Abstract

Physical activity has been extensively associated with epigenetic modifications. However, the potential contribution of DNA methylation patterns to sports injury susceptibility remains largely unexplored, particularly among high-performance athletes. Since methylation regulates genes involved in inflammation, tissue repair, and musculoskeletal function, altered methylation profiles may influence injury risk. Moreover, epigenetic clocks are increasingly used to assess vulnerability to clinical phenotypes, as accelerated epigenetic aging has been linked to various diseases. Here, we studied the DNA methylome of peripheral blood cells in 74 elite female and male soccer players with extensive non-contact injury follow-up. We aimed to explore alterations associated with increased injury risk and to describe the dynamics of epigenetic age acceleration in this group. Although DNA methylomes between players with higher and lower injury risk were overall similar, we identified 1081 differentially methylated CpGs sites that partly affected genes involved in skeletal muscle functions. We also estimated epigenetic age using eight clocks but found no association with injuries. However, male athletes displayed higher epigenetic age acceleration than females. Comparing the methylome of age-accelerated versus decelerated individuals revealed widespread changes across five clocks, strongly biased towards hypomethylation in age-accelerated players. Differential CpGs targeted genes enriched in extracellular matrix, cytoskeletal and collagen-related functions. Overall, this study suggests a link between DNA methylation and non-contact injuries in elite soccer players and shows that epigenetic age acceleration, although unrelated to injuries, is associated with widespread hypomethylation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical exercise is a common prescription for promoting good health, as it is a primary preventive measure for a wide range of diseases1. Nonetheless, the specific parameters related to the optimal intensity and quantity of physical activity are yet to be fully characterized2. For instance, high-performance exercise may have distinct or even deleterious effects on the organism, such as in terms of cardiac function3, and an extensive exercise load significantly increases the risk of injury, including through inadequate recovery from substantial exertion or overtraining4,5,6,7. In professional sports such as soccer, where teams experience dozens of muscle injuries each season8, the incidence and burden of injuries have not decreased over the past 20 years despite preventive measures9. This issue poses significant challenges both for sports performance and financial outcomes10,11. Thus, biomarkers able to predict the biological impacts of intense exercise might be useful for the effective design of health-promoting interventions and could also help guide the implementation of injury prevention measures in elite sports organizations.

In this context, the biological age of an individual, understood as a general measure of physiological functioning taking into account chronological age12, can be used as a parameter for monitoring overall health status. An increased biological age would involve a deteriorated cellular, molecular and organismal state, which seems to be associated with a wide range of health issues. In this scenario, epigenetic clocks have been recently developed as tools to estimate biological age. These clocks rely on DNA methylation (DNAm) data to build mathematical models that are able to predict an “epigenetic” age, which is indicative of the overall health status13. Moreover, deviations between epigenetic and chronological age, known as “age acceleration or deceleration”, have been linked to diverse environmental, biological and social factors, such as physical activity14. In fact, it is well known that exercise can directly impact the DNA methylome in a dose- and tissue-dependent manner15,16. Although exercise has been related to biological age deceleration17, the type and intensity of the physical activity may play an important role on the final DNAm outcome15,18. For instance, epigenetic age measured in a limited number of CpG sites has already been demonstrated to be accelerated in elite athletes19. Therefore, the question remains how prolonged high-intensity exercise specifically affects the genome-wide DNAm landscape and epigenetic age, and what implications these associations may have for health, including potential links between DNA methylation patterns and injury susceptibility. Understanding this could aid in monitoring both high-level performance outcomes and injury-related issues.

In this study we have analyzed the whole-genome DNAm patterns and epigenetic age parameters of a cohort of elite male and female soccer players using peripheral blood samples. We detected a signature that differentiates players with higher injury risk from those with lower risk. Additionally, although epigenetic age seemed to be unrelated to injuries, we could detect extensive differences in age-accelerated versus age-decelerated players, which were related to muscle and extracellular matrix pathways.

Methods

Participants

Peripheral blood samples from both female (n = 37, median age: 23.2, range: 14.6–35.6) and male (n = 37 median age: 24.0, range: 15.9–32.6) top-performance soccer players were gathered over three seasons (2019–2020, 2020–21 and 2021–22). All athletes belong to Futbol Club Barcelona soccer teams playing the first divisions of the Spanish National Leagues (women in the Primera División Femenina de España or Liga F, and men in the LaLiga EASports). Samples were processed to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), cryopreserved and stored at the Biobank of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona—Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (HCB-IDIBAPS). To ensure consistency, samples were collected in pre-season (July) for all players, with the exception of 8 samples (3 male and 5 female) collected in September due to scheduling and availability constraints. BMI of players was within normal ranges across seasons (average = 22.2, SD = 1.8), and participants did not report alcohol or tobacco consumption.

