Abstract

Accurate estimation of inverse kinematics and dynamics is essential for precise robotic manipulator control. Traditional analytical models, while effective for nominal conditions, often struggle to capture complex nonlinearities and unmodeled dynamics, necessitating compensatory controllers. However, these combined approaches can become computationally intensive and prone to redundancy. Conventional machine learning methods have shown promise in error compensation but typically demand large datasets and incur high computational costs, particularly when addressing high-dimensional state spaces. To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes a novel data-efficient framework based on Liquid Neural Networks (LNNs) for learning inverse kinematics and dynamics directly from simulation platform measurements. The inherent capability of LNN to model temporal dependencies and adapt continuously to evolving system dynamics enables accurate approximation of nonlinear manipulator behavior without reliance on extensive offline training. The proposed method is validated on two distinct robotic platforms—a UR5e manipulator with 6 DoF and a WAM manipulator with 7 DoF using both simulation and real-world trajectory data acquired through a targeted sampling strategy. Both simulation and experimental evaluations with previously unseen trajectories demonstrate that the ILNN-based approach achieves high-fidelity approximation of both inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics, delivering superior generalization and robustness compared to conventional analytical and data-driven methods. These results highlight the potential of LNNs as an efficient and scalable solution for real-time robot control in dynamic and uncertain environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate identification of the inverse kinematics (IK) and inverse dynamics (ID) of robotic manipulators is fundamental for achieving high-precision motion control and robust trajectory tracking. Other contemporary works have employed neural network learning algorithms to achieve high precision position control and to actively attenuate drift in robotic manipulators1. Reliable IK and ID models enable the design of controllers with reduced feedback gains, improved energy efficiency, and enhanced stability margins. Existing research in this domain can be broadly categorized into analytical approaches and numerical, data-driven approaches.

Analytical methods derive explicit mathematical models from first principles, employing rigid-body dynamics, Lagrangian formulations, or Newton–Euler recursive algorithms2,3,4. While these methods are interpretable and computationally efficient at runtime, their accuracy is contingent upon idealized assumptions, precise parameter identification, and exact calibration. Recent efforts have pursued high fidelity analytical models through comprehensive electro mechanical characterization and parameter identification for specific platforms like the UR5e robot5. In practice, unmodeled effects such as joint friction, compliance, payload variation, and contact interactions can introduce significant modeling errors. Analytical models may also suffer from singularities, scalability challenges for high-degree-of-freedom (DOF) or closed-chain manipulators, and a substantial engineering burden when adapting to new platforms.

Numerical methods, by contrast, leverage empirical data to approximate the system’s input–output relationships. With sufficiently rich datasets, they can capture unmodeled dynamics and uncertainty, yielding more accurate predictions than purely analytical models6. However, their performance depends heavily on the availability of high-quality, representative data. For many robotic systems, especially in real-world environments, large-scale data collection is expensive, time-consuming, and sometimes infeasible, which limits the applicability of conventional deep learning–based approaches.

Over the past two decades, a variety of learning-based techniques have been explored for IK and ID modeling. Early work employed radial basis function (RBF) networks, multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), and support vector regressors (SVRs) to learn pose–joint mappings7,8. While these methods reduced the need for manual derivations, they required dense sampling of the configuration space, generalized poorly to unseen poses, and did not inherently model temporal dependencies or enforce kinematic constraints. More recent efforts have applied deep architectures, including residual networks, recurrent models (LSTMs, GRUs), neural ordinary differential equations (Neural ODEs), and Transformer-based sequence models9,10,11, to capture nonlinear dynamics. These approaches improve expressiveness but often require long offline training cycles, exhibit sensitivity to distribution shifts, and can introduce inference latency that is prohibitive for high-frequency torque control loops.

Probabilistic models such as Gaussian Processes (GPs) have been adopted for their calibrated uncertainty estimates and strong small-data performance12, but their cubic complexity in dataset size hinders scalability to high-dimensional manipulators, and approximate variants often compromise accuracy. Reinforcement learning (RL) has also been explored for both kinematic and dynamic adaptation13,14, but it typically depends on large-scale simulation, domain randomization, and costly sim-to-real transfer, with limited interpretability and safety guarantees. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and differentiable physics simulators15,16 incorporate physical priors into learning, improving data efficiency but requiring accurate differentiable contact models and facing difficulties with discontinuities.

Generative models, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and diffusion models17,18,19, have been applied to data augmentation for IK/ID learning. While these methods can enrich limited datasets, they risk introducing synthetic artifacts, mode collapse, and mismatches between generated and real-world distributions, which can bias the learned dynamics models. Graph neural networks (GNNs) and SE(3)-equivariant networks20,21 have shown promise for encoding geometric constraints, but their high computational demands and focus on perception tasks have limited their adoption in low-latency control.

