Abstract

Nowadays, new electrode materials for energy storage devices like mixed ligands and bi-metal MOFs have attracted a lot of attention owing to their high porosity and high capacity for charge storage. In this study, a Co-based metal-organic framework (4,4’-bpy = 4,4′-Bipyridine and H3BTC = 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid) was successfully fabricated by a hydrothermal method. To obtain good electrochemical behavior, Co-MOFs were modified using a porous spherical scaffold of NiS/Ni3S4 nanoparticles. The electrochemical efficiency was analyzed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, cyclic voltammetry, and galvanostatic charge-discharge methods. Detailed electrochemical scrutiny performed by Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 in a 6 M KOH electrolyte reveals a high specific capacity of 136.67 mAh/g at 1 A/g, with a superb cycle life of 91%. Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC asymmetric supercapacitor produces a large amount of energy density (33.32 Wh/kg) and power density (600 W/kg). The produced composite is an appropriate candidate for electrodes in both batteries and hybrid supercapacitors, owing to its favorable electrochemical characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global problem of environmental pollution has emerged in recent decades. An increase in energy demand is one of the factors contributing to this issue, requiring a greater reliance on fossil fuels. Simultaneously, an excessive consumption of energy is exacerbating energy scarcity and environmental challenges. Renewable resources such as solar energy, tidal energy, and geothermal energy are considered to be environmentally sustainable. However, their long-term availability is limited. Consequently, the development of high-efficiency energy storage systems has emerged as a critical solution. Energy storage technologies that possess substantial energy and power densities, as well as elevated capacity, have garnered substantial interest over the previous ten years1,2,3. Supercapacitors are devices known for their high performance delivery and the need for a printed supercapacitor in all-solid-state form on ubiquitous substrates, including on flexible and bendable platforms4. Supercapacitors (SCs), which belong to the various categories of energy storage devices, have attracted significant attention owing to their remarkable power characteristics, rapid charging duration, extended longevity, and environmental sustainability5,6. Supercapacitors can be broadly classified into two main categories: electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and pseudo capacitors (PC)7. Each of these supercapacitor types possesses unique features, and both demonstrate remarkable performance. An EDLC commonly employs the charges that are accumulated on the interfacial surface between the electrode and electrolyte. The last type uses metal oxides and electrical CPs as the electrode components during the faradaic process to store charge. The integration of two charge storage processes in various electrode systems holds promise for the development of optimal electrode materials8,9.

The spinel metal oxides (AB2O4)10, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)11,12, conductive polymers13,14, and nickel sulfides (NiS, Ni3S4,…)15 are widely used to enhance supercapacitors’ performance. In recent years, NiS and Ni3S4 have attracted attention in supercapacitors owing to their facile fabrication, low cost, and attractive electron transport properties. In particular, Ni3S4, with a cubic spinel structure, exhibits excellent metallic behavior and favorable redox reversibility, and good theoretical capacity16. For example, Wei et al.17 found that the synthesis of NiS with a hexagonal structure and Ni3S4 with a cubic structure demonstrates a 16.6 Wh/kg energy density at a large power density (3338.3 W/kg) and a 60.1 Wh/kg energy density at 142.0 Wh/kg, respectively. Zhang et al.17 synthesized the Co9S8-Ni3S4 hollow spheres. The resultant Co9S8-Ni3S4 HS-13 exhibits a notable specific capacity (equivalent to 1723 F/g) at a 1 A/g current density. Furthermore, this synthesized material indicates exceptional cycling stability, with a remarkable 94.7% retention of its original capacity following 3000 cycles.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), especially mixed-ligand MOFs, owing to adjustable channels, large surface areas, and controllable pore sizes, and adjustable channels can facilitate ion transport and enhance charge storage18,19,20. Several studies have explored various ligand combinations, including trimesic acid (BTC) with isophthalic acid (IPA), amino acids, 5-bromo isophthalic acid (H2BrIP), or 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid, demonstrating the versatility of these frameworks21,22,23,24. The combination of BTC and 4,4′-bipyridine ligands enables the construction of pillared-layer MOFs with interconnected and flexible frameworks. BTC provides abundant coordination sites and high porosity for charge storage, while 4,4′-bipyridine acts as a pillar linker that improves structural flexibility and promotes charge transport through non-covalent interactions. Such synergistic features enhance conductivity, ion diffusion, and overall electrochemical performance, making these MOFs promising candidates for supercapacitor applications25. Therefore, this study aims to develop a hybrid electrode material by integrating Co-Bpy-BTC (Co-MOF) with NiS-Ni3S4 to exploit the synergistic advantages of both components. The incorporation of mixed ligands and bimetallic MOF structures provides an ideal framework with enhanced porosity and charge transport pathways, while NiS-Ni3S4 contributes low cost, high redox reversibility, and considerable theoretical capacity.

In this study, we have successfully synthesized a Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 composite by the hydrothermal technique, which serves as a new electrode material. The electrochemical attributes of the synthesized material were assessed using a range of investigative techniques, consisting of cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Results illustrate that the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 composite has superior electrochemical properties, including a large specific capacity (136.67 mAh/g at 1 A/g) and high cyclic stability (91% after 10000 cycles). This research offers new insights for the enhancement of the functionality of MOF materials and creates an electrode material with superior efficiency.

Experimental section

Chemicals

Cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2.6H2O, 99%), 4,4′-Bipyridine (4,4’-bpy, 99%), and 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid (H3BTC, 99%), nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2.6H2O, 99%), thioacetamide (TAA, 99%), N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP, 99%), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, Mw ~ 534000), potassium hydroxide (KOH, 85%), dimethylformamide (DMF, 99%), and absolute ethanol were received from Merck. All chemicals and reagents utilized in these studies were of analytical quality and employed without undergoing any purifying procedures.

