Abstract

The leaves of Costus pictus have been reported to have anti-diabetic properties. Nevertheless, a comprehensive analysis of the entire plant remains to be established. The current objective was to assess the phytochemical content, antioxidant capacity and anti-cancer potential. Three fractions - hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol extract were obtained by sequential extraction. The various extracts were phytochemically screened and the effects on cell proliferation was evaluated on cancerous (A-549, HeLa, HT-29, and AGS) and non-cancerous (L-132 and L929) cell lines. C. pictus presented no significant toxic effect in normal cells whereas high cytotoxicity was observed in the stem ethyl acetate extract. The release of LDH and elevated expression of caspase-3, -8, and − 9 activities were observed following 48 h of treatment. Gallic acid, quercetin, kaempferol and rutin were identified by HPLC. Apoptotic inducing compounds like phytol and stigmasterol were also detected using GC-MS. Consequently, C. pictus may hold promise for medicinal applications given its capacity to cause cancer cells to undergo apoptosis. For the first time, our research showed that the stem ethyl acetate extract of C. pictus inhibited the development of HeLa and A-549 cells by activating caspase − 3, -8, and − 9 which can lead to programmed cell death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Costus pictus is a rhizomatous perennial upright, spreading herb reaching about two feet tall and is commonly known as ‘Painted spiral ginger’. It is a medicinally important plant that belongs to the family Costaceae1. It can be found all across the world’s tropical regions. In India, it is prevalent in parts of central India, the sub-Himalayan range, and the Western Ghats2. Known as the “insulin plant,” C. pictus was brought to India from America recently as a medicinal remedy for diabetes3. This plant is particularly noted for its ability to help manage diabetes, as its leaves are consumed to lower blood glucose levels. In South India, it is commonly planted as a decorative plant in gardens and can also be found growing wild in various locations4. In addition to its anti-diabetic effects, C. pictus has been identified to possess a range of therapeutic benefits, including antimicrobial, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory properties. Its rich phytochemical profile makes it a valuable asset in traditional medicine and is also employed to promote long life, treat rashes, lower fever, treat asthma, treat bronchitis and get rid of intestinal worms5,6,7,8. The tribal inhabitants of the Kolli Hills in the Namakkal district of Tamil Nadu have long used the leaves of C. pictus as one of the plants that effectively treat diabetes. The aerial portion of C. pictus is used as an infusion to treat renal diseases in Mexican traditional medicine8,9. In Southeast Asia, it is used to alleviate diarrhoea, headaches, and illness and the Japanese people used it to treat syphilis. In India, it is utilised for the treatment of pneumonia and rheumatism3. Studies on the possible medical benefits of C. pictus have gained significance since it was brought to India from the Americas10.

In 2022, there were about 10 million cancer-related deaths and nearly 20 million new cases worldwide. By 2050, there will be 35 million new instances of cancer annually, a 77% rise from 2022 levels, according to demographic projections11. The Indian Council of Medical Research (IMCR) and the National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) 2012–2016 report published a report that revealed that, in comparison to non-Asian nations, Asia’s Aizawl district has the highest incidences of stomach cancer in men and lung cancer in women.

The country’s highest rate of colon cancer in both men and women was also found in the Aizawl district of Mizoram. Compounds that can induce cancer cell death by apoptosis are highly desired since this process destroys cancerous cells while leaving surrounding normal cells and tissues intact12. The potential advantages of natural chemicals in cancer chemotherapy and radiation therapy are implied by their capacity to destroy cancer cells and restore medication sensitivity13,14. Therefore, apoptosis has been the subject of much research because of the strong relationship between its mechanism and the impact of anticancer drugs15. The most common cancer sites in India, especially in North-East India, were determined to be lung, cervical, gastric, and colon cancer16. Accordingly, four human cancer cell lines- A-549 (lung), HeLa (cervical), AGS (gastric), and HT-29 (colon)—as well as normal human lung cells L-132 and a mouse fibroblast - L929 cells were used in this study to examine the cytotoxic effect and mode of action. The principle objective of this study was to examine how C. pictus affects different cancer cells and non-cancerous cells, and to investigate the possible mechanism of action involved in this effect.

The literature review revealed that, to the best of our knowledge, no research has compared the anti-cancer properties of C. pictus leaves, stems, and rhizomes from a high-altitude, mountainous, tropical wet evergreen forest in Mizoram. Given the high rate of cancers, the current study focused on describing the anticancer potential of C. pictus, a plant that the few indigenous people underutilise, yet universally acknowledge as a functional dietary ingredient. Our findings indicate that the stem ethyl acetate extract of Costus pictus has significant and safe anti-cancer properties with negligible cytotoxic damage to healthy cells. The current research supports the use of traditional herbs to treat cancer and opens the door for the creation of novel therapeutic molecules, including a possible lead natural compound for cancer chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant sample and extract Preparation

A collection of uninfected Costus pictus D.DON (Family: Costaceae) was made in May 2022 from Durtlang, Mizoram, India (23.7833°N, 92.7333°E; WGS84). The plant material was collected from a private garden in Durtlang, Aizawl where the plant have been cultivated for many years for traditional medicine. The plant was then propagated and multiplied for this research study. Required permissions were obtained for collection and propagation of the plant from the owner of the garden in Durtlang, Aizawl. Dr. Khomdram Sandhyarani Devi, from the Department of Botany, Mizoram University verified the authenticity of the plant sample. The herbarium was placed at the Mizoram University, Institutional Herbarium using voucher number MZUH00035. After cleaning with water and allowed to air dry, the plant sample was ground into a fine powder using an electric grinder. Using solvents of increasing polarity, specifically hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol, the powder sample was cold extracted one after the other. Continuous stirring was used to extract the samples at 37 °C until the solvent turned colourless. The extract samples were kept at -20 °C until they were needed again after being filtered and dried in a rotary evaporator. The methanol, hexane, and ethyl acetate extracts from the leaves, stem, and rhizome were recorded as: RH- Rhizome Hexane, SH- Stem Hexane, LH- Leaf Hexane, RE- Rhizome Ethyl acetate, SE- Stem Ethyl acetate, LE- Leaf Ethyl acetate, RM- Rhizome Methanol, SM- Stem Methanol and LM- Leaf Methanol.

