Abstract

Forecasting chaotic systems using machine learning has become highly sought after due to its potential applications in predicting climate and weather phenomena, stock market indices, and pathological activity in biomedical signals. However, existing solutions, such as neural network-based reservoir computing (RC) and long-short-term memory (LSTM), contain numerous model hyperparameters that must be tuned, often requiring high computational resources and large training datasets. Here, we propose a computationally simpler regression tree ensemble-based technique to predict the temporal evolution of chaotic systems in data-driven environments. Furthermore, we introduce a heuristic procedure to prescribe hyperparameters through automated statistical analysis of training data, which eliminates the need for the user to perform hyperparameter tuning. We investigate the efficacy of the proposed hyperparameter prescription procedure through numerical experiments. Lastly, we demonstrate the state-of-the-art performance of our proposed approach on several benchmark tasks, including the Southern Oscillation Index, a crucial but noisy climate time series with limited samples, to illustrate its effectiveness in real-world settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in machine learning techniques have enabled the prediction of the temporal evolution of chaotic systems in entirely data-driven settings, without requiring prior knowledge of the governing equations1,2,3. These model-free approaches represent a significant breakthrough in modeling and analyzing complex systems and have transformative implications for various fields of science and technology1,2,3,4,5. Deep learning techniques such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and, more specifically, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) provide substantial performance in forecasting chaotic systems, likely due to their ability to capture fading short-term memory4,6,7,8,9. However, RNN and LSTM are computationally expensive models, and require both the tuning of hyperparameters and a significant amount of training data to provide accurate forecasts. Reservoir computing (RC) reduces computational expense and eliminates the need for large training data sets by randomizing the recurrent pool of nodes within an RNN (called the reservoir), which reduces training to a linear optimization problem4,9. Despite RC’s improvements to RNN and LSTM, the broader acceptance of these model-free approaches remains challenging, since their real-world implementation requires tuning many hyperparameters. This computationally intensive process also introduces subjective choices in modeling.

The recently developed Next Generation Reservoir Computing (NG-RC) converts RC into a mathematically equivalent nonlinear vector autoregression (NVAR) machine, which further improves RC by reducing the number of necessary hyperparameters and removing the need for a randomized reservoir2,10. The NG-RC methodology, while promising, does not eliminate the need for hyperparameter tuning, rendering it unappealing for automated applications. Furthermore, while the nonlinear readout of NG-RC allows for accurate prediction of chaotic data, it may become prohibitive when the supplied training data has a high spatial dimension. Additionally, NG-RC and the aforementioned methods do not provide an optimal selection of time delays and lag intervals, which are essential for accurate forecasting of chaotic data but expensive to tune if repeated model training is required (such as in a hyperparameter grid search). Recent advances in RC hyperparameter tuning (and machine learning models in general), such as Bayesian optimization, substantially improve the stability and effectiveness of hyperparameter tuning11,12,13. However, such improvements do not completely eliminate the necessity of hyperparameter tuning in practice, motivating the need for a high-fidelity alternative that does not require hyperparameter tuning.

Tree-based models are extensively used in machine learning due to their remarkable adaptability, versatility, and robustness. These models require only a limited number of hyperparameters, making them an ideal choice for many applications14,15. Additionally, due to the nature of tree-based models to partition feature space into regions which produce similar output, one may argue that tree-based methods are more interpretable than neural network-based approaches. Furthermore, recent work that has generated much excitement in machine learning communities demonstrates the benefits of tree-based machine learning models, such as XGBoost and Random Forests (RF), over deep learning models on tabular data, both in terms of accuracy and computational resources15,16,17,18. Inspired by these recent advances, we investigate tree-based regression as an alternative to the above-mentioned neural network approaches to develop a low complexity yet high-fidelity method for forecasting chaotic data without the need for hyperparameter tuning.

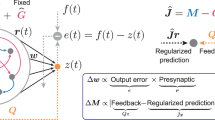

Summary of TreeDOX training (a) and self-evolved prediction (b). Here, \({\bf x}_i\in \mathbb {R}^D\) represents each input sample, k is the time delay overmbedding dimension, and \(\xi\) is the embedding time lag. When running TreeDOX in batched prediction mode (such as when performing ‘lead’ predictions where, at each iteration, the model is given train/test data and is requested to make a prediction a given number of time points ahead), the feedback loop may be ignored. Instead, a batch of respective \({\bf s}_\text {reduced}\) vectors is constructed in advance and fed into the model simultaneously.

In this work, we introduce a tree-based alternative for learning chaos, eliminating the need for hyperparameter tuning. Furthermore, we present a detailed analysis of the efficacy of this novel approach and show that it outperforms existing methods in accuracy, user-friendliness, and computational simplicity. We name this tree-based method TreeDOX: Tree-based Delay Overembedded eXplicit memory learning of chaos. TreeDOX mimics the implicit fading short-term memory of RNN, LSTM, RC, and NG-RC via explicit short-term memory in the form of time delay overembedding. This overembedding differs from the traditional time-delay embedding due to its intentional usage of a higher embedding dimension than that suggested by Takens’ theorem, which helps to model nonstationary dynamical systems19,20,21,22. TreeDOX uses an ensemble tree method called Extra Trees Regression (ETR) and uses the inherent Gini feature importance of ETR to perform feature reduction on the time delay overembedding23, reducing computational resource usage and improving generalizability. We demonstrate the efficacy of TreeDOX on several chaotic systems, including the Hẽnon map, Lorenz and Kuramoto-Sivashinsky systems, and a real-world chaotic dataset: the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI).

