Abstract

Informal caregivers (ICs) frequently face stressful events and have many caregiving responsibilities. Further, they have their basic requirements and continuously face comprehensive care needs (CCN) and unmet needs (UNs) in addition to meeting the needs of patients with cancer. This study aimed to describe the CCNs among the ICs of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care at the Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama, Sri Lanka. This cross-sectional study incorporated 422 ICs using a convenient sampling technique; an interviewer-administered questionnaire collected information on socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. A 35-item validated Comprehensive Needs Assessment Tool (CNAT-ICs) was used to assess the unmet CCNs (UCCNs) of seven domains. A five-point Likert scale was used (1 = no need to 5 = high need) for scoring (possible range 35–175). Higher scores indicated higher UNs. Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Of the sample, 51.4% were female. The mean (± SD) age of the ICs was 43.13 (± 14.92) years. ICs’ mean (± SD) total UCCNs was 92.54 ± 29.48. ICs had the most need in the healthcare staff/nurses’ support needs and information domain (26.20 ± 10.44), followed by social and family support (17.07 ± 7.27), psychological (15.52 ± 7.99), hospital facilities/ service (13.22 ± 5.34), medical officers’ support (9.46 ± 4.14), spiritual/Religious support (5.89 ± 2.80), and physical/practical (5.11 ± 2.29), respectively. Several variables of ICs, such as working status, financial and emotional strain, care levels, self-reported general health, and perceived social and family/friends support, were reported as significant factors. These ICs reported relatively lower overall UCCNs, while the study showed the UNs of ICs were high in the healthcare staff/nurses’ support and information, and essential to consider associated caregiver and caregiving-related variables to minimize UCCNs. The results would help the health authorities understand the current status of UCCNs among ICs from different socio-economic backgrounds in Sri Lanka, recommending future support and involvement with family members in patient care, and especially providing information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the twenty-first century, cancer is a significant social, health, and financial issue since it accounts for about one in six deaths and one in four deaths globally from non-communicable diseases (NCDs)1. Sri Lanka is experiencing the same trend in cancer2. Due to the advanced stages of different cancers, the need for supportive care and patient demand has increased globally3. Hence, palliative care (PC) should be started as soon as possible for better outcomes, confirmed its effectiveness in handling psychological issues, relieving suffering, improving quality of life (QoL) and survival for patients with advanced cancer, also for their family members as defined in “concept of palliative care ” by WHO4,5. Patients with advanced cancer have many PC needs along their disease trajectory in addition to the needs of their families/caregivers6.

Caregivers are formal or informal, anyone who provides care or an individual who helps with physical and psychological care for a person in need (taking care of themselves). Family members, spouses/partners, relatives/blood relatives, relatives-in-law, very close friends, or neighbors are often referred to as informal caregivers (ICs)7, who engage in activities of daily living and instrumental activities8,9. Studies reported that ICs who do not have any formal or professional training encounter numerous issues, such as physical, psycho-social, economic, spiritual, etc.10,11. In addition, ICs have to face day-to-day family chores and many problems of family members, work settings, hospitals, and society12,13. Thus, ICs do not have much awareness about their comprehensive care needs (CCNs) or the way of fulfilling them adequately and are concerned only about meeting of needs of their patient9,12,14. When encountering serious illnesses, meeting ‘needs’ may become challenging for both patients and caregivers and far more demanding15.

The role of ICs is multi-faceted, as mentioned earlier and must care for the majority of the medical, physical, practical, spiritual, financial, and emotional needs of the care recipient; ICs frequently face multiple stressful events, engage in different activities, and hold caring responsibilities3. Some caregivers are at greater risk of having different types of unmet needs (UNs). Many studies have been conducted to identify the unmet supportive care needs of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in different countries16,17,18, and to investigate UNs and/or unmet CCNs (UCCNs)8,19,20. Different UCCNs have been elaborated domain-wise, such as needs in physical, psychological, social, spiritual, informational, etc., and needs could be varied context-wise21. As reported, caregivers of patients with cancer have extensive UNs of information and healthcare (HC), emotional, psychological, medical, and financial needs8,22,23,24.

