (P > 0.05). CUSUM analysis indicated that the stabilization of operation time occurred after 23 cases for Endo-TLIF and 19 cases for UBE-TLIF, respectively. The safety and efficacy of both Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF for the treatment of LDD have been demonstrated. As the number of surgeries increased, the operation time for both procedures decreased. Specifically, after 23 surgeries, the operation time for Endo-TLIF reached a relative stability, while for UBE-TLIF it was achieved after 19 surgeries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the aging of the population, the incidence rate of lumbar degenerative disease (LDD) continues to rise1. LDD manifests as pain in the lower back and legs, restricted movement, and intermittent claudication, causing great suffering to patients2,3. Surgical treatment is usually considered when non-surgical treatment is ineffective4,5. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) and posterior lumber interbody fusion (PLIF) are the classic procedure for LDD treatment6. However, due to the extensive tissue dissection and prolonged traction required during the surgical process, TLIF/PLIF may cause postoperative lower back pain and weakness7. The advancement of spinal endoscopic equipment and techniques has significantly enhanced surgical efficiency, fostering the rapid growth of endoscopic lumbar fusion surgeries. Endoscopic lumbar fusion surgery is increasingly recognized by spinal surgeons due to its minimally invasive and effective. The classification of endoscopic lumbar fusion surgery can be based on surgical routes (interlaminar and transforaminal access routes) and the medium used (air-medium and water-medium). The water-medium techniques included percutaneous uniportal full-endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (Endo-TLIF) and unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion (UBE-TLIF). More and more spine surgeons are exploring minimally invasive surgical techniques to reduce the risk of open technology surgery. Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF represent two of the most prevalent minimally invasive endoscopic techniques for lumbar fusion currently in use8,9,10.

Recent researches suggested that endoscopic lumbar fusion has a relatively steep learning curve11,12,13,14,15. Endo-TLIF can achieve endoscopic discectomy, decompression of vertebral canal and foramen, and interbody fusion through a single hole working channel. While, the learning curve of Endo-TLIF is steep. UBE-TLIF employs two distinct channels for the endoscopic system and the working channel, with highly flexible instruments. Most tools of UBE-TLIF can be maneuvered using conventional open surgery equipment16,17, potentially leading to a learning curve different from that of Endo-TLIF. While, there is few relevant literatures report so far.

The clinical efficacy or learning curve of TLIF compared with Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF has been reported in the literature18,19,20,21. While, no studies have compared the learning curves between Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF directly. Therefore, in this study, we compared the early clinical efficacy of Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF surgeries and analyzed the learning curves of both procedures in patients with single-segment LDD. This is the first study to compare the learning curve of two surgical methods to provide some suggestions on reducing learning curve and surgical complications to surgeons.

Materials and methods

Patients selection

This study was a retrospective cohort study. All patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively enrolled from January 2022 to December 2023 at Tongren Hospital. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board, IRB) of Tongren Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Approval No.: 2022-058) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Review Measures for Biomedical Research Involving Humans. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee (IRB) of Tongren Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine due to the use of de-identified, previously collected clinical data.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Lumbar canal stenosis or lumbar disc herniation with lumbar instability; (2) Degenerative or isthmic spondylolisthesis (Meyerding Grade I or II) with or without neurological symptoms, confirmed by radiological features and clinical symptoms; (3) Symptoms of lower back and leg pain remain unrelieved after more than 6 weeks of conservative treatment; (4) Recieved UBE-TLIF or Endo-TLIF surgeries for single-segment LDD; (5) Sufficient follow-up data available for 6 months.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The responsible segment is not a single segment; (2) Previous history of lumbar spine surgery; (3) Meyerding Grade III or higher lumbar spondylolisthesis; (4) Congenital spinal deformity; (5) Non-degenerative lumbar conditions, such as trauma, infection or tumors; (6) Suboptimal baseline physical condition, making surgery intolerable.

Based on the above criteria, a total of 95 patients were included in this research. The patients were divided into two groups according to the surgical method: 40 cases in the Endo-TLIF group and 55 cases in the UBE-TLIF group. The patients were well informed about the operating procedures, complications, recurrence, and the medical expense. The final choice between the two different surgeries was decided by the patients and family members. The operations were carried out by the corresponding author of this article. The operator has rich experience in open surgery of spinal surgery, and has operated on at least 200 spinal endoscopes, but has not performed endoscopic fusion surgery before. All clinical data and functional scores of the patients were collected by two experienced attending spine surgeons.

