Abstract

Extensive research has explored the use of machine perfusion to repair liver grafts, among these, interventions targeting mitochondrial repair are gaining attention due to its central role in ischemia-reperfusion injury and graft viability. Resveratrol, a mild natural polyphenol, is investigated here as a representative compound. Rat donor livers were subjected to 30 min of asystolic warm ischemia (DCD), followed by 2 h of either static cold storage (SCS), subnormothermic machine perfusion (SNMP) at 25 °C, or SNMP supplemented with resveratrol (SNMP-RES). All livers were subsequently reperfused under normothermic conditions for 1 h (NMP) with donor blood. Biochemical, transcriptomics RNA sequencing, inflammatory, and histological analyses were performed on perfusate samples and liver tissue biopsies. Resveratrol significantly enhanced the protective effects of SNMP, reducing perfusate AST (p = 0.03) and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) (p = 0.01). Resveratrol also decreased perfusate cytokine levels and improved tissue morphology. Transcriptomic analysis identified an upregulation of regenerative pathways using resveratrol, including Notch-signaling and Wnt signaling. The innate immune response was downregulated. This study represents the potential of FMN as a marker for liver quality during SNMP for the first time and demonstrates resveratrol’s effects during SNMP. These findings encourage further exploration of mitochondrial-targeted preservation strategies and validate long-term benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Machine perfusion, provide innovative approaches for evaluating and restoring donor organs1,2. Subnormothermic machine perfusion (SNMP) and hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) have been shown to reduce mitochondrial injury, replenishing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stores, essential for maintaining organ viability3,4,5. Multiple interventions during liver machine perfusion have targeted steatosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, regeneration, and cancer recurrence, supported by emerging short- and long-term biomarkers. As the primary source of ATP and a key regulator of oxidative stress and apoptosis, mitochondria remain a promising yet underexplored target.

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene), isolated from Polygonum cuspidatum6. is known for its diverse bioactivities, including antioxidative7,anti-inflammatory8, anti-ischemic9, as well as its modulatory effects on innate and adaptive immunity10. Additionally, resveratrol supports mitochondrial biogenesis and function, by increasing mitochondrial activity and number in hepatocytes and other cell types11. This study investigates resveratrol as a mitochondrial-protective agent during subnormothermic perfusion, supporting the broader potential of mitochondria-targeted therapies to improve liver graft viability and transplant outcomes.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (Approval Number: JLU-20230442). All experiments were performed in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines and relevant local regulations.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats weighing 250-320 g were used for all experiments.

Experimental design

-

1.

SCS group (S): static cold storage in University of Wisconsin (UW) solution (4 °C) for 2 h.

-

2.

SNMP group (M): subnormothermic machine perfusion (25 °C) for 2 h.

-

3.

SNMP-RES group (R): subnormothermic machine perfusion with resveratrol (25 °C) for 2 h.

-

4.

Control group (NAÏVE)(N): no extra preservation, immediate normothermic reperfusion.

All experimental groups consisted of at least 6 experiments per groups12, other details are illustrated in Fig. 1 and supplementary method.

Liver procurement and cold storage

Anesthesia was initiated with 5% isoflurane inhalation (RWD Life Science) and maintained with 2% isoflurane in oxygen at a continuous flow rate of 1.5 L/min. And the authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Following a midline incision, a catheter was placed in the abdominal aorta and 1 mL heparin (50 U/mL) was administered. Cardiac arrest was induced via diaphragmatic incision to establish a DCD model, initiating 30 min of asystolic warm ischemia4. During this period, 10 mL of donor blood was collected. The thoracic aorta was clamped, and the liver was flushed with 100 mL of cold saline (4 °C)13. After mobilization, the portal vein was catheterized, the bile duct was cannulated, and the hepatic artery ligated. Finally, 20 mL of cold UW solution was infused via the portal vein to ensure optimal preservation before cold storage or perfusion4,14,15.

