Abstract

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with elevated rates of insulin resistance and chronic metabolic disease, yet its detailed metabolic and lipidomic profiles, particularly in pediatric populations, remain poorly defined. To characterize plasma lipid profiles in children and young adults with DS and overweight or obesity, to determine degree of lipid heterogeneity and if the observed dyslipidemia is independent of obesity severity. An extended objective is to search for metabolite features that may differentiate DS from weight‑matched controls. Plasma samples from 12 African‑American participants with DS (age 11–21 years, all overweight or obese) and 513 age‑matched overweight or obese controls were profiled by Nightingale 1H‑NMR spectroscopy (249 metabolites). Because all participants with DS in our cohort were overweight or obese, we restricted the control group to individuals with comparable weight status to minimize confounding by adiposity. Metabolites were log₂‑transformed and standardized to z-scores. Partial least‑squares discriminant analysis (two components) was followed by k‑means clustering (k = 2). Cluster distributions were compared by χ² test, and metabolite differences between clusters, stratified by obesity class, were assessed using Welch’s t‑tests and Benjamini-Hochberg false‑discovery correction. Nine of twelve DS samples (75%) clustered into a dyslipidemic profile (cluster 1), compared to 209 of 513 controls (41%), demonstrating a significant enrichment (p = 0.033). Among controls, cluster assignment showed no association with obesity class. Across all obesity strata, 92 metabolites consistently differed between clusters. Cluster 1 exhibited a distinct lipidomic pattern marked by triglyceride enrichment across the lipoprotein spectrum [from extra-extra-large very-low-density lipoprotein (XXL-VLDL) to high-density lipoprotein (HDL)], elevated remnant cholesterol, increased intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) and HDL particle concentrations, and cholesterol-ester-poor, triglyceride-rich HDL particles. Additionally, this cluster showed elevated levels of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, alongside a relative depletion of Ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Together, these features recapitulate a lipid profile associated with insulin resistance and pro-inflammatory metabolic dysfunction. A lipidomic profile characterized by high triglyceride and low cholesterol ester content is highly prevalent among children with DS and overweight or obesity, and present in approximately 40% of overweight or obese controls, irrespective of obesity severity. This insulin-resistant phenotype, independent of adiposity, likely reflects intrinsic alterations in lipid metabolism. The use of the Nightingale 1H‑NMR offers a scalable and clinically accessible platform for detecting this metabolic signature, offering promise for early risk stratification and precision management of metabolic dysfunction in DS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) affects approximately one in 700–1000 live births1 and is now accompanied by a median life expectancy exceeding 60 years2, shifting clinical priorities toward chronic metabolic diseases. Cardiometabolic disorders have emerged as an important threat in this population3. Children and young adults with DS show higher rates of overweight and obesity than their neurotypical peers4, as well as an increased prevalence of non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)5. Adults with DS exhibit early-onset cardiometabolic complications, including accelerated atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes6,7, along with the almost universal development of Alzheimer’s neuropathology by midlife8. Multiple genes on chromosome 21 are known to influence lipid metabolism and inflammatory signaling (e.g., SOD1 increases oxidative stress; APP drives amyloid processing; and ABCG1, a key mediator of cholesterol efflux) potentially predisposing individuals with DS to dyslipidemia and metabolic dysfunction9,10, thereby amplifying both cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease risk. Taken together, these findings point to an urgent need for systematic cardiometabolic surveillance in DS, especially in pediatric cohorts where targeted lifestyle or pharmacologic interventions could most effectively attenuate long-term cardiovascular and metabolic risk.

To address this need, we applied high-resolution proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) metabolomics to characterize the plasma lipid profile of African-American children and young adults with DS and overweight or obesity, compared to weight-matched controls. This study aimed to determine whether DS is associated with a distinct, obesity-independent lipidomic signature that may underlie the elevated cardiometabolic risk in this population.

