Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the dose-dependent protective effects of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract (CBPE) against the phytotoxic and genotoxic impacts of the insect growth regulator Triflumuron (TFM), using the Allium cepa assay. A comprehensive evaluation was performed by analyzing physio-morphological (germination rate, root elongation, biomass gain, chlorophyll a and b levels), cytogenetic (mitotic index, micronucleus formation, chromosomal abnormalities), biochemical (superoxide dismutase, catalase, malondialdehyde, and proline levels), and molecular endpoints. The phytochemical profile of C. bursa-pastoris was characterized through LC-MS/MS analysis to determine the bioactive phenolic constituents. Allium bulbs were exposed to 20 µg/L TFM and co-treated with two concentrations of CBPE (45 and 90 µg/mL). The results demonstrated that TFM exposure significantly inhibited germination and root growth, reduced mitotic activity (by 6.57%), and induced notable oxidative and genotoxic stress. However, CBPE co-treatment led to considerable recovery in all measured parameters, with the mitotic index increasing to 7.05%–7.55%. TFM exposure markedly increased micronucleus frequency, whereas co-treatment with CBPE led to a dose-dependent reduction in MN frequency, ranging from 15.88% to 35.7%. CBPE demonstrated a strong protective effect against TFM-induced growth suppression, genotoxicity, oxidative stress, and structural deterioration in meristem cells in A. cepa. This protective property is associated with the phenolic compounds contained in CBPE. The most abundant phenolic compound in the extract was p-coumaric acid. The findings provide compelling evidence that C. bursa-pastoris extract mitigates TFM-induced cellular and biochemical disruptions by modulating oxidative stress and preserving genomic integrity. This is the first comprehensive demonstration of plant-based mitigation of TFM phytotoxicity, supporting sustainable remediation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of insecticide residues in food, water, air, and soil, as well as their detrimental effects on non-target organisms, has raised considerable concern. It is evident that these compounds pose a greater risk to human health, both in the context of direct exposure and indirect exposure. It is estimated that over 26 million individuals suffer from pesticide poisoning each year, with approximately 220,000 fatalities1,2,3. The utilisation of insecticides has been demonstrated to exert a detrimental effect not only on target pests but also on beneficial insects, aquatic organisms, and humans, resulting in the occurrence of both acute and chronic toxic effects. The unintended consequences of this phenomenon have precipitated the accelerated development of more specific insecticides4,5. In this context, chemicals classified as insect growth regulators (IGRs) have been introduced and are increasingly utilised for the protection of stored agricultural products, such as grains. These chemicals disrupt the developmental stages of insects. It is widely accepted that IGRs exhibit species-specific activity, exhibiting minimal toxicity to non-target organisms6,7. Triflumuron (TFM) is a lipophilic insecticide belonging to the IGRs, containing benzoylphenylurea and exhibiting relatively low toxicity. The utilisation of TFM in agricultural contexts is pervasive, with the primary function being the mitigation of crop losses. The mechanism of action of TFM involves the inhibition or interference with chitin biosynthesis, a vital constituent of the insect exoskeleton. The chitin layer constitutes the fundamental structure of the insect cuticle and is imperative for molting and development8. TFM has been demonstrated to disrupt chitin biosynthesis by inhibiting N-acetylglucosamine transport across epithelial membranes, suppresses cuticle formation, and weakens the insect’s defences against pathogens1,9. In the case of Rhodnius prolixus, exposure to TFM has been demonstrated to result in delays in development, disruptions to molting, and ultimately, mortality. In addition, TFM has been documented to reduce larval numbers, damage eggs, and cause embryonic death during the pupal stage. In instances where insects successfully hatched from the pupal stage, lethal effects were observed within a few days1. The half-life of TFM in soils with a pH of 7 and at laboratory conditions of 25 °C is approximately 465 days. TFM demonstrates stability against hydrolysis at pH 5 and 7, indicating that it does not undergo chemical degradation in water or degrades at a rate that is exceptionally slow. In summary, the persistence of TFM is contingent upon a number of factors, including pH, temperature, microorganism activity, moisture, and soil physical and chemical properties (such as organic content and texture). FAO/WHO concluded that TFM has low genotoxicity potential in vivo, shows no evidence of carcinogenicity in mice or rats, and is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from dietary exposure10,11.

TFM, while primarily designed to target insects, has also been shown to induce toxicity in non-target organisms through various mechanisms. The ingestion of foodstuffs contaminated with TFM has been demonstrated to induce symptoms of toxicity in humans, including nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Furthermore, exposure to concentrations ranging from 50 to 200 µM has been demonstrated to induce oxidative stress and result in cytotoxic/genotoxic damage to the liver and spleen. Genotoxicity is further evidenced by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, imbalance in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, and DNA fragmentation, all indicative of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis12,13. Studies on acute toxicity in mammalian models, including rats, dogs, and rabbits, report symptoms such as seizures, spasms, respiratory distress, skin irritation, and severe ocular damage1. However, investigations regarding TFM’s phytotoxicity remain limited. Translocation studies in crops such as apples, soybeans, and potatoes have indicated that TFM is poorly translocated within plant tissues, with residues primarily accumulating on the surface of fruits. When applied to soybeans and potatoes, residue levels in edible parts were significantly lower than in inedible parts14. However, despite its widespread use and known effectiveness against target insects, studies addressing the broader physiological, cytogenetic, and ecological effects of TFM on non-target organisms are lacking. This study investigated the comprehensive toxic effects of TFM on non-target organisms and the potential use of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract to mitigate these toxic effects.

Plants are increasingly recognized not only for their therapeutic properties but also for their potential to counteract the toxic effects of harmful chemicals. In this context, the present study explores the protective role of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract against TFM-induced toxicity. Capsella bursa-pastoris is an annual plant belonging to the Brassicaceae family, which is distributed across a wide geographical range, reaching heights of up to 60 centimetres. The stem is characterised by its hairiness, and the taproot system has the capacity to penetrate soil to a depth of 10 to 25 centimetres, the extent of this penetration being contingent upon the environmental conditions15. It exhibits exceptional adaptability, allowing it to thrive in a wide range of climates and altitudes16. Literature studies have revealed the presence of many active compounds, including flavonoids and phenolic compounds, as well as terpenoids, saponins, alkaloids, and steroids. The aerial parts (stem, leaves, flowers) are particularly rich in flavonoids, polypeptides, choline, acetylcholine, histamine, and tyramine. It has been documented that the plant extract is characterised by elevated concentrations of flavonoids, including quercetin and kaempferol, in addition to phenolic glycosides, such as β-hydroxy-propiovanillon-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, capcelloside and (+)-pinoresinol-β-D-glucoside17. The bioactive components contained within the plant have been demonstrated to provide biological and pharmacological activities. The main activities detected include antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant and hepatoprotective properties. C. bursa-pastoris has been found to exhibit selective antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria, especially suppressing the synthesis of DNase, hemolysin and lipase and basic virulence factors18. Its anticancer potential has also been proven; fumaric acid, isolated from the plant, has been shown to significantly inhibit the growth and viability of MH134 and L1210 mouse tumour cells19. The plant’s antioxidant capacity is pivotal in mitigating free radical-induced damage and reducing the risk of chronic diseases. Several flavonoids isolated from C. bursa-pastoris have exhibited strong radical scavenging activity against DPPH, peroxyl, hydroxyl, and hydrogen peroxide radicals, affirming the extract’s antioxidant potency20.

This study contributes significantly to the literature by highlighting the potential of plant-based approaches in reducing insecticide toxicity. While the genotoxic effects of TFM in plants have been previously documented, there are no studies investigating a comprehensive toxicity profile and the mitigation of these harmful effects with plant extracts. In particular, there is a lack of comprehensive research examining the protective roles of Capsella bursa-pastoris, which holds significant ethnobotanical value. The key element that distinguishes this study is the adoption of a multifaceted approach that investigates both the potential toxic effects and the protective capacity of the C. bursa-pastoris extract. Phenolic profile analyses using LC-MS/MS techniques, combined with the Allium cepa test, provide comprehensive data at both the chemical and biological levels. The morphological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and phytochemical assessments conducted within the scope of the study provide a more holistic understanding of the plant’s potential protective mechanisms. By correlating the obtained biological data with the phenolic compound content, this study contributes not only to environmental toxicology but also to fields such as pharmacognosy and environmental biotechnology.

