Abstract

Fermentation of plant-derived by-products, including rice polishings (RP), is suggested for the sustainability of the aquafeed industry. In this study, fermented rice polishings (FRP) were incorporated into Nile tilapia diets at various levels: 0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 g/kg. Nile tilapia with an average initial weight of 19.25 ± 0.25 g/fish were divided into five groups (triplicates) and fed five test diets (R0, R10, R20, R30, and R40) for 85 days. Dietary FRP substantially increased final body weight, weight gain, specific growth rate, and protein efficiency ratio, but decreased feed conversion ratio compared to the control group (R0). According to regression analysis, dietary FRP at 210 to 230 g/kg leads to optimal growth performance. Fish fed with higher levels of FRP (R20, R30, and R40) showed greater crude lipid content in the carcass compared to R0 and R10. Graded FRP levels considerably enhanced intestinal architexture, particularly at R20 and R30 levels. Fish fed FRP showed a dose-dependent increase in digestive enzyme activity up to 300 g/kg (R30), with the R20 having the greatest activity. Serum lysozyme levels increased significantly across all FRP levels. Serum immunoglobulin activity enhanced considerably in the R20 and R30 groups. R20 had the greatest lysozyme and immunoglobulin activity. Fish given graduated FRP levels had higher levels of total antioxidant capacity, SOD, and CAT compared to R0, with R20 exhibiting the greatest activity. Ultimately, dietary FRP can be added at 210–230 g/kg to enhance the growth performance, productivity, gut shape, digestive enzyme activity, blood health, immunity, and antioxidant response of Nile tilapia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global aquaculture sector has expanded to enhance food security and livelihoods, particularly in emerging economies where there is a growing demand for cost-effective and sustainable fish production1. Nile tilapia can withstand rigorous farming conditions, intensification, and rather poor water quality2. Nonetheless, Nile tilapia requires a specific number and quality of nutrients in order to achieve optimal growth performance, health, and production. Traditionally, fishmeal and soybean meal have served as the primary protein sources in Nile tilapia diets. However, their high prices, limited availability, and competition for human consumption restrict their use in aquafeed production3. Aquafeed contributes for 60–70% of the entire production costs in Nile tilapia farming4,5; hence, sustainable alternative feed ingredients are required. Integrating plant products rich in protein, fat, and minerals is crucial for the aquaculture feed industry6. The incorporation of plant by-products into feed formulations is constrained by limited availability of plant-based ingredients and their high costs7,8. The ongoing global conflicts, which have led to soaring prices of feed ingredients and additives, further emphasize the importance of exploring non-traditional feed materials for the sustainable aquaculture feed industry8. Among the many parts of rice grains are bran, hulls, and rice polishings, which are frequently utilized in animal feed. Rice polishing, a process that involves the removal of the outer layers of rice grains to enhance their appearance and shelf life, generates a significant byproduct known as rice polishings9,10. More precisely, rice polishings (RP) are the main by-product of brown rice milling, which consists of peel, aleurone layer, hypo aleurone layer, seed coat, nucellar layer, a small number of plumule and broken rice11. It is considered as a low-cost by-product with well-known health benefits, including high fiber (20%), high protein (14%) and fat (14.75%), as well as other carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and essential unsaturated fatty acids12. It also contains antioxidants like phenolics, tocopherols, tocotrienols, and γ-oryzanol13. Additionally, RP is becoming increasingly and more popular in the feed, pharmaceutical, and nutraceutical sectors because of its high nutritional content, affordability, accessibility, and potential for high bioactivity, as well as the related health advantages14. But because of a number of challenges with the processing, including raw ingredients that are prone to rancidity and poor functioning, it is still mostly utilized as feed15,16. Consequently, there is a growing research focus in cereal science on utilizing rice bran as a primary raw material for developing diverse nutritious feeds, improving the processing characteristics of rice polishings, and addressing the challenge of maintaining the freshness of rice polishings through modern feed processing technologies15. Here, it examines and forecasts rice polishings stabilization, fermentation, biological enzymolysis, the use of all rice polishings constituents in feed, and rice polishings processing in order to offer a guide for rice polishings processing and use in Nile tilapia feeding.

Materials and methods

Solid state fermentation of rice Polishings (SSF-RP)

The commercial rice polishing powder was fermented with baker’s yeast (S. cerevisiae; viable cell counts 1.5 × 1010 cell g− 1 SIGMA, Baker’s Yeast Type II) using the technique described by 17. In a 5 L glass Jar, 2 kg of RP + 66.6 mg dry yeast + 100 mL molasses + 1.6 L distilled water were added and then mixed for 15 min. The mixture was kept and the glass jar covered with aluminum foil at 30 °C for 72 h. After fermentation was completed, conventional sun drying was performed. 10 g of FRP was tested after 72 h of fermentation to determine the phytic acid according to 18 methedology before and after fermentation. Additionally, the chemical composition of RP before and after fermentation was estimated according to the19 methods.

Diets formulation

The formulation of five experimental diets that are isonitrogenous (28.5% crude protein) and isocaloric (19.07 MJ kg-1 gross energy) is fulfil the nutritional requirements of Nile tilapia according to NRC20 (Table 1). The first diet is the control diet (0%, free of FRP). The inclusion levels of FRP were 10%, 20% ,30 and 40% in the other four experimental diets. All dry ingredients were finely ground, accurately weighed, and manually premixed for 5 min. The mixture was then transferred to a mechanical food mixer and blended for an additional 15 min to ensure homogeneity. Soybean oil was gradually incorporated during this stage to achieve uniform distribution. The homogenized mixture was subsequently pelleted using a laboratory-scale pellet mill (California Pellet Mill, San Francisco, CA, USA) fitted with a 1.6–2.1 mm diameter die. The resulting pellets were air-dried at ambient temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 24 h to reduce moisture content. Finally, the dried pellets were packed in airtight laboratory-grade containers and stored at − 20 °C until use to preserve nutritional integrity.