Characterization of materials

The determination of the samples’ phase was carried out using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku D/max- 2400, Cu Ka, a = 0.154 nm, 40 kV) within the 2θ range of 10–80. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, AVATAR, Thermo USA) was utilized to analyze the chemical structure of the specimens. The morphologies and microstructures of the specimens were investigated via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEM-2100f, JEOL, Japan) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JEOL JSM-7001 F, Japan). Furthermore, the pore structures and specific surface areas were specified through the utilization of a Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analyzer.

Fabrication of Co-Bpy-BTC (Co-MOF)

MOF was produced by the hydrothermal route, as shown in Fig. 1a25. To form Co-Bpy-BTC (Co-MOF), 0.210 g of H3BTC and 0.156 g of 4,4’-bpy were mixed with 15 mL of DMF. Subsequently, 0.291 g of Cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate was dissolved in 15 mL of deionized water (DW) via a stirring process that lasted for 30 min, and this suspension was subsequently added to the above mixture. The resulting suspension was stirred for 1 h, followed by its transfer into a Teflon-lined autoclave, and then it was exposed to 80 °C for a period lasting 3 days. Following the process of natural cooling, the Co-MOF was washed three times with DW and absolute ethanol. Ultimately, the powder underwent a drying process at a controlled temperature of 60 °C for a period of 48 h.

Synthesis of NiS-Ni3S4

NiS-Ni3S4 was produced by the hydrothermal method, as shown in Fig. 1b26. Firstly, a solution was obtained by dissolving 0.730 g of nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate and 0.601 g of thioacetamide in 40 mL of ethanol. The solution was then stirred for a duration of 30 min to achieve a uniform suspension. Subsequently, the suspension was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave with a capacity of 70 mL. Then it was heated to a temperature of 180 °C and maintained for 24 h. After this step, the resulting material was subjected to a washing process involving three rinses with deionized water and absolute ethanol. Lastly, the NiS-Ni3S4 powder obtained was dried at 60 °C for 24 h.

Synthesis of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 nanocomposite

To create the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 nanocomposite, by using a hydrothermal method, at first, 0.2 g of Co-MOF was dispersed in 30 mL of ethanol. Then, 0.730 g of nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate was dissolved in 40 mL of ethanol and mixed with the Co-MOF solution. 0.601 g of thioacetamide was added to the suspension, stirred for 30 min, and transferred into an autoclave, heated at 180 °C for 1 day. After the reaction was over, the nanocomposite was decanted three times using DW and ethanol. Subsequently, the nanocomposite was dried at a temperature of 60 °C for 48 h.

The growth mechanism of NiS–Ni3S4 on Dual-Ligand Co-MOF

Based on the synthesis route, the growth mechanism of NiS–Ni3S4 on Dual-Ligand Co-MOF (Co-Bpy-BTC) via hydrothermal treatment can be described as follows: Initially, the Co-MOF framework (synthesized using 4,4′-bipyridine and BTC ligands) offers a highly porous and reactive surface capable of anchoring Ni2+ ions through coordination with oxygen-containing groups and nitrogen donors. Upon addition of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O into the ethanol-based medium, Ni2+ ions are adsorbed or coordinated onto the Co-MOF surface: Ni2+/Co-MOF ◊ Ni2+ + Co-MOF. Subsequently, thioacetamide (TAA), as a sulfur source, decomposes under hydrothermal conditions (180 °C) to gradually release S2− ions through the following hydrolysis: H2S + CH3CONH2 ◊ H2O + C2H5NS.

S2− + H2+ ◊ H2S.

These sulfide ions react with the surface-bound Ni²⁺ to form NiS: NiS ◊ S2− + Ni2+. At the same time, under sulfur-rich and high-temperature hydrothermal conditions, partial conversion of NiS or excess Ni2+ can lead to the formation of Ni3S4, a mixed-valent nickel sulfide containing both Ni2+ and Ni3+ species: 2e + Ni3S4 ◊ 4S2− + 3Ni2+. Alternatively, a secondary transformation pathway is possible: Ni3S4 ◊ S + 3NiS. The Co-MOF matrix plays a vital templating role, restricting the growth of the sulfide phases, facilitating nucleation, and promoting the intimate interface between NiS and Ni3S4. This confined growth leads to the formation of a well-dispersed NiS–Ni3S4 heterostructure over the MOF framework, enhancing electrical conductivity and electrochemical reactivity in the final nanocomposite.

Electrochemical assessment

In the context of the three-electrode system, the platinum plate serves as the counter electrode, while the reference electrode is represented by Ag/AgCl. Additionally, the working electrode is comprised of graphite paper loaded with active material. All electrochemical measurements were conducted in 6 M KOH at ambient temperature. For the preparation of working electrodes, 1 mL of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) was used to dissolve the active materials, 0.04 g (80 wt%), carbon black, 0.0075 g (15 wt%), and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), 0.0025 g (5 wt%). Next, using a micropipette, 10 µL of ink solution was dropped and dispersed onto a 1 × 1 cm2 graphite paper, and it was allowed to dry for a few hours at 50 °C. CV, GCD, and EIS were used to conduct the electrochemical testing. Equations (1) and (2) were used to measure the specific capacity (Qsp) and capacitance (Csp) of electrodes27,28,29,30,31:

Here, I (A), Δt (s), m (g), ΔVeff (V), Csp, and Qsp stand for the current, discharge time, amount of active material on the surface of the electrode, the charge-discharge potential range, specific capacitance (F/g), and capacity (mAh/g), respectively. Because the current is expressed in A/g, the sample mass (0.0008 g) did not need to be considered in these calculations.

The energy density (Ed) and power density (Pd) were determined using the following formulas (Eqs. 3 and 4):

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data were carried out at an open-circuit voltage within the frequency range of 10− 2-105 Hz. The quantitative contributions of capacitive and diffusive charge storage mechanisms were evaluated using the power law and Dunn’s model.