Materials and methods

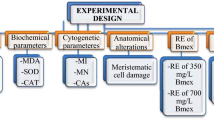

Development of experimental group framework

In this study, Allium cepa bulbs, commercially purchased from Giresun province, were used as bioindicators. TFM (CAS: 64628-44-0, Sigma-Aldrich) insecticide was used as the toxicity agent. TFM application doses were determined based on EC50 values. For this purpose, the inhibition of root growth in Allium bulbs germinated in TFM solutions (0–100 µg/L) was investigated. The dose at which root growth was inhibited by 50% was accepted as the EC50 value. 50% inhibition of root growth was detected at a dose of 20 µg/L, and TFM, was used at this dose in this study. In this study, Capsella bursa-pastoris extract was used as a protective product against TFM toxicity. The protective effect against toxic agents is often associated with antioxidant activity. Application doses of C. bursa-pastoris were determined based on IC50 values for antioxidant activity. The IC50 value is a representative concentration required to inhibit 50% of free radicals. There are studies in the literature reporting the IC50 value of C. bursa-pastoris extracts prepared with different solvents in the free radical scavenging range of 49.5–235 µg/mL21,22. This wide range reported in the literature may be associated with the diversity of secondary compounds produced by the plant to adapt to its growing environment. To determine the extract dose used in this study, the IC50 value for superoxide radical scavenging activity of C. bursa-pastoris was investigated. Details of the superoxide radical scavenging activity test and the extraction procedure of plant are presented in the supplementary material file. The IC50 value was found to be 45 µg/mL as a result of the scavenging test (Figure S1). In this study, doses of 45 µg/mL (equivalent to IC50) and 90 µg/mL (twice the IC50) were used to determine the protective effect. Both the toxicity of C. bursa-pastoris and its protective role against TFM toxicity were investigated at these doses. Allium cepa and Capsella bursa-pastoris species used in this study were commercially obtained and taxonomically verified by Prof. Dr. Zafer TÜRKMEN at the Department of Botany, Faculty of Science and Art, Giresun University. The specimens were deposited in the herbarium under the voucher numbers BIO-Al-ce24 and BIO-Ca-pa24, respectively. Guidelines and legislation at the institutional, national, and international levels are followed when conducting experimental research on plant samples, including the provision of plant material.

To evaluate the toxicity of TFM and the protective potential of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract (CBPE) against this toxicity, six experimental groups were established. The control group was treated with distilled water. To assess the intrinsic toxicity of the extract, two groups received CBPE alone at concentrations of 45 µg/mL (CBPE1) and 90 µg/mL (CBPE2), respectively. The toxic effect of TFM alone was determined in a separate group exposed to 20 µg/L TFM. Protective efficacy of the extract was investigated in groups co-treated with TFM and CBPE, where reductions in toxicity were evaluated as indicators of the extract’s ameliorative role. Specifically, the combined treatment groups consisted of TFM + CBPE1 (20 µg/L TFM + 45 µg/mL CBPE) and TFM + CBPE2 (20 µg/L TFM + 90 µg/mL CBPE).

Quantitative profiling of phenolic constituents

The phenolic profile of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract was quantitatively determined using LC-MS/MS chromatography. One gram of plant material was extracted with a methanol: dichloromethane solvent mixture in a 4:1 ratio. The resulting extract was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter prior to analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed on an ODS Hypersil column using a Thermo Scientific LC-MS/MS system. The column oven temperature was maintained at an optimized 30 °C, and the mobile phase was delivered at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. The total runtime for the analysis was 34 min. Eqaution and linear ranges, gradient profile of LC-MS/MS and ions in MS/MS were given in Table S1, Table S2 and Table S3, respectively. Amount of phenolics, Rt, R2, LOD (mg/L), LOQ (mg/L) and RSD% values were given in Table S4. All analyses were conducted at the Scientific and Technical Application and Research Center (HUBTUAM) of Hitit University.

Biomarkers of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress was evaluated by assessing the enzymatic activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), as well as the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and proline. A unified protocol was employed for the extraction of the antioxidant enzymes SOD and CAT, which are integral to the enzymatic defense mechanisms against oxidative stress. Fresh Allium cepa root samples (0.5 g) were ground in a precooled mortar using 5 mL of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) at approximately 4 °C. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 10,500 × g for 20 min. The supernatant, containing the target enzymes, was carefully transferred into clean tubes and stored at 4°C23.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assessed using the protocol proposed by Pehlivan et al.24, and expressed as U/mg. CAT activity was determined according to the method suggested by Kutluer et al.25, and expressed as OD₂₄₀ min/g. To determine malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, 0.5 g of fresh Allium cepa root tissue was homogenised in 1 mL of freshly prepared 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The homogenate was used to determine the MDA level according to the procedure proposed by Yalcin and Cavusoglu26, and the MDA level was expressed as µM/g FW. For proline quantification, 0.5 g of fresh root tissue was homogenised in 10 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid. The homogenate was filtered through filter paper and used for proline analysis. A standard curve was prepared using known concentrations of proline and the sample concentrations were calculated27. Proline levels were expressed as µmol/g FW. Analyses were performed in triplicate. Detailed information regarding analyses of oxidative stress parameters is provided in supplementary material file.

Investigation of growth and germination metrics

To evaluate the phytotoxic effects of TFM and the potential protective efficacy of CBPE on physiological performance, three critical parameters were systematically assessed: germination percentage (%), total fresh biomass increment (g), and root elongation (cm). Uniformly sized Allium cepa bulbs were carefully selected for each experimental cohort to minimize size-related variability and were pre-conditioned by immersion in distilled water for 24 h to standardize initial hydration status. Baseline fresh weights were precisely determined using a high-resolution analytical balance prior to treatment initiation. Following a controlled exposure period of germination, bulbs were carefully extracted, superficially dried to remove excess moisture, and reweighed to establish final fresh weights (n = 50). The net biomass gain was calculated as the difference between final and initial weights, providing an index of growth performance under treatment conditions28. Root length was quantitatively measured using a calibrated ruler, with measurements taken from the radicle emergence point to the apical root tip, ensuring accuracy in elongation assessment. For root elongation, 10 bulbs were used in each group and 5 root lengths were measured randomly from each bulb29. Germination percentage was defined as the ratio of bulbs showing root growth to the total number of bulbs and expressed as a percentage (n = 50)30.

In order to ascertain the effects of TFM and CBPE treatments on photosynthetic pigment levels, the protocol described by Kaydan et al.31 was followed to determine chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents. The quantification of chlorophyll a and b concentrations was conducted in accordance with the methodologies outlined by Witham et al.32, employing Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively.

where V denotes the final volume (mL) of the supernatant in 80% acetone, and W is the fresh weight (g) of the leaf tissue.

DNA damage and genotoxic stress responses

In order to ascertain the effects of TFM insecticide and CBPE applications on cytogenetic parameters, mitotic index (MI), micronucleus (MN), chromosomal aberration (CA) and DNA damage analyses (comet test) were performed. All genotoxicity tests were also performed on harvested root tips after germination. In order to ascertain the frequencies of MI, MN, and CA, root tips were subjected to staining with acetocarmine following the fixation and hydrolysis steps. Following the completion of the 24-hour staining process, the root tips were placed on slides and covered with coverslips. The samples were then photographed under a light microscope, and damage scores were determined33. A total of 10,000 cells were examined in each group for MI analysis. MI was calculated as the number of cells in mitosis/the percentage of the total number of cells. A total of 1000 cells were examined to screen for MN and CA frequencies. The comet assay was performed according to the protocol outlined by Dikilitaş and Koçyiğit34 and the details of method are given in supplementary material file. Fluorescence microscopy was employed to capture images of the preparations. Comet analysis was conducted on 1000 cells per group using the “TriTek 2.0.0.38 Automatic Comet Assay” software. Percentages of DNA content in the comet head and tail regions were quantified, with tail DNA percentage serving as the indicator of DNA damage. Based on these values, average DNA damage levels were classified according to the criteria established by Pereira et al.35.

