Abstract

The analysis of time series data from a complex system is challenging, because apart from its multiple stable states arising as low-dimensional manifolds, contribution from the rest of the many variables manifest themselves as state-dependent noise. To identify and characterize these stable states, and detect transitions between them, we need to construct slowly varying order parameters from the noisy time series. In this paper, we propose a model-free method to extract the slowly varying parts of noisy time series data, by taking the difference between the integrated information in a sliding pair of adjoining time windows. Because this differential information has the structure of a derivative, we call it a quasi-derivative and the method quasi-differentiation. We tested this method on some simple examples, before applying it successfully to identify the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers and Mar 2020 COVID-19 market crashes in the daily returns of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) index from 2003 to 2023. We then describe how we can approximate the slowly varying part of the noisy time series, by re-integrating the quasi-derivative obtained. After testing this method of integrated quasi-differentiation on a few other examples, we applied it successfully to extract the slowly varying mean and variance of the DJIA. Finally, we discuss how the method of integrated quasi-differentiation can be used to obtain point estimates of the Hurst exponent and linear cross correlation. Although we have illustrated the above methods on stock market data, we believe they can be applied to a large variety of quantities in many other complex systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An important goal in the analysis of the noisy time series or time series cross section data from a complex system is to discover sudden changes in its state1,2,3,4,5. Ideally, to detect a critical transition or regime shift at rescaled time \(t=0\) in the complex system as we vary a control parameter with time, we need to identify an order parameter with values \(\Phi = 0\) in stable state 1 and \(\Phi = 1\) in stable stable 2 (or vice versa). However, this is unlikely without guidance from rigorous theory. Instead, the state variable x we plot will be a function of the order parameter \(\Phi\) (which remains constant in stable state 1, changes discontinuously at the critical transition, and thereafter remains constant in stable state 2) and other irrelevant but time-dependent variables. This results in x(t) being time-dependent, with different time dependences \(x_1(t)\) (Fig. 1(a)) and \(x_2(t)\) (Fig. 1(b)) in the two stable states. The challenges we face in detecting the critical transition at \(t = 0\) (Fig. 1(c)) arise from a combination of x(t) being time-dependent, and the time-dependent noise built into it. As pointed out by Scheffer et al., this time-dependence of the noise has the following universal features6,7: variance, skewness, and autocorrelation increase (Fig. 1(d),(f),(h)) as we approach the critical point and thereafter decrease (Fig. 1(e),(g),(i)) as we recede from the critical point. In more extreme situations, we can even encounter the phenomenon of flicker, where the complex system in stable state 1 spends brief periods in stable state 2 and vice versa, shortly before and after the critical transition. If \(x(t) \approx f(\Phi (t))\), and the noise or its increment is weakly nonstationary, we can model the states of a complex system by different statistical distributions, and use various time series segmentation (or change point detection) methods8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 to determine when these sudden changes occur. Alternatively, we can model the time series data in terms of a hidden Markov model16,17,18,19,20, and infer change points from the posterior probabilities. These methods can identify change points precisely, but require us to make model assumptions that are difficult to justify when x(t) is time-dependent everywhere, and the noise is highly nonstationary. Another approach to determine state changes is to compute average quantities over time windows21,22,23,24,25,26. By sliding these time windows incrementally, we can plot the change of the average quantities over time, and identify the likely times when changes occur. These methods do not require any assumptions on the time series data. However, because they require averaging over time windows, they are imprecise, with the time resolution being constrained by the size of the time windows used. They are also unlikely to provide good estimates of the magnitude of the sudden change during the critical transition.

Recently, we studied the spectral properties of graph Laplacians of various market cross sections of stocks at different correlation levels, and found that in normal market periods, this sequence of eigenvalues is gapless. On the other hand, when the time window includes the short market crashes, this sequence of eigenvalues is gapped27. When we compare the spectral sequences of a time window that just included the market crash, and one that just excluded the market crash, we find that the former is gapped while the latter is gapless. This suggests that the gap in the Laplacian spectra is a highly sensitive indicator for the market state, and can be used as an order parameter. Additionally, the noise associated with the spectral gap is highly suppressed, because it is computed over the cross section of S&P 500 component stocks. Nevertheless, there is no value in having a highly sensitive indicator, when we do not have the temporal precision to tell the start and end of market crashes. This is why in a follow-up study, we developed a method for obtaining precise model-free estimates of these change points by using a pair of time windows28. By multiplying the integrated signal from the left time window with the integrated signal from the right time window, we obtain a product signal that accurately determines sharp changes with high temporal resolution. This spectral gap method can be used to detect critical transitions in other complex systems, so long as time series cross section data or interactions network data is available. However, the method is computationally heavy, and does not work on individual noisy time series. This led us to experiment with a simpler model-free method using a sliding pair of time windows to detect critical transitions from the time series data generated by complex systems. We call this method quasi-differentiation, because the signal obtained by taking the difference between the right and left time windows resembles the derivative of the time series after smoothing. While we were experimenting with the quasi-differentiation of noisy time series, we realised that the method not only detects sudden changes, but also approximate slow changes in a noisy time series very well after we perform an ordinary integration of the quasi-derivative time series. We call this model-free method to discover the slowly-varying part of a noisy time series integrated quasi-differentiation. The literature on smoothing methods is vast. By far the most common method to smooth a noisy time series f(t) is to compute a running average or moving average29

over \(2p+1\) equally-weighted data points centered at t. Other weighting schemes are possible, e.g., weights that decay as an exponential30 or as a Gaussian31 away from t. Other popular spline-based smoothing methods include the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing(LOWESS)32,33, and the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing(LOESS)34. The former uses locally linear regression, whereas the latter uses locally quadratic regression. In the most general sense, smoothing methods all involve integral transforms of the form

where \(w(t-t')\) is a parameter-free function of \(t-t'\)for non-parametric smoothing, or a locally optimized spline function for parametric smoothing. Other smoothing methods based on integral transforms include Fourier transform with low-pass filtering35,36, and the wavelet transform37,38.

Unfortunately, methods designed to detect sudden changes do not track slow changes well, while methods meant to track slow changes fail in general to detect sudden changes. Our contribution in this paper is therefore a two-step process: (1) quasi-differentiation to detect sudden changes (critical transitions in complex systems), (2) integrated quasi-differentiation to smooth the rest of the time series. To demonstrate the utility of our method, we will describe in the Methods section how the difference between the integral of a right window \((t, t+w)\) and that of a adjoining left window \((t-w, t)\) for a function f(t) resembles mathematically the derivative \(f'(t)\). We then show that the integration over the left and right windows leads to noise reduction, while their difference preserves the mathematical structure of a derivative. Through the use of toy models, we demonstrate how the method of quasi-differentiation reliably detect sudden changes in their noisy time series. We also describe how the quasi-derivative of a noisy time series can then be integrated to approximate f(t), with both sudden and slow changes included. At the end of the Methods section, we describe the theoretical basis behind quasi-differentiation. Thereafter, we organise the Results section into two parts, to demonstrate the versatility of quasi-differentiation and integrated quasi-differentiation. In the first subsection, on Identifying Sudden Changes, we apply quasi-differentiation to the daily returns time series of the DJIA between 2003 and 2023, and show how the quasi-derivatives of its mean and variance allow us to accurately time the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crashes. In this subsection, we also show how to use a heat map to show the quasi-derivatives obtained using different window widths w. Then, in the second subsection, on Identifying Slow Changes, we show the integrated quasi-derivatives of the mean and variance of the daily returns time series of the DJIA. For the latter, we find strong peaks coinciding with the Oct 2008 and Mar 2020 crashes, but also weaker peaks that can be understood as market corrections. For the former, we find the mean returns looking like the derivative of a negative peak for the Oct 2008 and Mar 2020 crashes. This is expected. After the Oct 2008 crash, there are strong oscillations in the mean returns that are reminiscent of aftershocks following strong earthquakes39,40. Finally, in the Discussion section, we explain how the quasi-differentiation method can accurately determine the duration of a state of a complex system, over a broad range of window width w, by using the fact that the start and end of this state can be precisely determined. We then illustrate how the methods of quasi-differentiation and integrated quasi-differentiation can be used to obtain point estimates of quantities that normally require a time window to compute. We do this for the Hurst exponent and the linear cross correlation, and highlight the surprises found.