SNMP and NMP

Livers in the SNMP and SNMP-RES groups were perfused (25 °C) immediately after warm ischemia. After that all livers were transferred to a 38 °C perfusion system (details in Supplementary Methods).

Enzymatic and metabolic analysis

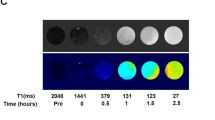

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT) were quantified using an automated biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Lactate, glucose, potassium, and calcium ions were measured using a blood gas and electrolyte analyzer (Gem Premier 3000, Beckman Coulter). FMN levels were assessed by fluorescence spectroscopy (BMG LABtech CLARIOSTAR, excitation 485 nm, emission 528 nm, autogain) after centrifugation.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining

Liver tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were stained with H&E for morphology and PAS for glycogen, then examined microscopically (NIKON) for vacuolization, sinusoidal congestion, and necrosis.

Cytokine measurement in perfusates and liver tissue

Cytokines in perfusates and liver homogenates (9 µg/µL) were quantified using a Luminex multiplex assay (Luminex X-200, BIO-RAD, LX-MultiDTR-10). Standard curves guided quantification after bead binding, antibody incubation, and fluorescence detection,

RNA sequencing and data analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) libraries from 9 liver samples (3 per group) were prepared using the KC-Digital™ Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Seqhealth Technology, Wuhan, China), incorporating 8-base unique molecular identifiers to minimize duplication and errors. Fragments (200-500 bp) were enriched and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X10 platform. Raw reads were trimmed and aligned to the Rattus norvegicus Rnor_6.0 genome. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with adjusted p < 0.05 and fold change > 2 or <-2. Functional enrichment was analyzed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)16,17,18 and Gene Ontology (GO). No original KEGG pathway images were reproduced in this manuscript. All enrichment results and figures (including bubble plots) were generated independently based on pathway annotations.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the median with 95% Cl for continuous variables. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a Mann-Whitney U test. For comparisons involving multiple groups, One-way/Two-way ANOVA was applied. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was employed to assess the relationship between two datasets, providing a measure of parametric correlation. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.0), figures are done by Biorender.com and R studio.

Results

1. Protective effects of resveratrol during subnormothermic machine perfusion

Optimizing the resveratrol concentration

In an initial 3-hour SNMP experiment, we tested different concentrations of resveratrol (1 µmol/L, 10 µmol/L, 50 µmol/L) and observed that 10 µmol/L provided the most significant protective effects19,20. At this concentration, perfusate levels of ALT, AST, and LDH, were significantly reduced compared to other concentrations (Supplementary Tables 1-4). Based on these findings, 10 µmol/L resveratrol was selected for further comparisons between the RES and SNMP groups under standardized perfusion conditions (Fig. 1).

Resveratrol decreases injury and inflammatory markers

In the RES group, ALT, AST, and LDH levels were significantly lower compared to the conventional SNMP group (p < 0.005), demonstrating reduced liver injury (Fig. 2). Additionally, resveratrol markedly decreased lactate release during perfusion (median 1.367 mmol/L, 95% CI 0.200-2.867 vs. median 2.033 mmol/L, 95% CI 0.200-5.000; p < 0.005), indicating improved metabolic stability (Fig. 2).

Resveratrol also significantly reduced the release of the mitochondrial marker flavin mononucleotide (FMN) (median 0.039 µg/ml, 95% CI 0.033-0.045 vs. median 0.101 µg/ml, 95% CI 0.034-0.163; p < 0.001), suggesting enhanced mitochondrial protection. Correlation analysis revealed positive relationships between FMN release and levels of AST, ALT and LDH, further underscoring the link between mitochondrial integrity and liver injury (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

From an inflammatory perspective, resveratrol significantly decreased the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β (p < 0.005) and IL-6 (p < 0.001) during perfusion (Fig. 2). At the end of the perfusion period, liver tissue from the SNMP-RES group demonstrated better preserved histological structure and higher glycogen depletion compared to the SNMP group. These findings highlight the protective effects of resveratrol on liver morphology and glucose metabolic (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

