Abstract

The transition from elementary to junior high school presents developmental challenges, particularly for students with neurodevelopmental traits. This study examined how autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) traits and effortful control (EC) were related to changes in mental health during this transition in a large Japanese community sample (N = 2,564). This longitudinal study used data from a community-based cohort of Japanese students and their parents/guardians (N = 2,692). Autism traits were measured using the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ). ADHD traits were assessed with the Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale (ADHD-RS). Effortful control (EC) was evaluated using the “Effortful Control” subscale of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire–Revised (EATQ-R). Mental health problems were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) before and after the transition. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) and latent profile analysis (LPA) were conducted to examine associations among autism and ADHD traits, EC, and mental health across the transition. GEE revealed that higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC predicted more severe mental health problems. The LPA identified three distinct subgroups characterized by high, moderate, and low SDQ scores across the transition. The high-SDQ group showed elevated autism and ADHD traits and low EC, whereas the low-SDQ group showed low auism and ADHD traits and high EC. The moderate group exhibited intermediate levels for all measures. These findings suggest that pre-existing mental health problems tend to persist during the transition period. Importantly, students with higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC exhibited diverse adaptation patterns—some improved while others worsened—highlighting that high autism traits are not necessarily associated with post-transition mental health deterioration. This underscores the need for support tailored to neurodevelopmental and self-regulatory profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition from elementary to junior high school is a major turning point for children. During this transition, students must adjust to important changes in school structure, teacher expectations, and social relationships1,2,3. Junior high schools differ from elementary schools in terms of their learning environment, including campus size, number of students, moving to different classrooms for classes, curriculum, and multiple subject specialists4. Therefore, a higher developmental level is required from junior high school students not only in self-management of academic and behavioral but also emotional aspects compared to elementary school students4,5. Whereas younger children rely heavily on caregivers and teachers for emotional regulation, adolescence is characterized by a developmental shift toward greater self-regulation and peer-based support6. Given the heightened emotional reactivity and increased vulnerability to mental health problems during this period, emotional self-regulation becomes particularly critical in early adolescence6,7. Studies have reported that unsuccessful school transitions can be associated with more mental health problems8, lower well-being9, and prolonged absenteeism and dropout10.

This transition also requires students to move between multiple classrooms throughout the day, adapt to multiple teachers, and interact with many new peers11 and coincides with important developmental changes and increased stress levels12. In adolescence, as relationships shift from an adult-centered to a peer-centered orientation13, students spend more time with their peers, develop more complex friendships, seek a sense of belonging to a peer group where they feel valued, and become more sensitive to acceptance and rejection by their peers14,15. Simultaneously, as students spend less time with specific teachers in junior high school, there is less support for students in junior high school than in elementary school5. Therefore, whereas teacher support decreases during this transition period, social support and relationships with peers and teachers affect student transitions16,17. Given these points, the transition period requires enhanced adaptive skills and self-regulation abilities, particularly because students must manage their social interactions and academic responsibilities independently with less direct adult supervision18.

In this context of environmental changes during the transition to middle school, individual differences in effortful control (EC) emerge as a critical factor that largely determines whether students can successfully adapt to these new demands. These abilities are involved in coordinating behavioral, emotional, and cognitive processes in complex middle school environments. EC has been identified as a key predictor of adaptation to changes that occur during this school transition period19. EC is the ability to voluntarily inhibit a dominant response (inhibitory control), activate a subdominant response (activation control), detect errors, or engage in planning, and to focus and shift attention when needed (attentional control)20. While EC is sometimes described as a subcomponent of self-regulation, it is widely regarded as a central construct reflecting individual differences in self-regulatory capacity, particularly in children and adolescents21. Inhibitory control and self-regulation are crucial components of EC that help students manage their behavior, attention, and emotions during the school transition period18,21. These abilities are especially important, as students face novel academic and social demands in their new school environment. For example, attentional control supports the ability to focus in multiple classes and shift between tasks; inhibitory control is crucial in peer interactions where emotion regulation is needed; activation control allows students to initiate tasks even in the absence of motivation or in the presence of social anxiety. Thus, adequate EC allows students to sustain their attention, complete tasks, and follow rules and instructions, all of which directly affect their learning22. Longitudinal studies on the transition from elementary to junior high school have found that students with higher levels of self-control tend to maintain higher adjustment and academic achievement after school transition23,24.

Self-regulation and social interaction deficits are known to manifest in neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD)25,26. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts and the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities27 and is associated with difficulties in EC28. Research has shown that specific components of the EC, inhibitory control, and attention control display distinct patterns in autistic individuals. Although autistic individuals often demonstrate relative strength in basic attention regulation, they frequently experience challenges with inhibitory control, particularly in social contexts where they need to suppress inappropriate responses or adapt their behavior to changing social demands29,30. Similarly, self-regulation deficits are a core feature of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)31. ADHD is a behavioral disorder characterized by attentional dysfunction, hyperactive/impulsive behavior, or both27. In contrast to ASD, ADHD is characterized by difficulties in working memory and most other metacognitive executive functions, including initiation, planning, organization, self-monitoring, and inhibition25. Although ADHD symptoms generally decline with development, they may stagnate or worsen during the transition to middle school due to environmental changes such as multiple teachers, classroom transitions, and increased demands for autonomy32. Moreover, ADHD traits have been associated with poorer academic achievement and increased use of maladaptive strategies after school transition33. A longitudinal study further identified inattention in students with ADHD as a risk factor for academic impairment during middle school34,35. Importantly, autism and ADHD traits frequently co-occur, with approximately 50–70% of autistic individuals also meeting criteria for ADHD36,37. This co-occurrence is also evident at the trait level in general population samples38. Co-occurring autism and ADHD traits have been associated with more severe school functioning difficulties compared to autism alone39. Given this point, including both autism and ADHD traits in analyses may provide more insightful understanding of how autism traits relate to mental health problems during the school transition period. It is currently considered that autism and ADHD traits are continuously distributed in the general population40,41.

