Abstract

Additive Manufacturing (AM) techniques, especially Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM), have generated much interest recently for their capabilities for manufacturing complex geometries using a variety of materials. In this work, a regression model has been developed for the FDM process performance enhancement and to control PETG processing. This study systematically analysed the effect of critical FDM parameters on key performance criteria such as printing time, dimensional deviation, and surface finish, including nozzle temperature, printing speed, and infill density. Experiments were carried out following a defined design of experiments to gather data which were then used to develop regression models for the prediction of printing results. A statistical treatment was done on the relationships among process variables with its impact on performance metrics. The predictive model developed showed a high level of accuracy, thus allowing for the identification of optimal levels for parameter settings conducive to PETG component efficiency, surface quality, and dimensional accuracy. Thus, the study acts as a practical guide for manufacturers willing to upgrade their additive manufacturing processes relating to process optimization, quality control, and production planning. By tying experimental inquiry with predictive modeling, this work delves deep into the dynamics of the FDM process and provides valuable insights for the mass use of PETG-based FDM in automotive, aerospace, biomedical, and other industry sectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

3D printing is an Additive Manufacturing (AM) method which uses the 3-dimensional model data for creating a wider range of shapes and complicated designs. The technology consists of continuous deposition of numerous layers of material, which are stacked on top of one another. ‘AM’ exhibits attraction in various applications such as building, prototypes and biomechanics. Even though ‘AM’ has numerous benefits such as reduced waste, design versatility and automation, the implementation of these concepts is considerably slow and limited. Continuous improvements in materials and ‘AM’ methods are consistently contributing to the development of innovative applications. The augmented approachability of this production method can most probably enable the manufacturers to develop and form an innovative 3D printing equipment.

Architects and designers have mostly utilized 3D printing to create visually pleasing and practical prototypes, capitalizing on its cost-efficient and effective prototyping capabilities. 3D printing has decreased the additional expenses linked to product development. In recent years, there has been a substantial rise in the use of 3D printing in several industries, including both prototype development and the manufacturing of finished goods. Manufacturers encountered difficulties in customizing products for clients due to the exorbitant expenses associated with developing personalized items. However, Additive Manufacturing may utilize 3D printing technology to produce limited quantities of customized products at a very affordable price. This is particularly beneficial in the field of biomedicine, where there is always a need for distinct goods customized for each patient. ASTM standard classification of the additive manufacturing (AM) processes is orderly into seven main types; namely, binder jetting (BJT), directed energy deposition (DED), material extrusion (MEX), material jetting (MJT), powder bed fusion (PBF), sheet lamination (SHL), and vat photopolymerization (VPP)1,2,3,4,5,6,7.

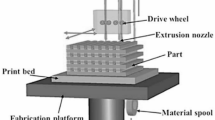

Schematic of FDM12.

The Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) method utilizes a filament composed of thermoplastic polymer to fabricate parts layer by layer during the 3D printing process, as shown in Fig. 1. The filament is heated at the nozzle until it reaches a semi-liquid state, after which it is extruded onto the build platform or on top of previously deposited layers. The thermoplastic nature of the filament is critical, as it enables successive layers to fuse together during printing and solidify at room temperature upon completion. The mechanical properties of FDM-printed components are primarily influenced by factors such as layer thickness, filament width, alignment, and the presence of air gaps within or between layers8. Inter-layer distortion has been identified as a primary cause of mechanical brittleness in printed components.

FDM offers several advantages, including affordability, rapid prototyping capability, and ease of use. However, it also has limitations such as reduced mechanical performance, occasional defects in printed parts, and a restricted range of usable thermoplastic materials9. The incorporation of fiber-reinforced composites in FDM has improved the properties of printed components. Key challenges in composite printing include ensuring proper fiber alignment, achieving strong fiber-matrix bonding, and avoiding void formation10,11,12. FDM-produced components find applications across industries such as automotive, aerospace, medical, electronics, and consumer goods. Nevertheless, the broader industrial use of FDM parts is often constrained by suboptimal mechanical performance.

