Abstract

Natural bacterial contaminants in boar semen make it necessary to use preservative-level antibiotics in semen extenders to ensure long-term sperm viability and artificial insemination (AI) success. While concerns exist about the role of semen extender antibiotics in antimicrobial resistance (AMR), empirical evidence is lacking. This study examined microbiome and resistome dynamics in fecal samples of gilts from an organic farming operation, where AI is the primary source of antimicrobial exposure. Metagenomics was used to analyze microbial communities and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) across quarantine, breeding pen introduction, and post-AI production phases. The fecal microbiome was dominated by Bacillota and Bacteroidota. Microbial shifts were likely due to environmental and dietary adaptation, with no major changes observed post-AI. Among 168 identified ARGs, 89% were linked to drug resistance, primarily targeting tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, and macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins (MLS). The abundance of most ARGs decreased between arrival at the operation and 10 days after introduction into the breeding pen, with no major resistome changes post-AI. Neither exposure to previously inseminated females nor antibiotics in semen extenders increased fecal ARGs. This study found no evidence that rational antibiotic use in swine semen extender contributes to increased antimicrobial resistance in the swine fecal microbiome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial insemination (AI) is an important biotechnology used by pork producers. It allows semen collected from high genetic merit boars to be used with fewer geographical barriers to breed more females than would otherwise be possible with natural mating. Consequently, AI has facilitated the widespread and efficient distribution of economically important genes that accelerate genetic improvement. Commercial pork production efficiency, profit, and food security are directly tied to using AI1,2,3.

Collecting boar semen under sterile conditions is not a practical option and bacterial contamination from the boar’s prepuce, skin, and hair, as well as the environment is unavoidable even when strict sanitary procedures and minimum contamination collection techniques are used4,5. Porcine semen used for AI is usually preserved with cell-specific media (e.g., extenders) for several days at 16–18 °C. Unfortunately, the same characteristics that help extenders preserve semen viability (i.e., maintaining adequate osmolarity/pH, buffers, and providing metabolic substrates) also favor bacterial proliferation5,6. Bacterial contamination of extended semen can result in sperm agglutination, depressed sperm motility, increased sperm acrosome damage, and lower pregnancy rates6,7. Consequently, prudent use of preservative-level antibiotics in porcine semen extenders is paramount to ensure bacterial control and efficient application of AI biotechnology.

In general, misuse or overuse of antibiotics may facilitate selection pressure for the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacteria. Recently, there have been suggestions that preservative-level antibiotics in porcine semen extenders might contribute to AMR3,8,9. However, no empirical research has been conducted to support or refute these suggestions. Current thoughts are that low-level, long-term antibiotic exposure may have greater potential for selection of AMR bacteria than short-term, full-dose therapeutic antibiotic use10. Therefore, the suggestion that preservative-level antibiotics might lead to the emergence of AMR bacteria in porcine semen extender and then the potential of transferring the AMR bacteria to the microbiome of a porcine host is unclear.

Historically, detection of AMR in bacteria has been based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing after in vitro growth. Next-generation sequencing approaches such as metagenomics can sequence whole genomes of complex microbial ecosystems and has emerged as a single, rapid, and comprehensive laboratory test that allows not only characterization of individual bacterial strains within a collection of microbes (microbiome), but also identify the type and abundance of diverse genes that are known to confer resistance to different antimicrobials, collectively referred to as the resistome11,12. Metagenomics has been primarily used in survey and monitoring studies, but recognition of its power has led to its application in empirical studies evaluating the effects of different antibiotic treatments on the resistome13,14. Application of metagenomic approaches to determine the effects of using antimicrobials in semen extenders on the microbial resistome and the possibility of transferring AMR genes to the gut microbiomes of porcine hosts has not been explored.

Selective pressure on AMR genes is lower in organic operations compared to conventional operations that routinely use antibiotics. Since abundances of AMR genes in conventional farms are diverse and dynamic, the effect of trace-level antimicrobials may not be identified. As such, organic operations provide an ideal, opportunistic model to assess changes in the resistome patterns of gilts with minimal interferences from other potential AMR confounders. We hypothesized that exposure to previously inseminated gilts and direct exposure to semen containing antibiotics during insemination would increase the prevalence of AMR genes in the fecal microbiome of gilts. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine the temporal changes in microbiome and resistome profiles in fecal samples of gilts after their introduction into an organic herd and insemination with extended semen containing typical preservative-level antibiotics.

Results

Samples and data quality control

Mean gilt weight at arrival/start (TP1) of quarantine (24 weeks of age; loaded truck/empty truck difference) was 123 kg. At the end of quarantine (27 weeks of age; TP2), gilts weighed 141 ± 12 kg (mean ± SD). The gilts were introduced to the breeding pen (TP3) at least 10 d before insemination (TP4-TP6). Artificial insemination was performed 7 to 9 weeks after arrival at the breeding operation, approximately 1.5 weeks after gilts were introduced into the main breeding pen (TP7). A 67% (8/12) conception rate was obtained from first services performed in this study.

Approximately two billion raw paired-end reads were generated from 120 samples. Six samples had few reads and were excluded from the analysis, including two samples from the first replicate (TP4 and TP10) and four samples from the second replicate (2 TP1, TP2 and TP4). The total number of paired end reads for each sequenced sample was 20.5 ± 8.7 million (range 0.54 to 39.2 million). After trimming and quality filtering, an average of 17.4% of reads were removed (12.5% during Trimmomatic filtering and 4.9% during host filtering). The number of reads per sample used for microbiome and resistome analysis was 16.9 ± 7.4 million (range 0.46 to 33.9 million) (Supplementary Table S1).