Result and discussion

Characterization of samples

Figure 1c displays the FTIR spectra of the pristine materials and the composite. The large peak observed at 3463.91 cm− 1 in the Co-MOF spectrum is associated with the water molecule’s O–H stretching32. The characteristic stretching vibration that appeared in the 1583.04 cm− 1 corresponds to the C = N bond of 4,4′-bipyridine. The peaks at 1731.74 and 814.35 cm− 1 correspond with the existence of the carbonyl group (C = O) stretching and the C–H bending vibrations (aromatic ring) originating from BTC. Peaks around 496.17 cm− 1 can be assigned to the nitrogen/oxygen coordination with the metal ion. The C = C stretching vibrations of the benzene ring can be assigned to 1606.61 cm− 1. One peak, located at 1184.09 cm− 1, corresponds with the stretching vibration band associated with the C–O–C bond. The C–H stretching and asymmetric bending bands of the Co-MOF are responsible for the peaks located at 1381.08 and 1436.55 cm− 1, respectively. For the NiS-Ni3S4, the band presented at 3439.45 cm− 1 is related to the O–H stretching of the water. The peak at 1090.65 cm− 1 is illustrated by N–H, and the peak at 613.46 cm− 1 is shown by Ni–S33. Moreover, the FTIR analysis of the composites shows that Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 was successfully fabricated.

XRD was carried out to specify the structure of the cellular unit and to verify the effective synthesis of distinct samples. Figure 1d displays the diffraction peaks of Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4, and all samples have extremely crystalline characteristics. As seen from Fig. 1d, all the diffraction peaks can be well indexed to cubic Ni3S4 (JPCDS No. 47-1739) and hexagonal NiS (JPCDS No. 65–0395), and no additional peaks of impurities are found34. The overlapping peaks were more intense in the composite’s XRD spectrum. Furthermore, the absence of an additional peak in the composite shows that there are no contaminants in the material. In this study employed peak fitting with pseudo-Voigt profiles, calculation of d-spacings, estimation of crystallite size using the Scherrer equation (uncorrected for instrumental broadening), and Williamson–Hall (W–H) analysis were employed to determine crystallite size and microstrain. Based on the result of Table 1, the XRD pattern of Co-MOF exhibits relatively broad peaks alongside a few sharper reflections, indicating a heterogeneous crystallite size distribution. The Scherrer analysis suggests an average crystallite size of ~ 173 nm, but the median value (~ 27 nm) shows that most domains are in the nanometer range, with some larger crystallites contributing to peak narrowing. The Williamson–Hall (W–H) analysis gives a crystallite size of ~ 94 nm with a microstrain of ~ 0.5%, suggesting that lattice imperfections and microstrain are significant contributors to peak broadening. This implies that the Co-MOF framework contains both nanosized crystallites and some degree of internal strain. The NiS–Ni3S4 sample exhibits consistently broad diffraction peaks, typical of nanoscale crystallites. Both Scherrer (~ 14–16 nm) and W–H (~ 13 nm) analyses agree closely, confirming uniform nanocrystallite sizes. The W–H slope indicates negligible microstrain, implying good crystallinity at the nanoscale without significant lattice distortion. This suggests that the synthesis produced well-formed nanosized Ni sulfide domains with relatively strain-free crystal structures. The Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 composite sample shows strong and sharp diffraction peaks, but with noticeable broadening in some reflections. The Scherrer mean crystallite size is ~ 235 nm, while the median size (~ 14 nm) indicates coexistence of both small nanoparticles and larger crystalline domains. The W–H analysis provides a crystallite size of ~ 47 nm with ~ 0.6% strain, suggesting that the composite contains heterogeneous crystallites with notable lattice distortion. Such structural features may arise from the integration of different phases or from particle–particle interfaces, which generate internal strain fields.

Using the N2 adsorption/desorption assays, the samples’ surface area and pore volume were determined. The BET model is an extension of Langmuir’s theory (Eq. 5), which is a theory for monolayer molecular adsorption and multi-layer adsorption.

which P and P0 are the absolute and saturation pressure, respectively, and Q is the value of gas adsorbed on the sample. C and Vm represent the BET constant and the amount of gas absorbed on the monolayer, respectively. The BET constant is a material-dependent dimensionless constant and usually has a value of 50 to 200. Vm was determined via the slope and y-axis intercept corresponding to each variable by regression analysis. The specific surface area of the material was obtained by using Vm (SBET = 4.355 Vm). All of the materials had type II of N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm with a mesoporous structure, as shown in Fig. 1e-g. The Co-MOF/Nis-Ni3S4 composite illustrated a surface area of 217 m2/g, indicating a higher number of active sites that could potentially improve electrochemical performance. Furthermore, the surface areas of Nis-Ni3S4 and Co-MOF were 59 and 250 m2/g, respectively. The BJH pore size distribution curves (inset in BET plots) further reveal the importance of hierarchical porosity in the composite. The BJH pore size distribution (desorption branch) reveals that the pristine Co-MOF and NiS–Ni3S4 mainly possess micropores with a primary peak at ~ 2–3 nm and only a limited fraction of mesopores. In contrast, the Co-MOF/NiS–Ni3S4 composite exhibits a hierarchical porous structure characterized by broader mesoporous contributions in the range of ~ 10–40 nm together with a minor macroporous tail (> 50 nm). Such a hierarchical pore network is highly beneficial for electrochemical applications: the meso- and macropores act as ion-transport highways that facilitate fast electrolyte penetration and reduce diffusion resistance, while the smaller pores provide abundant active sites for charge storage. This synergistic combination ensures efficient ion accessibility, improved charge transport, and ultimately enhanced electrochemical performance of the composite compared with the pristine components35,36.