Fish experiment

Healthy mono-sex Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus were purchased from a private farm, Tolmbat 7, Kafr El-Sheikh Government, Egypt. Throughout the acclimation period (two weeks), fish were fed the control diet (3% of total biomass), which provided equal quantities at 9:00, and 1:00 p.m. at the aquaculture lab of Animal Health Research Institute, Kafr El-Sheikh, Egypt. The feed was estimated at 28.5% crude protein and 5.7% crude lipid. Following acclimation, 300 healthy Nile tilapia were split into five groups, each with three replicates, and with a stocking density of 20 fingerling per glass tank (60 L capacity). The average weight of the fish was 19.25 ± 0.25 g. Dechlorinated tap water was used to fill the tanks and compressed air provided for oxygen requirements compressed air provided for oxygen requirements. Every day, around one-third of the water volume in each tank was renewed after the accumulation of excreta was cleaned and removed. Fish were fed twice daily (at 9:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m.) for 85 days. Throughout the trial, fish were weighed regularly to adjust feed quantities based on biomass in each tank.

Throughout the feeding trial, the water quality parameters that were measured were: temperature (23 ± 1.5 °C), pH (7.5 ± 0.7), dissolved oxygen (5.6 ± 0.3 mg/L), and ammonia (0.010–0.016 mg/L). These are considered to be ideal ranges for Nile Tilapia.

Growth and feed utilization measures

Fish were collected at the end of the feeding trial, counted, measured the length, and weighed. Growth performance and feed utilization metrics were determined using standard Reference formulae according to NRC20,21. The following equations were used to calculate the growth indices:

-

Weight gain (WG, %) = [(FBW – IBW) ×100] / IBW.

-

SGR: specific growth rate (%/day) = 100 × [ln final body weight (g) − ln initial body weight (g)]/duration of feeding (day).

-

FCR: feed conversion ratio = FI / WG.

-

FCE: feed conversion efficiency = live weight gain (g)/dry feed intake (g).

-

PER: protein efficiency ratio= [WG (g) ̸ PI (g)] × 100.

-

Survival (%) = 100 × (final number of fish/initial number of fish).

Randomly, five fish per tank were chosen and stored at − 20℃ until carcass proximate analysis was conducted.

Diet and carcass composition

For both diets and fish samples, a standard technique for determining the nutritional content of the test diets and the chemical content of the whole fish body was applied in triplicates for diets and fish samples (AOAC, 2016). Crude protein (N factor = 6.25) was analyzed via the Kjeldahl apparatus (Labconco, Labconco, Kansas, MO, USA). Crude fat was extracted using the Soxhlet extraction method (Lab-Line Instruments, Melrose Park, IL, USA). For the ash, samples were burnt in the Muffle furnace (Thermolyne Corporation, Dubuque, Iowa, USA) at 550 °C for 6 h while the moisture content was determined using oven-drying at 110 °C to reach the constant weight. The system used for detecting the amine acids profile was high performance Amino Acid analyzer (Biochrom 30).

Fish anesthesia and hematological analysis

After 24 h fasting, blood samples were obtained from the caudal vein of 5 fish anaesthetized with tricane methanesulfate (MS222 ; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) (150 mg/L, buffered with sodium bicarbonate to neutralize pH). Anesthesia depth was confirmed by loss of equilibrium, cessation of opercular movement, and absence of response to a tail pinch stimulus. Once fully anesthetized, blood samples were collected via caudal vein puncture, then deposited into heparinized and non-heparinized Eppendorf centrifuge tubes, according to 22. plasma and serum were obtained After Eppendorf centrifugation at 5000 rpm/15 min. In Plasma, Total hemoglobin (Hb), red blood cells (RBCs) and white blood cells (WBCs) were determined using Semi- automatic analyzer for clinical chemistry and hematology tests- Model 2000 Evolution, EMEG using Bayer Diagnostics Reagents strips following the manufactory guidelines. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were calculated using the method of Hawkey et al., 23.

The obtained serum was used for biochemical, immunological, and anti-oxidant analysis. Total cholesterol and triglyceride were assessed spectrophotometrically using an automated analyzer (SPOTCHEM™ EZ model SP-4430; ARKRAY, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) according to Tatsumi et al., 24. At a wavelength of 540 nm, calorimetric measurements were made of glucose, total protein levels, and the liver’s enzyme activity, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)25.

Following the blood sampling, the viscera and liver were then dissected out from the fish, individually weighed, and measured (length) to calculate the condition factor, viscerosomatic index, and hepatosomatic index using the following formulas: 1-Condition factor = fish weight/ (fish length) (cm) × 100. 2-Viscerosomatic index = viscera weight/fish weight × 100. 3-Hepatosomatic index = liver weight/fish weight × 100.

Gut morphology analysis

Fish were captured and anesthetized in a separate plastic container using clove oil (2–3 drops per liter of water) until fully sedated (2–3 min), following ARRIVE guidelines26. Once anesthetized, three fish per replicate tank were selected for intestinal morphology analysis. In accordance with standard ethical guidelines, cervical dislocation was performed to ensure death prior to dissection. The whole gastrointestinal tract were then aseptically collected, and the anterior, middle, and posterior parts of the intestine were taken, washed twice in twice in PBS (pH = 7.4), then were immersed in Davidson’s solution (agitated for 5 min) for 8 h. Following a progressive dehydration in ethanol (70%–100%), fixed tissues were twice cleaned with xylene (1 and 2 h)before being embedded in paraffin. 5-µm thickness Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under light microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a camera (Digital Sight DS2MV with a DS-L2 control unit; Nikon), with data analysed using SigmaScan Pro 5 software. Villi length, villi width, and goblet cell numbers were measured using Image J analysis software with magnifications of 100×, 200×, and 400×. For each tissue, ten measurements were obtained according to an established protocol27.

Immunological assays

An Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (Cusabio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) was used to measure the total immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels in the blood according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysozyme activity was evaluated according to the method described by Demers and Bayne28. The lysozyme unit present in serum (µg/mL) was obtained by comparison with a standard curve produced using lyophilized hen egg white lysozyme.

Antioxidants analysis

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) levels in serum were evaluated spectrophotometrically following the methods in previous studies29,30, respectively. Total antioxidants capacity (TAC) was analyzed in serum using colorimetric commercial kits purchased from Bio-Diagnostic Co. (Cairo, Egypt) according to Koracevic et al., 31.

Digestive enzyme activity

Serum lipase activity was determined colorimetrically at the wavelength 580 nm using kits (Ref: 281 001; Spectrum, Egyptian Company for Biotechnology, Egypt)32. The serum amylase activity was determined colorimetrically at the wavelength 660 nm using commercial kits (Cat. No. AY1050, Biodiagnostic Co. Egypt)33. Also, serum protease activity was determined colorimetrically at the wavelength 450 nm following the manufacturer’s instructions (Number: 23263, Thermo Scientific Co., USA).