Microbiome and resistome variation

Temporal changes in the microbiome and resistome at the community level were evaluated using Bray-Curtis analysis based on taxonomic and ARG assignments (Fig. 1). Significant effects of test period (R2 = 0.31, P < 0.001) and replicate-by-test period interaction (R2 = 0.09, P < 0.005) were observed on microbial communities. Although significant, the replicate-by-test period interactions had very low R2 values. While the differences between Replicates 1 and 2 at each time were small, differences at TP7 and TP8 were more pronounced (P < 0.05; R2 = 0.26 to 0.39). Homogeneity of dispersion analysis showed that at each timepoint, dispersions between replicates did not differ P > 0.05, range 0.07 to 0.98). Therefore, the R2 values reflected true differences in community composition, not differences in variability between replicates. In both replicates, TP1 clustered separately (P < 0.05) from all other test periods. The microbiome varied (P < 0.05) from TP2 through TP4 before becoming homogeneous from seven days after introduction into the breeding pen (TP5) through the end of the study. For resistome-based communities, significant effects of test period (R2 = 0.27, P < 0.001) were observed, but there were no differences between replicates within test period. Resistome community patterns were similar to those of microbiome patterns, with variations observed for most test periods until TP5. Variations in the resistome between 10 days after introduction into the breeding pen and 10 days after AI (TP6 to TP10) were minimal in both replicates.

Principal coordinate analysis plots (left) depicting Bray-Curtis distances calculated for each pair of samples for microbiome (A) and resistome (B) in fecal samples from gilts (n = 12; 6/replicate) in an organic farming operation. ● First replicate, ▲ Second replicate. Time effects (PERMANOVA) for microbiome and resistome for each replicate (right). Significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences are highlighted. TP1: Arrival/quarantine start, TP2: Introduction to training pen, TP3: Introduction to breeding pen, TP4: breeding pen 3 d, TP5: breeding pen 7 d, TP6: breeding pen 10 d, TP7: Artificial insemination (AI), TP8: AI plus 3 d, TP9: AI plus 7 d, TP10: AI plus 10 d.

Temporal Microbiome changes

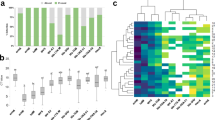

Although 50 bacterial phyla were identified among fecal microbial populations, four phyla accounted for 94% to 97% of the total sequence reads across replicates and test periods (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). Bacillota was the most predominant phylum, accounting for 57.1% to 71.5% of the total microbiome. The next most predominant phyla were Bacteroidota (9.2% to 18.3%), Pseudomonodota (8.3% to 13.4%), and Actinomycetota (5.0% to 13.0%). All other 46 identified phyla accounted for 3.3% to 5.8% of the total microbiome. There was a general trend for Bacillota to decrease from arrival to the conclusion of the study, consistent across both the replicates. However, the other three major phyla including Pseudomonodata, Bacteroidota and Actinomycota fluctuated through the quarantine, adaptation to breeding pen, and through AI periods. There were test period (P = 0.05) and replicate-by-test period interaction (P < 0.05) effects on the phylum Bacteroidota. This phylum was greater (P < 0.1) at the end of the training period (TP3) than at the end of quarantine (TP2) or three days after introduction into the breeding pen (TP4) in the first replicate. Reads were also greater (P < 0.05) at TP3 than seven days after AI (TP9) in the second replicate. There was a test period (P < 0.0001) effect on Actinomycetota, as the proportion of reads for this phylum increased after arrival. There were no significant changes in phyla distribution after AI.

Relative abundance of sequence reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) for different bacteria phylum in fecal samples from gilts in an organic farming operation in two replicates (R1 and R2; n = 12; 6/replicate). TP1: Arrival/quarantine start, TP2: Introduction to training pen, TP3: Introduction to breeding pen, TP4: breeding pen 3 d, TP5: breeding pen 7 d, TP6: breeding pen 10 d, TP7: Artificial insemination (AI), TP8: AI plus 3 d, TP9: AI plus 7 d, TP10: AI plus 10 d.

Throughout the study, a total of 340 bacteria species were identified in the fecal microbiome. Bacteria identified in > 1% of sequence reads at any time during the study included 38 species (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3). When sequence reads for these bacteria were analyzed, there were replicate (P < 0.001) effects on four bacterial species, test period (P < 0.05) effects on 18 bacterial species, and replicate-by-test period interaction (P < 0.05) effects on 10 bacterial species. The bacterial community composition at arrival (TP1) showed a distinct profile of bacterial species, with a predominance of Streptococcus alactolyticus (23.1%), Segatella copri (6.1%), Escherchia coli (5.1%), Lactobacillus johnsonii (4.2%), and Limosilactobacillus reuteri (2.9%). Streptococcus alactolyticus and L. johnsonii populations decreased (P < 0.05) by the end of quarantine (TP2) and continued to decrease afterwards making up < 1% of the population by the end of the study. In contrast, some bacterial species such as Lactobacillus amylovorous, Turicibacter billis, Ligilactobacillus ruminis, Vescimonas fastidiosa, Megasphaera elsdenii, and Clostridium beijerinckii were minimal at arrival, but increased either on TP2 or gradually increased over time. By the conclusion of the study, L. amylovorus and S. copri were the predominant bacteria in the fecal microbiome. Changes after AI (TP7) were observed only for Sodaliphilus pleomorphus, Roseburia sp. 831b, and Dialister succinatiphilus; all these populations increased (P < 0.05) by either seven or 10 days after AI.

