Abstract

Air pollution poses a major health risk globally and is a leading cause of premature mortality. This study evaluates respiratory deposition and health impacts of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in Delhi, India, from 2019 to 2023. Using data from continuous air quality monitoring, we analysed daily and seasonal pollutant variations, with emphasis on Diwali and COVID-19 lockdown periods. PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations exceeded national and WHO guidelines on most days, with peak values of 826.7 µg/m³ (PM10) and 750.5 µg/m³ (PM2.5). The higher respiratory deposition doses (RDD) occurred in evening daily commuter periods, with PM2.5 and PM10 RDD values up to 39% and 23% higher than in the morning period, and maximum daily deposition was observed in 2019 (male, walking), which exceeded WHO air quality guideline-based values by nearly 40-fold. Among daily commuters, evening periods showed higher RDD values than mornings, indicating increased exposure during evening travel. Overall, these results highlight sustained high particulate matter exposure in Delhi and identify key periods and populations at increased risk. The findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to reduce particulate matter exposure and protect public health in polluted urban environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution is among the most pressing environmental and health challenges worldwide, ranking as the fourth leading risk factor for premature mortality after high blood pressure, dietary risks, and tobacco use1. As countries strive for economic growth and improved living standards, air pollution has steadily worsened2,3. The health impacts of air pollution are not confined to major economies such as the United States, China, and India, but extend globally, affecting smaller nations due to the transboundary movement of pollutants4,5,6. South Asian countries—including India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—are particularly affected, owing to high population densities and rapid industrialization1.

Approximately 99% of the world’s population now lives in regions where the World Health Organization (WHO) air quality guidelines are regularly exceeded7. In South Asia, this has resulted in an estimated 2 million premature deaths annually, attributed to PM2.5 concentrations above the WHO threshold of 5 µg/m³8. Air pollution causes a spectrum of short- and long-term health effects, including cardiovascular diseases9,10,11, respiratory conditions10,11,12, neurological disorders, and reproductive problems11,13,14,15,16,17,18. Particulate matter (PM), a key component of air pollution, is particularly concerning due to its well-established links to adverse health outcomes19,20, including toxic effects from specific PM species21. Notably, even low pollutant concentrations have been associated with serious health risks16,22. This mounting evidence underscores the urgent need for effective policies and control strategies to limit pollutant production and population exposure.

India is among the countries most severely affected by air pollution; nine of the world’s ten most polluted cities, according to the IQAir World Air Quality Report 2023, are located in India23. Delhi, the national capital, is the world’s most polluted capital city. Following its recent surpassing of China as the world’s most populous country24, India’s megacities—particularly Delhi, now the second largest city globally25—subject millions of residents to hazardous air quality.

In Delhi, particulate matter pollution is particularly concerning, with PM concentrations regularly exceeding both the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and the WHO guidelines26. The human respiratory tract is divided into three primary regions: the head airway, the tracheobronchial region (which conducts air to the lungs), and the alveolar region, responsible for gas exchange (Fig. 1)27. Particulate matter with an aerodynamic equivalent diameter less than or equal to 10 μm (PM10) can penetrate deep into the lungs, reaching the alveoli via the larynx, trachea, and terminal bronchioles28. Location of particle deposition is a clinically important factor, as upper airway deposition is associated with irritation of the respiratory tract and bronchitis, whereas tracheobronchial deposition leads to airway obstruction and asthma exacerbation and lastly, deposition in the alveolar region is linked with systemic uptake leading to inflammation, and cardiovascular morbidity29. PM is deposited throughout the respiratory system via mechanisms such as sedimentation, inertial impaction, diffusion, electrostatic effects, and interception. Coarse particles (> 10 μm) tend to deposit in the oropharyngeal region and larynx, while fine particles (2–10 μm) settle in the tracheobronchial region. Finer particles (0.5–2 μm) primarily deposit in the alveoli, whereas ultrafine particles (< 0.5 μm) may be partially exhaled due to their small size, but they also exhibit high deposition efficiency in the alveolar region via diffusion30.

The location of deposition is clinically significant: upper airway deposition is associated with irritation and bronchitis, tracheobronchial deposition contributes to airway obstruction and asthma exacerbations, while alveolar deposition is linked to systemic uptake,

Finer particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5 and PM1) penetrates deeply into the lungs, with deposition patterns that influence their pathogenic potential28. For example, respirable dust (fine particles) is linked to diseases such as pneumoconiosis and silicosis, while larger particulates can cause bronchitis and obstructive pulmonary dysfunction, especially among coal miners31. Deposition efficiency is influenced by multiple factors, including gender, age, particle size, airway morphology, and breathing parameters such as tidal volume, inhalation/exhalation duration, and breathing frequency27,32.

Deposition of particulate matter contributes to the onset and progression of various respiratory diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depending on both the size, location, and toxicity of the deposited particles31,33,34,35. Particles that reach different regions of the respiratory tract can obstruct airways and, if small enough, may permeate the bloodstream via the alveolar-capillary barrier, potentially affecting other organs36,37. Particles larger than 10 μm are typically retained in the upper respiratory tract and are cleared by coughing or swallowed into the gastrointestinal tract. PM2.5–10 is generally cleared by the mucociliary escalator within hours, whereas particles deposited in the alveolar region are removed much more slowly—over weeks to years—primarily by alveolar macrophages38. Ultimately, particulate matter may be eliminated from the body via multiple pathways, including sweat, urine, and feces39.

According to the European Environment Agency, fine particulate matter (PM2.5) was responsible for approximately 253,000 premature deaths in the European Union in 202140. In Delhi, high PM2.5 concentrations led to an estimated 56,876 premature deaths from 2015 to 2019, corresponding to an economic loss of roughly USD 157 billion26. The primary sources of particulate pollution in Delhi include fossil fuel combustion, industrial emissions, stubble burning, and cross-boundary transport from neighbouring states (Haryana and Punjab) and even countries such as Pakistan26,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. These particulates ultimately deposit in the respiratory tracts of both humans and animals, driving adverse health outcomes.

The present study aims to characterize the deposition of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in the respiratory tract of males and females in Delhi over a five-year period (2019–2023). We analyzed seasonal and diurnal variations in deposition, with special attention to differences between morning and evening commute periods—timeframes during which much of Delhi’s workforce and student population are exposed to heightened pollution levels due to traffic-related emissions. Additionally, we examined the impact of special events, such as Diwali and the COVID-19 lockdowns and unlock periods, on deposition patterns.

Materials and methods

Study area and datasets

This study was conducted in Delhi, the capital city of India, located in the northern part of the country and entirely landlocked. Delhi covers an area of 1,483 km², of which 369.35 km² is classified as rural and 1,113.65 km² as urban, making it the largest city in India by area48. The region experiences four distinct seasons: Summer (March–May), Monsoon (June–September), Post-monsoon (October–November), and Winter (December–February). Ambient temperatures range from 4 °C in winter to 45 °C during summer, and the city receives an average annual rainfall of 600–800 mm49.

