Abstract

E-cigarette use is rapidly increasing worldwide, yet its impact on mental health and hormonal regulation during withdrawal remains poorly understood. Cytidine-5′-diphosphocholine (CDP-choline) is a neuroprotective compound that may alleviate withdrawal-related disturbances. Methods: This study evaluated the effects of e-cigarette exposure and subsequent CDP-choline treatment on withdrawal-induced anxiety and hormonal changes in a rat model. Thirty-five adults male Wistar rats were randomly assigned to five groups: control (room air), e-cigarette exposure, e-cigarette exposure + CDP-choline, e-cigarette quitting + CDP-choline, and CDP-choline only. Animals were exposed to e-cigarette vapor for six weeks, followed by either continued exposure at reduced duration or cessation, with CDP-choline administered during the final three weeks. Anxiety-like behavior was assessed using the light–dark box test, and serum nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and β-endorphin concentrations were quantified by ultra-fast liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UFLC-MS/MS). Results: Chronic e-cigarette exposure increased serum nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and β-endorphin levels compared with controls, and was associated with withdrawal-induced anxiety. CDP-choline treatment reduced serum nicotine and cotinine concentrations, normalized adrenaline and β-endorphin levels, and improved behavioral outcomes, as indicated by increased time spent in the light chamber and reduced stretching frequency. Conclusion: CDP-choline mitigates the biochemical and behavioral disturbances associated with e-cigarette exposure and withdrawal, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic strategy for nicotine dependence. Future studies incorporating pharmacokinetic profiling, long-term efficacy assessment, and inclusion of female subjects are warranted to further clarify its mechanisms and clinical applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) are nicotine delivery devices, that utilize a battery to heat and aerosolize e-liquid, which is held in a refillable reservoir, producing vapor for the user to inhale1,2,3. The liquid often consists of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and different flavoring ingredients in addition to nicotine4. E-cigs are available in a variety of nicotine concentrations ranging from 0 to 36 mg/mL, as well as a variety of flavors designed to appeal to kids and teens5. In the past ten years, e-cigs have become more readily available, with an estimated 58.1 million users in 2018 and 68 million in 2020 globally6. Furthermore, e-cigs are frequently marketed as safer alternatives to conventional cigarettes and even as a tool for quitting smoking since they are expected to have lesser amounts of toxins than traditional tobacco products7. Unfortunately, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) appears to lack standards for e-cigs as therapeutic medicine delivery systems and plans to regulate them as tobacco products8.

Several studies have indicated that e-cigs produce a visible and inhalable aerosol, not just nicotine vapor, as wrongly claimed by e-cig companies. E-cig aerosols contain measurable amounts of toxins, such as formaldehyde, benzene, acetaldehyde, acrolein, phenols, metals, and reactive oxygen species2,9,10. Additionally, e-cig usage can cause damage by inhaling the stimulant substance nicotine, which can create dependency and increase exposure to the e-cig aerosol11. This leads to continual inhalation of toxins that can be generated when propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin are heated5,12,13.

Previous studies have shown that e-cig exposure can impair development and produce an allergy-based asthma inflammatory response in mice14,15. E-cigs can also increase oxidative stress and inflammation in mice and decrease immunological responses against bacterial and viral infections16. Moreover, several studies have shown that nicotine addiction causes cognitive and working memory impairments, mood disorders such as stress, and anxiety-like symptoms17,18. Consistent with the above, Results from animal experiments suggest that chronic nicotine exposure, whether through minipumps, intravenous self-administration, or other delivery methods, results in dependence characterized by withdrawal symptoms such as somatic signs, anxiety, and anhedonia, as indicated by an elevated reward threshold19,20,21. Although fewer studies have directly modeled withdrawal using e-cigarette vapor19,20,21, emerging evidence suggests that chronic e-cig exposure can similarly induce nicotine dependence and withdrawal-like behaviors.

A recent study has shown the impact of e-cigs on the adrenal gland cortex, which concluded that e-cig exposure developed histopathological changes in the adrenal cortex structure, with significant improvement in its histological structure and biochemical activity following discontinuation22. Smoking also impacts pituitary, thyroid, adrenal, testicular, calcium metabolism, and insulin action in our body23,24. Furthermore, a prior study demonstrated that nicotine interacts with receptors in the adrenal medulla, resulting in a rise in blood pressure, accelerated respiratory rate, a faster heart rate, and raised levels of glucose in the blood due to enhanced release of adrenaline and noradrenaline25.