Results

Here, we describe the inner workings of TreeDOX (including training, inference, and hyperparameter prescription) and demonstrate its efficacy on a variety of test cases, the first few of which use toy models to validate performance. Firstly, we test TreeDOX on a discrete chaotic system: the Hénon map. We show that TreeDOX can recreate the Hénon chaotic attractor, verifying the ability of TreeDOX to capture long-term dynamics in general. Next, we apply TreeDOX to a prototypical continuous chaotic system: the Lorenz system. Aside from showing its ability to recreate the respective chaotic attractor, we show that TreeDOX can make short-term, self-evolved forecasts with a level of accuracy similar to state-of-the-art machine learning methods. The last toy model, the Kuramoto-Sivashinsky system, is used to demonstrate TreeDOX’s ability to understand data with high spatial dimension, where the respective data uses \(D=64\) dimensions to discretize the spatial domain. Next, we utilize real-world data to demonstrate TreeDOX’s effectiveness in a real-world scenario, specifically the open-loop prediction of a given number of time steps in advance. For this purpose, we use the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) data due to its level of noise and lack of large data volume, unlike the above toy models24,25. We demonstrate that for an array of lead values (i.e., the number of steps in advance to make predictions), the accuracy and speed of TreeDOX rival those of its neural network-based competitors, and also that TreeDOX requires less training data. Lastly, we vary the few hyperparameters introduced in the method and make SOI predictions to demonstrate not only the low sensitivity of TreeDOX to these hyperparameters but also that our proposed hyperparameter prescription schemes achieve the best possible accuracy out of TreeDOX while avoiding further diminishing returns in computational speed. Note that in all results that compare TreeDOX with current methods, the methods feature hyperparameter tuning via Tree-structure Parzen Estimators (TPE), a Bayesian optimization scheme26. 25 samples are used when performing the TPE hyperparameter tuning.

Rationale behind extra trees

While TreeDOX could certainly use the recently popular XGBoost form of tree-based regression, we opt instead for the classical Random Forest due to its typically successful performance under default hyperparameter values, such as the number of trees in the ensemble27,28,29. TreeDOX uses a variant of Random Forests called an Extra-Trees Regression (ETR)23. The ETR algorithm is an ensemble-based learning method in which each decision tree is constructed using all training samples of the data, rather than bootstrapping. Unlike the standard Random Forest method, where all the attributes are used to determine the locally optimal split of a node, a random subset of features is selected for a node split in an ETR23. For each feature in the random subset, a set of random split values is generated within the range of the training data for the given feature, and a loss function (usually mean square error) is calculated for each random split. The feature-split pair that results in the lowest value of the given loss function is selected as the node. For every testing sample, each tree predicts the output value independently, and the final output value of the ETR is the mean of all predictions of the trees. Here, the regression trees that comprise each predictor in the ensemble can understand nonlinear data due to their nature as piecewise constant predictors. Therefore, with enough depth, regression trees can predict nonlinear data with approximate smoothness. Ensembles of sufficiently many regression trees, such as ETR discussed here, can predict nonlinear data more smoothly than individual trees via averaging over the ‘stepping’ effect of the piecewise constant response of the trees.

Apart from calculating testing accuracy, ETRs also quantify the importance of each feature using mean decrease impurity, also known as Gini importance. Another advantage of ETR is its resilience to correlated features and the value of hyperparameters, such as the number of trees in the ensemble, minimum samples per leaf, or max depth of the individual trees. Often, the prescribed hyperparameters will achieve an acceptable regression; instead, the impact of such hyperparameters is felt in the space and time complexity of the algorithm, as training complexity scales linearly with both the number of trees and the number of variables encountered during splitting. ETRs have two advantages over RFs: (1) lower time complexity and variance due to the randomized splits and (2) lower bias due to the lack of bootstrapping. While ETRs are more expensive to train compared to RC, they do not require an expensive grid search to find hyperparameters and tend to be just as fast when making predictions. However, unlike RC and other state-of-the-art methods, ETRs do not contain explicit memory of system variables. Instead, the use of delay overembedding provides explicit memory to the model.

