Abstract

The multi criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach was used to optimise Abrasive waterjet (AWJ) pocket milling process parameters to examine the machinability of Ti-6Al-4 V alloy and the experiments were done by the L32 Taguchi array. Abrasive mesh (AM), waterjet pressure (WP), and traverse speed (TS) were chosen for this study, and material removal rate (MRR), depth of cut (DC), undercut (UC), and surface roughness (SR) were studied. Furthermore, the multiparametric ANOVA was used to determine the statistical significance of milling parameters, and the spatial pattern of output response parameter values was statistically assessed to support process parameter selection. Finally, regression models were developed based on milling parameters and output. To estimate the optimum level of input parameters for multi-objective optimization criteria on milling, particle swarm optimization (PSO), moth-flame optimization (MFO), grey wolf optimization (GWO), and whale optimization algorithm (WOA) have been combined with the combinative distance-based assessment (CODAS) methodology and multi-objective optimization on the basis of ratio analysis (MOORA). Weights for output were assigned using the objective-based entropy weight-age approach. The entropy weights for DC, UC, SR, and MRR were 0.3255, 0.2312, 0.1837, and 0.2596, respectively. The MOORA method predicts the best ideal parameters and based on the assessment scores MFO algorithm outperformed the others in maximising DC and MRR while reducing UC and SRR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In conventional machining, pocket milling, which involves removing material arbitrarily, is one of the most difficult forms of machining. This is due to the fact that tool failure is the most typical constraint, which drives up component prices due to the fact that the tool that broke must be replaced. Researchers have resorted to using the AWJ milling process, which is able to do rough stage milling, in order to circumvent this obstacle. It has been demonstrated that AWJ is capable of providing a high-quality machine tool for the processing of materials that are free of chipping, component faults, and thermal stress1. High-velocity abrasive waterjets cause material loss in both cutting and deformation wear modes2. The WP, AM, TS, AFS, and SoD parameters are the ones that are utilised in AWJ operations rather frequently3. In addition, the variables that are employed in milling processes, such as WP, TS, and AM, still have a limited amount of flexibility, which means that the values of these components cannot be increased or decreased. These are the most important characteristics that, when combined, contribute to the higher energy generation that the jet achieves when processing materials.

Researchers have employed AWJ to mill pockets4,5 by adjusting input parameters such as WP, TS, and AM. Additionally, several types of abrasives have also been used; however, only few of these studies have showed optimization in the AWJ pocket milling process6. It is of the utmost importance to ascertain the appropriate values for the process parameters in order to achieve an improvement in the efficiency of the processing. When the parameter settings are optimised, high-quality machining may be accomplished. Numerous evolutionary algorithms, such as the adaptive wavelet network7, cuckoo8, PSO9, MFO10, and others have been used by researchers in their works in an effort to determine the parameters that should be considered ideal or optimal. It was discovered that the evolutionary algorithms were successful in parametric study when the AWJ procedures were being carried out11. Previous AWJ milling studies provided valuable insights into the influence of waterjet pressure, abrasive type and traverse speed on performance metrics such as depth of cut and material removal rate; however, most of these works reported only single‑objective optimization and lacked comprehensive comparisons of multiple metaheuristic algorithms. Moreover, many prior experiments did not fully describe their methodologies or report measurement uncertainties, limiting reproducibility.

In spite of the fact that AWJ machining is applied often, the potential of milling processes is not being fully utilised. In addition, in-depth study on the AWJ milled pockets has not yet been carried out. As a consequence of this, the purpose of this investigation is to investigate the effect of process parameters on the performance of AWJ pocket milling by making use of soft computing strategies such as the PSO, MFO, GWO, and WOA algorithms. In addition to this, the effectiveness of the algorithms is evaluated by employing the CODAS and MOORA multi-criteria decision analysis approaches. Although AWJ milling has been studied, optimization combining multi‑criteria decision analysis with evolutionary algorithms for Ti‑6Al‑4 V pocket milling has not been systematically explored. The ranges of WP (200–400 MPa), AM (80–150 mesh) and TS (2500–4000 mm/min) used in this work were selected based on the capabilities of the AWJ machine, supplier recommendations for garnet abrasives and preliminary trials on Ti‑6Al‑4 V, ensuring that the selected levels cover practical operating conditions.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