However, little is known about how these factors relate to mental health during the school transition in mainstream educational settings. Several studies42,43 have examined the association between autism traits and transitions in the general population. Typically, these studies have shown that high autism traits are associated with poor outcomes during the transition period (e.g., Quality of Life: QoL). Nevertheless, Whelan et al.42found that students with higher autism traits showed improved QoL and mental health after the transition. Previous studies42,43 have been limited by small sample sizes (N = 51) in the general population and could not conduct robust subgroup analyses or examine the complex interactions between neurodevelopmental traits and transition outcomes.

Furthermore, previous studies on autism traits and school transition in clinical samples have yielded inconsistent results44,45,46, highlighting the importance of considering the possible heterogeneity of autism traits. To accurately understand the association between autism traits and school transition, it is essential to identify homogeneous subgroups based on autism and ADHD traits, EC, and mental health problems and to examine how these characteristics change during the transition period within each identified subgroup. This approach can potentially elucidate associations between particular characteristics and transition experiences, thereby enabling more targeted and effective interventions.

This study addressed these methodological limitations using a large-scale community-based design, enabling a more precise estimation of the effects and identification of homogeneous subgroups based on NDD traits. Therefore, this study primarily aimed to clarify how autism, ADHD traits, and EC are related to mental health problems during the transition using a large-scale community-based study design. Additionally, we aimed to identify distinct subgroups based on the patterns of NDD traits, EC levels, and mental health problems during the transition. This community-based study, with a diverse sample, enabled a more robust estimation of NDD traits and mental health problems. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that autism and ADHD traits would be negatively associated with mental health and EC would be positively associated with mental health (i.e., higher autism and ADHD traits would be related to more severe mental health problems and higher EC would be related to less mental health problems). We further hypothesized that the association between autism and ADHD traits and EC and mental health problems during the transition period would vary across the identified subgroups. Specifically, we predicted that more vulnerable groups—those with higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC—would face an increased risk of mental health problems during the transitional period. Clarifying these associations can be useful in understanding school refusal and mental health problems among adolescents.

Methods

Study setting and participants

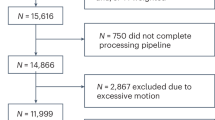

Data for this study were obtained from the Assessment from Preschool to Puberty—Longitudinal Epidemiological (APPLE) study, a community-based cohort study investigating risk and protective factors for mental health in children and adolescents in Japan47. The APPLE study is a population-based prospective cohort conducted in Hirosaki, Japan, that tracks developmental and mental health outcomes from age 5 to 12. The study comprises three phases: a 5-year-old developmental check-up, annual school-based surveys from grades 1 to 6, and an adolescent survey at grade 7. APPLE study was conducted in public elementary and junior high schools in Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture, Tohoku region (northern part of Japan’s main island). Hirosaki City has 52 public elementary and junior high schools (35 elementary and 17 junior high schools), including the only elementary and junior high schools affiliated with Hirosaki University. There is only one private junior high school in the city. This study included all 52 public schools, all of which participating schools followed the standard Japanese public education system, characterized by a clear transition from elementary (grades 1–6) to junior high school (grades 7–9). Private schools, international schools, and integrated schools—with potentially different or no transition structures at grade 7—were excluded from this study. For details regarding the study design and data collection procedures, please refer to Hirota et al.47. In the present analysis, we used two cohorts from the APPLE study: Cohort 1, comprising students who were in 6th grade (last year of elementary school) in 2017, and Cohort 2, consisting of students who were in 6th grade in 2018. Both cohorts were followed through their transition to 7th grade (the first year of junior high school). A total of 2,692 students and their parents/guardians were enrolled in this study.

In Japan, junior high schools differ significantly from elementary schools. For example, elementary schools use a class-teacher system, whereas junior high schools adopt a subject-teacher system. Additionally, junior high schools impose more rules on students, and student guidance tends to be more rule-based and stricter than in elementary schools48.

Measurements

Autism traits

Autism traits were measured prospectively in 2016 using the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)49. The ASSQ was administered when participants were in 5th grade (Cohort 1) or 4th grade (Cohort 2), and completed by the parents/guardians of participating students. The ASSQ is a screening tool used to identify ASD in school-aged children and consists of 27 items rated on a 3-point scale. Of the 27 items, 11 pertain to social interactions, 6 to communication problems, and 5 to restricted and repetitive behavior. The remaining items pertain to motor clumsiness and its associated symptoms. The psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the ASSQ have been validated in a general population sample50. The total score ranges from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating higher ASD traits. The internal consistency of the ASSQ in the present study was good (α = 0.89).

ADHD traits

The ADHD traits were measured prospectively in 2016 using the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder rating scale (ADHD-RS)51. The ADHD-RS was also collected when participants were in 5th grade (Cohort 1) or 4th grade (Cohort 2), and completed by parents/guardians of participating students. The ADHD-RS consists of 18 items rated on a 4-point scale. Of these, 9 assess inattention and 9 hyperactivity-impulsivity. The Japanese version of the ADHD-RS has been validated in a general population sample52. The total score ranges from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating higher ADHD traits. The ADHD-RS total score demonstrated in the present study excellent reliability (α = 0.92).

Effortful control (EC)

In this study, EC was measured in the 6th grade using the “effortful control” subscale of the Japanese version of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised Self-Report Form (EATQ-R)53, with responses provided by students’ parents or guardians. The EC subscale consists of 26 items scored on a 5-point scale (1 = almost always untrue of you; 5 = almost always true of you). The psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the EATQ-R were validated using a general population sample54. The total score ranges from 26 to 130, with higher scores indicating the presence of a given temperamental characteristic. The “Effortful Control” subscale of EATQ-R demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91).

