Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) commonly affects the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), leading to dentofacial deformities and orofacial symptoms. Timely diagnosis and treatment initiation are essential for optimizing patient outcomes. However, clinical examination—the primary screening method— has limited accuracy, increasing the risk of delayed TMJ involvement detection. This study develops, trains and tests an artificial intelligence (AI) model for predicting TMJ involvement in newly diagnosed JIA patients and compares its model performance with expert clinician assessments for validation. A longitudinal dataset of 6,153 standardized orofacial examinations from 1,054 patients with JIA was used to train an Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model to predict TMJ involvement. An independent cohort of 55 newly diagnosed patients was used to evaluate the model. Twenty-six clinically relevant features were selected and preprocessed for model input. Model performance was evaluated based on classification accuracy and concordance with expert clinician assessments. Model interpretability was analysed using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) to identify key predictive features. The XGBoost model achieved an overall accuracy of 85.5% in predicting TMJ involvement. Model predictions showed significant concordance with expert clinician assessments (p < 0.001), although the model identified a higher prevalence of TMJ involvement than experts. The most influential predictive features were reduced condylar translation, facial asymmetry, protrusion, patient-reported orofacial pain and reduced mouth-opening capacity. The developed AI model demonstrates strong predictive performance for TMJ involvement based on clinical examination. By facilitating earlier detection, the model has the potential to support clinical decision-making, enable timely intervention, and improve patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the predominant chronic rheumatic condition of childhood, with a prevalence of 15/100,000 in Scandinavia1. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involvement is a frequent manifestation of JIA with a reported prevalence of 30–45%2. TMJ involvement may initially be asymptomatic but often progresses to produce orofacial signs and symptoms2,3,4,5. In skeletally immature individuals, TMJ involvement may cause JIA-related dentofacial deformities, which in turn may reduce upper airway dimension6,7,8. Orofacial manifestations of JIA may persist into adulthood and negatively affect general and oral health-related quality of life9,10,11. Effective management of JIA-related orofacial manifestation, often requiring interdisciplinary care, is believed to rely on early diagnosis and timely initiation of appropriate treatment12. Diagnostic challenges arise due to significant overlap between JIA-related TMJ disease, other forms of temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) and normal variations in dentofacial development13,14,15,16.

Routine clinical orofacial examination is recommended as a low-cost primary screening tool to monitor orofacial health in JIA12,17. This examination involves standardized evaluation of orofacial signs and symptoms, dentofacial growth, orofacial health and general and oral health-related quality of life12,17. According to consensus-based recommendations, clinical orofacial examination should encompass clinician-assessed pain location, TMJ tenderness upon palpation, mandibular deviation at maximal mouth opening, measurement of maximal unassisted opening capacity, facial asymmetry, evaluation of the facial profile and assessment of occlusion/malocclusion and sagittal and vertical relationships17. TMJ pain and/or dysfunction should be assessed both at rest and during function (e.g., mouth opening and chewing)15. However, TMJ involvement is likely underdiagnosed due to limited routine assessment of the TMJ during physical examination or imaging and insufficient domain-specific expertise to interpret and act on clinical findings18. We hypothesize that artificial intelligence (AI) can facilitate early diagnosis and accurate prediction of TMJ involvement through systematic analysis of standardized clinical data19.

This study aimed to develop, train and test an AI model for predicting TMJ involvement in patients with newly diagnosed JIA, with applicability in routine clinical practice. To evaluate its clinical usefulness, model predictions were compared with clinicians’ assessments. Additionally, we sought to identify clinical features influencing model decision-making using explainability tools.

