Abstract

The total electron content is an integrated value of ionospheric electron density (Ne) along the satellite-receiver ray path; therefore, it cannot directly resolve ionospheric disturbances in the vertical direction. In this work, to better understand the continuous evolution of co-seismic ionospheric disturbances (CIDs) at different altitudes, we conducted an accurate three-dimensional (3-D) visualization of CIDs associated with the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake based on the computerized ionospheric tomography technique. The results clearly revealed the 3-D morphological discrepancies of CIDs caused by Rayleigh waves, acoustic-gravity waves originating from the epicenter, and internal gravity waves induced by the tsunami waves. Further, we investigated the propagation and distribution of Ne disturbances along altitude. It was found that Ne disturbances triggered by different wave patterns exhibited different evolution characteristics in the vertical direction. The application of 3-D ionospheric detection has the potential to enhance the robustness of the earthquake and tsunami early warning systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sudden vertical crustal displacement during large earthquakes, particularly those with a magnitude greater than 6.5, could excite detectable perturbations in the atmosphere and ionosphere1. Studies on ionospheric response to earthquakes, referred to as co-seismic ionospheric disturbances (CIDs), have been carried out for many decades. CIDs were first detected after the 1964 M9.2 Alaska earthquake by ionosonde and Doppler sounder2. A follow-up study in 1966 reported the evidence of acoustic-gravity waves originating from the epicenter (AGWsepi) propagating in the ionospheric F region3. With the rapid development of the space-based observation technique, global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) are extensively used to explore the ionospheric total electron content (TEC) variations. TEC is defined as the integrated electron density (Ne) value along the satellite-receiver ray path and is measured in TEC units (TECU, 1 TECU = 1016 el/m2). Co-seismic disturbances in TEC were first observed after the 1994 Northridge earthquake by the Global Positioning System (GPS)4. In pioneering studies, the two-dimensional (2-D) CIDs and corresponding coupling process have been substantially investigated with GPS-TEC data5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Studies concerning the tsunami-ionospheric effect closely follow the observations of ionospheric variations related to the offshore earthquakes. In recent decades, abundant studies have been accumulated to suggest that the internal gravity waves (IGWstsu) driven by tsunamis in an open ocean can be undoubtedly observed in the ionosphere, based on the match between the traveling ionospheric disturbances (TIDs) and tsunami waves in aspects such as wavefront orientations, periods, and horizontal phase velocities14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Particular attention has been paid to CIDs related to the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake (hereafter, the Tohoku earthquake), the strongest earthquake ever recorded in Japan since 1900. The main shock (38.32° N, 142.37° E) occurred at 05:46 Universal Time (UT) on March 11, 2011, near the east coast of Honshu, Japan, and caused a devastating tsunami with a maximum wave height of ~ 40 m in Iwate Prefecture. The GPS Earth Observation Network (GEONET) in Japan, one of the densest GNSS networks in the world, provides a unique opportunity to image the CIDs caused by Rayleigh waves (RWs), AGWsepi, and IGWstsu. Using GPS-TEC from GEONET, the horizontal characteristics of CIDs have been investigated in great detail8,10,22,23,24,25,26. By extracting ionospheric perturbations from the 2-D TEC observations, it was found that CIDs initially appeared as a disk-shaped enhancement 8–10 min after the main shock. Subsequently, the fast-propagating zonal perturbations of secondary acoustic waves triggered by RWs became visible. These perturbations quickly traveled away at ~ 2–3 km/s in southwestern Japan. AGWsepi consists of the branch of acoustic waves (AWsepi) and the branch of gravity waves (GWsepi). During 06:00–06:15 UT, large-scale TIDs related to AWsepi moved outward in radial direction at ~ 0.7–1 km/s. After 06:15 UT, concentric meso-scale TIDs (MSTIDs) induced by GWsepi and IGWstsu that traveled with velocities of ~ 0.13–0.5 km/s were recorded9,10.

It is noteworthy that although the Tohoku mainshock occurred during a moderate geomagnetic storm, with Dst − 84 to − 42 nT, Kp 2–6, and F10.7 121.5 sfu, the influence of geomagnetic storm-induced TIDs can be ruled out for two reasons. First, the storm-triggered MSTIDs generally originate at the high-latitude region and tend to dissipate before arriving at the mid-latitude ionosphere owing to viscosity and Joule dissipation processes27,28. Secondly, though the storm-induced large-scale TIDs can propagate long distances to the low-latitude regions, they are typically characterized by long periods of 1–3 h, large horizontal wavelengths of 1000–3000 km, and velocities of 300–1000 m/s29,30, which differ significantly from the features of CIDs.

