Abstract

Sustainable food packaging materials have gained significant attention due to environmental concerns and the necessity for functional packaging solutions. This study explores the development of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based films incorporating deep eutectic solvents (DES) and bioactive mango peel extract (MPE). The addition of DES enhances the mechanical and physicochemical properties of PVA films, while MPE provides antioxidant activity. The films were characterized for optical properties, barrier behavior, swelling capacity, and biological functionality. Incorporation of DES and MPE modified the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) from 23.5 for pure PVA to over 1000 g/m²/day, while swelling values ranged between 161 and 282%. Mechanical testing showed tensile strength values of 20–107 MPa with elongation at break between 10 and 417%, depending on film composition. Films containing MPE demonstrated effective UV-blocking ability and significantly enhanced antioxidant activity, with radical scavenging increasing from 17% in pure PVA to ~ 95%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Each year, around 89 million tons of food waste are generated in the European Union, with projections indicating that this figure is likely to increase fortyfold in the coming years1. Among various food products, fruits and vegetables constitute a significant percentage of wasted food—their processing leads to waste in the form of peels, seeds, and other inedible parts, which account for as much as 25%−30% of total production2.

Food waste and byproducts (FWBP) are a global issue that impacts the economy, resources, environment, and public health3. Practices, such as landfill disposal or incineration of fruit waste, contribute to secondary waste and are far from consistent with the principle of sustainable development4. In response to the growing interest in a “circular economy” increasing attention is being directed toward recovering valuable bioactive compounds from fruit waste and exploring their potential applications across various industries5.

Numerous studies have shown that fruit waste, especially peels, contains large amounts of commercially valuable bioactive compounds and phytonutrients, such as antioxidants, essential oils, phenolic compounds, and pigments6,7,8. This makes it a cheap and abundant resource for pharmaceutical, food, packaging, and cosmetics applications.

Mango peels (MP) account for about 15–20% of the mature fruit’s mass and are among the richest sources of bioactive compounds9. Many studies have confirmed that MP has the highest antioxidant activity compared to other fruits6,10. The phenolic compounds, carotenoids, anthocyanins, pectin, vitamins (A, C, and E), and enzymes found in MP work synergistically, enhancing its antioxidant potential and making it a valuable resource for modifying polymer materials11.

Incorporating bioactive extracts into packaging materials enables the creation of so-called active packaging, which not only protects the product from contamination but also extends its shelf life by inhibiting the growth of microorganisms and neutralizing free radicals12. Numerous examples of utilizing fruit extracts in the production of active films have been reported in the literature13,14. Research by A. Nor Adilah, incorporating mango peel extract (MPE) into fish gelatin films, demonstrated significant improvements in their barrier and antioxidant properties, making them a promising material for active food packaging15. The films with MPE showed reduced water vapor permeability and enhanced antioxidant activity, highlighting the potential of mango by-products in sustainable packaging development. Another study demonstrates that incorporating MPE into composite cellulose acetate and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) films significantly enhances their antibacterial properties, making them a promising natural solution for improving food safety and extending the shelf life of packaged products16. Furthermore, MP waste has been successfully used as bioactive ingredients in biodegradable food packaging films17,18,19.

The objective of this study was to develop a composite film based on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), deep eutectic solvents (DES), and bioactive extracts derived from MP, with a specific focus on evaluating its potential use as both food packaging and edible coatings. Importantly, the selected MPE and DES components are food-grade, with MPE being generally recognized as safe (GRAS), and DES constituents such as choline chloride, citric acid, and malonic acid widely accepted for food-contact applications, while glutaric acid is used at safe, low concentrations. The incorporation of DES – environmentally friendly solvents characterized by low toxicity – alongside phenolic compound-rich extracts aimed to enhance the film’s flexibility, thermal stability, antibacterial and antioxidant properties, as well as its UV protection. These considerations support the potential for safe use in edible or food-contact applications, aligning with regulatory and safety requirements. The main innovation of this study lies in the synergistic integration of DES and MPE into a PVA matrix. In our system, DES serve a dual role: as active agents that contribute to extending food shelf life and as plasticizers that improve the mechanical and physicochemical properties of the films. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of such a multifunctional use of DES in combination with fruit-waste-derived bioactive extracts in PVA films. This synergy enables the development of food packaging films with both enhanced functional performance and sustainability, offering a novel strategy for next-generation active packaging.

Materials and methods

Materials

PVA (Mowiol 6–98, Mw = 47 kDa, DH 98.0–98.8.0.8%); Choline chloride (ChCl) (purity ≥ 98%); Glutaric acid (GA) (purity ≥ 96%); Malonic acid (MA) (purity ≥ 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Calcium chloride (purity ≥ 97%); Ethyl alcohol (purity ≥ 99,8%) were purchased from Chempur, Poland. Citric acid (CA) (purity ≥ 99.5%) was purchased from Stanlab, Poland. The materials were used without any further purification. Demineralized water was used throughout the entire experiment. Wheat bread baked with natural leaven was purchased from a local bakery. The cherry tomatoes and mangos were purchased at a local grocery store. MP were dried at room temperature (RT), ground in a knife mill and sifted. The 0.25 mm fraction was used for the tests.

Preparation of the PVA solution

The PVA stock solution was prepared by dispersing 30 g of Mowiol 6–98 in 1 L of distilled water (3% w/v) at RT and stirring vigorously. The mixture was heated to a maximum of 75 °C until completely dissolved. The solution was cooled and left for further use.

Preparation of the DES

The hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and hydrogen bond donor (HBD) were used in a 1:1 molar ratio to yield the DES in all experiments. The ChCl regarded as HBA (dried in an oven for 24 h at 70 °C under reduced pressure to 0.1 MPa) and appropriate HBD (MA, CA or GA) were placed in a 100 mL one-neck flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The flask was placed in a water bath at 60 °C, and the mixture was stirred until a uniform liquid was obtained. The synthesized DES was then cooled to RT. The substrates used to obtain DES with the exact amounts of reagents used in the synthesis are presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. In each DES mixture, the same HBA – ChCl – was used. The prepared DES mixtures are labelled as ChCl/X, where X represents the HBD used. For example, DES labelled ChCl/CA refers to the mixture of choline chloride and citric acid in a 1:1 molar ratio.

Preparation of MPE

20 g of dry MP were extracted using 120 ml of 80% aqueous ethanol solution. The extraction was carried out at RT, placing the solution in a dark place for 24 h. Then the solution was filtered through filter paper and concentrated under reduced pressure at 40 °C to obtain 10 g of MPE.

To determine the dry matter content of the extract, a portion of the concentrated extract was completely dried until all solvent was removed. On average, 6.8983 g of dry extract was obtained from 20 g of dried MP, corresponding to an extraction yield of ~ 34.5% (w/w, dry extract/dry peel). This yield was used to contextualize the concentration of MPE incorporated into the films.

PVA film manufacturing

The solvent evaporation (solvent casting) method was applied to prepare the films. To prepare PVA film, 25 g of the 3% (w/v) Mowiol 6–98 solution was poured onto a Petri dish and dried under a hood at RT for one week. The prepared film was designated as PVA.

For the PVA/MPE film, 0.375 g of concentrated MPE was added to 25 g of 3% (w/v) Mowiol 6–98 solution and stirred at RT for 1 h to ensure thorough dispersion. Considering that the concentrated extract contains solvent, the actual dry mass of MPE added corresponds to approximately 0.193 g, which gives a dry mass fraction of ~ 25.7% relative to PVA (0.193 g MPE/0.75 g PVA × 100%). The mixture was then poured onto a Petri dish and dried under a hood at RT for one week.