Histoanatomical assessment of root meristematic

For anatomical evaluations, transverse sections were carefully obtained from the root tips using a sharp razor blade. The sections were placed onto microscope slides and stained with approximately one drop of 5% methylene blue solution. The staining procedure was carried out for 2 min. Following staining, coverslips were placed over the sections. The prepared slides were examined using a research microscope (Irmeco IM-450 TI model) equipped with a digital camera system to evaluate potential cellular-level abnormalities. Microscopic imaging was conducted at a magnification of x20036. From each bulb, 10 root cross-sections were obtained, resulting in 100 sections per group. 0–5 damage: (–) No damage; 6–25 damage: (+) Low damage; 26–50 damage: (++) Moderate damage; 51 or more damage: (+++) Severe damage.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using the SPSS Statistics 22 software (IBM SPSS, Turkey). To determine statistical differences among groups, one-way ANOVA was applied, followed by Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. The results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were considered statistically significant at p-values below 0.05. The data showed normal distribution according to both the Shapiro-Wilk Test and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the Swekness-Kurtosis values of the data were also within the normal distribution range (−1, + 1). Therefore, parametric tests were used for statistical analysis. Since the Levene test demonstrated homogeneous distribution of variances during data analysis, the Duncan test was applied to determine statistical differences between the groups.

Results and discussion

Biomarkers of oxidative stress

Although the direct measurement of free radicals provides a clear indication of oxidative stress, their highly reactive nature and extremely short half-life make them difficult to detect in living organisms, often resulting in variable and instantaneous data. Therefore, in this study, more stable and reliable indicators such as lipid peroxidation products were selected to better reflect the effects of oxidative stress at the cellular level. In this context, MDA, proline content, and the activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD and CAT were measured and evaluated collectively. The effects of TFM and CBPE treatments on oxidative stress-related parameters are presented in Fig. 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the control and CBPE-only groups in any of the tested parameters (p > 0.05). The MDA level, which was 4.21 ± 0.16 µM/g in the control group, increased markedly to 18.2 ± 0.28 µM/g following TFM exposure (p < 0.05). However, in the group treated with both TFM and 90 µg/mL CBPE, MDA levels decreased to 10.1 ± 0.40 µM/g. This statically significant increase in MDA levels upon TFM treatment indicates the presence of lipid peroxidation and thus oxidative stress. Conversely, co-administration with CBPE led to a gradual decrease in MDA levels, suggesting that CBPE alleviates oxidative stress by limiting cellular membrane damage.

Proline, a key amino acid accumulated in plants in response to stress, also showed a marked increase following TFM treatment, indicating an adaptive stress response. While the proline content was 12.0 ± 0.57 µmol/g in the control group, it increase by approximately 2.13-fold to reach 25.6 ± 0.89 µmol/g in the TFM-treated group. Co-treatment with CBPE reduced proline levels, indicating a mitigation of stress conditions. Significant alterations were also observed in antioxidant enzyme activities. SOD activity, which increased by 1.85-fold under TFM exposure, reflects an enhanced cellular defense against reactive oxygen species. CBPE treatment lowered SOD activity to a more moderate level, still above control values, indicating a more balanced functioning of the antioxidant system. In the group treated with 20 µg/L TFM and 90 µg/mL CBPE, SOD activity showed a 27.7% decrease compared to the TFM-only group. Similarly, CAT activity peaked in the TFM-treated group, serving as another marker of oxidative stress. While no statistically significant change was observed in CAT activity in the TFM and TFM + CBPE1 groups (p > 0.05), a 29.2% reduction was detected in the TFM + CBPE2 group. The observed decreases in enzyme activity upon CBPE treatment suggest that the extract may alleviate stress conditions and contribute to restoring enzyme levels toward normal physiological ranges.

Effects of CBPE and TFM treatments on biomarkers of oxidative stress. CBPE1: 45 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, CBPE2: 90 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, TFM: 20 µg/L TFM, TFM + CBPE1: 20 µg/L TFM + 45 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, TFM + CBPE2: 20 µg/L TFM + 90 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05: compared to the control group; **p < 0.05 compared to the TFM treated group. MDA: µM/g FW; Proline: µmol prolin/g FW; SOD: U/mg FW; CAT: OD240nm min/g.

The biochemical alterations observed following TFM treatment are most likely attributable to the elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These molecules, which induce oxidative stress within plant cells, are known to damage essential biomolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA. The increased MDA levels serve as a clear indicator of lipid peroxidation and underscore the deleterious impact of TFM exposure37. In response to rising ROS levels, plants activate antioxidant defense mechanisms, particularly enzymes like SOD and CAT, which function to convert superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide into less harmful compounds. SOD and CAT are key antioxidant enzymes that work together to maintain cellular redox balance under stress, including TFM exposure. SOD and CAT act sequentially to neutralize ROS, and their activity levels provide a practical measure of how well the plant’s antioxidant system is coping with stress38,39. Proline accumulation, which plays a protective role in maintaining osmotic balance under various stress conditions such as drought, salinity, or toxic exposure, was also enhanced in TFM-treated group. This increase suggests that the plant initiated an osmoprotectant-based defense mechanism against TFM-induced toxicity40. Although TFM is not directly intended for plant targets, its application disrupts cellular integrity through oxidative mechanisms, challenges enzymatic antioxidant systems, alters osmotic regulation, and suppresses photosynthetic efficiency. In this context, the observed increases in MDA and proline levels, as well as the elevated activities of SOD and CAT, appear to be physiological responses to oxidative damage. Consistent with these findings, several in vivo studies in the literature have demonstrated that TFM induces oxidative stress in non-target organisms by promoting excessive ROS production, leading to altered cellular homeostasis, lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and disruption of antioxidant enzyme systems. These biochemical disruptions are often associated with significant DNA damage and genotoxic outcomes7,12,13. Although data specifically addressing the biochemical impacts of TFM on plants remain limited, numerous reports have confirmed that exposure to various pesticides and environmental chemicals, including insecticides, results in oxidative stress and imbalance in the antioxidant defense system41,42,43.

Investigation of growth and germination metrics

The effects of CBPE and TFM treatments on physio-morphological parameters are illustrated in Fig. 2. The analysis revealed that there were no statistically significant differences in germination rates, biomass increase, and root length data between the control group and the CBPE1 and CBPE2 groups (p > 0.05). The TFM application caused a significant decrease in germination rates, resulting in an 85% germination rate. This decline was found to be statistically significant in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05). When CBPE and TFM were applied in combination, an increase in germination rates was observed, ranging from 60% to 74%, respectively compared to TFM-treated group. These groups were found to be significantly different from both the control group and the TFM group (p < 0.05). In summary, CBPE treatments alone did not have a toxic effect on germination; however, the negative effect of TFM was reduced when CBPE was applied in combination with TFM. A substantial number of anomalies were identified in the root length data and it was determined that TFM treatment significantly retarded root growth. The mean root length in the control group was found to be 8.00 cm. In the CBPE1 and CBPE2 treated groups, these values were 8.07 cm and 8.12 cm, respectively. Treatment with 20 µg/L TFM resulted in a reduction in root growth of approximately 50% (p < 0.05). No enhancement in root growth was observed in the group treated with 45 µg/mL CBPE in conjunction with TFM (p > 0.05). In particular, the treatment of 90 µg/mL CBPE significantly reduced the inhibitory effect of TFM on root growth, enhancing root growth by 28% and supporting root growth to a relatively greater extent. The results of this study suggest that CBPE extracts alone do not have a negative effect on root growth, but may have the potential to partially mitigate the phytotoxic effects of TFM. TFM application caused a significant decrease in germination rate and root growth as well as biomass gain. The data observed in the control group and CBPE1 and CBPE2 groups were found to be almost identical (10.3–10.7 mg), indicating that CBPE extracts alone do not have a negative effect on plant growth. The TFM treatment demonstrated a significant reduction in fresh biomass gain, with a decrease of approximately 66% in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05). CBPE1 co-application with TFM resulted in a 11.7% increase in biomass gain compared to the TFM group, suggesting that CBPE1 only slightly suppressed TFM-induced toxicity. In the TFM + CBPE2 group, a 68.5% improvement in biomass gain was observed. This increase indicates that 90 µg/mL CBPE extract was more effective in reducing the harmful effects of TFM.

