Abstract

Karst reservoir Computed Tomography (CT) images exhibit blurred boundaries, scale variations, and complex structures. Existing 3D U-Net-based segmentation methods are inadequate in both detail recognition and overall structural representation. Therefore, this paper proposes an improved 3D U-Net architecture to adapt to the multi-scale and low-contrast characteristics of karst reservoirs. This paper introduces a multi-scale input path at the encoder end, extracting volumetric features at different resolutions in parallel to capture both fine-grained holes and large-scale channels. A spatial attention module is embedded in the skip connections to weight the encoded features to highlight boundaries and key regions. Multi-scale features are fused during the decoding phase to gradually reconstruct the three-dimensional space. Furthermore, the Dice loss is combined with the gradient-based boundary-aware loss during training. The latter enhances boundary sensitivity by calculating the 3D gradient difference between the predicted image and the label image. Experimental results show that the improved complete model achieves an 87.8% Dice coefficient and a 1.9-pixel boundary error in karst reservoir CT image segmentation, improving both regional overlap and boundary accuracy. This method effectively identifies karst structures at different scales, providing reliable data support for complex reservoir modeling and analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

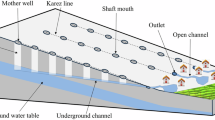

Karst reservoirs are widely found in carbonate rock regions. Their internal structure is typically composed of complex karst units such as fractures, caves, and pores. These structures directly determine the reservoir’s permeability and oil and gas accumulation patterns. With the increasing application of industrial CT technology in the geological field, the automatic identification and accurate modeling of three-dimensional karst structures based on CT images has become an important direction for complex reservoir research1,2. However, traditional image processing methods have difficulty in reliably extracting structural information3,4. Although voxel-level segmentation models based on deep learning have certain advantages, they still face challenges in detail recognition, boundary preservation, and expression of spatial structural continuity5,6. While multi-scale architectures and attention mechanisms have been used in medical image segmentation, their applicability to complex geological structures, particularly karst reservoirs, faces unique challenges. While target structures in images typically have relatively regular boundaries and stable topology, karst structures exhibit strong heterogeneity, complex branching connectivity, and extreme scale variations, ranging from micron-scale pores to centimeter-scale caves.

Previous studies have attempted to use three-dimensional convolutional neural networks for semantic segmentation of geological CT data, and have achieved initial progress7,8. The standard 3D U-Net model, due to its end-to-end structure and multi-layer feature fusion capabilities, has been applied to voxel segmentation of geological data9,10. Although the standard 3D U-Net model has the advantages of end-to-end segmentation and multi-layer feature fusion, it still has limitations in preserving the fine pores and channel connectivity of karst reservoirs and boundaries. While single-scale 3D U-Nets perform well in medical and material 3D segmentation tasks, they lack sensitivity to scale variations and boundary details in complex spatial structures. Some work has introduced attention mechanisms to improve the model’s responsiveness to key structures, while others have employed multi-scale feature extraction to enhance the recognition of karst morphologies at different scales11,12. However, these methods often fail to balance fine boundary recognition with overall structural integrity when processing karst structures, particularly in terms of karst channel connectivity and spatial geometric continuity. Consequently, an effective segmentation framework for identifying karst reservoir structures has yet to be established13,14.

To address these issues, this study proposes an improved 3D U-Net for karst reservoir CT images. Compared to traditional 3D U-Nets, this method employs multi-resolution input paths at the encoder end to extract volumetric features at different scales in parallel, adapting to the significant size differences of karst structures. The multi-scale input pathway and spatial attention module proposed in this paper are not simply transplanted, but are specifically optimized to maintain karst topological connectivity. The multi-scale pathway processes volume data of different resolutions in parallel, aiming to systematically capture the cross-scale network of pores, holes, and fractures, preventing small-scale channels from being overwhelmed by a single pathway. The spatial attention module is precisely embedded in skip connections, which strengthens the response to fuzzy boundaries and key connected nodes, which is crucial for maintaining the topological integrity of the karst network. In addition, although the boundary-aware loss is based on the Sobel operator, its selection is based on the voxel characteristics of the three-dimensional geological data. Compared with complex topological losses, this loss function is computationally efficient and can directly optimize the boundary gradient field. When combined with the Dice loss, it can effectively improve the geometric accuracy of structural edges while maintaining regional overlap. These collaborative designs targeting geological problems constitute the core innovation of this method.