To address these challenges, this paper introduces a Liquid Neural Network (LNN)–based framework for learning IK and ID from limited real-world data. LNNs22 are continuous-time recurrent neural architectures with adaptive, input-dependent dynamics, offering strong temporal modeling capabilities, high data efficiency, and rapid adaptation to distribution shifts. Unlike static feedforward networks, LNNs can evolve their internal states and parameters online, enabling high-fidelity modeling under changing conditions without full retraining. This makes them particularly suitable for deployment in robotic systems where both real-time adaptability and low computational overhead are critical.

The proposed approach trains LNN models using targeted sampling strategies to maximize the representativeness of the collected trajectories. We validate the framework on two robotic platforms: one is a 6-DOF UR5e manipulator and another is a 7-DOF WAM manipulator, under both seen and unseen motion conditions. Comparative evaluations demonstrate that the LNN-based models achieve superior prediction accuracy, robustness to unmodeled dynamics, and faster adaptation compared to analytical baselines, traditional deep networks, and generative augmentation methods.

The primary contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

We propose a novel Invertible Liquid Neural Network–based framework for learning inverse kinematics and dynamics from limited real-world data, enabling real-time adaptation without exhaustive offline training.

-

We introduce a targeted data acquisition and sampling strategy that maximizes information gain, reducing the training data requirement while preserving model fidelity.

-

We experimentally validate the proposed method on two distinct high-DoF robotic platforms, demonstrating superior generalization to unseen trajectories compared to analytical and traditional deep learning baselines.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Preliminaries” formalizes inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics, introduces notation, and reviews neural network foundations and liquid neural networks relevant to our approach. Section “Invertible liquid neural networks (ILNNs)” presents the proposed Invertible Liquid Neural Network (ILNN): we derive the liquid cell dynamics, describe the invertible coupling architecture, and detail the bi-directional training objectives and algorithms used for forward prediction and inverse inference. Section “Experimental results” specifies the software/hardware stack, simulation platform, datasets, baselines, and evaluation metrics, and then reports comparative results on the UR5e and WAM manipulators. Section “Conclusion” concludes with a discussion of limitations and future research directions.

Preliminaries

Inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics

Kinematics defines the relationship between coordinates in the joint space \(\mathbf{q}\) and those in the task space x. The forward kinematics (FK) problem maps joint coordinates to task space coordinates as \(FK: \mathbf{q} \mapsto \mathbf{x}\), while the inverse kinematics (IK) problem defines the mapping in the opposite direction as \(IK: \mathbf{x} \mapsto \mathbf{q}\).

Several techniques exist for solving kinematics, such as geometric formulations and the Denavit–Hartenberg (DH) convention2. Although the DH approach provides a systematic representation, the associated closed-form equations may exhibit singularities and nonlinearities, which increase the computational cost of IK solutions in complex configurations.

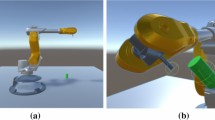

In this study, two robotic platforms are used for experimental validation: a 6-DOF UR5e (developed by Universal Robots). manipulator and a 7-DOF WAM manipulator (developed by Barrett Technology). The IK and ID models for UR5e and WAM robot are derived using the DH parameterization as shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figures 1 and 2 depict the coordinate frame for the UR5e and WAM robot arm assignments, respectively, based on the DH convention. For each robot, the head pan and tilt joints are excluded, as their motions are independent of the primary manipulation tasks considered here.

Let \(\,^{i}\mathcal {T}_{j}\) denote the homogeneous transformation matrix from frame \(F_{i}\) to frame \(F_{j}\). The transformation from the base frame to the end-effector frame, \(\,^{0}\mathcal {T}_{E}\), is obtained by recursively multiplying the transformations between consecutive frames:

where \(\,^{0}R_{E} \in \mathbb {R}^{3 \times 3}\) is the rotation matrix from the base to the end-effector frame, and \(\,^{0}p_{E} \in \mathbb {R}^{3}\) is the position vector of the end-effector expressed in the base frame. The integer n is the number of intermediate frames in the kinematic chain.

From the dynamics perspective, the motion of the manipulator relates joint torques/forces to joint positions, velocities, accelerations, and external wrenches applied to the end-effector. Common formulations include the Newton–Euler method, the Lagrangian method, and the Hamiltonian method3. In this paper, the Newton–Euler recursive algorithm is adopted with DH parameters to obtain the inverse dynamics model.

The general inverse dynamics equation for an N-DOF manipulator is:

where \(\mathbf{M}(\mathbf{q}) \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) is the generalized inertia matrix, \(\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{q},\dot{\mathbf{q}}) \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) is the Coriolis/centrifugal/friction matrix, \(\mathbf{G}(\mathbf{q}) \in \mathbb {R}^{n}\) is the gravitational torque vector, \(\mathbf{J}(\mathbf{q}) \in \mathbb {R}^{6 \times N}\) is the Jacobian matrix, \(\mathcal {F} \in \mathbb {R}^{N}\) is the external wrench (forces and moments) applied at the end-effector.