Methods

Subjects

Pediatric participants (≤ 21 years, American Academy of Pediatrics definition)11 were recruited prospectively through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Center for Applied Genomics (CAG) between 2002 and 2020. All self‑identified as African American to minimize population‑stratification bias in downstream genetic analyses. Written informed consent (parental consent for minors) was obtained for all procedures. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHOP and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the U.S. Common Rule (45 CFR 46), and all relevant institutional and federal guidelines for research involving human participants. The study comprised 12 individuals with DS (10 female, 2 male; age 11–21 years), all of whom met criteria for overweight or obesity (3 overweight, 3 Class I obese, 2 Class II obese, 4 Class III obese), and 513 age-matched controls (270 female, 243 male; age 11–21 years) after exclusion of normal‑weight and under‑weight individuals. Since all participants with DS were overweight or obese, the control cohort was limited to individuals with similar weight status, enabling identification of metabolic features associated with DS independent of obesity severity. Among controls, 171 were classified as overweight, 147 as Class I obese, 91 as Class II obese, and 104 as Class III obese. For the control cohort, weight categories were assigned using CDC growth‑chart percentiles for participants ≤ 19 years12,13 and standard adult cut‑offs for those older than 19 years. For the DS patients, BMI values were also compared against the DS-specific BMI-for-age reference curves14, confirming that all participants were at least overweight and most met criteria for obesity. Individuals with sickle‑cell disease, type 1 diabetes, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, HIV infection, or other known Mendelian disorders (e.g., cystic fibrosis or single-gene metabolic disorders) were excluded to avoid metabolic confounding. Additional details regarding the metabolic characterization of control participants with obesity were reported in our related study15, which included a subset of participants from the current cohort.

Metabolomic profiling

Venous blood was collected after an overnight fast into EDTA tubes and centrifuged within two hours of collection to obtain plasma. Aliquots were transferred to cryovials, immediately frozen, and maintained at −80 °C under continuous temperature monitoring within the CAG biobank. Plasma specimens were archived within the CAG automated biorepository, which uses robotic storage and retrieval to prevent temperature fluctuations associated with manual handling and thereby preserve long-term sample integrity. Each vial carries a unique two-dimensional barcode linked to the laboratory information-management system (LIMS), ensuring complete traceability from collection through analysis. All aliquots used for this study were confirmed to have remained frozen without prior thaw cycles. All samples were analyzed in a single batch to minimize storage-time and inter-batch variability.

Metabolite quantification was performed using Nightingale Health’s 1H-NMR spectroscopy platform (version 2020)16, which operates within an ISO-certified quality framework. The platform simultaneously acquires lipid, lipoprotein, and low-molecular-weight metabolite spectra using standardized acquisition sequences and automated quality-control procedures. Concentrations for 249 biomarkers, including lipoprotein subclass distributions, apolipoproteins, fatty-acid fractions, amino acids, and glycolysis-related intermediates, were derived through traceable regression models calibrated against chemical reference methods17,18.

