Abstract

Lymph node (LN) metastasis remains a critical determinant of cancer progression and prognosis, yet surgical interventions result in adverse effects. In this preclinical study, we investigated a minimally invasive therapeutic approach combining magnetic hyperthermia (MH) with a lymphatic drug delivery system (LDDS) using iron oxide nanoparticles (Resovist®). A custom-built MH device precisely regulated LN temperature at 45 °C. Using a mouse model (MXH10/Mo/lpr) of tumor-suspicious LN (ts-LN) metastasis, Resovist® was intranodally administered, followed by MH treatment. This combination significantly suppressed tumor growth in ts-LN and reduced lung metastasis, with enhanced M1 macrophage polarization and antitumor immune responses. Histopathology confirmed tumor necrosis and localized nanoparticle deposition, while qPCR of spleen tissue indicated differential immune modulation. No overt systemic toxicity was observed. The results demonstrated that this theranostic approach allows for real-time thermal control and effective regional tumor inhibition. The technique holds promise for early-stage cancer patients, offering a non-invasive, image-guided alternative to surgical LN resection with the potential for clinical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lymph node (LN) metastasis is a crucial prognostic factor for cancer patients and influences treatment management based on the TNM classification and survival outcomes1. Accordingly, LN metastasis is documented across various cancer types and signifies the status of the primary tumor as well as the dissemination of tumor cells to distant organs. Sentinel LN biopsy serves as a primary diagnostic tool to identify tumor dissemination, which directly impacts treatment management to enhance patient survival and slow the progression of cancer. Although surgical excision of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) alongside the primary tumor often results in adverse events (AEs) such as lymphedema, pain and prolonged hospitalization, there is an urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies that can effectively address LN metastasis without necessitating LN removal2,3,4. A lymphatic drug delivery system (LDDS)5,6,7,8 has been developed to administer anticancer agents directly into metastatic lymph nodes (LNs), which inhibits tumor growth and prevents the spread of metastases to downstream LNs. LDDS shows high treatment efficacy with reduced AEs compared to systemic drug administration. A phase 1 clinical trial of LDDS for head and neck cancer is currently underway at Iwate Medical University Hospital in Japan.

In the present preclinical study, the aim was to evaluate the treatment effect of LDDS utilizing magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in conjunction with minimally invasive magnetic hyperthermia (MH)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 in a LN metastasis mouse model after LN removal. MH is a minimally invasive treatment method compared to conventional cancer therapies, as it exploits the increased thermal sensitivity of tumor cells relative to normal tissues. The use of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) along with alternating magnetic fields (AMF) provides a distinct advantage by enabling deep tissue access for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. This technology allows for the selective targeting of tumor cells while minimizing thermal damage to surrounding healthy tissues and surface regions. With precise temperature regulation, MH preserves LNs, which are critical components of the immune system. We hypothesize that moderate MH using a temperature-controllable system29,30 may effectively induce tumor cell degeneration and stimulate immune responses, representing a promising strategy for comprehensive cancer therapy.

In the present study, we developed a novel MH device and utilized it alongside a magnetic iron oxide nanoparticle-liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent (Resovist®) to prevent LN metastasis for the first time. We employed a swollen LN mouse model, MXH10/Mo/lpr mice (MXH10/Mo-lpr/lpr)2,3, with 10 mm diameter LNs to create a tumor-suspicious LN (ts-LN) mouse model. Briefly, the ts-LN mouse model was established by removing the tumor-inoculated LN from MXH10/Mo/lpr mice; this model is also referred to as the resection-induced metastatic lung model. Concentrated Resovist® was injected directly into the ts-LN using the LDDS, followed by MH treatment at a constant temperature for 5 min to inhibit tumor growth. It was found that MH treatment with MNP was effective in inhibiting tumor growth in the ts-LN, thereby preventing the formation of lung metastasis through the intranodal delivery of MNPs (LDDS) in combination with MH. Therefore, the controlled temperature technique, combined with LDDS, may have direct applications in clinical advancements, potentially offering timely non-invasive cancer therapy without harming healthy tissues.

Results

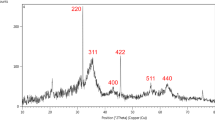

Heating characteristics of magnetic nanoparticles

To achieve effective treatment outcomes, the thermal characteristics of Resovist®, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles were comprehensively evaluated, with the device settings shown in Fig. 1a, b. As depicted in Fig. 1c, utilizing the fiber optic thermometer, the temperature increase in the tube containing Resovist® over time was monitored under varying magnetic fields ranging from 10.4 to 120 Amperes (A). A temperature rise of 20 °C was achieved after subjecting the Resovist® to a magnetic field strength of 20.5 kA/m for 60 s. To quantify the rate of temperature rise, the heating curve was analyzed at 10 different points between 10 and 19 s.

Heating characteristics of Resovist® in vitro. (a) An evaluation system for magnetic characteristics and heating power for Resovist® magnetic nanoparticles. (b) Experimental setup for evaluation of magnetic characteristics: Resovist® was located inside the coil and a fiber optic thermometer measured Resovist® temperature. (c) Time evaluation of temperature increment with different strengths of the applied magnetic field. (d) Heat generation power as a function of the magnetic field strength.

Interestingly, the rate of temperature rise was observed to be zero when the Resovist® was exposed to a magnetic field of 2 kA/m over a 60 s duration. We calculated the heat generation power (HP [W]) using the equation: \(\:P=mc\times\:\frac{{\Delta\:}T}{{\Delta\:}t}\), where \(\:m\) [kg] is the mass of the MNPs and \(\:c\) [J/(K∙kg)] was the specific heat capacity, \(\:{\Delta\:}T\) was the measured temperature rise and \(\:{\Delta\:}t\) the elapsed time, to investigate quantitatively the heating mechanisms further. The findings revealed that P increased proportionately to the magnetic field strength raised to 1.8, as illustrated in Fig. 1d, over the 3.5 to 7 kA/m range. For 12.5 kA/m, P demonstrated a direct proportionality to the magnetic field strength. Although the results exhibited a similar trend at lower field strengths, the differences may be attributed to the diminishing magnetic properties accompanying the temperature changes31,32,33. Conversely, at higher field strengths, the heating performance tended to plateau as the MNPs approached their magnetic saturation with increasing external magnetic field strength.