The geometric and inertial parameters of each link are obtained from the CAD models of the UR5e and WAM manipulators. The moments of inertia are evaluated at each link’s center of mass (CoM) and expressed in its local frame. The state variables \(\mathbf{q}\), \(\dot{\mathbf{q}}\), \(\ddot{\mathbf{q}}\), and \(\tau\) denote joint position, velocity, acceleration, and generalized torque/force, respectively.

A special case is the inverse statics model, obtained by setting

In this work, no external forces or torques are applied to the end-effector, implying

Neural networks: finite-dimensional function approximators

Let \(\mathcal {X}\subseteq \mathbb {R}^{d_x}\) and \(\mathcal {Y}\subseteq \mathbb {R}^{d_y}\) denote input and output spaces. A feedforward neural network (multilayer perceptron, MLP) of depth L realizes a parametric map

where \(x\in \mathcal {X}\), \(\theta :=\{W_\ell ,b_\ell \}_{\ell =1}^{L}\) are weights and biases, and \(\sigma (\cdot )\) is a componentwise nonlinearity (e.g., ReLU, tanh, GELU). Given training pairs \(\{(x_i,y_i)\}_{i=1}^N\), parameters are obtained by empirical risk minimization as

where \(\mathcal {L}(\cdot )\) denotes task-appropriate loss (e.g., \(\ell _2\), Huber) and \(\mathcal {R}\) denotes a regularizer (e.g., weight decay). Optimization is done by stochastic gradient methods with mini-batches.

For nonpolynomial \(\sigma\), MLPs are universal approximators on compact sets, i.e., for any continuous \(f:\mathcal {X}\rightarrow \mathcal {Y}\) and \(\varepsilon >0\) there exists \(\theta\) such that \(\sup _{x\in \mathcal {X}}\Vert f(x)-\hat{f}(x;\theta )\Vert \le \varepsilon\). Beyond expressivity, the network’s Lipschitz constant can be bounded by the product of spectral norms,

which is relevant for robustness and gradient stability. Normalization (batch/layer), residual connections, and spectral constraints are common mechanisms to stabilize training without altering the input–output semantics.

Residual networks can be written as an explicit Euler discretization as

linking deep networks to continuous-time models \(\dot{x}(t)=\phi (x(t);\theta )\). This view motivates the architectures in the next subsection, where dynamics–not just static mappings–are learned.

Liquid neural networks (LNNs)

A liquid neural network is a type of continuous-time recurrent model whose effective time constants adapt to the input, providing strong temporal modeling with few parameters. Let \(x(t)\in \mathbb {R}^{n}\) be the hidden state driven by an input \(I(t)\in \mathbb {R}^{m}\). An LNN cell evolves according to

where \(\tau \in \mathbb {R}^n_{>0}\) is a base time-constant vector, \(\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^n\) a bias vector, \(g(\cdot ;\theta )\) a small neural module, which is often affine and activation, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. The instantaneous time constant becomes

Therefore, “liquid” can be understood as faster or slower dynamics emerge automatically as the input changes.

A single fused explicit–implicit Euler step from t to \(t+\Delta t\) admits a closed form as

This update inherits the stability of an implicit step at the computational cost of an explicit step, which is advantageous for real-time deployment and for handling stiff trajectories. Training proceeds by unrolling this discretization and applying backpropagation through time.

Under standard monotonicity bounds on g, each unit’s state and liquid time constant are bounded on any finite horizon as

which mitigates exploding trajectories and supports stable operation under distribution shifts. In practice, LNNs achieve high data efficiency (few parameters, strong temporal inductive bias) and fast on-the-fly adaptation, making them well-suited to systems with nonstationary or partially observed dynamics.

Invertible liquid neural networks (ILNNs)

Invertible neural networks for inverse problems

Consider hidden parameters \(x\in \mathbb {R}^{D}\) (e.g., joint angles/velocities/torques) and observables \(y\in \mathbb {R}^{M}\) (e.g., end-effector pose or sensor traces). The forward map \(s:x\mapsto y\) is typically known or simulable, while the inverse \(y\mapsto x\) is often ambiguous. Invertible Neural Networks (INNs) resolve this by learning a bijection between parameters and a pair [y, z] where latent \(z\in \mathbb {R}^{K}\) captures the information about x that is lost in y:

Training is forward-supervised on y (i.e., \(f_y(x)\approx s(x)\)) and unsupervised on z to enforce \(p(z)=\mathcal {N}(0,I)\) (and asymptotically independence of y and z). The posterior over x for a fixed measurement \(y^\star\) is obtained by sampling z and inverting: \(x=g(y^\star ,z)\). With a tractable Jacobian, the conditional density is

Invertibility is realized with affine coupling blocks (RealNVP/NICE): split \(u=[u_1,u_2]\) and apply

which yields triangular Jacobians and efficient computation of the log‑determinant term in (14).