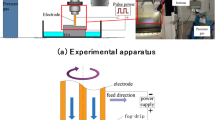

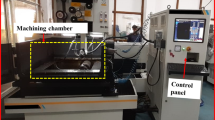

The work material for pocket milling operations in this investigation was Ti-6Al-4 V titanium alloy. The target material has dimensions of 150 × 150 × 8 mm. Milling trials were conducted on an AWJ machine tool (model G3020) with a capacity of 400 MPa (60 HP pump). The experimental setup for milling operations is shown in Fig. 1. In the target material, a 20 × 20 mm square pocket was milled. Table 1 displays the AWJ milling parameters and their levels. AM, TS, and WP were the variable parameters in this work, and the abrasive used was garnet with a flow rate of 350 g/min. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the institutional and laboratory safety standards for high-pressure abrasive waterjet machining systems, including the use of appropriate personal protective equipment, adherence to operational pressure limits, and implementation of emergency and waste disposal protocols.

The raster path that was programmed on the water jet machine tool was used to create the blind pockets. The raster path depicted in Fig. 2(a) was interpreted as a straight cut route down which the jet travels. After completing each pass, the jet rotated through an angle of ninety degrees before continuing linearly in accordance with the pre-specified step across a distance of 0.2 mm. After that, it completed yet another round of ninety degrees and moved on to the subsequent straight cut. This process was done several times until the necessary area had been milled. The AWJ milled samples of the Ti-6Al-4 V alloy are displayed in Fig. 2(b). Milling trials were carried out in accordance with the L32 model by design of experiments with regard to the variable parameters that were specified. The characteristics of the pocket that were examined were the DC, UC, SR, and MRR. The Taguchi L32 orthogonal array was chosen because it efficiently explores three factors at four levels with a reduced number of experiments, providing balanced coverage of the design space and enabling robust estimates of factor effects.

Measurement of output responses

To measure DC and UC, a digital microscope with a magnification up to 220x was utilised. Furthermore, the Digital Microscope is used to measure the UC that occurred at the square pocket’s edges. UC is an unfavourable characteristic that frequently appears in AWJ machined pockets. Each experimental trial was replicated three times to account for variability, and average values are reported. The measurement uncertainties for DC, UC and SR were ± 5 μm, ± 10 μm and ± 0.1 μm respectively, based on the instrument accuracies provided by the manufacturers.

The MRR was calculated by ratio of volume difference to milling time using Eq. 1. A weighing scale was used to determine the weight (Make: Eagle, Model: PKT-10 C).

Surface roughness was assessed using a contact roughness tester (Surfcom 1400G) with a 0.8 mm cut off length and 3.2 mm traverse length.

MCDM methods

CODAS

CODAS (combinative distance-based assessment) is a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM)12 method that ranks alternatives based on beneficial and non-beneficial criteria using ideal and anti-ideal solutions13. The methodology for CODAS is:

Developing the initial decision matrix

Normalize decision matrix

Weighted normalized decision matrix

Determine the negative ideal solution points

Calculate the Euclidean and Taxicab distances of alternatives from the negative ideal solution

Construct the relative assessment matrix

Calculate the assessment score and rank the alternatives

MOORA

MOORA (Multi-Objective Optimization on the basis of Ratio Analysis) is a popular MCDM method14,15. The methodology for MOORA is:

Initial decision matrix

Normalize decision matrix

Estimation of Assessment values

Metaheuristic methods

Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

PSO is a swarm intelligence-based optimization algorithm inspired by the social behavior of birds flocking and fish schooling16. Each particle adjusts its position using both its own experience and the swarm’s best solution17,18.

Moth-flame optimization (MFO)

MFO is inspired by the navigation behavior of moths around flames, where candidate solutions (moths) update their positions relative to flames to balance exploration and exploitation19,20.

Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO)

GWO mimics the leadership hierarchy and hunting strategy of grey wolves, using alpha, beta, and delta wolves to guide the search while other wolves update positions accordingly21,22.

Whale optimization algorithm (WOA)

WOA simulates the bubble-net hunting behavior of humpback whales, where solutions encircle prey and update their positions using shrinking encircling and spiral movements23,24.

The various parameters used in the metaheuristics are reported in Table 2. In this study both CODAS and MOORA were applied as multi‑criteria decision analysis methods to provide cross‑validation and enhance confidence in the ranking of alternative parameter combinations. Algorithm control parameters such as population size, inertia weights and learning coefficients were selected based on standard values reported in the literature to ensure fair comparisons across PSO, MFO, GWO and WOA. In addition to numerical metrics, statistical tests (ANOVA) were performed on the IGD and SP metrics and confirmed that the observed differences among algorithms were significant at the 95% confidence level.

Results and discussion

To conduct pocket milling experiments on the target Titanium (Ti-6Al-4 V) alloy, multiple combinations of process control settings based on the L32 orthogonal array were configured on the AWJ machine. Furthermore, as described in Sect. 2.2, the DC, UC, SR, and MRR were recorded. Table 3 displays the experimental observations and output responses.

The ANOVA was performed on the DC, UC, SR, and MRR responses using Minitab software and the results are shown in Table 4. The P-value from ANOVA results of the linear, square and 2-way interaction models for DC and SR was less than 0.05. As a result, all of the input factors used in this study were statistically significant. And the P-values for the linear and square models were less than 0.05 for UC and MRR, whereas the P-value for the 2-way interaction model for UC was greater than 0.05, indicating that the parameters have no effect on the algorithm’s performance. Specifically, waterjet pressure (WP) is the dominant factor for DC, SR and MRR because it sets the jet kinetic energy; travelling speed (TS) controls exposure time and therefore strongly affects DC, SR and MRR (with non-linear effects captured by TS²); abrasive mesh (AM) shows notable influence for DC and UC (edge-cutting behaviour) but limited effect on SR and MRR within the tested mesh range. Significant quadratic terms (WP², TS²) and the TS×WP interaction (for DC and SR) reflect non-linear and coupled effects of pressure and speed.

Pareto charts for investigating the influence of milling variables on DC, UC, SR, and MRR are shown in Fig. 3a-d. Figure 3a, c and d show that the input parameters, specifically WP and TS, had the greatest influence on the DC, SR, and MRR values. In addition, for UC value, WP and TS were the most influential, while AM was the least influential. Figure 4a-d shows response parameter spatial distribution. Figure 4 shows experimental and predicted milling response residuals. This residual plot was created using the Taguchi L32 orthogonal array and AWJ pocket milling experimental data such as DC, UC, SR, and MRR. Using residual plots, the difference between experimental and predicted residuals was examined.

The normal probability graphs illustrate that each milling performance’s residues established a structural pattern (Fig. 4). The residual vs. fitted values plot demonstrates that the residues were randomly distributed demonstrating a correlation that is not linear and containing no variances in the data. Residue plot histograms showed varying residue frequencies for each AWJ milling operation. In each experiment, residual vs. data order plots confirm residue distribution. Each experiment’s residue is determined by a unique arrangement of process parameters and their interactions under milling conditions. The findings demonstrate that the model that was suggested for the AWJ residue analysis applies to milling performance variables. According to these statistics, the input parameters were adjusted correctly to minimise UC and SR while improving DC and MRR.

Furthermore, using Minitab quadratic type MLRMs for DC, UC, SR, and MRR were created based on the relationship between the AWJ pocket milling process parameters and the output response characteristics. The MLRM for DC, UC, SR, and MRR are as follows:

Based on the statistical research discussed above, the process of developing the MLRM for the response, only the relevant factors and their interactions were taken into consideration individually. The process of comparing the calculated values to the experimental results is shown in Fig. 5. The developed quadratic regression models for DC, UC, SR and MRR exhibited high coefficients of determination (R² values exceeding 0.95 for all responses), demonstrating strong predictive capability which are presented in Table 5.