2. Positive effects of Resveratrol during reperfusion

Reperfusion following liver transplantation is a critical phase where significant ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) often occurs. In this study, NMP with donor blood was utilized to simulate the in vivo reperfusion phase following liver transplantation. This approach mimics the physiological conditions of reperfusion after graft implantation, allowing for the assessment of IRI and the evaluation of liver function, metabolism, and inflammation in a controlled ex vivo environment. And comparative analysis among the Res, Naïve, SCS, and SNMP groups revealed that the SCS group exhibited the highest levels of ALT and AST (median 130 U/L, 95% CI 15.83-205.30), indicative of greater liver injury (Fig. 3). In contrast, both the Res (AST, median 35.55 U/L, 95% CI 17.38-54.08), and Naïve groups demonstrated markedly lower enzyme levels, reflecting superior liver protection of Res (Fig. 3).

During the reperfusion phase (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3), lactate and glucose levels showed no significant differences across groups. However, compared to the SCS group, the Res, Naïve, and SNMP groups consistently displayed relatively lower concentrations of both, suggesting better metabolic regulation. For ionic parameters, the SCS group had the highest K⁺ levels and the lowest calcium Ca²⁺ levels, further indicating disrupted ionic homeostasis, such as Inactivation of the sodium-potassium pump and influx of calcium ions.

Less FMN release during res reperfusion

The release of flavin mononucleotide (FMN), a marker of mitochondrial dysfunction, was notably lower in the Res group compared to the SCS, SNMP, and Naïve groups (Fig. 3). Interestingly, FMN release during the 1-hour reperfusion phase was significantly higher than during the preceding 2-hour perfusion phase (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5), likely due to contributions from systemic FMN release in the donor blood and higher temperature of reperfusion. Correlation analysis confirmed positive associations between FMN levels and ALT/AST, while FMN showed negative correlations with glucose and Ca²⁺ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Transcriptomic analysis of liver tissue post-reperfusion

To further investigate the effects of resveratrol during reperfusion, RNA-Seq analysis was performed on liver tissues from the SCS, SNMP, and RES groups. Significant transcriptomic differences were observed among the groups, highlighting the distinct molecular impacts of different preservation methods (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

SNMP vs. SCS

Compared to SCS, SNMP resulted in the differential expression of numerous genes. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the upregulated pathways in SNMP were ATP metabolic process, glucose homeostasis, NIK/NF-kappaB signaling and regulation of innate immune response (Fig. 5d), while downregulated pathways in SNMP were primarily associated with apoptotic process, inflammatory response, Fc-gamma receptor signaling pathway, and aging (Supplementary Fig. 6d). KEGG pathway analysis further confirmed significant downregulation of pathways such as tight junctions and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Supplementary Fig. 6f).

Experimental design and perfusion system. (a) Four rat liver groups underwent 30-min warm ischemia (DCD), then preservation: SCS (4 °C UW solution), SNMP (25 °C), or SNMP + RES (25 °C with resveratrol). All groups received 1-h NMP reperfusion (38 °C diluted donor blood). Six livers/group, plus naïve controls (ischemia + direct reperfusion). Schematic shows timeline and sampling points. (b) Perfusion circuit components: roller pump, oxygenator, reservoir, bubble trap, heating coil, and temperature monitor. Open-circuit design with unrestricted outflow (figure designed with biorender.com). (c) Portal vein pO₂ and pCO₂ levels during 2-h perfusion (SNMP vs. SNMP + RES groups).