Methods

In this paper, we refer to f(t) and its integral \(F(t) = \int _a^t f(s)\, ds\) as functions. When these are evaluated over a discrete set of times \(\{t_1, t_2, \dots , t_i, \dots , t_N\}\), we refer to their values \(\{f(t_1), f(t_2), \dots , f(t_i), \dots , f(t_N)\}\) and \(\{F(t_1), F(t_2), \dots , F(t_i), \dots , F(t_N)\}\) as the time series of f(t) and F(t). f(t) and F(t) can be any function and anti-derivative pair, but in this paper we will illustrate our method using mainly

and

as examples of functions (and their time series, with and without noise) that change sharply at \(t = 0\).

(a) The plots of \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) (red), its first derivative \(f'(t) = \operatorname {sech}^2(t)\) (green), and its second derivative \(f''(t) = -2 \tanh (t) \operatorname {sech}^2(t)\) (blue). (b) The plots of a noisy time series (red), obtained by adding Gaussian noise with standard deviation \(\sigma = 0.2\) to \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\), and its numerical derivative computed using the forward difference (blue) in Equation (5).

Derivative of a noise-free and noisy time series

Consider \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\), which changes from a steady long-time value of \(f(t \ll 0) \approx -1\) to a steady long-time value of \(f(t \gg 0) \approx +1\), between \(t = -1\) and \(t = +1\). We show f(t) as well as its first and second derivatives in Fig. 2(a).

By definition, the derivative \(f'(t)\) of f(t) is

This is written in terms of a forward difference. For differentiable functions, it is also possible to write \(f'(t)\) in terms of a backward difference \(f(t) - f(t-h)\). Unfortunately, if we use the forward difference in Equation (5) (or the backward difference) to numerically differentiate a noisy version of \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\), there is no sign of the sharp change at \(t = 0\) in the numerical derivative, as seen in Fig. 2(b). To detect the change in \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\), one normally resorts to smoothing operations before performing numerical differentiation. The choice of any particular smoothing method, however, is difficult to justify.

In contrast, a simple numerical differentiation for \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\) will hint at the sharp change at \(t = 0\) (reliably so only when \(\sigma \ll 1\)), but the derivative does not exist at \(t = 0\) for \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\), since it is not continuous here.

Quasi-differentiation with a pair of time windows

The noise-free case

Let us again start with \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) as a noise-free time series changing rapidly at \(t = 0\) (compared to the asymptotes \(\lim _{t \rightarrow -\infty } f(t) = -1\) and \(\lim _{t \rightarrow +\infty } f(t) = +1\)). As shown in Fig. 3(a), let us also define a sliding pair of time windows \((t-w,t)\) (blue) and \((t,t+w)\) (green), and examine the information they can extract from f(t).

(a) The pair of time windows \((t-w,t)\) (blue shaded regions) and \((t,t+w)\) (green shaded regions), shown at different values of t for \(w=1\), superimposed on \(f(t)=\tanh (t)\) (red). (b) The function \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) (red) and its derivative \(f'(t) = \operatorname {sech}^2(t)\) (green), and its quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w f(t)\) (blue) obtained using a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\).

There are many ways to define the signals generated by the left and right time windows. For noise-free signals, it is most intuitive to define the left and right integrated signals

Since the anti-derivative of \(\tanh (t)\) is \(\ln (\cosh (t))+C\), we can therefore write the left and right integrated signals as

Thereafter, instead of a product signal we used in our earlier study28, we define a difference signal

In Fig. 3(b) we see that \(\Delta I(t)\) for \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) is very close to its actual derivative \(f'(t) = \operatorname {sech}^2(t)\).

For \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\) the difference signal is even easier to compute. When \(t<-w\) or \(t>w\), the pair of sliding windows has no overlap with the sharp change at \(t=0\). Hence, \(\Delta I(t)=0\). On the other hand, if \(-w<t<0\), only the right window overlaps with \(t=0\). Hence, \(I_L (t)=-1\), while \(I_R (t)=2t/w+1\), and \(\Delta I(t) = I_R(t) - I_L(t) = 2(1+t/w)\). Similarly, if \(0<t<w\), only the left window overlaps with \(t=0\). Hence, \(I_R(t)=1\) while \(I_L(t)=2t/w-1\), and \(\Delta I(t) = I_R (t) - I_L(t)=2(1-t/w)\). Putting it all together, we see therefore that

This is a triangular function with its peak at \(t=0\), and a width of 2w.

In general, if F(t) is the anti-derivative of f(t), then

and

This resembles the discrete second derivative \(F''(t)\) of F(t), or equivalently the discrete first derivative \(f'(t)\) of f(t). We can therefore think of this procedure as quasi-differentiation, and \(\Delta I(t)\) as a quasi-derivative. In this paper, we will apply quasi-differentiation to many different functions. To distinguish between these quasi-derivatives, we will denote the quasi-derivative of f(t) as \(\Delta _w f(t)\) instead.

The noisy case

The result shown in Fig. 3(b) looks like an unnecessarily cumbersome way to approximate the first derivative of the time series of \(\tanh(t)\), especially when the results depend on the width of the time window used. However, if the time series data is noisy, the integration becomes helpful, as it averages out the noise. In this subsection, we will illustrate the utility of quasi-differentiation with a pair of sliding windows, first with a noisy version of \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\), and then with a noisy version of \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\).

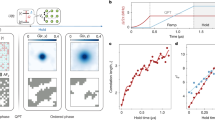

(a) A noisy time series f(t) (red) obtained by adding Gaussian noise with \(\sigma = 0.2\) to the function \(\tanh (t)\), and its quasi-derivative (blue) obtained by averaging f(t) over a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\). As we can see, the quasi-derivative compares favorably with the analytical derivative \(\operatorname {sech}^2(t)\) (green). (b) A noisy time series f(t) (red) obtained by adding Gaussian noise with \(\sigma = 0.2\) to the signum function \(\operatorname {sgn}(t)\), and its quasi-derivative (blue) obtained by averaging f(t) over a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\). We also show the quasi-derivative of the noise-free \(\operatorname {sgn}(t)\) in green. As we can see, the noisy quasi-derivative is almost identical to the noise-free quasi-derivative, for this level of noise in the time series. (c) A noisy time series f(t) (red) consisting of Gaussian noise with \(\sigma _1 = 0.5\) for \(t \le 0\) and \(\sigma _2 = 2\) for \(t>0\). For a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\), the quasi-derivatives of its mean and variance are shown in green and blue. We also show the quasi-derivative of its variance for \(w=2\) (magenta).

In Fig. 4(a), we show \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) contaminated by a Gaussian noise with \(\sigma = 0.2\) (as was shown in Fig. 2(b)). The quasi-derivative obtained using a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\) is also shown. As we can see, \(\Delta _w \tanh (t)\) agrees very well with \(\operatorname {sech}^2(t)\). Next, let us look at the quasi-derivative of a noisy version of the signum function, obtained by adding Gaussian noise with \(\sigma = 0.2\) to \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\). In Fig. 4(b), we show its quasi-derivative obtained using a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\). This compares very well against the analytical solution obtained in Equation (9).

