Abstract

The beneficiation of indigenous high ash bituminous coal is crucial for optimizing its suitability for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) in the steel industry. This study investigates the impact of size and density-based beneficiation on key coal properties, including proximate and ultimate analysis, calorific value, organic petrography, swelling index and thermal analysis. The raw coal, with an initial ash content of 28.73%, volatile matter of 19.43%, and fixed carbon of 51%, goes through density separation into fractions ranging from 1.3 to 1.8 kg/m3. The < 1.44 kg/m3 fraction shows a significant reduction in ash content average 16.23% in all sizes with total recovery of 32.58%, which attracted investigations to assess its utilisation potential as PCI coal after blending it with very low ash imported non-coking coal. Furthermore, beneficiated coal with a density of < 1.44 kg/m3 reveals an optimal volatile matter content of 21.62% and fixed carbon above 61.46%, aligning with PCI specifications. Our study also magnifies the importance of maceral composition and vitrinite reflectance (Ro%), with low-density fractions (< 1.44 kg/m3) containing 62.4–77.8% vitrinite, enhancing combustion efficiency. Ultimate analysis endorses that the < 1.44 kg/m3 density fraction, with an average carbon content of 73.46% and minimal sulphur < 0.42%, ensures efficient energy transfer. Gross Calorific Value (GCV) unveils that this fraction consistently provides energy outputs between 6642 and 8355 kcal/kg, making it the most suitable for PCI applications. Thermal analysis (DSC-TGA-DTG) of the beneficiated coal samples revealed combustion profiles closely aligned with imported PCI coal, confirming their compatibility with significant recovery yield (32.58%), and the successful blending strategy that brings the final ash content to within PCI specifications (9.59%). The potential for synergistic effects in blended combustion further reinforces their suitability for efficient PCI application. This study accentuates the strategic advantage of beneficiation in reducing dependency on imported PCI coal, enhancing domestic resource utilization, and promoting cost-effective steel production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

India is the second-largest producer of crude steel, a crucial material for any country’s infrastructure, but its production is directly influenced by the availability of good quality coal1. Despite being the second-largest producer of coal2, India’s coking coal reserves are insufficient to meet the country’s demand. High-quality coking coal is declining worldwide, while demand is increasing due to infrastructure development and rapid growth3,4,5. The global demand for energy and steel has intensified the need for efficient and sustainable utilization of raw materials in metallurgical processes6. Direct injection of pulverized coal into blast furnaces as pulverized coal injection (PCI) has emerged as a crucial technology in blast furnace operations ensures operational flexibility and contributes to substantial benefits by reducing the consumption of costly metallurgical coke, lowering greenhouse gas emissions, and enhancing overall furnace efficiency7. However, the effectiveness of PCI heavily depends on the quality or characteristics of the injected coal. India, as one of the largest producers and consumers of coal, possesses potential reserves of bituminous coal2. Despite this, the steel industry in India faces challenges due to the inherent variability in the quality of indigenous bituminous coal for its utilisation as PCI coal8. These challenges include the presence of high ash content, heterogeneity in maceral composition, and the presence of mineral impurities (silica, alumina, iron, manganese, calcium, etc.) all of which adversely affect the performance of PCI process. This necessitates innovative approaches to enhance the usability of indigenous bituminous coal for PCI applications, thereby minimizing dependence on imported coals and nurturing energy security. In blast furnace operations, coal plays a dual role providing the requisite thermal energy for the reduction of iron oxides and acting as a carbon source, reducing agent for the production of molten iron9,10. PCI technology aligns with the broader goals of resource conservation and economic sustainability12 and high-quality PCI coal must possess attributes such as low ash content < 11%, high fixed carbon > 50%, appropriate volatile matter 20–32%, and favourable grindability (Table 1). Also, it must ensure good combustion performance and low sulphur and phosphorus content to minimize adverse effects on the furnace operation and steel quality11.

The injection of pulverized coal demands stringent preparation methods to ensure the desired physical and chemical properties. The preparation of PCI coal often involves comminution, beneficiation, and blending to meet the specific requirements of blast furnace operations23,24. Although imported coals are often preferred for PCI due to their superior quality, they come with high cost and logistical challenges. This stresses the need for developing personalized beneficiation techniques for indigenous bituminous coal25. Indian bituminous coal, due to the geological history of formation, is characterized by high ash content, often exceeding 25–30%, making it unsuitable for direct use in PCI, as it reduces energy efficiency and increases slag formation in blast furnaces26,27. The variability in mineralogical and maceral composition adds to the complexity of coal utilization28. High reactive macerals content, such as vitrinite content, is highly essential for achieving efficient combustion in PCI applications, but their abundance and distribution can vary significantly within the coal seams29. Another critical issue is the presence of mineral impurities such as pyrite and kaolinite, which contribute to sulphur emissions and ash formation during combustion30,31. These impurities not only impact furnace operation but also raise environmental concerns32. Therefore, there is a compelling need for innovative techniques to upgrade the quality of Indian bituminous coal through processes such as density fractionation and chemical beneficiation33, which are the most promising methods for upgrading the quality of indigenous high ash bituminous coal33. Density fractionation influences the differences in the density of coal components to separate high-ash, inert material from cleaner, more reactive fractions34. This technique is particularly effective in reducing ash content and concentrating macerals of interest, such as vitrinite.