The previous studies mainly focused on monitoring the 2-D CIDs in the horizontal direction. Performing 3-D diagnosis of CIDs is of great importance to make up for the lack of high-coverage vertical detection and understand the vertical coupling process from the solid earth to the atmosphere and ionosphere. We hypothesize that different CID waveforms will exhibit distinct propagation patterns in the vertical direction and retrieve the 3-D CIDs based on the voxel-based computerized ionospheric tomography (CIT) by taking the Tohoku earthquake as an example. We determine the 3-D structures of Ne disturbance (dNe) related to RWs, AWsepi, GWsepi, and IGWstsu, and discuss the earthquake/tsunami-ionosphere coupling process. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study to investigate the 3-D CIDs triggered by the crustal displacement and subsequent tsunami, including their generation, evolution, and dissipation. In the future, the real-time earthquake and tsunami monitor system could be improved by identifying the seismic signature from the perspective of the 3-D detection of CIDs, along with multiple types of information from classic and new observation methods.

Results

The 3-D structure of CIDs

The dNe structures at four epochs during 05:50–06:04 UT are presented in Fig. 1a–d. At 05:50 UT, faint but noteworthy positive dNe appeared near the epicenter in Fig. 1a. The CIDs are mainly distributed at altitudes between 130 and 190 km, with dNe amplitudes ranging from 0.5 × 1010/m3 to 0.8 × 1010/m3. At 05:54 UT, it expanded outward and arrived in 400 km as shown in Fig. 1b. The upward propagation velocity was estimated to be 0.875 km/s (210 km/240 s ≈ 0.875 km/s), consistent with the acoustic speed of ~ 0.6–1.0 km/s in the F region. At 06:00 UT, remarkable Ne depletion distributed at 200–570 km altitudes appeared in the vicinity of the epicenter. The maximum amplitude of dNe reached up to 2 × 1010/m3. As marked by green and black dotted lines in Fig. 1c, the concentric perturbations driven by AWsepi and zonal perturbations induced by RWs could be clearly distinguished at epicenter distance (Depi) of ~ 500 km. Fig. 1d shows the 3-D structure at 06:04 UT. While the concentric wave patterns propagated radially from the origin source, zonal perturbations traveled quickly southwestwards to the far-field region (Depi > 500 km) and became evanescent.

The horizontal slices of dNe along altitude in the height interval of 130–700 km at (a) 05:50 UT, (b) 05:54 UT, (c) 06:00 UT, and (d) 06:04 UT on March 11, 2011. The black and green dashed lines mark the dNe phase trajectories concerning the AWsepi and RWs, respectively. The red pentagram represents the location of the earthquake epicenter.

Figure 2a–d display the snapshots during 06:08–06:20 UT. As indicated by the black dotted line in each plot, AWsepi propagated to the fringe afield from the epicenter. As time passed, the phase shifts of dNe above the F region peak altitude were faster than those below the peak altitude, most likely due to the acoustic velocity difference in the vertical direction. As depicted in Fig. 2c–d, perturbations related to GWsepi appeared in the near-field region (Depi < 500 km) at 06:16 UT, featured by an inverted conic-like structure. Figure 3a–d present the 3-D structures concerning IGWstsu at 06:36 UT, 08:54 UT, 08:58 UT, and 09:00 UT, respectively. The concentric MSTIDs induced by IGWstsu were visualized at 06:36 UT, covering the height interval of ~ 200–500 km. As marked by the gray lines in each panel, like dNe triggered by GWsepi, the phase alignment of dNe related to IGWstsu also displayed an inverted conic-like structure. The discrepancy between the IGWstsu-induced and GWsepi-induced disturbances can be clearly specified in the travel-time diagram and will be discussed later. The horizontal cross-section of dNe corresponding to all the 3-D dNe structures in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 are displayed in Figs. S1–S3 in the Supplementary. Animation S1 depicts the evolution of 3-D dNe structures from 05:44 UT to 07:34 UT. In summary, there was no evident disturbance in the ionosphere before 05:50 UT. During 05:52–06:14 UT, the initial disk-shaped perturbations, large-scale TIDs caused by AWsepi and zonal disturbances triggered by RWs were discernible successively. Then, the CIDs related to GWsepi appeared in the near-field region from 06:14 UT. Finally, the disturbances caused by IGWstsu appeared around 06:30 UT. IGWstsu propagated over long distances, and thus CIDs were registered across the Pacific Ocean.

The same as Fig. 1, but at (a) 06:08 UT, (b) 06:12 UT, (c) 06:16 UT, and (d) 06:20 UT. The black dashed and red dotted lines mark the dNe phase trajectories related to the AWsepi and GWsepi, respectively.