TreeDOX training and prediction

TreeDOX uses two ETRs—one whose role is to calculate feature importances and another whose role is to perform predictions using reduced features. Before we formally introduce TreeDOX, we will first define key concepts. First, assume that D-dimensional spatiotemporal data is in the following form: \({\displaystyle X = \{{\bf x}_i\}_{i=1}^{t}}\) where \({\bf x}_i \in \mathbb {R}^D\) and t is the length of the temporal component. A time delay overembedding of X will be denoted in the following manner: \({DO(X ~|~ k,\xi ) = \{[{\bf x}_i, {\bf x}_{i+\xi }, \dots , {\bf x}_{i+(k-1)\xi }]\}_{i=1}^{t-(k-1)\xi -1}}\) where \(k\in \mathbb {N}\) is the overembedding dimension and \(\xi \in \mathbb {N}\) is the time lag between observations in the time delay overembedding. We suggest a procedure to prescribe the values of k and \(\xi\) below. We start by constructing the set of features and labels used in training, denoted by \({F = \{{\bf f}_i\}_{i=1}^{t-(k-1)\xi -1} = DO(X~|~k,\xi )}\) and \({L = \{{\bf l}_i\}_{i=1}^{t-(k-1)\xi -1} = \{{\bf x}_{i+(k-1)\xi +1}\}_{i=1}^{t-(k-1)\xi -1}}\), respectively. After training ETR #1 on (F, L) we request the feature importances \({\bf FI} = \{FI_j\}_{j=1}^{kD}\) representing the mean Gini importance (across all trees in the ensemble) of the kD columns in the flattened time delay overembedding features, which captures an essence of predictive ability for each time lag. We introduce one hyperparameter, \(p\in \mathbb {N}\), whose prescription is described below. We construct a set \({C=\mathop {\mathrm {arg\,max}}\limits _{\bar{C}} \sum _{j\in \bar{C}} FI_j}\), where \(\bar{C} \subset \{1,2,\dots ,kD\}\) and \(|\bar{C}|=p\). In other words, C contains the indices of the greatest p entries in \({\bf FI}\), and represents the columns of F we wish to use in final training since ETR #1 finds their respective time delays to hold the most predictive power. Next we construct a new set of reduced features, \(F' = \{({\bf f}_{i,j})_{j\in C}\}_{i=1}^{t-(k-1)\xi -1}\), where \({\bf f}_{i,j}\) represents the j-th column in the row vector \({\bf f}_i\). Lastly, we train ETR #2 on \((F',L)\), which benefits from faster training and increased generalizability due to the feature reduction.

At the beginning of the forecasting stage of TreeDOX, a vector \({{\bf s} = [{\bf x}_{t-(k-1)\xi }, {\bf x}_{t-(k-1)\xi +1}, \dots , {\bf x}_{t}]}\) is initialized from the end of the training data and another vector \({{\bf s}_{\text {delayed}} = ({\bf s}_j)_{j\in E} = [{\bf x}_{t-(k-1)\xi }, {\bf x}_{t-(k-2)\xi }, \dots , {\bf x}_{t}]}\) is collected from \({{\bf s}}\), where \({E=\{1, 1+\xi , \dots , 1+(k-1)\xi \}}\). \({{\bf s}_{\text {reduced}} = ({\bf s}_{\text {delayed},j})_{j\in C}}\) is treated as a sample for the feature-reduced ETR (ETR #2) from which a prediction of \({\bf x}_{t+1}\), \(\tilde{{\bf x}}_{t+1}\) is extracted. \({\bf s}\) is updated to remove the first element and append the prediction \(\tilde{{\bf x}}_{t+1}\) to the end. The updated \({\bf s}\) vector is used to repeat the process, hence the self-evolutionary nature of TreeDOX forecasting. Diagrams in Fig. 1 summarize the training and forecasting stages of TreeDOX. Since the training of ETR #1 uses all available time lags in the delay overembedding and is merely used to estimate the predictive power of each time lag, we suggest limiting the number of trees in the ensemble to reduce training time when using large training sets. However, due to the usually fast training of ETR #2 as a result of reduced features, it is beneficial to use a greater number of trees to decrease the bias in predictions, and only marginally increase training time.

Hyperparameter selection procedure

There exist three hyperparameters introduced in TreeDOX that are not otherwise prescribed by standard ETR implementations: dimension, k, and lag, \(\xi\), of the delay overembedding, and the number of final features to use, p. To remove the responsibility of hyperparameter tuning from the TreeDOX user, we wish to leverage the existing training data to prescribe the values of k, \(\xi\), and p. Here, we propose a heuristic procedure to select hyperparameter values that showed consistent success in the numerical experiments outlined later.

Delay overembedding hyperparameters (k and \(\xi\))