Cytidine-5-phosphocholine (CDP-choline) is an intermediate in phosphatidylcholine production, a necessary component of cellular membranes, and a cell signaling mediator26. It is delivered orally, intravenously, or intracerebroventricularly and converted to choline and cytidine/uridine via the Kennedy pathway27, resulting in elevated plasma and tissue concentrations of these metabolites28. CDP-choline has been used to treat traumatic brain injury29 and cerebral ischemia30, showing positive results, great tolerance, and few adverse effects31,32. Its protective impact has been linked to membrane stability by suppressing phospholipase A activation, maintaining sphingomyelin levels, and boosting phosphatidylcholine33,34. An initial investigation discovered that CDP-choline reduces oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia35. Although CDP-choline has shown potential benefits in some neurodegenerative conditions, as suggested by preclinical and limited clinical studies36,37,38, also it can reduce inflammation via the peripheral cholinergic system by mediating α7 nicotine acetylcholine receptors on macrophages28.

Thus, in the present study, we investigate the effect of chronic e-cig exposure and CDP-choline treatment on different hormonal levels including adrenalin, and beta-endorphins, alongside an assessment of serum nicotine and its primary metabolite, cotinine. Furthermore, the effect of e-cig exposure, as well as CDP-choline treatment on anxiety-like behavior was examined.

Materials and methods

Drugs

VOOPOO DRAG M100S e-cig, Nasty mango juice (0.3% nicotine, 70/30 vegetable glycerin/propylene glycol, ~ 5% mango flavor), CITICOLIN (250 mg Cytidine − 5’-diphosphocholine, Cognizin, Kyowa Hakko Bio Co., Ltd.).

Animal management

Thirty-five male adult Wistar rats weighing (180–200 g) were inbred at Applied Science Private University in Jordan. Animals were acclimated for 1 week in a vivarium room, kept on a (12-h/12-h light/dark cycle), and maintained under a controlled temperature (23 ± 2 °C) and humidity (50 ± 5%). At the end of the experiment, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) until total reflex loss was obtained, ensuring profound anesthesia. Euthanasia was subsequently carried out by decapitation while the animals were thoroughly sedated. All animal experiments were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy at Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan (Approval No.: 2023-PHA-26). All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and national regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 to ensure rigorous and transparent reporting of animal research.

For biochemical and behavioral testing, the rats were divided into 5 groups (n = 7), as follows (see Fig. 1A):

-

Control group (C): Exposed to room air only throughout the entire 9-week period and received no treatment. This group served as the baseline reference.

-

E-cigarette exposure group (E-cig): Exposed to e-cigarette vapor for 9 weeks without any pharmacological intervention. For the first 6 weeks, animals were exposed for 2 h per day, 5 days per week. During the final 3 weeks, exposure was reduced to 1 h per day to simulate gradual cessation.

-

E-cigarette exposure + CDP-choline treatment group (E-cig + CDP): Exposed to e-cigarette vapor for 6 weeks, followed by CDP-choline treatment during the final 3 weeks while continuing e-cigarette exposure at the reduced duration (1 h/day).

-

E-cigarette quitting + CDP-choline treatment group (E-cig quitting + CDP): Exposed to e-cigarette vapor for 6 weeks, followed by complete cessation of exposure and initiation of CDP-choline treatment for the remaining 3 weeks.

-

CDP-choline only group (CDP): Exposed to room air throughout the 6-week period and received CDP-choline treatment during the final 3 weeks only.

Rat weight evaluation

Rats were weighed three times for each phase at the baseline, during the withdrawal, and post-treatment to evaluate changes occurring through the experiment.

Behavioral tests

In the DLB test, the apparatus consists of two chambers one of which is lighted (40 × 40 × 40 cm) and the other is darkened (20 × 40 × 40 cm) with an entrance between them (7.5 × 8.5 cm). Rats are introduced into the light compartment, where they investigate the surrounding area until they discover the entrance to the dark chamber. The light chamber was illuminated by a neon tube on the ceiling, generating a brightness of 150 lx in the center of the box39. Each rat was placed in the apparatus for 10 min at each session40, and the time spent in the light chamber, latency to enter the dark chamber, and frequency of stretching were recorded. All chambers are cleansed with water after each session.

Twenty-four hours before the experiment, rats went through a behavioral test to have baseline behavioral data. A Canon digital camera was used to record the videos. The behavioral test was manually assessed by an observer who was blind to the experiment. The behavioral test was used to measure anxiety-like behavior using the dark and light box test (DLB). After obtaining the behavior results, rats were divided into five groups with a similar average baseline in behavior and weight.