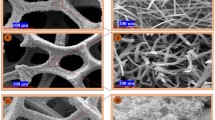

The morphologies and structures of the synthetic materials were examined by FESEM and TEM. The FESEM image of pure Co-MOF with a smooth surface and block-like structure is shown in Fig. 1h. Moreover, Fig. 1i reveals that the NiS-Ni3S4 exhibits spherical morphology, in which its surface is porous. A bow-tie structure for a composite is shown in Fig. 1j. The inert structure of composites is seen in Fig. 1k. According to the TEM image, the Co-MOF blocks are well covered by spherical porous NiS-Ni3S4 nanoparticles. Figure 2 shows the EDS map analysis of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 nanocomposite. As can be seen from the EDS map, the presence of Co, O, C, N, Ni, and S elements confirms Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 synthesis without further contaminants.

Electrochemical assessment

CV, GCD, and EIS tests were carried out to examine the electrochemical assessment of ternary Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 nanocomposites as supercapacitor electrodes. Supercapacitor electrode materials are mostly characterized by a two- or three-electrode configuration. Usually, in a three-electrode system, the electrochemical characteristics of samples are investigated and assessed via a CV test to see if the functioning of the specimens has improved37. Figure 3a indicates the CV plots of the Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrodes, which were attained in a 6 M KOH with a scan rate of 50 mV/s in a voltage window of -0.9 to 0.9 V. The forms of the CV plots of the Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrodes all display redox peaks, denoting that the capacity properties are controlled by both the double-layer and faradaic redox reactions and suggesting excellent hybrid behavior34,38. Furthermore, with the enhancement of the scan rate, the response current grows gradually, and the CV curve maintains its shape, suggesting a rapid faradaic reaction and good conductivity38. The redox peaks observed in the NiS-Ni3S4 electrode are caused by the Ni2+⌠ Ni3+ reaction. Coating NiS-Ni3S4 on the Co-MOF substrate, which has a high active surface and electrical conductivity, along with the synergistic impact of Ni and Co-MOF, results in the formation of an effective Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode. This enhancement is attributed to the creation of efficient channels for ion transfer facilitated by the organic-metallic framework.

As evident from CV results, the appearance of redox peaks in Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 can be described via the corresponding faradaic reactions in the KOH solution as Eq. (6)34:

The CV of each freshly synthesized sample was assessed in the Fig. 3b-d at different scan rates between 10 and 200 mV/s over the potential window of -1.0 and 1.0 V. The Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 composite has the largest specific capacity because specific capacity is inversely correlated with the area under the plot. All generated materials showed almost perfectly defined redox forms in their CV patterns, suggesting that the typical pseudocapacitive manner arises from the probable faradic redox processes. Ion exchange storage is the primary cause of the specific capacity magnitude reduction with increasing scan rate. Additionally, the CV plots had a similar shape, but when the scan rate was enhanced, the peak current rose as well. This observation serves as evidence of the electrode’s exceptional rate performance and the reversible nature of the charge-discharge mechanism39.

A theoretical investigation of the electrochemical nature of the electrode can be conducted using the power law. It explains the relationship between the current and scanning rate, as expressed by Eq. (7):

Equation (7) involves variables denoted as a and b, with b representing the slope values that allow for the examination of the charge storage. The b values are limited to a specific range of 0.5-1, indicating the occurrence of charge storage. The materials of capacitive behavior have a distinct range of b values, which can be either equal to 1 or almost attainable, thus illustrating the method by which they store charge. Values ranging from 0.5 to 1 suggest that the material exhibits pseudocapacitive characteristics, encompassing both diffusive and capacitive processes. Furthermore, the electrodes that have achieved values of b that are close to 0.5 or equal to it, indicate their suitability as electrodes for batteries. The separation of these three categories can be visually depicted in Fig. 3e. Figure 3f-h display the extracted b values obtained from the cyclic profile of all the electrodes. The plot shows the log(peak current (mA)) against the log(scan rate (mV/s)). There are three distinct graphs presented, each depicting the oxidation and reduction peaks along with their respective b values. In all three samples, it is observable that the b values are located closer to the 0.5 range, suggesting that the energy storage process is not a pseudocapacitive process but rather a diffusion-controlled battery behavior.

To further investigate the charge-storage mechanism of the NiS-Ni3S4 on dual-ligand Co-MOF electrodes, Dunn’s method was employed to analyze the contributions of surface capacitance and diffusion capacitance across different scan rates (Eqs. (8–10)):

In this context, I(v) denotes the current measured at a specific applied potential, with k1v and k2v1/2 representing the capacitive and diffusive current components, respectively, while v is the scan rate. The constants k1 and k2 are determined by plotting v1/2 on the x-axis versus I(v)/v1/2 on the y-axis to obtain the average slope and intercept. Subsequently, using these k-values, the capacitive and diffusive characteristics of the material were evaluated, indicating a mixed charge storage behavior40.

Dunn’s model, a non-parametric statistical approach, allows for the comparison of these two capacitances by examining the current responses at varying scan rates, typically reflecting surface charge accumulation and ion diffusion in the electrode material. Figure 3i reveals that the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode stores charge through a combination of surface-controlled and diffusion-controlled mechanisms. At relatively low scan rates (10–20 mV/s), ion diffusion into the bulk material predominates, contributing only about 13–18% of the total capacitance. With increasing scan rates, the contribution from surface-controlled processes becomes more significant, approaching approximately 40% at 200 mV/s, which emphasizes the role of rapid surface redox reactions during fast charging and discharging. Despite this shift, diffusion-controlled processes remain the major contributor, exceeding 60% of the overall charge storage, demonstrating that ion transport within the electrode largely determines the kinetics. This dual-mode behavior highlights the interplay between swift pseudocapacitive surface reactions and slower bulk diffusion, suggesting that careful design of electrode porosity, accessible ionic pathways, and electronic conductivity is crucial for combining high-rate performance with long-term stability40,41.

