Abstract

Wound healing is a major clinical challenge and regenerative medicine and tissue engineering suggest new ways to overcome such problems. The cell imprinting method can provide cues that regulate cell function or modulate stem cell differentiation into different lineages. In this study, the rabbit keratinocyte-imprinted polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate (KiPDMS) was made and associated with adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), keratinocytes, and collagen scaffold, provided various treatments. After evaluating ADSCs’ differentiation into keratinocytes by qPCR and immunocytochemistry techniques, different treatments were implanted in a rabbit ear, histopathological analysis was performed on measuring the epidermal thickness and neovascularization. The histopathological analysis revealed that treated groups increased epidermal thickness (~ 139% up to ~ 998%) and neovascularization (vessel count /mm2, ~ 111% to ~ 301%) compared to the control group. Collagen scaffolds stimulated re-epithelialization, and implanting ADSCs with or without other factors enhanced its effect. Adding KiPDMS significantly improved re-epithelialization and neovascularization, especially in combination with differentiated keratinocytes. The complete treatment, consisting of all cellular and non-cellular stimulating factors, associated with a significant improvements in re-epithelialization and neovascularization compared with other treatments, including collagen scaffold and some other factors alone or together. These findings suggest that each treatment may have potential applications depending on the medical conditions, particularly in situations where cellular factors are limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wound healing is one of the most important and interesting research topics, attracting significant funding to improve treatment methods1. Despite various clinical approaches, different disease stages may confront patients with various risks2. Common clinical wound treatments, autografts, allografts, and xenografts, often cause serious problems such as infection, immune response, and graft rejection, and they also encounter limited donor skin availability, especially for extensive burn injuries3,4. Although growth factors have been applied to promote healing5 and cell differentiation and proliferation, they can raise the risk of cancer or abnormal tissue formation6.

Wound dressings support skin repair and they are classified as traditional and modern, both aiming to promote healing. Some drawbacks of traditional wound dressings are wound drying and incomplete healing7. Modern dressings are designed to mimic natural skin by enhancing cell migration, angiogenesis, and regeneration of both the epidermis and dermis. Despite these advancements, modern dressings still suffer from limitations, including weak mechanical strength, drainage of the wound area, limited flexibility, high cost, difficult application, and disposability5.

Wound healing involves cell migration, proliferation, and various molecular and physicochemical events8. Epidermal regeneration is particularly critical, as it influences cell signaling and migration9,10. Since stem cell niches in the dermis and epidermis are key for regeneration, any damage can impair healing8. The complexity of skin structure and reduced self-renewal after injury especially make skin regeneration challenging11,12,13.

Keratinocytes are epidermal cells that produce necessary biomolecules during re-epithelialization, influence angiogenesis, their implantation in the wound site improves the wound healing14,15,16, and epidermal thickening reflects re-epithelialization via keratinocytes activity17,18. During wound healing, collagen deposition is necessary, and keratinocytes and fibroblasts should migrate to the wound site19. Also, some essential factors for wound healing are secreted owing to keratinocyte-fibroblast crosstalk20,21. Because keratinocytes affect the re-epithelialization of damaged skin22,23, any epidermal damage, the loss of or failure to replace keratinocytes lead to imperfect wound healing8. However, isolating keratinocytes from the skin and transplanting them to the wound area for skin repair encounter some limitations. First, a part of the patient’s skin tissue must be surgically removed to isolate keratinocytes that causes morbidity for the patient. Second, it is difficult to find the right time for cell passaging and produce an ideal population of keratinocytes for transplantation. Finally, movement at the site of cell transplantation in a short time after transplantation may cause damage to cells8,24,25. Due to ability of stem cells to self-renew and differentiate26,27, their differentiation into the keratinocyte lineage, either by using chemical stimuli28 or by co-cultivation with keratinocyte cells29,30,31, represents common strategies to obtain differentiated cells outside the body. However, high efficiency and performance, safety, and affordability are among the most challenging considerations of stem cell differentiation in the laboratory32,33.

Collagen comprises about 50–90% of the ECM integument34, consists of about 80% of collagen type I, and provides the structure and stiffness of dermal tissue35. The wound fibroblasts, different from the normal fibroblast of healthy mesenchymal tissue, produce the true extracellular matrix (ECM) of the wound36. The ECM is a scaffold support that provides suitable binding sites for specific cell surface receptors, facilitating the migration of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells35. Also, the RGD sites in collagens may be exposed by wounding that facilitates cellular interaction with damaged ECM37. So, the structural features of collagen and limited immunologic rejection38 make it favorable scaffold for wound healing.

Chemical and biochemical stimuli such as cytokines and growth factors can affect the behavior of mature cells and the differentiation of stem cells towards specific lineages in vitro and in vivo39,40. However, the high cost, short half-life, and potentially harmful effects can limit their efficiency41. Conversely, the physical characteristics of the surface to which cells adhere are constant signals that can affect proliferation40,42, migration, and cell differentiation42,43. Thus, engineered substrates with specific surface ligands or topographies are promising for regulating stem cell behavior and differentiation40,42.

Geometrically imprinted surfaces affect stem cell behavior by mimicking cell topographies, regulating gene expression, and directing lineage-specific differentiation through biophysical cues44,45,46,47. PDMS is a widely used non-toxic polymer for creating culture or differentiation substrates based on cell topography due to its easy and accurate micro/nanoscale molding, low chemical reactivity, and tunable physicomechanical properties48,49. By imprinting the target cell’s surface onto PDMS, stem cells can be directed toward specific lineages, as shown in studies on chondrocytes50,51, tenocytes52, osteoblasts53, cardiomyocyte48, and Schwann cells54.

Considering the improvement in tissue cellular and molecular pathways, the introduction of a new type of wound dressings can be possible by developing a suitable substrate. Although several studies have used PDMS substrates to investigate the behavior of skin cells55,56,57,58 or differentiate stem cells into the keratinocyte lineage42,57,59, keratinocyte-imprinted substrates have not been used so far for direct skin wound treatment and proper repair of epidermal tissue. This study is focused on the design and evaluation of a new type of wound dressing based on the cell imprinting approach in which a keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrate (KiPDMS) is made for differentiating stem cells into keratinocytes. Then the ability of KiPDMS to regenerate skin tissue under different conditions is evaluated in an animal model. These findings may facilitate further research into the potential clinical applications of PDMS-based cell patterns and their possible contribution to patient care.

Results

Characterization of ADSCs cultured on bare PDMS and KiPDMS substrates

Figure 1a,e show the morphologies of isolated rabbit ADSCs and keratinocytes, respectively. Also, Fig. 1b and f display the SEM images of non-patterned (bare) and keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS (KiPDMS), respectively, where the relatively surface smoothness and the roughness caused by the cell pattern are evident.

(a) the morphology of isolated rabbit ADSCs, (b) the SEM image of the surface of bare PDMS, (c,d) the morphology of ADSCs cultured on the non-patterned (bare) PDMS after 4 days, (e) the morphology of isolated rabbit keratinocytes, (f) the SEM image of the surface of keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS (KiPDMS), (g,h) the morphology of ADSCs cultured on the KiPDMS after 4 days.