For PVA/DES/MPE films, 0.32 g of the appropriate DES mixture was first combined with 25 g of 3% (w/v) Mowiol 6–98 solution and stirred at RT for 1 h to achieve homogeneity. Subsequently, 0.536 g of concentrated MPE was added. Considering the dry mass of MPE, this corresponds to ~ 0.276 g of dry extract, yielding a dry mass fraction of ~ 26.9% relative to the total dry mass of PVA and DES. The solution was poured onto a Petri dish and dried under a hood at RT for one week.

All film compositions were calculated based on the dry mass of MPE relative to PVA (and DES, if present), providing a clear quantitative context for the incorporation of bioactive material into the polymer matrix.

The prepared films were designated as PVA/X/MPE. For instance, the sample labelled PVA/MA/MPE was prepared using Mowiol 6–98, plasticized with a DES mixture of choline chloride and malonic acid in a 1:1 molar ratio, with the addition of MPE at 50% by weight relative to the combined mass of PVA and DES. The detailed composition of the tested PVA films is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Characterization techniques

Attenuated total reflectance-fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectrometer. Thirty-two scans were performed for each sample with a resolution of 4 cm1, based on OMNIC-9 software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The data was further analyzed by F. Menges “Spectragryph - optical spectroscopy software”, Version 1.2.16.1, 2022.

Scanning electron microscopy

The microstructure of the films was examined using a tabletop scanning electron microscope, model Quanta 200 (FEI Company, Fremont, CA, USA). Before imaging, the samples were cut into 10 × 10 mm sections and mounted on the measurement stage using a 9 mm carbon paste (Pik Instruments Sp. z o.o., Piaseczno, Poland). For cross-sectional analysis, the films were fixed to the holder at a 90° angle with carbon paste. Before microscopic observation, all samples were coated with gold using a Cressington 108 auto sputter coater (Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd., Watford, UK). The thickness of the gold layer was controlled by the sputtering duration, set to 25 s, resulting in a coating approximately 4.2 nm thick. SEM imaging was conducted at a magnification of ×1000 for both surface and cross-section analyses, using an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Water contact angle

Contact angle analysis was performed using the sessile drop technique with a goniometer (DataPhysics Instruments, OCA 25, Germany). The contact angle was measured after the release of a 10 µL drop of distilled water at a speed of 10 µL/s on the surface of the films. For each film, six repetitions were made. The results were recorded by the SCA20_U software.

Water vapor transmission rate (WVTR)

For the analysis of PVA films, metal screw-capped containers (55 mm in diameter) were filled with 10 g of calcium chloride. The desiccant was pre-dried at 75 °C under vacuum (~ 100 mbar) for 24 h and then used in accordance with the desiccant (dry-cup) method described in ASTM E96/E96M and ISO 2528. A piece of polymer film was placed between two rubber seals, pressed with a Teflon ring, and screwed with a metal cover - a ring to ensure a tight seal. The prepared vessels were left for 24 h in a climatic chamber at 30 °C and a relative humidity of 75%. The WVTR value was determined by measuring the mass change of calcium chloride over time. Three tests were performed for each film.

Oxygen (OTR) and carbon dioxide (CO2TR) transmission rate

Oxygen and Carbon dioxide transmission were determined using a gas permeability test system C130 (Labthink Instruments Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) according to ASTM D1434-82. Samples were cut from each film, and their thickness was measured using a thickness tester (Thwing-Albert, ProGage Thickness Tester, USA) with an accuracy of 1 μm. For barrier property tests, five measurement points per sample were taken on each permeable surface (four around the edges and one in the center). The samples were placed on a filter and a vacuum was applied inside the system. Oxygen or carbon dioxide was then diffused through the film into a cell, where the amount of gas was determined by the manometric method. Measurements were conducted in accordance with ASTM D1434-82 at 23 ± 1 °C and 40 ± 5% relative humidity. Two replicates were performed for each film.

Swelling behavior

The mass equilibrium degree of swelling (S) was determined by immersing a 2 × 2 cm fragment of the film in a beaker containing 100 mL of distilled water, stirred at RT and 150 rpm. Samples were periodically removed, gently dried using filter paper, and weighed until no further weight increase was observed, the film disintegrated, or it dissolved. The mass equilibrium degree of swelling (S) was calculated according to Eq. (1):

where: m1, mx - dried sample mass and the sample mass after swelling, respectively. Three tests were performed for each film.

Tensile properties

The analysis of the mechanical properties of the obtained films, defined as elongation at break (ε), tensile strength (σ), and Young’s modulus (E), was carried out under static tension conditions according to the PN-EN ISO 527-1:2020-01 standard, using an Instron 3345 testing machine (Massachusetts, USA). Five specimens of each tested film, with a measuring section of 30 mm, were stretched at a speed of 50 mm × min− 1. The elongation was determined based on the relative position of the crosshead.

Thermogravimetric analysis

The measurements were performed on a thermogravimetric analyser (NETZSCH TG 209 F1 Libra®, Germany), with NETZSCH Proteus Thermal Analysis 8.03 data processing software. For thermogravimetric testing, approximately 15 mg of the ingredients was prepared in.

a ceramic crucible and heated in an argon atmosphere at a rate of 10 °C × min− 1 up to 700 °C. The changes occurring in the samples were recorded by recording 5, 10, and 50% mass loss and % mass loss of the sample at maximum temperature.

Film color

The colour of films was determined in 10 repetitions with a colorimeter, CR-400 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), using the CIELAB colour parameters: L* from black (0) to white (100); a* from green (-) to red (+); and b* from blue (-) to yellow (+). The colour of films was expressed as the total colour difference (ΔE) according to the following Eq. (2)20:

where: ΔL*, Δa* and Δb* are the differentials between the colour parameter of a white standard used as the film background (L*= 91.81, a*= −0.59, b*= 1.30) and the sample colour parameters.

UV-Vis measurements

The UV-Vis measurements were recorded via UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, Kyoto, Japan). Polymer film samples of 0.9 cm width were put into a silica cuvette and the transmittance measurements within the wavelength range of 190–800 nm were registered.

The opacity of films was determined by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm (A600) using UV spectrophotometer according to the method of Priyadarshi et al.21 The film, cut into a rectangle, was placed directly in a spectrophotometer test cell. The opacity was evaluated using Eq. (3):

where: d is the film thickness [mm].

To assess the optical properties, we measured the transmittance of each prepared film and calculated the SPF (sun protection factor) using a specified formula developed by Mansur et al.22, Eq. (4):

Where: EE = erythemal effect spectrum, I = solar intensity spectrum, Abs = Absorbance of prepared films, and CF = correction factor (= 10).

The EE x I values have been normalized across multiple wavelengths and remain constant. These values are presented in Table S2 (Supplementary Materials)23.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH-radical scavenging capacity of the PVA based films was determined using the method given in the literature with some modifications24. 500 µL of methanolic extracts of films (0.5 g films/3.75 mL MeOH) was transferred into the testing tubes and mixed with 2 mL of methanolic DPPH solution (C = 304.0 µmol/L). These test tubes were kept at ambient temperature in the dark for 30 min. Then the absorbance of the mixture at λ = 517 nm was measured. Three replicates for each tested sample were performed. The scavenging capacity of the DPPH-radical was calculated according to Eq. (5):

where: ADPPH is the absorbance of the methanolic DPPH solution and Asample is the absorbance of the sample extracts.

Determination of pH in cherry tomatoes after storage

The experiment was conducted following a protocol developed at the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Industrial Chemistry Institute in Warsaw, Poland25. Briefly, homogeneous cherry tomatoes were thoroughly washed with distilled water and dried. Subsequently, the tomatoes were immersed in the prepared polymer solutions described in Sect. 2.5 (Production of PVA Films) for 60 s and left to drain for 15 s to remove excess solution. The coated fruits were then air-dried at RT. Three experimental groups of cherry tomatoes were analyzed: (1) uncoated (control group), (2) coated with PVA solutions, and (3) coated with PVA solutions containing DES (PVA/CA/MPE, PVA/MA/MPE, and PVA/GA/MPE). The tomatoes were stored at RT under standard laboratory conditions, with relative humidity not actively controlled and ambient laboratory lighting. Only a single set of samples was used. Fruit quality was assessed by measuring the pH of tomato juice at the start of the experiment (day 0) and after 5, 12, and 22 days of storage. Tomato juice pH was measured with a calibrated IS139 pH meter (InsMark Instrument Technology Co., Shanghai, China) using standard buffer solutions at pH 4.01, 7.00, and 9.21.