Surgical techniques

Endo-TLIF: After general anesthesia, the patient was prone on the operating table. Fluoroscopy was used to locate the target intervertebral space, the posterior midline, and the pedicle surface projection. Initially, four percutaneous guide needles were inserted. The expanding catheter was used to separate the soft tissue, and then, the working channel of the spinal endoscopy was placed. After positioning the spinal endoscope, ablation exposed the lateral anatomy of the facet joint, identifying the tip of the facet joint and the pedicle. At the facet joint space, the annular saw was used to removed part of the facet joint, exposing the endpoints of the ligamentum flavum on both the cranial and caudal sides, and removing part of the lamina to the base of the spinous process. After bony decompression and clarifying the structure of the ligamentum flavum, the ligamentum flavum was removed to expose the dural sac and nerve roots. After revealing the lateral structure of the traversing root, an intervertebral disc guide rod was inserted to protect the inner side of the dural sac, placing an expandable elastic channel (ZLIF channel) into the disk space, The cartilaginous endplate was treated using an endplate scraper, exploring the endplate surface under the scope. Autologous bone and artificial bone were inserted into the intervertebral space, and a cage of appropriate size was inserted through the channel. After satisfactory positioning under fluoroscopy, the endoscope was removed. Four percutaneous pedicle screws were inserted, and rods were placed for fixation. Irrigation and suture were performed (Fig. 1).

Endo-TLIF: A 56-year-old male complains of chronic lower back pain for 3 years, with radiating pain and weakness in the right lower limb for 3 weeks. Preoperative magnetic resonance images showing severe L4/L5 disc herniation (A and B); Endoscopic view after the foraminoplasty showed decompressed L5 nerve and resected L4/5 disc (C and D); (E) Skin incisions. Postoperative day 2 lumbar spine AP and lateral view (F and G).

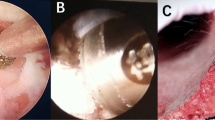

UBE-TLIF: After general anesthesia, the patient was prone on the operating table. Fluoroscopy was used to locate the target intervertebral space and pedicle screw. After the placement of a contralateral percutaneous pedicle screw guidewire, on the affected side, the landmarks of skin incision were 1.5 cm above and below the desired disk level and 1 cm lateral to the edge of the pedicle screw. Guide rods and dilators are inserted step by step, intersecting precisely at the desired disk level. The viewing portal and working portal are inserted, and ablation under endoscopic guidance is used to expose the intersection of the base of the spinous process with the lamina and the lateral facet joints, creating a space on the surface of the lamina. Drilling along the base of the spinous process opens the lower edge of the lamina, a rongeur is used to remove the lamina to expose the upper endpoint of the ligamentum flavum. The lateral lower inferior facet joint is removed, exposes the superior facet joint. After exploring the lateral recess, the tip of the superior facet joint is removed. Along the lateral recess, the lateral and caudal edges of the ligamentum flavum were exposed. After stripping and removing the ligamentum flavum along its cranial, lateral, and caudal edges, the ipsilateral dural sac and nerve roots were exposed. After exploring and protecting nerve roots on the affected side, the nucleus pulposus protrusion was examined. Part of the posterior longitudinal ligament and annulus fibrosus was excised, removing the nucleus pulposus. Expanders inserted gradually, the cartilaginous endplate scraped away, the endplate surface was explored under the scope. Autologous bone and artificial bone were placed in the intervertebral space, and a cage of appropriate size was inserted under vision. Four percutaneous pedicle screws were inserted, and rods were placed for fixation. Irrigation and suture were performed. (Fig. 2)

UBE-TLIF: A 63-year-old woman complained about lower back pain for 5 years, worsening over the past 3 months accompanied by radiating pain in both lower extremities. Intermittent claudication has worsened pain at rest. (A and B) Lateral and AP fluoroscopic view; (C and D). The lumbar CT in the sagittal plane indicates a bilateral spondylolysis at L5; (E and F). Intraoperative lateral and AP fluoroscopic view; (G and H). Endoscopic view; (I and J). Postoperative day 2 lumbar spine AP and lateral view; (K and L). 3 months postoperative lumbar spine AP and lateral view; (M) 5 months postoperative sagittal plane of lumbar CT.