Chemicals

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), High glucose: Cell culture tested, sterile filtered, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. D5796; (Darmstadt, Germany), HAM’S F-12: Cell culture tested, sterile filtered; Sigma-Aldrich; Cat. No: N6658; (Darmstadt, Germany), Trypsin: cell culture tested, Cat. No. T4799; Sigma Aldrich, EDTA: Cat. No. E5134, Sigma Aldrich, Fetal Bovine Serum: F2442; cell culture tested, St. Louis, MO, USA, Sigma Aldrich, Amphotericin B: Cell culture tested; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A2942, Darmstadt, Germany), Penicillin-streptomycin: Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. P4333, Darmstadt, Germany, Potassium persulfate: ≥99.0%, ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. 216224, Darmstadt, Germany, Ascorbic acid: ≥99%, ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A92902, Darmstadt, Germany),Atropine: ≥98% HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A0132, Darmstadt, Germany), Quercitin: ≥95%, HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. Q4951, Darmstadt, Germany), Gallic acid: ≥98%, HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. G7384, Darmstadt, Germany), NBT: ≥98%, cell culture tested; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. N6876, Darmstadt, Germany), Ammonium molybdate: ≥99%, ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. 431346, Darmstadt, Germany), FeSO4: ≥99%, ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. F8633, Darmstadt, Germany), H2SO4: 95–98%, ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. 339741, Darmstadt, Germany, Sodium salicylate: ACS reagent grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. 247588, Darmstadt, Germany), MTT: ≥97.5%, cell culture tested; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. M5655, Darmstadt, Germany), Kaempferol: ≥98%, HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. K0133, Darmstadt, Germany), Rutin: ≥94%, HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. R5143, Darmstadt, Germany), DMSO: ≥99.9%, cell culture tested; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. D2650, Darmstadt, Germany), DPPH: ≥95% HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. D9132, Darmstadt, Germany), ABTS: ≥98%, spectrophotometric grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A1888, Darmstadt, Germany ,

Cell lines and culture medium

Four human cancer cells namely: A-549, HeLa, AGS, HT-29 and two normal cells: human lung-L-132 and a mouse fibroblast- L929 cells were purchased from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS) in Pune, India. Prior to distribution, all human cell lines procured from NCCS, a WHO reference centre and ICMR-recognized national cell repository, were subjected to short tandem repeat (STR) profiling, mycoplasma testing, and quality control to confirm their authenticity and contamination free condition. Stock cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 µg of amphotericin B per millilitre, 100 µg streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL penicillin. HAM’S F-12 media was used for culturing HT-29 cells. As the cells reached confluence, they were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2. Using a trypsin solution (0.2% trypsin, 0.02% EDTA, and 0.05% glucose in PBS), the cells were detached. 96 well microtitre plates were used for each experiment, and 25 cm2 culture flasks (Tarsons India Pvt. Ltd., India) were used to cultivate the stock cultures.

Phytochemical analysis

The various extracts of C. pictus were subjected to a qualitative phytochemical analysis in order to identify flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, phenol, terpenoid, saponin, quinone, cardiac glycosides, and anthraquinone in the plant17,18,19. A selected quantitative analysis of the alkaloid content20, flavonoid21 and phenol22 were conducted and the results were presented as the corresponding equivalents of atropine, quercetin and gallic acid respectively.

Antioxidant activity free radical scavenging activity

DPPH scavenging assay

The various extract concentrations were mixed with a 1 mL solution of 0.1 mM DPPH. After 30 min of incubation, absorbance was measured at 523 nm as outlined by Leong and Shui23. Ascorbic acid was used as standard at the concentration of 1–25 µg/mL.

ABTS scavenging assay

One mL of distilled water was mixed with 37.5 mg of potassium persulfate. 9.7 mg of ABTS and 44 µL of this solution were combined with 2.5 mL of distilled water. The solution was stored in a dark, room temperature environment for sixteen hours. The wavelength of absorbance was 734 nm24. Ascorbic acid was used as standard at the concentration of 1–25 µg/mL.

Superoxide anion scavenging assay

About 0.2 mL of NBT and 0.6 mL of the various extracts were added and the final volume of 2.8 mL was obtained by adding 2 mL of alkaline DMSO (as the blank). At 560 nm, the absorbance was measured. This protocol was a minor modification of Hyland et al.25 Gallic acid was used as standard at the concentration of 1–25 µg/mL.

Phosphomolybdenum assay

One mL of the reagent solution (0.6 M sulphuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate) was mixed with an aliquot of 0.1 mL of each extract. Ninety minutes of incubation at 95 °C in a water bath was performed and after cooling to room temperature, the samples were examined at 765 nm.26 Ascorbic acid was used as standard at the concentration of 1–25 µg/mL.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging assay

In order to measure the activity, Smirnoff and Cumbes27 were followed. 1.0 mL of 1.5 mM FeSO4 was added to 0.7 mL of 6 mM hydrogen peroxide,. This was followed by the addition of various extract strengths and 0.3 mL of 20 mM sodium salicylate to create a 3 mL reaction mixture. followed by an hour of incubation at 37 °C. Ascorbic acid was used as standard at the concentration of 1–25 µg/mL.

Screening for cytotoxicity potential of various extracts

Out of the nine samples, the extract with the strongest cytotoxic impact was chosen using the MTT assay. The stem ethyl extract of C. pictus had the best overall cytotoxic impact based on the IC50 values. The subsequent studies were conducted using the various stem extracts, and the cell cultures were split into the following groups:

-

MEM group: As a negative control, the cells in this group were not treated.

-

Dox group: As a positive control, the cells were exposed to doxorubicin at an IC50 concentration.

-

Treated group: The IC50 concentrations of the following extracts were applied to cells.

-

1.

SH-Stem hexane.

-

2.

SE-Stem ethyl acetate.

-

3.

SM-Stem methanol.

-

1.

MTT assay

The in vitro anticancer activity of C. pictus extracts was evaluated against A-549, HeLa, AGS, and HT-29 cancer cell lines, and cytotoxicity was also assessed in normal cell lines (L-132 and L929) using the MTT method28. In short, 96-well plates were seeded with 1 × 104 cells per well in 100 µL of minimal essential medium (MEM) and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2 atmosphere in 95% humidified air). After this cell plating period, the cells were treated with extracts at varying concentrations of 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 µg/mL or with doxorubicin at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL, and incubated for 48 h. Following treatment, 20 µL of MTT was added to each well and the microplates were incubated for two hours to allow formazan crystal formation. After removing the medium, the insoluble crystals were dissolved in DMSO and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 hours. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm and percentage cytotoxicity was calculated relative to untreated controls.

Controls and calculation

The positive control was doxorubicin, and the negative control was vehicle-treated cells (medium with the same final concentration of DMSO as in treated wells, ≤ 0.1% v/v), blank wells containing medium and MTT with no cells were added to account for background absorbance.

Cytotoxicity (%) was calculated as 100 × [1 − (absorbance of treated wells − absorbance of blank wells) / (absorbance of negative control wells − absorbance of blank wells)]28.