Further, ‘needs’ could be different due to diverse reasons and the impact of many associated factors. As reported in literature, women, young people, and non-spouse/partner caregivers in metastatic cancer, palliative care, and caregivers of younger patients have more UNs in supportive care25,26,27, in addition to age, gender, education of caregivers, and cancer stage, cancer type, etc., of cancer patients. Furthermore, employment, financial/government support/cancer care services, social life, information, practical support, HC staff/professional support, emotional and psychological problems, spiritual, skill training, ICs’ characteristics, etc.3,8,9,12,17,18,28,29. Due to UCCNs, the QoL of ICs has been impacted14,30, and different psychological effects among family caregivers (FCs), such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, psychological distress/burden, etc., were reported13,14,31,32,33.

Similar to cancer patients, ICs also have the same “basic needs,” predominantly, while fulfilling the needs of cancer patients, increased caregiving responsibilities may subsequently increase the needs of caregivers. Compared to studies done on UCCNs among caregivers in other countries, published findings were very limited in Sri Lanka; none of the studies were done to find UCCNs among adult cancer caregivers, according to the literature up to date. Thus, this study could be the very first finding which done to assess UCCNs among informal cancer caregivers in Sri Lanka using a valid and reliable scale which developed to measure the needs of ICs23,34,35.

Therefore, the identification of the current UCCNs of ICs was very important to provide better quality care for respective patients, enhance the QoL of patients and ICs, and support the concept of PC. Hence, this study aimed to describe the perceived UCCNs of ICs of patients with advanced cancer in PC at the Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama (AHM), Sri Lanka.

Methods

Design and sample

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted at the PC unit, oncology, and/or oncosurgery clinics in the AHM, Western Province, Sri Lanka, from February to May 2024. This is the main/primary oncology facility in Sri Lanka, managed by the Sri Lankan government, offering all curative and preventive services free of charge to paediatric and adult patients with cancer. It consists of an outpatient department, all general and special clinics, general wards and special wards, and different units for all patients, with more than 800 beds.

Participants were ICs who provided PC in the cancer wards at AHM for patients diagnosed with any type of advanced cancer, admitted before this data collection, and who stayed with patients with advanced cancer. Additionally, “spouses, blood relatives, and relatives-in-law” classified as FCs were considered ICs7, along with close friends and neighbors. The sample of ICs (n = 422) was conveniently selected based on several inclusion and exclusion criteria, including being 18 years or older36, having a good understanding of Sinhala or English, caring for patients with advanced cancer for more than three months with the available knowledge and practice36, and being in good physical and mental health. Adult ICs who provided care for patients with critical conditions resulting from advanced cancer or other co-morbidities, who had training in caring for patients, who had worked or been paid for such care, or who had a history of mental illnesses diagnosed by psychiatrists were excluded.

Data collection and tools

The data were collected using a validated interviewer-administered questionnaire (IAQ). It included clinical features of both ICs and care recipients, along with socio-demographic information. The UCCNs of ICs were evaluated with the validated 35-item Sinhala version of the Comprehensive Needs Assessment Tool for cancer caregivers (S-CNAT-ICs)30, originally developed in South Korea21. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.903 for the overall S-CNAT-ICs, and the test-retest reliability was 0.96523.

Newly identified seven domains were renamed as follows: healthcare staff/nurses’ support and information (HNIN-8 items), physical/practical needs (PPN-3 items), medical officers’ support (MON-3 items), psychological needs (PSN-7 items), social/family support (SFN-6 items), spiritual/religious support (SRN-2 items), and hospital facilities/service (HSN-6 items). The scoring system was adjusted, and a five-point Likert scale was created accordingly (1 = not required, 2 = satisfied, 3 = need is minimal, 4 = need is moderate, and 5 = need is high). Scores range from 35 to 175, with higher scores indicating more/higher UNs [cut-off point-105]. Domains were calculated by averaging the score for each domain with subsequent linear transformation to a scale of 0–100 following the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) scoring guideline21,37.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 25.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were used to describe the socio-demographic profile, clinical characteristics, and UCCNs. Independent t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson’s correlation were used to investigate the association between characteristics/variables. The level of significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

This study was performed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, was granted ethical approval (Ref. no ERC 49/22). After reading the information sheet, all participants were asked for informed written consent before the study.

Results

Characteristics of informal caregivers and care recipients

Of the sample, the mean age (± SD) was 43.13 (± 14.92) years (age range 18–80), and 51.4% of ICs were female. The majority were married, educated up to grade 6–12, and other findings are depicted in Table 1 (response rate was 100%). No change of the current occupation was reported by many ICs (63.7%), and 25.4% of ICs (n = 107) had to work fewer working hours in the job than before the diagnosis. Further, 3.8% of ICs (n = 16) had to discontinue their higher education due to caregiving. Most ICs had not suffered from chronic medical, surgical, and psychological conditions, and 73.2% did not report any physical illnesses due to caregiving.