Data on PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were obtained from the Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations (CAAQMS) network, managed by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), Delhi. Measurements were collected from all thirty-nine monitoring stations across the city, spanning 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2023. The dataset includes particulate matter concentrations (in µg/m³) recorded at both 15-minute and daily intervals over the five-year period. Outliers with values exceeding 999 µg/m³ were excluded from the analysis26,50,51. CPCB uses β-ray attenuation analysers for monitoring PM10 and PM2.5 in the CAAQMS network with a range of 0–1000 µg/m³, so values generated above this range have been considered unreliable leading to their exclusion considering instrument overload or calibration anomalies52. We found that no values were reported above 1000 µg/m³, indicating that readings fixed at the upper ceiling of 1000 µg/m³ are likely to represent censored values (i.e. the true concentration may be higher but cannot be quantified beyond the instrument’s operational range). Such points were therefore conservatively excluded to minimize the influence of potential instrument overload or calibration anomalies.

The CAAQMS network also provides meteorological and air quality data, with station management shared among the CPCB, Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC), and the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD). The monitoring stations were categorized into four types—residential, commercial, industrial, and institutional—based on predominant land use and activities in their surrounding areas. Data from each category were analyzed both individually and in aggregate (see Supplementary Table S-1).

Special events data

The analysis also targeted special events occurring during the study period (2019–2023), particularly the annual Diwali festival and the COVID-19 lockdowns and unlock phases. To examine the impact of COVID-19 control measures, data were segmented into six periods: pre-lockdown (1–24 March 2020), Lockdown-1 (25 March–14 April 2020), Lockdown-2 (15 April–3 May 2020), Lockdown-3 (4–17 May 2020), Lockdown-4 (18–31 May 2020), and Unlock-1 (1–30 June 2020).

Diwali, the festival of lights, occurs annually in October or November and is marked by widespread use of firecrackers, resulting in significant increases in ambient particulate concentrations. For Diwali, data were analysed for three periods: five days prior to Diwali (pre-Diwali), the day of Diwali, and five days following Diwali (post-Diwali), to assess changes in pollution and deposition patterns associated with the festival.

Respiratory deposition dose analysis

Respiratory deposition dose (RDD) was estimated for adult males and females in Delhi over the five-year period at both 15-minute and daily intervals, under two activity scenarios: sitting and walking (light exercise). Calculations were based on the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) model32, as employed in previous studies53,54,55. ICRP framework remains the internationally accepted standard for deposition modelling and cross-study comparison. Its continued use is supported by international regulatory bodies and peer-reviewed studies worldwide because it offers a standardized framework that facilitates cross-study and cross-regional comparison53,56,57.

where VT is tidal volume (m³ per breath), f is breathing frequency (breaths per minute), PM₁ is the mass concentration for the i-th size of particulate matter, and DFⱼ is the deposition fraction for a specific region of the respiratory tract which is given by Eqs. 2, 4 and 558; DF for head airway (HA) is

Where dp is the particle size in µm and IF is the inhalation fraction which is computed as given by the ICRP model32

Deposition fraction for the tracheobronchial region (TB) is given by Eq. (4)

The deposition fraction for the alveolar region (AL) is given by

Total deposition fraction DFT is given by

The values of VT and f depend on gender and physical activity. For males, VT was set at 12.5 × 10⁻⁴ m³ per breath for walking and 7.5 × 10⁻⁴ m³ for sitting; for females, values were 9.9 × 10⁻⁴ m³ (walking) and 4.6 × 10⁻⁴ m³ (sitting). Breathing frequencies were 20 (walking) and 12 (sitting) breaths/minute for males, and 21 (walking) and 14 (sitting) breaths/minute for females53,59.

Deposition fractions (DF) for the head airway (HA), tracheobronchial (TB), and alveolar (AL) regions were calculated using the ICRP model (Eqs. 2–6, see Supplementary Information for details). Both morning and evening commuting periods were examined, with a focus on working adults and students who typically travel during these times and may be exposed to elevated ambient PM concentrations.

The CPCB dataset only provides bulk mass concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10, without size distribution. To apply the ICRP deposition model, we assumed representative aerodynamic diameters of dp = 2.5 μm for PM2.5 and dp = 10 μm for PM10, following conventions in prior deposition studies. This approach is also consistent with recent Delhi-based RDD studies56. While this assumption is a simplification, it allows comparability and enables analysis of relative spatio-temporal patterns.

The ICRP deposition model parameters utilized in present study were originally developed for Caucasian populations. In absence of validated database for Indian population, we have utilized these parameters as done by previous studies in India53,56. While we acknowledge that these assumptions might introduce some uncertainty due to population-level differences in lung volume and breathing patterns, the overall bias is expected to be modest relative to the magnitude of exposure differences observed. Data analysis and all calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel and Python 3.10 (Spyder IDE), with pandas (v1.5.3) for data processing and matplotlib (v3.7.1) for visualization.

Results and discussion

Particulate matter trends

PM10 trend

Daily all-station average PM10 concentration has been plotted for the five years (2019–2023) and shown in Fig. 2. The highest daily average (across all stations) was 720.23 µg/m³, observed on 9 November 2020. The single-station maximum, 826.70 µg/m³, was recorded at the NSIT station (Dwarka) on the same date, while the lowest recorded PM10 concentration was 1 µg/m³ at DTU, Delhi, on 20 September 2022. Details of maximum and minimum daily concentrations, along with corresponding station names and dates for each year, are provided in Supplementary Table S-2. Both the NAAQS and WHO prescribed limits for PM10 were exceeded throughout the five-year study period at all monitoring stations.

The NAAQS daily limit for PM10 (100 µg/m³) was exceeded on average 77.5% of days during the five-year period, while the WHO daily guideline (45 µg/m³) was breached on 96.5% of days. Notably, although 2020 had the highest recorded daily and average PM10 concentrations, it also had the fewest days exceeding the NAAQS and WHO limits (68.9% and 94.4%, respectively), possibly due to reduced emissions during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The highest annual average PM10 concentration was 216.87 µg/m³ in 2019, while the lowest was 180.18 µg/m³ in 2020 (Fig. 3). Spatial mapping using inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation in QGIS (Supplementary Figure S-1) revealed persistently higher PM10 concentrations in the western and northwestern districts of Delhi. In contrast, central Delhi—characterized by greater green cover and tree density—exhibited the lowest annual averages.

PM2.5 trend

The citywide maximum daily average PM2.5 concentration was 544.71 µg/m³, recorded on 3 November 2019 (Fig. 4). PM2.5 concentrations exhibited distinct seasonal variation, with pronounced peaks during the post-monsoon and winter seasons, and lowest values during the monsoon. Typically, PM2.5 levels began to rise in September and remained elevated through winter, coinciding with increasingly stagnant atmospheric conditions in Delhi.

The highest single-station PM2.5 concentration (750.47 µg/m³) was measured at the Lodhi Road monitoring site on 11 November 2021. The lowest PM2.5 readings (1 µg/m³) were recorded on several dates in 2023 at the Siri Fort and Nehru Nagar stations. Annual average PM2.5 concentrations ranged from a high of 108.24 µg/m³ in 2019 to a low of 94.14 µg/m³ in 2020 (Fig. 3). Detailed daily maximum and minimum concentrations, with station names and dates, are available in Supplementary Table S-3.

