Abstract

Wastewater treatment in developing countries remains inadequate due to limited awareness of its environmental and health impacts, coupled with the high costs of available treatment technologies. Therefore, developing cost-effective, accessible, and efficient treatment solutions is crucial for protecting public health and the environment. This study evaluates the chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency of a novel combined pre-treatment process followed by adsorption using Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC), a low-cost and sustainable adsorbent. A laboratory-based study was conducted to optimize COD removal efficiency through sequential pre-treatment steps as screening, sedimentation, and filtration followed by adsorption with NSDAC. The adsorbent was chemically activated using sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and thoroughly characterized to assess its physicochemical properties. Batch adsorption experiments examined the influence of pH, adsorbent dose, contact time, and agitation speed on COD removal efficiency. A central composite design was employed to evaluate process interactions and optimize conditions using Design Expert version 13.0.5.0 software. ANOVA and a quadratic logistic regression model were used to assess the statistical significance of process parameters. The highest COD removal efficiency (90.53%) was achieved at a pH of 6.05, an adsorbent dose of 10.87 g/L, a contact time of 86.94 min, and an agitation speed of 190.31 rpm. When applied to real wastewater, the integrated pre-treatment and NSDAC adsorption system achieved a COD removal efficiency of 97.50%, demonstrating superior performance. Adsorption data best fit the Langmuir isotherm model (R² = 0.9993) and followed pseudo-second-order kinetics (R² = 0.9936), indicating monolayer adsorption and chemisorption as the dominant mechanism. This study highlights the potential of NSDAC as a sustainable alternative to conventional adsorbents, contributing to the development of cost-effective wastewater treatment technologies. Future research should focus on optimizing large-scale applications, assessing the economic feasibility of widespread NSDAC adoption, and investigating its regeneration and reusability to improve long-term sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Addressing global water challenges is one of the foremost issues of the 21 st century1. Effective solutions require a multi-faceted approach, including stricter protection of water sources, the development of low-cost water technologies, novel water treatment methods, and maximizing the recovery of used water2. Among urban water users, the car wash industry is a significant contributor to both high water consumption and the generation of wastewater containing diverse pollutants, including chemical oxygen demand (COD), oils, greases, surfactants, heavy metals, and other toxic compounds3,4.

Car wash wastewater (CWW) is a major environmental concern due to its volume and pollutant load. Car wash facilities, whether automated or manual, typically consume substantial amounts of water, averaging 200 L per wash, with some facilities consuming over 10 cubic meters daily5,6. This wastewater contains complex mixtures of dissolved, suspended, and settleable solids, oils and grease, nutrients such as ammonium, nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate, as well as toxic metals including arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and lead, all of which can negatively impact critical water quality parameters such as pH, turbidity, electrical conductivity, COD, and BOD7.

The environmental impacts of untreated CWW extend beyond water quality. Direct discharge into water bodies threatens aquatic ecosystems, human health, and overall water security8. Heavy metals from engine and brake components further exacerbate pollution, underscoring the need for efficient and sustainable treatment methods.

Globally, the increasing number of vehicles, driven by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and population growth, has escalated water consumption in the car wash industry1. In São Paulo, for instance, the industry uses over 1.3 million gallons of fresh water daily2. Similarly, studies from Mexico, Malaysia, and Australia report significant water use in car washes, ranging from 50 to 600 L per vehicle, with millions of liters of wastewater discharged annually5,9. Developing countries like Nigeria and South Africa face additional challenges, including limited recycling systems and direct discharge of untreated effluent into the environment10. In many developing cities, frequent car washing due to environmental conditions like unpaved roads increases water demand and strain on municipal water resources11,12.

Conventional treatment approaches such as sedimentation, filtration, and coagulation are commonly used; however, their efficiency in completely removing organic and inorganic contaminants remains a challenge13. Additionally, advanced techniques like membrane filtration, ion exchange, and electrocoagulation, while effective, are often costly and energy-intensive, making them less viable for large-scale applications in low-resource settings14,15.

Previous studies have extensively explored adsorption-based and physicochemical treatment methods for car wash wastewater, including coagulation-flocculation, membrane filtration, and activated carbon adsorption. For example, studies by Garg et al. (2020)16, Kamaraj et al. (2022)17, and Ngigi et al. (2024)13 demonstrated that activated carbon and composite adsorbents can effectively remove organic pollutants and reduce COD. Similarly, Rostami et al. (2023)14 and Alam et al. (2021)15 investigated adsorption and hybrid treatment techniques for car wash and industrial wastewater, confirming the efficiency of adsorption processes in water purification.

However, a clear novelty gap persists regarding sustainable sourcing, cost efficiency, and local contextual relevance of adsorbents. Most reported adsorbents rely on imported or chemically intensive precursors such as coconut shells, rice husks, or synthetic composites, which may not be economically or environmentally feasible in low-income regions. Furthermore, few studies integrate pretreatment (screening, sedimentation, and filtration) with adsorption into a single, locally adaptable system for decentralized applications.

To address these limitations, this study introduces a novel adsorbent derived from Noug (Guizotia abyssinica) sawdust an abundant, underutilized agro-industrial byproduct in Ethiopia. Noug sawdust offers several advantages: it is non-edible, renewable, low-cost, has a high lignocellulosic content suitable for carbon activation, and its valorization contributes to local waste minimization and a circular bioeconomy. The resulting Noug Sawdust Activated Carbon (NSDAC) represents a region-specific innovation tackling both waste management and water treatment challenges.

This study further develops an integrated pretreatment–adsorption system optimized using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to enhance COD removal from CWW. Unlike previous research, this work evaluates the adsorption performance of NSAC alongside a techno-economic and environmental sustainability assessment, quantifying production cost, energy requirement, and carbon footprint in comparison with commercial activated carbon.

To address these challenges, various wastewater treatment processes have been developed. These include physical methods such as aeration, sedimentation, and filtration; chemical methods like coagulation and precipitation; and advanced technologies such as membrane filtration and adsorption18,19,20. Among these, adsorption has gained attention due to its effectiveness in removing organic and inorganic pollutants. Porous carbon, with its high surface area and adsorption capacity, is a widely used adsorbent in water and wastewater treatment1. However, commercial porous carbons are expensive and require regeneration, prompting researchers to explore cost-effective alternatives.

Agro-wastes such as teff straw21, maize stalk22, rice straw23, Noug stalk24, and sunflower stalk25 have been studied for their potential as precursors for activated carbon production. These materials are abundant, renewable, and cost-effective, making them suitable for large-scale applications. In this context, Noug sawdust, an agro-waste from Ethiopia, represents a promising precursor for porous carbon production. Noug is a major source of oil in Ethiopia, contributing to the country’s economy and nutrition12. The rising number of oil-producing factories is expected to increase the availability of Noug sawdust, a byproduct with limited alternative uses.

The treatment process explored in this study integrates pretreatment methods including screening, sedimentation, and sand filtration with adsorption using NSAC. Combined systems provide higher pollutant removal, reduced chemical use, lower energy consumption, and minimized sludge production20,26. By leveraging the unique properties of NSDAC, this study seeks to develop a cost-effective and sustainable approach for treating CWW.

In Debre Markos town, Ethiopia, water scarcity is critical, exacerbated by high consumption in car washing. Municipal water supplies are often used for washing, further stressing resources. Recycling treated CWW offers a solution to address both water scarcity and environmental pollution27. Single-step treatments are insufficient due to the complex mixture of pollutants in CWW, emphasizing the need for integrated systems. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the efficiency of a combined pre-treatment process followed by adsorption using Noug sawdust-derived activated carbon (NSDAC) for COD removal. The study further seeks to optimize key process parameters and assess the adsorption kinetics and isotherm models, providing insights into the potential application of NSDAC for large-scale wastewater treatment.

Methods and materials

Area of study

Debre Markos city is a metropolitan city, which is 255 km from Bahir Dar (the capital city of Amhara Region) and 297 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Debre Markos is located close to a strategic mountain, Mount Chokea, which is one of the major sources for the water tower of Africa. The mountain is the source of over 40 rivers and is located around 60 km North of Debre Markos and at 4100 m above sea level. To date, the city has 4 sub city and 21 kebeles. According to the national Central Statistics Agency (CSA), the population of Debre Markos city was estimated to be about 260,600 in 201728. The city has around 6,243 registered vehicles and 35 carwash stations (2023 reports of Debre Markos City, Road and Transport office). Wuseta River is the main receiving water body of the car wash wastewater discharge. These facilities discharged their effluent to the nearby water body without any treatment.