Abundance of sequence reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) for different bacteria species in fecal samples from gilts (n = 12) in an organic farming operation. TP1: Arrival/quarantine start, TP2: Introduction to training pen, TP3: Introduction to breeding pen, TP4: breeding pen 3 d, TP5: breeding pen 7 d, TP6: breeding pen 10 d, TP7: Artificial insemination (AI), TP8: AI plus 3 d, TP9: AI plus 7 d, TP10: AI plus 10 d.

AMR gene diversity and abundance

A total of 168 individual ARGs were identified by comparing sequence reads to the MEGARes 3.0 database. The resistome profiles included resistance mechanisms predominantly to drugs, but also to multi-compounds, biocides, and metals. Across replicates and test periods, sequence reads associated with biocides, metals, and multi-compound resistance represented 1.8%, 5.5%, and 3.5% of the resistome, respectively, with the remaining ARGs (89.2%) associated with drug resistance (Supplementary Table S4). As the focus of the study is on antimicrobials, only comparisons relevant to drugs will be reported from here. Across various drug resistance genes, this study identified ARGs conferring resistance to 14 different drug classes (Supplementary Table S5). There were no replicate effects on any of the drug resistome classes and the five most abundant were, in decreasing order, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, MLS, nucleosides, and beta-lactams (Fig. 4). Drug resistance was associated with 29 different mechanisms (Table 1). The only replicate-by-test period interaction effects (P < 0.05) were observed for MLS and Multi-drug resistance ATP-binding Cassette (ABC) efflux pumps. When test period effects were evaluated, sequence reads associated with 14 mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance decreased (P < 0.05) throughout the study.

Abundance of sequence reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) of antimicrobial resistance genes associated with different drug classes in fecal samples from gilts in an organic farming operation in two replicates (R1 and R2; n = 12; 6/replicate). TP1: Arrival/quarantine start, TP2: Introduction to training pen, TP3: Introduction to breeding pen, TP4: breeding pen 3 d, TP5: breeding pen 7 d, TP6: breeding pen 10 d, TP7: Artificial insemination (AI), TP8: AI plus 3 d, TP9: AI plus 7 d, TP10: AI plus 10 d.

There were replicate-by-test period interaction effects (P < 0.05) for sequence reads of two tetracycline genes and four MLS genes, but the only replicate effect (P < 0.05) was observed for tet(B). Test period effects were observed for various ARGs, but when compared to TP1, most of those remained unchanged or decreased throughout the study (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S6). The most abundant ARGs were those conferring resistance to tetracyclines. While the overall abundance of tetracycline-resistant ARGs generally declined from TP1 through TP10, the reduction was more pronounced once the gilts entered the breeding pen, continuing through insemination and up to 10 days post-insemination. The most prevalent mechanism of resistance, representing 53% of the resistome across test periods, was tetracycline resistance ribosomal protection proteins (RPP). Sequence reads for these genes decreased (P < 0.05) at the end of the training period (TP3) and again seven days after introduction into the breeding pen (TP5). The RPPs included, in order of decreasing abundance, tet(W), tet(O), tet(40), tet(Q), and tet(44). Although sequence reads for tet(W) and tet(O) decreased (P < 0.05 to P < 0.1) three days after introduction into the breeding pen, these remained the predominant ARGs throughout the study. Sequence reads for tet(40) and tet(44) also decreased (P < 0.05) three to seven days after introduction into the breeding pen. The second most prevalent resistance mechanism was tetracycline resistance Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) efflux pumps, which sequence reads also decreased (P < 0.05) throughout the study, but with shifts observed three days after introduction into the breeding pen (T4) and three days after AI (T8). The MFS efflux pumps included, in order of decreasing abundance, tet(L), tet(B), tet(A), and tetB(P). Sequence reads for tet(L) decreased (P < 0.05) seven days after introduction into the breeding pen.

Heatmap of number of reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) of antimicrobial resistance genes in fecal samples from gilts (n = 12) in an organic farming operation. TP1: Arrival/quarantine start, TP2: Introduction to training pen, TP3: Introduction to breeding pen, TP4: breeding pen 3 d, TP5: breeding pen 7 d, TP6: breeding pen 10 d, TP7: Artificial insemination (AI), TP8: AI plus 3 d, TP9: AI plus 7 d, TP10: AI plus 10 d.

The second most abundant ARGs were those conferring resistance to aminoglycosides. The predominant mechanisms associated with aminoglycoside resistance were aminoglycoside O-nucleotidyltransferases, including ant(6) and ant(9), and aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases, including aph(2’’)and aph(3’’)-II. Transferases primarily function by modifying aminoglycosides, preventing their binding to ribosomal proteins. Sequence reads for aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases ARGs decreased (P < 0.05) seven days after introduction into the breeding pen (TP5) and reads for ant(6) decreased at the time of AI (TP7). Other resistance mechanisms included 16 S ribosomal subunit modification (RRS, rpsL), efflux pumps (KDPE), and N-acetyltransferases (aac(6′)), but these were much less abundant.

The third most abundant ARGs were those conferring resistance to MLS antimicrobials. Lincosamide nucleotidyltransferases was the predominant MLS resistance mechanism and sequence reads did not change significantly throughout the study. These included, in order of decreasing abundance, lnu(C), lnu(A), lnu(P), and lnu(B). Another common mechanism was 23 S rRNA methyltransferases, including erm(Q) and erm(F), and less abundantly, erm(G) and erm(B). These enzymes modify ribosomal targets to block the binding of macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins. Additional mechanisms were MFS and ABC efflux pumps (MEFA, MEFE, and lsa) and macrolide-resistant 23 S rRNA mutation (MLS23S). Sequence reads for MLS 23 S rRNA methyltransferases, macrolide-resistant 23 S rRNA mutation, macrolide phosphotransferases, and MLS ABC efflux pumps decreased (P < 0.05) three to 10 days after AI (TP8-TP10).