The same as Fig. 1, but at (a) 06:36 UT, (b) 06:40 UT, (c) 06:44 UT, and (d) 06:48 UT. The gray lines mark the positive phase trajectories with respect to the IGWstsu.

The distribution of dNe along altitude

Figure 4a–c show the vertical variations of dNe to the southwest, west, and north-northwest along L1, L2, and L3, marked in Fig. S4. As marked by the green slopes in Fig. 4a, CIDs induced by RWs propagated southwest with a speed of ~ 2.0 km/s. They arrived at the height interval of 190–340 km at 10–12 min but faded out at 490 km. AWsepi-induced perturbations in 190 km and 340 km were identified 18–20 min after the rupture. In 490 km, they appeared several minutes earlier than those at the lower altitude, which was 14 min after the rupture, possibly due to the absence of RWs-induced disturbances. Note that the propagation velocity of AWsepi presented significant height dependence. As marked by the black dotted lines, velocity at 190 km was ~ 0.65 km/s and increased to ~ 0.90 km/s at 340 km and 490 km. CIDs induced by GWsepi and IGWstsu appeared at 32 min and 42 min, respectively. As discussed earlier, their phase alignments displayed similar inverted conic-like structures in Figs. 2 and 3, but the two types of CIDs can be identified by Fig. 4. To be specific, while GWsepi-induced disturbances traveled with a speed of ~ 0.45 km/s, consistent with the propagation feature of the gravitational branch of AGWsepi31,32, IGWstsu-induced disturbances had a horizontal phase velocity of ~ 0.25 km/s. In addition, GWsepi-induced CIDs mainly appeared in the near-field region ~ 330–500 km from the epicenter and then gradually dissipated. In contrast, the IGWstsu-induced CIDs were first registered at ~ 400 km and propagated to the far-field region.

(a) Hodochrones of dNe at 190 km, 340 km, and 490 km to the southwest along L1. The green, black dotted, red dotted, and black slopes denote the estimated velocities of different CIDs. The white voxel indicates there is no effective satellite-receiver ray path passing through. (b) and (c) Hodochrones of dNe to the west and north-northwest along L2 and L3.

As shown in Fig. 4b, RWs-induced CIDs in the west direction became visible 8–10 min after the earthquake at 190 km and 340 km. These signals also did not appear in 490 km, possibly caused by their fast dispersion in the vertical direction. AWsepi-induced wave patterns were discernible at 16 min. They also exhibited a slower acoustic speed of ~ 0.65 km/s at lower altitude and a faster speed of ~ 0.85 km/s at higher altitude. Then, GWsepi-induced perturbations moving at ~ 0.4 km/s became evident at 26 min. Owing to the poor coverage of satellite-receiver ray paths, the tsunami-driven disturbances were not clearly detected. Fig. 4c presents the distribution in the north-northwest direction. A weak negative phase of RWs emerged at 12 min. Prominent AWsepi with speeds of ~ 0.65 km/s and ~ 0.90 km/s appeared in 190 km and 340 km at 16–18 min. Then, perturbations moving at a horizontal speed of ~ 0.45 km/s related to GWsepi were identified 28 min after the earthquake. The rupture-induced perturbations were somehow weakened at 490 km. Finally, IGWstsu-induced TIDs appeared 42 min after the shock and had a horizontal phase velocity of ~ 0.25 km/s in the F region.

To better understand the vertical propagation characteristics of different CIDs, we evaluated the uncertainties in both propagation velocity and arrival time. A total of 13 vertical slices, SW1–SW5, NW1–NW5 and L1–L3, as shown in Fig. S4, were selected. We used dNe hodochrone diagrams to identify the arrival times of RWs, AWsepi, GWsepi, and IGWstsu at altitudes of 190 km, 340 km, and 490 km. Linear regression was then applied to estimate the corresponding propagation velocities. The relevant parameters are provided in Table S1. The averaged velocities and arrival times, along with 95% confidence intervals, are listed in Table 1. In summary, CIDs arrived successively from lower to higher altitudes. RWs-induced CIDs propagated primarily below the F2 peak. They became absent in 490 km, possibly due to the rapid energy attenuation with increasing height. While the vertical velocities of GWsepi and IGWstsu remained relatively constant in the F region, measured at ~ 0.441–0.473 km/s and ~ 0.238–0.244 km/s, the velocity of AWsepi increased with altitude, which was ~ 0.657 km/s at 190 km, ~ 0.889 km/s at 340 km, and ~ 0.925 km/s at 490 km altitude, respectively.