Materials and methods

Data collection

For model development, we used prospectively collected data from the Aarhus University JIA-TMJ database. The database contains population-based longitudinal data from patients diagnosed with JIA according to the criteria according to International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) criteria20, who were referred between 2000 and 2023 to the Regional Specialist Craniofacial Centre at the Department of Dentistry and Oral Health, Aarhus University, Denmark, from these three paediatric rheumatology centres in western Denmark (Aarhus, Odense and Aalborg) or by dentists. Referrals were made for clinical orofacial examination and treatment of TMJ involvement and the related orofacial manifestations. Patients are referred irrespective of TMJ involvement or systemic treatment. Specialised orthodontists routinely perform longitudinal, standardized orofacial examinations for all JIA patients in accordance with international standards17. Treatment of JIA-related orofacial conditions is coordinated with paediatric rheumatology and oral surgery departments. Patients without TMJ involvement continue regular follow-up until transition to adult care at age 16–18 years, unless in remission off medication, in which case follow-up may end earlier. In Denmark, this care is universally tax-funded. The Aarhus JIA-TMJ database comprises real-world data without predefined registration intervals and represents the total population of patients with JIA from Western Denmark. Patients with early-onset JIA are typically represented by multiple orofacial examinations before transition to adult care, while those with late-onset disease have fewer. Examination intervals varied from 3 to 18 months, depending on TMJ status and patient needs. All patients from the training as well as the test dataset provided informed consent in written form. For patients under the age of 15, a parent or legal guardian provided informed consent.

Dataset composition

The present study adheres to the interdisciplinary consensus-based terminology related to JIA and TMJ arthritis21. Longitudinal data from the routine orofacial examinations were retrieved from the Aarhus University JIA–TMJ database according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) a JIA diagnosis according to the International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification19, (2) first clinical orofacial examination conducted after 1 January 2000, (3) last clinical examination performed before 2023. Each unique clinical orofacial examination comprises 95 standardized items recorded systematically, covering (i) orofacial symptoms (e.g. pain on mouth opening, pain at movement, compromised chewing function), (ii) TMJ dysfunction (e.g. diminished condylar translation, and mouth-opening capacity, (iii) facial morphology (asymmetry of the face, facial profile) and occlusion, (iiii) medical treatment and (v) diagnostic information concerning the presence of TMJ involvement at the time of examination. Each clinical examination results in an overall assessment of TMJ involvement, based on findings from the clinical examination and radiological and imaging data. Labels were assigned at the time of each clinical examination. The diagnosis and classification of TMJ involvement are documented in the database for each clinical examination.

Training data

For model development (Fig. 1), the tabular training dataset comprised information from 6153 consecutive standardized clinical examinations conducted in 1,054 subjects with JIA. For each individual, aged between 2 and 17 years, clinical examinations were documented from January 2000 until January 2023. The same group of 12 clinicians consistently performed all clinical examinations over the 23-year study period. A previous study demonstrated that there is moderate to substantial agreement between the examinations recorded by the different clinicians22.

Test data

The developed model was tested using data from the initial orofacial examinations of newly referred patients (n = 55) to the Regional Specialist Craniofacial Centre, recorded in the Aarhus JIA–TMJ database between January 2022 and May 2023. These test set patients were not included in the training of the prediction model. All patients in the test dataset underwent the same standardized orofacial examination. An expert assessment of TMJ involvement, based on the initial clinical consultation, was available for all patients. Use of the data from the Aarhus University JIA–TMJ database was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (reference no. 624225) and approved by the Danish Health Authorities. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Model development

The primary study outcome was to develop an AI model to support the diagnosis of TMJ involvement at the initial clinical orofacial examination. TMJ involvement was defined as the presence of active TMJ arthritis and/or abnormalities presumed to be sequelae of previous TMJ arthritis, in accordance with current interdisciplinary consensus-based recommendation on TMJ arthritis terminology23.