Optimizing build parameters is crucial to achieving desired mechanical performance. Careful selection of nozzle temperature, printing speed, and infill density significantly influences the properties of the printed part13. Numerous studies have explored correlations between FDM parameters and output characteristics to enhance performance. Among optimization approaches, the Taguchi technique is highly effective for improving FDM process variables and quality. Design of Experiments (DoE) is fundamental in AM for systematically studying parameter effects, modeling nonlinear relationships, and identifying optimal settings. Taguchi Orthogonal Array (OA) methodology reduces experimental effort while maintaining statistical validity and is particularly valuable for multi-response optimization, where multiple quality characteristics must be improved simultaneously14,15,16,17,18,19.

Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) exhibits a wide range of favorable mechanical properties, including high tensile strength and moderate flexural characteristics, making it suitable for various technical and biomedical applications. Compared to other thermoplastic polymers of similar nature, PETG demonstrates improved flexibility, durability, and heat resistance relative to polylactic acid (PLA)20,21,22. Common thermoplastic materials used in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM), such as polycarbonate (PC), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and PLA, are often selected due to their comparatively lower melting points. However, PETG enables effective processing while maintaining structural stability, making it compatible with FDM as well as thermoforming and extrusion processes. This material is widely applied in manufacturing bottles, containers, packaging materials, and medical implants due to its superior malleability, long-term durability, chemical resistance, low moisture absorption, non-slippery surface, recyclability, and overall sustainability23,24,25,26.

Multiple regression analysis is a commonly employed statistical technique for modeling the relationship between process input variables and performance metrics. In the context of FDM, regression analysis is used to optimize process parameters and enhance part quality and efficiency. This approach effectively predicts outcomes, identifies optimal parameter settings, and strengthens the understanding of the FDM process, enabling manufacturers to produce high-quality PETG components with improved surface finish, dimensional accuracy, and overall performance27,28,29.

Based on the earlier literature shows that various intelligence methods have been adopted for optimizing and model FDM process to enhance the quality of component. Various approaches were adopted predominantly to improve the quality of the surface and accuracy in dimension during the FDM process. There is a lack of exploration done on improving the mechanical behaviour of printed parts and regression modelling for printing variables. The inspiration of this exploration is to enhance the performance metrics by considering independent variables infill density, nozzle temperature and printing speed. Printing time, surface quality and dimensional deviation are opted as performance metrics. An explorative study has been undertaken to create a Taguchi grey-based regression model which can foretell the desired performance measures accurately.

Materials and methods

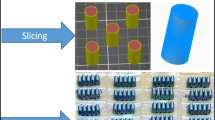

The Snapmaker 2.0 is a multipurpose and flexible device intended predominantly to meet the various desires of engineering uses. The Snapmaker 2.0 uses the Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) technique as its main mechanism for 3D printing. This technique permits consumers to make objects by consecutively placing layers of thermoplastic materials. Polyethene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) is a type of polyester thermoplastic which is derived from Polyethene Terephthalate (PET). It is commonly engaged in profitable applications, including the making of bottles, containers, packing materials, and medical implants. PETG has exceptional characteristics like exceptional ductility, durability, chemical resistance, and a lower temperature requirement for making the desired parts. Accordingly, it is most appropriate for use in various engineering applications such as FDM. The foremost features of this material are its capability to sustain temperature fluctuations, lower moisture absorption, a non-slippery surface, reusability, and sustainability. These features make this material appropriate for structural and architectural plans situated in interior situations. PETG is a multipurpose material that is compatible for use in the industry, necessitating just modest printing requirements. Figure 2 portrays the configuration engaged for FDM and parts printed.

The parameters selected in this work-infill density, nozzle temperature, and printing speed-indeed have a significant impact on part quality and performance in FDM when the application medium is PETG. Such previous studies provide evidence that it is the nozzle temperature at which flow melt occurs, adhesion between layers, and surface quality, with poor combination causing under-extrusion or thermal degradation of the filament. Infill density impacts directly structural integrity, part weight, and consequently, print time-where higher infill densities resulted in increased mechanical strength increases in material consumption and cycle time. Further, printing speed critically affects the deposition uniformity, thermal gradients, and dimensional accuracy, whereas slower print speeds promote better layer bonding at the expense of increased process time, with high print speeds risking low-quality surface fusion and surface irregularities. The levels chosen for each parameter from literature and filament datasheets include the lower, medium, and upper possible ranges; thus, providing a practical operating window within which these parameters would be operated. This allows a systematic evaluation of the parameters on their individual and interactive effect on multiple responses for complete optimization through the Taguchi-Grey approach.