After 4-day culturing on the substrates, the morphologies of ADSCs changed depending on the characteristics of the underlying substrate. The spindle-like and elongated morphology of ADSCs on the smooth substrate (Figs. 1c and 1d) changed to small and polyhedral morphology by culturing on the KiPDMS (Figs. 1g and 1h), caused by trapping in the cavities of keratinocytes’ footprints.

Figure 2 shows the fluorescence images of stained ADSCs cultured in the culture plate, confirming high expression of collagen type I (Fig. 2a) and no expression of keratinocyte-specific involucrin protein (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c shows the ADSCs’ nuclei stained by DAPI and the spindle-like morphology of ADSCs is obvious in Figs. 2a and merged image (Fig. 2d). According to Figs. 2e, 2f, 2g, 2h, 2i, flow cytometry analysis revealed that 90.9% of the isolated rabbit cells exhibited mesenchymal stem cell characteristics, with positive expression of CD90 (97.8%) and CD105 (93.2%), and negative expression of CD34 (2.31%) and CD45 (0.79%).

Immunofluorescence staining of (a) ADSC’s collagen type I, (b) ADSC’s keratinocyte-specific involucrin protein, (c) ADSC’s nuclei by DAPI, (d) ADSC’s merged image (Scale bar = 50 μm). (e) Cells were gated based on FSC/SSC to determine the study population. Rabbit ADSCs were positive for (f) CD90 and (g) CD105 markers, and negative for (h) CD34 and (i) CD45 hematopoietic markers. Percentages in each quadrant represent the proportion of positive cells among the total gated population. The isotype controls are indicated by dotted lines. ADSCs expressed mesenchymal stem cell markers (CD90, CD105), while showing no expression of hematopoietic (CD34) and pan-leukocyte markers (CD45), in comparison to their isotype controls.

In vitro evaluations of keratinocyte-oriented differentiation of ADSCs

The differentiation capacity of KiPDMS was evaluated by qPCR and immunocytochemistry. According to Fig. 3, 14-day culturing ADSCs on the KiPDMS substrate caused significant downregulation in Collagen type I (about 13 fold, P < 0.0001) and upregulation in Involucrin (about 5 fold, P < 0.0001) and Cytokeratin10 (about 2 fold, P < 0.0001) genes compared with ADSCs cultured in culture plate as control, which were in agreement with the previous study44.

Figure 4 shows the immunocytochemical staining of keratinocyte’s specific proteins and the circle-shaped collagen scaffold and keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrate. After 14-day culturing on KiPDMS substrate, keratinocyte-like ADSCs expressed pankeratin protein (red color in Figs. 4ia and 4ic) and involucrin (green color in Figs. 4id and 4if). The DAPI-stained nuclei of keratinocyte-like ADSCs are seen in Figs. 4ib, 4ie, and merged images. Also, primary isolated keratinocytes were specifically characterized by immunostaining for pankeratin (red color in Figs. 4iia and 4iic) and involucrin (green color in Figs. 4iid and 4iif). Also, their nuclei were stained by DAPI (Figs. 4iib and 4iie). Figure 4iii shows the KiPDMS and collagen scaffold, which were cut into 6 mm discs using a biopsy punch.

(i) Immunostaining of keratinocyte markers in primary keratinocyte in ADSCs cultured on the keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS after 14 days (Scale bar = 25 μm) (ii) Immunostaining of keratinocyte markers in primary isolated keratinocyte (Scale bar = 25 μm) (iii) Pattern substrate (left) and collagen scaffold (right) were cut into 6 mm discs using a biopsy punch (Scale bar = 3 mm). In the immunostaining images, pankeratin is in red, involucrin is in green, and nuclei by DAPI are in blue.

In vivo evaluations of wound healing capacity

Histopathological analysis

Figure 5 includes the H&E-stained sections of different treatment groups in which diverse histological elements are determined. Furthermore, Fig. 6 shows the thickness of epidermis and vessel density (vessel count per mm2).

Figure 5a shows the normal structure of rabbit ear skin, vessels, and the normal epidermis. According to Figs. 5 and 6i, regeneration of the epidermal layer in the treatment and control groups occurred after 14 days and its epidermis thickness increased significantly in the treatment groups compared with the control group (Fig. 5b) from ~ 139% for the Col group (P = 0.0012, Fig. 5c) to ~ 995% for the ColAPdK group (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5h). According to Fig. 6ii, the vessel density of all treatment groups increased significantly compared with the control group from ~ 111% for the ColAP group (Fig. 5f) to ~ 301% for the ColAPdK group (Fig. 5h). Seeding ADSCs on the surface of the collagen scaffold in the ColA group (Fig. 5d) increased the thickness of the epidermal layer by about 14% compared with the Col group (Fig. 5c), but it was not significant. Conversely, putting the keratinocyte pattern (KiPDMS) on the collagen scaffold in the ColP group (Fig. 5e) significantly increased the epidermis thickness compared with the Col and ColA groups (207.30% and 170.13%, respectively P < 0.0001). Combining the effect of stem cell and KiPDMS in the ColAP group (Fig. 5f) significantly improved the epidermis thickness by 228.92% compared with the ColA group (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5d) and by 21.76% compared with the ColP group (P = 0.0232, Fig. 5e). Although the vascular density of the ColA group (Fig. 5d) slightly higher than those of the Col, ColAP, and ColP groups (4.36%, 8.82%, and 5.79% respectively), the vascular densities of the mentioned groups were not significant compared with each other.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed histopathological studies on wound healing on the 14th day post-implantation (a) Normal, (b) Control, (c) Col, (d) ColA, (e) ColP, (f) ColAP, (g) ColPdK, (h) ColAPdK. (E: epidermis – F: fibroblast – C: collagen – Co: chondrocyte – NV: new vessel) (Scale bar = 100 μm). The red outlined regions in each panel indicate the specific areas selected for histological quantification, including epidermal thickness and vessel density measurements.

(i) Epidermis thickness after 14-day treatment, presented as mean ± SEM. (ii) Vessel density (vessel count per mm2) after 14-day treatment, presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001., (iii) Arrow indicates the region used for vessel density measurement; consistent anatomical sites were used for all groups (Scale bar = 100 μm).

The differentiation of ADSCs into keratinocyte lineage and using KiPDMS-keratinocyte combination on the collagen scaffold in the ColPdK group (Fig. 5g) increased the epidermis thickness compared with pattern alone (ColP group, Fig. 5e) by 11.25%, but it was not significant compared with the ColAP group (Fig. 5f). In contrast, the effect of the ColPdK group (Fig. 5g) on neovascularization was significant (P < 0.0001) compared with other treatment groups except ColAPdK (Fig. 5h) and it could increase vessel density by 31–42.5% (37.12% on average). The regeneration of the epidermal layer by ColAPdK treatment (Fig. 5h) was very considerable and significant compared with all groups (Fig. 6i) and the epidermis thickness increased by 22.57% and 34.16%, respectively compared with the ColAP (Fig. 5f) and ColPdK (Fig. 5g) groups. In addition, ColAPdK treatment significantly improved neovascularization (Fig. 6ii, P < 0.0001) compared with other treatment groups and increased vessel density by 34–90% (73.36% on average). Despite the vital role of collagen deposition during wound healing, rare collagen bundles were determined in the control group after 14 days. According to Fig. 5, deposited collagen was a very thin and barely visible layer in the control sample, while the bundles of collagen type I were visible in the area close to the epidermis in the treated samples. ColAPdK group had the highest level of collagen bundles all over the dermis after 14 days. Accumulation of fibroblastic cells in the dermis in all treated samples was remarkable and easily visible compared with the control sample.

