Abstract

This study explores the structure-activity relationships of renieramycin right-half and full-skeleton compounds using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling. Linear (Genetic Algorithm-Multiple Linear Regression, GA-MLR) and non-linear machine learning approaches (Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, and XGBoost) were employed to develop predictive models with quantum chemical and molecular descriptors. The best-performing model, using Support Vector Regressor (SVR), achieved a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.946 for the training set and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.246 for the test set. Key descriptors influencing cytotoxicity included charges at C2 and C4, HOMO energy, and polarizability. External validation with newly synthesized renieramycin right-half derivatives yielded an RMSE of 0.236. The machine learning-based QSAR models demonstrated exceptional accuracy and reliability in cytotoxicity prediction, underscoring their utility in guiding the design of novel renieramycin derivatives. The cytotoxicity test of the newly synthesized renieramycin shows an anomaly than the previous experimental findings, i.e., the O-benzyl containing derivative was more cytotoxic than the hydroxyl or quinone containing renieramycin derivatives. These findings highlight the potential of fine-tuned QSAR methodologies to accelerate the development of highly effective anticancer agents based on renieramycin right-half structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the most significant causes of mortality globally, particularly affecting individuals below the age of 70. In 2019, ASEAN countries reported cancer as the second leading cause of death overall, with Thailand notably ranking it as the primary cause. Among the various cancer types, breast cancer was the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among females, whereas lung cancer was the leading diagnosis among males. In 2020, breast cancer accounted for 2,261,419 new cases, and lung cancer for 2,206,771 new cases worldwide. Lung cancer also represented the highest cancer-related mortality, with 1,796,144 deaths reported globally in the same year1.

Recent advancements have transformed cancer management strategies. For lung cancer, a combination of thoracic surgery, radical radiotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation is now widely implemented. Systemic therapies, particularly chemotherapy, remain a cornerstone in cancer treatment approaches. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), therapeutic strategies have evolved to incorporate targeted and molecularly driven approaches, utilizing genetic insights to optimize treatment outcomes2. However, chemotherapy’s efficacy is frequently compromised by the development of drug resistance. According to Su3 mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and KRAS genes, alongside immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), are significant contributors to NSCLC resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, dysregulation of the TP53, MDM2, and CDKN1A genes has been identified as a key mechanism underlying cisplatin resistance in NSCLC4. This persistent challenge highlights the urgent need for ongoing research into novel anticancer agents.

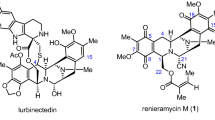

Renieramycins are a class of compounds originally isolated from marine sponges, extensively studied for their bioactive properties. Various strategies have been explored to enhance their efficacy or simplify the complex synthetic pathways required for their production. Among these, right-half renieramycins represent a particularly intriguing group of truncated renieramycin derivatives. The initial synthesis of right-half renieramycin was conducted by Matsubara, et al5. who developed a streamlined synthesis of epiminobenzo[d]azocine, the tricyclic lactam core structure of renieramycins, from ʟ−3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-methyl-phenylalanine and its derivatives, which are themselves derivable from ʟ-tyrosine. This tricyclic lactam structure contains an NH group that can be functionalized with various alkyl groups, allowing for the generation of a diverse range of right-half renieramycin compounds. While the cytotoxicity of these right-half renieramycins was found to be comparable to that of full-skeleton renieramycins, it remains suboptimal for clinical applications, motivating ongoing research into their synthesis6,7,8,9. However, current approaches to synthesizing these derivatives are still largely exploratory and reliant on trial-and-error methods, which can be resource-intensive.

Computational chemistry has become an essential tool in modern drug design and discovery, primarily employed to reduce the time and resources required to identify potent chemical agents. Computational or in silico studies can be categorized based on the data available into four main types: studies with a known receptor structure, known ligand structure, known ligand and receptor structure, and unknown ligand and receptor structure10,11,12. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling typically begins with the generation or compilation of descriptors—variables that describe the structural, electronic, topological, geometrical, or thermodynamic properties of active compounds in relation to their (biological) activities13,14,15,16. These descriptors form the basis of a dataset, to which various chemometric and machine-learning methods are applied to develop predictive models that correlate compound descriptors with biological activity. Common methods for model building include Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Genetic Algorithm-Optimized Multiple Linear Regression (GA-MLR), as well as Principal Component Regression (PCR) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures (OPLS) for linear or assumed-linear relationships. For modeling non-linear correlations, machine learning tools such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are widely employed. These computational approaches allow for more efficient exploration of chemical space and facilitate the rational design of novel therapeutic agents17,18.

QSAR modeling has been successfully applied to explore the biological activities, including anti-cancer or cytotoxicity, of various chemical species. Rahmani, et al19. demonstrated the development of a QSAR model for xanthone derivatives as topoisomerase IIα inhibitors in breast cancer, using Genetic Algorithm Multiple Linear Regression (GA-MLR) and Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LS-SVM) with comparable predictive accuracy. Similarly, Eviana Kusuma Putri, et al20. constructed a QSAR model for 4-anilino coumarins, utilizing descriptors derived from H-GGA DFT/BPV86 calculations combined with the 6-31G basis set in quantum chemical modeling. Goudzal, et al21. applied 2D-QSAR modeling for azacalix[2]arene[2]pyrimidine derivatives as anticancer agents, using Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Multiple Non-Linear Regression (MNLR) combined with descriptors generated from B3LYP/6-31G level calculations, yielding promising results. Nguyen and Patuwo22 found that quantum chemical descriptors, even those generated at a lower level of theory such as HF/3-21G, were effective for constructing QSAR models for anti-colorectal cancer agents. Nevertheless, non-quantum chemical descriptors have also proven beneficial and reliable for anticancer QSAR modeling, particularly when integrated with machine learning algorithms23. However, despite extensive Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) analyses, no publications or studies have yet reported the development of a QSAR model specifically for the anticancer activity of renieramycins.

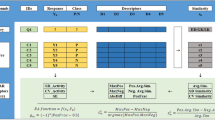

Therefore, this study aimed to employ QSAR analysis to gain deeper insights into the relationship between the structure of the right-half renieramycin derivatives and their anticancer activity, particularly against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The resulting model was intended to guide the design of optimized right-half renieramycin compounds. To develop the QSAR models, two types of descriptors—quantum chemical and non-quantum chemical—were utilized, and two methodological approaches were applied: classical QSAR and machine learning-based QSAR models. An overview of the study’s workflow is shown in Fig. 1.

Data set Preparation

The biological activity data for the compound set were obtained from multiple studies that employed the same cell line (H460, ATCC HTB-177) and method (MTT cytotoxic assay). Cytotoxicity values were scaled to molar concentrations (M) and transformed into pIC50 values (-log(IC50)). A total of twenty-eight compounds, along with their corresponding biological activity data, were identified and tabulated. These data were obtained from the works of Petsri, et al9., Chamni, et al24., Sinsook, et al25., and Petsri, et al7. based on the same experimental conditions. However, the dataset from Ei, et al8. did not include published cytotoxicity data for the H460 cell line. Therefore, the MTT cytotoxicity assay was conducted to obtain the required data, and the results (Fig S1) were integrated with the other datasets. Figure 2 illustrates the template skeleton of the right-half renieramycin along with the structures of the compounds utilized in this study.

