Abstract

Distributed coordination of a swarm of drones is one of the inherent open problems in autonomous aerial robotics, as classical approaches suffer from slow convergence and poor resilience to disturbances. In this paper, an efficient and robust approach to shape formation of drone swarms is offered based on Quantum-Enhanced Artificial Potential Field (QEAPF). This method combines quantum-inspired probabilistic discovery mechanisms with Artificial Potential Field (APF) techniques. By incorporating adaptive parameter tuning, explicit disturbance estimation and compensation, and quantum-inspired probabilistic exploration. QEAPF significantly demonstrates improvements in formation convergence time, path efficiency, and disturbance rejection capabilities. Thorough simulation-based evaluations of the QEAPF method produce up to a 37% improvement in formation convergence time and a 42% improvement in disturbance rejection performance compared to traditional APF techniques. QEAPF has been shown to smoothly organize itself into a target configuration while maintaining collision avoidance, energy efficiency, and geometric integrity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, drones have become one of the most important tools in various fields1. The drones can be deployed as single or multi-drones commonly known as swarm deployment. A single drone deployment is when one drone tries to perform a task over an area, such as optimizing a single drone deployment to cover and serve users inside the network as much as possible2. The use of drone swarms has dramatically expanded the capabilities of autonomous systems in various fields3. This integration marks a significant change in the way these systems function and operate4. One feature that has attracted much interest in both academic and real-world applications is the ability of drone swarms to dynamically generate and maintain shape formation in cooperative missions5. Drone swarms are used for traffic surveillance, load transportation, and agricultural analytics6.

The fundamental ideas for understanding collective behavior of swarms were established by Reynolds’ work on the Boid model in 1987. He focused on local interactions and straightforward rules that result in emergent complex structures7. However, achieving efficient and robust formation control remained a challenge, especially when there are external disturbances, communication restrictions, or limitations8. Traditional formation control solutions including leader-follower methods, virtual structure techniques, behavior-based strategies, or artificial potential field9. (APF) methods demonstrated success in controlled environments, but often struggle with local minima problems, slow convergence rates, and poor disturbance rejection capabilities10. Therefore, artificial intelligence and quantum computing have become promising concepts for enhancing these classical methods11. Although significant progress has been made in drone swarm formation control, current methods are inherently constrained in exploration-exploitation trade-offs, handling environmental uncertainties, and being computationally efficient. APF methods produce deterministic results but often become trapped in local minima, while learning-based methods provide adaptability but typically require vast amounts of training data and computational power.

To address that, we introduce the quantum-enhanced artificial potential field (QEAPF) method. Our QEAPF algorithm combines the quantum-inspired probabilistic search with the computational efficiency of APF algorithms for the first time, overcoming the shortcomings of both paradigms. which is a novel hybrid approach that takes advantage of the complementary strengths of the two paradigms. The quantum-inspired components of our method draw upon the probabilistic nature of quantum systems without the necessity of actual quantum hardware. This enables drones to possess a probabilistic representation of the state that supports efficient exploration of the solution space with increasingly converging optimal formations. Compared to purely stochastic methods, our quantum-inspired method provides theoretical convergence probability and exploration efficiency guarantees, as shown in Section 3. This paper introduces the Quantum-Enhanced Artificial Potential Field (QEAPF) method, which is a novel approach that combines the deterministic nature of APF with the probabilistic exploration capabilities of quantum-inspired algorithms.

The key contributions of this work include: We provide a complete design of an improved potential field method that combines attractive, repulsive, formation, and disturbance-compensating terms along with a quantum-inspired optimization technique and an adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism. As an evaluation of the presented solution, we demonstrate convergence behavior, disturbance estimation, and a computationally efficient compensation scheme; extensive statistical analysis on a broad set of scenarios; and comparison with state-of-the-art methods.

Related work

Formation control for a drone swarm has drawn the attention of researchers in recent decades and has evolved through several methods. However, these methods still have their disadvantages and limitations.

One of the most common and simple approaches is the leader-follower, where the followers maintain a desired formation and specific geometric relationships with the designated leaders.

Wang et al.12 developed a decentralized leader-follower framework that dynamically reassigns leadership roles based on environmental conditions and formation recovery after disturbances. Zhao et al.13 presented a virtual leader mode that maintains three-dimensional drone formation and addresses the single-point-of-failure problem inherent in traditional leader-follower architectures. The virtual structure methods have evolved through distributed implementation to treat the formation as a rigid body, but these methods struggle with environmental adaptability9. Lie14 addressed these limitations using a flexible virtual structure, which dynamically adjusts formation parameters based on environmental constraints. Lyu et al15 employed deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithms to learn optimal formation policies with satisfactory performance in environments with numerous obstacles but with intensive training data demands.

