Abstract

Fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology is widely used in the areas of rapid prototyping, education, automobile and health care. However, the disadvantages of high porosity, low surface quality, and significant anisotropic mechanical properties hinder the applications in high-demand fields. In this paper, numerical model and experimental tests are combined to study the effects of layer thickness and extrusion ratio on the printing quality and mechanical properties of FDM structures. The computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and volume of fluid (VOF) method are adopted to investigate the flow behavior of melt and the cross-section of strand. The porosity characteristics, surface roughness and anisotropic mechanical properties of printed part are researched. The results show that, when the layer thickness is less than the diameter of nozzle, the squeezing of nozzle bottom face causes the melt climbing at the rear side of nozzle, which forms the bulges at the top corners of strand. Lower layer thickness helps to decrease the porosity and surface roughness. The proper increment of extrusion ratio can effectively reduce the porosity and improve the mechanical properties of the structures, yet large extrusion ratio may cause excessive squeezing of strand melt which will worsen the surface roughness and mechanical properties. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of FDM technology and provides guidance for the process optimization and structure design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing technology can realize personalized manufacturing of complex structures, performs greater freedom in product design stage and lower cost in the development stage. The materials used in additive manufacturing range from ceramics, metals, polymers, composites and biomaterials, which possesses great material diversity1,2. Based on novel material design method, advanced materials such as metamaterials and smart materials can be manufactured3,4. Among various additive manufacturing methods, fused deposition modeling (FDM) has been increasingly used in recent years in the fields of rapid prototyping, healthcare, education, energy storage and automobile for the advantages of low cost and open communities5,6,7. The main materials used in FDM technology include polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), thermoplastic urethane (TPU), polyamide (PA), etc. By mixing metal particles inside the thermoplastic material and combining with sintering technology, metal structural parts can be manufactured in this low-cost way8. Adding glass fiber or carbon fiber into the filament, the stiffness and strength of printed part can be improved greatly9,10,11. Despite the aforementioned advantages, the widely existed porosities, poor surface condition and significant anisotropy property limit the application of FDM technology in many fields12. Therefore, the research on influencing factors of printing quality and mechanical properties of FDM structures is of great importance.

In FDM process thermoplastic material is melted in the nozzle and extruded onto the printing platform, where they are stacked stand by strand and layer by layer to create structural parts. As the smallest building unit, the morphology of single strand plays an important role in the formation of pores and interfaces between adjacent strands and layers13,14,15,16. The characteristic of strand is closely related with the flow and solidification behavior of the melt, which includes the flow inside the nozzle as well as the flow outside the nozzle. Inside the nozzle, due to the continuous feeding of low-temperature thermoplastic filaments, the temperature of melt in the region close to the inner wall of the nozzle is higher, which is closer to the setting temperature, while the temperature in the central region inside the nozzle is lower. This low-temperature region is elongated when the feeding rate increases, which exhibits a large temperature gradient17,18. When the setting temperature raises this temperature gradient decreases19. In order to measure the melt pressure inside the nozzle, Anderegg et al.. developed a novel nozzle that monitors temperature and pressure fluctuations by means of a built-in pressure transducer and thermocouple20. Increasing the extrusion force can improve the extrusion rate of the melt, yet when the extrusion rate is too large, the solid plastic filament cannot be completely melted and will block the nozzle, which in turn leads to the flexing of the filament or the slipping of the feeder wheel. Luo et al. constructed the governing equations for the temperature and pressure distributions of the melt inside the nozzle, and investigated the factors of the material rheological properties and the nozzle size that affect the maximum filament feeding rate. The approximate linear relationship between the maximum extrusion force and the extrusion rate was clarified21. Serdeczny et al. constructed a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of the extrusion process, and the results show that a longer nozzle would make the extruded melt obtain a temperature closer to the setting temperature and the oscillation of the extrusion force occurs when the extrusion rate exceeds the critical value22. After the melt is extruded from the nozzle, the mechanical energy stored inside the melt releases and die swell occurs, which can increase the melt diameter by up to 30% 23,24. In addition, when the extrusion rate is too large, the melt flow will be disturbed and fracture instability and sharkskin phenomenon will occur17,25. The aforementioned studies mainly focus on the free state of the melt after it is extruded out of the nozzle, however, in real printing the flow behavior is also affected by the limited space between the bottom of the nozzle and the printing platform or the strand in the previous layer.