Neutral red uptake (NRU) assay

The neutral red uptake assay offers a quantitative assessment of the viable cells. For twenty-four hours, A-549 cells were treated with varying doses of SE while being incubated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL. A 1% neutral dye solution was added after incubation, and the mixture was incubated for three hours at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2. Following the removal of the dye and two PBS washes, the entrapped dye was dissolved inside the cell using a desorbing solution that contained 100 µL of each of 1% glacial acetic acid and 50% ethanol. The wells were incubated for 30 min in the dark. The solubilised dye’s absorbance was measured using spectrophotometry at 540 nm (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., USA)29.

Cytotoxicity LDH assay in A-549 and HeLa cell line

The amount of LDH leakage present in the culture media was used to evaluate the membrane’s integrity. We used the Pierce™ LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific™, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) to perform the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay in order to verify the cytotoxicity of SE. In summary, the MTT assay was used to treat A-549 and HeLa cells with SE at varying doses over 48 h. Following a 24-hour incubation period at 37 °C, 90% relative humidity, and 5% CO2, the culture media was aspirated and centrifuged for five minutes at 4000 rpm. To measure the LDH activity, the supernatant of treated A-549 and HeLa cells was put into a 96-well plate. Sodium pyruvate was used as a reference. The cells were exposed to 100 µL of the LDH reaction solution for 30 min. The absorbance at 420 nm was used to measure the red colour intensity displaying the LDH activity using a Tecan Infinite®200 Pro (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) microplate reader. The percentage of positive control was used to represent the amount of LDH released from treated cells. Calculations were made using the triplicate results of the experiments. In culture media, 1% Triton X-100 was applied to the positive control cells that were utilised to demonstrate total LDH leakage. As directed by the kit, the LDH levels in the media were measured and contrasted with control values.

Measurement of caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase 9 enzyme activation

ELISA kits (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, China) were used to assess the activity of caspase-3, -8, -9 by the colorimetric assay at 405 nm. A-549 and HeLa cells were treated with SE at an IC50 value for 48 h in order to induce apoptosis. The positive control was doxorubicin (10 µg/mL). Caspase-3, -8, -9 activity fold increases were analysed by directly comparing them to the level of untreated controls.

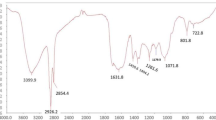

GC/MS analysis

GC/MS analysis was performed using a 123.5 m x 678 m Elite 1 (100% Dimethyl Poly Siloxane) capillary column and a Clarus 690 Perkin/Elmer (Autosystem XL) Perkin Elmer Turbomass 5.1 spectrometer with gas chromatograph mass detector and turbo mass gold. The temperature was set to 40 °C, ramped up to 115 °C in 5 min, held for 5 min, ramped up to 140 °C in 5 min, held for 5 min, ramped up to 210 °C in 2 min, held for 8 min, and sustained for 3 min. The oven temperature was raised to 250 °C at a rate of 5 °C per minute for nine minutes. While the helium flow rate was kept at 1.5 mL/min, the injection port temperature was kept at 250 °C. The ionisation voltage was fixed at 70 eV and 10:1 split mode was used for the injection of the samples. The range for the mass spectral scan was 500–800 (m/z). While the interface was maintained at 240 °C, the ion source was guaranteed to be at 230 °C. Three minutes marked the beginning of the MS, seventy-five minutes marked its conclusion, and three minutes marked the solvent cut. These substances were compared to NIST 17 online library Ver. 2.3 and PubChem Compound (NCBI)30,31,32.

HPLC-DAD analysis

A diode array detector (DAD, SPD N 20 A) and a C18 column (5 μm; 4.6 × 250 mm) used by Shimadzu Instrument (Shimadzu Corp, Kyoto, Japan) to identify the secondary metabolites. The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C during the analysis. By using the chromatographic conditions, the analytical process was completed. At 0.1 min, the gradient system started with a 100% solvent A concentration. Over the next 25 min, the concentration of solvent B was gradually raised to 35%, then to 50%, and finally to 100% in 65 min. 20 µL of the standard compounds were eluted after they were dissolved in sterile water and filtered using PVDF (0.45 μm). The solvent system used as the mobile phase consisted of Solvents A and B which are HPLC grade water and HPLC grade water : acetonitrile : acetic acid (48:51:4 v/v), respectively. The analysis involved injecting 20 µL of the sample while maintaining a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The retention periods for the reference compounds- kaempferol, gallic acid, quercetin and rutin- were determined by discrete analysis33,34.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2010 in Washington, USA was used to do the statistical analysis. Graph Pad Prism 7 software (California, USA) was used to determine the IC50. Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was performed after a one-way ANOVA was used to analyse the experimental data. When the P value was less than 0.05, it was deemed statistically significant. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate measurements.

The findings are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of measurements made in triplicate.

Results

Qualitative phytochemical analysis

A wide range of phytochemicals were identified by the qualitative phytochemical examination of the various extracts. The extracts contained the following important phytochemical components: phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, cardiac glycosides, saponins, quinones, and tannins (Supplementary Table 1). It was found that the hexane extracts lacked alkaloids, and all of the extracts lacked anthraquinone.

Quantitative phytochemical analysis

According to the phytochemical measurement of the different plant sections of C. pictus, LM had the highest phenol content (7.62 mg GAE/g of dry weight), followed by LE (4.65 mg GAE/g of dry weight). The content of flavonoid in LH was 2.87 mg quercetin equivalent/g of dry weight, whereas that of LM was the highest at 4.37 mg. According to Supplementary Table 2, LM had the highest alkaloid concentration (1.05 mg atropine equivalents/g of dry weight).

Antioxidant activities

Several in-vitro tests and the phosphomolybdenum assay were used to confirm the antioxidant activity of the various extracts. DPPH and ABTS+, superoxide, and hydroxyl tests were used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Antioxidant activity of Costus pictus extracts. Bar graphs show IC₅₀ values (µg/ml, mean ± SD, n = 3) of leaf, stem, and rhizome extracts of C.pictus (A) DPPH radical scavenging assay, (B) ABTS radical cation decolorization assay, (C) superoxide anion (O₂⁻) scavenging assay, (D) hydroxyl radical (·OH) scavenging assay, and (E) phosphomolybdenum antioxidant capacity assay. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Lower IC₅₀ values denote stronger antioxidant activity.

DPPH free radical scavenging activity

As illustrated in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3, the DPPH scavenging activity of C. pictus extracts increased as concentration increased (5–100 µg/mL). Scavenging was successful in the following order: SM (9.06 ± 0.07) > LM (20.89 ± 0.3) > RE (24.61 ± 0.04) > RH (44.33 ± 0.14) > RM (56.66 ± 0.7) > SH (90.17 ± 1.5) > LH (114.7 ± 0.02) > SE (115 ± 0.02) > CPLE (174.2 ± 0.28) in relation to ascorbic acid (01.071 ± 0.016 µg/mL).