Antifungal activity in contact with bread

Antifungal activity in contact with bread was performed in a procedure developed at the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Industrial Chemistry Institute in Warsaw, Poland25. Briefly, fungal resistance was evaluated by monitoring the time required for fungal growth on bread samples. Uniform 4 cm × 4 cm pieces of white bread were prepared for testing. The control sample remained unwrapped and unprotected, while the other samples were individually wrapped and sealed in direct contact with one of the tested films: polyethylene (PE), PVA/MPE, PVA/CA/MPE, PVA/MA/MPE, or PVA/GA/MPE. Bread samples were stored at RT under standard laboratory conditions, with relative humidity not actively controlled and ambient laboratory lighting, and only one set of sample was performed. Photographs of the samples taken after 22 days of testing are provided in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistical analysis

The mean values and standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2019. Statistical analysis was conducted with Statistica 13 software (StatSoft Sp. z o.o., Warsaw, Poland). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The assumption of homogeneity of variances was tested, while the assumption of normality was not examined. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was considered for all analyses.

Results and discussion

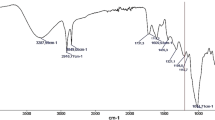

Molecular structure (ATR-FTIR)

The performed ATR-FTIR analysis allowed to investigate the interaction of the polymer matrix with the plasticizer, as well as to identify unique signals associated with different compounds included in the film synthesis. FT-IR spectra for all tested samples can be found in Figures S2-S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Alcohols generally show broad absorption bands in the 3700–3580 cm− 1 range. The presence of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups in polymer structures leads to a shift of the O–H stretching bands toward lower frequencies26. The peak observed at approximately 3260–3280 cm− 1 in all spectra is attributed to the free vibration of hydroxyl groups, covering both intramolecular hydrogen bonds within PVA and intermolecular hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups in PVA27. Prior research indicates that shifts in the DES stretching vibration near 3300 cm− 1 are key indicators of hydrogen bond formation between HBA and HBD28,29. Moreover, the formation of new bonds can also be observed by the increase in peak intensity. During the DES formation process, the hydroxyl groups (O–H) on each carboxylic acid monohydrate interact with the chloride anion in ChCl, forming an O–H···Cl bond. This interaction is likely driven by the quaternary ammonium salt and hydrogen bond donor, enhance hydrogen bonding, particularly with hydroxyl groups, and influence the strength of the O-H bond.

The PVA backbone exhibits absorption bands for asymmetrical and symmetrical C–H stretching at 2940 cm− 1 and 2912 cm− 1, respectively. Peaks at 1715 cm− 1 are attributed to C = O stretching of unhydrolyzed acetate groups or free acetate ions from the stock PVA30. Increased intensity of bands related to carbonyl stretching may indicate hydrogen bonding interactions, as DES formation is often associated with intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions31. Moreover, this peak may come from the stretching vibrations of the C = O groups of carboxylic acids. The location of the C = O stretching band is also influenced by factors like nearby groups and the compound’s physical state. Small peaks at 1470 cm− 1 are evident in some spectra and are characteristic of the (CH₃)₃N⁺ group in ChCl. Additionally, peaks at 1415 cm− 1 and 1320 cm− 1 are attributed to secondary O–H bending in-plane and C–H wagging vibrations, respectively. Peaks at 1375 cm− 1 refers to C–H bending vibrations in -CH3 groups. The peaks around 1240 and 1200 cm− 1 correspond to -CO groups stretching in PVA32.

The C–C–C stretching sharp band appears at 1140 cm− 1, while the bands at 1084 cm− 1 and 1050 cm− 1 represent C–O stretching vibration in PVA. For samples with DES, peaks at 953 cm− 1 and 918 cm− 1 correspond to asymmetric and symmetric C–N stretching, originating from ChCl. The peaks at 840 cm− 1 and 780 cm− 1 are associated with the out-of-plane bending vibration of -OH groups in PVA. No significant influence of MPE addition on the location of existing or the formation of new bands in the FTIR spectrum was recorded.

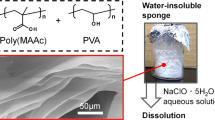

Films microstructure and colour

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analyze the surface and cross-sectional morphology of the obtained films to assess their structural integrity and the impact of MPE and DES incorporation. Table 1 presents SEM images of all film samples at ×1000 magnification.

The control PVA film exhibited a homogeneous, smooth surface with a thickness of 155 μm. In contrast, biocomposite films enriched with MPE showed slight morphological changes, including small, single holes (0.73–2.5 μm) visible in both surface and cross-section images. Despite the presence of these pores, the overall integrity and coherence of the films were maintained.

The formation of these holes is likely due to MPE incorporation, which also contributed to an increased film thickness of up to 210 μm compared to pristine PVA33. This effect may be attributed to the method of introducing MPE (as an alcohol solution, with particles enclosed within the polymer layer) and the solvent evaporation technique used for film formation. Further addition of DES compounds increased the thickness to 225 μm for GA-based DES, 235 μm for CA-based DES, and up to 243 μm for MA-based DES.

Similar morphological changes due to MPE incorporation have been observed in pH-sensitive intelligent films based on gelatin34 and cassava starch–chitosan composites35. Additionally, substrate surface modifications with natural active compounds, such as cinnamaldehyde36 and sugarcane purple rind extract37, have been reported to impact material surfaces, including carbon steel and steel.

The influence of MPE additives on the optical properties of PVA films was evaluated using the CIELab color parameters (L*, a*, and b*), as presented in Table S3 (Supplementary Materials). All the films exhibited high transparency, with MPE-containing samples displaying a slight yellow tint. The addition of MPE into PVA films resulted in changes to the L*, a* and b* values. The L* values, corresponding to the brightness definitions, are recorded at a similarly high level for all samples (approx. 88%)38. As positive a* indicates redness and negative a* indicates greenness, the recorded a* values for samples containing MPE are lower than for pure PVA, which indicates higher greenness. Regarding the b* parameter, where positive value indicates yellowness and negative value indicate blueness, all samples show positive b* values. However, in the case of samples containing MPE, b* reaches values of an order of magnitude higher (in the case of CA-based DES more than 17x higher), confirming that the addition of MPE imparts a yellow tint to the films.

Physical appearance and optical properties of polymeric films are of considerable importance in packaging applications. Therefore, the opacity parameter was also evaluated and is summarized in Table 1. The opacity at 600 nm was found to be 0.34 mm− 1 for the PVA/MPE film and slightly increased with incorporation of ChCl/CA (0.54 mm− 1) and ChCl/MA (0.43 mm− 1) mixtures. However, in the case of the PVA/GA/MPE film, no significant changes in opacity were observed compared to the PVA/MPE sample. The decrease in transparency of polymer films incorporated with DES is consistent with results reported by other researchers39,40. Meanwhile, Hopkins et al.41 and Shojaee-Aliabadi et al.42 stated that the darker appearance of films was attributed to light scattering by the extract.

Although food packaging materials are generally transparent and colorless, colored films can also offer benefits by shielding against ultraviolet and visible light, which can contribute to food spoilage43.

Water contact angle

Information about the interactions between films and water is very important for the packaging industry. The water contact angle is a widely used parameter for assessing the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of a film’s surface. It also provides insights into properties such as absorption and adhesion. All the tested films exhibited water contact angles below 90 °, indicating relatively high hydrophilicity44.