Development of the PID-controlled in vivo temperature regulation system

The PID-controlled temperature and MH system was developed for in vivo experiments, aided by wireless temperature monitoring and controlled heating power (Fig. 2a). Additionally, we examined the magnetic field distribution in the R-X plane 4-turn drive coil (Fig. 2b). To maximize the exposure to the strongest magnetic field, especially in the target region, mice were positioned next to the core of the 4-turn drive coil. By assuming a 10 mm2 area on the R axis (Z ± 5 mm, R = 0 ~ 5 mm), the magnetic field strength at the LN was calculated (Fig. 2c). The magnetic field strength was found to be 12 kA/m when the distance between the coil and LN was set to 10 mm. The magnetic field strength and frequency product remained well below the irradiation limit of 5 × 109 Am− 1s− 134,35. To assess the potential anticancer therapeutic effect of the MH system with controlled temperature and heating, we heated the subiliac LN (SiLN) and proper axillary LN (PALN) of MXH10/Mo/lpr mice to approximately 45 °C following the injection of Resovist® into SiLN (Fig. 2d, e). Temperature measurements were visually presented in two-dimensional color-coded images, where LNs appeared brighter (Fig. 2f, g). Utilizing this temperature measurement technique facilitated the tracking of temperature changes in the LNs over time.

Experimental setup for cancer treatment in tumor model animal experiments. Temperature monitoring and heat power control with a developed magnetic hyperthermia system. (a) Picture of an overview of the experimental setup and enlarged picture for drive coil and mouse. Demonstration of heating experiments on MNP phantom. (b) Two-dimensional magnetic fields Bz distribution around the target area, LN, with superposed mouse image. (c) Magnetic fields Bz were applied to the LN as a function of Z on the center axis of the coil. (d, e) time evaluation of temperature increment of LN and electric current and (f, g) thermography image around LNs during treatment. The red circle indicates an area of the LN.

Evaluation of the in vivo effect of Resovist® with MH

Before starting an in vivo experiment, we analyzed Resovist®’s cytotoxicity using both MTT and luciferase assays without the involvement of MH (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). It was observed that luciferase activity exhibited a volume-dependent decrease in wells containing Resovist®, with some wells containing 50 µL of Resovist® showing no visual detection of luciferase activity (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Specifically, the luciferase activity of cells decreased by a factor of 10 when impregnated with 20 µL of Resovist® and a factor of 100 when impregnated with 50 µL of Resovist® (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The MTT assay revealed that the cell survival fraction was reduced to 50% in wells impregnated with 20 µL of Resovist®. However, we did not observe any differences in the cytotoxicity events with varying volumes of Resovist® impregnation (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Further investigations involved the analysis of the interaction between Resovist® and luciferin, which was measured using a spectrophotometer transmission approach (Supplementary Fig. 1c). It was found that the transmission approach was directly related to the volume of Resovist® added to the cell solution. The findings suggested that Resovist® inhibited luciferase transmission without harming the cells. As a result, for this study, we assessed the luciferase activity changes in the untreated and hyperthermia groups, with the final treatment efficacy being evaluated by histopathological processing. To facilitate the application of Resovist® with MH, we measured the osmotic pressure and viscosity of Resovist® at different concentrations (Fig. 3a), and results of 1× to 4× concentrations were ranged at an osmotic pressure > 329 mOsm/kg, with viscosity < 6.3 mPa∙s. The parameters for Resovist® 2× (794 mOsm/kg, 2.0 mPa∙s) fell within the safety window of LDDS parameters (500 to 1,017 mOsm/kg, < 30 mPa∙s)7,8,36. By contrast, the osmotic pressure of blood is 285 mOsm/kg (Fig. 3b).

Animal study design. (a) Osmotic pressure and viscosity parameters of enriched Resovist®. (b) Safety window of LDDS. (c) Experiment schedule. Tumor cells were inoculated into the right-side subiliac lymph node (SiLN; ti-SiLN), and 3 days later, ti-SiLN was removed to create a metastatic lymph node mouse model. Resovist® was injected into ts-PALN via LDDS on day 3. Then, hyperthermia was conducted every day from day 3 to day 6 after inoculation. (d) Representative in vivo images with luciferase activity changes of the group’s 3 days after inoculation. (e) Thermal image during heating. (f) Iron levels of each organ. Untreated (n = 6), Resovist® (n = 5), hyperthermia (n = 6), and combination (n = 7). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

To create a tumor suspicious LN (ts-LN) mouse model, we used MXH10/Mo/lpr mice, as described in the Materials and Methods section (Fig. 3c). Briefly, the SiLN, which had been inoculated with tumor cells, was surgically removed 3 days after tumor inoculation to create the ts-PALN. Before the removal of the SiLN on day 3 after tumor inoculation, we confirmed visual and quantitative similarity of luciferase activity in the SiLNs and ts-PALNs of the experimental animals (Fig. 3d). No tumor growth was detected around the removed SiLN until the endpoint of the experiment. ts-PALN received a direct injection of 2× Resovist® and was subjected to MH with a 4-turn drive coil and a temperature-controlled system, immediately. During the treatment, the temperature increased to more than 40℃ in the combination group. In contrast, no temperature changes were observed in the hyperthermia group on days 3, 4, 5 and 6 (Fig. 3e). Luciferase activity in the axillar area (ts-PALN and lung) increased over time in the untreated and hyperthermia groups (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Interestingly, the ex vivo luciferase activity of ts-PALN was higher in the hyperthermia group than in the untreated group. In contrast, ex vivo luciferase activity of the lung remained consistent regardless of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1d), indicating that the efficacy of hyperthermia is regional, not systemic. In terms of visible side effects resulting from the intranodal injection of Resovist® into ts-PALN, we measured the volume of the ts-PALN, with the most significant increase observed in the hyperthermia group, followed by the untreated, Resovist® and combination groups (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Importantly, we did not observe any visible side effects of hyperthermia on the surface of the skin.