Economical viability assessment

The economic analysis methodology followed established protocols4,34. The local market pricing for utilised ingredients were employed. These prices (US$) are as follows: herring fish meal, 1.25; soybean meal, 0.41; corn,0.25; rice polishings, 0.24; corn gluten, 0.97; mono calcium phosphate, 0.4; fish oil, 0.95; vitamin and mineral premix, 1.6.

At the end of the trial, the exchange rate was 1 USD = 50 Egyptian pounds (EGP). The following equations were used:

-

1.

Cost reduction per ton gain (USD) = feed cost per kg gain of the control diet (R0) – feed cost per kg gain of R10,or R20,R30 or R40 (USD).

-

2.

Cost reduction per kg gain (%) = 100 (cost reduction per kg gain [USD] in R10,or R20,R30 or R40 diets/feed cost per kg gain of the control diet [USD].

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) at a significance level of 5%. Further, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Tukey–Kramer ’s multiple range test to compare mean values between treatments at (P < 0.05) using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). All data are demonstrated as mean ± standard error (SE). Polynomial regression was employed to obtain the linear and quadratic effect of contributing graded level of fermented rice polishings on the response variables demonstrated.

Ethical approval

The study protocol received ethical approval from the Animal Health Research Institute Ethics Committee (2024) in compliance with European Union Directive 2010/63/EU. All experimental procedures adhered to institutional guidelines and ARRIVE reporting standards (https://arriveguidelines.org). Research was conducted in controlled artificial pond facilities at the Animal Health Research Institute, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt, requiring no special access permissions. No human participants or protected species were involved in this study.

Result

Nutritional value and phytic acid content of rice Polishings after solid state fermentation

Table 2 shows the proximate analysis of RP and FRP; moisture, protein, fat, ash, and fiber. Protein content of RP was raised from 12.67 ± 0.2% to 17.25 ± 0.56% by yeast SSF. The lipid content in RP and FRP decreased from 13.72 ± 0.12% to 10 ± 0.5%, whereas the fibre content decreased from 19.2 ± 0.17% to 9.5 ± 0.23%. Additionally, Phytic acid concentration in raw RP was seen to decrease dramatically from 6.24 ± 0.09 mg g-1 to 1.23 ± 0.03 mg g-1 following SSF by S. cerevisiae.

Growth performance and feed efficiency

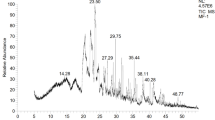

The results of the growth performance traits indicated that Nile tilapia fed R10, R20, R30, and R40 showed higher (P < 0.05) final body weight (FBW), weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion efficiency (FCE), and protein efficiency ratio (PER) than fish fed R0 (Table 3). On the other hand, the feed conversion ratio (FCR) was markedly declined (P < 0.05) by dietary R10, R20, and R30 compared to fish-fed R40 and R0 (Table 3). The survival rate ranged between 91.5 and 95.3% without marked differences among the groups (P˃0.05). The regression analysis showed that the maximum FBW (Fig. 1A) SGR (Fig. 1B), FCE (Fig. 1C) and FCR (Fig. 1D) can be reached by dietary inclusion of fermented rice polishings (FRP) at 210 to 230 g/kg diet.

Carcass composition

The body composition of Nile tilapia fed varying amounts of fermented rice polishings for 85 days is displayed in Table 4. There were no significant impacts on the moisture, crude protein, or ash contents (P˃0.05), while the crude lipid content was significantly impacted by the test diets (P < 0.05). Compared to fish fed other diets, fish fed dietary R20,R30,and R40 had a greater crude lipid content (P < 0.05).

Hematobiochemical indices

Significantly higher Hb, and RBC levels were observed in R10, R20 ,and R30 groups, with the highest values observed in the R20 group (P < 0.05) (Table 5). Furthermore, tilapia fed the R40 diet had similar Hb and PCV as fish fed the control diet (R0). Packed cell volume demonstrated significant high results in all fermented rice polishings supplied diets (R10,R20,R30,and R40) versus control one (R0)(P < 0.05). MCV, MCH, and MCHC demonstrated decreased levels with fermented rice polishings supplementation levels R10, R20, R30, in contrast, R40 and R0 demonstrated the higher levels. All diets supplemented with fermented rice polishings exhibited a considerable increase in heterophil populations (P < 0.05), with the exception of the highest level (R40), which had a lower level similar to that in the control group (R0).

The effects of the graded levels of FRP on the blood biochemical traits of Nile tilapia are shown in Table 6. No marked effects on the glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and ALT(P > 0.05). R10, R20, and R30 revealed significantly higher levels of serum total protein and lower levels of AST as compared to the control (R0) and R40 groups (P < 0.05).

Intestinal histomorphological indices

Histological examination of the intestines revealed the normal structure of the intestinal wall, mucosal fold, and intestinal villi in all segments (anterior, middle, and posterior) in the control group (R0) (Fig. 2,R0). It is noteworthy that the progressive increase in FRP concentration led to a noticeable improvement in villous height and goblet cells in the anterior, middle, and posterior segments, especially at the higher levels (R20 and R30) (Fig. 2,R20 and R30).

Anterior, middle, and posterior photomicrograph, bar = 100 m of the Nile tilapia’s intestine (bar = 100 μm, stain H&E). The anterior and middle parts of the control group (R0) had normal branching villi, propria submucosa, lamina muscularis, whereas the posterior section displayed normal mucosal folds. The anterior and middle parts of R10,R20 and R30 showing branching and increasing villi length, whereas the posterior section displayed normal mucosal folds.R40 tested group demonstrated normal intestinal villi length in the anterior and posterior segment, whereas the posterior segment demonstrated normal villi length, and normal intact mucosal folds. VH: villi height; VW: villi width; GC: goblet cell.

The villi height in the anterior segment were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in fish fed R20, R30, and R40 compared to fish fed R10 and R0, but there was no significant difference between fish fed R30 and R40 (P˃0.05) (Table 7) (Fig. 2). Conversely, the fish fed R0 had the lowest villi height (P < 0.05) when compared to the other groups. The goblet cells numbers were significantly higher in two groups, R20 and R30 only versus other tested and control groups R40,R10 and R0,respectively. There was no noticeable influence on the villi width of the anterior region (P˃0.05).