Immunohistochemical analysis of wound healing

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was used to confirm the epidermal layer by detecting involucrin as a keratinocyte-specific protein after 14 days. ColAPdK treatment showed higher involucrin staining intensity compared with the control group (Fig. 7).

Epithelial regeneration in full-thickness skin wounds after 14-day treatment. Normal: Normal tissue, Control: untreated wound, and ColAPdK: wound treated by collagen-based scaffold + ADSC + KiPDMS + differentiated keratinocyte. ADSC and KiPDMS stand for adipose-derived stem cell and keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrate (Scale bar = 100 μm).

Discussion

Wound healing remains a major clinical challenge and the difficulties in managing the function of stem cells and their differentiation into keratinocytes have limited their therapeutic applications in the wound area60,61. Therefore, different methods such as using surface topographies to induce the differentiation of stem cells into the epidermal lineage62 have been attended.

In this study, KiPDMS (keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS) was used to induce differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) into keratinocytes. Collagen scaffolds with/without ADSCs and KiPDMS were applied to the skin wounds in the rabbit’s ears. KiPDMS could direct ADSCs toward epidermal lineage without any epidermal differentiation-inducing growth factor. All collagen-based treatments improved re-epithelialization and neovascularization compared with the untreated control group. KiPDMS significantly enhanced re-epithelialization, and ADSCs on collagen increased epithelial thickness. Combined treatments consisting of all effective cellular and non-cellular factors showed significant epidermal regeneration and angiogenesis.

The skin is a complex organ made up of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, and the subcutaneous tissue is sometimes very thin. Despite scarless healing in fetal skin, wound healing in adult mammals associates with scar formation without any skin appendages63. Among the different stages of wound healing, the regeneration of the epidermis is more essential because it plays an important role in cell migration and signaling for wound healing9. Although skin regeneration requires restoration of multiple layers, our assessments primarily reflected changes in the epidermal and upper dermal compartments. Wound healing is a highly orchestrated and complex process involving various stages among which epidermal regeneration is particularly critical, as it significantly influences cell migration and signaling pathways9,10. Importantly, the evaluation of angiogenesis and epidermal thickness in wound healing confirmed re-epithelialization, keratinocyte activity during repair, granulation tissue formation, and dermal maturation, together reflecting the overall restoration of skin layers during wound healing process.

Normal wound healing consists of three overlapped phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling18,61,64. Inflammation (prolonged for ~ 7 days) involves hemostasis, bacterial clearance, increased vascular permeability, and cell migration60,61. During proliferation (prolonged for ~ 7–14 days), glycosaminoglycans are secreted and re-epithelialization begins62. Following this stage, the remodeling and maturation phase start and can last from several weeks to several months during which the strength of newly formed skin increases and 80% of original strength is obtained after 11–14 weeks16,17,62.

Previous studies using rabbit, rat and other preclinical models65,66,67 have provided valuable insights into tissue engineering strategies for skin regeneration, highlighting the importance of multi-tissue interactions in achieving effective wound healing. The healing process, structure65, and response to ageing and different topical drugs67 in rabbits is similar to human skin, and allows multiple wounds per animal, providing a suitable model to assess multi-layer wound regeneration, including epidermis and dermis65,67. Also, multiple wounds can be created on each rabbit, allowing the comparison of different treatments within the same animal and reducing required number of animals and inter-individual variability65. So, rabbits have been used as excellent models to evaluate preclinical treatments for human applications. Although interspecies differences may limit direct extrapolation to humans and the translational relevance of our findings should be considered cautiously, using biocompatible collagen scaffold, keratinocyte-based patterns, and mesenchymal stem cells supports potential clinical translation. A 6 mm wound size was chosen to ensure consistent results, reduce animal distress, and allow controlled monitoring. However, the modular and scalable design of our presented wound dressings are required for adaptation to larger wounds, and the effectiveness in larger or chronic wounds should be evaluated.

In vitro experiments (flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining) confirmed the mesenchymal phenotype of isolated ADSCs (Fig. 2). Although the flow cytometry alone did not fully capture the differentiation potential of stem cells and multipotency assessment could provide stronger evidence, the differentiation of ADSCs toward keratinocytes on the cell-imprinted PDMS substrate (KiPDMS) was confirmed by immunostaining and qPCR analyses. After two weeks, molecular analyses showed a reduced expression of Collagen type I and an increase in involucrin and cytokeratin10 expressions (Fig. 3), and keratinocyte-specific protein expression was confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4).

After 14 days, the control group showed poor epidermal regeneration with a thin epidermis, while the Col group (collagen scaffold) significantly enhanced epidermal thickness (~ 139%) and neovascularization (~ 125%) (Figs. 5c and 6). Despite less specific, angiogenesis was assessed using H&E staining, which provides suitable information on vessel density, has been widely accepted in scientific research68, and our approach was validated by blinded pathological assessment for consistent vessel counting. However, vessel-specific immunohistochemical (IHC) staining using suitable markers such as CD31 is widely recognized as a specific and reliable method for angiogenesis assessment, and should be integrated in IHC for more robust vascular characterization. Previous in vivo studies in rat wound models showed that collagen scaffold replicates the properties of the ECM, enhances cell adhesion and proliferation, stimulates new matrix synthesis, and accelerates wound healing66. Looking at the three phases of wound healing, neovascularization (through angiogenesis or vasculogenesis62 is usually considered in the proliferative phase, but many angiogenic signaling pathways are supported by the inflammatory phase64. These features contribute to increased angiogenesis and improved epidermal regeneration, indicating re-epithelialization and the development of mature dermal tissue in the repaired wound area. These findings suggest that collagen scaffolds may serve not only as structural matrices but also as modulators in the wound healing process. Therefore, collagen scaffolds were used in all treatment groups, enhancing re-epithelialization and neovascularization. Collagen type I and fibrin support capillary morphogenesis by providing a substrate for endothelial tube formation and supporting vascular differentiation26,69. Fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and keratinocytes interact with collagen and laminin through integrins, enhanced by RGD sites in collagen type I35,37,70. Following injury, epithelial cells migrate to form a single cellular layer and cover the defect15, while granulation tissue fills the area between the bottom and the edges of the wound23 and provides a template for keratinocyte migration and re-epithelialization13,17,19. These studies support the role of collagen type I in cell adhesion, migration, and re-epithelialization during wound healing.