Chemical beneficiation, on the other hand, provides a complementary approach by targeting mineral impurities that are difficult to remove through physical methods35. Techniques such as acid leaching, alkali washing, and bio-beneficiation have shown potential in removing sulphur, phosphorus, and other deleterious elements36. Chemical beneficiation not only enhances the combustion performance of coal but also reduces environmental emissions, aligning with the goals of sustainable coal utilization37. The integration of these methods can produce a coal product that meets the stringent requirements of PCI, ensuring optimal performance in blast furnace operations. These techniques enable the effective utilization of high-ash and marginal coal reserves, contributing to resource efficiency and economic viability. In this context, the proposed research attempts towards the utilization of indigenous high ash bituminous coal for PCI applications through a combination of density fractionation and chemical beneficiation techniques with detailed analysis of the physical, chemical, and petrographic properties of Indian bituminous coal, with assessment of ash content, maceral composition, and mineral impurities.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) are widely used thermal techniques for characterizing the combustion behaviour of coal. TGA provides insight into the mass loss pattern as a function of temperature, allowing identification of devolatilization, fixed carbon combustion, and burnout phases. DSC complements this by measuring heat flow associated with physical and chemical transitions, including exothermic combustion reactions. Together, TGA and DSC enable precise determination of key combustion parameters such as ignition temperature, peak reactivity, and burnout efficiency. These techniques are particularly valuable for evaluating the suitability of coal for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) applications25.

This study therefore focuses on solving the utilization problem of indigenous high-ash bituminous coal through density separation technology. We systematically demonstrate how this approach can transform suboptimal domestic coal into a viable PCI resource by identifying optimal density fractions that meet critical PCI specifications, thereby offering a practical solution to enhance resource efficiency and reduce reliance on imported coal.

Methods and materials

Nature of coal deposit

The Jharia coalfield in Dhanbad district of Jharkhand is located in the eastern part of India and stretches around 38 kms in east-west direction of the Singhbhum craton and 18 kms in the north-west direction5. Renowned for its rich bituminous coal reserves, Jharia plays a crucial role in India’s steel industry17. This coalfield is part of the Damodar Valley coalfields and primarily consists of rocks belonging to the Gondwana formations of Permian age. The Jharia coalfield is sickle-shaped synclinal basin with an east-west alignment which covers about 456 km2 in the total area enclosed by latitudes 23°37′:23°52′N, longitudes 86°06′:86°30′E and roughly located 260 km in the northwest direction of Kolkata38. The coal seam of the Jharia basin is formed between the Lower Permian of Barakar and the Upper Permian of Raniganj within the lower Gondwana sequence30. The fluviatile deposits, representing the lowest member, are an important Barakar formation of the Lower Permian Jharia coalfield. Eighteen coal seams out of a total of thirty main coal seams are of the Barakar Formation, and the remaining twelve are from the Raniganj Formation. Jharia is among the important coal seams that have the source which reflect prime coking nature39.

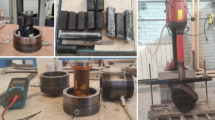

Collection and Preparation of coal samples

Coal is characterized by significant heterogeneity in both its physical and chemical properties27. To ensure the proper collection and preparation of a representative sample, the standards outlined in IS 436 Standard40 were closely followed. Approximately 1000 kg of indigenous high ash bituminous coal samples were collected from the stockpile of open-cast mines in the Jharia coalfield for laboratory studies41. The samples were dried at room temperature (24 °C), and these were then thoroughly mixed and piled up into a cone-shaped heap; the top of the cone was flattened by pressing over it, and two lines were drawn approximately at right angles across the flattened top of the heap. Further, the flattened sample was divided along the lines to form four smaller quarters of equal size, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Two of the segments from opposite sides were discarded, and the remaining two segments were again piled up into a new cone for a similar process. The subsequent time, the segments of other opposite sides were discarded. This process of coning-and-quartering was repeated for the new cone until we got the desired 500 kg required for size analysis, following the standard methods specified in Indian Standard (IS) 13,81042. Subsequent size analysis of the sample was conducted according to the IS 13,81042. The samples were crushed to below 25 mm to ensure homogeneity before undergoing size fractionation. The size analysis was conducted by classifying the pulverized coal into distinct fractions: -25 mm to + 13 mm, -13 mm to + 6 mm, -6 mm to + 3 mm, -3 mm to + 1 mm, and − 1 mm, in accordance with the specified Indian Standard 43743. For detailed analysis, the sample was crushed to 212 μm for proximate, ultimate, total sulphur analysis and free swelling index (FSI) evaluations. For organic petrographic analysis, a sample size of 1.19 mm (16 mesh) was utilized using the standard method mentioned in International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology (ICCP)44,45. This method of preparation ensures the accuracy and reliability of the subsequent analytical results. The sample preparation of coning-quartering method of process has shown in the Fig. 1.

Solution preparation for chemical beneficiation

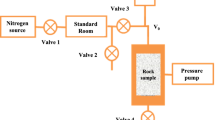

Sink-float density separation, also known as heavy media separation or dense media separation, is a process used to separate materials based on differences in their densities to separate impurities from coal and improve its quality and suitability for various applications46. To prepare solutions of different densities for sink-float beneficiation using Bromoform (density 2.88 kg/m3), Tetrachloroethylene (density 1.66 kg/m3), and Benzol (density 0.88 kg/m3), we have mixed these liquids in specific proportions following the standard procedure outlined in IS 1381046. The density of the prepared solution was checked using a hydrometer.

