Abstract

Probiotics are live microorganisms, when consumed in certain numbers confer health benefits on the host beyond inherent basic nutrition. This study was conducted to characterize the probiotic properties of bacteria isolated from pickled Vietnamese cabbage. Identification by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis revealed that the isolate was Bacillus aryabhattai. The ability of B. aryabhattai HY1 to resist acidic condition, 0.3% (w/v) bile salts, sensitivity to Amoxicillin (25–40 µg) and Ampicillin (30–40 µg). In addition, the isolate was able to show inhibition towards pathogenic bacteria including Escherichia coli (EC), Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Salmonella typhimurium (ST), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). The combination of 2% glucose with B. aryabhattai HY1 increased the production of acetic acid and butyric acid. These findings help to explain the health advantage and antimicrobial properties of B. aryabhattai HY1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vietnam has produced a variety of traditional fermented foods for a very long time. These products include a variety of microorganisms with advantageous food processing technology, preservation properties, and organoleptic abilities, among other functional characteristics. The beneficial indigenous bacteria included in traditional fermented meals are abundant1. A well-liked fermented food is Vietnamese mustard greens pickles, sometimes referred to as vegetable fermented. During pickling, the glucosinolates of Brassica juncea are hydrolysed to the glucosinolate hydrolysis products modulating enzyme activity and preventing certain cancers2. High antioxidant capacities of phenolic compounds in mustard greens can inhibit oxidative damage diseases, such as stroke and cancers3,4. A microbial community involved in traditional Vietnamese fermented pickles including lactic acid bacteria and Bacillus strains such as B. subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. licheniformis, B. circulans, B, pumilus, and B. brevis5,6. Our previous study demonstrated that B. amyloliquefaciens EH-9 strain shows a positive effect on the GABA production, which can further improve COL1 production in the skin7. Bacillus spp. act as probiotics have exhibited probiotic capabilities with a variety of advantages mediated by several complex mechanisms.

Probiotics are defined as living microorganisms which upon ingestion in adequate amounts, exert beneficial physiological effects on their host8. The human gut microbiota, being represented principally by the two major phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes9. Less well known than the lactobacilli and bifidobacteria are certain species of the spore-forming probiotic Bacillus genus, which can be considered as probiotic applications10. The members of genus Bacillus are a Gram-positive, rod shaped, spore-forming, aerobic or facultative anaerobic bacterium11. Bacillus spp. inhabits the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) due to its highly resistant to agents such as heat, radiation, desiccation, digestive enzymes, and gastric acidity conditions, with 103–108 CFU g-1 Bacillus spp. spores from human feces12. Beneficial health action refers to probiotic ingestion including proven biological activity in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases and cancer prevention13. Mounting evidence suggests that among the probiotics, Bacillus spp. has been used for enzyme production in varying food stuffs as well as vitamins and carotenoids for human consumption11. Bacillus aryabhattai (B. aryabhattai) has recently attracted interest because of its probiotic potential and application in a variety of fermented foods, drinks, and dairy products14,15. It can lessen the prevalence of dangerous germs that lead to illnesses or diseases that can affect humans16,17,18. Probiotic products predominantly feature several Bacillus species such as B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and B. indicus19. However, the potential for B. aryabhattai to act as a probiotic has received limited research attention.

The gut microbiota significantly influences many physiological functions, including glucose metabolism, early dissociation and dihydroxylation of bile acid and biosynthesis of essential vitamins and amino acids20. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are major homofermentative products of gut microbiota from dietary fiber and have been recognized as important mediators in regulating immunomodulatory functions8,21. SCFAs such as butyric acid and acetic acid, have demonstrated the capacity to mitigate both metabolic dysfunctions and inflammation22. Various prebiotic fibers yield varying quantities and compositions of primary SCFAs, specifically acetic, propionic, and butyric acids23. Butyric acid is a vital energy source for the colonic epithelium and show growth inhibition and apoptosis on two human colorectal tumour cell lines, one adenoma (S/RG/C2) and one carcinoma (HT29) in vitro24. Acetic acid has been reported to show some health benefits, potentially contributing to antihypertensive, anti-hyperglycemic, and anti-tumor effects25. The purpose of this study is to isolate B. aryabhattai HY1 strain capable of producing butyric and acetic acids from pickled Brassica juncea and to evaluate its probiotic potential through assessments of acid and bile tolerance, antibiotic susceptibility, and antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria.