Among the less abundant ARGs, those conferring resistance to nucleosides included Streptothricin acetyltransferase (sat-1), which decreased (P < 0.05) three days after AI (TP8). Class A beta-lactamases were the predominant betalactam resistance mechanism and included predominantly ACI and CFX. Although sequence reads associated with this mechanism decreased at TP4, numbers rebounded at TP5. On the other hand, sequence reads associated with penicillin binding protein (pbp2, pbp4B, and ampH) decreased (P < 0.05) at TP8. In contrast, sequence reads for rifampin resistance associated with beta-subunit of RNA polymerase (rpoB) were the only ones that increased in the study. Abundance was minimal at arrival, but increased (P < 0.05) after quarantine (TP2). The genes that conferred resistance to aminocoumarins, bacitracin, cationic antimicrobial peptide, elfamycins, fosfomycins, lipopeptides, and mupirocin contribution were low in comparison with other drug classes.

Bacterial species associated with ARGs

There were moderate positive correlation coefficients (r2 = 0.5 to 0.74) between the abundance of several species and ARG abundance (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S7). Given that Bacillota is the most abundant phylum, its lineages were commonly associated with variations in ARG abundance, which is an expected outcome. Among tetracycline resistance genes, S. alactolyticus abundance was associated with tet(O) and tet(L), whereas abundances of T. bilis, Turicibacter sp. H121, Romboutsia ilealis, and Clostridium butyricum were associated with tet(B) abundance. Variations in the populations of these bacteria were also associated with variation of several MLS resistance genes, including erm(Q), lsa, lnu(B), and lnu(P). Significant correlations were also observed for aminoglycoside resistance genes ant(6) and ant(9), but the correlations were lower (r2 < 0.5). Variations in the abundances of M. elsdeni and Ligilactobacillus ruminis, along with the Bacteroidota S. copri and Segatella hominis were associated with the betalactam resistance genes ACI1 and cfx. Abundance of two known pathogens, Bacteroides fragilis and E. coli, were associated with the MLS23S gene. The only Actinomycetota that fulfilled inclusion criteria for this analysis was Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, but most correlation coefficients between the abundance of this species and abundance of various ARG were low.

Discussion

This study describes the dynamics of the fecal resistome in gilts, with a focus on the microbial populations and ARG changes as females are introduced into an organic farming operation. Significant microbiome shifts occurred until one week after gilts were introduced into their breeding pen. Microbiome changes were not always associated with changes in the resistome, but resistome changes seemed to always be associated with shifts in the microbiome. Exposure to previously AI-bred females and the AI process itself was not associated with significant changes in the fecal resistome. The study was conducted in an organic operation, but breeding practices, including semen extenders, type of extender antibiotics and their concentrations, insemination volume (directly related to antibiotic dosage), and insemination frequency followed customary practices used in the swine industry. Therefore, the findings of this study might be extrapolated to non-organic swine production systems.

Although replicates were conducted just six weeks apart and all other conditions remained similar throughout the study, there was a small but significant replicate effect on the microbiome. Variations among animals even under the same housing, feeding, and living conditions have been reported in sows raised without antibiotics15. Since there were no differences in the microbiome between replicates at the time of arrival at the Swine Center, differences observed between the two replicates seemed to be the result of the conditions at the organic farming operation. Community profiles as analyzed using Bray Curtis across the 10 time points investigated in this study indicate that the microbiome changed significantly as gilts transitioned into the breeding herd. The microbiome at the time of arrival at the Swine Center differed from all other time points. This was not surprising, since gilts were supplied by another commercial operator and had grown in a completely different facility. In a longitudinal study, significant shifts in the bacterial community and structure were observed among animals with ages ranging from piglets to breeding adults16. Microbiome changes occurred until one week after the gilts were introduced into the breeding pen in the present study. The period when most microbiome changes occurred coincided with changes in housing (quarantine to training pen to breeding pen) and initial exposure to other pigs. Contact with different environments and transmission of bacteria from the excreta of different animals were likely behind these microbiome shifts17,18. However, the microbiome quickly stabilized when gilts were kept under stable housing conditions with a relatively stable group of gilt cohorts.

The bacterial phyla integrating the fecal microbiome in the present study was consistent with other reports in non-organic swine operations describing a large predominance of Bacillota and Bacteroidota16,19. The slight but gradual decrease in Bacillota populations over time might indicate changes in gut conditions as the gilts were integrated into the breeding herd. Conversely, Actinomycetota populations seemed to increase after quarantine, which could reflect shifts in microbial communities as the gilts adapted to new dietary or environmental conditions. The relative stability of Bacteroidota populations throughout the study suggests that this group may be more resilient to the changes associated with the animals’ quarantine and integration into the breeding herd. Contrary to phyla, there is considerable variation in bacterial species-level bacterial microbiome composition in pigs. Nonetheless, Segatella spp., Lactobacillus spp., and E. coli are among the most abundant in recent studies16,20,21. In the present study, temporal changes in bacterial species composition were particularly pronounced for Lactobacillus amylovorus, which became a predominant species at the end of the study. Lactobacillus amylovorus was present in feces at arrival, but with lower abundance than Lactobacillus johnsonii. The latter population practically disappeared during quarantine, whereas the former thrived. This shift could reflect the gilts’ adaptation to the breeding environment, as Lactobacillus species are known to thrive in the gastrointestinal tract under stable conditions and are capable of suppressing other microorganisms that might be deleterious to host health22. A different pattern was observed for Streptococcus alactolyticus, a commensal colonizer of the gastrointestinal tract rarely isolated in pigs but that can act as an opportunistic pathogen23. The S. alactolyticus population was abundant upon arrival but declined significantly throughout the study. These results highlight the dynamic nature of the microbiome in response to environmental and dietary changes.