Seeding ADSCs on collagen scaffolds (ColA group, Figs. 5d and 6) improved re-epithelialization and neovascularization, which might be due to the positive effect of collagen in activating different molecular pathways28 and promoting angiogenesis by secreting pro-angiogenic bioactive molecules30. By considering the keratinocyte migration from the wound edges, stem cell implantation on the surface of ColA group increased the neoepidermis thickness compared to neovascularization (~ 14% and 4%, respectively, Fig. 6). The differentiation of stem cells into endothelial cells may occur under specific conditions including exposure to different growth factors (e.g., VEGF), co-culturing with an ECM, implementing mechanical stimuli (e.g., shear stress), and preconditioning in a hypoxic environment71. Fibroblasts are rapidly recruited to the wound site in response to injury-associated signals72,73, and their collagen-mediated migration74 facilitates dermal repair. They secrete factors like TGF-β73 and VEGF, promoting stem cell differentiation into myofibroblasts and enhancing angiogenesis in vivo75. However, the contribution of stem cells to angiogenesis has been reported to be highly variable. Hamou et al. reported that GFP-labeled bone marrow-derived stem cells contributed ~ 12% of endothelial cells in ischemic wounds76, while other studies noted endothelial contributions ranging from 0.1 to 13%77,78. Despite many reports on the better angiogenesis and re-epithelialization promoted by mesenchymal stem cells76,77,78,79, most studies present these effects collectively80,81,82 and do not distinguish their preferential role in epidermal regeneration versus vascularization.

Quantitative analysis revealed that ColP increased epidermal thickness compared with Col and ColA (Figs. 5c–e and 6i), suggesting that KiPDMS primarily influence epithelial regeneration. The function of isolated stem cells is disturbed due to the loss of extracellular matrix and they require numerous cell-ECM signals and cell-cell communication to obtain their physiological properties34. The geometric shape of the tissues and the geometric shapes or topographies on the substrates are sensed by the cells and affect their positioning and behavior35,36. Considering the sensitivity of cells and their reaction to their niche, substrates with appropriate microstructures guide targeted cell migration and support wound closure37,38. Previous studies have shown that stem cells can reminisce about their native niches when they are seeded on the cell-imprinted substrates. So, controlling the growth, physiology, and development of cells on the cell patterns is highly efficient for stem cell differentiation83. Consequently, KiPDMS promoted keratinocyte migration, proliferation, and epithelial regeneration, indicating that defined keratinocyte imprinting can improve re-epithelialization. Since ColP treatment did not differ from Col and ColA in improving angiogenesis, physical signals caused by the KiPDMS might dominantly contribute to re-epithelialization.

ColAP significantly enhanced epidermal thickness (Figs. 5f and 6i), confirming the positive effects of stem cells and keratinocyte-imprinted substrate. Indeed, receiving keratinocyte-differentiating signals from KiPDMS might induce stem cell differentiation and significantly improved the regeneration of the epidermal layer compared to the treatment without biological factors (Col group) or containing one of the physical (ColP group) or biological stimuli (ColA group). It might be related to the co-culture effect between seeded ADSCs and migrating keratinocytes from wound edges on the keratinocyte proliferation. Stem cell-derived paracrine factors promote keratinocyte behavior. It has been observed that the culture medium obtained from stem cells increases the migration and proliferation of immortalized human keratinocytes in vitro84. Moreover, co-culturing ADSCs and dermal fibroblasts with keratinocytes on collagen substrates promotes migration, proliferation, adhesion, and thicker epidermis after 14 days85. Also, previous study on mice skin wound showed that stem cell transplantation enhanced epidermal regeneration after 14 days through increased keratinocyte proliferation86. Although ADSCs can influence angiogenesis71, the dominant effect of transplanted ADSCs in ColAP was on epithelial regeneration. Interaction between seeded ADSCs and migrating keratinocytes from wound edges likely promoted keratinocyte proliferation more than new vessel formation, demonstrating that the integration of both physical and biological cues might promote re-epithelialization.

Epidermal regeneration in ColPdK was not significantly different from ColAP (Fig. 5f and 5g, and 6i) and lower re-epithelialization capacity might be due to the absence of stem cells, resulting in a decreased cell division and differentiation. On the contrary, angiogenesis was significantly enhanced in ColPdK treatment (Fig. 6ii) compared with other treatment groups except ColAPdK likely due to the keratinocyte secretion of primary VEGF-A isoform19,36, and TGF-β22 by keratinocyte, stimulating vascular permeability and endothelial proliferation36,87.

Considering all factors in ColAPdK (keratinocyte imprinting, differentiated keratinocytes, and ADSCs) the wound received diverse physical and biological cues, creating a favorable microenvironment for enhanced re-epithelialization and neovascularization (Figs. 5h and 6, and 7). Significantly higher epidermal thickness and vessel density than those of other groups suggests that the integration of physical and biological signals acts synergistically to enhance wound healing. Keratinocytes release angiogenic factors, and their absence in the wound healing process can limit vascular formation9,22,23. Also, co-culturing stem cells with keratinocytes exposes ADSCs to growth factors secreted by keratinocytes, promoting their transdifferentiation toward keratinocyte lineage31,88. Despite a single-layered keratinocytes migrating toward the wound center, multiple-layered (stratified) keratinocytes near wound edges contribute to neoepidermis and dermoepidermal junctions22,35. Moreover, basal epidermal stem cells divide into self-renewing or transit-amplifying cells89, some of which forms proliferation units54,81 and commit to differentiate and migrate suprabasally towards the epidermis surface89. Immunohistochemistry qualitatively confirmed keratinocyte presence in regenerated epidermis, with higher involucrin staining in ColAPdK compared with control, which can be readily observed (Fig. 7). Although immunohistochemistry analyses for all treatment groups would provide a more comprehensive overview, IHC was performed only on selected groups (untreated controls, normal skin, and ColAPdk) because they could represent the full range of treatment, and complementary histological assessment across the remaining groups revealed clear differences, supporting the main findings. Future complete IHC analysis for all conditions will extend comparative insights. Increased epidermal thickness, enhanced angiogenesis, and the presence of stratified keratinocytes in ColAPdk (Fig. 7) suggest improvements in re-epithelialization, keratinocyte activity during repair, granulation tissue formation, and dermal maturation, and reflect relatively appropriate restoration of skin architecture.

Controlling cellular migration and stem cell fate through cell imprinting emerges as a promising approach for wound healing. Nevertheless, further studies are required to fully understand the fundamental principles and the mechanisms by which cell-imprinted substrates guide stem cell differentiation. The keratinocyte-imprinted construct not only provided a biocompatible scaffold, but also supported delivering keratinocyte-like cells to the wound site potentially accelerated healing. Analyzing secreted factors could clarify the mechanisms behind enhanced healing and angiogenesis. Future work is needed to provide the profile of paracrine mediators from differentiated keratinocytes, ADSCs, collagen scaffold, KiPDMS, and their combinations for better understanding regenerative effects. It is essential to evaluate the designed KiPDMS-included wound dressing from different aspects in the future to prove its medical performance and adaptation.

