Abstract

This study explored the relationship between condylar position and oropharyngeal airway dimensions across various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans from 330 individuals aged 12 to 18 were analyzed. The individuals were categorized into sagittal skeletal Classes I, II, and III and divided into groups based on vertical skeletal patterns. Each vertical group was further subdivided according to condylar position as anterior, centric, or posterior. Airway dimensions—specifically oropharyngeal volume (OPV), area (OPA), and minimum cross-sectional area (MCA)—along with condylar position, were measured. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for intergroup comparisons, followed by Pairwise Comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment. Spearman correlation was used to assess the relationship between airway parameters, age, craniofacial measurements, and condylar concentricity (CC). Multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis was applied to identify predictors of oropharyngeal airway dimensions based on age, anteroposterior and vertical skeletal patterns (ANB, FMA), and condylar concentricity. The comparison of airway dimensions within each sagittal class revealed that individuals with anterior condylar position and hyperdivergent patterns had the narrowest airway dimensions (OPV, OPA, and MCA) in Class II and III. However, when differences were evaluated between sagittal skeletal classes within each vertical pattern, Class II subjects with anterior condylar position exhibited the smallest airway dimensions. These findings emphasize the significant influence of skeletal pattern and condylar position on oropharyngeal airway dimensions. Class II individuals with anterior condylar position consistently had the smallest airway dimensions. In contrast, Class III individuals with posterior condylar position had the largest, highlighting the combined role of sagittal and vertical craniofacial patterns and condylar positioning in shaping airway morphology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The connection between upper airway dimensions and craniofacial morphology has become a focal point in recent years due to its link to sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and its impact on facial development. Early identification of SDB or its potential risk factors is essential for fostering normal craniofacial growth. Reduced pharyngeal dimensions early in life may increase the risk of developing sleep-disordered breathing, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), as factors such as aging, obesity, or genetic predisposition further compromise oropharyngeal airway patency1. The upper airway comprises the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx, with the oropharynx being the narrowest region, most susceptible to changes after orthodontic treatment2. Research has indicated that the airway volume is associated not only with the positioning of the tongue, soft palate, and pharyngeal fat pads, but also with the relative positions of the maxilla and mandible3.

A systematic review investigating the relationship between skeletal structure and upper airway volume, assessed through 3D imaging, found that patients with Class II malocclusion had smaller upper airway volumes compared to Class I patients, while Class III patients generally exhibited larger airway volumes. Moreover, individuals with hyperdivergent profiles were found to have reduced oropharyngeal volumes compared to normodivergent patients4.

Hong et al.5 reported that individuals with skeletal Class III patterns tended to have larger oropharyngeal airway dimensions than those with Class I or II skeletal patterns. However, the difference was not statistically significant. On the other hand, several studies have found that individuals with a Class III skeletal pattern have significantly larger oropharyngeal airway volumes than those with Class I and II patterns6. Other studies have indicated weak or minimal associations between craniofacial characteristics and oropharyngeal airway measurements7,8.

The findings of Xu et al.9 demonstrate a significant association between condylar position and pharyngeal airway space in skeletal Class II individuals. Their CBCT-based analysis revealed that an anterior condylar position correlates with reduced airway volume and cross-sectional area. A study by Yuen et al.10 demonstrated increased pharyngeal airway space following condyle replacement and mandibular advancement surgery, further supporting the potential link between airway dimensions and condylar positioning.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has emerged as a valuable tool in orthodontic assessment, offering high-resolution 2D and 3D imaging of both hard and soft tissues. It is beneficial for evaluating the pharyngeal airway due to its lower radiation exposure and faster image acquisition compared to conventional CT scans11. The use of CBCT and advancements in medical technology have significantly enhanced the evaluation of the pharyngeal airway in orthodontics12. To our knowledge, despite this progress, no study has yet explored the relationship between airway dimensions and condylar positions across the full spectrum of anteroposterior skeletal malocclusions (Class I, II, and III). This study aims to explore the relationship between condylar position and pharyngeal airway dimensions in individuals with different sagittal and vertical skeletal classifications, with the goal of better understanding these relationships.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was designed as a retrospective, cross-sectional study. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Stomatological Hospital at Xi’an Jiaotong University, under the approval number: 2024-XJKQIEC-KY-QT-0052-001.

Sample size calculation

The required sample size was determined using the G*Power software (G*Power version 3.1.9.4, Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany)13. Based on a previously published study by A. Chianchitlert14, an effect size of 0.25 was applied. The calculations were conducted using a Type I error rate (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power (1-β) of 0.95. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 84 individuals per group (a total of 252 individuals) would be needed. To enhance the study’s statistical power, the final sample size was increased to 330 individuals.