Data collection

Patients’ demographic and psychosocial backgrounds was collected, including age, gender, general health status, Body Mass Index (BMI), and surgical segment. Perioperative indicators, such as operation time, muscle damage, hemorrhage, hospital stay duration, intraoperative fluoroscopy time, and complications were collected and evaluated.

Calculation of hidden blood loss (HBL)

HBL = Total Blood Loss (TBL) - Visible Blood Loss (VBL). VBL primarily includes intraoperative blood loss and postoperative drainage. Intraoperative blood loss, recorded by the anesthesiologist, includes blood in the suction bottles (total fluid volume in the suction bottles minus the irrigation fluid) and blood in the gauze used during the operation. Postoperative drainage volume is calculated by accumulating the amount of blood in the negative pressure suction device. The calculation of TBL is based on Gross’s formula22: TBL = BV × (Hctpre−op - Hctday 5 post−op) + Vt, where BV is the blood volume, Hctpre−op is the hematocrit before surgery, Hctday 5 post−op is the hematocrit on the 5th day after surgery, and Vt is the volume of red blood cells transfused, with hematocrit (Hct) expressed in decimals. Thus, the first step is to calculate the patient’s blood volume according to Nadler’s method23: BV = k1 × height (m)3 + k2 × weight (kg) + k3, where for male patients k1 = 0.3669, k2 = 0.03219, k3 = 0.6041; for female patients k1 = 0.3561, k2 = 0.03308, k3 = 0.18333. Finally, HBL is calculated.

Clinical efficacy assessment

Clinical information was evaluated by using visual analog scale (VAS) scores for back and leg pain, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), modified Macnab criteria. Bone graft fusion rate was evaluated according to the Bridwell fusion classification. The graft fusion was defined as Bridwell Grade A or B.

Plotting the learning curve

We applied the cumulative summation (CUSUM) method to operative time for each surgical approach (Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF). For case i, let \(\:{X}_{i}\) denote the operative time and \(\:u\) the mean operative time of all cases for that approach. The CUSUM up to case n was computed as CUSUM = \(\:{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}\left({X}_{i}-u\right)\).

The inflection point was defined a priori as the case at which the CUSUM curve reached a local maximum followed by a sustained non-increasing trend (plateau or decline) for ≥ 3 consecutive cases, indicating a transition from the learning phase to the competence phase. Two investigators independently inspected the CUSUM plots and resolved discrepancies by consensus. This two-phase framework focuses on identifying the number of cases required to achieve stable operative performance. We did not perform bootstrapping or cross-validation; instead, we relied on this pre-specified operational definition and independent dual review to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation, and differences were compared using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers with frequencies, and intergroup differences were compared using chi-square tests. Rank-sum tests were used to compare intergroup differences in ordinal data. Cumulative sum analysis was used to plot the LC by R soft (version 4.2.3). Significant differences were defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Patients characteristics

All the patients received single level Endo-TLIF(n = 40) or UBE-TLIF(n = 55), and all were followed up for at least 6 months. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the preoperative demographic, such as age, gender, BMI, surgical segment (Table 1).

Clinical outcomes

The average surgery time for UBE-TLIF group was 169.93 ± 30.86 min, significantly shorter than 224.08 ± 58.90 min for Endo-TLIF group (P < 0.001). The intraoperative fluoroscopy time for UBE-TLIF group was 47.44 ± 6.37 s, significantly less than 52.70 ± 10.24 s for Endo-TLIF group (P < 0.05). The total blood loss for UBE-TLIF group was 236.98 ± 32.42 ml, and the hidden blood loss was 92.27 ± 10.42 ml, significantly higher than 188.63 ± 14.77 ml and 77.21 ± 19.10 ml for the Endo-TLIF group respectively (P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in postoperative hospital stay duration between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 2).

