Abstract

Seedling dynamics are crucial for forest regeneration and species coexistence. Understanding the factors influencing seedling survival rate provides insights into improving natural regeneration. This study evaluated the effects of biotic and habitat factors on Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii seedling survival rate over 2 years on Guandi Mountain, North China, using a generalized linear mixed-effects model. Our results did not provide strong evidence of negative density dependence at the community level during the seedling stage. For seedlings < 2 cm in diameter and < 8 years old, survival rate was primarily influenced by conspecific seedling density. As seedlings grew, the impact of biotic factors declined, whereas soil and light conditions became more important. Elevation strongly affected seedlings < 0.3 m in height. With increasing height, biotic factors became more influential, and conspecific seedling density positively impacted survival rate. Seedling regeneration was found to be increasing on Guandi Mountain, with no evidence of seed limitation. Biotic and habitat factors influenced survival rate, but conspecific seedling density negatively affected survival rate at all levels except for seedlings < 0.3 m in height. Overall, negative density dependence was negligible in the early-seedling stage. In conclusion, although habitat heterogeneity and density effects shape seedling survival rate, density effect plays a more critical role in L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii forest regeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural forest regeneration is the process of restoring forest resources and ecosystems through self-renewal. Seed germination, seedling regeneration, sapling growth, and tree mortality are fundamental processes that drive long-term forest dynamics. A quantitative understanding of how biotic and abiotic factors influence these processes is essential for evaluating and predicting stand dynamics. However, these processes occur slowly under harsh environmental conditions, such as low temperature, drought, poor soil fertility and high elevation1. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms driving tree species assembly and their relative contributions remains a major challenge for ecologists2. Various theories explain species coexistence3,4,5, with models of diverse communities typically emphasizing density-dependent survival, niche partitioning, and ecological equivalence6,7,8,9.

For tree communities, the transition from seedling to sapling is a critical bottleneck in tree establishment. Compared with mature plants, seedlings are more vulnerable to biotic and abiotic constraints, although the influence of these factors changes over time10. Larger individuals tend to be more resilient to environmental stressors. Seedling regeneration is influenced by external conditions, interspecific competition, and species traits. Each stage, from seed production to germination, survival, establishment, and eventual maturity, is shaped by natural and human factors, with different effects at various stages. In general, seedling survival increases with size11,12. Given the substantial spatiotemporal variation in seedling survival, studying the factors influencing different regeneration stages is essential for understanding the entire process.

The Janzen–Connell hypothesis has been widely studied, highlighting negative density dependence (NDD) as a key mechanism promoting species coexistence and diversity, consistent with observations in larch forests13,14,15,16. Seed predators reduce seedling survival and recruitment, mitigating the effects of NDD. Habitat niche partitioning also interacts with NDD, influencing seedling survival2. Numerous studies have shown that seedling survival is shaped by local abiotic conditions due to interspecific competition for limited resources17,18,19. Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii, a dominant species in natural secondary forests, has been extensively studied in the mountains of North China20,21,22. Although seedling growth and survival play a crucial role in forest regeneration, most research focuses on environmental factors, such as solar radiation, water availability, soil nutrients, slope, and aspect21,23,24,25. However, few studies have systematically analyzed the combined effects of biotic and abiotic factors on seedling survival26,27.

This study examines the relative importance of biotic and abiotic drivers of seedling survival in a temperate tree community. We analyzed species composition and temporal seedling dynamics in 18 plots of L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii artificial forest on Guandi Mountain during 2022–2023, Specifically, we addressed the following questions: (1) What are the main factors affecting seedling survival in the L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii artificial forest on Guandi Mountain? (2) Does negative density dependence vary across different developmental stages? (3) Do biotic and habitat factors influence seedling survival consistently across community, diameter, height, and age levels?

Materials and methods

Study site

The study was conducted in the Chailugou region of Guandi Mountain (37°51´N, 111°32´E) in Jiaocheng County. The area has a temperate continental monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of 4℃ and temperature extremes of − 11℃ and 31℃. The region’s mean annual precipitation and evaporation are 822 and 1,268 mm, respectively25. The climate data is sourced from China Meteorological Data Service Centre by Jiaocheng station (https://data.cma.cn). The time span is from July 2022 to August 2023. The primary soil types are mountain cinnamon soil, cinnamon soil, and brown soil28.

Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii is the dominant tree species in the study area and is widely planted at elevations of 1500–2840 m. The main shrub species include Rosa multiflora, Acer tataricum subsp. ginnala, Spiraea salicifolia, Crataegus pinnatifida, and Daphne giraldi25. Dominant grasses include Taraxacum mongolicum, Fragaria orientalis, Bupleurum smithii, Geranium wilfordii, Chrysanthemum chanetii, Thalictrum aquilegiifolium, Ranunculus japonicus, Lathyrus humilis, and Vicia unijuga29.

In 2022, a 1-km2 (500 × 200 m) artificial L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii forest was established on Guandi Mountain to assess natural regeneration. The forest had remained unmanaged for 30 years, with no thinning or silvicultural interventions.

