Abstract

In recent years, artichokes have gained attention as functional foods due to their polyphenol content and health benefits. While Italian varieties have been widely studied, the Slovenian landrace “Strunjanska articoka” remains largely unexplored. This study compared “Strunjanska articoka” with two Italian varieties, “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”, assessing genetic profiles, chemical composition, antioxidant activity, and effects on lipid accumulation. The genetic analysis confirmed the uniqueness and clear differentiation of the landrace “Strunjanska articoka” from the two commercial varieties. Analysing the profiles of phenolic compounds in the leaf extracts of these morphologically different artichoke varieties underlines their unique phytochemical composition, which translates into different health benefits. “Romanesco” showed the highest free radical scavenging activity (EC50 = 100 µg/mL), followed by “Strunjanska articoka” (EC50 = 143 µg/mL), and “Violetto di Romagna” (EC50 = 160 µg/mL). Importantly, “Strunjanska articoka” demonstrated superior cytoprotective effects against oxidative stress in HepG2 and CCD112CoN cells. It also reduced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells, along with “Violetto di Romagna,” whereas “Romanesco” did not. These findings justify further investigation into the potential therapeutic effects of “Strunjanska articoka” and support the rationale for its cultivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the artichoke, Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus (L.) Fiori, (formerly Cynara scolymus L.) has seen renewed interest in functional foods. This ancient herbaceous perennial plant, native to the Mediterranean region, is widely cultivated for its immature composite inflorescences, also known as flower head or capitulum. The flower heads are harvested before the flowering, and the entire “heart” (receptacle and lower parts of the outer and inner bracts) and the undeveloped “choke” (immature florets, bristles and pappus) are edible. The part of the stem directly below the young flower head is also edible1,2. The artichoke is a rich source of bioactive phenolic compounds, inulin, and other fibre and minerals, making it an important component of the Mediterranean diet3,4.

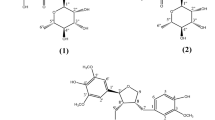

Artichoke is not only a healthy food known for its pleasant bitter taste, but also an interesting and widespread herbal drug. Artichoke leaf extracts (ALEs) are widely used alone or in combination with other herbs for embittering alcoholic and soft drinks and also to prepare herbal teas or other herbal medicinal products5. Polyphenolic compounds, present mainly in the leaves rather than in the artichoke heads, have been documented as the primary active substances of this plant6. ALEs have been traditionally used in the treatment of liver disorders and valued for their choleretic, diuretic, hepatoprotective, and lipid-lowering effects7. These effects have been confirmed in various pharmacological studies demonstrating that ALEs exhibit hepatoprotective8, anticarcinogenic9,10, antioxidative9,11, antibacterial9, anti-HIV, choleretic, and diuretic activities, as well as the ability to inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis and LDL oxidation12. These broad therapeutic indications cannot be ascribed to a single, but to several active compounds that together generate additive or synergistic pharmacologic effects. These include mono- and dicaffeoylquinic acids, among which cynarin (1,3-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid) is the most typical, flavonoids such as luteolin and its 7-O-glucoside, and silymarin flavonolignans7.

Artichoke plays an important role in human nutrition, especially in the Mediterranean region, where it contributes significantly to the agricultural economy, with an annual production of about 1,585,000 t from over 113,000 ha of cultivated land. Egypt is the leading world producer, followed by Italy, Spain and Greece13.

The germplasm of artichoke includes about 100–120 genotypes grouped in relation to harvesting time (“early” or “late”) and to morphological characteristics (for example: the colour of the external bracts and presence/absence of spines)14. Nevertheless, the number of genotypes with significant commercial importance is limited to 11–1215, and only a few varieties are cultivated globally. In Italy the main varieties are: “Violetto di Sicilia”, “Brindisino”, “Violet de Provence”, “Romanesco” and “Spinoso Sardo”. In France the predominant varieties are “Camus de Bretagne”, “Gros Vert de Laon”, “Blanc Hyerois”, “Violet du Gapeau”, “Castel” and “Petit Violet de Provence”, while in Spain “Blanca de Tudela” remains the most widely grown16.

Archaeobotanical and historical evidence support the hypothesis that the artichoke may have been domesticated in Sicily (southern Italy) at the time of the Romans17,18. The preservation of artichokes over the centuries has contributed to its great diversity and has led to the cultivation of several heterogeneous landraces that generally have a lower yield than commercial varieties, but are well suited to specific uses, tolerant to environmental stresses and adaptable to a low-input farming system. Italy has recognized the importance of preserving its agrobiodiversity and has implemented various measures to conserve these artichoke landraces both in situ and ex situ19,20.

In Slovenia, the best-known indigenous landrace is the “Strunjanska articoka” (Eng. ‘’Strunjan artichoke”). Its denomination is derived from the name of the small village – Strunjan in Slovenian Istria (a region in south-western Slovenia with a sub-Mediterranean climate) where it grows. It is characterised by small flower heads with intense purple colour. They are commonly planted in small plots or as individual plants in home gardens. Their production is low, but very important for the local coastal communities21. Although there is no direct historical evidence of its origin, the recognition of the artichoke in this region is the result of decades of efforts by local producers who have created the unique gene pool of the “Strunjanska articoka” through the selection of plants and various propagation methods21. Based on a preliminary genetic study with microsatellites conducted at the University of Primorska, Faculty of Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Information Technologies, the landrace “Strunjanska articoka” is characterised by several molecular variants – clones with one well-defined clone predominantly present in local nurseries21,22. The multiclonal composition is probably the result of alternating vegetative (green plant parts) and generative (seeds) propagation in the past. According to the field data, the current propagation method consists of dividing green shoots that grow from the basal part of the mother plants. Over the decades, this has led to a distinct gene pool of “Strunjanska articoka”, which has not yet been systematically exploited23, but holds considerable potential for larger-scale cultivation in Slovenia.

It is well known that the concentrations and the profile of polyphenolic compounds of artichoke and thus its antioxidant activities are influenced by biotic (genotype, plant tissue/organs, pathogens) and abiotic (environment, agronomic practices, harvesting time, etc.) conditions24,25. However, in contrast to the thoroughly investigated Italian artichoke varieties26,27,28,29, the characteristics of “Strunjanska articoka” remain entirely unexplored. Therefore, a comprehensive comparison between “Strunjanska articoka” and two widely cultivated Italian varieties, “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna” is presented. Specifically, the study assesses their genetic profiles, leaf polyphenol composition, antioxidant potential and lipid-lowering properties. By highlighting genotype-related differences in bioactivity, this research supports the valorisation of a culturally significant landrace and contributes to a broader understanding of its potential. Ultimately, the findings are expected to contribute to the sustainable cultivation and conservation of artichoke genetic resources and to promote the preservation of the local agricultural heritage.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The planting material (seedlings) of the commercial varieties “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna” was provided by the nursery Orto Mio Ltd. (Italy), while the seedlings of local landrace were obtained from the main Slovenian producer from Strunjan (Slovenia). All plants were grown under the same conditions in a field collection in Osp (45°34′35.2″N 13°51′03.5″E, Slovenia), where the leaves were harvested. The first morphological description of the landrace “Strunjanska articoka” was performed in 2024 on 10 clonally propagated and randomly selected plants when the central flower head reached commercial maturity (mid-May 2024). For each plant, morphological data were recorded based on the standardized descriptors of UPOV (International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants), including 14 quantitative characteristics related to the leaf and the edible, commercially important part of the plant: central flower head and first flower head on the lateral shoot.