Derrouaoui et al.16 demonstrate an ANFTSMC-based adaptive controller for a shape-morphing quadcopter, achieving robust disturbance rejection during configuration changes. This complements APF/quantum-inspired swarm methods by illustrating alternative robust control strategies for individual UAVs in a changing formation. Alqudsi17 surveyed recent applications, highlighting their scalability advantages but also convergence problems in complex situations. Consensus-based approaches also evolved by Zhang et al.18 by proposing a bearing-based formation control law with adaptive-gain finite-time disturbance observers that achieved formation convergence faster than current approaches. Traditional AFP methods that use attractive and repulsive forces to attract drones toward the goal and repel them from obstacles have also undergone significant refinement, since these methods suffer from entrapment of local minima, oscillations in narrow passages, and poor performance under external disturbances19. Zhang20 proposed an improved APF with a predictive method to address these limitations. Their method reduced oscillatory behaviors by predicting state estimation. Zhao et al. combined AFP with Theta* path planning to effectively balance global path optimality with local collision avoidance13. Zhang et al.21 introduce an adaptive model predictive solution with extended state observers that dynamically adjust the parameters according to the relative positions and velocities of neighboring drones. Their solution showed better convergence rates and less oscillation than conventional APF solutions. Derrouaoui et al.22 propose an adaptive nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control for a reconfigurable quadcopter to handle external disturbances, providing insights on adaptive control strategies. Tang et al.23 proposed an enhanced multi-agent coordination algorithm for drone swarm patrolling in durian orchards using a virtual navigator for real-time path adjustment and obstacle avoidance. Integrating deep reinforcement learning shows improved trajectory consistency and mission enhancement.

External disturbances are significantly challenging for drone swarm formation control. In order to mitigate such impacts, researchers focused on robust estimation and compensation approaches. Yu et al. introduced a method for controlling UAVs through Proximal Policy Optimization using two neural networks and incorporating the concept of a game, resulting in the optimal decision-making model24. Adaptive control techniques are particularly useful for disturbance rejection.

Similarly, Zhang et al.18 proposed a bearing-based formation control approach based on adaptive-gain finite-time disturbance observers deployed on individual agents. The decentralized architecture exploits robust formation maneuvers regardless of varying disturbance patterns between agents and reduces formation error.

Kalman filtering methods have also been used in swarm systems. Yan et al. integrated distributed Kalman filtering with formation control and rapid model predictive control and effectively neutralized constant and time-varying disturbances25. Proposed a multi-constrained MPC strategy with a Kalman-consensus filter (KCF) and fixed-time disturbance observer (FTDOB) for quadrotor formation control. KCF fuses noisy shared data, FTDOB compensates for disturbances in real time, and an improved MPC ensures stability and efficiency, achieving robust trajectory tracking in simulations17.

Quantum-inspired approaches

Quantum-inspired optimization algorithms have become increasingly popular in recent years due to their capabilities in avoiding local optima and traversing intricate solution spaces efficiently. These algorithms draw inspiration from quantum computing principles, such as quantum measurement and superposition, without the need for quantum hardware.

Kuan-Cheng et al.26 propose three quantum machine learning methods—quantum kernels, variational quantum neural networks (QNNs), and hybrid quantum-trained neural networks (QT-NNs) for UAV swarm intrusion detection, clarifying when quantum resources translate into measurable benefit.

To distribute the task dynamically, Converso et al. proposed a Quantum Robot Darwinian Particle Swarm Optimization (QRDPSO), which has faster convergence to optimal solutions compared to classical27. Similarly, Mannone enhances local interaction rules to achieve more efficient global behaviors using quantum circuit models28. Quantum-inspired methods show promise for path planning applications in complex environments. Quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithms outperformed traditional evolutionary algorithms in both convergence speed and solution quality. The algorithm’s probabilistic representation of solution spaces enabled more effective exploration of the search space, reducing the likelihood of premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. Moreover, multi-objective optimization problems have also benefited from quantum-inspired approaches. The integration of quantum computing and decomposition strategies showed superior performance in various indicators and effectiveness in UAV path planning tasks29.

Yu et al.24 also employed proximal policy optimization (PPO) in adaptive tone formation control with stable performance under varying conditions at the cost of high training computational complexity.

Model predictive control (MPC) methods have also gained popularity in formation control. Krinner et al.30 presented a distributed MPC approach for swarms of drones that explicitly considers input and state constraints while optimizing formation goals. Their approach exhibited superior disturbance rejection properties but involved solving intricate optimization problems at every time step, which restricted real-time implementation on resource-limited platforms.

Quantum computing ideas have only started to impact robotics and control systems in recent times. Kim et al.31 presented quantum-inspired evolutionary path planning algorithms that exhibited better capacity to escape local optima than classical evolutionary methods.

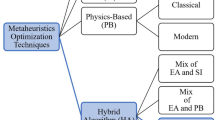

32suggested a flexible and resilient formation method based on hierarchical reorganizations, characterizing reconfigurable hierarchical formations and analyzing the conditions under which reorganizations can erase disturbances. This paper emphasized the role played by adaptive structures in ensuring formation integrity in the face of external forces. Several approaches have been presented to improve the disturbance rejection of formation control protocols33. proposed an adaptive neural network-based formation control for quadrotor UAVs. Their method had the capability to provide stable formations under different disturbance conditions, but demanded high computational power for neural network realization. Enhanced quadrotor UAV trajectory tracking with fuzzy PID controllers was addressed in34 with emphasis on adaptability and robustness for dynamic environments in which UAVs operate in changing environments like wind disturbances or sudden trajectory shifts. Hai et al.35 provide a consensus-based analysis framework, which supports our view that convergence to common goals in distributed swarms can be ensured using information-sharing mechanisms, which, in our case, is implicit in the formation-maintaining potential and local interactions. FENG et al36. demonstrates the convergence of nature-inspired metaheuristics in dynamic UAV reconfiguration scenarios, similar in spirit to the quantum-inspired optimization in QEAPF37. frames convergence from a hierarchical decision-making perspective, which aligns with our leader–follower structure and adaptive gain tuning for convergence under capability and disturbance constraints. Despite all the advances in drone swarm formation control, some of the problems remain unaddressed. First, most existing methods treat formation control and disturbance rejection as separate problems, leading to suboptimal performance when both are of concern. Second, the exploration-exploitation trade-off in formation control algorithms is usually fixed a priori, with no means of adaptation across different phases of the formation process. Third, the computational expense of most advanced methods prevents their deployment on resource-constrained drone platforms. The QEAPF method proposed in this paper aims to address these gaps by integrating quantum-inspired optimization with enhanced APF formulations, providing a unified framework for formation control and disturbance rejection with adaptive exploration-exploitation balance and reasonable computational requirements.