Conclusion

Wound healing is one of the serious medical challenges and many efforts have been made to find effective solutions such as modern dressings. In this study, we made a keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrate (KiPDMS) to differentiate ADSCs into keratinocyte lineage. Also, we provided composite KiPDMS-collagen scaffold treatments with and without ADSCs and keratinocytes to evaluate the effects of different physical and cellular factors on re-epithelialization and angiogenesis in vivo. Collagen scaffold increased the thickness of the epidermal layer, and using KiPDMS alone or in combination with ADSCs significantly enhanced re-epithelialization in our model. The KiPDMS–keratinocyte combination on the collagen scaffold promoted both re-epithelialization and angiogenesis. By incorporating biological (stem cells and keratinocytes) and non-biological (collagen type I and KiPDMS) components, this approach provides potential benefits for the therapeutic goals of the study. Taken together, the designed keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrate as a wound dressing may combine the known features of PDMS (low cost, biocompatibility, and ease of use) with support for cell migration, re-epithelialization, and neovascularization, although further studies are warranted to confirm these benefits.

Materials and methods

All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Ethical considerations

The animal experiments were approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Tehran University, and the ethical committee of Pasteur Institute of Iran (IR.PII.REC.1397.022). Also, the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) were considered to perform all experiments in this study. Figure 8 illustrates the various steps of the study, including stem cell isolation and differentiation, KiPDMS preparation, and the creation and treatment of animal model.

Isolation of rabbit epidermal keratinocyte

The newborn New Zealand white rabbit was sacrificed by administering 100 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital and the dorsal skin was taken. The pieces of skin were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 300 U/ml penicillin (3X) and 300 µg/ml streptomycin (3X) (Pen/Strep) (Gibco-BRL, Germany).The skin was cut into 1 × 1 cm2 pieces and incubated in shaking 4 mg/ml of Dispase (Sigma, USA) at 4 °C overnight. The epidermis was separated from the dermal layer and incubated in trypsin (0.25%) for 25 min. After centrifugation for 5 min, the cells were suspended in keratinocytes culture medium consisting of 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum)-supplemented DMEM/F12 culture medium, 10 ng/ml EGF (Sigma, USA), 0.4 µg/ml hydrocortisone, 0.4 µg/ml epinephrine, 5 µg/ml insulin, 10 ng/ml prostaglandin E2 (all from Gibco-BRL, Germany), 1X Pen/Strep. Then keratinocytes were seeded in the 12-well culture plate pre-coated with collagen type I (100 µg/ml, NanoZist Arayeh, Iran).

Isolation and characterization of rabbit adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs)

To isolate ADSCs, a New Zealand white rabbit was anesthetized by injection of 30 ml/kg ketamine hydrochloride and 5 ml/kg xylazine hydrochloride (Bremer Lanka, Germany). The adipose tissue was obtained from the scapular subcutaneous of one rabbit (average weight, 3 kg), and the adipose tissue was extracted surgically under ethical considerations, and washed three times in the DMEM/F12 containing 3X Pen/Strep. After cutting into small pieces, the adipose tissue was digested by collagenase type I (0.1% (w/v) in DMEM/F12, Gibco, USA) at 37 °C for one hour under shaking. After centrifuging the obtained mixture at 1300 g for 10 min to remove undigested tissues, the supernatant was disposed and sedimentary cells were cultured into the 6-well culture plate in the 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM/F12 (complete culture medium) under common culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). The culture medium was replaced every 2 days to reach 80–90% confluence. Flow cytometry was performed to characterize rabbit ADSCs at passage 2. Cells (1 × 10⁶) were stained at 4 °C for 30 min in darkness with the following antibodies: CD90 (clone Thy1, Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam, UK, ab225544; 1:50), CD105 (clone SN6, PE, BioLegend, USA, 323205; 1:50), CD34 (clone QBEnd/10, APC, BD Biosciences, USA, 560941; 1:50), and CD45 (clone OX-1, APC, Bio-Rad, USA, MCA808A647; 1:100). FMO and isotype controls were included. Data were acquired using a BD FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, USA) and analyzed with FlowJo v7.6.1 (TreeStar Inc., USA).

Manufacturing non-patterned and keratinocyte-imprinted PDMS substrates (KiPDMS)

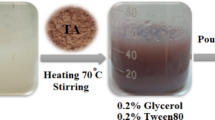

Non-patterned (bare) polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate was made by blending the curing agent and PDMS base polymer (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) at a ratio of 1:10, purring the mixture in a 12-well culture plate and incubating for 48 h at 37 °C. After reaching 80–90% confluence, the isolated primary keratinocytes were fixed using glutaraldehyde solution (4% (w/v) in PBS) and washed with distilled water three times. To make the keratinocyte-imprinted substrate, a curing agent/base polymer mixture at a ratio of 1:10 was poured onto the fixed keratinocytes and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. The final KiPDMS obtained by peeling off the mold was washed with PBS and 70% ethanol and then rinsed thoroughly with 1 M NaOH solution for 30 min to remove any existing chemicals and residual cell debris, and autoclaved to remove other contaminations.

Characterization of ADSCs cultured on the bare PDMS and KiPDMS

After sterilizing the bare PDMS and KiPDMS by autoclave, ADSCs on the third passage (4 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded on the substrates overnight and 600 µl of complete culture medium was added afterward. To confirm the initial response of ADSCs to their substrates and morphology changes, ADSCs were cultured for 4 days, fixed by glutaraldehyde solution (4% (w/v) in PBS) for 15 min at 25 °C and washed with distilled water three times. Then fixed ADSCs were coated with gold and their morphologies were evaluated by scanning electron microscope (SEM, VEGA3, TESCAN, Czech Republic). In addition, ADSCs cultured in the culture plate were immunostained in terms of collagen type I and involucrin to confirm the lack of expression of keratinocyte-specific proteins.

ADSCs were fixed with paraformaldehyde solution (4% (w/v) in PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 15 min at 25 °C, washed with distilled water three times, and permeabilized by adding Triton X-100 (0.25% (v/v) in distilled water, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 20 min at 25 °C. After exposing to 5% BSA (bovine serum albumin) and incubating for 30 min for blocking, ADSCs were incubated with primary antibody, anti-collagen I rabbit IgG polyclonal (2 µg/ml, Calbiochem, France) in phenol red-free DMEM and containing 0.5% (w/v) BSA) for 45 min at 25 °C. After rinsing thoroughly in phenol red-free DMEM, the cells were incubated with secondary AlexaTM-488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 µg/ml, Thermo Fisher, USA) for 30 min in darkness and washed with phenol red-free DMEM. For involucrin-specific immunostaining, the fixed ADSCs were incubated with an anti-involucrin primary antibody (2 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) at 4 °C overnight and in darkness. Then cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) for 1 h at 25 °C in darkness. After washing with PBS, the nuclei were stained with DAPI (1 µg/ml in PBS, Life Technologies, USA), and fluorescence images were acquired using an Eclipse Ci fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan).