To prescribe values for k and \(\xi\), we must investigate their role in the time delay overembedding. Since the time delay overembedding has dimension k and lag \(\xi\), one may consider that there are moving windows of length \((k-1)\xi\) (the earliest point in the time delay overembedding) used to train TreeDOX. We use Average Mutual Information (AMI) between the training data and its delayed copy shifted by \(\tau\) states to determine how much information about the current state is stored in the previous states. We propose the following procedure: (1) calculate \(AMI_i(\tau )\) for \(\tau \le \tau _{max}\), where \(AMI_i(\tau )\) is the AMI of the i-th dimension of training data and its copy shifted by \(\tau\) states and \(\tau _{max}\) (say 10% of the training length) is simply an arbitrary limit to avoid unnecessary calculation—\(\tau _{max}\) will roughly correlate to the maximum number of training features the user desires for each data dimension; (2) select a quantile threshold of \(AMI_i(\tau )\), such as 0.5—while it may initially appear unintuitive, our suggestion of 0.5 as a quantile of \(AMI_i(\tau )\) will allow TreeDOX to avoid arbitrarily large overembedding dimension when a system has slowly fading memory; (3) optionally measure the local maxima of \(AMI_i(\tau )\); (4) take \(\tau _{i,crit}\) to be the smallest such \(\tau\) such that \(AMI_i(\tau )\) drops below the calculated quantile; (5) if local maxima were calculated and \(\tau _{i,crit}\) is less than the \(\tau\) of the first maxima, take \(\tau _{i,crit}\) to instead be the first maxima—this will force the time delay overembedding to take the marginally increased system memory given by the gap between the initial \(\tau _{i,crit}\) and the first local maxima into account. According to this procedure, \(\tau _{i,crit}\) will estimate the time delay at which the system does not contain sufficient memory to have predictive power of the next state. Therefore, we suggest choosing \((k-1)\xi\) to be the maximum value of the set of critical \(\tau\)’s, so that one may force the time delay overembedding to remain in the region where the system retains information about its next state. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for a visualization of the procedure to calculate \(\tau _{i,crit}\). The choice of \(\xi\) made to specify a value for k from the prescribed \((k-1)\xi\) is a much simpler one: the smaller \(\xi\), the more computational resources needed to train TreeDOX—one may think of \(\xi\) as a subsampling hyperparameter, where the larger \(\xi\), the less data the model is fed. Thus, if one has a powerful enough computer, one should choose \(\xi =1\) and thus \(k = \max _{1 \le i \le D}(\tau _{i,crit})+1\). Otherwise, choose a large enough \(\xi\) such that training is a reasonable task and

Feature reduction hyperparameter (p)

To prescribe a value for p, we next investigate the features fed to the ETR. After training ETR#1, we request the impurity-based feature importances (FIs), also known as the Gini feature importance, to be calculated, which ranks the kD features according to their respective reduction of the specified loss function (mean square error, in our case). Gini importance is defined on a tree-level basis, meaning each tree in the regression ensemble captures its own estimation of the importance of each feature. Therefore, a convenient and natural extension is to consider the statistical properties of feature importance samples.To keep consistent with the ethos of TreeDOX to make as few assumptions about data as possible, we propose a nonparametric bootstrapping approach to feature selection. We are testing the null hypothesis \(H_0:~\mu \le FI_0\) and alternate hypothesis \(H_1:~\mu > FI_0\), where \(\mu\) is the population mean of Gini importance for a given feature and \(FI_0\) is the median of the Gini importance values averaged across all trees in ETR#1. \(FI_0\) is chosen such that we select only those features with Gini importance that are (statistically) significantly greater than that of the majority of other features. For each feature, we bootstrap (with replacement) a large number of samples (taken to be 2,500 by default) from the set of Gini importance estimates across all trees in ETR#1, where the length of each bootstrapped sample is equal to the number of trees in ETR#1. Then, we calculate the mean of each sample and approximate the p-value of the associated hypothesis test to be the proportion of bootstrapped samples whose mean is less than or equal to \(FI_0\). The features with an estimated p-value less than 0.05 are considered important enough to pass through the feature selection filter. In all displayed TreeDOX results, we employ the suggested methods for prescribing k, \(\xi\), and p. See Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for visualizations of hyperparameter prescription in practice.

Discrete system

As a prototypical discrete chaotic system, the Hénon map is used to verify that TreeDOX can recreate chaotic dynamics. We generate training data from the Hénon map, \((x_{n+1}, y_{n+1}) = (1 - ax_n^2 + y_n, bx_n)\), where \(a=1.4\), \(b=0.3\), and \((x_0,y_0)=(0,0)\). 25, 000 and 50, 000 training and testing points are used, respectively. Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=16\) according to Eqn. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=13\) of \(kD=32\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). Fig. 2 displays the trajectories of both the test and predicted data. We compare the complexity of the resulting chaotic attractors via correlation dimension, \(D_2\)30, which necessitates a large test set for numerical stability purposes. Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 show similar results for the logistic map, another archetypal discrete dynamical system. While these findings are not essential for demonstrating the effectiveness of TreeDOX, they do offer valuable insights, including a detailed recreation of the logistic map’s bifurcation diagram.

Test and predicted Hénon map attractors, respectively, with \(a=1.4\) and \(b=0.3\). Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=16\) according to Eq. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=13\) of \(kD=32\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). \(D_2\) is the correlation dimension of the respective attractor. Here, 25,000 and 50,000 training and testing samples were used.