The phenomenon of germination delay has been frequently linked to the presence of oxidative stress. The results of a previous analysis of this study support the notion that TFM induces oxidative stress, as indicated by increases in MDA, proline, SOD, and CAT levels. Oxidative stress has been demonstrated to prolong or inhibit germination by damaging embryonic cells or disrupting energy metabolism44,45. Roots represent one of the earliest tissues in a plant to detect environmental stress. The abnormalities observed in physiomorphological development in TFM-treated plants may be related to several mechanisms, but oxidative stress is a primary cause. Oxidative stress reduces both the division and elongation of meristematic cells. Root development is necessary for the continuation of the germination process, and abnormalities in root growth also delay germination. In summary, the findings indicate that delayed germination and suppressed root growth are direct consequences of oxidative stress46,47,48. Similarly, Bıyıksız et al.49 reported that TFM application significantly reduced germination, root elongation and weight gain in non-target plants, and this effect observed in growth retardation may be related to oxidative stress.

TFM treatment retarded physiological development and caused abnormalities in germination, rooting and biomass increment. The observed regressions in growth may also be related to photosynthesis and for this purpose, chlorophyll a and b pigment levels were measured in leaf samples (Fig. 2). Chlorophyll a and b levels were similar in control, CBPE1 and CBPE2 groups (16.7–17.1 mg/g). TFM application significantly decreased the chlorophyll a content and caused it to decrease to 6.36 mg/g. TFM caused about 62% reduction in chlorophyll a content. This result reveals that TFM showed a strong phytotoxic effect suppressing photosynthetic pigments. In the TFM + CBPE1 group, chlorophyll a level increased to 9.45 mg/g, which represents an improvement compared to the TFM group, but is well below normal levels. In the TFM + CBPE2 group, chlorophyll a value increased up to 12.9 mg/g and this increase indicates that CBPE2 significantly inhibited TFM-induced chlorophyll degradation. When chlorophyll b levels were analyzed, TFM caused a decrease of about 49% in chlorophyll b content. CBPE1 treatment could hardly ameliorate this decrease (p > 0.05), while CBPE2 significantly increased the chlorophyll b level and suppressed the toxic effect of TFM (p < 0.05). Exposure to pesticides such as TFM may result in a decrease in chlorophyll a and b levels due to oxidative damage and disruption of chloroplast structure. Stress can reduce enzymes involved in chlorophyll formation, and oxidative stress can further reduce chlorophyll content by damaging photosynthesis-related proteins and pigments. Plant-derived products, including CBPE, can help restore chlorophyll levels through various mechanisms through their antioxidant effects. These mechanisms include reducing oxidative damage to chloroplasts by scavenging ROS, maintaining thylakoid integrity by stabilizing membranes, and promoting the resumption of chlorophyll biosynthesis by supporting photosynthetic enzyme function50.

Effects of CBPE and TFM treatments on physio-morphological parameters. CBPE1: 45 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, CBPE2: 90 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, TFM: 20 µg/L TFM, TFM + CBPE1: 20 µg/L TFM + 45 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract, TFM + CBPE2: 20 µg/L TFM + 90 µg/mL C. bursa-pastoris extract. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05: compared to the control group; **p < 0.05 compared to the TFM treated group.

DNA damage and genotoxic stress responses

The protective role of CBPE against genotoxicity caused by TFM is given in Table 1; Fig. 3. With regard to the MI values, comparable values were observed in the control group (8.62%), CBPE1 (8.65%) and CBPE2 (8.66%) groups, and no significant difference was found between these groups (p > 0.05). However, TFM application reduced MI to 6.57%, and this decrease was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). MI values increased by 7.05% and 7.55% in the TFM + CBPE1 and TFM + CBPE2 groups, respectively, indicating that the adverse effects of TFM were alleviated to some extent. With regard to the levels of chromosomal aberrations, the MN rate was 0.40 ± 0.52 in the control group, while it increased to 70.5 ± 2.92 in the TFM group. In the CBPE1 and CBPE2 treatments combined with TFM, MN rates decreased to 59.3 ± 4.27 and 45.3 ± 3.20, respectively, demonstrating a reduction in damage. Concurrently, the sticky chromosome ratio exhibited an increase from 0.90 ± 0.57 in the control group to 60.7 ± 4.21 in the TFM group. A number of other types of damage were also found to increase significantly following TFM treatment. These included chromosome bridges, fragments, an unequal distribution of chromatin, and the presence of vagrant chromosomes. The administration of CBPE in conjunction with TFM led to a reduction in chromosomal aberration levels. MN, which exhibited the highest aberration frequency, demonstrated a decrease of 15.88% in the TFM + CBPE1 group and 35.7% in the TFM + CBPE2 group compared to the TFM group. The findings of this study suggest that CBPE extracts, when administered in isolation, do not induce genetic damage and can mitigate the adverse effects of TFM. The CBPE administration exhibited an augmented protective effect against genotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner, with the CBPE2 dose demonstrating particular efficacy in diminishing TFM-induced genotoxicity.

The comet test results for the TFM and CBPE-treated groups are presented in Table 1 and comet images were given in Figure S1. In the comet test, the head DNA and tail DNA percentages are particularly important in assessing DNA fragmentation. The tail DNA ratio (57.7%) and tail moment (29.42%) increased significantly in the TFM-treated group. This clearly indicates the genotoxic effect of TFM, indicating that DNA was dissociated from the nucleus and transported to the tail region. TFM-induced DNA damage was partially reduced when treated with CBPE. Specifically, in the TFM + CBPE group, the head DNA ratio increased to 79.6%, while the tail DNA ratio decreased to 20.4%. The tail moment value also decreased to 8.35 in this group, supporting the dose-dependent protective effect of CBPE on DNA. In the comet test, the DNA tail is a microscopic indicator of damage to cellular DNA. This test is used specifically to detect DNA strand breaks at the single-cell level. In this study, control (undamaged) DNA remained in the nucleus, while damaged (broken) DNA formed a tail in the TFM-exposed groups. In conclusion, C. bursa-pastoris extract appears to be effective in reducing DNA damage caused by TFM, especially when used at high concentrations. This protective effect may be related to the possible antioxidant properties of CBPE or its DNA repair-supporting components.

Although TFM is not primarily designed to target plant systems, it has been shown to exert various genotoxic effects. The most obvious cytogenetic abnormalities observed in Allium cepa root meristems under TFM exposure were MN, sticky chromosome, fragments, and breaks. These abnormalities likely indicate the genotoxic effects of TFM, which are caused by ROS-induced DNA damage and interference with the mitotic mechanism. The potential principal mechanism by which TFM induces chromosomal abnormalities in plants involves the disruption of critical events during cell division, particularly DNA replication and chromosome segregation. One possible disruption could be interference with spindle fiber formation during mitosis, compromising chromosomal alignment and segregation. This leads to structural anomalies such as chromosomal bridges, stickiness, fragmentation, and lagging chromosomes51,52. In addition to its direct intervention in mitotic processes, TFM can also cause genotoxicity through the production of oxidative stress in plant cells. TFM-induced oxidative stress was confirmed in previous analyzes of this study. Elevated oxidative stress can induce single- and double-strand breaks in DNA, base modifications, and chromosomal ruptures, thereby posing a significant threat to the integrity of genetic material and overwhelming cellular repair mechanisms. Oxidative stress triggered by ROS is likely a major factor contributing to chromatin disorganization and chromosome fragmentation53,54. Furthermore, TFM has been reported to influence plant growth indirectly through hormonal imbalances. Disruption of phytohormone homeostasis can impair cell cycle regulation, thereby reducing chromosomal stability and increasing susceptibility to genotoxic damage55,56. In summary, the genotoxic effects of TFM appear to result from its dual impact: direct interference with cellular division processes and the induction of chromosomal damage through oxidative stress. These disruptions not only hinder normal plant development but may also cause lasting structural damage to the genome37,57. Several studies in the literature corroborate the findings of the present research by reporting genotoxicity associated with TFM exposure. Bıyıksız et al.49 observed that TFM treatment led to a reduction in cell proliferation by 8.3% to 25.7% in Allium cepa, and triggered a range of chromosomal abnormalities, particularly MN formation. Similarly, Timoumi et al.13 reported that TFM exerted dose-dependent genotoxic effects in non-target organisms, notably increasing micronucleus frequency. de Barros et al.58 reported that diflubenzuron, an insect growth regulators like TFM, generated significant DNA tails in the comet assay at all tested doses.The authors suggested that oxidative stress might be the underlying mechanism responsible for the observed toxicity.

