Abstract

How does AI capabilities fundamentally reshape SMEs in digital-green transition? Given the fact that the concept “green” value co-creation is crucial for SMEs in China. This study aims to undertake a timely inquiry for SMEs’ green value co-creation in China, as it still remains unclear for SMEs’ green value co-creation in green AI context. To fill these gaps, we conduct a moderated-mediation analysis of 632 SMEs from southeast China, based on RBV, stakeholder theory, and organizational learning theory. The main results indicate that (1) Green value co-creation has a mediating effect between artificial intelligence capabilities and triple bottom line performance. (2) The relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and green value co-creation is moderated by green ambidextrous learning. (3) Green ambidextrous learning can amplify the indirect effects of AI capabilities on triple bottom line performance via green value co-creation. These results advance the theoretical frontiers of green value co-creation in developing countries. We also offer practical suggestions for green AI-enabled digital-green dual transformation of SMEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the contemporary era, green AI has emerged as a pivotal paradigm shaping global socioeconomic progress. Green AI is reshaping our daily life by striking a balance between convenience and sustainability. For example, green shopping app analyzes shopping options and recommends locally green products1. Green AI traffic management systems can optimize traffic wait times2; AI-driven garbage sorting systems increase material recycling rates and reduce unnecessary waste discharge3; AI Smart Home System manages the operation of home appliances, making life more comfortable4. With the development of AI technology, people have gradually become accustomed to and advocated a green and low-carbon lifestyle, such as low-carbon clothing, low-carbon consumption, low-carbon office, shared bicycles, energy conservation and emission reduction, etc. These improvements are integrated into daily life, making green AI an indispensable part for modern living.

In the ever-changing business environment, green AI has also emerged more than a high-tech tool, it is supposed to be a digital force driving fundamental change in business model innovation, decision-making, and green competitive edge. However, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in China still face significant challenges in achieving green AI. By the end of 2024, the number of private enterprises in China had exceeded 55 million, contributing over 50% of national tax revenue and more than 60% of GDP. These enterprises have emerged as the core engine propelling sustainable economic and social development. SMEs mainly have the following characteristics: maximization of economic benefits coupled with lacking green awareness; a shortage of artificial intelligence talent, limited financial resources, and significant challenges in undertaking technological transformation5; small operational scale, poor competitiveness and numerous unresolved issues6. Consequently, how to leverage the AI capabilities of SMEs to drive its triple bottom line performance (economic, environmental, and social) has emerged as an urgent issue in the context of green AI.

To shed light on these questions, we emphasize the potential role of green value co-creation in SMEs. As an emerging concept, green value co-creation has gradually attracted scholars’ attention in the past five years. Chang7 propose the concept of green value co-creation, defining it as the process whereby corporate partners actively share green philosophies, collaboratively engage in sustainable production and consumption practices, thereby co-generating economic and environmental value. Manufacturing enterprises can strengthen their green organizational capabilities, specifically green technology development and green operational capabilities by green value co-creation8. Although few studies have explored the role of green value co-creation in SMEs9,10, no research has leveraged AI capabilities to facilitate green value co-creation in SMEs, thereby enhancing their economic, environmental, and social performance.

Based on organizational learning theory, the concept of green ambidextrous learning, encompassing both green exploration learning and green exploitation learning has garnered globally scholarly attention in recent years11. Green exploration learning refers to the process of enterprises pursuing new environmental protection knowledge, while green exploitation learning emphasizes the improvement of existing environmental protection knowledge by enterprises. Current academic research on green ambidexterity learning primarily focuses green ambidextrous innovation12, green performance11, and green competitive advantage13. However, no existing literature has investigated the role of green organizational ambidextrous learning in the relationship among AI capabilities, green value co-creation, and corporate performance. In the era of digital economy, it is particularly important to deeply explore the moderated mediating role of green organizational ambidextrous learning, to better realize the co-creation of green value in SMEs, foster learning organizations in SMEs, and promote greater technological cooperation.

Consequently, new questions have arisen:

How does artificial intelligence capabilities influence SMEs’ triple bottom line performance?

What is the role of green value co-creation in promoting the coordinated development of digitalization and sustainability in China?

In what ways do green ambidextrous learning influence SMEs today?

This article constructs the internal driving mechanism of artificial intelligence capabilities, green value co-creation and triple bottom line performance, explaining the coordinated development process of digitalization and sustainability in SMEs green innovation. To sum up, we provide following possible contributions:

First, this paper constructs a green value co-creation mechanism for SMEs, serving as a new theoretical advancement on existing value co-creation literature. Although the research on the concept of “value co-creation” is relatively mature14,15,16, the research on “green” value co-creation is obviously insufficient. As an emerging concept in recent years, green value co-creation still offers substantial research opportunities especially in developing countries. This article further explores the extension of green value co-creation, which makes up for the current shortcomings of “green value co-creation” as an emerging concept with relatively limited literature and homogeneous research content in developing countries.

Second, we provide a new perspective on research of green AI. Most of green AI research only focuses on the application of green AI technology in enterprises, but have not yet formed mature theoretical and practical guidance on how to coordinate multiple stakeholders, and fully embed green AI into all aspects of enterprise operations. To be specific, Although artificial intelligence has attracted significant scholarly attention in recent years17,18,19, the underlying mechanisms through which AI capabilities enhance triple bottom line performance remain underexplored. On the one hand, most of the existing literature focuses on the impact of artificial intelligence on economic performance20,21. The SMEs’ social performance, social responsibility or green performance driven by artificial intelligence needs to be further explored.

Third, it remains unclear when traditional concept “green ambidextrous learning” combines with new concept “green AI”. While some studies have also mentioned green AI and sustainable learning22, AI capabilities and green intellectual capital23, or AI and ambidextrous green innovation, there is a paucity of research focus on green exploration learning and green exploitation learning in the field of green AI. This study significantly advances organizational ambidexterity theory by integrating green ambidextrous learning as pivotal boundary conditions into green value co-creation frameworks, providing new methods and ideas to achieve green AI for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Finally, this research represents a potential fit among AIC, GER, GEI, GVC, ECP, ENP, SOP. While the developing of AI capabilities is the mainstream internationally today, no studies have demonstrated how AIC enhances ECP/ ENP/SOP via GVC. We establish a comprehensive theoretical framework for how AIC improves GVC, which finally improves to higher ECP, ENP, SOP.