Bi-directional losses. A practical objective combines: (i) a supervised forward loss \(L_y\big (y, f_y(x)\big )\); (ii) a latent-marginal loss \(L_z\) that matches q(y, z) to p(y)p(z) (e.g., by Maximum Mean Discrepancy(MMD)); and optionally (iii) a backward marginal \(L_x\) that aligns samples g(y, z) with a prior p(x). In the asymptotic zero-loss limit, sampling \(x=g(y^\star ,z)\) recovers the true posterior \(p(x\mid y^\star )\).

Propoesed algorithm design

We integrate (1)–(2) into the invertible framework (3)–(5) to obtain an invertible, time-continuous model tailored to inverse kinematics/dynamics.

State and measurement. Let the robot state collect generalized coordinates and rates, \(x(t)=[q^\top ,\dot{q}^\top ,\tau ^\top ]^\top\), and define observations y(t) as task-space poses/velocities and any measured signals. The forward channel of ILNN uses an LNN block to propagate the continuous hidden state over \([t,t+\Delta t]\) via (2), followed by affine coupling to output [y(t), z(t)]. The inverse channel is the exact architectural inverse, which takes [y(t), z(t)] and reconstructs a distribution over consistent states x(t).

Dynamics-consistent coupling. Concretely, each reversible block contains: (i) an LNN cell that updates a subset of channels by (2); and (ii) an affine coupling that mixes channels as in (5). Because the affine coupling is exactly invertible and the LNN update (2) is a deterministic, differentiable map, the overall block remains bijective, and its Jacobian determinant factorizes into a product of triangular (coupling) terms and block-diagonal LNN terms–preserving tractability for (4). (Invertibility and Jacobian tractability of the coupling construction and the forward–inverse pairing follow directly from the INN framework.)

Training objective. Given a simulator s (DH+Newton–Euler or measured forward trajectories), we minimize

with \(z(t)\sim \mathcal {N}(0,I)\) and where the forward rollout of x uses (2). This preserves the forward physics while learning a faithful inverse posterior over x for each y, even in multi-modal IK/ID regimes. (As established for INNs, zero forward and latent losses guarantee that inverse sampling recovers the true conditional posterior.)

Sampling-based solvers. At test time, given a reference \(y^\star\) (e.g., a desired end-effector pose or measured motion), draw \(z\sim \mathcal {N}(0,I)\) and compute \(x=g(y^\star ,z)\). For IK, the marginal over q is obtained by projecting samples; for ID, the marginal over \(\tau\) is read from the corresponding components. The stability bounds of the liquid cells ensure well-behaved trajectories under streaming inputs and closed-loop deployment.

Remark (discretization and BPTT). The fused step (2) permits efficient unrolling with standard backpropagation through time; compared with adjoint methods, this trades memory for higher backward accuracy, which is favorable when the control loop demands precise gradients.

Based on the pseudocode descriptions in Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, the proposed method integrates the forward and inverse modeling capabilities of the Invertible Liquid Neural Network (ILNN) into a cohesive training and inference framework tailored for robotic inverse kinematics (IK) and inverse dynamics (ID) problems.

The forward–backward update procedure for ILNN training is shown in Algorithm 1. In this phase, the model parameters–comprising neuron-specific time constants, recurrent and feedforward connection weights, and bias terms–are iteratively optimized using batched robotic state–action–torque datasets. The algorithm leverages a fused ordinary differential equation (ODE) integration step to propagate the network state through continuous-time dynamics while preserving invertibility. This ensures that the learned mapping remains bijective between sensorimotor states and actuation commands, thereby enabling both forward prediction and backward inference. The parameter update loop couples standard gradient descent with task-specific regularization, ensuring numerical stability and smooth generalization across robot configurations.

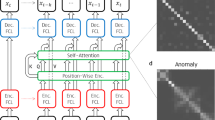

The computational workflow of the proposed Invertible Liquid Neural Network (ILNN) as shown in Fig. 3 for solving inverse kinematics (IK) and inverse dynamics (ID) problems in robotics. The diagram captures the bidirectional mapping capability inherent to the ILNN architecture, where the forward pass processes sensory and kinematic data through a set of liquid-state neurons governed by adaptive time constants, while the inverse mapping leverages the network’s invertibility to retrieve the corresponding joint configurations or dynamic parameters. The figure emphasizes the modular integration of the ILNN core with preprocessing units (e.g., sensor fusion, normalization) and post-processing blocks (e.g., torque/pose refinement), highlighting the network’s ability to handle non-linear, time-varying system dynamics with minimal model drift. This design ensures that both forward and inverse tasks share the same learned representation, enhancing data efficiency and improving generalization across tasks.

Algorithm 2 extends this framework to the inverse modeling context, where the trained ILNN is used to infer actuation commands (torques or joint velocities) from desired state transitions. The algorithm exploits the invertibility of the learned dynamics to perform direct backward integration in latent space, avoiding ill-posed matrix inversions commonly encountered in conventional IK/ID solvers. Through repeated refinement of the predicted control inputs using feedback from both simulation and real-world measurements, the method achieves high-precision motion generation even under unmodeled disturbances. Together, these algorithms form a unified architecture where a single invertible model can serve both as a high-fidelity forward simulator and as a robust inverse solver, significantly improving efficiency and accuracy compared to existing approaches.