After the experiments, the mice were humanly killed and all organs were harvested. The iron level of Resovist® in each organ was measured (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Table 3). The highest amount of iron was recorded in the ts-PALN and the liver; levels of 1.65 ± 0.38 µg/mg and 1.59 ± 0.24 µg/mg, respectively in the ts-PALN, compared to 0.03 ± 0.01 µg/mg and 0.09 ± 0.04 µg/mg in the liver for Resovist® and combination groups. Notably, there were no differences in iron levels between the Resovist® and combination groups in the ts-PALN and lung. However, the iron level in the liver was three times higher in the combination groups than in the Resovist® group. We believe that Resovist® circulation increases due to the heightened blood flow induced by hyperthermia, leading to enhanced perfusion in vascular-rich organs. Figure 4a, b shows HE and Berlin Blue stained sections of the ts-PALN and lung of untreated, Resovist®, hyperthermia, and combination groups, respectively. Tumor cells were found in the marginal sinus of ts-PALN in the untreated, Resovist® and hyperthermia groups. In contrast, no tumor cells were found in the marginal sinus of the ts-PALN (Fig. 4a) and lung (Fig. 4b) of the combination group. By using Berlin Blue staining, we detected the distribution of Resovist® in the ts-PALN in the Resovist® and combination groups but not in the lung. Consequently, tumor response in the ts-PALN was 1 for the combination group. No tumor response was found in the untreated, Resovist® and hyperthermia groups (Fig. 4c). Moreover, tumor response in the lung was found to be 1 for the combination group, 0.6 for hyperthermia, 0.4 for Resovist® and no tumor response was found in the untreated group (Fig. 4c). The highest necrotizing score was found in the ts-PALN of the combination group compared to the other groups.

Figure 4d shows quantification of the iron deposit area (the percentage of the blue area in the sample) of histopathological images in each organ. The highest percentage of iron deposit area on the histopathological section was recorded in ts-PALN, with levels of 12 ± 3.8% and 11 ± 3.1% for the combination and Resovist® groups, respectively. Some accessory axillary LNs, lung, and skin specimens showed high levels for all groups. Notably, there were no differences in iron deposit levels for all groups in the ts-PALN.

Figure 5 shows the macrophage characterization of the treated groups’ ts-PALNs (Fig. 5a) and lung (Fig. 5b). Anti-CD206 positive cells were found in the ts-PALNs and metastasis of the lung in the Resovist® and hyperthermia groups. High expression of anti-CD206 positive cells was found in the ts-PALNs of the hyperthermia and untreated groups; the results indicated tumor progression and poor antitumor immune responses (Fig. 5a, c). A similar expression level of anti-CD206 (M2) and anti-CD80 (M1) was found in the Resovist® and combination groups, and the least expression was measured in the combination group. M1 macrophages numbers (CD80/CD206 normalized ratio) tended to be higher in the combination groups vs. the other groups (Fig. 5d). Subsequently, immune profiling of the central immune organ, the spleen, was conducted after subjecting mice to MH via qPCR. The findings revealed that an upregulation of Treg cells and inflammatory cytokines in the Resovist® groups, whether with or without tumors, which was attributable to the presence of super-paramagnetic iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (Fig. 6). We hypothesize that Resovist® attracted T cells, resulting in an increased secretion of IFNγ in the spleens of the Resovist®-injection groups that did not undergo MH. Notably, Resovist® induced the activation of M2 macrophages, leading to the upregulation of IL10. This upregulation resulted from an imbalanced immune response following M1, and the subsequent activation of M2, an effect which was not observed in the combination group. These macrophage polarizations subsequently influenced Treg cells by upregulating PDL1, while CD4 and CD8 impacted all immune modulators. Furthermore, Hsp90 and CRT were expressed at higher concentrations in the hyperthermia group compared to the combination group. Conversely, a downregulation of Hsp70 was observed in all treated groups.

Identification of the macrophage population. HE or anti-CD206 and anti-CD80 stained ts-PALN (a) and lung (b) of treated groups. Untreated (n = 6), Resovist® (n = 5), hyperthermia (n = 6) and combination (n = 7). Scale bar: 50 μm. T, tumor. (c) Expression of anti-CD206 and anti-CD80 cells (%). (d). CD80/CD206 normalized ratio.

Liver function and hematology tests were carried out to assess the potential side effects of combining Resovist® with MH (Table 1). ALT and AST concentrations were elevated in the Resovist® group. ALT concentrations are significantly higher in the hyperthermia group than in the other groups (P = 0.001). AST concentrations were notably higher in the hyperthermia group compared to the untreated and combination groups (P = 0.028). Moreover, the hyperthermia group exhibited significantly higher WBC counts than the untreated group (P = 0.010). The Resovist® group also has a higher WBC count than the untreated group (P = 0.018).

Discussion

The present study aims were to prevent metastasis formation in the ts-LNs and lung in the early stage of metastasis using a LN metastasis model mouse with iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (Resovist®, MRI contrast agent) with MH. First, we developed a PID-MH system in-situ (Figs. 1 and 2) then applied it in mouse experiments (Figs. 3 and 4). Our preclinical data indicated that tumor growth was inhibited in a mouse injected with Resovist® followed by MH, thereby suppressing distant metastasis in the lung. Using LDDS as a Resovist® injection route, revealed tumor formation in the ts-LNs. Previous studies have shown that applying a magnetic field magnetizes the iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles, but when the magnetic field is removed, the saturated magnetism is lost completely37. Moreover, we could explain the relationship between Resovist® volume and luciferase activity (Supplementary Fig. 1c). For in vivo experiments, a tumor-suspicious LN model mouse was created and the results showed that hyperthermia effectively increased the temperature in the target region. Thus, evaluation of treatment efficacy was based on luciferase activity (untreated and hyperthermia groups) and histopathological processing (all groups). Furthermore, iron level measurements in various organs demonstrated the circulation and distribution of Resovist®. The study found that the highest iron levels were recorded in the treated LNs and the liver, indicating enhanced perfusion due to hyperthermia (Fig. 3f). Histological assessments of the LNs and lungs indicated significant differences in tumor response between treatment groups, with the combination group showing the highest necrotizing score (Fig. 4c). An M1 pro-inflammatory response found in the combination group (Fig. 5), which can activate cytotoxic T cells38,39. However, in these experiments, pro-inflammatory cytokines could not be measured in real-time, because of a Resovist®-induced immune storm, to identify their contribution to tumor suppression (Fig. 6). The interaction between Resovist® and immune cells was elucidated, with the study proposing that Resovist® attracted T cells and subsequently increased IFNγ secretion in the spleen (Fig. 6). Additionally, Resovist® was found to activate M2 macrophages, leading to an upregulation of IL10. This phenomenon was attributed to an imbalanced immune response after the initial M1 activation, an effect which was not observed in the combination group.