The molecular structures of the compounds were constructed and optimized using the DFT-B3LYP functional with a 6-31G(d) basis set. The optimizations were performed using Gaussian 1626, and the results were extracted to derive the quantum chemical descriptors (denoted as X1 – X22, Table S1). Non-quantum chemical descriptors were generated using Materials Studio 8.0 software (denoted as M1 – M109, Table S2). Subsequently, the dataset was divided into training and test sets using the Kennard-Stone algorithm implemented in Python27. Given that the target values exhibited a bimodal distribution, the training-test set division was conducted for each unimodal subset to ensure a representative distribution across the datasets. From this division, the test set for this study comprised Compounds 3 (DH_21), 9 (DH_22), 10 (DH_19), 19 (RT), 22 (RM_H5Pyr), and 26 (RM_5b).

QSAR-ML model Building and statistical evaluation

In this study, two approaches to construct the QSAR model, linear and non-linear, were employed. The linear models were developed using the GA-MLR method in Materials Studio 8.0, which utilizes Genetic Function Approximation (GA) to select optimal descriptors in conjunction with Multiple Linear Regression to construct the model. When necessary, linear spline functions were incorporated to enhance model performance. For model training, a maximum of four variables was permitted for each model, with the population and maximum generations set to 1000 and 500, respectively.

For the construction of non-linear models, machine learning methods were employed. This study utilized three distinct machine learning algorithms: Random Forest, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machine (SVM). Before building the models, the hyperparameters for each method were optimized using Bayesian Optimization28. All machine learning-based model development was conducted in Python, utilizing appropriate packages for implementation.

To evaluate the model, several evaluation metrics were employed. The coefficient of determination (R²) was utilized to assess the model’s ability to explain and predict the dependent variables (target values; y-values) based on the independent variables (features; x-values). An R² value closer to 1.0 indicates a strong relationship and a high capacity for predicting the target values from the features, whereas a value near 0.0 suggests a weak or non-existent relationship. The mathematical formula for R² is as follows:

Where yi is actual y values, ŷi is predicted y values, and ȳ is the mean of actual y values.

R2 CV (LOO) is the coefficient determination of the cross-validation of a model using the Leave-One-Out (LOO) method. The mathematical formula for R2 CV (LOO) is:

Where ŷ−i is the predicted value of yi from the model built without yi. The root-mean-square error (RMSE) is another parameter to measure the accuracy of the model built. It is the square root of mean-square error, which in turn is the average of the sum of the square of residuals. The formula for RMSE is:

The R2 was used to evaluate both training and test set. RMSE was used to evaluate training, test, and validation set. While the R2 CV (LOO) was carried out only to the training set.

To assess model robustness and quantify statistical significance and uncertainty, all models were retrained using a bootstrapping method (n = 1000 replicates). The bootstrap-derived evaluation metrics were used to test significant differences between models, while the aggregated predictions from all replicates were used to calculate 95% prediction intervals. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test at a 95% confidence level. Y-randomization was also used to monitor the overfitting of the models, while standardized residuals plot and PCA plot with Mahalanobis were used to show the Applicability Domain (AD) of the chosen model.

Chemistry and cytotoxicity assessment of evaluation set

Synthesis of (1R,5S)−10-(benzyloxy)−9-methoxy-8,11-dimethyl-3-phenethyl-2,3,5,6-tetrahydro-1,5-epiminobenzo[d]azocin-4(1 H)-one (30).

To a solution of NaH (60% oil dispersion, 172 mg, 4.26 mmol) in DHF (6.0 mL) was slowly added lactam 1 (308 mg, 851 µmol) in DHF (6.0 mL) over 10 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C, after which a solution of (2-iodoethyl)benzene29 (1.02 g, 4.26 mmol) in DHF (6.0 mL) was added dropwise over 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred for 14 h at 100 °C. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O (50 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 100 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a residue. The residue was purified by SiO2 flash column chromatography (CHCl3:MeOH = 49:1) to afford compound 2c (173 mg, 58%) as a colorless gummy.

2c: [α] − 97.2 (c 0.12, CHCl3). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.41–7.31 (5 H, m), 7.15–7.12 (3 H, m), 6.98–6.96 (2 H, m), 6.70 (1H, s), 5.07 (1H, d, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.97 (1H, d, J = 11.4 Hz), 3.95 (1H, d, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.82 (3 H, s), 3.76 (1H, dd, J = 11.9, 4.3 Hz), 3.57 (1H, d, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.53–3.35 (2 H, m), 3.10 (1H, dd, J = 17.3, 6.6 Hz), 2.93 (1H, d, J = 11.9 Hz), 2.77 (1H, d, J = 17.3 Hz), 2.67 (2 H, dt, J = 11.2, 3.5 Hz), 2.29 (3 H, s), 2.26 (3 H, s). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 165.4, 149.4, 148.2, 138.7, 137.5, 131.5, 128.7, 128.6, 128.3, 128.2, 128.2, 126.1, 125.8, 125.8, 74.3, 60.1, 59.1, 51.9, 51.3, 48.3, 39.6, 33.1, 27.2, 15.8. IR (KBr) cm− 1: 2934, 1644, 1494, 1454, 1336, 1061, 753, 699, 666, 406. EI-MS m/z (%): 456 (M+, 25), 365 (11), 295 (24), 294 (100), 204 (30), 203 (35). HR-EI-MS m/z: 456.2409 (M+, calcd for C29H32N2O3, 456.2413). 1H- and13C-NMR spectra are shown in Fig S2 and S3, respectively.

Synthesis of (1R,4R,5S)−10-(benzyloxy)−9-methoxy-8,11-dimethyl-3-phenethyl-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexahydro-1,5-epiminobenzo[d]azocine-4-carbonitrile [3c (NDH_1)]

To a solution of lactam 2c (18.1 mg, 39.6 µmol) in THF (1.0 mL) at 0 °C was slowly added LiAlH2(OEt)2 (1.0 mol/L in CH2Cl2, 476 µL, 476 µmol, 12 equiv.) over 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 3 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with AcOH (47.5 µL, 832 µmol, 21 equiv.), followed by the addition of KCN (17.3 mg, 238 µmol, 6.0 equiv.) in H2O (120 µL), and stirring was continued for 14 h at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was neutralized with 5% NaHCO3 solution and diluted with saturated Rochell’s salt aq., and the mixture was stirred for 1 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 30 mL). The combined extracts were washed with brine (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a residue. The residue was purified by SiO2 flash column chromatography (n-hexane: EtOAc = 4:1) to afford compound 3c (NDH_1, 12.9 mg, 70%) as a colourless oil.