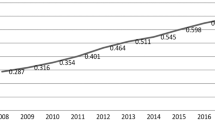

The overall workflow of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Theoretical foundation and research hypotheses

Artificial intelligence capabilities and triple bottom line performance

Artificial intelligence has been first defined by Macarthy in the 1950s as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines”24. Artificial intelligence refers to the use of computers to simulate human intelligent behavior, including learning, judgment, and decision-making25. Artificial intelligence refers to the ability of machines to perform tasks related to intelligent creatures. It has multiple branches, such as computer vision, speech, machine learning, big data and natural language processing26,27. Artificial intelligence capabilities also includes the ability to understand external data learning, simulate human vision and language cognition, and process complex human emotions28,29,30.

Green AI refers to companies and individuals using green practices, learning and utilizing AI technology to mitigate the adverse impact of humans on the natural environment, while also mitigating the impact of AI itself on the environment31. AI-based predictive models can identify inefficiencies and dynamically optimize production processes, resulting in energy savings and emission reductions32. Integrating AI algorithms with Internet of Things (IoT) systems enables real-time monitoring and forecasting of energy usage, thereby reducing the energy consumption of the lighting systems33. AI energy optimization can reintegrate renewable energy and support green decision-making34. Unlike large enterprises which could afford expensive infrastructure and R&D costs, SMEs benefit more from scalable, low-cost AI solutions such as cloud-based AI services, which allow them to access cutting-edge algorithms and data analytics tools without bearing the expensive R&D costs typically associated with AI deployment. Through cloud-delivered green AI, SMEs can enhance resource efficiency, reduce operational waste, and remain competitive in digital and sustainability transitions. For example, by leveraging AI technologies like machine learning, NLP, image recognition, chatbots, and intelligent algorithms, B2B SMEs can integrate with AI platforms to improve cross-platform operational efficiency and create value35. Wang et al.36 investigates how SMEs in central China adapt to the growing influence of AI, such as automation, data analytics, and intelligent manufacturing into their operations to enhance efficiency and competitiveness. Studies in Saudi Arabia37 and Turkey38 show that AI adoption can strengthen sustainable business performance and facilitate green innovation strategies for SMEs. In the daily business operations, green AI can improve companies’ social responsibility, legal compliance, and competitiveness39. At the same time, AI can create opportunity for Green HRM40, rethink green talent management41, and improve companies’ market advantages42. Scholars in different fields use green AI to obtain data, reduce energy consumption, collaborate across fields, and enhance sustainable understanding43. Consequently, green AI is playing a crucial role in multiple fields, and continuously innovate and optimize existing resource allocation and industrial structure.

Today, the impact of green management on corporate performance has evolved from a single focus on economic performance to a comprehensive exploration of multi-dimensional organizational performance. The triple bottom line performance discussed in this article refers to a company’s economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance44,45. Economic performance refers to the operating benefits and performance during a certain operating period46; Environmental performance is reflected in the comprehensive performance of its environmental risk control capabilities and sustainable value creation capabilities47; Social performance refers to the comprehensive benefits which bring to society, the environment, and residents48. Many studies consider these three sub-dimensions as relatively independent performance targets. For example, some studies explore artificial intelligence and how supply chain transparency, economic, environmental, and social performance are connected49, Some studies have used these three independent dimensions to examine different impact on the quality of sustainable development reports in the Russian oil and gas industry50. Economic, social and environmental dimensions, as distinct performance goals, are three independent variables widely used in the measurement of sustainable development51,52.

According to the resource-based view53, enterprises have tangible or intangible resources which can be transformed into immobile and difficult-to-replicate resources, gaining sustainable competitiveness. This article posits that artificial intelligence capabilities, defined as the capacity to leverage AI systems for data identification, analysis, inference, and learning from data to pursue specific organizational and societal goals, constitute inimitable resources capable of fostering unique competitive advantages. Advanced artificial intelligence technologies can significantly enhance corporate performance. For example, Wamba-Taguimdje et al.54 found AI can enhance organizational performance across financial, marketing, and administrative domains by optimizing operational processes, enhancing automation and information processing efficiency, Sullivan & Fosso Wamba55 demonstrated that three AI capabilities (AI automation, AI analytics, and AI relational capabilities) have a positive impact on corporate performance, process innovation, and product innovation56,57. At the same time, AI capabilities also affects the overall performance of organizations through their dynamic capabilities and creativity58,59.

In summary, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Artificial intelligence capabilities is positively associated to economic performance(1a), environmental performance (1b), and social performance(1c).

The mediating effects of green value Co-Creation

Drawing on stakeholder theory, managers are obligated to balance the interests of diverse stakeholders in the practice of corporate management60. It is evident that the value co-creation holds particular importance61. Green value co-creation refers to a dynamic integration mechanism that systematically aligns and synergizes multi-stakeholder resources (encompassing corporate entities, customers, and other relevant parties) to generate sustainable value and realize mutually beneficial outcomes10. A notable example is Ant Forest, whose gamification platform has attracted more than 500 million users to accumulate “green energy” through low-carbon activities such as walking or taking public transportation, and then transformed it into an ecological construction project with the participation of the entire population through the co-creation of green value62. In the digital economy era, digital green value co-creation can replace the traditional value co-creation, improve green network embedding, and thus have a good promoting effect on green innovation performance63.

Existing literature has explored the relationships among value co-creation, AI capabilities, and corporate performance. On the one hand, some scholars have found a close connection between AI capabilities and value co-creation64, artificial intelligence and digital transformation are reshaping the value co-creation of enterprises in the B2B market65, incorporating artificial intelligence technology into mobile banking service platforms can enhance the value co-creation process and improve customers’ consumption comfort66. On the other hand, some scholars have found that value co-creation (shared values, information sharing, mutual benefit) can improve the strategic position of SMEs and thus enhance corporate performance67. With the rise in public environmental awareness, green value co-creation exerts a direct positive impact on corporate performance68. Green value co-creation can also improve firm performance under the influence of institutional pressure68.

In line with RBV, a company’s AI capabilities are scarce and heterogeneous internal resources. Based on stakeholder perspective, companies need to collaborate with key stakeholders, including customers, suppliers, governments, and communities, transforming these unique resources into economic performance, environmental performance, and social performance via green value co-creation. Specifically, for suppliers, the company leverages an AI-driven supply chain carbon management platform to generate customized green solutions and invite suppliers to participate in energy conservation and emission reduction initiatives. For customers, the company uses AI to analyze green needs and co-design green products with them. It also provides consumers with AI-verified product carbon footprint labels. For governments, it automatically generates compliance-compliant environmental reports. It also leverages AI to match green subsidies and encourage governments to develop green support measures. For communities, the company uses AI to integrate community environmental data and support the design of green public welfare projects. These initiatives continuously transform internal AI resources into win-win green alliances for all parties, achieving shared green value creation.