E-cig exposure setting

Rats were exposed to e-cigarette vapor in a custom-designed acrylic chamber (50 × 50 × 50 cm) for a total of 9 weeks. During the first 6 weeks (exposure phase), animals were subjected to 2 h of whole-body exposure per day, 5 days per week, using two VOOPOO DRAG M100S devices (Coil: PnP-TW20 (0.2 Ω), Glass Container: 5 mL, UK) filled with Nasty e-liquid (3 mg/mL nicotine, ~ 5% mango flavor, 70/30 vegetable glycerin/propylene glycol). For each 2-hour session, two cartridges (9 mL total, 27 mg nicotine) were consumed, delivered in 5-second puffs with 20-second inter-puff intervals.

Beginning in week 7 (treatment phase), exposure protocols were modified according to group assignment. The E-cig group continued exposure at a reduced duration of 1 h/day to simulate gradual tapering. The E-cig + CDP group received CDP-choline while continuing 1-hour/day exposure. The E-cig quitting + CDP group underwent complete cessation of e-cig exposure and received CDP-choline. Control and CDP-only groups were maintained under room air conditions.

Serum collection

Blood samples were collected at three main time points for all groups: at baseline prior to e-cigarette exposure (week 0), after the 6-week exposure phase (week 6), and at the end of the 3-week treatment or cessation phase (week 9)41. For the E-cig and E-cig + CDP groups, post-exposure samples were obtained immediately after the final e-cigarette session at week 6 in order to capture peak nicotine and cotinine levels and minimize variability associated with exposure timing. For the Control, CDP-only, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups, samples were collected on the same schedule under identical environmental conditions to ensure comparability. In addition, to illustrate within-group temporal changes, an intermediate sample was collected from the E-cig (2 h) group during the final 2-hour exposure session in week 6; this is presented in Fig. 4 as an additional time point but does not represent a separate experimental group. All collections were performed using retro-orbital bleeding under light anesthesia with intraperitoneal administration of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). After collection, blood was allowed to clot for 45 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 5500 rpm for 15 min to obtain serum, which was then used for all biochemical analyses. Whole blood was not analyzed.

Experimental timeline and exposure setup. (A) Study design showing five groups (n = 7 each): Control (room air), E-cig (2 h/day for 6 weeks then 1 h/day for 3 weeks), E-cig + CDP (same exposure with CDP-choline during weeks 7–9), E-cig quitting + CDP (2 h/day exposure for 6 weeks followed by cessation with CDP-choline during weeks 7–9), and CDP only (room air with CDP-choline during weeks 7–9). (B) Diagram of the custom acrylic chamber (50 × 50 × 50 cm) used for whole-body e-cigarette exposure with two VOOPOO DRAG M100S devices delivering 5-second puffs every 20 s. This figure has been created using Biorender scientific illustration software.

Absolute body weight of rats across study groups. Mean ± SEM body weights are shown for Control, E-cig, E-cig + CDP, E-cig quitting + CDP, and CDP groups (n = 7 each) at baseline, post-exposure (week 6), and post-treatment (week 9). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time (p < 0.0001), indicating progressive weight gain across all groups, with no significant Treatment or Time × Treatment effects.

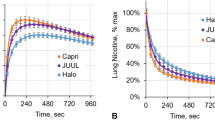

Behavioral testing in the DLB test (mean ± SEM). (A) Time spent in the light chamber of the DLB in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, E-cig quitting + CDP, control, and CDP groups at different time points; (B ) Latency to enter the dark chamber of the DLB in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, E-cig quitting + CDP, control, and CDP groups at different time points (C) Frequency of stretching of the DLB in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, E-cig quitting + CDP, control, and CDP groups at different time points (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 7 for each group).

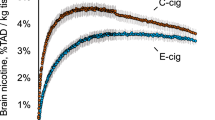

Serum concentrations of nicotine (A), cotinine (B), adrenaline (C), and β-endorphins (D) in rats across experimental groups. Groups include: Control (C), E-cigarette exposure 2 h/day for 6 weeks with reduced exposure to 1 h/day during weeks 7–9 (E-cig), E-cigarette exposure 1 h/day with CDP-choline treatment during weeks 7–9 (E-cig + CDP), E-cigarette quitting with CDP-choline treatment during weeks 7–9 (E-cig quitting + CDP), and CDP-choline only (CDP). An additional intermediate sample from the E-cig (2 h) group was collected during the final 2-hour exposure session at week 6 and is shown as a within-group time point for illustration; this does not represent a separate experimental group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with Control. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 indicate significant differences between the E-cig (1 h) group and its CDP-treated counterparts (E-cig + CDP and E-cig quitting + CDP). Symbols placed above the E-cig (2 h) group indicate significant differences compared to all other groups.