Continuous system

The next benchmark we use is the Lorenz system, a prototypical continuous chaotic system: \({(\dot{x}, \dot{y}, \dot{z}) = (\sigma (y-x), x(\rho -z)-y, xy-\beta z)}\)31. Due to multiple nonlinear terms in the generating dynamics, a simple round-off error is enough to cause computational Lorenz system forecasts to diverge quickly, making the numerical forecasting of the system difficult. We select the typical parameters \(\sigma = 10\), \(\beta = 8/3\), and \(\rho = 28\). For both Figs. 3 and 4 RK45 is used to generate training and testing data, where \([x_0, y_0, z_0]=[1,1,1]\) and \(dt=0.01\). Fig. 3 uses 25,000 and 50,000 training and testing points, respectively, and Fig. 4 uses 25,000 and 1,500 training and testing points, respectively. Note that in Fig. 4 a greatest Lyapunov exponent of \(\lambda _{max}=0.8739\) is assumed32. Fig. 3 demonstrates TreeDOX’s ability to predict long-term dynamics, while Fig. 4 portrays TreeDOX’s self-evolved forecast accuracy in comparison to current methods.

(a,b) Test and predicted Lorenz system attractors, respectively, with \(\sigma = 10\), \(\beta = 8/3\), and \(\rho = 28\). Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=109\) according to Eq. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=136\) of \(kD=327\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). \(D_2\) is the correlation dimension of the respective attractor. Here, 25,000 and 50,000 training and testing samples were used.

Summary of Lorenz system forecasts with \(\sigma = 10\), \(\beta = 8/3\), \(\rho = 28\), displayed using Lyapunov time, where \(\lambda _{max}=0.8739\). Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=56\) according to Eq. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=75\) of \(kD=168\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). Test data is black while RNN, LSTM, RC, NG-RC, and TreeDOX are light blue, blue, light green, green, and red, respectively. (a,b,c) x, y, and z coordinates, respectively. (d) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of x, y and z forecasted versus test data. Here, 25,000 and 1,500 training and testing samples were used.

Spatiotemporal system

Next, we test TreeDOX on a chaotic spatiotemporal system by forecasting the Kuramoto–Sivashinsky (KS) system: \(u_t + u_{xxxx} + u_{xx} + uu_x = 0\), where \(x\in [0, L]\). To generate the training and testing data, we used length \(L = 22\) and \(D = 64\) grid points to discretize the domain, then used the exponential time-differencing fourth-order Runge–Kutta (ETDRK4) method to evolve the system for 50,000 iterations with \(\Delta t=0.25\), random initial data, and periodic boundary conditions1,33. After removing 2,000 transient points, we use 46,837 points for training and 1,162 points for testing. This was done to produce 12.5 Lyapunov time for the testing phase, assuming \(\lambda _{max}=0.043\)34. Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=26\) according to Eq. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=585\) of \(kD=1,664\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). Fig. 5 demonstrates promising results for predicting spatiotemporal time series such as the Kuramoto–Sivashinsky system, which are comparable to RC results1.

Prediction of Kuramoto–Sivashinsky equation with \(L=22\) and \(D = 64\) grid points. The x-axis shows Lyapunov time, where \(\lambda _{max}=0.043\). Using \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selected \(k=26\) according to Eq. 1. Using \({\bf FI}\) from ETR #1, \(p=585\) of \(kD=1,664\) possible features are greater than \(FI_0\). (a,b) The test and forecasted dynamics, respectively. (c) The difference between the test and forecasted dynamics. Here, there were 46,837 and 1,162 training and testing samples used.

Summary of SOI forecasts, where lead time is 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. RNN, LSTM, RC, NG-RC, and TreeDOX are light blue, blue, light green, green, and red, respectively. Bars represent means, and error bars are \(\pm 1\) standard deviation, where there are 20 realizations of each model. With \(\xi =1\) and a quantile threshold of 0.5, TreeDOX selects \(k=29\) in the AMI-based prescription in Eqn. 1. (a) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between forecasted and test data. (b) Normalized Average Mutual Information (NAMI) between predicted and test data, where the raw AMI values are scaled by the AMI of the test data with itself. (c) Runtime, in seconds, of combined model training and testing, where batch predictions were used when possible. Runtime does not include the grid search for hyperparameter tuning. Note that the hatched regions stacked upon each bar display the testing runtime, while solid sections display training time. Here, there were 1416 and 493 training and testing points used, respectively.

Open-loop prediction results for SOI data where the length of training data is varied, and the test data remains fixed. RNN, LSTM, RC, NG-RC, and TreeDOX are light blue, blue, light green, green, and red, respectively. See legend for respective line and marker styles for TreeDOX, NG-RC, RC, LSTM, and RNN results. Colored areas represent ± 1 standard deviation in results over 20 realizations. Columns 1 through 4 group results by the lead, and rows 1 and 2 display Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Normalized Average Mutual Information (NAMI) between predicted and test, respectively. Row 3 shows the runtime, in seconds, of training and testing (not including hyperparameter tuning).

Real-world dataset

To stress test TreeDOX for a real-world chaotic time series we attempt to forecast the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), a useful climate index with a relationship to the El Niño - La Niña climate phenomena, Walker circulation, drought, wave climate, and rainfall24,35,36,37,38,39,40. SOI is calculated as the z-score of the monthly mean sea level pressure between Tahiti and Darwin24. SOI encodes a high-dimensional chaotic system into one dimension, resulting in unpredictable data which proves difficult for current models to predict41.