In order to study the morphological characteristics of the printed strand, Comminal et al. constructed a CFD model of the melt extrusion process, and investigated the effects of extrusion rate and nozzle height on the cross-sectional morphology of the single strand26. Based on the results of the single strand simulation, Serdeczny et al. further analyzed the multi-strand structures and evaluated the effects of interlayer height, strand-to-strand distance and arrangement on the porosity, which showed that lower interlayer height and staggered arrangement could reduce porosity and increase the bonding effect between strands13.The above researches have constructed the numerical simulation method to analyze the morphology of a strand, and made suggestions to optimize the porosity and interfacial properties. However, the relations between the strand morphology and pores in micro scale and surface roughness and anisotropic mechanical properties in macro scale have rarely been investigated systematically.

In this paper, a numerical model based on CFD and VOF (volume of fluid) method is established to study the flow behavior of melt during FDM process. The influences of layer thickness and extrusion ratio on the single strand morphology and deposition pressure are investigated. Based on the characteristics obtained in micro scale, the surface roughness and anisotropic mechanical properties of multi-strand part are furtherly investigated. This research work helps to deeply understand the effect of melt flow behavior on the properties of printed part and optimize the selections of printing parameters.

Numerical model

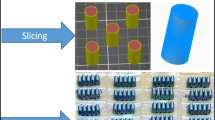

The design and manufacturing process of FDM technology is shown in Fig. 1(a). The STL format file is exported from 3D modeling software, and the critical parameters such as printing speed, printing temperature, layer thickness, etc. are set in the slicing software, then the G-code format file is exported and sent to the 3D printer to carry out the printing process. Figure 1(b) illustrates the process of material extrusion in FDM, where the thermoplastic is heated, melted and extruded out of the nozzle by the piston action of filament. With the movement of nozzle, the strand is built on the printing platform. When the extrusion state is stable, the geometry of strand satisfies the following equation:

where Df is the diameter of the filament, u is the feeding speed of the filament, d is the nozzle diameter, U is the inlet velocity of melt at nozzle tip, A is the cross-sectional area of strand, V is the moving speed of nozzle. In many slicing software, a rectangular cross-section is assumed, then:

where h is the layer thickness setting, w is the strand width setting, and γ is the flow ratio used to adjust the extrusion amount of melt. Once h, w, γ and V are given, the feeding speed u can be calculated according to Eq. (1), by which the extrusion length of filament used in G-code can be obtained.

Figure 2(a) illustrates the CFD model established in this paper. The taper shape of nozzle is simplified to a hollow cylinder. The velocity of inlet is assumed to be a homogeneous value of U. The modelling of melt is consistent with the setting of Comminal et al.26, which assumes that the melt is a Newtonian fluid and incompressible. Navier-Stokes equations used to describe the conservation of mass and momentum of melt are as follows:

where u is the velocity vector, ρ is the melt density, p is the melt pressure, fs represents the surface tension force, and g is the gravitational acceleration. Symmetric boundary condition is adopted, and the printing platform moves with the velocity of V. The model construction and calculation are implemented in ANSYS Fluent software, and the structured meshing is illustrated in Fig. 2(b). The global element seed size is 0.02 mm, and the time-step is set with 0.001 s. The VOF method is implemented to capture the interface between melt and air.

The printing parameters studied in this paper include the normalized extrusion ratio U/V and the layer thickness h. All the parameters used in the numerical model are listed in Table 1.

Experimental methods

The filament used in the experiment is PLA from Flashforge company with the diameter of 1.75 mm. The printer used for the experiments is shown in Fig. 3, which is a high-rigidity gantry structure with stepper motors to drive the movement of the print head. The control system is Makerbase Gens V1.2 hardware with Marlin 2.0 firmware. G-code is sent to the printer by Repetier-Host software to realize the printing work. The filament extrusion accuracy was corrected by marking the position on the thermoplastic filament, and setting a fixed extrusion length of 100 mm by sending G-code ‘G1 E100’, then the position of marked point was measured and actual extrusion length was obtained. The number of motor pulses in EEPROM was modified until the extrusion length error is less than 3%.