The NAAQS daily standard for PM2.5 (60 µg/m³) and the WHO guideline (15 µg/m³) were exceeded almost continuously throughout the five-year study period. Across all stations, only 1.6% of daily PM2.5 measurements were below the WHO guideline, while the NAAQS limit was exceeded in approximately 60% of measurements. Both standards were breached least often in 2020 (WHO: 97.7% of days breached; NAAQS: 53.2%). Annual averages for both PM10 and PM2.5 consistently exceeded the respective NAAQS and WHO guidelines each year (see Fig. 3, horizontal reference lines).

Both PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were lowest during the monsoon and highest in early November, coinciding with the onset of winter and widespread stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana. Stubble burning, together with emissions from vehicles, industry, power plants, construction, and road dust, significantly contributes to the seasonal pollution peaks. Stable atmospheric conditions at the start of winter promote pollutant accumulation and further degrade air quality41,60,61,62,63,64. The spatial distribution of PM2.5 (Supplementary Figure S-2) mirrors that of PM10, with highest values in western and north-western districts and lowest in central Delhi.

The seasonal peaks observed, highlight the combined effects of emission and meteorology in Delhi. Entrapment of various emissions such as stubble burning, vehicular and industrial emissions due to shallow boundary layer and low wind speeds leads to these seasonal peaks. This subjects Delhi’s population to chronic exposure, in turn causing significant adverse health effects including exaggeration of existing medical conditions such as accelerated atherosclerosis, COPD progression, and increased hospital admissions for respiratory illness leading to premature mortality. Importantly, the persistence of annual averages above even the more lenient NAAQS suggests that incremental policy measures have been insufficient, underscoring the need for structural interventions in both regional agriculture management and urban emissions control.

Respiratory deposition dose (RDD) analysis

Respiratory Deposition Dose was calculated for different regions of the lungs using the Eq. (1) to (6) for commercial, industrial, institutional, and residential areas separately for males and females in walking and sitting positions.

PM2.5

RDD values for PM2.5 were highest in industrial areas, followed by commercial, institutional, and then residential regions. In the sitting position, male RDDs were 1.4 times higher than those for females; during walking, males’ RDDs were 1.2 times higher than females. Across all respiratory regions, RDDs were greater during walking than sitting. The maximum daily total RDD for PM2.5 (RDDT-2.5) was 13.13 µg/min (male, walking), followed by 10.92 µg/min (female, walking), 4.73 µg/min (male, sitting), and a minimum of 3.38 µg/min (female, sitting); all found for industrial regions in 2019.

Deposition of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) also followed a trend where the maximum deposition was observed in the Head airway region followed by Alveolar regions and then the least deposition was found for the tracheobronchial region. Maximum Annual average RDDT−2.5 was observed in 2019 for both genders in sitting and walking positions. Yearly average values and maximum values for concentration have been reported in Supplementary Tables 2,3 and 4. For reference, Maximum daily RDDT−2.5 at NAAQS and WHO prescribed PM2.5 levels would be 1.31 µg/min and 0.33 µg/min respectively for Walking position in men. Maximum RDDT−2.5 (Male-Walking Position) reported in 2019, was 10.02 and 39.79 times higher than RDD values at NAAQS and WHO levels, respectively.

We have also analyzed seasonal variation for respiratory deposition dose for all five years for all four regions for both genders in walking and sitting positions (Supplementary Fig.-S3- to Fig.-S18). Generally, total respiratory deposition values (RDDT−2.5) have seen a decline during the monsoon months, summer values were also high compared to monsoon values, although visible high peaks were seen during the post-monsoon and winter months. Respiratory depositions were highest in the industrial region generally throughout the five years (2019–2023). Interestingly, during monsoon season, for brief periods, respiratory deposition values were found to be higher in commercial areas (Supplementary Fig. S-3 to S-34). One possible explanation for this trend is increased human activity and traffic in commercial areas during the monsoon months, when weather conditions become more favourable compared to the preceding summer.

PM10

Overall, respiratory deposition doses for PM10 were highest in industrial areas, as shown in Supplementary Figures S19–S34. All regions exhibited clear peaks in deposition during the post-monsoon and winter seasons, with sharp declines during the monsoon (particularly August and September). Notably, commercial areas showed consistently higher deposition values than other regions, both during and outside periods of general decline. This may be attributable to increased human activity and traffic in commercial zones, especially during the monsoon when weather conditions become more favorable for outdoor movement. Intensified economic activity likely drives higher PM10 concentrations and, consequently, increased respiratory deposition in these areas.

The pattern of PM10-related RDDs across the respiratory tract closely mirrored that observed for PM2.5. The highest deposition occurred in males during walking, followed by females walking, males sitting, and females sitting. The maximum daily total respiratory dose for PM10 (RDDT−10) was 15.73 µg/min (male, walking), with corresponding values of 13.64 µg/min (female, walking), 5.66 µg/min (male, sitting), and 4.22 µg/min (female, sitting); all of these maxima were found in industrial regions.

For PM10, sitting RDDT−10 values in males were 1.34 times those in females; during walking, males’ RDDT−10 values were 1.15 times higher than females. The RDDT−10 for walking was substantially higher than for sitting—2.78 times higher in males and 3.23 times higher in females.

Regionally, the highest PM10 deposition occurred in the head airway, followed by the alveolar region, with the lowest deposition in the tracheobronchial region. This distribution was consistent with that observed for PM2.5, although the percentage contribution of each region differed between particle sizes (see Fig. 5). The annual average deposition in the tracheobronchial region for PM10 was only 1.7%, substantially lower than the 7.1% observed for PM2.5. Conversely, the alveolar region accounted for 12.6% of total PM2.5 deposition, compared to 8.6% for PM10.

These results are consistent with prior studies showing that smaller particles penetrate deeper into the respiratory system, increasing their potential for adverse health effects53,59,65,66,67. Notably, RDD values for both PM2.5 and PM10 in the present study were higher than those reported in previous Indian studies53,68,69. This difference is majorly because of cities where these studies were conducted has lesser PM concentration as well as study design, meteorological conditions and locality. High RDD values (> 1) was reported in current study can lead to respiratory problems as suggested by previous studies53,69 which leads to premature mortality as calculated by26,51.

The higher alveolar deposition of PM2.5 compared to PM10 suggests an elevated risk of respiratory conditions such as asthma, wheezing, and pneumonia, owing to the deeper penetration of fine particles into lung tissue70. This aligns with earlier reports indicating greater toxicity of PM2.5 versus PM1071,72. Similar seasonal deposition patterns—greater values during winter and post-monsoon—have been observed in other Indian cities such as Dehradun73.

Higher deposition of PM2.5 in alveolar regions of lungs have direct implications for human health. The alveolar region is the primary site of gas exchange, and deposition here is strongly associated with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular morbidity. Cellular toxicity study conducted by Tseng et al. (2024) on lung epithelial cells shows that PM exposure induces decreased cell growth rate, increased cell mortality and also leads to reduced wound healing74. Our findings highlight that male walking RDDT-2.5 values were ~ 10–40 times higher than values calculated at NAAQS and WHO levels which would have severe impact on lung system and demonstrates how far currents exposures exceeds beyond the PM2.5 thresholds values. Although coarser PM are mostly deposited in head airways regions, their consistently high RDD values also demonstrate their substantial health relevance. Current findings also highlight elevated levels of PM10 related RDD in commercial and industrial areas underscoring disproportionate exposure borne by workers and daily wage earners in these sectors. From a policy perspective, this highlights the importance of enforcing dust-control measures at construction sites, improving road sweeping practices, and mandating dust suppression in industrial yards.