Mental health problems

Mental health problems were measured in 6th grade elementary school and 1st grade junior high school using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)55, which was completed by students’ parents or guardians. The SDQ comprises 25 items measuring hyperactivity/inattention, conduct problems, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behavior among 3- to 16-year-olds. The Japanese version of the SDQ has good reliability and validity56. In this study, we used the Total Difficulties Score (TDS) of the SDQ (range: 0–40), which is calculated as the sum of the four difficulty subscales: conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, emotional symptoms, and peer problems. Higher scores indicate more serious problems. The TDS provides a broad indicator of mental health by combining internalizing and externalizing difficulties during the school transition. Prior research suggests that such co-occurring difficulties often remain stable over time and may serve as early indicators of later adjustment problems57,58. Furthermore, the TDS has been widely used in studies of school transition and interventions targeting autistic students45,59. The TDS of SDQ for showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.80 in both 6th and 7th grade).

Statistical analyses

Multiple imputation was performed before generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis. Of the total sample, 59% (n = 1,589) had no missing data. The pattern of missingness was assumed to be missing at random. Participants with more than 70% missing data (n = 128) were excluded from the analyses to minimize potential bias and estimation errors. The final analytical sample for the GEE consisted of 2,564 students, with data collected at both pre- and post-transition time points. This represents an exceptional 95% retention rate of the total sample, ensuring robust longitudinal data and minimizing potential selection bias. Ten imputed datasets were generated using mice package 3.13.060. Following Rubin’s rule61, a GEE was performed on each imputed dataset, and the results were pooled to calculate the final estimates. The GEE is particularly valuable for analyzing panel data, especially repeated measures or time-series data, as it accounts for within-subject correlations and provides robust population-averaged estimates62. In this study, we employed a GEE to examine factors associated with changes in mental health problems during this transition. Before applying GEE, continuous predictor variables (ASSQ, ADHD-RS, and EC scores) were standardized within each imputed dataset. In the GEE model, the SDQ score was used as the dependent variable, and time, sex (coded as 1 = male, 2 = female), and standardized ASSQ, EC, and ADHD-RS scores were included as independent variables.

Although GEE is useful for identifying population-level factors associated with mental health problems during the transition period, it does not account for individual differences in developmental trajectories over time. To address this limitation, we employed a latent profile analysis (LPA), a robust mixture-model technique commonly used to identify homogeneous latent subgroups within a heterogeneous population63,64. This approach enabled us to identify subgroups characterized by different patterns of mental health problems across the transition period and to examine the characteristics associated with each profile. In general, growth mixture modeling (GMM) or latent class growth analysis (LCGA) are more suitable for identifying latent subgroups in longitudinal data. However, because this study included only two measurement time points, applying GMM or LCGA is likely to result in overfitting and/or convergence problems. Therefore, an LPA was conducted to examine the patterns of autism and ADHD traits, EC levels, and mental health problems. The LPA included ASSQ, ADHD-RS, EC, and SDQ scores in the 6th and 7th grades to examine how combinations of ASD traits, ADHD traits, and effortful control co-occur with different mental health patterns. Including all these variables allowed us to identify complex profiles (e.g., improved SDQ scores alongside high autism traits and low ADHD traits). We tested models with one to six profiles using the tidyLPA package in R65. Model selection was guided by multiple fit indices, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and entropy. The number of profiles were selected based on minimizing AIC, BIC, and LogLikelihood and maximizing entropy. These indices were obtained from each imputed dataset, and the average scores across the imputed data were used to evaluate each model. Class labels across the imputations were aligned using the Hungarian algorithm to ensure consistency in class interpretation. For LPA, missing data were handled using the missForest package66 because there is currently no standardized method for pooling LPA results across multiple imputed datasets.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate whether neurodevelopmental traits and mental health problem characteristics discriminated between classes; the chi-square test of independence was applied to test categorical differences in sex distribution across profiles. All analyses were performed using R 4.1.067.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Committee of Medical Ethics of the Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine (IRB# 2015–055). Before data collection, parents/guardians received written information about the study from the schools, with instructions to contact the researchers if they wished to decline participation. We excluded children whose primary caregivers indicated that they did not want their children to participate. The student questionnaire was administered in class in accordance with a teacher manual. Before distributing the questionnaires, the classroom teachers informed the students about the study content, including that participation was voluntary and that students had the right to decline participation in part or all of the questionnaires without any disadvantage. Students were given the opportunity to ask questions, and those who chose not to participate were allowed to engage in self-study during the session. Moreover, both students and their parents/guardians retained the right to withdraw consent at any time, even after initially agreeing to participate. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics and demographic data for all variables are presented in Table 1. In general, the sample was equally distributed across sexes (49.37% male in Cohort 1 and 50.04% in Cohort 2). The mean ASSQ score was 4.26 (SD = 5.48) in Cohort 1 and 4.46 (SD = 5.60) in Cohort 2. For ADHD-RS, the mean scores were 5.64 (SD = 6.55) in Cohort 1 and 6.52 (SD = 7.05) in Cohort 2. EC scores averaged 62.65 (SD = 11.66) in Cohort 1 and 62.82 (SD = 11.55) in Cohort 2. In 6th grade, the mean SDQ total score was 7.34 (SD = 4.92) in Cohort 1 and 7.30 (SD = 4.66) in Cohort 2, while in 7th grade, it was 7.26 (SD = 4.78) and 6.87 (SD = 4.51), respectively. Moreover, the sample characteristics were comparable between the overall and analyzed samples.