Related works

Karst reservoirs, under long-term hydrogeological influences, have formed complex karst structures such as fractures, pores, and caves. These structures are characterized by strong heterogeneity, irregular topology, and a wide range of scales15,16. In CT images, these structures often exhibit discontinuous grayscale, blurred boundaries, and dense small-scale features, making it difficult to accurately separate the target area in the image17,18. In addition, karst structures of different scales exhibit significant differences in spatial distribution in volumetric images. Large-scale structures may span multiple slices, while small-scale structures are easily submerged by noise, increasing the difficulty of automatic 3D segmentation and spatial structure recognition19,20. In high-resolution CT data, the complex channel connectivity and detail accuracy place higher demands on the model’s structural modeling capabilities. In recent years, with the widespread application of deep learning in three-dimensional image processing21,22, automatic segmentation methods based on voxel-level neural networks have become a research hotspot. Among them, U-Net (Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation) and its three-dimensional variant, 3D U-Net, achieve a good balance between semantic understanding and detail restoration due to their encoder-decoder architecture and skip connection mechanism23,24. 3D U-Net can process three-dimensional volumetric data while preserving spatial structural features. It has been validated and promoted in multiple fields, becoming a foundational framework for geoscience image segmentation25,26. In geotechnical engineering, the network has been used for tasks such as core fracture extraction, pore structure identification, and sedimentary structure segmentation, demonstrating strong spatial modeling capabilities and adaptability.

However, the performance of U-Net in karst reservoir imagery remains challenging27,28. On the one hand, the multi-scale nature of karst structures makes it difficult for traditional single-scale input methods to capture the complete structure from microscopic pores to macroscopic caves, resulting in the neglect or misidentification of some small-scale structures29,30. On the other hand, karst boundaries appear fuzzy transitions or even fractures in images, and U-Net’s modeling capabilities at edge regions are insufficient, easily leading to structural adhesion or incomplete recognition31,32. Furthermore, because U-Net typically uses convolutional downsampling, it has inherent limitations in preserving boundary morphology and topological connectivity, which is a limiting factor for geological modeling tasks that require high-fidelity restoration of spatial structures33,34.

To improve the model’s adaptability in complex karst structure segmentation tasks, researchers have attempted to introduce improvements such as multi-scale mechanisms and attention mechanisms into the 3D U-Net framework35,36. One approach uses a pyramid structure or multi-path input to enhance the model’s multi-scale perception capabilities, enabling it to simultaneously focus on feature information at different granularities. Another approach focuses on optimizing feature fusion methods to improve the recognition accuracy of small-scale structures. Some approaches also incorporate boundary information or topological constraints into the loss function design to improve the completeness and edge accuracy of structural restoration37,38.

Despite some progress, current methods still have shortcomings in maintaining karst spatial connectivity, expressing structural integrity, and restoring boundary details. This is particularly true when dealing with the coexistence of micropores and large-scale caves in karst reservoirs. Model segmentation results often exhibit structural fractures, blurred edges, or spatial misjudgments. Therefore, constructing a three-dimensional segmentation network with strong multiscale perception capabilities, high boundary recognition accuracy, and a more complete representation of karst structural spatial characteristics is a key approach to achieving accurate automatic segmentation and structural recognition in karst CT images. This is also the starting point and research foundation for this work.

Table 1 compares the core design differences between our proposed method and standard 3D U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Multi-Scale Pyramid Network. This table compares the proposed method across five dimensions: multi-scale input, attention mechanism, design objectives, boundary optimization strategy, and geological adaptability. The table highlights the innovative features of our proposed method: the use of parallel multi-scale input pathways to capture cross-scale karst structure, the embedding of spatial attention modules at skip connections to enhance boundary and connectivity responses, the core goal of maintaining karst topological connectivity, and the use of a strategy combining Dice and boundary-aware loss. This table clearly demonstrates the uniqueness and targeted nature of our proposed method compared to existing technologies for geological applications.