Density fractionation techniques

Density is a key property of coal, providing valuable information about its physical and chemical composition. Float-and-sink experiments were conducted according to Indian Standard 1381042 for different size fractions and densities. Organic chemical solutions prepared with densities ranging from 1.3 kg/m3 to 1.8 kg/m3 were used for this study. Coal samples that floated on the 1.3 kg/m3 solution were collected, while the heavier samples, having a density higher than 1.3 kg/m3, were immersed in a container with a 1.3 kg/m3 solution. This process was repeated with solutions of 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 kg/m3 densities, a total of 26 samples were obtained. Each sample was prepared using this method, then dried and weighed with an electronic weighing machine for further analysis. A schematic diagram of this process is shown in Fig. 2.

Laboratory analysis

Geochemical analysis and coal petrographic study were conducted on coal samples involving four different components. Proximate analysis was performed to determine the physical properties of the coal samples, including ash, moisture, fixed carbon, and volatile matter, using a Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) as per the ASTM D758247 standard. Ultimate analysis was conducted to quantify the organic elements (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur) in the coal samples using an Elementar instrument as per the ASTM D537348 standard. The coal petrographic study was carried out to analyses the maceral groups (Vitrinite, Inertinite, and Liptinite) in the beneficiated bituminous coal samples using methodologies outlined by the ICCP44,45. This involved preparing coal sample pellets as polished particulate mounts. The samples were studied under a microscope to identify and quantify the different maceral groups based on their optical properties and morphological characteristics. The swelling index of the coal samples was determined using the Indian Standard 1353 Part-I49. The procedure included placing coal samples in a crucible, heating them in 800 °C to 820 °C, observing the degree of swelling, and comparing the results to standard reference samples to determine the swelling index50.

Differential scanning calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis

The combustion performance of the beneficiated coals, along with a reference PCI coal, was studied using a Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA 409 C, NETZSCH, Germany), which enables the simultaneous recording of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) profiles. For each experiment, approximately 20 mg of accurately weighed sample was placed in a crucible with uniform packing of the particles. The sample holder assembly was then inserted into the furnace, and the temperature was increased up to approximately 750 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C min under a continuous air flow of 50 cm3 min−1. Combustion characteristic parameters were derived from the DSC and Derivative Thermogravimetric (DTG) curves. The DTG curve, representing the first derivative of the TGA profile, was utilized to determine the temperatures corresponding to maximum weight loss rates and distinct combustion stages.

Results and discussion

Proximate analysis

The proximate analysis of the bituminous coal sample discloses the visualizations of the effects of size and density-based beneficiation on coal quality. The raw indigenous bituminous coal, termed as the head sample as a baseline, shows a moisture content of 0.84%, ash content of 28.73%, volatile matter at 19.43%, and fixed carbon of 51%. The fractions of -25 to + 13 mm and − 3 to + 1 show the average moisture content of 0.89%, and the average fixed carbon is 51.96% consistent in ash yield. It is clear that just processing the sample in different size fractions does not have any effect on its physical parameters (Fig. 3). The beneficiated bituminous coal samples analysed within the size ranges of 1–3 mm, 3–6 mm, 6–13 mm, and 13–25 mm at densities below 1.44 demonstrate ash content averaging at 16.23%, volatile matter averaging 21. 62%, and moisture levels consistently below 1% (Table 2). These findings indicate that the beneficiated indigenous bituminous coal fulfils (except ash) the specifications for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) in the steel industry, which requires ash content below 11%, volatile matter under 32%, and moisture content below 3.5%. The beneficiated Indian bituminous coal with low ash content minimizes slag generation, while the controlled volatile matter and moisture ensure efficient combustion and thermal stability during injection, making it a viable substitute for high-cost imported non-coking coal for PCI application. These results show the potential of utilizing indigenous bituminous coal as a replacement for coke in PCI applications within the Indian steel sector. The beneficiation process effectively enhances the coal’s properties, aligning them with industry standards for PCI application. Adoption of this approach not only reduces dependency on imported PCI coal but also leverages domestic resources, contributing to cost efficiency and supporting national energy security. These results emphasize the strategic importance of processing indigenous coal reserves for sustainable industrial applications.

Ultimate analysis

Ultimate analysis of coal plays an important role in optimizing Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI), in blast furnaces to replace coke partially with PCI coal16. The results expose the role of size and density separation in optimizing coal properties for PCI applications in the industry. The analysis suggests that in all size fractions with a density range of < 1.44 kg/m3 shows the most required characteristics, with an average carbon content of 73.46% and a moderate sulphur of less than 0.50% (Fig. 4). This combination suggests efficient energy transfer and minimizing slag formation during injection in blast furnaces. The density separation further refines coal quality by isolating denser fractions that are rich in carbon while discarding mineral impurities, including pyritic sulphur, which can contribute to SOx emissions51. The hydrogen content in entire fractions, ranging from 3.74% to 4.85%, confirms flame stability and enhances combustion efficiency in the furnace raceway52. The ultimate analysis emphasizes the significance of integrating size and density-based beneficiation techniques to maximize coal utilization efficiency, reduce coke consumption, and enhance the cost-effectiveness of steel production. Beneficiation also strategically minimizes slag formation, and controls coke replacement rates without compromising furnace operation.