Feature selection and preprocessing

To prepare input for development and training, data from the standardized clinical assessments were cleaned to address inconsistencies, missing entries and outliers. Of the 95 items recorded in each standardized examination, the most relevant were selected to minimise the number of input variables and enhance the model’s applicability in other centres with shorter examination protocols. Feature selection was guided by expert judgement, prioritising clinical relevance and routine availability during initial consultations, and aligning with previous consensus-based recommendations17. This process resulted in 26 items selected as input features for model training. Pre-processing included the consolidation of bilateral variables, with the merged value reflecting either the shared value or, where applicable, the greater of the two. Medication combinations were grouped into five categories to reduce dimensionality: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), intraarticular corticosteroids and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which were further categorised into conventional DMARDs, such as methotrexate (MTX) and leflunomide, and biological DMARDs (bDMARD). Categorical features, such as type of facial profile and lower facial height, were transformed using entity embeddings. All continuous numerical features were normalised to a defined range. Mouth-opening capacity and protrusion were further adjusted to reflect their deviation from age- and sex-specific means and scaled by standard deviation. Further technical details are available in our pilot study by Christensen et al.19. The final set of engineered features used in model training is summarised in Table 1.

Model training

The model was structured using Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). XGBoost is a powerful ensemble decision tree algorithm that enhances prediction accuracy by combining multiple trees through gradient boosting, and is particularly well suited for analysing tabular data24,25. Furthermore, it provides a suitable option for applications with class imbalances, as it is the case in our study26. The model was implemented in Python 3.10.12 using the Keras, TensorFlow, scikit-learn, Matplotlib, Seaborn and XGBoost libraries. Training was conducted on a longitudinal training dataset of 1,054 patients, aiming to predict TMJ involvement in patients with JIA based on 26 clinical orofacial examination items. The number of training iterations was set to 50. A cut-off threshold of 50% was applied to generate binary predictions for TMJ involvement. Since the dataset includes multiple examinations per patient and the samples are not all independent, we use patient-disjoint splitting and group-aware cross-validation. Hyperparameters controlling tree complexity (maximum depth, number of boosting rounds), learning dynamics (learning rate), and regularization (minimum child weight, subsampling of observations and features, and L1/L2 penalties) were tuned. Randomized search with stratified group k-fold cross-validation grouped by patient was conducted over the ranges listed in Supplementary Table S1. Model hyperparameters were optimized using the macro-averaged F1 score as the optimization metric.

Model testing

The dataset comprising 55 new patients, not included in model training, was used to evaluate model performance. Model performance was assessed and reported using the following metrics: F1 macro score, accuracy, precision, sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted and a confusion matrix was computed. Model predictions were compared with clinical assessments on the presence of TMJ involvement, based on clinical data and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), the latter considered the diagnostic gold standard. Statistical significance of the correlation between model predictions and expert assessments was analysed using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp, USA).

Model explainability

We implemented Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each of the 26 features to the machine learning model’s predictions. SHAP provide a detailed decomposition of individual predictions attributing contributions to each feature while adhering to properties like consistency and local accuracy27. Aggregated SHAP values across the dataset provide insights into the model’s overall behavior, thereby enhancing transparency and interpretability28.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of test dataset (n = 55) are presented in Table 2. In the training dataset (n = 1,054), the prevalence of TMJ involvement at initial clinical examination was 23.95%. In the test cohort (n = 55), the prevalence was 12.73%. The oligoarticular subtype (training dataset: 50.41%, test dataset: 29.1%) and the polyarticular JIA (training dataset: 24.4%, test dataset: 34.6%) were the most frequently diagnosed JIA subtypes. An unspecified JIA subtype was recorded in 14.16% of cases in the training dataset and 14.5% in the test dataset.

Model testing

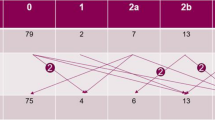

The XGBoost model used to predict TMJ involvement in patients with JIA demonstrated an accuracy of 85.5% in the test dataset (Table 3). The F1 score was 55.6%. The ROC curve and corresponding area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8571 showed strong discriminative performance in identifying TMJ involvement (Fig. 2). Classification performance based on the confusion matrix (Fig. 2) was generally favorable. However, the model produced a false-positive rate of 10.9%, resulting in a lower precision score. In addition, the Brier score was 0.1099, indicating good overall calibration and accuracy of the predicted probabilities. In addition to overall accuracy and AUC, class-specific performance measures were calculated. The model achieved an F1-score of 0.91 for the no TMJ involvement class and 0.56 for the TMJ involvement class, with a macro-F1 of 0.73. Precision for the TMJ involvement class was 0.45 and recall 0.71, reflecting the model’s ability to identify most patients with TMJ involvement, however, at the cost of false positives. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (Supplementary Table S2) indicated some uncertainty due to the small number of positive cases (n = 7).