Multi-scale attention segmentation model for karst reservoir CT images

Overview of the overall network architecture

Figure 1 shows the architecture of a 3D U-Net model with a multi-scale attention mechanism for karst reservoir CT image segmentation. The model has three parallel input paths with different resolutions (1:1, 1:2, and 1:4), each of which feeds into a separate encoder path with a spatial attention module configured on a skip connection. The decoder processes these paths independently before fusing the multi-scale features. The final fusion module combines these features and produces a single-channel output using a 1 × 1 × 1 convolution. This output is then subjected to a sigmoid activation function to generate the final segmentation probability map. The figure clearly illustrates the data flow from multi-scale input to encoding, attention-weighted skip connections, decoding, and finally fusion to the output.

The segmentation model constructed in this paper is based on the 3D U-Net architecture with targeted structural improvements39,40. It adopts a symmetrical encoder-decoder structure. The network input consists of three sets of volumetric data at different scales, generated by multi-level downsampling of the original CT image. These data correspond to voxel images at the original resolution, half resolution, and quarter resolution41,42. The multi-scale input path introduces the encoder module in parallel, improving the network’s ability to respond to features of different spatial scales, such as small cracks and large caves, by capturing cross-scale information. Figure 2 shows the process from raw CT input to 3D label output.

The encoder architecture consists of multiple stacked convolutional layers within each path, enabling deep semantic feature extraction. Each scale path maintains its own voxel structure and spatial distribution characteristics, extracting hierarchical representations without losing detailed information. The output 3D label map has the same spatial dimensions (H × W × D) as the input CT volume but is a single-channel segmentation mask. A skip connection is established between the encoder and decoder, and a spatial attention mechanism is introduced within the connection channel to weight feature maps based on their importance, thereby improving the model’s sensitivity to complex boundary regions and subtle structures.

The decoder uses a multi-level upsampling mechanism to fuse feature maps from different scale paths according to their resolution and gradually restore them to the original voxel size. Each decoding unit receives multi-scale feature maps from the corresponding encoding layer and attention module. After alignment and concatenation, the features are fused to enhance the model’s ability to preserve overall morphology, channel connectivity, and boundary consistency. This feature fusion strategy further balances deep semantics with shallow details, improving modeling of the complex geometric features of karst structures.

The final network output is a 3D label map with the same voxel size as the original input. The modules in this architecture work collaboratively to maintain the integrity of segmentation details while improving boundary discrimination and structural restoration accuracy. This model boasts strong cross-scale modeling capabilities, accurate spatial focus, and good structural continuity, making it suitable for segmenting and identifying complex karst structures in high-resolution CT images.

Multi-scale volume input construction process

The multi-scale input consists of three sets of volumetric data: the original CT volume, the first-level downsampled volume, and the second-level downsampled volume. The original volume is a 3D CT scan image. After linear normalization, the original resolution is kept unchanged and the size is cropped to an integer multiple of eight. The cropping adopts the center cropping strategy. The normalization process is:

The first-level downsampling volume is generated using a three-dimensional average pooling operation with a pooling window size of 2 × 2 × 2, a stride of 2, and no padding, denoted as:

The secondary downsampling volume performs an average pooling operation with the same parameters on the basis of the primary level, and the result is:

The three scales were maintained with spatial resolution ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4, respectively. All pooling operations were performed during preprocessing and fed into the network simultaneously as multi-scale tensors.

The three sets of volumetric data were structured as three input paths, each with its own encoding module within the network. The initial layer of each path consisted of two consecutive 3D convolutional layers with a kernel size of 3 × 3 × 3, a stride of 1, a padding of 1, and a ReLU activation function. The convolution output was defined as:

\({\text{W}}_{{1}}^{\left( l \right)}\) and \({\text{W}}_{{2}}^{\left( l \right)}\) are the convolution weights for the nth path.