Care recipients (n = 280; 66.4%) lived with their family members or as extended families. These cancer patients’ age ranged from 18 to 87 years old, with a mean age of 57.90 (± 12.22) years, and 44.1% of the patients were in the 50–65 age category. Of the sample, 70.4% of the patients were female, and breast cancer (n = 100, 23.7%) was the most prominent cancer.

Unmet comprehensive care needs (UCCNs) among ICs

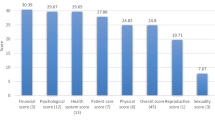

The total mean score of UCCNs among the current ICs was 92.54 ± 29.48 (Table 2), which was lower than the general mean score of the scale (105). The prevalence of total UCCN ranged from 28% to 84%. The domain with the highest UCCNs mean score was “Healthcare staff/Nurses’ support needs and Information Needs (1st top need),” followed by “Social and Family support Needs (2nd top need),” and “Psychological Needs (3rd top need)”. Further, reported percentages of UCCNs of seven domains (e.g., low, moderate, high, and total) and the total UCCN percentage are illustrated in Table 2.

Considering the total percentages of unmet needs domains (UNDs), a higher percentage was scored by the SRN domain, followed by the HNIN and MON domains, which are different from the categorization according to the mean scores.

Although the SRN domain obtained the highest total percentage of UNDs (Table 2), a higher number of UCCN items were represented by the HNIN domain: 8 out of 10 items (Table 3) ranked based on the obtained mean scores. Among all domains, the PSN domain ranked the lowest percentage for total UCCNs (28%). A higher percentage of ICs reported “none or satisfied” for several domains, such as PSN, HSN, and PPN domains, indicating that such needs were met by ICs satisfactorily. Among low, moderate, and high UCCN categories, a ‘high’ UCCN percentage was reported by HNIN, MON, SRN, and SFN (Table 2).

Supplementary Table 1 depicts the further details of the 35-item-S-CNAT-ICs (Descriptive statistics of different CCNs among ICs). Also, it shows the top rankings of needs in each domain by ICs according to their mean ± SD score. The highest UCCN mean score was obtained by “economic burden caused by cancer (e.g., treatment costs, loss of income)” (rank 1-3.78 ± 1.23) followed by “sincere interest and empathy from the nurse” (rank 2-3.75 ± 1.07), and “to be actively involved in the decision-making process in choosing test or treatment that the patient may receive” (rank 3-3.74 ± 1.08) (HNIN domain). Many items of the first factor/HNIN had higher levels of mean need scores than other items. “Space reserved for caregivers” (rank 35) obtained the lowest mean need score.

Factors associated with UCCNs among ICs

Fewer variables were significantly associated with UCCNs of ICs, as depicted in Table 4, such as working status, financial and emotional strain, care levels, SGH, PSS, and PFFS. Age showed a negative and significant correlation with total UCCNs; relatively, younger ICs (18–55 years) reported higher UNs than older ICs for all UNDs.

Although gender had no significant effect on USSNs, male ICs had higher mean UNs than female ICs for most of the UNDs. Furthermore, marital status, education, and income had no significant influence on UCCNs; however, ICs who had divorced/separated, were illiterate, and earned a lower income reported comparatively higher UNs for most UNDs. Educational disruption due to caregiving also increased UNDs. Being employed and changes in the employment of ICs caused the higher UNs. ICs who lived with their patients mostly reported higher UNs than those of others, and no significant impact on UCCNs.

A very close relationship with patients led to higher UNs among ICs; patients who were looking after their family members experienced greater amounts of UNs compared to carers (e.g., negihbours or relatives) who did not live in the same residence or patients who lived in the same household.

Poor PSS and no FFS caused higher UNs. Longer duration since the diagnosis reported the higher UNs. Higher caring hours among ICs were prone to higher UNs, whereas lower sleeping hours caused higher UNs. Further, all UNDs in Table 5 were significantly and positively associated with total UCCNs except the PPN domain.

The gender of the patient with cancer had no significant impact on total UCCNs of ICs; however, male gender increased the higher UNs (male vs. female patients- 93.45 ± 23.65 vs. 92.26 ± 31.39). Also, age and the cancer type of the patient were not significantly influenced on ICs’ UNs. Though the younger age of the patients resulted in higher UCCNs among ICs (younger vs. older: 95.90 ± 31.81 vs. 86.93 ± 30.73).