Results of GEE

The pooled results of the GEE are summarized in Table 2. The GEE revealed that time (transition from elementary to junior high school) was not significantly associated with SDQ total difficulty scores (β = − 0.161, p = 0.082). EC in 6th grade was negatively associated with SDQ total difficulty scores (β = − 1.823, p < 0.001), whereas autism and ADHD traits were positively associated with SDQ total difficulty scores (β = 1.214, p < 0.001; β = 0.955, p < 0.001, respectively). These results suggest that students with higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC experience more mental health problems across the transition period, regardless of the overall change over time.

Results of LPA

The three-class model demonstrated a favorable balance between model fit and interpretability (BIC = 30,560, Entropy = 0.87) and was therefore selected for further analysis (Table 3). The classification certainty was high across all three classes, with mean posterior probabilities ranging from 0.912 to 0.953. Notably, over 90% of individuals in Classes 2 and 3 had probabilities > 0.8, indicating robust separation. LPA identified three distinct classes characterized by high, moderate, and low SDQ total difficulty scores as the best-fitting model for the data (Fig. 1). Class 1 (n = 150, 5.85%), labeled “High Risk”, was distinguished by the lowest EC scores and highest scores across other measures. Class 3 (n = 1622, 63.26%), labeled “Low Risk”, was characterized by the highest EC scores and low scores across the other measures. Class 2 (n = 792, 30.89%), labeled “Moderate”, exhibited intermediate scores across all measures, falling between those of the other two clusters.

The ANOVA revealed significant differences across all measures (Table 4). Post-hoc analyses indicated that the three groups differed in the severity of autism and ADHD traits, EC, and mental health problems pre- and post-transition. Similar to the GEE findings, students with higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC exhibited more severe mental health problems during the transition. Furthermore, these results suggest that the transition to junior high school may exacerbate pre-existing difficulties. To further examine the variability in mental health changes during the transition period for each class, we plotted the individual score changes (Fig. 2). Moderate (Classes 2) and low risk (class 3) showed relatively consistent patterns, with most students experiencing minimal changes in their mental health problems. Although high risk (Class 1) also showed stable average scores before and after the transition, it demonstrated significantly greater variability in individual change scores than the other classes, as reflected by the wider boxplots at both time points (Fig. 2). In high risk (Class 1), most students showed moderate changes, whereas a notable minority demonstrated either significant improvement or deterioration in their mental health.

Individual trajectories of SDQ from grade 6 to grade 7 by latent profile class. SDQ Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. The blue lines show individual student trajectories. The red lines indicate the mean SDQ score at each time point. The box plots show the distribution of scores (median, quartiles, and range) within each class at each time point.

Discussion

This study aimed to clarify how autism, ADHD traits, and EC are associated with mental health during the transition from elementary to junior high school in a community sample of Japanese students. The GEE revealed that higher EC in 6th grade were associated with lower levels of mental health problems, whereas autism and ADHD traits were associated with higher levels of mental health problems. The LPA identified three distinct classes characterized by high, moderate, and low levels of mental health problems. ANOVA results indicated that students with high autism and ADHD traits and low EC had high levels of mental health problems pre-and post-transition.

Risk factors for mental health problem during school transition

This study showed that higher neurodevelopmental traits and lower EC were associated with more severe mental health problems during the school transition period. Both autism and ADHD traits were positively associated with mental health difficulties during the transition period, consistent with previous research indicating increased school adjustment problems among students with elevated neurodevelopmental traits68,69,70. The results of this study also support research showing that higher ASD traits are associated with lower QoL during the transition to junior high school in a general population sample42. Notably, the GEE results in this study showed that autism traits had stronger associations than ADHD traits, supporting previous findings of heightened vulnerability to transitional changes and difficulties establishing complex peer relationships in secondary school among individuals with autism traits44,71,72. One possible explanation is that, although both autism and ADHD traits are known to be associated with peer problems, the underlying causes differ, which may lead to differences in the strength of these associations73. Autism traits involve fundamental difficulties in social cognition and implicit social processing73,74, which may lead to more persistent peer problems. By contrast, ADHD traits, which affect attention and impulse control, may cause situational peer difficulties73,75. As our model controlled for effortful control (EC), which overlaps conceptually with attentional control, the unique contribution of ADHD traits may have been partially accounted for by EC. In addition, the relationship between ADHD traits and adjustment during school transition appears to be more complex. Environmental changes associated with the transition to middle school76temporarily disrupt the natural age-related decline in ADHD traits32. However, this declining trend resumes after the transition, suggesting that an adjustment process follows the temporary disruption32. Although this decline generally resumes after adjustment, our findings indicate that higher ADHD traits were independently associated with greater mental health difficulties, even after controlling for autism traits and EC. This supports prior research linking ADHD symptoms to academic challenges and maladaptive strategies during the transition33,34. While ADHD and autism traits often co-occur36,37, the current results highlight the independent contribution of ADHD traits to student outcomes, emphasizing the need for tailored support strategies that address both overlapping and distinct profiles of neurodevelopmental risk. Additionally, lower EC was associated with more severe mental health problems. Compared to elementary schools, junior high schools not only have more subjects and mobile classrooms but also have a subject-teacher system instead of a classroom-teacher system. This shift greatly increases students’ autonomy, including the management of homework and submissions, and students are also expected to respond to these needs4,5. Numerous studies have reported a link between school adjustment and EC21,22. Our findings suggest that students with stronger EC capabilities are better equipped to meet these demands. Furthermore, sex was also significantly associated with changes in SDQ scores, with higher scores observed in females. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting higher rates of internalizing problems among adolescent girls77. These results reflect well-established gender differences in adolescent mental health.