ABTS + cations scavenging activity

The ABTS + cations scavenging of the C. pictus extracts increased in activity as concentration increased (5–100 µg/mL). The following is how the scavenging action worked: Ascorbic acid (1.31 ± 0.006 µg/mL) was compared to LE (5.23 ± 0.12), SH (15.45 ± 0.7), LM (15.81 ± 0.23), RH (28.07 ± 0.12), LH (30.07 ± 0.5), RM (44.11 ± 0.8), SM (67.37 ± 0.05), SE (79.14 ± 0.15), and RE (93.02 ± 0.14). (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Superoxide anion scavenging assay

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3 illustrates how the superoxide scavenging activity of C. pictus extracts increased as concentrations increased (5–100 µg/mL). It was revealed that the extracts’ scavenging activity decreased in the following order: LM (70.06 ± 0.7) > LE (86.43 ± 0.32) > LH (90.05 ± 0.73) > SE (90.86 ± 0.8) > RH (121.5 ± 0.5) > SM (134.9 ± 1.2) > RM (149.1 ± 0.5) > RE (160.7 ± 3.02) > SH (176.1 ± 3.04) with regard to Gallic acid (8.51 ± 0.31 µg/mL).

Hydroxyl radical scavenging assay

The hydroxyl scavenging activity of C. pictus extracts increased as concentrations increased (5–100 µg/mL). In the following order, the scavenging activity was successful: SH (1.55 ± 0.05) > SM (2.35 ± 0.8) > SE (4.2 ± 0.7) > LM (4.25 ± 1.07) > LH (4.62 ± 0.52) > RH (5.06 ± 1.2) > RE (6.34 ± 0.8) > LE (9.184 ± 0.05) > RM (9.72 ± 0.07) with respect to ascorbic acid (0.85 ± 0.018 µg/mL) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Phosphomolybdenum assay

Using the phosphomolybdate technique, the extracts’ overall antioxidant capacity was assessed. Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3 illustrates how the extracts of C. pictus showed an increase in activity of their total antioxidant capacity when concentrations increased from 5 to 100 µg/mL. The identified IC50 value order: RM (1.36 ± 0.05) > LH (23.42 ± 0.07) > RH (43.98 ± 0.05) > LM (44.56 ± 0.28) > SE (68.19 ± 0.15) > LE (70.93 ± 0.08) > RE (77.83 ± 0.55) > SM (82.6 ± 0.20) > SH (117.1 ± 0.07) with respect to ascorbic acid (0.85 ± 0.018 µg/mL).

Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity analysis (IC50 values) of C. pictus extracts on human cancer and normal cell lines is shown in Table 1. According to the findings, the different extracts had negligible toxicity to normal (L-132) cells but were able to induce cancer cell death in A-549, HeLa, AGS, and HT-29 cells. The SE achieved an IC50 value of 82.62 µg/mL and showed no discernible cytotoxicity against the L-132 cell line49,50. Conversely, SE demonstrated noteworthy efficacy against A-549 and HeLa cells, as evidenced by its respective IC50 values of 25.09 µg/mL and 35.65 µg/mL. All cancer and normal cells had an IC50 value of 2–4 µg/mL for the positive control, doxorubicin, which had values of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL (Table 1).

Although the initial cytotoxicity of the leaf, stem and rhizome of C. pictus was studied in five cell lines (A-549, HeLa, AGS, HT-29, L-132), a more detailed viability (toxicity) of the stem of C.pictus was done using neutral red assay (NRU) in A-549 cells, followed by MTT assay in another normal L929 cells (Fig. 2). A typical bar chart of neutral red absorption demonstrates a dose-dependent increase in cytotoxicity in A-549 cells. The level of cytotoxicity was elevated at 5–100 µg/mL. The in vitro MTT cytotoxicity representative bar chart shows slight cytotoxicity reactivity in L929 cells with no significant decline in the number of viable cells. (Fig. 2). In contrast to the MTT experiment, where viable cells convert the yellow MTT tetrazolium salt to an insoluble purple formazan product, mostly within mitochondria, neutral red enters live cells and is maintained in the lysosomes. The neutral red assay may be more sensitive than the MTT assay, particularly for cells with low metabolic activity. According to Chiba et al.51, the MTT assay can be affected by some substances, whereas the neutral red assay is less vulnerable to certain interferences from unidentified molecules. As a result, additional tests were therefore used in this investigation.

Effect of SE on cytotoxicity and cell viability on A-549 and L929 cells. (A) Neutral red uptake representative bar chart shows dose dependent elevation in cytotoxicity in A-549 cells. The level of cytotoxicity was elevated at 5–100 µg/mL concentration. (B) The in vitro MTT cytotoxicity representative bar chart shows slight cytotoxicity reactivity in L929 cells with no significant decline in the number of viable cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed; significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus 5 µg/mL. Untreated wells (0 µg/mL) were not included; therefore, the lowest concentration tested (5 µg/mL) served as the baseline reference group for statistical comparisons.

LDH release induction by SE

L-lactate is oxidised to pyruvate by the stable cytosolic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). LDH enzyme is released into the culture media when the cell membranes are damaged, indicating that the membrane integrity has been compromised52. Therefore, the LDH test was also carried out as an additional indicator of A-549 and HeLa cytotoxicity in order to further establish the cytotoxic effect of SE on these cells (Fig. 3). The release of LDH into the incubation media following SE treatment indicated the cell-membrane disruption of A-549 and HeLa cells. The extract cytotoxic impact was found to be concentration-dependent based on the LDH release curve for A-549 and HeLa cell lines treated with 50 and 100 µg/mL doses of SE (Fig. 3). With an IC50 of 25.09 g/mL for A-549 cells and 35.65 µg/mL for HeLa cells, respectively, cell viability was assessed using the LDH assay. Compared to cells treated with SE, the LDH standard, sodium pyruvate, induced a greater activity of LDH in A-549 cells (R2 = 0.997, ***p < 0.001), while treatment with the SE resulted in a significant dose-dependent increase in LDH release (R2 = 0.972, **p < 0.01) (Fig. 3). Similarly, in HeLa cells, the sodium pyruvate showed linearity (R2 = 0.988, ***p < 0.001), and treatment with SE induced a dose dependent rise in LDH activity (R2 = 0.953, **p < 0.01) The LDH significantly increased as the SE concentration rose. As the extract concentration rose, so did the cell line’s release of LDH.

SE and caspase-3, -8 and -9 activities

The apoptotic pathway’s cleaved effector caspase was examined by measuring the activation of caspase-3, − 8, and − 9 using a colorimetric test. According to the results, both HeLa and A-549 cells had higher caspase-3, -8, and − 9 activity than untreated cells. After A-549 cells were treated with SE, the caspase-3, -8, and − 9 activities were up-regulated by 5.25, 2.30, and 4.80-fold, respectively. HeLa cells exhibited a fold shift of 6.22, 2.42, and 5.57 for the cleavage of caspase-3, -8, and caspase-9 activity induced by SE, respectively. Consequently, SE increased the activities of caspase-3, -8, and − 9 in HeLa and A-549 cells, causing a cytotoxic impact by inducing apoptosis (Fig. 4).