In the middle segment, Fish fed R10, R20, and R30 had significantly higher villi heights (P < 0.05) than fish given R40 and R0 (Table 7). The highest villi height was recorded for fish in group R20 followed by R30. Goblet cells number was higher in fish-fed R20, while the lowest was in fish-fed R40 (P < 0.05). In the posterior segment, the highest villi length and width demonstrated higher levels in fish-fed R20, while the lowest was in fish-fed R0 (P < 0.05) (Table 7) (Fig. 2). Goblet cells number was higher in fish-fed R20, while the lowest was in fish-fed R0 (P < 0.05).

Digestive enzyme activity

The lipase, amylase and protease activity were markedly higher (P < 0.05) in fish-fed R10, R20,and R30 than in fish-fed R40 and R0 (Table 8). Additionally, fish fed R20 showed highest lipase, amylase and protease activity than fish fed other diets (P < 0.05)(Table 8).

Immune responses

In comparison to the control group (R0), the lysozyme activity was significantly increased with all FRP-containing diets, and the highest lysozyme activity was observed in the R20 group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). IgM levels were increased significantly in fish fed FRP incorporated diets up to R30 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4) compared to R40 and control group (R0). Furthermore, tilapia fed R20 had the highest IgM activities, followed by R30 and R10 respectively (P < 0.05).

Antioxidant activities

Figures 5 and 6, and 7 demonstrate the TAC (mM/L), SOD (IU L− 1), and CAT (IU L− 1) levels in Nile tilapia given experimental diets for 85 days. Compared to the control group (R0), FRP-containing meals significantly increased TAC and CAT activity (P < 0.05).While, R20 showed the greatest activity across the FRP groups (P < 0.05). further more, Nile tilapia given experimental diets R10, R20, and R30 had significantly higher SOD activity compared to R40 and the control group (R0) (P < 0.05).

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation of dietary FRP in the diets of Nile tilapia is shown in Table 9. The cost of feed needed for 1 kg fish fed R0, R10,R20,R30 or R40 at 0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 g/kg is 0.62, 0.56, 0.53, 0.55, and 0.54 USD/kg weight gain, respectively. The relative cost of feed per kg fish gain showed 6, 7.2, 8.66, and 10.75% reduction rates in fish-fed R10,R20,R30 or R40 at 100, 200, 300, and 400 g FRP/kg compared to fish-fed R0-based diet.

Discussion

Rice polishings are regarded as one of the most important byproducts of brown rice milling, due to their high nutritious content and large annual production15. However, because to its poor processing qualities, high fiber contents, unpleasant taste, and ease of rancidity, it is not completely utilized in the animal feed15. Consequently, fermentation technologies have been effectively used to improve the digestibility and solubility of fiber-rich byproducts35. In recent years, there has been more research on the total processing and utilization of rice byproducts to increase its utilization rate in addition to the thorough utilization of nutritional fiber, protein, and oil36,37,38.

Fermentation biotechnology have been effectively employed to increase the solubility and digestibility of byproducts that are high in fibers. In this study, we investigated the incorporation of fermented rice polishings (FRP) in the diet of Nile tilapia to enhance the digestibility of rice polishings that contain high fiber content. The findings showed that FRP could be added to Nile tilapia diet without affecting the fish’s ability to develop, their gut health, or their immune and antioxidant levels. The graded levels of fermented RP provided to Nile tilapia resulted in improved growth performance outcomes, including final weight, weight increase, and SGR. It’s notable to note that employing yeast to ferment RP resulted in decreased phytic acid content (6.24 + 0.09 to 1.23 + 0.03 mg g-1), and crude fiber content (19.2 ± 0.17 to 9.5 ± 0.23%), while increased protein levels (12.67 ± 0.2 to 17.25 ± 0.56%). This result may be attributed to the ability of S. cerevisiae to hydrolyze and convert fibers into proteins. As well as, Yeast may use carbohydrates as a source of carbon required for the synthesis of proteins39,40,41. In a similar way employing yeast fermentation to wheat bran42, sunflower meal43, soybean meal44, and rapeseed meal45 resulted in higher protein levels and reduced fiber contents. The improved growth performance outcomes could also be attributed to the beneficial effects of feed fermentation, which improved the fiber breakdown of the RP and encouraged efficient feed utilization and increased body weight46,47,48. Similarly, the fermentation of wheat bran by S. cerevisiae improved the growth performance of Nile tilapia42. The positive functions of S. cerevisiae as a fermenter and probiotics, according to the authors, are linked to the enhanced growth performance of Nile tilapia fed yeast fermented wheat bran and date palm seed meal49,50,51. The findings are consistent with those of 52,53, who found that feeding Nile tilapia fermented guar and copra meal and wheat protein concentrate, as well as S. cerevisiae, increased feed efficiency.

The superior growth performance observed at 200 g/kg fermented rice polishing (RP) inclusion compared to 400 g/kg can be explained by several factors. At the optimal 200 g/kg level, RP provided a balanced supply of essential amino acids and energy that synergized effectively with other dietary components to support protein synthesis and growth54,55. In contrast, the higher 400 g/kg inclusion exceeded Nile tilapia’s capacity to tolerate antinutritional factors, particularly phytic acid, whose concentration increased proportionally with FRP levels and significantly impaired nutrient digestibility56,57. Furthermore, the elevated dietary fiber content at 400 g/kg FRP likely reduced both feed utilization efficiency and gut transit function, creating additional metabolic constraints that collectively limited growth performance58,59.

Fermentation has several benefits, one of which is the elimination of anti-nutritional factors (ANFs), which improves intestine digestion, absorption, and nutrient release60,61. These factors will illustrate the growth performance enhancement and enhanced feed utilization (FCR and PER) obtained after inclusion of the graded levels of FRP in the diet of tested Nile tilapia in this study. Since the intestines are the organs in responsible for digesting and absorbing feed, being healthy might also indicate efficient feed utilization, research has shown that fermented feeds may regulate the intestinal bacteria load, promoting intestinal health and effective digestion62. Moreover, Fish development and performance are intimately linked to the activity of digestive enzymes, and the obtained findings showed that dietary FRP enhanced the activity of the digestive enzymes (lipase, amylase, and protease). Likewise, S. cerevisiae-fed Nile tilapia fermented date palm seed meal resulted in improved digestive enzyme activity49,50. In addition to their functions in fermentation, S. cerevisiae is a well-known probiotic that may release digestive enzymes throughout fish the gastrointestinal tract, promoting efficient utilization of nutrients and digestion, which in turn promotes efficient metabolic process63,64. Since the intestines are the organs in responsible for digesting and absorbing feed, being healthy might also indicate efficient feed utilization.