The shifts in macrophage polarization were linked to Treg cells through the upregulation of PDL1, and the study noted the impact of CD4 and CD8 on various immune modulators38,39,40. In other words, Resovist® injection without any MH, activated M2 macrophages and promoted tumor formation41. The findings shown in Table 1 highlight substantial variations in liver enzyme levels (ALT and AST) and the WBC in the hyperthermia group when contrasted with the other groups. The increased liver enzyme levels may indicate potential stress on the liver, while the rise in the WBC count suggests a possible immune response. Further investigation and clinical interpretation are essential to ascertain the precise clinical implications of these observations in the study context. The present study has provided important insights into the heating behavior of Resovist® in MH, demonstrating its potential to prevent tumor formation in ts-LNs and the lungs in a ts-LN mouse model. Following AMF exposure to Resovist®-injected ts-LNs in the combination treatment group, upregulation of T cells was found, including Treg and Th1 cells, compared to the control group. Additionally, increased mRNA expression of IL6 and TNFα, along with elevated CD80 expression (IHC) and reduced levels of IL10 and Hsp70, suggest a shift toward M1 macrophage polarization in the combination group (Fig. 7). Therefore, IL10 and PDL1 (mRNA expression levels), along with CD206 (IHC) expression, and low IFNγ and hsp70 levels support the hypothesis that suppressed pro-inflammatory and M2 macrophages are linked to immunosuppression and tumor progression in the control and Resovist-only groups. The development of a PID-controlled in vivo temperature regulation system enhanced the precision of MH and the evaluation of treatment efficacy and immune responses; potential side effects further contributed to the understanding of this innovative cancer therapy.

The study design focused on the therapeutic outcomes of MH using iron oxide nanoparticles through a LDDS in a ts-LN mouse model. In this design, ts-LN was injected with iron oxide nanoparticles (Resovist) and exposed to an AMF using a PID-controlled MH device, keeping the ts-LN temperature at 45 °C. This resulted in localized heating, tumor suppression in ts-LN and reduced lung metastasis. A summary of mRNA expression in the combination therapy group (Resovist® + MH) and control group.

The present study clearly the feasibility of the MH system using a LN metastasis model mouse. We effectively controlled and maintained a constant temperature of 45 °C, with a minimal error of approximately ± 1 °C. While further studies with a larger sample size are necessary to rigorously evaluate the detailed treatment effects, including their impact on both normal and tumor cells, the preliminary results confirm the degradation/inhibition of tumor cells using this approach. To advance to the stage of clinical trials, it will be imperative to ensure the safety and efficacy of the medical device. Specifically, it will be crucial to perform cancer therapy while monitoring and maintaining a constant treatment temperature for MH treatment, as explained in the Introduction. This approach highlights the concept of simultaneous therapy (treatment) and diagnostics (monitoring), often referred to as “theranostics”42. Our developed device has successfully met these requirements in animal experiments, paving the way for future clinical trials without significant modifications. However, when considering clinical trials involving patients with head and neck cancer, assessing superficial LNs and profound LNs (around 10 mm deeper) will be challenging.

Additionally, there is no need to reduce the injection volume of Resovist® via LDDS administration; the same volume is used for better visibility in MRI observations. To deliver sufficient magnetic energy to deeper locations with a reduced magnetic fluid, we propose an improvement to the magnetic coil system (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and the evaluation of heating power H x f as a function of distance from the coil surface (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In the current configuration for the metastatic LN mouse model (LDDS-delivered 200 µL of Resovist®), superficial LNs and the H × f applied to the LN were 3–4 × 109 Am− 1s− 1. To reach deeper locations, around 15 mm under the administration of the 90 µL of Resovist®, one practical approach was to apply a pulsed magnetic field to enhance the efficiency of the energy conversion rate from magnetic to thermal energy via magnetic energy dissipation of MNPs43,44. The quick magnetic response that originated from the pulsed magnetic fields generates a larger delay of changing magnetic moment, resulting a larger thermal energy compared with the conventional magnetic response of sinusoidal magnetic fields. The pulsed magnetic field demonstrated a fourfold larger heating efficiency44, which enabled it to achieve a treatment at deeper locations.

Another approach is to expand the radius of the magnetic coil. While developing the radius reduces the field strength near the coil (e.g., at a distance of 0 mm), it increases the field strength at locations farther from the coil (e.g., at a distance of 15 mm). To compensate for the reduced field strength, the frequency of the applied magnetic fields can be increased to around 400 kHz, as heat generation involving the magnetic hysteresis loop is directly proportional to the frequency. This strategy will allow us to effectively treat tumor cells at a depth of 15 mm in future clinical trials, with only minor modifications to the existing system.

In conclusion, we have developed a PID-based temperature control system and a MH treatment system incorporating wireless temperature monitoring and heating power control. The inclusion of wireless temperature monitoring enables non-invasive hyperthermia treatment. We have elucidated the detailed heat generation mechanism of Resovist® for MH, revealing a non-linear relationship with magnetic field strength. The heat generation is proportional to the 1.8 power of the magnetic field strength in the case of magnetic fields from 3.5 to 7 kA/m. It is proportional to the magnetic field strength when approximated by a plot of 12.5 to 20 kA/m. The in vivo experiments using a metastatic lymph node mouse model were successful in controlling the treatment temperature at 45 °C, with a minimal error of approximately 1 °C over a 5-min treatment duration.

Moreover, we have confirmed tumor inhibition in the ts-PALN and lung. This non-invasive diagnosis and treatment approach for MH holds promise and paves the way for seamless progression to future clinical trials for cancer patients. We can treat cancer located at deeper sites, approximately 10 mm beneath the body surface, with minor modifications to the excitation magnetic field coil system. This approach allows observation of the abscopal effect, when localized treatment triggers a systemic antitumor response.