Encoding paths do not share parameters and do not perform cross-fusion. Each scale path maintains feature isolation during the encoding phase and is only fused during the decoding phase. The number of channels per path is set to 32, 64, and 96, respectively, from smallest to largest scale. A batch normalization layer is used after the convolutional layer to stabilize the feature distribution.

To prevent feature dimensionality mismatches caused by multi-scale input, all input volumes are uniformly cropped to a fixed dimension during the loading phase. Input tensors are fixed to 1 channel and are not replicated, stacked, or expanded. All input operations are encapsulated in a custom Dataset class. During the data loading phase, tensors at three scales are generated and organized in a dictionary format. These are fed into the model as independent inputs during the forward propagation phase. The three-way data input structure is received through the model-defined multi-input interface and processed synchronously during the network forward propagation. The tensor dimensions are aligned consistently and are not merged.

The multi-scale input paths are architecturally parallel. During the decoding phase, a scale alignment strategy is used to upsample feature maps at different resolutions to a uniform size to avoid information loss. The input paths do not dynamically change based on sample content. The number of paths and resolution settings are fixed in the model definition and do not include conditional branches or dynamic control logic. All dimensionality conversions, tensor concatenation, and pooling calculations are implemented using standard PyTorch modules, without external dependencies or custom operations.

Encoding-side feature extraction and spatial attention embedding

The encoder uses a five-layer symmetrical structure, with each layer consisting of two sets of three-dimensional convolutional units. The convolution kernel size is 3 × 3 × 3, the stride is 1, and zero padding is used to maintain the volume size. Each set of convolution operations is followed by three-dimensional batch normalization and a nonlinear activation function to improve the stability of feature expression and nonlinear modeling capabilities. The input voxel feature of layer \(l\) is \({\text{X}}^{{\left( {\text{l}} \right)}}\), and the convolution operation is:

In order to enhance the depth of feature extraction and suppress gradient disappearance, a short-circuit structure is introduced between convolutional layers to add the input features and convolution output element by element:

This structure remains consistent across all scales, ensuring continuous feature transfer across different layers.

The five levels of downsampling are implemented using a combination of voxel average pooling and 3D convolution with a stride of 2, resulting in a proportional decrease in feature map size and a gradual increase in channel dimension. The pre-sampling feature is \({\text{F}}^{{\left( {\text{l}} \right)}}\), and the downsampling operation is expressed as:

Figure 3 shows the multi-scale intermediate features extracted from the input CT image through each layer of the encoder, showing the single-channel feature map of the corresponding encoding layer and its size change. The red arrows indicate the direction of the jump connection. Each panel displays a representative 2D slice from the feature map. The number of channels increases with depth (e.g., 32, 64, 96, …), while spatial dimensions are downsampled.

During the downsampling process, uncompressed feature maps at each scale are retained as skip connection sources to support high-resolution reconstruction in the subsequent decoding stage.

Volume data of varying resolutions generated by the multi-scale input path is fed into its corresponding encoding branch, maintaining a consistent structure and performing independent processing. To integrate information at different scales, the output of each encoder layer is connected to the corresponding decoder layer via skip connections. A spatial attention module is inserted before each skip path to enhance the response of the target region and suppress background interference.

The spatial attention module consists of two parallel channel compression paths, performing global average pooling and max pooling in the voxel slice dimension and axial dimension, respectively. Assuming the encoded feature map is \({\text{F}}\), the pooled output is:

The output feature maps of the two paths are concatenated and fed into a 3D convolutional layer with a kernel size of 7 × 7 × 7. A sigmoid function is then applied to generate a spatial attention weight map. This weight map is element-wise multiplied with the original encoded features from the skip connection to produce a weighted spatial feature response. The processed feature map maintains the same structure as the original feature map, without affecting dimensional alignment.