Quantitation of serum nicotine, cotinine, adrenalin, and β-endorphin via Ultra-fast liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UFLC-MS/MS)

Nicotine and cotinine

This study used a validated SHIMADZU UFLC-MS/MS system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) to determine the concentration of nicotine and cotinine in rat serum. The chromatographic procedures involved the use of a C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, 0.5 μm) with 75% acetonitrile and 0.05% formic acid as mobile phase in an isocratic elution at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min in a total run time of 4 min. The internal standard used in this experiment was methanol. The eluted compounds were detected using LCMS-8030As LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPH MASS SPECTROMETER-Triple Quad MS (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) supplied with an electrospray ionization source (ESI) running in positive ionization mode to generate [M + H] + ion at m/z 162.23, 176.21 for nicotine and cotinine, respectively. The parameters were optimized as follows: source temperature 120 °C, desolvation temperature 300 °C, desolvation gas flow 600 L/h, and cone gas flow 60 L/h. The capillary voltage was set at 3 kV, while the cone voltage was set at 15 V and high-purity nitrogen was used during the MS operations.

Adrenaline

The same UFLC-MS/MS system was carried out to determine the concentration of adrenaline in rat serum. The chromatographic procedures involved the use of a C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) with a binary mobile phase mixture of methanol and water (50:50, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/minute in a total run time of 3.8 min. The eluted compounds were detected using the same MS-TQ system supplied with an ESI source running in positive ionization mode to generate [M + H] + ion at m/z 184 for adrenalin.

β-endorphins

UFLC-MS/MS system was carried out to determine the concentration of β-endorphins in rat serum. The chromatographic procedures involved the use of a C18 column (100 mm × 1.8 mm, 1.7 μm) with a binary mobile phase mixture of methanol and water (55:45, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/minute in a total run time of 4.2 min. The eluted compounds were detected using an MS-TQ system supplied with an ESI source running in positive ionization mode to generate [M + H] + ion at m/z 3529 for β-endorphins.

Statistical analysis

Data were compiled as means and standard errors of the means (SEM). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, followed by One-way ANOVA as well as Tukey multiple comparisons, were used to analyze data for weight, and behavioral tests. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used to investigate the hormonal levels. All results were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Differences were considered to be statistically significant at probability values of P equal or less than 0.05.

Results

Effect of e-cig whole body exposure and CDP treatment on rats’ weights

Absolute body weight measurements across baseline, post-exposure (week 6), and post-treatment (week 9) are shown in Fig. 2. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F (1.82, 54.49) = 165.8, p < 0.0001], indicating that all animals gained weight progressively throughout the study. Neither the main effect of Treatment [F (4, 30) = 1.19, ns] nor the Time × Treatment interaction [F (8, 60) = 1.36, ns] reached significance. The body weight gain occurred irrespective of exposure or CDP-choline treatment condition.

Effect of e-cig exposure and CDP treatment on DLB test

E-cig exposure caused withdrawal-induced anxiety in the DLB test that developed after 6 weeks of e-cig exposure, seen as a decrease in the time spent in the light chamber, as demonstrated in Fig. 3A. This effect was reversed by treatment with CDP. This pattern of effects was confirmed by repeated measures of two-way ANOVA, which revealed a significant main effect of Time [F (1.71, 51.30) = 9.32, p = 0.0007], a significant main effect of Treatment [F (4, 30) = 3.84, p = 0.012] and a significant Time × Treatment interaction [F (8, 60) = 3.38, p = 0.0029]. Tukey multiple comparison tests revealed a significant decrease in time spent in the light chamber in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups compared to control and CDP groups after the exposure phase. This effect was reversed after 21-days of CDP treatment. There was a significant difference in time spent in the light chamber in the e-cig group compared to the control, and CDP groups, but there was no difference between E-cig + CDP, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups compared to control and CDP groups. A similar pattern was observed for latency to enter the dark chamber. Repeated measures of two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F (1.47, 43.94) = 6.54, p = 0.0069] and a significant main effect of Treatment [F (4, 30) = 6.43, p = 0.0007] and a significant Time × Treatment interaction [F (8, 60) = 2.36, p = 0.028]. Tukey multiple comparison tests revealed a significant decrease in latency to enter the dark chamber in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups compared to control and CDP groups after the exposure phase. There was a significant decrease in latency to enter the dark chamber in the e-cig group compared to E-cig quitting + CDP, control, and CDP groups after 21-days of CDP treatment, as shown in Fig. 3B. In the same manner, the frequency of stretching was increased after e-cig exposure in the E-cig, E-cig + CDP, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups compared to the control and CDP groups. Repeated measures of two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F (1.71, 51.39) = 10.55, p = 0.0003] and a significant main effect of Treatment [F (4, 30) = 9.02, p < 0.0001] and a significant Time × Treatment interaction [F (8, 60) = 5.39, p < 0.0001]. Tukey multiple comparison tests revealed a significant increase in the frequency of stretching in E-cig, E-cig + CDP, and E-cig quitting + CDP groups compared to control and CDP groups after the exposure phase. There was a significant increase in the frequency of stretching in the e-cig group compared to E-cig quitting + CDP, control, and CDP groups after 21-days of CDP treatment, as shown in Fig. 3C.