This estimation is not only academic in nature but also highlights the severe exposure and deposition of inhalable PM by ordinary commuters in Delhi relative to what global agencies consider acceptable. The findings of current study provide a knowledge bridge between ambient concentrations and actual exposure concentration in lung system leading to increased burden of various diseases such as COPD, ischemic heart disease, and lower respiratory infections. From a regulatory standpoint, such results strengthen the rationale for adopting WHO interim targets in India, since even meeting NAAQS would still leave the alveolar region exposed to doses an order of magnitude above safe benchmarks.

Special events analysis

Diwali

Diwali, celebrated annually in late October or early November, is marked by widespread use of firecrackers throughout India, resulting in significant increases in atmospheric particulate matter. This period coincides with the post-monsoon season, when ambient PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations typically reach their annual peak.

Figures 6, 7, 8, 9 illustrate pollution and respiratory deposition trends for both PM10 and PM2.5 before, during, and after Diwali. The highest daily concentrations during the Diwali period were 581.48 µg/m³ for PM10 (1 November 2019) and 692.27 µg/m³ for PM2.5 (9 November 2020). Concentrations of both pollutants rose sharply toward the end of Diwali, particularly at night, when firecracker use peaks. The combination of intense emissions and low nocturnal boundary layer heights results in rapid accumulation and surface trapping of particulates.

RDDs for PM2.5 and PM10 were calculated for all three respiratory regions (alveolar, head airway, and tracheobronchial) across pre-, during-, and post-Diwali periods for each year (Figs. 8 and 9). The highest deposition occurred in the head airway, followed by the alveolar and tracheobronchial regions, with maximum values again recorded in 2020. RDDs were notably higher during and after Diwali than in pre-Diwali days, underscoring the health risks associated with festival-related firecracker emissions. These elevated deposition values persisted throughout the five-day post-Diwali window, likely due to stable atmospheric conditions and ongoing surface pollutant entrapment.

Respiratory deposition dose for PM10 was found to be more than PM2.5 for all three regions in the respiratory system during, pre and post-Diwali. RDD values for walking were found to be higher than sitting and similarly, Male RDD values were higher than Female RDD values. The highest RDD values of 9.65 ± 3.16 µg/min and 11.28 µg/min were calculated for males in walking position in the Head Airway region respectively for the pre-Diwali and during the Diwali period in 2020 (Supplementary Table S-5). In the case of post-Diwali, Maximum deposition was also found to be for males in walking position in the Head Airway region but this highest value of 9.79 ± 1.39 µg/min was calculated for 2019. In 2020, Post Diwali RDD values were lesser than pre-Diwali and Diwali values, the reason behind this could be higher wind velocity (around double) during the post-Diwali period which could have led to fast dispersion of pollutants causing lesser deposition of particulate matter.

We further compared RDDs between daytime (06:00–17:45) and night-time (18:00–05:45) periods. For PM10, night-time RDDs consistently exceeded daytime values across all respiratory regions. For PM2.5, night-time RDDs were higher than daytime only in the tracheobronchial region; in the alveolar region, daytime RDDs were higher 67.7% of the time, and in the head airway region, daytime RDDs were consistently higher. On Diwali itself, night-time RDDs for all regions were 1.94 times higher than daytime for PM10; for PM2.5, night-time RDDs were 1.11 and 3.20 times higher than daytime in the alveolar and tracheobronchial regions, respectively, while in the head airway region, daytime RDDs were 1.47 times higher than night-time.

Previous studies have also measured PM concentration as well as number of particles during Diwali period and they have also reported higher concentration post Diwali similar to current study75,76. Similar observation regarding high deposition during night and daytime was observed on post Diwali in previous study75. High deposition of particulate matter during the Diwali period, can cause sudden increased problems to sensitive population such as senior citizens, kids and respiratory patients which has been widely reported by many studies77,78.

The RDD spikes observed during Diwali shows acute short-term exposure during intense emission events. The deposition of finer particulate (PM2.5) in deeper regions have been established to cause severe health implication and are generally established as pollutant requiring greater concern. Our findings show that nearly double deposition of PM10 occurs on Diwali nights compared to preceding days, not only confirming increased inhalation burden during firecrackers combustion but also highlighting a situation where coarse particles, when present at extreme concentrations, can exacerbate respiratory morbidity. Higher deposition of PM10, even in headway can induce irritation in upper airways, which can aggravate conditions such bronchitis and can also lead to asthma attacks, in turn, compounding over the increased burden on PM2.5 in alveolar region. This shows that, while annual averages exposures could lead to chronic health issues, sudden exposures during such high emission events could results in a greater number of Emergency room visits, asthma attacks, and mortality among vulnerable populations, which is also supported by evidence from hospital records79,80. These findings taken together highlights that festival related surges are not only one-night phenomenon, but can persist for several days due to stable nocturnal boundary layers, leading to multi-day exposure hazard. This highlights impact of these surges on the entire respiratory tract, amplifying risks for sensitive groups such as children, the elderly, and patients with COPD or asthma. From a policy perspective, the evidence underscores the need for stricter firecracker regulation, enforcement of bans during high-pollution periods, and targeted public health messaging to minimize exposure during Diwali nights.

COVID-19 period

COVID-19, caused by the coronavirus, resulted in a global health crisis with an estimated 14 million excess deaths—2.74 times higher than officially reported—largely due to underreporting and data gaps in many countries81,82. The virus spreads easily via respiratory droplets, prompting governments worldwide, including India, to implement lockdowns to control its rapid transmission83,84,85.

India implemented a multi-phase lockdown from 25 March to 31 May 2020, with gradual relaxation in subsequent unlock phases (see Supplementary Table S-6). RDDs were calculated for various respiratory regions across all lockdown and unlock phases. The lowest total RDDs were observed during lockdown phase-1, when nearly all non-essential activities were suspended; the highest RDDs occurred before the lockdown (Figs. 10 and 11). Specifically, pre-lockdown total RDD2.5 values were 2.8, 2.4, 2.1, and 2.0 times higher than during lockdown phases 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and 2.4 times higher than in Unlock-1.

For PM10, average total RDD10 values before lockdown were 2.4, 1.8, 1.6, 1.3, and 1.7 times higher than those observed during lockdown phases 1, 2, 3, 4, and Unlock-1, respectively. Pre-lockdown, the average RDD10 was also 1.7 times greater than the corresponding value for RDD2.5. Among females, average RDD10 values were 2.0 to 2.6 times higher than RDD2.5 across all phases, while for males, the difference ranged from 1.9 to 2.5 times. These results indicate that, especially after the lockdown, PM10 posed a proportionally greater respiratory deposition risk for females compared to PM2.5. As restrictions were gradually lifted during the successive phases, RDD values for both males and females increased. Interestingly, deposition during the Unlock-1 phase was lower than during lockdown phases 3 and 4, likely due to the onset of the monsoon season, which naturally reduces atmospheric particulate matter through rainfall.