Complications occurred in 3 patients (7.5%) in Endo-TLIF group and 5 patient (10%) in UBE-TLIF group. Based on the CUSUM-derived inflection points (23 cases for Endo-TLIF and 19 cases for UBE-TLIF), we further analyzed the distribution of complications between the learning and competence phases. In the Endo-TLIF group, 2 of the 3 complications (both dural tears) occurred during the learning phase, whereas in the UBE-TLIF group, 3 of the 5 complications occurred during the learning phase. The differences in complication rates between phases were not statistically significant for either surgical approach. In the Endo-TLIF group, the 2nd case experienced neural paralysis, the 6th and 15th cases experienced dural tears, with the cauda equina compressed in the 15th case, leading to long-term postoperative constipation. In the UBE-TLIF group, case 4th developed a spinal epidural hematoma (SEH), with leg pain and saddle area numbness on the 2nd day postoperatively, which was alleviated after surgery to remove the hematoma. Cases 8th and 25th experienced neural paralysis, and case 14th had a dural tear(Table 2).

The degree of muscle damage was evaluated by serological indicators, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and creatine kinase (CK) preoperative, and 1, 3, 5 days postoperative. Preoperative differences in CRP and CK between the two groups were not statistically significant(P > 0.05). Serological markers at different postoperative time points were significantly reduced compared to preoperative levels(P < 0.05). The CRP levels on the 3rd day postoperatively were significantly lower in the Endo-TLIF group compared to the UBE-TLIF group (P < 0.05). The CK levels were also lower in the Endo-TLIF group on the 1st and 3rd days postoperatively (P < 0.05; Table 3; Fig. 3).

In both groups, VAS scores at any postoperative time point were significantly reduced compared to preoperative (P < 0.05). Except for the back VAS score at 1 day postoperatively and the leg VAS score at 3 months postoperatively, there were no statistically significant differences at any time point between the two groups (P > 0.05). For both groups, ODI scores were significantly lower at 1 month, 3 months, and the final follow-up compared to preoperative scores (P < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in ODI scores at any postoperative time point between the two groups (P > 0.05). At the last follow-up, treatment efficacy was evaluated by the modified MacNab criteria. The lumbar fusion rate was 87.5% in Endo-TLIF group and 85.45% in UBE-TLIF group at the last follow-up, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Learning curve

We analyzed the CUSUM learning curves of the two surgical techniques, dividing them into two phases: the learning phase and the competence phase. The operative-time CUSUM plots exhibited an initial increase followed by a sustained non-increasing trend, consistent with a two-phase learning pattern. The transition from learning to competence occurred at case 23 for Endo-TLIF and case 19 for UBE-TLIF, after which the curves stabilized. Analyses focused on the learning-to-competence transition (Fig. 4).

Discussion

With the continuous development of spinal endoscopic technology, the indications for endoscopic lumbar intervertebral fusion have been expanded. Currently, for various types of lumbar disc herniation, lateral recess stenosis, foraminal stenosis, and central canal stenosis, endoscopic surgery can safely and effectively achieving clinical outcomes similar to open surgery. In 2017, Lee et al., after a 46-month follow-up of 18 patients who underwent Endo-TLIF surgery, found that all patients had significant improvements in postoperative VAS and ODI scores, with clear restoration of intervertebral height, and a fusion rate of 88.89% at the last follow-up24. In 2017, Heo et al. reported on single-segment UBE lumbar fusion surgery, with significant postoperative improvements in VAS and ODI scores compared to preoperative, but did not mention the fusion rate17, marking the first application of UBE technology in lumbar fusion surgery. Kim in 2021 compared UBE-TLIF to MIS-TLIF for treating single-segment LDD, revealing that early postoperative back pain significantly lessened in the UBE-TLIF compared to the MIS-TLIF, with reduced hospitalization times, and fusion and complication rates similar to those in the MIS-TLIF group(30). Both uniportal and unilateral biportal endoscopic fusion are superior to MIS-TLIF in terms of early postoperative low back pain relief, especially within 3 months post-surgery, however, there is no significant difference in early leg pain relief and functional improvement20,25,26. Yet, at present, there is a shortage of cross-comparison research between the two techniques. Studying and comparing the efficacy and learning curves of the two methods can help understand the advantages and disadvantages of each surgical technique, guiding further exploration in minimally invasive spinal treatment. This study’s show significant improvements in VAS scores, ODI index, and MacNab scores at all postoperative time intervals compared to preoperative scores. No significant differences were observed in postoperative hospital stay, complication rates, and fusion rates at the last follow-up. Both surgical techniques are effective in treating LDD.