Among the 55 patients in the test dataset, the model predicted TMJ involvement in 12 cases (21.8%). The predicted probability distribution was bimodal, with most cases clustering at either 0% (indicating no TMJ involvement) or 100% (indicating definite involvement), and few predictions falling near the 50% threshold (Fig. 3).

Distribution of probabilities for TMJ involvement as predicted by the XGBoost model. Note: The distribution of predicted probabilities for TMJ involvement is bimodal, with peaks near 0% (minimal likelihood) and 100% (high likelihood), and very few predictions clustering around the 50% threshold. The 50% threshold represents uncertainty in classification.

Comparison of model predictions with the clinicians’ assessment, used as the gold standard, showed a significant agreement of 85.4% (p < 0.001). The model identified TMJ involvement in some patients not diagnosed by clinicians (Table 4). A detailed comparison of model predictions and the clinician assessments is provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Model explainability

Global SHAP value analysis reveals the relative contribution of individual features to the model’s predictions. The most influential features included reduced mandibular condylar translation during mouth opening; presence of an occlusal plane and lower face asymmetry; quantitative measures of mandibular protrusion capacity and mouth-opening capacity; TMJ pain during movement; and limited mouth opening (Fig. 4).

Global SHAP values explanations based on feature list. DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; bDMARD = biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents; TMJ = temporomandibular joint. Features are listed in order of their impact on model output, with the most impactful features at the top and the least impactful at the bottom. Red indicates high feature values, whereas blue indicates low feature values. On the x-axis, higher feature values correspond to a positive influence on the prediction of TMJ involvement, whereas lower values correspond to a negative influence.

Condylar translation capacity exerted the strongest impact on the model’s output. A value of 0 denoted normal condylar translation during mouth opening, 1 indicated slightly reduced condylar translation and 2 indicated markedly reduced translation. As shown in Fig. 4, diminished condylar translation capacity was associated with increased likelihood of the model predicting TMJ involvement. Conversely, normal TMJ translation capacity was associated with a prediction of no TMJ involvement. Facial asymmetry in our sample was similarly associated with the model predicting TMJ involvement. Furthermore, reduced mouth opening and protrusion, alongside pain during movement and mouth opening, were associated with predictions of TMJ involvement.

Discussion

This is the first study to implement AI in the clinical diagnosis of TMJ involvement in subjects with JIA. The applied XGBoost machine learning model demonstrates the potential of AI solutions to support clinical prediction of TMJ involvement in patients with JIA based on tabular clinical examination datasets. We suggest that this AI model may aid clinicians in interpreting clinical examination data and increase the sensitivity and specificity of TMJ involvement assessments. The model predicted TMJ involvement in 20.0% of patients with JIA in the test dataset, which falls below the typically reported prevalence2. The model uses routinely collected clinical data as input variables, with most of the 26 features aligning with prior consensus-based recommendations for clinical examination17. Hence, the model has the potential to be integrated into clinical practice as a decision support tool, pending further external validation.