PSO, MFO, GWO, and WOA algorithms have been combined with CODAS, a multi-criteria decision analysis tool in this work. The CODAS technique seeks to undertake a multi-criteria selection process based on the highest Euclidean and Taxicab distance in relation to negative ideal solutions. This approach compares the MOORA method to determine the best process parameter for AWJ pocket milling.

Figures 6 and 7 depicts a distribution plot of the MCDA approach for the aforementioned algorithm, and it reveals that the spatial distribution of calculation time is normally distributed for both CODAS and MOORA. As a result, the major parameters for the multi criterion decision analysis procedures are properly calibrated in order to achieve a reduction in the amount of time spent on calculations during the AWJ pocket milling procedure. According to these findings, the calibrated major parameters were used for the execution of the CODAS and MOORA procedures in order to create improved pocket characteristics in the AWJ milling process.

Table 6 shows the optimum parameter and its response achieved by performing the aforementioned MCDA method for 30 runs with 100 iterations per run and a population size of 30. The results reveal that the MFO algorithm in the MOORA technique outperformed the other algorithms and the CODAS technique. Furthermore, as indicated by Khalilpourazari et al.25, the algorithm’s performance is tested using SP and IGD metrics. Table 7 shows the statistical value (SP &IGD) of the algorithms.

According to Table 7, the value of SP and IGD in MFO is lower than in other. As an outcome, based on the measures utilised, it is understandable that the MFO algorithm excelled other algorithms for the present work. Furthermore, the convergence graphs for the DC, UC, SR, MRR in Fig. 8 demonstrated MFO’s effectiveness. In this work, the convergence of all optimization algorithms (MFO, PSO, WOA, and GWO) was determined based on a fixed iteration count, which was kept identical across all algorithms to ensure a fair comparison. As an outcome of this, it is possible to draw the conclusion that the MFO performed better than the PSO, GWO, and WOA. Moreover, the superior performance of the Moth Flame Optimization (MFO) algorithm in this study can be attributed to its inherent ability to balance exploration and exploitation effectively. MFO simulates the transverse orientation navigation of moths, where candidate solutions (moths) move around flames in a logarithmic spiral path. This dynamic search mechanism enables MFO to explore the global search space efficiently while simultaneously refining promising regions locally, thereby avoiding premature convergence to local optima. In comparison, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) tends to converge rapidly but may be trapped in local minima, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) emphasizes exploitation over exploration and may struggle in multimodal landscapes, and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) provides a balanced search but often converges slower in highly nonlinear problem spaces. In our experiments on abrasive water jet milling, MFO consistently achieved superior outcomes across all responses—material removal rate, depth of cut, undercut, and surface roughness—demonstrating that its spiral navigation and exploration–exploitation trade-off are particularly effective for the complex, constrained optimization problem considered in this work.

DC at different AWJ milling parameters

According to the results of the statistical study, the milling parameters that were studied have a considerable impact on the DC of the milled titanium alloy. Because of this, it is extremely important to explore the interaction effects of these factors in AWJ pocket milling operation. Response surface plots are used to demonstrate the effects that the AWJ milling settings have on the DC (Fig. 9). Figure 9(a) shows a response surface plot, which illustrates how the AM and TS have an effect on the DC. Figure 9 clearly demonstrates that there has been a moderate increase in depth from the AM #80 mesh size to the #100 mesh size. This took place because the coarse #80 abrasives collided in the nozzle walls, reducing the energy. Because of the much longer span of time that the jet is exposed to the target material, a greater depth was discovered when the TS was set to a lesser value (2500 mm/min). It is clear from looking at Figs. 9(b) and 9(c) that the depth of the milling pocket gets deeper as the WP value is higher. At high water jet pressures, this phenomenon was seen where there was a large distribution of energy throughout the surface of the target, which created high depth. The WP of 200 MPa produced the greatest amount of depth.