GC-MS and HPLC analysis

According to the results, 10 compounds were found in SE (Table 2). According to peak retention duration and area (%), the GC-MS analysis of SH and SM yielded 6 and 15 peaks, respectively (Tables 3 and 4; Supplementary Fig. 1a-1c), when compared to known compounds in the NIST library and PubChem Compound (NCBI).

The HPLC analysis revealed that SH contained kaempferol and gallic acid (Fig. 5a). Three active ingredients were found in SE: rutin, quercetin, and gallic acid (Fig. 5b). The presence of gallic acid was seen in SM (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Normal body tissues and cells are nonetheless harmed by the cancer therapy procedure53. Furthermore, there are currently no effective medications that can completely eradicate cancer, and prolonged usage of some medications can cause tumour cells to develop drug resistance54. The goal of screening medicinal plants is to find potent anticancer drugs that can induce cancer cell death in human malignancies. Even with the incredible advancements in contemporary therapy, cancer is still a worldwide health issue, hence efforts are being made to find new alternatives. It has been recognised that nature is a wide and valuable source of potential chemotherapeutic medicines55. The almost infinite ability of plants to produce phytoconstituents draws researchers looking for novel and creative chemotherapeutics56. Finding novel anticancer substances in herbal treatments and traditional meals is an honest and fortunate way to prevent it57.

This study evaluated the phytochemical, antioxidant, and anti-cancer properties of C. pictus leaves, stem, and rhizome. According to supplementary Tables 1 and 2, the phytochemical content of C. pictus included phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, tannins, cardiac glycosides, saponins, and quinones. Antioxidant standards were chosen based on test chemistry and reactivity. The reference standard in the superoxide anion assay was gallic acid, a water-soluble phenolic with well characterised superoxide radical scavenging action. This choice is especially pertinent for extracts that are rich in phenolic compounds58,59. In contrast, ascorbic acid was used for the DPPH, ABTS, and phosphomolybdenum tests because it is widely used as a reference substance and has a consistent ability to reduce and quench radicals in both organic and aqueous systems26,60. The antioxidant tests in this study revealed complimentary pathways that provided a molecular basis for the observed anticancer effects, including hydroxyl radical neutralisation, reducing power (phosphomolybdenum), and radical scavenging (DPPH, ABTS). Moreover, HPLC profiling revealed the presence of gallic acid, quercetin, kaempferol, and rutin—compounds well known for their dual antioxidant and anticancer properties via cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis induction, and redox-sensitive pathway modulation61,62,63. Despite the correlation between antioxidant potency and cytotoxicity, the partial overlap indicates that the bioactivity may also be influenced by other processes, such as signalling interference and synergistic phytochemical interactions64,65.

A wide range of phytochemical substances, including alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, phenols, steroids, terpenoids, and flavonoids, were found in C. pictus66. When C. pictus leaves were sequentially screened for phytochemicals, Shankarappa et al.67 found that they were high in protein, iron, and antioxidants such ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, β-carotene, terpinoids, steroids, and flavonoids. Sathuvan et al.68 found that the chloroform extract of C. pictus stem had the highest antioxidant activity. When the concentration of the main antioxidants (phenol compounds) is low, they can work in synergy, and as a result, the other minor plant components may have a big impact on the variations in their total antioxidant activity.

The characteristics of medicinal plants, including their growth conditions, processing, and the amount and makeup of their antioxidants (phenolic substances including phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenes, carotenoids, and vitamins), all affect their antioxidant qualities69. Cytotoxic and persistent radical scavenging properties are directly linked to the phytochemical substances that are present70. As an analytical tool for chemotherapy71, the MTT test is widely used in the assessment of cytotoxic drug therapy.

The cytotoxicity of Costus pictus extracts varied significantly depending on the solvent and tissue, according to MTT screening. The most bioactive fractions were consistently found in the stem and rhizome fractions. The ethyl acetate stem extract demonstrated remarkable potency in A-549, HT-29, and HeLa, indicating that this solvent selectively enriches cytotoxic phytoconstituents. The methanol rhizome extract also demonstrated cytotoxic activity, especially against A-549, AGS, and HT-29 cells Similarly, the hexane rhizome and stem extracts exhibited potency in HeLa and HT-29 cells. On the other hand, extracts from leaves were typically less active in all solvents, indicating that active metabolites are localised in certain tissues. According to our study’s cytotoxicity results, the various extracts could induce cancer cell death but showed no damage to normal cells (L-132) (Table 1).

The substances that have the ability to eliminate cancer cells only while causing minimal harm to healthy cells are the most valuable72. The extracts in this investigation show decreased cytotoxicity against normal cells but are less effective than doxorubicin at inducing cancer cell death. Although doxorubicin is still very effective, the therapeutic use is limited by significant dose-dependent adverse effects, especially cardiotoxicity and myelosuppression due to non-selective cytotoxicity73,74. The extracts examined here, on the other hand, showed significant anticancer efficacy with less toxicity in normal cells, indicating a safer therapeutic effect. Although these extracts’ potency was not as high as that of doxorubicin, their lower risk of collateral damage makes them potentially useful adjuvants that could reduce chemotherapy doses while minimising side effects75. These findings thus provide credence to the traditional usage of this medicinal plant in the treatment of cervical cancer and lung cancer.

The NCI states that a plant extract with an IC50 value of ≤ 25 µg/mL50 and an incubation period of 48 to 72 h is thought to have an active cytotoxic action. According to the IC50 values, the stem ethyl acetate extract (SE) had the best overall cytotoxic impact. In this regard, the hexane, ethyl acetate, and rhizome extracts from the stem were used in the subsequent experiments. According to reports, all of the C. pictus stem extracts exhibit strong anti-cancer effects on HT 29 and A-549 cells76. The leaves of C. pictus have anticancer effects on breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7)77. The in vitro mammalian fibrosarcoma (HT-1080) cells showed anti-proliferative and anti-cancer potential when exposed to an ethanol extract of C. pictus leaves78. While normal lymphocytes showed no cytotoxic effects, fibrosarcoma cells showed anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects from the ethanol extract, even at lower doses. Owing to the existence of important biological characteristics, C. pictus became a crucial medicinal plant with significant therapeutic value.