Study population

The study randomly selected CBCT records for 330 Chinese individuals who met the inclusion criteria (132 males (40%) and 198 females (60%)), aged between 12 and 18 years with an average (14.22 ± 1.78 years), who visited the Xi’an Jiaotong University clinic from January 2020 to November 2024. CBCT scans were not obtained specifically for research purposes. All patients provided informed consent, permitting the use of their clinical records for research purposes.

Inclusion criteria

Individuals were divided into three sagittal skeletal classes: Class I (1° ≤ ANB° ≤ 5°), Class II (ANB° >5°), and Class III (ANB°<1°)15,16,17. According to their vertical skeletal patterns, three groups of individuals were created within each class: normodivergent growers (25.3°< FMA°<33°)18,19, hypodivergent (FMA° < 25.3°), and hyperdivergent growers (FMA° > 33°). Every individual had to be between the ages of 12 and 18 and have a normal body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 24 kg/m220.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion was done for individuals with a positive history of craniofacial syndromes or anomalies, systemic diseases affecting craniofacial growth, prior orthodontic treatment, OSA, habitual or obstructive mouth breathing, adenoid hypertrophy, or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders. Individuals with mouth breathing or adenoid hypertrophy were excluded from the study, as mouth breathing can alter the position of the tongue and lips, potentially affecting airway measurements21,22,23. Additionally, adenoid hypertrophy can lead to nasal obstruction, which may affect breathing patterns and the dimensions of the pharyngeal airway24.

Sample grouping

Individuals were categorized based on sagittal skeletal pattern, vertical growth pattern, and condylar position (Fig. 1). Sagittal skeletal relationships were classified as Class I, II, or III based on ANB angle measurements. Vertical facial patterns were defined as normodivergent (N), hyperdivergent (Hr), or hypodivergent (Hp) according to the FMA angle. Condylar position was assessed using Pullinger’s method25 and categorized as anterior (A), centric (C), or posterior (P). Composite group labels were created by combining these classifications. For example, “Class II-Hr-A” denotes an individual with a Class II skeletal pattern, a hyperdivergent vertical growth pattern, and an anteriorly positioned condyle. This system facilitated subgroup analysis across different skeletal and positional profiles.

The diagram illustrates the classification of individuals into Class I, II, and III skeletal patterns, with additional subdivisions based on vertical growth patterns (normodivergent, hyperdivergent, and hypodivergent) and condylar positions (anterior, centric, and posterior). The figure was produced using Dolphin Imaging software (Version 11.9, Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, CA, USA; https://www.dolphinimaging.com/).

CBCT acquisition protocol

The i-Cat system (Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA, USA) performed CBCT scans. It was configured with 120 kV, 5 mA, a 14 × 17 cm field of view, a 0.4 mm voxel size, and an 8.9-second scan time. The patients were told to maintain a relaxed lip and tongue position while sitting up straight and maintaining a natural head position stabilized by forehead support and ear rods while keeping teeth in maximal intercuspation—the Frankfort horizontal plane (FHP) runs in a parallel direction to the floor, with FHP alignment based on skin points, specifically the Porion and Nasion landmarks, for accuracy. Patients were instructed to breathe normally through their noses during image acquisition, without swallowing, moving their heads, or tongues. DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format was used to store all CBCT data.

CBCT image orientation and measurement procedures

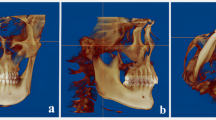

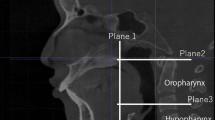

DICOM files were imported using Dolphin Imaging software (version 11.9; Dolphin Imaging & Management Solutions®, Chatsworth, CA, USA). All measures were taken by a single investigator who was blinded. The image orientation process involved aligning the coronal plane perpendicular to the axial plane, passing through the Porion point, the midsagittal plane with the patient’s midline (a vertical line via Nasion), and the axial plane with the FHP (Fig. 2). Airway segmentation sensitivity was set to the 50 − 55 range to obtain an accurate representation of the airway26. The 50–55 range was found to accurately represent the airway while minimizing overflow from surrounding tissues. After testing different values, this range proved most effective for segmentation and was consistently applied across all scans for reliability.