Representative sample of cca. 200 g of fresh weight of leaves were collected from 5 plants per variety/landrace before the maturation of central flower head in May 2024. A subsample of fresh leaves was used for DNA extraction, while the remaining sample was washed and air-dried at room temperature, protected from light for 12 days. Dried plant material was then milled and stored at − 20 °C until further use. For DNA extraction, leaf samples were collected from each variety/landrace and stored in a saturated NaCl-CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) conservation buffer30.

DNA extraction and microsatellite markers analysis

Total genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves using the modified CTAB-polyvinylpyrrolidone (CTAB-PVP) protocol31, as reported previously32. DNA extracts were deposited in the genetic laboratory of the University of Primorska, Slovenia under the accession numbers A-59 (“Romanesco”), A-60 (“Violetto di Romagna”), and A-65 (“Strunjanska articoka”). The concentration of DNA was measured with Qubit™ v.3.0 fluorometer and Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA). A set of twelve microsatellite markers was selected from previous genetic studies of globe artichoke germplasm based on their genetic diversity parameters: CyEM120, CyEM135, CyEM181, CyEM185, CyEM199, CyEM207, CyEM221, CyEM236, CyEM25433, CELM05, CELM14, CELM4034. PCR reactions in a total volume of 12.5 µL, containing 40 ng DNA, 1 x supplied AllTaq PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 x supplied Q-Solution, 1.25 U of AllTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 0.2 mM reverse locus specific primer, M13(-21) tail labelled with fluorochrome (6-FAM, VIC, NED or PET) and 0.1 mM elongated forward primer. Locus specific primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Leuven, Belgium) and universal M13(-21) primer by Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification of the DNA was performed in a SimpliAmp™ Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The two-step amplification profile consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles (step 1) of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s, followed by eight cycles (step 2) of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s. Final extension was carried out at 72 °C for 8 min35. Fragment analysis was conducted using PCR product mix (including amplicons with four different fluorescent dyes), Hi-Di™ Formamide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Woolston, UK), GeneScan™ 500 LIZ size standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Woolston, UK) and SeqStudio™ Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Singapore). The allele calling was done with GeneMapper version 5 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), the alleles amplified on a define locus were additionally checked using the GenAlEx v.6.5.1 computer software (Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton, Australia)36.

Artichoke leaf extract preparation

In traditional medicine water extracts of either fresh or dried artichoke leaves are most frequently used37. Hot water extracts (i.e., infusions) were prepared by immersing 3 g of dried and milled plant material (artichoke leaves) in 150 mL of boiling hot water for 10 min and then filtered through a Whatman paper. The drug to solvent ratio used was the same as stated in the Herbal monograph on Cynarae folium. For cell culture experiments, ALEs were additionally sterilized by passing through a 0.2 μm sterile cellulose acetate membrane filter to ensure sterility and prevent contamination. Filtered and aliquoted extracts were then kept at − 20 °C until analysis.

Phenolic profile determination by HPLC

Phenolic compounds in the obtained extracts were analysed using HPLC Agilent 1200 series (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm) and a diode array detector (DAD). Chromatographic separation employed a linear gradient of methanol (solvent A) and 1% formic acid in water (solvent B) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a temperature of 30 °C. The gradient program was as follows: 85% B; 0–6,2 min, 85% B; 6,2–8 min, 85–75% B; 8–13 min, 75–61% B; 13–15 min, 61% B; 15–20 min, 61–40% B; 20–25 min, 40–0% B. The total run time was 25 min, followed by a 10 min post-run for column re-equilibration. Detection was performed at wavelengths of 280 nm, 330 nm, and 350 nm, with spectra recorded from 190 to 400 nm. The method has been validated for linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), precision, and accuracy in our previous studies38,39. Apart from luteolin derivatives, caffeic acid derivative and ferulic acid derivative, identification of phenolic compounds was performed by comparing the retention times and spectra of phenolic compounds present in the ALEs with those of the corresponding external standards. Luteolin derivatives (UV λmax in MeOH 254, 268, 346 nm), caffeic acid derivative (UV λmax in MeOH 243, 298, 328 nm) and ferulic acid derivative (UV λmax in MeOH 234, 288, 322 nm) were identified on the basis of their spectral characteristics, as reported previously40,41 and expressed in luteolin, caffeic acid and ferulic acid equivalents, respectively, due to the lack of the corresponding external standards.

Radical scavenging activity assay

The antioxidant activity of ALEs was measured in terms of their radical-scavenging ability in the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical assay as reported previously42. Reaction mixtures containing 19.5 to 2500 µg/mL of ALEs and 0.1 mM DPPH solution in methanol or methanol alone were prepared in 96-well microtiter plates and incubated at ambient temperature for 60 min in the dark (extract concentrations ranged from 0.1% to 12.5% (v/v)). Chlorogenic acid was used as a positive control. The decrease in absorbance (A) of the DPPH radical was measured at 515 nm on the Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the radical scavenging activity was calculated as a percentage of DPPH discoloration using the equation:

EC50 values were determined graphically from the curves. Results were also expressed as mg of chlorogenic acid equivalents (CAE) per grams of dry plant material. Each test was performed in two parallels and repeated twice.

Cell cultures

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells Caco-2 (ATCC® HTB37™), primary colon fibroblasts CCD112CoN (ATCC® CRL1541™), and human liver cancer cell line HepG2 (ATCC® HB-8056™) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection® (ATCC®, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s high glucose medium (DMEM) containing 1 g/L glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mM glutamine. All cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For all cell culture experiments, sterile ALEs were mixed directly with cell culture media, and the concentrations are expressed in v/v percentages. The extract volumes were selected based on assay sensitivity and cytotoxicity screening results. Concentrations are reported both as % (v/v) and mass/volume (mg/mL or µg/mL): (a) Cell viability (cytotoxicity) assay: concentrations ranged from 2% to 0.063% (v/v), corresponding to 0.4 mg/mL – 12.6 µg/mL; (b) Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay (cytoprotective effects): we used the highest non-cytotoxic concentration, along with lower concentrations ranging from 0.125% to 0.008% (v/v), corresponding to 25 µg/mL – 1.6 µg/mL; (c) Lipid droplet accumulation assay: only the highest non-cytotoxic concentration (0.125% (v/v), corresponding to 25 µg/mL) was used. Concentrations were also standardized to rutin equivalents (µmol/L) for comparison with other studies: the highest non-cytotoxic concentration used in b) and c) (0.125% (v/v) or 25 µg/mL) corresponds to approximately 6.63 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Violetto di Romagna”, 10.78 µmol/L for “Strunjanska articoka”, and 2.54 µmol/L for “Romanesco”.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability after exposure to ALEs was determined using PrestoBlue™ reagent (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Caco-2 and HepG2 cells were plated on 96-well plates in the concentrations of 10.000 cells per well and CCD112CoN were plated in concentration of 5.000 cells per well. Cells were then left to adhere to the plates for 24 h. The next day, cells were treated with ALEs diluted in cell culture media for 24 h (concentrations ranged from 2% to 0.063% (v/v), corresponding to 0.4 mg/mL – 12.6 µg/mL). PrestoBlue™ was added and after 30 min fluorescence was measured on a microplate reader Infinite F200 (Tecan Group Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland) at excitation/emission (ex/em) wavelength of 535/595 nm.