For both PM2.5 and PM10, the highest respiratory deposition occurred in the head airway region, with the lowest deposition in the tracheobronchial region. During Lockdown Phase-1, the greatest reduction in PM10 deposition was seen in institutional areas (a 60.73% decrease), followed by commercial (59.27%) and residential (58.80%) areas, with the smallest reduction observed in industrial areas (57.95%), as shown in Supplementary Table S-7.

For PM2.5, the largest decrease in respiratory deposition dose was observed in residential areas (67.96%), followed by industrial (65.88%) and commercial (62.39%) areas, while institutional areas experienced the smallest reduction (61.44%).

These trends reflect the differing impacts of lockdown measures across various urban environments. Most institutional and commercial establishments were fully closed, leading to significant reductions in particulate emissions in these areas. Residential zones also saw substantial declines, likely due to decreased population density as many daily wage workers left the city during the large-scale migration from major Indian cities such as Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai, and Ahmedabad86. In contrast, industrial areas experienced the smallest decrease in deposition, possibly because essential manufacturing activities continued throughout the strictest lockdown periods.

The reduction in RDD observed across all lockdown and unlock phases, compared to pre-lockdown levels, underscores the substantial impact that restrictions on human activity can have on air quality and public health. This sharp decline in RDD during lockdown serves as, however unintentional or unwarranted, a natural experimental setup demonstrating the positive health outcomes through structural emission reduction. This suggests two critical implications. First, sustained decrease in traffic and industrial emissions- even if partial- has ability to yield significant reduction in deposition doses leading to positive health outcomes. Second, positive benefit of multi-sectoral (transport, industry, residential energy use) restrictions in reducing deposition during lockdown shows need for similar multi-sector synergetic intervention plan to drive significant and noticeable impact. These findings highlight the importance of implementing targeted air quality interventions—not just during emergencies like the pandemic, but as part of routine policy—to maintain the health benefits achieved during lockdowns87. The marked decreases in respiratory deposition, especially in industrial and residential areas, provide valuable guidance for policymakers seeking to mitigate pollution-related health risks.

Morning and evening periods

Delhi, as one of the largest and most densely populated cities in India25, has a significant working-age and student population that commutes daily to workplaces, schools, and colleges. This daily movement exposes a large segment of residents to ambient air pollution, particularly during morning and evening hours, which poses notable health risks. In this study, the respiratory deposition dose was calculated for all three regions of the respiratory tract at 15-minute intervals. The data were then categorized into two time periods—morning (07:30 to 10:00 AM) and evening (16:15 to 18:45)—for each day across the five-year span (2019–2023).

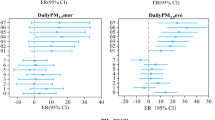

The daily total respiratory deposition dose (RDD) for PM10 and PM2.5 was calculated by averaging the data over the defined morning and evening periods (see Figs. 12 and 13). The highest deposition values were consistently observed for males in the walking position during both morning and evening intervals. Region-specific analysis showed that the maximum deposition occurred in the head airway region, followed by the alveolar region, with the lowest deposition in the tracheobronchial region for both PM10 and PM2.5 (see Supplementary Table S-8).

For PM2.5 during the morning period, the highest RDD recorded was 13.40 µg/min (head airway, walking, male) on 3rd November 2019, while the lowest was 0.0031 µg/min (tracheobronchial, sitting, female) on 20th May 2021. In the evening, the maximum RDD was 8.05 µg/min (head airway, walking, male) on 2nd November 2019—just prior to the highest morning value, indicating that pollution levels began rising the previous night. The lowest evening RDD for PM2.5 was 0.0027 µg/min (tracheobronchial, sitting, female) on 10th September 2023.

For PM10 during the morning period, the maximum RDD observed was 18.86 µg/min (head airway, walking, male) on 23rd May 2021, which coincided with very low wind speeds (0.5–2 m/s). These stagnant conditions, together with local dust resuspension from dry soil and construction activity, likely contributed to elevated coarse particle concentrations during this period. Minimum RDD was 0.0013 µg/min (tracheobronchial, sitting, female) on 13th August 2020. In the evening, the highest RDD was 14.22 µg/min (head airway, walking, male) on 9th November 2020, and the lowest was again 0.0013 µg/min (tracheobronchial, sitting, female) on 9th October 2022. The annual average total respiratory deposition doses for PM10 and PM2.5 during the morning and evening periods are summarized in Table 1..

The highest annual average total respiratory deposition was observed in 2019 for males in the walking position during the morning period, reaching 5.06 ± 3.14 µg/min for PM10 and 2.76 ± 2.27 µg/min for PM2.5. In contrast, the lowest annual averages were recorded in 2020 for females in the sitting position during the evening period, with values of 0.83 ± 0.54 µg/min (PM10) and 0.35 ± 0.31 µg/min (PM2.5).

Throughout the five-year period (2019–2023), evening RDD2.5 values exceeded morning RDD2.5 values on the majority of days. Specifically, evening RDD2.5 was higher on 81.64%, 81.92%, 55.07%, 76.99%, and 76.16% of days in 2019 through 2023, respectively. A similar pattern was observed for RDD10, with evening values surpassing morning values on most days in 2019 (74.52%), 2020 (71.23%), 2022 (70.41%), and 2023 (69.32%), while in 2021, morning RDD10 values were higher on more days (61.37%). The generally higher evening concentrations for both RDD2.5 and RDD10 (except in 2021) underscore the increased particulate matter deposition during evening hours, largely due to a lowered atmospheric boundary layer. This results in greater exposure for daily office workers and commuters during the evening period.

Consistent with our findings, previous studies examining deposition during Diwali have also reported higher night-time deposition compared to daytime levels75. On average, evening RDD values for PM2.5 and PM10 were 39% and 23% higher, respectively, than their corresponding daytime values. This pattern of elevated night-time concentrations was observed across all five years, highlighting the effects of increased nocturnal emissions and reduced atmospheric dispersion. Earlier research in Delhi has attributed spikes in particle numbers during winter haze events to night-time biomass burning for residential heating and cooking88. Additionally, emissions from vehicular pollution are significantly higher at night, accounting for up to 60% of total particulate emissions according to some studies89. Evening rush hour traffic and resulting congestion further contribute to this increase, collectively explaining the higher RDD observed during evening periods.

The elevated RDD values observed during the evening reflect increased exposure during return commute of millions of workers and students, which has significant implications for respiratory health—especially in urban environments like Delhi, where pollution remains persistently high. This shows that working-age adults face elevated cumulative inhaled dose, potentially leading to accelerated onset of chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Meteorological factors such as low evening boundary layer might be trapping vehicular and biomass emissions near the surface. However, from epidemiological point of view, overlap of meteorological conditions with high emissions and human activity, leads to more severe adverse health outcomes. These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions to flatlining this evening peak by promoting staggered work hours, reducing evening traffic congestion, and accelerated transition towards electric buses, cars and auto-rickshaws could reduce this disproportionately burden on human health. More broadly, our analysis demonstrates that framing air pollution in terms of ‘dose received’ rather than ‘concentration present’ can better capture the lived exposure realities of urban populations and inform targeted interventions to protect vulnerable populations during high-risk periods, such as the evening commute when particulate matter deposition reaches its peak.