Serum CRP and CK are objective indicators for assessing the surgical trauma of two different fusion techniques. The CRP levels on the 3rd day postoperatively were significantly lower in the Endo-TLIF group compared to the UBE-TLIF group (P < 0.05), and CK levels were also lower on the 1st and 3rd days postoperatively in the Endo-TLIF group compared to the UBE-TLIF group (P = 0.05, P < 0.05). Based on calculations, the HBL and TBL for Endo-TLIF were less than that for UBE-TLIF. The aforementioned results suggest that, compared to UBE-TLIF, Endo-TLIF causes less damage to posterior structures, possibly due to the uniportal endoscopic progressive dilation sleeve, single cannulation, and closed-channel system, which reduces repetitive damage to muscles and soft tissue, whereas the semi-closed instrument channel in UBE technology poses a risk of damage to muscles due to repeated instrument insertion and removal. Furthermore, the evaluation of muscle injury in this study was based solely on serum CRP and CK measurements. Postoperative imaging modalities such as MRI to assess muscle edema or electromyography (EMG) to evaluate functional impairment were not routinely performed, and such data were therefore unavailable. Incorporating these modalities in future prospective studies would provide a more comprehensive and objective assessment of muscle injury.

CUSUM was introduced by Professor Page in 1954, initially for assessing industrial quality control27. Currently, CUSUM has been widely applied in the study of surgical operation learning curves, allowing for more accurate and precise determination of specific learning curve situations, used for assessing the minimum number of operations required to master a surgical skill28,29,30. In 2020, Kim found that the slope of surgery time for UBE-TLIF operations started to level off after the 34th case, with an average surgery time of 171.7 ± 35.12 min11. By 2023, Zhao had analyzed the learning curves of Endo-TLIF, finding that the learning period was exceeded after the 25th case, averaging 199.14 ± 45.64 min31. In this study, the surgery and intraoperative fluoroscopy times for the UBE-TLIF group were significantly shorter than those for the Endo-TLIF group. The CUSUM learning curves fitted with surgery times indicate that the Endo-TLIF group reached a peak after accumulating 23 cases, while the UBE-TLIF group did so after 19 cases. With the peak as the boundary, the initial phase represents the learning period, showing the surgical team learning and familiarizing themselves with the procedure and gradually developing the best operational workflow, hence the upward slope of the learning curve. The latter phase indicates that the surgical team has mastered the characteristics of the procedure, forming mature operational habits and skills, thus the downward slope of the learning curve. The decompression process in UBE can utilize traditional lumbar surgery instruments and arthroscopes. The endoscope and instruments have greater mobility, overcoming the limitations of single-channel operations. Thus, UBE has a shorter average surgery time. Its learning curve is somewhat smoother, enabling learners to master it quickly, especially for doctors experienced with arthroscopy or open surgery. Uniportal endoscopy often requires the operator to perform based on proficient knowledge of the anatomy related to the intervertebral foramen approach, with a preliminary foundation in lumbar transforaminal and translaminal endoscopic decompression surgery. Once the working channel is placed, adjustments cannot be made flexibly, especially in the early stages when the surgery time tends to be longer. When inserting the cage in Endo-TLIF, it often requires the removal of the endoscope and performing operations with the aid of a C-arm fluoroscope, posing risks of damaging nerve roots or the dura mater.