The pristine PVA film demonstrated a notably hydrophilic surface (θ = 61.8 °), which can be attributed to the abundance of hydroxyl groups that facilitate hydrogen bonding with water molecules. However, the incorporation of MPE and DES into the polymer matrix led to an increase in contact angle values. The water contact angles of PVA/MPE, PVA/CA/MPE, PVA/MA/MPE, PVA/GA/MPE were 72.2 °, 76.5 °, 71.8 °, and 57.5 °, respectively (Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials), indicating a reduction in surface wettability and a shift toward more hydrophobic behavior compared to the unmodified PVA. This effect can be attributed to the presence of hydrophobic moieties within the MPE component, which likely disrupt hydrogen bonding interactions between water molecules and the hydroxyl groups of the PVA matrix. As a result, the surface energy of the modified films decreases, leading to a reduced affinity for water. The variations in contact angle values among the different DES mixtures suggest that the specific interactions between MPE and additional components (CA, MA, and GA) influence the extent of hydrophobicity, highlighting the tunable nature of these films for potential packaging applications.

Water vapor transmission rate (WVTR)

The WVTR is one of the key parameters used to characterize the barrier properties of materials employed in the packaging industry. It determines the amount of water vapor passing through a unit area of material over a specific time under standard temperature and humidity conditions. A low WVTR is essential in food packaging, as excessive moisture can accelerate spoilage, promote mold growth, degrade texture and flavor, and shorten shelf life.

The analyzed samples demonstrated varying WVTR values, reflecting their composition and polymer structure differences (Fig. 1). Native PVA exhibited the lowest WVTR value of 23.51 ± 1.39 g/m2/day. This low level of water vapor permeability can be attributed to the highly ordered polymer structure, which effectively restricted water vapor diffusion through the material.

The addition of MPE to the PVA matrix caused a slight disruption in the ordered polymer structure, resulting in a modest increase in WVTR to 49.46 ± 1.43 g/m2/day. Samples PVA/CA/MPE, PVA/MA/MPE, and PVA/GA/MPE, which included a plasticizer, displayed significantly higher WVTR values of 775.47 ± 33.16 g/m2/day, 1039.34 ± 25.30 g/m2/day, and 1014.08 ± 52.82 g/m2/day, respectively (Fig. 1). The presence of the plasticizer, intended to improve the flexibility of the material, negatively affected its barrier properties. This effect aligns with literature reports indicating that plasticizers reduce structural order and increase the mobility of polymer segments45.

Notably, PVA/CA/MPE film showed better barrier properties compared to PVA/MA/MPE and PVA/GA/MPE samples. This is likely due to CA’s function as a cross-linking agent, which partially restricted water vapor diffusion through the polymer network. The stronger cross-linking effect of CA, compared to MA and GA, can be attributed to its trifunctional nature, allowing it to form a denser and more interconnected network within the polymer matrix46. However, it is important to note that the solubility results contradict this assumption, suggesting that while CA may contribute to some degree of cross-linking, it does not necessarily lead to a fully water-resistant structure. The barrier properties of packaging materials must be tailored to meet the requirements of specific products. PVA and PVA/MPE films, with low WVTR values, appear to be promising candidates for packaging moisture-sensitive products such as dry foods and pharmaceuticals. However, the limited mechanical strength of these materials poses a significant challenge to their practical application.

Conversely, the introduction of plasticizers improved the mechanical properties, enhancing their potential for applications requiring more flexible packaging. However, this improvement was achieved at the expense of barrier properties, which may limit their use in packaging moisture-sensitive products. The results highlight the need to balance mechanical performance and barrier properties when designing polymer films for specific applications.

Oxygen transmission rate (OTR)

Packaging materials play a crucial role in preserving food quality and safety by preventing exposure to contaminants, microorganisms, oxygen, moisture, and light47. Among these factors, oxygen is particularly detrimental, as it accelerates food spoilage through oxidative rancidity in lipid-containing products. Consequently, the development of active packaging solutions with enhanced barrier properties is essential for extending shelf life15. Native biopolymer films are characterized by a highly organized molecular structure, which contributes to their low OTR. However, their rigid nature often limits their industrial applications. The addition of plasticizers enhances film flexibility but also disrupts polymer chain organization, increases free volume, and raises oxygen transmission11.

The measured OTR values of the PVA-based film samples are presented in Fig. 2. The unmodified PVA film exhibited a low OTR of 2.94 ± 0.71 cm3/m2/day, whereas the incorporation of MPE slightly increased this value to 5.54 ± 1.01 cm3/m2/day. The slight increase in OTR after the incorporation of the extract can be attributed to its chemical composition, which consists primarily of low-molecular-weight organic compounds, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactive molecules. The extract does not exhibit plasticizing properties and does not disrupt the polymer’s crystalline structure, which helps maintain the material’s overall barrier integrity.

Further modifications with DES significantly influenced oxygen permeability. The introduction of DES increased OTR values to 19.14 ± 1.37 cm3/m2/day for PVA/CA/MPE film, 39.55 ± 5.70 cm3/m2/day for PVA/MA/MPE film, and 52.58 ± 14.08 cm3/m2/day for PVA/GA/MPE film (Fig. 2). These results suggest that CA-based DES promotes a denser polymer network, effectively restricting oxygen diffusion, while GA-based DES appears to increase free volume within the polymer matrix, enhancing gas permeability. This highlights the critical influence of DES composition on the structural and functional properties of the polymer. A deeper understanding of these interactions can aid in the design of tailored materials for applications requiring precise control over gas barrier characteristics.

OTR values should remain below 10–20 cm3/m2/day for effective protection of oxygen-sensitive products48. The unmodified PVA film, PVA with MPE, and PVA/CA/MPE all meet this requirement (Fig. 2). While the OTR values for PVA/MA/MPE and PVA/GA/MPE exceed this threshold, they remain significantly lower than those of conventional fossil-based packaging materials. For comparison, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) exhibits an OTR of 550–700 cm3/m2/day49, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) ranges from 7,000 to 8,500 cm3/m2/day50, and polypropylene (PP) ranges from 93 to 300 cm3/m2/day.49 These comparisons underscore the superior barrier properties of PVA-based films, positioning them as a promising alternative for packaging applications aimed at minimizing oxidative degradation. It is also worth noting that measurement conditions influence gas permeability and may vary. Comparing different materials in terms of gas transmission is often challenging, as factors such as humidity can significantly affect the results.

Carbon dioxide transmission rate (CO2TR)

The CO₂ transmission rate (CO₂TR) is crucial for maintaining controlled atmospheres in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), essential for preserving fresh produce and preventing oxidation in dry, fatty foods51. Excessive CO₂, however, can accelerate spoilage52,53.

CO₂TR values for PVA-based films (Fig. 2) show that unmodified PVA exhibited 4.62 ± 1.50 cm3/m2/day, while adding MPE significantly reduced CO₂ permeability to 1.87 ± 0.20 cm3/m2/day. This reduction is likely due to polyphenolic compounds, cellulose, and lignins in MPE, which densify the polymer network through hydrogen bonding, restricting gas diffusion. Hydrophobic components may further limit CO₂ transport by reducing water absorption in the film.

In a similar trend to OTR measurements, after the introduction of DES, the CO2TR value increased compared to the samples without plasticizers (Fig. 2). CO2TR was 10.48 ± 1.07 cm3/m2/day for the PVA/CA/MPE, 17.15 ± 1.27 cm3/m2/day for the PVA/MA/MPE, and 20.90 ± 5.24 cm3/m2/day for PVA/GA/MPE. Likely to the OTR, the introduction of DES results in an increase in CO2 permeability, with the lowest CO2TR values recorded for most structurally packed films of CA-based DES.

These values provide critical insight into the material’s ability to regulate the package’s internal atmosphere. This understanding can inform the design of more efficient packaging solutions tailored to the specific preservation requirements of different food products, thereby reducing spoilage and minimizing waste. By optimizing packaging conditions for each food type, freshness can be maintained, and shelf life can be significantly extended.