Discussion

This study is among the first to comprehensively assess UNs among ICs in the field of cancer PC in Sri Lanka. The findings of this study demonstrate that the overall UCCNs among ICs of patients with advanced cancer in this study were relatively low (total mean score was 92.54 out of 175), However, this contrasts with higher UNs levels reported in other countries such as Iran and Singapore12,20,28,38, likely reflecting the dual burden of managing patient and personal needs. While some caregiver and caregiving-related variables were associated with UCCNs, the number of significant associations was lower than expected, as elaborated in other countries12,20,28,39. Nonetheless, most caregivers reported UNs across all seven domains assessed. Prior studies have found that family caregivers (FCs) may even report greater needs than the patients themselves28, suggesting the burden on caregivers may be under-recognized in Sri Lanka, in addition to lower QoL, etc.39. Male gender and young age of the patients in the current study also caused the higher UNs among ICs, in contrast to other countries8,20,29,39, while no significant impact of cancer types was observed among patients with cancer20. Most of the male and younger patients depended on their female and adult caregivers when they had to face ill-being conditions.

This study evaluated multiple UN domains, including information, support from healthcare staff (HCS), hospital services, spiritual/religious needs, practical and physical support, financial, emotional, and psychological needs, similar to international studies12,17,27,28,40. Some studies have assessed these needs individually, such as emotional-spiritual concerns24,41, information29,38, or supportive care18,22,25. Variations in tools used to assess needs may explain differences in findings across studies. In this study, the questionnaire was culturally adapted and validated, ensuring relevance to the local context[23].

In terms of mean scores, the highest UNs were in the Healthcare staff/Nurses’ support needs and information (HNIN) domain, followed by Social and family support (SFN), Psychological (PSN), Hospital facilities/services (HSN), Medical officers’ support (MON), Spiritual/Religious support (SRN) and Physical/practical (PPN) domain. The need for information is well-reported in the literature. Most HNIN items scored high, emphasizing the critical role of nurses and HCS in providing information and support. In addition, most items in the HNIN domain exhibited higher mean scores, indicating that the HNIN items were more important than other items, which were the most UNs. This domain encompassed a broad range of needs, such as guidance on disease, treatment, symptom management, and end-of-life care, aligning with international findings12,25,27,28,42. ICs highly value accurate and timely information, especially those balancing employment and caregiving, as a lack of clarity increases emotional stress. Many studies treat HCS support and information as separate domains28,39,43, allowing more detailed assessment. In this study, both were integrated into the HNIN domain. Evidence from Iran and South Korea20,39 also highlights educational and informational needs as top priorities for caregivers. Oncology and PC professionals play a central role in delivering this support, underscoring the importance of training and empowering HC teams to meet the needs of caregivers. Some ICs who are currently engaged in their jobs have to do caring activities simultaneously. Thus, working status and level of care (day-to-day vs. intermittent) among ICs were significantly impacted on UCCNs in this study; such caregivers always have to depend on HCS and accurate information. Otherwise, they have to suffer emotional strain could increase the overall UNs. Altogether, the HCS and nurses provide a wide range of information about cancer, treatment methods, care, different symptom management, and other medical and support facilities for ICs from disease trajectory to end-of-life, even in the bereavement period29.

In some studies, HCS was the second top domain of UCCNs20,28, while this study revealed that social and family support needs (SFN) were the 2nd top domain of UCCNs, similar to previous findings12, highlighting the importance of social, family, relational, and communication needs. However, the family/social support domain placed sixth in Singapore’s ICs28. Financial strain and limited family assistance were major contributors. About 79% of ICs reported financial difficulties due to cancer and past economic hardships in Sri Lanka, which were well explained elsewhere12,44,45,46, and 46% were unemployed. Although 64% reported no change in employment due to caregiving, many experienced disruptions such as loss of jobs, increased/decreased working hours, unpaid leave, lower pay jobs, work from home, discontinuing higher education, being busy with caring, and reduced sleeping hours of ICs44,45,46,47. These changes increase stress and reduce perceived SS and FFS. Financial information is crucial for caregivers, and some items scored very high mean values that could increase the UCCN levels among different domains12,20,28.

In Sri Lanka, changes in family structure, from extended to nuclear, include fewer members, which increases financial burdens and caregiver costs, and may limit traditional sources of support. Comparisons with high-income countries (e.g., America, Australia, Germany, England, etc.) show fewer economic burdens due to stronger HC and social protection/insurance systems47. Sri Lanka is a developing country where government investment in public hospitals is insufficient. In contrast, Sri Lankan ICs often incur high out-of-pocket expenses despite free public HC. Costs for transport, meals, private medications, and treatments continue to pose challenges. Internationally, legal protections, allowances, and caregiver grants exist12, but such policies remain limited in Sri Lanka.