In the econometrics literature, econometricians are not only concerned with a sudden change in the mean, which is the example we showed above, but also a sudden change in variance (or both mean and variance)41,42. Therefore, in this second example on step function changes, let us introduce the time series

where z(t) is sampled from the standard normal distribution with \({\left\langle {z(t)}\right\rangle } = 0\) and \({\left\langle {z^2(t)}\right\rangle } = 1\), \(\sigma _1 \ne \sigma _2\) are distinctly different standard deviations before and after \(t=0\).

In Fig. 4(c), we show the noisy time series generated by Equation (12) with \(\sigma _1 = 0.5\) and \(\sigma _2 = 2\) in red. We also show the quasi-derivative of its mean

in green. As expected, \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) cannot tell us that there is a sudden change in variance at \(t=0\). However, because quasi-differentiation is defined in terms of the difference between two integrals, we have a lot of flexibility in what we wish to evaluate using the left and right windows.

Therefore, instead of using left and right windows to define the quasi-derivative of the mean \(\mu (t)\), we can use \(I_L(t)\) and \(I_R(t)\) to define the quasi-derivative of the variance

of f(t), where \(\overline{f}_L\) is the mean of f(t) in the left window \((t-w, t)\), and \(\overline{f}_R\) is the mean of f(t) in the right window \((t, t+w)\). From Fig. 4(c), we see from the blue curve that the sudden variance change at \(t=0\) can be easily detected using a pair of sliding windows with width \(w=1\). However, we also see a spurious signal over \(3<t<4\) where we did not introduce any change of variance. This is a problem with statistical significance, and can be alleviated using a larger window width \(w=2\), whose quasi-derivative is shown in magenta. There is a price to pay, though: the width of the quasi-derivative peak for \(w=2\) is twice as large as that for \(w=1\).

Re-integrating a quasi-derivative

When we are given \(f'(t)\), we can recover f(t) by integrating the derivative \(f'(t)\). Since the quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w f(t)\) so closely resembles \(f'(t)\), if we integrate \(\Delta _w f(t)\) we will also obtain a function \(f_w(t)\) that closely resembles f(t). Let us refer to \(f_w(t)\) as the integrated quasi-derivative of f(t).

To see how this works, consider \(f(t) = At + B\), whose quasi-derivative is \(\Delta I(t) = A w\) (see Fig. 5(a) for \(f(t) = 2t + 3\) and \(w = 1\)). If we now integrate \(\Delta I(s)\) from \(s = 0\) to \(s = t\), we then have

To recover the original function, we see therefore that

The integrated quasi-derivative is shown in orange in Fig. 5(b).

As we can see from Fig. 5 and Equation (16), we have recovered the exact slope \(A = 2\) for \(f(t) = 2t + 3\), but not the intercept \(B = 3\). This is because we did not specify the initial condition when we integrate \(\Delta _w f(t)\). We cannot do this, because the original time series \(f(t_k)\) is noisy, and therefore we do not know what initial condition to use. An alternative condition we can impose on the integrated quasi-derivative is

which allows us to approximate f(t) as

Here, the time averages can be computed directly from Equation (16) and the time series \(f(t_k)\).

(a) The integrated quasi-derivative \(f_w(t) - \overline{f_w} + \overline{f}\) (orange) of \(f(t) = 2t + 3\) (blue) over the interval \(-5 \le t \le 5\), after correcting for the time averages of f(t) and \(f_w(t)\). (b) The integrated quasi-derivative \(f_w(t) - \overline{f_w} + \overline{f}\) (blue), compared to \(f(t) = 2t + 3\) (red) with uncorrelated Gaussian noise with standard deviation \(\sigma = 0.5\).

Once this correction has been made, we see from Fig. 6(a) that the integrated quasi-derivative \(f_w(t) - \overline{f_w} + \overline{f}\) agrees exactly with f(t) over the interval where quasi-differentiation was carried out. From Fig. 6(b), we see that the integrated quasi-derivative \(f_w(t) - \overline{f_w} + \overline{f}\) is practically unchanged when f(t) is contaminated by uncorrelated Gaussian noise with standard deviation \(\sigma = 0.5\).

In Supplementary Section S1, we show the average integrated quasi-derivative \(\langle f_w(t)\rangle\) for an ensemble of \(S=1000\) noisy realizations of \(f(t) = 2t + 3\) with \(\sigma = 0.5\). As we can see from Supplementary Figure S1, \(\langle f_w(t)\rangle\) is indistinguishable from \(f(t) = 2t + 3\), while the standard error of \(\langle f_w(t)\rangle\) is miniscule. In this Supplementary Section, we also show the distributions of integrated quasi-derivatives \(f_w(t)\) for \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) (Supplementary Figure S2), \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\) (Supplementary Figure S3), and a variance shift from \(\mu _1 = 0\) and \(\sigma _1 = 0.5\) for \(t < 0\) to \(\mu _2 = 0\) and \(\sigma _2 = 2.0\) for \(t \ge 0\) (Supplementary Figure S4 and Supplementary Figure S5) over \(S = 1000\) noisy realizations.

Theoretical justifications

Let \(\{f(t_i) + \sigma z(t_i)\}_{i=1}^N\) be the sum between a deterministic time series \(\{f(t_i)\}_{i=1}^N\) and a stochastic noise \(\{\sigma z(t_i)\}_{i=1}^N\). Suppose the standard deviation \(\sigma\) of this stochastic noise is stationary, i.e., \(\sigma\) does not depend on time. Then, when we write the left and right integrated signals as

using the fact that the left window ends at \(t_i\) (and so the time points are \(t_k = t_i - k\Delta t\), \(k = 0, \dots , N-1\)), the right window starts at \(t_i\) (and so the time points are \(t_k = t_i + k\Delta t\), \(k = 0, \dots , N-1\)), \(w = N\Delta t\) and \(\int _a^b [f(t) + \sigma z(t)]\, dt = \sum _{k=0}^{N-1} [f(t_i \pm k\Delta t) + \sigma z(t_i \pm k\Delta t)]\, \Delta t\), where \(\Delta t = t_{k+1} - t_k\) for all values of \(0 \le k \le N-1\).

If we take the differences in \(I_L(t_i)\) and \(I_R(t_i)\) separately for the deterministic function f(t) and the stochastic noise \(\sigma z(t)\), we will find that

and

If z(t) is statistically stationary, then

and hence

The variances of the sums over noise terms are

making use of \({\left\langle {z^2(t)}\right\rangle } = 1\) and \({\left\langle {z(t)z(t')}\right\rangle } = 0\). Therefore, the dispersion of \(\Delta I(t_i)\) about \({\left\langle {\Delta I(t_i)}\right\rangle }\) is \(O(\sigma /N)\), which is significantly smaller than \(\sigma\). This reduction of noise variance applies even if the noise is not too strongly serially correlated, i.e., \({\left\langle {z(t)z(t+\Delta t)}\right\rangle } = \rho < 1\). In fact, if the noise term \(\sigma (t) z(t)\) has a time-varying point-wise variance \(\sigma ^2(t)\), if \(\sigma ^2(t) < \infty\) or its time average \(\overline{\sigma ^2(t)}\) exists, and is time-independent beyond some time window w. On the other hand, if the stochastic noise is drawn from an ARCH process, this method will not work.

In the Results and Discussion sections, we saw the integrated quasi-differentiation method recovering a slowly varying function \(f_w(t)\) that is oscillatory. What happens if we quasi-differentiate \(f(t) = \cos \frac{2\pi t}{T}\) using different window widths w? As we slide the paired time windows along, the left and right integrated signals would both be of the form

When we take their difference, we find

When this is re-integrated, we have

which we see is an amplitude function

multiplying \(f(t) = \cos \frac{2\pi t}{T}\).