In summary, we propose:

Hypothesis 2

Green value co-creation has a mediating effect between artificial intelligence capabilities and economic performance (2a), environmental performance (2b), and social performance (2c).

The moderated mediation effects of green ambidextrous learning

Drawing on organizational learning theory, organizational learning serves as the cornerstone for enterprises to accumulate technological capabilities and cultivate competitive advantages69. As we mentioned above, green exploration learning refers to the process of enterprises pursuing new environmental protection knowledge, while green exploitation learning emphasizes the improvement of existing environmental protection knowledge by enterprises. For example, manufacturing companies can acquire new environmental knowledge and technologies from external green technology R&D institutions to broaden their green knowledge base and achieve green exploratory learning. At the same time, they can extract new knowledge from existing green processes and optimize accumulated experience to deepen their green knowledge and achieve green exploitative learning. The updating of these two types of knowledge together lays a solid foundation for the co-creation of green value within the enterprise70. Although there is no research found the relationship between green ambidextrous learning, artificial intelligence capabilities, green value co-creation, and corporate performance, we found some indirect evidences: For instance, scholars have discussed the role of organizational learning strategies in the development of artificial intelligence71, and the relationship between organizational learning and value co-creation72, or the impact of organizational learning on organizational performance improvement73. Given the positive impact of organizational learning on artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities, green value co-creation, and organizational performance, this study aims to investigate the role of green organizational ambidextrous learning in relationships among AI capabilities, green value co-creation, and economic/environmental/social performance. We argue that the positive relationship between AI capabilities and economic/environmental/social performance via green value co-creation could be strengthened by both explorative and exploitative learning.

In summary, we propose:

Hypothesis 3

The relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and green value co-creation is moderated by green exploration learning (3a). In addition, the indirect relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and economic/environmental/social performance via green value co-creation is moderated by green exploration learning such that the indirect relationship becomes stronger as green exploration learning is better (3b/3c/3d).

Hypothesis 4

The relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and green value co-creation is moderated by green exploitation learning (4a). In addition, the indirect relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and economic/environmental/social performance via green value co-creation is moderated by green exploitation learning such that the indirect relationship becomes stronger as green exploration learning is better (4b/4c/4d).

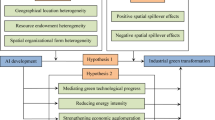

The theoretical model of this study is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Methodology

Participants and procedures

This study selected SMEs based on the most authoritative classification standards for SMEs in China: the “Regulations on the Classification of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises” (2011), jointly formulated by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and Ministry of Finance (MOF). The participants in this study were SMEs located in the southeast China from key industries, including machinery and automotive components, apparel and textiles, consumer electronics, wholesale and retail, accommodation and catering services, and other services. A total of 1,920 self-administered questionnaires were distributed to the core management teams of SMEs, typically including the general manager, head of operations, head of finance, head of technology/R&D, and head of human resources. These senior managers often possess a strategic, company-wide perspective and are able to accurately assess complex concepts such as AI capabilities and green value co-creation. We designed the questionnaire to translate these abstract concepts into concrete behaviors in their daily management practices. The questionnaire items were primarily drawn from established scales published in reputable journals. This questionnaire underwent rigorous expert validity review and pre-testing, and item wording was optimized based on feedback, ensuring strong reliability and validity.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the authors’ institution. To mitigate common method bias, the survey design incorporated multiple procedural remedies, including ensuring respondent anonymity, clarifying scale items, and counterbalancing question order; the survey instrument used a mature and neutrally worded scale that focused on describing organizational facts and activities rather than individual opinions or behaviors, thereby reducing the personal sensitivity of the questions. To ensure linguistic accuracy, the measurement scales underwent a rigorous translation process, including independent back-translation by bilingual experts to resolve discrepancies. An informed consent form was placed on the first page of each questionnaire to assure confidentiality and anonymity for participants. All participants provided their written informed consent to take part in the study. After approximately four months of data collection, a total of 702 questionnaires were returned, with a response rate of 36.6%. After eliminating poor-quality questionnaires, 632 valid questionnaires remained for further analysis. The descriptive statistics were represented in Table 1.

Measures

Artificial intelligence capabilities

Artificial intelligence capabilities (AIC) was measured using a 16-item scale74. The seven-point Likert scale was used to assess the three aspects of data, technology, and basic resources. AIC had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.935.

Green exploration learning

Green exploration learning (GER) was evaluated using a 4-item scale developed by Chen et al.75. GER had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.892.

Green exploitation learning

We used a 4-item scale developed by Chen et al.75 to measure green exploitation learning (GEI). GEI had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.896.

Green value co-creation

Green value co-creation (GVC) was assessed using an 11-item scale developed by Tian et al.68, which contains two aspects of green co-production and green value-in-use. GVC had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.936.

Economic performance

We measure economic performance (ECP) using a 4-item scale developed by Maletič et al.76. ECP had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.860.

Environmental performance

Environmental performance (ENP) was evaluated using a 4-item scale developed by Maletič et al.76. ENP had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.880.

Social performance

Social Performance (SOP) was measured using a 3-item scale adopted by Maletič et al.76. SOP had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.863.

Control variables

Following classical theoretical literature67,73,77,78,79, we controlled for firm size, years founded, and industry, as well as respondent gender, age, and educational background, to account for potential variations in firm and individual characteristics which affect the study outcomes.

Results

To ensure the robustness of the empirical results, we conducted a series of analyses in sequential order. First, we present the descriptive statistics of studied variables using SPSS 26 to provide an overview of the data. Second, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to assess the measurement model’s goodness of fit using AMOS 26. Third, we evaluated the reliability, validity, and potential common method variance of the constructs using SPSS 26. Subsequently, mediation effects were tested to test hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, H2a, H2b, and H2c using Macro Process Model 4. In addition, we used hierarchical regression in SPSS 26 to test the proposed moderating effects H3a and H4a. Finally, we examined the moderated mediation effects using Process Macro Model 9 to test our proposed hypotheses H3b, H3c, H3d, H4b, H4c, and H4d.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 demonstrated the means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, and square roots of constructs’ AVE for all variables. As we suggested, AIC, GER, GEI, GVC, ECP, ENP, and SOP were all significantly correlated with each other.

Confirmatory factory analysis

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the goodness of model fit, and the result was excellent for the 7-factors solution: χ2/df = 2.223, RMSEA = 0.044, CFI = 0.993, NFI = 0.988, IFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.982, GFI = 0.992, SRMR = 0.020 (χ2/df < 3, RMSEA < = 0.06, CFI > = 0.95, NFI > = 0.9, IFI > = 0.9, TLI > = 0.95, GFI > = 0.9, SRMR < = 0.0880,81.