The primary factors impacting the model’s prediction included: (1) orofacial symptoms, such as pain during movement and upon opening; (2) orofacial dysfunction, particularly condylar translation; and (3) facial morphology and occlusal characteristics, including facial and occlusal plane asymmetry, along with quantitative measures of protrusion and mouth opening. This aligns with existing literature recommending the documentation of these variables during each clinical examination15. According to our results, decreased condylar translation had the strongest influence on the model’s predictions. This clinical feature is frequently observed in patients with JIA and TMJ involvement, with a reported prevalence ranging from 6 to 43%4,29. Thus, assessment of condylar translation during mouth opening remains an important component of the clinical orofacial examination. The second most influential variable in the present study was occlusal plane asymmetries. In patients with unilateral TMJ involvement, differences in ascending ramus height can cause occlusal plane canting30. However, given the young age of our study population, most patients were in the deciduous dentition state, which may also contribute to occlusal plane variations30. The third most influential variable was facial asymmetry. Recent findings show associations between facial asymmetries and TMJ involvement in patients with JIA31. Facial asymmetry in patients with JIA is most commonly observed in the lower facial third32,33. However, facial asymmetries may reflect natural growth variation in non-JIA background populations or result from TMJ trauma, leading to developmental changes not exclusively attributed to JIA and TMJ involvement34,35,36. Therefore, facial asymmetry should be evaluated in conjunction with other clinical indicators. Clinical features such as diminished mouth-opening capacity, mandibular deviation upon opening and reduced protrusion indicate a restricted mandibular range, a common finding in children with TMJ involvement. Finally, clinical assessment should include orofacial signs such as limited mouth-opening capacity and pain on movement, as these features are relevant indicators of TMJ involvement and are supported by existing literature15,17.

Our model shows high accuracy of over 85% on an independent cohort, which supports the model’s practical value. Its accuracy and sensitivity metrics are in line with the prior pilot study19, which implements a random forest model and evaluated performance within the first 24 months after each patient’s baseline visit. Precision is lower in our setting, which is expected given our stricter, patient-disjoint evaluation on newly referred patients (reducing optimism from correlated exams). Besides, a lower prevalence of TMJ involvement in the external test cohort reduces precision even at similar sensitivity/specificity37, and a small number of positives in the test set is associated with more uncertainty. Overall, the stricter validation makes our estimates more conservative than the pilot.

The probability distribution from the test dataset indicates that the model tends to produce definitive predictions regarding TMJ involvement, with most outputs falling clearly above or below the 50% threshold, reflecting high model confidence in classifying the absence or presence of TMJ involvement. This characteristic is particularly advantageous in clinical settings, where diagnosing TMJ involvement is often complex and nuanced. Additionally, unlike clinicians, the model assigns a probability to each prediction, offering insight into the degree of certainty underlying its prediction.

The robustness of the model was evaluated by comparing its predictions with clinicians’ assessments, which are considered the gold standard. This alignment demonstrates the validity of the model and reinforces its potential reliability as a clinical decision-support tool. However, the model predicted a higher prevalence of TMJ involvement (20.0%) than clinicians did (12.7%), resulting in an increased number of false positives. False-positive diagnoses may contribute to overdiagnosis and result in unnecessary examinations or imaging, patient anxiety, and additional strain on healthcare resources. However, according to Koos et al., clinicians tend to underdiagnose the true prevalence of TMJ involvement due to the inherent challenges of clinical assessment and reliance on advanced imaging16. This discrepancy may suggest that the model addresses some of these diagnostic limitations, although further research is needed to confirm this capability. Future studies should include longitudinal follow-up of patients in whom discrepancies between the model and clinicians’ assessments are observed. Such follow-up may help reveal whether TMJ involvement becomes clinically apparent over time, thereby offering further validation of the model’s predictive accuracy.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. The model’s applicability may be limited in settings where fewer than 26 features are included in the institution’s clinical examination protocol. The model includes moderate and severe TMJ pain and crepitation, whereas mild categories were not included; however, their integration might further improve early detection. Pharmacological variables may reflect disease severity or treatment effects rather than directly predicting TMJ involvement, and in early JIA intra-articular corticosteroids could even mask joint involvement. However, their impact in the model was minimal (lowest SHAP values), suggesting limited influence on overall predictions. The validation dataset contained only the 55 patients who were examined during the validation period. Prevalence of TMJ involvement in the validation dataset was lower than in the training dataset, which can affect performance metrics such as precision and F1-score. While the dataset adequately represents the Danish population, it does not capture other demographic groups with differing characteristics, which may limit the model’s generalizability.