UC at different AWJ milling parameters

The DC, MRR, and quality of the milled pockets are the primary objectives of the researchers. On the other hand, a few defects were found in pockets milled as UC in the exterior of the pockets. When the raster path enters a corner, the jet may be at zero, resulting in a larger kerf and greater depth milling. Minimal step over distance or dynamic machine settings may induce nozzle speed changes26. These flaws were seen in a variety of tool path techniques, including rectangular4,5 and triangular27 pockets with a change of orientation at 90 degrees. And, only a few research reported that the development of UC occurred in pockets milled using the single slot approach28. Because it has such a big impact on average DC, MRR, and surface quality, UC in the milling pockets is the primary factor that affects the overall quality of the components. As a result, it is essential to bring the UC in pocket milling down to an acceptable level. According to the findings of the statistical studies, the AWJ milling settings that were chosen for the experiment had a profound effect on the creation of the UC. Figure 10 illustrates the effects that the AWJ milling settings have on the DC. The impact that AM and TS have had on DC is seen in Fig. 10(a). It can be noticed that the DC is greater at the 100 mesh size at low TS (2500 mm/min). This is due to #100 abrasives experienced less particle collision which kept the energy of the abrasives in the jet stable29. As a direct consequence of this, a significant quantity of material was removed from the border region, so producing an UC in that area. However, because the speed of the nozzle slows down when turning a 90-degree angle, this location is also more likely to strike more abrasives than other regions. In addition, the rise in WP and the fall in TS levels both led to a quicker material removal, which resulted in a bigger UC to the titanium alloy, as seen in Fig. 10(c). WP drop and raising the TS to 3500 mm/min decreased the UC depth, after passing this threshold, the UC reached its full potential at 4000 mm/min and 200 MPa WP. Compared to TS values of 3000 and 3500 mm/min, 4000 mm/min decelerated rapidly towards the lowest speed; nonetheless, it was somewhat quicker than the 2500 mm/min nozzle speed and brought in more abrasives in action, which increased UC.

SR at different AWJ milling parameters

SR is one of the most important quality qualities that should be present in any machined endues components. As a result, the evaluation of the roughness of the milled pockets served as the basis for determining the smooth surface. According to the findings of the statistical studies, the milling parameters that were chosen for the experiment had a huge influence on SR. Figure 11 shows how AWJ pocket milling parameters affect SR. Rough surfaces were discovered, which were the result of significant erosion with increased energy and removal of material in an uneven manner at a WP of 200 MPa (Fig. 11b and c). When the water pressure was raised, the jet stream’s impact energy increased, causing uneven material removal and corrugated surfaces. The water jet’s threshold energy prevented lateral erosion across the target material. This permitted homogeneous flat surfaces at 125 MPa WP, regardless of traverse rate. Greater WP has rough, grooved surfaces. Reduced TS allowed more abrasives to strike sample, resulting in a rough surface (Fig. 11a).

MRR at different AWJ milling parameters

The MRR has a considerable impact on both the total cost of processing and the rate of output that may be achieved during machining. Because of this, businesses are continuously seeking for methods to enhance their MRR in order to satisfy customers’ needs while keeping their production costs as low as possible. According to the findings of the statistical study, the MRR of titanium alloy is considerably impacted by the process factors that were taken into consideration because the MRR process is dependent on a number of parameters. Response surface plots provide a visual representation of the effects that the AWJ pocket milling settings have on MRR (Fig. 12a–c). It can be observed from the charts that there was a correlation between the increase in WP and the rise in MRR for both of the AM sizes. However, due to the fact that energy was transferred to abrasives from the water jet in the mixing chamber, the MRR was increased by the abrasive mesh size #80 despite the fact that the pressure of the water jet was changed to a lower level. In addition to this, there was a decrease in the TS, which resulted in an increase in the number of abrasives that impinged against the material that was being targeted. Because of the occurrence of these results, the MRR increases because a greater number of abrasives struck the material and removed it. This is because the MRR accounts for the number of abrasives that affected the material. The results reinforce established findings that WP and TS significantly influence key milling outputs such as DC, SR, and MRR, consistent with previous investigations on Ti-6Al-4 V and other alloys. Unlike earlier single-objective studies, our multi-criteria optimization approach integrating advanced evolutionary algorithms combined with CODAS and MOORA multi-criteria decision analysis offers a more holistic and effective parameter selection technique. This integrated approach outperformed conventional studies by balancing multiple performance metrics simultaneously and by efficiently identifying parameter sets that maximize machining quality and productivity.