Reliability, validity, and common method variance

First, the Cronbach’s alpha of all variables (AIC, GER, GEI, GVC, ECP, ENP, and SOP) were above 0.7 in Table 3, indicating an acceptable level of reliability. Second, the factor loadings of all the items (AIC, GER, GEI, GVC, ECP, ENP, and SOP) were larger than the established criterion of 0.5 proposed by Hair et al.82, and the values of average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) were greater than 0.5 and 0.7 respectively as suggested by Hair et al.82 in Table 3, showing an acceptable level of convergent validity. Third, we assessed discriminant validity of our study by comparing the square roots of AVE for each variable to their corresponding correlations, as shown in Table 2. The result indicated that every variable had a higher square root of AVE than its correlations to other variables83.

To avoid the problem of common method bias, we emphasized the anonymity and confidentiality of our study to our respondents in advance. Moreover, this study made questionnaires concise and understandable. In addition, we used Harman’s one factor test, which indicated that the variance explained by a single factor is only 33.84%, which under the suggested threshold of 50%.

Mediation analysis

We used Process macro model 4 in SPSS 26 to evaluate the mediating effect of GSV between AIC and ECP/ENP/SOP. The results are presented in Table 4.

As presented in Table 4, the total effects of AIC on ECP/ENP/SOP were all significant, thus supporting H1a/H1b/H1c. After adding GVC as a mediator, the direct effect and indirect effect of AIC on ECP/ENP/SOP were all significant, indicating partial mediating effects of GSV between AIC and ECP/ENP/SOP. Therefore, H2a, H2b, and H2c were all supported.

Moderation analysis

We used hierarchical regression in SPSS 26 to test hypotheses H3a and H4a. Table 5 indicated that the relationship between AIC and GVC is moderated by GER and the relationship between AIC and GVC is also moderated by GEI.

Figure S1 in the supplementary material illustrated that the positive relationship between AIC and GVC was strongest while GER was at its highest level and Figure S2 displayed that the same relationship was also strongest while GEI was at its highest level. Therefore, H3a and H4a were both supported.

Moderated mediation analysis

We used PROCESS macro model 9 developed by Hayes84 in SPSS 26 to examine the hypothesized moderated mediation effects. Table 6 showed the index of moderated mediation effects for GER and GEI in the AIC-GVC-ECP/ENP/SOP links.

The conditional indirect effects of AIC on ECP/ENP/SOP via GVC were all significantly moderated by GER and as GEI. As presented in Table 6, the confidence intervals of both indices for GER and GEI did not contain zero, hence, H3b, H3c, H3d, H4b, H4c, and H4d were all supported. Table 7 presented the conditional indirect effects of AIC to ECP/ENP/SOP at specific levels of GER and GEI.

The moderated mediation effects were also illustrated using the Johnson-Neyman graph in Figure S3, S4, and S5 in the supplementary material, and the indirect effects of AIC on ECP/ENP/SOP through GVC were strongest while both GER and GEI were at their highest level. In addition, we also evaluated t-values and path coefficients to confirm the moderated mediation effects, as illustrated in Fig. 3, Therefore, all hypotheses were supported.

Discussion

Although the research of green AI has made significant progress over the past five years, there still remain many critical theoretical gaps, hindering global scholars’ comprehensive understanding of the green AI-enabled economy. First, existing literature primarily focuses on large manufacturing enterprises, lacking in-depth theoretical models exploring the balance between survival pressures and environmental investment for SMEs in developing nations85. Second, while green AI research spans multiple disciplines, including computer science, management, and environmental science, however, interdisciplinary theoretical integration is insufficient, with many studies at the conceptual level, and failing to propose practical solutions31. Third, although green AI has shown great potential in improving environmental performance86, optimizing resources87, and low-carbon transformation88, key issues such as the construction of co-creation mechanisms and innovation of business models still need to be explored in depth.

To further illustrate these issues, this study is presented from two theoretical perspectives: The first perspective focuses on comprehensive understanding of Artificial Intelligence Capabilities, following prior research on AIC and business model innovation89, AI-enabled CBM90, organizational performance91. In addition, we explore an unknown mechanism by which AIC leads to ECP/ ENP/SOP in digital era. In this respect, we emphasize the significance of AIC92,93,94, and fill the research gap from value co-creation perspective. The second perspective concentrates on moderated mediation effects of green ambidextrous learning, including two aspects: green exploration learning and green exploitation learning. As some scholars believe that enterprise ambidextrous learning may be contradictory95,96, the moderated mediation role of green ambidextrous learning in AIC-GVC-ECP/ENP/SOP link is novel. The indirect effects of AIC on ECP/ENP/SOP via GVC are both strongest when GER, GEI are at highest level. In our study, these two abilities are complementary and mutually reinforcing. The possible reasons for this are as follows:

It is inevitable that, if SMEs blindly pursue both green exploratory learning and green exploitative learning, it is indeed possible to lead to resource shortages97. The key lies in whether managers can flexibly master the strategic balance between the two. Empirical evidence further suggests an interactive effect between green exploratory learning and green exploitative learning. For example, Shi et al.98 indicated that exploration and exploitation are positively correlated with each other, and both of them can boost firm performance. Rintala et al.99 suggested that both explorative and exploitative strategy could enhance the relationship between environmental and financial performance. Wei et al.100 found that explorative and exploitative IT capabilities are complementary in moderating the link between collaborative planning and firm performance but substitutive in moderating the relationship between information sharing and firm performance. The cost savings and profits gained in SMEs through green exploitative learning can provide valuable financial support for green exploratory learning. Furthermore, when existing green exploitative learning reaches a bottleneck, exploratory learning can help companies gain insight into future green trends and policy directions, thereby guiding the strategic direction of current exploitative learning. Specifically, green exploration learning was found to have a stronger moderating effect than exploitation learning, suggesting a significant moderating effect on the relationship between AI capabilities and green value co-creation by green exploration learning (β = 0.209, p < 0.001), and green exploitation learning (β = 0.116, p < 0.001). We believe that SMEs at different stages have different green transformation goals, resource reserves, and risk tolerance, and the ratio of resource input between the two will show an alternating emphasis as the enterprise’s development stage changes.

This study focuses on green value co-creation in SMEs by tackling the following issues: (1) How does artificial intelligence capabilities influence SMEs’ triple bottom line performance? (2) What is the role of green value co-creation in promoting the coordinated development of digitalization and sustainability in China? (3) In what ways do green ambidextrous learning influence SMEs today? To solve these problems, we take a moderated-mediation exam from 632 managers in southeast China. By doing so, we demonstrate both theoretical and practical significance for environmental protection, social advancement and corporate governance in SMEs.