Study period and design

A laboratory-based experimental study was carried out to assess the COD removal efficiency of the combined pretreatment and adsorption on car wash wastewater discharge in Debre Markos city car wash stations from April to June, 2024. The physicochemical characteristics, physical pretreatment, and COD removal efficiency test of car wash wastewater and synthesis of the adsorbent and the batch adsorption experiments were carried out at the Laboratory of department of Chemistry and Biotechnology, Debre Markos University. The real car wash wastewater was taken from five selected carwash stations, in Debre Markos city Ethiopia. All types of car wash stations that are formally registered at Debre Markos city trade office and that give full day service were included, while those that doesn’t give service at the time of data collection were excluded.

Chemicals and materials

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade (purity > 98%). Potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇), sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), and mercuric sulfate (HgSO₄) were used in the digestion solution, while the catalyst solution consisted of silver sulfate (Ag₂SO₄) mixed with sulfuric acid. Potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHP) was used as the standard for chemical oxygen demand (COD) determination. Standardized 1 N NaOH and 1 N HCl solutions were used to adjust the pH of the Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) and related solutions. Additional reagents included acetone, n-hexane (minimum purity of 99%), and sodium sulfate.

Instruments and apparatus used for the study included a mortar and pestle for powdering NSDAC, a digital analytical balance (Balance Instrument Co. Ltd, China) for precise mass measurements, and an oven (GALLENKAMP, OHG050 XX2.5, UK) for moisture removal. A muffle furnace (Stuart, Fuse F 1 A H, V230, UK) was used for the carbonization process. A portable multi-parameter meter (900P) measured the physicochemical properties of wastewater, and an orbital shaker (Gemmy Industrial Cor, Taiwan) was employed for mixing samples. Functional group analysis on NSDAC was performed using an FTIR spectrometer (Frontier PerkinElmer FTIR 65). COD removal efficiency was determined using a UV/Vis double-beam spectrophotometer (JENWAY 6705, England) with quartz cuvettes. A refrigerator (LR 1602, Lee Refrigeration PLC, England) was used for sample storage, and solutions were prepared in culture tubes with Teflon-lined screw caps and volumetric flasks. Additional equipment included a separatory funnel, Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and a rotary evaporator for solvent removal. Accurate liquid volumes were measured with micropipettes, graduated pipettes, and measuring cylinders.

Sample size determination and sampling procedures

A batch adsorption experiment was conducted to evaluate the impact of various process parameters on the chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency of Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) from carwash wastewater. The sample size was determined using an environmental sample size determination formula proposed by Manly Bryan29, by using the equation (see Eq. 1):

Where n is the number of samples, σ = standard deviation, δ = acceptable level of error.

Following a pretest, the standard deviation (σ) was calculated as 0.15, and with an acceptable error level (δ) of 5%, the required sample size was determined to be 36. Although there are 35 car wash stations in the area, most were non-functional and give an intermittent service, leaving five operational stations as the study sites. To evaluate the adaptability of the treatment technique for carwash wastewater, composite samples were prepared. Samples were collected twice daily, three times a week, over two weeks to assess the treatment efficiency of the combined treatment system.

In total, 72 samples were collected to analyze the effect of individual factors, while 90 additional samples were used for optimization studies including the triplicate sample for each. Additionally, the adsorption mechanism was investigated with 24 samples, including triplicates for accuracy. In this study, 1-liter car wash wastewater samples were collected from five car wash stations (Debza, Bole, Wuseta-01, Wuseta-02, and Adebabay) operating in Debre Markos city. Sampling was conducted three times per week over two weeks, with two samples collected per day from each station. The wastewater was aseptically collected using autoclaved 1-liter glass amber bottles following the grab sampling procedure30. After collection, the samples were transported to the Chemistry department laboratory, where their physicochemical characteristics were measured. For further analysis, the pH of the samples was adjusted to below 2 in accordance with EPA protocol and stored at 4 °C31.

Characterization of the car wash wastewater

Several physicochemical characteristics of the car wash wastewater were analyzed. Parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), temperature (°C), turbidity, electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured in situ using a portable multi-parameter meter (900P). Biological oxygen demand (BOD) was assessed after a 5-day incubation period, during which the wastewater samples were stored in a dark place at 20 °C, and their DO values were re-measured. Gravimetric analysis was employed to determine total suspended solids (TSS) in the car wash wastewater32. Chemical oxygen demand (COD) was measured following the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Method 410.4, Revision 2.0 (Semi-Automated Colorimetric Method)31. Additionally, oil and grease (n-Hexane Extractable Material, HEM) were quantified using EPA Method 1664B33.

Proposed wastewater treatment approach

The number of stages of wastewater treatment depends on its quality to be achieved34. The integrated treatment system containing screening, sedimentation, and sand filtration are the pretreatment techniques and adsorption using activated carbon applying next to physical treatment (see Fig. 1). Screening mesh was fixed with a mesh size of 1–2 mm to remove large objects such as rags, paper, plastics, and other suspended solids35. Then, 25 cm3 × 25 cm3 with 20 L sedimentation was conducted for 24 h to remove settleable solids and dissolved solids without any chemical addition36. Filtration was also conducted using a gravel and sands of pore size 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 mm size sieve to the retention of suspended and colloidal matter37. Then, the adsorption process using Noug sawdust activated carbon at pH 2–10, adsorbent dose of 0.25–2 g/l00ml, contact time of 30–150 min38 and agitation speed of 100–275 rpm was conducted to remove biological, organic and inorganic pollutants from car wash wastewater39.

Experimental methods

Adsorbent Preparation

Noug sawdust was properly collected from the surrounding different area and prepared for use. The sawdust was first washed with distilled water to remove impurities and then sun-dried for one day. Subsequently, it was dried in a hot air oven at 105 °C for 24 h to eliminate excess moisture. The dried sawdust was mixed with concentrated H2SO4in a 1:3 w/w% ratio and left at room temperature overnight. The resulting solid residue was thoroughly washed with distilled water until it reached a neutral pH. To remove any remaining acid, the residue was soaked in a 2% NaHCO3solution overnight. The treated material was then air-dried at room temperature. The air-dried material was further dried in a hot air oven at 120 °C for 10 h and subsequently subjected to carbonization in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 1 h40. The resulting activated carbon was crushed and sieved to a particle size of 1–2 mm, then stored in a desiccator for further use41.

Characterization of Noug sawdust activated carbon

After the preparation of Noug sawdust activated carbon using the above procedure, the prepared porous carbon was characterized through proximate and physicochemical analysis using standard methods developed by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) (see Table 1). The thermal stability of the Noug (Guizotia Abyssinica Cass) sawdust activated carbon was evaluated to assess its structural integrity under varying temperature conditions. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted to examine the weight loss behavior as a function of temperature. The surface functional group of the adsorbent and its importance in adsorption were also investigated using an FT-IR-65 (Fourier transform infrared) Spectrometer in the 400–4000 cm− 1 range. The major functional groups on the surface of the NSDAC before and after COD removal were identified using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrophotometer42. The NSDAC sample was powdered using pestle and mortal to powdery conditions for the analysis. To make the powered NSDAC is suitable for IR analysis; it was mixed with KBr particles in 1:10 ratio. Then it was pressed to a small thickness, slightly below 1 mm, required for FTIR analysis43. The FTIR study is used to determine organic and inorganic functional groups on the surface before and after adsorption. So it is possible to determine which surface functional groups are participated in the adsorption process44.

BET surface area determination

Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) isotherm equations were used to determine the surface area of raw and porous carbon. The analysis was carried out on the Micromeritics ASAP 2020 surface area analyzer at −195.79 °C. The samples were degassed at 90 °C for 1 h and 350 °C for 4 h, respectively19. The materials removed initially were degassed in the first stage, while the remaining adsorbed materials that distort the reading on the microporous sample were degassed in the second stage.