Novelty and policy implications

Findings of current study not only confirm the established exposure trend of higher winter/post-monsoon pollution, festival spikes, and lockdown-related reductions but also provide several insights beyond existing literature. First of all, this study quantifies RDD at 15-minute resolution across five consecutive years, which gives new insights regarding deposition pattern during the commuter-time. This is a novelty of present work compared to previous India-centric studies which have focused on mostly daily or seasonal averages and international studies focusing on short term campaign period53,68,69. We capture fine temporal variability, which highlights the high inhaled doses during the evening commute hours, which is directly related to urban mobility policy.

Secondly, our findings of RDD are stratified according to land use pattern (residential, industrial etc.), this highlights that deposition pattern is not similar across the various areas, higher deposition was seen in industrial and commercial zones. While prior studies have documented overall declines in pollution concentration during the COVID-19 lockdown, we show this is not true across various zones. We show which sectors maintained higher inhaled doses, which can help policy makers in pinpointing structural sources that require sustained mitigation.

Third, our special event analysis for Diwali, lockdown, and diurnal commuter travel window focuses on exposure pattern beyond concentration-based studies. For example, our Diwali analysis moves beyond established knowledge of past studies specifying higher concentration during the festival night and shows nearly double deposition in the head airway and alveolar regions, demonstrating acute deposition surges across the entire respiratory tract. Such dose-based approach gives stronger link to adverse health outcomes and, particularly acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD. In addition, earlier studies generally applied single breathing rates and did not segregate by gender or activity, while we incorporated gender- and activity-specific ventilation parameters.

Finally, comparing the RDD at various observed concentrations with expected deposition at NAAQS and WHO guideline levels, shows that extent of current exposure is around10–40 times above these thresholds. This comparative framing, rarely reported in Indian studies, underscores the urgency of aligning India’s air-quality standards with global guidelines to achieve meaningful health protection.

All taken together, the contribution of current work moves beyond the descriptive concentration-based approach to dose centric approach giving health outcome relevant insights. Policy implications related to current work include: (i) prioritizing evening traffic interventions to mitigate commuter exposure, (ii) enforcing dust and emission controls in industrial/commercial hotspots, (iii) strengthening firecracker regulations and festival-season advisories, and (iv) embedding structural emission reductions similar to those seen during the COVID-19 lockdown into a long term systematic urban planning. These suggested measures should directly address both acute exposure peaks and chronic background burdens, offering a pathway to reduce health risks in megacities like Delhi.

Conclusion

The current study reveals the severe and persistent nature of air pollution in Delhi, India. We show that residents of Delhi are continuously exposed to high RDD of particulate matter, with commuter-time exposures, land-use patterns, and seasonal episodes compounding this burden. The current study found that:

-

Particulate matter concentrations remained high throughout the study period, continuously exceeding NAAQS and WHO standards with extent of RDD being 40-fold above the WHO standards.

-

Industrial and commercial areas consistently showed the highest RDD values, whereas central Delhi—characterized by government offices, residential areas, and tree cover—recorded comparatively lower concentrations.

-

The COVID-19 lockdown served as a natural experiment, demonstrating that structural emission controls can substantially reduce respiratory dose. In contrast, special events and daily cycles amplified exposures: Diwali nights produced sharp surges under stagnant conditions, while evening commuter periods yielded up to 39% higher PM2.5 doses and 23% higher PM10 doses than mornings.

Together, the findings not only highlight the severe exposure conditions in Delhi but also emphasize the urgent need for targeted interventions—such as stricter emission controls, evening traffic management, and improved mitigation of stubble burning—while accounting for land-use patterns and the role of urban greenery. Such measures could meaningfully reduce both chronic and acute exposures, delivering substantial health and economic benefits for the population of Delhi.

Limitations and future work

The current study offers detailed RDD trends and patterns over a five-year period (2019–2023), including insights from events like COVID-19 and Diwali. However, future research could expand on this by calculating deposition for additional PM fractions and analysing carcinogenic risks based on PM composition—an area limited by reliance on the CPCB database. A limitation of this work is the assumption of single representative diameters (2.5 μm and 10 μm) for PM2.5 and PM10. True ambient PM spans a size distribution, and deposition fractions are sensitive to d Consequently, the absolute magnitude of RDD should be interpreted with caution, although comparative patterns remain robust. Similar assumptions have been used in other RDD studies in Delhi56. Future work with size-segregated monitoring could refine these estimates.

RDD estimates in this study were based on adult population parameters; future work should extend this approach to vulnerable subgroups such as children and the elderly, who may face disproportionate risks due to higher ventilation rates or pre-existing health conditions. Moreover, the physiological parameters used were developed for Caucasian populations, underscoring the need for studies specific to the Indian population. Given that RDD values are influenced by particle size and airway structure, leading to higher RDD in males, further research is needed to analyse the airway structure of both Indian males and females to better understand PM deposition.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) of India (https://app.cpcbccr.com/). Processed data and additional analysis scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Institute, H. E. State of Global Air 2020. A special report on global exposure to air pollution and its health impacts. https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources (2020).

Waters, C. Why the U.S. May extend its run as the world’s leading economy. CNBC Bottom Line Jan 10, (2024).

OECD, OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050. in. OECD Environmental Outlook https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264122246-en (2012).

European environment agency. Transboundary air pollution, in Environment in the European Union at the turn of the century. European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/92-9157-202-0/3.4.pdf/view (2008).

National Research Council. Global Sources of Local Pollution (National Academies, 2010). https://doi.org/10.17226/12743

Yang, Q. et al. The cross-border transport of PM2.5 from the Southeast Asian biomass burning emissions and its impact on air pollution in Yunnan plateau, Southwest China. Remote Sens. 14 (8), 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14081886 (2022).

Organisation, W. H. Air Pollution. Accessed: Apr. 06, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution#tab=tab_1

World Bank, Striving for Clean Air. Air Pollution and Public Health in South Asia. (Washington, D.C. The World Bank, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1831-8

Zanobetti, A., Schwartz, J. & Dockery, D. W. Airborne particles are a risk factor for hospital admissions for heart and lung disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (11), 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1289/eh001081071 (2000).

Dominici, F. et al. Mar. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 295 (10). 1127. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.10.1127 (2006).

Goudarzi, G. et al. Cardiovascular and respiratory mortality attributed to ground-level Ozone in Ahvaz, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187 (8), 487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-015-4674-4 (2015).

Sunyer, J. & Basagaña, X. Particles, and not gases, are associated with the risk of death in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 30 (5). 1138–1140. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.5.1138 (2001).

Chen, C., Zhao, B. & Weschler, C. J. Assessing the influence of indoor exposure to ‘outdoor Ozone’ on the relationship between Ozone and short-term mortality in U.S. Communities. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 2, 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1289/eh1103970 (2012).

Beelen, R. et al. Effects of long-term exposure to air pollution on natural-cause mortality: an analysis of 22 European cohorts within the multicentre ESCAPE project. Lancet 383, 9919, 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62158-3 (2014).