Data analysis

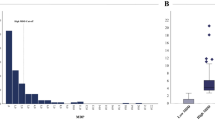

The resulting datasets were initially imported into R (v4.4.1)19 for preprocessing. To prepare the data for analysis, each metabolite concentration was log₂-transformed (adding 1 × 10⁻⁹ to handle zeros) and then standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation, yielding z-scores for all features. Features with more than 20% missing values were removed. No biomarkers in the 249-marker panel exceeded this threshold, except for Glycerol, which was originally included in the panel but is not part of the final 249 biomarkers. The workflow then transitioned to Python (v 3.9.18)20, using scikit-learn (v1.6.1) and related packages for further analysis21. Missing values were imputed using the median (SimpleImputer, scikit-learn)21. We then retained the 100 metabolites exhibiting the greatest variance across all samples. To adjust for obesity class (1 = overweight; 2 = Class I obesity; 3 = Class II obesity; 4 = Class III obesity), each metabolite concentration was regressed on obesity status using LinearRegression (scikit-learn). The residuals, representing the variability in metabolite concentrations after accounting for obesity, were extracted. These residuals were mean-centered and rescaled to unit variance using StandardScaler (scikit-learn)21, ensuring that only the obesity-independent variability was considered in the clustering and t-tests. The standardized residuals were then used as the input matrix for Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA)22 to identify metabolomic patterns distinguishing DS participants from weight-matched controls and to determine whether these differences were independent of obesity severity. The PLS-DA model, comprising two latent components, was fitted to maximize separation between the DS and control groups. Samples were projected onto the first two PLS components (PLS1, PLS2) for visualization. The robustness of the PLS-DA model was evaluated using 10-fold cross-validation and 1,000-iteration permutation testing. Cross-validated performance supported non-random separation between DS and controls (Q2 = −0.003; mean AUC = 0.698 ± 0.187; permutation-test p = 0.038). K-means clustering (k = 2) was then applied to the two-component PLS-DA score space as an unsupervised method to identify natural sample clusters, without using diagnostic labels, to test for DS enrichment within the data-driven clusters.

Metabolite differences between the two PLS-DA-derived clusters were then evaluated within the control subset only, to avoid the confounding effects of DS diagnosis. For each metabolite, distributions in cluster 1 versus cluster 0 were compared using Welch’s t-test. Raw p-values were adjusted for multiple testing by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). To avoid confounding by heterogeneity across obesity classes, a stratified analysis was performed using the same approach for each obesity class.

Results

PLS‑DA followed by k‑means clustering (Fig. 1) separated the cohort into two data‑driven groups. Cluster 1 contained 9 of 12 DS samples, but only 209 of 513 weight‑matched controls (Fisher’s Exact Test p = 0.033), indicating significant enrichment of DS in cluster 1. To determine whether cluster membership varied by obesity severity, we tabulated cluster counts across the four overweight/obesity classes in controls and performed a χ² test of independence. No significant association was observed between obesity class and cluster assignment (Supplementary Table 1), demonstrating that obesity status did not drive the clustering.

Next, we sought to define the metabolic distinctions between clusters within the non‑DS controls across obesity classes. We performed t‑tests comparing standardized metabolite levels between cluster 1 and cluster 0 within each obesity class and applied the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate. Ninety‑two metabolites were consistently different (FDR < 0.05) in all four overweight/obesity classes (Supplementary Table 2). These metabolites thus represent a robust signature distinguishing the two clusters, independent of obesity level.

Drawing on this 92‑metabolite signature, we interpreted the metabolic context of the clusters (Tables 1 and 2). Cluster 1 exhibits a pro‑atherogenic, insulin‑resistant profile, marked by global triglyceride enrichment across very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) to high-density lipoprotein (HDL), increased lipoprotein particle counts, triglyceride‑rich and cholesterol‑depleted HDL, and a fatty‑acid pool skewed toward saturated and monounsaturated species with reduced polyunsaturated (Ω‑6) fractions. In contrast, cluster 0 displays a more favorable lipid profile, with lower triglycerides, fewer particles, higher cholesterol ester content, and enrichment in anti‑inflammatory polyunsaturated fatty acids. In the controls, absolute Ω−6 concentrations were higher in cluster 1, whereas the percentage of Ω−6 within the total fatty-acid pool was lower and the Ω−6 to Ω−3 ratio was reduced in all obesity classes. Absolute Ω−3 concentrations showed modest increases in overweight and Class I obesity, but differences were not consistent in Classes II and III, and Ω−3% did not differ significantly.