Gross calorific value (GCV)

Gross Calorific Value (GCV) is an essential parameter for evaluating the energy potential of coal and in determining its suitability for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) applications in the steel industry. The analysis of GCV (kcal/kg) across various size and density fractions reveals conceptualization of optimizing coal for efficient combustion and energy transfer in blast furnaces. The raw coal samples show a GCV (kcal/kg) of 5842, after the size analysis; while the size increases, GCV (kcal/kg) decreases (Fig. 3). Density separation further refines the selection process, with low-density fractions < 1.44 consistently unveiling higher GCV (kcal/kg) due to lower ash and a higher concentration of organic matter, making them ideal for PCI. Medium-density fractions > 1.5–1.7 provide a balance between energy content and availability, contributes practical options for PCI in cost-sensitive operations. The ideal density for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) is < 1.44 density fraction, as it consistently provides the optimal balance of high Gross Calorific Value (GCV), low ash content, and broad compatibility across size fractions. This density fraction shows GCV values ranging from 6642 to 8355 kcal/kg, ensuring efficient energy delivery and combustion in PCI systems. The > 1.5–1.6 density range, with slightly lower GCV (~ 5890 kcal/kg), serves as a secondary option, whereas fractions with densities > 1.6 kg/m3 are unsuitable for PCI due to significantly lower GCV (< 5318 kcal/kg) and higher ash content, leading to inefficiency and operational challenges. The < 1.44 kg/m3 density fraction stands out as the most suitable for PCI, offering an excellent balance of energy efficiency, reduced impurities, and compatibility across commonly used size fractions.

Petrographic analysis

The detailed study of maceral composition, ash content, and vitrinite reflectance (Ro%) across different size and density fractions of indigenous bituminous coal will help in optimizing Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) applications in blast furnaces. Coal petrology plays a vital role in determining the suitability of various coal fractions for PCI, as the process demands specific characteristics, including high reactivity, low ash content, and minimal impurities. The maceral composition analysis revealed the uniform distribution of average vitrinite 67.10%, inertinite 25.58%, and mineral matter 7.33% across the size ranges of -25 to + 13 mm, -13 to + 6 mm, -6 to + 3 mm, and − 3 to + 1 mm as well as raw coal sample (Fig. 5). In all four different sizes of coals, with in densities of < 1.44 kg/m3 contain a higher proportion of vitrinite macerals ranging from 62.40% to 78.80%, a maceral group that is reactive and significantly influences combustion efficiency in PCI applications (Fig. 5). Densities from above 1.44 kg/m3 tend to have relatively higher inertinite content ranging from 29.50% to 45.20%, which is less reactive because Inertinite is derived from plant material that was partially oxidized and thus less desirable for direct PCI use21. The density fraction analysis provides further granularity in understanding the coal’s behaviour under different operational conditions. Low-density fractions < 1.44 kg/m3 predominantly consist of reactive maceral such as vitrinite, and show low mineral matter, an average of 6.2% and an ash content of 16.23% (Table 3). This composition is more or less ideal for PCI21, as it ensures minimal slag formation53 and maximizes combustion efficiency54. High-density fractions > 1.44 kg/m3, on the other hand, are enriched with mineral matter and ash content of an average of 40.77%, which are detrimental to PCI performance due to their tendency to form slag and reduce thermal efficiency (Fig. 6). These heavier fractions may be utilized by the power sector to produce electricity and other industrial applications55.

The role of vitrinite reflectance (Ro%) is another critical factor, as it indicates the thermal maturity and rank of the coal. The Ro% values of indigenous bituminous coal, ranging from 1.19 to 1.20%, classify the coal as rank bituminous coal, which balances between thermal stability and combustion efficiency56. This rank ensures that the coal can withstand the high temperatures of the tuyere zone in a blast furnace without undergoing excessive thermal degradation, while still exhibiting sufficient reactivity for efficient combustion. Geological perspective, the coal’s maceral composition and rank reflect its depositional environment and subsequent thermal history. The dominance of vitrinite macerals in lower-density fractions suggests the prevalence of woody material in the precursor peat swamp, indicative of a forested, terrestrial depositional setting with favourable preservation conditions (Fig. 5). The presence of inertinite in larger-size fractions and higher-density fractions points to periodic oxidative conditions or fire events during peat accumulation, which altered the original organic material. The ash content, which correlates closely with mineral matter, is a critical parameter for PCI, as high ash content can impair furnace efficiency and increase operational costs. By identifying coal fractions with low ash content and high vitrinite concentrations, the maceral distribution analysis gives a clear pathway for maximizing PCI utilization using indigenous bituminous coals. This approach not only improves PCI utilization of indigenous bituminous coal but also contributes to resource sustainability by enabling the selective utilization of high-quality coal fractions. Through such detailed petrological and geochemical analysis, coal producers can optimize their products for specific industrial applications, reducing reliance on imported coals and enhancing energy security.

Representative photomicrographs of maceral groups and mineral are observed under white light illumination (a) A block of collotelinite (Co) is observed (b) Block of collotelinite (Co) with collodetrinite (Cd) is observed (c) Inertinite group of maceral Semifusinite (Sf) is observed (d) Fusinite (Fu) is clearly observed on groundmass of vitrinite (e) Mineral matter (Mm) is observed on scattered mass of vitrinite grain (f) High amount of mineral matter (Mm) can be observed in the block.