Effect of e-cig exposure and CDP treatment on serum nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and β-endorphins concentrations

The analysis of nicotine concentrations in rat serum following exposure to e-cig vaping with and without CDP-cytidine treatment reveals significant differences. When compared to the negative control, nicotine levels were significantly higher in both the 2-hour and 1-hour e-cig exposure groups, with mean differences of -8.250 and − 5.100, respectively, indicating strong significance (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0002). However, the addition of CDP-cytidine to the 1-hour e-cig group reduced the nicotine concentration, showing no significant difference compared to the control (mean diff. -1.250, p = 0.1955), as shown in Fig. 4A. Similarly, e-cig quitting combined with CDP-cytidine treatment did not significantly differ from the control (mean diff. -1.090, p = 0.2883). When comparing different e-cig exposure durations, the 2-hour exposure had substantially higher nicotine concentrations than the 1-hour group (mean diff. 3.150, p = 0.0035), with CDP-cytidine reducing nicotine levels in both cases. Nicotine levels in the CDP-cytidine alone group showed no difference from the control (p > 0.9999). Additionally, comparisons between e-cig exposure treated CDP-cytidine-treated groups confirmed a substantial nicotine reduction, particularly between the 2-hour exposure and the CDP-treated groups (p < 0.0001).

Figure 4B illustrates cotinine concentrations in rat serum following exposure to e-cig aerosol with and without CDP-cytidine treatment and shows significant variations across different conditions. Cotinine levels were markedly higher in the 2-hour and 1-hour e-cig exposure groups compared to the negative control, with mean differences of -633.7 and − 343.0, respectively, showing strong statistical significance (p < 0.0001). In contrast, the addition of CDP-cytidine to the 1-hour e-cig exposure group significantly reduced cotinine levels (mean diff. -242.7, p < 0.0001), though still higher than the control. The e-cig quitting group combined with CDP-cytidine showed a further reduction in cotinine levels, with a smaller yet significant difference from the control (mean diff. -122.7, p = 0.0167). Cotinine levels in the CDP-cytidine alone group showed no significant difference from the control (p > 0.9999). When comparing the e-cig exposure groups, the 2-hour exposure showed significantly higher cotinine levels than the 1-hour group (mean diff. 290.7, p < 0.0001). Similarly, cotinine levels were significantly lower in the 1-hour e-cig group when CDP-cytidine was introduced (mean diff. 100.3, p = 0.0287). The most substantial reduction in cotinine levels was observed between the 2-hour e-cig group and the quitting group with CDP-cytidine (mean diff. 511.0, p < 0.0001); highlighting CDP-cytidine’s potential to reduce cotinine concentrations. Moreover, significant differences were noted when comparing the 1-hour e-cig exposure group to its CDP-treated counterparts (mean diff. 220.3, p < 0.0001). In Fig. 4, significant differences between cytidine-treated and untreated 1-hour e-cig exposure groups are indicated by # symbols.

Adrenaline levels were notably higher in the 2-hour and 1-hour e-cig exposure groups compared to the control (p < 0.0001), as illustrated in Fig. 4C. CDP-cytidine treatment significantly reduced adrenaline levels in both the 1-hour e-cig (p = 0.0027) and e-cig quitting groups (p = 0.0416), while CDP-cytidine alone showed no effect. The 2-hour e-cig group had significantly higher levels than the 1-hour group (p = 0.0068), but CDP-cytidine treatment further reduced levels (p = 0.0143). The most significant reduction occurred in the 2-hour exposure group with CDP treatment (p < 0.0001), highlighting CDP-cytidine’s role in lowering adrenaline levels across different exposure durations.

In addition, beta-endorphin levels in rat serum after e-cig exposure, with and without CDP-cytidine, show significant results, as shown in Fig. 4D. Both the 2-hour and 1-hour e-cig exposure groups had markedly higher beta-endorphin levels compared to the control (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0001, respectively). CDP-cytidine treatment reduced levels in the 1-hour exposure group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.0893), nor was it significant in the e-cig quitting group (p = 0.7377). The 2-hour e-cig group had significantly higher levels than the 1-hour group (p = 0.0015), and CDP treatment further lowered beta-endorphin levels across all groups (p < 0.0001), with the largest reduction seen in the 2-hour exposure group. However, no significant differences were found between the CDP-treated and quitting groups.