Discussion

The present study identifies an intrinsic dyslipidemic phenotype in DS with overweight or obesity, characterized by triglyceride-rich, cholesterol-ester–depleted lipoproteins and altered fatty-acid composition. This pattern suggests a state of insulin-resistant lipid metabolism and impaired lipoprotein remodeling in DS, independent of adiposity. The enrichment of DS participants within a distinct, data-driven lipidomic cluster supports the notion that DS confers a unique metabolic signature rather than merely reflecting excess weight. Moreover, the 92-metabolite panel that consistently distinguished the two clusters across all obesity classes in controls indicates that these lipidomic features are robust and biologically grounded. The cluster with a more favorable lipidomic profile was marked by lower triglyceride and particle concentrations, higher cholesterol-ester content, and enrichment in anti-inflammatory polyunsaturated fatty acids23. Together, these findings refine our understanding of the DS metabolic landscape, reveal clinically meaningful heterogeneity among overweight and obese children and young adults, and pinpoint specific lipid and fatty-acid pathways that may offer novel therapeutic targets in DS and broader cardiometabolic risk.

DS and the triglyceride‑rich (TG‑rich) lipoprotein phenotype

Nine of twelve DS participants aligned with cluster 1, a distribution unlikely by chance (p = 0.033). Cluster 1 displays marked elevations in triglyceride content across the lipoprotein spectrum, including XXL_VLDL_TG, XS_VLDL_TG, S_VLDL_TG, IDL_TG, LDL_TG, and HDL_TG subclasses, along with increased total triglycerides (Total_TG) and remnant cholesterol (Remnant_C). There is also a broad expansion in particle concentrations, particularly within remnant lipoproteins (IDL_P) and HDL (L_HDL_P, M_HDL_P, S_HDL_P). A distinct inversion in HDL composition is evident, with high triglyceride levels (HDL_TG, L_HDL_TG, M_HDL_TG, S_HDL_TG, XL_HDL_TG) coupled with low cholesterol ester content (L_HDL_CE_pct, M_HDL_CE_pct, S_HDL_CE_pct), indicating a dysfunctional HDL profile skewed toward triglyceride enrichment and cholesterol ester depletion. Fatty acid patterns are similarly disrupted, with elevated saturated (SFA) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), and reduced polyunsaturated fractions, particularly Ω−6 (Omega_6_pct, PUFA_pct, PUFA_by_MUFA). These metabolic shifts mirror features commonly associated with insulin-resistant states24. The apparent discrepancy between Ω−6 and Ω−3 reflects expansion of the total fatty-acid pool in cluster 1 with disproportionate enrichment in saturated and monounsaturated species. Under these conditions, absolute Ω−6 can increase while its percentage declines. By contrast, Ω−3 differences were smaller and not consistent across obesity classes. The Nightingale assay aggregates Ω−3 species rather than resolving EPA and DHA, which may attenuate detection of cardioprotective signals. Future species-resolved lipidomics targeting EPA and DHA will be important to delineate Ω−3 biology in DS.

Altered fatty-acid composition likely contributes to the insulin-resistant, pro-inflammatory phenotype observed in cluster 1. Evidence from human metabolic studies indicates that enrichment in saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, accompanied by depletion of polyunsaturated species, has been associated with impaired HDL remodeling and reduced cholesterol-efflux capacity. In children and adolescents with abdominal obesity, Martin et al. (2024) found that myristic and palmitic acids were significantly elevated and linoleic acid was lower in the obese group compared to controls and that these fatty acids showed significant correlations with reduced cellular cholesterol efflux and lower lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) activity25. Similarly, Davico et al. (2025) observed that plasma fatty-acid profiles characterized by lower EPA and linoleic acid and higher saturated and monounsaturated species correlated with markers of inflammation and dyslipidemia26. Together, these findings align closely with our observation of triglyceride-rich, cholesterol-ester-poor HDL particles in cluster 1 and support the interpretation that fatty-acid imbalance in DS contributes to insulin resistance and dyslipidemia independent of adiposity.

At the molecular level, these alterations may involve interferon-driven suppression of ABCG1 and ABCA1 cholesterol efflux transporters27, hepatic insulin resistance promoting VLDL overproduction28, and putative impaired bile acid - Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling29, all of which are plausibly intensified by gene dosage effects in trisomy 2130.