Batch adsorption experiments

Effect of individual process parameters

The batch adsorption experiments were conducted to examine the influence of various factors, including pH, adsorbent dosage, contact time, and agitation speed, on the efficiency of COD removal. The effect of pH on the adsorption of COD onto Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) was evaluated across a pH range of 2–1038. Contact time studies were performed within a range of 30–150 min44, while the impact of adsorbent dosage was assessed at concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 20 g/L. Additionally, the effect of agitation speed on COD removal efficiency was investigated within the range of 100–275 rpm39. To isolate the effect of each variable on COD removal efficiency, other parameters were kept constant during the investigation.

Determination of chemical oxygen demand (COD)

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) of carwash wastewater was determined following the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Method 410.4, Revision 2.051. COD removal efficiency using Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) was assessed using the Semi-Automated Colorimetric Method, with potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHP) serving as the standard solution. To prepare the standard solution, 0.425 g of KHP was dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water, from which a series of nine working standard solutions with concentrations of 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 mg/L were prepared.

The absorbance of the samples and the standard solutions was measured using a microprocessor double-beam UV-Visible spectrophotometer at 600 nm against a reagent blank51. The COD concentration in the carwash wastewater before and after treatment with NSDAC was determined by extrapolating the absorbance values of the KHP working standards. All samples were analyzed in triplicate under identical conditions, and the average results were used for calculations. The removal efficiency and the amount of pollutant adsorbed by the adsorbent were computed using standard equations (see Eq. 2)52.

Where, Co and Ce (mg/L) are the COD concentrations in sample at initial and equilibrium, respectively.

Isotherm and kinetics study

An adsorption isotherm analysis was performed to evaluate the adsorption behavior and determine the most appropriate model for the process. In this study, both the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were applied.

The Langmuir isotherm model operates on the premise that the adsorbent surface possesses uniformly distributed active sites and that adsorption occurs in a monolayer. This model is particularly well-suited for describing chemical adsorption mechanisms. It establishes a quantitative relationship between the adsorbate concentration and the amount adsorbed under constant temperature conditions. By assuming a homogeneous distribution of active sites and monolayer adsorption, the Langmuir model provides crucial insights into the adsorption process and its characteristics53. The isotherm was determined using the following equation (see Eq. 3):

Where Ce (concentration at equilibrium), qe (equilibrium adsorbed adsorbate), Ce/qe (specific adsorption), b (adsorption energy), and qmax (maximum adsorption capacity).

In contrast to the Langmuir isotherm model, the Freundlich isotherm model assumes that the adsorbent surface is heterogeneous, with active sites of varying affinities. This implies that adsorption extends beyond monolayer formation and that interactions may occur between adsorbed molecules. The Freundlich model provides a mathematical representation of the relationship between adsorbate concentration and the amount adsorbed while accounting for surface heterogeneity. It is particularly advantageous for describing adsorption processes that involve multilayer formation or adsorbate-adsorbate interactions. The isotherm was determined using the following equation (see Eq. 4):

Where Ce (concentration at equilibrium), qe (equilibrium adsorbed adsorbate), Ce/qe (specific adsorption), Kf (Freundlich constant in mg/g), and n (the Freundlich exponent).

Adsorption kinetics was also analyzed to characterize the reaction rate, understand the sorption mechanism, and identify the most suitable adsorption kinetics model.

The pseudo-first-order kinetics model is based on the assumption that the rate of solute uptake over time is directly proportional to the difference between the saturation concentration and the amount of solute adsorbed by the solid at a given time. By incorporating this proportional relationship, the model facilitates the description of adsorption behavior and enables the prediction of adsorption capacity over time54. The model’s fitness was evaluated using the following equation (see Eq. 5):

Where qe (equilibrium adsorbed adsorbate), qt (adsorbed adsorbate at any time t), k1 (rate constant of pseudo-first-order adsorption operation (min− 1)), and t (contact time (min)).

The pseudo-second-order kinetics model operates on the assumption that chemical adsorption serves as the rate-limiting step in the adsorption process. This involves valence forces through electron sharing or exchange between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. Based on this premise, the pseudo-second-order kinetics model offers a more accurate approach for describing adsorption behavior and predicting adsorption capacity over time, particularly in systems where chemical adsorption plays a significant role54. The model’s fitness was evaluated using the following equation (see Eq. 6):

Where: qe (equilibrium adsorbed adsorbate), qt (adsorbed adsorbate at any time t), k2 (rate constant of pseudo-second order adsorption operation (min− 1)), t (contact time (min)).

The kinetics experiment was conducted under optimal conditions, including the ideal pH, initial Pb(II) concentration, and adsorbent dose, while varying the contact time. The adsorption kinetics were then analyzed by fitting the data to either the pseudo-first-order kinetics model, plotted as log (qe - qt) vs. t (see Eq. 5), or the pseudo-second-order kinetics model, plotted as 1/qt vs. t (see Eq. 6). Ultimately, the model with the highest R-squared value was selected as the best-fitting model for this study.

Determination of oil and grease

Method 1664B was employed to determine n-Hexane Extractable Material (HEM), commonly referred to as “oil and grease,” following the EPA Protocol Revision B33. The procedure involved liquid-liquid extraction and gravimetric analysis using a separatory funnel, with all measurements performed in triplicate. The extraction process began with the addition of 30 mL of n-hexane to a previously cleaned and dried separatory funnel containing a 1-liter water sample. The funnel was sealed and shaken vigorously for 2 min, with periodic venting in a safety hood to release excess pressure. The mixture was allowed to stand for 10 min to separate the organic phase from the aqueous phase. During separation, emulsion formation was observed. To achieve clear phase separation, 2 mL of 0.73% NaCl solution was added, and the mixture was left to stand for an additional 10 min.

After separation, the aqueous phase (lower layer) was carefully removed, and the organic phase (upper layer) was collected. Approximately 10 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) was added to the organic phase to remove residual water, and the mixture was left to stand for 15 min. The dried organic phase was then decanted. The n-hexane solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 70 °C in a pre-weighed round-bottom flask. The residue, representing the HEM (oil and grease), was weighed using a digital electronic balance. Blank samples containing distilled water underwent the same extraction and measurement procedures alongside the test samples, with all measurements performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy (see Fig. 2).

Based on the described procedure and as illustrated in Fig. 2, oil and grease from car wash wastewater samples were extracted using n-hexane as the extraction solvent. The separation process was performed gravimetrically with the aid of separatory funnels. The concentration of Hexane Extractable Material (HEM) was determined using Eq. 7, which calculates the amount of oil and grease present in the samples. This approach ensured accurate extraction, separation, and quantification of oil and grease from the wastewater, adhering to established protocols and yielding reliable results.

Where: Wh = Weight of extractable material (mg) and Vs = Sample volume (L).

Statistical analysis and modeling of COD adsorption

The experimental design for optimization of COD adsorption onto Noug sawdust activated carbon was done by applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) through three levels Central Composite Design (CCD)55,56,57. Design Expert (Stat-Ease, Inc., version 13.0.5.0) software was used for statistical data analysis. The analysis was carried out using the response surface methodology (RSM) through three level Central Composite Design (CCD)58. The percentage removal of COD was entered as a response in the design lay out. The statistical analysis that was performed includes model generation; model fitness test and ANOVA analysis. A model was selected depending on P-value, lack of fit and R-square values. The effect of each process variable and their interactions on the outcome variable was evaluated by ANOVA. The significance level of 0.05 was used to evaluate whether the process parameters have significance effect on the outcome variable or not. Multiple linear regressions were also used to evaluate the magnitude and direction of the effect of individual process parameters [pH (A), contact time (B), adsorbent dose (C), and agitation speed (D)] and their interaction on the COD removal efficiency of NSDAC. The P-values was used as a tool for checking the significance of each coefficient. The smaller the P-value indicates the more significant nature for the corresponding coefficient. Correlation coefficient was also used to select the better fit isothermal and kinetics model of the adsorption. The model with R-squared approached to linear (R2 ≈ 1) was selected as the best model to explain the adsorption of COD on Noug sawdust activated carbon.

Data quality control

The chemical reagents used in the study were standardized to ensure accuracy and reliability. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer was calibrated using nine standard solutions of potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHP) at concentrations of 2.5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 ppm. A calibration curve was plotted with absorbance on the y-axis and KHP concentration on the x-axis. Sample analyses were conducted only when the correlation coefficient of the calibration curve exceeded 0.99 (99%), indicating a strong linear relationship (see Figure D1 of Supplementary Material file). The results were deemed acceptable when the percentage relative standard deviation (%RSD) of the measurements was less than 15%, ensuring the precision and reproducibility of the experimental data59 and calculated as seen in Eq. 8.