LPA identified distinct groups of students characterized by varying combinations of autism and ADHD traits and EC levels. Notably, mental health problems were stable during the transition among all groups, indicating that sixth-grade mental health status tended to persist in the first year of junior high school. This suggests that students with high autism and ADHD traits and low EC do not necessarily experience worsening mental health problems during the transition period; rather, pre-existing mental health challenges persist throughout the transition period. However, although the group with high autism and ADHD traits and lower EC (Class 1; high risk) showed stability in mental health problems during the transition period (Table 4), they demonstrated the largest variability in both scores and their changes compared with the other groups (Fig. 2). This group included many students who showed either remarkable improvement or significant deterioration. These results provide an important insight: Although autism and ADHD traits and EC were associated with post-transition adaptation, which largely manifests as a continuation of previous problems, students with high autism and ADHD traits and low EC demonstrate highly diverse adaptation patterns after entering junior high school, with considerable individual variation. This supports previous inconsistent results from clinical sample studies on autism students and transition, which have reported various outcomes, including improvement45,78,79, deterioration44, and no change46,80. These findings suggest that the association between autism traits and transition is not deterministic. Students with high autism traits do not necessarily experience transition failure or deterioration in post-transition mental health. Although autistic students may face an increased risk of bullying victimization81 and school adaptation difficulties due to sensory sensitivities44,82, some successfully establish appropriate peer relationships, as demonstrated by Kasari and colleagues83,84. Additionally, individual factors such as autism traits alone do not determine mental health problems during the transition, as social contextual factors may also play a role. For instance, research has shown that social contextual factors mediate the relationship between autism traits and mental health outcomes70. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that individual characteristics (e.g., coping skills, resilience, sleep quality), familial functioning, and school-related aspects (e.g., physical learning environment, peer understanding) are associated with psychosocial adjustment in autistic students43,85,86. These factors could help explain the diverse adaptation trajectories observed in students with elevated autism traits. Given the diverse individual adaptation patterns, it may be necessary to pay attention to students who exceed a certain threshold for autism traits or who meet the diagnostic criteria. These students may require attention not only to individual factors, such as sensory features, social skills, and self-regulation, but also to their social context and environmental support for interventions aimed at improving both initial and post-transition school adjustment.

The timing of the assessment may explain these results. In particular, the timing of post-transition evaluation may have overlooked the acute transition effect. For instance, Dillon and Underwood71 found that parents of autistic students reported significant challenges primarily during the immediate transition phase (pre-transition and first semester). Similarly, studies with general population samples have shown improvements in QoL, mental health, and a sense of school belonging by the second semester of the first year after transition. Given that the impact of transition on students begins up to two years before school transition87, our findings highlight the importance of early intervention and support for mental health problems. To better understand transition dynamics, future studies should examine a longer time period—two years before and after the transition—with particular attention paid to the periods immediately before and after the transition. Such extended longitudinal data would provide more comprehensive insights into the trajectory of adjustment and the optimal timing for support interventions.

Changes in mental health during the transition

GEE analysis revealed that mental health problems did not change significantly during the transition period, even though school transitions are often considered challenging owing to the need to adjust for important changes such as school structure. This result is consistent with the previous studies suggesting that certain aspects of psychological adjustment, such as self-esteem and QoL, may improve during early adolescence. For example, Wigfield et al.88 reported an increase in self-esteem during the first year of junior high school after transition, and Whelan et al.42 found improved QoL following school transition in a general population sample. However, studies have shown that behavioral problems increase during adolescence89,90. These contradictory results may stem from parents’ assessment of mental health problems in this study. Given that adolescents are transitioning from parental to peer dependence91, parents may underestimate their mental health issues92. These contradictions highlight the importance of incorporating multiple perspectives when assessing adolescents’ mental health. Future research should include parent and teacher reports as well as self-reports to capture a more comprehensive view of adjustment during this critical transition period.

Strengths and limitations

This study has certain strengths. First, this study examined the association between autism traits and transition in a general population sample, and between autism and ADHD traits and EC deficits in a large community sample. The association between autism traits and transition has only been examined in a few studies with limited sample sizes42,43. Additionally, this study revealed that students with high autism and ADHD traits and low EC exhibited diverse adaptations during the transition period. Second, early identification and support (e.g., sharing information about individuals with difficulties from elementary to junior high school) of students with high autism and ADHD traits and EC deficits is critical for preventing the persistence of mental health problems throughout this critical educational transition. In this study, post-transition outcomes were obtained in the second semester after the summer vacation period in Japan. This period is considered a time when truancy and suicide are likely to increase, and maladjusted conditions at school are likely to become apparent93,94. In this regard, the identification of the relationship between neurodevelopmental traits and mental health at a time when problems are likely to become apparent after the transition will be very important for follow-up and support before and after the transition to middle school in the recent situation in which many students with developmental disability traits are enrolled in mainstream schools. Therefore, this study has important implications for follow-up and support before and after the transition to junior high school.

This study also has a number of limitations. First, mental health was the only outcome variable collected. Previous studies on the transition in samples with autism traits have examined multiple domains, including academic achievement, mental health, and relationships with teachers, as indicators of a successful transition42,95. Thus, although our findings suggest that autism traits can worsen mental health during a transition, these results are insufficient to determine whether the transition was unsuccessful. Second, our data did not include self-reported mental health measures. Self-reporting provides crucial information about mental health in adolescents92,96. Third, we cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured variables influenced the mental health outcomes observed in this study. Factors such as socioeconomic status, availability of school-based support, and relationships between teachers and parents may have played a role in shaping students’ experiences during the transition period95,97. Fourth, our sample was limited to public schools following the standard Japanese educational system. Private schools and integrated schools, which may provide different transition experiences, were not included. Additionally, students with chronic absenteeism could not be assessed, potentially excluding those with the most severe adjustment difficulties. Future research should consider alternative data collection methods to include these vulnerable populations. Finally, although this study utilized a large community-based sample, it was limited to a specific region of Japan. As we could not examine whether the data in this study are representative of Japanese adolescents, the study has limitations regarding the generalizability of our findings to other countries and regions in Japan. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating diverse outcomes, self- and multi-informant data and data from broader regions to better understand transitions in adolescents with neurodevelopmental traits.