Microstructure analysis of machined surface

The microscopic appearance of milled surfaces is seen in Fig. 13. When comparing mesh size #80 (a&b) milled surfaces to mesh size #100 (c&d) it appears that a greater number of ploughing and deep ploughing were seen. And it was found that surfaces with a mesh size of #100 were the smoothest, with less ridges and wear tracks. It has been established that the shearing action of abrasive mesh size #100 was responsible for the damage, rather than the ploughing impact. While travelling through the mixing tube, the jet’s kinetic energy was gradually decreasing as a result of the intense particle collisions caused by the coarse (#80) abrasives. Because of this, the surface was ploughed as a result of a single abrasive grain being struck with a lesser amount of kinetic energy. Continuous jet action has pushed material to the side of channels, forming ridges. Because of fewer particle collisions and retained cutting energy, #100 milled surfaces have bigger particles than other surfaces. We also found deep gaps due to #100 mesh’s enhanced material removal. In the end, the material from the surface of the target was removed using a mix of operations involving cutting and deformation erosion. To complement the qualitative SEM observations, ridge heights and groove depths were measured directly from the micrographs: average ridge height was approximately 15 μm and average groove depth was about 25 μm. Each SEM image now includes a scale bar to facilitate interpretation.

Conclusion

In this study, AWJ pocket milling on Ti-6Al-4 V alloy was performed by adjusting the abrasive AM, WP and TS. ANOVA was used to statistically assess the experimental outcomes. To establish the relationship with milling parameters, minitab software was used to create quadratic regression equations for DC, UC, SR, and MRR. Using PSO, MFO, GWO, and WOA algorithms, the optimal combination of milling parameters was projected to maximise DC and MRR while minimising UC and SR. And the performance of the algorithms was compared using the MCDM approach, with the major results shown below.

-

1.

The Analysis shows that WP and TS are important in pocket milling. During milling the jet’s energy depends on the WP and the increase in energy increase the milling depth and as well as material removal rate.

-

2.

Taking into consideration the properties of the pocket was determined that WP was the most influential parameter, followed by TS and AM.

-

3.

SEM micrographs show that the surface of the AWJ milled material had ridges and grooves when it was milled with a high WP.

-

4.

The multi-criteria decision analysis methods such as CODAS and MOORA was introduced to find the effectiveness of the PSO, MFO, GWO and WOA based on the computational time.

-

5.

The minimal values of the performance measurement tool, such as SP and IGD, were compared with the different algorithms and the findings showed that the MFO algorithm obtained less SP and IGD.

-

6.

The optimum combination of milling parameters is obtained from MOORA MCDA method.

-

7.

The MFO algorithm came up with the following values for DC, UC, SR, and MRR: 2.4074 mm, 2.78 mm, 7.6769 μm, and 4.5401 mm/min when the input variables were 80.3210 AM, 2515.9316 mm/min TS, and 200 MPa WP.

-

8.

The optimized parameters identified in this study have practical significance: by maximizing depth of cut and material removal while minimizing undercut and surface roughness, AWJ pocket milling of Ti‑6Al‑4 V can achieve improved surface integrity, reduced machining time and lower abrasive consumption. These improvements translate into cost savings and enhanced component quality, which are particularly valuable for aerospace and biomedical applications. Future work could extend this methodology to other alloys, investigate the effect of different abrasive types and explore hybrid optimization frameworks combining MCDA with advanced metaheuristics.