The LDH assay is a test that determines how cytotoxic an anticancer drug is to cancer cells. Cell damage or lysis during necrosis and apoptosis causes the cytosolic enzyme LDH to be released into the surrounding culture media. LDH activity in any cell culture media might therefore be used to quantify cytotoxicity and serve as an indicator of the integrity and growth of cell membranes79,80. SE caused the activation of caspase − 3,-8 and − 9. A series of molecular steps leading to apoptosis are energy-dependent and entail caspase activation with a proteolytic impact at aspartic acid residues. According to current research, there are two main categories of caspases that are implicated in apoptosis pathways: initiators (caspase-2, − 8, −9, − 10) and executioners or effectors (caspase-3, − 6, −7)81. Their respective initiator caspases, caspase-9 and caspase-8, activate the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The activation of executioner caspases will follow the activation of initiator caspases. The untreated cells showed a low level of caspase-3 activity, which was likely caused by the negligible number of apoptotic cells in the expanding cell population. Through the cleavage of multiple vital cellular proteins, caspase-3 was discovered to be one of the execution caspases that significantly contributes to both intrinsic and extrinsic routes of apoptosis82. Cytomorphological alterations, including chromatin condensation, cell shrinkage, apoptotic body formation, and phagocytosis of the apoptotic cell are caused by the execution pathway83.

In the current work, we examined A-549 and HeLa cells treated for 48 h in order to determine whether SE can activate the caspases. The presence of their cleavage (Fig. 4) indicates that caspase-3, -8, and − 9 were activated following the 48-hour treatment. The underlying mechanism of apoptosis was revealed to be the intrinsic pathway by the elevated production of caspase-3 and caspase-9 cleavages. Furthermore, the identification of caspase-8 protein expression, a protein associated with the extrinsic pathway, which shows a smaller rise or fold change following SE treatment, further confirmed this conclusion.

Plant anticarcinogens can have a protective impact in a variety of ways because cancer is a complex disease. Phenol and flavonoid compounds are among the components that may prevent the development of cancer by influencing the molecular processes that occur during the stages of initiation, promotion, and advancement84. These bioactive substances have a well-established capacity to impede development and induce apoptosis. To get a thorough picture of all the metabolites in the extracts, profiling using a platform technique is necessary because each plant has a distinct metabolite fingerprint. The current study used two distinct methods of HPLC and GC-MS analysis to investigate the phytochemical components of the selected plants. The data is required to proceed with the substantial use of herbal plants as a source of pharmaceuticals or functional meals for the prevention or treatment of specific illnesses. According to the chromatographic techniques: Gallic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, and rutin were among the flavonoid and phenol components that were found in the majority, along with phytosterols like stigmasterol and a number of diterpene compounds like phytol (Tables 2, 3 and 4; Fig. 5). Many human cancer cells have been shown to undergo apoptosis when exposed to these substances via caspase-dependent mechanisms. As a result, it was demonstrated that C. pictus can cause A-549 and HeLa cells to undergo apoptosis by inducing the caspase cascade, an internal signalling mechanism.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this investigation, which included the cancer cells cytotoxicity, lactate dehydrogenase leakage, and activation of initiator and executioner caspases, indicated the anticancer potential of the ethyl acetate extract of C. pictus stem. The findings supported the first-ever report in this study that intrinsic pathways play a role in triggered apoptosis. Given that the data also demonstrated negligible cytotoxicity against normal cells, our conclusion validates the plant’s traditional use in the treatment of cancer. The anticancer effect may be ascribed to the chemicals (phenolics, flavonoids) found in this study. The first revelation to further substantiate SE’s therapeutic properties was the discovery by GC-MS that it contained anti-cancer chemicals (stigmasterol and phytol). Future developments in chemotherapy medication development and chemoprevention will create new opportunities for natural substances to reduce the impact of major malignancies on public health. To further confirm the effectiveness of these agents as strong anticancer agents, more preclinical research and clinical trials are undoubtedly still needed to clarify the entire range of cytotoxic activities of the selected natural compounds, either by themselves or in synergy with other small molecules.

Data availability

The first author can provide the datasets used or analysed in this study upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DPPH:

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- ABTS:

-

2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid

- O2 – :

-

Superoxide

- OH:

-

Hydroxyl radical

- IC50 :

-

Half- maximal inhibitory concentration

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide

- RH:

-

Rhizome Hexane

- SH:

-

Stem Hexane

- LH:

-

Leaf Hexane

- RE:

-

Rhizome Ethyl acetate

- SE:

-

Stem Ethyl acetate

- LE:

-

Leaf Ethyl acetate

- RM:

-

Rhizome Methanol

- SM:

-

Stem Methanol

- LM:

-

Leaf Methanol

References

Ami, N., Ramar, K. & Janardan, P. Comparative physicochemical and phytochemical evaluation for insulin plant-Costus pictus D. Don accessions. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Res. 3 (2), 420e426 (2017).

Selvakumarasamy, S., Rengaraju, B., Arumugam, S. A. & Kulathooran, R. Costus pictus–transition from a medicinal plant to functional food: A review. Future Foods. 4, 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100068 (2021).

Jose, B. & Reddy, L. J. Analysis of the essential oils of the stems, leaves and rhizomes of the medicinal plant Costus pictus from Southern India. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2 (2), 100–101 (2010).

Benny, M. Insulin plant in gardens. Nat. Prod. Radiance. 3, 349–350 (2004).

Ashwini, S., Bobby, Z., Joseph, M., Jacob, S. E. & Padmapriya, R. Insulin plant (Costus pictus) extract improves insulin sensitivity and ameliorates atherogenic dyslipidaemia in Fructose induced insulin resistant rats: molecular mechanism. J. Funct. Foods. 17, 749–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.06.024 (2015).

Prejeena, V., Suresh, S. N. & Varsha, V. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant analysis and antiproliferative effect of Costus pictus D. Don leaf extracts. Int. J. Recent. Adv. Multidiscip Res. 4, 2373–2378 (2017).

Raj, J. B. & Kalaivani, R. -vitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Costus pictus D. Don aqueous leaf extract. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 8 (8), 1107–1109. https://doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2018.8.0310502042018 (2018).

Elavarasi, S. & Saravanan, K. Ethnobotanical study of plants used to treat diabetes by tribal people of Kolli Hills, Namakkal District, Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Int. J. Pharm. Tech. Res. 4 (1), 404e411 (2012).

Comargo, M. E. M., Najera, C. R., Torres, R. S. & Alderate, M. E. C. Evaluation of the diuretic effect of the aqueous extract of costus pictus D. Don in rat. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 49, 72–74 (2006).

Hegde, P. K., Rao, H. A. & Rao, P. N. A review on insulin plant (Costus Igneus Nak). Phcog Rev. 8 (15), 67 (2014).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Ashkenazi, A. Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7 (12), 1001–1012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2637 (2008).

Tian, H. & Pan, Q. C. A comparative study on effect of two bisbenzylisoquinolines, tetrandrine and berbamine, on reversal of multidrug resistance. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 32 (4), 245–250 (1997).