The experimental specimens are divided into three types: single strand specimen, multi-strand specimen and tensile test specimen, which are shown in Fig. 4. The single strand specimens are used to study the cross-section shape (Fig. 4(a)), the G-code of which is listed in Appendix A. The multi-strand specimens are used to study the porosity and surface roughness (Fig. 4(b)), the dimension of which is 30 × 4 × 2 mm3. The hatch distance of multi-strand specimen and tensile test specimen is same with the diameter of nozzle, which is 0.4 mm. The tensile test specimens with X/Y/Z-directions are adopted to study the anisotropic mechanical properties as shown in Fig. 4(c)-(e)). In the study of each direction, 5 samples were adopted to carry out the statistical analysis. The dimensions of gauge regions in X/Y-direction specimens are 2 × 4 × 12 mm3. The dimensions of gauge regions in Z-direction specimens are 3 × 10 × 12 mm3.

The printing parameters of specimens are listed in Table 2. The filaments are dried at 55℃ for 12 h before printing process to remove the moisture. The printing temperature is set as 200 ℃, and no cooling fan is used for the printed part. After the completion of the printing, the stable part of the single strand was cut, polished and then observed by optical microscope. The cross-sections of multi-strand specimens were observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM), and the surface morphology was measured by 3D laser profilometer. Tensile tests of specimens in different directions were carried out in universal material testing machine according to ASTM D638. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to study the crystallinities of different specimens.

Results and discussion

Melt flow behavior

The velocity streamlines of melt at different U/V are shown in Fig. 5. Due to the restricted space under the nozzle, the melt flow laterally from the center area of nozzle. At U/V = 0.5, the range of lateral flow is small and the width of strand is narrow. When U/V increases to1.0, more melt is extruded and causes a larger range of lateral flow, making the increment of strand width.

The melt flow behavior during FDM process are illustrated in Fig. 6. When the melt flows out of the bottom region of the nozzle, the melt pressure suddenly decreases and the melt climbing behavior occurs along the rear side of the nozzle wall (Fig. 6(a) and (b)), and fall back occurs when the melt moves away from the bottom region of the nozzle. Figure 6(c) shows a top view of the melt morphology, which can be divided into two regions: transition region and stable region. The transition region is under the nozzle, which includes the behavior of lateral flow, melt climb and falling. The stable region is behind the transition region, where the melt flow is in a stable state and the streamlines are parallel with each other. Figure 6(d) shows the pressure field of printing platform when U/V = 1.0. The pressure is higher in the center area below the nozzle, where the melt flow direction in this area changes from vertical to backward, forming a larger extrusion pressure. When the melt flows outside the bottom of nozzle the pressure decreases significantly, which causes a low-pressure area related with the melt climbing behavior. The pressure below the nozzle is very important to the formation of strong interface between adjacent layers. High pressure is conducive to the fusion and entanglement of the molecular chains in different layers to increase the interlayer strength. However, if the pressure is too high the deformation of the strand may occur and the printing quality declines.

Influencing factors of strand morphology

Layer thickness

The effect of layer thickness h on the strand morphology is shown in Fig. 7. When h is 0.4 mm, the bottom face of the nozzle performs little contact with the melt, and the center of strand is higher than two sides. When h is 0.3 mm, the bottom of the nozzle has a squeezing effect on the melt, and the melt climbing behavior occurs, which results in bulges on both sides of the strand cross-section. When h is 0.2 mm, the bottom of the nozzle has a stronger squeezing effect on the melt, the melt climbing behavior is more obvious and the height of the bulge is higher.

The numerical and experimental strand dimensions with different layer thickness h are illustrated in Fig. 8. In the parameter setting of many slicing software, it is assumed that the cross-section of strand is rectangular and the width is set to be same with the nozzle diameter (0.4 mm). However, both the numerical and the experimental result show that the two sides of the strand present rounded features, the width of the strand is larger than the width setting of 0.4 mm in the slicing software, and the height of the strand is lower than the layer thickness setting under each condition.