Conclusion

This study aimed to clarify how autism and ADHD traits and EC are associated with mental health during the transition from elementary to junior high school. The results revealed that higher EC in 6th grade were associated with fewer mental health problems, whereas autism and ADHD traits were associated with more mental health problems across the transition period, regardless of the overall change over time. Our findings suggest that pre-existing mental health problems tend to persist during the transition period. Furthermore, students with higher autism and ADHD traits and lower EC showed highly diverse adaptation patterns after entering junior high school with considerable individual variation. These findings suggest that students with high autism traits do not necessarily experience transition failure or deterioration in their post-transition mental health.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analysed during the present study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M. & Hunt, J. Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. J. Soc. Issues 59, 865–889. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x (2003).

Midgley, C., Middleton, M. J., Gheen, M. H. & Kumar, R. Stage-environment fit revisited: A goal theory approach to examining school transitions in Goals. In goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (ed. Midgley, C.) 109–142 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2002).

Whitley, J., Lupart, J. L. & Beran, T. Differences in achievement between adolescents who remain in a K-8 school and those who transition to a junior high school. Can. J. Educ. 30, 649–669. https://doi.org/10.2307/20466657 (2007).

Coffey, A. Relationships: The key to successful transition from primary to secondary school?. Improv. Sch. 16, 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480213505181 (2013).

Boller, B. Teaching organizational skills in middle school: Moving toward independence. Clear. House 81, 169–171. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.81.4.169-172 (2008).

Silvers, J. A. Adolescence as a pivotal period for emotion regulation development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.023 (2022).

Merikangas, K. R. et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 49, 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 (2010).

Waters, S. K., Lester, L., Wenden, E. & Cross, D. A theoretically grounded exploration of the social and emotional outcomes of transition to secondary school. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 22, 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.26 (2012).

Rice, F., Frederickson, N. & Seymour, J. Assessing pupil concerns about transition to secondary school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 244–263. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709910x519333 (2011).

Anderson, L. W., Jacobs, J., Schramm, S. & Splittgerber, F. School transitions: Beginning of the end or a new beginning?. Int. J. Educ. Res. 33, 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00020-3 (2000).

Cook, P. J., MacCoun, R., Muschkin, C. & Vigdor, J. The negative impacts of starting middle school in sixth grade. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 27, 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20309 (2008).

Lupien, S. J. et al. The DeStress for success program: Effects of a stress education program on cortisol levels and depressive symptomatology in adolescents making the transition to high school. Neuroscience 249, 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.057 (2013).

Lynch, M. & Cicchetti, D. Children’s relationships with adults and peers: An examination of elementary and junior high school students. J. Sch. Psychol. 35, 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00031-3 (1997).

Bailey, G., Giles, R. M. & Rogers, S. E. An investigation of the concerns of fifth graders transitioning to middle school. RMLE Online 38, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11462118 (2015).

Steinberg, L. & Morris, A. S. Adolescent development. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 52, 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 (2001).

Trotman, D., Stanley, T. & Martyn, M. Understanding problematic pupil behaviour: Perceptions of pupils and behaviour coordinators on secondary school exclusion in an English city. Educ. Res. 57, 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1056643 (2015).

Waters, S. K., Lester, L. & Cross, D. Transition to secondary school: Expectation versus experience. Aust. J. Educ. 58, 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944114523371 (2014).

Rudolph, K. D., Lambert, S. F., Clark, A. G. & Kurlakowsky, K. D. Negotiating the transition to middle school: The role of self-regulatory processes. Child Dev. 72, 929–946. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00325 (2001).

Jaruseviciute, V., Silinskas, G., Muotka, J. & Kiuru, N. Trajectories of adolescents’ adjustment behaviors across the transition to upper secondary education: The role of individual and environmental factors. Learn. Individ. Differ. 112, 102457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2024.102457 (2024).

Rothbart, M. K. & Bates, J. E. Temperament in Handbook of Child Psychology 99–166 (Wiley, 2007).

Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C. & Eggum, N. D. Self-Regulation and School Readiness. Early Educ. Dev. 21, 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.497451 (2010).

Sánchez-Pérez, N., Fuentes, L. J., Eisenberg, N. & González-Salinas, C. Effortful control is associated with children’s school functioning via learning-related behaviors. Learn. Individ. Differ. 63, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.02.009 (2018).

Jacobson, L. A., Williford, A. P. & Pianta, R. C. The role of executive function in children’s competent adjustment to middle school. Child Neuropsychol. 17, 255–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2010.535654 (2011).

Ng-Knight, T. et al. A longitudinal study of self-control at the transition to secondary school: Considering the role of pubertal status and parenting. J. Adolesc. 50, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.006 (2016).

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Retzlaff, P. D. & Espy, K. A. Confirmatory factor analysis of the behavior rating inventory of executive function (BRIEF) in a clinical sample. Child Neuropsychol. 8, 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1076/chin.8.4.249.13513 (2002).

Ozonoff, S. & Jensen, J. Brief report: Specific executive function profiles in three neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023052913110 (1999).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th edn, text revision (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022).

Samyn, V., Roeyers, H. & Bijttebier, P. Effortful control in typically developing boys and in boys with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.038 (2011).

Geurts, H. M., van den Bergh, S. F. W. M. & Ruzzano, L. Prepotent response inhibition and interference control in autism spectrum disorders: Two meta-analyses. Autism Res. 7, 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1369 (2014).