The variety of ARG genes in the present study was similar to that reported in non-organic swine operations in the UK24 but lower than most other studies reporting a range of 257 to 829 unique ARG present in pig feces15,16,21. Various levels of antibiotic resistance will remain in the healthy pig gut even when antibiotics are not used. Bacteria can be intrinsically resistant to certain antibiotics25, and bacterial strains present across populations have developed under different antibiotic selective pressure18,26. Temporal Bray-Curtis patterns suggest that shifts in microbiome communities do not necessarily accompany changes in the resistome, but that changes in the resistome are usually accompanied by changes in the microbiome27. Previous studies have reported that the composition of the resistome was strongly influenced by the composition of the microbiota15,16,20. Across nine European countries, much of the between-country variation in the resistome was explained by bacteriome differences28. The greatest ARG abundance was observed at the time gilts arrived at the Swine Center. Vertical transmission of resistance genes from sow to piglet can occur through the birth canal or through close physical contact after birth. Piglets may also acquire their resistome through nursing, as the bacteria present with the mother’s mammary glands may include resistant strains. The detection of high levels of ARG in the gut microbiome within 48 h post birth in piglets has been reported21. Although the presence and abundance of several ARG changes significantly as pigs transition from nursery to market age (or breeding), the resistome becomes more stable in older pigs16,21,29.

The resistome identified in the present study was consistent with other reports in non-organic swine operations describing a large predominance of genes related to tetracycline resistance, and significant presence of genes related to aminoglycoside and MLS resistance15,16,21,28,30. Across boars, sows, newborn piglets, weaning piglets, nursery piglets, fattening pigs and finishing pigs on a commercial farm in China, 11 out of the 20 more abundant ARGs were related to tetracycline resistance, including similar genes to those observed in the present study tet(W), tet(M), tet(Q), tet(40), tet(44), tet(A), tet(O) and tet(L)16. Reports of significant aminoglycoside resistance genes have included aadE, aph(3″), ant(9), whereas significant MLS ARG include erm(B), erm(F), erm(G), lsa, mef(A), LnuC, and cfxA15,16,28. Some authors have suggested that the resistome observed under low antibiotic usage could be considered the minimum natural resistome15. This knowledge is important since resistomes that differ from the natural minimum could be used to identify antibiotic level use. Two aspects of the resistome in the present study seemed different from most studies conducted in commercial conditions with greater antibiotic use pressure. First, the resistome in the present study did not contain key ARG classes identified in several studies, including chloramphenicol and vancomycin16,28. Second, in the present study multigenic antibiotic resistance seemed limited mostly to some Bacilli and Clostridia species. E. coli was associated almost exclusively with MLS23S gene in the present study; associations with genes in other antibiotics classes were weaker, if observed at all. In contrast, E. coli harbored the largest number of ARGs (96 out of 194) in farms in China, and 55 genes conferred resistance to at least one of fluoroquinolone, peptide, and macrolide antibiotics17. In another study also in China, Shigella spp. and Escherichia spp. populations were associated with multidrug resistance genes and MLS resistance genes; the relative abundance of E. coli being associated with most of the variation of the ARGs16.

Gilts were exposed to previously AI-bred females twice during the study. First, gilts had fenceline contact with multiparous sows during the 3 weeks of training (between TP2 and TP3). Then, when the gilts were introduced into the breeding pen with older gilts (TP6 = 10 days after introduction). Neither exposure to other previously AI-bred females, nor insemination over one estrus, resulted in any increased fecal ARGs. Most changes in the resistome occurred before AI. Changes in the resistome before AI indicated a reduction in ARG abundance for the main antibiotics used in veterinary practice as gilts became integrated into the organic herd. Compared with the day of arrival at the Swine Center, tetracycline ARGs decreased soon after the gilts were introduced into the breeding pen. Reductions in aminoglycoside ARGs required slightly longer and were observed until three days after AI. This study was performed under customary management conditions, where estrus detection is performed daily, and gilts are artificially inseminated twice or thrice while exhibiting estrus. Subsets of gilts in the breeding pen are theoretically being exposed to antibiotics (i.e., females are being inseminated). Therefore, the overall decrease in ARG abundance as the gilts’ resistome adapted to those of the older gilts after introduction into the breeding pen suggests that exposure to antibiotics from extended semen did not promote fecal resistance selection in this operation’s breeding herd. In addition, when gilts were themselves artificially inseminated with extended semen containing antibiotics, there were only minimal changes to the fecal microbiome and no significant changes to the fecal resistome.