According to 65, hematological indices are regarded as a useful and trustworthy indicator of fish wellbeing as well as physiological and pathological conditions. According to previous research, the blood parameters measured in this study are considered to be within the typical ranges for Nile tilapia. Additionally, feeding on the experimental diets did not substantially alter the level of WBC, heterophil, triglycerides, cholesterol, ALT, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, or basophils, suggesting that FRP added to the diet of Nile tilapia was completely safe. The ability of blood to carry and transport dissolved oxygen is mostly dependent on hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red blood cells50. Values for these metrics were substantially higher in the FRP groups, suggesting that the fish’s health had improved. This result is consistent with earlier research on aquatic species, both wild and cultivated, which showed that high hematocrit, hemoglobin, and red blood cell counts were linked to rapid movement and high activity66.

While there was largely no significant difference in ALT activity across the experimental groups, significantly decreased levels of AST were recorded when Nile tilapia were fed a diet containing FRP, particularly R20 and R30. This is an indication that feeding tilapia FRP-supplemented diets could influence the liver health of fish positively67.

Insoluble fibers, ANFs, and silica in RP may affect the histological characteristics of fish intestines68,69. The effects on the intestinal epithelial tissue also depend on the quantity of ingredients, the length of consumption, and the animal species70. The outcomes demonstrated that the control group had normal intestinal mucosa and intestinal wall structure throughout all segments (anterior, middle, and posterior). Additionally, the integration of FRP induced a significant improvement in villus height in the anterior section and enhanced branching of intestinal villi (villus height and breadth) in the middle and posterior segments, especially at the higher levels (RP20 and RP30). These results were in harmony with42,49,53, who observed that S. cerevisiae fermented wheat bran, date palm seed meal, and wheat protein concentrate improved the intestinal histological measures in Nile tilapia, fermented rapeseed meal in red sea bream48. When fish were fed graded amounts of FRP, the villi length in the middle segment increased, which was linked to an increase in goblet cell counts. These benefits support the concept that enhanced digestion and absorption capacity are directly connected to improved villi surface71. The improved intestinal morphology—characterized by increased villi height, greater goblet cell numbers, and enhanced digestive enzyme activity—observed with moderate fermented rice polishing (FRP) inclusion (200–300 g/kg) likely results from two key mechanisms. First, fermentation generates bioactive compounds (short-chain fatty acids, peptides, and prebiotics) that directly stimulate epithelial cell proliferation (promoting villi elongation), upregulate mucus production (increasing goblet cell counts), and enhance enzyme secretion through cellular signaling72,73. Second, the fermentation process reduces anti-nutritional factors like phytic acid, thereby improving mineral bioavailability for gut barrier maintenance while simultaneously decreasing inflammatory responses that could compromise mucosal integrity74. In contrast, the diminished effects at 400 g/kg FRP may be due to the fiber overload that could accelerate intestinal transit (reducing nutrient absorption time) and alter microbial production; and the physiological capacity to process FRP-derived nutrients may be exceeded beyond optimal inclusion levels, reflecting a threshold effect common in nutritional studies58.

Fermentation with beneficial bacteria generates short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are easily transported across the epithelium and enhance the permeability of absorbed nutrients75. Furthermore, fermentation reduces the adverse consequences of ANFs on epithelial function. This ultimately results in efficient feed utilization, which contributes to superior growth performance and fish health76. As a result, efficient feed utilization (FCR and PER) was reported in this study, which can explain improved growth performance with dietary FRP. Feed utilization and digestion have a strong influence on the chemical makeup of fish carcasses77. Since certain digested nutrients can accumulate throughout the fish’s entire body, this demonstrates effective feed utilization. Consequently, the investigation found no obvious impacts of FRP on the protein, ash, and moisture contents of Nile tilapia carcasses. However, FRP, particularly the FRP 20, R30, and R40 diets, had a noticeable impact on the lipid content. Because of their functions in stimulating development and aiding in digestion, dietary S. cerevisiae may have an impact on the composition of fish carcasses50. This can also be related to the high lipid content in the tested rice polishings, which may affect the composition of the fish carcass78.

One of the most reliable blood parameter tools for assessing the immunological and physiological status of fish is total serum protein, which may be influenced by the quality of animal feed79,80. Similar to this, natural antibodies (IgM) have a variety of defence functions, including preventing the spread of infectious agents, eliminating pathogens, healing damaged tissue, and re-establishing a healthy status81. In the current study, the immunological condition (total serum protein and total IgM) of Nile tilapia was considerably improved by the graded levels of FRP, particularly a diet enriched with the R20. All FRP groups showed a significant rise in IgM levels, according to our data, with R20-supplemented fish showing the greatest values. These findings are in line with earlier research that shown the contribution of saccharomyces and fermentation in raising blood IgM levels50.

Further, lysozyme is an important innate immune system defensive mechanism that mediates protection against microbial invasion82,83. Lysozyme activity was enhanced when fermented rice polishings were incorporated in the Nile tilapia diet, especially at the level of R20 & R30. The explanation for this could be related to the probiotic ability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase lysozyme secretion in Nile tilapia, and or the benefit of fermentation that counteracting the effect of antinutritional factors and high fiber contents of FRP4,42,49.

Malnutrition, the presence of ANFs, and insoluble fibers in RP may all cause the production of free radicals, which is mediated by antioxidant biomarkers such as TAC, CAT, and SOD84. CAT is an important antioxidant enzyme found in nearly all biological tissues that demand oxygen, and subsequently catalyzes the breakdown or reduction of hydrogen peroxide into water and molecular oxygen, therefore completing the detoxification process initiated by SOD85. In particular, CAT protects cells from oxidative damage by using radical scavenging enzymes to convert hydrogen peroxide into water86. SOD is an essential antioxidant enzyme that disperses two molecules of superoxide anion to produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and molecular oxygen (O2)87. The fermentation process may enhance the release of polyphenols through the glycolysis process of plant-derived components. In this study, serum TAC, CAT, and SOD activity were considerably increased in Nile tilapia given FRP compared to the control, reaching the highest activity level in R20 group. The significant antioxidative functions of these polyphenols are well established in general health enhancement. Additionally, S. cerevisiae has a high concentration of MOS and β-glucan, which may improve the immunological and antioxidant response88,89. Similar findings were reported by90, who found that S. cerevisiae fed to Nile tilapia exhibited an activated antioxidant response.