Complications reported in previous literature include epidural hematoma17,32, dural tear17, infection32, transient nerve palsy25, quadriceps weakness (Grade 4)33, temporary knee tendon hyper-reflexia33, injury of anterior longitudinal ligament33, cage subsidence32,34, cage migration34, and endplate fracture35. During the early exploratory phase of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion, the complication rate was high9,36. In 2013, Jacquot and others reported a 36% complication rate in 57 cases of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion, mainly including exiting nerve root damage, cage migration, etc., with 13 cases (22.8%) undergoing revision surgery36. In recent years, with the improvement of endoscopic instruments and the advancement of surgical techniques, the complication rate of lumbar endoscopic fusion surgery has significantly decreased. Recent meta-analyses show that the complication rate of lumbar endoscopic fusion surgery ranges between 1.1% and 9.8%37, similar to that of MIS-TLIF26,37. Most complications are minor and can be improved with conservative treatment19. This study shows that the overall rate of postoperative complications in both groups remained at a low level, indicating that the safety of both surgical methods is commendable. Dural tears and nerve paralysis are the most common complications of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar intervertebral fusion, with reported complication rates of 2.90% to 14.29% in unilateral biportal endoscopic fusion procedures17,38,39. The incidence of neurological and dural complications in percutaneous endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion surgery is slightly higher than that in MIS-TLIF. However, these complications mostly occur in the early stages of the technique’s application, with the rate of complications decreasing as proficiency is gained. Neurological monitoring under local or general anesthesia may be an effective measure to reduce nerve damage. In the UBE-TLIF group, there was one case of postoperative spinal epidural hematoma (SEH). Symptoms were alleviated after the hematoma was surgically removed, with intraoperative observations showing the hematoma adhesion compressing the dura mater within the spinal canal and adjacent to the spinous processes. Spinal epidural hematoma is one of the most significant causes of spinal canal recompression postoperatively. Kim et al. reported on 310 patients treated with UBE technology, with routine MRI re-examination showing a total incidence of SE at 23.6%, yet only 6 patients underwent hematoma evacuation surgery40. Risk factors for increased incidence of SEH were identified as female gender, age > 70 years, preoperative use of anticoagulants, and surgeries requiring more bony operations (laminectomy or intervertebral fusion). Surgeons summarized the following precautions based on experience: perioperative coagulation indicators, preoperative optimization of platelet function, and standardized blood pressure control. Intraoperatively, water pressure was controlled using a pump (or by suspending a 3000 mL saline bag at an appropriate height when no pump was available), with radiofrequency electrocoagulation used for epidural and surrounding soft tissue bleeding. The use of bone wax for bleeding, effective postoperative blood pressure control, and close monitoring of drainage are all effective measures to reduce the incidence of SEH.

The surgeon in this study had extensive experience with open lumbar fusion procedures and had already performed 200 endoscopic surgeries prior to this study. Therefore, we believe that, after excluding patient-related factors, the surgeon’s proficiency in the surgical technique may be the primary factor contributing to differences in clinical outcomes. Compared to UBE-TLIF, Endo-TLIF, though less invasive, offers a narrower field of view and demands higher technical precision. Due to current limitations in endoscopic tools, Endo-TLIF often requires repeated endoscope removal to insert the cage under fluoroscopy, which may increase the risk of neural irritation, particularly to the exiting nerve root. As a result, Endo-TLIF typically requires a longer learning curve to achieve proficiency.

Additionally, proper surgical approach selection based on pathology also affects outcomes. UBE-TLIF provides better decompression for severe ligamentum flavum or laminar hypertrophy due to its broader view and flexibility, while Endo-TLIF is preferable for foraminal or lateral recess stenosis, offering targeted decompression with minimal tissue disruption.

Although this study compares the learning curves and clinical outcomes of UBE-TLIF and Endo-TLIF and provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this is a single-center, retrospective study in which all surgeries were performed by the same surgeon. Some surgical details, such as working channel establishment time and incision length, could not be retrospectively retrieved, which may introduce bias. Additionally, specific intraoperative parameters such as incision length and channel establishment time were not recorded in this retrospective study, which limits our ability to fully elucidate the underlying causes of the operative time differences observed between the two techniques. Future prospective investigations should include these variables to more accurately assess their contribution to surgical efficiency. Second, the relatively small sample size may affect the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Third, the follow-up period was limited to 6 months. While this duration is sufficient to evaluate early clinical recovery and complications such as neural injury and cerebrospinal fluid leakage, it is inadequate for fully assessing fusion outcomes. At this stage, only trends in bone bridging can be observed, which may not accurately reflect final fusion status. Longer-term follow-up is necessary for confirmation. Fourth, EMG was not used due to its invasive nature, and early postoperative MRI was often affected by artifacts caused by irrigation pressure, bleeding, or hemostatic materials. Therefore, CRP and CK levels were used as surrogate markers to assess muscle injury, though this method has inherent limitations. We did not perform bootstrapping or cross-validation; instead, we used a pre-specified operational definition of the inflection point and independent dual review to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

Conclusions

The safety and efficacy of both Endo-TLIF and UBE-TLIF for the treatment of LDD have been demonstrated. As the number of surgeries increased, the operation time for both procedures decreased. Specifically, after 23 surgeries, the operation time for Endo-TLIF reached a relative stability, while for UBE-TLIF it was achieved after 19 surgeries.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Raw clinical data are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality and data protection regulations; de-identified data can be provided to qualified researchers under a standard data-use agreement.