Evaluation of condylar position

One blinded investigator (D.M.) evaluated the condylar position using a sagittal CBCT slice that showed the glenoid fossa’s center. Condylar position was categorized using the Pullinger et al. 25 technique, which applied the following formula: \(\:CD\:=\:(A\:-\:P)\:/\:(A\:+\:P)\:\times\:\:100\%\)

A represents the anterior joint space (AS), P represents the posterior joint space (PS), and CD represents the condylar displacement percentage. The condylar location was categorized as follows using the computed CD value:

-

Anterior (CD ≤ − 12%).

-

Centric (− 12% < CD < + 12%).

-

Posterior (CD ≥ + 12%).

The axial view showing the widest mediolateral diameter of the condylar process was selected as the reference for secondary reconstruction. From this axial view, a line parallel to the long axis of the condylar process was drawn, and lateral slices were reconstructed at 0.5 mm intervals with 0.5 mm thickness. From the superior fossa (SF) – the highest point on the roof of the glenoid fossa-, lines were drawn tangent to the most prominent anterior and posterior surfaces of the condyle. The narrowest posterior (PS) and anterior (AS) joint spaces were then accurately measured on the central sagittal section (Fig. 3A, B)27.

(A) The glenoid fossa as seen in the coronal view, with its central part determined based on the vertical reference line. (B) The sagittal slice of the CBCT image of the mandibular condyle in the glenoid fossa. From the superior fossa (SF), lines were drawn tangent to the most prominent anterior and posterior surfaces of the condyle. The distances from these tangent points to the glenoid fossa were measured and recorded as the anterior joint space (AS) and posterior joint space (PS), respectively. The figure was produced using Dolphin Imaging software (Version 11.9, Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, CA, USA; https://www.dolphinimaging.com/).

Pharyngeal measurements

The area of interest in the airway was located using the Dolphin 3D Imaging software’s airway analysis tool. The oropharyngeal airway space was defined by drawing one line parallel to the FHP through the posterior nasal spine and another parallel to the FHP at the tip of the epiglottis. These lines were used to demarcate the boundaries of the oropharyngeal airway space18. The airway volume, airway area, and minimum cross-sectional area were measured, and the updated volume was produced28 (Fig. 4).

(A) Boundary of the oropharyngeal volume (OPV), (B) Oropharyngeal area (OPA) and minimum cross-sectional area (MCA), (C) 3D volumetric reconstruction demonstrating OPV and MCA. The figure was produced using Dolphin Imaging software (Version 11.9, Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, CA, USA; https://www.dolphinimaging.com/).

The following airway measurements were taken:

-

Oropharyngeal Volume (OPV).

-

Oropharyngeal Area (OPA).

-

Minimum Cross-sectional Area (MCA).

These measurements are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate intra-investigator reliability, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated based on measurements from 30 randomly selected individuals, with measurements repeated two weeks after the initial assessment. The ICC was computed using a two-way mixed-effects model with average measures and absolute agreement. Measurement error was assessed using the formula proposed by Dahlberg29. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1), with a significance level set at P < 0.05. The normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which indicated that the data were not normally distributed. Consequently, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed for intergroup comparisons. When significant variables were identified, pairwise comparisons were conducted. The Pearson χ2 test was used in descriptive statistics to analyze sex distributions across the groups, assessing the homogeneity of these distributions.

The Mann-Whitney U-test was also performed to compare the joint space between the right and left condyles, assessing whether their positions within the mandibular fossa were similar on both sides. The Spearman correlation coefficient was computed to examine the relationships between airway parameters, condylar concentricity, and craniofacial parameters. Given the non-normal distributions of the dependent variables, multiple linear regression analysis was performed following logarithmic transformation to identify predictive factors for airway dimensions.

Results

The ICC demonstrated strong intra-investigator consistency, with values ranging from 0.90 to 0.97 for volumetric measurements and from 0.93 to 0.99 for linear measurements. Measurement errors, calculated using Dahlberg’s formula, ranged from 0.81 to 1.60 mm for linear measurements and from 165 to 323 mm3 for volumetric measurements. Method-related errors were found to be negligible, as indicated by the results of repeated testing. Condylar concentricity between the right and left condylar measurements was not statistically significant (P = 0.461), indicating that the position of condyles within the mandibular fossa was similar on both sides.

The baseline demographics are shown in Table 2 and include sex, age, right and left condylar concentricity, and the different angular measurements for each of the three skeletal classes (Class I, II, and III).

Comparing across sagittal patterns

For the Class I group, we analyzed the oropharyngeal airway space using an Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test, including OPV, OPA, and MCA, to determine whether their distributions differ across skeletal patterns considering condylar position. We found that OPV and MCA showed no statistical difference (p = 0.258 and p = 0.523, respectively) across vertical skeletal patterns, whereas OPA initially showed a substantial difference (p = 0.041); however, after the Bonferroni correction, all differences were no longer statistically significant.