In terms of the ratio \(T/\pi w\), we can write the amplitude function as

When \(w \ll T\), \(\frac{\sin ^2\frac{\pi w}{T}}{\left( \frac{\pi w}{T}\right) ^2} \approx 1\), \(A(w, T) \approx 2\pi /T\) is a constant, and we can recover f(t) from \(f_w(t)\) by \(f(t) = (T/2\pi ) f_w(t)\). In the limit of \(w \gg T\), \(\frac{\sin ^2\frac{\pi w}{T}}{\left( \frac{\pi w}{T}\right) ^2} \sim \left( \frac{T}{w}\right) ^2\), thus \(A(w, T) \sim \left( \frac{T}{w}\right) ^2\). In this limit of \(w \gg T\), \(|f_w(t)| \ll |f(t)|\) is suppressed, and we can think of the oscillatory behavior in f(t) becoming self-averaged in \(f_w(t)\).

In principle, if f(t) consists of a single sinusoidal behavior, we can recover it from \(f_w(t)\) even in the limit of \(w \gg T\). However, if

can be written as a superposition of different frequency components, the amplitude function A(w) would have no closed form, meaning we cannot easily invert \(f_w(t)\) to get f(t). Nevertheless, it should remain clear that \(A(w) \gtrsim 1\) for \(w < T\), while A(w) is suppressed for \(w> T\). In other words, the method of integrated quasi-differentiation with window width w acting on f(t) has a similar effect to the application of a low-pass filter with frequency cutoff \(2\pi /w\) to f(t) (without performing Fourier transformation).

In Supplementary Section S2.1, we illustrate the low-pass filtering by integrated quasi-differentiation of a single sinusoidal function \(x(t) = \sin \left( \sqrt{2}\pi t + e\right)\), and compare the amplitude ratio \(x_w(t)/x(t)\) against the theoretical ratio shown in Equation (30) (see Supplementary Figure S6). Thereafter, in Supplementary Section S2.2 we plot the heat map for the integrated quasi-derivative \(x_w(t)\) of the sum of three sinusoidal functions with periods \(T_1 = 1.0\), \(T_2 = 3.0\), and \(T_3 = 10.0\), as well as the heat map of the Fourier transform \(|\tilde{x}_w(\nu )|\), to show that the two fastest sinusoidal components are suppressed when \(w> 1\) and \(w> 3\) respectively (see Supplementary Figure S7).

Results

Identifying sudden changes

To demonstrate the utility of the quasi-differentiation method for detecting sudden changes, we downloaded 20 years of daily closing prices of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) index between 31 Dec 2002 and 31 Dec 2023 from https://www.wsj.com/market-data/quotes/index/DJIA/historical-prices in the form of a comma-separated values (csv) file. We then used a Python script to extract the dates and daily closing prices, before computing the fractional daily returns from 2 Jan 2003 to 29 Dec 2023 (totaling 5,285 trading days). In Fig. 7(a), we show the daily closing prices of DJIA in blue and the fractional daily returns in red, whereas in Fig. 7(b), we show the daily closing prices of DJIA in red, the quasi-derivative of the mean \(\Delta _w\mu (t)\) in green, and the quasi-derivative of the variance \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) in blue. With a time window of \(w = 100\) days, \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) appears to be rather noisy, while \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) is significantly smoother. Over mid-2008 to end-2009, there is a significant drop in the quasi-derivative of the daily return, followed by a significant rise, whereas in the quasi-derivative of the variance, we find a significant rise followed by a significant drop. The pairing of positive and negative peaks tells us that we are not seeing the quasi-derivative of a step-like change, but that of a pulse (see second derivative of \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) in Fig. 2(a)). Thus over this period, the daily mean has a negative peak, while the variance has a positive peak. Over 2020, the same features were observed. These two market crashes in 2008/2009 and 2020 are marked as yellow shaded regions in Fig. 7(b).

(a) The daily closing prices (blue) and daily returns (red) of the DJIA, between 2 Jan 2003 and 29 Dec 2023 (a total of 5,285 trading days). (b) The quasi-derivatives of the mean (green) and variance (blue) for the daily returns of the DJIA between 2 Jan 2003 and 29 Dec 2023 (5285 trading days, obtained using a pair of sliding time windows with width \(w=100\) trading days. Also shown in red is the daily closing price of the DJIA, while the zero value of the quasi-derivatives of the mean and the variance is shown as the blue dashed line. In this figure, the variance quasi-derivative was multiplied by 5, so that it is visually comparable to the mean quasi-derivative. Based on these two quasi-derivatives, we are most confident of the two sudden events marked as yellow shaded regions.

As always, when we work with a time window, we always worry about which time window width w is the best. To avoid such a question, we can compute the quasi-derivatives over all widths, like what is done for wavelet transforms43,44,45 or windowed Fourier transforms46,47,48. This is also in line with the multiscale analysis that we have been doing lately27,49,50. We do this for \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) and \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) for window sizes from \(w=20\) to \(w=250\), effectively covering the time scales from one trading month to one trading year, and present the results as heat maps in Fig. 8. As expected, we see from Fig. 8(a) that \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) is very noisy for small window sizes, and becomes smoother only after \(w> 100\) trading days. As the window size increases, we expect the most reliable features in \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) to become wider. Indeed, this is what we see for the 2008/2009 and 2020 market crashes. But while the positions of many weaker peaks change with window sizes, the centers of the 2008/2009 and 2020 features remain the same. This allows us to time the first market crash to Oct 2008, associating it with the Lehman Brothers crash and the broader Global Financial Crisis, and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash. In contrast, the situation with \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) is cleaner (see Fig. 8(b)). The peaks associated with the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers crash and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash are extremely strong, showing clear dependence on the size of the time windows. The next strongest variance event occurred at the end of 2011, supposedly a market correction triggered by the S&P revising the US credit rating from AAA to AA in Aug 2011, while even weaker events can be seen in 2015, 2018, and 2019. These are all a rise in variance before a market crash, and a fall in variance after the market crash.

Heat map visualizations of (a) the quasi-derivative of the mean \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) and (b) the quasi-derivative of the variance \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) of the daily returns of the DJIA between 2 Jan 2003 and 29 Dec 2023 (5285 trading days), obtained using sliding time windows with widths \(20 \le w \le 250\) trading days. In this figure, the daily closing price of the DJIA is shown in magenta.

After reviewing the theory of continuous and discrete wavelet transformations in Supplementary Section S5 (see Supplementary Figure S14 and Supplementary Figure S15), and the connection between \(\Delta _w f(t)\) and the Haar wavelet transform of f(t), we compare Fig. 8(a) against the scalogram of the continuous Morlet wavelet transform in Supplementary Figure S16 and Supplementary Figure S17 to show how the heat map of the integrated quasi-derivative \(\mu _w(t)\) emphasizes information different from the former.

Identifying slow changes

In the quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) of the DJIA daily returns time series, we find the expected structure for the derivative of a negative pulse (negative peak followed by a positive peak in Fig. 7(b), or blue followed by red in the heat map shown in Fig. 8(a)) during the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers crash and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash. However, unlike the quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w \sigma ^2(t)\) of the variance, which is more or less quiet away from these two market-level events, \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) shows strong oscillation-like fluctuations everywhere. This suggests that the DJIA daily return is not stationary, but is strongly time-dependent.

(a) The integrated quasi-derivative of the mean (shown in green) and (b) integrated quasi-derivative of the variance (shown in blue) of the DJIA daily returns between 2 Jan 2003 and 29 Dec 2023 (5285 trading days), obtained using sliding time windows with width \(w = 100\) trading days. Also shown in red is the daily closing price of the DJIA, while the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers crash and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash are marked as yellow shaded regions. In this figure, the blue dashed line indicates the zero integrated quasi-derivative value for both the mean (a) and variance (b).