The Taguchi Design of Experiments (DOE) approach is a highly effective approach that effectively enhances the designs of both products and processes. The Taguchi Decision-making process systematically manipulates the input elements at various levels to analyze the effect of these factors on the output response. The main objective is to determine the most effective combination of input elements that will reduce variability and improve performance, while also taking into account the potential influence of noise components on the process. The present investigation examines nozzle temperature, infill density, and printing speed as distinct process variables. The examined output parameters include the surface roughness, dimensional deviation, and printing duration. Table 1 depicts the experimental trials with input variables and attained Grey Relational Grade (GRG). The choice has been taken to utilize an L27 orthogonal array for carrying out the experiments, considering the specific factors and levels involved. In compliance with the L27 orthogonal array, experimental testing was performed on three identical specimens for each of the conditions set. The values being tested for every response variable were taken to be averaged out of the three readings for greater data consistency and reliability.

Development of multiple regression model

The multiple regression technique is employed to ascertain the correlation between the process factors. Regression equations comprise several models, including linear, quadratic, interaction, and full models. These models are characterised by Eqs. (1–4) while considering three independent variables.

Linear equation:

Quadratic equation:

Interaction equation:

Second order equation (Full model):

Where ‘y’ is criterion variable and ‘X1’, ‘X2’ and ‘X3’ are predictor variables.

‘β1’, ‘β2’, ‘β3’…… ‘βn’ are regression coefficients.

The correlation amongst the independent variables and the performance metrics is ascertained by multiple regression analysis. Regression equations are adopted to envisage performance metrics in the FDM method. Regression equations are made applying three independent factors to envisage the essential performance measures and asses the prognostic accurateness of the evolved models.

Result and discussion

An L27 orthogonal array (OA) has been to perform the experiments, pointing to explore the influence of various independent factors on the experimentation setup for FDM of PETG parts. The exploration was predominantly inspired by the aspiration to comprehend the influence of these variables on the making of PETG parts. The preliminary inspiration of this study was to ascertain the supreme settings for these variables to improve the usefulness of the FDM approach. Enhanced precision in metrics such as Surface Roughness (SR), Printing Time (PT), and Dimensional Deviation (DD) designates grander performance.

Optimization of factors on printing time (PT)

The PETG material was exposed to FDM process, and Fig. 3 exhibits the response plot for the Printing Time (PT). The offered figure demonstrates a favorable correlation between Printing Time (PT), Nozzle Temperature (NT), and Printing Speed (PS). Infill Density (ID) is a crucial component that influences PT. To decrease printing time when the nozzle tip size increases, one can increase the discharge of material from the nozzle tip by widening the NT ranges.

To enhance the effectiveness of PT, it is advisable to utilize the A3B1C3 configuration of process variables. The study results presented by Taguchi, as illustrated in Table 2, highlight this tendency. In order to enhance performance, it is possible to adjust the parameters “Nozzle Temperature (ºC)” to 230 °C, “Infill Density (%)” to 25%, and “Printing Speed” to 40 mm/s as depicted in Table 2. The most important variable is “Infill Density”, followed by “Nozzle Temperature” and “Printing Speed”.

Optimization of factors on SR

Figure 4 illustrates the graph displaying the variation in Surface Roughness (SR) of the PETG material when exposed to the FDM technique. The given figure illustrates a negative association between the Surface Roughness (SR) and both the Nozzle Temperature (NT) and Infill Density (ID). The variable denoted as Printing Speed (PS) exerts a substantial impact on SR. Increasing the ‘ID’ ranges can reduce the surface roughness (SR) of the printed object by adding more material, resulting in a higher number of surface flaws.

In order to optimize ‘SR’, it is recommended to employ the A3B1C1 arrangement of process variables. Taguchi’s research findings, as demonstrated in Table 3, exemplify this inclination. To optimize performance, one can alter the parameters “Nozzle Temperature (ºC)” (230 °C), “Infill Density (%)” (25%), and “Printing Speed” (20 mm/s) as depicted in Table 3. The variable of utmost significance is “Infill Density”, with “Nozzle Temperature” and “Printing Speed” following closely after.