Seedling census

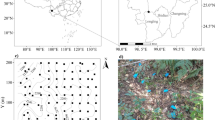

In July and August 2022, 18 randomly selected plots (20 × 20 m) were established, each containing regenerated seedlings and mature trees (Fig. 1). The plant samples were collected on public land, and we had obtained permissions from an appropriate governing body. The elevation, slope and aspect were measured in each plot (Table 1). All plots were resurveyed in July and August 2023. Seedlings and saplings were defined as individuals with a diameter at breast height ≤ 5 cm and 5–6 cm, respectively (hereafter referred to as seedlings)10,25,29. They were classified by diameter (< 1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, and > 5 cm), height (< 0.3, 0.3–0.6, 0.6–1.0, 1.0–1.5, 1.5–2.0, and > 2.0 m), and age (0–2, 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10–12, and > 12 years)10,25. Among them, the age of each seedling was estimated by counting annual bud scale scars.

The location of sample plot in Guandi Mountain. Generated in the R 4.1.2.3 software (http://www.r-project.org).

Biotic environmental variables

Biotic environmental variables included herbaceous effects, litter thickness, and biotic neighborhood effects. As only L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii was present in the study area, neighborhood effects were analyzed based on conspecific interactions. Seedling density of the same species and conspecific adult basal area (tree diameter measured at 1.30 m above the ground) were used as indicators of biotic neighborhood effects. Within each plot, five subplots (1 × 1 m) were arranged in an X-shape to record herbaceous density and coverage. Litter was collected using the diagonal method, with three sampling points (30 × 30 cm) per plot, and litter thickness was recorded30.

Habitat variables

Seedling habitat variables were defined based on soil properties, canopy density, and topography. Soil samples were collected using an X-shaped sampling scheme within each plot, with five sampling points per plot at depths of 0–20 cm. Samples were placed in sealed bags, and five soil properties were measured: soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), available nitrogen (AN), and available phosphorus (AP). SOM was measured using the H2SO4-K2CrO7 method, TN using the Kjeldahl method, TP via colorimetry, AN using the HClO4–H2SO4 method, and AP via Olsen’s method25,31.

To reduce multicollinearity and simplify soil factor variables, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) on the five soil properties32. The first two principal components, which explained 85.34% of the total variance in soil nutrient indicators, were selected for analysis (Table 2). PCA axis 1 (PC1), explaining 63.37% of the variance, was associated with high SOM, TN, and AN. PCA axis 2 (PC2), explaining 21.97% of the variance, was associated with low TP and AP.

Two topographic factors, slope and elevation, were measured using a compass and a handheld global positioning system, respectively. Canopy density was estimated visually, and all values were recorded for each plot29,30.

Statistical analysis

Seedling survival rate during 2022–2023 was modeled as a function of biotic and habitat variables (Table 3) using generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs), which were essentially logistic regressions in the present study33. Seedling survival rate at different diameter, height, and age levels was used as the response variable. Continuous explanatory variables were standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation32. Among them, seedling survival rate referred to the number of surviving seedlings accounted for the total number of seedlings in each seedling plot.

To examine the relative importance of biotic and habitat factors, we constructed four models: (1) the null model, including only plot as a random effect; (2) the biotic model, adding biotic factors (conspecific adult basal area, seedling density, herbaceous coverage, herbaceous density, and litter thickness) as fixed effects to the null model; (3) the habitat model, adding habitat factors (soil PC1, soil PC2, slope, elevation, and canopy density) as fixed effects to the null model; and (4) the full model, combining biotic and habitat factors as fixed effects. Model selection was based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), with lower AIC values indicating better model fit. Models with an AIC difference < 2 were considered equally effective34. Then R2 coefficient was ultimately used to evaluate model. Seedling survival rate was analyzed at four levels: (1) the community level (all L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii seedlings), (2) diameter levels, (3) height levels, and (4) age levels (with levels 2–4 listed in the Seedling census section). As seedlings in the same plot experience similar environmental conditions, plot ID was included as a random effect in the GLMMs.

To quantify the partial effect of each variable, we calculated odds ratios (the exponentiated model coefficients). Odds ratios > 0 and < 0 indicated positive and negative effects on survival, respectively.

All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS 22.0 (Chicago, USA), and figures were created using Origin 2024 (Northampton, MA, USA). GLMM analyses were performed in R (v.4.3.2), using the “lme4” package35.

Results

Community level seedling survival

Compared with the original 1952 L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii seedlings recorded in 2022, the number increased to 3539 in 2023, representing a 44.8% increase. Model comparisons showed clear differences in explanatory power among the four models [null, biotic, habitat, and full (biotic + habitat)] for seedling survival density (Table 4). The full model provided the best fit. However, in the 0–2-year age class, the null model had the lowest AIC value, indicating no significant effects from biotic or habitat variables. Consequently, further analysis was not conducted on this age group.

At the community level, the full model showed the best overall fit (Table 4). Seedling density of conspecifics had a strong positive correlation with seedling survival rate (odds ratio = 2.38, P < 0.01, Fig. 1), indicating that seedling survival rate significantly increased with higher seedling density. Additionally, herbaceous coverage and slope had a positive effect on seedling survival rate, whereas other variables exhibited a negative impact (Fig. 2).