Materials and methods

Isolated bacteria and identification

The pickled mustard greens were homogenized in sterile distilled water using a grinder. The homogenate was serially diluted and plated on De Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS, Hi-Media, Mumbai, India) agar, then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Distinct colonies were picked and purified by streaking on fresh MRS agar. The sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes was used to identify the bacteria26. In addition to sequencing of Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products, 16S rRNA genes were amplified with 16S rRNA primers 27F and 534R (Fig.S1)27. The 16S rRNA gene sequences were analyzed using the basic local alignment search tool (BLASTn, National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Glucose fermentation of B. aryabhattai HY1

To induce fermentation, B. aryabhattai HY1 [107 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL] was incubated in rich media [10 g/L yeast extract (Himedia), 5 g/L TSB, 2.5 g/L K2HPO4 and 1.5 g/L KH2PO4], with or without 20 g/L (2%) glucose at 37 °C for 24h. Rich media only or rich media plus 20 g/L glucose without bacteria were served as a control. Phenol red [0.001% (w/v), Sigma] was served as a pH indicator. A color change from red–orange to yellow indicated acid production.

Acid tolerance

A good potential probiotic needs to be stable at a low pH and in the presence of high bile salts in the stomach and digestive tract28. Following the method of Lee et al., bacterial cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended to 107 CFU/mL in sterile PBS. Aliquots were inoculated into MRS broth adjusted to pH 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (using 1 M HCl)29. A control was only MRS broth. Then, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Surviving bacteria were counted by spread plating on MRS agar and incubating for 24 h at 37 °C. The relative survival of the bacteria was calculated with the formula below

Bile salt tolerance

Bile tolerance was performed using the method of Lee et al. An aliquot of overnight culture (107 CFU/mL) was inoculated to MRS broth containing 0.3, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0% bile salts. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. MRS without bile acids was used as the control. Surviving bacteria were counted by spread plating on MRS agar and incubating for 24 h at 37 °C. The relative survival of the bacteria was calculated with the formula below:

Antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria

Antibacterial activity was evaluated against Escherichia coli (EC), Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Salmonella typhimurium (ST), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) using method modified from Rokana, et al. (2017). The pathogens were obtained from the stock culture of Microbiology Laboratory, Ton Duc Thang University, Vietnam. Aliquots of the actively growing pathogenic strains (107 CFU/mL) were seeded in sterilized molten MRS agar, and dispensed into plates. Wells (5 mm diameter) were punched in the agar plates using a sterile borer. Cell-free supernatant of overnight HY1 cultures was filter-sterilized and 100 µL was dispensed into wells. The plates were pre-incubated at 7 °C to allow the supernatants diffuse into the agar following incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The inhibition zones was measured using a caliper.

Antibiotic susceptibility

To evaluate the antibiotic susceptibility of the B. aryabhattai HY1, the fresh culture of the bacteria was streaked densely on Mueller–Hinton agar by a sterile cotton swab. Ampicillin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, gentamicin, levofloxacin, penicillin, streptomycin (10–40 µg/disc) were loaded on the plates30. The zone diameters were measured after incubation at 37 °C for 48 h. Results were interpreted as resistant (R), intermediate (I) or sensitive (S) according to CLSI guidelines31.

Detection of short-chain fatty acid (SCFAs) by gas chromatography-flame ionization detector (GC-FID)

B. aryabhattai HY1 (107 CFU/mL) was cultured in MRS broth in the presence or absence of 2% glucose at 37 °C for 24 h. The culture supernatants were filtered through a 0.22 µm microfiltration membrane. Samples were added with the concentrated HCl (100 µL) and extracted with 5 ml diethyl ether for 20 min by gently rolling. After centrifugation (3,500 rpm, 5 min), the supernatant was transferred to a Pyrex extraction tube, neutralized with NaOH (500 µL, 1 mM). The aqueous phase was moved to an autosampler vial, and added the concentrated HCl (100 µL). The analysis of the SCFAs in culture media was conducted using an Agilent 7890A GC-FID equipped with an Agilent J&W GC Column DB-FFAP (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.5 µm). The Agilent OpenLab ChemStation (version B.04.03) was used for data collection. The injection temperature was 300 °C. Samples were injected in pulsed split injection mode in 1 µL aliquots. The initial oven temperature was 100 °C, with a hold time of 0 min. The oven temperature increased from 100 °C to 250 °C at 20 °C /min, with a final hold time of 0 min. Helium was the carrier gas, with a flow rate of 1.7682 mL/min. The total run time of the method was 10 min.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA) was utilized for data analysis by unpaired t-test. The statistical significance was considered as p-value < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), and < 0.001 (***). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments.