Crouse, D. L. et al. PM 2.5, O 3, and 2 exposures and associations with mortality over 16 years of follow-up in the Canadian census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC). Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 11, 1180–1186. https://doi.org/10.1289/eh1409276 (2015).

Brauer, M. et al. Mortality-air pollution associations in low-exposure environments (MAPLE): Phase 1. Res. Re Health. Eff. Inst. 203, 1–87. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31909580 (2019).

Wolf, K. et al. Long-term exposure to low-level ambient air pollution and incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of six European cohorts within the Elapse project, Lancet Planet. Heal. 5 (9), e620–e632, Se. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00195-9 (2021).

Dominici, F. et al. Assessing adverse health effects of long-term exposure to low levels of ambient air pollution: implementation of causal inference methods, Res. Re Health. Eff. Inst. 211, 1–56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36193708 (2022).

Pathak, A. K., Sharma, M. & Nagar, K. An approach for cancer risk-based apportionment of PM 2.5 constituents and sources. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 28, 2, 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2022.2033612 (2022).

Maji, K. J. Substantial changes in PM2.5 pollution and corresponding premature deaths across China during 2015–2019: A model prospective. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138838 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138838 (2020).

Pathak, A. K., Sharma, M. & Nagar, K. A framework for PM2.5 constituents-based (including PAHs) emission inventory and source toxicity for priority controls: A case study of Delhi, India. Chemosphere 255, 126971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126971 (2020).

Brauer, M. et al. Mortality-air pollution associations in low exposure environments (MAPLE): Phase 2. Res. Re Health. Eff. Inst. 212, 1–91. https://www.healtheffects.org/system/files/brauer-rr-212-report.pdf (2022).

IQAir World Air Quality Report 2023, IQAir, 1–45, (2023).

Rajesh, Y. India’s Population to Overtake China by mid-2023. (UN estimates, Reuters 2023). https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-have-29-mln-more-people-than-china-by-mid-2023-un-estimate-shows-2023-04-19/

Cutmore, J. Top 10: The Largest Cities in the World, (BBC Science Focus, 2024). https://www.sciencefocus.com/planet-earth/in-pictures-the-largest-cities-in-the-world

Singh, A. K., Pathak, A. K. & Saini, G. Premature mortality risk and associated economic loss assessment due to PM2.5 exposure in Delhi, India during 2015–2019. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal Mar. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-024-01550-1 (2024).

Brown, J. S., Gordon, T., Price, O. & Asgharian, B. Thoracic and respirable particle definitions for human health risk assessment. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 10, 1, (12). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-10-12 (2013).

Manojkumar, N. & Srimuruganandam, B. Age-specific and seasonal deposition of outdoor and indoor particulate matter in human respiratory tract. Atmos. Pollut Res. 13 (2), (101298). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2021.101298 (2022).

Mack, S. M., Madl, A. K. & Pinkerton, K. E. Respiratory health effects of exposure to ambient particulate matter and bioaerosols. Compr. Physiol. 10, (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c180040 (2019).

Thakur, A. K., Kaundle, B. & Singh, I. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems in respiratory diseases, In targeting chronic inflammatory lung diseases using advanced drug delivery systems, Elsevier, 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820658-4.00022-4. (2020).

Morgan, W. K. Industrial bronchitis. Occu Environ. Med. 35 (4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.35.4.285 (1978).

ICRP. Human Respiratory Tract Model for Radiological Protection (ICRP Publication, 1994).

Nordlund, M. et al. Multicomponent aerosol particle deposition in a realistic cast of the human upper respiratory tract. Inhal Toxicol. 29 (3), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958378.2017.1315196 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Evaluation of particulate matter deposition in the human respiratory tract during winter in Nanjing using size and chemically resolved ambient measurements. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 12 (5), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-019-00663-2 (2019).

Hammer, T., Gao, H., Pan, Z. & Wang, J. Relationship between aerosols exposure and lung deposition dose. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 5, 1083–1093. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2020.01.0033 (2020).

Derk, R. et al. Potential in vitro model for testing the effect of exposure to nanoparticles on the lung alveolar epithelial barrier. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 3, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbsr.2014.12.002 (2015).

Dekali, S. et al. Assessment of an in vitro model of pulmonary barrier to study the translocation of nanoparticles. Toxicol. Rep. 1, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxre2014.03.003 (2014).

Nielsen, E. Health effects assessment of exposure to particles from wood smoke. Toxicol. Lett. 172, S120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.05.319 (2007).

Lazaridis, M. Modelling approaches to particle deposition and clearance in the human respiratory tract. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 16 (10), 1989–2002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-023-01386-1 (2023).

European environment agency. Premature deaths due to exposure to fine particulate matter in Europe. Accessed: May 18, 2024. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/health-impacts-of-exposure-to?activeAccordion=

Abdurrahman, M. I., Chaki, S. & Saini, G. Stubble burning: effects on health & environment, regulations and management practices. Environ. Adv. 2, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2020.100011 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Seasonal impact of regional outdoor biomass burning on air pollution in three Indian cities: Delhi, Bengaluru, and Pune. Atmos. Environ. 172, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.10.024 (2018).

Bikkina, S. et al. Air quality in megacity Delhi affected by countryside biomass burning. Nat. Sustain. 2. 3, 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0219-0 (2019).

Kulkarni, S. H. et al. How much does large-scale crop residue burning affect the air quality in delhi? Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (8), 4790–4799. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00329 (2020).

Sembhi, H. et al. Post-monsoon air quality degradation across Northern india: assessing the impact of policy-related shifts in timing and amount of crop residue burnt. Environ. Res. Lett. 15 (10), (104067). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba714 (2020).

Kumari, S., Verma, N., Lakhani, A. & Kumari, K. M. Severe haze events in the Indo-gangetic plain during post-monsoon: synergetic effect of synoptic meteorology and crop residue burning emission. Sci. Total Environ. 768, 145479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145479 (2021).

Lelieveld, J. et al. Nov. Air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels: observational and modelling study, BMJ, e077784, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077784 (2023).

Government of NCT of Delhi. Demographic Profile. In: Economic Survey of Delhi 2022-23, Delhi, 395–413 (2023).

Sharma, S., Khare, M. & Kota, S. H. Action plans to reduce PM2.5 concentrations in hotspots of Delhi-NCR using a one-way coupled modeling approach. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 22 (6), 210377. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.210377 (2022).

Saini & Sharma, M. Cause and Age-specific premature mortality attributable to PM2.5 exposure: an analysis for Million-Plus Indian cities. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 135230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135230 (2020).

Nair, M., Bherwani, H., Mirza, S., Anjum, S. & Kumar, R. Valuing burden of premature mortality attributable to air pollution in major million-plus non-attainment cities of India. Sci. Re. 11 (1), 22771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02232-z (2021).

CPCB. Technical specifications for continuous ambient air quality monitoring (CAAQM) Station(real time), (2015).

Gupta, S. K. & Elumalai, S. Size-segregated particulate matter and its association with respiratory deposition doses among outdoor exercisers in Dhanbad City, India. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 67 (10), 1137–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2017.1344159 (2017).

Azarmi, F. & Kumar Ambient exposure to coarse and fine particle emissions from Building demolition. Atmos. Environ. 137, 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.04.029 (2016).