The economic evaluation of dietary FRP revealed that Nile tilapia production costs were lower than the control group (R0). These findings suggest that implementing FRP might improve the sustainability of the Nile tilapia aquaculture business. Additional future studies are required to focus on adding suitable feed additives such as attractants, exogenous digestive enzymes, prebiotics, probiotics, and natural immunological and growth boosters to increase the FRP utilization in Nile tilapia diets. Ultimately, the results of this study demonstrate that dietary supplementation with fermented rice polishings can effectively enhance the growth performance, feed utilization, haematological indices, immunological parameters, antioxidant status, and digestive function of Nile tilapia. The high nutritious content present in rice polishings, derived through the fermentation process, appear to be responsible for the overall beneficial outcomes discovered throughout numerous physiological indices. The optimal dietary incorporation level was determined to be 210–230 g/kg diet, which provided the most significant improvements. These findings reveal the potential of the rice polishings as a valuable functional plant by-product to improve the productivity and health of Nile tilapia in aquaculture systems.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that fermented rice polishings (FRP) can be effectively incorporated into Nile tilapia diets at up to 30% without adverse effects on growth, nutrient utilization, immune response, or oxidative status, while 20% FRP emerges as the optimal inclusion level for maintaining fish health and economic viability. The findings highlight FRP’s dual value as both a sustainable feed ingredient that valorizes agro-industrial waste and a functional supplement that enhances gut health and antioxidant capacity, with 20% inclusion offering the best balance between performance and safety. Notably, the negative effects observed at 40% inclusion underscore the importance of dosage control to prevent intestinal damage and growth reduction. These results provide practical guidance for tilapia farmers seeking to reduce feed costs while maintaining fish health, contributing to more sustainable aquaculture practices through the effective utilization of rice milling byproducts.

Data availability

All data supporting the results of this research are accessible upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Uddin, M. N. et al. Understanding the constraints and its related factors in tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) fish culture at farm level: A case from Bangladesh. Aquaculture 530, 735927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735927 (2021).

Esmaeili, H. R. & Eslami Barzoki, Z. Climate change May impact nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) distribution in the southeastern Arabian Peninsula through range contraction under various climate scenarios. Fishes 8, 481 (2023).

Dhar, V. et al. Fishmeal substitutions and their implications for aquatic animal immune and gut function: A review. Comp. Immunol. Rep. 7, 200171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirep.2024.200171 (2024).

Badran, A. A. et al. Using a blend of oilseed meals in the diets of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): effects on the growth performance, feed utilization, intestinal health, growth, and metabolic-related genes. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 529. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-04373-5 (2024).

Gatlin, I. I. I. Expanding the utilization of sustainable plant products in aquafeeds: a review. Aquac. Res. 38, 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01704.x (2007).

Hua, K. et al. The future of aquatic protein: implications for protein sources in aquaculture diets. One Earth. 1, 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.10.018 (2019).

Ronie, M. E. et al. Unveiling the potential applications of plant by-products in food – A review. Waste Manage. Bull. 2, 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wmb.2024.07.008 (2024).

Aït-Kaddour, A. et al. Transforming plant-based waste and by-products into valuable products using various food industry 4.0 enabling technologies: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 955, 176872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176872 (2024).

Champagne, E. T. & Center, U. S. A. R. S. S. R. R. Rice: Chemistry and Technology (American Association of Cereal Chemists, 2004).

Yılmaz Tuncel, N. Stabilization of rice bran: A review. Foods 12, 1924 (2023).

Kim, M. S. et al. Marker-Assisted backcrossing (MABc) to improve eating quality with thin seed coat and aleurone layer of Non-Glutinous Japonica variety in rice. Genes 13, 210 (2022).

Sapwarobol, S., Saphyakhajorn, W. & Astina, J. Biological functions and activities of rice Bran as a functional ingredient: A review. Nutr. Metab. Insights. 14, 11786388211058559. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786388211058559 (2021).

Peanparkdee, M., Patrawart, J. & Iwamoto, S. Physicochemical stability and in vitro bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins from Thai rice Bran extracts. Food Chem. 329, 127157 (2020).

Amagliani, L., O’Regan, J., Kelly, A. L. & O’Mahony, J. A. Composition and protein profile analysis of rice protein ingredients. J. Food Compos. Anal. 59, 18–26 (2017).

Huang, S., Benchamas, G. & Huang, G. Whole processing and use of rice Polishings. Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 63, 102373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102373 (2020).

Irakli, M., Kleisiaris, F., Mygdalia, A. & Katsantonis, D. Stabilization of rice Bran and its effect on bioactive compounds content, antioxidant activity and storage stability during infrared radiation heating. J. Cereal Sci. 80, 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2018.02.005 (2018).

Plaipetch, P. & Yakupitiyage, A. Effect of replacing soybean meal with yeast-fermented Canola meal on growth and nutrient retention of nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758). Aquac. Res. 45, 1744–1753. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.12119 (2014).

Vaintraub, I. A. & Lapteva, N. A. Colorimetric determination of phytate in unpurified extracts of seeds and the products of their processing. Anal. Biochem. 175, 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(88)90382-x (1988).

AOAC & International Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. AOAC International 20th ed. Gaithersburg, MD, USA., 3172. (2016).

Council, N. R. Nutrient Requirements of Fish and Shrimp (National Academies, 2011).

Zaineldin, A. I. et al. The influences of Bacillus subtilis C-3102 inclusion in the red sea Bream diet containing high levels of soybean meal on growth performance, gut morphology, blood health, immune response, digestibility, digestive enzymes, and stress resistance. Aquacult. Nutr. 27, 2612–2628. https://doi.org/10.1111/anu.13389 (2021).

Rawling, M. D., Merrifield, D. L. & Davies, S. J. Preliminary assessment of dietary supplementation of Sangrovit® on red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) growth performance and health. Aquaculture 294, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.05.005 (2009).

Hawkey, C. M., Bennett, P. M., Gascoyne, S. C., Hart, M. G. & Kirkwood, J. K. Erythrocyte size, number and haemoglobin content in vertebrates. Br. J. Haematol. 77, 392–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb08590.x (1991).

Tatsumi, N., Tsuji, R., Yamada, T., Kubo, K. & Matsuda, T. Spot chem. EZ SP-4430 no Kiso Teki Kento. J. Clin. Lab. Instruments Reagents. 23, 427–433 (2000).

Reitman, S. & Frankel, S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 28, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56 (1957).