Obesity‑independent clustering unmasks covert metabolic risk

The 92‑metabolite fingerprint separates individuals independently of BMI class. More than one‑third of overweight controls fall into cluster 1 despite only modest adiposity. Because obesity severity effects were removed by stratified testing, the signature likely reflects intrinsic lipid‑handling programs such as hepatic TG export, cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)‑mediated exchange, and desaturase flux rather than sheer fat mass31. In other words, we reveal a dyslipidemic predisposition that conventional anthropometry would miss, extending the metabolically unhealthy phenotype to the overweight and DS populations.

The integrated signature points to a coherent disruption across lipid pathways. Triglyceride accumulation in VLDL and HDL reflects heightened hepatic TG output and impaired clearance32. Particle number increases further support lipoprotein overproduction33. The HDL lipid core is altered by CETP-driven exchange, producing TG-rich, CE-depleted particles that are less efficient in reverse cholesterol transport34. Enrichment in membrane-associated lipids such as phospholipids, cholines, and sphingomyelins may indicate lipoprotein surface remodeling or altered cellular signaling35. Fatty acid imbalances suggest either dietary skewing or enzymatic dysregulation, favoring a pro-inflammatory lipid profile36. Smaller VLDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles exhibit increased core TG and reduced cholesterol, consistent with CETP activity and the emergence of small, dense LDL phenotypes37. Collectively, these interwoven features define a lipidome dominated by ectopic TG storage, dysfunctional HDL, inflammatory fatty acid composition, and an atherogenic lipoprotein profile.

Translational leverage

The cluster 1 lipid pattern may have direct relevance for children with DS and overweight or obesity, a group at elevated long-term cardiometabolic risk. Although lipid monitoring is recommended in pediatric practice, a nationwide U.S. analysis of electronic medical records encompassing more than 3 million youths aged 9 to 21 years found that only 11.3% had a documented lipid screening test38. Dedicated data on screening prevalence among children with DS are lacking, but given their higher cardiometabolic burden, under-screening in this group is a concern. A recent meta-analysis reported that individuals with DS exhibit less favorable serum lipid concentrations, including lower HDL-cholesterol and higher triglycerides than neurotypical peers39. The lipidomic profile identified in this study could reflect hepatic overproduction of triglycerides, altered CETP-mediated exchange, and impaired HDL remodeling, mechanisms associated with insulin-resistant dyslipidemia but not yet confirmed specifically in DS.

Nightingale 1H-NMR metabolomics represents a standardized and scalable translational research platform, validated in large-scale epidemiologic studies17,18. The UK Biobank study by Julkunen et al. (2023) profiled 118,461 participants and linked 249 NMR biomarkers to over 700 disease outcomes, with replication in more than 30,000 individuals from five Finnish cohorts, confirming the platform’s analytical robustness and translational value40. Although not yet implemented in clinical diagnostics, this technology could eventually be integrated into DS-focused metabolic research and early-risk screening programs as analytic accessibility improves. The present findings suggest that 1H-NMR-derived lipid signatures could provide an important tool for identifying DS individuals who exhibit triglyceride-rich, cholesterol-ester–poor lipoprotein profiles. However, the direct relationship between these lipidomic patterns and cardiometabolic outcomes in DS remains to be established. Repeated measurements to monitor therapeutic response should therefore be considered a hypothetical research framework to be tested in longitudinal cohorts and implemented, if validated, in accordance with pediatric and DS-specific clinical guidelines to ensure feasibility and minimize patient burden.