The PSN domain ranked third. Many ICs reported satisfaction with psychological well-being, though emotional distress, burden, anxiety, and fear were still evident, especially among those experiencing financial strain or low SS and FFS. However, most ICs reported satisfaction with their psychological well-being, reported the top UN22, and the least place for FCs12. Patients with severe illnesses and low physical activity require more time and effort, causing psychological distress and morbidity and damaging the mental well-being of ICs48. In Sri Lanka, cultural and spiritual coping strategies may cause lower self-reported psychological distress. Nevertheless, emotional and financial pressures significantly contributed to increased UCCNs, even among ICs who reported “good health.” Unlike some studies that combine health and psychological needs20,21,28, this study assessed psychological needs independently, leading to a more focused evaluation. However, most other studies reported both health and psychological problems20,21,28 in one domain. Many ICs rated “no need or satisfied” for the PSN domain, similar to elsewhere20 and contrasting with the findings from Singapore28.

This study further assessed the four other domains of the ICs of patients with advanced cancer; the HSN domain had a considerably higher mean score than the other domains, ranked fourth in the current study, similar to Chua et al.28, but different from Asharafian et al.20, where it was in seventh place; and reported the fulfillment of that need than in the current study and provision of better hospital facilities/services. While Sri Lanka’s public HC system provides free services, transportation issues and limited hospital infrastructure still affect caregiver experiences. Many ICs preferred nearby HC centers to minimize costs and burden. Transport challenges led to delayed or missed appointments28, especially for those from rural areas or with limited financial supports 12. Though some government/private transport options are available from Apeksha Hospital, they are often insufficient. Caregivers sometimes had to use expensive private vehicles due to the patient’s available symptoms28, and ICs face various challenges when using public transportation; thus, traveling can be a significant burden12.

HC authorities often do not fully address transportation needs or provide sufficient financial assistance programs28,49. PC centers are not evenly distributed across Sri Lanka, requiring long-distance travel for many families. Furthermore, caregiver-focused facilities (e.g., resting areas, meals, etc.) are limited in public hospital settings, adding to their stress and burden.

The current study ranked the MON domain 5th due to lower mean need scores, which was different from many studies due to not having a separate domain for medical professionals; it included the HCs domain in other studies20,28. This differs from studies where HCS and medical officers were assessed jointly20,28. In the current study, a separate MON domain was established, reflecting caregivers’ desire for clear, direct communication from doctors. Poor communication between formal and informal care providers increased UCCNs, requiring transparent, straightforward, and timely communication. The lower mean score in the SRN domain (6th place) reported may be due to cultural and traditional factors in Sri Lanka, as in previous findings20,28. While Sri Lankan caregivers often rely on religious practices for coping, some UNs were noted. ICs from Buddhist and other religious backgrounds sought spiritual support during the cancer journey, especially in times of crisis or bereavement50,51,52,53,54,55,56. Limited PC services and few social or community-based religious support systems may increase reliance on family or temple-based care. Other studies have noted the importance of spiritual care, especially in culturally religious societies20,28.

Physical/practical needs (PPN) were the least UN domain in this study. Most ICs reported satisfaction in both physical and practical needs areas, though challenges still exist. In contrast, other studies ranked practical support much higher, the fourth20 and third28, and some were considered as daily living/activity needs22,25. In Sri Lanka, ICs required support for personal health concerns and services close to home, with transportation again emerging as a limiting factor. Thus, the lack of transportation support could be a reason for increased UCCNs of PPN in the current study, similar to many ICs20,28. These needs overlap with hospital service concerns and contribute to overall caregiver burden.

In addition to the above-mentioned associated factors, being a young IC had perceived many UCCNs than the older caregivers, as elsewhere28. They may have more competing life goals, such as education, employment, or marriage, which caregiving can disrupt. Male caregivers also reported higher UNs, possibly due to less experience with caregiving tasks traditionally handled by women in many countries, and other household chores28. Additionally, unemployment and low education were linked to increased UNs. These socio-economic factors often increase vulnerability to stress/burden, especially when balancing caregiving responsibilities without adequate resources or knowledge. It is not an unexpected change that the ICs had more UNs in several UNDs, resulting in higher overall UNs, which reported the same scenarios in other countries20,38.