3c (NDH_1): [α] − 28.3 (c 0.37, CHCl3). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.38–7.26 (5 H, m), 7.09–7.02 (3 H, m), 6.75–6.73 (2 H, m), 6.60 (1H, s), 5.07 (2 H, s), 3.92 (1H, s), 3.84 (3 H, s), 3.64 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 3.21 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz), 2.97 (1H, dd, J = 17.8, 7.7 Hz), 2.78 (1H, dd, J = 11.1, 2.9 Hz), 2.70–2.48 (5 H, m), 2.32 (3 H, s), 2.22 (1H, d, J = 17.8 Hz), 2.12 (3 H, s). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 148.9, 148.1, 139.8, 137.5, 130.1, 130.0, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.2, 127.9, 126.5, 125.7, 124.7, 116.7, 74.5, 60.2, 60.1, 56.4, 55.3, 53.4, 52.7, 41.2, 32.6, 25.0, 15.9. IR (KBr) cm− 1: 2935, 1484, 1454, 1322, 1229, 1159, 1065, 901, 754, 699, 667, 483. EI-MS m/z (%): 467 (M+, 0.8), 295 (29), 294 (100), 204 (26), 203 (18). HR-EI-MS m/z: 467.2571 (M+, calcd for C30H33N3O2, 467.2573). 1H- and13C-NMR spectra are shown in Fig S4 and S5, respectively.

Synthesis of (1R,4R,5S)−10-hydroxy-9-methoxy-8,11-dimethyl-3-phenethyl-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexahydro-1,5-epiminobenzo[d]azocine-4-carbonitrile [4c (NDH_2)]

To a solution of 3c (37.7 mg, 80.6 µmol) and pentamethylbenzene (125 mg, 806 µmol, 10 eq.) in CH2Cl2 (9.5 mL) was added BCl3 (1.0 mol/L in CH2Cl2, 403 µL, 403 µmol, 5.0 eq.) over 30 min at − 78 °C and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and quenched with saturated NaHCO3 solution (50 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo to give a residue. The residue was purified by SiO2 flash column chromatography (n-hexane: EtOAc = 2:1) to afford compound 4c (27.3 mg, 90%) as a colourless amorphous.

4c (NDH_2): [α] − 62.0 (c 0.10, CHCl3). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26–7.03 (3 H, m), 6.79 (2 H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz), 6.39 (1H, s), 5.60 (1H, brs), 4.07 (1H, s), 3.78 (3 H, s), 3.69 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 3.26 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.01 (1H, dd, J = 17.6, 7.8 Hz), 2.89–2.82 (2 H, m), 2.73–2.52 (4 H, m), 2.35 (3 H, s), 2.31 (3 H, s), 2.24 (1H, d, J = 17.6 Hz). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.3, 142.8, 139.8, 130.6, 128.7, 128.0, 127.9, 125.7, 120.8, 119.4, 116.7, 60.8, 60.1, 56.4, 55.5, 52.7, 52.4, 41.5, 32.7, 25.0, 15.8. IR (KBr) cm− 1: 3420, 2934, 1586, 1498, 1455, 1328, 1230, 1158, 1061, 755, 700. EI-MS m/z (%): 377 (M+, 1), 205 (25), 204 (100). HR-EI-MS m/z: 377.2101 (M+, calcd for C23H27N3O2, 377.2103). 1H- and13C-NMR spectra are shown in Fig S6 and S7, respectively.

Synthesis of (1R,4R,5S)−9-methoxy-8,11-dimethyl-7,10-dioxo-3-phenethyl-1,2,3,4,5,6,7,10-octahydro-1,5-epiminobenzo[d]azocine-4-carbonitrile [5c (NDH_3)]

To a solution of phenol 4a (8.4 mg, 22.3 µmol) in THF (0.6 mL) was added salcomine (9.5 mg, 22.3 µmol, 1.0 eq.) at rt, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h under O2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was filtered through a cellulose pad and washed with CH2Cl2. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to give a residue. The residue was purified by SiO2 flash column chromatography (n-hexane: EtOAc = 2:1) to afford compound 5c (NDH_3) (6.7 mg, 77%) as a yellow gummy.

5c (NDH_3): [α] − 16.5 (c 0.26, CHCl3). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.13–7.05 (3 H, m), 6.98 (2 H, dd, J = 7.4, 1.9 Hz), 3.99 (3 H, s), 3.77 (1H, s), 3.65 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz), 3.25 (1H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.86–2.76 (3 H, m), 2.67–2.55 (4 H, m), 2.28 (3 H, s), 1.95 (3 H, s), 1.94 (1H, d, J = 20.6 Hz). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 186.6, 182.3, 155.0, 140.8, 139.0, 136.8, 128.7, 128.3, 128.2, 126.0, 116.1, 60.9, 59.2, 54.9, 54.5, 51.2, 50.8, 41.4, 32.6, 20.8, 8.7. IR (KBr) cm− 1: 2942, 1651, 1454, 1372, 1308, 1236, 1158, 949, 867, 758, 699. EIMS m/z (%) 391 (M+, 13), 301 (13), 300 (74), 220 (22), 219 (100), 204 (31), 201 (11), 176 (13), 105 (13). HREIMS m/z 391.1896 (M+, calcd for C23H25N3O3, 391.1896). 1H- and13C-NMR spectra are shown in Fig S8 and S9, respectively.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic assay of untested compounds. The cytotoxicity of the untested compounds was evaluated against the NCI-H460 (ATCC HTB-177) human large-cell lung cancer line using the MTT assay. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, ʟ-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. All untested compounds were initially dissolved in 100% DMSO to prepare stock solutions, which were subsequently diluted to the desired concentrations with culture medium immediately before use. The final DMSO concentration in each well was maintained below 0.5% v/v. Reduced MTT (insoluble formazan) was dissolved in DMSO prior to absorbance measurement using a microplate spectrophotometer.

Results and discussions

Anticancer activity of Renieramycins and Renieramycin right-half compounds against H460 NSCLC cell line

The cytotoxicity of renieramycin right-half compounds was compiled from four distinct research reports that utilized the same method, specifically the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyl-2 H-tetrazolium bromide) assay, against the NCI-H460 lung cancer cell line. All studies were conducted in the same laboratory, the Centre of Excellence in Cancer Cell and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University. Therefore, it is expected that the testing conditions will be consistent, yielding reliable and comparable results. The MTT assay is widely regarded as the gold standard for cytotoxicity assessment30.

Compounds 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7, which were previously reported8, had not been tested against the H460 cell line. To establish a comprehensive dataset with IC50 values against H460, these compounds were subsequently evaluated using the same assay method (Fig S1). The results indicated a trend consistent with previous findings, where DH_32 exhibited the lowest IC50 (indicating the highest cytotoxicity) and DH_35 demonstrated the lowest cytotoxicity among the tested compounds. Given that both the prior report and the current study focused on NSCLC cell lines, it is reasonable to infer that the cytotoxicity profiles across different cell lines are likely to be highly correlated.

Feature selection

Prior to constructing the QSAR model, the dataset underwent a comprehensive preparation process. This involved the removal of descriptors with non-numerical values that could not be converted to a numeric format, as well as those exhibiting low variability (Var(Descriptors) = 0) and inter-correlation coefficients or Pearson correlation exceeding ± 0.9 (|r| > 0.9) with other descriptors. One descriptor from each pair with |r| > 0.9 was discarded based on its variance (lower variance was discarded), correlation with the target (lower correlation was discarded), and biological and chemical interpretability. Such measures were implemented to mitigate multicollinearity, which can inflate the biases in the dataset and compromise the generalization capabilities of the regression model, ultimately reducing its predictive accuracy for unseen data31.