In terms of human safety, there is a need to consider the acceptable amount for the injection of MNPs. In general, Resovist® (MNPs), with an iron amount of 0.016 mL/kg, can be injected into the vein of a human and the iron concentration is approximately 28 mg/mL in the magnetic fluid solution. For a 60 kg human, the acceptable iron amount is approximately 27 mg. In our study, we injected concentrated Resovist® (double concentration of 58 mg/mL) of 0.12 mL into the LN of the mouse tumor model and the injected iron amount was 6.6 mg for one LN. This evaluation indicates that we can treat cancer in one LN by using one fourth of the limitation amount. From the clinical viewpoint, our treatment strategy is likely to be effective for cancer patients in the very early stage, such as N0 cancer patients. Furthermore, the injected MNPs remain in the LN after treatment for some time and would generate an image artifact on MRI, resulting in adverse effects on macrophage activities and cancer diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Magnetic nanoparticles (resovist®; magnetic fluid containing iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles)

Resovist® (Kyowa CritiCare Co., Ltd., Japan)45, magnetic fluids containing superparamagnetic iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (SPIONs) approved for a contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is employed in research to connect to future clinical trials smoothly. The hydrodynamic diameter is approximately 60 nm19 to access the lymph nodes and other tissues easily, and the original iron concentration of Resovist® is about 28 mg/mL, sufficient to magnetize and generate magnetic energy dissipation for magnetic heating.

Evaluation of heat generation of resovist®

The dependence of the heat generation characteristics of Resovist® were evaluated under an adiabatic environment with an induction heating power EasyHeat 2.4 kW (Ambrell, Rochester, New York, US) and a Fiber Optic Thermometer (FL-2000, Anritsu, Japan), (Figs. 1a, b). We measured the temperature rise of Resovist® from room temperature when exposed to AMFs of 2–20 kA/m (260 kHz) for 60 s. The optical thermometer recorded temperature data with a high accuracy of 0.1 °C. The heat generation characteristics of Resovist® are evaluated by the heat generation rate P obtained from the following Equation: \(\:P=mc\times\:\frac{{\Delta\:}T}{{\Delta\:}t}\), where \(\:m=2\times\:{10}^{-4}\) [kg] and \(\:c=4184\) [J/(K∙kg)], assuming the same amount of water. The temperature rise rate was calculated from 10 s to 19 s of the heating curve to eliminate the nonlinear temperature rise in the initial heating stage46,47.

MH with PID system for temperature control

We developed the PID control system for MH treatment experiments (Fig. 2a). The MNPs were heated by exposing an AMF with induction heating power and the 4 turns drive coil. The induction heating power device generates an electric current of 0–400 A with a frequency of 265 kHz. An infrared thermography recorded the two-dimensional temperature distribution in the treatment area at a temperature resolution of 0.04 °C. To generate adequate heat in the mouse, particularly in the target region, which was the LN, a 4-turn drive coil was positioned closer to and in front of the central axis of the target region. Temperature fluctuations within the target region were continuously monitored through the hollow core of the drive coil using a thermal camera. Our customized software then processed the temperature data, which was developed using the MATLAB SDK toolkit, facilitating non-invasive temperature monitoring. The temperature data from this monitoring program were conveyed to the LabVIEW PID system, which controlled the electric power supplied to the induction coil for heat generation. Based on the maximum temperature, the output current of the induction heating power was operated by PID-based control every s using LabVIEW 2020 (National Instruments, Austin, Texas, US). The PID system parameters were: Kp (proportional gain), 28.9; Ki (integral gain), 57.7; and Kd (differential gain), 3.46. We could follow the body’s motion and measure the temperature more accurately. The thermography was placed at a distance of 40 cm from the mouse. The thermal imaging camera had a resolution of 320 × 240 pixels and a field of view of 24°, which means that the spatial resolution was < 1 mm. For the hyperthermia treatment groups, intra-general mice were supine positioned on the experimental stage. The mouse stage was located 0.5 cm from the heat-induction-drive-coil and the maximum safety of surface heating was set to 45 °C. Mice were kept in an exact position for 5 min without any further movement every consecutive day from day 3 to day 6 after tumor-inoculation.

Protocol for preparation of 2× – 4× resovist®

The protocol for the 2-fold concentration of commercially available Resovist® is described next. The stock solution was vacuum-dried in the concentration method, and the target concentration adjusted by weighing the solution during drying (Supplementary Table 1). Precisely, a microtube containing 400 µL of stock Resovist® was placed in a vacuum dryer (KVO-300, AS ONE) and dried at 75 °C and 100 hPa. The microtube containing Resovist® was weighed hourly and measurements repeated until the mass of the solution was reduced by 200, 133 and 100 mg (each mass corresponded to 200, 133 and 100 µL of solvent) for 2×, 3× and 4×, respectively before and after concentration. Table 1 shows the actual concentration values.

Resovist® 2× – 4× physiochemical parameter measurements

The viscosity and osmolality were measured using an ultra-trace viscometer (RSM-MV1, SMILEco Instruments Co., Ltd., Sendai, Japan) and the osmolality was measured using an osmometer (Osmo Station OM-6060, Arkray, Tokyo, Japan).

Transmission spectra measurement of resovist® 1× vs. luciferase expression

KM-Luc/GFP and LM8-Luc (luciferase-expressing murine osteosarcoma) cells were cultured in the previously described medium; KM-Luc/GFP cells were used for the Luciferase and MTT assays, whereas LM8-Luc cells were utilized for spectrophotometer measurements. KM-Luc/GFP cells were seeded in 96 wells/plate at a 1 × 104 cells/mL concentration after triple passages (day 0) and then impregnated with 20 µL or 50 µL of Resovist® or fresh medium into each well (day 1). Luciferase and MTT assays were performed on day 3 as follows:

Luciferase-assay

3 days after seeding (2 days after impregnation), 1 µL of luciferin (150 µg/mL) was added into each well and the luciferase activity was measured within 2 min for 30 s.

MTT assay

3 days after seeding (2 days after impregnation), 10 µL of 3-[4,5-dimethylthia-zol-2-yl]−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide was added to each well, incubated for 1 h, and 100 µL DMSO pipetted to each well after discarding the cell suspensions from wells; then absorbance of control and impregnated cells were measured at a wavelength of 590 nm using a Rainbow plate reader (TECAN, Sunrise, Morgan Hill (CA), US).

Spectrophotometer measurements

Transmission spectra of KM-Luc/GFP cells in the mixture of luciferin and Resovist® in 1 mL PBS were measured using a JASCO V-770 NIR spectrophotometer (JASCO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), with spectra ranging from 200 to 1,000 nm. PBS was used as the blank.