The cumulative impact of unmet caregiver needs can reduce care quality for patients. ICs under strain may struggle to maintain emotional, physical, and practical support, leading to negative outcomes for both patients and ICs54,55,56.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design limited causal interpretations of the results, and conducting the study in a single setting restricted its generalizability. However, gathering responses from island-wide ICs and family members may increase the representativeness to some extent. Furthermore, the use of standardized and validated questionnaire for ICs to measure UNs enhanced the validity of the findings. Therefore, we believe that the outcomes can be generalized. This study was conducted at a specific point in time and does not describe longitudinal trends in needs throughout the disease trajectory. The use of a convenience sampling technique may have introduced sampling bias.

Conclusions

The current study identifies the most common unmet comprehensive care needs in the healthcare staff/nurses’ support needs and information domain as the top concern, followed by social and family support needs, and psychological needs. This study revealed that most caregivers have a variety of UCCNs with relatively low severity levels, and many UCCNs are present across all seven domains with different levels of severity, which underscores the importance of providing adequate support to meet the diverse needs of caregivers. The leading needs items for caregivers relate to financial issues. This study is a pioneering effort in Sri Lanka and is the first of its kind to describe various UNs among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer.

Caregivers should be prioritized to reduce various UCCNs and the burdens they face. Additionally, HCS, especially nurses, need training to recognize caregivers’ met and unmet needs and to respond appropriately. Moreover, providing adequate information by HCS is essential, along with multidisciplinary HC support to deliver quality PC and enhance patient care. Findings from this study suggest the importance of ongoing social and family support for ICs. Extra attention should be given to transportation issues and costs for ICs due to economic hardships, and authorities must develop appropriate strategies to address these UCCNs. It would also be beneficial if future research conducted studies to identify the UCCNs of ICs using qualitative or mixed methods.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript and in the supplementary file.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

National Cancer Control Programme Sri Lanka. National strategic framework for palliative care development in Sri Lanka 2019–2023. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 1689–1699 (2019).

Boele, F. et al. The role, impact, and support of informal caregivers in the delivery of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a multi-country qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 35, 552–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320974925 (2021).

Choi, Y. Y. et al. Enhanced supportive care for advanced cancer patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 21, 338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01097-5 (2022).

Palliative care, WHO. (2020, accessed 10 Nov 2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

Hui, D., Hannon, B. L., Zimmermann, C. & Bruera, E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 356–376. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21490 (2018).

Muthucumarana, M. W. & Samarasinghe, K. Topics in stroke rehabilitation caring for stroke survivors: experiences of family caregivers in Sri Lanka- a qualitative study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 9357, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2018.1481353 (2018).

Wang, T., Molassiotis, A., Chung, B. P. M. & Tan, J. Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care. 17, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9 (2018).

Zhu, S. et al. Care needs of dying patients and their family caregivers in hospice and palliative care in Mainland china: a meta-synthesis of qualitative and quantitative studies. BMJ Open. 11, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051717 (2021).

Kehoe, L. A. et al. Quality of life of caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 969–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15862 (2019).

Lorio, C. M., Romano, M., Woods, J. J. & Brown, J. A review of problem solving and reflection as caregiver coaching strategies in early intervention. Infant Young Child. 33, 35–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000156 (2020).

Niu, A. et al. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs, with concomitant influencing factors, in family caregivers of cancer patients in China. APJON 8, 276–286. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_52_20 (2021).

Van Hof, K. S. et al. Caregiver burden, psychological distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer: a longitudinal study. IJERPH 19(, 16304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316304 (2022).

Chong, E., Crowe, L., Mentor, K., Pandanaboyana, S. & Sharp, L. Systematic review of caregiver burden, unmet needs and quality-of-life among informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 31, 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07468-7 (2023).

Glajchen, M. Family caregivers in palliative care and hospice: minimizing burden and maximizing support (2016). https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PalliativeCare_Family_Caregivers.pdf.

Zhang, M. et al. Supportive care needs and associated factors among caregivers of patients with colorectal cancer: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 27 (3), 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08390-w (2024).

Stiller, A. et al. The supportive care needs of regional and remote cancer caregivers. Curr. Oncol. 28, 3041–3057 (2021).

Nicklin, E. et al. Long-term unmet supportive care needs of teenage and young adult (TYA) childhood brain tumour survivors and their caregivers: a cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 2022, 1981–1992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06618-7 (2022).