In the Class II group, OPV, OPA, and MCA showed significant differences (see Table 3). These parameters were lowest in the Class II-Hr-A group (skeletal Class II hyperdivergent individuals with anteriorly positioned condyles), with P values of < 0.001 for OPV and OPA and < 0.01 for MCA. Among Class II hyperdivergent individuals, those with anteriorly positioned condyles had lower OPV and OPA than those with centric and posterior condylar positions (P < 0.05; Table 4).

In the Class III group, OPV, OPA, and MCA also showed significant differences (see Table 3). These values were lowest in the Class III-Hr-A group (skeletal Class III hyperdivergent individuals with anteriorly positioned condyles), with P values of < 0.001 for OPV and MCA and < 0.05 for OPA (see Table 4).

Comparing across vertical patterns

Only the OPV differed significantly among normodivergent individuals across Class I, II, and III (see Table 5). The Class II-N-A group (Class II normodivergent individuals with anteriorly positioned condyles) showed a smaller OPV (P < 0.05; see Table 6).

Among hyperdivergent individuals comparing Class I, II, and III, notable differences were observed in OPV, OPA, and MCA (see Table 5). The lowest values for all three parameters were found in the Class II group with anteriorly positioned condyles, with P values of < 0.001 for OPV, < 0.01 for OPA, and < 0.01 for MCA (see Table 6).

Among hypodivergent individuals across Class I, II, and III, OPV, OPA, and MCA showed significant differences (see Table 5). All three parameters were lowest in the Class II group with anteriorly positioned condyles, with P values of < 0.001 for OPV and MCA and < 0.01 for OPA (see Table 6).

Table 7 presents the results of a bivariate correlation analysis between airway space, condylar concentricity, and craniofacial parameters. The findings show that age, SNB, and condylar concentricity are positively associated with oropharyngeal airway measures (OPV, OPA, MCA), whereas FMA and ANB are negatively correlated. Sex and SNA do not correlate with the airway parameters.

In Table 8; Fig. 5, a regression model was developed to predict the oropharyngeal airway dimensions using age, ANB, FMA, and condylar concentricity (CC) as predictors. The model was statistically significant and effective for OPV (adjusted R2 = 0.261), followed by OPA (adjusted R2 = 0.201), while it was weak for MCA (adjusted R2 = 0.167). The linear regression equations were as follows: OPV, \(Y = 3.908+0.021(X1) -0.007(X2)\) \(-0.004(X3) +0.001(X4)\), \(OPA,Y=2.662+0.012(X1) -0.005(X2)\) \(-0.003(X3) +0.001(X4)\), \(MCA,Y=2.148+0.020(X1) -0.012(X2)\)\(-0.006(X3) +0.001(X4).\) where Y indicates the log of OPV, OPA, and MCA; X1 indicates age; X2 indicates ANB; X3 indicates FMA; and X4 indicates Condylar Concentricity (CC).

Discussion

A previous study reported that in adults with skeletal Class II malocclusion, oropharyngeal airway dimensions varied significantly depending on whether the condyles were positioned anteriorly, centrally, or posteriorly9. Notably, that investigation was the first to explore the relationship between condylar position and pharyngeal airway dimensions. However, it was limited to normodivergent individuals with skeletal Class II malocclusion, leaving a gap in our understanding of how condylar position might influence airway space across various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns.

This study explored the oropharyngeal airway space across different sagittal skeletal classes and vertical growth patterns, with a particular focus on its relationship with condylar position. The findings revealed that airway dimensions (OPV, OPA, and MCA) were closely associated with condylar position, with the narrowest airway measurements consistently observed in Class II hyperdivergent individuals with anteriorly positioned condyles.

Two-dimensional radiographic imaging is often unreliable for evaluating condylar position because it is affected by magnification, distortion, and overlapping nearby anatomical structures, making accurate assessment difficult30,31. CBCT has been used in several earlier investigations to assess the condyle positions32,33,34. However, Pullinger’s method25, using a 2D sagittal slice for condylar evaluation, has the limitation of not capturing the full 3D positioning, including medial/lateral position and rotation. While this is a common drawback of 2D techniques, it remains widely used in clinical settings. Pullinger’s criteria (-12%/12%) for condylar position on CBCT is an established convention based on prior studies9,27.