Swelling index

The swelling index (also known as the Free Swelling Index, FSI) of coal is an essential parameter in evaluating its suitability for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) applications in blast furnaces. In PCI, coal is injected in a finely pulverized (72 micron) form and combusts rapidly in the blast furnace. Coal with a low to moderate swelling index 1 to 3 is ideal for PCI22 because it minimizes the risk of agglomeration or clogging of injection lines. Because the performance of the PCI process depends on the fluidity and reactivity of the coal particles. The swelling index analysis was conducted on size different fractions of -25 to + 13 mm, -13 to + 6 mm, -6 to + 3 mm, and − 3 to + 1 mm, and different densities ranges of 1.3–1.4 kg/m3, 1.4–1.5 kg/m3, 1.5–1.6 kg/m3, 1.6–1.7 kg/m3, 1.7–1.8 kg/m3 and beyond 1.8 kg/m3, reveals a systematic variation in the Swelling Index (SI) across different classifications. The lower density fractions (1.3–1.4 kg/m3 and 1.4–1.5 kg/m3) show lower swelling indices across all size ranges an average swelling index of < 3.6, aligning well with PCI requirements (Table 1). These fractions contain a proportion of reactive and non-reactive macerals ratio of 70:30 respectively, and low volatile matter < 25%, contributing to their stable combustion behaviour and reduced tendency for swelling. When separated at lower densities < 1.44 kg/m3, it demonstrates optimal SI values, suggesting that these finely sized particles provide improved surface area for combustion, facilitating rapid and complete burning in PCI applications (Fig. 7). Higher density fractions > 1.5 kg/m3 consistently show lower swelling index values, an average < 1, though the swelling index is less due to high ash content ~ 40% less suitable for PCI due to potential operational challenges.

Differential scanning calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis

The DSC-TG-DTG profiles, indicating the combustion reactivity of all the beneficiated coal samples, were compared with those of an imported PCI coal sample used as the reference. Initially, the reactivity profiles of the 1.3–1.4 kg/m3 density fraction samples were compared with those of the imported PCI coal, followed by a similar evaluation for the 1.4–1.5 kg/m3 density fraction. As illustrated in Figs. 8 (a–d), the thermal behaviour of bituminous coal fractions of four different sizes within the density ranges of > 1.3 to < 1.4 kg/m3 (Fig. 8a, b) and > 1.4 to < 1.5 kg/m3 (Fig. 8c, d) was systematically evaluated using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). In the DSC profile for the lower density fraction (> 1.3 to < 1.4 kg/m3), shown in Fig. 8a, a pronounced endothermic dip below 150 °C indicates moisture loss, followed by sharp exothermic peaks between 300 and 500 °C associated with the combustion of volatile matter and high reactivity. A moderate exothermic signal in the 500–600 °C range further signifies the onset of fixed carbon combustion. Correspondingly, the DTG curve in Fig. 8b displays a sharp peak between 300 and 500 °C, highlighting a high mass loss rate due to devolatilization.

The initial combustion temperature (Ti) for indigenous samples ranged from 373.5 °C to 410.2 °C, comparable to 337.2 °C of imported PCI coal indicating high initial reactivity. Peak reactivity values (Rmax) for indigenous coals ranged between 7.33%/min and 8.08%/min substantially higher than the 6.85%/min observed in the imported PCI suggesting more intense combustion. The burnout temperatures (Tb) of the beneficiated samples, extending up to 600.6 °C, also paralleled that of the imported PCI coal (567.7 °C), demonstrating a complete and sustained combustion phase. DSC volatile combustion peaks (Tv) and char combustion peaks (Tc) of all samples consistently occurred within 320–340 °C and 480–500 °C, respectively, indicating synchronized energy release.

The intensity and narrowness of this peak reflect efficient volatile release and combustion. The minimal presence of secondary peaks and low residual mass indicate reduced mineral matter and a cleaner combustion profile, underscoring the suitability of this density fraction for PCI use. When compared to the thermal profile of imported PCI coal, the lower density fraction shows closely aligned combustion pattern, effectively mimicking the thermal behaviour preferred in PCI operations. A similar alignment is observed for the 1.4–1.5 kg/m3 density fraction (Fig. 8c, d), wherein both the volatile and char combustion peaks of the beneficiated coals correspond well with those of the reference imported PCI coal in both DSC and DTG profiles. Such overlapping thermal behaviour indicates that blending these indigenous coals with imported PCI coal may result in synergistic interactions, potentially enhancing the combined reactivity beyond simple additive effects. The characteristic combustion parameters, including initial combustion temperature (Ti), DSC peak temperatures, DTG peak temperature (Tp), burnout temperature (Tb), and maximum reactivity (Rmax), are summarized in Table 4. These data confirm that the beneficiated coal samples exhibit combustion characteristics comparable to the imported PCI coal, supporting their potential as viable blend components. Moreover, it is evident that variations in particle size within each density fraction exert minimal influence on the overall combustion behaviour, highlighting the consistency and robustness of these beneficiated coals for practical PCI applications.