Metabolic and Inflammatory Responses after 2-hour perfusion in SNMP and RES groups. Metabolite release, FMN dynamics, cytokine levels (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10) and liver histology (H&E/PAS staining) were analyzed during 2-hour perfusion (SNMP vs. RES groups). Perfusate measurements included AST, ALT, LDH, lactate and FMN at set intervals, with FMN-AST correlations assessed (n = 3-4/group/timepoint). Cytokine data show 2 h/baseline ratios (n = 3/group, median with 95% CI). Histological evaluation included Suzuki scoring (H&E) and PAS quantification.Data show median (95% CI); Mann-Whitney U test and two-way ANOVA determined significance, Pearson’s tested correlations (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001).

Metabolite release and Inflammatory Responses during the 1-hour reperfusion period. Perfusate metabolites (AST, lactate, Ca²⁺) and FMN were measured during 1-hour normothermic reperfusion following different preservation strategies (n = 4/group). FMN correlations with AST and lactate were assessed by Pearson’s analysis. In parallel, cytokines (IL-1β, IL-10) and histological changes (H&E and PAS staining) were evaluated after 1-hour reperfusion across four groups (Naïve, SCS, SNMP, RES; n = 3/group). Cytokine ratios (1 h/0 h) and histological injury scores (Suzuki and PAS) are presented as median with 95% CI. Group differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for metabolites and one-way ANOVA for cytokines and histology (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001).

RNA sequencing and functional enrichment analysis of liver tissue after 1 h normothermic reperfusion. DEGs from liver RNA-seq (n = 3/group: SCS, SNMP, RES) are shown in heatmaps (RES vs. SNMP) (a). Sirt1 expression is compared across groups (b). GO enrichment analysis (bubble plots) highlights upregulated pathways in RES vs. SNMP (c) and SNMP vs. SCS (d). Data are median (95% CI); one-way ANOVA for comparisons (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001).

Resveratrol mitigates mitochondrial injury and downstream inflammation during subnormothermic machine reperfusion. Resveratrol, in combination with machine perfusion, optimizes mitochondrial function and mitigates inflammation during reperfusion, contributing to improved liver graft outcomes. (a) Anaerobic respiration in the SCS group impairs oxidative phosphorylation, leading to increased ROS, such as O2-. This upstream mechanism involves succinate and NADH accumulation, which increases mitochondrial Ca2 + flux and promotes the release of FMN from NDUFS-1 in electron transfer complex I. Downstream, ATP-dependent Ca2 + channel inhibition exacerbates intracellular Ca2 + accumulation, resulting in membrane damage and cell death in conjunction with excessive ROS production. (b) In contrast, aerobic respiration during machine perfusion generates more ATP, reduces succinate and NADH accumulation, and preserves mitochondrial function. Consequently, during reperfusion, machine perfusion leads to lower ROS production and reduced FMN release into the perfusate, offering better mitochondrial protection compared to SCS. (c) Building on this, SNMP combined with RES further enhances mitochondrial and inflammatory regulation, resveratrol activates SIRT1, inhibiting RelA acetylation and promoting the degradation of IκBα, thereby reducing NF-κB-mediated expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MMPs. (d) Additionally, cAMP activates PKA, which stimulates SIRT1. AMPK regulates SIRT1 activity by modulating intracellular levels of NAD+. Increased NAD + levels activate SIRT1, leading to the deacetylation and activation of PGC-1α, which supports mitochondrial activity and promotes energy homeostasis. The design of the figure was supported by biorender.com.

RES vs. SNMP

In the RES group, Sirt1 was significantly upregulated compared to other groups (Fig. 4), highlighting key pathways associated with cellular regeneration and stress adaptation (Fig. 4). Upregulated pathways included the Notch signaling pathway, positive regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway, and regulation of cell growth, suggesting an enhanced capacity for cellular regeneration and proliferation. Additionally, the negative regulation of the ERK1 and ERK2 cascade and the inactivation of MAPK activity indicate anti-inflammatory effects mediated by resveratrol. Upregulation of cAMP response element binding further suggests that resveratrol may stimulate SIRT1 activation, aligning with its known mechanisms of action (Fig. 5). Conversely, genes involved in riboflavin metabolism and bile secretion were downregulated in the RES group compared to SNMP (Supplementary Fig. 6a.c).