Schmitt, L. M., White, S. P., Cook, E. H., Sweeney, J. A. & Mosconi, M. W. Cognitive mechanisms of inhibitory control deficits in autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12837 (2018).

Roberts, B. A., Martel, M. M. & Nigg, J. T. Are there executive dysfunction subtypes within ADHD?. J. Atten. Disord. 21, 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713510349 (2017).

Langberg, J. M. et al. The transition to middle school is associated with changes in the developmental trajectory of ADHD symptomatology in young adolescents with ADHD. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 37, 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802148095 (2008).

Palmu, I. R., Määttä, S. J., Närhi, V. M. & Savolainen, H. K. ADHD-symptoms and transition to middle school: The effects of academic and social adjustment. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2023.2191106 (2024).

Dvorsky, M. R., Langberg, J. M., Evans, S. W. & Becker, S. P. The protective effects of social factors on the academic functioning of adolescents with ADHD. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 47, 713–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1138406 (2018).

Zendarski, N., Sciberras, E., Mensah, F. & Hiscock, H. Academic achievement and risk factors for adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in middle school and early high school. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 38, 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1097/dbp.0000000000000460 (2017).

Saito, M. et al. Prevalence and cumulative incidence of autism spectrum disorders and the patterns of co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorders in a total population sample of 5-year-old children. Mol. Autism 11, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-020-00342-5 (2020).

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V. & Baron-Cohen, S. Autism. Lancet 383, 896–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61539-1 (2014).

Polderman, T. J., Hoekstra, R. A., Posthuma, D. & Larsson, H. The co-occurrence of autistic and ADHD dimensions in adults: an etiological study in 17,770 twins. Transl. Psychiatry 4, e435. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.84 (2014).

Chiang, H. L. et al. School dysfunction in youth with autistic spectrum disorder in Taiwan: The effect of subtype and ADHD. Autism Res 11, 857–869. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1923 (2018).

Constantino, J. N. & Todd, R. D. Intergenerational transmission of subthreshold autistic traits in the general population. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.014 (2005).

Thapar, A. & Cooper, M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 387, 1240–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00238-X (2016).

Whelan, M., McGillivray, J. & Rinehart, N. J. The association between autism spectrum traits and the successful transition to mainstream secondary school in an australian school-based sample. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 1759–1771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04655-5 (2021).

Whelan, M., McGillivray, J. & Rinehart, N. J. Using life course theory to explore the association between autistic traits, child, family, and school factors and the successful transition to secondary school. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 54, 2333–2346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05845-z (2024).

Dann, R. Secondary transition experiences for pupils with Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASCs). Educ. Psychol. Pract. 27, 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2011.603534 (2011).

Fortuna, R. The social and emotional functioning of students with an autistic spectrum disorder during the transition between primary and secondary schools. Support Learn. 29, 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12056 (2014).

Makin, C., Hill, V. & Pellicano, E. The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: A multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2, 2396941516684834. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941516684834 (2017).

Hirota, T. et al. Cohort profile: The Assessment from preschool to puberty— longitudinal epidemiological (APPLE) study in Hirosaki. Japan. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 1782–1783h. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab112 (2021).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Preliminary results of the 2021 survey on the actual conditions of students not attending school, https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo3/siryo/attach/1325896.htm (2012).

Ehlers, S., Gillberg, C. & Wing, L. A screening questionnaire for asperger syndrome and other high-functioning autism spectrum disorders in school age children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023040610384 (1999).

Ito, H. et al. Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ): Development of a short form. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 85, 304–312. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.85.13213 (2014).

DuPaul, G. J. ADHD rating scale-IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation (Guilford Press, 1998).

Tani, I., Okada, R., Ohnishi, M., Nakajima, S. & Tsujii, M. Japanese version of home form of the ADHD-RS: An evaluation of its reliability and validity. Res. Dev. Disabil. 31, 1426–1433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.016 (2010).

Ellis, L. K. & Rothbart, M 2001 Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire in Poster presented at the 2001 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, https://doi.org/10.1037/t07624-000

Nakagawa, A., Sukigara, M., Matsuki, T. & Furuta, M. Psychometric properties of the Japanese early adolescent temperament questionnaire-revised and comparison between children’s and caregiver’s ratings. Jpn. J. Child Health 79, 545–554 (2020).

Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015 (2001).

Matsuishi, T. et al. Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): A study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev. 30, 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.003 (2008).

Donaldson, C., Hawkins, J., Rice, F. & Moore, G. Trajectories of mental health across the primary to secondary school transition. JCPP Adv. 5, e12244. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12244 (2025).

Göbel, K. et al. Co-occurrence, stability and manifestation of child and adolescent mental health problems: A latent transition analysis. BMC Psychol. 10, 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00969-4 (2022).

Mandy, W. et al. Easing the transition to secondary education for children with autism spectrum disorder: An evaluation of the Systemic Transition in Education Programme for Autism Spectrum Disorder (STEP-ASD). Autism 20, 580–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315598892 (2016).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03 (2011).

Rubin, D. B. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys (Wiley, 1987).

Ballinger, G. A. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104263672 (2004).

Garrett, E. S. & Zeger, S. L. Latent class model diagnosis. Biometrics 56, 1055–1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.01055.x (2000).

Hagenaars, J. A. & McCutcheon, A. L. Applied latent class analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Rosenberg, J. M., Beymer, P. N., Anderson, D. J., Van Lissa, C. J. & Schmidt, J. A. tidyLPA: An R package to easily carry out latent profile analysis (LPA) using open-source or commercial software. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 978. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00978 (2018).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest-non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 (2012).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021). https://www.R-project.org/

Hsiao, M.-N., Tseng, W.-L., Huang, H.-Y. & Gau, S.S.-F. Effects of autistic traits on social and school adjustment in children and adolescents: The moderating roles of age and gender. Res. Dev. Disabil 34, 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.001 (2013).