Impact of beneficiation on pulverized coal injection (PCI)

Based on the study conducted, the beneficiation of indigenous high ash bituminous coal yields remarkable results with valuable implications for the steel sector in optimizing Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI). The high ash bituminous coal, after beneficiation into different size fractions (-25 mm to + 13 mm, -13 mm to + 6 mm, -6 mm to + 3 mm, -3 mm to + 1 mm, and − 1 mm) and density ranges 1.3 to 1.8 kg/m3, shows that coal with a density of < 1.44 kg/m3 has an ash yield of average 16.23% across all size fractions, with recovery of 32.58% from all the sizes, the recovery of beneficiated bituminous coal are given in Table 5.

Recovery = 32.58%.

The beneficiated bituminous coal ash content significantly decreases to lower density i.e. <1.44 kg/m3 (Fig. 9a). Although the beneficiated coal does not meet the required parameters for direct use in the steel industry, it can be blended with imported non-coking coal to achieve the desired ash content of < 11% for PCI. Correspondingly, another important parameter for PCI coal is volatile matter (VM). The beneficiated coal with a density of < 1.44 kg/m3 across all size fractions exhibits an average VM of 21.62%, which is directly suitable for PCI, as the required VM for PCI coal is 20–32%13. Additionally, fixed carbon (FC) and moisture (M) content are crucial parameters for PCI. The required fixed carbon for PCI is > 50%, while the moisture content should be < 3.5%11,12. In this study, the beneficiated coal with a density of < 1.44 kg/m3 across all size fractions has an average FC of > 63.90% and a moisture content of < 1%, fully meeting the required parameters for PCI in the steel industry (Table 1). Except for ash content, all other parameters of proximate analysis match the requirements for Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) after beneficiation. To reduce the ash content of beneficiated bituminous coal, blending with imported non-coking coal57 at a ratio of 30% beneficiated bituminous coal to 70% imported non-coking coal results in an output ash yield of 9.59%, making it suitable for utilization in PCI. Likewise, statically analysed for different ratios like 10:90, 15:85, 20:80, and 25:75. The blending ratio of beneficiated bituminous coal with imported non-coking coal given in Table 6.

Conclusions

The petrographic characterization and experimental outcomes obtained in this study establish that the beneficiation of indigenous high ash bituminous coal significantly enhances its potential for PCI applications in the steel industry. Size and density fractionation effectively reduce ash content while improving key PCI parameters, making indigenous coal a viable substitute for high cost imported PCI coal. The < 1.44 kg/m3 density fraction consistently reveals favourable properties, including average ash content of 16.23%, volatile matter of 21. 62%, and fixed carbon above 50%, closely matching PCI requirements after blending with imported PCI coals (Fig. 9b). The maceral composition analysis further confirms that low-density fractions, enriched in vitrinite (62.4–77.8%), ensure high reactivity and combustion efficiency. The study establishes that the optimal PCI fraction < 1.44 kg/m3 provides the best balance of high Gross Calorific Value 6642–8355 kcal/kg, low ash content, and enhanced energy transfer. Ultimate analysis endorses that this fraction contains an average of 73.46% carbon with minimal sulphur < 0.50%, reducing the SOx emissions and slag formation in blast furnaces. Petrographic and swelling index analyses reinforce the suitability of these fractions, as they exhibit controlled fluidity and stability during PCI combustion. The DSC-TGA-DTG thermograms of the beneficiated indigenous bituminous coal samples demonstrated synchronized combustion profiles with the imported PCI coal, indicating strong compatibility in thermal behaviour. The derived reactivity parameters further affirm the technical viability and economic attractiveness of blending indigenous beneficiated coal with imported PCI coal. The observed combustion characteristics suggest the potential for synergistic effects, where the combined performance of the blend may surpass the simple additive effects of individual components, thereby enhancing overall efficiency in Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) applications. This proposed blending strategy offers a sustainable and cost-effective approach, with significant potential to reduce reliance on imported PCI coal and contribute to national energy security by conserving foreign exchange. By optimizing the blending ratio of beneficiated Indian bituminous coal with imported non-coking coal (30:70), the final ash content is reduced to 9.59%, meeting PCI specifications. The beneficiation of indigenous high ash bituminous coal boons a sustainable strategy for reducing import dependency, enhancing domestic coal utilization, and improving the cost-effectiveness of steel production. By aligning coal preparation techniques with the requirements of industrial applications and implementing large-scale beneficiation and blending techniques can drive economic benefits, supporting the long-term sustainability of India’s steel industry to meet the demand of modern steel production.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. (P. Gopinathan [srigopi555@gmail.com](mailto: srigopi555@gmail.com) )

References

Steel Mo. India Is Currently the World’s 2nd Largest Producer of Crude Steel in January - December 2021, Producing 118.20 Million Tonnes (MT) Crude Steel with Growth Rate 17.9% Over the Corresponding Period Last Year (CPLY) (Steel Mo, 2022).

Coal Mo. India has a total coal reserve of 344.02 billion tonnes and is the second largest producer of coal in the world (2023).

Abhyankar, N. et al. India’s path towards energy independence and a clean future: Harnessing india’s renewable edge for cost-effective energy independence by 2047. Electricity J. 36, 107273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2023.107273 (2023).

Pudasainee, D., Kurian, V. & Gupta, R. 2 - Coal: Past, Present, and Future Sustainable Use. In: Letcher TM, editor. Future Energy (Third Edition): Elsevier; pp. 21–48. (2020). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081028865000025

Saikia, K. & Sarkar, B. C. Coal exploration modelling using geostatistics in Jharia coalfield, India. Int. J. Coal Geol. 112, 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2012.11.012 (2013).