Experimental mice

Twelve to thirteen week old age-matched male and female MXH10/Mo/lpr mice were used in all experiments (mice weight is shown in Supplementary Table 4). MXH10/Mo/lpr mice have swollen lymph nodes (10 mm diameter) that are the same size as humans. Mice were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle at room temperature with controlled humidity. All animals were housed in a barrier facility under pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Research Institute, Tohoku University, and only healthy mice were used for experiments. All mice were at least 12 weeks old before use and all experiments involving animals complied with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (2020BeA-020). All in vivo experiments were completed on mice anaesthetized by inhalation of 2.5% isoflurane in oxygen, and maximal care was taken to lessen animal suffering. Note that fur depilation was made every necessary day before in vivo experiment procedures commenced. Mice are under inhalation of 2.5% isoflurane in oxygen and humanely euthanized. Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board. Approval obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University Animal Studies: All investigations carried out using murine models, including the ARRIVE protocol, were compliant with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University. The MXH10/Mo/lpr mice used in this study are a recombinant strain originally generated and maintained in our laboratory. They are not available through commercial vendors but can be made available to other researchers upon reasonable request and under appropriate conditions.

Tumor cell preparation

Luciferase-green fluorescent protein-expressing mouse histiocytoma-like cells (KM-Luc/GFP)3,48 derived from MRL/lpr mice were cultured in a Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium (DMEM, Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% v/v of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Funakoshi), 0.5 mg/mL of geneticin (G418, Sigma Aldrich), and 1% v/v of L-glutamine-penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich), and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The KM-Luc/GFP cell lines (originally generated and preserved in our laboratory) and LM8-Luc cells (obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University, and also preserved in our laboratory) have been continuously maintained under controlled culture conditions. They were not obtained from external repositories or collaborators.

In vivo mouse model

Briefly, after shaving and depilation of fur of the right side of a mouse, a minimal incision was made regionally close to the SiLN, Mycoplasma negative (MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit) and KM-Luc/GFP cells (3.3 × 105 cells/mL) in PBS were suspended in Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products) (33.3% v/v). The syringe was maintained for 1 min to solidify Matrigel, and then the inoculation area was irrigated with 20 mL of lukewarm saline (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd). The day of tumor-inoculation was denoted as day 0. To create the ts-LN model, tumor-inoculated SiLN was surgically removed 3 days after tumor-inoculation to limit tumor cell migration to ts-PALN from the SiLN. Bleeding was minimized by hemostatic bipolar and the surgical area was irrigated with 20 mL of lukewarm saline after confirming the non-residual tumor cells.

In vivo Resovist® 2-times (2×) administration

Mice were randomly divided into 4 groups: untreated (n = 6), Resovist® (n = 5), hyperthermia (n = 5), and combination (Resovist® + hyperthermia) (n = 7). In the Resovist® injection groups, mice were given a single shot of 2 × (58 mg iron) Resovist® in 200 µL into ts-PALN on day 3 after tumor-inoculated SiLN removal (Fig. 3a). For distribution studies, the same volume and concentration of Resovist® was injected into the SiLN of healthy MXH10/Mo/lpr mice, and then all organs were collected and iron deposition was measured using an iron quantification device49.

In vivo tumor growth and treatment assessments

Tumor growth and treatment effects were evaluated by measuring the luciferase activity of tumor cells in the ts-PALN for 30 s with an in vivo imaging system (IVIS, PerkinElmer, Inc.) 10 min after luciferin (15 mg/mL) injection intraperitoneally using Living Image 4.7.3 software on days 3 (before treatment), 6 and 9 after tumor-inoculation, and data were normalized to that of day 3 luciferase activity. The ts-PALN volume was measured by a high-frequency ultrasound imaging system (VEVO770, FujiFilm Visual Sonics) using B-mode 2D images with RMV-704 probes (40 MHz, FOV: 15 × 15 mm) on days 0 (before inoculation), 3, 6 and 9 (before euthanasia); then 3D images were reconstructed. Data were normalized to day 0 data.

Ex vivo tumor growth and treatment assessments

Treatment effects were evaluated according to ex vivo luciferase activity expression of harvested ts-PALNs and vitals after blood collection from IVC on the last day of the study (9 days after tumor-inoculation). Ex vivo imaging was performed for 30 s immediately after in vivo imaging, and organs were immersed in luciferin (30 mg/mL) and then imaged.

Histo-pathological processing

ts-PALN and vitals were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin overnight, dehydrated twice, and embedded in paraffin (FFPE). FFPE tissues were sectioned at 3 μm thicknesses and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) and Berlin Blue. Histopathological evaluation was performed double blindly by two independent-experienced researchers. Representative images were taken at ×10 and ×20 on an Olympus BX-21 microscope.

HE staining

After dewaxing, rehydrating sections were immersed in hematoxylin (Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd); the bluing step was completed with 1% hydrochloric acid solution, set in DW for 5 min for coloring, and nucleic differentiation was completed by immersion into 1% eosin solution for 10 min. Sections were dehydrated, cleared and mounted in Permount medium.

Berlin blue staining

FFPE sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and washed in DW thrice (5 min/time), then immersed in Berlin Blue solution (mixture of equal amounts of 2% potassium ferrocyanide and 1% hydrochloric acid solution, immediately before use) for 30 min at RT. Then, sections were counterstained with Kernechtrot for 5 min after being washed in DW thrice (5 min/time), followed by dehydration, clearance and mounting.

Immunohistochemistry staining: FFPE sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, then antigen retrieved with an autoclave (0.01 M citric acid, pH 6.0) at 120 °C for 5 min. Slides were cooled to room temperature (RT), washed with PBS (3 times, 5 min). Primary antibodies, anti-CD206 (ab64693, 1:1,000) and anti-CD80 (ab64116, 1:1,000) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Slides incubated with anti-CD206 were blocked with 10% goat serum (Histofine, Nichirei, Japan) prior to primary antibody incubation. On the second day, slides were washed and secondary antibody (Max. Po(R), Histofine) was incubated at RT for 45 min. Color development was carried out using DAB (Histofine), then counterstained with Berlin Blue.

Berlin blue

Berlin blue and IHC stained whole slides were scanned using the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer SQ (Hamamatsu Group, Shizuoka, Japan) with high quality, and inadequate glass slides which produced scanning errors (out of focus or apparent missed tissue) were rescanned.

Evaluation of tumor and necrotizing responses

Tumor responses were evaluated based on the HE stained slides and scored as 0 for no treatment (presence of tumor) and 1 for treated (absence of tumor). For the necrotizing response, the scores were 0 for the absence of necrotic tissue, 1 for the presence of necrotic tissue in less than half of LN, 2 for the presence of necrotic tissue in more than half of LN and 3 for necrotic tissue replacement in the whole LN.