Taylor, P. W. & Roberts, S. D. Clove oil: an alternative anaesthetic for aquaculture. North. Am. J. Aquaculture. 61, 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8454(1999)061%3C0150:COAAAF%3E2.0.CO;2 (1999).

De Los Santos, F. S. et al. Gastrointestinal maturation is accelerated in Turkey Poults supplemented with a mannan-oligosaccharide yeast extract (Alphamune). Poult. Sci. 86, 921–930 (2007).

Demers, N. E. & Bayne, C. J. The immediate effects of stress on hormones and plasma lysozyme in rainbow trout. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 21, 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-305x(97)00009-8 (1997).

McCord, J. M. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055 (1969).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3 (1984).

Koracevic, D., Koracevic, G., Djordjevic, V., Andrejevic, S. & Cosic, V. Method for the measurement of antioxidant activity in human fluids. J. Clin. Pathol. 54, 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.54.5.356 (2001).

Moss, D. & Henderson, A. Digestive enzymes of pancreatic origin. Tietz Textbook Clin. Chem. 3, 689–708 (1999).

Caraway, W. T. A stable starch substrate for the determination of amylase in serum and other body fluids. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 32, 97–99 (1959).

Abdel-Tawwab, M. et al. Effects of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae meal on growth performance, organs-somatic indices, body composition, and hemato-biochemical variables of European sea bass, dicentrarchus labrax. Aquaculture 522, 735136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735136 (2020).

Fan, L., Ma, S., Li, L. & Huang, J. Fermentation biotechnology applied to wheat Bran for the degradation of cell wall fiber and its potential health benefits: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 275, 133529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133529 (2024).

Mohammadi, F. et al. Effect of washing, soaking and pH in combination with ultrasound on enzymatic rancidity, phytic acid, heavy metals and coliforms of rice Bran. Food Chem. 334, 127583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127583 (2021).

Wu, N. N. et al. Nutritional and cooking quality improvement of brown rice noodles prepared with extruded rice Bran. Cereal Chem. 98, 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/cche.10374 (2021).

Chen, F., Huang, S. & Huang, G. Preparation, activity, and antioxidant mechanism of rice Bran polysaccharide. Food Funct. 12, 834–839. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO02498H (2021).

Nevoigt, E. Progress in metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 379–412. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00025-07 (2008).

Chuang, W. Y., Lin, L. J., Hsieh, Y. C., Chang, S. C. & Lee, T. T. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and phytase co-fermentation of wheat Bran on growth, antioxidation, immunity and intestinal morphology in broilers. Anim. Biosci. 34, 1157–1168. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.20.0399 (2021).

Wang, Z., Ma, S., Li, L. & Huang, J. Effect of wheat Bran dietary fiber on structural properties and hydrolysis behavior of gluten after synergistic fermentation of Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Nutr. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.982878 (2022).

Mohammady, E. Y., Aboseif, A. M., Soaudy, M. R., Ramadan, E. A. & Hassaan, M. S. Appraisal of fermented wheat Bran by Saccharomyces cerevisiae on growth, feed utilization, blood indices, intestinal and liver histology of nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 575, 739755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739755 (2023).

Awad, A. et al. Growth and physiological response of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed a fermented mixture of plant protein sources. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 315, 116034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2024.116034 (2024).

Hassaan, M. S., Soltan, M. A. & Abdel-Moez, A. M. Nutritive value of soybean meal after solid state fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae for nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 201, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.01.007 (2015).

Vlassa, M. et al. The yeast fermentation effect on content of Bioactive, nutritional and Anti-Nutritional factors in rapeseed meal. Foods 11, 2972 (2022).

Fu, Z. et al. Effects of fermented feed on growth performance, serum biochemical indexes, antioxidant capacity, and intestinal health of lion-head goslings. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1284523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1284523 (2023).

Predescu, N. C., Stefan, G., Rosu, M. P. & Papuc, C. Fermented feed in broiler diets reduces the antinutritional Factors, improves productive performances and modulates gut Microbiome—A review. Agriculture 14, 1752 (2024).

Dossou, S. et al. Effect of partial replacement of fish meal by fermented rapeseed meal on growth, immune response and oxidative condition of red sea Bream juvenile, pagrus major. Aquaculture 490, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.02.010 (2018).

Dawood, M. A. O. et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae increases the acceptability of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) to date palm seed meal. Aquaculture Rep. 17, 100314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100314 (2020).

Abd El-Naby, A. S. et al. Effects of dietary fermented Saccharomyces cerevisiae extract (Hilyses) supplementation on growth, hematology, immunity, antioxidants, and intestinal health in nile tilapia. Sci. Rep. 14, 12583. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62589-9 (2024).

Islam, S. M. M., Rohani, M. F. & Shahjahan, M. Probiotic yeast enhances growth performance of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) through morphological modifications of intestine. Aquaculture Rep. 21, 100800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2021.100800 (2021).

Dileep, N. et al. Nutritive value of Guar and Copra meal after fermentation with yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the diet of nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 53, 416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-021-02855-4 (2021).

Omar, S. S., Anwar, A. Y., Hassaan, M. S., El-Haroun, E. & Davies, S. J. Preliminary assessment of a novel fermented wheat protein concentrate from a bio-distillation source as a dietary ingredient contribution for tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture Rep. 24, 101101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101101 (2022).

Dossou, S. et al. Effects of replacing fishmeal with fermented and non-fermented rapeseed meal on the growth, immune and antioxidant responses of red sea Bream (Pagrus major). Aquacult. Nutr. 25, 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/anu.12876 (2019).

El-Desouky, F. F. et al. Improving Yellow Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Utilization with Sodium Butyrate in Nile Tilapia Diets: Effects on Growth Performance, Intestinal Histology, Antioxidative Response, and Blood Biomarkers. Aquaculture Nutrition 2442308, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/2442308 (2024).

El-Ghafloul, M. S. et al. The growth performance, feed efficiency, intestinal histo-morphological indices, antioxidat Ive status, and related genes of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed fermented rice hulls. Aquaculture 606, 742586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742586 (2025).

Dossou, S. et al. Dynamical hybrid system for optimizing and controlling efficacy of Plant-Based protein in Aquafeeds. Complexity 2021 (9957723). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9957723 (2021).

Nafees, M. S. M., Kamarudin, M. S., Karim, M., Hassan, M. Z. & de Cruz, C. R. Effects of dietary fiber on growth, feed efficiency and nutrient utilization of tinfoil barb (Barbonymus schwanenfeldii, bleeker 1853) fry. Aquaculture Rep. 32, 101743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2023.101743 (2023).