Future research should evaluate the model in diverse populations to enable external validation. Additional studies could focus on localised SHAP analyses, comparing model outputs with clinical examination findings using detailed case-based presentations. Such an approach may enable clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of their collected data and understand the model’s rationale for specific diagnostic outcomes. Future AI models could also incorporate imaging data, biomarkers or additional clinical parameters as input alongside standard clinical variables. Given the differing distribution of JIA subtypes between the test and training datasets, the influence of subtype on model prediction warrants further investigation. Whereas our model is trained to detect TMJ in patients already diagnosed with JIA, further models could focus on differential diagnosis and include further degenerative joint diseases, osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis, and idiopathic condylar resorption.

Conclusions

The developed machine learning model (XGBoost) demonstrates the potential of AI solutions to support the prediction of TMJ involvement in subjects with JIA based on data from clinical examinations. The model identified key predictive features for TMJ involvement, including patient-reported orofacial pain and clinical findings such as reduced condylar translation, facial asymmetries, protrusion and reduced mouth-opening capacity. The agreement between the model’s output and clinicians’ assessment—the current gold standard—highlights its potential as a diagnostic support tool for TMJ involvement in patients with JIA.

Data availability

For further information regarding data availability contact [stratos.vassis@dent.au.dk](mailto: stratos.vassis@dent.au.dk).

References

Berntson, L. et al. Incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the nordic countries. A population based study with special reference to the validity of the ILAR and EULAR criteria. J. Rheumatol. 30, 2275–2282 (2003).

Glerup, M. et al. Incidence of orofacial manifestations of juvenile idiopathic arthritis from diagnosis to adult care transition: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 75, 1658–1667. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42481 (2023).

von Schuckmann, L., Klotsche, J., Suling, A., Kahl-Nieke, B. & Foeldvari, I. Temporomandibular joint involvement in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective chart review. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 49, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2020.1720282 (2020).

Weiss, P. F. et al. High prevalence of temporomandibular joint arthritis at disease onset in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, as detected by magnetic resonance imaging but not by ultrasound. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1189–1196. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23401 (2008).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Cumulative incidence of orofacial manifestations in early juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A regional, three-year cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 72, 907–916. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23899 (2020).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Initial radiological signs of dentofacial deformity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Sci. Rep. 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-92575-4 (2021).

Niu, X. et al. Restricted upper airway dimensions in patients with dentofacial deformity from juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12969-022-00691-W (2022).

Fjeld, M. G. et al. Relationship between disease course in the temporomandibular joints and mandibular growth rotation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis followed from childhood to adulthood. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-8-13 (2010).

Glerup, M. et al. Longterm outcomes of temporomandibular joints in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 17 years of followup of a nordic juvenile idiopathic arthritis cohort. J. Rheumatol. 47, 730–738. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.190231 (2020).

Rahimi, H. et al. Orofacial symptoms and oral health-related quality of life in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a two-year prospective observational study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12969-018-0259-4 (2018).

Halbig, J. M. et al. Oral health-related quality of life, impaired physical health and orofacial pain in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis - a prospective multicenter cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12903-023-03510-0 (2023).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Management of orofacial manifestations of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: interdisciplinary consensus-based recommendations. Arthritis Rheumatol. 75, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42338 (2023).

Fischer, J. et al. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis - a Norwegian cross- sectional multicentre study. BMC Oral Health. 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12903-020-01234-Z (2020).

Ronsivalle, V. et al. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in juvenile idiopathic arthritis evaluated with diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 51, 628–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42338 (2024).

Collin, M., Hagelberg, S., Ernberg, M., Hedenberg-Magnusson, B. & Christidis, N. Temporomandibular joint involvement in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis—Symptoms, clinical signs and radiographic findings. J. Oral Rehabil. 49, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13269 (2022).

Schiffmann, E. et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network and orofacial pain special interest group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 28, 6–27. https://doi.org/10.11607/jop.1151 (2014).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Clinical orofacial examination in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: international consensus-based recommendations for monitoring patients in clinical practice and research studies. J. Rheumatol. 44, 326–333. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160796 (2017).