Limitations and future directions

This work has several constraints that shape the interpretation of its findings. First, the DS cohort is small and drawn from a single center, limiting statistical power for gene‑dosage interaction analyses and for detecting less common lipid patterns. Second, the cross‑sectional design captures only a snapshot of metabolism, so it cannot establish whether the triglyceride‑rich lipidotype precedes, accompanies, or follows clinical complications such as steatosis or insulin resistance. Third, potential confounders such as diet, thyroid status, and sleep disordered breathing were not systematically quantified and may influence the lipid profile. In addition, Tanner stage was not systematically recorded for participants. Because puberty can affect lipid and insulin-resistance indices, unmeasured variation in pubertal status may have contributed to interindividual metabolic differences. However, the age range (11–21 years) corresponds largely to mid- to late-pubertal stages, which may reduce, but does not eliminate, this potential confounding effect. Future research should enroll larger, multi‑center DS cohorts and collect serial samples from childhood through adulthood to define the natural history of the cluster 1 phenotype. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether individuals transition between clusters, whether such transitions parallel lifestyle changes or pharmacotherapy, and how strongly cluster 1 membership predicts insulin‑resistance-related outcomes in DS, e.g. non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular events, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Data availability

The primary data generated in this study are available through the International HundredK+ Cohorts Consortium (IHCC). Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author, Dr. Hakon Hakonarson, by request.

References

Coppedè, F. Risk factors for down syndrome. Arch. Toxicol. 90, 2917–2929 (2016).

Torr, J., Strydom, A., Patti, P. & Jokinen, N. Aging in down syndrome: morbidity and mortality. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 7, 70–81 (2010).

Magge, S. N., Zemel, B. S., Pipan, M. E., Gidding, S. S. & Kelly, A. Cardiometabolic risk and body composition in youth with down syndrome. Pediatrics 144(2), e20190137 (2019).

Bertapelli, F., Pitetti, K., Agiovlasitis, S. & Guerra-Junior, G. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with down syndrome—prevalence, determinants, consequences, and interventions: A literature review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 57, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2016.06.018 (2016).

Valentini, D. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in italian children with down syndrome: prevalence and correlation with obesity-related features. J. Pediatrics 189, 92–97 (2017).

Parra, P., Costa, R., de Asúa, D. R., Moldenhauer, F. & Suárez, C. Atherosclerotic surrogate markers in adults with down syndrome: A Case-Control study. J. Clin. Hypertens. 19, 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12890 (2017).

Aslam, A. A. et al. Diabetes and obesity in down syndrome across the lifespan: A retrospective cohort study using UK electronic health records. Diabetes Care. 45, 2892–2899 (2022).

Head, E., Lott, T. & Wilcock, I. M. A Lemere, C. Aging in down syndrome and the development of alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13, 18–29 (2016).

Moreau, M. et al. Metabolic diseases and Down Syndrome: How Are They Linked Together?. Biomed 9(2), 2021 (2021).

Tansley, G. H. et al. The cholesterol transporter ABCG1 modulates the subcellular distribution and proteolytic processing of β-amyloid precursor protein. J. Lipid Res. 48, 1022–1034 (2007).

Hardin, A. P. et al. Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics 140(3), e20172151 (2017).

Balasundaram, P. & Krishna, S. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025 (StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025).

Weir, C. B. & Jan, A. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025 (StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025).

Zemel, B. S. et al. Growth charts for children with down syndrome in the united States. Pediatrics 136, e1204–1211. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1652 (2015).

Qu, H. Q., Connolly, J. J., Mentch, F., Glessner, J. & Hakonarson, H. Metabolic remodeling and the modulatory role of vitamin d deficiency in african american children and adolescents with obesity. Metabolites 15(6), 406 (2025).

Nightingale. Biomarker quantification version 2020.

Soininen, P., Kangas, A. J., Würtz, P., Suna, T. & Ala-Korpela, M. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in cardiovascular epidemiology and genetics. Circulation: Cardiovasc. Genet. 8, 192–206 (2015).

Würtz, P. et al. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in large-scale epidemiology: a primer on-omic technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1084–1096 (2017).

Core Team, R. R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2013).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F. L. Jr The python language reference. Python Software Foundation: Wilmington, DE, USA (2014).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Lee, L. C., Liong, C. Y. & Jemain, A. A. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for classification of high-dimensional (HD) data: a review of contemporary practice strategies and knowledge gaps. Analyst 143, 3526–3539 (2018).

Quehenberger, O. et al. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 51, 3299–3305 (2010).