Quantification of the iron deposition area

Berlin Blue stained slides were used for the evaluation of the iron deposition area. The sample area and iron deposition area were extracted from the pathological image by using Python and GIMP. We quantitatively evaluated the blue area stained by Berlin blue with a threshold value that could identify blue color codes and others.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Following euthanization, each mouse spleen was harvested and immersed in RNAlater (Sigma Aldrich), homogenized, and then mRNA isolated using a FastGene Premium Kit (Nippon Genetics Co., Ltd) and cDNA synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using reverse transcriptase TaqMan probes with a qPCR ROX mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) uploaded into the AB7500 system (Applied Biosystems) using 7500 ver. 2.3 software to check the expression levels of immune profiling (Supplementary Table 2); primers were designed and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The thermal cycling was subjected to the reaction conditions, i.e., denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of annealing at 95 °C for 15 s, extension at 60 °C for 1 min in 96-well optical reaction plates. Then, data were analyzed using a comparative CT method using 7500 ver. 2.3 software, where the target genes relative to GAPDH (internal control) expression and data were normalized to untreated cells and compared to the primary reference targets.

Hematological and biochemical tests

Blood was collected on the last day of the experiment (9 days after tumor-inoculation; 6 days after treatment) from IVC under inhalation of 2% isoflurane in oxygen. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 13.2 g for 10 min at 4 °C while whole blood was prepared with the addition of EDTA (Sigma Aldrich). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the murine biochemical test was measured using the FujiFilm vet kit by FujiFilm Drichem 7000 V. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, a hematological test was performed using Horiba Microsemi LC-662.

Statistical analysis

All data were denoted in Microsoft Office 365 and the study outcomes were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc). Data are given as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and all graphical figures were generated by GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. Statistical significance was deemed to be a P-value ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

The corresponding authors’ data supporting the study findings are available upon reasonable request.

References

Ji, H. et al. Lymph node metastasis in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms, clinical significance and therapeutic interventions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01576-4 (2023).

Sukhbaatar, A. et al. Lymph node resection induces the activation of tumor cells in the lungs. Cancer Sci. 110, 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13898 (2019).

Sukhbaatar, A., Sakamoto, M., Mori, S. & Kodama, T. Analysis of tumor vascularization in a mouse model of metastatic lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52144-2 (2019).

Shao, L., Sukhbaatar, A., Sugiura, T. & Kodama, T. Positive Sentinel lymph node biopsy on promotion of metastasis: an unexpected effect? Med. Hypotheses. 198, 111624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2025.111624 (2025).

Kodama, T., Mori, S. & Nose, M. Tumor cell invasion from the marginal sinus into extranodal veins during early-stage lymph node metastasis can be a starting point for hematogenous metastasis. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 4, 56. https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-4722.2018.61 (2018).

Fujii, H., Horie, S., Takeda, K., Mori, S. & Kodama, T. Optimal range of injection rates for a lymphatic drug delivery system. J. Biophotonics. 11 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbio.201700401 (2018).

Sukhbaatar, A., Mori, S., Shiga, K. & Kodama, T. Intralymphatic injection of chemotherapy drugs modulated with glucose improves their anticancer effect. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 165, 115110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115110 (2023).

Sukhbaatar, A., Mori, S., Sugiura, T. & Kodama, T. Docetaxel administered through a novel lymphatic drug delivery system (LDDS) improved treatment outcomes for lymph node metastasis. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 171 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.116085 (2024).

Kok, H. P. et al. Heating technology for malignant tumors: a review. Int. J. Hyperth. 37, 711–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2020.1779357 (2020).

Chicheł, A., Skowronek, J., Kubaszewska, M. & Kanikowski, M. Hyperthermia - Description of a method and a review of clinical applications. Rep. Practical Oncol. Radiotherapy. 12, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1507-1367(10)60065-X (2007).

Shikano, A., Tonthat, L., Yabukami, S., Simple, A. & High-Accuracy, P. I. D. -Based Temperature Control System for Magnetic Hyperthermia Using Fiber Optic Thermometer, IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 16 807–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/tee.23361. (2021).

Deatsch, A. E. & Evans, B. A. Heating efficiency in magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 354, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2013.11.006 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Comprehensive Understanding of magnetic hyperthermia for improving antitumor therapeutic efficacy. Theranostics 10, 3793–3815. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.40805 (2020).

Abenojar, E. C., Wickramasinghe, S., Bas-Concepcion, J. & Samia, A. C. S. Structural effects on the magnetic hyperthermia properties of iron oxide nanoparticles. Progress Nat. Science: Mater. Int. 26, 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2016.09.004 (2016).

Carter, T. J. et al. Chester, potential of magnetic hyperthermia to stimulate localized immune activation. Small 17, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202005241 (2021).

Oei, A. L. et al. Enhancing the abscopal effect of radiation and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies with magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia in a model of metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Hyperth. 36, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2019.1685686 (2019).

Hurwitz, M. D. Hyperthermia and immunotherapy: clinical opportunities. Int. J. Hyperth. 36, 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2019.1653499 (2019).

Douek, M. et al. Sentinel node biopsy using a magnetic tracer versus standard technique: the SentiMAG multicentre trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 21, 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3379-6 (2014).

Sekino, M. et al. Handheld magnetic probe with permanent magnet and hall sensor for identifying Sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19480-1 (2018).

De Loosdrecht, M. M. V. et al. Laparoscopic probe for Sentinel lymph node harvesting using magnetic nanoparticles. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2021.3092437 (2022).

Kuwahata, A. et al. Combined use of fluorescence with a magnetic tracer and Dilution effect upon Sentinel node localization in a murine model. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 2427–2433. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S153163 (2018).

Taruno, K. et al. Multicenter clinical trial on Sentinel lymph node biopsy using superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and a novel handheld magnetic probe. J. Surg. Oncol. 120, 1391–1396. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25747 (2019).

Kuwahata, A. et al. Development of magnetic probe for Sentinel lymph node detection in laparoscopic navigation for gastric cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58530-5 (2020).

Kuwahata, A. et al. Magnetometer with nitrogen-vacancy center in a bulk diamond for detecting magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59064-6 (2020).