CBPE exhibited a significant protective role against TFM-induced genotoxicity and this feature may be associated with phenolics. Many phenolic compounds detected in the CBPE structure play an important role in this protective activity. p-coumaric acid acts as a direct scavenger of hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions. It stimulates the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and provides protection by reducing oxidative DNA damage (e.g., strand breaks, 8-OHdG formation). It also reduces secondary genotoxic stress by preventing mutagenic aldehyde formation caused by lipid peroxidation. Rutin prevents Fenton-type radical formation by chelating transition metals (Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺). It increases cellular GSH content and activity of SOD, CAT, and GPx. It stabilizes membranes by preventing ROS-induced lipid peroxidation. It also prevents DNA strand breaks induced by radicals such as hydrogen peroxide and reduces micronucleus formation. Ferulic acid, on the other hand, has strong hydrogen atom donation and electron transfer capacity thanks to its phenoxy radical stability. It maintains redox homeostasis by alleviating ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. It prevents oxidative modifications of nucleotides. Quercetin is also a powerful antioxidant. It is a potent scavenger of hydroxyl, peroxyl, and superoxide radicals. It regulates mitochondrial ROS production and maintains ETS integrity. It has also been shown to prevent chromosomal aberrations and MN formation in genotoxic stress tests59,60,61,62.

Structural deterioration in meristematic cells

The morphological damage induced by TFM in Allium cepa root meristematic cells, along with the potential protective role of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract, is presented in Fig. 4; Table 2. When administered alone, CBPE did not elicit any observable anatomical abnormalities, suggesting that the extract is non-toxic at the structural level and can be considered biologically safe. In contrast, the group treated solely with TFM exhibited marked structural disruptions in meristematic tissue. Severe damage was particularly evident in the epidermal layer (+++), accompanied by moderate degeneration in cortical cells (++), significant thickening of cortical cell walls (+++), and pronounced nuclear deformities, including nuclear flattening (+++).Co-application of CBPE with TFM resulted in a substantial reduction in damage severity. In the group treated with 20 µg/L TFM and 45 µg/mL CBPE, epidermal and cortical cell damage was reduced to moderate levels (++), cortical wall thickening was limited to a mild degree (+), and nuclear deformities were notably alleviated (++). The combination of TFM with 90 µg/mL CBPE further enhanced the protective effect: epidermal damage was minimal (+), structural disintegration in cortical tissues was absent (–), and both wall thickening and nuclear distortion were significantly reduced (+). These findings indicate that CBPE possesses considerable cytoprotective potential, likely mediated by its antioxidant properties and capacity to stabilize cellular architecture. The extract appears to mitigate TFM-induced cytological impairments and restore structural integrity in root meristematic cells.

Meristematic cell damage caused by TFM insecticide. a. normal appearance of epidermal cells, b. abnormalities in epidermal cells, c. normal appearance of cortical cells, d. cortical cell damage, e. thickening of cortical cell walls, f. appearance of control nucleus, g. flattened nucleus. Bar: 10 μm.

These results may indicate that TFM disrupts both cell division and tissue organization, potentially by interfering with microtubule assembly and cell wall synthesis mechanisms. The anatomical damage observed in the TFM group may be associated with various deteriorations at the cellular and molecular levels. The epidermal and cortical cell deformations and nuclear flattening observed in the TFM group may be related to the disruption of membrane integrity resulting from ROS accumulation and oxidative stress37. Meristematic cells are characterised by their high level of proliferative capacity, and oxidative stress induced by compounds such as TFM has been demonstrated to disrupt the permeability of epidermal and cortical cell membranes. It has been demonstrated that this can result in structural abnormalities, including, but not limited to, abnormal cell wall thickening. The biosynthesis of cell wall components such as cellulose and lignin is imperative for the maintenance of cortical and epidermal tissues. However, chemical agents like TFM can interfere with these biosynthetic pathways, resulting in irregular wall thickening, reduced elasticity, or structurally weakened cell walls. Since epidermal cells play a central role in maintaining water balance, chemical-induced disruption of membrane integrity may also disturb osmotic regulation, ultimately leading to cellular damage63,64. This study found that TFM also triggers cytogenetic abnormalities, reduces cell proliferation, and causes chromosomal aberrations. TFM application can disrupt the proper functioning of microtubule structures, which play a crucial role during cell division. This can lead to defective mitotic spindle formation, irregular cell division, and, ultimately, nuclear disruption. The observed flattened nuclei and cellular irregularities are associated with such cytoskeletal disruptions65,66. While TFM inhibits chitin synthesis in insects, it may similarly affect the activity of enzymes involved in cell wall biosynthesis in plants. This can be observed as abnormal thickening or weakening of the cortical cell wall. In particular, the loss of mechanical support in the cell wall compromises tissue integrity. Supporting our study, Bıyıksız et al.49 also found that TFM induced damage in epidermal and cortical cells in meritematic tissue. Although studies reporting the anatomical damage caused by TFM application in plants are quite limited in the literature, there are many studies reporting that insecticides and chemical exposure used for similar purposes cause meristametic damage in plants67,68.

CBPE application caused regression in anatomical damage induced by TFM. This protective property exhibited by CBPE may be attributed to its phenolic compounds, especially coumaric acid. p-coumaric acid is a key intermediate compound in the phenylpropanoid pathway and plays a direct role in lignin biosynthesis. Lignin is a phenolic polymer that accumulates in the plant cell wall and increases structural strength. In plants supplemented with p-coumaric acid, lignin synthesis increases, resulting in increased mechanical strength and tolerance to stress conditions. In particular, cortical cell wall thickening has been reported to be accelerated by coumaric acid supplementation. p-coumaric acid has the capacity to scavenge reactive oxygen species. Thus, it helps maintain the activity of lignin biosynthetic enzymes under oxidative stress and ensures the uninterrupted operation of the lignification process69,70.

Bioprotective potential of CBPE

CBPE demonstrated a strong protective effect against TFM-induced growth inhibition, genotoxicity, biochemical damage, and structural alterations in meristematic cells of Allium cepa. The extract mitigated these adverse effects to varying degrees, depending on the parameter assessed. While a dose-dependent protective trend was observed for certain indicators, others responded independently of dosage. This suggests that the protective action of CBPE may operate through multiple biological mechanisms rather than a single pathway. Application of CBPE at two different doses improved physiological development and pigment levels induced by TFM regression. Application of 45 µg/mL CBPE provided a 48.58% improvement in chlorophyll a level, but had no significant effect on chlorophyll b level. 90 µg/mL CBPE provided a 102.83% improvement in chlorophyll a and 55.14% improvement in chlorophyll b levels. The phenolic compounds found in CBPE also regulate plant hormones, providing protection during physiological development. p-coumaric acid, one of the CBPE phenolics, has been reported to increase abscisic acid accumulation under drought or salt stress, leading to stomatal closure and reduced water loss. This suggests a strengthening of abscisic acid-based stress responses. p-coumaric acid may also have a restorative effect by modulating root growth. Phenolic compounds found in plants also positively support development through hormonal regulation. Biostimulants and plants containing antioxidants such as CBPE also promote growth by strengthening the antioxidant system. Touzout et al.71 reported that biostimulants such as silicon provide protection by reducing the inhibition of growth and chlorophyll synthesis induced by pesticide exposure. They reported that this protective activity resulted from improved GSH-GST detoxification enzymes, the phenylpropanoid pathway, the antioxidant defense system, and indicators of oxidative stress (e.g., lipid peroxidation). CBPE exhibited a restorative effect particularly on biochemical markers (Fig. 5). At a concentration of 45 µg/mL, it reduced MDA level by 21.9% and proline levels by 14.8%; these reductions reached 44.5% and 34.7%, respectively, at 90 µg/mL. CBPE also improved enzymatic activities, with the higher dose (90 µg/mL) showing more pronounced protective effects. In the TFM + CBPE2 group, CAT activity improved by 29.2%, and SOD activity increased by 27.7% compared to the TFM-only group (Fig. 5).