Intracellular level of reactive oxygen species

Intracellular oxidative stress levels were evaluated using the 2ʹ,7ʹ-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate (DCF-DA) assay. Caco-2, HepG2, and CCD112CoN cells were plated on black, clear-bottom 96-well plates at concentrations of 10.000 and 5.000 cells per well, respectively, and left to adhere to the plates for 24 h. Cells were pre-treated with different non-cytotoxic dilutions of ALEs for 24 h, whereas non-treated cells served as controls. We used the highest non-cytotoxic concentration, along with lower concentrations ranging from 0.125% to 0.008% (v/v), corresponding to 25 µg/mL – 1.6 µg/mL. Additionally, 0.125% (v/v) corresponds to approximately 6.63 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Violetto di Romagna”, 10.78 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Strunjanska articoka”, and 2.54 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Romanesco”. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and exposed to DCFH-DA in a final concentration of 50 µM and freshly prepared tert-butyl hydroperoxide solution (t-BOOH, 250 µM in cell culture media without phenol red). The resulting increase in fluorescence was determined immediately and after 30 min of incubation at room temperature using a microplate reader Infinite F200 (Tecan Group Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland), at ex/em of 485/535 nm. The fluorescence increase is expressed as relative fluorescence, where the fluorescence of the control sample is set to 100. The cell images were acquired using Olympus IX51 TH4-200 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a digital camera and cellSens Dimension software at a 40x magnification.

Lipid droplet accumulation

For the oil red O (ORO) staining, HepG2 cells were seeded on 24-well plates, left to adhere overnight, and starved in serum-free DMEM with 1% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 24 h. Cells were then incubated in a medium with 250 µM Na-palmitate with or without ALEs (only the highest non-cytotoxic concentration was used). The highest non-cytotoxic concentration 0.125% (v/v) corresponds to 25 µg/mL and to approximately 6.63 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Violetto di Romagna”, 10.78 rutin equivalents µmol/L for “Strunjanska articoka”, and 2.54 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Romanesco”. After 24 h of treatment, lipid droplets in HepG2 cells were revealed with an ORO staining kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cell images were acquired using Olympus IX51 TH4-200 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a digital camera and cellSens Dimension software at a 400x magnification. Previously stained cells were then exposed to 500 µL of isopropanol per well to solubilize the lipid droplets. Three aliquots of the obtained solution were transferred to a 96-well plate and the red coloration, proportional to the lipid droplet accumulation in the HepG2 cells, was measured spectrophotometrically with Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 517 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± relative standard deviation (RSD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). Differences in phenolic compound concentrations among the three artichoke varieties were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. For in vitro assay comparisons between varieties, independent samples t-tests were used. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Morphological description of “Strunjanska articoka” and genetic diversity analysis with microsatellite markers

The Slovenian landrace “Strunjanska articoka” has not yet been registered as variety and thus is not included on the List of Plant Varieties (the official list of plant varieties that have completed the registration procedure in the Republic of Slovenia). The flower heads of “Strunjanska articoka” are spherical and not spiny and have a characteristic purple colour (Fig. 1). The measurement of selected quantitative traits (Supplementary Table S1) of ten clonally propagated plants, done in 2024, revealed that the mean plant height (including the central flower head) is 90.98 cm, the main stem reaches an average height of 85.88 cm and has a mean diameter of 1.25 cm.

The leaves are elongated with an average length of 75.90 cm and have an average of 18 lobes per leaf (Fig. 2A). The central flower head has an average length of 5.16 cm and a diameter of 5.57 cm (Fig. 2B) and has a compact appearance. The outer bracts have an average length at the base of 1.19 cm, a width at the base of 2.28 cm and a thickness of 0.46 cm (Fig. 2C). The first flower head on lateral shoots is smaller, with an average length of 2.64 cm and a diameter of 2.44 cm.

The shape of the central flower head is ovate in longitudinal section with a rounded apex. The external side of fleshy outer bracts are mainly violet with an emarginated apex. The density of the scarious inner bracts is medium, and the shape of receptacle is moderately depressed (Fig. 3).

It is well known that both environmental factors and the genotype contribute significantly to the synthesis of plant metabolites and thus to their biological effects. For this reason, genetically profiling of the two commercially available artichoke varieties, “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna” and local landrace “Strunjanska articoka”, widely spread in the Slovenian Istria, was performed. Microsatellite profiles of all three artichoke samples across 12 microsatellite loci and the number of shared alleles between samples are presented in Fig. 4. Examination of the 12 microsatellite regions revealed 16 alleles in “Romanesco”, 22 alleles in “Violetto di Romagna” and 21 alleles in “Strunjanska articoka”. The similar number of amplified alleles per variety/landrace was found in all three artichoke samples, indicating comparable polymorphism detected. A total of 44 alleles were detected, with the number of alleles per locus ranging from three (CyEM181, CyEM221, CyEM26, CyEM254, CELM3) to five (CyEM135) (Fig. 4A). Microsatellite analysis revealed a large number of genotype specific alleles (Fig. S1). Variety “Violetto di Romagna” had 11 unique alleles (25% of total) while in “Strunjanska articoka” landrace, 15 unique alleles (34% of total) were found. Only 5 specific alleles were characteristic to “Romanesco” variety (Fig. 4B). Seven identical alleles were detected in varieties “Violetto di Romagna” and “Romanesco”, while “Strunjanska articoka” landrace shared only two identical alleles with “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”.

Microsatellite profiles of “Romanesco”, “Violetto di Romagna”, and “Strunjanska articoka” across 12 loci. Colours in the cells indicate the presence of allele. Sizes of alleles are expressed in base pair (bp) (A). Allelic diversity revealed by the set of 12 microsatellite markers is graphically presented. The number (Nu) and the proportion of variety/landrace-specific (unique) alleles (Nu) for “Violetto di Romagna” (Nu = 11; 25%), “Romanesco” (Nu = 5; 11%) and “Strunjanska articoka” (Nu = 15; 34%), and the number of shared alleles (Ns) among analysed varieties/landrace is shown (B).