Results

Identification and phylogenetic analyses of the test bacteria

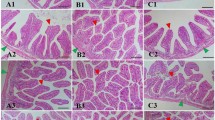

The colony of the bacteria isolated from Vietnam pickled mustard greens on MRS agar was 3 mm in diameter, yellowish-cream in color, pigment-free, with round to irregular shapes and whole to undulate edges (Fig. 1a). The strain are Gram-positive and short rod-shaped cells (Fig. 1b). The overlapping parts of the 16S sequences from our strain and strains of different Bacillus species in BLAST searches in GenBank were 99.93% identical. The sequence were deposited in GenBank under accession number PQ653493 (Fig. S2). The isolated bacteria were conspecific, but could not be unequivocally determined as B. aryabhattai with BLAST search in GenBank, but only by conducting a phylogenetic analysis (Fig. S2) with a representative own sequence (PQ653493) and carefully selected sequences of reliably identified species from taxonomic papers. Our strain nested in a clade composed exclusively of B. aryabhattai with strong support. Priestia (formerly known as Bacillus) is a new species of the family Bacillaceae of the order Bacillales. B. aryabhattai cells are characterized by their highly variable shape and size (2.5–4 µm long and 0.8–1 µm wide)32,33,34.

Glucose fermentation of B. aryabhattai HY1

To examine the fermentative capabilities of the isolate, B. aryabhattai HY1 was cultured in MRS medium with or without 2% glucose for 24 h. MRS media with glucose only or bacteria only served as controls. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, yellowish media and a decrease in OD562 (0.099 ± 0.001) were detected in the culture of B. aryabhattai HY1 in MRS medium without glucose. Medium exhibited a more yellowish colour and showed a considerable decline in OD562 value upon the addition of 2% glucose (0.094 ± 0.003) compared to controls. The data further confirmed that glucose can trigger and enhance the fermentation in B. aryabhattai HY1.

Glucose fermentation by B. aryabhattai HY1. (a) B. aryabhattai (B) was cultured in MRS media (M) with or without the addition of 2% glucose (Glu) for 24 h. MRS media added with 2% glucose alone were included as a control. Bacterial fermentation was indicated by the colour change of phenol red from red to yellow. (b) Media of culture with bacteria and/or glucose were measured by OD562. The reduction of OD562 was detected when fermentation happened. After 24 h, the OD562 value of B. aryabhattai (B) with glucose (Glu) was significantly reduced (0.094 ± 0.003, n = 3) compared to that (0.108 ± 0.001, n = 3) of MRS medium (M) and glucose (Glu). Data are the mean ± SD of experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05. ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed t -test).

Determination of acid tolerance

A probiotic strain possesses the ability to withstand unfavourable conditions of the human body such as low pH and bile salt; gastric candidate probiotic is potential in the prevention and treatment of gastric disorders and dysbiosis35. The resistance of the B. aryabhattai HY1 to acidic conditions was accessed at pH 2–6 for 3h. Viability was 16 ± 1% at pH 2 and 53 ± 3% at pH 3 (Fig. 3). Survival increased at higher pH values, indicating that the strain can recover from acid stress and resume growth.

Determination of bile tolerance

The viability of bacteria upon bile secretion at different incubation times simulating the physiological aspects of human digestive system36. In vitro experiments have been conducted to investigate high tolerance of B. aryabhattai HY1 to bile salts. Results are shown on Fig. 4, the strain maintained 93.30 ± 2.30% viability in 0.3% bile salt after 3 h. At higher concentrations such as 0.5% and 1% bile, survival rate (%) was reduced to 49.71 ± 1.72 and 24.31 ± 3.40, respectively. Even at 2% bile, viable counts remained at 0.27 × 10⁸ CFU/mL (Table S1 and Fig. S3).

Antibiotic resistance

Several Bacillus strains have been employed for centuries as biomass for animal feed, feed additives, manufacture of traditional fermented dishes in Asia, and plant production products37,38. From the perspective of antibiotic use, some probiotic strains with intrinsic antibiotic resistance could be useful for restoring lost gut microbial diversity after antibiotic treatment and provide colonization resistance against the proliferation of disease-causing organisms. Antibiotic sensitivity test showed that the B. aryabhattai HY1 was highly susceptible to 30–40 µg ampicillin (AMP) and 25–40 µg amoxicillin (AMC) (Table 1), showing large inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) (Fig. S4). The strain exhibited intermediate susceptibility to 20 µg amoxicillin (AMC) (Table S2), but resistant to tetracycline (TCY), gentamicin (GEN), levofloxacin (LVX), and penicillin (PEN).