Sherif, E. M. et al. Growth performance, antioxidative status, and immune response of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed dietary fermented spirulina platensis. Aquaculture Rep. 39, 102324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102324 (2024).

Anyiam, P. N. et al. Effect of fermentation time on nutritional, antinutritional factors and in-vitro protein digestibility of macrotermes nigeriensis-cassava Mahewu. Measurement: Food. 11, 100096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meafoo.2023.100096 (2023).

Samtiya, M., Aluko, R. E. & Dhewa, T. Plant food anti-nutritional factors and their reduction strategies: an overview. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-020-0020-5 (2020).

Zhang, P. Influence of foods and nutrition on the gut Microbiome and implications for intestinal health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23179588 (2022).

El-Bab, A. F. F. et al. The effect of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae on growth Performance, oxidative Status, and immune response of sea Bream (Sparus aurata). Life (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/life12071013 (2022).

Shehata, A. I. et al. Evaluation of different probiotics on growth, body composition, antioxidant capacity, and histoarchitecture of Mugil Capito. Sci. Rep. 14, 7379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57489-x (2024).

Fazio, F. Fish hematology analysis as an important tool of aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 500, 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.10.030 (2019).

Mairbäurl, H. Red blood cells in sports: effects of exercise and training on oxygen supply by red blood cells. Front. Physiol. 4, 332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00332 (2013).

Samanta, P., Pal, S., Mukherjee, A. K. & Ghosh, A. R. Evaluation of metabolic enzymes in response to Excel Mera 71, a glyphosate-based herbicide, and recovery pattern in freshwater teleostean fishes. Biomed Res Int 425159, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/425159 (2014).

Mahalak, K. K. et al. Supplementation with soluble or insoluble rice-bran fibers increases short-chain fatty acid producing bacteria in the gut microbiota in vitro. Front. Nutr. 11, 1304045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1304045 (2024).

Bromley, P. J. & Adkins, T. C. The influence of cellulose filler on feeding, growth and utilization of protein and energy in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdnerii Richardson. J. Fish Biol. 24, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1984.tb04794.x (1984).

Kong, S., Zhang, Y. H. & Zhang, W. Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cells Properties and Functions by Amino Acids. Biomed Res Int 2819154, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2819154 (2018).

Kiela, P. R. & Ghishan, F. K. Physiology of intestinal absorption and secretion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 30, 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2016.02.007 (2016).

Li, B. et al. Application status and development prospect of fermented ingredients in aquaculture. Aquaculture Rep. 42, 102842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2025.102842 (2025).

Anany, E. M. et al. Combined effects of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the growth Performance, feed utilization intestinal Health, and blood biomarkers of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed fish Meal-Free diets. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 17, 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-023-10199-8 (2025).

Sawant, S. S., Park, H. Y., Sim, E. Y., Kim, H. S. & Choi, H. S. Microbial fermentation in food: impact on functional properties and nutritional Enhancement—A review of recent developments. Fermentation 11, 15 (2025).

Morrison, D. J. & Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 7, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082 (2016).

Shimul, T. J. T. et al. Fermented aquatic weed meal (FAWM) as a protein source in Asian catfish Clarias Batrachus diets: impacts on growth, blood chemistry profile, liver and gut morphology and economic efficiency. Aquaculture Rep. 38, 102305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102305 (2024).

Omnes, M. H. et al. Effects of dietary tannin on growth, feed utilization and digestibility, and carcass composition in juvenile European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax L). Aquaculture Rep. 6, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2017.01.004 (2017).

Zhou, J., Feng, P., Li, Y., Ji, H. & Gisbert, E. Effects of dietary lipid levels on lipid accumulation and health status of adult Onychostoma macrolepis. Aquaculture Fisheries. 9, 795–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaf.2023.07.008 (2024).

Esmaeili, M. & Blood Performance A new formula for fish growth and health. Biology (Basel). 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10121236 (2021).

Zheng, K., Wu, L., He, Z., Yang, B. & Yang, Y. Measurement of the total protein in serum by biuret method with uncertainty evaluation. Measurement 112, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2017.08.013 (2017).

Jones, K., Savulescu, A. F., Brombacher, F. & Hadebe, S. Immunoglobulin M in health and diseases: how Far have we come and what next? Front. Immunol. 11, 595535. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.595535 (2020).

Ferraboschi, P., Ciceri, S. & Grisenti, P. Applications of Lysozyme, an innate immune defense Factor, as an alternative antibiotic. Antibiot. (Basel). 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121534 (2021).

Ragland, S. A. & Criss, A. K. From bacterial killing to immune modulation: recent insights into the functions of lysozyme. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006512. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006512 (2017).

Su, W. et al. Co-fermented defatted rice Bran alters gut microbiota and improves growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immune status and intestinal permeability of finishing pigs. Anim. Nutr. 11, 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2022.07.008 (2022).

Ighodaro, O. M. & Akinloye, O. A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 54, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001 (2018).

Nandi, A., Yan, L. J., Jana, C. K. & Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 9613090, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9613090 (2019).

Younus, H. Therapeutic potentials of superoxide dismutase. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 12, 88–93 (2018).

Zaineldin, A. I. et al. Mitigating aflatoxin B1-Induced growth impairment and hepatic stress in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): comparative efficacy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Silicate-Based detoxifiers. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-023-10210-2 (2024).

Piotrowska, M. & Masek, A. Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall components as tools for Ochratoxin A decontamination. Toxins 7, 1151–1162 (2015).

Abdel-Latif, H. M. R. et al. Dietary effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and allium sativum on growth, antioxidant status, hepatic and intestinal histoarchitecture, expression of growth- and immune-related genes, and resistance of Oreochromis niloticus to Aeromonas sobria. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 148, 109493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2024.109493 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributionAmr I. Zaineldin: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.Mohammed Barakat: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, review & editing.Mohammed S. El Gohary: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources.Mohammed Rashed: Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Data curation, Visualization.Ehab Elsebaey: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaineldin, A.I., Barakat, M., El Gohary, M.S. et al. Fermented rice polishings dietary supplementation sustainably enhanced growth performance, gut morphology, immune response and antioxidant status of Nile tilapia. Sci Rep 15, 41162 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26417-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26417-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The dietary application of fermented abalone viscera meal in Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) in South Africa

Aquaculture International (2026)