Odds ratios of seedling survival rate for the most comprehensive and likely models presented in Table 3. Circles represent odds ratios for each parameter, with 95% confidence limits (CL) indicated by horizontal lines. Filled circles denote odds ratios that are significantly different from 0. Refer to Table 3 for variable abbreviations.

Diameter class seedling survival

Analysis of seedling survival rate by diameter level from 2022 to 2023 revealed that, for most diameter classes (< 1, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, and > 5 cm), the full model had the lowest AIC value and provided the best fit (Table 4). However, for seedlings in the 1–2-cm diameter class, the biotic model had the lowest AIC value and the best fit. As the difference in AIC between the biotic and full models was < 2, both models were considered equally effective. However, the full model was ultimately chosen for analysis based on R2 (Table 4).

For seedlings with diameters < 1 (odds ratio = 4.226, P = 0.001, Fig. 3A) and 1–2 cm (odds ratio = 2.754, P = 0.019, Fig. 3B), seedling density of conspecifics was significantly positively correlated with seedling survival rate. In the 2–3 -cm diameter class, soil PC1 had a significant positive effect on seedling survival rate (odds ratio = 2.980, P = 0.046, Fig. 3C). For seedlings in the 3–4 cm diameter class, three variables significantly influenced seedling survival: conspecific adult basal area had a negative effect (odds ratio = − 2.258, P = 0.01), whereas seedling density of conspecifics (odds ratio = 1.275, P = 0.026) and soil PC1 (odds ratio = 1.954, P = 0.02) had positive effects (Fig. 3D). In the 4–5 -cm diameter class, conspecific adult basal area showed a highly significant negative relationship with seedling survival (odds ratio = − 1.556, P = 0.007, Fig. 3E). However, soil PC1 (odds ratio = 1.100, P = 0.007) and seedling density of conspecifics (odds ratio = 1.265, P = 0.019) had positive effects on survival (Fig. 3E). For seedlings with diameters > 5 cm, a significant negative correlation was observed between seedling survival rate and conspecific adult basal area (odds ratio = − 2.657, P = 0.011), herbaceous coverage (odds ratio = − 2.639, P = 0.027), as well as canopy density (odds ratio = − 2.978, P = 0.021) (Fig. 3F).

Odds ratios of seedling survival rate at the diameter level for optimal models. Circles represent odds ratios for each parameter, with 95% confidence limits (CL) indicated by horizontal lines. Filled circles denote odds ratios that are significantly different from 0. Refer to Table 3 for variable abbreviations.

Height class seedling survival

Seedling height classes were analyzed over two consecutive years, and the full model provided the best fit with the lowest AIC values for the height classes of 0.3–0.6, 0.6–1.0, and > 2 m. Ultimately, the full model was also chosen to analyze the height classes < 0.3, 1.0–1.5, and 1.5–2.0 m.

For seedlings < 0.3 m in height, elevation showed a highly significant positive correlation with seedling survival rate (odds ratio = 0.817, P = 0.008, Fig. 4A). In seedlings 0.3–0.6 m in height, survival rate was significantly positively correlated with seedling density (odds ratio = 2.645, P = 0.001) and canopy density (odds ratio = 2.146, P = 0.002) (Fig. 4B). For seedlings 0.6–1.0 m in height, seedling density of conspecifics (odds ratio = 2.645, P = 0.001) and canopy density (odds ratio = 2.147, P = 0.002) showed significant positive correlations with survival rate (Fig. 4C). For seedlings of 1.0–1.5 m in height, seedling density of conspecifics had a significant positive effect on survival rate (odds ratio = 2.279, P = 0.012, Fig. 4D). In the height class 1.5–2.0 m, no significant correlations were found between biotic or abiotic factors and seedling survival rate (Fig. 4E). For seedlings > 2 m in height, conspecific adult basal area (odds ratio = − 1.300, P = 0.02) and canopy density (odds ratio = − 2.035, P = 0.016) had significant negative effects on survival rate, whereas seedling density of conspecifics (odds ratio = 2.517, P = 0.02) and soil PC1 (odds ratio = 2.848, P = 0.01) had significant positive effects (Fig. 4F).

Odds ratios of seedling survival rate at the height level for optimal models. Circles represent odds ratios for each parameter, with 95% confidence limits indicated by horizontal lines. Filled circles denote odds ratios that are significantly different from 0. Refer to Table 3 for variable abbreviations.

Age class seedling survival

The relative importance of biotic and habitat factors varied significantly across age classes of seedlings (Table 4). For seedlings in the 2–4-, 10–12-, and > 12-years age groups, the best fit was provided by the full model. For seedlings in the 4–6- and 6–8-years age classes, the biotic model was the most appropriate. For the 8–10-years age class, the full and biotic models had similar AIC values, indicating equal effectiveness. Therefore, we present the coefficient estimates from the full model for 2–4, 8–10, 10–12, and > 12 years and from the biotic model for 4–6 and 6–8 years (Fig. 5).

Odds ratios of seedling survival rate at the age level for optimal models. Circles represent odds ratios for each parameter, with 95% confidence limits (CL) indicated by horizontal lines. Filled circles denote odds ratios that are significantly different from 0. Refer to Table 3 for variable abbreviations.