We can recover such time-dependences approximately using the method of integrated quasi-differentiation. If we think of the time series f(t) of the DJIA daily returns as comprised of a slowly-varying part, and a rapidly-varying stochastic part that is statistically stationary or self-averaging, we then see from Fig. 9(a) that the integrated quasi-derivative \(\mu _w(t)\) of the DJIA daily return is a good approximation for the slowly varying part. This is consistent with our understanding of integrated quasi-differentiation acting as a low-pass filter, suppressing time series variations of scales w and lower. In fact, we observe that \(\mu _w(t)\) is strongly oscillatory. When a window width of \(w = 100\) trading days is used, the period between adjacent peaks (which occur near the end of the first quarter) is approximately one year. This opens the door to further studies on seasonality51,52 and calendar effects53 in stock markets, based on the integrated quasi-derivative approximation \(\mu _w(t)\) to the slowly varying part of financial returns. Furthermore, \(\mu _w(t)\) is not always positive, but is sometimes negative. Finally, we are used to talking about daily returns of approximately 1%–2%. In Fig. 9(a), the slowly varying \(\mu _w(t)\) of the DJIA daily return is approximately 10 times smaller. This suggests that most of the observed daily returns can be attributed to the stochastic part (the high-frequency part).

In contrast, we see from Fig. 9(b) that the integrated quasi-derivative of the variance \(\sigma _w^2(t)\) is much smoother, made up of a consistent baseline of \(\sigma _w^2(t) \approx 0.00005\), and peaks on top of it. Again, this is lower than the typical day-to-day variations of about 1% in the US stock market, because the higher-frequency components it contains will be suppressed. The two strongest peaks can be associated with the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers and Mar 2020 COVID-19 crashes, but there are also weaker peaks whose positions coincide with what appears to be market corrections in the S&P 500. Finally, even though the variance cannot be negative, \(\sigma _w^2(t)\) fell convincingly below the baseline over much of 2017. Visually, we can see the S&P 500 growing almost noiselessly in this year.

Discussion

When we introduced quasi-differentiation in the Methods section, we focused on the permanent transition from \(f(t) = -1\) to \(f(t) = +1\) seen in \(f(t) = \tanh (t)\) or \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t)\). Realistically speaking, such permanent mean shifts are not common. Instead, it is more common to find a transition from state a to state b, and then after some duration, a transition from state b back to state a, or to a new state c. Depending on how long this duration T is, compared to the window width w used in the quasi-differentiation, we should see either two independent transitions (for \(w \ll T\)), or a single pulse (for \(w \gg T\)). To better understand this change in perspective as we increase w, we show in Fig. 10(a) how the quasi-derivatives of \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t+2.5) - \operatorname {sgn}(t-2.5)\) change with t, as we vary \(0.5 \le w \le 4.5\). As we can see, when \(w \ll T = 5\), the quasi-derivative consists of a positive peak at \(t = -2.5\) (the function rising from \(f(t) = 0\) to \(f(t) = 2\)), a negative peak at \(t = +2.5\) (the function falling from \(f(t) = 2\) to \(f(t) = 0\)), and a flat region between them. When \(w \gtrsim T\), the quasi-derivative changes nearly continuously between the positive and negative peaks at \(t = \mp 2.5\) respectively. The two regimes can be seen more clearly from the heat map in Fig. 10(b). Based on these two figures, there are then various ways to determine the duration T: (1) by using the fact that the position of the positive quasi-derivative peak is the rising edge of f(t), while the position of the negative quasi-derivative peak is the falling edge of f(t); (2) by finding the rising and falling edges of f(t) in the limit of \(w \rightarrow 0\); (3) if \(t^+\) is the outer edge of the positive peak, and \(t^-\) is the outer edge of the negative peak, we can compute the duration to be \(T = |t^+ - t^-| - 2w\). Naturally, we can use these three estimates of T to cross-validate each other. One of these three indicators may be better than the others, if the pulse rises and falls off smoothly.

(a) The quasi-derivative of \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t+2.5) - \operatorname {sgn}(t-2.5)\) (graph shaded blue at \(w = 5\)) for window widths \(0.5 \le w \le 4.5\), in steps of \(\Delta w = 0.5\). (b) The heat map of quasi-derivative of \(f(t) = \operatorname {sgn}(t+2.5) - \operatorname {sgn}(t-2.5)\), with \(\Delta _w f(t)> 0\) being red, \(\Delta _w f(t) < 0\) being blue, and \(\Delta _w f(t) \approx 0\) being green.

Next, let us stress the flexibility having a time window affords us. In the Results section, we have already demonstrated our ability to compute point-wise estimates of a slowly varying mean return

where the difference between definite integrals within the square bracket represents the quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w \mu (t)\) of the mean return, and the outermost indefinite integral represents the integration we must do to obtain the integrated quasi-derivative described in the Methods section. If instead of the mean return, we would like to compute the variance of the return, our integrated quasi-derivative becomes

As we can see, because we are using time windows, instead of just computing the mean of the return time series \(r(t_i)\), we can also compute other statistical moments (such as the skewness, kurtosis, etc.) of the time series data.

Here, let us illustrate how we can apply the integrated quasi-differentiation method to two quantities where point estimates are not normally, or not possible to be computed. The first is the Hurst exponent (see simulated time series with different Hurst exponents in Supplementary Figure S8), which was historically estimated by Harold Edwin Hurst using the R/S method54,55. Since then, many methods to estimate a stationary exponent have been added to the list, including time domain methods like detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA)56, Higuchi’s method57, frequency domain methods like the periodogram method58, modified periodogram method59, Whittle’s estimator60, and wavelet methods61. Recently, Gómez-Águila et al. proposed a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic-based method, which can be used to estimate the Hurst exponent from any estimator based on stationary segments62. In his paper, Gómez-Águila et al. tested the method on the Generalized Hurst exponent (GHE) method63,64, the TTA method65 and TA method66, as well as the GM2 method67 and FD method68.

In Fig. 11, we compared the results obtained using the R/S method of Hurst54,55 and the KS-GHE(1) method of Gómez-Águila et al.62 to compute the Hurst exponent H in the left and right time windows, take their difference to obtain the quasi-derivative \(\Delta _w H(t)\), and finally performing integration to get the integrated quasi-derivative \(H_w(t)\). As we have explained in the Results and Methods section, \(H_w(t)\) approximates the slowly varying part of the Hurst exponent. Therefore, if H(t) is stationary, \(H_w(t)\) would be a horizontal line. Indeed, suspecting the converse, econophysicists have computed the time-dependent Hurst exponent using DFA69, or simple sliding time windows70,71,72,73,74,75,76. In these previous studies, it is common to find \(H> 0.5\) in the normal market state, but the Hurst exponent dropping to or below \(H = 0.5\) during financial crises76. However, when sliding windows are used, events cannot be timed precisely to demonstrate these behaviors of H(t) convincingly.

The integrated quasi-derivative \(H_w(t)\) of the Hurst exponent of the daily returns of DJIA, using sliding windows with widths (a) \(w = 128\) and (b) \(w = 256\) days. In both figures, the blue curve is \(H_w(t)\)estimated using the R/S method54,55, while the green curve is \(H_w(t)\)estimated using the KS-GHE(1) method62. The time periods where the two methods agree qualitatively with each other are shown as gray shaded regions. We also mark the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers crash and the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash as yellow shaded regions.