All attention modules operate only within the skip connection, highlighting boundaries and structural details during cross-scale fusion. The weighted result is concatenated with the upsampled output of the decoder and fed into the subsequent decoding module for feature reconstruction.

Decoder structure and multi-scale fusion strategy

The decoder constructs a multi-layered progressive upsampling structure, corresponding to the encoder’s multi-scale outputs, to achieve step-by-step restoration of spatial dimensions. For each encoder scale output, a transposed convolution operation is used for spatial upsampling, with an upsampling step of 2. Assuming the encoder output of layer \({\text{l}}\) is \({\text{E}}^{{\left( {\text{l}} \right)}}\), the upsampling process is defined as:

\({\text{k}}\), \({\text{s}}\), \({\text{p}}\) are the convolution kernel size, stride, and padding, respectively.

After spatial alignment, the feature maps corresponding to the encoder scale are concatenated, with concatenation performed along the channel dimension:

Figure 4 shows the upsampled feature maps of the encoder, the feature maps of the corresponding layers of the decoder, and the feature distribution of the two after fusion via skip connections. The fusion result preserves the details of the encoded features in terms of spatial structure while introducing high-resolution information from the decoded features, demonstrating the integration of multi-scale information during the decoding process. Color variations represent the intensity of feature activations, with warmer colors indicating higher response values.

After concatenation, a 3D convolution module is used for fusion. The convolution kernel size remains at 3 × 3 × 3, and the number of channels matches the number of channels in the concatenated features.

The decoder is designed with independent branches for multi-scale encoded outputs, each handling upsampling and fusion operations at the corresponding scale to avoid cross-scale interference. After decoding, each branch produces a feature map with a uniform spatial size. To achieve effective multi-scale feature fusion, the decoded outputs of all branches are concatenated along the channel dimension when the spatial dimensions are completely consistent. The concatenated multi-scale feature maps are input into multi-layer convolutional units for channel-dimensional compression and feature fusion. The convolution kernel size remains at 3 × 3 × 3, with the number of channels gradually reduced. Nonlinear activations are added to the intermediate layers of the fusion module to improve feature recognition and spatial consistency.

For spatial alignment, a combination of nearest neighbor interpolation and trilinear interpolation is used for upsampling, ensuring a smooth transition in the spatial distribution of the upsampled feature maps. For the skip connection features at the encoder end, the spatial dimensions are cropped or padded based on the upsampling results to ensure that the sizes of the feature maps are fully matched during the splicing operation, avoiding fusion failures caused by inconsistent shapes. The post-splitting feature fusion module introduces depthwise separable convolution instead of standard convolution, reducing the number of parameters and computational burden while retaining the ability to extract spatial features.

A multi-scale fusion module is designed at the end of the decoder. This module receives multi-scale features from different branches, first integrates the number of channels through a series of convolutional layers, and then compresses the features into a single-channel prediction map using 1 × 1 × 1 convolution. This module uses group normalization instead of batch normalization to adapt to small-batch training environments and improve model stability. The fused feature map is mapped to the [0,1] interval by a sigmoid activation function to map the original feature value and generate the final single-channel probability map as the segmentation prediction output.

While maintaining a multi-scale parallel decoding structure, all decoding operations rigorously implement spatial scale alignment, channel fusion, and feature compression steps. This ensures effective integration of multi-scale information and maximizes the preservation of the rich spatial details extracted during the encoding phase, meeting the requirements for 3D karst spatial structure recognition.

Joint loss function implementation

The joint loss function consists of two parts: voxel-level region similarity measurement and boundary structure accuracy constraint. The region similarity part uses the Dice loss function, and the boundary accuracy part constructs a gradient-based boundary-aware loss function. The Dice loss function optimizes the overlap between the voxel label and the predicted map, and includes the product and square terms of the predicted map and the label map. The formula is:

\(p_{i}\) is the predicted value, \(g_{i}\) is the true label value, and \(\varepsilon\) is a constant. This loss function is highly sensitive to small objects and can improve recall of small structural areas such as karst channels.