Historically recorded SOI data features monthly values from January 1866 to July 202324,25. January 1866 to December 1983 is reserved as training data, while the rest is used for testing, producing 1,416 and 493 training and testing points, respectively. See Supplementary Fig. 5 for a visualization of the SOI data. Due to the difficult nature of forecasting SOI data, TreeDOX and all other models tested are allowed to perform open-loop forecasting, meaning once a model predicts the next value, the correct test value is provided to the model before making the next prediction. To investigate the ability of TreeDOX and other models to make realistic forecasts, each model is trained to predict several months in advance (denoted as ‘lead’ time)42. Fig. 6 displays the SOI prediction results for TreeDOX and other models. See Supplementary Fig. 6 for example 1-month lead forecasts associated with Fig. 6. Lastly, see Supplementary Fig. 7 for rudimentary k-fold predictions, demonstrating the generalizability of TreeDOX.

Discussion

Accuracy

One may observe that for both the Hènon map and Lorenz systems, TreeDOX captures their respective chaotic attractors with a similar correlation dimension. Furthermore, self-evolved TreeDOX forecasts for both the Lorenz system and Kuramoto-Sivashinsky equation show similar accuracy to state-of-the-art methods, such as LSTM and NG-RC, despite its lack of hyperparameter tuning1. Observe in Fig. 4 that TreeDOX (similar to RC and NG-RC) achieves an accurate self-evolved forecast until roughly 9 Lyapunov times. Lastly, open-loop TreeDOX matches the performance of other current models in the prediction of SOI data, with comparably lower RMSE and higher AMI, supporting the ability of TreeDOX’s explicit delay-overembedded memory to capture fading memory similar to that of the implicit memory of LSTM, NG-RC, and other models.

Speed and complexity

While TreeDOX training cannot outperform the linear training scheme of RC and NG-RC, it benefits from computational simplicity and the usage of classical, well-understood regression tree ensemble methods. Additionally, we emphasize that the suggested hyperparameter prescription scheme allows TreeDOX to skip the time-consuming and subjective hyperparameter tuning process involved in other current methods, meaning that in practice, TreeDOX may be faster and more hassle-free than the alternatives. Due to the ensemble nature of ETRs and RFs, each individual regression tree is entirely independent, meaning the potential for GPU-parallelized training exists. Under the RAPIDS ecosystem, cuML’s RandomForestRegressor implements RFs with GPU-parallelization, which provides substantial speedups compared to Scikit-learn’s RandomForestRegressor or ExtraTreesRegressor for users matching the software and hardware requirements43,44,45. Furthermore, the recently developed Hummingbird package allows for trained Scikit-learn tree ensembles to be converted into a tensor equivalent for tree traversal, allowing for very fast model prediction using GPU resources46.

One weakness of TreeDOX lies in the poor computational complexity in regards to the dimensionality of data (and very large training length). Decision trees scale in computational complexity not only with the depth (and thus complexity of data), but also with the number of features and training samples. Since the number of features scales with the dimension of training data, it follows that the computational complexity also scales with the dimension. It is not straightforward to express the computational complexity of decision trees due to their non-fixed training scheme, but it is commonly thought that the complexity scales linearly with depth and the number of features, and super-linearly with the number of samples (usually between \(O(n\log {n})\) and \(O(n^2\log {n})\) where n is the number of samples). Therefore the computational complexity of an ensemble of decision trees is likely between \(O(N_{trees}\cdot {depth}\cdot kDn\log {n})\) and \(O(N_{trees}\cdot {depth}\cdot kDn^2\log {n})\) where \(N_{trees}\) is the number of trees in the ensemble, depth is the average depth of trees, k is the delay overembedding dimension, D is the dimension of training data, and n is the number of samples. However, one may improve runtime for TreeDOX on high-dimensional data (or data with very long training length) by limiting the number of trees in the ensemble and the maximum allowable tree depth.

Sensitivity to hyperparameters in SOI training, where blue triangles are the overembedding dimension, k, orange squares are the successive time lags, \(\xi\), and green pentagons are the number of reduced features, p. Shaded regions indicate ±1 standard deviation with 1000 realizations of each point. Training and test data is equivalent to Fig. 6. (a) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and (b) Normalized Average Mutual Information between test and predicted SOI data. (c) Runtime of combined model training and testing in seconds. ‘Factor’ is the multiplicative factor applied to each hyperparameter, meaning 1.0 is simply the prescribed value of the given hyperparameter. The orange twin axis shows the value of \(\xi\) independently since \(\xi\) must be a natural number. Here, we take the default values of k and p as described earlier with an associated quantile threshold of 0.5, and the default value of \(\xi\) is 1.

Remark on training data length

Aside from eliminating hyperparameter tuning, we use SOI data (with a lead value of 1) to demonstrate that TreeDOX does not require as much training data as the alternative methods. We keep the test data equivalent to that used in Fig. 6 and vary the length of the training data, where the training region is kept a temporally contiguous stretch terminating right before the test data. Fig. 7 displays the results of this experiment. Note that the RMSE and NAMI of TreeDOX remain mostly stable despite the length of the training data. Furthermore, the RMSE is usually lower, and NAMI is usually higher than the compared methods, indicating the superior accuracy of TreeDOX. The bottom row of Fig. 7 shows that, despite TreeDOX not beating the speed of linear RC and NG-RC training, it scales better than RNN and LSTM as the length of training data increases. We reiterate that these runtime results do not report any hyperparameter tuning required for RC, NG-RC, RNN, and LSTM, and therefore, TreeDOX may be faster to use in practice.