Optimization of factors on dimensional deviation

The analysis of the response to dimensional deviation for FDM of PETG components is depicted in the graph displayed in Fig. 5. It is acknowledged that an increase in ‘NT’ and ‘PS’ values are linked to a decrease in the amount of deviation where as an increase in the value of infill density results in an increasing values. Increasing the temperature of the nozzle while maintaining a high printing speed can lead to more pronounced problems related to excessive material deposition and reduced accuracy, as it becomes more challenging to precisely regulate the flow of material. Using a high infill density and a higher nozzle temperature might result in elevated internal tensions and possible warping, which can negatively affect the dimensional accuracy. Increased velocity combined with a higher infill density might worsen problems associated with vibrations and thermal expansion, resulting in less precise prints.

In order to optimize ‘DD’, it is recommended to employ the A3B1C3 arrangement of process variables. Taguchi’s research findings, as demonstrated in Table 4, exemplify this inclination. To optimize performance, one can alter the parameters “Nozzle Temperature (ºC)” (230 °C), “Infill Density (%)” (25%), and “Printing Speed” (40 mm/s) as depicted in Table 4. The variable of utmost significance is “Infill Density”, with “Nozzle Temperature” and “Printing Speed” following closely after.

Contour analysis for chosen performance metrics

A contour plot is a graphical depiction of three variables on a two-dimensional plot. Using 2D graphical illustration can be beneficial for demonstrating the interaction between two factors and their impact on desired performance measurements.

Contour analysis for printing time and dimensional deviation

Figure 6(a) shows the contour plots for printing time against temperature of the nozzle and infill density which are deemed in this present exploration. It is obvious from the illustration that the minimized printing time is attained during the combinations of minimum ‘ID’ and maximum nozzle temperature. This shows that maximized thermal energy, delivered via increased temperature of the nozzle in conjunction with decreased material deposition, makes the printing process by decreasing reducing layer deposition time and material handling. Similarly the combinations of higher levels of printing speed and nozzle temperature produces the parts with minimum time as depicted in Fig. 6(b). It is obvious that increasing printing speeds while paring with increased temperatures, predominantly reduces the overall printing time. This increase in speed reduces the duration of layer deposition when increased nozzle temperature assures efficient material flow and adhesion, optimizing the thermal and mechanical dynamics of the FDM process. Also, the amalgamations of lower levels of infill density and higher levels of printing speed produces the components with minimized printing time as illustrated in Fig. 6(c). The lower ‘ID’ needs fewer passes of the nozzle when the increased speed furthermore improves the rate of deposition collectively leading to reduced printing time.

Figure 6(d) shows the contour plots for dimensional variation against temperature of the nozzle and infill density which are deemed in this present exploration. It is obvious from the illustration that the minimized deviation is attained during the combinations of minimum infill density and maximum nozzle temperature. This proposes that the higher nozzle temperature enhances the material flow and bonding, ensuring improved accuracy in dimension while lower ‘ID’ minimizes the buildup of material reducing thermal distortion and shrinkage. Similarly the combinations of higher levels of printing speed and nozzle temperature produces the parts with decreased deviation in dimension as depicted in Fig. 6(e). It shows that the increased printing speed along with increased nozzle temperatures consequences to decreased deviations in dimension. The combined effect of maximum speed and optimal thermal input ensures consistent material deposition decreasing warping and dimensional inaccuracies. Also, the amalgamations of lower levels of infill density and higher levels of printing speed produces the components with minimized dimensional deviation as illustrated in Fig. 6(f). Lower ‘ID’ and higher printing speed consequences in reduced dimensional deviation. Lower ‘ID’ decreases the thermal mass and internal stresses, when higher printing speed reduces the time spent per layer, decreasing the likelihood dimensional deviation because of prolonged heat exposure.

Contour analysis for surface roughness and GRG

Figure 7(a) shows the contour plots for surface roughness against temperature of the nozzle and infill density which are deemed in this present exploration. It is obvious from the illustration that the higher values of infill density and nozzle temperature produces parts with minimized roughness. It proposes that increased ‘ID” consequences to better material compaction and surface uniformity, when higher nozzle temperature improves flow of the material and layer adhesion, contributing to a smoother surface finish.

Similarly the combinations of lower levels of printing speed and higher levels of nozzle temperature produces the parts with better surface finish as depicted in Fig. 7(b). Reducing printing speed let more duration to each layer for bonding effectively while the improved nozzle temperature ensures better flow and layer cohesion decreasing surface imperfections such as ridges or gaps. Also, the amalgamations of higher levels of infill density and printing speed produces the components with minimized roughness as illustrated in Fig. 7(c). An increased ‘ID’ consequences in denser internal structure decreasing surface irregularities. Similarly, improved printing speed maintain a consistent deposition rate, preventing defects caused by prolonged exposure for heating or over-deposition, thereby contributing to a smoother surface.