(a) CV of Co-MOF, NiS/Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. (b) CV curves of Co-MOF, (c) NiS/Ni3S4, and (d) Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 at different scan rates: 10–200 mV/s. (e) Schematic of b values; Determining the b magnitudes for both the anodic and cathodic current peaks for (f) Co-MOF, (g) NiS/Ni3S4, and (h) Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4. (i) Relative contributions of capacitive and diffusive charge storage at different scan rates, estimated using Dunn’s method.

As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the form of the plot gives insight into the possible mechanism or governing phenomenon40. The Nyquist curve in this study was composed of two regions: (1) a Warburg line at the intermediate frequencies among parts B and C, with an inclination of 45°, and (2) one half-circle in the high-frequency zone among parts A and B. The electrode’s resistance to charge transfer is shown by the semicircle diameter (RB–RA), along with a straight line and the solution junction, illustrating the double-layer capacity behavior. Conversely, the electrode resistance that emerges from its porous nature is indicated by the Warburg area41,42. The values of the Warburg resistance (Zw), double-layer capacity (Cdl), charge transfer resistance (Rct), and electrolyte resistance on the surface of the electrode (Rs) are displayed in Table 2. An equivalent circuit model of the electrodes is depicted in Fig. 4a. In charge/discharge procedures, the Rct value of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 (23.6 Ω) was found to be lower than that of NiS-Ni3S4 (414.4 Ω) and Co-MOF (183.8 Ω). This was thought to be advantageous for rapid charge transfer. The short Warburg area indicates appropriate ion diffusion efficiency at high-medium frequency43. In comparison to other electrode materials, Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 exhibits enhanced ion diffusion and charge transfer rates, as demonstrated by ZW and Rct values44. The Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 exhibits the lowest Rct (23.61 Ω) and Zw value (25.79 Ω/s1/2) according to the EIS data. Cdl (instead of an ideal capacitor) is utilized to more precisely specify the electrode’s capacitive impedance behavior in the equivalent circuit model. Here, a semicircle is modeled by parallel arrays of Rct and Cdl in the high-frequency range, representing double-layer capacities and pseudo-capacities45.

Using a three-electrode configuration and a potential range of -0.6 to 0.3 V, the capacitive behaviors of the Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 were investigated using GCD. All GCD curves, as seen in Fig. 4b, have a triangle shape, indicating that the supercapacitor has ideal characteristics46. The Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 sample has a specific capacity value of 136.67 mAh/g at a current density of 1 A/g. This is greater than the NiS-Ni3S4 electrode’s value of 28.38 mAh/g and the Co-MOF electrode’s value of 20.36 mAh/g.

These GCD curves show the clear charge/discharge platform, which is brought on by the redox processes involved in the charge-discharge mechanism. Figure 4c-e show the standard GCD graphs for the Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrodes at different current densities of -0.6 V to 0.4 V. The effectiveness of the samples in a supercapacitor application was evaluated using these charts. Low charge-discharge current values caused potential changes to happen slowly, charge-discharge to last a long time, capacity to be high, active substances to be used at a high rate, and adequate interaction among the electrode substances and the ions of the electrolyte. Conversely, raising the charge/discharge current may result in a quick shift in potential, a reduction in the charge-discharge period, ineffective ion-to-electrolyte interaction, and a significant quantity of ions persisting on the surface of the electrode47. The impact of current density on the specific capacity value is depicted in Fig. 4f. Based on the analysis of the plot, it is evident that an increase in current density leads to a decrease in capacity. This phenomenon can perhaps be attributed to the limited migration of ions into the active materials. Specifically, the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode possesses a specific capacity of up to 213 mAh/g at a current density of 0.5 A/g. Additionally, as capacity retention is a key component in determining how effectively energy storage functions, the long-term cycle stability of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 is required for efficient energy storage applications. The electrochemical stability of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 was investigated by charging and discharging it 10,000 times consecutively at a moderate current density of 1 A/g, as illustrated in Fig. 4g. It was observed that after 10,000 GCD at a high current density of 1 A/g, the mass capacity of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode can keep 91% of its initial level, which is higher than that of the Co-MOF electrode and NiS-Ni3S4 electrode alone38,46.

(a) EIS curve of Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4. (b) GCD of Co-MOF, NiS-Ni3S4, and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 at a current density of 0.5 A/g; (c) GCD curves of Co-MOF, (d) NiS-Ni3S4, and (e) Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 at a current density range of 0.5–8 A/g. (f) Specific capacity trend versus current density. (g) Cyclic stability of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 during 10,000 cycles at 2 A/g.

Furthermore, a comparison has been conducted between the super-capacity behavior of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 and other cutting-edge electrode materials concerning various parameters such as synthesis conditions, electrolyte, capacitance, and cyclic stability. This comparison is illustrated in Table 3. Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 exhibits exceptional performance as a supercapacitor, along with a high degree of cycling stability compared to previously reported materials. According to the outcomes in Table 3, it can be inferred that Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 exhibits potential as a next-generation energy storage material.

The objective of this study is to fabricate an aqueous asymmetric supercapacitor by employing active carbon (AC) as the negative electrode and Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 as the positive electrode. A cellulose paper was positioned between the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode and the AC electrode. Furthermore, the negative and positive electrodes were fabricated via ultrasonic processing. This involved dissolving 5% of the PVDF, 10% of the acetylene black, and 85% of the active material in NMP for 30 min. Subsequently, the resulting mixture was poured onto a pristine carbon paper with dimensions of 1 × 2 cm2. The electrode was thereafter dehydrated at a temperature of 60 °C for 12 h. The mass of the negative electrode was determined using Eq. (11) following the charge balancing hypothesis (q+ = q−).