Wang, R. Q., Jiang, L., Wang, Y. D. & Roskilly, A. P. Energy saving technologies and mass-thermal network optimization for decarbonized iron and steel industry: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 274, 122997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122997 (2020).

Sun, W., Wang, Q., Zhou, Y. & Wu, J. Material and energy flows of the iron and steel industry: status quo, challenges and perspectives. Appl. Energy. 268, 114946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114946 (2020).

Brooks, B., Rish, S. K., Lomas, H., Jayasekara, A. & Tahmasebi, A. Advances in low carbon cokemaking – Influence of alternative Raw materials and coal properties on coke quality. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 173, 106083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106083 (2023).

Smil, V. Chapter 6 - Materials in modern iron and steel production: Ores, Coke, Fluxes, Scrap, and other inputs. In: (ed Smil, V.) Still the Iron Age. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 115–138. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128042335000063. (2016).

Nassaralla, C. L. Iron production. In: (eds Buschow, K. H. J., Cahn, R. W., Flemings, M. C., Ilschner, B., Kramer, E. J., Mahajan, S. et al.) Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology. Oxford: Elsevier; 4296–4301. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0080431526007543. (2001).

Phillip Bennett, T. F. Impact of PCI coal quality on blast furnace operations. pp. 1–11. (2003).

Du, S-W., Chen, W-H. & Lucas, J. Performances of pulverized coal injection in blowpipe and Tuyere at various operational conditions. Energy. Conv. Manag. 48, 2069–2076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2007.01.013 (2007).

Barbieri, C. C. T. & Antonio Cezar Faria Vilela. EO,. Combustibility and reactivity of coal blends and charcoal fines aiming use in ironmaking. 19. 2016;3. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2015-0705

Kalkreuth, W. et al. Exploring the possibilities of using Brazilian subbituminous coals for blast furnace pulverized fuel injection. Fuel 84, 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2004.11.007 (2005).

de Castro, J. A., Araújo, G. M., da Mota IdO, Sasaki, Y. & Yagi, J. Analysis of the combined injection of pulverized coal and charcoal into large blast furnaces. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2, 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2013.06.003 (2013).

Carpenter, A. M. Use of PCI in Blast Furnaces: IEA Clean Coal Centre London (UK, 2006).

Zhang, J. et al. Kinetic and experimental analysis of the effect of particle size on combustion performance of low-rank coals. Fuel 349, 128675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128675 (2023).

Beér, J. M. Electric power generation: fossil fuel. In: (ed Cleveland, C. J.) Encyclopedia of Energy. New York: Elsevier; 217–228. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B012176480X00509X. (2004).

Nightingale, R., Mathieson, J. & Di Giorgio, N. Understanding the improved blast furnace operations at Port Kembla associated with the introduction of pulverised coal injection. 3rd International Conference on Science and Technology of Ironmaking 172–180 (2003).

Bennett P F, T. Impact of PCI coal quality on blast furnace operations (CLA, 2003).

Ishii, K. Advanced Pulverized Coal Injection Technology and Blast Furnace Operation (Elsevier, 2000).

Sexton, D. C., Steer, J. M., Marsh, R. & Greenslade, M. Investigating char agglomeration in blast furnace coal injection. Fuel Process. Technol. 178, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.05.013 (2018).

Cheng, X., Cheng, S., Liu, K. & Zhou, D. Measurement study of preheated pulverized coal injection on combustion in a blast furnace raceway by visual detection. Fuel 271, 117626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117626 (2020).

Majumder, A. K. & Barnwal, J. P. Development of a new coal washability index. Miner. Eng. 17, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2003.10.005 (2004).

Sahu, S. G. et al. Evaluation of combustion behaviour of coal blends for use in pulverized coal injection (PCI). Appl. Therm. Eng. 73, 1014–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.08.071 (2014).

Mohanty, A., Chakladar, S., Mallick, S. & Chakravarty, S. Structural characterization of coking component of an Indian coking coal. Fuel 249, 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.03.108 (2019).

Gopinathan, P. et al. Geochemical characteristics, origin and forms of sulphur distribution in the Talcher coalfield, India. Fuel 316, 123376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123376 (2022).

Keboletse, K. P., Ntuli, F. & Oladijo, O. P. Influence of coal properties on coal conversion processes-coal carbonization, carbon fiber production, gasification and liquefaction technologies: a review. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 8, 817–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-020-00401-5 (2021).

Singh, P. K. Applicative coal petrology for industries: new paradigms. J. Geol. Soc. India. 98, 1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12594-022-2157-0 (2022).

Gupta, A. Early permian palaeoenvironment in Damodar Valley Coalfields, india: an overview. Gondwana Res. 2, 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1342-937X(05)70140-4 (1999).

Liu, L., Liu, Q., Zhang, S., Li, Y. & Yang, L. The thermal transformation behavior and products of pyrite during coal gangue combustion. Fuel 324, 124803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124803 (2022).

Gopinathan, P., Singh, A. K., Singh, P. K. & Jha, M. Sulphur in Jharia and Raniganj coalfields: chemical fractionation and its environmental implications. Environ. Res. 204, 112382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112382 (2022).

Karmakar, A. et al. Transformation in energy content of non-coking coals during differential settling beneficiation process: implications for energy impact. Fuel 377, 132662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132662 (2024).