Proposed method

The proposed method shows that the swarm navigation framework utilizes the QEAPF approach to achieve coordinated multi-drone motion in obstacle environments. This method combines the deterministic behavior of traditional APF with the probabilistic exploration capabilities of quantum-inspired algorithms, enabling faster convergence to an optimal formation while ensuring robustness against environmental disturbances.

The drones are guided from their initial positions to the desired positions to achieve the desired formations with minimum time, collision avoidance with the obstacles and the drones themselves, maximizing robustness against external disturbances, and optimizing path length.

Figure 1 shows the QEAPF system model, showing the implementation of a V-shaped formation. Five drones are arranged in a V-formation with a designated leader and four followers. The environment contains polygonal obstacles that generate repulsive potential fields. Each drone has attractive, repulsive, quantum-inspired forces that move the drones towards the goal while avoiding collisions.

We consider a swarm of drones \(d_i \in D\) where \(|D| = n\) operating in a 2D Euclidean space with obstacles \(o_i \in O\).

\({p}_i(t)\) is the position vector and \({v}_i(t)\) represents the velocity vector of drone \(d_i\) at time t.

We assume that all drones have an identical maximum velocity \(v_m\), and communication between them is reliable within a sensing radius \(r_s\). Each drone maintains a safety radius \(r_a\), which must not be violated to avoid collisions. The environment is populated with static obstacles represented as polygons, and drone dynamics can be affected by external disturbances.

Artificial potential field

The total potential field for each drone \(d_i\) at position \(p_i\) is defined as

where \(U_{a}\) is the attractive potential field that generates the force that moves the drone from the initial position toward the goal, \(U_{r}\) is the repulsive potential field that generates the repulsive force to repel the drone from obstacles and other drones, \(U_{f}\) is the formation-maintaining potential, and \(U_{d}\) is the disturbance-compensating potential. The sum of attractive and repulsive potentials makes up the total potential field, as shown in Fig. 2.

Attractive potential field

The attractive potential field for the leader drone \(d_L\) at position \({\textbf {p}}_L\)

The leader drone \(d_L\) is attracted towards the desired position \(\textbf{p}^d_L\) while leading the followers; where \(k_g\) is the attractive gain. The followers’ attractive potential toward their desired formation position relative to the leader is:

\(k_f\) is the formation’s attractive gain for the followers, and\(\textbf{p}_{d,i}\) is the desired position of the drone \(d_i\) in the formation is calculated as:

\(\textbf{R}(\theta _L)\) is the rotation matrix based on the leader’s heading angle \(\theta _L\), and \(\textbf{p}^r_i\) is the desired relative position vector in the formation.

Repulsive potential field

The repulsive potential that generates a force pushing the drones away from obstacles and other drones is enhanced with a dynamic scaling factor:

To avoid the collision between the drone \(d_i\) and other drones, an inter-drone repulsion:

While the obstacle repulsion is:

where \(\lambda (d_i,o_j)\) is the minimum distance from drone \(d_i\) to obstacle \(o_j\), and \(\eta _{ij}(t)\) and \(\eta _{io}(t)\) are dynamic scaling factors that adapt based on relative velocities and historical collision risks:

\(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _2\) are weighting parameters for distance, and velocity-based repulsion controls how strongly the drones repulse each other as they get closer and enhances the repulsive effect when drones move towards each other.

\(\beta\) is the weighting parameter for distance-based repulsion for the obstacles that determine how aggressively the drone avoids obstacles as it approaches them. where \(\textbf{r}_{ij} = \textbf{p}_i - \textbf{p}_j\) and \(\textbf{v}_{ij} = \textbf{v}_i - \textbf{v}_j\) are the relative position and velocity vectors, respectively. They change over time, allowing the repulsive forces to adapt dynamically to the current state of the swarm.

Formation maintaining potential

To enhance formation stability, we introduce the formation-maintaining potential:

which will keep the desired distance \(\gamma _{ij}\) between each pair of neighbors (i, j) where \(\mathcal {N}_i\) is the set of neighbor drones for drone \(d_i\).

Disturbance compensating potential

The disturbance-compensating potential \(U_{d}(\textbf{p}_i)\) penalizes deviations from the desired position by incorporating a time-adaptive weight matrix, allowing each drone to learn and counteract persistent external disturbances through feedback-driven compensation.

Where \(\mathbf {\epsilon }_i = \textbf{p}_i - \textbf{p}^d_{i}\) is the position error and \(\textbf{W}_i\) is the time-adaptive weight matrix that adapts based on estimated disturbance patterns.