Muscle, tendon and ligament injuries recording

This study followed consensus guidelines on the definitions and data collection procedures for football injury studies described by UEFA20. Injuries had to occur during training or match. We used only injuries that caused absence from at least the following training session or match. They were classified as time-loss (TL) injuries. We recorded the history of muscle, tendon and ligament injuries of all players over the seasons in our Club using a validated electronic medical record system (COR version 1.0; FCB, Spain). Injury diagnoses were made by the relevant medical physicians (FCBarcelona team doctors) of each team during the evaluation period, following criteria included in the FC Barcelona 2018 Muscle Injury Guide21. Injuries were classified using the OSICS_10 coding system (Orchard Sports Injury Classification System)22, muscle injuries were indicated by the code OSICS -M–; tendon injuries by code OSICS-T– and ligament injuries by code OSICS -J–. To calculate injury severity (return to play) we have based on a UEFA proposal20 and it was determined according to the number of days from injury occurrence until the player play again at least 60 min per match, ranging from mild (1–7 days), to moderate (8–28 days), and severe (> 28 days). In addition, specific injury variables were summarized into an “Injury score”, calculated as Injuries per season * Days out per season. A second score, “Injury score plus relapse” was computed as Injury score * Relapses per injury. These composite scores provide a single metric that captures both the frequency and severity of injuries, and may allow for a more comprehensive assessment of overall injury burden and facilitating comparisons between players.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional board approval for the study was obtained from local research ethics committee on Science and Ethics of the Barça Innovation Hub (Football Club Barcelona n˚ 2021FCB29), and the Ethics Commission of the Consell Català de l’Esport (Code 012/CEICEGC/2021, Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain). All participants were informed of the risks and benefits of the study and gave written consent for this study. All personal information and results were anonymized.

DNA methylation arrays

From each PBMC sample stored at the Biobank of the HCB-IDIBAPS, DNA was extracted using DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, following manufacturer instructions). After Qbit measurements and DNA quality control, the Infinium Methylation EPIC BeadChip arrays v2 (by Illumina) were performed in order to measure DNA methylation of the samples. These methylation arrays were outsourced at Human Genotyping Platform (CeGen) at CNIO (Madrid, Spain), where all the steps of sample preparation, bisulfite modification and arrays runs were performed.

DNA methylation data processing

Raw data in the form of IDAT files were processed using a pipeline based on the R/Bioconductor package SeSAMe (v1.20.0)23. Briefly, the SeSAMe preprocessing code “QCDPB” was used to include quality and SNP masking (Q), channel inference (C) and dye bias correction (D), detection p-value masking (P) and noob background correction (B)24. Probes with NA masking in one or more samples were filtered out. EPICv2 replicated probes were averaged across replicates. Self-reported sex was validated using the DNA methylation data with the estimateSex function from the R/Bioconductor package wateRmelon (v2.8.0)25. The R/Bioconductor package IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICv2anno.20a1.hg38 (v1.0.0) was used for array annotation. Additionally, the following probes were filtered out: “ch” probes (non-CpG), “rs” probes (SNP), “cl/ct” probes (control), “nv” probes (EPICv2 nucleotide variants), sex-chromosome probes, “Flagged probes” and “Probes with mapping inaccuracies” as described in the Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 release notes, EPICv2 off-target probes described by Peters TJ et al.26, other multimapping and cross-reactive probes previously described27,28, probes with SNPs with MAF > = 0.01 at their CpG or SBE sites (dbSNP151), and probes not present in the IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICv2anno.20a1.hg38 annotation. Additionally, experiment-specific conflicting probes were identified and removed using the gaphunter method (threshold = 0.2, outCutoff = 0.03) from the R/Bioconductor package minfi (v1.48.0)29. After all the filtering steps, the final number of probes in the dataset was 774,288.