The stepwise operational flow of the ILNN within the proposed control framework as shown in Fig. 4, from input acquisition to output generation. The process begins with real-time state measurements and desired trajectory references, which are passed through the ILNN encoder to extract latent state representations governed by the liquid neural dynamics. The decoder branch, utilizing the invertible mapping, reconstructs either joint torques (for inverse dynamics) or joint positions/velocities (for inverse kinematics), depending on the control objective. Feedback loops in the figure indicate the adaptive update mechanism, where the learned time constants and synaptic weights are iteratively refined based on tracking error or performance indices. The figure also denotes the integration of physical priors–such as rigid-body dynamics equations–into the learning process, ensuring that the model respects fundamental mechanical constraints while maintaining adaptability to unmodeled disturbances.

Raw joint and task-space trajectories are standardized and resampled at step \(\Delta t\) to form a preprocessed temporal feature sequence (left). The sequence is integrated by a liquid layer composed of LNN cells, each updated by the fused explicit–implicit Euler step, yielding a time-varying hidden state h(t) and context c(t). A readout maps h(t) to task-space observables y(t) (right).

Progressive optimization pipeline for liquid neural network (LNN) design. Starting from an initial randomly generated architecture, the process proceeds through (Step 1) architecture search to identify promising network topologies, (Step 2) neuron number variation to refine the computational capacity of selected layers, and (Step 3) parameter search to fine-tune synaptic weights and biases. This staged approach enables systematic exploration of the design space for enhanced performance in spatiotemporal modeling tasks.

Experimental results

Experiment setup

All experiments were executed on a workstation-class Linux machine with an Intel Core i9-13900K CPU and double RTX 4090 GPUs for training and batched evaluation. The control and monitoring environment was implemented in ROS2 Foxy (Github resource: Link) and interfaced with the MuJoCo physics engine (MuJoCo 3.1.4, developed by Google DeepMind: Link) for high-fidelity simulation of rigid-body dynamics and contact events. The ROS-MuJoCo integration is used for closed-loop rollouts, latency measurements, and online logging of state/action traces as shown in Fig. 5. Later, we transfer all of our simulations on MuJoCo to a real robot to test the feasibility of our method. The analytical forward models required by the physics-consistency objective employ standard DH-based kinematics and Newton–Euler inverse dynamics, as specified in section “Preliminaries” in (2) and the DH parameter tables in Table 1 and Table 2. ILNN training and evaluation follow the fused explicit–implicit Euler step and bi-directional loss design presented in section “Invertible liquid neural networks (ILNNs)” and the corresponding pseudocode blocks.

For robotic platforms and simulation, we consider two canonical manipulators in simulation: a 6-DoF UR5e and a 7-DoF Barrett WAM, using their DH assignments and link inertial properties. For each platform, we organize the data into six distinct scenario groups, Da1-Da6, which we then partition into four development splits, Dev0–Dev3, for cross-validation. These scenarios were designed to be comprehensive, comprising rich motion corpora that span three primary categories of common manipulation tasks: reach-to-grasp maneuvers, pick-and-place operations, and large-amplitude joint sweeps. To ensure distributional diversity in both task and joint spaces, all motions were generated with randomized payloads and joint-space waypoints. All signals are resampled to a uniform fixed-rate grid consistent with the ILNN fused step \(\Delta t\), and we normalize joint angles/velocities/torques and end-effector twists with per-dimension affine scalings estimated on the training split. During training, MuJoCo provides reference task-space trajectories to compute the physics consistency loss \(L_y\) in (16), while the ILNN’s invertible channel supplies samples for the latent-matching \(L_z\) and optional backward-marginal \(L_x\) terms. To ensure distributional diversity in both task and joint spaces, all motions were generated with randomized payloads, ranging from 0 kg to 2 kg, and joint-space waypoints.

Datasets, splits, and baselines. We organize data into six scenario groups, Da1–Da6, each partitioned into four development splits, Dev0–Dev3, which we rotate for cross-validation. For inverse kinematics (IK) we supervise on (x, q) pairs; for inverse dynamics (ID) we supervise on \((x,\tau )\), with x collecting task-space poses/velocities and measured signals. We compare ILNN to representative learning baselines—VAE, Neural ODE, and GANs—implemented with matched capacities and trained on the same splits and preprocessing pipeline to ensure fairness. Quantitative comparisons are reported per row/split in Tables 3 and 4.

For the Training protocol and hyperparameters, ILNN rollouts unroll the fused liquid step (Algorithm 1) over horizons T aligned with the simulator’s control period, and are optimized end-to-end with mini-batch stochastic gradient methods. The affine-coupling backbone follows Algorithm 2; latent samples \(z\sim \mathcal {N}(0,I)\) are drawn per time-step to form inverse samples via the exact architectural inverse. We tune the trade-off weights \(\lambda _z,\lambda _x\) in (16) on Dev-splits to balance forward physics fidelity, latent factorization, and inverse posterior quality. Early stopping uses validation NLL and coverage calibration. Model selection is finalized on the cross-validated averages reported in section “Results analysis”. All methods are evaluated with identical batching, mixed-precision settings, and dataloader thread counts; latency is measured as per-step wall-clock inference time of a single forward pass at the control rate within the ROS2–MuJoCo loop as shown in Fig. 5.