Robustness to hyperparameter prescriptions

We demonstrate the resilience of TreeDOX to the value of our prescribed hyperparameters by testing the sensitivity of TreeDOX predictions of SOI data to changes in the delay overembedding dimension, k, the successive time lag, \(\xi\), and the number of reduced features, p. It is important to note that here we are not providing a proof of the low sensitivity of TreeDOX to these hyperparameters, but rather a heuristic numerical experiment with SOI data to demonstrate, with a real-world scenario, that hyperparameter tuning is not necessary. Fig. 8 shows the RMSE, NAMI, and runtime results when individually varying the above hyperparameters (while keeping the others fixed to their respective prescribed values) and predicting SOI data. Note that a ‘factor’ value of 1.0 indicates the respective hyperparameter is equivalent to its prescribed value, where the default values of k and p are prescribed as expressed earlier in the manuscript, and the default value for \(\xi\) is 1 as described earlier. Let us first consider k and p. Intuitively, increasing the value of any of these hyperparameters will increase model accuracy at the expense of training complexity, which scales linearly with all three hyperparameters, except for p, which will eventually cause the runtime to reach a plateau when \(p=kD\). Fig. 8a, b show that as the respective hyperparameter is increased, model accuracy plateaus while the runtime in Fig. 8c does, in fact, increase roughly linearly. Observe the lack of the aforementioned plateau in the runtime curve as p varies; this is likely due to the maximum value of p in this experiment not reaching its maximum value kD. Note that the prescribed hyperparameter values manage to balance runtime while lying on the accuracy plateau. Next, we investigate \(\xi\), in which one might expect an increase in \(\xi\) to impair model accuracy due to dropping short-term delay states while lowering runtime due to the respective decrease in k according to Eq. 1. Fig. 8 supports this hypothesis while also demonstrating \(\xi\)’s plateau effect on runtime, likely due to \(\xi\) being in the denominator of Eq. 1 and the computation complexity of training scaling linearly with k. Of course, we recommend selecting the smallest such possible value of \(\xi\) that is computationally reasonable due to its inverse effect on accuracy.

Final remarks

With the increasing availability of data and computational power to analyze it, the need for effective and user-friendly time series forecasting methods is on the rise. Existing state-of-the-art methods, such as RC and LSTM, offer a powerful ability to meet the need for time series forecasting, but can be difficult to use in practice due to their sensitivity to and required tuning of hyperparameters. We propose an alternative in the form of a time delay overembedded and Extra Tree Regressor-based algorithm for autonomous feature selection and forecasting, which does not require hyperparameter tuning.

While the development of TreeDOX was focused on ease-of-use rather than on surpassing the accuracy of modern forecasting models, after testing it on a variety of prototypical discrete, continuous, and spatiotemporal systems, we find that TreeDOX provides comparable or better performance to current methods such as RC and LSTM. We also demonstrate the efficacy of TreeDOX to predict realistic data with SOI open-loop forecasts and again discover TreeDOX’s similar performance to LSTM, NG-RC, and other state-of-the-art forecasting models.

Data availability

Data and code are available in our Zenodo repository: https://zenodo.org/records/15866111.

References

Pathak, J., Hunt, B., Girvan, M., Lu, Z. & Ott, E. Model-free prediction of large spatiotemporally chaotic systems from data: A reservoir computing approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 024102 (2018).

Gauthier, D. J., Bollt, E., Griffith, A. & Barbosa, W. A. Next generation reservoir computing. Nat. Commun. 12, 5564 (2021).

Wu, T. et al. Predicting multiple observations in complex systems through low-dimensional embeddings. Nat. Commun. 15, 2242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46598-w (2024).

Jaeger, H. & Haas, H. Harnessing nonlinearity: Predicting chaotic systems and saving energy in wireless communication. Science 304, 78–80 (2004).

Zhai, Z.-M. et al. Model-free tracking control of complex dynamical trajectories with machine learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 5698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41379-3 (2023).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Elsworth, S. & Güttel, S. Time series forecasting using LSTM networks: A symbolic approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.05672 (2020).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Maass, W., Natschläger, T. & Markram, H. Real-time computing without stable states: A new framework for neural computation based on perturbations. Neural Comput. 14, 2531–2560 (2002).

Bollt, E. On explaining the surprising success of reservoir computing forecaster of chaos? The universal machine learning dynamical system with contrast to VAR and DMD. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 31 (2021).

Yperman, J. & Becker, T. Bayesian optimization of hyper-parameters in reservoir computing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.05193 (2016).

Mwamsojo, N., Lehmann, F., Merghem, K., Frignac, Y. & Benkelfat, B.-E. A stochastic optimization technique for hyperparameter tuning in reservoir computing. Neurocomputing 574, 127262 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models based on Bayesian optimization. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 17, 26–40 (2019).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. 2 Ed. (Springer, 2009).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010933404324 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 785–794 (2016).