The time-height evolution of CIDs

To better understand the evolution of CIDs induced by different wave patterns in the vertical direction, dNe was plotted as a function of time versus height in the near-field region of P1 (38° N, 141° E), and the far-field region of P2 (37° N, 137° E) and P3 (44° N, 141° E). As marked by the black lines in Fig. 5, ascending phase structures driven by RWs coupled with AWsepi were visualized in P1, P2, and P3 at 8 min, 12 min, and 14 min, respectively. The amplitude at P1 ranged from − 1.5 × 1010/m3 to 2 × 1010/m3 and decreased to ± 0.5 × 1010/m3 at P2 and P3. Then, they displayed irregular structures and gradually faded out. As marked by the red lines in Fig. 5, GWsepi-induced CIDs with an amplitude of ± 1.0 × 1010/m3 had a descending phase structure in P1 during 28–40 min and exhibited a vertically distributed structure in P2 and P3 at 34 min.

The time-height diagrams of dNe from 2 min before to 74 min after the Tohoku earthquake at P1, P2, and P3, whose locations are denoted by black triangles in Fig. S1. The black lines, red lines, and gray dotted arrows mark the dNe phase variations concerning AWsepi combined with RWs, GWsepi, and IGWstsu, respectively. The white-colored voxel indicates no effective satellite-receiver ray path passing through.

The IGWstsu-induced CIDs featured by curving descending phase structures appeared in the far-field region, P2 and P3. The amplitude reached up to ± 2.0 × 1010/m3 in the F region. Such phase progression strongly indicated that the tsunami waves propagated upward into the ionosphere, because the upward energy propagation of IGWstsu implies the downward phase velocity33. Here, we used the distances from the tsunami center (Dtsu) to specify the propagation characteristics of IGWstsu. Such a wave pattern appeared in P2 (Dtsu ≈ 620 km) at 06:34 UT (48 min after the shock) and arrived in P3 (Dtsu ≈ 750 km) at 06:46 UT (60 min after the shock). The average horizontal velocity was ~ 0.25 km/s, consistent with the value estimated from Fig. 4. It is noteworthy that the descending phase structures did not appear at P1 (Dtsu ≈ 275 km) in the vicinity of the source origin, owing to the oblique propagation of IGWstsu with a slow upward propagating velocity.

Discussion

The earthquake/tsunami-ionosphere coupling process

In general, acoustic-gravity waves provoke disturbances directly by the momentum transfer through ion-neutral collisions along the geomagnetic field lines in the F region; hence, the geomagnetic field has a major impact on the amplitude and waveform of CIDs. While the propagation trajectories of CIDs were traceable after AGWsepi arrived, as shown in Fig. 4a, b, those north-northwest of the epicenter in Fig. 4c became blurred in 490 km. This remarkable damping phenomenon was most likely affected by the geomagnetic field configuration, that is, in the Northern Hemisphere, the acoustic waves-related CIDs are weakened in the poleward and quasi-poleward directions, as the magnetic field inclination is less favorable to their propagation. In addition, it is interesting to note that the quasi-poleward CIDs in 190–340 km still exhibited continuous trajectories. This indicates that the ionospheric plasma background value also contributes to the perturbation amplitude. While the 2-D TEC investigations only demonstrated the existence of CIDs to the north-northwest of the epicenter, our result could visualize the influence of the magnetic field in the vertical direction.

Unlike CIDs provoked by the acoustic-gravity waves mentioned above, disturbances induced by IGWstsu, which were independent of orientation, indicated another coupling process. We speculate that neutral wind disturbance modulated by the obliquely propagating IGWstsu plays an important role, similarly to the typhoon-induced internal gravity waves reported in our previous study34. According to the 3-D detection result, IGWstsu-driven CIDs were featured by horizontal wavelength (\({\lambda }_{x}\)) of ~ 220 km and vertical wavelength (\({\lambda }_{z}\)) of ~ 300 km. On this basis, the vertical group velocity (Vg,z) of IGWstsu was further estimated by using the dispersion relation33:

where N is the Brunt-Väisälä frequency (N = 2π/600 s), k and m refer to the horizontal wave number (k = 2π/\({\lambda }_{x}\)) and the vertical wave number (m = 2π/\({\lambda }_{z}\)), respectively. Consequently, Vg,z is estimated to be 141 m/s, which is much faster than the velocity of the original gravity component of ~ 50–80 m/s7,20. Fast propagating velocity along with a large \({\lambda }_{z}\)~300 km indicates that the observed tsunami-induced CIDs would be caused by the secondary gravity waves35,36.