The symbols C and V represent the capacity and voltage differential between the negative and positive electrodes, respectively. The active mass of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 electrode is 2.2 mg, whereas the active mass of AC (m−) is calculated to be 14.6 mg. base on the device discharge (GCD) data, the energy density (Es, Wh/kg) and power density (Ps, W/kg) of an asymmetric supercapacitor were examined based on Eqs. (12) and (13)55:

The three-electrode setup resulted in a notable improvement in the specific capacity, rate, and cycle performance of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 52. Hence, Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 was selected as a promising material for further investigation. Figure 5a illustrates the assessment of the practical application of Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 in an asymmetric supercapacitor device (ASC) configuration. The ASC configuration consisted of AC, Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4, cellulose paper, and 6 M KOH as the negative electrode, positive electrode, separator, and electrolyte solution, respectively. The CV curves of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC device were conducted at several voltages, spanning from 0.8 to 1.3 V, at a rate of 50 mV/s, to determine the ideal working voltage range of the ASC. Figure 5a demonstrates the detection of the oxygen evolution reaction when the voltage windows were gradually increased to 1.2 V. The data confirms that the value of 1.1 V is appropriate for considering the ASC working voltage. The CV curve series for the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC device, ranging from 10 to 200 mV/s scan rates, is depicted in Fig. 5b. The complete CV curves displayed the characteristics of an EDLC and a PC. The diminished current responsiveness observed at lower potentials can be mostly attributed to an EDLC. Upon considering the possibilities, it was seen that the current density response also exhibited an increase as a result of the rapid Faraday reaction. Consistent with expectations, the shape of the curve remains mostly unchanged even when the scan speeds are raised to 100 mV/s. This can be attributed to the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC device’s rapid electron-ion transfer and its strong I-V responsiveness. Furthermore, it can be shown in Fig. 5c that the GCD curves exhibit triangular forms that are reasonably symmetrical, indicating the presence of a reversible redox mechanism. The specific capacities calculated from the plots are approximately 66.4, 55.6, 46.7, 36.6, and 26.7 mAh/g at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 A/g, respectively, showcasing the remarkable rate capabilities of the ASC device. At a current density of 1 A/g, the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC exhibited high-power densities, specifically 600 W/kg, and an energy density of 33.32 Wh/kg in the two-electrode setup. The energy density of this device exceeds that of most previously described ASCs based on conductive polymers. The electrochemical behavior of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC device was elucidated through the utilization of EIS data. The measurements were examined to determine their characteristics within the specified frequency range of 35 mHz to 100 kHz (Fig. 5d). In the sharp frequency regime, the EIS displays a minor semicircle with a vertical line at the low-frequency region, manifesting the better conductivity of the assembled Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC device. The current Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC demonstrated exceptional cycling stability in addition to its high capacity, exceptional energy, and power capacity. The capacity retention of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC is depicted in Fig. 5e, illustrating its relationship with the cycle number. The results indicate that the ASC exhibits a capacity retention of 92.5% of its initial magnitude after undergoing 1000 GCD cycles. A comparison was made between the Ragone plot of this ASC and previously published plots (Fig. 5f). This ASC device demonstrates a notable energy density of 33.32 Wh/kg, accompanied by a power density of 600 W/kg. This performance surpasses that of previous studies56,57,58,59,60,61.

The CV plots of the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC (a) at various potentials, (b) at different scan rates; (c) The GCD plots of the ASC device at different current densities with a potential window of 0–1.3 V; (d) The EIS fitting model and equivalent circuit for the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC; (e) Cyclic stability after 1000 cycles; (f) Ragone plot comparing our results with other relevant works.

Conclusions

A hydrothermal approach was used to successfully synthesize the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 nanocomposite. NiS-Ni3S4 improves the transport of charges between electrodes and electrolytes in composite materials, leading to an improvement in specific capacity. The favorable performance of the nanocomposite is related to the interconnected porous shape of the generated structure that provides efficient ion transport, a large faradic reaction active site, and large electrical conductivity. The results demonstrate that the crystalline mode of composites containing Co-MOF, which can be preserved for an extended length of time during the charge-discharge mechanism, contributes to the materials’ exceptional stability. For SC applications, the Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4 composite appears to be a viable potential electrode material because of its enhanced specific capacity (136.67 mAh/g at 1 A/g) and cycle stability. The Co-MOF/NiS-Ni3S4//AC ASC device, when assembled, has an excellent energy density of 33.32 Wh/kg at a power density of 600 W/kg, surpassing the performance of other ASC devices based on MOFs that have been previously documented. Additionally, it demonstrates a capacity retention of approximately 91% after undergoing 10,000 cycles. The present study not only presents a viable electrode material for the use of SCs but also showcases a compelling approach for the direct synthesis of additional species of MOFs for energy storage devices.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Salehi, E., Taleghani, H. G., Lashkenari, M. S. & Ghorbani, M. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of polyaniline/S-Rgo nanocomposites with different S-rGO contents for hybrid energy storage devices. J. Electroanal. Chem. 909, 116138 (2022).

Kenesi, A. G., Ghorbani, M. & Lashkenari, M. S. High electrochemical performance of PANI/CdO nanocomposite based on graphene oxide as a hybrid electrode materials for supercapacitor application. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 47, 38849–38861 (2022).

Khan, H. A. et al. A comprehensive review on supercapacitors: their promise to flexibility, high temperature, materials, design, and challenges. Energy, 131043 (2024).

Raihan, K. M. A. et al. Transforming scalable synthesis of graphene aerosol gel material toward highly flexible and wide-temperature tolerant printed micro-supercapacitors. APL Energy 2 (2024).

Jinxi, W. et al. Tailoring of ZnFe2O4-ZrO2-based nanoarchitectures catalyst for supercapacitor electrode material and methanol oxidation reaction. Fuel 334, 126685 (2023).

Foroutan, N., Lashkenari, M. S., Alizadeh, E. & Sedighi, M. Synthesis of manganese ferrite/graphene oxide nanocomposite and investigation of its supercapacitor behaviors. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48, 25859–25868 (2023).