The fecal resistome observed 10 days after introduction into the breeding pen could be considered representative of the herd. Therefore, the present findings suggest that ARG abundance in the herd was low and that the resistome of newly introduced animals likely changed to resemble that of the herd rather than the other way around. This was somewhat expected since older gilts outnumbered newly introduced virgin gilts approximately 3:1 in the breeding pen. Low ARG abundance in the present study might be a result of the limited use of antibiotics in this organic operation. At 23 weeks of age, pigs raised in environments with no antibiotic usage had lower intestinal abundance of proteins related to antimicrobial resistance (aph(39), arnA, mdtL, catB2, blaCTX-M-14) than pigs raised in commercial barns where tilmicosin and doxycycline were used for respiratory disease therapy and haquinol was used for gastrointestinal disease therapy31. All antibiotics included in the semen extender had primarily gram-negative activity. Aminoglycosides (e.g., apramycin, neomycin) can be used for the treatment of bacterial enteritis in pigs. Recommended therapeutic dose is 22 mg/kg PO daily for 7 to 14 d (Plumb’s Veterinary Drugs. https://app.plumbs.com). Therefore, the theoretical daily therapeutic dosage for a 150 kg gilt would be 3.3 g aminoglycoside/gilt. In contrast, the insemination doses contained a total of 0.0128 g of aminoglycoside in the AI breeding dose, or ~ 250-fold less than the therapeutic dose. Cationic polypeptides are effective against several multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa32. Recommended therapeutic dosage of cationic polypeptides is 100,000 IU/kg/day for 5 days in pigs33, or a theoretical 15 × 106 IU in a 150 kg study gilt. The insemination doses used in this study contained a total of 48,000 IU, or ~ 300-fold less cationic polypeptide than the therapeutic dose.

The effects of antibiotic treatment on the swine microbiome have been studied mostly in pigs < 3 months of age and after prolonged (> 7 days) oral administration of subtherapeutic doses. Most of such studies have demonstrated significant changes in gastrointestinal microbiome34. In addition, single dose parenteral antibiotic therapy has also been shown to affect the fecal microbiome and resistome. Antibiotic-specific variation in both duration and extent was observed for the fecal microbiome in 8 week-old piglets within 14 days after intramuscular administration of ceftiofur, penicillin, tetracycline, or tulathromycin19. Intramuscular florfenicol administration to piglets at 1 and 7 days of age resulted in microbiome changes accompanied by selection for florfenicol, aminoglycosides, betalactam, and sulfonamides ARG until 21 days of age35. These results contrast with the observations of the present study when gilts were administered preservative-level antibiotics mixed with semen extender and deposited directly into the uterus. Only minor changes to the fecal microbiome after AI were identified and changes to the resistome were not observed. The authors believe that differences in antibiotic dosage, treatment frequency, and pharmacokinetics associated with vehicle and route of administration likely contributed to these differences. Antibiotics added to boar semen extenders in low concentrations to prevent in vitro bacterial growth are likely to only reach negligeable circulating levels after insemination and do not seem to alter body microbiome populations and their resistance to antimicrobials.

This study provides valuable insights into the effects of preservative-level antibiotics added to semen extenders on the swine fecal resistome. While the findings are notable, further studies involving a larger number of females, females of different parity that had been subjected to multiple inseminations, and different extender antibiotics types and concentrations are warranted. In addition, incorporating microbiome and resistome analyses from semen and from reproductive tract samples might provide deeper insight into potential interconnections between ARGs in the reproductive and digestive tracts.

In conclusion, most changes to the fecal microbiome and resistome were observed as gilts were introduced into the organic farming operation and prior to insemination. The abundance of ARGs decreased as gilts were exposed to previously artificially inseminated females and remained unchanged after the gilts were inseminated with antibiotic containing extended semen themselves. In the conditions of the present study, rational use of antibiotics in semen extender was not associated with increased antimicrobial resistance in the swine fecal microbiome.

Materials and methods

Animals and design

All procedures involving live animals were performed according to the United States Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research and Training and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania (Protocol #807265). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. The study was conducted at the Swine Teaching and Research Center (Swine Center), New Bolton Center, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. The operation is certified as organic and the use of antibiotics in any capacity is very controlled. The facilities are environmentally controlled and maintain high standards of hygiene. Animals were subjected to standard immunization and herd health practices. Prior to arrival at the Swine Center, gilts received porcine circovirus type 2 vaccine at weaning (3 weeks of age), and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae and Lawsonia intracellularis vaccines at 5 weeks of age. Gilts later received swine influenza, porcine parvovirus, E. rhusiopathiae, and 5-way Leptospira vaccines within one week after arrival at the Swine Center, with a second dose administered three weeks after the first. All animals were fed a standard corn/soy gestation diet, meeting or exceeding NRC standards (National Research Council. Nutrient requirements of swine: eleventh revised edition. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2012. https://doi.org/1 0.17226/13298).

Twelve gilts (Topigs Norsvin, line TN70) provided by a commercial supplier were used in two replicates (6 gilts/replicate). The gilts used in the two replicates were sourced from the same supplier, and had similar genetics, age and weight at the beginning of each replicate. The replicates were conducted 6 weeks apart. Transport to the study facility lasted approximately 3:30 h; water and feed were not withheld prior to transportation. Gilts arrived at the Swine Center in groups of 12 at 24 weeks of age. Gilts were kept in quarantine for 3 weeks housed in group pens (2–3 gilts/pen, 1.2 m2/gilt). Gilts were fed in a collective feeder with 2.5 kg/gilt of a commercial dried diet once daily. Water was provided ad libitum by one nipple drinker per pen. After quarantine, gilts were transferred to a single group pen (2.7 m2/gilt) for training to use an automatic feeder system. Training continued for 3 weeks and during this time gilts continued to receive the same diet and amount as during quarantine, with ad libitum water provided by two nipple drinkers. During training, gilts had their first contact with approximately 30 older, multiparous sows via fenceline (2.75 m) contact. Once trained to use the feeder system, gilts were transferred into a single group breeding pen (total pen area: 165 m2; 3.3 m2 to 3.9 m2/gilt) with another 30 to 38 older gilts, many of which had already been previously artificially inseminated. Gilts moved to this housing system were then fed using an automatic feeding system (Compident Electronic feeding; Schauer Agrotronic), with ad libitum water provided by 4 nipple drinkers. All facilities had solid and slated concrete floor areas.