In vitro evaluations of keratinocyte-oriented differentiation of ADSCs and characterization of primary keratinocyte

After sterilizing the KiPDMS by autoclave and culturing ADSCs (4 × 103cells/cm2) on the KiPDMS for 14 days under common culture conditions, some morphological and biological evaluations were carried out. To analyze the expressions of keratinocyte-specific genes in differentiated ADSCs by quantitative real time-PCR (qPCR), total RNAs were extracted after 14 days using FavorPrep Blood/Cultured Cell Total RNA Mini Kit (FAVORGEN, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Then the ratios of 260/230 and 260/280 were detected using an Epoch spectrophotometer (BioTek, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using One-Step RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Finally, qPCR was performed using the StepOne equipment (Applied Biosystems, USA) and SYBR PCR Master Mix (Takara, Japan) for rabbit involucrin, collagen type I, cytokeratin10 as target genes, and GAPDH as reference gene. The gene expressions were calculated by normalizing the Ct values of target genes to those of GAPDH using REST 2009 software (Qiagen Inc.) by considering 3 technical replicates of samples in each group at the significance of 0.05. Table 1 includes the forward and reverse sequences of the genes.

To confirm the expressions of keratinocyte-specific proteins, ADSCs were cultured on the KiPDMS for 14 days and differentiated ADSCs were prepared according to the aforementioned immunostaining method. After fixing, permeabilizing, and blocking, ADSCs were washed with PBS three times and incubated with anti-involucrin (2 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) and anti-pankeratin antibodies (2 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) overnight, at 4 °C, and in darkness. Then cells were incubated with Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (1 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1 µg/ml, Abcam, USA) for 1 h at 25 °C in darkness. Finally, the nuclei were stained with DAPI (1 µg/ml) and fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ci fluorescence microscope (Japan). Primary keratinocytes were cultured for 8 days and characterized with the same method.

Preparation of collagen scaffold

A solution of collagen type I (1% (w/v) in 0.5 M acetic acid) was molded, lyophilized for 2 days, and incubated in a crosslinking solution consisting of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (both concentrations of 20 mM in 85% ethanol) at 4 °C for 24 h. Then crosslinked scaffold was washed several times with pure water, lyophilized for 24 h, and sterilized by gamma rays for future applications.

In vivo evaluations of wound healing capacity

After anesthetizing (30 ml/kg ketamine hydrochloride and 5 ml/kg xylazine hydrochloride) 3 New Zealand white rabbits (3.5–4 kg, the age around 9–10 months old) as mentioned before and under ethical considerations, 8 sections of skin layers (diameter of 6 mm) were created by biopsy punch on their ears and treated according to Table 2, including sample specifications. For each wound, about 50,000 cells/cm² of ADSCs or 40,000 cells/cm² of differentiated keratinocytes were put on their substrates (collagen scaffold and KiPDMS, respectively).

After 14 days post-implantation, animals were sacrificed under ethical considerations for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. For this regard, the rabbit was restrained gently with minimal stress, 100 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital was administered through marginal ear vein, and death was confirmed by cessation of heartbeat and respiration and the absence of reflexes. Tissue samples were taken from the implant sites, fixed in neutral buffered formalin (10%) for 24 h, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned in 5 µm thickness to perform hematoxylin-eosin staining (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). The H&E-stained sections were evaluated using a light microscope for desired issues including re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and the formation of granular tissue. Additionally, to confirm the expression level of involucrin as a specific marker of epidermal regeneration, tissue sections were analyzed by IHC assay. After removing the paraffin, the proteins in tissue sections were blocked by 10% goat serum (1 h, 37 °C, in darkness), incubated in primary involucrin antibody (2 µg/ml) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1 µg/ml) was used (2 h, 37 °C, in darkness). The nuclei were stained by DAPI (1 µg/ml) diluted in PBS + 5% (w/v) BSA for 20 min at 25 °C. Supplementary figure shows the implantation of dressing on the wounds.

Quantification of epidermis layer and vessel density

Epidermal thickness was measured from H&E-stained histological sections. After imaging, a senior pathologist assessed the sections using light microscopy, and measurements were performed in ImageJ software. The scale was calibrated by drawing a line along the scale bar and setting the scale in ImageJ v1.50e. For each sample, four regions of the epidermis were selected, and three lines were drawn from epidermal ridge to the irregular dermal junction per region to measure thickness in micrometers (µm). To reflect data reliability across multiple regions, mean ± SEM was reported instead of SD.

For blood vessel density, the same calibration process was applied. A defined area was selected, and vessels, identified by an expert pathologist, were counted. Density was expressed as the number of vessels per mm².

Statistical analysis

Obtained data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, the homogeneity of variance was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’s tests, and repeated one-way ANOVA analysis followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test at the significance level of 0.05 was performed to compare different animal groups. Additionally, other statistical comparisons were done by one-way ANOVA analysis followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test.

Data availability

Data sets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dong, R. & Guo, B. Smart wound dressings for wound healing. Nano Today. 41, 101290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101290 (2021).

Monika, P., Chandraprabha, M. N., Rangarajan, A. & Waiker, P. V. Chidambara Murthy, K. N. Challenges in healing wound: role of complementary and alternative medicine. Front. Nutr. 8, 791899. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.791899 (2022).

Heo, J. S. et al. Human adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: a key player in wound healing. Tissue Eng. Regen Med. 18, 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-020-00316-x (2021).

Yamamoto, T., Iwase, H., King, T. W., Hara, H. & Cooper, D. K. C. Skin xenotransplantation: historical review and clinical potential. Burns 44, 1738–1749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2018.02.029 (2018).

Dhivya, S., Padma, V. V. & Santhini, E. Wound dressings–a review. BioMedicine 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.7603/s40681-015-0022-9 (2015).

Mitchell, A. C., Briquez, P. S., Hubbell, J. A. & Cochran, J. R. Engineering growth factors for regenerative medicine applications. Acta Biomater. 30, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2015.11.007 (2016).

Ahmad, N. In vitro and in vivo characterization methods for evaluation of modern wound dressings. Pharmaceutics 15, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15010042 (2022).

Ter Horst, B., Chouhan, G., Moiemen, N. S. & Grover, L. M. Advances in keratinocyte delivery in burn wound care. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 123, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2017.06.012 (2018).

Dolivo, D. M. et al. Epidermal potentiation of dermal fibrosis: lessons from occlusion and mucosal healing. Am. J. Pathol. 193, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2023.01.008 (2023).

Lambert, W. C., Cohen, P. J. & Lambert, M. W. Role of the epidermis and other epithelia in wound healing: selected concepts. Clin. Dermatol. 2, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-081X(84)90024-5 (1984).

Cui, H. S. et al. Wound healing potential of low temperature plasma in human primary epidermal keratinocytes. Tissue Eng. Regen Med. 16, 585–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-019-00215-w (2019).

Rad, Z. P., Mokhtari, J. & Abbasi, M. Fabrication and characterization of PCL/zein/gum Arabic electrospun nanocomposite scaffold for skin tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 93, 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2018.08.010 (2018).

Tottoli, E. M. et al. Skin wound healing process and new emerging technologies for skin wound care and regeneration. Pharmaceutics 12, 735–735. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12080735 (2020).

Hameedaldeen, A., Liu, J., Batres, A., Graves, G. S. & Graves, D. T. FOXO1, TGF-β regulation and wound healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 16257–16269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916257 (2014).

Markus Roupé, K., Alberius, P., Schmidtchen, A. & Sørensen, O. E. Gene expression demonstrates increased resilience toward harmful inflammatory stimuli in the proliferating epidermis of human skin wounds. Exp. Dermatol. 19, e329–e332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01038.x (2010).