Chemical profile of artichoke leaf extracts

The analysis of ALEs revealed a diverse array of phenolic compounds, each contributing uniquely to the bioactivity of the investigated varieties/landrace. The results from HPLC analysis; the quantities of the identified compounds of all the ALEs are presented in Table 1 and Fig. S2. Among all phenolic acids, caffeic acid was the most abundant compound in the investigated artichoke varieties/landrace. The highest concentration was detected in “Romanesco” variety (59.31 mg/g), followed by “Violetto di Romagna” and landrace “Strunjanska articoka” (46.97 mg/g and 40.16 mg/g, respectively). Additionally, caffeic acid derivatives, including those identified at 13.91 min were tentatively identified as dicaffeoylquinic acid (cynarin), based on the retention time and UV spectral data as reported previously40,41. UV-Vis spectra of tentatively identified phenolic compounds are provided in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S3), while representative HPLC chromatograms of the three artichoke varieties are shown in Fig. S2. The chromatograms highlight clear differences in peak patterns and relative abundances, suggesting variety-specific phenolic profiles that may underlie differences in antioxidant capacity and related bioactivities.

Protocatechuic acid and other phenolic acids were present at varying levels across the varieties/landrace. p-Coumaric acid, for example, was detected in moderate amounts, with “Violetto di Romagna” exhibiting the highest concentration (1.00 mg/g). The landrace “Strunjanska articoka” was also notable for its significant levels of sinapic acid (2.42 mg/g), followed by “Romanesco” (2.05 mg/g) and “Violetto di Romagna” (1.10 mg/g). When considering gallic acid, the “Strunjanska articoka” (0.0361 mg/g) and “Romanesco” (0.0473 mg/g) showed significantly higher concentrations than “Violetto di Romagna” (0.0035 mg/g). Finally, ferulic acid derivatives were predominantly found in “Violetto di Romagna” (19.48 mg/g), and lower amounts in “Romanesco” (17.24 mg/g) and “Strunjanska articoka” (14.32 mg/g). Syringic acid was detected exclusively in the “Violetto di Romagna” variety (0.52 mg/g). Rosmarinic acid was most concentrated in the same, “Violetto di Romagna” variety (8.47 mg/g). However, “Strunjanska articoka” also exhibited high level of rosmarinic acid (7.51 mg/g), while “Romanesco” contained almost half the amount (3.94 mg/g). These results suggest that while all three genotypes possess meaningful amounts of this compound, “Romanesco” may have a comparatively reduced bioactive potential in terms of rosmarinic acid content. Regarding flavonoid compounds, rutin and luteolin derivatives were the most abundant. The “Strunjanska articoka” landrace was particularly rich in rutin (263.37 mg/g), exhibiting higher level than those in “Violetto di Romagna” (161.59 mg/g) and “Romanesco” (61.96 mg/g). In addition, two luteolin derivates were detected at 13.4 and 15.98 min, which according to the literature data (spectra and RT) can be assigned to luteolin 7-O-rutinoside and luteolin 7-O-glucoside (cynaroside), respectively41. Concentrations of luteolin 7-O-rutinoside were significantly higher in “Romanesco” (113.56 mg/g) and “Strunjanska articoka” (91.20 mg/g), both surpassing “Violetto di Romagna” variety (58.11 mg/g). Moreover, catechin and epicatechin were found in substantial quantities in “Romanesco” (0.52 mg/g and 1.89 mg/g, respectively) and “Violetto di Romagna” variety (0.42 mg/g and 1.84 mg/g, respectively), while “Strunjanska articoka” exhibited a reduced concentration of catechin compared to the other two varieties.

Radical scavenging activity

The DPPH test was used to determine the in vitro antioxidative potential of ALEs. A comparison of the extracts prepared from landrace “Strunjanska articoka” and the two commercial varieties revealed the highest radical scavenging activity of “Romanesco” ALE, which was in the tested concentration of 156 µg/mL comparable to the activity of 8 µg/mL chlorogenic acid (CA) and reached approx. 75% inhibition of DPPH (Fig. 5). The extracts of “Strunjanska articoka” and “Violetto di Romagna” in the same concentration inhibited 55 and 50% of DPPH, respectively, whereas approx. 75% inhibition of DPPH was reached at concentration of 312 µg/mL for both ALEs. As shown in Fig. 5, at concentrations of 156 µg/mL, 78 µg/mL, and 39 µg/mL, “Romanesco” consistently showed significantly greater antioxidant activity compared to both “Violetto di Romagna” and “Strunjanska articoka”. Moreover, EC₅₀ for “Romanesco” extract was 100 µg/mL and was significantly lower than that of “Strunjanska articoka” (143 µg/mL, p = 0.002) and “Violetto di Romagna” (160 µg/mL, p = 0.003), indicating higher antioxidant activity of “Romanesco”. EC50 for CA was 4.4 µg/mL.

Radical scavenging activity of the artichoke leaf extracts measured by the DPPH test. “Strunjanska articoka”– grey solid line, “Romanesco” – grey dashed line, and “Violetto di Romagna” – grey dotted line in comparison to chlorogenic acid (CA) – black solid line. Mean ± RSD is presented. a, significant differences in radical scavenging activity between “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”. b, significant differences in radical scavenging activity between “Romanesco” and “Strunjanska articoka”. c, significant differences in radical scavenging activity between chlorogenic acid (control) and all three artichoke leaf extracts varieties.

Cytotoxicity and the protective effect from oxidative stress induction

The cytotoxicity of all three ALEs was inspected for cancerous colon cells Caco-2, liver cells HepG2, and primary colon fibroblasts CCD112CoN with PrestoBlue™ assay, and the results are presented in Fig. 6. ALE prepared from “Violetto di Romagna” variety was toxic at 50 µg/mL (0.25% (v/v)) concentration (6.63 µmol/L rutin equivalents) for all three cell lines. On the other hand, ALEs prepared from “Romanesco” variety and “Strunjanska articoka” landrace were more toxic for Caco-2 and HepG2 cells (both at 25 µg/mL or 0.125% (v/v) concentration; 10.78 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Strunjanska articoka” extract, and 2.54 µmol/L for “Romanesco”), and less toxic for primary colon CCD112CoN cells (“Romanesco” at 100 µg/mL or 0.5% (v/v) concentration and “Strunjanska articoka” at 50 µg/mL or 0.25% (v/v) concentration). For further experiments, non-cytotoxic test concentrations were used.

Cytotoxicity of artichoke leaf extracts as determined by the PrestoBlue Assay in (a) Caco-2 cells, (b) HepG2 cells, and (c) CCD112CoN cells. Black column – “Strunjanska articoka”; grey column – “Violetto di Romagna”; white and grey column (in the middle) – “Romanesco”. The mean ± RSD of five replicates is presented. Asterisk denotes statistical significance of treated cells compared to control, * p < 0.05.