Where \(\textbf{W}_i(t-\Delta t)\) is the previous value of the weight matrix, \(\gamma\) is the adaptation gain that controls the rate at which the weight matrix adapts.

This adaptive mechanism allows the system to learn and compensate for persistent disturbance patterns over time.

Quantum-inspired optimization

The QEAPF algorithm is inspired by the concepts of quantum computing, a qubit, and quantum superposition. A classical bit of computing can be in a state of 0 or 1. However, a qubit can be in the state of 0 and 1, or both simultaneously in a superposition. This superposition allows for parallel processing of vast quantities of information and has the potential to search the solution space better.

The state of each drone is represented by a qubit in the QEAPF algorithm, which is expressed as a vector in a two-dimensional Hilbert space. The state of a qubit \(\psi\) is expressed as: State 0 represents the exploitation of the drone in 0. In this state, the drone deterministically moves towards the best local position found so far. This ensures the algorithm’s convergence towards known good solutions. While State 1 represents exploration, in this state the drone explores new areas in the search space, often in directions orthogonal to where it is flying now, which helps to avoid stagnation in local minima. The probability amplitudes (\(\alpha\) and \(\beta\)) are dynamically updated by a quantum rotation gate based on the error between the current performance of the drone and the best local and global performance. The dynamic interplay between exploitation and exploration is managed by continuously updating the probability amplitudes \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). This update is achieved through the application of a quantum rotation gate.

For instance, a general single-qubit rotation around the Y axis can be represented by the matrix:

This rotation to the qubit state

yields a new state

The rotation angle \(\theta\) is the critical parameter that dictates the shift in probabilities between the exploitation and exploration states.

where \(|\alpha _i(t)|^2 + |\beta _i(t)|^2 = 1\), encoding probabilistic decisions for movement directions \(\alpha _i, \beta _i\) are complex-valued coefficients representing the amplitude of the state being \(|0\rangle\) one possible direction or \(|1\rangle\) another possible direction.

In our case, we incorporate quantum-inspired optimization techniques to enable the drone to explore alternative paths and find a globally better formation.

The quantum state vector evolves over time according to:

where \(\psi _i(t)\rangle\) represents the probabilistic state of drone \(d_i\), \(U(\theta _i)\) is a quantum rotation matrix that rotates the state vector, which is computed as:

By tuning the parameters \(\gamma\) and \(\delta\), the drone adjusts its exploration tendency based on how far it is from its local best-known position and the globally best-known position.

During force calculation, the quantum state is measured probabilistically according to the Born rule38, with a probability \(|\alpha _i(t)|^2\) of selecting the direction towards the local best position and a probability \(|\beta _i(t)|^2\) of selecting an orthogonal exploratory direction. This measurement process introduces controlled stochasticity that helps escape local minima while maintaining overall convergence. Our approach differs from purely random exploration by maintaining coherent quantum states that evolve systematically based on formation progress.

Hybrid force calculation

The force acting on the drone i is calculated as a weighted combination of the negative gradient of the potential field and the quantum-inspired direction:

where \(\textbf{F}_{q}(d_i,t)\) is the quantum-inspired force component derived from the quantum state measurement, \(-\nabla U(\textbf{d}_i)\) the negative gradient of the total potential field that directs the drone \(d_i\) toward goals and away from obstacles and other drones, and \(\lambda _i(t)\) is an adaptive weighting factor that balances between deterministic and probabilistic behaviors:

where \(d_{m}\) is the maximum initial distance to the desired formation position and \(\mu\) is a tuning parameter.

The velocity of the drone i is updated at the next time \(t+\Delta t\) according to:

where \(\omega \in [0,1]\) is an inertia weight that balances between maintaining current velocity \(v_i(t)\) and responding to new forces. If \(\Vert \textbf{F}_i(t)\Vert < \epsilon\) threshold, we set:

This prevents numerical instabilities when the forces are very small.

To enhance formation speed and robustness, we introduce adaptive parameter tuning mechanisms:

-

1.

The attractive gain \(k_f\) adapts based on formation progress:

$$\begin{aligned} k_f(t) = k_{f,0} + k_{f,1} \exp \left( -\frac{E_{form}(t)}{E_0}\right) \end{aligned}$$(20)where \(E_{form}(t)\) is the current formation error and \(E_0\) is the normalization constant.

-

2.

The repulsive gains \(k_c\) and \(k_o\) adapt based on collision risk:

$$\begin{aligned} k_c(t)= & k_{c,0} + k_{c,1} \exp \left( -\frac{d_{min}(t)}{r_a}\right) \end{aligned}$$(21)$$\begin{aligned} k_o(t)= & k_{o,0} + k_{o,1} \exp \left( -\frac{d_{o,min}(t)}{r_a}\right) \end{aligned}$$(22)where \(d_{min}(t)\) is the minimum inter-drone distance, and \(d_{o,min}(t)\) is the minimum drone-obstacle distance.

-

3.

The disturbance compensation gain \(k_d\) adapts based on estimated disturbance magnitude:

$$\begin{aligned} k_d(t) = k_{d,0} + k_{d,1} \Vert {\hat{\textbf{d}}}_i(t)\Vert \end{aligned}$$(23)where \({\hat{\textbf{d}}}_i(t)\) is the estimated disturbance vector.