Discussion

E-cig exposure and CDP treatment were examined for the first time on withdrawal-induced anxiety, and serum hormone levels. This study shows that e-cig exposure alters nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and beta-endorphin levels in rats, affecting hormonal balance and behavior. These data also suggest that CDP-choline (cytidine) may reduce the adverse effects of e-cigs.

Chronic exposure to e-cig in this study resulted in significantly elevated serum levels of nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and beta-endorphin. Nicotine and its primary metabolite, cotinine, are well-known to interfere with the normal functioning of the endocrine system by triggering the release of catecholamines such as adrenaline. This elevation in catecholamines, particularly adrenaline, leads to heightened stress responses and is consistent with previous studies linking nicotine exposure to increased oxidative stress and inflammation42,43.

Beta-endorphin, a hormone linked to the body’s pain and stress response systems, was also significantly increased following e-cig exposure, particularly in the 2-hour group. This finding aligns with reports that nicotine can stimulate the release of endogenous opioids like beta-endorphins, which contribute to nicotine’s reinforcing effects and addictive properties44. The elevated beta-endorphin levels observed in this study suggest that e-cig exposure may enhance the rewarding and addictive potential of nicotine, creating a cycle that reinforces dependency and exacerbates hormonal dysregulation in exposed animals42.

E-cig-exposed rats’ nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and beta-endorphin levels were significantly reduced by CDP-choline for 3 weeks, especially in the 1-hour exposure and quitting groups. CDP-choline reduces these effects by restoring cell membrane phospholipid metabolism, increasing neurotransmitter production (especially acetylcholine), and improving neural plasticity45. The observed reduction in serum nicotine and cotinine levels following CDP-choline treatment may indicate a pharmacokinetic interaction, such as altered metabolism, distribution, or clearance. However, as this study did not include dedicated pharmacokinetic analyses, we cannot confirm the underlying mechanism. Future work incorporating pharmacokinetic profiling and metabolic pathway analyses will be essential to clarify whether CDP-choline’s effects are mediated primarily through pharmacokinetic modulation or involve additional neurobiological pathways.

In this study, CDP-choline treatment notably reduced anxiety-like behaviors, as evidenced by the LDB results. These behavioral improvements coincide with reductions in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress46.

CDP-choline also had a pronounced effect on the reduction of adrenaline and beta-endorphin levels, particularly in the quitting + CDP group. This suggests that CDP-choline may aid in the normalization of stress hormone levels post-exposure, which is critical for recovery from nicotine addiction and withdrawal symptoms47. The lower levels of these hormones observed in the CDP-treated groups likely contributed to the reduction in anxiety behavior, as excessive levels of adrenaline and beta-endorphins are associated with stress and mood disorders48,49.

The control and CDP-treated groups had similar beta-endorphin levels, demonstrating the compound’s potential to restore hormonal balance without causing abnormal hormonal reactions. This reinforces research indicating that CDP-choline reduces external stresses and maintains endocrine system homeostasis50. Multifaceted processes explain CDP-choline’s protective properties. It is commonly known that CDP-choline is a precursor of phosphatidylcholine, a significant cell membrane component. This helps maintain membrane fluidity, release neurotransmitters, and repair neurons51.

These findings have important implications for developing therapeutic strategies to mitigate the harmful effects of e-cigarette use. This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the absence of an “e-cig quitting only” group (i.e., animals exposed to e-cigarettes for six weeks and then analyzed during withdrawal without CDP-choline treatment) restricts our ability to determine whether the observed improvements in the quitting + CDP group were attributable to nicotine withdrawal alone, CDP-choline treatment, or a combination of both. Including such a group in future experiments would allow clearer interpretation of treatment-specific effects. Second, the study did not incorporate pharmacokinetic profiling, which limits our ability to fully explain whether reductions in nicotine and cotinine levels were due to altered metabolism, distribution, or clearance mechanisms. Third, only male rats were included, so potential sex-related differences in nicotine dependence, withdrawal responses, and CDP-choline effects remain unexplored. Finally, the study duration was relatively short, and long-term efficacy or potential rebound effects after treatment cessation were not assessed. Addressing these limitations in future work will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic potential of CDP-choline in nicotine dependence and withdrawal.

Conclusion

This study provides strong evidence that chronic e-cig exposure leads to significant hormonal disruptions and increased anxiety-like behavior. CDP-choline treatment was effective in reversing these effects by reducing serum nicotine, cotinine, adrenaline, and beta-endorphin levels, as well as improving behavioral outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Unger, M. & Unger, D. W. E-cigarettes/electronic nicotine delivery systems: a word of caution on health and new product development. J. Thorac. Disease. 10 (Suppl 22), S2588 (2018).

Garcia-Arcos, I. et al. Chronic electronic cigarette exposure in mice induces features of COPD in a nicotine-dependent manner. Thorax 71 (12), 1119–1129 (2016).