Costello, A., Twilt, M. & Lerman, M. Provider assessment of the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective analysis from the CARRA database. https://doi.org/10.21203/RS.3.RS-3837818/V1 (2024).

Christensen, L. T. B. et al. An Explainable and Conformal AI Model to Detect Temporomandibular Joint Involvement in Children Suffering from Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. In 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 1–4 (Orlando, FL, USA, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/embc53108.2024.10781771

Petty, R. et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton. PubMed. (2001). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14760812/ (accessed Oct 10, 2024).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Standardizing terminology and assessment for orofacial conditions in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: international, multidisciplinary consensus-based recommendations. J. Rheumatol. 46, 518–522. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.180785 (2019).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Standardizing the clinical orofacial examination in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an interdisciplinary, consensus-based, short screening protocol. J. Rheumatol. 47, 1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.180785 (2020).

Stoustrup, P., Pedersen, T. K., Nørholt, S. E., Resnick, C. M. & Abramowicz, S. Interdisciplinary management of dentofacial deformity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 32, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2019.09.002 (2020).

Moore, A., Bell, M. & XGBoost A novel explainable AI technique, in the prediction of myocardial infarction: A UK biobank cohort study. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 16. https://doi.org/10.1177/11795468221133611 (2022).

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. XGBoost A scalable tree boosting system. KDD '16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Fatima, S., Hussain, A., Amir, S., Bin, Ahmed, S. H. & Aslam, S. M. H. XGBoost and random forest algorithms: an in depth analysis. Pak. J. Sci. Res. 3, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.57041/pjosr.v3i1.946 (2023).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global Understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9 (2020).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S-I. A Unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777 (2017).

Pedersen, T. K., Küseler, A., Gelineck, J. & Herlin, T. A prospective study of magnetic resonance and radiographic imaging in relation to symptoms and clinical findings of the temporomandibular joint in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 35, 1668–1673 (2008).

Stoustrup, P. et al. Assessment of dentofacial growth deviation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: reliability and validity of three-dimensional morphometric measures. PLoS One. 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194177 (2018).

Collin, M. et al. Temporomandibular involvement in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a 2-year prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024. 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56174-3 (2024).

Economou, S. et al. Evaluation of facial asymmetry in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: correlation between hard tissue and soft tissue landmarks. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 153, 662–672e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.022 (2018).

Bernini, J. M. et al. Quantitative analysis of facial asymmetry based on three-dimensional photography: A valuable indicator for asymmetrical temporomandibular joint affection in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients? Pediatr. Rheumatol. 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-0401-y (2020).

Kellenberger, C. J. et al. Temporomandibular joint magnetic resonance imaging findings in adolescents with anterior disk displacement compared to those with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Oral Rehabil. 46, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12720 (2019).

Kirkhus, E. et al. Disk abnormality coexists with any degree of synovial and osseous abnormality in the temporomandibular joints of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr. Radiol. 46, 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-015-3493-7 (2016).

Liukkonen, M., Sillanmäki, L. & Peltomäki, T. Mandibular asymmetry in healthy children. Acta Odontol. Scand. 63, 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016350510019928 (2005).

Monaghan, T. F. et al. Foundational statistical principles in medical research: Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Med. (Lithuania). 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050503 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Christian Marius Lillelund for his contributions in conceptualizing and developing the model without which the publication would not have been possible. Furthermore, we would like to thank the clinical assistants who meticulously supported the data recording.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.V., C.P., R.P., T.P. and P.S. conceptualized the article. S.V., L.T., D.S., C.L., B.N., R.P. and P.S. developed and implemented the model. T.P., S.V., P.B. and P.S. collected and managed the data. S.V. drafted and C.R, M.G., T.P., R.P., P.B. and P.S. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vassis, S., Todnem, L., Straadt, D. et al. Improving early detection of temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis with a clinically interpretable machine learning model. Sci Rep 15, 39120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25988-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25988-0