Antibacterial activity

Bacillus strains from traditional fermented food, which have also been shown to possess characteristics such as anti-oxidant, antimicrobial, immunomodulation11. B. aryabhattai HY1 produced inhibition zones against E. coli (14.63 ± 0.32 mm), S. aureus (6.17 ± 0.58 mm), S. typhimurium (16.83 ± 0.35 mm), P. aeruginosa (11.47 ± 0.55 mm) (Fig. 5, Table S3).

SCFAs was produced by glucose fermentation of B. aryabhattai HY1

SCFA production during glucose fermentation was analyzed by GC-FID. B. aryabhattai HY1 produced acetic and butyric acids in MRS medium with or without added glucose (Fig S5). In the absence of glucose, cultures yielded 96.80 mg/L acetic acid and 57.91 mg/L butyric acid (Table 2). However, with 2% glucose supplementation, production increased to 354.71 mg/L acetic acid and 249.20 mg/L butyric acid, illustrating the prebiotic property of glucose for B. aryabhattai HY1. No SCFAs were detected in control media without bacteria. The acetic acid and butyric acid were detected in MRS medium with B. aryabhattai HY1 because the presence of dextrose in MRS which serves as a potential carbon source. This finding indicates that B. aryabhattai HY1 can ferment glucose to generate acetic acid and butyric acid.

Discussion

The isolated bacterium (GenBank accession number PQ653493) was identified as B. aryabhattai HY1 by BLAST search in GenBank and a phylogenetic analysis (Fig. S2). This species has been recognized as a potential probiotic bacterium exhibiting multiple beneficial effects. Previous studies have reported that B. aryabhattai demonstrates bacteriocin-producing activity against Vibrio harveyi, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium TISTR 2921514, as well as the ability to boosted innate immunity and antioxidant defences17, and reduce inflammatory responses in turbot juveniles39. However, no studies have investigated the probiotic attributes of B. aryabhattai isolated from pickled Brassica juncea.

The antagonistic effect of various Bacillus species against foodborne pathogens, attributed to the secretion of antimicrobial peptides, small extracellular effector molecules, and their ability to form biofilm, sporulate anaerobically, and adhere to host tissues40,41,42. A probiotic B. aryabhattai strain isolated from fish gut was also shown to inhibit Streptococcus mutans, a pathogen responsible for oral diseases43. Rajabi et al. demonstrated that B. aryabhattai effectively inhibited the growth of Listeria monocytogenes, the causative agent of listeriosis44. Collectively, these findings highlight B. aryabhattai as a promising probiotic candidate with broad antimicrobial potential and possible applications in food safety, aquaculture, and human health. Similar antibacterial effects were reported for Lactobacillus paracasei against E. coli and S. aureus, highlighting the relevance of these inhibitory patterns among probiotic candidates45. Nevertheless, the probiotic properties of B. aryabhattai isolated from fermented vegetables, particularly Vietnamese pickled mustard greens, remain largely unexplored.

The antibiotic susceptibility profile of Bacillus aryabhattai HY1 is consistent with previous findings reported for other B. aryabhattai strains. For instance, B. aryabhattai AB211 was resistant to tetracycline, rifamycin, troleandomycin, lincomycin, nalidixic acid, and aztreonam46. Similarly, strains isolated from rhizospheric soil displayed resistance to some tested antibiotics, including ampicillin (10 µg) and Penicillin (10 µg)47. B. aryabhattai LAD harbors 31 antibiotic resistance genes, suggesting a strong adaptive capability in antibiotic-rich environments48. In this study, B. aryabhattai HY1 exhibited susceptibility to amoxicillin (25–40 µg) and ampicillin (30–40 µg). In accordance with the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)/the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for probiotic safety assessment, particular attention should be given to the potential for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) among gut microbiota49,50. Although the antibiotic resistance observed in B. aryabhattai HY1 may reflect intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens, the possibility of mobile genetic elements mediating HGT cannot be excluded. Therefore, future work should include whole-genome sequencing and molecular screening to identify and characterize potential ARGs and their genetic context. Such analyses will provide a comprehensive safety evaluation and ensure compliance with international regulatory frameworks for probiotic application.