For seedlings in the 2–4-years (odds ratio = 2.748, P = 0.022, Fig. 5A), 4–6-years (odds ratio = 2.267, P = 0.005, Fig. 4B), and 6–8-years (odds ratio = 2.587, P = 0.004, Fig. 5C) age classes, seedling density of conspecifics was the only significant factor positively correlated with seedling survival rate. For seedlings in the 8–10 years age class, soil PC1 (odds ratio = 2.156, P = 0.048) and seedling density of conspecifics (odds ratio = 2.721, P = 0.021) showed significant positive effects on seedling survival rate (Fig. 5D). However, conspecific adult basal area exerted a significant negative effect on seedling survival rate (odds ratio = − 2.484, P = 0.032, Fig. 5D). For seedlings in the 10–12 years age class, soil PC1 had a significant positive effect on survival (odds ratio = 2.883, P = 0.052), whereas conspecific adult basal area showed a significant negative effect (odds ratio = − 2.235, P = 0.007) (Fig. 5E). For seedlings in the > 12-years age class, survival was more likely in areas with higher seedling density of conspecifics, higher levels of SOM, TN, TP, AN, and AP, and lower levels of canopy density, herbaceous coverage, and conspecific adult basal area (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

Analysis of factors affecting seedling survival at the community level

Our study revealed that biotic and habitat factors influenced seedling survival rate at the community level, with biotic factors having a more significant impact. The increase in seedling density was strongly associated with a higher survival rate of target seedlings, a result that contrasts with some previous studies32,36,37. These results suggest that negative density dependence may be weak or undetectable at the seedling stage in this artificial forest context on Guandi Mountain, and the discrepancy among studies may be attributed to differences in study sites and community types. Additionally, we found that seedling density of conspecific coniferous species positively impacts seedling survival rate, which may be due to the concentrated distribution of seedlings in the study area, forming a robust functional seedling community. Such communities tend to have enhanced resilience to external threats and greater self-regulation abilities compared with individual seedlings. They also benefit from increased competition with other species for environmental resources, gradually leading to an increase in the number of surviving seedlings38,39.

This study found no significant impact of biotic factors on seedling survival rate, although a negative correlation was observed between conspecific adult basal area and seedling survival rate. Although the local environment was likely suitable for both mature tree growth and seedling survival rate40, adult trees typically outcompete seedlings, hindering their survival. Moreover, the large crown widths of mature trees block sunlight, reducing the light available for seedlings and potentially leading to their death41.

We observed a negative correlation between herbaceous density and seedling survival rate, whereas a positive correlation existed between herbaceous coverage and seedling survival rate. This suggests that higher herbaceous density and diversity, which increase the demand for resources such as light, water, and soil, create competitive pressures that negatively affect seedling survival rate42. However, increased herbaceous coverage can have a positive effect by protecting seedlings from excessive rainfall that might otherwise damage their roots, thereby enhancing survival43. The contrasting effects of herbaceous density and coverage were obvious in this study. One explanation is that there exists species-specific competition between herbaceous plant and seedlings44,45,46. High herbaceous density increases competition for limited resources among individuals, which overcrowding leads to smaller size, reduce growth and higher mortality. Another explanation is that extensive herbaceous coverage creates microhabitat buffering47. Coverage can enhance habitat complexity to provide shelter for seedlings and maximize microhabitat benefits while minimizing competition48. Additionally, we found that thicker litter layers negatively impact seedling survival rate at the community level. Excessive litter may impede seed germination and seedling growth, making seedlings more vulnerable to breakage49.

Biotic and habitat factors combined to influence seedling survival rate, as shown in previous studies32,50. This study also confirmed that the habitat environment likely plays a major role in seedling survival rate at the community level. Seedlings appear to be particularly sensitive to changes in their habitat, and the influence of abiotic factors became more pronounced over time9,51.

At the community level, soil factors showed a negative correlation with seedling survival rate. During seedling growth, the initial nutrients stored in the seeds are depleted, and the remaining nutrients needed for development primarily come from the soil52; thus, soil nutrients play a key role in late-stage seedling survival rate. However, our study found that neither rich SOM and TN in soil PC1 nor rich TP in soil PC2 promoted seedling survival rate at the community level. High nutrient levels in the soil may not be conducive to seedling survival, possibly because the fragile root systems of seedlings are ill-suited for utilizing high levels of nutrients, which can hinder their healthy growth53.

We also found that canopy density, reflecting light availability, was negatively correlated with seedling survival rate, although this effect was not statistically significant. This may be attributed to L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii has relatively low light demands during its early growth stages. However, excessive light exposure can lead to rapid water evaporation, causing seedlings to wilt and die54,55.

Seedling survival rate was positively correlated with slope and negatively correlated with elevation. The 18 plots surveyed had a slope variation of 26° and an elevation difference of 108 m. Such topographic variations can influence soil moisture and nutrient availability, which in turn affect seedling survival rate56. Specifically, we observed a decrease in seedling survival rate with increasing elevation, likely because higher altitudes have lower temperatures that are less suitable for seed germination, substantially hindering growth. Moreover, high-elevation areas are often dominated by shrub and grass species that occupy resources, further inhibiting seedling growth57. The positive correlation between slope and seedling survival rate contrasted with previous studies, which reported that steeper slopes are associated with reduced seedling survival rate58,59. However, in our study, steeper slopes likely accumulated more aboveground biomass, which may have created a more favorable microenvironment for seedling survival rate60.