Within the past decade, several numerical simulations have been conducted to understand the vertical structures of CIDs and the lithosphere-atmosphere–ionosphere coupling. For instance, Meng et al.37 developed the Wave Perturbation-Global Ionosphere-Thermosphere Model for earthquake-ionosphere coupling research and performed a simulation for the same event. The vertical evolution of AWsepi in this study agrees with their simulation results. However, their simulation could not provide the vertical evolution of RWs and IGWstsu, because the model input strongly relies on the ground vertical velocity induced by a point source. In addition, Zhai et al.38 used the simultaneous algebraic reconstruction technique (SART) to study the 3-D propagation details of CIDs following the Tohoku earthquake. Although they successfully estimated the propagation velocities, they failed to give the vertical phase progression of CIDs and vertical wavelength of IGWstsu, which could be attributed to the strong initial-input dependence of their SART method.

Potential applications in earthquake and tsunami detections

Recent studies have proposed that the ionosphere-based detection can be effectively applied to earthquake and tsunami early warning systems39,40. In Japan, a major tsunami warning is issued when the tsunami wave height exceeds 3 m. Accordingly, we investigated the arrival times of 3 m-height waves recorded by five coastal tide gauges reported by the Japan Meteorological Agency. As illustrated in Table 2, the 3-D IGWstsu could be detected from the lower altitude of 190 km, 8–29 min prior to the major tsunami waves arriving at Nemuro, Erimo, and Kuji with Dtsu > 300 km. In contrast, at Ishinomaki and Miyako with Dtsu < 300 km, the ionospheric detection exhibited a time lag of 7–9 min. These results suggested that the current 3-D ionospheric detection holds promise for advancing the early tsunami warning in the near-field region, but timely detection remains challenging for exposed coasts within Dtsu < 300 km from the source. To solve this limitation, accessing reliable 3-D IGWstsu information within 100–130 km altitude in the E region is essential. Therefore, future developments of the ICLSF algorithm will focus on incorporating observational data in the E region from ionosondes and Ne profiles derived from radio occultations.

In addition, seismic source information can be inferred from AWsepi-induced CIDs24,26,40,41. For example, using 1 Hz GPS-TEC data, Astafyeva et al.24 obtained the first ionospheric images for the seismic fault slip of the Tohoku earthquake. Heki et al.41 adopted high-rate TEC data to retrieve the rupture process of the M9.1 Sumatra earthquake. However, the current 3-D detection may not yet be suitable for accurately constraining rupture processes owing to its low temporal resolution (2 min). As a next step, we intend to extract rupture processes by analyzing the anisotropy of 3-D dNe distribution, in combination with seismic-ionospheric coupling models, such as the AWsepi ray tracing model42 and 3-D Non-Tectonic Forcing Mechanisms model43. This could serve as an additional constraint for the rupture process inversion, potentially enhancing the accuracy of rupture velocity models in oceanic regions, where conventional seismometers are sparse or unavailable. Overall, the current 3-D ionospheric detection approach can reproduce the 3-D ionospheric response to different CIDs and phase progression of dNe with altitude in a timely manner, even on a personal computer. It could shed new light on improving the robustness of the future integrated earthquake and tsunami early warning systems.

Conclusion

This study analyzes the 3-D morphological characteristics of CIDs driven by different wave modes related to the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. According to the 3-D results, CIDs first appeared at ~ 130 km altitude 4 min after the rupture in the near-field region. Then, AWsepi-induced and RWs-induced CIDs were discernible and propagated to the far-field region. After that, MSTIDs featured by inverted conic-like structures related to GWsepi and IGWstsu appeared successively.

In the vertical direction, different wave patterns exhibited peculiar propagating characteristics. Specifically, RWs-induced CIDs with a velocity of ~ 2 km/s primarily propagated below the F2 peak altitude in 190–340 km. The velocities of AWsepi presented notable height dependence, with velocities increasing from ~ 0.65 km/s in 190 km to ~ 0.90 km/s in 340 and 490 km. In the north-northwest direction, the AWsepi-induced disturbances were somehow weakened and untraceable over 490 km, which could be explained by the geomagnetic field effect and the sharp decline of plasma density above the F2 layer. CIDs driven by GWsepi propagating at ~ 0.45 km/s and those driven by IGWstsu with a speed of ~ 0.25 km/s substantially remained unchanged, independent of the horizontal direction and vertical altitude. Regarding time-height structure, dNe associated with AWsepi coupled with RWs showed an ascending phase structure. GWsepi-induced perturbations exhibited descending or vertical structure depending on Depi. IGWstsu-related perturbations presented a curving descending phase in the F region in the far-field region, which could be explained by the opposite vertical directions of group velocity and phase velocity of IGWstsu.