Suman, S. et al. Nitrogen-incorporated boron-doped diamond films for enhanced electrochemical supercapacitor performance. Energy 294, 130914 (2024).

Lashkenari, M. S., Ghasemi, A. K., Khalid, M. & Shahgaldi, S. Facile synthesis of N-doped graphene oxide decorated with copper ferrite as an electrode material for supercapacitor with enhanced capacitance. Electrochim. Acta. 465, 142959 (2023).

Tseng, S. F., Lin, J. Y. & Lin, J. Y. High-performance flexible asymmetric supercapacitors based on Hy-NiCoS/CNTs composites on porous graphene films. Energy 291, 130365 (2024).

Xia, C. et al. Spotlighting the boosted energy storage capacity of CoFe2O4/Graphene nanoribbons: A promising positive electrode material for high-energy-density asymmetric supercapacitor. Energy 270, 126914 (2023).

Ferhi, N. et al. Defective Metal–Organic Framework-808@ polyaniline composite materials for high capacitance retention supercapacitor electrodes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 1235–1243 (2022).

Yazdani, S., Lashkenari, M. S. & Mehri, F. Design a novel mixed-ligand Ni-MOF/MWCNT nanocomposite to enhance the electrochemical performance of supercapacitors. Synthetic Metals, 117702 (2024).

Khanari, H., Lashkenari, M. S. & Esfandian, H. Polythiophene/nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite as a hybrid supercapacitor electrode. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 68, 27–34 (2024).

Ghasemi, A. K., Ghorbani, M., Lashkenari, M. S. & Nasiri, N. Controllable synthesis of zinc ferrite nanostructure with tunable morphology on polyaniline nanocomposite for supercapacitor application. J. Energy Storage. 51, 104579 (2022).

Ramesh, S. et al. Porous metal-organic frameworks derived carbon and nickel sulfides composite electrode for energy storage materials. J. Energy Storage. 73, 109104 (2023).

Das, A. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of Cu2S/NiS/Ni3S4 as high performance supercapacitor application. J. Energy Storage. 92, 112293 (2024).

Wei, W. et al. Novel Ni3S4/NiS/NC composite with multiple heterojunctions synthesized through space-confined effect for high-performance supercapacitors. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 5, 015504 (2022).

Forghani, M., Azizi, A., Livani, M. J. & Kafshgari, L. A. Adsorption of lead (II) and chromium (VI) from aqueous environment onto metal-organic framework MIL-100 (Fe): Synthesis, kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. J. Solid State Chem. 291, 121636 (2020).

Khakpour, F., Ghafouri Taleghani, H. & Soleimani Lashkenari, M. Metal–organic framework/sulfur-doped graphene oxide nanocomposite for high efficiency electrochemical double‐layer capacitors. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 37, e6969 (2023).

Panahi, M., Ghorbani, M. & Lashkenari, M. S. Construction of CO3O4 derived ZIF/GO electrode for outstanding stability in supercapacitors devices. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 47, 9800–9809 (2022).

Talha, K. et al. Construction of a mixed ligand MOF as green catalyst for the photocatalytic degradation of organic dye in aqueous media. RSC Adv. 11, 23838–23845 (2021).

Sun, K. et al. Functionalization of mixed ligand metal-organic frameworks as the transport vehicles for drugs. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 486, 128–135 (2017).

Kafshgari, M. S., Jahanshahi, M. & Ghorbani, M. Magnetic coordination polymer for dye removal and antibacterial activity. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 149, 104995 (2023).

Rachuri, Y., Parmar, B., Bisht, K. K. & Suresh, E. Mixed ligand two dimensional cd (II)/Ni (II) metal organic frameworks containing dicarboxylate and tripodal N-donor ligands: cd (II) MOF is an efficient luminescent sensor for detection of Picric acid in aqueous media. Dalton Trans. 45, 7881–7892 (2016).

Ambrose, B. et al. Impact of ligand in bimetallic Co, Ni-Metal-Organic framework towards oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta. 439, 141714 (2023).

Lv, J. et al. Achieving better impedance matching by a sulfurization method through converting Ni into NiS/Ni 3 S 4 composites. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 1822–1828 (2018).

Afshan, M. et al. Synergistic surface reconstruction and interface engineering in bimetallic selenides: advancing renewable energy storage and oxygen evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 17, 23892–23910 (2025).

Rani, D. et al. Graphene-intercalated P4Se3@ CNF hybrid electrode for sustainable energy storage solution: enabling high energy density and ultra-long Cyclic stability. Carbon 227, 119225 (2024).

Sundriyal, S., Shrivastav, V., Sharma, M., Mishra, S. & Deep, A. Significantly enhanced performance of rGO/TiO2 nanosheet composite electrodes based 1.8 V symmetrical supercapacitor with use of redox additive electrolyte. J. Alloys Compd. 790, 377–387 (2019).

Mai, L. Q. et al. Synergistic interaction between redox-active electrolyte and binder-free functionalized carbon for ultrahigh supercapacitor performance. Nat. Commun. 4, 2923 (2013).

Sundriyal, S., Shrivastav, V., Kaur, H., Mishra, S. & Deep, A. High-performance symmetrical supercapacitor with a combination of a ZIF-67/rGO composite electrode and a redox additive electrolyte. ACS Omega. 3, 17348–17358 (2018).

Radhika, M. et al. Electrochemical studies on Ni, Co & Ni/Co-MOFs for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 054003 (2020).

Nandhini, S. & Muralidharan, G. The binder-free mesoporous CoNi2S4 electrode for high-performance symmetric and asymmetric supercapacitor devices. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 5933–5953 (2022).

Chen, T. et al. Fabrication of interconnected 2D/3D NiS/Ni3S4 composites for high performance supercapacitor. Mater. Lett. 248, 1–4 (2019).