Cytokine profiles in perfusate and liver tissue

During reperfusion, the Naïve group displayed elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4), including Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-2 (IL-2), Interleukin-4 (IL-4), Interleukin-5 (IL-5), and Interleukin-12 (p70 subunit) (IL-12p70) in the perfusate. Conversely, the SNMP group showed higher levels of Interleukin-10 (IL-10) and Growth-Regulated Oncogene / Keratinocyte Chemoattractant (GRO/KC) (neutrophil chemoattractant that can recruit neutrophils to the site of inflammation). Interestingly, perfusate cytokine levels in the SCS and Res groups were either reduced or remained stable post-reperfusion.

In liver tissue (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4,7), cytokine expression patterns different from those observed in the perfusate. There were no significant differences in most cytokines before and after reperfusion in liver tissue. However, the Naïve group showed a pronounced increase in IL-1β and IL-5, both in liver tissue and perfusate, compared to other groups. In contrast, cytokine levels in liver tissues from the SNMP, SCS, and Res groups remained relatively stable or slightly decreased, except for GRO/KC and IL-12p70 (critical regulator of adaptive immunity, promoting Th1 differentiation and enhancing Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) mediated responses), which exhibited an upward trend in all groups (Ratio > 1.0).

Histological analysis

Histological examination revealed inflammatory cell infiltration in the Naïve, SCS, and SNMP groups post-reperfusion, as observed in H&E-stained sections (Fig. 3). In the Res group, liver tissue exhibited reduced inflammatory infiltration, suggesting improved protection. PAS staining showed that the Naïve group, with no extended preservation time, retained higher glycogen levels. The SCS group also displayed minimal glycogen depletion due to static cold storage. In contrast, both the SNMP and Res groups had lower glycogen content, reflecting increased energy consumption and enhanced aerobic respiration (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study confirms the protective effects of resveratrol in DCD livers during machine perfusion. It significantly reduced injury during both perfusion and reperfusion by downregulating Sirt1, suppressing cytokine release, and preserving mitochondrial and tissue integrity. Preliminary data also identified 10 µmol/L as the optimal concentration, providing greater protection than other doses tested.

As previously published and demonstrated by our data in this study, resveratrol exerts significant anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects through the activation of sirtuin-1 (SIRT1)21. As a key deacetylase, SIRT1 is crucial for maintaining immune tolerance22 and achieves this by suppressing the Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR-4)/ Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB)/ Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) signaling pathway, thereby reducing the production of inflammatory mediators23. Resveratrol binding enhances SIRT1’s interaction with the RelA/p65 substrate24, modulating leukocyte activation and the pro-inflammatory cytokine pathway25. By inhibiting RelA acetylation through SIRT1 activation, resveratrol downregulates the expression of inflammatory genes, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs), and Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which are regulated by NF-κB22. Additionally, resveratrol acts as a dual inhibitor of NF-κB signaling by reducing cellular sensitivity to NF-κB-mediated responses and suppressing TNF-α-induced apoptosis28. The activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol also inhibits phospho-p38 MAPK activity and decreases NF-κB p65 signaling, further contributing to its anti-inflammatory effects29.

As for the inflammatory, machine perfusion is known to induce an inflammatory response, partially mimicking perfusion after ischemia and activating inflammatory pathways through the artificial perfusion circuit30. In this study, resveratrol significantly reduced key inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ) in the perfusate. By the end of perfusion, cytokine levels in liver tissue remained substantially higher than in the perfusate, suggesting tissue cytokine levels cannot be inferred from perfusate alone. Notably, resveratrol had a milder effect on tissue cytokines, possibly due to the time required to influence gene expression and protein synthesis.