Methodology

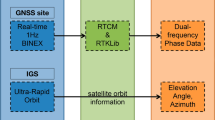

TEC data

Slant TEC (STEC), measured by 800 ground-based GPS receivers from GEONET, was adopted in this study (see cyan dots in Fig. S5). We calculate the absolute value by the code measurement based on the GPS dual-frequency signals, f1 = 1577.42 MHz and f2 = 1227.60 MHz.

where P1 and P2 are the pseudoranges; Bs and Br are the instrumental biases of satellites and receivers, which are determined by a weighted least-squares fitting method44. We convert STEC to vertical TEC (VTEC) by multiplying a single-layer mapping function to normalize the TEC amplitude. The Global Assimilative Ionosphere Model profiles operated by Jet Propulsion Laboratory revealed that the F2 peak height over Japan was at 300 km altitude45. We used this as the altitude of the ionospheric thin shell to extract different types of CIDs caused by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami at the sub-ionospheric points. Moreover, observation data with an elevation angle smaller than 25° are removed to avoid the multipath effect.

Disturbed TEC data

To extract the disturbed VTEC (dVTEC), we use a fifth-order Butterworth band-pass filter to eliminate the ionospheric background variations. The window specification of 0.5–5 mHz is determined by the Hilbert-Huang transform spectra of GPS-TEC datasets46. Then, we convert dVTEC back to disturbed STEC (dSTEC) based on the line-of-sight geometry and use dSTEC as the initial input of the 3-D reconstruction.

The 3-D reconstruction of CIDs

An advanced 3-D reconstruction algorithm, termed the improved constraint least-square fitting (ICLSF) algorithm, was developed using the voxel-based CIT technique. The value of dSTEC on the i-th receiver and j-th satellite ray path is defined as the integration of dNe:

where li and lj represent the receiver and satellite positions, respectively. We assume that the CIDs appeared at a height of 100–1000 km and dNe in each annuli-pixel is constant at a specific time. On this basis, the algebraic series form is given as:

where \({a}_{n}\) and xn are the penetration lengths of the ray path and dNe in the n-th (n = 1, 2, …, N) discrete voxel at 100–1000 km. The generic matrix equation is expressed as:

where \({\varvec{dSTEC}}\) denotes the dSTEC vector; \({\varvec{x}}\) means the dNe vector to be estimated; \({\varvec{A}}\) is the observation matrix. In the ICLSF algorithm, the cost function, \({\varvec{J}}\left( {\varvec{x}} \right)\) and constraint condition, \({\varvec{Wx}}\) are defined as:

where \(\lambda\) is a hyper parameter to balance the least-square term and constraint term, determined by L-curve method. W is a roughness matrix representing the constraint between the target voxel \({x}_{n}\) and its two neighboring voxels \({x}_{n,k}\) in the vertical direction (k = 1, 2). Regarding the restrain parameter, \({C}_{n, k}\), it was equal to 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, and 100 in the altitude intervals of 100–160 km, 190–250 km, 280–460 km, 490–700 km, 730–910 km, and 940–1000 km, respectively. On this basis, \({\varvec{x}}\) can be analytically solved as:

By virtue of its independence of any initial guess that is typically derived from an ionosphere background model, the ICLSF algorithm performs well in accurately capturing multi‐scale ionospheric irregular structures under both quiet and disturbed ionospheric conditions. In our previous work, we successfully applied this algorithm to retrieve the 3-D structures of Ne and dNe associated with the nighttime MSTIDs in the mid-latitude region and the typhoon-induced concentric TIDs over Japan34,47. In addition, the robustness of this algorithm was validated through a resolution test and checkerboard test (see the supplementary material in Song et al.34 for details). Therefore, we extend the algorithm to the Tohoku event in this contribution. The 3-D reconstructed region covers 25°–50° N in latitude, 125°–150° E in longitude, and 100–1000 km altitudes. The spatial resolution is 0.5° × 0.5° × 30 km, and the temporal resolution is 2 min.

Data availability

The GNSS RINEX data is available from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (https://www.gsi.go.jp/ENGLISH/geonet_english.html). We obtained the Kp and Dst indices from the World Data Center (http://wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp) and the F10.7 index from NOAA (https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov). The recorded tsunami height and arrival time are provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency (https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html).

References

Perevalova, N. P., Sankov, V. A., Astafyeva, E. I. & Zhupityaeva, A. S. Threshold magnitude for ionospheric TEC response to earthquakes. J. Atmos. Solar Terr. Phys. 108, 77–90 (2014).

Davies, K. & Baker, D. M. Ionospheric effects observed around the time of the Alaskan earthquake of March 28, 1964. J. Geophys. Res. 70(9), 2251–2253 (1965).

Row, R. V. Evidence of long-period acoustic-gravity waves launched into the F region by the Alaskan earthquake of March 28, 1964. J. Geophys. Res. 71(1), 343–345 (1966).

Calais, E. & Minster, J. B. GPS detection of ionospheric perturbations following the January 17, 1994, Northridge earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22(9), 1045–1048 (1995).