DNA methylation age computation

Epigenetic age was estimated for several DNA methylation clocks: 1) the R/Bioconductor package methylclock (v1.8.0)30 was used to compute the “Horvath” universal clock31, the “Hannum” blood clock32, the “PhenoAge” clock33, the “DNAmTL” telomere clock34 and the “Zhang EN” and “Zhang BLUP” clocks35; 2) the DNA Methylation Age Calculator tool (https://dnamage.clockfoundation.org/, accessed May 2024) was used to compute the “GrimAge”36 and “GrimAge2”37 clocks. Epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) was defined as the residuals of adjusting the epigenetic age values for chronological age in a linear model.

Differential DNA methylation analyses

Prior to statistical analyses, β-values were logit-transformed to M-values38. The R/Bioconductor package limma (v3.58.1)39 was used for the differential analyses. Linear models were built fitting M-values as dependent variables and different groups as independent variables. Models were adjusted for sex. Differentially methylated CpGs (DMCs) were defined as those with FDR or unadjusted p < 0.05 and a β-value difference > 5% between the compared groups. A 5% β-value threshold has been previously used for differential studies involving PBMCs40 and is above the minimal threshold previously recommended for epigenome-wide association studies41. To explore the robustness of the findings, statistical power analyses were carried out using the R package pwr (v1.3–0), based on two-sample t-tests with unequal group sizes. In the injury-cluster differential analysis (nominal significance and > 5% β-value difference), 87.5% of CpGs showed statistical power exceeding 80%. In the clock epigenetic age acceleration analysis (FDR < 0.05 and > 5% β-value difference), between 59 and 67% of sites had power above 80% across the different clock comparisons.

Pathway enrichment analyses

The R/Bioconductor package missMethyl (v1.36.0) was used for pathway enrichment analyses42. A selection of MsigDB databases was used, including Gene Ontology and Canonical Pathways gene sets43,44. The gsameth function was employed to estimate enrichments taking into account differences in the number of probes mapping to each gene and the EPICv1 annotation was used via the R/Bioconductor package IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b4.hg19 (v0.6.0), so input CpGs were filtered for those present in the EPICv1 arrays.

Results

Differential DNA methylation analysis in soccer players with high versus low injury risk

We analyzed the methylation status of 774,288 CpG sites in the peripheral blood of 74 male and female elite soccer players with extensive characterization of injury parameters (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1A, Methods). We initially explored possible associations between injury parameters and DNAm profiles. As a first step, we aimed at identifying athletes with higher propensity for injury frequency and severity. Although injury susceptibility is important in elite sports, there is no clear consensus criterion for defining “injury-prone” players. Thus, we decided to employ an agnostic clustering method to avoid relying on arbitrary thresholds across different injury parameters. To do so, we used the normalized injury variables and scores (Supplementary Table 1) to perform hierarchical clustering. This analysis revealed two clear groups of athletes with different patterns of non-contact injuries (Fig. 1B). Most athletes belonged to cluster 1 (N = 63, 32 females, 31 males), which is associated with reduced injury frequency and duration. In contrast, cluster 2 (N = 11, 5 females, 6 males) identified players with significantly higher scores across various injury parameters (Wilcoxon adj. p < 0.01) and therefore represent a group of individuals with higher frequency and duration of injuries (Fig. 1C). Next, we performed a differential methylation analysis (DMA) to directly compare mean DNAm levels between the two groups across all of the CpG sites measured by the array. Although we did not detect strong differences between the two clusters, using a conservative approach we were able to identify a signature of 1081 differentially methylated CpGs (DMCs) in cluster 2 as compared to cluster 1 (p < 0.05, methylation difference > 5%, 424 hypermethylated and 627 hypomethylated, Supplementary Table 2) (Fig. 1D). These CpG sites mapped to a total of 272 genes. Although these genes did not seem to be significantly enriched in any particular biological pathway, we detected some interesting candidates. These include genes such as MYOM2 and VAMP545,46 related to skeletal muscle development and function, and RYR1, NPPA or CACNB247,48,49 involved in muscle contraction (Fig. 1E). In some of these genes, such as VAMP5 or NPPA, there were more than one differential CpG between C1 and C2 clusters (Fig. 1E). This finding provides further assurance on the significance of the results and suggests that differential methylation associated to injuries may not only target specific CpGs but also larger genomic regions spanning various CpGs.

Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of soccer players and injury profiling of the cohort. (A) Schematic of the study design. (B) Dendrogram showing the clustering of subjects into injury-low (cluster 1) and injury-high (cluster 2) groups. (C) Heatmap indicating the scaled value for the different injury variables used for the clustering. On the left, the adjusted p-values for Wilcoxon tests comparing cluster 1 to cluster 2 are shown. (D) Heatmap indicating scaled methylation values of 1,081 CpGs differential between C1 and C2 groups. (E) Boxplots of selected differential CpGs within genes associated with muscle development and function.

Epigenetic age acceleration is more prevalent in male players and is associated with a differential DNA methylation signature

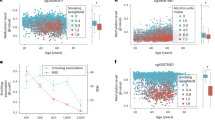

In addition to epigenetic signatures, we also exploited DNAm information to estimate epigenetic age with a selection of 8 widely-used epigenetic clocks, including chronological age clocks (Horvath, Hannum, Zhang BLUP and Zhang EN), phenotypic clocks (PhenoAge, GrimAge, GrimAge2), and a telomere length estimator (DNAmTL) (see Methods section for further details). In general, the epigenetic age estimations were highly correlated with chronological age, while the DNAmTL clock showed an expected inverse correlation (Fig. 2A). All of the estimations were highly associated with chronological age (all F-test adj. p < 0.001, Fig. 2B, Supplementary Figure S1), but there was remaining unexplained variability (R^2 coefficients ranging from 0.38 to 0.88), suggesting that individuals showed deviations from the predicted epigenetic ages. Thus, we computed epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) as the residuals of a linear model fitting epigenetic age against chronological age. The calculated EAA showed variable levels of correlation between the clocks, with the GrimAge and GrimAge2 estimators being the most similar (Supplementary Figure S2). Then, we speculated that athletes in cluster 2 may have a higher EAA than those with less injury risk. However, the EAA across epigenetic clocks was comparable between the two clusters (Fig. 2C, all Wilcoxon adj. p > 0.05).

Epigenetic clocks in male and female soccer players. (A) Heatmap displaying the correlation levels (Pearson coefficients) between chronological age and epigenetic age estimations. (B) Scatter plots showing the relationship between epigenetic age and chronological age for the Horvath and DNAmTL clocks. (C) Box plots describing the values of EAA for the Horvath, Hannum, PhenoAge, Zhang2019 BLUP, Zhang2019 EN, GrimAge, GrimAge2 and DNAmTL clocks, segregated by cluster 1 and cluster 2. (D) Box plots indicating the values of EAA for the Horvath and DNAmTL clocks, segregated by female and male athletes.

Although the level and intensity of injuries did not seem to be associated with EAA, we observed heterogeneity in the levels of EAA. Remarkably, part of this heterogeneity was caused by significant EAA differences between male and female athletes across most of the clocks, with male soccer players consistently showing higher EAA than female players (Wilcoxon test, adj. p ranging from 0.043 to < 0.001, Fig. 2D, Supplementary Figure S3). These findings are consistent with observations made in other non-athlete populations, whereby males are systematically older regarding biological age estimations50,51,52,53.

We further explored whether differences in EAA may reflect particular biological features of the athletes. Therefore, we decided to group athletes based on their EAA in order to compare subjects with positive EAA to those with negative EAA levels, i.e., athletes displaying higher-than-expected versus lower-than-expected epigenetic ages, respectively. We performed a DMA and we detected widespread DNAm differences between the groups, adjusting for gender, across most epigenetic clocks (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 3, FDR < 0.05 and > 5% methylation difference), i.e. Hannum (N = 17,715 CpGs), PhenoAge (N = 20,103 CpGs), Zhang EN (N = 38,393 CpGs), GrimAge (N = 705 CpGs), GrimAge2 (N = 16,486 CpGs) and DNAmTL (N = 24,870 CpGs). Interestingly, we observed a strong bias towards hypomethylated CpGs in the positive EAA group (i.e. higher epigenetic age than chronological age) (Fig. 3A). The analysis of the epigenetic clock estimating telomere length (DNAmTL) predominantly showed hypermethylation in individuals with higher estimated telomer length, which is the expected reverse pattern. These results indicate that elite athletes with age acceleration (or lower telomere length) display general loss of DNAm in peripheral blood. To expand on the biological characterization of the alterations found, we mapped the DMCs to genes and performed pathway enrichment analyses. We detected significant (FDR < 0.05) enrichments against Gene Ontology pathways across most of the clocks, with several pathways being shared between various clocks (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table 4). Remarkably, many of the shared gene sets were associated with cellular adhesion and cytoskeletal components (Fig. 3C). To explore this further, we also performed enrichments against the MSigDB Canonical Pathways database, which contains pathways describing extracellular matrix (ECM) functions. Notably, we observed strong enrichments for ECM-associated pathways across various clocks (Fig. 3D,E, Supplementary Table 4). These gene sets contain multiple collagen, protease and integrin genes, suggesting that these gene families are particularly enriched in EAA-associated DNAm alterations. Indeed, numerous collagen genes displayed several DMCs across various clocks, such as COL23A1 (Fig. 3F), which particularly reflected a global loss of DNAm in epigenetically aged athletes.