Normalized extrusion ratio

The effect of normalized extrusion ratio U/V on strand morphology is shown in Fig. 9. In the numerical results, when U/V increases from 0.5 to 1.0, the lateral flow of the melt under the nozzle enhances, and the width of the strand increases respectively. The numerical and experimental strand dimensions with different U/V are shown in Fig. 10. With the increment of U/V, the strand width and height grow both in the numerical and experimental results. In addition, due to the increasing melt climbing behavior the bulge height also grows. For the lacking of volume shrinkage in the numerical model, the predicted strand widths and bulge heights are greater than the experimental results.

The pressure field under different conditions

Figure 11 illustrates the pressure field of platform under different layer thicknesses h and normalized extrusion ratio U/V. In the numerical results, the gauge pressure is adopted and negative pressure appears. To calculate the absolute pressure the atmospheric pressure value of 101.3 kPa needs to be added.

As shown in Fig. 11(a)-(c), when h is 0.4 and 0.3 mm, the maximum pressure locates in the front of nozzle zone. The large gap between nozzle bottom face and platform provides sufficient space for the melt to flow freely. With the moving of platform, the melt accumulates in the front area and makes the pressure larger. When h is 0.2 mm, large amount of melt accumulates in the center of the nozzle and significant lateral flow occurs, which causes higher pressure in the center of the nozzle zone.

As shown in Fig. 11(d)-(f), with the increment of U/V the pressure of the printing platform under the nozzle also increases respectively, and the maximum pressure increases from 184.0 kPa to 619.3 kPa when the U/V increases from 0.5 to 1.0, which is conducive to the fusion and entanglement of the molecular chains between adjacent layers and the improvement of the interlayer strength. However, excessive pressure may cause the failure of filament extrusion and affect the printing precision.

Cross-section of printed part

Figures 12 and 13 show the cross-sectional morphologies and porosities of multi-strand specimens with different layer thickness h and flow ratio γ. Here, the flow ratio γ is used instead of normalized extrusion ratio U/V for the convenience of adopted in the slicing software. In most slicing software the inlet velocity U cannot be directly inputted through the user interface, while the flow ratio γ can be adjusted by the user. According to Eqs. (1) and (2), the relationship of γ and U/V are as follows:

For the reason that the actual strand width is larger than the hypothetical rectangle shape, one side of the strand melt covers on the adjacent strand in each situation. At h = 0.2 mm and γ = 100%, the lower layer is able to form an effective support to the higher layer and the bulging regions help to fill the pores, causing the porosity as small as 1.00 ± 0.13%. At h = 0.3 mm and γ = 100%, the filling effect of bulges decreases, and the pores size becomes larger. The porosity at this layer thickness is 3.83 ± 0.81%. At h = 0.4 mm and γ = 100%, the pore sizes are still quite large, yet the number of pores decreases greatly, which makes the porosity reduce to 3.44 ± 0.79%.

As shown in Fig. 12(d)-(f), with the increment of γ excessive squeezing occurs between different strands, which damages the regularity of the strands in the printed part. The porosity of specimens with different flow ratios are shown in Fig. 13(b). The increasing of γ from 100% to 105% helps to decreases the porosity from 1.00 ± 0.13% to 0.59 ± 0.12%, and the reduction is 41%. However, with the increment of γ to 115%, the porosity increases slightly and then decreases.

Surface morphology of printed part

Figure 14 shows the surface morphology of the printed parts with different layer thicknesses h and flow ratio γ. From the 3D contours and the top view of the surface in Fig. 14(a)-(b), it can be found that each strand covers on the adjacent strand, which causes the periodic fluctuations of the part surface. Figure 14(c)-(d) show the comparison of the surface contours and surface roughness Ra of parts with different h. In the research of Ra, 5 detection lines are used in 5 specimens to carry out the statistical analysis. When h reduces from 0.4 mm to 0.2 mm, the grooves between the strands gradually decrease and the surface quality performs improvement. The surface roughness Ra changes from 16.86 ± 0.56 μm to 7.82 ± 1.01 μm, and the decline has reaches a magnitude of 46.38%.

(e)-(f) show the surface contours and surface roughness Ra of parts with different γ. When γ increases from 100% to 110%, the surface roughness decreases due to the filling of melt into the pores between the strands, and Ra decreases from 7.82 ± 1.01 μm to 6.88 ± 0.15 μm. However, when γ reaches 115%, the excessive melt causes excessive squeezing and significant increment of surface roughness.