Xu et al.9, although not classifying their participants based on antero-posterior skeletal classes or vertical growth patterns, reported that, in contrast to the central and posterior condylar groups, the anterior condylar group’s pharyngeal airway volumes and areas were noticeably smaller, with the posterior group demonstrating the largest airway dimensions. A similar trend was observed in our study, particularly within the Class II hyperdivergent group (anterior, centric, and posterior). Specifically, we observed that the OPV in the anterior group was the smallest compared to the centric and posterior groups. Additionally, the OPA in the anterior group was considerably smaller compared to the centric group. However, this pattern was not evident in the Class II normodivergent, in contrast to the findings of the previous study. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in participant age ranges, as Xu et al. included individuals aged 18 years and older. Another potential factor could be the variation in sample sizes across subgroups between the two studies. Furthermore, Xu et al. didn’t consider the anteroposterior and vertical classification.

Altheer et al.4 recently conducted a systematic review demonstrating that hyperdivergent individuals generally exhibit smaller oropharyngeal volumes than normodivergent individuals. Similarly, Al-Somairi et al.12 reported that hyperdivergent patients had significantly reduced oropharyngeal sagittal width, volume, surface area, and minimum constricted area, with skeletal Class III individuals showing the greatest sagittal width. Our study builds on these findings by incorporating condylar position as an additional variable. Among Class II individuals, we found that OPV, OPA, and MCA were all significantly smaller in the Class II-Hr-A group (skeletal Class II-hyperdivergent with anteriorly positioned condyles), and these parameters notably increased in the Class II-N-P (skeletal Class II-Normo-divergent with posteriorly positioned condyles) and Class II-Hp-P groups. A similar pattern was observed in Class III, where all three airway parameters were lowest in the Class III-Hr-A group and showed a substantial increase in the Class III-Hp-P group (skeletal Class III-hypodivergent with posteriorly positioned condyles).

Previous studies have highlighted the influence of skeletal pattern on upper airway dimensions8,14,35,36. Guo et al.37 reported that hyperdivergent individuals tend to have smaller oropharyngeal volumes than their normodivergent and hypodivergent counterparts, and that skeletal Class II patients generally exhibit narrower upper airways. Similarly, Nath et al.38 found a significant correlation between pharyngeal airway volume and the anteroposterior position of the mandible, with skeletal Class II individuals consistently demonstrating smaller airway volumes than those in Class I and III. Our findings align with these observations and further build upon them by including condylar position in the analysis. Among normodivergent individuals in our study, the OPV was notably smaller in the Class II with anteriorly positioned condyles group compared to the Class III with posteriorly positioned condyles group. In both hyperdivergent and hypodivergent groups, OPV, OPA, and MCA were substantially reduced in the Class II with anteriorly positioned condyles group compared to Class III. These results suggest that airway dimensions are influenced not only by skeletal classification and vertical pattern but also by the position of the mandibular condyle, with anteriorly positioned condyles associated with smaller airway volumes and posteriorly positioned condyles tending to correlate with larger airway dimensions.

Chan et al.39 found that individuals with skeletal Class II malocclusion have a more posterior tongue base compared to Class III, often linked to a retrusive or short mandible. This can push the tongue and soft palate back, reducing oropharyngeal volume. Our study supports this, showing smaller OPV, OPA, and MCA in Class II individuals, especially those with hyperdivergent patterns and anteriorly positioned condyles (Class II-Hr-A). This suggests that condylar position, along with skeletal patterns, compounds the effect on upper airway morphology by influencing mandibular and tongue posture.

Paknahad et al.40 found that condyles were positioned more anteriorly in individuals with skeletal Class II malocclusion compared to Class I and III. They suggested this might reflect an adaptive response of the masticatory system or limited condylar cartilage adaptability. However, this could also be linked to reduced airway volume in Class II patients, where mandibular advancement may cause anterior condylar displacement as a compensatory mechanism for upper airway narrowing9. This highlights the importance of considering condylar position in relation to airway volume, particularly in Class II malocclusion cases.

In individuals with OSA, the hyoid bone is typically positioned inferiorly and posteriorly41. Mandibular advancement shifts the hyoid superiorly and anteriorly, expanding the hypopharyngeal airway42. In Class III malocclusion, orthodontic treatment with surgery often leads to mandibular setback, causing the hyoid and tongue to shift backward, reducing the airway space43. Oral appliances reposition the mandible and tongue forward, increasing airway size44. Factors such as adenoid and tonsil hypertrophy, allergies, and infections contribute to obstruction. The lack of lip seal and low tongue position in mouth breathers disrupts airway flow and may increase lymphatic tissue in the pharynx, affecting its dimensions21.