The key findings were as follows: Artificial intelligence capabilities has a positive impact on economic/environmental/social performance (H1). In the context of the relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and economic/environmental/social performance, green value co-creation serves as a mediator. To be more precise, artificial intelligence capabilities contributes to economic/environmental/social performance via green value co-creation (H2a, H2b, and H2c). Notably, we also emphasize the moderating role of green exploration learning and green exploitation learning, indicating that better green exploration learning and green exploitation learning could strengthen the relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and green value co-creation (H3a and H4a). Moreover, the relationship between artificial intelligence capabilities and economic/environmental/social performance through green value co-creation are all strongest while green exploration learning and green exploitation learning are at their highest levels (H3b, H3c, H3d, H4b, H4c, and H4d).

In summary, this research offers fresh theoretical insights into AIC-ECP/ ENP/SOP links based on above results. Moreover, we have thoroughly analyzed the theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

First, this article takes “green” value co-creation as its research perspective, enriches the existing research on value co-creation in China, also in other developing countries. While some scholars have started to explore the relationship between artificial intelligence and value co-creation in recent years, research on AI in “green” value co-creation has not received sufficient attention. Furthermore, the literature on value co-creation has established a mature theoretical system, and widely used in various fields15,101,102, research on “green” value co-creation has advanced relatively slowly. Future scholars should pay greater attention to the exploration of green value co-creation from an interdisciplinary perspective.

Second, we enhance the precision of the RBV theory by indicating that artificial intelligence capabilities influence economic/environmental/social performance in SMEs. These results integrate new perspective into RBV theory49,103,104 by considering artificial intelligence capabilities as a unique and scarce resource105,106, which could improve economic/environmental/social performance for SMEs. By doing so, we establish the internal driving mechanism of AIC-GVC-ECP/ENP/SOP for SMEs, offering referable insights for future research on AI research in green value co-creation.

Third, this study extends the organizational ambidexterity theory by providing a novel viewpoint on green ambidextrous learning. As we mentioned above, there is no research found the relationship between green ambidextrous learning, artificial intelligence capabilities, green value co-creation, and corporate performance. This study introduces green organizational ambidextrous learning (green exploration learning and green exploitation learning) as boundary conditions into the green value co-creation mechanism for SMEs. By doing this, we empirically validate the significance of green exploratory and exploitation learning under resource constraints in SMEs. In addition, this study verified the dynamic path of green ambidextrous learning to green value co-creation in the digital economy, broadening the application and innovation of organizational learning theory in the context of green AI.

Finally, we stress the value of a good fit by exhibiting the relationships among AIC, GER, GEI, GVC, ECP, ENP, and SOP. This study extends three theoretical perspectives: RBV, stakeholder theory and organizational learning theory by taking a moderated-mediation exam in southeast China, Consequently, a dynamic theoretical framework and theoretical frontiers of green value co-creation for AI-enabled digital-green dual transformation can be obtained.

Practical implications

First, this paper leverages artificial intelligence technologies to explore new linkages between the green economy and digital economy for SMEs, providing insights for the construction of a green, intelligent, and digital ecological civilization. The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technology has unleashed immeasurable potential across diverse industries. From the perspective of finance107, economy108, agriculture109, energy110, and education111, data resources have emerged as the cornerstone of sustaining competitive edge in business operations. Artificial intelligence technology is bringing irreplaceable creation and changes to society. Leveraging artificial intelligence technologies to advance digital ecological civilization also holds broad development prospects.

Second, this study investigates green value co-creation in Chinese SMEs, offering crucial implications for sustainable development112,113. As we mentioned above, SMEs have the characteristics of resource shortage, small scale, and poor risk resistance. Green value co-creation will fill the SMEs’ skill gap through collaborative with each other, strengthen risk resilience by digital green systems, integrate composite resources such as policy subsidies, technical competence, and market channels, and participate digital ecological alliance to foster a win-win situation.

Third, the unique and irreplaceable role of green ambidextrous learning for SMEs with limited resources should not be ignored. Green exploration learning helps companies develop new green AI technologies, promote the research and development of environmental technologies, and enhance their long-term competitiveness. Green exploitation learning helps companies optimize existing green AI technologies, reduce operating costs, and improve resource utilization.

Conclusions

Main results

This paper draws on the RBV, stakeholder theory, and organizational learning theory to construct a theoretical framework for green value co-creation enabled by artificial intelligence (AI). First, based on the RBV, a firm’s AI capabilities (tangible, intangible, and human resources) are considered competitive advantages and resources. Second, according to stakeholder theory, the mechanism for green value co-creation in SMEs is established. Third, drawing on organizational learning theory, the moderating role of green organizational ambidexterity (green exploration learning and green exploitation learning) is explained, as well as the overall process by which AI drives green value co-creation and promotes performance improvement. This paper illustrates the interactive process of digitalization and sustainability, establishing the internal driving mechanism of “AI capabilities-green value co-creation-firm performance”. The research findings will provide insights for SMEs in the AI era.

Limitations and future recommendations

First, the reliance on self-reported data from a single source at one point in time introduces the possibility of common method bias, including social desirability bias. Respondents may have provided answers they perceived as more socially acceptable, particularly concerning “green” and “AI” initiatives. In addition, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish causal inferences and the need for longitudinal research is pressing. Our study captures short-term outcomes, however, green AI’s full impact on SMEs, including how the perception biases might evolve, can only be understood over a longer period. Longitudinal studies will provide valuable insights into the sustained effects of green AI adoption and offer solid theoretical support for its long-term implementation.

Another limitation is the cross-national applicability of green AI solutions. Most studies on green AI are concentrated are based on specific and single national contexts, with a limited international perspective. Different countries have varied political systems, economic conditions, cultural values, technological infrastructure, influencing the efficiency and effectiveness of green AI technologies. Future research could explore green AI in multiple countries and multiple scenarios.

Finally, as we mentioned above, most of green AI research only focuses on green AI technology in enterprises but have not yet fully embed green AI into all aspects of enterprise operations. Future research should validate the results of longitudinal studies, and actively develop interdisciplinary solutions. The longitudinal studies research must be strengthened, such as the long-term effects of green AI technology application, to provide solid theoretical support for the implementation of green AI in SMEs. Furthermore, a dynamic adaptive model for SMEs should be established by deeply integrating theories from multiple disciplines, such as environmental science, management, and computer science.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmed, S., Ashrafi, D. M., Paraman, P., Dhar, B. K. & Annamalah, S. Behavioural intention of consumers to use app-based shopping on green tech products in an emerging economy. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manage. 41, 1496–1518 (2023).