Swelling behaviour

The swelling ratio is a feasible method to value the water absorption ability of polymeric materials. The experimental data obtained to evaluate the swelling behavior of the films are presented in Figure S5 in the Supplementary Materials. The swelling ratios of all the PVA-based films increased with time. It can be seen from Figure S5 (Supplementary Materials) that the water absorption of the film decreases with the introduction of the ChCl/MA or ChCl/CA mixtures to PVA/MPE films. This effect can be attributed to the interactions between DES, MPE, and PVA, which enhance the cross-linking density of the polymer network. The formation of additional hydrogen bonds and new ether bonds (due to the presence of the extract) further reduces the availability of free hydrophilic groups, thereby decreasing the film’s overall water uptake54.

In contrast, the film containing ChCl/GA and MPE exhibited significantly higher water absorbency. In the case of this film, the total process time was 7 min, with a degree of swelling of 281%. This property is particularly advantageous for absorbing excess water from the outer surface of high-moisture foods, making the films suitable for packaging soft or moisture-rich products.

Overall, the results indicate that the incorporation of MPE improves the water resistance of PVA/DES films, thereby enhancing their durability and extending their potential service life in packaging applications. These findings highlight the balance between flexibility, water absorption, and barrier properties, which should be considered when designing films for specific high-moisture food packaging applications.

Mechanical properties

Flexible and high strength elastic nature is a desirable attribute for food packaging films to protect the food material intact. The mechanical properties of PVA films with MPE and DES are presented in Table 2.

A comparison between the PVA/MPE film and the pristine PVA film reveals that the incorporation of MPE leads to a reduction in mechanical strength. Specifically, the addition of MPE significantly decreased the σ from 107 MPa to 83 MPa and the E from 4100 MPa to 3081 MPa in comparison to the native PVA sample. These results are consistent with the observations of other researchers55. Notably, demonstrated that pristine polymer films exhibit higher strength and elasticity than those modified with bioactive compounds extracted from fruits56.

A further decline in both σ and E values was observed upon the incorporation of DES into the PVA/MPE matrix. Compared to the PVA/MPE film with a strength of 83 MPa, the PVA/DES/MPE films exhibited an approximately 70% reduction in σ, reaching around 30 MPa. This reduction can be attributed to the formation of additional hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups of PVA, carboxyl groups from DES donors, and polyhydroxy compounds present in MPE. These interactions likely induce structural disruptions within the polymer matrix, thereby diminishing tensile stress resistance57.

Analogously, the E of the PVA/MPE film showed a considerable decrease with the addition of DES to the matrix. The E of the PVA/DES/MPE films was below 130 MPa. Importantly, the E value depended on the type of DES used, following the trend: ChCl/CA > ChCl/MA > ChCl/GA. Despite the decline in the tensile strength, all PVA-based films exhibited a higher ɛ compared to the pristine PVA film, with the PVA/GA/MPE film reaching the highest ɛ value of 417%. The addition of plasticizers generally enhances flexibility by disrupting polymer chain interactions and increasing molecular mobility. However, MPE may counteract this effect through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with PVA molecules, partially reinforcing the polymer network. Structural rearrangements within the PVA matrix may also contribute to variations in ɛ values among films containing plant extracts58. Similarly, reported that increasing pineapple peel extract (PPE) in PVA/corn starch films reduced tensile strength (from 32.77 MPa to 17.12 MPa)59. Flexibility followed a dual trend, peaking at 10% PPE (26.12%) before declining at 20% PPE (6.89%). These findings align with our results, further highlighting the balance between plasticization and structural reinforcement in bio-based films.

Thermal stability

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is a widely used technique to evaluate the thermal properties of polymeric materials by examining their weight loss as a function of temperature. The data presented in Fig. 3 demonstrate variations in the temperatures corresponding to 5% weight loss (T5%), 10% weight loss (T10%), and 50% weight loss (T50%) for different PVA-based samples. The initial weight loss observed between approximately 120 and 280 °C, corresponds to the early stages of degradation, primarily involving the elimination of volatile components such as water. Specifically, the T5% values, affected by the material’s water content, were detected at these lower temperatures. Beyond this point, spontaneous degradation of PVA begins above 260 °C, marking the onset of significant thermal decomposition processes60. Thermogravimetric results for the stock Mowiol 6–98 and for the used DES mixtures are presented in Figure S6, Supplementary Materials.

Modifications of PVA with various additives, as seen in the PVA/MPE, PVA/CA/MPE, PVA/MA/MPE, and PVA/GA/MPE samples, actually lead to a downward shift in T5%, T10%, and T50% values, indicating a decrease in thermal stability. This suggests that the addition of these components, particularly hydrophilic DES in the case of PVA/MPE, accelerates the onset of weight loss and lowers the temperature at which significant decomposition begins. For example, the T5% value for PVA/MPE occurs at 214 °C, whereas the inclusion of the hydrophilic DES in PVA/MPE further reduces T5% to 152 °C. This demonstrates that the presence of these additives, especially hydrophilic ones, compromises the thermal resistance of the PVA matrix, making it more susceptible to degradation at lower temperatures.

A similar trend is observed in the results shown in the Figure S7 in the Supplementary Materials, which depicts the weight loss of different PVA-based samples at 700 °C. The data indicate that the addition of MPE and DES leads to a lower overall weight loss at this elevated temperature compared to pure PVA. Interestingly, the addition of ChCl/CA and ChCl/GA results in materials with the lowest mass loss among the studied samples, with a weight loss of approximately 92%. In comparison, pure PVA exhibits a mass loss of 97% at elevated temperatures. This enhanced thermal stability can be attributed to the intermolecular crosslinking of PVA through ChCl/GA and ChCl/CA, resulting in the formation of a three-dimensional network structure that provides greater resistance to thermal decomposition61.

Moreover, despite the lowered T5% and T10% values, the films remain suitable for typical room-temperature storage and low-to-moderate temperature applications, highlighting the trade-off between the improved flexibility conferred by DES and the slightly reduced thermal stability, which should be considered when designing films for high-temperature packaging.

UV-Shielding performance and visual transparency

Transparency in food packaging is crucial, as less transparent films help prevent lipid oxidation62. UV-blocking properties are essential for preserving light-sensitive products, preventing degradation, oxidation, and quality loss63. Incorporating UV-blocking agents enhances stability and reduces the need for preservatives.

PVA films are characterized by excellent transparency at the level of 80% of visible light, showing a slight decrease in transparency in UV light (Fig. 4) consistent with the literature64. DES incorporation does not significantly alter absorption, as its strong hydrogen bonds lack intrinsic UV absorbance.

Within the UV-Vis range (approximately 380–800 nm), the tested films exhibit distinct transmittance characteristics. In the range 550–800 nm, all tested films maintain a relatively high and consistent transmittance of 75–85%. As the wavelength decreases toward the ultraviolet region, the transmittance of films containing MPE, gradually declines reaching values of approx. 30–50% at 380 nm. The films are still characterized by high transparency, taking on a yellowish tint (Table S3, Supplementary Materials). In the UV-A light range, there is a clear refraction of the registered spectrum resulting from the absorption of UV radiation and a decrease in transmittance to the level of 0% for 315 nm. All samples containing MPE show full absorption of UV-B and UV-C radiation. UV light screening originates from the MPE compounds, which contain a high level of pectin along with various carotenoids65 and phenolic compounds, such as gallates, flavonoids, ellagic acid, mangiferin, and maclurin derivatives66. The UV-absorbing substances found in MP make them a promising natural component for green food packaging materials, as well as for sunscreens and skincare products, offering UV protection by neutralizing free radicals67.