Analysis of factors affecting seedling survival at different diameter class levels

The survival of small-diameter seedlings was primarily influenced by biotic factors, with the density of conspecific seedlings playing a particularly important role. As seedling diameter increased, habitat factors gradually became more influential32. This shift likely occurred because larger seedlings developed greater resistance to fungal infections, reducing the impact of biotic pressures. Concurrently, their growth requirements for light, soil nutrients, and water made habitat factors increasingly important. Seedling survival rate was positively correlated with the density of conspecific seedlings across different diameter classes, it was negatively correlated with conspecific adult basal area when seedling diameter > 5 cm. We can indicate that less NDD affected the seedlings, although in other diameter levels this NDD was existed in the context of the Janzen–Connell hypothesis5.

At various diameter levels, higher conspecific seedling density significantly promoted seedling survival, further confirming the absence of density constraints. However, when seedling diameter was > 3 cm, a highly significant negative correlation emerged between the conspecific adult basal area and seedling survival rate. This trend was likely due to the increasing demand for light as seedlings grew61,62. Larger trees with well-developed crowns intercepted a substantial portion of available light, reducing light penetration to the forest floor and leading to higher seedling mortality.

Soil conditions also played a role in seedling survival. A significant positive correlation was found between soil PC1 (representing SOM and nitrogen content) and the survival of larger-diameter seedlings. This suggests that SOM and nitrogen elements facilitate seedling growth. As seedlings mature, their root systems absorb substantial organic matter and nitrogen, converting these nutrients into essential compounds through photosynthesis and storing them for sustained growth. At the > 5-cm diameter level, herbaceous coverage and elevation had a significant negative effect on seedling survival rate. High herbaceous coverage likely impedes root oxygen absorption, leading to root decay and seedling mortality. Notably, it was more difficult for seedlings to survive in areas with greater canopy density. As seedlings grew, their demand for light increased, but excessive canopy closure and low light intensity limited their ability to meet these growing needs42. We also found that NDD for larger seedlings was affected by larger conspecific adult ones. This may be attributed to increase the neighborhood of conspecific adults suppress seedling survival by increasing the probability of encounter with pathogens2.

Analysis of factors affecting seedling survival at different height class levels

The seedling density of conspecifics had a significant impact on seedling survival rate across different height levels. Except for a negative correlation at the < 0.3-m height level and a positive correlation at the 1.5–2.0-m height level, significant positive correlations were observed at other height levels. This indicated that NDD was absent at most heights but existed at a low level in lower height classes, likely due to competition among seedlings and the presence of natural enemies9. Previous studies have shown that natural enemies are a primary driver of NDD63,64. However, in our study area, L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii was the dominant tree species, and the absence of natural enemies may have prevented NDD. When seedling height was > 2 m, a significant negative correlation was observed between seedling survival and NDD for the conspecific adult basal area. This was likely due to increased competition for light as seedlings grew taller, with conspecific adult basal area being proportional to canopy density. It also may due to the higher seedlings were scattered around conspecific adult ones as a result of dispersal limitation, thus causing above phenomenon65.

Soil factors were also key determinants of seedling survival. A significant positive correlation between soil PC1 and seedling survival rate suggested that higher levels of SOM, TN, and AP promoted seedling survival. This was because seedlings, with their fragile roots and stems, are unable to store large amounts of nutrients and instead rely on readily available soil nutrients. Thus, more fertile soil is conducive to seedling survival rate53. There were also significant negative correlations between seedling survival rate and both canopy density and height level. Light availability is a critical environmental factor for seedling growth, and increased light penetration in the understory can enhance seedling height and survival66,67.

Analysis of factors affecting seedling survival at different age-class levels

At the age level, no NDD was observed, and seedling survival rate was significantly positively correlated with the density of conspecific seedlings. This indicated that individuals of the same species facilitated each other’s survival, a result that differed from previous studies, possibly due to variations in terrain and forest type67,68. Additionally, latitudinal differences may have contributed to this contrasting outcome. A significant negative correlation was observed between seedling survival rate in the > 8-years age class and the conspecific adult basal area, similar to findings at the diameter level. This indicated that larger basal areas at breast height reduced the survival of older seedlings owing to competition for resources. When seedlings were > 12 years old, herbaceous coverage had a significant negative effect on their survival. High herbaceous coverage often indicates a diverse herbaceous community that competes for nutrients and light, thereby restricting seedling growth62.

Soil factors also played a crucial role in seedling survival at different age levels. As seedlings matured, soil factors became increasingly significant. When seedlings were > 8 years old, SOM and nitrogen content had significant positive effects on survival. Additionally, TP and AP had significant positive effects on seedling survival rate at ages > 12 years, highlighting the importance of nutrient availability in later growth stages. As seedlings consume their internal nutrient reserves, they become more dependent on soil nutrients for sustained growth55. Furthermore, the survival of older seedlings was significantly negatively correlated with canopy density, indicating that better light conditions were more favorable for their growth. Canopy width also had a significant impact on seedling survival rate. As L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii is a heliophilous tree species, it requires substantial light for optimal growth and development69.