Figure 7(d) shows the contour plots for ‘GRG’ against temperature of the nozzle and infill density which are deemed in this present exploration. It is obvious from the illustration that the improved performance in FDM process is attained during the combinations of higher levels of infill density and nozzle temperature. This amalgamation like optimizes the flow of material, bonding and structural integrity, consequences to an enhanced mechanical characteristics and dimensional accuracy across the printed part. Similarly the combinations of higher levels of printing speed and lower levels of nozzle temperature produces the improved FDM process as depicted in Fig. 7(e). The increased printing speed decreases the time production time while maintaining enough level of material deposition and the lower nozzle temperatures prevents excessive heat buildup which could leads to thermal distortion or warping, optimizing the overall efficiency of the process. Also, the amalgamations of higher levels of infill density and printing speed produces with better performance as illustrated in Fig. 7(f). Increased ‘ID’ enhances the mechanical strength and stability of printed component, while increased printing speed reduces the production time without convincing the quality of the surface or accuracy of the part produced.

In the analysis of the main effects, it was found that nozzle temperature, printing speed, and infill density greatly affect the surface roughness, dimensional deviation, and printing time of the PETG components. The optimized parameters-namely, higher nozzle temperature, moderate printing speed, and increased infill density-produced better surface finish with less dimensional deviation [24] and the trends reported further corroborate that an elevated nozzle temperature and heightened infill density positively affect the overall part quality and mechanical performance in polymer additive manufacturing. Such alignment validates the robustness of the present Taguchi optimization and the reliability of the established process–performance correlations.

Regression models for performance metrics

A regression analysis is conducted to determine the relationship between the ‘GRG’ and the input factors. The analysis also presents the connection between the target performance metrics and the input variables. The linear, quadratic, interaction, and second order full model equations are denoted as (5, 6, 7, 8) correspondingly.

Performance Metrics | Model | Empirical Relations Developed | Eq. No |

|---|---|---|---|

GRG | Linear | −0.523702 + 0.00598377 A − 0.00251199 B − 0.000907005 C | 5 |

Quadratic | 14.2493–0.130142 A + 0.00509355 B + 0.000656686 C + 0.000309376 A*A − 7.60554e-005 B*B − 2.60615e-005 C*C | 6 | |

Interaction | −1.75132 + 0.0121958 A + 0.0414384 B − 0.0378709 C − 0.000212412 A*B + 0.000146955 A*C + 9.26788e-005 B*C | 7 | |

Second Order Full Model | 13.0217–0.12393 A + 0.0490439 B − 0.0363073 C + 0.000309376 A*A − 0.000212412 A*B + 0.000146955 A*C − 7.60554e-005 B*B + 9.26788e-005 B*C − 2.60615e-005 C*C | 8 |

Comparative study on actual and predicted model and performance analysis

The aim of this study is to develop regression models that can accurately forecast the GRG by establishing empirical relationships. The regression model was used to predict the outcomes of this experimental analysis. The study’s conclusions have been compared with the results acquired from the conducted experiment. A stronger correlation has been observed between the expected and actual outcome, as indicated in Fig. 8; Table 5. The data suggest a robust link between the anticipated and evaluated values of the GRG. The regression model clearly demonstrates a high level of accuracy in predicting the required performance metric with minimal error. The analytical results exhibit a significant correlation with both the planned and actual outcomes of the FDM of PETG, as mentioned.

Analysis on the evolved regression model

Prediction error refers to a numerical measure that arises when the values generated by a model differ from the values obtained from the experiment. The accuracy of this claim is confirmed by calculating the error using Eq. (7) and presenting the results in Table 6:

The correlation coefficient and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are utilized to assess the predictive model, which may be obtained from the formulae (8, 9):

The experimental values, denoted as ‘EV’, and the predicted values, denoted as ‘PV’, are gathered for a total of ‘n’ observations in the model.

Conclusions

An inclusive examination was done to investigate the FDM approach with PETG material. The aspiration was to determine an accurate forecast model for assessing the GRG. By means of the attained information, innovative forecast methods like regression models were established to envisage the essential performance measures.