DNA methylation alterations and biological associations in epigenetically-accelerated elite soccer players. (A) Bar plots showing the number of DMCs (FDR < 0.05, methylation difference > 5%) between positive-EAA and negative-EAA athletes. (B) Upset plot indicating the numbers and intersections of significant (FDR < 0.05) Gene Ontology pathways found enriched for the DMCs. (C) Bubble plot displaying the Gene Ontology pathways found enriched in comparisons involving 3 or more clocks. (D) Upset plot showing the numbers and intersections of significant (FDR < 0.05) Canonical Pathways gene sets found enriched for the DMCs. (E) Bubble plot indicating the Canonical Pathways gene sets found enriched in comparisons involving 2 or more clocks. (F) Genome profile plots showing the methylation difference levels between positive-EAA and negative-EAA athletes defined by the PhenoAge (left) and Zhang2019 EN (right) clocks for all of the CpG sites associated with the COL23A1 gene. Statistically significant changes (FDR < 0.05, methylation difference > 5%) are marked in red.

Finally, we investigated whether additional covariates within our study cohort could confound or influence the analytical results, including sample collection date, playing position, and inferred regional ancestry (see Supplementary Table 1). We found no significant association between these variables and the previously defined injury clusters (all chi-squared adj. p > 0.05). Similarly, none of the specific injury-related variables differed significantly across any category of these groups (all sex-adjusted linear model adj. p val > 0.05).

In the case of the EAA analyses, collection date was significantly associated with EAA for the PhenoAge and Zhang BLUP clocks (sex-adjusted linear model adj. p val < 0.05). Consequently, we repeated all EAA analyses while adjusting for collection date, obtaining highly similar results in terms of the number and direction of changes (Supplementary Figure S4A-B) as well as in the enrichment of pathways related to cell adhesion, cytoskeletal organization, and extracellular matrix functions (Supplementary Figure S4C-F).

Discussion

Physical activity has been linked to good health and even to reduced biological aging14,17, but there is scarce data regarding the impact of sustained high-intensity, elite-level sports practice on the epigenome and the biological age, with some studies even suggesting potential detrimental effects19. In the present study, we have characterized the genome-wide DNAm levels of the peripheral blood of 74 elite soccer players with a tracked record of injury parameters. We aimed to identify DNA methylation alterations associated with increased injury risk and to characterize epigenetic age acceleration within this cohort. Overall, our findings revealed a distinct DNA methylation signature that differentiated players with elevated injury risk. Although epigenetic age acceleration was not linked to injury susceptibility, it exhibited pronounced sex-specific differences and was associated with widespread hypomethylation in individuals with accelerated epigenetic aging.

Although the DNA methylome of players with higher and lower frequency of injuries was overall similar, a conservative approach revealed a consistent signature of 1,081 DMCs. The DMCs targeted some genes involved in muscle activity, which is intriguing considering that we are analyzing blood samples. Indeed, not having been able to study the DNA methylome of muscle biopsies is one limitation of our study. This is not precluding the importance of DNA methylation changes triggered in situ by injuries, as has been shown in some previous studies on mice models54,55. Even though the cause and potential biological impact of the differential methylation in peripheral blood samples remains uncertain, the DNA methylation levels of individual genes or the overall signature could potentially serve as the basis to develop epigenetic biomarkers as predictors of injury predisposition. However, additional studies in larger series of soccer players, and eventually of elite players or other sports, should be undertaken to assess the reproducibility of our findings. In particular, the limited sample size in our study impeded the training and validation of predictive models of injury risk, which, if feasible, would provide valuable clinical insights.