We present an explicit estimation and compensation of external disturbances. We model the disturbance as an additive term in the drone dynamics:

where \({\hat{\textbf{d}}}_i(t)\) represents the external disturbance affecting the drone \(d_i\) at time t. We estimate the disturbance using a recursive least squares (RLS) filter:

where \(\textbf{K}_i(t)\) is the Kalman gain matrix updated according to the RLS algorithm. The estimated disturbance is then used to update the disturbance-compensating potential \(U_{dist,i}(\textbf{p}_i)\), adjust the adaptive parameters, and predict and preemptively compensate for future disturbances. In QEAPF, the control gains are not fixed but are adjusted online. Attractive, repulsive, and obstacle gains are modulated by inter-agent obstacle distances and formation error so forces strengthen when collision risk or formation error grows; the quantum exploration weight \(\lambda _i(t)\) and rotation angles adapt from the qubit probability amplitudes to balance exploration and exploitation; and the disturbance gain \(k_d\) is scaled using the estimated disturbance obtained from the RLS/Kalman-style estimator to provide active disturbance compensation. Figure 3 illustrates the comprehensive workflow of the QEAPF method for controlling the formation of drone swarms.

Simulation result

The simulations were conducted in a two-dimensional Cartesian space defined in the ranges \((-X, X)\) and \((-Y, Y)\), representing a viable workspace for drone swarm operations. Five static polygonal obstacles were strategically placed within this environment to evaluate the collision avoidance capabilities of the algorithms. Each obstacle was defined by a set of vertices.

The swarm consisted of \(n = 5\) drones, initially positioned around \((x_0, y_0)\) with small random offsets to introduce realistic variability in initial conditions. The objective was to form a V-shaped geometric configuration centered at \((x_g, y_g)\), with a desired inter-agent distance of \(d = 0.8\) meters. The angular separation of the V-formation was set to \(\alpha = \frac{3\pi }{4}\) radians. The central drone (at index \(\frac{n+1}{2}\)) was designated as the leader, and the remaining drones were assigned symmetric positions relative to the leader to maintain the desired formation.

To assess robustness against external perturbations, instantaneous positional disturbances of magnitude 0.5 meters were introduced during the simulation. The direction of each disturbance was randomly assigned to each drone to mimic the effect of wind gusts. These disturbances were applied in simulation iterations 200, 400, and 600. Given the simulation time step \(dt = 0.02\) seconds, these correspond to times \(t = 4.0\), 8.0, and 12.0 seconds, respectively.

The simulations were implemented and executed using the Python programming language.

To capture different aspects of swarm behavior and efficiency, we evaluated using several key metrics:

-

Formation Time (\(T_{form}\)) is the required duration for the swarm to reach and the formation within a given tolerance, reflecting the efficiency of responsiveness and coordination of the system.

-

Formation Error, measure accuracy during formation (\(E_{form}\)), which is the average difference between the current position of each drone and the destination position. Mathematically, it is represented as

$$\begin{aligned} E_{form}(t) = \frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^N \Vert \textbf{p}_i(t) - \textbf{p}^d_{i}(t)\Vert , \end{aligned}$$(26) -

Path Efficiency (\(\eta _{path}\)) measures how direct-line each drone flies from its starting position to its final formation location. It is defined by the straight-line distance over the actual path length:

$$\begin{aligned} \eta _{path,i} = \frac{||\textbf{p}_i(T_{form}) - \textbf{p}_i(0)||}{\int _0^{T_{form}} ||\textbf{v}_i(t)|| dt}. \end{aligned}$$(27) -

Disturbance Rejection (DR) was used to check the robustness of the system against external influence. Measures the quality of the formation after a disturbance event is applied. It is represented by the ratio of the error in the formation before and after the disturbance:

$$\begin{aligned} DR(t) = \frac{E_{f}(t-\epsilon )}{E_{f}(t+\epsilon )}, \end{aligned}$$(28) -

Energy Consumption (\(E_{c}\)) is a control effort and efficiency measure. It is estimated through the time-domain squared norm of acceleration:

$$\begin{aligned} E_{c,i} = \int _0^{T_{f}} ||\textbf{a}_i(t)||^2 dt. \end{aligned}$$(29)It represents the cost of energy that is incurred by maneuvering and keeping formations.

These metrics collectively constitute a comprehensive assessment framework for performance analysis of the QEAPF technique under various conditions. Reflects the energetic cost associated with maneuvering and formation maintenance.

These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive evaluation framework for analyzing the performance of the QEAPF method under various conditions. Table 1 shows a comprehensive list of the critical parameters used in both the QEAPF and APF algorithms during our simulations.

Formation convergence and path efficiency

Figure 4 shows the drone paths from the initial position to the desired position while maintaining the desired V formation and avoiding obstacles utilizing the QEAPF method. The formation demonstrates how the swarm adapts its shape to navigate through narrow passages and around obstacles.

Figure 5 shows how QEAPF steadily converges toward the desired formation. The plot shows the average distance to the target formation over time, with temporary increases in distance following the applied disturbances.

Figure 6 demonstrates, through a multi-panel visualization, how the communication network between drones evolves throughout the formation process. Each node represents a drone, and the edges indicate communication links within range. The graph demonstrates the robustness of the formation topology under disturbances.