Khekare, G., Khetan, U. & Doshi, P. N. Artificial intelligence (AI)-Driven traffic solutions: Enhancing green transportation through predictive analytics and deep learning. in Driving Green Transportation System Through Artificial Intelligence and Automation (ed Khang, A.) 319–334 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72617-0_17. (2025).

Lakhouit, A. Revolutionizing urban solid waste management with AI and iot: A review of smart solutions for waste collection, sorting, and recycling. Results Eng. 104018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104018 (2025).

Ma, Y., Chen, X., Wang, L. & Yang, J. Study on smart home energy management system based on artificial intelligence. J. Sensors 9101453 (2021).

Guo, L., Xu, L., Wang, J. & Li, J. Digital transformation and financing constraints of smes: Evidence from China. Asia-Pacific J. Acc. Econ. 31, 966–986 (2024).

Zhang, B., Argheyd, K., Molz, R. & He, B. A new business ecosystem for SMEs development in china: Key-node industry and industrial net. J. Small Bus. Manage. 61, 3046–3076 (2023).

Chang, C. H. Do green motives influence green product innovation? The mediating role of green value co-creation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 26, 330–340 (2019).

Borah, P. S., Dogbe, C. S. K., Dzandu, M. D. & Pomegbe, W. W. K. Forging organizational resilience through green value co-creation: The role of green technology, green operations, and green transaction capabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32, 5734–5747 (2023).

Almansour, M. How do green intellectual and co-creational capitals drive artificial intelligence innovation and green innovation in start-ups? Eur. J. Innov. Manage. 28, 1649–1666 (2025).

Han, M. & Xu, B. Distance with customers effects on green product innovation in smes: A way through green value Co-creation. Sage Open. 11, 21582440211061539 (2021).

Huang, C. H. & Huang, Y. C. Exploring the linkages among green digital transformation capability, ambidextrous green learning and sustainability performance: A case study of manufacturing firms in Taiwan. J. Manuf. Technol. Manage. 35, 1103–1123 (2024).

Wang, J., Xue, Y., Sun, X. & Yang, J. Green learning orientation, green knowledge acquisition and ambidextrous green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 250, 119475 (2020).

Baquero, A. Organizational factors, ambidextrous innovation, absorptive capacity, and a firm’s green competitive advantage. Manag. Decis. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2024-0789 (2025). doi:10.1108/MD-04-2024-0789.

Galvagno, M. & Dalli, D. Theory of value co-creation: a systematic literature review. Managing Service Qual. 24, 643–683 (2014).

John, S. P. & Supramaniam, S. Value co-creation research in tourism and hospitality management: A systematic literature review. J. Hospitality Tourism Manage. 58, 96–114 (2024).

Ranjan, K. R. & Read, S. Value co-creation: concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 44, 290–315 (2016).

Jiang, L. et al. Promoting energy saving and emission reduction benefits in small and medium-sized enterprises supply chains through green finance - Evidence based on artificial intelligence intervention. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 102, 104112 (2025).

Rashid, A., Baloch, N., Rasheed, R. & Ngah, A. H. Big data analytics-artificial intelligence and sustainable performance through green supply chain practices in manufacturing firms of a developing country. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manage. 16, 42–67 (2025).

Wang, Q., Sun, T. & Li, R. Does artificial intelligence (AI) enhance green economy efficiency? The role of green finance, trade openness, and R&D investment. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 12 (2025).

Lin, B. & Zhu, Y. Does AI elevate corporate ESG performance? A supply chain perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 34, 586–597 (2025).

Wang, X., He, T., Wang, S. & Zhao, H. The impact of artificial intelligence on economic growth from the perspective of population external system. Social Sci. Comput. Rev. 43, 129–147 (2025).

Akinsemolu, A. A. & Green AI in education: can artificial intelligence promote sustainable learning? J. Theoretical Empir. Stud. Educ. 10, 596–629 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Shi, J. & Huang, Y. Do artificial intelligence capabilities impact sustainability-oriented innovation performance: Exploring the role of green intellectual capital and learning orientation. J. Intellect. Capital. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-10-2024-0315 (2025).

Padhi, S. & Biswal, K. K. Artificiai intelligence: Prospects and challenges. Mind and Machines: The Psychology of Artificial Intelligence 94 (2024).

Ma, W. Artificial intelligence-assisted decision-making method for legal judgment based on deep neural network. Mobile Inform. Syst. 4636485 (2022).

Xia, Q. et al. A self-determination theory (SDT) design approach for inclusive and diverse artificial intelligence (AI) education. Comput. Educ. 189, 104582 (2022).

Salomon, C., Heinz, K., Aronson-Ramos, J. & Wall, D. P. An analysis of the real world performance of an artificial intelligence based autism diagnostic. Sci. Rep. 15, 29503 (2025).

Cicek, M., Gursoy, D. & Lu, L. Adverse impacts of revealing the presence of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in product and service descriptions on purchase intentions: The mediating role of emotional trust and the moderating role of perceived risk. J. Hospitality Mark. Manage. 34, 1–23 (2025).

Mhohamdi, H. et al. Advancing computational evaluation of adsorption via porous materials by artificial intelligence and computational fluid dynamics. Sci. Rep. 15, 29691 (2025).

Viola, T. W., de Carvalho, M. T., Padoin, R. C. P. K., Kampff, A. J. C. & Padoin, A. V. Evaluation using artificial intelligence shows post pandemic differences in oral reading fluency between Brazilian public and private school students. Sci. Rep. 15, 30131 (2025).

Verdecchia, R., Sallou, J. & Cruz, L. A systematic review of green AI. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 13, e1507 (2023).

Lee, D. & Lin, C. Universal artificial intelligence workflow for factory energy saving: Ten case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 468, 143049 (2024).

Rojek, I. et al. Internet of things applications for energy management in buildings using artificial intelligence—A case study. Energies 18, 1706 (2025).

Talaat, M., Elkholy, M. H., Alblawi, A. & Said, T. Artificial intelligence applications for microgrids integration and management of hybrid renewable energy sources. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 10557–10611 (2023).

Wei, R. & Pardo, C. Artificial intelligence and smes: How can B2B SMEs leverage AI platforms to integrate AI technologies? Ind. Mark. Manage. 107, 466–483 (2022).

Wang, J., Lu, Y., Fan, S., Hu, P. & Wang, B. How to survive in the age of artificial intelligence? Exploring the intelligent transformations of SMEs in central China. Int. J. Emerg. Markets. 17, 1143–1162 (2021).

Badghish, S. & Soomro, Y. A. Artificial intelligence adoption by SMEs to achieve sustainable business performance: Application of Technology–Organization–Environment framework. Sustainability 16, 1864 (2024).