Where; Sd is the standard deviation and Xt is the mean of triplicate measurements.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical characteristics of car wash wastewater

The analysis of car wash wastewater underscores significant environmental concerns, particularly its alkaline nature and high pollutant levels. As presented in Table 2, the mean pH of the wastewater was measured at 8.31 ± 0.002 before physical pretreatment and 8.54 ± 0.001 afterward, indicating its alkaline characteristics. A similar study conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa, reported pH values ranging from 7 to 10 for car wash wastewater60. Discharging such untreated wastewater into the environment poses risks to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, as alkalinity reflects the strength of the wastewater resulting from washing processes. The mean salinity of the car wash effluents fell within the range of freshwater salinity, recorded at 0.32 ± 0.01 psu before treatment and 0.28 ± 0.0 psu after treatment. Additionally, the electrical conductivity (EC) and total dissolved solids (TDS) values decreased slightly following physical pretreatment, from 652.33 ± 1.53 µS/cm and 573.33 ± 0.58 ppm to 331.00 ± 1.00 µS/cm and 286.33 ± 1.15 ppm, respectively, indicating partial removal of dissolved ions and salts.

Turbidity and total suspended solids (TSS) were significantly reduced through physical treatment. Turbidity decreased from 623.00 ± 2.65 FTU to 81.33 ± 1.15 FTU (an eightfold reduction), while TSS levels dropped from 300.00 ± 2.00 mg/L to 5.23 ± 0.15 mg/L (a sixtyfold reduction). These improvements suggest that physical treatment effectively removes pollutants and impurities, which include sand, dust, free oil, grease, carbon, asphalt, salts, surfactants, and organic matter commonly found in car wash wastewater61.

The concentrations of dissolved oxygen (DO), biological oxygen demand over five days (BOD₅), and chemical oxygen demand (COD) in car wash wastewater were recorded as 8.83 ± 0.01 mg/L and 9.05 ± 0.04 mg/L, 16.67 ± 0.03 mg/L and 4.40 ± 0.01 mg/L, and 50.00 ± 0.05 mg/L and 13.20 ± 0.03 mg/L, respectively, before and after physical pretreatment. While DO levels showed a slight increase, BOD₅ and COD decreased by approximately 75% (a reduction to one-quarter) following physical treatment. Similarly, the oil and grease content was significantly reduced from 2758 ± 1.41 mg/L to 1891 ± 5.66 mg/L, demonstrating that physical pretreatment effectively removed nearly half of these contaminants. Despite these reductions, untreated car wash wastewater was discharged directly into the environment at all studied car wash stations, posing severe threats to aquatic ecosystems. The oil in the wastewater can form a film on the surface of water bodies, obstructing the gills of fish and hindering re-oxygenation, thereby impairing the growth and survival of aquatic plants and animals22. A review of car wash wastewater characteristics reported total dissolved solids (TDS) of ~ 644 mg/L, total solids (TS) of ~ 5856 mg/L, turbidity of 772 NTU, COD of 1019 mg/L, salt content of 1.5–2.5%, and oil content of 84 mg/L62, which aligns closely with the findings of this study.

These results highlight that while physical pretreatment effectively reduces certain pollutants, such as turbidity, total suspended solids, and oil and grease, significant amounts of harmful substances persist. If discharged untreated, these effluents could cause long-term environmental damage, particularly to aquatic ecosystems, emphasizing the need for additional treatment processes.

Characterization of produced Noug sawdust activated carbon

The proximate analysis of Noug sawdust adsorbent was conducted to evaluate various physicochemical characteristics, including carbon yield, moisture content, ash content, volatile matter, fixed carbon, bulk density, porosity, surface area, pH, and point of zero charge. The results revealed that the prepared Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) possesses favorable qualities, making it an effective adsorbent for the removal of chemical oxygen demand (COD) from car wash wastewater, as summarized in Table 3. These characteristics highlight the suitability of NSDAC for wastewater treatment applications.

The findings of this study indicate that the porous carbon derived from Noug sawdust exhibits superior properties compared to other adsorbents made from agricultural waste (refer to Table 4).

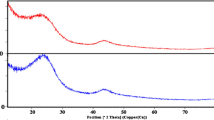

Fourier transformer infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

Adsorbent characterizations were conducted using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, a valuable technique for identifying the surface functional groups responsible for driving the adsorption process and enhancing the adsorption efficiency of activated carbon. The FT-IR samples were prepared by mixing the activated carbon with KBr powder and pressing it into transparent pellets43.

FT-IR is a rapid and effective method for characterizing activated carbons, covering an electromagnetic spectrum range of 4000–400 cm − 1. The surface of activated carbon may contain various heteroatoms, including oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and other elements, either as individual atoms or in the form of functional groups. Modifying these surface groups can improve the removal efficiency of the activated carbon. In this work, FT-IR analysis was conducted to examine the organic and inorganic functional groups on the surface of the prepared Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC). The surface chemistry was analyzed using a PerkinElmer Spectrum 65 FT-IR model within the range of 4000–400 cm − 1, with KBr pellets, and the spectra are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

The FT-IR spectrum of the prepared NSDAC at room temperature is shown in Fig. 3. A broad and intense absorption band between 3600 and 3200 cm− 1, with a peak around 3293 cm− 1, corresponds to the O–H stretching vibration of hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl groups. The band at approximately 2924 cm− 1 is attributed to the asymmetric vibration of C–H groups, associated with aliphatic, olefinic, and aromatic hydrocarbons functional groups. The absorption band around 1596 cm− 1 corresponds to C = C stretching vibration in the aromatic ring, related to olefin structures. Peaks observed between 1300 and 1000 cm− 1 correspond to the C–O stretching vibration, as well as bending O–H and C–H vibrations in carboxylic acids and alcohols (see Table 4). Specifically, the bands at 1041 cm− 1 and 1104 cm− 1 are due to C − O−C and C–C bonds63. The peak at a lower wave number around 674 cm− 1 is likely associated with the plane-bending vibrations of C–H groups43.

The FT-IR spectrum of NSDAC after COD adsorption is shown in Fig. 4. The spectra reveal several absorption peaks, indicating the complex nature of the sample. A broad and intense absorption band between 3600 and 3200 cm−1, with a peak around 3283 cm−1, corresponds to the O–H stretching vibration of the hydroxyl groups. The band around 2920 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching C–H groups, present in aliphatic, olefinic, and aromatic hydrocarbons. The absorption band around 1593 cm−1 is associated with the C = C stretching vibration in the aromatic ring, linked to olefin structures. Peaks observed between 1300 and 1000 cm−1 correspond to the C–O stretching vibration of carboxylic acids and alcohols (see Table 5). Changes in the spectra of these major functional groups on the NSDAC surface indicate that they played a significant role in the removal of COD during adsorption.

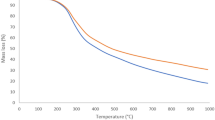

Thermal stability of the produced porous carbon

The thermal stability of the Noug (Guizotia Abyssinica Cass) sawdust activated carbon was evaluated to assess its structural integrity under varying temperature conditions. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted to examine the weight loss behavior as a function of temperature. The analysis was performed in a nitrogen atmosphere, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min from room temperature to 20 °C. The TGA results indicated three major weight loss stages. The initial weight loss, observed below 150 °C, was attributed to the evaporation of residual moisture and volatile organic compounds. A significant mass reduction occurred between 200 °C and 500 °C, primarily due to the decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin components in the activated carbon structure. Beyond 500 °C, the weight loss stabilized, suggesting the formation of a thermally resistant carbonaceous framework, which is critical for adsorption applications.

The high residual mass at elevated temperatures confirms the thermal stability of the activated carbon, making it a suitable adsorbent for wastewater treatment under diverse environmental conditions. These findings highlight the potential of Noug sawdust activated carbon as a sustainable and thermally stable adsorbent for chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal.