The boundary-aware loss function uses voxel gradient fields as a guide to enhance the model’s sensitivity to changes in boundary position. This loss is based on the Sobel operator, which calculates the gradient image between the predicted image and the label image along three axes to obtain the boundary response value in three dimensions. The formulas for calculating the gradient image are:

\(K_{x}\), \(K_{y}\), \(K_{z}\) are Sobel kernels, and \(I\) is the input image. This paper performs the above operations on the prediction image and the label image respectively, calculates the corresponding gradient magnitude map, and then solves the L1 loss between the two. The formula is:

\(\nabla p_{i}\) and \(\nabla g_{i}\) are the gradient magnitudes of the predicted and labeled images at the ith voxel, respectively, and \(N\) is the total number of voxels.

The total loss function is a weighted combination of the Dice loss and the boundary loss. The weights are empirically set based on the difference between boundary error and voxel accuracy at the beginning of training. The joint loss function is defined as:

\(\lambda\) is a weighting factor, set to 0.6 in the experiment to strike a balance between region overlap and boundary accuracy. Figure 5 shows a comparison of the predicted results and the true labels in the gradient domain, including the predicted gradient, the label gradient, and their difference map. The gradient magnitude map of the predicted results reflects the location and strength of the predicted boundary; the difference between the two is visualized to intuitively reflect the deviation between the predicted boundary and the true boundary. The difference map magnifies the local deviation of the boundary position and is used to qualitatively evaluate the positioning accuracy of the model at the edge rather than reflecting the similarity of the overall structure.

This loss function performs loss calculation and backpropagation optimization on all predicted voxels in each training round. Boundary loss provides edge shape constraints in the early stages of model training, while Dice loss is used later to improve overall segmentation consistency and enhance the model’s adaptability to the complex boundary structures of karst. This loss function directly uses the Sigmoid probability map output by the network (rather than the binary map after threshold segmentation) and the label map for gradient calculation, avoiding the error caused by threshold segmentation and making the optimization target smoother.

3D structural evaluation metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s ability to restore karst structures in 3D space, this paper defines three structural evaluation metrics: connectivity preservation rate, structural integrity, and spatial geometric accuracy.

Connectivity Preservation Rate: This metric measures the consistency of topological connectivity between the predicted structure and the true label. First, Connected Component Analysis (CCA) is performed on both the predicted results and the true label, using a 26-neighborhood (6-connectivity in 3D) rule to define voxel connectivity. Then, the maximum intersection over union (IoU) between each connected component in the predicted result and all connected components in the true label is calculated. If the maximum IoU exceeds a preset threshold (set to 0.5 in this study), the predicted component is considered correctly identified. The connectivity preservation rate is defined as the ratio of the number of correctly identified predicted components to the total number of connected components in the true label.

Structural Integrity: This metric quantifies the proportion of voxels lost or incorrectly generated during the segmentation process. It is measured by calculating the volumetric difference between the predicted result and the true label. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where \(V_{pred}\) and \(V_{gt}\) represent the total volume (i.e., number of voxels) of the predicted segmentation result and the true label, respectively. This metric reflects the voxel-level fidelity of the model in reconstructing the overall shape of the structure.

Spatial Geometric Accuracy: This metric evaluates the average distance between the predicted and true boundaries. This study uses the Average Surface Distance (ASD) based on a distance transform as a metric. First, the boundary voxels of the true and predicted labels are extracted to generate a binary boundary map. Then, a three-dimensional distance transform is performed on one boundary map to obtain the shortest Euclidean distance from each boundary voxel to the other boundary map. Spatial Geometric Accuracy is defined as the average of these distances. This metric is sensitive to boundary deviation; smaller values indicate higher geometric accuracy.