To select features within each feature set—quantum chemical (QC) and non-quantum chemical (MS)—genetic algorithms (GA) and Random Forest-based variable importance (VI) assessments were employed. The GA feature sets were derived from the genetic algorithm-multiple linear regression fitting conducted in Materials Studio, while the VI feature sets were obtained through Random Forest regression using default hyperparameters. Figure 3A and B illustrate the variable importance of the top 20 features from each feature set, along with the correlation heatmap (Fig. 3C) of the features utilized in this study. All the chosen quantum descriptors are electronic descriptors, while the non-quantum descriptors are combination of constitutional, geometrical, and electro-topological descriptors. Observing the correlation coefficients of selected descriptors in Fig. 3C, it is evident that all the descriptors, in each set, are not highly inter-correlated. The selected feature sets employed for the QSAR model development are summarized in Fig. 3D as well.

Classical QSAR

Genetic Algorithm – Multiple Linear Regression (GA-MLR) is a statistical approach that integrates the genetic algorithm, an evolutionary optimization technique inspired by natural selection and genetics, with multiple linear regression. In this method, the genetic algorithm is employed to select the descriptors that will be utilized to train the linear regression model32. Table S3 presents the QSAR model for renieramycin right-half compounds developed using the GA-MLR method in Materials Studio 8.0. The linear equations for both models are:

pIC50 = 7.224 * X2–21.541 * X4 + 0.003 * X15–1.748 * X16–6.165 (GA-QC-MLR).

pIC50 = 1.674 * M2 + 0.105 * M52 + 4.975 * M67 + 15.166 * M102–2.013982 (GA-MS-MLR).

The R2 values of the models are more than 0.9, indicating their reliability. The R2 CV values of both models are reasonably close to the R2 values (0.869 and 0.880 for GA-QC-MLR and GA-MS-MLR, respectively), suggesting that the models demonstrate stability and generalization capabilities. For the quantum chemical descriptor model, the charge of C2 (X2) and polarizability (X15) showed positive correlations with pIC50, while the charge of C4 (qC4) and the energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) were negatively correlated. This suggests that to increase the pIC50, it is advantageous to have a more positively charged atom at the C2 position, higher polarizability, a more negatively charged (or near-neutral) atom at C4, and lower HOMO energy.

In contrast, for the non-quantum chemical descriptor model, all descriptors were positively correlated with pIC50. Based on the coefficients, the most impactful descriptor was RPCG (M102), followed by the shadow area fraction in the ZX plane (M67), the number of methoxy groups (M2), and E-state keys (sums) of an oxygen atom with two single bonds (S_ssO, M52). To enhance the pIC50 of right-half renieramycin compounds, strategies may include increasing the number of methoxy groups (which affect M2 and M52), adding functional groups or altering the conformation to expand the shadow area fraction in the xz plane (M67), and incorporating highly positively charged atoms or reducing overall positive charge (M102). It is important to note that these coefficients are based on unnormalized data, so the magnitude of each coefficient is actually not directly proportional to each other. The plot of experimental vs. predicted pIC50 of GA-MS-MLR model is presented in Fig. 4A.

Based on the evaluation metrics, it is evident that the non-quantum chemical descriptors (MS) yielded a model with a lower root mean square error (RMSE) for both the training and test sets (0.411 and 0.264, respectively). This finding suggests that, within the context of the linear model, the non-quantum chemical descriptors are more effective in predicting and generalizing the structure-activity relationships of renieramycin right-half compounds. The classical QSAR models resulted in the high predictive R2 and R2 CV, however, the RMSE values of training and test set are still slightly high, therefore, the machine learning-based QSAR is supposed to apply for enhancing model prediction.

Machine learning based QSAR

Machine learning is a statistical/data science method that was initially developed in the 1950s. This methodology experienced a period of stagnation but saw a resurgence in the 1990 s and gained increasing popularity in contemporary times. Machine learning is extensively employed for the processing of big data, encompassing both volumetric and intricate datasets33. It has been also widely used to help build QSAR/QSPR models of various compounds and materials34,35,36.

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble-type machine learning method that uses a combination of decision tree predictors. Each decision tree has its strengths and errors, and random forest will use those to make stronger predictors with lower errors. The trees are built using a random selection of features to split each node, and because it uses a lot of “trees” like “forest”, hence the name Random Forest37. RF has been widely used to build QSAR/QSPR models38,39 with notably good performance.

The machine learning methods to be used in this study to build the QSAR model were random forest (RF), support vector regression (SVR), and eXtreme gradient boost (XGB). RF, as mentioned above, is one of the developments of the decision tree method17. It used randomized built trees (resembling “forest”) to overcome the tendency of decision trees to overfit the test set. SVR is the extension regression method of Vapnik’s support vector machine40. It is based on the idea of fitting a hyperplane in high-dimensional space to represent the relationship between features and target values in a mostly non-linear manner. Meanwhile, XGBoost is another development of decision tree41. Similar to the random forest, it is an ensemble learning algorithm. However, instead of building a set of randomized trees, XGBoost combines the strength of gradient boosting and decision tree algorithms. Boosting is a meta-algorithm that works by training a series of weak learners, and each focuses on the mistakes or misclassifications made by the previous ones, hence, the final model will have strong predictive accuracy42.

The experimental vs. predicted pIC50 of training (●) and test (×) set were obtained from the selected QSAR models. The figure shows the top 5 models among all, i.e., (A) GA-QC-RF, (B) GA-QC-SVR, (C) GA-MS-SVR, (D) GA-MS-XGB, and (E) GA-MS-MLR. RF: Random Forest, SVR: Support Vector Regression, XGB: eXtreme Gradient Boosting/XGBoost, GA: genetic algorithm feature selection, VI: variable importance feature selection, QC: quantum chemical descriptors, MS: non-quantum chemical descriptor.

Figure 4 illustrates the graphical representation of experimental versus predicted pIC50 values obtained from the selected machine learning-based QSAR model. Based on the evaluation metrics employed in this study, include R2, R2 CV (LOO), and RMSE, 5 models were chosen, namely GA-MS-MLR (Fig. 4A), GA-QC-RF (Fig. 4B), GA-MS-SVR (Fig. 4C), GA-QC-SVR (Fig. 4D), and GA-MS-XGB (Fig. 4E). A superior model is expected to exhibit a larger R2 value (approaching 1.0), with a R2 CV (LOO) value that is closely aligned R2, and a smaller RMSE for both the training and test sets. Additionally, models exhibiting a more linear correlation between experimental and predicted biological activity are more effective. Table S4 presents a comparison of QSAR models constructed using machine learning-based evaluation methods. The R2 values of all machine learning models range from 0.8 to 1.0, while the R2 CV (LOO) values vary from 0.6 to 0.9, which are considered reasonable. Analysis of the RMSE values indicates that the models employing the variable importance (VI) feature selection method in conjunction with the XGBoost algorithm demonstrate the poorest predictive performance for the test set. This observation suggests that the combination of VI feature selection and the XGBoost algorithm results in a model that overfits the training data. In contrast, the genetic algorithm (GA) feature selection method combined with the same algorithm yielded notably superior, if not the best, evaluation metrics.