The evaluation metrics is consistent with Fig. 6, we report (i) joint-angle RMSE \([\textrm{rad}]\), (ii) end-effector position error \([\textrm{m}]\), (iii) per-step inference latency \([\textrm{ms}]\), (iv) negative log-likelihood (NLL) \([\text {nats}]\) on observed task-space measurements, and (v) empirical coverage of a nominal \(\alpha\)-level credible interval \([\text {probability}]\). Unless otherwise noted, lower is better for (i)–(iv), and coverage closer to \(\alpha\) is better.

Results analysis

We first highlight the role of the ROS2–MuJoCo stack and its hardware counterpart, as shown in Fig. 5. ROS2 orchestrates the control loop and logging, while MuJoCo provides the rigid-body and contact dynamics used both for closed-loop rollouts and for the forward-physics term in our loss. Using the same pipeline for all methods ensures identical I/O timing, identical numerics in the forward model, and consistent wall-clock latency measurement. This uniform infrastructure eliminates confounds between algorithmic performance and tooling, so differences observed later can be attributed to the learning method rather than the evaluation harness.

Figure 6 compares the distributions of five test metrics across the four methods. Reading column-wise, ILNN’s curves (second row) are consistently the sharpest and most favorably located relative to the dotted target lines. In (a) joint-angle RMSE [rad] and (b) end-effector position error [m], ILNN concentrates near the low-error region with a narrow spread, whereas GANs show broader, sometimes multi-modal shapes and Neural-ODE shifts rightward with heavier tails–evidence of larger and less stable errors under stiff or fast motions; VAE is more compact than GANs/Neural-ODE but remains right-shifted relative to ILNN. In (c) per-step latency [ms], ILNN forms a unimodal distribution well below (or tightly around) the reference line, while Neural-ODE skews to higher latency and GANs/VAE exhibit wider dispersion, indicating more variable compute cost under identical I/O and physics. In (d) NLL [nats], ILNN is clearly left-shifted (lower is better), reflecting better likelihood fit and calibration of the predictive distribution. Finally, in (e) empirical coverage [probability], ILNN aligns closely with the nominal \(\alpha\) level (dotted line), whereas GANs and VAE tend to over- or under-cover and Neural-ODE shows larger variance; this indicates that ILNN’s uncertainty quantification is both accurate (near the target) and precise (tight spread). Taken together, the figure shows that ILNN achieves superior accuracy, tighter runtime behavior, and better-calibrated uncertainty than the alternatives, not only on averages but across the entire error/latency distributions.

Across all scenario groups (Da1–Da6) and development splits (Dev0–Dev3), the ILNN attains the lowest error in every row for IK, as shown in Tables 3 and 4. Two aspects are noteworthy. First, the advantage holds for both “easier” and “harder” splits–i.e., for short and long trajectories, and across diverse workspace regions–indicating that the gains are not confined to a particular motion family. Second, ILNN’s values vary smoothly across Dev0\(\rightarrow\)Dev3 within each Da-group, producing a narrower spread than the baselines. This reduced variance is consistent with the liquid cell’s fused integration step, which stabilizes state updates under fast pose changes, and with the invertible coupling, which constrains the learned mapping to remain bijective. By contrast, VAE and GANs occasionally show local minima on individual rows but lack uniform dominance over all splits, and Neural-ODE exhibits larger fluctuations when the trajectory contains stiff segments, reflecting sensitivity to the solver and step size. Collectively, the IK results in Tables 3 and 4 indicate that enforcing invertibility and input-adaptive time constants improves both accuracy and split robustness.

Distributional comparison of test-set metrics for inverse kinematics and dynamics across all evaluated methods. The figure illustrates model performance in terms of accuracy, computational cost, and uncertainty calibration. (a) Joint-angle Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) in radians. (b) End-effector position error in meters. (c) Per-step inference latency in milliseconds. (d) Negative log-likelihood of task-space measurements in nats. (e) Empirical coverage probability. For each plot, the colored curves represent the kernel density estimates for a specific model. The shaded background shows the empirical reference distribution across the entire test dataset, providing a baseline for comparison. The dotted vertical lines indicate a target value; for latency (c), this line represents a critical real-time performance threshold required by the control loop. The concentrated and favorably centered distributions for our ILNN model demonstrate its superior accuracy, computational efficiency, and better-calibrated uncertainty quantification compared to the baseline approaches.