Xu et al. 45 investigated the accuracy of dynamic condylar positions by combining mandibular movement data with CBCT images. They reported that while static CBCT scans provide reliable 3D images of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), they do not capture the dynamic nature of jaw movements, which significantly affects condylar position. While our study relied on static CBCT imaging in maximal intercuspation, similar limitations may apply, as dynamic movements were not considered in our analysis.

This study found no statistically significant difference in joint spaces between the right and left sides, consistent with findings reported in most previous research46,47,48.

This study suggests that airway dimension is influenced by both skeletal class and condylar position, particularly in hyperdivergent and Class II cases. Since reduced oropharyngeal volume is associated with conditions like OSA, our results emphasize the value of assessing condylar position to help identify at-risk individuals and guide targeted treatments for better orthodontic and respiratory outcomes.

Despite the study’s contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective design restricts causal conclusions regarding the relationship between condylar position, craniofacial morphology, and airway dimensions. We recognize the importance of considering skeletal maturation, such as the Cervical Vertebral Maturation (CVM) stage, as our sample consisted of growing individuals. However, including this factor would require a larger sample size, warranting further investigation of its confounding effects in future research. Additionally, since this study was conducted at a single institution, the findings may not be broadly generalizable. Assessing condylar position in a static “maximal intercuspation” state might not fully capture dynamic jaw movements. Furthermore, smaller sample sizes in some subgroups could have decreased statistical power, and larger, more balanced subgroups in future studies could improve the robustness of the results. Finally, although mouth breathing and adenoid hypertrophy were excluded, uncontrolled variables such as tongue volume and posture, hyoid bone position, and maxillomandibular length may have influenced the outcomes. Future studies with larger, more diverse samples and prospective designs should consider these factors for a more comprehensive understanding.

Conclusion

-

This study highlights a significant relationship between condylar position and oropharyngeal airway dimensions, especially in sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns.

-

The results indicate that anteriorly positioned condyles are associated with smaller airway volumes, while posteriorly positioned condyles tend to correlate with larger airway dimensions.

-

These findings highlight the importance of considering condylar position when evaluating airway morphology in orthodontic treatment planning, as it may provide further insights into airway management, especially in patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion and varying vertical growth patterns.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CBCT:

-

Cone beam computed tomography

- OPV:

-

Oropharyngeal volume

- OPA:

-

Oropharyngeal area

- MCA:

-

Minimum cross-sectional area

- CC:

-

Condylar concentricity

- SDB:

-

Sleep-disordered breathing

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- N:

-

Normodivergent

- Hr:

-

Hyperdivergent

- Hp:

-

Hypodivergent

- AS:

-

Anterior joint space

- PS:

-

Posterior joint space

- CD:

-

Condylar displacement percentage

References

Anandarajah, S., Dudhia, R., Sandham, A. & Sonnesen, L. Risk factors for small pharyngeal airway dimensions in preorthodontic children: A three-dimensional study. Angle Orthod. 87, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.2319/012616-71.1 (2017).

Niu, X., Di Carlo, G., Cornelis, M. A. & Cattaneo, P. M. Three-dimensional analyses of short- and long-term effects of rapid maxillary expansion on nasal cavity and upper airway: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 23, 250–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12378 (2020).

Zhou, Z., Sun, L., Zhang, F. & Xu, Y. Three-dimensional evaluation of alveolar bone and pharyngeal airway dimensions after mandibular dentition distalization in patients with class III malocclusion: a retrospective study. Head Face Med. 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-023-00382-1 (2023).

Altheer, C., Papageorgiou, S. N., Antonarakis, G. S. & Papadopoulou, A. K. Do patients with different craniofacial patterns have differences in upper airway volume? A systematic review with network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 46 https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjae010 (2024).

Hong, J. S., Oh, K. M., Kim, B. R., Kim, Y. J. & Park, Y. H. Three-dimensional analysis of pharyngeal airway volume in adults with anterior position of the mandible. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 140, e161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.04.020 (2011).

Aldhorae, K. et al. Impact of maxillomandibular sagittal variations on upper airway dimensions: A retrospective Cross-sectional CBCT evaluation. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 25, 955–962. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3762 (2024).

Grauer, D., Cevidanes, L. S., Styner, M. A., Ackerman, J. L. & Proffit, W. R. Pharyngeal airway volume and shape from cone-beam computed tomography: relationship to facial morphology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 136, 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.01.020 (2009).

El, H. & Palomo, J. M. An airway study of different maxillary and mandibular sagittal positions. Eur. J. Orthod. 35, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjr114 (2013).

Xu, J., Sun, R., Wang, L. & Hu, X. Cone-beam evaluation of pharyngeal airway space in adult skeletal class II patients with different condylar positions. Angle Orthod. 89, 312–316. https://doi.org/10.2319/040518-253.1 (2019).