While during reperfusion, most perfusate cytokine decreased, only the naïve group demonstrated relatively higher expression. This may be based on the absence of flush or perfusion in the naïve group, leading to amplified inflammatory signaling triggered by interactions between circulating cytokines and Kupffer cells/ neutrophils immediately after DCD (30 min of warm ischemia). This phenomenon appears consistent with the pro-inflammatory effects observed during direct NMP with donor blood. And although SNMP partially mitigates these effects through its lower temperature and better enzymatic profiles, alternative preservation methods like hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) have been shown to be even more effective in protecting liver cells and particularly mitochondria31. Importantly, though cytokines in the perfusate provide valuable insights32, the differences observed between perfusate and liver tissue cytokine levels emphasize that liver tissue, including hepatocyte, cholangiocyte, and endothelial cell homeostasis, is a more reliable indicator of graft quality. Thus, combining perfusate markers with assessments of intrinsic liver cell stability is essential for accurately evaluating organ viability.

Resveratrol also enhances mitochondrial activity by promoting SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α)33.Additionally, it improves insulin sensitivity, reduces insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) levels, and activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), collectively driving changes associated with increased lifespan11. During perfusion, even within the relatively short 2-hour perfusion period, lactate release was markedly lower in the Res group, alongside reduced perfusate glucose depletion, decreased FMN and reduced glycogen accumulation in PAS staining, these indicate improved aerobic metabolism as well as a shift toward more efficient energy utilization during aerobic respiration.

During reperfusion, despite the short 1-hour window, the SCS group showed disrupted ionic homeostasis, likely due to anaerobic byproduct accumulation (lactate, superoxide radicals, succinate, NADH) during cold storage. Oxygen reintroduction triggered a sudden release of these metabolites, worsening necrosis and apoptosis. Glucose homeostasis was also impaired, as indicated by elevated perfusate glucose. This may reflect feedback inhibition of glucose transporter expression and reduced uptake, along with functional GLUT impairment from low metabolic demand, stress responses, and oxidative damage34,35. These factors collectively contributed to the disruption of glucose utilization and the diminished metabolic capacity of the SCS liver. Since metabolic activity and ATP consumption are reduced at lower organ temperatures, the accumulation of energy in the PAS staining during SCS is expected, too, and perfusion will surely rise ATP consumption due to energy-demanding processes3.

Interestingly, the baseline FMN levels during reperfusion were comparable across the naïve, SNMP, and RES groups but were elevated in the SCS group at the onset of reperfusion. This discrepancy may result from the early sampling process, where initial (0 min) perfusate outflow from the liver had already mixed with the recirculating reservoir during the first several minutes, leading to a higher baseline FMN level in the SCS group. Despite this, livers in the RES group consistently showed reduced FMN release, reflecting its protective effects on mitochondrial injury. Other than that, FMN release is positive related with liver injury markers (AST, ALT), whereas lactate showed a weaker correlation. This aligns with our center (Cleveland Clinic) NMP finding, which indicate that lactate release is not always a reliable indicator of liver quality during machine perfusion. And based on the similar structure, the FMN spectrum showed an overlapping emission spectrum with resveratrol, after adjusting for this overlap, FMN signals remained stable throughout the perfusion period in the RES-and all other groups. Another possibility of low FMN is that Res might decrease the riboflavin metabolism, which results the FMN maintain at a stable, low level.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the perfusion circuit used in this experiment was relatively simple, lacking pressure controls and dialysis system for long term perfusion. Additionally, no perfusion parameters related to bile production were recorded or statistically analyzed due to minimal bile output during perfusion/reperfusion, limiting the evaluation of this important functional marker. Second, while the SNMP duration of 2 h was selected based on the reported benefits of short-term machine perfusion36,37, the perfusion and reperfusion durations in this study remain relatively short. Moreover, during organ procurement, the administration of heparin and the collection of donor blood significantly reduced liver injury, and the lack of subsequent liver transplantation in this study limits the ability to evaluate long-term graft viability and functional outcomes. Third, although transcriptomic analyses were complemented by cytokine measurements, the Sirt pathway and many other pathways’ protein-level validation were not performed. This is particularly relevant given the slower dynamics of protein expression compared to transcriptional and cytokine changes. Long-term perfusion or transplantation experiments would be required to better understand the downstream protein-level effects of the observed molecular changes.