The same pattern appears for ID that ILNN yields the best score in every row on both tables, as shown in Tables 3 and 4. Compared to the baselines, ILNN shows consistently lower mean errors and markedly smaller row-to-row drift, especially in scenario groups with pronounced accelerations and payload changes. This behavior aligns with the design of the objective: the forward term anchors predictions to the Newton–Euler model, while the latent regularization discourages spurious modes in the inverse map. In contrast, Neural-ODE tends to over-smooth high-frequency torque transients, and VAE/GAN variants occasionally under- or over-estimate joint couplings when the training data are scarce. The absence of regressions for ILNN across any Da/Dev combination suggests that the model generalizes across motion regimes without ad-hoc retuning.

The hardware experiments were conducted on the UR5e and WAM manipulators. The control and monitoring system for the experiments was built using ROS2 Foxy and interfaced with the MuJoCo physics engine. Data acquisition on the robotic platforms was handled by the experimental team. For each robot arm, two different trajectories were set to test the models’ ability to follow spatial paths and generate corresponding joint velocities. The models (ILNN and baselines) were evaluated by measuring their end-effector position tracking along the Cartesian axes (x, y, and z) and the generated joint velocity profiles over time. This real-world testing validates the feasibility and performance of the ILNN-based approach for real robot control.

Figure 7 shows the UR5e end-effector tracking on real hardware along the three Cartesian axes (x, y, z) for two different trajectories (a) and (b). In both cases, the ILNN model consistently achieves the closest tracking to the Reference trajectory across all three axes, particularly after the initial transient period. The baselines (VAE, Neural ODE, GANs) show noticeable deviations, especially in the x-axis and z-axis responses, and exhibit more oscillatory behavior at the start compared to ILNN. The ILNN’s superior tracking demonstrates its effectiveness in providing high-precision motion control for the UR5e manipulator in a real-world setting.

Figure 8 further details the UR5e’s performance in spatial path following and the generated joint velocity profiles. The top row (A-D) shows the 3D end-effector path, where the ILNN’s output (D) closely aligns with the Reference trajectory for both the “ plum blossom” shape (a) and the “infinity” shape (b), demonstrating high-fidelity path following. By contrast, VAE (A) shows the largest deviation, and GANS (C) and SNA-GANs (B) also exhibit visible tracking errors. The bottom row (E-H) compares the joint velocities. The ILNN (H) produces the smoothest and most stable joint velocity profiles, suggesting that its inverse dynamics model is more robust and less prone to generating jittery or high-frequency torque commands compared to the baselines.

Figure 9 presents the WAM robot arm end-effector tracking on real hardware. Similar to the UR5e results, the ILNN model consistently tracks the Reference trajectory with the highest fidelity for both test motions (a) and (b). Across the x, y, and z axes, the ILNN’s response is the best match to the reference signal, especially in the more complex time-varying segments. The baselines show larger and more sustained tracking errors, particularly for the second trajectory (b), which appears to be more dynamic and challenging. The results affirm ILNN’s robust performance even on the higher-DoF (7-DoF) WAM platform.

Figure 10 illustrates the WAM spatial path following and its joint velocity profiles. The spatial path tracking (A-D) shows ILNN (D) maintaining the closest fit to the Reference path for both test cases, significantly outperforming VAE (A), GANS (C), and SNA-GANs (B), which exhibit notable deviations. The WAM’s higher dimensionality makes the IK/ID problem more complex, yet the ILNN’s performance remains strong. In the joint velocity profiles (E-H), the ILNN (H) exhibits stable and well-behaved responses, with faster and smoother transitions compared to the noticeable oscillations and overshoots observed in the baseline methods, particularly VAE (E) and SNA-GANs (F). The tight and well-behaved joint velocities from the ILNN indicate its effective, real-time solution of the inverse dynamics problem.

UR5e’s EE tracking on hardware along the three Cartesian axes using ILNN compared with three baseline methods. (a) shows the time histories of position along the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis for the first test trajectory with reference and the three learning baselines compared to ILNN. (b) shows the same set of curves for the second test trajectory with the same legend and layout.

UR5e spatial path following and joint velocity profiles on hardware. (a) shows in the top row the EE path in three dimensions for the plum blossoms shape under three baseline methods compared with ILNN under the reference path, and in the bottom row, the corresponding joint velocity profiles over time. (b) shows the same presentation for the “infinity” shape with spatial paths in the top row and joint velocity profiles in the bottom row.

WAM end effector tracking on hardware along the three Cartesian axes. (a) shows the time histories of position along the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis for the first test trajectory with reference and the three learning baselines compared to ILNN. (b) shows the same set of curves for the second test trajectory with the same legend and layout.

WAM spatial path following and joint velocity profiles on hardware. (a) shows in the top row the end effector path in three dimensions for the first test trajectory under three baselines and ILNN, together with the reference path, and in the bottom row the corresponding joint velocity profiles over time. (b) shows the same presentation for the second test trajectory with spatial paths in the top row and joint velocity profiles in the bottom row.