In Fig. 11, we see that \(H_w(t)\) is strongly time-dependent, whichever method it was estimated with. In fact, estimates from the two methods agree with each other qualitatively over many time periods (shaded in gray), and quantitatively over brief periods when the DJIA experienced strong growth. Otherwise, the R/S estimate is systematically larger than the KS-GHE(1) estimate, and the two disagree with each other most strongly (both qualitatively and quantitatively) during market crashes and the periods immediately following them. According to the KS-GHE(1) estimate, the Oct 2008 Lehman Brothers crash occurred when H(t) first fell below \(H = 0.5\), and the DJIA started recovering when H(t) first rose above \(H = 0.5\). However, there were other times when the KS-GHE(1) estimate of H(t) fell below \(H = 0.5\) with no signs of market crashes. More importantly, the KS-GHE(1) estimate of H(t) was above \(H = 0.5\) when the Mar 2020 COVID-19 crash occurred, and also when the DJIA rebounded sharply shortly thereafter. This suggests that local minima of H(t) might be associated with endogeneous market corrections (or market crashes if the local minima are sufficiently deep), a signature that would not accompany exogeneous market crashes.

Although the KS-GHE(1) method has been demonstrated to be the most reliable way to estimate the Hurst exponent H, the standard error associated with the this estimate is approximately \(\Delta H = 0.05\) when we apply it to time series data with \(w = 2^7 =128\) data points62. This standard error falls slightly to \(\Delta H = 0.04\) when we double the length of the time series data to \(w = 2^8 = 256\) data points. One way to improve the accuracy of the KS-GHE(1) method is to go beyond \(q = 1\) for the estimation of H. The multivariate test statistic analogous to the univariate KS statistic has been recently derived by Naaman77, but implementing this would be well beyond the scope of this paper. The other way would be to increase the window size to \(w = 2^{16} = 65536\) to get \(\Delta H < 0.01\). Unfortunately, even with a window size of \(w = 256\) (approximately one trading year), many features seen in \(H_w(t)\) estimated using \(w = 128\) (approximately half a trading year) have been smoothed over. Larger window sizes would lead therefore to too much information loss.

In Supplementary Section S3, we perform rigorous statistical tests of \(H_w(t)\) obtained using integrated quasi-differentiation against various time-dependent Hurst exponents H(t). We start with a piecewise constant \(H(t) = 0.3\) for \(1 \le t \le 5,000\), and \(H(t) = 0.7\) for \(5,001 \le t \le 10,000\) in Supplementary Section S3.2, to show the distributions of estimates \(H_w(t)\) from \(S = 100\) realizations of H(t) for \(w = 128\) and \(w = 256\). As shown in Supplementary Figure S9, the standard error of \(H_w(t)\) is smaller for \(w = 256\) than it is for \(w = 128\), but the ensemble average \(\langle H_w(t)\rangle\) for \(w = 128\) approximates more closely the sudden change in H(t) at \(t = 5,000\). The piecewise constant H(t) can be simulated using the fbm Python package, but not so for H(t) with other time dependences. Therefore, in Supplementary Section S3.3 we reviewed the statistical theory behind fractional Brownian motion, and how a fractional Brownian motion time series X(t) can be simulated for any constant Hurst exponent H using the Cholesky method. We then reviewed in Supplementary Section S3.4 the statistical theory behind multifractional Brownian motion with the most general time-dependent Hurst exponent H(t), for \(H(t) = 7 \times 10^{-5} t + 3 \times 10^{-5} (10,000 - t)\) in Supplementary Section S3.4.1 (see Supplementary Figure S10) and \(H(t) = 0.5 - 0.2\sin (2\pi t/10,000)\) in Supplementary Section S3.4.2 (see Supplementary Figure S11), and show that their time series can also be simulated using the Cholesky method. For both examples, we compare the distributions of \(H_w(t)\) for \(S = 100\) sample time series against H(t). The agreements are acceptable (H(t) lies entirely within the standard errors of \(H_w(t)\), and the ensemble average \(\langle H_w(t)\rangle\) closely approximates H(t) for both \(w = 128\) and \(w = 256\). This gives us confidence that \(H_w(t)\) shown in Fig. 11(obtained using the KS-GHE(1) method) is a feature of the data, and not an artifact of the integrated quasi-differentiation method. In this sense, we believe our method is an useful addition to the growing literature on estimating multi-fractal Brownian motion, including but not limited to methods based on absolute moments78,79, local regression of the log time-averaged mean square displacement against the log lag time80,81, detrended fluctuation analysis82, and the use of variational smoothing83,84.

The second quantity we apply the method of integrated quasi-differentiation to is the linear cross correlations. Although we only have one left time window and one right time window at any time t, we can feed more than one time series into each time window. When we do this for GOOG and MSFT, we again find surprises. Because they are both technology stocks traded on NASDAQ, we expect their daily closing prices and daily returns to be highly similar. Indeed, we see that this is the case in Fig. 12(a) and (b), where we show the daily closing prices and daily returns of GOOG and MSFT respectively. To quasi-differentiate the cross correlations between the daily returns of GOOG and MSFT, we define

while the quasi-derivative remains \(\Delta I(t_i) = I_R(t_i) - I_L(t_i)\). However, when we compute the heat map of \(\Delta I(t_i)\) for different window widths w, we see in Fig. 12(c) that is even more complex than the heat map we have in Fig. 8(a) for the daily returns of DJIA. This suggests that, as Fig. 8(a) has for \(\mu (t)\) shown in Fig. 9(a), that \(C_{\text {GOOG}, \text {MSFT}}(t)\) is not a constant, but a function with complex time dependence (as shown in Fig. 12(d)).

(a) The daily closing prices and (b) daily returns of GOOG and MSFT, between 2005 and 2023. (c) The heat map of the quasi-derivative of the cross correlations \(C_{\text {GOOG}, \text {MSFT}}(t)\) between GOOG and MSFT, over 2005 to 2023, obtained using window sizes \(20 \le w \le 250\). (d) The integrated quasi-derivative of \(C_{\text {GOOG}, \text {MSFT}}(t)\) for \(w = 150\) showing complex oscillations between 2005 and 2023. To test how well the method of integrated quasi-differentiation can recover a time-dependent cross correlation, (e) we sampled the artificial stochastic time series \(x_1(t)\) and \(x_2(t)\) with no cross correlations between them, and created an artificial stochastic time series \(x_3(t) = \rho (t) x_1(t) + \sqrt{1 - \rho ^2(t)} x_2(t)\), where \(\rho (t) = 0.4\cos (t/400)\). (f) The integrated quasi-derivative of \(\rho (t)\) (blue) is compared against the exact value of \(\rho (t)\) (red).

To show that \(C_{\text {GOOG}, \text {MSFT}}(t)\) in Fig. 12(d) is not an artefact created by the integrated quasi-derivative method, we tested the method on the cross correlations between artificial stochastic time series. First, we sample \(N = 5000\) time points each for \(x_1(t)\) and \(x_2(t)\) (shown in Fig. 12(e)) from the standard normal distribution with \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma ^2 = 1\). This means that the autocorrelations are zero in both \(x_1(t)\) and \(x_2(t)\), while the two time series have zero cross correlations. Next, if we create a third artificial stochastic time series \(x_3(t) = \rho x_1(t) + \sqrt{1 - \rho ^2} x_2(t)\), the cross correlation between \(x_3(t)\) and \(x_1(t)\) would be \(-1 \le \rho \le +1\). A constant (or time-averaged) cross correlation can be easily estimated using the formula

where \(\overline{x_1} = \frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^N x_{1,i}\), \(\overline{x_3} = \frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^N x_{3,i}\) are the means of the time series \(x_{1,i} = x_1(t_i)\) and \(x_{3,i} = x_3(t_i)\) respectively.