Tonks, K. T. et al. Skeletal muscle and plasma lipidomic signatures of insulin resistance and overweight/obesity in humans. Obesity 24, 908–916 (2016).

Martin, M. et al. Impaired reverse cholesterol transport is associated with changes in fatty acid profile in children and adolescents with abdominal obesity. J. Nutr. 154, 12–25 (2024).

Davico, B. et al. Fatty acids in childhood obesity: A link between Nutrition, metabolic alterations and cardiovascular risk. J. Lipid Atherosclerosis. 14, 200 (2025).

Sánchez-Aguilera, P. et al. Role of ABCA1 on membrane cholesterol content, insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake in adult skeletal muscle fibers from mice. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell. Biology Lipids. 1863, 1469–1477 (2018).

Rauschert, S. et al. Lipidomics reveals associations of phospholipids with obesity and insulin resistance in young adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 101, 871–879 (2016).

Chiang, J. Y. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 3, 1191 (2013).

Hetman, M. et al. Predisposition to atherosclerosis in children and adults with trisomy 21: biochemical and metabolomic studies. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metabolism. 29, 143–155 (2023).

Lara-Castro, C. & Garvey, W. T. Intracellular lipid accumulation in liver and muscle and the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 37, 841–856 (2008).

Alves-Bezerra, M. & Cohen, D. E. Triglyceride metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 8, 1–22 (2018).

Adiels, M. et al. Overproduction of large VLDL particles is driven by increased liver fat content in man. Diabetologia 49, 755–765 (2006).

Morton, R. E., Mihna, D. & Liu, Y. The lipid substrate preference of CETP controls the biochemical properties of HDL in fat/cholesterol-fed hamsters. Journal Lipid Research 62 (2021).

Harayama, T. & Riezman, H. Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 281–296 (2018).

Ruiz-Núñez, B., Pruimboom, L., Dijck-Brouwer, D. J. & Muskiet, F. A. Lifestyle and nutritional imbalances associated with Western diseases: causes and consequences of chronic systemic low-grade inflammation in an evolutionary context. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24, 1183–1201 (2013).

Freedman, D. S., Bowman, B. A., Otvos, J. D., Srinivasan, S. R. & Berenson, G. S. Levels and correlates of LDL and VLDL particle sizes among children: the Bogalusa heart study. Atherosclerosis 152, 441–449 (2000).

Thompson-Paul, A. M. et al. Pediatric lipid screening prevalence using nationwide electronic medical records. JAMA Netw. Open. 7, e2421724. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.21724 (2024).

Gastelum Guerrero, C. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of serum lipid concentrations in people with down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 68, 553–563 (2024).

Julkunen, H. et al. Atlas of plasma NMR biomarkers for health and disease in 118,461 individuals from the UK biobank. Nat. Commun. 14, 604 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their participation in the study. We thank the staff at Nightingale for their services.

Funding

The study was supported by: The International Hundred Thousand Plus Cohort Consortium (IHCC); CHOP funding: Institutional Development Funds from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to the Center for Applied Genomics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Endowed Chair in Genomic Research (HH). Grant/award number: Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H., and H.Q.; literature search, H.Q.; Figures and Tables, H.Q.; data analysis, H.Q.; data interpretation, H.Q., J.J.C., G.E., F.M., J.G., and H.H.; original draft writing, H.Q. and H.H.; review and revision, H.Q., J.J.C., and H.H.; supervision, H.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the U.S. Common Rule (45 CFR 46), and all applicable institutional guidelines for pediatric and vulnerable populations. Human participants and personal information are all encrypted to ensure no PHI are included and study participants are de-identified. All human subjects or their proxies provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have provided consent for publication of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, HQ., Connolly, J.J., Eister, G. et al. Pro‑inflammatory insulin‑resistant lipid phenotype in down syndrome identified by 1H‑NMR metabolomics in obesity-matched African‑American children and young adults. Sci Rep 15, 42039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26217-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26217-4