Siegel, M. B., Tanwar, K. L. & Wood, K. S. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 40 (4), 472–475 (2011).

Peace, M. R. et al. Concentration of nicotine and glycols in 27 electronic cigarette formulations. J. Anal. Toxicol. 40 (6), 403–407 (2016).

Shao, X. M. et al. A mouse model for chronic intermittent electronic cigarette exposure exhibits nicotine pharmacokinetics resembling human vapers. J. Neurosci. Methods. 326, 108376 (2019).

Jerzyński, T. et al. Estimation of the global number of e-cigarette users in 2020. Harm Reduct. J. 18 (1), 1–10 (2021).

Marques, P., Piqueras, L. & Sanz, M. J. An updated overview of e-cigarette impact on human health. Respir. Res. 22 (1), 1–14 (2021).

Benowitz, N. L. & Goniewicz, M. L. The regulatory challenge of electronic cigarettes. Jama 310 (7), 685–686 (2013).

Eaton, D. L. et al. Toxicology of E-cigarette constituents, in Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes (National Academies Press (US), 2018).

Flach, S., Maniam, P. & Manickavasagam, J. E-cigarettes and head and neck cancers: A systematic review of the current literature. Clin. Otolaryngol. 44 (5), 749–756 (2019).

Miliano, C. et al. Modeling drug exposure in rodents using e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems. J. Neurosci. Methods. 330, 108458 (2020).

Khlystov, A. & Samburova, V. Flavoring compounds dominate toxic aldehyde production during e-cigarette vaping. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (23), 13080–13085 (2016).

Conklin, D. J. et al. Electronic cigarette-generated aldehydes: the contribution of e-liquid components to their formation and the use of urinary aldehyde metabolites as biomarkers of exposure. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 52 (11), 1219–1232 (2018).

Lappas, A. S. et al. Short-term respiratory effects of e‐cigarettes in healthy individuals and smokers with asthma. Respirology 23 (3), 291–297 (2018).

Clapp, P. W. & Jaspers, I. Electronic cigarettes: their constituents and potential links to asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 17, 1–13 (2017).

Sussan, T. E. et al. Exposure to electronic cigarettes impairs pulmonary anti-bacterial and anti-viral defenses in a mouse model. PloS One. 10 (2), e0116861 (2015).

Naha, N. et al. Nicotine and Cigarette Smoke Modulate Nrf2-BDNF-Dopaminergic Signal and Neurobehavioral Disorders in Adult Rat Cerebral cortex#. Vol. 37. 540–556 (Human & Experimental Toxicology, 2018).

Goldwater, D. S. et al. Structural and functional alterations to rat medial prefrontal cortex following chronic restraint stress and recovery. Neuroscience 164 (2), 798–808 (2009).

McLaughlin, I., Dani, J. A. & De Biasi, M. Nicotine withdrawal. In The Neuropharmacology of Nicotine Dependence. 99–123 (2015).

Malin, D. H. et al. Rodent model of nicotine abstinence syndrome. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 43 (3), 779–784 (1992).

Grabus, S. D. et al. Nicotine place preference in the mouse: influences of prior handling, dose and strain and Attenuation by nicotinic receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology 184, 456–463 (2006).

Agaga, R. A., Elsammak, G. A. & Amer, N. A. Effect of Electronic Cigarette Exposure on the Adrenal Cortex of Adult Male Albino Rats and the Possible Effect of its Withdrawal (Histological and Immunohistochemical Study) (Egyptian Journal of Histology, 2023).

Tweed, J. O. et al. The endocrine effects of nicotine and cigarette smoke. Trends Endocrinol. Metabolism. 23 (7), 334–342 (2012).

Kapoor, D. & Jones, T. Smoking and hormones in health and endocrine disorders. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 152 (4), 491–499 (2005).

Mishra, A. et al. Harmful effects of nicotine. Indian J. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 36 (01), 24–31 (2015).

Adibhatla, R. M. & Hatcher, J. F. Citicoline decreases phospholipase A2 stimulation and hydroxyl radical generation in transient cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. Res. 73 (3), 308–315 (2003).

Stremmel, W. et al. Phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) and the mucus layer: evidence of therapeutic efficacy in ulcerative colitis? Dig. Dis. 28 (3), 490–496 (2010).

Gurun, M. S. et al. The effect of peripherally administered CDP-choline in an acute inflammatory pain model: the role of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Anesth. Analgesia. 108 (5), 1680–1687 (2009).

Zafonte, R. et al. The citicoline brain injury treatment (COBRIT) trial: design and methods. J. Neurotrauma. 26 (12), 2207–2216 (2009).