As far as we know, there are no methods to estimate a time-dependent cross correlation, for example

that we used to create \(x_3(t)\) as a time-varying admixture of \(x_1(t)\) and \(x_2(t)\). As shown in Fig. 12(e), there is no way for us to guess visually when \(x_3(t)\) is more correlated with \(x_1(t)\) or more correlated with \(x_2(t)\). Therefore, we compute the quasi-derivative of \(C_{1,3}(t)\) using a time window width \(w = 300\). This width is less than \(T = 400\), the period of \(\rho (t)\), ensuring that we can approximately recover the amplitude of \(\rho (t)\), as shown in Fig. 12(f). This point-wise estimation of cross correlations has the potential to open many doors to high-temporal-resolution analyses not previously possible in financial economics and econophysics.

In Supplementary Section S4, we performed rigorous statistical tests of the integrated quasi-derivative \(\rho _w(i,j)\), first against \(S = 1,000\) pairs of Gaussian time series \(x_i(t)\) and \(x_j(t)\) with constant cross correlation \(\rho = 0.4\), and then against \(S = 1,000\) pairs of \(x_i(t)\) and \(x_j(t)\) with cross correlation \(\rho (t) = 0.4\cos (t/400)\). In Supplementary Figure S12, we show how \(\langle \rho _w(i,j)\rangle\) accurately estimates \(\rho = 0.4\), and how the standard error \(\delta \rho _w(i,j)\) decreases with window size w as \(\delta \rho _w(i,j) \sim w^{-0.31}\). In y Figure S13, we show how \(\rho _w(i,j; t)\) accurately estimates the time-dependent \(\rho (i,j; t)\), and the larger systematic deviation of \(\rho _w(i,j; t)\) from \(\rho (i,j; t)\) for \(w = 300\) compared to \(w = 150\). Again, this gives us confidence that our results shown in Fig. 12 is a feature of the data, and not an artifact of the integrated quasi-differentiation method.

Data availability

Secondary data that we can openly share and Python scripts for generating and manipulating such data can be found at https://doi.org/10.21979/N9/4Y4GFI.

References

Ottino, J. M. Complex systems. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. J. 49, 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690490202 (2003).

Cumming, G. S. & Collier, J. Change and identity in complex systems. Ecol. Soc. 10, 29 (2005) https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267756.

Sayama, H. Introduction to the Modeling and Analysis of Complex Systems (Milne Open Textbooks, 2015).

Holovatch, Y., Kenna, R. & Thurner, S. Complex systems: physics beyond physics. Eur. J. Phys. 38, 023002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6404/aa5a87 (2017).

Thurner, S., Hanel, R. & Klimek, P. Introduction to the Theory of Complex Systems (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Scheffer, M. et al. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 461, 53–59 (2009).

Scheffer, M. et al. Anticipating critical transitions. Science 338, 344–348 (2012).

Himberg, J., Korpiaho, K., Mannila, H., Tikanmaki, J. & Toivonen, H. T. Time series segmentation for context recognition in mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, 203–210. IEEE (IEEE, 2001).

Wong, J. C., Lian, H. & Cheong, S. A. Detecting macroeconomic phases in the dow jones industrial average time series. Physica A 388, 4635–4645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2009.07.029 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Will the us economy recover in 2010? a minimal spanning tree study. Physica A 390, 2020–2050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2011.01.020 (2011).

Cheong, S. A. et al. The japanese economy in crises: a time series segmentation study. Economics 6, 2012–5. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2012-5 (2012).

Liu, S., Yamada, M., Collier, N. & Sugiyama, M. Change-point detection in time-series data by relative density-ratio estimation. Neural Networks 43, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2013.01.012 (2013).

Lovrić, M., Milanović, M., & Stamenković, M. Algoritmic methods for segmentation of time series: An overview. J. Contemp. Econ. Bus. Issues 1, 31–53, https://hdl.handle.net/10419/147468 (2014).

Aminikhanghahi, S. & Cook, D. J. A survey of methods for time series change point detection. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 51, 339–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10115-016-0987-z (2017).

Yamashita Rios de Sousa, A. M., Takayasu, H. & Takayasu, M. Segmentation of time series in up- and down-trends using the epsilon-tau procedure with application to usd/jpy foreign exchange market data. PLoS ONE 15, e0239494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239494 (2020).

Hamilton, J. D. A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57, 357–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912559 (1989).

Kim, C. J. Dynamic linear models with markov-switching. J. Econom. 60, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)90036-1 (1994).

Kehagias, A. A hidden markov model segmentation procedure for hydrological and environmental time series. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 18, 117–130 (2004).

Kehagias, A. & Fortin, V. Time series segmentation with shifting means hidden markov models. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 13, 339–352. https://doi.org/10.5194/npg-13-339-2006 (2006).

Hamilton, J. D. Regime Switching Models, 202–209 (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010).

Yamada, M., Mossa, S., Stanley, H. E. & Sciortino, F. Interplay between time-temperature transformation and the liquid-liquid phase transition in water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 195701. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.195701 (2002).

Fierro, B., Bachmann, F. & Vogel, E. E. Phase transition in 2d and 3d ising model by time-series analysis. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 384, 215–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2006.05.265 (2006).

Kiyono, K., Struzik, Z. R. & Yamamoto, Y. Criticality and phase transition in stock-price fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 068701. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.068701 (2006).

Wanliss, J. A. & Dobias, P. Space storm as a phase transition. J. Atmospheric Solar-Terrestrial Phys. 69, 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jastp.2007.01.001 (2007).

Harré, M. & Bossomaier, T. Phase-transition–like behaviour of information measures in financial markets. Europhys. Lett. 87, 18009. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/87/18009 (2009).

Raddant, M. & Wagner, F. Phase transition in the S&P stock market. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 11, 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-015-0160-x (2016).

Yen, P.T.-W., Xia, K. & Cheong, S. A. Laplacian spectra of persistent structures in Taiwan, Singapore, and US stock markets. Entropy 25, 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/e25060846 (2023).

Kang, Z. T., Yen, P.T.-W. & Cheong, S. A. Indicator from the graph laplacian of stock market time series cross-sections can precisely determine the durations of market crashes. PLoS One 20, e0327391 (2025).

Hyndman, R. J. & Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice (OTexts, 2018).

Hunter, J. S. The exponentially weighted moving average. J. Quality Technology 18, 203–210 (1986).

Basse, A. Gaussian moving averages and semimartingales. Electron. Commun. Probab. [electronic only] 13, 1140–1165 (2008).

Cleveland, W. S. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Statistical Association 74, 829–836 (1979).

Cleveland, W. S. Lowess: A program for smoothing scatterplots by robust locally weighted regression. The Am. Stat. 35, 54 (1981).

Cleveland, W. S. & Devlin, S. J. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Statistical Association 83, 596–610 (1988).

Hieftje, G., Holder, B., Maddux, A. & Lim, R. Digital smoothing of electroanalytical data based on the Fourier transformation. Anal. Chem. 45, 277–284 (1973).

Kosarev, E. & Pantos, E. Optimal smoothing of’noisy’data by fast fourier transform. J. Phys. E: Sci. Instruments 16, 537 (1983).

Barclay, V., Bonner, R. & Hamilton, I. Application of wavelet transforms to experimental spectra: smoothing, denoising, and data set compression. Anal. Chem. 69, 78–90 (1997).

Ismail, A. R. & Asfour, S. S. Discrete wavelet transform: a tool in smoothing kinematic data. J. Biomechanics 32, 317–321 (1999).

Lillo, F. & Mantegna, R. N. Power-law relaxation in a complex system: Omori law after a financial market crash. Phys. Rev. E 68, 016119. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.016119 (2003).

Lillo, F. & Mantegna, R. N. Dynamics of a financial market index after a crash. Physica A 338, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2004.02.034 (2004).

Broemeling, L. D. & Tsurumi, H. Econometrics and Structural Change (Marcel Dekker, 1987).