Yuen, H., Rossouw, P. E., Wolford, L. M. & Wang, H. Pharyngeal airway space changes after condylar replacement and mandibular advancement surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 76, 1165–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.12.022 (2018).

Golshah, A., Jalilian, T. H. & Nikkerdar, N. Pharyngeal airway dimensions in Iranian female young adults with different skeletal patterns using cone-beam computed tomography. J. Orthod. Sci. 12, 4. https://doi.org/10.4103/jos.jos_161_21 (2023).

Al-Somairi, M. A. A. et al. Correlation between the three-dimensional maxillomandibular complex parameters and pharyngeal airway dimensions in different sagittal and vertical malocclusions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 52, 20220346. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20220346 (2023).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146 (2007).

Chianchitlert, A., Luppanapornlarp, S., Saenghirunvattana, B. & Sirisoontorn, I. A. Comparative assessment of the upper pharyngeal airway dimensions among different anteroposterior skeletal patterns in 7-14-Year-Old children: A cephalometric study. Child. (Basel). 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081163 (2022).

Kamak, H. & Celikoglu, M. Facial soft tissue thickness among skeletal malocclusions: is there a difference? Korean J. Orthod. 42, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2012.42.1.23 (2012).

Moate, S. & Darendeliler, M. A. Cephalometric norms for the chinese: a compilation of existing data. Aust. Orthod. J. 18, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.2478/aoj-2002-0003 (2002).

Zhong, Z., Tang, Z., Gao, X. & Zeng, X. L. A comparison study of upper airway among different skeletal craniofacial patterns in nonsnoring Chinese children. Angle Orthod. 80, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.2319/030809-130.1 (2010).

Habumugisha, J. et al. Analysis of maxillary arch morphology and its relationship with upper airway in mouth breathing subjects with different sagittal growth patterns. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 124, 101386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jormas.2023.101386 (2023).

Habumugisha, J. et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of pharyngeal airway and maxillary arch in mouth and nasal breathing children with skeletal class I and II. BMC Oral Health. 22, 320. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02355-3 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Hyoid bone position in subjects with different facial growth patterns of different dental ages. Cranio 41, 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2020.1867471 (2023).

Alves, M., Baratieri, C., Nojima, L. I., Nojima, M. C. G. & Ruellas, A. C. O. Three-dimensional assessment of pharyngeal airway in nasal- and mouth-breathing children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 75, 1195–1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.06.019 (2011).

Thribhuvanan, L. & Saravanakumar, M. S. Influence of mode of breathing on pharyngeal airway space and Dento facial parameters in children: a short clinical study. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 46, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00802-3 (2022).

Juliano, M. L. et al. Polysomnographic findings are associated with cephalometric measurements in Mouth-Breathing children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 05, 554–561. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.27657 (2009).

Corrêa, E. C. & Bérzin, F. Mouth breathing syndrome: cervical muscles recruitment during nasal inspiration before and after respiratory and postural exercises on Swiss ball. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 72, 1335–1343 (2008).

Pullinger, A. G., Hollender, L., Solberg, W. K. & Petersson, A. A tomographic study of mandibular condyle position in an asymptomatic population. J. Prosthet. Dent. 53, 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(85)90029-0 (1985).

ElShebiny, T., Morcos, S., El, H. & Palomo, J. M. Comparing different software packages for measuring the oropharynx and minimum cross-sectional area. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 161 (e232), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.04.024 (2022).

Paknahad, M., Shahidi, S., Iranpour, S., Mirhadi, S. & Paknahad, M. Cone-Beam computed tomographic assessment of mandibular condylar position in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction and in healthy subjects. Int. J. Dent. 2015 (301796). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/301796 (2015).

Alves, M. Jr. et al. Evaluation of pharyngeal airway space amongst different skeletal patterns. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 41, 814–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2012.01.015 (2012).

Dahlberg, G. Statistical methods for medical and biological students. Indian Med. Gaz. 76, 440–440 (1941).

Lenza, M. A. et al. Radiographic evaluation of orthodontic treatment by means of four different cephalometric superimposition methods. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 20, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.20.3.029-036.oar (2015).

Kim, J. J. et al. Reliability and accuracy of segmentation of mandibular condyles from different three-dimensional imaging modalities: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 49, 20190150. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20190150 (2020).

Park, I. Y., Kim, J. H. & Park, Y. H. Three-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography based comparison of condylar position and morphology according to the vertical skeletal pattern. Korean J. Orthod. 45, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2015.45.2.66 (2015).