Kumar & Goel, A. Concentration dynamics of coarse and fine particulate matter at and around signalised traffic intersections. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 18 (9), 1220–1235. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6EM00215C (2016).

Fatima, S., Ahlawat, A., Mishra, S. K., Soni, V. K. & Guleria, R. Respiratory deposition dose of PM2.5 and PM10 before, during and after COVID-19 lockdown phases in Megacity-Delhi, India. MAPAN 37 (4), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12647-022-00548-3 (2022).

Özlü, E. Assessment of exposure effects of indoor particles in different microenvironments. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 14 (12), 2029–2046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-021-01071-1 (2021).

Yifang, W. C. H. & Zhu Aerosol Technology: properties, behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles 3rd edn (Wiley, 2022).

Hinds, W. C. Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles 2nd edn (Wiley, 1999)

Tiwari, S., Chate, D. M., Srivastaua, A. K., Bisht, D. S. & Padmanabhamurty, B. Assessments of PM1, PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in Delhi at different mean cycles. Geofizika 29 (2), 125–141 (2012).

Tyagi, S. et al. Characteristics of absorbing aerosols during winter foggy period over the National capital region of delhi: impact of planetary boundary layer dynamics and solar radiation flux. Atmos. Res. 188, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.01.001 (2017).

Singh, V., Singh, S. & Biswal, A. Exceedances and trends of particulate matter (PM2.5) in five Indian megacities. Sci. Total Environ. 750 , 141461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141461 (2021).

Sharma, D. & Mauzerall, D. Analysis of air pollution data in India between 2015 and 2019. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 22 (2), (210204). https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.210204 (2022).

Adamkiewicz, Ł., Maciejewska, K., Rabczenko, D. & Drzeniecka-Osiadacz, A. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily hospital admissions in 31 Cities in Poland. Atmosphere (Basel). 13 (2), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13020345 (2022).

Board, C. A. R. Inhalable particulate matter and health (PM2.5 and PM10). Accessed: Jun. 06, 2024. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/inhalable-particulate-matter-and-health

Xing, Y. F., Xu, Y. H., Shi, M. H. & Lian, Y. X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 8 (1), E69–74. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.19 (2016).

Schraufnagel, D. E. The health effects of ultrafine particles. Ex. Mol. Med. 52 (3), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-020-0403-3 (2020).

Varghese, S. K., Gangamma, S., Patil, R. S. & Sethi, V. Particulate respiratory dose to indian women from domestic cooking. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 39, 12, 1201–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500444838 (2005).

Gupta, S. K. & Elumalai, S. Exposure to traffic-related particulate matter and deposition dose to auto rickshaw driver in Dhanbad, India. Atmos. Pollut Res. 10. 4, 1128–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2019.01.018 (2019).

Das, A. et al. Size fraction of hazardous particulate matter governing the respiratory deposition and inhalation risk in the highly polluted City Delhi. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30 (5), 11600–11616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22733-2 (2022).

Arbex, M. A. et al. A poluição do ar e o sistema respiratório. J. Bras. Pneumol. 38 (5), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132012000500015 (2012).

Esposito, S. et al. Dec. Impact of air pollution on respiratory diseases in children with recurrent wheezing or asthma, BMC Pulm. Med. 14 (1), 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-130 (2014).

Prabhu, V., Gupta, S. K., Madhwal, S. & Shridhar, V. Exposure to atmospheric particulates and associated respirable deposition dose to street vendors at the residential and commercial sites in Dehradun City. Saf. Health Work. 10 (2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.01.005 (2019).

Tseng, W. J. et al. The toxicity of human lung epithelial cells exposure to PM2.5 and glucose before or after intervention of Guilu erxian Jiao. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 24 (12), 240165. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.240165 (2024).

Izhar, S., Rajput & Gupta, T. Variation of particle number and mass concentration and associated mass deposition during diwali festival. Urban Clim. 24, 1027–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2017.12.005 (2018).

Ghosh, B., Barman, H. C. & Padhy, K. Trends of air pollution variations during pre-Diwali, diwali and post-Diwali periods and health risk assessment using HAQI in India. Discov Environ. 2 (1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44274-024-00082-w (2024).

Singh, D. et al. Study of Temporal variation in ambient air quality during diwali festival in India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 169 (4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-009-1145-9 (2010).

Khan, T. et al. Air pollution trend and variation during a mega festival of firecrackers (Diwali) in context to COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Atmos. Environ. 16 (3), 2022016. https://doi.org/10.5572/ajae.2022.016 (2022).

Garaga, R. & Kota, S. H. Characterization of PM 10 and impact on human health during the annual festival of lights (Diwali). J. Heal Pollut. 8 (20), https://doi.org/10.5696/2156-9614-8.20.181206 (2018).

Daga, M. et al. Assessment of the air quality and its impact on health and environment in India. Indian J. Med. Spec. 10 (3), 117. https://doi.org/10.4103/INJMS.INJMS_15_19 (2019).

Msemburi, W. et al. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 613, 7942, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05522-2 (2023).

Acosta, E. Global estimates of excess deaths from COVID-19. Nature 613, 7942, 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-04138-w (2022).

NISTULA & HEBBAR PM Modi announces 21-day lockdown as COVID-19 toll touches 12. (The Hindu, New Delhi, 2020). https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/pm-announces-21-day-lockdown-as-covid-19-toll-touches-10/article61958513.ece

Henley, J. Global report: lockdowns start to limit Covid-19 spread in Europe. (The Guardian, 2020). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/12/global-report-lockdowns-start-to-limit-covid-19-spread-in-europe

Jiachuan Wu, B. D. B., Smith, S., Khurana, M. & Siemaszko, C. Stay-at-home orders across the country. (NBC News, 2020). https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/here-are-stay-home-orders-across-country-n1168736

Staff, T. W. How Many Migrant Workers Left Cities During the COVID-19 Lockdown? The Wire, Jun. 20, [Online]. (2022). Available: https://thewire.in/labour/how-many-migrant-workers-left-cities-during-the-covid-19-lockdown

Giani, S. et al. Short-term and long-term health impacts of air pollution reductions from COVID-19 lockdowns in China and europe: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 4 (10), e474–e482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30224-2 (2020).

Mishra, S. et al. Rapid night-time nanoparticle growth in Delhi driven by biomass-burning emissions. Nat. Geosci. 16 (3), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01138-x (2023).

Biswal, A. et al. Spatially resolved hourly traffic emission over megacity Delhi using advanced traffic flow data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 15 (2), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-661-2023 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ms. Ruma Ghosh for her professional illustration of the human respiratory tract and its vulnerable regions, as presented in this study. The schematic was created based on conceptual guidance and references provided by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the study and designed the research plan. Amrendra Kumar Singh collected and analysed the data. Amrendra Kumar Singh and Gaurav Saini interpreted the results. Amrendra Kumar Singh drafted the manuscript, and Ashutosh Kumar Pathak & Gaurav Saini provided critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A.K., Pathak, A.K. & Saini, G. Respiratory deposition of particulate matter in Delhi: a five-year assessment of exposure patterns and health risks. Sci Rep 15, 42601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26663-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26663-0