-

The performance measures of FDM process has been attained by using L27 OA. The process factors have been adopted for optimizing the printing effectiveness. The ‘ID’ has the foremost impact on the performance measures which are deemed.

-

The grey approach was used to assess the multiple performance index of FDM approach. Also, it is ascertained that the regression approach has the capability to predominantly reduce the data uncertainty and improve the forecast capability of the model.

-

The study determined that the optimal FDM process parameters for PETG are a nozzle temperature of 230 °C, infill density of 25%, and printing speed of 40 mm/s, which resulted in a maximum Grey Relational Grade (GRG) of 0.8547. The regression model predicted a GRG value of 0.8365, demonstrating a strong correlation between experimental and predicted results.

-

The information attained by GRA behaves as the basis for foretelling the regression GRG values. This demonstrates the competitiveness of improved model in developing accurate forecasts, hence enhancing various industrial applications.

-

Indeed, the optimized process parameters proposed by this study do not just improve surface finishes, dimensional accuracy, and printing efficiency of PETG parts, but they would also, in a larger sense, provide a basis for industrial applications in automotive, aerospace, and biomedical sectors.

-

The regression-based predictive model makes it possible for manufacturers to forecast the performance outcome for different process conditions, thus contributing to more enhanced process planning and quality control.

-

Limitations are restricted to only one printer and type of material; future works might consider multiple FDM platforms, other polymers, and mechanical testing, thus extending further on generalization.

-

Future research can expand to other thermoplastic materials, different 3D printing platforms, and additional process variables. Integration with AI-based predictive models and hybrid optimization techniques could further improve the quality and reliability of FDM-manufactured components.

-

As a summary, the regression approach is proven to be an attractive tool for various manufacturing processes. This method can be adopted to accomplish various aspects in numerous engineering applications.

Data availability

The necessary data used in the manuscript are already present.

References

Abdulhameed, O., Al-Ahmari, A., Ameen, W. & Mian, S. H. Additive manufacturing: Challenges, trends, and applications. Adv. Mech. Eng. 11 (2), 168781401882288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814018822880 (2019).

Chen, D. et al. Twin-rich ag coatings by additive rotary spray deposition manufacturing: Current-carrying friction machining to construct nanolamellar structures. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 247, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2025.06.007 (2026).

Beaman, J. J., Bourell, D. L., Seepersad, C. C. & Kovar, D. Additive manufacturing review: early past to current practice. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 142 (11), 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4048193 (2020).

Bikas, H., Stavropoulos, P. & Chryssolouris, G. Additive manufacturing methods and modelling approaches: a critical review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 83, 389–405 (2016).

Ngo, T. D., Kashani, A., Imbalzano, G., Nguyen, K. T. Q. & Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos. B Eng. 143, 172–196 (2018).

Huang, S. H., Liu, P., Mokasdar, A. & Hou, L. Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: a literature review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 67, 1191–1203 (2013).

ISO ASTM 52900-21. Additive Manufacturing—General Principles—Fundamentals and Vocabulary (ASTM International, 2021).

Mohamed, O. A., Masood, S. H. & Bhowmik, J. L. Optimization of fused deposition modeling process parameters: a review of current research and future prospects. Adv. Manuf. 3, 42–53 (2015).

Somsole, L. N. et al. Experimental investigation and optimization of epoxy composites reinforced with jute fiber and alumina using the Jaya ANFIS approach. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 30462 (2025).

Chohan, J. S., Singh, R., Boparai, K. S., Penna, R. & Fraternali, F. Dimensional accuracy analysis of coupled fused deposition modeling and vapour smoothing operations for biomedical applications. Compos. B Eng. 117, 138–149 (2017).

Parandoush, P. & Lin, D. A review on additive manufacturing of polymer-fiber composites. Compos. Struct. 182, 36–53 (2017).

Praveen, H. S., Naveen, N. R. & Goudanavar, P. Engineering biomaterial scaffolds for melanoma: innovations in 3D printing and nanoparticle–hydrogel scaffolds for enhanced drug delivery. Biomed. Mater. Devices. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44174-025-00394-2 (2025).

Sahu, A., Kumar, P., Pratap, B., Gogineni, A. & Sembeta, R. Y. Thermal and mechanical performance of geopolymer concrete with recycled aggregate and copper slag as fine aggregate. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 28968 (2025).