Choi, S. U. et al. The bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids, tetrandine and fangchinoline, enhance the cytotoxicity of multidrug resistance-related drugs via modulation of P-glycoprotein. Anticancer Drugs. 9 (3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001813-199803000-00008 (1998).

Ocker, M. & Höpfner, M. Apoptosis-modulating drugs for improved cancer therapy. Eur. Surg. Res. 48 (3), 111–120 (2012).

Ngaihte, P., Zomawia, E. & Kaushik, I. Cancer in the NorthEast india: where we are and what needs to be done? Indian J. Public. Health. 63, 251–253 (2019).

Trease, G. E. & Evans, W. C. Pharmacognosy (11thed) 45–50 (Bailliere Tindall Ltd, 1989).

Harborne, J. B. Textbook of Phytochemical Methods, A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis (5th Edition.) 21–72Chapman and Hall Ltd, London, (1998).

Sofowora, A., Ogunbodede, E. & Onayade, A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. Afr. J. Tradit Complement. Altern. Med. 10 (5), 210–229 (2013).

Ainsworth, E. A. & Gillespie, K. M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2, 875-7. doi.10.1038/nprot.102 (2007). (2007).

Chang, C. C., Yang, M. H., Wen & Chern, H. M. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 10, 178–182 (2002).

Li, L. et al. Studies on quantitative determination of total alkaloids and Berberine in five origins of crude medicine Sankezhen. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 53, 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/chromsci/bmu060 (2014).

Leong, P. & Shui, G. An investigation of antioxidant capacity of fruits in Singapore markets. Food Chem. 76, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00251-5 (2002).

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Raic. Biol Med. 26, 1231-7. Doi.10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3 (1999).

Hyland, K., Voisin, E., Banoun, H. & Auclair, C. Superoxide dismutase assay using dimethylsulfoxide as superoxide aniongenerating system. Anal. Biochem. 135, 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(83)90684-x (1983).

Prieto, P., Pineda, M. & Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex:specific application to the determination of vitamin E1. Anal. Biochem. 269, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1999.4019 (1999).

Smirnoff, N. & Cumbes, Q. J. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of Compatible Solutes. Phytochem. 28, 1057–1060. Doi.10.1016/0031-9422(89)80182- 7. (1989).

Mossman, T. Rapid calorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxic assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 (1983).

Borenfreund, E. & Puerner, J. A. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol. Lett. 24, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4274(85)90046-3 (1985).

Adams, R. P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry 4th edn (Allured Publishing Corp, 2007).

NIST/EPA/NIH Mass. Spectral Library (NIST 17, Version 2.3) (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2017).

Stein, S. E. Mass spectral reference databases: an ever-expanding resource for chemical identification. Anal. Chem. 86, 7274–7287 (2014).

Zainol, M. K. et al. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of phenolic acids and flavonoids using gradient elution with aqueous acetic acid and acetonitrile. Int. J. Green. Pharm. 15, 100–110 (2021).

Akhtar, N. et al. Investigation of Pharmacologically important polyphenolic secondary metabolites in plant-based food samples using HPLC-DAD. Plants 13, 1311 (2024).

Bae, H., Song, G. & Lim, W. Stigmasterol causes ovarian cancer cell apoptosis by inducing Endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial dysfunction. Pharmaceutics 12 (6), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12060488 (2020).

Huange, Z., Xian, Z., Min, W., Yingying, L. & Songlin, Z. Stigmasterol Simultaneously Induces Apoptosis and Protective Autophagy by Inhibiting Akt/mTOR Pathway in Gastric Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol.11. doi.10.3389/fonc.629008. (2021). (2021).

Byju, K., Anuradha, V., Vasundhara, G., Nair, S. M. & Kumar, N. C. In vitro and in silico studies on the anticancer and apoptosis-inducing activities of the sterols identified from the soft coral, subergorgia reticulata. Pharmacogn. Mag. 10, 65–71. (2014). https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1296.127345. PMID: 24914311.

Bharath, B., Perinbam, K., Devanesan, S., AlSalhi, M. & Saravanan, M. Evaluation of the anticancer potential of hexadecanoic acid from brown algae Turbinaria Ornata on HT–29 colon cancer cells. J. Mol. Struct. 1235, 130229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130229 (2021).

Manivannan, P., Muralitharan, G. & Balaji, N. P. Prediction aided in vitro analysis of octa-decanoic acid from Cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. as a proapoptotic factor in eliciting anti-inflammatory properties. Bioinformation 13 (9), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.6026/97320630013301 (2017).

Fukuzawa, M. et al. Possible involvement of long chain fatty acids in the spores of Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi Houshi) to its anti-tumor activity. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (10), 1933–1937. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.31.1933 (2008).

To, N. B., Nguyen, Y. T., Moon, J. Y., Ediriweera, M. K. & Cho, S. K. Pentadecanoic Acid, an Odd-Chain fatty Acid, suppresses the stemness of MCF-7/SC human breast cancer Stem-Like cells through JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Nutrients 12 (6), 1663. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061663 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Heptadecanoic acid inhibits cell proliferation in PC-9 non-small-cell lung cancer cells with acquired gefitinib resistance. Oncol. Rep. 41 (6), 3499–3507. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2019.7130 (2019).

Yang, M. H. et al. Decanoic acid exerts its Anti-Tumor effects via targeting c-Met signaling cascades in hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancers (Basel). 15 (19), 4681. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194681 (2023).

Gliszczyńska, A. et al. Synthesis of novel phytol-derived γ-butyrolactones and evaluation of their biological activity. Sci. Rep. 11, 4262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83736-6 (2021).

Sakthivel, R., Malar, D. S. & Devi, K. P. Phytol shows anti-angiogenic activity and induces apoptosis in A-549 cells by depolarizing the mitochondrial membrane potential. Biomed. Pharmacother. 105, 742–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.035 (2018).

Baskaran, G., Salvamani, S., Ahmad, S. A., Shaharuddin, N. A. & Pattiram, P. D. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity and phytocomponent investigation of Basella Alba leaf extract as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 9, 509–517 (2015).

Jin, X. et al. Undecanoic acid, lauric acid, and N-Tridecanoic acid inhibit Escherichia coli persistence and biofilm formation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31 (1), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2008.08027 (2021).

Joshi, N., Sah, G. C., Mishra, D. & & GC-MS analysis and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Senecio pedunculatus. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 6, 61 (2013).

Kuete, V. Potential of Cameroonian plants and derived products against microbial infections: A review. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15, 286 (2015).

Geran, R. I., Greenberg, N. H., Mcdonald, M. M., Schumacher, A. M. & Abbott, B. J. Protocols for screening chemical agents and natural products against animal tumor and other biological systems. Cancer chemother. rep. 3, 17–19 (1972).