Conclusions

In summary, this study represents the potential of FMN as a marker for liver quality during SNMP for the first time and demonstrates resveratrol’s effects during SNMP. These findings encourage further exploration of mitochondrial-targeted preservation strategies and validate long-term benefits.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The raw RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA 1309769.

References

Nasralla, D. et al. A randomized trial of normothermic preservation in liver transplantation. Nature 557 (7703), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0047-9 (2018).

Schlegel, A. et al. A multicenter randomized-controlled trial of hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) for human liver grafts before transplantation. J. Hepatol. 78 (4), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.12.030 (2023).

Karimian, N. et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion of steatotic livers results in increased energy charge at the cost of Anti-Oxidant capacity compared to normothermic perfusion. Metabolites 9 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110246 (2019).

Schlegel, A. et al. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion protects from mitochondrial injury before liver transplantation. EBioMedicine 60, 103014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103014 (2020).

Schlegel, A., Porte, R. J. & Dutkowski, P. Protective mechanisms and current clinical evidence of hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion (HOPE) in preventing post-transplant cholangiopathy. J. Hepatol. 76 (6), 1330–1347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.01.024 (2022).

Nonomura, S., Kanagawa, H. & Makimoto, A. Chemical constituents of polygonaceous plants. I. Yakugaku Zasshi. 83 (10), 988–990. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi1947.83.10_988 (1963).

Meng, Q. et al. Dietary Resveratrol improves antioxidant status of sows and piglets and regulates antioxidant gene expression in placenta by Keap1-Nrf2 pathway and Sirt1. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-018-0248-y (2018).

Nunes, S., Danesi, F., Del Rio, D. & Silva, P. Resveratrol and inflammatory bowel disease: the evidence so far. Nutr. Res. Rev. 31 (1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095442241700021X (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Resveratrol protects against global cerebral ischemic injury in gerbils. Brain Res. 958 (2), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03543-6 (2002).

Falchetti, R., Fuggetta, M. P., Lanzilli, G., Tricarico, M. & Ravagnan, G. Effects of Resveratrol on human immune cell function. Life Sci. 70 (1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01367-4 (2001).

Baur, J. A. et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 444 (7117), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05354 (2006).

De Vries, R. J. et al. Cell release during perfusion reflects cold ischemic injury in rat livers. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57589-4 (2020).

Hisada, M. et al. Successful transplantation of reduced sized rat alcoholic fatty livers made possible by mobilization of host stem cells. Am. J. Transpl. Off J. Am. Soc. Transpl. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 12 (12), 3246–3256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04265.x (2012).

Man, K. et al. Liver transplantation in rats using small-for-size grafts: A study of hemodynamic and morphological changes. Arch. Surg. 136 (3), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.136.3.280 (2001).

Oldani, G., Lacotte, S., Morel, P., Mentha, G. & Toso, C. Orthotopic liver transplantation in rats. JoVE J. Vis. Exp. (65), e4143. https://doi.org/10.3791/4143 (2012).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. Publ Protein Soc. 28 (11), 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Juan, S. H., Cheng, T. H., Lin, H. C., Chu, Y. L. & Lee, W. S. Mechanism of concentration-dependent induction of Heme oxygenase-1 by Resveratrol in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 69 (1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.015 (2005).

Ray, P. S. et al. The red wine antioxidant Resveratrol protects isolated rat hearts from ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol. Med. 27 (1–2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00063-5 (1999).

Saiko, P., Szakmary, A., Jaeger, W. & Szekeres, T. Resveratrol and its analogs: defense against cancer, coronary disease and neurodegenerative maladies or just a fad? Mutat. Res. Mutat. Res. 658 (1), 68–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.004 (2008).