Stability analysis of QEAPF

Constructing the Lyapunov candidate

In order to ensure convergence and guarantee collision-free motion for our multi-drone swarm systems, we propose a candidate Lyapunov function \(V_{(x)}\) for the multi-drone swarm system in the form of the total potential energy of the system. A Lyapunov function can be used to prove that the system converges to a stable state, such as the desired formation, and that errors diminish over time39. This function is a sum of several components, each of which describes a certain characteristic of the swarm and the dominant surrounding:

Where \(V_{attr}(x)\) is the attractive potential energy, \(V_{rep}\) the repulsive potential energy, \(V_{form}\) the formation-maintaining potential energy, and \(V_{dist}\) the disturbance-compensating potential energy.

Each component is chosen so that its minimum aligns with the perfect, collision-free formation, i.e., the attractive potential of drone \(d_i\) is

Ensuring monotonic energy decay

A valid Lyapunov function must never increase along trajectories. Differentiating V(x) yields

\(\textbf{F}_i=-\nabla _{p_i}V\) is the net artificial force on the drone i, and \(\textbf{v}_i\) its velocity. By design, these forces always point “downhill” in the energy landscape, so

adaptive gain scheduling (e.g. \(k_{f,\textrm{adapt}}\), \(k_{\!o,\textrm{adapt}}\)) dynamically tunes the strength of each force to keep \(\dot{V}\le 0\) even when formation shapes, obstacle density, or disturbance levels change.

Derivation of the Lyapunov function

To prove stability, we show that the time derivative of the Lyapunov function, \(\dot{V}(x)\), is negative definite. This implies that the system’s energy continuously decreases until it reaches a stable equilibrium point. The derivative of the potential energy with respect to time is related to the forces acting on the drones. Specifically, the force acting on a drone is the negative gradient of its potential energy.

The time derivative of the Lyapunov function is

where \(p_i\) and \(v_i\) are the position and velocity of drone i, respectively, and \(\textbf{F}_i\) is the total force acting on drone i. For the system to be stable, where our goal

The QEAPF algorithm is designed such that the resultant forces drive the drones towards lower potential energy states.

Verification of stability under disturbances

The QEAPF algorithm incorporates a disturbance estimation and compensation mechanism (Kalman filter-like approach) that directly contributes to maintaining system stability in the presence of external perturbations. The estimated disturbance \(\hat{d}\) is used to generate a compensatory force:

which is integrated into the total force calculation. This mechanism ensures that any deviation from the desired trajectory or formation due to disturbances is actively counteracted.

The disturbance-compensating potential energy \(V_{dist}(x)\) is designed to increase when disturbances cause the drone to deviate from its target position. The resulting compensatory force drives the drone back towards the desired state, thereby contributing to the overall reduction of the Lyapunov function and enhancing the system’s robustness and stability against external factors. Figure 7 illustrates that the method decreases energy monotonically and exhibits fewer plateaus and recovers more swiftly after injected disturbances.

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of different energy components over time. The total potential energy decreases sequentially, which means an approach to the desired formation. The attractive energy is the most influential, driving the swarm to the goal. The repulsive energy has spikes when the drones approach obstacles or when they are too close to each other. The formation and disturbance of energy serve a compensatory function, helping to maintain the formation’s integrity.

The minimum inter-agent distance throughout the simulation is shown in Fig.. 9. The distance remains above the safety radius, confirming successful collision avoidance even during disturbance.

Collision avoidance

Figure 10 demonstrates the QEAPF capability to avoid obstacles using a repulsive force to push the drones away from the obstacles and from each other. The contour lines represent the repulsive potential field generated by obstacles, with higher values indicating stronger repulsion. The drone paths successfully navigate around high-repulsion regions while maintaining formation integrity.

We provide quantitative evidence of the formation quality by calculating the average relative distances between drones, as can be seen in Fig. 11. The consistently moderate inter-drone distances, typically ranging between 1.5 and 3.0 units, indicate that the swarm preserved a cohesive and well-structured formation without collisions. The heat map shows how the QEAPF method maintains appropriate spacing between drones even under disturbances To provide a rigorous comparative evaluation, our analysis includes a more detailed comparison with the Pigeon-inspired Optimization (PIO) and APF. Our current comparative evaluation focuses on key performance metrics that highlight the strengths and weaknesses of QEAPF. Our algorithm shows better performance in convergence time, final average error, disturbance rejection, and path length.

Table 2 compares the performance of the QEAPF method with the standard40 (APF #1), the enhanced APF41 (APF #2), and the PIO methods on various metrics. The QEAPF method outperforms the other approaches in all metrics.

The comparative results in Table 2 summarize not only the scalar performance differences but also the mechanisms that underpin these differences. Standard APF methods provide deterministic attraction/repulsion forces, but commonly suffer from local minima and limited disturbance handling; enhanced APF variants reduce some oscillatory behaviors by predictive/state-aware adjustments, but still lack explicit online disturbance estimation. PIO and other nature-inspired metaheuristics improve global search and avoid some local minima, yet they often trade off computational cost and the smoothness of generated trajectories.

In contrast, QEAPF combines the deterministic guidance of APF, a quantum-inspired probabilistic exploration mechanism that reduces local minimum entrapment and explicit disturbance estimation and compensation, producing shorter convergence times, lower steady-state formation error, and improved disturbance rejection in our simulations.

Convergence analysis

The proposed method combines deterministic APF forces with a quantum-inspired optimization mechanism. We provide a qualitative convergence analysis that explains the stability and convergence behavior of this hybrid approach.