Alzyod, H. & Ficzere, P. Ironing process optimization for enhanced properties in material extrusion technology using Box–Behnken design. Sci. Rep. 14, 2300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52827-5 (2024).

Alzyod, H., Kónya, G. & Ficzere, P. Integrating additive and subtractive manufacturing to optimize surface quality of MEX parts. Results Eng. 25 (103713), 103713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103713 (2025).

Alzyod, H., Ficzere, P. & Borbas, L. Optimizing ironing parameters in material extrusion (MEX) technology: enhancing efficiency and performance. Discov Appl. Sci. 6, 578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06249-7 (2024).

Alzyod, H. & Ficzere, P. Optimizing fused filament fabrication process parameters for quality enhancement of PA12 parts using numerical modeling and Taguchi method. Heliyon 9 (3), e14445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14445 (2023).

Hikmat, M., Rostam, S. & Ahmed, Y. M. Investigation of tensile property-based Taguchi method of PLA parts fabricated by FDM 3D printing technology. Results Eng. 11, 100264 (2021).

Rayegani, F. & Onwubolu, G. C. Fused deposition modelling (FDM) process parameter prediction and optimization using group method for data handling (GMDH) and differential evolution (DE). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 73, 509–519 (2014).

Enemuoh, E. U., Duginski, S., Feyen, C. & Menta, V. G. Effect of process parameters on energy consumption, physical, and mechanical properties of fused deposition modeling. Polym. (Basel). 13, 2406 (2021).

Natarajan, M. et al. Pallavi Giri, Saurav Mallik, and Kanad Ray. Machinability of titanium grade 5 alloy for wire electrical discharge machining using a hybrid learning algorithm. Information 14, 8 : 439. (2023).

Pasupuleti, T., Natarajan, M. & Krishnamachary, P. C. Lakshmi Narasimhamu Katta, and Jothi Kiruthika. Application of Taguchi based ANFIS approach in wire electrical discharge machining of haste alloy C276 for automobile applications. No. 2023-28-0167. SAE Technical Paper, (2023).

Faroze, F., Srivastava, V. & Batish, A. Dimensional and geometric deviation modelling for polycarbonate parts fabricated by fused filament fabrication-a machine learning approach. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM). 19 (10), 7217–7238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-025-02279-6 (2025).

Valvez, S., Silva, A. P. & Reis, P. N. B. Optimization of printing parameters to maximize the mechanical properties of 3D-printed PETG-based parts. Polymers 14 (13), 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14132564 (2022).

Faroze, F., Srivastava, V. & Batish, A. Enhancing mechanical properties of polycarbonate parts developed by fused filament fabrication using RSM-TOPSIS hybrid approach. Polym. Eng. Sci. 63 (12), 4186–4206. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.26517 (2023).

Manikandan, N., Thejasree, P., Vimal, K. E. K., Sivakumar, K. & Kiruthika, J. Applications of artificial intelligence tools in advanced manufacturing. In K E K, V., Rajak, S., Kumar, V., Mor, R.S.,Assayed, A. (eds) Industry 4.0 Technologies: Sustainable Manufacturing Supply Chains: Volume II-Methods for Transition and Trends 29–42 (Springer Nature, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4894-9_3

Manikandan, N., Thejasree, P., Lakshmi Narasimhamu, K. & Krishnamachary, P. C. Investigations on machinability and evolution of hybrid artificial intelligent tools for contemporary machining of nickel alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 38, 1514–1530 (2023).

Faroze, F., Srivastava, V. & Batish, A. Integrating RSM and ANN for surface quality modeling and prediction in fused filament fabrication. Progress Additive Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-025-01167-5 (2025b).

Faroze, F., Srivastava, V. & Batish, A. Modelling and prediction of mechanical properties of FFF-printed polycarbonate parts using ML and DA hybrid approach. Colloid Polym. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-024-05315-1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the authors’ respective institutions for their strong support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**P. Thejasree: ** Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft.**N. Manikandan: ** Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.**N. Rajesh: ** Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Review & editing.**R. Lokanadham: ** Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.**P. C. Krishnamachary: ** Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.**Kumar Shubham: ** Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing **.****Regasa Yadeta Sembeta: ** Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thejasree, P., Manikandan, N., Rajesh, N. et al. Multi-response optimization of PETG FDM parameters using taguchi–grey relational analysis and perdition by regression modeling. Sci Rep 15, 41831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25883-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25883-8