Ikeda, K. & Kawamura, A. Assessment of optimal condylar position with limited cone-beam computed tomography. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 135, 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.05.021 (2009).

Akbulut, A. & Kilinc, D. D. Evaluation of condyle position in patients with angle class I, II, and III malocclusion using cone-beam computed tomography panoramic reconstructions. Oral Radiol. 35, 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11282-018-0326-z (2019).

Elagib, T., Kyung, H. M., Hung, B. Q. & Hong, M. Assessment of pharyngeal airway in Korean adolescents according to skeletal pattern, sex, and cervical vertebral maturation: A cross-sectional CBCT study. Korean J. Orthod. 52, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod21.267 (2022).

Claudino, L. V., Mattos, C. T. & Ruellas, A. C. Sant’ Anna, E. F. Pharyngeal airway characterization in adolescents related to facial skeletal pattern: a preliminary study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 143, 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.01.015 (2013).

Guo, R. et al. Oropharynx and hyoid bone changes in female extraction patients with distinct sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns: a retrospective study. Head Face Med. 18, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-022-00334-1 (2022).

Nath, M., Ahmed, J., Ongole, R., Denny, C. & Shenoy, N. CBCT analysis of pharyngeal airway volume and comparison of airway volume among patients with skeletal class I, class II, and class III malocclusion: A retrospective study. Cranio 39, 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2019.1652993 (2021).

Chan, L., Kaczynski, R. & Kang, H. K. A cross-sectional retrospective study of normal changes in the pharyngeal airway volume in white children with 3 different skeletal patterns from age 9 to 15 years: part 1. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 158, 710–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.10.019 (2020).

Paknahad, M., Shahidi, S. & Abbaszade, H. Correlation between condylar position and different sagittal skeletal facial types. J. Orofac. Orthop. 77, 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-016-0039-z (2016).

Tsai, H. H., Ho, C. Y., Lee, P. L. & Tan, C. T. Cephalometric analysis of Nonobese snorers either with or without obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Angle Orthod. 77, 1054–1061. https://doi.org/10.2319/112106-477.1 (2007).

Jiang, Y. Y. Correlation between hyoid bone position and airway dimensions in Chinese adolescents by cone beam computed tomography analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 45, 914–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2016.02.005 (2016).

Cheng, J. H. et al. Comparison of Pharyngeal Airway between Mandibular Setback Surgery Patients (Skeletal Class III) and Nonsurgery Patients (Skeletal Classes I and II). Biomed. Res. Int. 5012037. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5012037 (2019).

Muto, T., Yamazaki, A. & Takeda, S. A cephalometric evaluation of the pharyngeal airway space in patients with mandibular retrognathia and prognathia, and normal subjects. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 37, 228–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2007.06.020 (2008).

Xu, X., Song, F., Wu, L., Zhang, L. & Liu, X. Investigation of the accuracy of dynamic condylar position: A model study. J. Dent. 143, 104889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2024.104889 (2024).

Alqhtani, N. R. et al. Temporomandibular Joint Space Dimensions among Saudi Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: MRI-Based Retrospective Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 5846255. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5846255 (2022).

Panchbhai, A. Temporomandibular joint space. Indian J. Oral Health Res. 3 https://doi.org/10.4103/ijohr.ijohr_37_17 (2017).

Paknahad, M. & Shahidi, S. Association between mandibular condylar position and clinical dysfunction index. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 43, 432–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2015.01.005 (2015).

Funding

This study was supported by the following funding sources: [1] Xi'an Jiaotong University Stomatological Hospital Key Discipline Direction Support Program, Project Title: Clinical Research on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Mouth Breathing Malocclusion, Project Number: 2024-LC-1. [2] Science and Technology Research and Development Project of Ankang City, Grant/Award Number: AK2023-SFZC-07 (Project of Wang Gaoli).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., A.O., and Y.T.L; methodology, M.M., and D.M. and J.W.L; validation, Z.X.W, Y.T.L and M.N; formal analysis, M.N.; cephalometric Assessment and Tracing, M.N.; Data curation, M.N., Y.L., and Y.Q.; writing¬¬-original draft preparation, M.N., A.O,; writing- review and editing, Y.C.G and R.Z; supervision, F.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This retrospective study was ethically approved by the Stomatological Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University Medical Ethics Committee under the ethical approval number: 2024-XJKQIEC-KY-QT-0052-001. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasih, M., Mbyayingabo, D., Li, Y. et al. Exploring the relationship between condylar position and pharyngeal airway dimensions using 3D analysis across different skeletal patterns. Sci Rep 15, 42153 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26127-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26127-5