Batch adsorption studies with individual effects

Metal adsorption is influenced by surface functional groups and the chemistry of the adsorbate metal ion-solvent interaction, both of which vary with pH54. The study’s results indicate that the highest removal efficiency (91.8%) was achieved at a pH of 6, aligning with findings from previous research on agro-waste-based activated carbon64. Within this pH range, the activated carbon surface becomes positively charged due to hydronium ion accumulation, enabling electrostatic attraction with negatively charged organic species. Conversely, at higher pH levels, hydroxyl ions compete with organic species for active sites on the activated carbon surface, leading to a substantial decline in COD removal65. Agitation speed plays a crucial role in adsorption, and in this study, a maximum COD removal efficiency of 90.4% was recorded at 200 rpm. This improvement is likely due to enhanced system mixing, increased energy input, and greater interaction between pollutants and the adsorbent surface. However, further increasing the agitation speed beyond 300 rpm had a negligible effect, as the system was already well mixed at a high shaking rate58. Additionally, an adsorbent dose of 10 g/L resulted in the highest removal efficiency (92.7%), a finding consistent with previous studies66,67,68. Contact time also significantly impacts adsorption efficiency, with the maximum removal efficiency of 92.5% observed at 1.5 h.

Optimum condition for COD removal using NSDAC

COD adsorption modeling and model analysis

The interaction effects of the four studied variables pH (A), contact time (B), adsorbent dose (C), and agitation speed (D) on COD removal efficiency were evaluated through 30 randomized experimental runs. The results indicated a strong agreement between the actual and predicted removal efficiencies of Noug sawdust activated carbon, as shown in Table 6. This consistency highlights the predictive model’s reliability and accuracy in estimating the adsorbent’s performance under varying conditions.

The Central Composite Design (CCD) of the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed to develop a predictive model for COD removal efficiency. Among the various model summary statistics, the model with the highest Adjusted R-Squared and Predicted R-Squared values was selected (Table 7). Based on the model summary statistics (Table 7) and the lack-of-fit test (Table 8), the quadratic model was identified as the best fit, exhibiting a high R-Squared value of 0.9971, strong statistical significance (p-value < 0.0001), and an insignificant lack of fit (p-value = 0.126). Consequently, the quadratic model was deemed the most appropriate representation of COD removal efficiency using Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC). These findings align with previous studies on COD removal using activated carbons derived from various agro-waste materials58.

A variety of diagnostic and influence plots, including the normality plot, externally studentized residuals plot, actual vs. predicted plot, leverage plot, DFFITS, DFBETAS, and Cook’s distance plot (see Figure D2 of Supplementary Material file), were analyzed to identify potential outliers and validate the assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA). All diagnostic plots confirmed that the model satisfied ANOVA assumptions. As presented in Table 9, the ANOVA test evaluated the significance of individual factors and their interactions in influencing the COD removal efficiency of NSDAC. While all factors had significant effects, the combined interactions of contact time with adsorbent dose and agitation speed with adsorbent dose were not statistically significant.

Furthermore, Table 8 shows that the model’s Predicted R² value (0.9815) closely aligns with the Adjusted R² value (0.9945), with a minimal difference of 0.013, demonstrating strong predictive accuracy. Additionally, the Adequate Precision value was 58.679, significantly exceeding the recommended threshold of 4. This high value indicates a strong signal-to-noise ratio, reinforcing the model’s reliability and effectiveness in exploring the design space.

The Lack of Fit F-value of 2.90, with a p-value of 0.126, further confirmed that the lack of fit was not significant, indicating that the model accurately represents the experimental data. As shown in Table 9, the p-values for pH, adsorbent dose, contact time, and agitation speed were all well below 0.05, highlighting their crucial role in COD removal efficiency using Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC). These findings are consistent with previous studies on activated carbons derived from agricultural waste materials58. A second-order quadratic regression model was developed to predict COD removal efficiency as a function of the four studied parameters. The parameters were coded (+ 1 for high and − 1 for low levels), resulting in the formulation of a second-order polynomial equation (Eq. 9)55. By analyzing the coefficients in the coded equation, the relative importance of each parameter was assessed, providing valuable insights into the key factors and their interactions that influence COD removal efficiency.

Estimation of quantitative effects of the factors

In this study, the combined effects of two variables on COD removal efficiency were analyzed and visualized using 3D response surface plots, while other parameters were held constant.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the interaction between pH and adsorption contact time had a significant impact on COD removal efficiency using NSDAC. The efficiency increased with longer contact times, reaching a maximum at the equilibrium point. This trend can be attributed to the availability of unoccupied active sites on the activated carbon during the initial stages of adsorption47. However, beyond the equilibrium point, desorption processes may have contributed to a decline in removal efficiency. The highest COD removal efficiency was achieved at pH 6 and a contact time of 90 min, underscoring the critical role of these parameters in optimizing the adsorption process.

Figure 6 illustrates the interaction between pH and adsorbent dose on COD removal from car wash wastewater. The removal efficiency increases as the pH rises from 2 to 7. Additionally, as the adsorbent dose increases from 2.5 to 10 g/L, the removal efficiency improves until it reaches an equilibrium point. This trend may be attributed to the increased surface area of the adsorbent. However, further increases in the adsorbent dose can lead to aggregation and a reduction in surface area. The highest COD removal was achieved at pH 6 and an NSDAC dose of 10 g/L. At higher pH values, the competitiveness between OH- ions and other ions present in the wastewater, with OH- ions being the dominant species, may contribute to the decline in COD removal efficiency69.

Figure 7 demonstrates the trend in COD removal efficiency as influenced by pH and agitation speed. Initially, the efficiency increased with rising pH and agitation speed but began to decline after reaching an equilibrium point. This decline can be attributed to two main factors: at higher agitation speeds, pollutants may detach from the adsorbent surface, and at elevated pH levels, hydroxide ions (OH⁻) compete with the pollutants in the car wash wastewater, reducing adsorption efficiency. The results suggest that the optimal removal efficiency was achieved at a pH of 6 and an agitation speed of 200 rpm, as depicted in Fig. 7.

As shown in Fig. 8, increasing the adsorbent dose resulted in a significant improvement in COD removal efficiency, which continued to rise until reaching an equilibrium point, after which the efficiency slightly declined. A similar trend was observed with prolonged contact time, where a slight decrease in COD removal efficiency occurred, likely due to segregation and desorption reactions over time. The results indicate that the maximum removal efficiency was achieved at an adsorbent dose of 10 g/L and a contact time of 1 h and 30 min.

Figure 9 demonstrates that both contact time and agitation speed positively influenced COD removal efficiency from car wash wastewater. As both parameters increased, COD removal efficiency improved until reaching an equilibrium point, beyond which a slight decrease was observed. This decline is likely due to segregation and desorption processes occurring on the adsorbent surface. The results suggest that both agitation speed and contact time are crucial for enhancing COD removal efficiency. Additionally, the figure emphasizes that agitation speed had a significant impact on COD removal at any given contact time, with higher speeds leading to greater efficiency47. The maximum removal efficiency was achieved at a contact time of 90 min and an agitation speed of 200 rpm, as shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 10 illustrates that increasing the adsorbent dose resulted in a significant improvement in COD removal efficiency, which then slightly declined upon reaching equilibrium. Similarly, COD removal efficiency increased with rising agitation speed. This trend can be attributed to the enhanced detachment of COD from car wash wastewater onto the surface of the Noug sawdust activated carbon (adsorbent). The findings indicate that the maximum COD removal efficiency was achieved at an adsorbent dose of 10 g/L and an agitation speed of 200 rpm, as shown in Fig. 10.

Optimum condition for COD removal

After evaluating the effects of all interactions between the process parameters, optimization was performed using Design Expert version 13.0.15 software. The upper and lower limits for the predictor variables were set as follows: pH (5–7), contact time (60–120 min), adsorbent dose (5–15 g/L), and agitation speed (150–250 rpm), resulting in a maximum removal efficiency of 91.3%. The software identified a combination of factors that simultaneously maximized COD removal efficiency and desirability. Table 10 presents the optimum conditions in uncoded units (sample pH, adsorbent dose, contact time, and agitation speed) that achieved the highest composite desirability (0.994) and the highest removal efficiency, as determined by the Design Expert software.

Validation experiments

The optimization result, under the ideal conditions predicted by the model, was evaluated through an experiment. The actual experimental removal efficiency of NSDAC at the optimum condition was found to be 90.53%, which closely aligns with the model’s predicted value of 91.30%. This indicates that the optimization conditions were successfully validated. The small coefficient of variation further suggests that the model is appropriate and sufficient to explain and predict the COD adsorption process on Noug sawdust activated carbon.