When comparing all generated models, both from GA-MLR and machine learning-based methods, the evaluation metrics demonstrate a high degree of comparability. Among these models, the one produced by combining descriptors selected through a genetic algorithm and employing the XGBoost algorithm (GA-MS-XGB, Fig. 4E) emerged as the superior model, exhibiting high R2 values and low RMSE metrics. This observation aligns with previous reports that advocate for the use of XGBoost and Support Vector Regression (SVR) when training QSAR regression models with limited datasets43.

QSAR model evaluation and applicability domain

To evaluate the predictive capability of the developed QSAR model, three novel renieramycin right-half derivatives were synthesized and subsequently tested for cytotoxicity against H460 cells. These compounds, designated as NDH_1, NDH_2, and NDH_3, share a common side group attached to the N-3 position of the tricyclic tetrahydroisoquinoline framework but differ in their functional groups at the aromatic moiety. The synthesis of these derivatives was conducted following the methodologies previously reported in the literature5,6,7,8,9. The synthesis pathway and the cytotoxicity results for the newly synthesized renieramycin right-half derivatives are illustrated in Fig. 5.

The predicted pIC50 values for the three newly synthesized compounds indicate that the models using non-quantum feature sets (MS) overestimate the activity of NDH_1, with a predicted pIC50 of approximately 7 compared to an experimental pIC50 of 5.311. This discrepancy suggests that the prediction models, which were developed based on both right-half and full-skeleton renieramycins, may exhibit a bias towards the full-skeleton derivatives. However, the MS feature sets provide predicted pIC50 values that align with previous findings, indicating that the O-benzyl substituted compound has the lowest pIC50, followed by the hydroxyl (OH) substituted compound, while the quinone-containing compound exhibits the highest pIC50 values5,9.

Interestingly, the current results indicate a different trend: the O-benzyl substituted compound, NDH_1, demonstrates a lower pIC50 compared to the other compounds. Based on the RMSE of the predicted values from this additional validation set, the GA-QC based models (GA-QC-RF and GA-QC-SVR) were determined to be the most effective among all the models evaluated. Furthermore, the trend observed in the predicted values did not align with the experimental data, ranking the compounds as follows: O-benzyl > hydroxyl > quinone, which differs from the trends reported in previous studies5. This anomaly may be attributed to the increased molecular length and degree of freedom introduced by the addition of a methylene group at the N-3 atom compared to 11 and 12 from the training set, which may facilitate better interactions with the binding site of its protein target that typically located deep within a hydrophobic pocket. This trend can be found as well in the data set for QSAR training, particularly for the pyridine-containing derivatives, but from different published reports7,8. The pyridine-containing derivatives with O-benzyl moiety showed higher cytotoxicity than their quinone counterparts. In addition, a report by Phookphan, et al44. demonstrated a similar trend. This publication was released after the present models had been finalized and deployed; therefore, its data were not included in the training or validation sets. In that study, consistent with the results reported here, the compound containing hydroxyl moiety exhibited higher cytotoxicity, followed by that with O-benzyl group, while the quinone-containing compound (DH_32) showed the lowest activity. Notably, the quinone derivative displayed significantly reduced cytotoxicity, with IC50 values up to 12-fold higher than those of the hydroquinone-based analogues. These findings suggest that the current structure–activity relationship (SAR) assumptions regarding the benzo-ring moiety in right-half renieramycins may need to be revisited and refined.

To further evaluate the robustness of the top five models against overfitting and their predictive performance, we retrained them using bootstrap resampling (n = 1,000 replicates). Bootstrapping, a widely used resampling technique in QSAR studies, enhances model validation by simulating dataset variability. This method generates new training sets of equal size to the original data by randomly selecting compounds with replacement, allowing repeated instances of the same data point45,46. Additionally, Y-randomization was performed to confirm that the models’ performance was not attributable to chance correlations. Figure 6 compiles all the additional evaluation metrics and plots.

From the statistical test of bootstrapped-models’ evaluation metrics (Fig. 6a), GA-QC-RF and GA-MS-MLR are significantly better than the other models in terms of training and CV (LOO) metrics. Meanwhile, GA-MS-MLR is significantly worse than the other model and no model is significantly better than the other in terms of R2test. GA-MS-XGB is significantly the best in terms of RMSEtest, while GA-QC-SVR is significantly the worst. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that all the parameters still can be considered good (except for R2 test of GA-MS-MLR) and show robustness of the models.

(A) Evaluation metrics of the top five models retrained using bootstrap resampling. Different letter annotations indicate statistically significant differences among models for each evaluation metric (p < 0.05). (B) Plot of R² and RMSE values from Y-randomization tests. (C) Experimental vs. predicted pIC₅₀ values from bootstrap-resampled models. The grey area represents the 95% prediction interval (PI) based on ordinary least squares (OLS) fitting, while the vertical bars represent 95% PIs derived from bootstrap calculations.

The Y-randomization results (Fig. 6b) revealed notable trends. Across all models, except for GA-MS-XGB, which consistently performed poorly across all Y-randomization metrics, the RMSE values following randomization increased by approximately three- to four-fold compared to those from the original dataset. This outcome indicates that the original models performed significantly better than those trained on randomized responses, confirming that the models are not simply fitting noise.

However, the R² values for the Y-randomized GA-QC-RF and GA-MS-SVR models remained relatively high, around 0.5–0.6. This suggests that part of their good performance in the original dataset may be attributed to chance correlations. In contrast, the R² values for the Y-randomized GA-QC-SVR and GA-MS-MLR models dropped to around 0.2, indicating a lower risk of overfitting due to random associations. Considering that GA-MS-MLR exhibited poor predictive power based on bootstrapped R2test and RMSEval, GA-QC-SVR emerges as the most reliable model for predicting the cytotoxicity of right-half renieramycin derivatives. Furthermore, the plots of experimental versus predicted pIC₅₀ values from the bootstrapped models show that the 95% prediction intervals (PIs) for GA-QC-based models, particularly GA-QC-SVR, are visually narrower than those of GA-MS-based models. This observation further supports the superior predictive precision and reliability of the GA-QC-SVR model. This finding consistent with the earlier recommendations suggesting that SVR or XGBoost are preferable algorithms for QSAR regression modeling with small datasets43. However, we also found that XGBoost was not very suitable for small datasets, because it tends to overfit the model.

For the applicability domain (AD), two methods were used: standardized residuals plot and Mahalanobis distance in principal component (PC) space (Fig. 7). The standardized residuals plot (Fig. 7a) show the standardized residuals versus the predicted pIC50, allowing the identification of response outliers (standardized residuals > ± 3). The PC plot (Fig. 7b) shows the distribution of data points in the reduced multivariate space, helping visualize the spread and clustering of compounds based on their descriptors. The Mahalanobis distances in the PC plot show the statistical boundaries of the model’s chemical space, where compounds falling outside the 95% confidence threshold are considered outside the model’s reliable prediction zone47,48.