Zhang, C. et al. FOXO1 differentially regulates both normal and diabetic wound healing. J. Cell. Biol. 209, 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201409032 (2015).

Cerqueira, M. et al. Cell sheet technology-driven re-epithelialization and neovascularization of skin wounds. Acta Biomater. 10, 3145–3155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.006 (2014).

Rousselle, P., Montmasson, M. & Garnier, C. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol. 75–76, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.002 (2019).

Wang, Y. & Graves, D. T. Keratinocyte function in normal and diabetic wounds and modulation by FOXO1. J. Diabetes Res. 3714704 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3714704 (2020).

Amiri, N., Golin, A. P., Jalili, R. B. & Ghahary, A. Roles of cutaneous cell-cell communication in wound healing outcome: an emphasis on keratinocyte‐fibroblast crosstalk. Exp. Dermatol. 31, 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.14516 (2022).

Lai, A., Ghaffari, A., Li, Y. & Ghahary, A. Paracrine regulation of fibroblast aminopeptidase N/CD13 expression by keratinocyte-releasable stratifin. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 3114–3120. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.22666 (2011).

Jeon, H. H. et al. FOXO1 regulates VEGFA expression and promotes angiogenesis in healing wounds. J. Pathol. 245, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.5075 (2018).

Johnson, K. E. & Wilgus, T. A. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the regulation of cutaneous wound repair. Adv. Wound Care. 3, 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2013.0517 (2014).

Auxenfans, C. et al. Cultured autologous keratinocytes in the treatment of large and deep burns: a retrospective study over 15 years. Burns 41, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2014.05.019 (2015).

Sood, R. et al. Cultured epithelial autografts for coverage of large burn wounds in eighty-eight patients: the Indiana university experience. J. Burn Care Res. 31, 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181e4ca29 (2010).

Mathew-Steiner, S. S., Roy, S. & Sen, C. K. Collagen in wound healing. Bioeng 8, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering8050063 (2021).

Naomi, R., Ridzuan, P. M. & Bahari, H. Current insights into collagen type I. Polymers 13, 2642. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13162642 (2021).

Ali, G. & Abdelalim, E. M. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into epidermal keratinocyte-like cells. 3, 101613 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101613 (2022).

Bhowmick, S., Scharnweber, D. & Koul, V. Co-cultivation of keratinocyte-human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) on sericin loaded electrospun nanofibrous composite scaffold (cationic gelatin/hyaluronan/chondroitin sulfate) stimulates epithelial differentiation in hMSCs: in vitro study. Biomaterials 88, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.034 (2016).

Lotfi, M. et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells and keratinocytes co-culture on gelatin/chitosan/β-glycerol phosphate nanoscaffold in skin regeneration. Cell. Biol. Int. 43, 1365–1378. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbin.11119 (2019).

Seo, B. F., Kim, K. J., Kim, M. K. & Rhie, J. W. The effects of human keratinocyte coculture on human adipose-derived stem cells. Int. Wound J. 13, 630–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12335 (2016).

Desgres, M. & Menasche, P. Clinical translation of pluripotent stem cell therapies: challenges and considerations. Cell. Stem Cell. 25, 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.10.001 (2019).

Goldring, C. E. et al. Assessing the safety of stem cell therapeutics. Cell. Stem cell. 8, 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.012 (2011).

Diller, R. B. & Tabor, A. J. The role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in wound healing: a review. Biomimetics 7, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics7030087 (2022).

Li, J., Chen, J. & Kirsner, R. Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 25, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.007 (2007).

Hosgood, G. Stages of wound healing and their clinical relevance. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 36, 667–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.02.006 (2006).

Karamanos, N. K. et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 288, 6850–6912. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15776 (2021).

Ruszczak, Z. Effect of collagen matrices on dermal wound healing. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 55, 1595–1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.003 (2003).

Amidzadeh, Z. et al. Enhancement of keratinocyte growth factor potential in inducing adipose-derived stem cells differentiation into keratinocytes by collagen-targeting. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 26, 5929–5942. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.17619 (2022).

Mahmoudi, M. et al. Cell-imprinted substrates direct the fate of stem cells. ACS Nano. 7, 8379–8384. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn403844q (2013).

Zhang, K., Xiao, X., Wang, X., Fan, Y. & Li, X. Topographical patterning: characteristics of current processing techniques, controllable effects on material properties and co-cultured cell fate, updated applications in tissue engineering, and improvement strategies. J. Mater. Chem. B. 7, 7090–7109. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TB01682A (2019).

Mashinchian, O. et al. Cell-imprinted substrates act as an artificial niche for skin regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 13280–13292. https://doi.org/10.1021/am503045b (2014).

Anderson, H. J., Sahoo, J. K., Ulijn, R. V. & Dalby, M. J. Mesenchymal stem cell fate: applying biomaterials for control of stem cell behavior. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 4, 38. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2016.00038 (2016).

Barroca, N. et al. Electrically polarized PLLA nanofibers as neural tissue engineering scaffolds with improved neuritogenesis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 167, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.03.050 (2018).

Martinez, E., Engel, E., Planell, J. A. & Samitier, J. Effects of artificial micro-and nano-structured surfaces on cell behaviour. Ann. Anat. 191, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2008.05.006 (2009).

Ruiz, S. A. & Chen, C. S. Emergence of patterned stem cell differentiation within multicellular structures. Stem Cells. 26, 2921–2927. https://doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2008-0432 (2008).

Song, W., Lu, H., Kawazoe, N. & Chen, G. Adipogenic differentiation of individual mesenchymal stem cell on different geometric micropatterns. Langmuir 27, 6155–6162. https://doi.org/10.1021/la200487w (2011).

Etezadi, F. et al. Optimization of a PDMS-Based cell culture substrate for High-Density Human-Induced pluripotent stem cell adhesion and Long-Term differentiation into cardiomyocytes under a Xeno-Free condition. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8, 2040–2052. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00162 (2022).

Nazbar, A. et al. Molecular imprinting as a simple way for the long-term maintenance of the stemness and proliferation potential of adipose-derived stem cells: an in vitro study. J. Mater. Chem. B. 10, 6816–6830. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2TB00279E (2022).

Bonakdar, S. et al. Cell-imprinted substrates modulate differentiation, redifferentiation, and transdifferentiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 13777–13784. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b03302 (2016).

Kashani, S. Y. et al. An integrated microfluidic device for stem cell differentiation based on cell-imprinted substrate designed for cartilage regeneration in a rabbit model. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 121, 111794–111794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2020.111794 (2021).

Haramshahi, S. M. A. et al. Tenocyte-imprinted substrate: A topography-based inducer for tenogenic differentiation in adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed. Mater. 15, 035014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-605X/ab6709 (2020).

Mehrjoo, M., Karkhaneh, A., Nazarpak, M. H., Alishahi, M. & Bonakdar, S. Hydroxyapatite-induced bioactive and cell-imprinted polydimethylsiloxane surface to accelerate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation: an in vitro study on Preparation and differentiating capacity. Biomed. Mater. 20, 045024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-605X/ade5e0 (2025).