Based on the SPF values calculated according to Eq. 4 (Figure S8, Supplementary Materials), the incorporation of MPE and DES into PVA films significantly enhanced their UV-blocking properties. The SPF of the pristine PVA film was 2.5, while the addition of MPE alone increased the SPF to 25.4, corresponding to a ~ 10-fold improvement. Films containing both MPE and DES showed further enhancement: PVA/CA/MPE exhibited an SPF of 35.7, PVA/MA/MPE 30.1, and PVA/GA/MPE 32.9, representing 12–14-fold increases relative to pristine PVA. These results quantitatively demonstrate the strong UV-blocking ability of the bioactive films.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant properties of PVA-based films incorporating DES mixtures and MPE were evaluated using the DPPH radical scavenging assay (Fig. 5). The pristine PVA film exhibited a relatively low antioxidant activity of 17.04 ± 0.45%, consistent with previous studies reporting negligible radical scavenging capacity in unmodified synthetic polymers68. However, the incorporation of MPE significantly enhanced the antioxidant potential, with the PVA/MPE film achieving 94.19 ± 0.06% DPPH scavenging activity. This increase is attributed to the high content of polyphenols and flavonoids present in MPE, well-documented natural antioxidants10.

In turn, the antioxidant activity of the PVA/CA/MPA, PVA/MA/MPA, and PVA/GA/MPA films reached 94.91 ± 0.08%, 94.25 ± 0.59%, and 95.09 ± 0.00%, respectively. These results suggest that the inclusion of DES mixtures does not significantly hinder the antioxidant efficacy of the MPE but rather maintains or slightly enhances its radical scavenging properties. Similar effects have been observed in studies utilizing eutectic solvents to improve the solubility and stability of bioactive compounds, thereby preserving their functional properties69,70.

Overall, these findings confirm that MPE is an effective antioxidant when incorporated into a PVA matrix and that the use of DES as a plasticizer does not negatively impact its radical scavenging ability. These results align with previous reports demonstrating that bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenol-rich extracts, retain high antioxidant potential when embedded within polymeric matrices71. This suggests potential applications of these films in active food packaging or biomedical materials, where antioxidant properties are desirable.

Determination of pH in cherry tomatoes after storage

The pH measurement of tomato juice showed clear differences depending on the type of coating and the storage time. In uncoated tomatoes (control), pH gradually increased over 22 days, indicating natural degradation and fermentation (Fig. 6). In the case of tomatoes coated with PVA solution, the pH changes were less pronounced, suggesting a protective effect of the PVA coating that slows down biochemical processes in the fruits, consistent with literature reports72,73.

The greatest pH stability was observed in the groups of tomatoes coated with PVA solutions containing DES, with variations depending on the DES type. The PVA/GA/MPE coating exhibited the least increase in pH, suggesting that this combination was the most effective in protecting against the degradation of organic acids in tomatoes compared to other coatings (Fig. 6).

Overall, the results indicate that PVA coatings, particularly those with DES, contribute to stabilizing the quality of tomatoes during storage. Among them, PVA/GA/MPE exhibited the greatest ability to slow down degradation, highlighting its potential for extending the shelf life of fruits.

Antifungal activity in contact with bread

The antifungal activity of the tested films varied significantly. In the control group, where bread was left unwrapped, complete drying occurred within a few hours, while Bread wrapped in PE film developed visible mold after 4 days of storage. In contrast, bread wrapped in films containing DES and bioactive MPE exhibited no mold growth during the observation period. Gradual drying of the bread was observed, with significant moisture loss becoming evident only after 8 days. The antifungal properties of PVA films are attributed to the presence of MPE and DES. Bioactive compounds in MP, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, tannins, and terpenes, disrupt microbial cell membranes and enzymatic processes, inhibiting fungal growth74,75. The combination of these bioactive extracts and DES produces a synergistic effect, significantly increasing the overall antifungal activity of the film.

PVA films without additives showed no antifungal activity, underlining the necessity of bioactive modifications to achieve effective microbial inhibition76. The use of MPE not only introduces antifungal activity but also aligns with the principles of sustainability by valorizing agro-industrial waste. This approach supports the development of innovative food packaging solutions that extend shelf life while reducing reliance on synthetic preservatives and non-biodegradable materials.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed a PVA-based film enhanced with DES and MPE, demonstrating improved optical, mechanical, and antioxidant properties. The incorporation of MPE provided significant antifungal activity, effectively extending the shelf life of perishable food products, while DES improved mechanical properties. The films exhibited promising UV-blocking capabilities (complete absorption of UV-B and UV-C radiation) and very high antioxidant activity (increasing from 17% for pure PVA to ~ 95% after MPE addition), making them viable alternatives for sustainable food packaging. Specifically, the films showed a WVTR values ranging from 23.5 g/m2/day (pure PVA) to over 1000 g/m²/day depending on DES composition while mechanical performance was significantly enhanced, with elongation at break increasing up to 417% compared to 29% for native PVA films. Additionally, fungal growth on stored bread was delayed from 4 days (polyethylene) to 22 days when wrapped in PVA/MPE/DES films, and coatings with PVA/DES/MPE stabilized the pH of cherry tomatoes during 22 days of storage. The results highlight the potential of utilizing agro-industrial waste to create functional, eco-friendly materials, contributing to the advancement of circular economy strategies. Future research should focus on optimizing formulation parameters and evaluating long-term stability in real-world food storage conditions.

Data availability

The datasets supporting this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Hussain, H. et al. Fruit peels: food waste as a valuable source of bioactive natural products for drug discovery. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 44 (5), 1960–1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44050134 (2022).

Pathania, S. & Kaur, N. Utilization of fruits and vegetable By-Products for isolation of dietary fibres and its potential application as functional ingredients. Bioact Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 27, 100295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcdf.2021.100295 (2022).

Xie, D. et al. Developing active and intelligent biodegradable packaging from food waste and byproducts: A review of Sources, Properties, film production Methods, and their application in food preservation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 23 (3), e13334. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.13334 (2024).

Rifna, E. J., Misra, N. N. & Dwivedi, M. Recent advances in extraction technologies for recovery of bioactive compounds derived from fruit and vegetable waste peels: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63 (6), 719–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1952923 (2023).

Kola, V. & Carvalho, I. S. Plant extracts as additives in biodegradable films and coatings in active food packaging. Food Biosci. 54, 102860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102860 (2023).

Ajila, C. M., Naidu, K. A., Bhat, S. G. & Rao, U. J. S. P. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential of Mango Peel extract. Food Chem. 105 (3), 982–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.052 (2007).

Bhargava, N., Sharanagat, V. S., Mor, R. S. & Kumar, K. Active and intelligent biodegradable packaging films using food and food Waste-Derived bioactive compounds: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 105, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.015 (2020).

Sheibani, S. et al. Sustainable strategies for using natural extracts in smart food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 267, 131537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131537 (2024).

Suleria, H. A. R., Barrow, C. J. & Dunshea, F. R. Screening and characterization of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant capacity in different fruit peels. Foods 9 (9), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091206 (2020).

Sogi, D. S. et al. Antioxidant Activity, and functional properties of ‘Tommy atkins’ Mango Peel and kernel as affected by drying methods. Food Chem. 141 (3), 2649–2655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.053 (2013).

Pandey, V. K. et al. Production of biodegradable food packaging from Mango Peel via enzymatic hydrolysis and polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis: A review on microbial intervention. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 7, 100292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100292 (2024).

Moreira, D., Gullón, B., Gullón, P., Gomes, A. & Tavaria, F. Bioactive packaging using antioxidant extracts for the prevention of microbial Food-Spoilage. Food Funct. 7 (7), 3273–3282. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6FO00553E (2016).

Vargas-Torrico, M. F., Aguilar-Méndez, M. A., Ronquillo-de Jesús, E., Jaime-Fonseca, M. R. & von Borries-Medrano, E. Preparation and characterization of Gelatin-Carboxymethylcellulose active film incorporated with pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peel extract for the preservation of raspberry fruit. Food Hydrocoll. 150, 109677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109677 (2024).