The optimized parameters obtained in this study are directly applicable to pocket milling operations in aerospace and automotive component manufacturing. In aerospace, they can be used for machining turbine blade slots, cooling channels, and internal cavities of structural components, while in automotive, they are suitable for engine block cavities, transmission housings, and lightweight structural parts. Implementing these optimized settings can result in higher material removal rates, improved surface finish, reduced tool wear, and precise dimensional control, providing measurable improvements in component quality and production efficiency. We acknowledge that the present study considered only two abrasive mesh sizes and a limited pressure range, which may restrict the generalizability of the results. Future research could explore a wider variety of abrasive types and mesh sizes, expanded pressure ranges, and other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDA) frameworks, such as TOPSIS, DENGS. VIKOR, AHP, and PROMETHEE, to further enhance optimization and industrial applicability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Momber, W. & Kovacevic, R. Principles of Abrasive Water Jet Machining, 1998 ed. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-1572-4 (Springer, 2012).

Patel, D. & Tandon, P. Experimental investigations of thermally enhanced abrasive water jet machining of hard-to-machine metals. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 10, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2015.04.002 (2015).

Natarajan, Y., Murugesan, P. K., Mohan, M. & Liyakath Ali Khan, S. A. Abrasive water jet machining process: A state of art of review. J. Manuf. Process. 49, 271–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2019.11.030 (2020).

Kanthababu, M., Ram, R., Emannuel, N., Gokul, R. & Rammohan, R. Experimental investigations on pocket milling of titanium alloy using abrasive water jet machining. FME Trans. 44, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.5937/fmet1602133K (2016).

Pal, V. K. & Tandon, P. Identification of the role of machinability and milling depth on machining time in controlled depth milling using abrasive water jet. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 66, 877–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-012-4373-z (2013).

Perec, A. et al. Comparison of chosen metaheuristic algorithms for the optimization of the abrasive water jet treatment process. MM Sci. J. https://doi.org/10.17973/MMSJ.2024_11_2024098 (2024).

Ergur, H. S. & Oysal, Y. Estimation of cutting speed in abrasive water jet using an adaptive wavelet neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 26, 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-013-0798-y (2015).

Kalita, K., Ghadai, R. K., Cepova, L., Shivakoti, I. & Bhoi, A. K. Memetic cuckoo-search-based optimization in machining galvanized iron. Materials. 13, 3047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13143047 (2020).

Lmalghan, R., Rao, K., ArunKumar, M. C., Rao, S. S. & Herbert, M. A. Machining parameters optimization of AA6061 using response surface methodology and particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 19, 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-018-0083-2 (2018).

Mirjalili, S. Moth-flame optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired heuristic paradigm. Knowl. Based Syst. 89, 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2015.07.006 (2015).

Rajendran, S., Ranganathan, B. & Karuppasamy, K. Predictive modeling and optimization of abrasive waterjet drilling (AWJD) parameters on AZ31B-Mg alloy using neural networks and grey relational analysis. Rev. Metal. 60, e261–e261. https://doi.org/10.3989/revmetalm.e261.1616 (2024).

Raja, P., Sakthivel, M., Kumar, T. S., Petrů, J. & Kalita, K. Deep cryo treated tungsten carbide tools on AISI 1045 steel turning through grey relational analysis and preference selection index. Sci. Rep. 15, 18452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02263-w (2025).

Maheshwari, N., Choudhary, J., Rath, A., Shinde, D. & Kalita, K. Finite element analysis and multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM)-based optimal design parameter selection of solid ventilated brake disc. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. C 102, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40032-020-00650-y (2021).

Chakraborty, S., Datta, H. N., Kalita, K. & Chakraborty, S. A narrative review of multi-objective optimization on the basis of ratio analysis (MOORA) method in decision making. Opsearch 60, 1844–1887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12597-023-00676-7 (2023).

Kumar Ghadai, R., Chakraborty, S. & Kalita, K. On solving parametric optimization problem of an end milling process for machining of Al 1070 using MCDM techniques: A comparative analysis. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/2374068X.2023.2216398 (2023).

Kalita, K., Cepova, L. & Jangir, P. Gaussian transfer functions based binary particle swarm optimization for enhanced performance in un-capacitated facility location problem. MM Sci. J. https://doi.org/10.17973/MMSJ.2024_12_2024125 (2024).

Ma, C. et al. High-efficiency topology optimization method for thermal-fluid problems in cooling jacket of high-speed motorized spindle. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 169, 109533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2025.109533 (2025).