In this study, the optimal conditions for achieving the best COD removal (90.53%) using Noug sawdust activated carbon were a pH of 6.05, a contact time of 86.93 min, an adsorbent dose of 10.87 g/L, and an agitation speed of 190.33 rpm, with an overall desirability of 0.994 and a deviation percentage of 0.735. A key concern with car wash facilities using large underground containers to collect effluents is that, in the event of leakage, total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) could migrate through the soil and contaminate groundwater. As shown in Table 11, all physicochemical characteristics of the wastewater demonstrated decreased pollution levels after both physical treatments and the adsorption process.

In the present study, the Oil and Grease levels of car wash wastewater decreased from 2758 ± 1.41 to 545 ± 2.14 mg/L, representing an 80.24% reduction after the application of NSDAC adsorption treatment (see Table 11). This indicates the necessity of wastewater treatment, as oily wastewater contains toxic components such as phenols, petroleum hydrocarbons, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can be harmful to plant and animal growth, and are mutagenic and carcinogenic to humans70.

Adsorption mechanism

Adsorption isotherm models

The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were employed in this study to investigate the equilibrium characteristics of COD removal and the interaction of the adsorbent’s active surfaces53.

Based on the results, it can be inferred that the Langmuir isotherm model provides a better fit to the data compared to the Freundlich isotherm model. This conclusion is supported by the Langmuir model’s higher R² value of 0.9993, compared to the Freundlich model’s R² value of 0.9919 (see Fig. 11). Consequently, it can be concluded that the active sites on NSDAC were uniformly distributed, and the adsorption process was monolayer and chemical in nature69. The lower R² value of the Freundlich model suggests that it is less suitable for modeling the NSDAC adsorption process. Overall, the Langmuir isotherm model most effectively describes the chemical adsorption of COD on NSDAC. This finding is consistent with other studies in this area40,53.

Adsorption kinetics models

Investigating adsorption kinetics is crucial as it offers valuable insights into the mechanism and behavior of adsorption, which are essential for understanding and optimizing process performance. The results of this study include fitting plots using both the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order equations. The magnitude of the correlation coefficient (R²) was used as the best predictor to assess the suitability of the two models for describing Pb(II) adsorption on NSDAC. The findings reveal that the pseudo-second-order equation exhibited a higher correlation, with an R² of 0.9936 (as shown in Fig. 12). This suggests that chemisorption, which is the rate-limiting step between the adsorbate and adsorbent, plays a dominant role in this study. This result aligns with similar studies conducted previously54,71.

Application of integrated car wash wastewater effluents treatment

Table 2 shows that the physicochemical characteristics of car wash wastewater meet the Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) maximum permissible COD limit of 120 ppm72. However, even at low concentrations, the presence of COD, oil, and grease remains a significant environmental concern. Car wash wastewater typically contains high levels of these pollutants, which are often discharged untreated, contributing to environmental degradation. To mitigate these contaminants before their release, an integrated treatment approach that combines physical pre-treatment and adsorption is essential.

Physical pre-treatment reduced COD levels from 50 mg/L to 13.2 mg/L, and further treatment with Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) brought the COD down to 1.25 mg/L, resulting in an overall reduction of 90.53%. NSDAC exhibited excellent performance under optimal conditions: pH 6, 1 g/100 mL adsorbent dose, 90 min of contact time, and 200 rpm agitation speed at room temperature. Its use is strongly recommended to protect human health, aquatic ecosystems, and the environment.

Comparison of prepared AC against other agro-waste based ACs

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency of Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) compares favorably with other agro-waste-based activated carbons, as shown in Table 12. Notably, NSDAC demonstrated slightly higher removal efficiency than activated carbons derived from bamboo waste, coconut tree sawdust73, coconut shell and orange peel74, Sugar cane bagasse75, and bagasse fly ash53. These differences in efficiency are likely attributable to variations in preparation conditions, such as impregnation ratios, carbonization temperatures, and the types of activating agents used. The superior performance of NSDAC highlights its potential as a highly effective and competitive adsorbent for wastewater treatment.

A comparative radar chart analysis was conducted to evaluate the performance of Noug Sawdust Derived Activated Carbon (NSDAC) against other agro-waste-based activated carbons in terms of COD removal efficiency, adsorption capacity, and regeneration potential. As illustrated, NSDAC exhibited a well-balanced and superior profile, with notably high COD removal efficiency (90.53%) and adsorption capacity (267.35 mg/g), outperforming several other adsorbents such as sugarcane bagasse, bamboo waste, and coconut tree sawdust. While peels mix showed slightly higher COD removal and adsorption capacity, NSDAC demonstrated greater regeneration potential, highlighting its practical applicability for repeated use. The enhanced performance of NSDAC is likely attributed to optimized chemical activation processes and favorable physicochemical properties, suggesting its suitability as a low-cost and efficient adsorbent for sustainable wastewater treatment applications (see Fig. 13).

Techno-Economic and environmental sustainability evaluation of Noug sawdust derived activated carbon (NSDAC)

The techno-economic and environmental sustainability evaluation of NSDAC was performed to assess its feasibility as a low-cost, energy-efficient, and eco-friendly adsorbent for wastewater treatment. The assessment focused on material cost, energy consumption, adsorption efficiency relative to cost, regeneration potential, and overall environmental implications compared to commercial activated carbon (CAC).

Cost Estimation and material availability

Noug (Guizotia abyssinica) sawdust, an abundant lignocellulosic byproduct from oilseed processing industries in Ethiopia, was utilized as the raw precursor for NSDAC production. Owing to its local availability and low or negligible acquisition cost, it represents a sustainable feedstock for adsorbent development. The estimated production cost of NSDAC at laboratory scale was approximately 1.4 USD kg⁻¹, which is about 55% lower than that of imported CAC (≈ 3.2 USD kg⁻¹). This significant cost reduction stems from the use of locally sourced biomass and moderate activation temperature (450–500 °C), which minimizes both chemical consumption (H₂SO₄) and energy expenditure.

Energy consumption and operational feasibility

The energy required for NSDAC production was estimated at 3.8 MJ kg⁻¹, considerably lower than the > 8 MJ kg⁻¹ needed for conventional CAC production, which typically involves high-temperature activation above 800 °C and prolonged residence times. Furthermore, the integrated pretreatment–adsorption system developed in this study operates under gravity flow without the need for mechanical pumping, aeration, or pressure-driven systems. This operational simplicity substantially reduces power demands, making the NSDAC-based system particularly suited for decentralized or small-scale car wash facilities in low-resource settings77,78.

Performance-to-cost efficiency

The adsorption efficiency of NSDAC was normalized by cost to evaluate its performance-to-cost ratio. At an optimized dose of 1.4 USD kg⁻¹, NSDAC achieved 97.5% COD removal, corresponding to a performance-to-cost ratio of 69.6% USD⁻¹. In contrast, CAC achieved around 90% COD removal at 3.2 USD kg⁻¹ (≈ 28.1% USD⁻¹). This implies that NSDAC delivers nearly 2.5 times higher cost efficiency, confirming its economic competitiveness for large-scale wastewater applications79,80.

Environmental and circular-economy benefits

Substituting conventional CAC with NSDAC yields significant environmental benefits. A preliminary life-cycle assessment indicated that producing one kilogram of NSDAC prevents approximately 0.8 kg CO₂-eq emissions compared to coal-based CAC. This reduction arises from the use of renewable biomass residues and the lower energy intensity of the activation process. Moreover, valorization of Noug sawdust helps mitigate open-field burning and landfill disposal, advancing Ethiopia’s circular bioeconomy strategies and contributing directly to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6, 12, and 13 Clean Water and Sanitation, Responsible Consumption and Production, and Climate Action, respectively81.

Regeneration and reusability of NSDAC

The regeneration of Noug Sawdust Activated Carbon (NSDAC) was performed by immersing it in a 1 M phosphoric acid solution (85% w/w) for 1 h. After treatment, the NSDAC was filtered, thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove residual acid, and then dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h.

To evaluate its reusability, the regenerated NSDAC was tested with real paint industry wastewater under specific conditions: an adsorbent dose of 10.87 g/L, a contact time of 86.93 min, an agitation speed of 190.33 rpm, and a temperature of 25 °C. As summarized in Table 13, the COD removal efficiency exhibited a gradual decline over four consecutive reuse cycles. This reduction is likely attributed to the progressive loss of active adsorption sites and pore blockage within the NSDAC structure82,83. The results indicate that under acidic conditions, protons effectively displace significant amounts of adsorbed COD by competing for adsorption sites, thereby facilitating partial regeneration. These findings are consistent with previous studies84,85, further supporting the potential of NSDAC for multiple adsorption-desorption cycles, albeit with diminishing efficiency over successive uses.