Gao, B., Kong, Q., Kemp, K., Zhao, Y. S. & Fang, D. Analysis of Sirtuin 1 expression reveals a molecular explanation of IL-2–mediated reversal of T-cell tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109 (3), 899–904. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118462109 (2012).

Adhami, V. M., Afaq, F. & Ahmad, N. Suppression of ultraviolet B exposure-mediated activation of NF-κB in normal human keratinocytes by Resveratrol. Neoplasia 5 (1), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80019-2 (2003).

Yeung, F. et al. Modulation of NF-κB‐dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 23 (12), 2369–2380. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244 (2004).

Bonizzi, G. & Karin, M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25 (6), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008 (2004).

Baur, J. A. & Sinclair, D. A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5 (6), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2060 (2006).

Yi, H. et al. Resveratrol alleviates the interleukin-1β-induced chondrocytes injury through the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. 15 (1), 424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01944-8 (2020).

Manna, S. K., Mukhopadhyay, A. & Aggarwal, B. B. Resveratrol suppresses TNF-induced activation of nuclear transcription factors NF-kappa B, activator protein-1, and apoptosis: potential role of reactive oxygen intermediates and lipid peroxidation. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md. 1950. 164 (12), 6509–6519. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6509 (2000).

Pan, W., Yu, H., Huang, S. & Zhu, P. Resveratrol protects against TNF-α-induced injury in human umbilical endothelial cells through promoting sirtuin-1-induced repression of NF-KB and p38 MAPK. PloS One. 11 (1), e0147034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147034 (2016).

Day, J. R. S. & Taylor, K. M. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome and cardiopulmonary bypass. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 3 (2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2005.04.002 (2005).

Schlegel, A., Kron, P., Graf, R., Dutkowski, P. & Clavien, P. A. Warm vs. cold perfusion techniques to rescue rodent liver grafts. J. Hepatol. 61 (6), 1267–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.023 (2014).

Carlson, K. N. et al. Interleukin-10 and transforming growth Factor-β cytokines decrease immune activation during normothermic ex vivo machine perfusion of the rat liver. Liver Transpl. Off Publ Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis. Int. Liver Transpl. Soc. 27 (11), 1577–1591. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.26206 (2021).

Lagouge, M. et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 127 (6), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013 (2006).

Song, L., Li, Y. & Xu, M. Exogenous nucleotides ameliorate insulin resistance induced by palmitic acid in HepG2 cells through the IRS-1/AKT/FOXO1 pathways. Nutrients 16 (12), 1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121801 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. TXNIP-mediated crosstalk between oxidative stress and glucose metabolism. PloS One. 19 (2), e0292655. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292655 (2024).

Abraham, N. et al. Two compartment evaluation of liver grafts during acellular room temperature machine perfusion (acRTMP) in a rat liver transplant model. Front. Med. 9, 804834. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.804834 (2022).

van Rijn, R. et al. Hypothermic machine perfusion in liver Transplantation — A randomized trial. N Engl. J. Med. 384 (15), 1391–1401. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2031532 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: CJ, ML and GL designed the study from inception and conceptualized approaches. Data collection: CJ collected data. Data analysis: CJ, AS, ML, XS and HY. Manuscript writing: CJ and AS were responsible for primary editing of the manuscript. GL and AS coordinated all collaborations and provided overall guidance and supervision of the manuscript. Revision and critical discussion: all coauthors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Schlegel serves as a paid consultant for Bridge-to-Life Ltd and OrganOx. Chunbao Jiao, Mingqian Li, Xiaodong Sun, Heidi Yeh and Guoyue Lv declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (Approval Number: JLU-20230442), and the study was reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. And the authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiao, C., Li, M., Sun, X. et al. Optimizing DCD donor liver function with resveratrol during machine perfusion. Sci Rep 15, 42092 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26147-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26147-1