In William’s plot (Supplementary, Fig. S10a), one compound, DH_25, exceeds the leverage threshold, indicating that it has a disproportionately large influence on the model due to its unique descriptor profile. However, DH_25 does not exceed the standardized residual threshold (± 3), suggesting that although it is structurally influential, its predicted activity aligns well with the experimental value. This implies that the model can still reliably predict its biological activity despite its outlier leverage value. In the principal component (PC) space plot (Fig. S10b), two compounds, DH_25 and DH_38, fall outside the 95% Euclidean distance threshold, which identifies structural outliers based on linear distance from the data centroid. Among the two, DH_38 is located closer to the threshold, suggesting it is only marginally outside the domain. Importantly, both compounds remain within the Mahalanobis distance threshold, which accounts for covariance among variables and offers a more stringent, multivariate definition of the chemical space. This indicates that neither DH_25 nor DH_38 are statistical outliers when descriptor correlation is considered, and thus their predictions are still considered to be within a reliable domain. Further insight from the PC loading plots revealed that the HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital) energy was the most influential feature contributing to DH_25’s deviation from the rest of the dataset. This suggests that DH_25 may possess a significantly different electronic property profile, potentially affecting its interaction with the biological target. Such differences could be biologically relevant and may offer a rationale for its strong influence on the model.

SHAP analysis and descriptors explanation

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was subsequently conducted to provide deeper insights into the QSAR model output. SHAP is an algorithm grounded in game theory, designed to elucidate the effects and significance of each feature or descriptor utilized in constructing a machine-learning model49. The results of the SHAP analysis for the GA-QC features employed in the GA-QC-SVR model are presented in Fig. 8.

The SHAP analysis indicates that a higher SHAP value for a descriptor correlates with a greater positive contribution to the target value. In this analysis, the descriptor qC2 (X2) emerged as the most influential in determining the pIC50 of renieramycin right-half derivatives. A positive charge at position number 2 is associated with an increase in pIC50 up to 0.6 points. In contrast, a more negative charge at position number 4 is favorable for achieving a higher pIC50. The charge of atom position number 4 should be less than − 0.06 to get increment up to 0.2 points in pIC50, bigger than that it will reduce pIC50 up to 0.6 instead. This suggests that functional groups exhibiting a -I effect, or electronegative character, are more advantageous at C-2, while those with a + I effect, or electropositive character, are preferable at C-4. However, it has been reported that electron-withdrawing groups, such as hydroxyl or nitrile, play a significant role in the DNA-adduct mechanism of renieramycins50. Thus, an alternative strategy may be needed to achieve a more negative charge at C-4. Additionally, compounds with higher polarizability and lower HOMO energy are predicted to exhibit higher pIC50 values, to a certain degree. The polarizability value of the compound should be around 500–600 to increase pIC50 up to 0.4 points, but if it reaches 700 it will only add around + 0.2 points to the pIC50.

SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) analysis of the GA-QC-SVR model’s descriptors/features. It is arranged from the most important (top-left) to the least (bottom-right), the descriptors are (A) Charge of C2 (qC2, X2), (B) Charge of C4 (qC4, X4), (C) Polarizability (X15), and (D) Energy of Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO, in eV, X16).

Polarizability is a property of a molecule or atom that reflects its ability to become polarized in response to an electric field. Experimentally, polarizability is typically determined through measurements of the dielectric constant or refractive index51. In this study, static polarizability is utilized, which is obtained via numerical differentiation of field-dependent energy calculated by the quantum chemical software52. Generally, molecules or atoms with high electron density or a limited number of vacant orbitals exhibit lower polarizability53. Thus, one approach to enhancing polarizability is by increasing the molecular volume and/or adding a side group with a less-packed electron. Meanwhile, according to Koopman’s theorem, vertical ionization potential corresponds to the energy of the first occupied orbitals which, in the case of Kohn-Sham DFT, is the same as HOMO energy54. Hence, the addition of electron-withdrawing groups can plausibly decrease the HOMO energy. In terms of drug–target interactions, increased polarizability of a drug molecule generally enhances its ability to engage in dipole–dipole or charge–dipole interactions with target biomolecules55,56. Additionally, there is a known negative correlation between proton affinity and the absolute value of the HOMO energy: as the HOMO energy becomes more extreme (either more negative or more positive), the molecule’s proton affinity tends to decrease57. According to SHAP analysis, the more cytotoxic right-half renieramycins tend to exhibit both higher polarizability (up to a certain threshold) and more negative HOMO energies. This suggests that right-half renieramycins are likely to preferentially interact with biological targets that possess electron-deficient or partially positive regions, such as polar or positively charged amino acid residues, through favorable charge–dipole or dipole–dipole interactions. Furthermore, the lower proton affinity and more negative HOMO energy may facilitate electron donation in specific microenvironments, potentially influencing binding affinity or redox-related mechanisms.

Rationally designing Renieramycin Right-Half compounds

The design of novel renieramycin right-half compounds will utilize retrosynthetic analysis. Figure 9illustrates the retrosynthetic pathway for right-half renieramycin as described by Matsubara, et al5. The formation of the tricyclic lactam involves the Pictet-Spengler cyclization of an N-protected amino aldehyde with ʟ-tyrosine derivative, which can be readily synthesized following the method outlined by Liao et al58.. The amino aldehyde employed by Matsubara et al5. was N-protected amino acetaldehyde 38, a derivative of glycine 39. Additionally, the incorporation of the arylmethyl group onto the lactam nitrogen can be achieved through alkylation using alkyl bromides.

According to the SHAP analysis of the selected QSAR model, modifications at C2 are essential for developing more effective renieramycin right-half compounds. These modifications can be implemented by utilizing different amino aldehydes and arylmethyl bromides, as suggested by the retrosynthetic analysis. Given that aminoacetaldehyde is derived from glycine, it is feasible to synthesize other amino aldehydes from various amino acids. Ivkovic, et al59. reported that α-amino aldehydes can be synthesized through the reduction of N-protected α-amino acids using CDI/DIBAL-H in a one-pot reaction. In their study, reductions of Cbz-alanine, Cbz-leucine, and Cbz-phenylalanine achieved yields of up to 99% with enantiomeric excess (ee) exceeding 97%. Another critical descriptor highlighted in the SHAP analysis is polarizability, which can potentially be enhanced by incorporating elements with large van der Waals volumes and high electron counts, such as halogens (excluding fluorine) and elements from periods 3 and above.

Based on the insights from the analyses, a series of novel renieramycin right-half compounds were designed (Fig S11). The structures of these newly conceived compounds were prepared and optimized using the same computational methods applied to the training set. The biological activity of the rationally designed renieramycin right-half compounds was then predicted (Table S5) using the selected model, specifically the GA-QC-SVR. The spread of predicted pIC50 of rationally designed novel right-half renieramycins as well as the structure of the compound with pIC50 more than 6.5 are presented in Fig. 10. The predicted pIC50 values for the novel right-half renieramycins ranged from 4.868 to 7.333, with the highest predicted pIC50 of 7.333 associated with compound REN3VN6, which incorporates valine as the amino aldehyde, benzyloxy at the benzo-ring of main skeleton, and dichlorobenzene as R3 substituents.