Sha, X., Si, X., Zhu, Y., Wang, S. & Zhao, Y. Automatic three-dimensional reconstruction of transparent objects with multiple optimization strategies under limited constraints. Image Vis. Comput. 160, 105580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105580 (2025).

Tian, A. et al. Resistance reduction method for building transmission and distribution systems based on an improved random forest model: A tee case study. Build. Environ. 282, 113256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2025.113256 (2025).

Liu, R. & Shen, W. Data acquisition of exercise and fitness pressure measurement based on artificial intelligence technology. SLAS Technol. 33, 100328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slast.2025.100328 (2025).

Kalita, K., Pal, S., Haldar, S. & Chakraborty, S. A hybrid TOPSIS-PR-GWO approach for multi-objective process parameter optimization. Proc. Integr. Optim. Sustain. 6, 1011–1026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41660-022-00256-0 (2022).

Mudafale, K., Kalita, K., Cep, R., Blata, J. & Samal, S. P. A hybrid GP-GWO framework for enhanced performance of rotary drying systems. MM Sci. J. https://doi.org/10.17973/MMSJ.2025_03_2025004 (2025).

Kalita, K. et al. Many-Objective Whale Optimization Algorithm for engineering design and large-scale many-objective optimization problems. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-024-00562-0 (2024).

Shanmugasundar, G., Pal, S., Chohan, J. S. & Kalita, K. Pareto optimization of laminated composite plates with non-dominated sorting whale optimization algorithm (NSWOA) ensemble. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 350–357 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50151-7_33 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

Khalilpourazari, S., Naderi, B. & Khalilpourazary, S. Multi-objective stochastic fractal search: a powerful algorithm for solving complex multi-objective optimization problems. Soft Comput. 24, 3037–3066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-019-04080-6 (2020).

Gupta, T. V. K., Ramkumar, J., Tandon, P. & Vyas, N. S. Role of process parameters on pocket milling with abrasive water jet machining technique. (2013).

Huang, J., Gao, L. & Li, X. An effective teaching-learning-based cuckoo search algorithm for parameter optimization problems in structure designing and machining processes. Appl. Soft Comput. 36, 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.07.031 (2015).

Escobar-Palafox, G. A., Gault, R. S. & Ridgway, K. Characterisation of abrasive water-jet process for pocket milling in inconel 718. Procedia CIRP 1, 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2012.04.072 (2012).

Cha, Y., Oh, T.-M., Hwang, H.-J. & Cho, G.-C. Simple approach for evaluation of abrasive mixing efficiency for abrasive waterjet rock cutting. Appl. Sci. 11, 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11041543 (2021).

Zhang, H. H., Yao, H. M. & Jiang, L. J. Novel time domain integral equation method hybridized with the macromodels of circuits. In 2015 IEEE 24th Electrical Performance of Electronic Packaging and Systems (EPEPS), San Jose, CA, USA https://doi.org/10.1109/EPEPS.2015.7347147 (2015).

Yu, Z., Ning, Z., Chang, W.-Y., Chang, S. J. & Yang, H. Optimal harvest decisions for the management of carbon sequestration forests under price uncertainty and risk preferences. For. Policy Econ. 151, 102957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.102957 (2023).

Xiang, X. et al. Enhancing beef tallow flavor through enzymatic hydrolysis: Unveiling key aroma precursors and volatile compounds using machine learning. Food Chem. 477, 143559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143559 (2025).

Wang, X., Su, H. & Liu, X. The impact of green technological innovation on industrial structural optimization under dual-carbon targets: The role of the moderating effect of carbon emission efficiency. Sustainability 17, 6313. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146313 (2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L. Naresh Raj, S. Jayavelu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation. M. Sivakumar, B Swarna: Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Resources, Formal analysis. Ajay Kumar: Writing—review and editing, Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation and Validation, Project Administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naresh Raj, K.L., Jayavelu, S., Kumar, M.S. et al. Multi-criteria decision analysis approach on parametric optimization of abrasive waterjet pocket milling in Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Sci Rep 15, 42719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26719-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26719-1