Probiotics administered orally must endure the harsh conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, including exposure to gastric acid and bile salts51. Acid and bile tolerance are therefore crucial determinants of probiotic viability and functionality within the host52. In this study, B. aryabhattai HY1 exhibited substantial viability at pH 2 and pH 3, indicating strong acid resistance. The gastric pH in humans fluctuates between 1.5 during fasting and 4–6 after food intake, which corresponds to the optimal activity range of gastric lipase and pepsin53. A minimum tolerance threshold of pH 3.0 is essential for probiotic survival54. The comparable growth observed at pH 5 and pH 6 in B. aryabhattai HY1 aligns with the known pH growth range (4.5–7.0) for Bacillus species55. The passage time for gastric digestion can be from 1 to 4 h depending on the individual and diet56. This could be by a networked cellular enzymes from acidophilic microorganisms are functional at much lower pH than the cytoplasmic pH57.

Bile tolerance is another essential criterion for probiotic efficacy. Consistent with previous findings that probiotic Bacillus species can withstand a wide range of bile concentrations58,59. This resilience may be attributed to bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity, an enzyme involved in bile detoxification60. Studies recently showed that BSH activity and bile salt resistance capability B. cereus ATCC 1457061 and B. mojavensis LY-0662. Collectively, these data indicate that B. aryabhattai HY1 fulfills a key prerequisite for probiotic functionality by surviving in acid- and bile-rich environments.

The persistence of B. aryabhattai in fermented Assam tea leaves, showed great probiotic potential conferring health benefits on the host when adequate amounts are administered63. Acetate-producing B. coagulans has been shown to restore intestinal barrier function via Ffar2 regulates the NF-κB–MLCK–MLC pathway to improve tight junctions in Apostichopus japonicus64. B. subtilis strains have been associated with increased butyrate production in broiler gut microbiome and improved intestinal histomorphology65. Also, the supplementation of B. subtilis on in vitro ruminal fermentation have shown its ability to shift volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles, including increases in butyrate under certain conditions66. It has been shown that B. clausii able to secrete acetic acid and butyric acids, whereas B. coagulans only produce acetic acid67. Here, we demonstrated, for the first time, that B. aryabhattai HY1 produced butyric acid and acetic acid. Taking together, dual SCFA production of B. aryabhattai HY1 strengthening the novelty of this bacteria as a direct SCFA-contributing probiotic.

SCFAs such as butyric and acetic acids, actively regulate anti-inflammatory signaling pathways and maintain gut immune homeostasis via SCFA receptors such as GPR43 and GPR109A68,69. Butyric acid serves as an energy source for probiotics and promotes mucin synthesis, thereby enhancing epithelial barrier integrity and preventing pathogen adherence70. These acids penetrate target cell membranes of pathogens in their undissociated hydrophobic state, causing cytoplasmic acidification and subsequent cell death18. Glucose levels in the small human intestine typically range from 50 to 500 mM, peaking above 300 mM after eating71. During digestion, complex carbohydrates are hydrolyzed into simple sugars such as glucose, fructose, and galactose, which can serve as substrates for fermentation and SCFAs production by probiotics72,73. Our results showed that B. aryabhattai HY1 can produce ample amounts of butyric acid and acetic acid, which inhibit pathogenic bacteria. However, as these findings are based on in vitro analyses, further in vivo investigations are necessary to validate its functional properties, safety, and efficacy within host systems.

Conclusion

In this study, B. aryabhattai HY1 was isolated from Vietnamese pickled mustard greens (Brassica juncea). The strain exhibited strong tolerance to simulated gastrointestinal conditions, maintaining high viability under acidic (pH 3) and bile salt (0.3%) environments. B. aryabhattai HY1 showed susceptibility to ampicillin (30–40 µg/mL) and amoxicillin (25–40 µg/mL), as well as inhibitory activity against common pathogenic bacteria including E. coli, S. aureus, S. typhimurium, and P. aeruginosa. Moreover, glucose fermentation by B. aryabhattai HY1 led to the production of acetic and butyric acids, which can support gut barrier integrity, mucosal immunity, and host metabolic health. Based on these findings, B. aryabhattai HY1 holds promise for potential incorporation into functional food products, dietary supplements, or fermented food formulations. Comprehensive in vivo studies and genomic safety evaluations are necessary to confirm the probiotic efficacy, stability, and safety.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

La Anh, N. Health-promoting microbes in traditional Vietnamese fermented foods: A review. Food Sci. Human Wellness 4, 147–161 (2015).

Fang, Z., Hu, Y., Liu, D., Chen, J. & Ye, X. Changes of phenolic acids and antioxidant activities during potherb mustard (Brassica juncea, Coss.) pickling. Food Chem. 108, 811–817 (2008).