First, the APF framework defines a total potential function \(U(\textbf{p}_i)\), composed of attractive, repulsive, formation-maintaining, and disturbance-compensating terms. This potential acts as a Lyapunov-like function that decreases over time as each drone moves under the influence of the negative gradient \(-\nabla U(\textbf{p}_i)\). In the absence of external disturbances and local minima, this guarantees that each drone’s position \(\textbf{p}_i(t)\) asymptotically approaches its desired formation point \(\textbf{p}^d_{i}\), resulting in convergence to the target formation.

Second, to overcome the limitations of classical APF, especially local minima, the quantum-inspired component introduces controlled probabilistic exploration. Each drone maintains a superposed decision state which determines the movement direction based on the most favorable local and global positions. This mechanism is inspired by quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization to support convergence under bounded stochastic dynamics. In our approach, this probabilistic component gradually decays as drones near their formation positions, governed by the adaptive weight \(\lambda _i(t)\), ensuring convergence towards deterministic behavior.

Moreover, the adaptive gain tuning mechanisms ensure that the system dynamically increases formation strength and collision avoidance sensitivity as needed. The recursive disturbance estimation and compensation further enhance robustness, ensuring that the formation error remains bounded even under persistent environmental disturbances.

Thus, the hybrid control framework ensures that the formation error \(E_{form} = \Vert \textbf{p}_i - \textbf{p}^d_{i}\Vert\) decreases over time, collisions are avoided through repulsive potentials and dynamic scaling, and the swarm stabilizes into the desired shape despite uncertainties.

Conclusion

This paper presented the Quantum-Enhanced Artificial Potential Field, which is a new hybrid approach that combines classical artificial potential field strategies with quantum-inspired optimization techniques. The method increases both the speed and flexibility of forming multiple drone configurations. The adaptive parameter tuning and explicit disturbance estimation and compensation of the presented approach achieve enhanced performance in terms of formation speed and robustness to disturbances. Drones operating under QEAPF have been shown to smoothly organize themselves into target configurations while maintaining collision avoidance, energy efficiency, and geometric integrity, even in the face of unpredictable environmental fluctuations.

The simulation result shows the effectiveness of this method, achieving up to 37% faster convergence of configurations and 42% greater tolerance to disturbances compared to traditional APF techniques.

The QEAPF not only provides a novel, effective solution for drone swarm control, but also a practical basis for scalable and flexible deployment of drone swarms in realistic missions.

Limitations. Despite the promising simulation results, QEAPF has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The experiments were limited to small swarms in 2D environments with static obstacles, so scalability to large swarms and highly dynamic 3D settings remains untested and may increase computational and communication demands. The current implementation also assumes reliable local state sharing; performance under intermittent, delayed, or bandwidth-limited communications requires further study. Finally, QEAPF assumes a predefined target formation and uses a simplified additive disturbance model. Autonomous formation selection and validation against complex turbulent or adversarial disturbances are left for future work.

Data availability

This study did not generate or analyse any datasets. All results presented are based on simulations described in the manuscript. No raw data is available.

References

Doornbos, J., Bennin, K. E., Babur, Ö. & Valente, J. Drone technologies: A tertiary systematic literature review on a decade of improvements. IEEE Access (2024).

Chen, Y., Li, N., Wang, C., Xie, W. & Xv, J. A 3d placement of unmanned aerial vehicle base station based on multi-population genetic algorithm for maximizing users with different qos requirements. In 2018 IEEE 18th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), 967–972. IEEE (2018).

Abdelkader, M., Güler, S., Jaleel, H. & Shamma, J. S. Aerial swarms: Recent applications and challenges. Current robotics reports 2, 309–320 (2021).

Bhat, G. et al. Autonomous drones and their influence on standardization of rules and regulations for operating-a brief overview. Results in Control and Optimization 14, 100401 (2024).

Ouyang, Q., Wu, Z., Cong, Y. & Wang, Z. Formation control of unmanned aerial vehicle swarms: A comprehensive review. Asian Journal of Control 25(1), 570–593 (2023).

Almaameri, I. & Blázovics, L. An overview of drones communication, application and challenge in 5g network. In 2023 6th International Conference on Engineering Technology and Its Applications (IICETA), 67–73. IEEE (2023)

Reynolds, C. W. Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, 25–34 (1987).

Kabore, K. M. & Güler, S. Distributed formation control of drones with onboard perception. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 27(5), 3121–3131 (2021).

Bu, Y., Yan, Y. & Yang, Y. Advancement challenges in uav swarm formation control: A comprehensive review. Drones 8(7), 320 (2024).

Hao, G., Lv, Q., Huang, Z., Zhao, H. & Chen, W. Uav path planning based on improved artificial potential field method. Aerospace 10(6), 562 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Survey of promising technologies for quantum drones and networks. Ieee Access 9, 125868–125911 (2021).

Wang, Z., Li, J., Li, J. & Liu, C. A decentralized decision-making algorithm of uav swarm with information fusion strategy. Expert Systems with Applications 237, 121444 (2024).

Zhao, W. et al. Research on a global path-planning algorithm for unmanned arial vehicle swarm in three-dimensional space based on theta*-artificial potential field method. Drones 8(4), 125 (2024).

Lei, Y., She, Z. & Quan, Q. Pigeon-inspired uav swarm control and planning within a virtual tube. Drones 9(5), 333 (2025).