Estrus was detected once daily with the aid of a live boar. Once estrus was observed, gilts were artificially inseminated with semen provided by a commercial supplier. Insemination doses (40 mL; 35 to 40 million sperm/mL) were prepared with a commercial extender (NUTRIXcell+; IMV Technologies, L’Aigle, France) containing aminoglycosides (0.32 mg/mL) and a cationic polypeptide (1.2 × 103 IU/mL). Estrus gilts were inseminated using Golden Gilt 2 catheters (IMV Technologies) twice (n = 9) or thrice (n = 3), 24-h between inseminations. Fecal samples were obtained on the day of arrival, end of quarantine, end of feeder system training, 3, 7, and 10 days after introduction to main breeding pen, day of first artificial insemination, and 3, 7, and 10 days after first artificial insemination (Table 2). Samples were obtained from the rectum with a gloved hand and placed in 15 mL conical tubes. Samples were kept on ice, transported to the laboratory within 2 h post-harvest, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples using PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MOBIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA), as previously described11. For metagenomics, 2 µg of extracted DNA was used for a whole genome shotgun sequencing. Library preparation for shotgun sequencing was performed using Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (FC-131–1024, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The generated libraries were cleaned using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter; Brea, CA), normalized, and pooled and sequenced on Illumina NextSeq500 instrument (tight insert size of 250 bp for high-throughput sequencing from both ends by 2 × 150 bp) at the PennCHOP Microbiome Core at Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Bioinformatics analysis

The DNA sequences (FASTQ reads) from each sample were processed for adapter trimming and quality filtering using Trimmomatic (v0.36)36. Reads mapping to the host genome (susScr11) were identified and removed using Bowtie2 (v2.2.7)37. The remaining high-quality reads were taxonomically classified using Kraken238, with reference to all complete bacterial, archaeal, and viral genomes available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s RefSeq database (downloaded on October 22, 2024). Species abundances were estimated using Bracken (v2.0)39. Additionally, the quality-filtered reads were aligned to the MEGARes 3.0 database, which contains 7,868 antimicrobial resistance gene (ARG) sequences, using the BWA-MEM algorithm (v0.7.17). The AMR + + pipeline40 was then employed to characterize the ARG profiles. ARGs were normalized to reads per kilobase gene length per million mapped reads (RPKM). In addition, ARGs were also normalized to copies per million (CPM) and transformed using centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation. For the main analysis, RPKM-normalized data were used, while CPM-CLR normalized data are provided in Supplementary Table S8.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.1; https://www.r-project.org/). The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index was calculated for microbiome and resistome data and visualized using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), implemented in the vegan package, was used to assess the effects of replicate, time, and their interaction, with 999 permutations and AnimalID as a blocking factor. Homogeneity of multivariate dispersion was assessed using PERMDISP (implemented with the betadisper function) to compare replicates at each time point. A mixed linear model (lme4 package) was used to analyze individual taxonomic and ARG data, with replicate, time, and their interaction as fixed effects and AnimalID as a random effect. Microbiome and resistome features present in ≥ 75% of samples were included in the lmer analysis. Data were log-transformed to meet model assumptions. P-values for multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Tukey method (emmeans package). Spearman correlation analysis between bacterial taxa (relative abundance) and ARG abundance (RPKM) was performed using the cor.test function in R. Residuals from a linear model of species and ARG abundance were used for correlation analysis. Only taxa with a mean relative abundance > 1% and ARGs classified under the antimicrobial class type “Drugs” were included.

Data availability

The metagenomic sequencing data generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1244039.

References

Althouse, G. & Rossow, K. The potential risk of infectious disease dissemination via artificial insemination in swine. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 46, 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01863.x (2011).

Knox, R. Artificial insemination in pigs today. Theriogenology 85, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.07.009 (2016).

Waberski, D., Riesenbeck, A., Schulze, M., Weitze, K. F. & Johnson, L. Application of preserved Boar semen for artificial insemination: Past, present and future challenges. Theriogenology 137, 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2019.05.030 (2019).

Althouse, G. Sanitary procedures for the production of extended semen. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 43, 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01187.x (2008).

Althouse, G., Pierdon, M. & Lu, K. Thermotemporal dynamics of contaminant bacteria and antimicrobials in extended Porcine semen. Theriogenology 70, 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.07.010 (2008).

Kuster, C. & Althouse, G. The impact of bacteriospermia on Boar sperm storage and reproductive performance. Theriogenology 85, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.09.049 (2016).

Althouse, G., Kuster, C., Clark, S. & Weisiger, R. Field investigations of bacterial contaminants and their effects on extended Porcine semen. Theriogenology 53, 1167–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(00)00261-2 (2000).

Luther, A. M., Nguyen, T. Q., Verspohl, J. & Waberski, D. Antimicrobially active semen extenders allow the reduction of antibiotic use in pig insemination. Antibiotics 10, 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10111319 (2021).

Schulze, M., Nitsche-Melkus, E., Hensel, B., Jung, M. & Jakop, U. Antibiotics and their alternatives in artificial breeding in livestock. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 220, 106284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2020.106284 (2020).

WHO. The Medical Impact of the Use of Antimicrobials in Food Animals: Report of a WHO meeting. Report No. WHO/EMC/ZOO/97.4 1–24 (World Health Organization, 1997).