Lin, L. et al. Analysis of the comprehensive needs of primary caregivers of hospitalized colorectal cancer patients and characteristics analysis of high comprehensive needs population. Medicine 102 (35), e34887 (2023).

Ashrafian, S., Feizollahzadeh, H., Rahmani, A. & Davoodi, A. The unmet needs of the family caregivers of patients with cancer visiting a referral hospital in Iran. APJON 5, 342–352. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_7_18 (2018).

Shin, D. W. et al. The development of a comprehensive needs assessment tool for cancer-caregivers in patient-caregiver dyads. Psycho-Oncology 20, 13421352. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1857 (2011).

Alnaeem, M. M., Al Qadire, M. & Nashwan, A. J. Unmet needs, burden, and quality of life among family caregivers of patients with advanced hematological malignancy. Psychol. Health Med. 30 (7), 1573–1588 (2025).

Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S. & Meegoda, L. Comprehensive needs assessment tool for informal cancer caregivers (CNAT-ICs): instrument development and cross-sectional validation study. IJNSA 7, 100240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2024.100240 (2024).

Ben-Arye, E. et al. Exploring unmet concerns in home hospice cancer care: perspectives of patients, informal caregivers, palliative care providers, and family physicians. Pall Supp Care. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951524000567 (2024).

Chen, S. C. et al. The unmet supportive care needs-what advanced lung cancer patients’ caregivers need and related factors. Support Care Cancer. 24 (7), 2999–3009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3096-3 (2016).

Lund, L., Ross, L., Petersen, M. A. & Groenvold, M. The interaction between informal cancer caregivers and health care professionals: a survey of caregivers’ experiences of problems and unmet needs. Support Care Cancer. 23 (6), 1719–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2529-0 (2015).

Baudry, A. S. et al. Profiles of caregivers most at risk of having unmet supportive care needs: recommendations for healthcare professionals in oncology. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 43, 101669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.09.010 (2019).

Chua, G. P. et al. Supporting the patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers: what are their palliative care needs? BMC Cancer. 20, 768. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07239-9 (2020).

Lewandowska, A., Rudzki, G., Lewandowski, T. & Rudzki, S. The problems and needs of patients diagnosed with cancer and their caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 87 (2020).

Weeratunga, E. B., Goonewardena, C. S. E. & Meegoda, M. K. D. L. Quality of life among informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care at the Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sexual and Reproductive Health/ReproSex, Sri Lanka:140–141 (2024).

Pan, Y. C. & Lin, Y. S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of depression among caregivers of cancer patients. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 817936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.817936 (2022).

Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S. & Meegoda, L. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer at the Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the iRuFARS. 2024, University of Ruhuna, Matara, Sri Lanka: 33 (2024).

Weeratunga, E. B., Goonewardena, S. & Meegoda, L. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who received palliative care in Sri Lanka. APJCP 26 (6), 1997–2007. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2025.26.6.1997 (2025).

Weeratunga, E. B., Meegoda, M. K. D. L. & Goonewardena, C. S. E. Initial linguistic/cultural adaptation of the comprehensive needs assessment tool for caregivers (CNAT-C) in Sri Lanka: a pilot study. In Proceedings of the 4th Biennial Academic Sessions-Graduate Nurses’ Foundation of Sri Lanka, vol. 27 (2024).

Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S. & Meegoda, L. Validation of the Sinhala version of the comprehensive needs assessment tool (CNAT) for informal cancer caregivers in Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of 21st Academic Sessions and 20th Vice Chancellor’s Awards Ceremony, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences & Technology, University of Ruhuna, Matara, Sri Lanka (2024).

Cai, Y., Simons, A., Toland, S., Zhang, J. & Zheng, K. Informal caregivers’ quality of life and management strategies following the transformation of their cancer caregiving role: a qualitative systematic review. IJNS 8, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.03.006 (2021).

Mazanec, S., Reichlin, D., Gittleman, H. & Daly, B. Perceived needs, preparedness, and emotional distress of male caregivers of postsurgical women with gynecologic cancer. ONF 45, 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.ONF.197-205 (2018).

Wang, T., Mazanec, S. R. & Voss, J. G. Needs of informal caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 48, 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.ONF.11-29 (2021).

Kim, H. & Yi, M. Unmet needs and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients in South Korea. APJION 2, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.158019 (2015).

Aminuddin, F. et al. (ed Ting, S. C. Y.) Cancer impact on lower-income patients in Malaysian public healthcare: an exploration of out-of-pocket expenses, productivity loss, and financial coping strategies. PLoS ONE 19 e0311815 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0311815 (2024).