Figure 14 Surface morphology of printed part with different layer thicknesses h and flow ratios γ: (a) laser reconstructed 3D morphology, h = 0.2 mm (γ = 100%); (b) surface morphology image, h = 0.2 mm (γ = 100%); (c) surface contour lines of printed parts with different h (γ = 100%); (d) surface roughness of printed parts with different h (γ = 100%); (e) surface contour lines of printed parts with different γ (h = 0.2 mm); (f) surface roughness of printed parts with different γ (h = 0.2 mm).

Mechanical properties of specimens

Mechanical properties of specimens in different printing directions with different layer thicknesses h and flow ratios γ are shown in Fig. 15. Engineering stress and strain are adopted in the data analysis. From the stress-strain curves in Fig. 15(a), it can be found that when h is 0.2 and 0.3 mm, the X-direction specimen exhibits large plastic deformation before losing their load-bearing capacity. The fracture morphologies are shown in Fig. 16(a) and Fig. 16(b) at Appendix B. The specimens with h of 0.4 mm suffer brittle fracture after the load reaches their maximum value, whose fracture morphology is shown in Fig. 16(c) at Appendix B. The tensile strengths of X-direction specimen are 52.2 ± 0.7 MPa at h = 0.2 mm, 46.6 ± 1.5 MPa at h = 0.3 mm, and 51.9 ± 2.4 MPa at h = 0.4 mm. This phenomenon may be caused by the combination of porosity and crystallinity. The specimen at h = 0.3 mm processes the largest porosity of 3.83 ± 0.81%, which causes the reduction of load-bearing area during the tensile test. In addition, according to the DSC tests, the crystallinity of specimens with h of 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 mm are 20.72%, 19.76% and 20.97% respectively, as shown in Fig. 17; Table 3 at Appendix B. Lower crystallinity causes the decrement of tensile strength of specimens. The difference of crystallinities with different layer thicknesses may causes by following reasons: smaller layer thickness performs fast cooling, which inhibits grain formation and results in lower crystallinity, but the latter layer will reheat the former layer which may result in secondary crystallization and thus increase the crystallinity. When the layer thickness changes, the competition between inhibiting and promoting of crystallization changes. With the layer thickness of 0.2 mm, thermal cycling has a stronger effect on promoting crystallization. With the layer thickness of 0.4 mm, the heat dissipation of strand is weaker and the crystallinity is higher. In contrast, with the layer height of 0.3 mm, both of the above effects are weak, resulting in a lower crystallinity.

As shown in Fig. 15(b), the plastic deformability of the specimens in the X-direction decreases with the increase of γ. When the γ is increased to 115%, the specimen shows typical brittle fracture characteristics. The tensile strengths of the X-direction specimens increase with γ. This improvement can be attributed to the reduction in internal porosity at higher γ, which results in a greater volume of material being available to carry the load.

As shown in Fig. 15(c) and (g), the Y-direction specimen has the maximum tensile strength of 29.35 ± 0.64 MPa when h = 0.4 mm. This may be attributed to that the fusion area between two adjacent strands is larger with higher layer thickness, making it easier to form interfaces with higher strength. At h = 0.2 mm the tensile strength of Y-direction specimen decreases by 32.98% relative to h = 0.4 mm.

Mechanical properties of specimens in different printing directions with different layer thicknesses h and flow ratios γ: (a) Stress-strain curves of X-direction specimens with different h (γ = 100%); (b) Stress-strain curves of X-direction specimens with different γ (h = 0.2 mm); (c) Stress-strain curves of Y-direction specimens with different h (γ = 100%); (d) Stress-strain curves of Y-direction specimens with different γ (h = 0.2 mm); (e) Stress-strain curves of Z-direction specimens with different h (γ = 100%); (f) Stress-strain curves of Z-direction specimens with different γ (h = 0.2 mm); (g) Tensile strengths specimens in different printing directions with different h (γ = 100%); (h) Tensile strengths of specimens in different printing directions with different γ (h = 0.2 mm).