CBPE also exhibited protective effects on cytogenetic parameters, with the degree of protection increasing in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5). At a dose of 45 µg/mL, CBPE provided the highest level of protection (31.4%) against unequal chromatin distribution, while the 90 µg/mL dose reduced the frequency of this abnormality by 59.8%. In contrast, CBPE at 45 µg/mL showed a very limited protective effect (0.95%) against chromosome fragments, whereas the 90 µg/mL dose reduced fragment frequency by 24.4%. These findings suggest that higher doses of the extract may be required to effectively mitigate certain types of abnormalities. The protective effect of CBPE, particularly against genotoxicity, is attributed to phenolic compounds. Although phenolic compounds are mostly known for their antioxidant activity, in recent years it has been demonstrated that these compounds can also regulate DNA repair pathways. The contribution of phenolics to DNA repair can be explained by several different mechanisms. During oxidative stress, frequent oxidation in DNA is corrected by enzymatic mechanisms. Phenolic compounds increase the expression of these enzymes, helping to more effectively remove oxidized bases. One of the most dangerous damages in DNA is double-strand breaks. Phenolics can regulate factors such as BRCA1, RAD51 (homologous recombination), and DNA-PKcs (NHEJ) by activating the ATM/ATR kinase pathways. In addition to direct mechanisms, indirect mechanisms such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects also provide significant protection. By reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, phenolic compounds reduce the damage load on DNA, allowing DNA repair systems to function more effectively. In short, phenolic compounds may have a dual protective effect by not only reducing DNA damage but also promoting the repair of existing damage72,73.

Protective percentages (%) of C. bursa-pastoris extract against TFM-induced toxicity. RL: root lenght, CAT: catalase, MDA: malondialdehyde, SOD: superoxide dismutase, Chl: chlorophyll, MN: micronucleus, SC: sticky chromosome, FRG: fragment, VC: vagrant chromosome, UDC: unequal chromatin distribution, B: bridge, RL: root length.

The protective properties of CBPE extract against TFM toxicity are closely related to its active ingredients, particularly its antioxidant phenolic compounds. For this purpose, the quantitative phenolic content of CBPE was analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and the results are presented in Fig. 6. According to the LC-MS/MS analysis results, various phenolic compounds were detected in the C. bursa-pastoris. The highest-containing phenolic compound in the plant was p-coumaric acid, at 783.927 µg/g. This amount corresponds to 61.94% of all phenolics detected. p-coumaric acid is a naturally occurring phenolic compound that is classified as a hydroxycinnamic acid derivative. Its chemical structure consists of a propenoic acid chain linked to a phenyl ring and a hydroxyl group in the para position. This structural configuration endows the molecule with both antioxidant properties and biological effects. p-coumaric acid, a widely occurring organic compound found in plants, functions as an intermediate metabolite in the biosynthesis of lignin and plays a significant role in the formation of cell wall structure. Furthermore, it is a naturally occurring constituent of various fruits, vegetables, and grains. In terms of its biological activities, p-coumaric acid has been shown to possess strong antioxidant properties. It has been demonstrated that the free radical scavenging effect of the substance in question provides protection for cells from oxidative stress. In addition to its antioxidant activity, there is a plethora of literature citing its anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer potential. In addition, p-coumaric acid has been demonstrated to attenuate DNA damage and exert a protective effect against genotoxic agents. This increase in potential is particularly significant in regard to its use as a bioprotective agent, especially in contexts where cellular damage is induced by toxins or chemicals. Consequently, p-coumaric acid, a naturally occurring phenolic compound, has potential as a preservative and therapeutic additive in food, medicine, and cosmetics74,75,76.

The rutin content detected in C. bursa-pastoris is also of note, with a level of 368.667 µg/g. The proportion of rutin among all phenolics was calculated to be 29.13%. Rutin is a glycoside compound belonging to the flavonoid class and contains a disaccharide (rutinose) specifically linked to the quercetin molecule. Rutin is distinguished by its notable antioxidant capacity. Rutin assists in the prevention of oxidative damage at the cellular level by neutralising free radicals. In addition to its antioxidant effects, rutin has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory, anticancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective properties. For instance, due to its strengthening effects on vascular structures, it has been demonstrated to reduce vascular permeability and increase capillary elasticity. As postulated by Chua77 and Ganeshpurkar and Saluja78, the anticancer effects of the subject are particularly associated with cell cycle regulating and apoptosis promoting mechanisms. Ferulic acid and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid were recorded in C. bursa-pastoris at levels of 22.873 µg/g and 22.755 µg/g, respectively. Phenolic acids such as caffeic acid (20.513 µg/g) and salicylic acid (17.355 µg/g) were also detected in significant amounts. Flavonoids and phenolics such as quercetin (7.163 µg/g), vanillin (10.486 µg/g), taxifolin (3.669 µg/g), catechin (3.001 µg/g), and epicatechin (2.397 µg/g) were also present at moderate/low levels. Additionally, compounds such as rosmarinic acid and oleuropein were present in lower amounts, while some phenolics (pyrogallol, gallic acid, protecatechuic acid, resveratrol, ellagic acid, etc.) were not detected. This diversity suggests that C. bursa-pastoris is not only rich in phenolic compounds, but also particularly concentrated in certain phenolic acids and flavonoids. This provides an important chemical basis for the plant’s potential biological activities.

There are studies in the literature that report the phenolic content of C. bursa-pastoris and detect different compounds. Onea et al.79 detected ferulic acid, quercetin, and rutoside in the aerial and underground parts of C. bursa-pastoris collected from Bihor County (Romania). Grosso et al.80 detected quercetin-6-C-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin, and kaempferol in C. bursa-pastoris purchased from a local market in Portugal, and reported that kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside was the major component. In this study, p-coumaric acid was detected as the major component, while the presence of kaempferol was not detected.These differences observed in the literature are related to the climatic conditions in which the plant grows, water stress and humidity, soil properties, biotic stress factors, and extraction conditions. In short, one of the most important reasons for differences in phenolic content is the plant’s biochemical responses to environmental stress and conditions80,81.

Conclusion

TFM is a fat-soluble insecticide belonging to the benzoylphenyl urea group and functions as an IGR by inhibiting chitin synthesis. Although it is primarily designed to target insect pests, emerging evidence indicates that TFM can also exert toxic effects on non-target organisms, including plants. However, data on its phytotoxic and genotoxic potential remain scarce. In this study, the multifaceted toxic effects of TFM were systematically investigated using the Allium cepa test system, which is widely recognized for environmental monitoring. The results demonstrated that TFM exposure led to significant suppression of plant growth, disruption of membrane integrity due to enhanced lipid peroxidation, and direct damage to genomic DNA. Additionally, a marked decrease in mitotic activity and photosynthetic pigments, increased micronucleus frequency, various chromosomal abnormalities, and anatomical alterations in the root meristem were observed. Elevated levels of MDA and proline and enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT also indicated the induction of oxidative stress.