Dadashkhan, S., Irani, S., Bonakdar, S. & Ghalandari, B. P75 and S100 gene expression induced by cell-imprinted substrate and beta-carotene to nerve tissue engineering. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138, 50624. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.50624 (2021).

Gupta, S. et al. Dermal regeneration template in the management and reconstruction of burn injuries and complex wounds: A review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. – Global Open. 12, e5674. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000005674 (2024).

Kenny, F. N. et al. Tissue stiffening promotes keratinocyte proliferation through activation of epidermal growth factor signaling. J. Cell. Sci. 131 https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.215780 (2018).

Maparu, A. K., Singh, P., Rai, B., Sharma, A. & Sivakumar, S. PDMS nanoparticles-decorated PDMS substrate promotes adhesion, proliferation and differentiation of skin cells. J. Colloid Sci. 659, 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2023.12.155 (2024).

Mobasseri, S. A. et al. Patterning of human epidermal stem cells on undulating elastomer substrates reflects differences in cell stiffness. Acta Biomater. 87, 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.063 (2019).

Keyhanvar, N. et al. The combined thermoresponsive Cell-Imprinted Substrate, induced Differentiation, and KLC sheet formation. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 12, 356–365. https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2022.034 (2022).

Coger, V. et al. Tissue concentrations of zinc, iron, copper, and magnesium during the phases of full thickness wound healing in a rodent model. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 191, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1600-y (2019).

Velnar, T., Bailey, T. & Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 37, 1528–1542. https://doi.org/10.1177/147323000903700531 (2009).

Bowden, L., Byrne, H., Maini, P. & Moulton, D. A morphoelastic model for dermal wound closure. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 15, 663–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-015-0716-7 (2016).

Takeo, M., Lee, W. & Ito, M. Wound healing and skin regeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 5, a023267. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023267 (2015).

Li, J., Zhang, Y. P. & Kirsner, R. S. Angiogenesis in wound repair: angiogenic growth factors and the extracellular matrix. Microsc Res. Tech. 60, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.10249 (2003).

Mukhtarovna, K. M. et al. Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of silver Nanoparticle-Mediated wound healing in rabbits. J. Nanostruct. 13, 747–754. https://doi.org/10.22052/JNS.2023.03.015 (2023).

Pal, P. et al. Bilayered nanofibrous 3D hierarchy as skin rudiment by emulsion electrospinning for burn wound management. Biomater. Sci. 5, 1786–1799. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7BM00174F (2017).

Sharun, K. et al. Development and characterization of contraction-suppressed full-thickness skin wound model in rabbits. Tissue Cell. 90, 102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tice.2024.102482 (2024).

Choi, S. W., Zhang, Y., MacEwan, M. R. & Xia, Y. Neovascularization in biodegradable inverse opal scaffolds with uniform and precisely controlled pore sizes. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201200106 (2013).

Rho, K. S. et al. Electrospinning of collagen nanofibers: effects on the behavior of normal human keratinocytes and early-stage wound healing. Biomaterials 27, 1452–1461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.004 (2006).

Dumin, J. A. et al. Pro-collagenase-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-1) binds the α2β1 integrin upon release from keratinocytes migrating on type I collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29368–29374. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M104179200 (2001).

Azari, Z. et al. Stem cell-mediated angiogenesis in skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Wound Repair. Regen. 30, 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.13033 (2022).

Rozario, T. & DeSimone, D. W. The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: a dynamic view. Dev. Biol. 341, 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.026 (2010).

Talbott, H. E., Mascharak, S., Griffin, M., Wan, D. C. & Longaker, M. T. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell. Stem cell. 29, 1161–1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2022.07.006 (2022).

Bainbridge, P. Wound healing and the role of fibroblasts. J. Wound Care. 22 https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2013.22.8.407 (2013).

Shams, F. et al. Overexpression of VEGF in dermal fibroblast cells accelerates the angiogenesis and wound healing function: in vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Rep. 12, 18529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23304-8 (2022).

Hamou, C. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells can participate in ischemic neovascularization. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 123 https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318191be4a (2009). 45S-55S.

Badiavas, E. V., Abedi, M., Butmarc, J., Falanga, V. & Quesenberry, P. Participation of bone marrow derived cells in cutaneous wound healing. J. Cell. Physiol. 196, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.10260 (2003).

Sasaki, M. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into multiple skin cell Type1. J. Immunol. 180, 2581–2587. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2581 (2008).

Chen, J. S., Wong, V. W. & Gurtner, G. C. Therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for cutaneous wound healing. Front. Immunol. 3, 192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00192 (2012).

Blanpain, C. & Fuchs, E. Plasticity of epithelial stem cells in tissue regeneration. Science 344, 1242281. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242281 (2014).

Guerra, L., Dellambra, E., Panacchia, L. & Paionni, E. Tissue engineering for damaged surface and lining epithelia: stem cells, current clinical applications, and available engineered tissues. Tissue Eng. Part. B Rev. 15, 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0418 (2009).

Isakson, M., de Blacam, C., Whelan, D., McArdle, A. & Clover, A. J. P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Cutaneous Wound Healing: Current Evidence and Future Potential. Stem Cells Int. 831095, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/831095 (2015).

Javed, F., Akram, Z., Khan, J. & Zafar, M. S. et al. In Dental Implants 133–143 (Woodhead Publishing, 2020). (eds Muhammad Sohail Zafar.

Lee, S. H., Jin, S. Y., Song, J. S., Seo, K. K. & Cho, K. H. Paracrine effects of adipose-derived stem cells on keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. Ann. Dermatol. 24, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2012.24.2.136 (2012).

Moriyama, M. et al. Adipose-derived stromal/stem cells improve epidermal homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 9, 18371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54797-5 (2019).

Sheng, L., Yang, M., Liang, Y. & Li, Q. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ADSC s) transplantation promotes regeneration of expanded skin using a tissue expansion model. Wound Repair. Regen. 21, 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12080 (2013).

Fang, W. C. & Lan, C. C. E. The epidermal keratinocyte as a therapeutic target for management of diabetic wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054290 (2023).

Chavez-Munoz, C. et al. Transdifferentiation of Adipose-Derived stem cells into Keratinocyte-Like cells: engineering a stratified epidermis. PLOS ONE. 8, e80587. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080587 (2013).

Watt, F. M. & Jensen, K. B. Epidermal stem cell diversity and quiescence. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/emmm.200900033 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Mr. Mahmoud Shams for producing a schematic illustration and visualization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.: Investigation. D.S.: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing S.S.: Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. S.P.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. S.Y.-K.: Formal analysis, Writing–original draft. S.B.: Investigation. M.M.D.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Resources. S.M.G.: Writing—original draft. M.M.: Investigation. F.A.: Investigation. S.A.: Investigation, Formal analysis. M.A.S.: Resources. S.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Validation, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alipour, S., Shams, D., Samani, S. et al. Wound healing improvement by a multicomponent wound dressing of keratinocyte-imprinted polydimethylsiloxane substrate in a rabbit model. Sci Rep 15, 42487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26525-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26525-9