Kawabata, Y., Tseng, W.-L. & Gau, S.S.-F. Symptoms of attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social and school adjustment: The moderating roles of age and parenting. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 40, 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9556-9 (2012).

Mori, H. et al. School social capital mediates associations between ASD traits and depression among adolescents in general population. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 3825–3834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05687-9 (2023).

Dillon, G. V. & Underwood, J. D. M. Parental perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorders transitioning from primary to secondary school in the United Kingdom. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 27, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612441827 (2012).

Jindal-Snape, D., Douglas, W., Topping, K. J., Kerr, C. & Smith, E. F. Autistic spectrum disorders and primary–secondary transition. Int. J. Spec. Educ 21, 18–31 (2006).

Mikami, A. Y., Miller, M. & Lerner, M. D. Social functioning in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: Transdiagnostic commonalities and differences. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 68, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.12.005 (2019).

Peterson, C., Slaughter, V., Moore, C. & Wellman, H. M. Peer social skills and theory of mind in children with autism, deafness, or typical development. Dev. Psychol. 52, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039833 (2016).

Hoza, B. Peer functioning in children with ADHD. Ambul. Pediatr. 7, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.011 (2007).

DuPaul, G. J. & Stoner, G. ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies 2nd edn. (Guilford Press, 2003).

Wade, T. J., Cairney, J. & Pevalin, D. J. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 41, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013 (2002).

Mandy, W. et al. The transition from primary to secondary school in mainstream education for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 20, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314562616 (2016).

Neal, S. & Frederickson, N. ASD transition to mainstream secondary: A positive experience?. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 32, 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2016.1193478 (2016).

Tobin, H. S. et al. A qualitative examination of parental experiences of the transition to mainstream secondary school for children with an autism spectrum disorder. Educ Child Psychol 29, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2012.29.1.75 (2012).

Hebron, J., Oldfield, J. & Humphrey, N. Cumulative risk effects in the bullying of children and young people with autism spectrum conditions. Autism 21, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316636761 (2017).

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J. & Rodger, S. Sensory processing and classroom emotional, behavioral, and educational outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 62, 564–573. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.5.564 (2008).

Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A. & Rotheram-Fuller, E. Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x (2011).

Locke, J., Williams, J., Shih, W. & Kasari, C. Characteristics of socially successful elementary school-aged children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12636 (2017).

Lebenhagen, C. & Dynia, J. Factors affecting autistic students’ school motivation. Educ. Sci. 14, 527 (2024).

Shochet, I. M. et al. A school-based approach to building resilience and mental health among adolescents on the autism spectrum: A longitudinal mixed methods study. Sch. Ment. Health 14, 753–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09501-w (2022).

Deacy, E., Jennings, F. & O’Halloran, A. Transition of students with autistic spectrum disorders from primary to post-primary school: A framework for success. Support Learn. 30, 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12102 (2015).

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Mac Iver, D., Reuman, D. A. & Midgley, C. Transitions during early adolescence: Changes in children’s domain-specific self-perceptions and general self-esteem across the transition to junior high school. Dev. Psychol. 27, 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.4.552 (1991).

Pellegrini, A. D. & Long, J. D. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 20, 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151002166442 (2002).

Wang, M. T. & Dishion, T. J. The trajectories of adolescents’ perceptions of school climate, deviant peer affiliation, and behavioral problems during the middle school years. J. Res. Adolesc. 22, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00763.x (2012).

Steinberg, L. & Silverberg, S. B. The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child. Dev. 57, 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00250.x (1986).

Sourander, A., Helstelä, L. & Helenius, H. Parent-adolescent agreement on emotional and behavioral problems. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 34, 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050189 (1999).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Jidō seito no mondai kōdō, futōkō tō seito shidōjō no shomondai ni kansuru chōsa [Survey on problem behaviours, non-attendance, and other student guidance issues] https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20211006-mxt_jidou02-000018318_03.pdf (2023).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Annual report on suicide statistics, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/r4h-1-2.pdf (2022).

Richter, M., Maria, P.-R. & Clément, C. Successful transition from primary to secondary school for students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. J. Res. Child. Educ. 33, 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1630870 (2019).

De Los Reyes, A. et al. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol. Bull. 141, 858–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038498 (2015).

Bradley, R. H. & Corwyn, R. F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted by the Graduate School of Medicine at Hirosaki University, in close collaboration with the Hirosaki City Board of Education. The authors express gratitude to all the participants, their families, and teachers. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of local practitioners, public officers.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Hirosaki Institute of Neuroscience in Japan (K. N.), Hirosaki University, Institutional Research Grant (K. N.), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED): Project for Baby and Infant in Research of health and Development to Adolescent and Young adult–BIRTHDAY, grant number JP23gn0110071 (M. A. and K. N.), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, grant numbers 23K12818 (H. M.), 23K22349 (M. T.), 23K22358 (M. A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception and design were performed by Hiroyuki Mori, Michio Takahashi, Masaki Adachi, Hiroki Shinkawa, Makoto Osada, Minami Adachi, and Kazuhiko Nakamura. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Hiroyuki Mori, Michio Takahashi, Masaki Aadachi, and Hiroki Shinkawa. Data analyses were performed by Rei Monden. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Hiroyuki Mori. Michio Takahashi, Masaki Adachi, Hiroki Shinkawa, and Tomoya Hirota critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians. Informed assent was obtained from the children participating in the study. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine (IRB# 2015–055).

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mori, H., Takahashi, M., Monden, R. et al. Autism and ADHD traits, effortful control and mental health during the transition from elementary to junior high schools. Sci Rep 15, 42262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26430-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26430-1