Notably, most of the compounds designed in this study exhibited pIC50 values higher than those of the synthesized right-half renieramycins used in the QSAR model, and some even higher than those of the full-skeleton renieramycins. Despite this, the synthesis of these rationally designed compounds is warranted to enhance the understanding of the structure-activity relationship of right-half renieramycins.

Conclusions

This study successfully established quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models for right-half renieramycin derivatives using both linear (GA-MLR) and non-linear machine learning techniques (Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, and XGBoost), in combination with genetic algorithm-based feature selection. Among these, the GA-QC-SVR model, which integrates quantum chemical descriptors, demonstrated the most reliable predictive performance, with high R² values and low root mean square errors (RMSE) across training, test, and validation datasets. Bootstrap resampling and Y-randomization further confirmed the robustness of GA-QC-SVR, with narrower 95% prediction intervals and low susceptibility to chance correlation compared to other models.

The integrated SHAP analysis revealed that polarizability, HOMO energy, and partial charges at C2 and C4 positions are key determinants of cytotoxicity. A moderate increase in polarizability and more negative HOMO values were associated with enhanced activity, suggesting favorable dipole-related interactions with electron-deficient targets. In particular, compounds with hydroxyl or O-benzyl substituents showed higher cytotoxicity, while quinone-containing derivatives like DH_32 exhibited significantly lower potency, corroborating recent independent reports. This phenomenon needs to be observed further in the future experiments. Applicability domain (AD) analysis using William’s plot, Mahalanobis, and Euclidean distance metrics identified DH_25 as an influential but well-modeled compound, with HOMO energy being a distinguishing factor. These analyses validated the model’s generalizability and offered mechanistic insights into compound behavior within chemical space.

Overall, the findings from this research not only advance the understanding of the structure-activity relationships governing renieramycin derivatives but also establish a robust framework for the rational design of novel compounds. Future studies aimed at synthesizing the proposed compounds are needed to contribute to the development of more effective anticancer agents and enhance the therapeutic potential of renieramycins.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The scripts and pre-trained models used and generated in this study can be found in https://github.com/imeldp96/qsar-renieramycin.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Jones, G. S. & Baldwin, D. R. Recent advances in the management of lung cancer. Clin Med (Lond) 18, s41-s46 https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.18-2-s41 (2018).

Su, C. Emerging insights to lung cancer drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 5, 534–540. https://doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2022.61 (2022).

Kryczka, J., Kryczka, J., Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K. H. & Brzeziańska-Lasota, E. Molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance induced by cisplatin in NSCLC cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168885 (2021).

Matsubara, T., Yokoya, M., Sirimangkalakitti, N. & Saito, N. Asymmetric synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of Right-Half models of antitumor Renieramycin marine natural products. Mar. Drugs. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/md17010003 (2019).

Phookphan, P. et al. A new Renieramycin T Right-Half analog as a small molecule degrader of STAT3. Mar. Drugs. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/md22080370 (2024).

Petsri, K. et al. Novel synthetic derivative of Renieramycin T Right-Half analog induces apoptosis and inhibits cancer stem cells via targeting the Akt signal in lung cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065345 (2023).

Ei, Z. Z. et al. Simplified Synthesis of Renieramycin T Derivatives to Target Cancer Stem Cells via beta-Catenin Proteasomal Degradation in Human Lung Cancer. Mar Drugs 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/md21120627 (2023).

Petsri, K. et al. Structure-Activity relationships and molecular Docking analysis of Mcl-1 targeting Renieramycin T analogues in Patient-derived lung cancer cells. Cancers (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12040875 (2020).

Cavasotto, C. N., Aucar, M. G. & Adler, N. S. Computational chemistry in drug lead discovery and design. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 119, e25678. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.25678 (2019).

Yu, W. & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. Computer-Aided drug design methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 1520, 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6634-9_5 (2017).

Niazi, S. K. & Mariam, Z. Computer-Aided drug design and drug discovery: A prospective analysis. Pharmaceuticals 17, 22 (2024).

Danishuddin & Khan, A. U. Descriptors and their selection methods in QSAR analysis: paradigm for drug design. Drug Discovery Today. 21, 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2016.06.013 (2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Cherkasov, A. et al. QSAR modeling: where have you been? where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 57, 4977–5010. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm4004285 (2014).

Guan, D., Lui, R. & Mattthews, S. T. Low-cost quantum mechanical descriptors for data efficient skin sensitization QSAR models. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 7, 100183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2024.100183 (2024).

Xu, Y., Liaw, A., Sheridan, R. P. & Svetnik, V. Development and evaluation of conformal prediction methods for quantitative Structure-Activity relationship. ACS Omega. 9, 29478–29490. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c02017 (2024).

Svetnik, V. et al. Random forest: A classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 43, 1947–1958. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci034160g (2003).

Neves, B. J. et al. QSAR-Based virtual screening: advances and applications in drug discovery. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01275 (2018).

Rahmani, N., Abbasi-Radmoghaddam, Z., Riahi, S. & Mohammadi-Khanaposhtanai, M. Predictive QSAR models for the anti-cancer activity of topoisomerase IIα catalytic inhibitors against breast cancer cell line HCT15: GA-MLR and LS-SVM modeling. Struct. Chem. 31, 2129–2145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-020-01543-7 (2020).

Eviana, K. et al. The predicted models of anti-colon cancer and anti-hepatoma activities of substituted 4-anilino coumarin derivatives using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR). J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 34, 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101837 (2022).

Goudzal, A., Hadaji, E., Bouachrine, M., El Hamdani, H. & Ouammou, A. QSAR and Docking molecular models to predict anti-cancer activity on a series of Azacalix [2] Arene [2] pyrimidine derivatives as anticancer agents. Mater. Today: Proc. 51, 1831–1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.002 (2022).

Nguyen, H. N. B. & Patuwo, M. Y. Quantitative Structure-Activity relationship (QSAR) modelling of the activity of anti-colorectal cancer agents featuring quantum chemical predictors and interaction terms. Results Chem. 5, 100888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2023.100888 (2023).

Khan, S., Sarfraz, A., Prakash, O. & Khan, F. Machine learning-based QSAR modeling, molecular docking, dynamics simulation studies for cytotoxicity prediction in MDA-MB231 triple-negative breast cancer cell line. J. Mol. Struct. 1315, 138807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138807 (2024).

Chamni, S., Sirimangkalakitti, N., Chanvorachote, P., Suwanborirux, K. & Saito, N. Chemistry of Renieramycins. Part 19: Semi-Syntheses of 22-O-Amino ester and hydroquinone 5-O-Amino ester derivatives of Renieramycin M and their cytotoxicity against Non-Small-Cell lung cancer cell lines. Mar. Drugs. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/md18080418 (2020).