As shown in Fig. 15(d) and (g), when γ increases from 100% to 115%, the tensile strength of Y-specimen increases by 127.4%, however, the plastic deformation significantly decreases. The stress-strain curves of Z-direction specimens with different h are shown in Fig. 15(e). When the h increases, the contact area between the latter layer and the former layer decreases, and the contact pressure between adjacent layers decreases, which significantly reduces the tensile strength in the Z-direction. When h = 0.2 mm, the tensile strength of Z-direction specimens is 58.5% greater than h = 0.4 mm. Figure 15(f) shows the mechanical properties of Z-direction specimen with the change of γ. The tensile properties of Z-direction specimens are not only affected by the fusion area between adjacent layers, but also affected by the printing quality of entire specimen. When γ = 105%, the Z-direction specimens have the maximum tensile strengths of 39.31 ± 1.92 MPa.

Conclusions

In this paper, the flow behavior and cross-sectional morphology of the melt in FDM process with different layer thicknesses and flow ratios are investigated. The cross-section shape, surface roughness and mechanical properties of the specimens in different printing directions are analyzed. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) With the nozzle diameter of 0.4 mm, when the layer thickness is 0.4 mm, the cross-sectional morphology of strand is high in the middle and low at both sides. When the layer thickness is lower than 0.3 mm, the melt flows laterally due to the squeezing of nozzle bottom face, and the melt climbing occurs at two sides behind the nozzle, forming a cross-section shape which is low in the middle and high at both sides.

(2) With the flow ratio of 100%, the reduction of layer thickness from 0.4 mm to 0.2 mm is capable to decrease the porosity by 70.93% and surface roughness Ra by 53.61%. With the layer thickness of 0.2 mm, the increasing of flow ratio from 100% to 105% can reduce the porosity by 41%. The setting of flow ratio to 110% obtains the lowest surface roughness, however, if the flow ratio is greater than 110%, the excessive extrusion of melt will result in the deterioration of the printing quality and significant increase in surface roughness.

(3) X-direction specimens have larger tensile strengths at 0.2 mm and 0.4 mm layer thicknesses due to the low porosity and crystallinity. As the layer thickness increases, the fracture characteristics of the X-direction specimens change from ductile failure to brittle failure. The tensile strength of Y-direction specimen increases with the growth of layer thickness, which is likely attributable to the increase in the bonding area between adjacent strands in the same layer. The bonding area and pressure between adjacent layers in Z-direction decreases with the growth of layer thickness, resulting in the reduction of Z-direction tensile strength. (4) The increase of flow ratio can reduce the porosity and enlarge the area of bonding interface between strands and layers. With the growth of flow ratio, the tensile strengths in X-direction and Y-direction increase. However, when the flow ratio exceeds 105%, excessive squeezing of melt between the strands and layers occurs, which increases the surface roughness and leads to the decline of mechanical properties in Z-direction.

Appendix B

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Garzon-Hernandez, S., Garcia-Gonzalez, D., Jérusalem, A. & Arias, A. Design of FDM 3D printed polymers: An experimental-modelling methodology for the prediction of mechanical properties. Mater. Design 188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108414 (2020).

Xiang, J. et al. Effects of undulating printing paths on axial compressive behaviors of 3D-printed continuous fiber-reinforced multi-cell thin-walled structure. Eng. Struct. 325, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.119353 (2025).

Li, H. et al. One-Degree-of-Freedom mechanical metamaterials with arbitrary prescribability and rapid reprogrammability of Force–Displacement curves. 8, 07-15, (2025). https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0715

Jin, F. et al. 4D printing of continuous carbon fiber reinforced composites with magneto-/electro-induced shape memory effect. Chem. Eng. J. 508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.160450 (2025).

Yao, Y., Zhang, Y., Aburaia, M. & Lackner, M. 3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform. Appl. Sci. 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114825 (2021).

Lou, X., Zhao, L., Gao, Y. & Nan, X. 3D-Printed Electrode/Electrolyte architectures for High-Performance Lithium-Ion batteries: Mechanisms, Materials, and challenges. ACS Omega. 10, 28630–28642. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.5c02247 (2025).

He, T. et al. Self-Healing SA@Borax binder for in situ tuning of the solid electrolyte interfaces for silicon anodes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 13, 4093–4107. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c10154 (2025).