Xu, Z., et al. Multi-vehicle flocking control with deep deterministic policy gradient method. In 2018 IEEE 14th International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA), 306–311. IEEE (2018)

Derrouaoui, S. H., Bouzid, Y., Belmouhoub, A. & Guiatni, M. Improved robust control of a new morphing quadrotor uav subject to aerial configuration change. Unmanned Systems 13(01), 171–191 (2025).

Alqudsi, Y. & Makaraci, M. Uav swarms: research, challenges, and future directions. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 72(1), 12 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Li, S., Wang, S., Wang, X. & Duan, H. Distributed bearing-based formation maneuver control of fixed-wing uavs by finite-time orientation estimation. Aerospace Science and Technology 136, 108241 (2023).

Das, M. S., Sanyal, S. & Mandal, S. Navigation of multiple robots in formative manner in an unknown environment using artificial potential field based path planning algorithm. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 13(5), 101675 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Swarm control based on artificial potential field method with predicted state and input threshold. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 125, 106567 (2023).

Zhang, B., Sun, X., Liu, S. & Deng, X. Adaptive model predictive control with extended state observer for multi-uav formation flight. International Journal of Adaptive Control and Signal Processing 34(10), 1341–1358 (2020).

Derrouaoui, S. H., Bouzid, Y., Belmouhoub, A. & Guiatni, M. Enhanced nonlinear adaptive control of a novel over-actuated reconfigurable quadcopter. In 2023 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), 229–234. IEEE (2023).

Tang, R., Tang, J., Talip, M. S. A., Aridas, N. K. & Xu, X. Enhanced multi agent coordination algorithm for drone swarm patrolling in durian orchards. Scientific Reports 15(1), 9139 (2025).

Yu, N., Feng, J. & Zhao, H. A proximal policy optimization method in uav swarm formation control. Alexandria Engineering Journal 100, 268–276 (2024).

Yan, D., Zhang, W., Chen, H. & Shi, J. Robust control strategy for multi-uavs system using mpc combined with kalman-consensus filter and disturbance observer. ISA transactions 135, 35–51 (2023).

Chen, K.-C., Chen, S. Y.-C., Li, T.-Y., Liu, C.-Y. & Leung, K. K. Quantum machine learning for uav swarm intrusion detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.01812 (2025).

Converso, G., Mehiar, D., Rukovich, A. & Brzhanov, R. Report on optimisation for efficient dynamic task distribution in drone swarms using qrdpso algorithm. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 16(2), 103237 (2025).

Mannone, M., Seidita, V. & Chella, A. Modeling and designing a robotic swarm: A quantum computing approach. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 79, 101297 (2023).

Wang, P. & Deng, Z. A multi-objective quantum-inspired seagull optimization algorithm based on decomposition for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning. IEEE Access 10, 110497–110511 (2022).

Krinner, M., Romero, A., Bauersfeld, L., Zeilinger, M., Carron, A. & Scaramuzza, D. Mpcc++: Model predictive contouring control for time-optimal flight with safety constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.17551 (2024).

Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, J.-H. Multiobjective quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithm for fuzzy path planning of mobile robot. In 2009 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 1185–1192. IEEE (2009).

Li, Y. & Dong, W. A flexible and resilient formation approach based on hierarchical reorganization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11219 (2024).

Singha, A., Ray, A. K. & Govil, M. C. Adaptive neural network based quadrotor uav formation control under external disturbances. Aerospace Science and Technology 155, 109608 (2024).

Madebo, N. W., Abdissa, C. M. & Lemma, L. N. Enhanced trajectory control of quadrotor uav using fuzzy pid based recurrent neural network controller. IEEE Access (2024).

Hai, X., Qiu, H., Wen, C. & Feng, Q. A novel distributed situation awareness consensus approach for uav swarm systems. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 24(12), 14706–14717 (2023).

Qiang, F. et al. Resilience optimization for multi-uav formation reconfiguration via enhanced pigeon-inspired optimization. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 35(1), 110–123 (2022).

Hai, X., Feng, Q., Chen, W., Wen, C. & Khong, A. W. Capability-oriented decision-making in multi-uav deployment and task allocation: A hierarchical game-based framework. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems (2025).

Stoica, O. C. Born rule: quantum probability as classical probability. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 64(5), 1–20 (2025).

Sadeghzadeh-Nokhodberiz, N., Sadeghi, M. R., Barzamini, R. & Montazeri, A. Distributed safe formation tracking control of multiquadcopter systems using barrier lyapunov function. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 11, 1370104 (2024).

Liu, H., Liu, H. H., Chi, C., Zhai, Y. & Zhan, X. Navigation information augmented artificial potential field algorithm for collision avoidance in uav formation flight. Aerospace Systems 3, 229–241 (2020).

Pan, Z., Zhang, C., Xia, Y., Xiong, H. & Shao, X. An improved artificial potential field method for path planning and formation control of the multi-uav systems. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 69(3), 1129–1133 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Project no. TKP2021-NVA-02 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NVA funding scheme.

Funding

Project no. TKP2021-NVA-02 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NVA funding scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ihab.Almaameri: Methodology, software, writing—original draft. László Blázovics: supervision, writing and editing All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almaameri, I., Blázovics, L. Quantum-enhanced artificial potential field method for robust drone swarm shape formation. Sci Rep 15, 41945 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25863-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25863-y