To determine the protective effect of ALEs against oxidative stress induction, DCFH-DA assay was employed. In Caco-2 cells, all prepared ALEs at the highest tested concentration (0.125% (v/v)) reduced the level of ROS to approximately 82%. The effect of ALE from landrace “Strunjanska articoka” was more pronounced in HepG2 cells than in Caco-2 cells, where it increased with the concentration and reached a reduction to 70 ± 5% at a 25 µg/mL or 0.125% (v/v) concentration (10.78 µmol/L rutin equivalents). ALE prepared from “Romanesco” variety reached a reduction to 88 ± 3% at a 25 µg/mL or 0.125% (v/v) concentration (2.54 µmol/L rutin equivalents) in HepG2 cells, whereas in primary colon CCD112CoN cells its effects were not significant (only 10% reduction in ROS generation). In CCD112CoN, only ALE form “Strunjanska articoka” exerted significant effect and reached a reduction of 80 ± 3% at a highest concentration tested. ALE prepared from “Violetto di Romagna” variety had no significant effect in cancerous HepG2 nor in CCD112CoN primary colon cells (Fig. 7).

Protective effect of artichoke leaf extracts against oxidative stress induction, determined with DCFH-DA assay in (a) Caco-2, (b) HepG2, and (c) CCD112CoN cells. Black column – “Strunjanska articoka”; grey column – “Violetto di Romagna”; white and grey column – “Romanesco”. The mean ± RSD of five replicates is presented. Asterisk denotes statistical significance of treated cells compared to control, * p < 0.05.

Lipid droplet accumulation

Due to the known lipid-lowering properties of artichokes, we further investigated the effects of all three extracts on the lipid droplet accumulation in HepG2 cells. ORO staining showed no direct effect of ALEs prepared from “Strunjanska articoka” or “Romanesco” variety on the accumulation; while ALE prepared from “Violetto di Romagna” reduced it significantly (Fig. 8). In cells treated with Na-palmitate, the absorbance at 517 nm was 1.24 ± 0.03-fold higher compared to control cells, showing that Na-palmitate treatment increased lipid accumulation in the control cells. The addition of “Strunjanska articoka” extract, significantly reduced the Na-palmitate-induced accumulation (p = 0.03). ALE of “Violetto di Romagna” prevented the Na-palmitate-induced accumulation to a similar extent (p < 0.001). On the other hand, the addition of “Romanesco” ALE did not exert such activity after the addition of Na-palmitate (Fig. 8).

HepG2 cells stained with oil red O after the treatment with Na-palmitate, Na-palmitate and artichoke leaf extract (25 µg/mL or 0.125% (v/v); 6.63 µmol/L rutin equivalents for “Violetto di Romagna”, 10.78 µmol/L for “Strunjanska articoka”, and 2.54 µmol/L for “Romanesco”) or artichoke leaf extract compared to control (non-treated cells). a denotes statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between non-treated control cells and cells treated with specific extract; b denotes statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between cells treated with Na-palmitate and cells treated with Na-palmitate and specific extract.

Discussion

In recent years, consumer demands have increasingly shifted towards diverse and healthy foods. Studies have highlighted the numerous health benefits of the artichoke, which has led to its recognition and use as a functional food43. This study represents the first comprehensive characterization of the Slovenian landrace “Strunjanska articoka” comparing its genetic, morphological and biochemical properties in comparison to the commercially available varieties “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”. Genetic analysis using microsatellite markers confirmed a clear differentiation among “Strunjanska articoka”, “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”. Unique alleles, characteristic to the particular variety or landrace, confirmed the usefulness of selected microsatellite loci in the identification process and can support the control of authenticity of the artichoke products with quality labels. The high number of unique alleles found in “Strunjanska articoka” and the low number of shared alleles with the other two commercially available varieties confirmed the genetic distinctiveness of “Strunjanska articoka”. From the first morphological description, although performed only with the plant material from one season, it can be concluded that Slovenian landrace “Strunjanska articoka” belongs to the “Romaneschi” group, similar to the “Romanesco” variety. Shared phenotypic traits, distinct differences in morphological development and inflorescence structure were observed. The “Romanesco” variety is a classic artichoke that originates from the local “Romanesco” germplasm of the Lazio region (province in mid-western Italy) and is characterised by large, spherical flower heads with a distinct purple-green colour. The variety “Romanesco” reaches a comparable plant height to the “Strunjanska articoka” (60–90 cm) but is characterized by significantly larger flower heads of 7–9 cm in length and a significantly wider main flower stem with a diameter of 2–3 cm44,45.

By analysing the phenolic compound profiles in the landrace “Strunjanska articoka” and varieties “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna”, the presented study highlights their unique phytochemical composition associated health benefits. According to the literature, genetic material, plants’ physiological stage of development, plant organ, and the environment during plant growth, as well as other factors such as agricultural management, postharvest practices and extraction methods, can significantly affect phenolic content7,46. Reported total phenolic contents (expressed as gallic acid equivalents) in different plant parts (leaves, bracts, receptacles, flowers, and stalks) vary between 1191 and 3496 mg/100 g. Flavonoids (expressed as quercetin equivalents) vary between 40.1 and 75.5 mg/100 g, and anthocyanins varies between 0.84 and 170.5 mg/100 g47. Furthermore, the caffeoylquinic derivative content of artichoke tissues is highly dependent on the physiological stage of the tissues: the total caffeoylquinic acid content ranges from about 8% on dry matter basis in young tissues to less of 1% in senescent tissues7.

Although the quantitative and qualitative variations of bioactive compounds in artichoke leaves depend on many environmental, harvest and postharvest factors, all samples in this study were collected and processed under the same conditions, confirming that varietal differences were the main source of variation in the chemical composition. The HPLC analysis enabled clear differentiation between these varieties based on their phenolic profiles, which can, alongside other identification methods, offer a reliable approach for varietal identification and characterization. Notable differences were observed in the concentrations of key bioactive compounds; “Strunjanska articoka” stands out with the highest rutin content (263.37 mg/g), while “Romanesco” showed elevated levels of luteolin derivatives and “Violetto di Romagna” stood out for its unique syringic acid content and high concentration of rosmarinic acid. While “Romanesco” was very rich in caffeic acid (50.3 mg/g), “Strunjanska articoka” and “Violetto di Romagna” had approximately 3-times higher amount of cynarin – derivate of caffeic acid41, a compound that can enhance the overall bioactivity through synergistic interactions, amplifying antioxidant effects and providing added protection against oxidative stress. The “Strunjanska articoka” landrace was also notable for its significant levels of sinapic acid (2.42 mg/g) and rosmarinic acid (7.31 mg/g). The ability to distinguish these varieties based on their phenolic profiles provides valuable insights into their functional properties and also highlights the potential for selective breeding and sustainable cultivation practices, particularly for “Strunjanska articoka”.