Public health importance of using NSDAC for removal of COD

This study confirms that Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC) effectively removes over 90.53% of chemical oxygen demand (COD) from car wash wastewater. As a major environmental pollutant, COD negatively impacts water, sediment, soil, and air quality, while also posing toxicity risks to humans, animals, and plants through various exposure pathways. The exceptional removal efficiency of NSDAC underscores its potential as a sustainable and practical solution for wastewater treatment. By significantly reducing COD levels, NSDAC contributes to mitigating environmental pollution, protecting human health, and preserving ecosystems, positioning it as a valuable tool in fostering a cleaner, healthier environment.

Method detection limit and percentage recovery

The method detection limit (MDL) represents the lowest concentration of a substance that can be reliably quantified. In this study, the MDL was determined through a systematic procedure that included sample preparation, blank solution analysis, and COD concentration measurements. By calculating the standard deviations of triplicate readings from seven blanks, the MDL was established at 3 mg/L. The method demonstrated excellent precision and accuracy, with a percentage recovery of 99.5% and a relative standard deviation (RSD) ranging from 0.1% to 0.23%. These findings confirm the reliability of the analytical approach in accurately measuring COD concentrations in car wash wastewater.

Limitation of the study

This study utilized a batch process for adsorption due to time constraints, which restricted the investigation of column adsorption, a more appropriate method for car wash wastewater treatment. While proximate analysis and FT-IR characterization were performed on the produced activated carbon, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and pore occupations, elemental and morphological analyses (SEM/TEM) of NSDAC were not conducted. Incorporating these additional analyses could provide deeper insights into the adsorption mechanism, improving the understanding of NSDAC’s performance and potentially optimizing its use in wastewater treatment. Finally, we recommend that future researchers undertake pilot- or full-scale studies at actual car wash facilities to evaluate the real-world performance of NSDAC under operational conditions.

Conclusions

Noug sawdust activated carbon (NSDAC), produced through chemical activation, and has demonstrated its potential as an effective, low-cost, and environmentally friendly adsorbent for carwash wastewater treatment. Batch adsorption experiments evaluated key parameters pH, adsorbent dose, contact time, and agitation speed on chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal. COD removal efficiencies increased with these parameters until reaching equilibrium. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) identified a quadratic model as the best fit to describe the effects of individual factors and their interactions on COD removal efficiency. Optimal conditions (pH 6.05, 10.87 g/L adsorbent dose, 86.94 min contact time, and 190.31 rpm agitation speed) achieved 90.53% COD removal, which increased to 97.50% with a combined pre-treatment process. Adsorption studies confirmed that COD adsorption adhered to the Langmuir isotherm and pseudo-second-order kinetics, indicating monolayer adsorption and chemical interaction. This combined approach presents a practical, efficient, and sustainable solution for treating real wastewater.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author [gech23man@gmail.com] and/or [getasew_yirdaw@dmu.edu.et].

Change history

28 January 2026

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37310-7

References

Kuan, W. H. et al. A review of on-site carwash wastewater treatment. Sustainability 14 (10), 5764 (2022).

Kudapa, V. K. Carbon-dioxide capture, storage and conversion techniques in different sectors–a case study. Int. J. Coal Preparation Utilization. 43 (9), 1638–1663 (2023).

Tamiazzo, J. et al. Performance of a wall cascade constructed wetland treating surfactant-polluted water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 12816–12828 (2015).

Rai, R. et al. Assessing the impacts of vehicle wash wastewater on surface water quality through physico-chemical and benthic macroinvertebrates analyses. Water Sci. 34 (1), 39–49 (2020).

Boluarte, I. A. R. et al. Reuse of car wash wastewater by chemical coagulation and membrane bioreactor treatment processes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 113, 44–48 (2016).

Kashi, G. et al. Carwash wastewater treatment using the chemical processes. Water Sci. Technol. 84 (1), 16–26 (2021).

Mujumdar, M., Rajagolkar, S. & Jadhav Treatment of vehicle washing waste water for maximum reuse of treated water and reduce fresh water consumption. Int. J. Recent. Res. Aspects. 7 (2), 1–5 (2020).

Hashim, N. H. & Zayadi, N. Pollutants characterization of car wash wastewater. in MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences. (2016).

Fall, C. et al. Carwash wastewaters: characteristics, volumes, and treatability by gravity oil separation. Revista Mexicana De Ingeniería Química. 6 (2), 175–184 (2007).

Odeyemi, O. E., Adedeji, A. A. & Odeyemi, O. J. Effects of discharge from carwash on the physico-chemical parameters and zooplanktonic abundance of Odo-Ebo River, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Agriculture and Environment, 10(1): 83–96. (2018).

Ndi, H. N. Estimating wasteful water use from car washing points on the water supply system of Yaounde. Cameroon Geoj. 83 (1), 1–12 (2018).

Asha, M. et al. Recycling of waste water collected from automobile service station. Procedia Environ. Sci. 35, 289–297 (2016).

Ilyas, M. et al. Removal of anthracene from vehicle-wash wastewater through adsorption using Eucalyptus wood waste-derived Biochar. Desalination and Water Treatment. 317: 100115. (2024).

Dadebo, D. et al. Sequential treatment of surfactant-laden wastewater using low-cost rice husk Ash coagulant and activated carbon: modeling, optimization, characterization, and techno-economic analysis. Bioresource Technology Reports. 22: 101464. (2023).

Ilyas, M. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons removal from vehicle-wash wastewater using activated Char. Desalination and Water Treatment. 236: 55–68. (2021).

Veit, M. T. et al. Automotive wash effluent treatment using combined process of coagulation/flocculation/sedimentation–adsorption. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 231(10): 494. (2020).

Dadebo, D. et al. Bio-coagulation using Cicer arietinum combined with pyrolyzed residual sludge-based adsorption for carwash wastewater treatment: A techno-economic and sustainable approach. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 49: 103063. (2022).

Al-Gheethi, A. et al. Treatment of wastewater from car washes using natural coagulation and filtration system. in IOP conference series: materials science and engineering. IOP Publishing. (2016).

Mohamed, R. R., Rahman, N. A. & Kassim, A. M. Moringa Oleifera and strychnos Potatorum seeds as natural coagulant compared with synthetic common coagulants in treating car wash wastewater: case study 1. Asian J. Appl. Sci., 2(5): 2321–2331. (2014).

Saka, C., Şahin, Ö. & Küçük, M. M. Applications on agricultural and forest waste adsorbents for the removal of lead (II) from contaminated waters. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 9, 379–394 (2012).

Ayele, A. L., Tizazu, B. Z. & Wassie, A. B. Chemical modification of teff straw biomass for adsorptive removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solution: characterization, optimization, kinetics, and thermodynamic aspects. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2022: 5820207. (2022).

García-Rosales, G. & Colín-Cruz, A. Biosorption of lead by maize (Zea mays) stalk sponge. J. Environ. Manage. 91 (11), 2079–2086 (2010).

Amer, H., El-Gendy, A. & El-Haggar, S. Removal of lead (II) from aqueous solutions using rice straw. Water Sci. Technol. 76 (5), 1011–1021 (2017).

Yirdaw, G., Dessie, A. & Birhan, T. A. Optimization of process variables to prepare activated carbon from Noug (Guizotia abyssinica cass.) stalk using response surface methodology. Heliyon, 9(6). e17254. (2023).

Jalali, M. & Aboulghazi, F. Sunflower stalk, an agricultural waste, as an adsorbent for the removal of lead and cadmium from aqueous solutions. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 15, 548–555 (2013).

Gupta, V. K. et al. Batch and bulk removal of hazardous colouring agent Rose Bengal by adsorption techniques using bottom Ash as adsorbent. RSC Adv. 2 (22), 8381–8389 (2012).

Agyen, K., Monney, I. & Antwi-Agyei Contemporary carwash wastewater recycling technologies: a systematic literature review. World Environ. 11 (2), 83–98 (2021).