In the process of seedling regeneration and growth, seedlings will be affected by biotic and abiotic factors. In this study, the dynamics of seedlings in 18 sample plots of L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii forest in Guandi mountain were studied and the survival influencing factors were analyzed. Although light, terrain factors and soil nutrients were added to abiotic factors, the lack of water data would underestimate the impact of abiotic factors on seedling survival. Given the significant influence of water availability on seedling survival. Future studies should prioritize the impact of soil moisture or rainfall data on seedling survival. At the same time, we should also consider the condition of seed germination, which can further understand the condition of seed germination and its impact on seedling survival, then provide help for further exploration of seedling regeneration.

Conclusion

In this study, across different analysis levels, the full model provided the best fit. The density of conspecific seedlings had a significant positive effect on seedling survival, with herbaceous coverage and slope also positively influencing seedling survival rate. The absence of NDD suggests that seedling survival in L. gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii artificial forest is not density-limited during early stages and that habitat factors played a critical role in seedling survival. Moreover, our findings suggest that the relative influence of habitat heterogeneity and biotic density is stage-dependent and modulated by ontogenetic traits. We suggest that optimizing planting density and conserving community heterogeneity for sustainable plantation management. Our results might give better theoretical contributions to understanding forest regeneration and succession mechanisms.

Data availability

Data supporting the results of the study can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Schmid, U., Bigler, C., Frehner, M. & Bugmann, H. Abiotic and biotic determinants of height growth of Picea abies regeneration in small forest gaps in the Swiss alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 490, 119076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119076 (2021).

Yan, Y., Zhang, C. Y., Wang, Y. X., Zhao, X. H. & von Gadow, K. Drivers of seedling survival in a temperate forest and their relative importance at three stages of succession. Ecol. Evol. 5, 4287–4299. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1688 (2015).

Connell, J. H. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs: high diversity of trees and corals is maintained only in a nonequilibrium state. Science 199, 1302–1310. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.199.4335.1302 (1978).

Hutchinson, G. E. The paradox of the plankton. Am. Nat. 95, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1086/282171 (1961).

Janzen, D. H. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. Am. Nat. 104, 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1086/282687 (1970).

Bannister, J. R., Kremer, K., Carrasco-Farias, N. & Galindo, N. Importance of structure for species richness and tree species regeneration niches in old-growth Patagonian swamp forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 401, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.06.052 (2017).

Hubbell, S. P. Neutral theory and the evolution of ecological equivalence. Ecology 87, 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658 (2006). (2006)87[1387:ntateo]2.0.co;2.

Schamp, B. et al. The assembly of plant communities in relation to overlap in mycorrhizal and pathogenic root fungi. Funct. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14749 (2025).

Wright, J. S. Plant diversity in tropical forests: a review of mechanisms of species coexistence. Oecologia 130, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100809 (2002).

Comita, L. S. & Hubbell, S. P. Local neighborhood and species’ shade tolerance influence survival in a diverse seedling bank. Ecology 90, 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0451.1 (2009).

Winkler, M., Huelber, K. & Hietz, P. Effect of canopy position on germination and seedling survival of epiphytic bromeliads in a Mexican humid montane forest. Ann. Bot-London. 95, 1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci115 (2005).

Zeng, X. et al. Differences in response of tree species at different succession stages to neighborhood competition. Forests 15, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15030435 (2024).

Luo, Z. et al. Effect of species-independent conspecific and heterospecific density dependence is contingent on seedling growth stage, season, and climate conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 565, 122045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122045 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Navigating neighborhoods: Density, size, and species diversity influences on tree survival in subtropical secondary forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 572, 122311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122311 (2024).

Zhou, G., Qin, Y., Petticord, D., Qiao, X. & Jiang, M. Plant-ant interactions mediate herbivore-induced conspecific negative density dependence in a subtropical forest. Sci. Total Environ. 927, 172163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172163 (2024).

Ma, R. et al. Recruitment dynamics in a tropical karst seasonal rain forest: revealing complex processes from Spatial patterns. For. Ecol. Manag. 553, 121610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121610 (2024).

Kuang, X. et al. Conspecific density dependence and community structure: insights from 11 years of monitoring in an old-growth temperate forest in Northeast China. Ecol. Evol. 7, 5191–5200. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3050 (2017).

Pu, X., Zhu, Y. & Jin, G. Effects of local biotic neighbors and habitat heterogeneity on seedling survival in a spruce-fir Valley forest, Northeastern China. Ecol. Evol. 7, 4582–4591. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3030 (2017).

Stanley Harpole, W. & Tilman, D. Non-neutral patterns of species abundance in grassland communities. Ecol. Lett. 9, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00836.x (2006).

Guo, Y. et al. Seasonal changes in cambium activity from active to dormant stage affect the formation of secondary xylem in Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Tree Physiol. 42, 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpab115 (2021).