Yong, H. & Liu, J. Active packaging films and edible coatings based on Polyphenol-Rich propolis extract: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 20 (2), 2106–2145. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12697 (2021).

Adilah, A. N., Jamilah, B., Noranizan, M. A. & Hanani, Z. A. N. Utilization of Mango Peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 16, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2018.01.006 (2018).

Farouk, A. Towards sustainable food packaging films using cellulose acetate and polyvinylidene fluoride matrix enriched with Mango Peel extract. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14 (7), 8957–8978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04986-0 (2024).

Gupta, P., Toksha, B. & Rahaman, M. A. Review on biodegradable packaging films from vegetative and food waste. Chem. Rec. 22 (7), e202100326. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202100326 (2022).

Kanatt, S. R. & Chawla, S. P. Shelf life extension of chicken packed in active film developed with Mango Peel extract. J. Food Saf. 38 (1), e12385. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfs.12385 (2018).

Susmitha, A., Sasikumar, K., Rajan, D., Padmakumar, M. & Nampoothiri, A. Development and characterization of corn Starch-Gelatin based edible films incorporated with Mango and pineapple for active packaging. Food Biosci. 41, 100977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100977 (2021).

do Sobral, A., dos Santos, P. J. & García, J. S. Effect of protein and plasticizer concentrations in film forming solutions on physical properties of edible films based on muscle proteins of a Thai tilapia. J. Food Eng. 70 (1), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.09.015 (2005).

Priyadarshi, R., Sauraj Kumar, B. & Negi, Y. S. Chitosan film incorporated with citric acid and glycerol as an active packaging material for extension of green Chilli shelf life. Carbohydr. Polym. 195, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.089 (2018).

Dutra, E. A.; Oliveira, D. A. G. D. C.; Kedor-Hackmann, E. R. M.; Santoro, M. I. R. M. Determination of Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of Sunscreens by Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Farm. 2004, 40 (3), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-93322004000300014.

Sayre, R. M., Agin, P. P., LeVee, G. J. & Marlowe, E. A. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro testing of sunscreening formulas. Photochem. Photobiol. 29 (3), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1979.tb07090.x (1979).

Siripatrawan, U. & Harte, B. R. Physical properties and antioxidant activity of an active film from Chitosan incorporated with green tea extract. Food Hydrocoll. 24 (8), 770–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.04.003 (2010).

Rolińska, K., Jakubowska, E., Żmieńko, M. & Łęczycka-Wilk, K. Choline Chloride-Based deep eutectic solvents as plasticizer and active agent in Chitosan films. Food Chem. 444, 138375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138375 (2024).

Heaysman, C. L., Philips, G. J., Lloyd, A. W. & Lewis, A. L. Unusual behaviour induced by phase separation in hydrogel microspheres. Acta Biomater. 53, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.013 (2017).

Mandal, A. & Chakrabarty, D. Studies on the Mechanical, Thermal, morphological and barrier properties of nanocomposites based on Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) and nanocellulose from sugarcane Bagasse. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 20 (2), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2013.05.003 (2014).

Jakubowska, E., Gierszewska, M., Szydłowska-Czerniak, A., Nowaczyk, J. & Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E. Development and characterization of active packaging films based on Chitosan, Plasticizer, and Quercetin for repassed oil storage. Food Chem. 399, 133934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133934 (2023).

Shafie, M. H., Yusof, R. & Gan, C. Y. Synthesis of citric acid Monohydrate-Choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents (DES) and characterization of their physicochemical properties. J. Mol. Liq. 288, 111081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111081 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Zhu, P. C. & Edgren, D. Crosslinking reaction of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) with Glyoxal. J. Polym. Res. 17 (5), 725–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-009-9362-z (2010).

Santana, A. P. R. et al. Synthesis of natural deep eutectic solvents using a mixture design for extraction of animal and plant samples prior to ICP-MS analysis. Talanta 216, 120956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2020.120956 (2020).

Mansur, H. S., Sadahira, C. M., Souza, A. N. & Mansur, A. A. P. FTIR spectroscopy characterization of Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) hydrogel with different hydrolysis degree and chemically crosslinked with glutaraldehyde. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 28 (4), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2007.10.088 (2008).

Homthawornchoo, W., Hakimi, N. F. S. M., Romruen, O. & Rawdkuen, S. Dragon fruit Peel extract Enriched-Biocomposite wrapping film: characterization and application on coconut milk candy. Polymers 15 (2), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15020404 (2023).

Azlim, N. A. et al. Fabrication and characterization of a pH-Sensitive intelligent film incorporating Dragon fruit skin extract. Food Sci. Nutr. 10 (2), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2680 (2022).

Pramitasari, R., Gunawicahya, L. N. & Anugrah, D. S. B. Development of an indicator film based on cassava Starch–Chitosan incorporated with red Dragon fruit Peel anthocyanin extract. Polymers 14 (19), 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194142 (2022).

Meng, S. et al. Efficient corrosion Inhibition by sugarcane purple rind extract for carbon steel in HCl solution: mechanism analyses by experimental and in Silico insights. RSC Adv. 11 (50), 31693–31711. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA04976C (2021).

Fan, B. et al. Fabrication, characterization and efficient surface protection mechanism of Poly(Trans-Cinnamaldehyde) electropolymerized coatings for EH36 steel in simulated seawater. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 629, 127434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127434 (2021).

Martin, A. 4.4 Lab Colour Space and Delta E Measurements. (2015).

Almeida, C. M. R., Magalhães, J. M. C. S., Souza, H. K. S. & Gonçalves, M. P. The role of choline Chloride-Based deep eutectic solvent and Curcumin on Chitosan films properties. Food Hydrocoll. 81, 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.03.025 (2018).

Jakubowska, E., Gierszewska, M., Nowaczyk, J. & Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E. The role of a deep eutectic solvent in changes of physicochemical and antioxidative properties of Chitosan-Based films. Carbohydr. Polym. 255, 117527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117527 (2021).

Hopkins, E. J., Chang, C., Lam, R. S. H. & Nickerson, M. T. Effects of flaxseed oil concentration on the performance of a soy protein Isolate-Based Emulsion-Type film. Food Res. Int. 67, 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.11.040 (2015).

Shojaee-Aliabadi, S. et al. Characterization of Antioxidant-Antimicrobial κ-Carrageenan films containing Satureja hortensis essential oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 52, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.08.026 (2013).

Kuchaiyaphum, P., Chotichayapong, C., Kajsanthia, K. & Saengsuwan, N. Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) based active film incorporated with tamarind seed coat waste extract for food packaging application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 255, 128203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128203 (2024).

Gasti, T. et al. Physicochemical and antibacterial evaluation of Poly (Vinyl Alcohol)/Guar Gum/Silver nanocomposite films for food packaging applications. J. Polym. Environ. 29 (10), 3347–3363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-021-02123-4 (2021).

Zehra, K., Nawab, A., Alam, F., Hadi, A. & Raza, M. Development of novel biodegradable water chestnut Starch/PVA composite Film. Evaluation of plasticizer effect over Physical, Barrier, and mechanical properties. J. Food Process. Preserv. 46 (3), e16334. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.16334 (2022).

Chousidis, N. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-Based films: insights from crosslinking and plasticizer incorporation. Eng. Res. Express. 6 (2), 025010. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ad4cb4 (2024).

Youssef, A. M. & El-Sayed, S. M. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 193, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.03.088 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Moisture and oxygen barrier properties of cellulose Nanomaterial-Based films. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6 (1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03523 (2018).

Lu, Q. H. & Zheng, F. Chapter 5 - Polyimides for electronic applications. In Advanced Polyimide Materials; (ed Yang, S. Y.) Elsevier, 195–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812640-0.00005-6. (2018).