In terms of biological activity, ALE prepared from “Strunjanska articoka” exhibited superior antioxidative properties in different cell line models to the extracts from “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna” and was especially efficient in protecting primary colon cells CCD112CoN against oxidative stress. However, the highest concentration of the caffeic acid and the highest radical scavenging activity has been detected for “Romanesco” ALE (EC50 = 100 µg/mL), followed by “Strunjanska articoka” (EC50 = 143 µg/mL), and “Violetto di Romagna” ALE (EC50 = 160 µg/mL). This apparent discrepancy highlights the importance of synergistic interactions among bioactive compounds rather than the concentration of a single dominant phenolic compound. Although the highest caffeic acid levels, which is recognized for its strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties48, were present in “Romanesco”, synergistic effects of multiple compounds like rutin, sinapic acid, and rosmarinic acid presented in “Strunjanska articoka” showed better in vitro results. These findings are supported by the previous reports demonstrating the role of phenolics in reducing intracellular ROS. Recently, it has been shown that aqueous leaf extracts of C. sylvestris exhibit multiple mechanisms of action in counteracting oxidative stress induced by free fatty acids49. Specifically, at a concentration of 50 µg/mL, these extracts were found to increase reduced sulfhydryl levels, reduce ROS production, and inhibit lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, they positively modulated cytoprotective Nrf2/ARE-regulated genes, contributing to a mitigated inflammatory response. In other studies artichoke extracts demonstrated strong cytoprotective effects by removing ROS and protecting cells from H2O2-induced cytotoxicity. This is achieved through two main mechanisms: direct scavenging of free radicals by the artichoke fractions and the enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activity, such as superoxide dismutase and catalase. These enzymes are crucial for neutralizing peroxides that can damage cell structure and function, thus preventing apoptosis50. Accordingly, this suggests that the phenolic compounds identified in our research, along with other bioactive compounds, may similarly offer protection against oxidative stress and inflammation, supporting their potential therapeutic application in managing oxidative damage. Artichoke’s antioxidant properties were also confirmed in other studies that focused on human cells under various induced oxidative stresses. The water leaf extract of the plant has been assayed and referred to possess strong antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties11.

In our study, ALE extract of “Strunjanska articoka” effectively protected primary colon cells, colon cancerous cells, and liver cancer cells from induced oxidative stress. On the other hand, “Romanesco” and “Violetto di Romagna” ALEs exerted a protective effect only in cancerous cells (“Violetto di Romagna” in Caco-2 cells, while “Romanesco” in both Caco-2 and HepG2 cells). In addition, it can be pointed out that “Strunjanska articoka” and “Romanesco” ALEs were toxic to tumor Caco-2 and HepG2 cells at a lower concentration (both at a 0.125% (v/v) concentration) than in primary colon cells (0.250% (v/v) concentration), which is an additional benefit, but for any claims about antitumorigenic effects, further studies should be performed. This could be attributed to the synergistic action of rutin (263.37 mg/g in “Strunjanska articoka”), sinapic acid (2.42 mg/g), and other phenolic compounds, as was stressed out previously, which have well-established antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. These compounds may help to protect living cells against oxidative stress more effectively through additional mechanisms such as modulation of antioxidant enzymes, rather than only by direct radical scavenging activity51.

In addition to the antioxidant properties, “Strunjanska articoka” and “Violetto di Romagna” ALEs exerted the ability to reduce lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells, while “Romanesco” ALE did not. The observations can be attributed to the differences in chemical composition of the tested extracts. While the phenolic compound profiles of all three artichoke varieties align with findings from previous studies52,53, there were considerable differences in the amounts of individual compounds in each variety. Rutin in “Strunjanska articoka” (263.37 mg/g), significantly exceeding the levels in “Violetto di Romagna” (161.59 mg/g) and “Romanesco” (61.96 mg/g), which may explain its ability to modulate lipid metabolism, thereby contributing to its observed lipid-lowering effects51,54,55. It was shown previously that oleic acid-induced lipid accumulation was reduced in hepatocytes, where they were treated with rutin56. Similar reduction was detected in rutin-treated Caenorhabditis elegans57 and in HepG2 cells treated with Hypericum patulum extract, which also contained rutin58. In contrast, the absence of such activity in the “Romanesco” variety suggests that its rutin concentration (61.96 mg/g) is insufficient to elicit a significant biological response under the tested conditions. In addition to rutin, “Strunjanska articoka” contained higher levels of rosmarinic acid (7.51 mg/g vs. 3.94 mg/g in “Romanesco”). This compound is known to possess hypolipidemic activity59, as it was able to reduce fatty acid synthesis and lipid accumulation, induced by ethanol60. In addition, the role of luteolin derivatives which were present in higher amounts in “Strunjanska articoka” than in “Romanesco” ALE, must also be pointed out, since they are known to induce carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1, a rate limiting enzyme in beta-oxidation61. In addition, sinapic acid was able to reduce lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells62. The observed weak lipid-lowering effect in HepG2 cells suggests that the therapeutic potential of “Romanesco” ALE may be more suited for conditions related to oxidative stress, rather than metabolic disorders (in relation to liver function). On the other hand, “Violeto di Romagna” variety, which contains a combination of caffeic acid derivatives, rutin, and rosmarinic acid, appears to be a versatile option with potential applications in both antioxidant and lipid-lowering therapies.

Several studies have highlighted the significant antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of other polyphenols present in Cynara species, such as chlorogenic acid, dicaffeoylquinic acid, luteolin, and apigenin derivatives49. In addition, various artichoke extracts have been shown to effectively prevent oxidative stress in H2O2-induced HepG2 cells50. Research further emphasizes that the choice of solvent in the extraction process can influence the bioactive compound profile, thereby affecting the biological activity of the extracts, but the objective of this study was focused only on comparing different varieties using the same extraction approach. Since the traditional medicinal uses of the artichoke pertain to liver function, as its leaf extracts are considered choleretic, hepatoprotective, cholesterol-lowering, and diuretic agents63, the lipid-lowering properties of the extract prepared from the leaves of “Strunjanska articoka” are a further benefit.

However, this study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, all artichoke samples were collected from a single geographic location, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Environmental factors such as soil composition, climate, and cultivation practices can significantly influence the phytochemical profile of plants, and future studies should aim to include samples from multiple regions. Second, the characterization of secondary metabolites was based on LC-DAD analysis using a limited set of reference standards, and several compounds were only tentatively identified based on chemical class similarity. More definitive identification through LC-MS or NMR is recommended in future work. Third, although hot water extracts are widely recognized for their negligible caloric value and minimal content of macronutrients such as fats, proteins, and sugars, nutrient composition was not assessed in this study, which limits the completeness of the chemical profile. Finally, the bioactivity assays were limited to in vitro models, which do not fully replicate the complexity of physiological conditions. In particular, it is important to note that when extracts are ingested, they come into direct contact with colon cells in their original form, whereas the profile that affects liver cells will depend on the absorption and metabolism of individual compounds. Therefore, further validation in more advanced models, including animal or clinical studies, is needed to confirm the biological relevance of these findings. However, the in vitro conditions applied in this study follow standard protocols commonly used in phytochemical and nutritional research to evaluate antioxidant activity and related bioactivities. Although these models cannot fully reproduce the complexity of in vivo metabolism, they provide a controlled, reproducible, and cost-effective approach for preliminary screening. Such conditions allow direct comparison between different plant varieties while minimizing biological variability and confounding factors. Importantly, these assays are widely recognized as an appropriate first step for identifying promising candidates and generating mechanistic insights before proceeding to more complex in vivo systems.

Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive comparative analysis of the Slovenian artichoke landrace “Strunjanska articoka” against two widely cultivated Italian varieties, “Violetto di Romagna” and “Romanesco.” The genetic and morphological data gathered are crucial for the landrace’s official registration in Slovenia and contribute to the preservation of this local variety. Significantly, “Strunjanska articoka” exhibited higher concentrations of bioactive compounds, such as rutin, rosmarinic acid, and luteolin derivatives, which are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hypolipidemic properties. Biological assays demonstrated superior antioxidative effects of “Strunjanska articoka” leaf extracts, especially in protecting primary colon cells (CCD112CoN), when compared to the other varieties. While “Romanesco” ALE showed the highest radical scavenging activity, its effectiveness in cellular protection was limited, emphasizing the importance of synergistic interactions among phenolic compounds and involvement of additional antioxidant mechanisms in living organisms. Additionally, “Strunjanska articoka” and “Violetto di Romagna” ALEs exhibited lipid-lowering activity in HepG2 liver cells, unlike “Romanesco,” which lacked this effect probably due to its lower rutin content and less favorable phytochemical profile for lipid metabolism modulation. The results justify further investigation into the potential therapeutic effects of “Strunjanska articoka” in addressing oxidative stress and metabolic disorders. Furthermore, these findings support its cultivation as a promising option for both culinary and medicinal purposes, which could revitalize local agricultural practices and enhance the economic value of this unique Mediterranean plant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Zala Jenko Pražnikar, upon reasonable request.

References

Pecaut, P. 50 - Globe artichoke: Cynara scolymus L. in Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops (eds Kalloo, G. & Bergh, B. O.) 737–746 (Pergamon, Amsterdam, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-040826-2.50054-0. (1993).

Rau, D. et al. The population structure of a Globe artichoke worldwide Collection, as revealed by molecular and phenotypic analyzes. Frontiers Plant. Science 13, (2022).

Lattanzio, V. Composizione, valore nutritivo e terapeutico Del Carciofo. Informatore Agrario. 38, 18727–18731 (1982).

Orlovskaya, T. V. & Luneva, I. L. Chelombit’ko, V. A. Chemical composition of Cynara scolymus leaves. Chem. Nat. Compd. 43, 239–240 (2007).

Bonomi, A. & Bonomi, B. M. L’impiego Della Farina Di Foglie Di Carciofo Disidratate (cinanara scolymus l.)nell’alimentazione dei Vitelloni. In: La Rivista Di Scienza Dell’alimentazione. 30, 361–370 (2001).

Ben Salem, M. et al. Pharmacological studies of artichoke leaf extract and their health benefits. Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 70, 441–453 (2015).

Lattanzio, V., Kroon, P. A., Linsalata, V. & Cardinali, A. Globe artichoke: A functional food and source of nutraceutical ingredients. J. Funct. Foods. 1, 131–144 (2009).

Adzet, T., Camarasa, J. & Laguna, J. C. Hepatoprotective activity of polyphenolic compounds from Cynara scolymus against CCl4 toxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Nat. Prod. 50, 612–617 (1987).

Shallan, M. A., Ali, M. A., Meshrf, W. A. & Marrez, D. A. In vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of Globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. Scolymus L.) bracts and receptacles ethanolic extract. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 29, 101774 (2020).

Sokkar, H. H., Dena, A., Mahana, A. S., Badr, A. & N. A. & Artichoke extracts in cancer therapy: do the extraction conditions affect the anticancer activity? Future J. Pharm. Sci. 6, 78 (2020).

Jiménez-Escrig, A., Dragsted, L. O., Daneshvar, B., Pulido, R. & Saura-Calixto, F. In vitro antioxidant activities of edible artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) and effect on biomarkers of antioxidants in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 5540–5545 (2003).

Brown, J. E. & Rice-Evans, C. A. Luteolin-rich artichoke extract protects low density lipoprotein from oxidation in vitro. Free Radic Res. 29, 247–255 (1998).

FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Crops and livestock products - Artichokes https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2022).

Mauro, R. et al. Genetic diversity of Globe artichoke landraces from Sicilian small-holdings: implications for evolution and domestication of the species. Conserv. Genet. 10, 431–440 (2009).

Pandino, G., Lombardo, S. & Mauromicale, G. Chemical and morphological characteristics of new clones and commercial varieties of Globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus). Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 66, 291–297 (2011).

Pagnotta, M. A., Fernández, J. A., Sonnante, G. & Egea-Gilabert, C. Genetic diversity and accession structure in European Cynara cardunculus collections. PLoS One. 12, e0178770 (2017).

Pignone, D. & Sonnante, G. Wild artichokes of South italy: did the story begin here? Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 51, 577–580 (2004).

Gatto, A., De Paola, D., Bagnoli, F., Vendramin, G. G. & Sonnante, G. Population structure of Cynara cardunculus complex and the origin of the conspecific crops artichoke and cardoon. Ann. Bot. 112, 855–865 (2013).

Pagnotta, M. A. & Noorani, A. Genetic diversity assessment in European Cynara collections. in Genomics of Plant Genetic Resources: Volume 1. Managing, Sequencing and Mining Genetic Resources (eds Tuberosa, R., Graner, A. & Frison, E.) 559–584 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7572-5_23. (2014).

Pedrali, D., Zuccolo, M., Giupponi, L., Sala, S. & Giorgi, A. Characterization and future Distribution prospects of ‘Carciofo Di malegno’ landrace for its in situ conservation. Plants (Basel). 13, 680 (2024).

Klemenčič, I. Strunjanska artičoka je avtohtona rastlina. Nedeljski dnevnik (2019).

Kerma, S. et al. Možnosti nadaljnjega razvoja vinskega in gastronomskega turizma na kmetijah: zaključno poročilo. 219 str. https://repozitorij.upr.si/IzpisGradiva.php?lang=slv&id=20053 (2023).

Sakelšak, M. Univerza na Primorskem, Fakulteta za matematiko, naravoslovje in informacijske tehnologije,. Optimizacija vzorčenja listov artičoke (Cynara cardunculus L.) za izolacijo kakovostne DNA: zaključna naloga. (2018).

Lombardo, S., Pandino, G., Mauro, R. & Mauromicale, G. Variation of phenolic content in Globe artichoke in relation to Biological, technical and environmental factors. Italian J. Agron. 4, 181–190 (2009).

Soares Mateus, A. R. et al. By-products of dates, cherries, plums and artichokes: A source of valuable bioactive compounds. Trends Food Science Technology. 131, 220–243 (2023).

Fratianni, F., Tucci, M., Palma, M., Pepe, R. & Nazzaro, F. Polyphenolic composition in different parts of some cultivars of Globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L. var. Scolymus (L.) Fiori). Food Chem. 104, 1282–1286 (2007).

Lombardo, S. et al. Influence of genotype, harvest time and plant part on polyphenolic composition of Globe artichoke [Cynara cardunculus L. var. Scolymus (L.) Fiori]. Food Chem. 119, 1175–1181 (2010).

Negro, D. et al. Polyphenol compounds in artichoke plant tissues and varieties. J. Food Sci. 77, C244–C252 (2012).