To explore a potential mitigation strategy, the protective effect of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract—a plant known for its rich phenolic content—was evaluated under the same experimental conditions. This study presents the first comprehensive and controlled investigation into the ameliorative potential of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract against TFM-induced toxicity. The findings revealed that Capsella bursa-pastoris extract significantly alleviated all physiological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and anatomical damages caused by TFM, with the protective effect increasing in a dose-dependent manner. These observations suggest that Capsella bursa-pastoris extract may serve as a natural antioxidant-based bioprotective agent against pesticide-induced toxicity. This study makes a notable contribution to the current body of literature by providing detailed evidence of TFM-induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in a model plant system, while also introducing a novel plant-based approach to mitigate such damage. Given the limited scope of existing studies on the environmental toxicity of TFM in plant systems, this research fills a significant knowledge gap. CBPE, which reduces pesticide-related toxicity with the effect of the phenolic compounds, can also be transformed into various sustainable applications through product development in agricultural areas. Different methods can be developed for the agricultural application of CBPE extracts that exhibit protective effects against TFM toxicity. They can be applied as foliar sprays or soil tablets, complementing reduced doses of synthetic pesticides. CBPE-based products can be used as an environmentally friendly application in agricultural fields as agents that protect plants against stress, reduce the need for chemical pesticides, and enhance soil health and plant resistance. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the findings are based on laboratory-scale experiments using a single test organism. Therefore, further studies involving diverse plant species and broader ecological conditions are needed to validate these results and support the development of sustainable, plant-derived bioprotective strategies in agricultural practices. Additionally, synergistic studies combining Capsella bursa-pastoris extract with other antioxidant-rich bioformulations could be explored to evaluate potential enhanced protective effects against pesticide-induced toxicity, supporting the development of sustainable, plant-derived bioprotective strategies in agricultural practices.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current investigation will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Timoumi, R. et al. Mini-review highlighting toxic effects of triflumuron in insects and mammalian systems. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 37 (6), e23341. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.2334 (2023).

Touzout, N. et al. Silicon-mediated resilience: unveiling the protective role against combined Cypermethrin and hymexazol phytotoxicity in tomato seedlings. J. Environ. Manag. 369, 122370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122370 (2024).

Touzout, N. et al. Nitric oxide application alleviates fungicide and ampicillin co-exposure induced phytotoxicity by regulating antioxidant defense, detoxification system, and secondary metabolism in wheat seedlings. J. Environ. Manag. 372, 123337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123337 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Combined exposure of beta-cypermethrin and Emamectin benzoate interferes with the HPO axis through oxidative stress, causing an imbalance of hormone homeostasis in female rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 123, 108502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2024.108502 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Nanoplastics drive the charge-specific decline of aquatic insect (Chironomus kiinensis) emergence through inducing oxidative damage and perturbing the endocrine system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 16864–16876. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c04923 (2025).

Bull, D. L. & Meola, R. W. Effect and fate of the insect growth regulator Pyriproxyfen after application to the Horn fly (Diptera: Muscidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 86 (6), 1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/86.6.1754 (1993).

Tunaz, H. & Uygun, N. Insect growth regulators for insect pest control. Turk. J. Agric. For. 28 (6), 377–387 (2004).

Merzendorfer, H. & Zimoch, L. Chitin metabolism in insects: structure, function and regulation of Chitin synthases and Chitinases. J. Exp. Biol. 206 (24), 4393–4412. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00709 (2003).

Saguez, J., Vincent, C. & Giordanengo, P. Chitinase inhibitors and Chitin mimetics for crop protection. Pest Technol. 2 (2), 81–86 (2008).

World Health Organization & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Pesticide residues in food – 2019: toxicological evaluations. Triflumuron. (World Health Organization & FAO. (2019). Available at: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA6969EN

European Food Safety Authority & EFSA. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance triflumuron. EFSA J. 7 (131r). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2009.131r (2009).

Timoumi, R., Buratti, F. M., Abid-Essefi, S., Dorne, J. C. & Testai, E. Metabolism of triflumuron in the human liver: contribution of cytochrome P450 isoforms and esterases. Toxicol. Lett. 312, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.05.009 (2019).

Timoumi, R., Amara, I., Ayed, Y., Ben Salem, I. & Abid-Essefi, S. Triflumuron induces genotoxicity in both mice bone marrow cells and human colon cancer cell line. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 30 (6), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2020.1758981 (2020).

Shah, P. V. & Busschers, M. Triflumuron (toxicological evaluation only). In Pesticide Residues in Food 2022, 773 (2022).

Davis, P. H. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands (Edinburgh University, 1984). https://doi.org/10.2307/2806606.

Łukaszyk, A., Kwiecień, I. & Szopa, A. Traditional uses, bioactive compounds, and new findings on pharmacological, nutritional, cosmetic and biotechnology utility of Capsella bursa-pastoris. Nutrients 16 (24), 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244390 (2024).

Cha, J. M. et al. Phenolic glycosides from Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik and their anti-inflammatory activity. Molecules 22(6), 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22061023 (2017).

Hasan, R. N. Antibacterial activity of aqueous and alcoholic extracts of Capsella bursa against selected pathogenic bacteria. Available SSRN. 4779431 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4779431 (2024).

Kuroda, K. & Akao, M. Antitumor and anti-intoxication activities of fumaric acid in cultured cells. Gann = Gan. 72 (5), 777–782 (1981).

Grosso, C. et al. Chemical composition and biological screening of Capsella bursa-pastoris. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 21, 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000107 (2011).

Karageçili, H. et al. Evaluation of the Antioxidant, antidiabetic and anti-alzheimer effects of Capsella bursa-pastoris-polyphenolic profiling by LC-MS/MS. Rec Nat. Prod. 18 (6). https://doi.org/10.25135/rnp.489.2410.3353 (2024).

Riaz, I., Bibi, Y. & Ahmed, N. Evaluation of nutritional, phytochemical, antioxidant and cytotoxic potential of Capsella bursa-pastoris, a wild vegetable from Potohar region of Pakistan. Kuwait J. Sci. 48 (3). https://doi.org/10.48129/kjs.v48i3.9562 (2021).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Macar, O., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Protective roles of grape seed (Vitis vinifera L.) extract against Cobalt (II) nitrate stress in Allium cepa L. root tip cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10532-6 (2021).

Pehlivan, Ö. C., Cavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E. & Acar, A. Silico interactions and deep neural network modeling for toxicity profile of Methyl methanesulfonate. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30 (55), 117952–117969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30465-0 (2023).

Kutluer, F., Özkan, B., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Direct and indirect toxicity mechanisms of the natural insecticide Azadirachtin based on in-silico interactions with tubulin, topoisomerase and DNA. Chemosphere 364, 143006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143006 (2024).

Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Toxicity assessment of potassium bromate and the remedial role of grape seed extract. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 20529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25084-7 (2022a).

Altunkaynak, F., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Detection of heavy metal contamination in Batlama stream (Turkiye) and the potential toxicity profile. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 11727. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39050-4 (2023).

Sarsar, O. et al. Multifaceted investigation of esfenvalerate-induced toxicity on Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01638-3 (2025).

Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E., Türkmen, Z., Yapar, K. & Sağir, S. Physiological, anatomical, biochemical, and cytogenetic effects of Thiamethoxam treatment on Allium cepa (Amaryllidaceae) L. Environ. Toxicol. 27, 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.20680 (2012).

Yılmaz, H. et al. DNA fragmentation, chromosomal aberrations, and multi-toxic effects induced by nickel and the modulation of Ni-induced damage by pomegranate seed extract in Allium cepa L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 110826–110840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30193-5 (2023).

Kaydan, D., Yagmur, M. & Okut, N. Effects of Salicylic acid on the growth and some physiological characters in salt stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L). JAS 13 (2), 114–119 (2007).

Witham, F. H., Blaydes, D. F. & Devlin, R. M. Experiments in Plant Physiology. Van Nostrand, New York, 245 pp. (1971).

Himtaş, D., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. In-vivo and in-silico studies to identify toxicity mechanisms of permethrin with the toxicity-reducing role of ginger. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31 (6), 9272–9287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31729-5 (2024).

Dikilitaş, M. & Koçyiğit, A. Analysis of DNA damage in organizms via single cell gel electrophoresis (technical note): comet assay method. J. Fac. Agric. Harran Uni. 14 (2), 77–89 (2010).