Ness, A. R. & Powles, J. W. Fruit and vegetables, and cardiovascular disease: a review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 26, 1–13 (1997).

Block, G., Patterson, B. & Subar, A. Fruit, vegetables, and cancer prevention: A review of the epidemiological evidence. Nutr. Cancer 18, 1–29 (1992).

Kimura, K. & Yokoyama, S. Trends in the application of Bacillus in fermented foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 56, 36–42 (2019).

Nguyen, T. T. M., Mai, T. D. L., Nguyen, P. T. & Tran, V. T. Identification of a New Candida Tropicalis Yeast Strain Possessing Antagonistic Activity Against the Spoilage Bacteria Isolated From the Fermented Vegetable Products. VNU Journal of Science: Natural Sciences and Technology (2016).

Zayabaatar, E. et al. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Increases the GABA in Rice Seed for Upregulation of Type I Collagen in the Skin. Curr. Microbiol. 80, 128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-023-03233-z (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Effects of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis on growth performance, immunity, short chain fatty acid production, antioxidant capacity, and cecal microflora in broilers. Poult. Sci. 100, 101358 (2021).

Sánchez, B. et al. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 61, 1600240 (2017).

Hong, H. A. et al. The safety of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus indicus as food probiotics. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 510–520 (2008).

Elshaghabee, F. M., Rokana, N., Gulhane, R. D., Sharma, C. & Panwar, H. Bacillus as potential probiotics: Status, concerns, and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1490 (2017).

Todorov, S. D., Ivanova, I. V., Popov, I., Weeks, R. & Chikindas, M. L. Bacillus spore-forming probiotics: Benefits with concerns?. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 48, 513–530 (2022).

Marteau, P., Seksik, P. & Jian, R. Probiotics and intestinal health effects: A clinical perspective. Br. J. Nutr. 88, s51–s57 (2002).

Unban, K., Kodchasee, P., Shetty, K. & Khanongnuch, C. Tannin-tolerant and extracellular tannase producing Bacillus isolated from traditional fermented tea leaves and their probiotic functional properties. Foods 9, 490 (2020).

Zulkhairi Amin, F. A. et al. Probiotic properties of Bacillus strains isolated from stingless bee (Heterotrigona itama) honey collected across Malaysia. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 17, 278 (2020).

Dangsawat, O. et al. Bacillus aryabhattai CKNJh11 as a promising probiotic improves growth performance and egg quality in laying hens. Sci. Rep. 15, 13659 (2025).

Tepaamorndech, S. et al. Effects of Bacillus aryabhattai TBRC8450 on vibriosis resistance and immune enhancement in Pacific white shrimp. Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 86, 4–13 (2019).

Mahjoory, Y., Mohammadi, R., Hejazi, M. A. & Nami, Y. Antifungal activity of potential probiotic Limosilactobacillus fermentum strains and their role against toxigenic aflatoxin-producing aspergilli. Sci. Rep. 13, 388 (2023).

Larsen, N. et al. Characterization of Bacillus spp. strains for use as probiotic additives in pig feed. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 1105–1118 (2014).

Hooper, L. V. et al. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science 291, 881–884 (2001).

Parada Venegas, D. et al. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 10, 277 (2019).

Nguyen, T. D., Prykhodko, O., Hållenius, F. F. & Nyman, M. Monobutyrin reduces liver cholesterol and improves intestinal barrier function in rats fed high-fat diets. Nutrients 11, 308 (2019).

Ashaolu, T. J., Ashaolu, J. O. & Adeyeye, S. A. Fermentation of prebiotics by human colonic microbiota in vitro and short-chain fatty acids production: A critical review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 130, 677–687 (2021).

Singh, B., Halestrap, A. P. & Paraskeva, C. Butyrate can act as a stimulator of growth or inducer of apoptosis in human colonic epithelial cell lines depending on the presence of alternative energy sources. Carcinogenesis 18, 1265–1270 (1997).

Terasaki, M. et al. Acetic acid is an oxidative stressor in gastric cancer cells. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 63, 36–41 (2018).

Lindh, J. M., Terenius, O. & Faye, I. 16S rRNA gene-based identification of midgut bacteria from field-caught Anopheles gambiae sensu lato and A. funestus mosquitoes reveals new species related to known insect symbionts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7217–7223 (2005).

Round, J. L. et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science 332, 974–977 (2011).

Khalil, E. S., Abd Manap, M. Y., Mustafa, S., Alhelli, A. M. & Shokryazdan, P. Probiotic properties of exopolysaccharide-producing Lactobacillus strains isolated from tempoyak. Molecules 23, 398 (2018).