Piger, J. Econometrics: Models of Regime Changes, 2744–2757 (Springer, 2009).

Chui, C. K. An Introduction to Wavelets (Academic Press, 1992).

Alsberg, B. K., Woodward, A. M. & Kell, D. B. An introduction to wavelet transforms for chemometricians: A time-frequency approach. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 37, 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7439(97)00029-4 (1997).

Walnut, D. F. An Introduction to Wavelet Analysis (Birkhäuser, 2013).

Qian, K. Windowed fourier transform for fringe pattern analysis. Appl. Opt. 43, 2695–2702. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.43.002695 (2004).

Rapuano, S. & Harris, F. J. An introduction to FFT and time domain windows. IEEE Instrumentation Meas. Mag. 10, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIM.2007.4428580 (2007).

Huang, L., Qian, K., Pan, B. & Asundi, A. K. Comparison of fourier transform, windowed Fourier transform, and wavelet transform methods for phase extraction from a single fringe pattern in fringe projection profilometry. Opt. Lasers Eng. 48, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2009.04.003 (2010).

Yen, P.T.-W. & Cheong, S. A. Using topological data analysis (TDA) and persistent homology to analyze the stock markets in Singapore and Taiwan. Front. Phys. 9, 572216. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.572216 (2021).

Yen, P.T.-W., Xia, K. & Cheong, S. A. Understanding changes in the topology and geometry of financial market correlations during a market crash. Entropy 23, 23091211. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23091211 (2021).

Gultekin, M. N. & Gultekin, N. B. Stock market seasonality: International evidence. J. Financial Econ. 12, 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(83)90044-2 (1983).

De Bondt, W. F. & Thaler, R. H. Further evidence on investor overreaction and stock market seasonality. The J. Finance 42, 557–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1987.tb04569.x (1987).

Hansen, P. R., Lunde, A. & Nason, J. M. Testing the significance of calendar effects. Working Paper 2005-02, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (2005). https://ssrn.com/abstract=388601.

Sutcliffe, J., Hurst, S., Awadallah, A. G., Brown, E. & Hamed, K. Harold Edwin Hurst: the Nile and Egypt, past and future. Hydrol. Sci. J. 61, 1557–1570. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2015.1019508 (2016).

O’Connell, P. et al. The scientific legacy of Harold Edwin Hurst (1880–1978). Hydrol. Sci. J. 61, 1571–1590. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2015.1125998 (2016).

Peng, C. K. et al. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys. Rev. E 49, 1685. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.49.1685 (1994).

Higuchi, T. Approach to an irregular time series on the basis of the fractal theory. Physica D 31, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(88)90081-4 (1988).

Geweke, J. & Porter-Hudak, S. The estimation and application of long memory time series models. J. Time Ser. Analysis 4, 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1983.tb00371.x (1983).

Taqqu, M. S., Teverovsky, V. & Willinger, W. Estimators for long-range dependence: an empirical study. Fractals 3, 785–798. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218348X95000692 (1995).

Beran, J. Statistics for Long-Memory Processes (Routledge, 1994).

Simonsen, I., Hansen, A. & Nes, O. M. Determination of the Hurst exponent by use of wavelet transforms. Phys. Rev. E 58, 2779. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.58.2779 (1998).

Gómez-Águila, A., Trinidad-Segovia, J. E. & Sánchez-Granero, M. A. Improvement in Hurst exponent estimation and its application to financial markets. Financial Innov. 8, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-022-00394-x (2022).

Barabási, A. L. & Vicsek, T. Multifractality of self-affine fractals. Phys. Rev. A 44, 2730. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.44.2730 (1991).

Di Matteo, T., Aste, T. & Dacorogna, M. Scaling behaviors in differently developed markets. Phys. A 324, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(02)01996-9 (2003).

Lotfalinezhad, H. & Maleki, A. TTA, a new approach to estimate Hurst exponent with less estimation error and computational time. Physica A 553, 124093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2019.124093 (2020).

Gómez-Águila, A. & Sánchez-Granero, M. A. A theoretical framework for the TTA algorithm. Physica A 582, 126288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2021.126288 (2021).

Trinidad Segovia, J. E., Fernández-Martínez, M. & Sánchez-Granero, M. A. A note on geometric method-based procedures to calculate the Hurst exponent. Physica A 391, 2209–2214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2011.11.044 (2012).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Sánchez-Granero, M. A., Trinidad Segovia, J. E. & Román-Sánchez, I. M. An accurate algorithm to calculate the Hurst exponent of self-similar processes. Phys. Lett. A 378, 2355–2362, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2014.06.018 (2014).

Carbone, A., Castelli, G. & Stanley, H. E. Time-dependent Hurst exponent in financial time series. Physica A 344, 267–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2004.06.130 (2004).

Matos, J. A., Gama, S. M., Ruskin, H. J. & Duarte, J. A. An econophysics approach to the portuguese stock index–PSI-20. Physica A 342, 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2004.05.066 (2004).

Eom, C., Choi, S., Oh, G. & Jung, W. S. Hurst exponent and prediction based on weak-form efficient market hypothesis of stock markets. Physica A 387, 4630–4636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2008.03.035 (2008).

Domino, K. The use of the Hurst exponent to predict changes in trends on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Physica A 390, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2010.04.015 (2011).

Rege, S. & Martín, S. G. Portuguese stock market: A long-memory process? Business: Theory Pract. 12, 75–84 (2011).

Morales, R., Di Matteo, T., Gramatica, R. & Aste, T. Dynamical generalized Hurst exponent as a tool to monitor unstable periods in financial time series. Physica A 391, 3180–3189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2012.01.004 (2012).

Gomes, L. M., Soares, V. J., Gama, S. M. & Matos, J. A. Long-term memory in Euronext stock indexes returns: An econophysics approach. Bus. Econ. Horizons 14, 862–881 (2018).

Vogl, M. Hurst exponent dynamics of S&P 500 returns: Implications for market efficiency, long memory, multifractality and financial crises predictability by application of a nonlinear dynamics analysis framework. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 166, 112884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112884 (2023).

Naaman, M. On the tight constant in the multivariate Dvoretzky-Kiefer-Wolfowitz Inequality. Stat. & Probab. Lett. 173, 109088 (2021).

Bianchi, S. Pathwise identification of the memory function of multifractional Brownian motion with application to finance. Int. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance 8, 255–281 (2005).

Bianchi, S., Pantanella, A. & Pianese, A. Modeling stock prices by multifractional Brownian motion: an improved estimation of the pointwise regularity. Quant. finance 13, 1317–1330 (2013).

Bertrand, P. R., Hamdouni, A. & Khadhraoui, S. Modelling NASDAQ series by sparse multifractional Brownian motion. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 14, 107–124 (2012).

Balcerek, M. et al. Multifractional Brownian motion with telegraphic, stochastically varying exponent. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 197101 (2025).

Setty, V. A. & Sharma, A. S. Characterizing detrended fluctuation analysis of multifractional Brownian motion. Physica A 419, 698–706 (2015).

Garcin, M. Estimation of time-dependent Hurst exponents with variational smoothing and application to forecasting foreign exchange rates. Physica A 483, 462–479 (2017).

Di Persio, L. & Turatta, G. Multi-fractional Brownian motion: Estimating the Hurst exponent via variational smoothing with applications in finance. Symmetry 14, 1657 (2022).

Funding

This work is not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.T.K., P.T.-W.Y., and S.A.C. came up with the original ideas for the method. S.A.C. developed the method, performed the experiments, and analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheong, S.A., Kang, Z.T. & Yen, P.TW. Quasi-differentiation and its applications to noisy time series data from complex systems. Sci Rep 15, 39080 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26106-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26106-w