Kurita, T. et al. Magnetically guided localization using a guiding-marker system® and a handheld magnetic probe for nonpalpable breast lesions: A multicenter feasibility study in japan. Cancers (Basel). 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13122923 (2021).

Mihara, K. et al. Intraoperative laparoscopic detection of Sentinel lymph nodes with indocyanine green and superparamagnetic iron oxide in a swine gallbladder cancer model. PLoS One. 16, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248531 (2021).

Panagiotopoulos, N. et al. Magnetic particle imaging: current developments and future directions. Int. J. Nanomed. 10, 3097–3114. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S70488 (2015).

Mirzaei, N. et al. Sentinel lymph node localization and staging with a low-dose of superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) enhanced MRI and magnetometer in patients with cutaneous melanoma of the extremity - The MAGMEN feasibility study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 48, 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2021.12.467 (2022).

Kandala, S. K., Liapi, E., Whitcomb, L. L., Attaluri, A. & Ivkov, R. Temperature-controlled power modulation compensates for heterogeneous nanoparticle distributions: a computational optimization analysis for magnetic hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 36, 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2018.1538538 (2019).

Garanina, A. S. et al. Temperature-controlled magnetic nanoparticles hyperthermia inhibits primary tumor growth and metastases dissemination. Nanomedicine 25, 102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2020.102171 (2020).

Kuwahata, A., Hirota, R., Sukhbaatar, A., Kodama, T. & Yabukami, S. Wireless temperature monitoring by using magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications on magnetic hyperthermia treatment. AIP Adv. 13 https://doi.org/10.1063/9.0000557 (2023).

Weaver, J. B., Rauwerdink, A. M. & Hansen, E. W. Magnetic nanoparticle temperature Estimation. Med. Phys. 36, 1822–1829. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3106342 (2009).

Garaio, E., Collantes, J. M., Garcia, J. A., Plazaola, F. & Sandre, O. Harmonic phases of the nanoparticle magnetization: an intrinsic temperature probe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4931457 (2015).

Atkinson, W. J., Brezovich, I. A. & Chakraborty, D. P. Usable frequencies in hyperthermia with thermal seeds. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-31. 70-75 https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.1984.325372 (1984).

Hergt, R. & Dutz, S. Magnetic particle hyperthermia-biophysical limitations of a visionary tumour therapy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 311, 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.10.1156 (2007).

Fukumura, R. et al. Study of the physicochemical properties of drugs suitable for administration using a lymphatic drug delivery system. Cancer Sci. 112, 1735–1745. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14867 (2021).

Palanisamy, S. & Wang, Y. M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticulate system: Synthesis, targeting, drug delivery and therapy in cancer. Dalton Trans. 48, 9490–9515. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9dt00459a (2019).

Xu, D. et al. Hyperthermia promotes M1 polarization of macrophages via exosome-mediated HSPB8 transfer in triple negative breast cancer. Discover Oncol. 14 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-023-00697-0 (2023).

Liu, J., Geng, X., Hou, J. & Wu, G. New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: key modulators in cancer progression. Cancer Cell. Int. 21, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02089-2 (2021).

Lescoat, A. et al. M1/M2 polarisation state of M-CSF blood-derived macrophages in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78 https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214333 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 26, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-019-0568-z (2019).

Gobbo, O. L., Sjaastad, K., Radomski, M. W., Volkov, Y. & Prina-Mello, A. Magnetic nanoparticles in cancer theranostics. Theranostics 5, 1249–1263. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.11544 (2015).

Kuwahata, A., Adachi, Y. & Yabukami, S. Ultra-short pulse magnetic fields on effective magnetic hyperthermia for cancer therapy. AIP Adv. 13 https://doi.org/10.1063/9.0000558 (2023).

Adachi, Y., Kuwahata, A., Nakamura, E. & Yabukami, S. Enhancing heating efficiency of magnetic hyperthermia using pulsed magnetic fields. AIP Adv. 14, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1063/9.0000702 (2024).

Reimer, P., Balzer, T. & Ferucarbotran (eds) (Resovist): A new clinically approved RES-specific contrast agent for contrast-enhanced MRI of the liver: Properties, clinical development, and applications, Eur Radiol 13 1266–1276. (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-002-1721-7

Bordelon, D. E. et al. Magnetic nanoparticle heating efficiency reveals magneto-structural differences when characterized with wide ranging and high amplitude alternating magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 109 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3597820 (2011).

Wang, S. Y., Huang, S. & Borca-Tasciuc, D. A. Potential sources of errors in measuring and evaluating the specific loss power of magnetic nanoparticles in an alternating magnetic field. IEEE Trans. Magn. 49, 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2012.2224648 (2013).

Li, L., Mori, S., Sakamoto, M., Takahashi, S. & Kodama, T. Mouse model of lymph node metastasis via afferent lymphatic vessels for development of imaging modalities. PLoS One. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055797 (2013).

Kuwahata, A., Kaneko, M., Chikaki, S., Kusakabe, M. & Sekino, M. Development of device for quantifying magnetic nanoparticle tracers accumulating in Sentinel lymph nodes. AIP Adv. 8 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5006668 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank A. Yamazaki and Y. Kamijima for quantification of the iron deposition areas.

Funding

UCL-Tohoku University Strategic Partner Funds (A.K.) AMED (Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development) under Grant Number 23he0422030j0001, 24he0422030j0002 (A.K.). JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers JP23H03721, JP23K28410 (A.K.) Uehara Memorial Foundation (A.K.) Suzuken Memorial Foundation (A.K.) Nakatani Foundation (A.K.). Iketani Science Foundation (A.K.) JSPS Kakenhi grant numbers 20K20161, 22K18203 (A.S.) Suzuken Memorial Foundation (A.S.) JSPS Kakenhi grant numbers 21K18319 and 23H00543 (T.K.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Akihiro Kuwahata: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Ariunbuyan Sukhbaatar: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Akihiro Shikano: Investigation, Software. Loi Tonthat: Investigation, Software. Takayuki Kagami: Investigation. Riku Shinohara: Investigation. Shiro Mori: Methodology, Validation, Visualization. Shin Yabukami: Conceptualization, Resource, Supervision, Project administration. Tetsuya Kodama: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resource.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuwahata, A., Sukhbaatar, A., Shikano, A. et al. Magnetic hyperthermia using iron oxide nanoparticles via LDDS suppressed lymph node and lung metastasis in a mouse model. Sci Rep 15, 41933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25808-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25808-5