Farmanesh, P., Solati Dehkordi, N., Vehbi, A. & Chavali, K. Artificial intelligence and green innovation in small and Medium-Sized enterprises and Competitive-Advantage drive toward achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability 17, 2162 (2025).

Tabbakh, A. et al. Towards sustainable AI: A comprehensive framework for green AI. Discov Sustain. 5, 408 (2024).

Dawra, S., Pathak, V. & Sharma, S. Artificial intelligence (AI) and green human resource management (GHRM) practices: A systemic review. Green. Management: New. Paradigm World Bus. 83-96 https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83797-442-920241006 (2024).

Odugbesan, J. A., Aghazadeh, S., Qaralleh, R. E. A. & Sogeke, O. S. Green talent management and employees’ innovative work behavior: The roles of artificial intelligence and transformational leadership. J. Knowl. Manage. 27, 696–716 (2022).

Chowdhury, S. et al. Unlocking the value of artificial intelligence in human resource management through AI capability framework. Hum. Resource Manage. Rev. 33, 100899 (2023).

Alzoubi, Y. I. & Mishra, A. Green artificial intelligence initiatives: Potentials and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 468, 143090 (2024).

Huang, X., Ullah, M., Wang, L., Ullah, F. & Khan, R. Green supply chain management practices and triple bottom line performance: Insights from an emerging economy with a mediating and moderating model. J. Environ. Manage. 357, 120575 (2024).

Hussain, N., Rigoni, U. & Orij, R. P. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: Analysis of triple bottom line performance. J. Bus. Ethics. 149, 411–432 (2018).

Bonfiglioli, A., Crinò, R. & Gancia, G. Firms and economic performance: A view from trade. Eur. Econ. Rev. 172, 104912 (2025).

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Muñoz-Bullón, F., Requejo, I. & Sanchez-Bueno, M. J. Ethical correlates of family control: Socioemotional Wealth, environmental Performance, and financial returns. J. Bus. Ethics. 198, 893–917 (2025).

Chliova, M., Cacciotti, G., Kautonen, T. & Pavez, I. Reacting to criticism: What motivates top leaders to respond substantively to negative social performance feedback? J. Bus. Res. 186, 115005 (2025).

de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., Laguir, I., Stekelorum, R. & Gupta, S. The nexus of artificial intelligence and sustainability performance: Unveiling the impact of supply chain transparency and customer pressure on ethical conduct. J. Environ. Manage. 379, 124847 (2025).

Orazalin, N. & Mahmood, M. Economic, environmental, and social performance indicators of sustainability reporting: Evidence from the Russian oil and gas industry. Energy Policy. 121, 70–79 (2018).

Strezov, V., Evans, A. & Evans, T. J. Assessment of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of the indicators for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 25, 242–253 (2017).

Alsayegh, M. F., Rahman, A., Homayoun, S. & R. & Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability 12, 3910 (2020).

Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 17, 99–120 (1991).

Wamba-Taguimdje, S. L., Wamba, F., Kala Kamdjoug, S., Tchatchouang Wanko, C. E. & J. R. & Influence of artificial intelligence (AI) on firm performance: The business value of AI-based transformation projects. Bus. Process. Manage. J. 26, 1893–1924 (2020).

Sullivan, Y. & Fosso Wamba, S. Artificial intelligence and adaptive response to market changes: A strategy to enhance firm performance and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 174, 114500 (2024).

Santos, M. R. & Carvalho, L. C. AI-driven participatory environmental management: Innovations, applications, and future prospects. J. Environ. Manage. 373, 123864 (2025).

Arashpour, M. AI explainability framework for environmental management research. J. Environ. Manage. 342, 118149 (2023).

Fosso Wamba, S. Impact of artificial intelligence assimilation on firm performance: The mediating effects of organizational agility and customer agility. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 67, 102544 (2022).

Wang, Y., Zhang, R., Yao, K. & Ma, X. Does artificial intelligence affect the ecological footprint? Evidence from 30 provinces in China. J. Environ. Manage. 370, 122458 (2024).

Friedman, A. L. & Miles, S. Developing stakeholder theory. J. Manage. Stud. 39, 1–21 (2002).

Alves, H., Fernandes, C. & Raposo, M. Value co-creation: Concept and contexts of application and study. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1626–1633 (2016).

Lu, X., Ren, F., Wang, X. & Meng, H. How gamified interactions drive users’ green value Co-Creation behaviors: An empirical study from China. Sustainability 16, 3512 (2024).

Yin, S. & Zhao, Y. Digital green value co-creation behavior, digital green network embedding and digital green innovation performance: Moderating effects of digital green network fragmentation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2024).

Li, S., Peng, G., Xing, F., Zhang, J. & Zhang, B. Value co-creation in industrial AI: The interactive role of B2B supplier, customer and technology provider. Ind. Mark. Manage. 98, 105–114 (2021).

Leone, D., Schiavone, F., Appio, F. P. & Chiao, B. How does artificial intelligence enable and enhance value co-creation in industrial markets? An exploratory case study in the healthcare ecosystem. J. Bus. Res. 129, 849–859 (2021).

Manser Payne, E. H., Peltier, J. & Barger, V. A. Enhancing the value co-creation process: Artificial intelligence and mobile banking service platforms. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 15, 68–85 (2021).

Kim, D. W., Trimi, S., Hong, S. G. & Lim, S. Effects of co-creation on organizational performance of small and medium manufacturers. J. Bus. Res. 109, 574–584 (2020).

Tian, H. H., Huang, S. Z. & Cheablam, O. How green value co-creation mediates the relationship between institutional pressure and firm performance: A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32, 3309–3325 (2023).

Argyris, C. & Schön, D. A. Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reis 345–348. https://doi.org/10.2307/40183951 (1997).

Lyu, C., Dong, H., Wan, P. & Liu, J. Ambidextrous learning and green competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises: The role of green value Co-Creation and green strategic orientation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. 32, 7161–7179 (2025).

Mishra, A. N. & Pani, A. K. Business value appropriation roadmap for artificial intelligence. VINE J. Inform. Knowl. Manage. Syst. 51, 353–368 (2020).

Zhang, H., Gupta, S., Sun, W. & Zou, Y. How social-media-enabled co-creation between customers and the firm drives business value? The perspective of organizational learning and social capital. Inf. Manag. 57, 103200 (2020).

Obeso, M., Hernández-Linares, R., López-Fernández, M. C. & Serrano-Bedia, A. M. Knowledge management processes and organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational learning. J. Knowl. Manage. 24, 1859–1880 (2020).