Soroka, W. Fundamentals of Packaging Technology, 2nd edition.; Inst of Packaging Professionals, (1999).

Barbato, A. et al. Biodegradable films with Polyvinyl Alcohol/Polylactic Acid + Wax double coatings: influence of relative humidity on transport properties and suitability for modified atmosphere packaging applications. Polymers 15 (19), 4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15194002 (2023).

Kader, A. A., Zagory, D., Kerbel, E. L. & Wang, C. Y. Modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 28 (1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398909527490 (1989).

Lee, D. S. Carbon dioxide absorbers for food packaging applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 57, 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2016.09.014 (2016).

Moradi, M. et al. Characterization of antioxidant Chitosan film incorporated with Zataria multiflora Boiss essential oil and grape seed extract. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 46 (2), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011.11.020 (2012).

Lawal, K. G., Nazir, A., Sundarakani, B., Stathopoulos, C. & Maqsood, S. Unveiling the effect of natural deep eutectic Solvents-Based date seed polyphenolic extract on the properties of Chitosan-PVA films and its application in shrimp packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 280, 135593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135593 (2024).

Rong Huei, C. & Hwa, H. D. Effect of molecular weight of Chitosan with the same degree of deacetylation on the Thermal, Mechanical, and permeability properties of the prepared membrane. Carbohydr. Polym. 29 (4), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(96)00007-0 (1996).

Shafie, M. H., Samsudin, D., Yusof, R. & Gan, C. Y. Characterization of Bio-Based plastic made from a mixture of Momordica Charantia bioactive polysaccharide and choline Chloride/Glycerol based deep eutectic solvent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 118, 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.103 (2018).

Atarés, L. & Chiralt, A. Essential oils as additives in biodegradable films and coatings for active food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 48, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.12.001 (2016).

Kumar, P. et al. Pineapple Peel extract incorporated Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)-Corn starch film for active food packaging: Preparation, characterization and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 187, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.136 (2021).

Alexy, P., Káchová, D., Kršiak, M., Bakoš, D. & Šimková, B. Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) stabilisation in thermoplastic processing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 78 (3), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00177-5 (2002).

Pang, S. C., Chin, S. F., Tay, S. H. & Tchong, F. M. Starch–Maleate–Polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels with controllable swelling behaviors. Carbohydr. Polym. 84 (1), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.12.002 (2011).

Thohari, I., Apriliyani, M. W., Rachmawati, A., Ningsih, E. N. R. & Aminuzzuhriyah, P. M. Physical quality and microstructure of Casein-Sodium tripholyphosphate edible film making. Atlantis Press. 147–154 https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-116-6_19 (2023).

Parit, M., Du, H., Zhang, X., Jiang, Z. & Flexible, Transparent, U. V. P. Water-Resistant nanocomposite films based on Polyvinyl alcohol and kraft Lignin-Grafted cellulose nanofibers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4 (5), 3587–3597. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.2c00157 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Remadevi, R., Hinestroza, J. P., Wang, X. & Naebe, M. Transparent ultraviolet (UV)-Shielding films made from waste hemp hurd and Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Polymers 12 (5), 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12051190 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Preparation of Biochar by Mango Peel and its adsorption characteristics of Cd(II) in solution. RSC Adv. 10 (59), 35878–35888. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA06586B (2020).

Ojeda, G. A., Sgroppo, S. C., Sánchez-Moreno, C. & de Ancos, B. Mango ‘Criollo’ by-Products as a source of polyphenols with antioxidant Capacity. Ultrasound assisted extraction evaluated by response surface methodology and HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS characterization. Food Chem. 396, 133738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133738 (2022).

Tariq, A. et al. Extraction of dietary fiber and polyphenols from Mango Peel and its therapeutic potential to improve gut health. Food Biosci. 53, 102669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102669 (2023).

Annu; Ali, A. & Ahmed, S. Eco-Friendly natural extract loaded antioxidative Chitosan/Polyvinyl alcohol based active films for food packaging. Heliyon 7 (3), e06550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06550 (2021).

Grillo, G., Gunjević, V., Radošević, K., Redovniković, I. R. & Cravotto, G. Deep eutectic solvents and nonconventional technologies for Blueberry-Peel extraction: Kinetics, anthocyanin Stability, and antiproliferative activity. Antioxidants 9 (11), 1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111069 (2020).

Jeliński, T., Przybyłek, M. & Cysewski, P. Natural deep eutectic solvents as agents for improving Solubility, stability and delivery of Curcumin. Pharm. Res. 36 (8), 116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-019-2643-2 (2019).

Talón, E. et al. Antioxidant edible films based on Chitosan and starch containing polyphenols from thyme extracts. Carbohydr. Polym. 157, 1153–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.10.080 (2017).

Al-Dairi, M., Pathare, P. B. & Al-Yahyai, R. Chemical and nutritional quality changes of tomato during postharvest transportation and storage. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 20 (6), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2021.05.001 (2021).

Anthon, G. E., LeStrange, M. & Barrett, D. M. Changes in pH, Acids, sugars and other quality parameters during extended vine holding of ripe processing tomatoes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 91 (7), 1175–1181. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4312 (2011).

Marcillo-Parra, V., Anaguano, M., Molina, M., Tupuna-Yerovi, D. S. & Ruales, J. Characterization and quantification of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in three different varieties of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Peel from the Ecuadorian region using HPLC-UV/VIS and UPLC-PDA. NFS J. 23, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nfs.2021.02.001 (2021).

Quintana, S. E., Salas, S. & García-Zapateiro, L. A. Bioactive compounds of Mango (Mangifera Indica): A review of extraction technologies and chemical constituents. J. Sci. Food Agric. 101 (15), 6186–6192. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11455 (2021).

Suganthi, S., Vignesh, S., Kalyana Sundar, J. & Raj, V. Fabrication of PVA polymer films with improved antibacterial activity by Fine-Tuning via organic acids for food packaging applications. Appl. Water Sci. 10 (4), 100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-1162-y (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by statutory founds of Łukasiewicz Research Network – Industrial Chemistry Institute, Poland (grant number: 841313). Research equipment for barrier and wetting properties was purchased as part of the “Food and Nutrition Centre - modernisation of the SGGW campus to create a Food and Nutrition Research and Development Centre (CŻiŻ)” co-financed by the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund under the Regional Operational Programme of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship for 2014-2020 (Project No. RPMA.01.01.00-14-8276/17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Katarzyna Łęczycka-Wilk: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Brian Kaczmarczyk: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Ewelina Jakubowska: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Karolina Rolińska: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Monika Janowicz: Resources, Investigation. Sabina Galus: Resources, Investigation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Łęczycka-Wilk, K., Kaczmarczyk, B., Jakubowska, E. et al. Deep eutectic solvents and mango peel extract as active ingredients of Pva films. Sci Rep 15, 39065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25913-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25913-5

) OTR and (

) OTR and ( ) CO2TR results for PVA-based films. Mean values with standard deviations. Different superscript letters (a-c) within the same column indicate significant differences between the films (p < 0.05).

) CO2TR results for PVA-based films. Mean values with standard deviations. Different superscript letters (a-c) within the same column indicate significant differences between the films (p < 0.05).

) for the temperature at which a 5% mass loss is observed T5%, (

) for the temperature at which a 5% mass loss is observed T5%, ( ) for a 10% mass loss T10% and (

) for a 10% mass loss T10% and ( ) for a 50% mass loss T50%.

) for a 50% mass loss T50%.

) PVA, (

) PVA, ( ) PVA/MPE, (

) PVA/MPE, ( ) PVA/CA/MPE, (

) PVA/CA/MPE, ( ) PVA/MA/MPE and (

) PVA/MA/MPE and ( ) PVA/GA/MPE films.

) PVA/GA/MPE films.

) day 0, (

) day 0, ( ) day 5, (

) day 5, ( ) day 12, (

) day 12, ( ) day 22.

) day 22.