Although our initial hypothesis was that players more susceptible to injuries may show an increased epigenetic age acceleration, which may account for their higher incidence of injury and capacity to recover, we could not find any significant association. Instead, we observed that male athletes displayed higher levels of EAA than females, a finding consistent with results from other studies not related to exercise50,51,52,53. These differences have sometimes been linked to lifestyle factors, such as smoking prevalence in men56, however, our cohort of elite soccer players maintains overall healthy and controlled lifestyle habits regardless of sex. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that sex-related differences in the professionalization of soccer players may in part account for the exacerbated EAA in male players57. Since earlier age, men undergo a higher training and competition load than women, which may lead to sex-related molecular differences, as previously described at the metabolic level58. In our cohort, however, there were no significant differences between male and female players regarding the years spent at the club (see Supplementary Table 1). Nonetheless, we acknowledge that our study does not capture lifetime training exposure, which limits further exploration of potential associations with epigenetic age. More broadly, the lack of exposure records represents a major limitation of our study. Exposure to football activity is a critical determinant of injury risk, as even players with high susceptibility will not sustain injuries without sufficient exposure.

To gain insights regarding possible epigenetic alterations in the blood of age-accelerated players, we performed differential analyses and observed widespread DNAm changes, remarkably biased towards DNAm loss. Interestingly, DNAm loss is also known to occur with post-adulthood aging in blood59, and therefore our observations suggest that biologically-aged athletes may display epigenetic alterations similar to those acquired with physiological aging. Remarkably, when we examined the genes affected by the EAA-associated DNAm alterations, these were enriched in extracellular matrix, cytoskeletal and collagen-related functions. It is interesting that we were able to detect muscle-related pathways in a different tissue, although the systemic nature of blood makes it a communication nexus for the entire organism. Indeed, it has been reported in many contexts that physical exercise induces DNAm alterations in peripheral blood60. However, the extent to which these changes have functional significance or are merely secondary effects of the stimulation remains to be explored, particularly because the relationship between DNAm and gene expression regulation is complex and context-dependent61,62. However, we could speculate different scenarios which are not mutually exclusive: some DNAm alterations may reflect genetic polymorphisms (meQTLs) related to muscle-related genes manifested across multiple tissues. In addition, circulating signals from muscle, such as extracellular vesicles or cell-free DNA, could shape immune cell epigenetics. Finally, because immune cells contribute to muscle repair, inflammation, and matrix remodeling, shared epigenetic changes may naturally arise in both blood and muscle. Further studies not only in peripheral blood but most importantly in muscle samples might be needed to fully explore the possible functional impact of our results.

In this study, we identified DNAm alterations associated with both injury risk and epigenetic age acceleration. A mediation analysis could in principle clarify whether DNAm mediates a relationship between these variables. In our dataset, however, EAA was not associated with injury risk, and the overlap between injury-DMCs and EAA-DMCs was minimal. This prevents meaningful mediation analysis, particularly in light of limited sample size. In fact, our observations suggest that EAA and injury risk may reflect distinct biological processes in elite athletes, shaping DNAm through independent mechanisms.

Taken together, our study reveals a link between injuries and DNA methylation patterns, which may serve to predict the injury susceptibility in elite soccer players. In this context, we envision that an integrative approach including epigenetics, germline genetics, metabolomics and external load parameters measured by Global-Positioning-System (GPS)63 may serve as the basis to develop accurate omics-based predictors of injury vulnerability. Furthermore, we observed that a set of players enriched in men are epigenetic-accelerated and related to a global hypomethylation. Whether this phenomenon remains once the professional life of the players is finished, and whether it is associated with the negative effects of age-acceleration observed in the general population remains to be determined in future studies.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

Pedersen, B. K. & Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports 25, 1–72 (2015).

Warburton, D. E. R. & Bredin, S. S. D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 32, 541–556 (2017).

Parry-Williams, G. & Sharma, S. The effects of endurance exercise on the heart: panacea or poison?. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 402–412 (2020).

Kenttä, G. & Hassmén, P. Overtraining and recovery A conceptual model. Sports Med. 26, 1–16 (1998).

Meeusen, R. et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45, 186–205 (2013).

Gabbett, T. J., Whyte, D. G., Hartwig, T. B., Wescombe, H. & Naughton, G. A. The relationship between workloads, physical performance, injury and illness in adolescent male football players. Sports Med 44, 989–1003 (2014).

von Rosen, P., Frohm, A., Kottorp, A., Fridén, C. & Heijne, A. Multiple factors explain injury risk in adolescent elite athletes: Applying a biopsychosocial perspective. Scand J. Med. Sci. Sports 27, 2059–2069 (2017).