Pitta, D. W. et al. Metagenomic evidence of the prevalence and distribution patterns of antimicrobial resistance genes in dairy agroecosystems. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 13, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2015.2092 (2016).

Pitta, D. W. et al. The distribution of microbiomes and resistomes across farm environments in conventional and organic dairy herds in Pennsylvania. Environ. Microbiome. 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-020-00368-5 (2020).

Græsbøll, K. et al. Effect of Tetracycline treatment regimens on antibiotic resistance gene selection over time in nursery pigs. BMC Microbiol. 19, 269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1619-z (2019).

Hu, Q. et al. Effects of low-dose antibiotics on gut immunity and antibiotic resistomes in weaned piglets. Front. Immunol. 11, 903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00903 (2020).

Joyce, A., McCarthy, C. G. P., Murphy, S. & Walsh, F. Antibiotic resistomes of healthy pig faecal metagenomes. Microb. Genomics. 5 https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000272 (2019).

Ma, L. et al. Longitudinal metagenomic study reveals the dynamics of fecal antibiotic resistome in pigs throughout the lifetime. Anim. Microbiome. 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-023-00279-z (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Extensive metagenomic analysis of the Porcine gut resistome to identify indicators reflecting antimicrobial resistance. Microbiome 10, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01241-y (2022).

Munk, P. et al. The European livestock resistome. mSystems 9, e0132823. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01328-23 (2024).

Zeineldin, M., Aldridge, B., Blair, B., Kancer, K. & Lowe, J. Impact of parenteral antimicrobial administration on the structure and diversity of the fecal microbiota of growing pigs. Microb. Pathog. 118, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.03.035 (2018).

Holman, D. B., Gzyl, K. E., Mou, K. T. & Allen, H. K. Weaning Age and Its Effect on the Development of the Swine Gut Microbiome and Resistome. mSystems 6, e0068221 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00682-21

Gaire, T. N. et al. Age influences the Temporal dynamics of Microbiome and antimicrobial resistance genes among fecal bacteria in a cohort of production pigs. Anim. Microbiome. 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-022-00222-8 (2023).

Valeriano, V. D., Balolong, M. P. & Kang, D. K. Probiotic roles of Lactobacillus sp. in swine: insights from gut microbiota. J. Appl. Microbiol. 122, 554–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13364 (2017).

Renzhammer, R. et al. Detection of various Streptococcus spp. And their antimicrobial resistance patterns in clinical specimens from Austrian swine stocks. Antibiot. (Basel). 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9120893 (2020).

Pollock, J. et al. Resistance to change: AMR gene dynamics on a commercial pig farm with high antimicrobial usage. Sci. Rep. 10, 1708. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58659-3 (2020).

Blair, J. M. A., Webber, M. A., Baylay, A. J., Ogbolu, D. O. & Piddock, L. J. V. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3380 (2015).

Ma, T., McAllister, T. A. & Guan, L. L. A review of the resistome within the digestive tract of livestock. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 12, 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-021-00643-6 (2021).

Liu, S., Zhang, Z. & Ma, L. A review focusing on microbial vertical transmission during Sow pregnancy. Veterinary Sci. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci10020123 (2023).

Van Gompel, L. et al. The antimicrobial resistome in relation to antimicrobial use and biosecurity in pig farming, a metagenome-wide association study in nine European countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 865–876. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky518 (2019).

Gaire, T. N. et al. A longitudinal investigation of the effects of age, dietary fiber type and level, and injectable antimicrobials on the fecal Microbiome and antimicrobial resistance of finisher pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 100 https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skac217 (2022).

Ekhlas, D. et al. Metagenomic comparison of the faecal and environmental resistome on Irish commercial pig farms with and without zinc oxide and antimicrobial usage. Anim. Microbiome. 5, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-023-00283-3 (2023).

Buthasane, P. et al. Metaproteomic analysis of gut resistome in the cecal microbiota of fattening pigs Raised without antibiotics. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0222323. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.02223-23 (2023).

Shatri, G. & Tadi, P. Polymyxin. In StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing LLC, (2023). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557540/

Guyonnet, J. et al. Determination of a dosage regimen of colistin by pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic integration and modeling for treatment of G.I.T. Disease in pigs. Res. Vet. Sci. 88, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.09.001 (2010).

Zeineldin, M., Aldridge, B. & Lowe, J. Antimicrobial effects on swine Gastrointestinal microbiota and their accompanying antibiotic resistome. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01035 (2019).

Holman, D. B., Gzyl, K. E. & Kommadath, A. Florfenicol administration in piglets co-selects for multiple antimicrobial resistance genes. mSystems 9, e0125024 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01250-24

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 1–13 (2019).

Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 3, e104. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.104 (2017).

Bonin, N. et al. MEGARes and AMR++, v3.0: an updated comprehensive database of antimicrobial resistance determinants and an improved software pipeline for classification using high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D744–d752. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1047 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Pennsylvania Center for Poultry and Livestock Excellence (Grant #CPLE23-06). The authors thanks Dr. Thomas D. Parsons, Ms. Lori Stone, and the staff from the Swine Teaching and Research Center, New Bolton Center for their support and technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LFC Brito: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, data curation, writing - original draft; GC Althouse: Conceptualization, writing - review & editing; DW Pitta: Conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft; N Indugu: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing - review & editing; MP Sarmiento: methodology, writing - review & editing; NS Balamurugan: methodology, writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brito, L.F.C., Althouse, G.C., Pitta, D.W. et al. Temporal dynamics of the resistome in gilts raised in an organic operation in which semen used for artificial insemination is the primary source of antimicrobial exposure. Sci Rep 15, 41935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25776-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25776-w