Chiba, K., Kawakami, K. & Tohyama, K. Simultaneous evaluation of cell viability by neutral red, MTT and crystal Violet staining assays of the same cells. Toxicol. Vitro. 12, 251–258 (1998).

Chan, F. K. M., Moriwaki, K. & Rosa, M. J. Detection of Necrosis by Release of Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity. In Immune Homeostasis. (Edited by Snow AL, Lenardo MJ) 65–70Humana Press, New York, (2013).

Cragg, G. M. & Pezzuto, J. M. Natural products as a vital source for the discovery of cancer chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive agents. Med. Princ Pract. 25, 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443404 (2016).

Chen, X. & Song, E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Reviews Drug Discov. 18 (2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1 (2019).

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 70 (3), 461–477 (2007).

Reed, J. C. & Pellecchia, M. Apoptosis-based therapies for hematologic malignancies. Blood 106 (2), 408–418 (2005).

Hu, Y. W. et al. Induction of apoptosis in human hepatocarcinoma SMMC-7721 cells in vitro by flavonoids from Astragalus complanatus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 123 (2), 293–301 (2009).

Lalhminghlui, K. & Jagetia, G. C. Evaluation of the free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of Schima wallichii Korth in vitro. Future Sci. OA. 4, FSO314 (2018).

Sadeer, N. B. et al. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety—chemistry, applications, limitations, and data analysis. Antioxidants 9, 709 (2020).

Untea, A. E., Varzaru, I. & Panaite, T. D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, and phosphomolybdenum assays for estimating antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in different plant extracts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 4749–4758 (2018).

Hong, J., Kim, J., Kim, H. & Lee, J. Gallic acid suppresses metastatic traits in MCF7 breast cancer cells under acidic conditions by inhibiting PI3K/Akt and β-catenin pathways. Nutrients 15, 3596. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163596 (2023).

Asgharian, A., Ghanbari, A., Mohammadi, R. & Khazaei, M. Quercetin in cancer prevention and therapy: a focus on mechanisms and clinical applications. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 2677. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-022-02677-w (2022).

Mahmud, S., Rahman, M. A., Sultana, R. & Chowdhury, M. Natural flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, rutin) as therapeutic agents: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer perspectives. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 47, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-01053-3 (2023).

Grigalius, I. & Petrikaitė, V. Relationship between antioxidant and anticancer activity of different extracts of Aronia melanocarpa. Phytomedicine 37, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.018 (2017).

Das, M. K., Singh, N. & Rajamani, P. Comprehensive assessment of the antioxidant and anticancer potential of selected ethnobotanical plants. Oxygen 3, 203–221. https://doi.org/10.3390/oxygen3020015 (2023).

Devi, V. D. & Urooj, A. Nutrient profile and antioxidant components of Costus specious Sm. and Costus Igneus Nak. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 1, 116–118 (2010).

Shankarappa, L., Gopalakrishna, B., Jagadish, N. R. & Siddalingappa, G. S. Pharmacognostic and phytochemical analysis of Costus ignitius. Int. pharm. sci. 1, 36–41 (2011).

Sathuvan, M. et al. In vitro antioxidant and anticancer potential of bark of Costus pictus D. Don. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2, 741–749 (2012).

Kulisic, T., Radonic, A., Katalinic, V. & Milos, M. Use of different methods for testing antioxidative activity of oregano essential oil. Food Chem. 85, 633–640 (2004).

Nurcholis, W., Khumaida, N., Syukur, M. & Bintang, M. Evaluation of free radical scavenging activity in ethanolic extract from promising accessions of curcuma aeruginosa RoxB. Molekul 12, 133. https://doi.org/10.20884/1.jm.2017.12.2.350 (2017).

Jiao, H. et al. Differential macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity to F388 leukemia cells and its drug-resistant cells examined by a new MTT assay. Leuk Res. 76, 1175–1180. Doi.10.1016/0022-1759(92)90331-m. (1992).

Malek, S. N. A., Shin, S. K., Wahab, N. A. & Yaacob, H. Cytotoxic components of Pereskia bleo (Kunth) DC. (Cactaceae) leaves. Molecules. 14, 1713– 1724. doi.10.3390/molecules14051713. (2009).

Vejpongsa, P. & Yeh, E. T. H. Prevention of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: challenges and opportunities. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 938–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1167 (2014).

Volkova, M. & Russell, R. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 7, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340311799960645 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Plant-derived compounds in combination cancer therapy: mechanisms and clinical applications. Pharmacol. Res. 186, 106552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106552 (2022).

Sathuvan, M. et al. Vitro antioxidant and anticancer potential of bark of Costus pictus D. Don. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2, 741–749 (2012).

Prejeena, V., Suresh, S. N. & Varsha, V. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant analysis and antiproliferative effect of Costus pictus D. Don leaf extracts. Int J. Recent. Adv. Multidiscip Res, 2373–2378. (2017).

Nadumane, V. K. et al. Evaluation of the anticancer potential of Costus pictus on fibrosarcoma (HT-1080) cell line. J. Nat. Pharm. 2, 72–76 (2011).

Fotakis, G. & Timbrel, J. An in vitro cytotoxicity assays: comparison of LDH, neutral red, MTT and protein assay in hepatoma cell lines following exposure to cadmium chloride. Toxicol. Lett. 160, 171–177 (2006).

Cummings, B. S., Wills, L. P. & Schnellmann, R. G. Measurement of cell death in mammalian cells. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 12 (128), 12–18 (2012).

Sui, Y. et al. Ethyl acetate extract from Selaginella doederleinii Hieron inhibits the growth of human lung cancer cells A-549 via caspase-dependent apoptosis pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 190, 261–271 (2016).

Porter, A. G. & Janicke, R. U. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell. Death Differ. 6 (2), 99–104 (1999).

Elmore, S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxic. Pathol. 35 (4), 495–516 (2007).

Kathiriya, A., Das, K., Kumar, E. P. & Mathai, K. B. Evaluation of antitumor and antioxidant activity of Oxalis corniculata linn. Against Ehrlich Ascites carcinoma on mice. Iran. J. Cancer Prev. 3 (4), 157–165 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Advanced Level State Biotech Hub (BT/NER/143/SP44475/2021) at Mizoram University, which is financed by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), New Delhi, Government of India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AZ designed the methodology and writing the original draft. LT contributed to the writing - Review & Editing. MV performed formal analysis, N.S.K provided resources required for the experiment, T.P was responsible for data acquisition, F.L Supervised the research work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

All authors confirm that this study did not involve any human participants or animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zohmachhuana, A., Vabeiryureilai, M., Tochhawng, L. et al. The stem ethyl acetate extract of Costus pictus D.DON exhibits cytotoxic activity in human cancer cells via. intrinsic apoptotic caspase pathway as a first report. Sci Rep 15, 42320 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26309-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26309-1