Yang, Z. et al. Predicting Individual Tree Mortality of Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii in Temperate Forests Using Machine Learning Methods. Forests 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15020374 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Liao, J., Xu, C., Du, M. & Zhang, X. Optimizing variables selection of random forest to predict radial growth of larix Gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii in temperate regions. For. Ecol. Manag. 569, 122159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122159 (2024).

Liang, W. J. & Wei, X. Multivariate path analysis of factors influencing Larix principis-rupprechtii plantation regeneration in Northern China. Ecol. Ind. 129, 107886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107886 (2021).

Sariyildiz, T., Anderson, J. M. & Kucuk, M. Effects of tree species and topography on soil chemistry, litter quality, and decomposition in Northeast Turkey. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 1695–1706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.02.004 (2005).

Zhao, W. W., Sun, Y. J. & Gao, Y. F. Potential factors promoting the natural regeneration of Larix principis-rupprechtii in North China. PeerJ 11, e15809. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15809 (2023).

Clark, P. W. & D’Amato, A. W. Seedbed not rescue effect buffer the role of extreme precipitation on temperate forest regeneration. Ecology 104, e3926. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3926 (2023).

Murphy, S. J., Wiegand, T. & Comita, L. S. Distance-dependent seedling mortality and long-term spacing dynamics in a Neotropical forest community. Ecol. Lett. 20, 1469–1478. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12856 (2017).

Yang, X. Q. et al. Effects of simulated wind load on leaf photosynthesis and carbohydrate allocation in eight Quercus species. J. Biobased Mater. Bio. 11, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbmb.2017.1721 (2017).

Zhao, W. W., Liang, W. J., Han, Y. Z. & Wei, X. Characteristics and factors influencing the natural regeneration of Larix principis-rupprechtii seedlings in Northern China. PeerJ 9, e12327. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12327 (2021).

Dong, X. D. et al. Changing characteristics And influencing factors of the soil microbial community during litter decomposition in a mixed Quercus acutissima Carruth. And Robinia Pseudoacacia L. forest in Northern China. Catena 196, 104811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104811 (2021).

Li, S. J. et al. Distribution patterns of desert plant diversity and relationship to soil properties in the Heihe river Basin, China. Ecosphere 9, e02355. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2355 (2018).

Bai, X. et al. Effects of local biotic neighbors and habitat heterogeneity on tree and shrub seedling survival in an old-growth temperate forest. Oecologia 170, 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2348-2 (2012).

Chen, L. et al. Community-level consequences of density dependence and habitat association in a subtropical broad-leaved forest. Ecol. Lett. 13, 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01468.x (2010).

Koller, A., Kunz, M., Perles-Garcia, M. D. & Oheimb, G. 3D structural complexity of forest stands is determined by the magnitude of inner and outer crown structural attributes of individual trees. Agric. For. Meteorol. 363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2025.110424 (2025).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Comita, L. S. & Engelbrecht, B. M. Seasonal and Spatial variation in water availability drive habitat associations in a tropical forest. Ecology 90, 2755–2765. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1482.1 (2009).

Webb, C. O., Gilbert, G. S. & Donoghue, M. J. Phylodiversity-dependent seedling mortality, size structure, and disease in a Bornean rain forest. Ecology 87, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[123:psmssa]2.0.co;2 (2006).

Bertness, M. D. & Callaway, R. Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 191–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(94)90088-4 (1994).

Ziffer-Berger, J., Weisberg, P. J., Cablk, M. E. & Osem, Y. Spatial patterns provide support for the stress-gradient hypothesis over a range-wide aridity gradient. J. Arid Environ. 102, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2013.11.006 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. Effects of biotic/abiotic factors on the seedling regeneration of Dacrydium pectinatum formations in tropical montane forests on Hainan Island, China. Global Ecol. Conserv. 24, e01370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01370 (2020).

Sangsupan, H. A., Hibbs, D. E., Withrow-Robinson, B. A. & Elliott, S. Effect of microsite light on survival and growth of understory natural regeneration during restoration of seasonally dry tropical forest in upland Northern Thailand. For. Ecol. Manag. 489, 119061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119061 (2021).

Hu, J. J., Luo, C. C., Turkington, R. & Zhou, Z. K. Effects of herbivores and litter on lithocarpus hancei seed germination and seedling survival in the understorey of a high diversity forest in SW China. Plant. Ecol. 217, 1429–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-016-0610-0 (2016).

Gavinet, J., Prévosto, B. & Fernandez, C. Do shrubs facilitate oak seedling establishment in mediterranean pine forest understory? For. Ecol. Manag. 381, 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.09.045 (2016).

Hannula, S. E. et al. Persistence of plant-mediated microbial soil legacy effects in soil and inside roots. Nat. Commun. 12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25971-z (2021).

Lett, S. & Dorrepaal, E. Global drivers of tree seedling establishment at alpine treelines in a changing climate. Funct. Ecol. 32, 1666–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13137 (2018).

Sun, J. et al. Plant-soil feedback during biological invasions: effect of litter decomposition from an invasive plant (Sphagneticola trilobata) on its native congener (S. calendulacea). J. Plant. Ecol. 15, 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtab095 (2022).

Shi, H., Wen, Z., Paull, D. & Guo, M. A framework for quantifying the thermal buffering effect of microhabitats. Biol. Conserv. 204, 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.006 (2016).