Jacob, J., Pejak Simunec, D., Kandjani, A. E. Z., Trinchi, A. & Sola, A. A Review of Fused Filament Fabrication of Metal Parts (Metal FFF): Current Developments and Future Challenges. Technologies 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies12120267 (2024).

Lou, X. et al. Dual-matrix interface strength of 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced composites: Quantitative assessment methodology and critical influencing factors. Additive Manuf. Lett. 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addlet.2025.100303 (2025).

Xiang, J. et al. 3D printed continuous fiber-reinforced composites with high fiber bundle shape uniformity, mechanical performance consistency, and fiber content. Compos. Commun. 58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2025.102499 (2025).

Shang, J. et al. Impact resistance of biomimetic gradient sinusoidal composites by 3D printing: Tunable structural stiffness and damage tolerance. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.112016 (2025).

Gao, X. et al. Fused filament fabrication of polymer materials: A review of interlayer bond. Additive Manuf. 37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101658 (2021).

Serdeczny, M. P., Comminal, R., Pedersen, D. B. & Spangenberg, J. Numerical simulations of the mesostructure formation in material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 28, 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.05.024 (2019).

Hebda, M., McIlroy, C., Whiteside, B., Caton-Rose, F. & Coates, P. A method for predicting geometric characteristics of polymer deposition during fused-filament-fabrication. Additive Manuf. 27, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.02.013 (2019).

Comminal, R., Serdeczny, M. P., Pedersen, D. B. & Spangenberg, J. Motion planning and numerical simulation of material deposition at corners in extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.06.005 (2019).

Xia, H. X., Lu, J. C., Dabiri, S. & Tryggvason, G. Fully resolved numerical simulations of fused deposition modeling. Part I: fluid flow. Rapid Prototyp. J. 24, 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/rpj-12-2016-0217 (2018).

Serdeczny, M. P., Comminal, R., Mollah, M. T., Pedersen, D. B. & Spangenberg, J. Numerical modeling of the polymer flow through the hot-end in filament-based material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101454 (2020).

Peng, F., Vogt, B. D. & Cakmak, M. Complex flow and temperature history during melt extrusion in material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 22, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.05.015 (2018).

Luo, C., Wang, X., Migler, K. B. & Seppala, J. E. Upper bound of feed rates in thermoplastic material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.101019 (2020).

Anderegg, D. A. et al. In-situ monitoring of polymer flow temperature and pressure in extrusion based additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 26, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.01.002 (2019).

Luo, C., Wang, X., Migler, K. B. & Seppala, J. E. Effects of feed rates on temperature profiles and feed forces in material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101361 (2020).

Serdeczny, M. P., Comminal, R., Pedersen, D. B. & Spangenberg, J. Experimental and analytical study of the polymer melt flow through the hot-end in material extrusion additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.100997 (2020).

Mackay, M. E. The importance of rheological behavior in the additive manufacturing technique material extrusion. J. Rheol. 62, 1549–1561. https://doi.org/10.1122/1.5037687 (2018).

Go, J., Schiffres, S. N., Stevens, A. G. & Hart, A. J. Rate limits of additive manufacturing by fused filament fabrication and guidelines for high-throughput system design. Additive Manuf. 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2017.03.007 (2017).

Bakrani Balani, S., Chabert, F., Nassiet, V. & Cantarel, A. Influence of printing parameters on the stability of deposited beads in fused filament fabrication of poly(lactic) acid. Additive Manuf. 25, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.10.012 (2019).

Comminal, R., Serdeczny, M. P., Pedersen, D. B. & Spangenberg, J. Numerical modeling of the strand deposition flow in extrusion-based additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf. 20, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2017.12.013 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, North Minzu University (2021KYQD08); Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia (2024AAC03159); National Natural Science Foundation of China (52265017); Ningxia Science and Technology Innovation Team (2024CXTD001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaofei Lou: data analysis, original draft preparation, funding.Xin’an Tang and Lei Dong: experiment execution, data analysis.Tao Zhao and Fuwei Wang: formal analysis, validation.Li Zhao and Teng Zhang: validation, supervision, funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, X., Tang, X., Dong, L. et al. Influence of layer thickness and extrusion ratio on strand morphology, porosity, surface roughness, and anisotropic mechanical properties in FDM. Sci Rep 15, 42351 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26253-0