References

Ravindra, V. M. et al. Degenerative lumbar spine disease: Estimating global incidence and worldwide volume. Glob Spine J. 8, 784–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218770769 (2018).

Phillips, F. M., Slosar, P. J., Youssef, J. A., Andersson, G. & Papatheofanis, F. Lumbar spine fusion for chronic low back pain due to degenerative disc disease: a systematic review. Spine 38, E409–422. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182877f11 (2013).

Andersson, G. B. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet Lond. Engl. 354, 581–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4 (1999).

Gu, S., Li, H., Wang, D., Dai, X. & Liu, C. Application and thinking of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in degenerative lumbar diseases. Ann. Transl Med. 10, 272. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-22-401 (2022).

Buser, Z. et al. Spine degenerative conditions and their treatments: National trends in the united States of America. Glob Spine J. 8, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217696688 (2018).

Meng, B., Bunch, J., Burton, D. & Wang, J. Lumbar interbody fusion: recent advances in surgical techniques and bone healing strategies. Eur. Spine J. Off Publ Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 30, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06596-0 (2021).

Seng, C. et al. Five-year outcomes of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a matched-pair comparison study. Spine 38, 2049–2055. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a8212d (2013).

Kim, J-S. et al. Unilateral Bi-portal endoscopic decompression via the contralateral approach in asymmetric spinal stenosis: A technical note. Asian Spine J. 15, 688–700. https://doi.org/10.31616/asj.2020.0119 (2021).

Osman, S. G. Endoscopic transforaminal decompression, interbody fusion, and percutaneous pedicle screw implantation of the lumbar spine: A case series report. Int. J. Spine Surg. 6, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsp.2012.04.001 (2012).

Wang, J-C., Cao, Z., Li, Z-Z., Zhao, H-L. & Hou, S-X. Full-Endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion versus minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with a tubular Retractor system: A retrospective controlled study. World Neurosurg. 165, e457–e468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.06.083 (2022).

Kim, J-E. et al. Learning curve and clinical outcome of biportal Endoscopic-Assisted lumbar interbody fusion. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 8815432. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8815432 (2020).

Sharif, S. & Afsar, A. Learning curve and minimally invasive spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 119, 472–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.094 (2018).

Ahn, Y., Lee, S., Kim, W-K. & Lee, S-G. Learning curve for minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review. Eur. Spine J. Off Publ Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 31, 3551–3559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07397-3 (2022).

Pennington, Z. et al. Learning curves in robot-assisted spine surgery: a systematic review and proposal of application to residency curricula. Neurosurg. Focus. 52, E3. https://doi.org/10.3171/2021.10.FOCUS21496 (2022).

Nandyala, S. V., Fineberg, S. J., Pelton, M. & Singh, K. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: one surgeon’s learning curve. Spine J. Off J. North. Am. Spine Soc. 14, 1460–1465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.045 (2014).

Heo, D. H., Hong, Y. H., Lee, D. C., Chung, H. J. & Park, C. K. Technique of biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurospine 17, S129–S137. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040178.089 (2020).

Heo, D. H., Son, S. K., Eum, J. H. & Park, C. K. Fully endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion using a percutaneous unilateral biportal endoscopic technique: technical note and preliminary clinical results. Neurosurg. Focus. 43, E8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.5.FOCUS17146 (2017).

Hao, J., Cheng, J., Xue, H. & Zhang, F. Clinical comparison of unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy with percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for single l4/5-level lumbar disk herniation. Pain Pract. Off J. World Inst. Pain. 22, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.13078 (2022).

Heo, D. H., Lee, D. C., Kim, H. S., Park, C. K. & Chung, H. Clinical results and complications of endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative disease: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 145, 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.033 (2021).