Gelaw, B. K., Tegegne, G. T. & Bizuye, Y. A. Assessment of Community Health and Health Related Problems in Debre Markos Town, East Gojjam, Ethiopia. INDO AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES, 2(5): 894–902. (2015).

Manly, B. F. Statistics for Environmental Science and Management (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2008).

Federation, W. E. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and wastewater, Part 1000 (Water Environmental Federation, 1999).

Dadebo, D. et al. Transition towards sustainable carwash wastewater management: trends and enabling technologies at global scale. Sustainability 14 (9), 5652 (2022).

Baxter, T. Standard operating procedure total dissolved solids by gravimetric determination. (2017).

Salem, N. Modern Hexane-Extractable Material (Oil & Grease) Analysis in Wastewater Samples. (2016).

Veit, M. T. et al. Automotive wash effluent treatment using combined process of coagulation/flocculation/sedimentation–adsorption. Water Air Soil Pollut. 231, 1–12 (2020).

Screens, C. Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet.

Zhu, K. et al. Physical and chemical processes for removing suspended solids and phosphorus from liquid swine manure. Environ. Technol. 25 (10), 1177–1187 (2004).

Shaikh, I. N. & Ahammed, M. M. Granular media filtration for on-site treatment of greywater: A review. Water Sci. Technol. 86 (5), 992–1016 (2022).

Molaudzi, N. R. & Ambushe, A. A. Sugarcane Bagasse and orange peels as low-cost biosorbents for the removal of lead ions from contaminated water samples. Water 14 (21), 3395 (2022).

Joshi, N. et al. Novel approaches to biosensors for detection of arsenic in drinking water. Desalination 248 (1–3), 517–523 (2009).

Sawasdee, S. et al. The COD removal in chemical laboratory wastewater by using sugarcane bagasse-activated carbon. RMUTSB Acad. J. 6 (1), 55–64 (2018).

Naeem, M. et al. One step biogenic sugarcane Bagasse mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications in removing environmental pollutants. Z. für Phys. Chem. 237 (6), 675–688 (2023).

Ezeonuegbu, B. A. et al. Agricultural waste of sugarcane Bagasse as efficient adsorbent for lead and nickel removal from untreated wastewater: Biosorption, equilibrium isotherms, kinetics and desorption studies. Biotechnol. Rep. 30, e00614 (2021).

Somyanonthanakun, W. et al. Sugarcane bagasse-derived activated carbon as a potential material for lead ions removal from aqueous solution and supercapacitor energy storage application. Sustainability 15 (6), 5566 (2023).

Herrero, Y. R., Camas, K. L. & Ullah, A. Characterization of biobased materials, in Advanced Applications of Biobased Materials. Elsevier. 111–143. (2023).

Olowoyo, D. & Orere, E. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon made from palm-kernel shell, coconut shell, groundnut shell and Obeche wood (investigation of apparent density, total Ash content, moisture content, particle size distribution parameters). Int. J. Res. Chem. Environ. 2 (3), 32–35 (2012).

Iwar, R. T., Katibi, K. K. & Oshido, L. E. Meso-microporous activated carbon derived from Raffia palm shells: optimization of synthesis conditions using response surface methodology. Heliyon, 7(6). e07301. (2021).

Adane, T. et al. Response surface methodology as a statistical tool for optimization of removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution by Teff (Eragrostis teff) husk activated carbon. Appl. Water Sci. 10, 1–13 (2020).

Foo, K. & Hameed, B. Factors affecting the carbon yield and adsorption capability of the mangosteen Peel activated carbon prepared by microwave assisted K2CO3 activation. Chem. Eng. J. 180, 66–74 (2012).

Abd Rashid, R. et al. FeCl3-activated carbon developed from coconut leaves: characterization and application for methylene blue removal. Sains Malaysiana. 47 (3), 603–610 (2018).

Emirie, M. Removal of chromium hexavalent (Cr (VI) from aqueous solution using activated carbon prepared from prosopis Juliflora plant and find the optimal operating condition for adsorption process. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa. (2015).

O’Dell, J. W. The determination of chemical oxygen demand by semi-automated colorimetry. In Methods for the Determination of Metals in Environmental Samples; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. :509–521 (1996).

Khader, E. H. et al. Removal of organic pollutants from produced water by batch adsorption treatment. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 24 (2), 713–720 (2022).

Nure, J. F. et al. COD and colour removal from molasses spent wash using activated carbon produced from Bagasse fly Ash of Matahara sugar factory, Oromiya region, Ethiopia. Water Sa. 43 (3), 470–479 (2017).

Yirdaw, G. et al. Application of Noug (Guizotia abyssinica cass.) stalk activated carbon for the removal of lead (II) ions from aqueous solutions. Heliyon, 10(9). e30532. (2024).

Mohammed, R. A. et al. Optimization of response surface methodology for removal of cadmium ions from wastewater using low cost materials. J. Ecol. Eng., 24(8). 146–56. (2023).

Dawood, D. S. et al. Optimization of Pb (II) ion removal from synthetic wastewater using dead (Chlorophyta) macroalgae: prediction by RSM method. Iraqi J. Chem. Petroleum Eng. 25 (1), 129–140 (2024).

Mohammed, N. A. et al. Synthesis, characterization of FeNi3@ SiO2@ CuS for enhance solar photocatalytic degradation of atrazine herbicides: application of RSM. Results Surf. Interfaces. 16, 100253 (2024).

Ya’acob, A., Zainol, N. & Aziz, N. H. Application of response surface methodology for COD and ammonia removal from municipal wastewater treatment plant using acclimatized mixed culture. Heliyon, 8(6). e09685. (2022).

Commission, C. A. General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and feed. CODEX STAN 193–1995 (Codex Alimentarius Commission, 2016).

Nguegang, B., Sibanda, T. & Tekere, M. Cultivable bacterial diversity, physicochemical profiles, and toxicity determination of car wash effluents. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191 (8), 478 (2019).

Fayed, M. et al. Treatability study of car wash wastewater using upgraded physical technique with sustainable flocculant. Sustainability 15 (11), 8581 (2023).

Sarmadi, M. et al. Efficient technologies for carwash wastewater treatment: a systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (28), 34823–34839 (2020).

Elayadi, F. et al. Experimental and modeling studies of the removal of phenolic compounds from Olive mill wastewater by adsorption on sugarcane Bagasse. Environ. Challenges. 4, 100184 (2021).

Issabayeva, G., Aroua, M. K. & Sulaiman, N. M. N. Removal of lead from aqueous solutions on palm shell activated carbon. Bioresour. Technol. 97 (18), 2350–2355 (2006).

Mortada, W. I. et al. Effective and low-cost adsorption procedure for removing chemical oxygen demand from wastewater using chemically activated carbon derived from rice husk. Separations 10 (1), 43 (2023).

Ketsela, G., Animen, Z. & Talema, A. Adsorption of lead (II), Cobalt (II) and iron (II) from aqueous solution by activated carbon prepared from white lupine (GIBITO) HSUK. J. Thermodyn. Catal., 11(2). 1–8. (2020).

Mousavi, H. et al. Removal of lead from aqueous solution using waste tire rubber Ash as an adsorbent. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 27 (1), 79–87 (2010).

Hafshejani, L. D. et al. Removal of zinc and lead from aqueous solution by nanostructured Cedar leaf Ash as biosorbent. J. Mol. Liq. 211, 448–456 (2015).

Bansode, R. et al. Pecan shell-based granular activated carbon for treatment of chemical oxygen demand (COD) in municipal wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 94 (2), 129–135 (2004).

Tekere, M., Sibanda, T. & Maphangwa, K. W. An assessment of the physicochemical properties and toxicity potential of carwash effluents from professional carwash outlets in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 11876–11884 (2016).

Ogunleye, O. O., Ajala, M. A. & Agarry, S. E. Evaluation of biosorptive capacity of banana (Musa paradisiaca) stalk for lead (II) removal from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Prot. 5 (15), 1451 (2014).

Act, E. Standards for effluent discharge regulations. Gen. Notice, 44. 2003. (2002).

Kadirvelu, K. et al. Activated carbon from an agricultural by-product, for the treatment of dyeing industry wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 74 (3), 263–265 (2000).

Shukla, S. K. et al. Low-cost activated carbon production from organic waste and its utilization for wastewater treatment. Appl. Water Sci. 10 (2), 62 (2020).