Pereira, C. S. A. et al. Evaluation of DNA damage induced by environmental exposure to mercury in Liza aurata using the comet assay. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 58, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-009-9330-y (2010).

Yirmibeş, F., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Protective role of green tea against Paraquat toxicity in Allium cepa L.: physiological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and anatomical assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17313-9 (2022).

Gill, S. S. & Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 48 (12), 909–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016 (2010).

Apel, K. & Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 55 (1), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 (2004).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Acute multiple toxic effects of trifloxystrobin fungicide on Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 15216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19571-0 (2022).

Szabados, L. & Savouré, A. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant. Sci. 15 (2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.009 (2010).

Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Spectroscopic contribution to glyphosate toxicity profile and the remedial effects of Momordica charantia. Sci. Rep. 12, 20020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24692-7 (2022b).

Kurt, D., Acar, A., Çavuşoğlu, D., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Genotoxic effects and molecular Docking of 1, 4-dioxane: combined protective effects of trans-resveratrol. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28 (39), 54922–54935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14387-3 (2021).

Aydin, D., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Metal chelating and anti-radical activity of Salvia officinalis in the ameliorative effects against uranium toxicity. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 15845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20115-9 (2022).

Dennery, P. A. Effects of oxidative stress on embryonic development. Birth Defects Res. Part. C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 81 (3), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrc.20098 (2007).

Topatan, Z. Ş. et al. Alleviatory efficacy of Achillea millefolium L. in etoxazole-mediated toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 14, 31674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81586-6 (2024).

Çavuşoğlu, D., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Mitigative effect of green tea extract against mercury (II) chloride toxicity in Allium cepa L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(19), 27862–27874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17781-z (2022).

Macar, T. K., Macar, O., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Resveratrol ameliorates the physiological, biochemical, cytogenetic, and anatomical toxicities induced by copper (II) chloride exposure in Allium cepa L. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27 (1), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06920-2 (2020).

Choudhary, A., Kumar, A. & Kaur, N. ROS and oxidative burst: roots in plant development. Plant. Divers. 42 (1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2019.10.002 (2020).

Bıyıksız, G., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. A study investigating the multifaceted toxicity induced by triflumuron insecticide in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 24839. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10777-6 (2025).

Kesti, S., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Investigation of the protective role of Ginkgo biloba L. against phytotoxicity, genotoxicity and oxidative damage induced by trifloxystrobin. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 19937. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70712-z (2024).

Crouzet, O. et al. Soil photosynthetic microbial communities mediate aggregate stability: influence of cropping systems and herbicide use in an agricultural soil. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01319 (2019).

Crouzet, O. et al. Impact écotoxicologique d’un antibiotique sur les processus microbiens du cycle de l’azote, dans des sols amendés par des produits résiduaires organiques. In 3èmes Journées d’Écotoxicologie Microbienne (2016).

Üst, Ö. et al. A multidimensional study on the effects of Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench extract in uranyl acetate-exposed Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 15, 26565. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03777-z (2025).

Üstündağ, Ü., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Comparative analysis of cyto-genotoxicity of zinc using the comet assay and chromosomal abnormality test. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 56140–56152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-34940-0 (2024).

Dona, M., Macovei, A., Fae, M., Carbonera, D. & Balestrazzi, A. Plant hormone signaling and modulation of DNA repair under stressful conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 32(7), 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-013-1410-9 (2013).

Georgieva, M. & Vassileva, V. Stress management in plants: examining provisional and unique dose-dependent responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (6), 5105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065105 (2023).

Sharma, P., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S. & Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012 (1), 217037. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/217037 (2012).

de Barros, A. L. et al. Genotoxic and mutagenic effects of diflubenzuron, an insect growth regulator, on mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health- A. 76 (17), 1003–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2013.830585 (2013).

Kesti Usta, S., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Synergistic and antagonistic contributions of main components to the bioactivity profile of Anethum graveolens extract. Sci. Rep. 15, 21465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21465https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07297-8 (2025).

Ayhan, B. S., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. In-silico receptor interactions, phytochemical fingerprint and biological activities of Matricaria chamomilla flower extract and the main components. Sci. Rep. 15, 28875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14729-y (2025).

Akgeyik, A. U., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Phytochemical fingerprint and biological activity of Raw and heat-treated Ornithogalum umbellatum. Sci. Rep. 13, 13733. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41057-w (2023).

Üst, Ö., Yalçın, E., Çavuşoğlu, K., Özkan, B. & LC–MS/MS GC–MS and molecular Docking analysis for phytochemical fingerprint and bioactivity of Beta vulgaris L. Sci. Rep. 14, 7491. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58338-7 (2024).

Tenhaken, R. Cell wall remodeling under abiotic stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 5, 771. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00771 (2015).

Farooq, M., Wahid, A., Kobayashi, N. S. M. A., Fujita, D. B. S. M. A. & Basra, S. M. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. In Sustainable agriculture Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. 153–188 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2666-8_12

Fennell, B. J. et al. Microtubules as antiparasitic drug targets. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 3 (5), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.3.5.501 (2008).

Bajguz, A. & Piotrowska, A. Conjugates of auxin and cytokinin. Phytochemistry 70 (8), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.006 (2009).

Çavuşoğlu, K., Kurt, D. & Yalçın, E. A versatile model for investigating the protective effects of Ceratonia siliqua pod extract against 1, 4-dioxane toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27 (22), 27885–27892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08545-2 (2020).

Demirtaş, G., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Aneugenic, clastogenic, and multi-toxic effects of diethyl phthalate exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27 (5), 5503–5510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07339-5 (2020).

Liu, Q., Luo, L. & Zheng, L. Lignins: biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020335 (2018).

Boerjan, W., Ralph, J. & Baucher, M. Lignin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 54, 519–546. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938 (2003).

Touzout, N. et al. Deciphering the mitigating role of silicon on tomato seedlings under lambda cyhalothrin and Difenoconazole co-exposure. Sci. Rep. 15, 26512. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12123-2 (2025).

Lagunas-Rangel, F. A. & Bermúdez-Cruz, R. M. Natural compounds that target DNA repair pathways and their therapeutic potential to counteract cancer cells. Front. Oncol. 10, 598174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.598174 (2020).

Ahmad, S., Tan, M. L. & Hamid, S. DNA repair mechanisms: exploring potentials of nutraceutical. J. Funct. Foods. 101, 105415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2023.105415 (2023).

Kaur, J. & Kaur, R. p-Coumaric acid: A naturally occurring chemical with potential therapeutic applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 26 (14), 1333–1349. https://doi.org/10.2174/1385272826666221012145959 (2022).

Kim, H. P., Son, K. H., Chang, H. W. & Kang, S. S. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 96 (3), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1254/jphs.CRJ04003X (2004).

Pei, K., Ou, J., Huang, J. & Ou, S. p-Coumaric acid and its conjugates: dietary sources, Pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96 (9), 2952–2962. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7578 (2016).

Chua, L. S. A review on plant-based Rutin extraction methods and its Pharmacological activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 150 (3), 805–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.036 (2013).

Ganeshpurkar, A. & Saluja, A. K. The Pharmacological potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 25 (2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2016.04.025 (2017).

Onea, S. G. et al. Histological research and phytochemical characterization of Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik. From Bihor County. Romania Life. 15 (1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15010067 (2025).

Sipahi Kuloğlu, S., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. LC–MS/MS phenolic profile and remedial role of Urtica dioica extract against Li₂CO₃-induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 54589–54602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-34791-9 (2024).

Kutluer, F., Güç, İ., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Toxicity of environmentally relevant concentration of esfenvalerate and Taraxacum officinale application to overcome toxicity: a multi-bioindicator in-vivo study. Environ. Pollut. 373, 126111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2025.126111 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study has not been financially supported by any institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K: investigation; methodology; visualization; writing-review and editing. F.K.: investigation; methodology; visualization; writing-review and editing.E.Y: conceptualization; methodology; data curation; software; visualization; writing-review and editing.K.Ç: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing-review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information