Gupta, V. & Mohanty, M. K. Coal Preparation plant optimization: A critical review of the existing methods. Int. J. Miner. Process. 79, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.minpro.2005.11.006 (2006).

Majumder, A. K. et al. Applicability of a Dense-Medium cyclone and Vorsyl separator for upgrading Non-Coking coal fines for use as a blast furnace injection fuel. Int. J. Coal Preparation Utilization. 29, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392690802628754 (2009).

Behera, S. K. Meikap review of chemical leaching of coal by acid and alkali solution. J. Min. Metall. https://doi.org/10.5937/JMMA1801001B (2018).

Ramudzwagi, M., Tshiongo-Makgwe, N. & Nheta, W. Recent developments in beneficiation of fine and ultra-fine coal -review paper. J. Clean. Prod. 276, 122693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122693 (2020).

Das, P. R. et al. Petrographic and geochemical controls on methane Genesis, pore fractal Attributes, and sorption of lower Gondwana coal of Jharia Basin, India. ACS Omega. 7, 299–324. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c02040 (2022).

Pal, P. K., Paul, S. & Chatterjee, R. Estimation of In-situ stress and coal bed methane potential of coal seams from analysis of well Logs, ground mapping and laboratory data in central part of Jharia coalfield—An overview. In: (ed Mukherjee, S.) Petroleum Geosciences: Indian Contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03119-4_6. (2015).

Standard, I. Indian Standard 436 Part-I Sec-I. 1964:2005.

Kumar, O. P. et al. Characterization of lignite deposits of barmer Basin, rajasthan: insights from mineralogical and elemental analysis. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 6471–6493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-023-01649-x (2023).

13810 I. Code for practice for float and sink analysis of coal first revision. 1993:2023.

437 IS. Size Analysis of Coal and Coke for Marketing (Fourth Revision) (2020).

ICCP. The new vitrinite classification ICCP system 1994. Fuel 77, 349–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(98)80024-0 (1998).

Pickel, W. et al. Classification of liptinite – ICCP system 1994. Int. J. Coal Geol. 169, 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2016.11.004 (2017).

Kundu, T., Das, S. K., Biswal, D. K. & Angadi, S. I. Mineral beneficiation and processing of coal. In: (eds Jyothi, R. K. & Parhi, P. K.) Clean Coal Technologies: Beneficiation, Utilization, Transport Phenomena and Prospective. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68502-7_1. (2021).

D7582 A. Standard Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of Coal and Coke by Macro Thermogravimetric Analysis (2024).

D5373 A. Standard Test Methods for Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen in Analysis Samples of Coal and Carbon in Analysis Samples of Coal and Coke (2021).

Part-I, I. Method of test for coal carbonization: part 1 determination of the crucible swelling number (Second Revision) (2018).

Ünsal, B. Investigation of Factors Affecting Coke Strength After Reaction (CSR) and Developing a Statistical Model for CSR Prediction (Middle East Technical University, 2018). https://www.proquest.com/openview/b2359f645b02a07992ddd5a9a2ee0c09/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

Karmakar, A. Organo petrographic insights into the behaviour of coking and Non coking coals during coal beneficiation (2025). http://hdl.handle.net/10603/633497

Ren, M. et al. Effects of hydrogen fraction in co-injection gas on combustion characteristics of the raceway in low carbon emission blast furnace. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48, 11530–11540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.06.106 (2023).

Van Dyk, J., Benson, S., Laumb, M. & Waanders, B. Coal and coal Ash characteristics to understand mineral transformations and slag formation. Fuel 88, 1057–1063 (2009).

Kurose, R., Ikeda, M. & Makino, H. Combustion characteristics of high Ash coal in a pulverized coal combustion. Fuel 80, 1447–1455 (2001).

Rashid, M. I., Isah, U. A., Athar, M. & Benhelal, E. Energy and chemicals production from Coal-based technologies: A review. ChemBioEng Reviews. 10, 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/cben.202200023 (2023).

Ghosh, B. et al. Understanding the impact of coal blend properties on the coke strength. Coke Chem. 65, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1068364X22070043 (2022).

Friederich, M. C. & van Leeuwen, T. A review of the history of coal exploration, discovery and production in indonesia: the interplay of legal framework, coal geology and exploration strategy. Int. J. Coal Geol. 178, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2017.04.007 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Gopinathan expresses his sincere appreciation to the Director of CSIR-CIMFR for the encouragement and support. He is also deeply grateful to his co-authors for their significant and invaluable contributions, which were critical to the successful completion of this research article. Special acknowledgement is extended to the dedicated project staff for their indispensable assistance during the sample collection process in the mining regions of the Jharia coalfield.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amit Karmakar: Beneficiation Study, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Investigation. P. Gopinathan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing-original draft. T. Subramani: Writing-review & editing. Amiya S. Naik: Writing-review & editing. Manoj Kr. Sethi: Geochemical Analysis & Data curation. M. Santosh: Writing-review & editing. Pinaki Sarkar: Writing-review & editing. Pradip Kr. Banerjee: Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karmakar, A., Gopinathan, P., Subramani, T. et al. Optimizing the use of Indigenous high ash bituminous coal for sustainable pulverized coal injection and efficient energy transfer. Sci Rep 15, 40061 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25845-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25845-0