Abou-Foul, M., Ruiz-Alba, J. L. & López-Tenorio, P. J. The impact of artificial intelligence capabilities on servitization: The moderating role of absorptive capacity-A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 157, 113609 (2023).

Chen, Y. S., Chang, C. H. & Lin, Y. H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared Vision, green absorptive Capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 6, 7787–7806 (2014).

Maletič, M., Maletič, D., Dahlgaard, J. J., Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. & Gomišček, B. Effect of sustainability-oriented innovation practices on the overall organisational performance: An empirical examination. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excellence. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1064767 (2016). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/

Li, L. Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Ind. Mark. Manage. 104, 28–37 (2022).

Kacperczyk, O., Younkin, P. A. & Founding Penalty Evidence from an audit study on Gender, Entrepreneurship, and future employment. Organ. Sci. 33, 716–745 (2022).

Chen, P. & Hao, Y. Digital transformation and corporate environmental performance: The moderating role of board characteristics. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. 29, 1757–1767 (2022).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Ed. xvii, 534The Guilford Press, New York, NY, US, (2016).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis (Pearson Education Limited, 2013).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Hayes, A. F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 50, 1–22 (2015).

Al Koliby, I. S., Al-Swidi, A. K., Al-Hakimi, M. A. & Farhan, S. A. G. How green knowledge-oriented leadership drives green innovation in smes: The mediating role of environmental strategy and the moderating role of green AI capability. Cogent Bus. Manage. 12, 2520914 (2025).

Wang, A., Luo, K. & Nie, Y. Can artificial intelligence improve enterprise environmental performance: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manage. 370, 123079 (2024).

Bolón-Canedo, V., Morán-Fernández, L., Cancela, B. & Alonso-Betanzos, A. A review of green artificial intelligence: Towards a more sustainable future. Neurocomputing 599, 128096 (2024).

Liu, T. & Zhou, B. The impact of artificial intelligence on the green and low-carbon transformation of Chinese enterprises. Manag. Decis. Econ. 45, 2727–2738 (2024).

Sjödin, D., Parida, V., Palmié, M. & Wincent, J. How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. J. Bus. Res. 134, 574–587 (2021).

Madanaguli, A., Sjödin, D., Parida, V. & Mikalef, P. Artificial intelligence capabilities for circular business models: Research synthesis and future agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 200, 123189 (2024).

Mikalef, P. et al. Examining how AI capabilities can foster organizational performance in public organizations. Government Inform. Q. 40, 101797 (2023).

Asiaei, K., O’Connor, N. G., Barani, O. & Joshi, M. Green intellectual capital and ambidextrous green innovation: The impact on environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32, 369–386 (2023).

Mansoor, A., Jahan, S. & Riaz, M. Does green intellectual capital spur corporate environmental performance through green workforce? J. Intellect. Capital. 22, 823–839 (2021).

Riaz, A., Cepel, M., Ferraris, A., Ashfaq, K. & Rehman, S. U. Nexus among green intellectual capital, green information systems, green management initiatives and sustainable performance: a mediated-moderated perspective. J. Intellect. Capital (2024).

Shi, Y., Van Toorn, C. & McEwan, M. Exploration–Exploitation: How business analytics powers organisational ambidexterity for environmental sustainability. Inform. Syst. J. 34, 894–930 (2024).

Tang, Y. & Yang, S. Mineral resource sustainability in the face of the resource exploitation and green recovery: Challenges and solutions. Resour. Policy. 88, 104535 (2024).

Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G. & Shalley, C. E. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. AMJ 49, 693–706 (2006).

Shi, X., Su, L. & Cui, A. P. A meta-analytic study on exploration and exploitation. J. Bus. Industrial Mark. 35, 97–115 (2019).

Rintala, O. et al. Revisiting the relationship between environmental and financial performance: The moderating role of ambidexterity in logistics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 248, 108479 (2022).

Wei, S., Ke, W., Liu, H. & Wei, K. K. Supply chain information integration and firm performance: Are explorative and exploitative IT capabilities complementary or substitutive? Decis. Sci. 51, 464–499 (2020).

Buhalis, D., Lin, M. S. & Leung, D. Metaverse as a driver for customer experience and value co-creation: Implications for hospitality and tourism management and marketing. IJCHM 35, 701–716 (2023).

Saha, V., Goyal, P. & Jebarajakirthy, C. Value co-creation: A review of literature and future research agenda. J. Bus. Industrial Mark. 37, 612–628 (2022).

Subramanyam, R. & Anand, G. Carbon management practices and associations with firm performance. J. Environ. Manage. 391, 126414 (2025).

Arhavbarien, J., Duan, Y. & Ramanathan, R. An investigation of antecedents and consequences of green value internalisation among sampled UK enterprises. J. Environ. Manage. 365, 121501 (2024).

Chedrawi, C. & Atallah, Y. Artificial intelligence in the defense sector: An RBV and isomorphism perspectives to the case of the Lebanese armed forces. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 16, 279–293 (2022).

Sandeep, M. M., Lavanya, V. & Balakrishnan, J. Leveraging AI in recruitment: enhancing intellectual capital through resource-based view and dynamic capability framework. J. Intell. Capital (2025). https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-05-2024-0155

Yeo, W. J. et al. A comprehensive review on financial explainable AI. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58, 189 (2025).

Song, Z. & Deng, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency under integrated governance. Sci. Rep. 15, 25919 (2025).

Han, S. & Sun, X. Research on the impact of artificial intelligence applications on agricultural green development. Sci. Rep. 15, 30255 (2025).

Zeng, J. & Wang, T. The impact of china’s artificial intelligence development on urban energy efficiency. Sci. Rep. 15, 24129 (2025).

Yim, I. H. Y. & Su, J. Artificial intelligence (AI) learning tools in K-12 education: A scoping review. J. Comput. Educ. 12, 93–131 (2025).

Re, B. & Magnani, G. Value co-creation in circular entrepreneurship: An exploratory study on born circular SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 147, 189–207 (2022).

Yousaf, Z. Go for green: green innovation through green dynamic capabilities: Accessing the mediating role of green practices and green value co-creation. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 54863–54875 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the funding of Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. [2024J08240]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: Xin Yan, Yu-Shan Chen; (II) Administrative support: Xin Yan, Yuning Lin; (III) Provision of study materials: Xin Yan, Yu-Shan Chen; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Xin Yan, Yuning Lin; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade, all research methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participants before the start of the program. We confirm that all the experiment is in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations such as the declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, X., Chen, YS. & Lin, Y. Unpacking the mechanisms and consequences of artificial intelligence in enabling green value co-creation for SMEs. Sci Rep 15, 42336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26420-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26420-3