Liu, Q. & Zhao, W. Plant-soil microbe feedbacks drive seedling establishment during secondary forest succession: the ‘successional stage hypothesis’. J. Plant. Ecol. 16. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtad021 (2023).

Stepniewska, H., Jankowiak, R., Bilanski, P. & Hausner, G. Structure and Abundance of Fusarium Communities Inhabiting the Litter of Beech Forests in Central Europe. Forests. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060811 (2021).

Oshima, C., Tokumoto, Y. & Nakagawa, M. Biotic and abiotic drivers of dipterocarp seedling survival following mast fruiting in Malaysian Borneo. J. Trop. Ecol. 31, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026646741400073x (2015).

Corrià-Ainslie, R., Camarero, J. J. & Toledo, M. Environmental heterogeneity and dispersal processes influence post-logging seedling establishment in a Chiquitano dry tropical forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 349, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.03.033 (2015).

Khurana, E. & Singh, J. Influence of seed size on seedling growth of albizia procera under different soil water levels. Ann. Bot-London. 86, 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.2000.1288 (2000).

Lv, K. et al. Regeneration characteristics and influencing factors of Woody plant on natural evergreen secondary broad-leaved forests in the subtropical, China. Global Ecol. Conserv. 42, e02394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2023.e02394 (2023).

Joshi, N. R. et al. Effect of assisted natural regeneration on forest biomass and carbon stocks in the living mountain lab (LML), Lalitpur, Nepal. Environ. Challenges. 14, 100858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100858 (2024).

Toledo-Garibaldi, M., Gallardo-Hernández, C., Ulian, T. & Toledo-Aceves, T. Urban forests support natural regeneration of cloud forest trees and shrubs, albeit with limited occurrence of late-successional species. For. Ecol. Manag. 546, 121327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121327 (2023).

Li, J., Li, S., Liu, C., Guo, D. & Zhang, Q. Response of Chinese pine regeneration density to forest gap and slope aspect in Northern china: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 873, 162428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162428 (2023).

Haq, S. M., Calixto, E. S., Rashid, I., Srivastava, G. & Khuroo, A. A. Tree diversity, distribution and regeneration in major forest types along an extensive elevational gradient in Indian himalaya: implications for sustainable forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 506, 119968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119968 (2022).

Cantón, Y., Del Barrio, G., Solé-Benet, A. & Lázaro, R. Topographic controls on the Spatial distribution of ground cover in the Tabernas Badlands of SE Spain. Catena 55, 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(03)00108-5 (2004).

Gao, M. X., Qiao, Z. H., Hou, H. Y., Jin, G. Z. & Wu, D. H. Factors that affect the assembly of ground-dwelling beetles at small scales in primary mixed broadleaved-Korean pine forests in north-east China. Soil. Ecol. Lett. 2, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42832-019-0018-6 (2020).

Mascaro, J. et al. Controls over aboveground forest carbon density on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Biogeosciences 8, 1615–1629. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-1615-2011 (2011).

Erdozain, M., Bonet, J. A., Martínez de Aragón, J. & de-Miguel, S. Forest thinning and climate interactions driving early-stage regeneration dynamics of maritime pine in mediterranean areas. For. Ecol. Manag. 539, 121036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121036 (2023).

Johnson, D. J. et al. Canopy tree density and species influence tree regeneration patterns and Woody species diversity in a longleaf pine forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 490, 119082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119082 (2021).

Bell, T., Freckleton, R. P. & Lewis, O. T. Plant pathogens drive density-dependent seedling mortality in a tropical tree. Ecol. Lett. 9, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00905.x (2006).

Comita, L. S. et al. Testing predictions of the Janzen–Connell hypothesis: a meta-analysis of experimental evidence for distance‐and density‐dependent seed and seedling survival. J. Ecol. 102, 845–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12232 (2014).

He, F., Legendre, P. & Lafrankie, J. V. Distribution patterns of tree species in a Malaysia tropica rain forest. J. Veg. Sci. 8, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/3237248 (1997).

Barberis, I. M. & Tanner, E. V. Gaps and root trenching increase tree seedling growth in Panamanian semi-evergreen forest. Ecology 86, 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-0677 (2005).

Masaki, T. & Nakashizuka, T. Seedling demography of Swida controversa: effect of light and distance to conspecifics. Ecology 83, 3497–3507. https://doi.org/10.2307/3072098 (2002).

Metz, M. R. Does habitat specialization by seedlings contribute to the high diversity of a lowland rain forest? J. Ecol. 100, 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.01972.x (2012).

Lin, L. X., Comita, L. S., Zheng, Z. & Cao, M. Seasonal differentiation in density-dependent seedling survival in a tropical rain forest. J. Ecol. 100, 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.01964.x (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the project supported by Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No: 202303021212096), Scientific research project of Shanxi Province doctoral work award fund (No. SXBYKY2022146), and PhD initiates research projects (No: 2023BQ131).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weiwen Zhao: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—Original DraftWeiwen Zhao and Yanjun Sun: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Sun, Y. Drivers of natural regeneration seedling dynamics in a Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii artificial forest. Sci Rep 15, 39396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25747-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25747-1