Conclusion

We presented an Invertible Liquid Neural Network (ILNN) for learning inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics from limited, real-world–style data. The approach fuses liquid time-constant cells–updated via a stable, closed-form, fused Euler step–with invertible affine coupling, yielding a single model that is simultaneously a reliable forward predictor and a tractable inverse solver. The ROS–MuJoCo evaluation in both simulation and hardware experiments pipeline ensured identical runtime and physics assumptions across methods. On two manipulator platforms and multiple scenario/split combinations, ILNN achieved the best score in every row for both IK and ID, while exhibiting reduced variance across splits–evidence that the inductive biases of liquid dynamics and invertibility materially improve accuracy and robustness.

Future work will extend ILNN to (i) richer contact/friction models and hybrid events, and (ii) multi-task and multi-robot training that shares invertible blocks while preserving per-robot calibration. We also plan to study uncertainty quantification within the invertible latent channel to provide calibrated posteriors for safety-critical control.

Data availability

Most of the raw data has been shown in our manuscript. Some data that support the findings of this study are available from a third-party business research laboratory. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and the datasets are not publicly available due to security and export-control requirements. However, data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of the sponsoring agency and the Business Export Controls office. Any access will require a data-use agreement and may be limited to de-identified subsets.

References

Mystkowski, A., Wolniakowski, A., Kadri, N., Sewiolo, M. & Scalera, L. Neural network learning algorithms for high-precision position control and drift attenuation in robotic manipulators. Appl. Sci. 13, 10854 (2023).

Siciliano, B., Sciavicco, L., Villani, L. & Oriolo, G. Robotics: Modelling, Planning and Control (Springer, New York, 2010).

Featherstone, R. Rigid Body Dynamics Algorithms (Springer, New York, 2008).

Spong, M. W., Hutchinson, S. & Vidyasagar, M. Robot Modeling and Control (Wiley, Hoboken, 2006).

Clochiatti, E., Scalera, L., Boscariol, P. & Gasparetto, A. Electro-mechanical modeling and identification of the ur5 e-series robot. Robotica 42, 2430–2452 (2024).

Deisenroth, M. P. & Rasmussen, C. E. PILCO: A model-based and data-efficient approach to policy search. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) (2011).

Karlik, B. & Aydin, A. V. Performance analysis of various activation functions in generalized MLP architectures of neural networks. Int J Artif Intell Expert Syst 1, 111–122 (2011).

Miller, W. T. & Allen, R. R. Neural networks for computing kinematic properties of robot manipulators. Biol. Cybern. 59, 331–338 (1988).

Fragkiadaki, K., Levine, S., Felsen, P. & Malik, J. Recurrent network models for human dynamics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2015).

Chen, R. T., Rubanova, Y., Bettencourt, J. & Duvenaud, D. Neural ordinary differential equations. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2018).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2017).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Levine, S., Finn, C., Darrell, T. & Abbeel, P. End-to-end training of deep visuomotor policies. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–40 (2016).

Kalashnikov, D., Irpan, A., Pastor, P. et al. QT-Opt: Scalable deep reinforcement learning for vision-based robotic manipulation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL) (2018).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Degrave, J., Hermans, M. & Dambre, J. A differentiable physics engine for deep learning in robotics. Front. Neurorobotics 13, 6 (2019).

Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2014).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 (2013).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2020).

Fuchs, F., Worrall, D., Fischer, V. & Welling, M. Se(3)-transformers: 3d roto-translation equivariant attention networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) (2020).

Thomas, N., Smidt, T., Kearnes, S. et al. Tensor field networks: Rotation- and translation-equivariant neural networks for 3d point clouds. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.08219 (2018).

Hasani, R., Lechner, M., Amini, A., Rus, D. & Grosu, R. Liquid time-constant networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2021).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ye Zhang, Qi Chen and Longsen Gao are the first authors and have same contributions for this work; Rui Liu, Linyue Chu and Kangtong Mo are the second authors and have same contributions; Zhengjiang Kang, Wenyou Huang and Xingyu Zhang are the third authors and have the same contributions. Ye Zhang conceived the study and supervised the research. Ye Zhang, Qi Chen, and Longsen Gao designed the ILNN methodology, developed the learning objectives and algorithms, and defined the evaluation protocol. Rui Liu, Linyue Chu, and Kangtong Mo implemented the ROS2-MuJoCo software stack and conducted simulation experiments and baseline comparisons. Zhengjian Kang, Wenyou Huang, and Xingyu Zhang performed hardware validation and data acquisition on robotic platforms and contributed to experiment design and troubleshooting. Longsen Gao and Rui Liu curated datasets and prepared parameter tables; Qi Chen, Linyue Chu, and Kangtong Mo carried out formal analysis and visualization. Ye Zhang and Qi Chen wrote the initial manuscript draft, and Longsen Gao, Rui Liu, Linyue Chu, Kangtong Mo, Zhengjian Kang, Wenyou Huang, and Xingyu Zhang provided critical revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Chen, Q., Gao, L. et al. Invertible liquid neural network-based learning of inverse kinematics and dynamics for robotic manipulators. Sci Rep 15, 42311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26422-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26422-1