Shwartz-Ziv, R. & Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Inf. Fusion 81, 84–90 (2022).

Grinsztajn, L., Oyallon, E. & Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data?. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 507–520 (2022).

Hegger, R., Kantz, H., Matassini, L. & Schreiber, T. Coping with nonstationarity by overembedding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4092 (2000).

Verdes, P., Granitto, P. & Ceccatto, H. Overembedding method for modeling nonstationary systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 118701 (2006).

Takens, F. Detecting strange attractors in turbulence. In Dynamical Systems and Turbulence, Warwick 1980: Proceedings of a Symposium Held at the University of Warwick 1979/80. 366–381 (Springer, 2006).

Malik, N. Uncovering transitions in paleoclimate time series and the climate driven demise of an ancient civilization. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 30, 083108. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0012059 (2020).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 63, 3–42 (2006).

Ropelewski, C. F. & Jones, P. D. An extension of the Tahiti-Darwin southern oscillation index. Mon. Weather Rev. 115, 2161–2165 (1987).

Climate Research Unit, U. o. E. A. Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) Data. https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/soi/.

Bergstra, J., Bardenet, R., Bengio, Y. & Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 24 (2011).

Oshiro, T. M., Perez, P. S. & Baranauskas, J. A. How many trees in a random forest? In Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition: 8th International Conference, MLDM 2012, Berlin, Germany, July 13-20, 2012. Proceedings 8. 154–168 (Springer, 2012).

Probst, P., Wright, M. N. & Boulesteix, A.-L. Hyperparameters and tuning strategies for random forest. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 9, e1301 (2019).

Fernández-Delgado, M., Cernadas, E., Barro, S. & Amorim, D. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems?. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 3133–3181 (2014).

Grassberger, P. & Procaccia, I. Characterization of strange attractors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 50, 346 (1983).

Lorenz, E. N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow 1. In Universality in Chaos. 2 Ed. 367–378 (Routledge, 2017).

Geurts, B. J., Holm, D. D. & Luesink, E. Lyapunov exponents of two stochastic Lorenz 63 systems. J. Stat. Phys. 179, 1343–1365 (2020).

Kassam, A.-K. & Trefethen, L. N. Fourth-order time-stepping for stiff PDEs. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 26, 1214–1233 (2005).

Edson, R. A., Bunder, J. E., Mattner, T. W. & Roberts, A. J. Lyapunov exponents of the Kuramoto-Sivashinsky PDE. ANZIAM J. 61, 270–285 (2019).

Kiladis, G. N. & van Loon, H. The southern oscillation. Part VII: Meteorological anomalies over the Indian and pacific sectors associated with the extremes of the oscillation. Mon. Weather Rev. 116, 120–136 (1988).

Trenberth, K. E. The definition of El Nino. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 78, 2771–2778 (1997).

Power, S. B. & Kociuba, G. The impact of global warming on the southern oscillation index. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1745–1754 (2011).

Harisuseno, D. Meteorological drought and its relationship with southern oscillation index (SOI). Civ. Eng. J. 6, 1864–1875 (2020).

Ranasinghe, R., McLoughlin, R., Short, A. & Symonds, G. The southern oscillation index, wave climate, and beach rotation. Mar. Geol. 204, 273–287 (2004).

Chowdhury, R. & Beecham, S. Australian rainfall trends and their relation to the southern oscillation index. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 24, 504–514 (2010).

žvković, T. & Rypdal, K. Enso dynamics: Low-dimensional-chaotic or stochastic? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 2161–2168. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50190 (2013) .

Yan, J., Mu, L., Wang, L., Ranjan, R. & Zomaya, A. Y. Temporal convolutional networks for the advance prediction of ENSO. Sci. Rep. 10, 8055 (2020).

Team, R. D. RAPIDS: Libraries for End to End GPU Data Science (2023).

Raschka, S., Patterson, J. & Nolet, C. Machine learning in python: Main developments and technology trends in data science, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.04803 (2020).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Nakandalam, S. et al. Taming model serving complexity, performance and cost: A compilation to tensor computations approach (2020).

Rochester Institute of Technology. Research Computing Services. https://doi.org/10.34788/0S3G-QD15 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Research Computing at the Rochester Institute of Technology for supplying computational resources during the course of this work47. The research of E.B. is supported by the ONR, ARO, DARPA RSDN, and the NIH and NSF CRCNS. N.M. is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), Award Number: 2434716. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

Funding

A.G. and K.R. declare no funding sources. The research of E.B. is supported by the ONR, ARO, DARPA RSDN, and the NIH and NSF CRCNS. N.M. is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), Award Number: 2434716. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G., K.R., and N.M. designed the research. A.G. carried out the research. A.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.G., K.R., E.B., and N.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. E.B. and N.M. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giammarese, A., Rana, K., Bollt, E.M. et al. Tree-based learning for high-fidelity prediction of chaos. Sci Rep 15, 41967 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25939-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25939-9