Ekstrand, J., Hägglund, M. & Waldén, M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am. J. Sports Med. 39, 1226–1232 (2011).

Ekstrand, J. et al. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: The UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br J. Sports Med. 57, 292–298 (2022).

Nieto Torrejón, L., Martínez-Serrano, A., Villalón, J. M. & Alcaraz, P. E. Economic impact of muscle injury rate and hamstring strain injuries in professional football clubs. Evidence from LaLiga. PLoS One 19, e0301498 (2024).

Dallmeyer, S., Steinfeldt, H., Hübers, T., Pietzonka, M. & Breuer, C. Monetising misfortune: The financial consequences of injuries in professional football teams. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 11, e002437 (2025).

Rutledge, J., Oh, H. & Wyss-Coray, T. Measuring biological age using omics data. Nat Rev Genet 23, 715–727 (2022).

Horvath, S. & Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet 19, 371–384 (2018).

Oblak, L., van der Zaag, J., Higgins-Chen, A. T., Levine, M. E. & Boks, M. P. A systematic review of biological, social and environmental factors associated with epigenetic clock acceleration. Ageing Res Rev 69, 101348 (2021).

Voisin, S., Eynon, N., Yan, X. & Bishop, D. J. Exercise training and DNA methylation in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 213, 39–59 (2015).

Światowy, W. J. et al. Physical activity and DNA methylation in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12989 (2021).

Fitzgerald, K. N. et al. Potential reversal of epigenetic age using a diet and lifestyle intervention: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Aging (Albany NY) 13, 9419–9432 (2021).

Jacques, M. et al. Epigenetic changes in healthy human skeletal muscle following exercise- a systematic review. Epigenetics 14, 633–648 (2019).

Spólnicka, M. et al. Modified aging of elite athletes revealed by analysis of epigenetic age markers. Aging (Albany NY) 10, 241–252 (2018).

Fuller, C. W. et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J. Sports Med. 40, 193–201 (2006).

Barça Innovation Hub. Muscle Injury Guide: Prevention of and Return to Play from Muscle Injuries. (FCB Marketing Department, Barcelona, Spain, 2018).

Rae, K. & Orchard, J. The orchard sports injury classification system (OSICS) version 10. Clin. J. Sport Med. 17, 201–204 (2007).

Zhou, W., Triche, T. J., Laird, P. W. & Shen, H. SeSAMe: reducing artifactual detection of DNA methylation by Infinium BeadChips in genomic deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e123 (2018).

Triche, T. J., Weisenberger, D. J., Van Den Berg, D., Laird, P. W. & Siegmund, K. D. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e90 (2013).

Pidsley, R. et al. A data-driven approach to preprocessing Illumina 450K methylation array data. BMC Genomics 14, 293 (2013).

Peters, T. J. et al. Characterisation and reproducibility of the HumanMethylationEPIC v2.0 BeadChip for DNA methylation profiling. BMC Genomics 25, 251 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209 (2013).

Pidsley, R. et al. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol 17, 208 (2016).

Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 30, 1363–1369 (2014).

Pelegí-Sisó, D., de Prado, P., Ronkainen, J., Bustamante, M. & González, J. R. methylclock: A Bioconductor package to estimate DNA methylation age. Bioinformatics 37, 1759–1760 (2021).

Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 14, R115 (2013).

Hannum, G. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell 49, 359–367 (2013).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 10, 573–591 (2018).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation-based estimator of telomere length. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 5895–5923 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Improved precision of epigenetic clock estimates across tissues and its implication for biological ageing. Genome Med 11, 54 (2019).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 303–327 (2019).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge version 2. Aging (Albany NY) 14, 9484–9549 (2022).

Du, P. et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 587 (2010).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43, e47 (2015).

Steegenga, W. T. et al. Genome-wide age-related changes in DNA methylation and gene expression in human PBMCs. Age (Dordr) 36, 9648 (2014).

Campagna, M. P. et al. Epigenome-wide association studies: Current knowledge, strategies and recommendations. Clin. Epigenet. 13, 214 (2021).

Phipson, B., Maksimovic, J. & Oshlack, A. missMethyl: An R package for analyzing data from Illumina’s HumanMethylation450 platform. Bioinformatics 32, 286–288 (2016).

Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740 (2011).

Gene Ontology Consortium et al. The gene ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 224, iyad031 (2023).

Tajika, Y. et al. Vesicular transport system in myotubes: ultrastructural study and signposting with vesicle-associated membrane proteins. Histochem. Cell. Biol. 141, 441–454 (2014).

Lamber, E. P., Guicheney, P. & Pinotsis, N. The role of the M-band myomesin proteins in muscle integrity and cardiac disease. J. Biomed. Sci. 29, 18 (2022).

Houweling, A. C., van Borren, M. M., Moorman, A. F. M. & Christoffels, V. M. Expression and regulation of the atrial natriuretic factor encoding gene Nppa during development and disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 67, 583–593 (2005).

Soldatov, N. M. CACNB2: an emerging pharmacological target for hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmia and mental disorders. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 8, 32–42 (2015).

Witherspoon, J. W. & Meilleur, K. G. Review of RyR1 pathway and associated pathomechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 4, 121 (2016).

Tajuddin, S. M. et al. Novel age-associated DNA methylation changes and epigenetic age acceleration in middle-aged African Americans and whites. Clin. Epigenet. 11, 119 (2019).

Faul, J. D. et al. Epigenetic-based age acceleration in a representative sample of older Americans: Associations with aging-related morbidity and mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 120, e2215840120 (2023).

Phyo, A. Z. Z. et al. Sex differences in biological aging and the association with clinical measures in older adults. Geroscience 46, 1775–1788 (2024).

Yusipov, I., Kalyakulina, A., Trukhanov, A., Franceschi, C. & Ivanchenko, M. Map of epigenetic age acceleration: A worldwide analysis. Ageing Res Rev 100, 102418 (2024).

Iio, H. et al. DNA maintenance methylation enzyme Dnmt1 in satellite cells is essential for muscle regeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 534, 79–85 (2021).

Falick Michaeli, T. et al. Muscle injury causes long-term changes in stem-cell DNA methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 119, e2212306119 (2022).

Kankaanpää, A. et al. Do epigenetic clocks provide explanations for sex differences in life span? a cross-sectional twin study. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med Sci 77, 1898–1906 (2022).

Tjønndal, A., Skirbekk ,Sigbjørn Børreson, Røsten ,Stian & and Rogstad, E. T. ‘Women play football, not women’s football’: the potentials and paradoxes of professionalisation expressed at the UEFA women’s EURO 2022 Championship. European Journal for Sport and Society 21, 276–294 (2024).

Rodas, G. et al. A targeted metabolic analysis of football players and its association to player load: Comparison between women and men profiles. Front. Physiol. 13, 923608 (2022).

Jones, M. J., Goodman, S. J. & Kobor, M. S. DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell 14, 924–932 (2015).

Etayo-Urtasun, P., Sáez de Asteasu, M. L. & Izquierdo, M. Effects of exercise on DNA methylation: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med 54, 2059–2069 (2024).

Kulis, M., Queirós, A. C., Beekman, R. & Martín-Subero, J. I. Intragenic DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation, normal differentiation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 1161–1174 (2013).

Greenberg, M. V. C. & Bourchis, D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 590–607 (2019).

González, J. R. et al. Predicting injuries in elite female football players with global-positioning-system and multiomics data. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform 19, 661–669 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Illumina Inc. (in particular Rubén Melgarejo) for providing support with DNA methylation microarrays, which were outsourced to the Spanish Centro Nacional de Genotipado (CEGEN-ISCIII). Additionally, the authors would like to thank Michela Bertero and Elias Campo for institutional support, and the technicians of the IDIBAPS’s biobank for their technical assistance.

Funding

No specific funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Rodas and J.I. Martin-Subero designed and supervised the study; R.F. Pérez, J. Lecumberri-Arteta and M. Kulis extracted DNA and performed all the data analyses; T. Botta-Orfila and A. Rodriguez-Vilarrupla processed and stored samples; X. Yanguas, E. Ferrer and G. Rodas collected blood samples and injury parameters; R.F. Pérez, J. Lecumberri-Arteta, M. Kulis, G. Rodas and J.I. Martin-Subero wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez, R.F., Lecumberri-Arteta, J., Kulis, M. et al. Epigenetic signatures, age acceleration, and injury risk in elite female and male soccer players. Sci Rep 15, 41826 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25784-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25784-w