Pandino, G., Lombardo, S., Mauromicale, G. & Williamson, G. Phenolic acids and flavonoids in leaf and floral stem of cultivated and wild Cynara cardunculus L. genotypes. Food Chem. 126, 417–422 (2011).

Rogstad, S. H. Saturated NaCI-CTAB solution as a means of field preservation of leaves for DNA analyses. TAXON 41, 701–708 (1992).

Japelaghi, R. H., Haddad, R. & Garoosi, G. A. Rapid and efficient isolation of high quality nucleic acids from plant tissues rich in polyphenols and polysaccharides. Mol. Biotechnol. 49, 129–137 (2011).

Baruca Arbeiter, A., Hladnik, M., Jakše, J. & Bandelj, D. First set of microsatellite markers for immortelle (Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don): A step towards the selection of the most promising genotypes for cultivation. Ind. Crops Prod. 162, 113298 (2021).

Scaglione, D. et al. Ontology and diversity of transcript-associated microsatellites mined from a Globe artichoke EST database. BMC Genom. 10, 454 (2009).

Acquadro, A. et al. Genetic mapping and annotation of genomic microsatellites isolated from Globe artichoke. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 1573–1587 (2009).

Schuelke, M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 233–234 (2000).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539 (2012).

Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). European Union Herbal Monograph on Cynara Cardunculus L. (Syn. Cynara Scolymus L.), Folium. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-monograph/final-european-union-herbal-monograph-cynara-cardunculus-l-syn-cynara-scolymus-l-folium_en.pdf (2018).

Matić, M. et al. Eco-Friendly extraction: A green approach to maximizing bioactive extraction from pumpkin (Curcubita moschata L). Food Chemistry: X. 22, 101290 (2024).

Mišan, A. Č. et al. Development of a rapid resolution HPLC method for the separation and determination of 17 phenolic compounds in crude plant extracts. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 9, 133–142 (2011).

El Senousy, A. S., Farag, M. A., Al-Mahdy, D. A. & Wessjohann, L. A. Developmental changes in leaf phenolics composition from three artichoke cvs. (Cynara scolymus) as determined via UHPLC–MS and chemometrics. Phytochemistry 108, 67–76 (2014).

Pagano, I. et al. Chemical profile and cellular antioxidant activity of artichoke by-products. Food Funct. 7, 4841–4850 (2016).

Žegura, B., Dobnik, D., Niderl, M. H. & Filipič, M. Antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extracts in Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and HepG2 cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 32, 296–305 (2011).

Pagnotta, M. A. Artichoke: an uncivilized crop rich of diversity to be preserved and valorized. Acta Hortic. 243–256. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1147.35 (2016).

Crinò, P., Pagnotta, M. A. & Phenotyping Genotyping, and selections within Italian local landraces of Romanesco Globe artichoke. Diversity 9, 14 (2017).

Alicandri, E. et al. Morphological, Molecular, and nutritional characterisation of the Globe artichoke landrace Carciofo Ortano. Plants 12, 1844 (2023).

Rouphael, Y. et al. Phenolic compounds and sesquiterpene lactones profile in leaves of nineteen artichoke cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 8540–8548 (2016).

Feiden, T., Valduga, E., Zeni, J. & Steffens, J. Bioactive compounds from artichoke and application potential. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 61, 312–327 (2023).

Spagnol, C. M. et al. In vitro methods to determine the antioxidant activity of caffeic acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 219, 358–366 (2019).

Acquaviva, R. et al. Wild artichoke (Cynara cardunculus subsp. sylvestris, Asteraceae) leaf extract: phenolic profile and oxidative stress inhibitory effects on HepG2 cells. Molecules 28, 2475 (2023).

Yang, M. et al. Phenolic constituents, antioxidant and cytoprotective activities of crude extract and fractions from cultivated artichoke inflorescence. Ind. Crops Prod. 143, 111433 (2020).

Bazyar, H., Moradi, L., Zaman, F. & Zare Javid, A. The effects of Rutin flavonoid supplement on glycemic status, lipid profile, atherogenic index of plasma, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), some serum inflammatory, and oxidative stress factors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 37, 271–284 (2023).

Chileh-Chelh, T. et al. Bioactive compounds and bioactivity of the heads of wild artichokes. Food Bioscience. 59, 104134 (2024).

Abu-Reidah, I. M., Arráez-Román, D. & Segura-Carretero, A. Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Extensive characterisation of bioactive phenolic constituents from Globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) by HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS. Food Chem. 141, 2269–2277 (2013).

Pandey, P., Khan, F., Qari, H. A. & Oves, M. Rutin (Bioflavonoid) as cell signaling pathway modulator: prospects in treatment and chemoprevention. Pharmaceuticals 14, 1069 (2021).

Rahmani, S., Naraki, K., Roohbakhsh, A., Hayes, A. W. & Karimi, G. The protective effects of Rutin on the liver, kidneys, and heart by counteracting organ toxicity caused by synthetic and natural compounds. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 39–56 (2022).

Wu, C. et al. Rutin inhibits oleic acid induced lipid accumulation via reducing lipogenesis and oxidative stress in hepatocarcinoma cells. Journal Food Science 76, (2011).

Qin, X., Wang, W. & Chu, W. Antioxidant and reducing lipid accumulation effects of rutin in Caenorhabditis elegans. BioFactors 47, 686–693 (2021).

Duan, J. et al. Flavonoids from Hypericum patulum enhance glucose consumption and attenuate lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. J Food Biochem 45, (2021).

Nyandwi, J. B. et al. Rosmarinic acid exhibits a lipid-Lowering effect by modulating the expression of reverse cholesterol transporters and lipid metabolism in High-Fat Diet-Fed mice. Biomolecules 11, 1470 (2021).

Guo, C. et al. Rosmarinic acid alleviates ethanol-induced lipid accumulation by repressing fatty acid biosynthesis. Food Funct. 11, 2094–2106 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Reduction of lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells by Luteolin is associated with activation of AMPK and mitigation of oxidative stress. Phytother. Res. 25, 588–596 (2011).

John, C. & Arockiasamy, S. Sinapic acid prevents adipogenesis by regulating transcription factors and exerts an anti-ROS effect by modifying the intracellular anti-oxidant system in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Iranian J. Basic. Med. Sciences 25, (2022).

Kirchhoff, R. et al. Increase in choleresis by means of artichoke extract. Phytomedicine 1, 107–115 (1994).

Funding

This research was conducted as part of a bilateral project between Serbia and Slovenia (2023–2025); the study was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200222) and by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (BI-RS/23-25-039 and research program P1-0386). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K.: Writing – original draft preparation, review and editing, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology. A.B.A.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Software, Visualization. A.S.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Validation, Software, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources. A.P.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. D.B.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision. P.G.: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. N.T.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Validation. S.K.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. A.M.: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Validation, Software, Supervision. Z.J.P.: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft preparation, review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kramberger, K., Baruca Arbeiter, A., Petelin, A. et al. Polyphenolic composition, genetic profile and in vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of artichoke varieties “Strunjanska articoka”, “Romanesco” and "Violetto di Romagna". Sci Rep 15, 42347 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26443-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26443-w