Perpiñá-Galvañ, J. et al. Level of burden and health-related quality of life in caregivers of palliative care patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234806 (2019).

Ullrich, A. et al. Supportive care needs and service use during palliative care in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 29 (3), 1303–1315 (2021).

Heckel, L. et al. Unmet needs and depression among carers of people newly diagnosed with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 51 (14), 2049–2057 (2015).

Coumoundouros, C., Ould Brahim, L., Lambert, S. D. & McCusker, J. The direct and indirect financial costs of informal cancer care: a scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community: Hsc 2019, 12808. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12808 (2019).

Veenstra, C. M. & Morris, A. M. Understanding longitudinal financial hardship in cancer—how to move the field forward without leaving patients behind? JAMA Netw. Open. 7, e2431905. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.31905 (2024).

Zheng, Z. et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the united States. Cancer 125, 1737–1747. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31913 (2019).

Niu, A. F. et al. Advances in research on supportive services for primary caregivers of patients with chronic diseases. J. Nurs. Manag. 19, 594–598 (2019).

Oechsle, K. et al. Psychological burden in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer at initiation of specialist inpatient palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care. 18, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0469-7 (2019).

Thomson, M. D., Van Houtven, C. H., Xu, R. & Siminoff, L. A. The many costs of transportation: examining what cancer caregivers experience as transportation Obstacles. Cancer Med. 12, 17356–17364. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.6351 (2023).

Weeratunga, E., Senadheera, C., Hettiarachchi, M. & Perera, B. Development and validation of a religious and spiritual support scale in Sri lanka: A psychometric study. I Health Trends Pers. 3, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.32920/ihtp.v3i1.1717 (2023).

Ferrell, B. R., Borneman, T., Koczywas, M. & Galchutt, P. Research synthesis related to oncology family caregiver spirituality in palliative care. J. Palliat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2024.0209 (2024). jpm.2024.0209.

Weeratunga, E. B., Goonewardena, C. S. E. & Meegoda, M. K. D. L. Perceived social support and family/friend support among informal cancer caregivers at the Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of 11th International Conference on Multidisciplinary Approaches/iCMA-2025, Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka (2025).

Weeratunga, E. B., Goonewardena, C. S. E. & Meegoda, M. K. D. L. Different Unmet needs among informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 16th Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Conference 2025 (APHC 2025), Borneo Convention Centre Kuching (BCCK), Sarawak, Malaysia (2025).

54. Weeratunga, E. B., Goonewardena, C. S. E. & Meegoda, M. K. D. L. Exploration of experiences of cancer patient-informal caregiver dyad in palliative care at Apeksha Hospital, Maharagama, Sri Lanka. In Journal of the College of Community Physicians of Sri Lanka (JCCPSL) – Global Public Health Summit (GPHS) 2025 and 30th Annual Academic Sessions, Hilton Residence/Sri Lanka, vol. 31 (August 2025- special issue). https://doi.org/10.4038/jccpsl.v31i5.8864 (2025).

Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S., Meegoda, L. Factors associated with unmet needs of informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care at Apeksha Hospital, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Academic Sessions- College of Palliative Medicine of Sri Lanka, 19-20 September, Galle Face Hotel, Sri Lanka. 61 (2025).

Meegoda, L., Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S. Challenges encountered by informal cancer caregivers in palliative care at Apeksha Hospital, Sri Lanka: A qualitative study. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Academic Sessions- College of Palliative Medicine of Sri Lanka, 19-20 September, Galle Face Hotel, Sri Lanka. 62 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged all participants involved in this study and highly appreciated the trained data collectors involved in the project. They further acknowledged Dr. Sujeewa Weerasinghe (Consultant Oncologist, Apeksha Hospital Maharagama, Sri Lanka), Ms. Samindra Ranasingha (Former In-Charge/Palliative Care Unit, Apeksha Hospital Maharagama, Sri Lanka), Ms. Kalpani (Current In-Charge/Palliative Care Unit, Apeksha Hospital Maharagama, Sri Lanka), and respective nursing staff.

Funding

No funding supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.W. contributed to the study conception, design, analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript drafting. S.G. and L.M. participated in the study conception and manuscript correction. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, was granted ethical approval (Ref. no ERC 49/22).

Informed consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weeratunga, E., Goonewardena, S. & Meegoda, L. Comprehensive care needs among informal cancer caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 42440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26469-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26469-0