Ao, S. et al. Comparison of preliminary clinical outcomes between percutaneous endoscopic and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases in a tertiary hospital: is percutaneous endoscopic procedure superior to MIS-TLIF? A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 76, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.043 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Comparing the efficacy and complications of unilateral biportal endoscopic fusion versus minimally invasive fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases: a systematic review and mate-analysis. Eur. Spine J. Off Publ Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 32, 1345–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07588-6 (2023).

Gross, J. B. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for Dilution. Anesthesiology 58, 277–280. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-198303000-00016 (1983).

Nadler, S. B., Hidalgo, J. H. & Bloch, T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 51, 224–232 (1962).

Lee, S-H., Erken, H. Y. & Bae, J. Percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiological results of mean 46-Month Follow-Up. BioMed. Res. Int. 2017, 3731983. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3731983 (2017).

Kim, J-E., Yoo, H-S., Choi, D-J., Park, E. J. & Jee, S-M. Comparison of minimal invasive versus biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for Single-level lumbar disease. Clin. Spine Surg. 34, E64–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000001024 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes and complications between percutaneous endoscopic and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar disease: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 24, 441–452 (2021).

Page, E. S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 41, 100–115 (1954).

Shahi, P. et al. Surgeon experience influences robotics learning curve for minimally invasive lumbar fusion: A cumulative sum analysis. Spine 48, 1517–1525. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000004745 (2023).

Bolsin, S. & Colson, M. The use of the cusum technique in the assessment of trainee competence in new procedures. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 12, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/12.5.433 (2000).

Wohl, H. The cusum plot: its utility in the analysis of clinical data. N Engl. J. Med. 296, 1044–1045. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197705052961806 (1977).

Zhao, T., Dai, Z., Zhang, J., Huang, Y. & Shao, H. Determining the learning curve for percutaneous endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases. J. Orthop. Surg. 18, 193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03682-z (2023).

Park, M-K., Park, S-A., Son, S-K., Park, W-W. & Choi, S-H. Clinical and radiological outcomes of unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion (ULIF) compared with conventional posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF): 1-year follow-up. Neurosurg. Rev. 42, 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-019-01114-3 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: preliminary report of seven cases with 12-Month Follow-Up. BioMed. Res. Int. 2019, 3091459. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3091459 (2019).

Jin, M., Zhang, J., Shao, H., Liu, J. & Huang, Y. Percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar diseases: A consecutive case series with mean 2-Year Follow-Up. Pain Physician. 23, 165–174 (2020).

Kolcun, J. P. G., Brusko, G. D. & Wang, M. Y. Endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion without general anesthesia: technical innovations and outcomes. Ann. Transl Med. 7, S167. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.07.92 (2019).

Jacquot, F. & Gastambide, D. Percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: is it worth it? Int. Orthop. 37, 1507–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-013-1905-6 (2013).

Luan, H., Peng, C., Liu, K. & Song, X. Comparing the efficacy of unilateral biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in lumbar degenerative diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. 18, 888. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04393-1 (2023).

Kang, M-S. et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion using the biportal endoscopic techniques versus microscopic tubular technique. Spine J. 21, 2066–2077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.06.013 (2021).

Kim, J-E. & Choi, D-J. Biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with arthroscopy. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 10, 248–252. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2018.10.2.248 (2018).

Kim, J-E., Choi, D-J., Kim, M-C. & Park, E. J. Risk factors of postoperative spinal epidural hematoma after biportal endoscopic spinal surgery. World Neurosurg. 129, e324–e329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.141 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and staff who made this study possible.

Funding

The study was supported by Shanghai Changning District Healthcare Committee (grant numbers RCJD2022S01), the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission Project (grant number 22Y11912000), Orthopedic Priority Speciality of Changning District (grant number 20231002) and the Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery Research Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (grant number 2021JCPT03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G. and X.Y. conceived and designed the study. Y.X. and Q.Y. recruited patients and collected data. Y.X. and Q.Y. drafted the main manuscript; these authors contributed equally and share first authorship. Y.X., Q.Y., W.W., Z.H., and Y.C. performed data curation, formal analyses, and investigation. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board, IRB) of Tongren Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Approval No.: 2022-058).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Y., Yu, Q., Wang, W. et al. Comparison of learning curves and clinical efficacy of two endoscopic techniques for single segment lumbar degenerative disease. Sci Rep 15, 41803 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25729-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25729-3