Afraimovich, E. L., Perevalova, N. P., Plotnikov, A. V. & Uralov, A. M. The shock-acoustic waves generated by earthquakes. Ann. Geophys. 19(4), 395–409 (2001).

Heki, K. & Ping, J. Directivity and apparent velocity of the coseismic ionospheric disturbances observed with a dense GPS array. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236(3–4), 845–855 (2005).

Astafyeva, E., Heki, K., Kiryushkin, V., Afraimovich, E., & Shalimov, S. Two-mode long-distance propagation of coseismic ionosphere disturbances. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 114(A10) (2009).

Liu, J. Y., Tsai, H. F., Lin, C. H., Kamogawa, M., Chen, Y. I., Lin, C. H., & Yeh, Y. H. Coseismic ionospheric disturbances triggered by the Chi‐Chi earthquake. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 115(A8) (2010).

Liu, J. Y., Chen, C. H., Lin, C. H., Tsai, H. F., Chen, C. H., & Kamogawa, M. Ionospheric disturbances triggered by the 11 March 2011 M9. 0 Tohoku earthquake. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 116(A6) (2011).

Tsugawa, T. et al. Ionospheric disturbances detected by GPS total electron content observation after the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake. Earth, Planets Space 63, 875–879 (2011).

Astafyeva, E., Shalimov, S., Olshanskaya, E. & Lognonné, P. Ionospheric response to earthquakes of different magnitudes: Larger quakes perturb the ionosphere stronger and longer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40(9), 1675–1681 (2013).

Jin, S., Jin, R. & Li, D. GPS detection of ionospheric Rayleigh wave and its source following the 2012 Haida Gwaii earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 122(1), 1360–1372 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Co-seismic ionospheric disturbance with Alaska strike-slip Mw7.9 earthquake on 23 January 2018 monitored by GPS. Atmosphere 12(1), 83 (2021).

Hines, C. O. Gravity waves in the atmosphere. Nature 239, 73–78 (1972).

Peltier, W. R. & Hines, C. O. On the possible detection of tsunamis by a monitoring of the ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 81, 1995 (1976).

Artru, J., Ducic, V., Kanamori, H., Lognonné, P. & Murakami, M. Ionospheric detection of gravity waves induced by tsunamis. Geophys. J. Int. 160(3), 840–848 (2005).

Liu, J. Y., Tsai, Y. B., Chen, S. W., Lee, C. P., Chen, Y. C., Yen, H. Y., & Liu, C. Giant ionospheric disturbances excited by the M9.3 Sumatra earthquake of 26 December 2004. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33(2) (2006).

Hickey, M. P., Schubert, G., & Walterscheid, R. L. Propagation of tsunami-driven gravity waves into the thermosphere and ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 114(A8) (2009).

Rolland, L. M., Occhipinti, G., Lognonné, P., & Loevenbruck, A. Ionospheric gravity waves detected offshore Hawaii after tsunamis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37(17) (2010).

Occhipinti, G., Rolland, L., Lognonné, P. & Watada, S. From Sumatra 2004 to Tohoku-Oki 2011: The systematic GPS detection of the ionospheric signature induced by tsunamigenic earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 118(6), 3626–3636 (2013).

Savastano, G. et al. Real-time detection of tsunami ionospheric disturbances with a stand-alone GNSS receiver: A preliminary feasibility demonstration. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 46607 (2017).

Manta, F., Occhipinti, G., Feng, L. & Hill, E. M. Rapid identification of tsunamigenic earthquakes using GNSS ionospheric sounding. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 11054 (2020).

Chou, M. Y., Yue, J., Lin, C. C., Rajesh, P. K. & Pedatella, N. M. Conjugate effect of the 2011 Tohoku reflected tsunami-driven gravity waves in the ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49(3), e2021GL097170 (2022).

Astafyeva, E., Lognonné, P., & Rolland, L. First ionospheric images of the seismic fault slip on the example of the Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38(22) (2011).

Liu, J. Y. et al. The vertical propagation of disturbances triggered by seismic waves of the 11 March 2011 M9.0 Tohoku earthquake over Taiwan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43(4), 1759–1765 (2016).

Bagiya, M. S. et al. The Ionospheric view of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake seismic source: The first 60 seconds of the rupture. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 5232 (2020).

Zakharenkova, I., Astafyeva, E. & Cherniak, I. GPS and GLONASS observations of large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances during the 2015 St. Patrick’s Day storm. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 121(12), 12–138 (2016).

Zakharenkova, I., Cherniak, I. & Krankowski, A. Features of storm-induced ionospheric irregularities from ground-based and spaceborne GPS observations during the 2015 St. Patrick’s Day Storm. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 124(10), 17028–17048 (2019).