Lee, N.-K., Kim, S.-Y., Choi, S.-Y. & Paik, H.-D. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis KU201 having antifungal and antimicrobial properties isolated from kimchi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 22, 1–5 (2013).

Patel, A. K., Ahire, J. J., Pawar, S. P., Chaudhari, B. L. & Chincholkar, S. B. Comparative accounts of probiotic characteristics of Bacillus spp. isolated from food wastes. Food Res. Int. 42, 505–510 (2009).

CLSI, C. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 25th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2015).

Nsa, I. Y. & Omolere, B. M. Draft genome sequence and annotation of Priestia aryabhattai strain BD1 isolated from a dye sediment. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 12, e01175-e11122 (2023).

Shahid, M. et al. Stress-tolerant endophytic isolate Priestia aryabhattai BPR-9 modulates physio-biochemical mechanisms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for enhanced salt tolerance. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 19, 10883 (2022).

Srithaworn, M., Jaroenthanyakorn, J., Tangjitjaroenkun, J., Suriyachadkun, C. & Chunhachart, O. Zinc solubilizing bacteria and their potential as bioinoculant for growth promotion of green soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.). PeerJ 11, e15128 (2023).

Jena, P. K. et al. Isolation and characterization of probiotic properties of lactobacilli isolated from rat fecal microbiota. Microbiol. Immunol. 57, 407–416 (2013).

Nwagu, T. N. et al. Evaluation of the probiotic attributes of Bacillus strains isolated from traditional fermented African locust bean seeds (Parkia biglobosa), “daddawa”. Ann. Microbiol. 70, 1–15 (2020).

Sarkar, P., Hasenack, B. & Nout, M. Diversity and functionality of Bacillus and related genera isolated from spontaneously fermented soybeans (Indian Kinema) and locust beans (African Soumbala). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 77, 175–186 (2002).

Hong, H. A., Duc, L. H. & Cutting, S. M. The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29, 813–835 (2005).

Dan, Z. et al. Effects of fishmeal substitution by four fermented soybean meals on growth, antioxidant capacity and inflammation responses of turbot juveniles (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Aquaculture 560, 738414 (2022).

Moore, T., Globa, L., Barbaree, J., Vodyanoy, V. & Sorokulova, I. Antagonistic activity of Bacillus bacteria against food-borne pathogens. J Prob Health 1, 110 (2013).

Thakur, N., Rokana, N. & Panwar, H. Probiotics: Selection criteria, safety and role in health and disease. J. Innov. Biol. 3, 259–270 (2016).

Berthold-Pluta, A., Pluta, A. & Garbowska, M. The effect of selected factors on the survival of Bacillus cereus in the human gastrointestinal tract. Microb. Pathog. 82, 7–14 (2015).

Sumathi, C., Nandhini, A. & Padmanaban, J. Antagonistic activity of probiotic Bacillus megaterium against Streptococcus mutans. Int J Pharm Bio Sci 8, 270–274 (2017).

Rajabi, S., Darban, D., Tabatabaei, R. R. & Hosseini, F. Antimicrobial effect of spore-forming probiotics Bacillus laterosporus and Bacillus megaterium against Listeria monocytogenes. Arch. Microbiol. 202, 2791–2797 (2020).

Shahverdi, S., Barzegari, A. A., Bakhshayesh, R. V. & Nami, Y. In-vitro and in-vivo antibacterial activity of potential probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Heliyon 9, e14641 (2023).

Bhattacharyya, C. et al. Genome-guided insights into the plant growth promotion capabilities of the physiologically versatile Bacillus aryabhattai strain AB211. Front. Microbiol. 8, 411 (2017).

Lunavath, M., Bhukya, B. & Swamy, M. Plant growth promoting microbes with antibiotic resistance; can that be used together. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2364433/v1 (2022).

Deng, C. et al. Molecular mechanisms of plant growth promotion for methylotrophic Bacillus aryabhattai LAD. Front. Microbiol. 13, 917382 (2022).

on Additives, E. P. et al. Guidance on the characterisation of microorganisms used as feed additives or as production organisms. Efsa J. 16, e05206 (2018).

O’Connell Motherway, M. et al. Report of the Scientific Committee of the Food Safety Authority of Ireland on the Assessment of the safety of “probiotics” in food supplements. Report No. 2940–1399, (Wiley Online Library, 2024).

Shewale, R. N., Sawale, P. D., Khedkar, C. D. & Singh, A. Selection criteria for probiotics: A review. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 9(1/2), 17 (2014).