Ortega, G. et al. Citicoline treatment prevents neurocognitive decline after a first ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 29 (Suppl 2), 268–288 (2010).

Saver, J. L. Citicoline: update on a promising and widely available agent for neuroprotection and neurorepair. Rev. Neurol. Dis. 5 (4), 167–177 (2008).

Cho, H. J. & Kim, Y. J. Efficacy and safety of oral citicoline in acute ischemic stroke: Drug surveillance study in 4,191 cases. In Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. Vol. 31(3). 171–176 (2009).

Lee, J. M. et al. A nuclear-receptor-dependent phosphatidylcholine pathway with antidiabetic effects. Nature 474 (7352), 506–510 (2011).

Liu, Y. et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid-enriched phosphatidylcholine attenuated hepatic steatosis through regulation of cholesterol metabolism in rats with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids 52, 119–127 (2017).

Hernández-Esquivel, L. et al. Cardioprotective properties of citicoline against hyperthyroidism-induced reperfusion damage in rat hearts. Biochem. Cell Biol. 93 (3), 185–191 (2015).

Mir, C. et al. CDP-choline prevents glutamate-mediated cell death in cerebellar granule neurons. J. Mol. Neurosci. 20, 53–59 (2003).

Blusztajn, J. K., Slack, B. E. & Mellott, T. Neuroprotective actions of dietary choline. Nutrients 9 (8), 815 (2017).

Baumel, B. S. et al. Potential neuroregenerative and neuroprotective effects of uridine/choline-enriched multinutrient dietary intervention for mild cognitive impairment: a narrative review. Neurol. Therapy. 10 (1), 43–60 (2021).

Griebel, G., Perrault, G. & Sanger, D. J. Characterization of the behavioral profile of the non-peptide CRF receptor antagonist CP-154,526 in anxiety models in rodents comparison with diazepam and buspirone: comparison with diazepam and Buspirone. Psychopharmacology 138, 55–66 (1998).

Belovicova, K. et al. Animal tests for anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in rats. Interdisciplinary Toxicol. 10 (1), 40 (2017).

Sharma, A. et al. Safety and blood sample volume and quality of a refined retro-orbital bleeding technique in rats using a lateral approach. Lab Anim. 43 (2), 63–66 (2014).

Picciotto, M. R. & Kenny, P. J. Mechanisms of nicotine addiction. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 11 (5), a039610 (2021).

Chatterjee, S. et al. Acute exposure to e-cigarettes causes inflammation and pulmonary endothelial oxidative stress in nonsmoking, healthy young subjects. Am. J. Physiology-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 317 (2), L155–L166 (2019).

Zalewska-Kaszubska, J. Beta-endorphin peptide and some selected psychiatric disorders. J. Psychiatry Stud. 1(1),1-7 (2018).

Secades, J. J. & Frontera, G. CDP-choline: pharmacological and clinical review. In Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. Vol. 17. 1–54 (1995).

Xu, M. et al. Choline Deficiency and Choline Metabolism Disorders can Lead to Anxiety-Like Behaviors Induced by DSS in IBD Mice. (2022).

Torres, O. V. et al. Nicotine withdrawal increases stress-associated genes in the nucleus accumbens of female rats in a hormone-dependent manner. Nicotine Tob. Res. 17 (4), 422–430 (2015).

Merenlender-Wagner, A., Dikshtein, Y. & Yadid, G. The β-endorphin role in stress-related psychiatric disorders. Curr. Drug Targets. 10 (11), 1096–1108 (2009).

Imam-Fulani, A. & Owoyele, B. V. Effect of caffeine and adrenaline on memory and anxiety in male Wistar rats. Nigerian J. Physiological Sci. 37 (1), 69–76 (2022).

Secades, J. Citicoline in the treatment of cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Exp. Neurosci. 5 (1), 14–26 (2019).

Arenth, P. M. et al. CDP-Choline as a Biological Supplement During Neurorecovery: A Focused Review. Vol. 3(6). S123–S131 (PM&R, 2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Applied Science Private University, Jordan for supporting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. and A.K. conceptualized and designed the study. D.R. and S.A. contributed to data collection and initial drafting. M.B. and W.A. performed data analysis and interpretation. A.K., S.A., and M.A.S. contributed to literature review and manuscript editing. M.B. supervised the project and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and ARRIVE compliance

All animal experiments were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy at Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan (Approval No.: 2023-PHA-26). All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and national regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 to ensure rigorous and transparent reporting of animal research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barakat, M., Alzaghari, L.F., Al-Najjar, M.A.A. et al. E-cigarette exposure and CDP choline modulate withdrawal- induced anxiety and hormonal levels in rats. Sci Rep 15, 42715 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26799-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26799-z