Shiokawa, K. et al. A large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbance during the magnetic storm of 15 September 1999. J. Geophys. Res. 107(A6), SIA-5 (2002).

Tsugawa, T., Shiokawa, K., Otsuka, Y., Ogawa, T., Saito, A., & Nishioka, M. Geomagnetic conjugate observations of large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances using GPS networks in Japan and Australia. J. Geophys. Res. 111(A2) (2006).

Liu, H. et al. Ionospheric response following the Mw 7.8 Gorkha earthquake on 25 April 2015. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 122(6), 6495–6507 (2017).

Ruan, Q. et al. Study on co-seismic ionospheric disturbance of Alaska earthquake on July 29, 2021 based on GPS TEC. Sci. Rep. 13, 10679 (2023).

Hines, C. O. Internal atmospheric gravity waves at ionospheric heights. Can. J. Phys. 38(11), 1441–1481 (1960).

Song, R., Hattori, K., Zhang, X., Liu, J. Y. & Yoshino, C. The two-dimensional and three-dimensional structures concerning the traveling ionospheric disturbances over japan caused by Typhoon Faxai. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 127(11), e2022JA030606 (2022).

Lund, T. S., & Fritts, D. C. Numerical simulation of gravity wave breaking in the lower thermosphere. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 117(D21) (2012).

Dong, W., Fritts, D. C., Lund, T. S., Wieland, S. A. & Zhang, S. Self-acceleration and instability of gravity wave packets: 2. Two-dimensional packet propagation, instability dynamics, and transient flow responses. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 125(3), e2019JD030691 (2020).

Meng, X., Verkhoglyadova, O. P., Komjathy, A., Savastano, G. & Mannucci, A. J. Physics-based modeling of earthquake-induced ionospheric disturbances. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 123(9), 8021–8038 (2018).

Zhai, C., Yao, Y. & Kong, J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of seismo-traveling ionospheric disturbances after March 11, 2011, Japan Tohoku earthquake. J. Geodesy 95(7), 77 (2021).

Rakoto, V., Lognonné, P., Rolland, L. & Coïsson, P. Tsunami wave height estimation from GPS-derived ionospheric data. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 123(5), 4329–4348 (2018).

Astafyeva, E. Ionospheric detection of natural hazards. Rev. Geophys. 57(4), 1265–1288 (2019).

Heki, K., Otsuka, Y., Choosakul, N., Hemmakorn, N., Komolmis, T., & Maruyama, T. Detection of ruptures of Andaman fault segments in the 2004 great Sumatra earthquake with coseismic ionospheric disturbances. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 111(B9) (2006).

Heki, K. & Fujimoto, T. Atmospheric modes excited by the 2021 August eruption of the Fukutoku-Okanoba volcano, Izu-Bonin Arc, observed as harmonic TEC oscillations by QZSS. Earth Planets Space 74(1), 27 (2022).

Bagiya, M. S. et al. Mapping the impact of non-tectonic forcing mechanisms on GNSS measured coseismic ionospheric perturbations. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 18640 (2019).

Otsuka, Y. et al. A new technique for mapping of total electron content using GPS network in Japan. Earth Planets Space 54(1), 63–70 (2002).

Galvan, D. A. et al. Ionospheric signatures of Tohoku-Oki tsunami of March 11, 2011: Model comparisons near the epicenter. Radio Sci. 47(04), 1–10 (2012).

Chou, M. Y., Cherniak, I., Lin, C. C. & Pedatella, N. M. The persistent ionospheric responses over Japan after the impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Space Weather 18(4), e2019SW002302 (2020).

Song, R., Hattori, K., Zhang, X., Liu, J. Y. & Yoshino, C. Detecting the ionospheric disturbances in Japan using the three-dimensional computerized tomography. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 126(6), e2020JA028561 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by the Grand-in-Aids for Scientific Research of Japan Society for Promotion of Science (26249060), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, Research Program for Prediction of Earthquakes and Volcanic Eruptions (CBA_01) and the joint research program of the Center for Environmental Remote Sensing of Chiba University (CI19-105, CI19-50, CJ22-50). We thank Prof. Kosuke Heki, Hokkaido University, Japan, for participating in the scientific discussion. We also thank the editor and reviewers for taking the time to review our manuscript and providing constructive feedback to improve it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. carried out data analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the text. K.H. conceived the scientific problem and co-drafted the text. X.M.Z and J.Y.L contributed to the interpretation of the vertical coupling. C.Y. helped to analyze the GNSS observation data. All authors have actively participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, R., Hattori, K., Zhang, X. et al. A case study of the three-dimensional co-seismic ionospheric disturbance evolution. Sci Rep 15, 42209 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26074-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26074-1