Samedi, L. & Charles, A. L. Evaluation of technological and probiotic abilities of local lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 9–19 (2019).

Huang, Y. & Adams, M. C. In vitro assessment of the upper gastrointestinal tolerance of potential probiotic dairy propionibacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 91, 253–260 (2004).

Fernández, M. F., Boris, S. & Barbes, C. Probiotic properties of human lactobacilli strains to be used in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 449–455 (2003).

Kowalczyk, M., Znamirowska-Piotrowska, A., Buniowska-Olejnik, M. & Pawlos, M. Sheep milk symbiotic ice cream: Effect of inulin and apple fiber on the survival of five probiotic bacterial strains during simulated in vitro digestion conditions. Nutrients 14, 4454 (2022).

Minekus, M. et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food–an international consensus. Food Funct. 5, 1113–1124 (2014).

Sharma, A., Kawarabayasi, Y. & Satyanarayana, T. Acidophilic bacteria and archaea: acid stable biocatalysts and their potential applications. Extremophiles 16, 1–19 (2012).

Swapna, H. C., Rai, A. K., Halami, P. M. & Sachindra, N. M. Isolation and characterization of potential lactic acid bacteria (LAB) from freshwater fish processing wastes for application in fermentative utilisation of fish processing waste. Braz. J. Microbiol. 42, 1516–1525 (2011).

Giri, S. S., Sukumaran, V. & Dangi, N. K. Characteristics of bacterial isolates from the gut of freshwater fish, Labeo rohita that may be useful as potential probiotic bacteria. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 4, 238–242 (2012).

Du Toit, M. et al. Characterisation and selection of probiotic lactobacilli for a preliminary minipig feeding trial and their effect on serum cholesterol levels, faeces pH and faeces moisture content. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 40, 93–104 (1998).

Kristoffersen, S. M. et al. Low concentrations of bile salts induce stress responses and reduce motility in Bacillus cereus ATCC 14570. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5302–5313 (2007).

Li, Y., Tang, X., Chen, L., Xu, X. & Li, J. Characterization of a nattokinase from the newly isolated bile salt-resistant Bacillus mojavensis LY-06. Foods 11, 2403 (2022).

Rungsirivanich, P. et al. Culturable bacterial community on leaves of Assam tea (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) in Thailand and human probiotic potential of isolated Bacillus spp. Microorganisms 8, 1585 (2020).

Song, M. et al. Bacillus coagulans restores pathogen-induced intestinal dysfunction via acetate–FFAR2–NF-κB–MLCK–MLC axis in Apostichopus japonicus. MSystems 9, e00602-00624 (2024).

Jacquier, V. et al. Bacillus subtilis 29784 induces a shift in broiler gut microbiome toward butyrate-producing bacteria and improves intestinal histomorphology and animal performance. Poult. Sci. 98, 2548–2554. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey602 (2019).

Sarmikasoglou, E. et al. Effects of Bacillus subtilis on in vitro ruminal fermentation and methane production. Trans. Animal Sci. 8, TXA054. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txae054 (2024).

Calvigioni, M. et al. HPLC-MS-MS quantification of short-chain fatty acids actively secreted by probiotic strains. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1124144. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1124144 (2023).

Maslowski, K. M. & Mackay, C. R. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 5–9 (2011).

Singh, N. et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 40, 128–139 (2014).

Peng, L., Li, Z.-R., Green, R. S., Holzmanr, I. R. & Lin, J. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Nutr. 139, 1619–1625 (2009).

Almeida-Suhett, C. P., Scott, J. M., Graham, A., Chen, Y. & Deuster, P. A. Control diet in a high-fat diet study in mice: Regular chow and purified low-fat diet have similar effects on phenotypic, metabolic, and behavioral outcomes. Nutr. Neurosci. 22, 19–28 (2019).

Hall, J. E. & Hall, M. E. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology E-Book: Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology E-Book. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2020).

Nelson, D. L., Lehninger, A. L. & Cox, M. M. Lehninger principles of biochemistry. (Macmillan, 2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ton Duc Thang University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H.Y.N. and M.K.L. were in charge of experiments; P.T.U.N. analyzed data; M.T.P. wrote, edited, and reviewed manuscript; C.T.D. designed and interpreted study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. M.T.P. is the guarantor of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pham, M.T., Nguyen, P.T.U., Nguyen, T.H.Y. et al. Evaluation of probiotic properties of Bacillus aryabhattai HY1 isolated from Vietnamese pickled mustard greens. Sci Rep 15, 42613 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26744-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26744-0