Sinsook, S. et al. Light-Mediated Transformation of Renieramycins and Semisynthesis of 4’-Pyridinecarbonyl-Substituted Renieramycin-Type Derivatives as Potential Cytotoxic Agents against Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Mar. Drugs. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/md21070400 (2023).

Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01 (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Kennard, R. W. & Stone, L. A. Computer aided design of experiments. Technometrics 11, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00401706.1969.10490666 (1969).

Nogueira, F. (2014).

Ai, H. J., Wang, H., Li, C. L. & Wu, X. F. Rhodium-Catalyzed carbonylative coupling of alkyl halides with phenols under low CO pressure. ACS Catal. 10, 5147–5152. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c00933 (2020).

Ghasemi, M. et al. Utility, Limitations, Pitfalls, and interpretation in bulk and Single-Cell analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312827 (2021).

Kalnins, A. When does multicollinearity bias coefficients and cause type 1 errors? A reconciliation of Lindner, Puck, and Verbeke (2020) with Kalnins (2018). J. Int. Bus. Stud. 53, 1536–1548. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00531-9 (2022).

Ely Setiawan, M. M. Quantitative structure–activity relationship study to predict the antibacterial activity of gemini quaternary ammonium surfactants against Escherichia coli. 12 (7), (2022).

Çeli̇k, Ö. A research on machine learning methods and its applications. J. Educational Technol. Online Learn. 1, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.31681/jetol.457046 (2018).

Xie, W. et al. Rational design of a Low-Data regime of pyrrole antioxidants for radical scavenging activities using quantum chemical descriptors and QSAR with the GA-MLR and ANN concepts. Molecules. 28 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28041596 (2023).

Yu, X. & Zeng, Q. Random forest algorithm-based classification model of pesticide aquatic toxicity to fishes. Aquat. Toxicol. 251, 106265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2022.106265 (2022).

Oztan Akturk, S., Tugcu, G. & Sipahi, H. Development of a QSAR model to predict comedogenic potential of some cosmetic ingredients. Comput. Toxicol. 21 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comtox.2021.100207 (2022).

Breiman, L., Random & Forests Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Trinh, T. X., Seo, M., Yoon, T. H. & Kim, J. Developing random forest based QSAR models for predicting the mixture toxicity of TiO2 based nano-mixtures to daphnia magna. NanoImpact 25, 100383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.impact.2022.100383 (2022).

Kurniawan, I., Rosalinda, M. & Ikhsan, N. Implementation of ensemble methods on QSAR study of NS3 inhibitor activity as anti-dengue agent. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 31, 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062936X.2020.1773534 (2020).

Drucker, H., Burges, C. J., Kaufman, L., Smola, A. & Vapnik, V. Support vector regression machines. Advances in neural information processing systems 9 (1996).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 Association for Computing Machinery, (San Francisco, California, USA, 2016).

Schapire, R. E. The strength of weak learnability. Mach. Learn. 5, 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00116037 (1990).

Wu, Z. et al. Do we need different machine learning algorithms for QSAR modeling? A comprehensive assessment of 16 machine learning algorithms on 14 QSAR data sets. Brief. Bioinform. 22 https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa321 (2021).

Phookphan, P. et al. A new Renieramycin T Right-Half analog as a small molecule degrader of STAT3. Mar. Drugs. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/md22080370 (2024).

Hatmal, M. M., Abuyaman, O. & Taha, M. Docking-generated multiple ligand poses for bootstrapping bioactivity classifying machine learning: repurposing covalent inhibitors for COVID-19-related TMPRSS2 as case study. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 4790–4824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.08.023 (2021).

Cramer, I. I. I., Bunce, R. D., Patterson, J. D., Frank, I. E., Crossvalidation & D. E. & Bootstrapping, and partial least squares compared with multiple regression in conventional QSAR studies. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 7, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/qsar.19880070105 (1988).

Dutschmann, T. M., Schlenker, V. & Baumann, K. Chemoinformatic regression methods and their applicability domain. Mol. Inf. 43, e202400018. https://doi.org/10.1002/minf.202400018 (2024).

Kar, S., Roy, K. & Leszczynski, J. in Computational Toxicology: Methods and Protocols (ed Orazio Nicolotti) 141–169 (Springer New York, 2018).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (eds I et al.) 4765–4774 (Curran Associates Inc., Guyon, 2017).

Avendaño, C. & Menéndez, J. C. In Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs 291–323 (2023).

Wang, J., Xie, X. Q., Hou, T. & Xu, X. Fast approaches for molecular polarizability calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 111, 4443–4448. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp068423w (2007).

Clavaguéra, C. & Dognon, J. P. Accurate static electric dipole polarizability calculations of + 3 charged lanthanide ions. Chem. Phys. 311, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2004.10.014 (2005). https://doi.org/.

Wang, K. et al. Static dipole polarizabilities of atoms and ions from Z = 1 to 20 calculated within a single theoretical scheme. Eur. Phys. J. D. 75, 46. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/s10053-021-00054-2 (2021).

Gritsenko, O. V. Koopmans’ theorem and its density-functional-theory analog assessed in evaluation of the red shift of vertical ionization potential upon complexation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 691, 178–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2017.11.019 (2018).

Tandon, H., Ranjan, P., Chakraborty, T. & Suhag, V. Polarizability: a promising descriptor to study chemical–biological interactions. Mol. Diversity. 25, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11030-020-10062-w (2021).

Hansch, C. et al. On the role of polarizability in Chemical – Biological interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 43, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci020378b (2003).

Cerofolini, G. F., Marrone, A. & Re, N. Correlating proton affinity and HOMO energy of neutral and negatively charged bases. J. Mol. Struct. (Thoechem). 588, 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-1280(02)00138-0 (2002).

Liao, X. W. et al. Total synthesis of (–)-renieramycin G from l-tyrosine. Tetrahedron 65, 5709–5715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2009.05.025 (2009).

Ivkovic, J., Lembacher-Fadum, C. & Breinbauer, R. A rapid and efficient one-pot method for the reduction of N-protected alpha-amino acids to chiral alpha-amino aldehydes using CDI/DIBAL-H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 10456–10460. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ob01838b (2015).

Funding

This research has received funding support from the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [grant number B38G680006]. I.D.P wants to thank the Graduate Scholarship Program for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN countries, Chulalongkorn University for providing financial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.D.P. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, validation, writing – original draft, as well as writing – review and editing. P.M. and T.R. contributed to conceptualization, supervision, validation, project administration, funding acquisition, as well as writing – review and editing. M.Y. and D.H. contributed to investigation, resources (chemicals), and validation. Z.Z.E. contributed to investigation and validation. L.Y. contributed to validation and supervision. P.C. contributed to conceptualization, supervision, resources, validation, as well as writing – review and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Putra, I.D., Maitarad, P., Yokoya, M. et al. QSAR machine learning-guided discovery of renieramycin right-half derivatives with cytotoxic activity against NSCLC cells. Sci Rep 15, 43516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26668-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26668-9

), test set (

), test set ( ), and validation set (

), and validation set ( )).

)).