Afshan, M. et al. Electronic modulation of MOF-engineered bimetallic phosphides for cost-effective ampere-level water splitting and continuous hydrogen production via supercapacitor integration. J. Energy Chem. 108, 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2025.04.018 (2025).

Ajravat, K., Pandey, O. P. & Brar, L. K. NiCo2O4@N-doped graphene nanoflowers as electrode material for 2 V high potential window symmetric and asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Power Sources. 649, 237472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2025.237472 (2025).

Zhou, M. et al. Designed formation of lignin-derived Hollow particle-based carbon nanofibers for high-performance supercapacitors. Energy 278, 127705 (2023).

Hu, Q. et al. Controlled synthesis of a high-performance α-NiS/Ni3S4 hybrid by a binary synergy of sulfur sources for supercapacitor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 581, 56–65 (2021).

Sun, M. et al. Room-temperature synthesized porous Cu (OH) 2/Cu 7 S 4 hybrid nanowires as a high-performance electrode material for asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8, 724–734 (2020).

Moats, M. S., Luyima, A. & Oliveria, T. Examination of selected copper electrowinning additives. Proceedings of Hydrometallurgy 2014 (2014).

Mei, B. A., Munteshari, O., Lau, J., Dunn, B. & Pilon, L. Physical interpretations of Nyquist plots for EDLC electrodes and devices. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 194–206 (2018).

Magar, H. S., Hassan, R. Y. & Mulchandani, A. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS): Principles, construction, and biosensing applications. Sensors 21, 6578 (2021).

Moghadam, B. B., Sadeghi, E. & Lashkenari, M. S. Preparation and evaluation of S-rGO/ZnFe2O4/NiCoLDH nanocomposite electrocatalyst in oxygen reduction reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 72, 789–799 (2024).

Chhetri, K. et al. A ZIF-8-derived nanoporous carbon nanocomposite wrapped with Co3O4-polyaniline as an efficient electrode material for an asymmetric supercapacitor. J. Electroanal. Chem. 856, 113670 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. CsPbBr3 nanocrystal induced bilateral interface modification for efficient planar perovskite solar cells. Adv. Sci. 8, 2102648 (2021).

Han, J. J., Yan, Q., Chen, Z., Wang, Z. & Chen, C. Application of Cr-metal organic framework (MOF) modified polyaniline/graphene oxide materials in supercapacitors. Ionics 28, 2349–2362 (2022).

Palsaniya, S., Nemade, H. B. & Dasmahapatra, A. K. Synthesis of polyaniline/graphene/MoS2 nanocomposite for high performance supercapacitor electrode. Polymer 150, 150–158 (2018).

Wang, F. et al. Microwave synthesis of three-dimensional nickel Cobalt sulfide nanosheets grown on nickel foam for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 516, 48–56 (2018).

Li, L. et al. Hollow structured and flower-like C@ MnCo 2 O 4 composite for high electrochemical performance in a supercapacitor. CrystEngComm 16, 9873–9881 (2014).

Mazinani, B., Kazazi, M., Mobarhan, G. & Shokouhimehr, M. The combustion synthesis of Ag-doped MnCo 2 O 4 nanoparticles for supercapacitor applications. Jom 71, 1499–1506 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. In-situ synthesis of heterostructured carbon-coated Co/MnO nanowire arrays for high-performance anodes in asymmetric supercapacitors. Molecules 25, 3218 (2020).

Huo, W. C. et al. Facile synthesis of manganese Cobalt oxide/nickel Cobalt oxide composites for high-performance supercapacitors. Front. Chem. 6, 661 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Rubik’s cube-like Ni3S4/CuS2 nanocomposite for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 847, 156312 (2020).

Huang, F. et al. Ni 3 S 4 supported on carbon cloth for high-performance flexible all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 29, 2525–2536 (2018).

Chi, Y. et al. Ni/Co bimetallic organic framework nanosheet assemblies for high-performance electrochemical energy storage. Nanoscale 12, 10685–10692 (2020).

Kim, M. K. et al. Hierarchically structured transition metal (Cu, Ni) sulfide core–shell electrode for high-performance supercapacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 1014, 178717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2025.178717 (2025).

Patil, V. K. & Raj, C. J. Facile and controlled deposition of battery-type nickel sulfide nanostructure on Ni foam for a hybrid supercapacitor. Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 711, 417298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2025.417298 (2025).

Yu, J. et al. Facile fabrication of ZIF-derived graphene-based 2D Zn/Co oxide hybrid for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage. 27, 101165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.101165 (2020).

Parveen, N. et al. Solid-state symmetrical supercapacitor based on hierarchical flower-like nickel sulfide with shape-controlled morphological evolution. Electrochim. Acta. 268, 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.01.100 (2018).

Çolak, S. G. et al. Boosting supercapacitor performance via flower-like Cu₂XSnS₄ (X = Mn, Co, Ni, Ba, Zn) chalcogenides: solvothermal synthesis and charge storage behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 701, 138672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2025.138672 (2026).

Yin, W. et al. Fe/Co-doped MOF-derived nanoporous carbon in wood-based carbon electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage. 134, 118117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2025.118117 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Babol Noshirvani University of Technology (BNUT) for the financial support.

Funding

Babol Noshirvani University of Technology (BNUT) financially supported this study through Grant No. BNUT/40040115040/1400.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H.A. Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing–Original Draft, Visualization. M.S.L. Conceptualization, Writing–Review & Editing, Validation, Visualization. M.G. Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision. L.A.K. Conceptualization, Writing–Review & Editing, Validation, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alipour, A.H., Lashkenari, M.S., Ghorbani, M. et al. In-situ growth of NiS-Ni3S4 on dual-ligand Co-MOF as a new electrode for high-performance supercapacitors. Sci Rep 15, 39075 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25999-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25999-x