Experimental design and setup

Dataset construction and preprocessing

The experimental core samples were collected from a typical karst region drilling project in Guizhou Province, with limestone as the predominant lithology. Eight core sections exhibiting karst pore structures were selected, each measuring 7.6 cm in diameter and 30 cm in length. Three-dimensional morphological analysis revealed that the voxel diameter distribution of karst structures in the samples ranged from 50 µm to 12 mm, with micro-pores (< 1 mm) accounting for approximately 68%, small cavities (1–5 mm) making up about 25%, and large cavities (> 5 mm) representing roughly 7%. Three-dimensional scanning was performed using a commercial micron-class industrial CT system, with a resolution of 50 µm and an output reconstructed voxel size of 512 × 512 × 1024. Each core image was cropped to obtain a volumetric area of 512 × 512 × 512, with a voxel spacing of 0.05 mm (i.e., 50 μm). While publicly available datasets such as the Digital Porosity Medium Portal provide abundant carbonate rock samples, this study focuses on eight core samples from a single geological background to ensure consistent experimental conditions and comparable results. Future work will explore the model’s generalization capabilities across regional and multi-source datasets.

The image data was volumetrically cropped into non-overlapping sub-blocks of 128 × 128 × 64. A single core set generated approximately 256 samples, for a total of 2048 sub-block samples. To avoid data leakage due to spatially adjacent sub-blocks, this study adopted a core-wise partitioning strategy. Specifically, eight independent core samples were divided into training, validation, and test sets by number, ensuring that all sub-blocks from the same core belonged to only one set. The specific partitioning was as follows: the training set contained five cores (numbered #1, #2, #3, #4, and #5), totaling 1280 samples; the validation set contained two cores (numbered #6 and #7), totaling 512 samples; and the test set contained one core (numbered #8), totaling 256 samples. The partitioning ratio was approximately 7:1.5:1.5.

The ground-truth labels were manually drawn layer by layer by three experienced geological image annotators using ITK-SNAP software. All annotations were cross-verified twice, and consistent regions were selected as final labels. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was used to assess annotation consistency, with an average value of 0.87. Labels were generated using binary voxel masks, with karst areas labeled as 1 and background as 0.

During preprocessing, min–max normalization was used to adjust the CT value distribution of each image to the range [0, 1]. To ensure that feature map sizes remained integer after five times of downsampling by a factor of 2, all input volumes were cropped or padded to an integer multiple of 8 spatial dimensions. The specific strategy is: for each dimension, if its length L satisfies L % 8 ! = 0, the required padding is calculated as pad = 8—(L % 8), and zero padding of pad//2 and pad—pad//2 is evenly applied at the beginning and end of that dimension. This operation is uniformly performed during data loading using a custom PyTorch Dataset class, ensuring consistent spatial alignment and size processing for all samples (training, validation, and test). To improve the model’s generalization, only the training set was augmented with 3D data. This includes random rotation around an axis (angle range ± 15°), random scaling (ratio 0.9–1.1), voxel mirroring (random flipping along the x, y, and z axes), and the addition of random Gaussian noise (mean 0, standard deviation 0.01). These augmented samples, along with the original samples, form the training input set, which the model uses to learn the characteristics of karst structures at different scales and orientations.

Experimental platform and training parameter settings

The model was trained on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU with 256 GB of host memory and Ubuntu 20.04. The training framework was built using PyTorch 1.12.1 and CUDA 11.6. The AdamW optimizer was used, with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4 and a weight decay factor of 1 × 10−5. A multi-step decay strategy was used, reducing the learning rate to 1/10 at epochs 60, 120, and 160, respectively. The training cycle was set to 200 epochs, with a batch size of 2. All convolutional layers were initialized using the Kaiming Normal method, and the nonlinear activation function used was Leaky ReLU with a negative slope coefficient of 0.01. Group Normalization was used, with each group containing 8 channels to adapt to small-batch training conditions and suppress normalization fluctuations. The sigmoid activation function is used in the training to convert the single channel output into the probability distribution of foreground (karst).

Comparative models and experimental setup

For the comparative experiments, several existing 3D image segmentation network architectures were selected as baseline models, covering typical encoder-decoder architectures, attention mechanisms, and automatic configuration frameworks. Specifically, three mainstream models are included: 3D U-Net, Attention U-Net, and V-Net, representing a standard 3D convolutional architecture, an improved structure incorporating an attention mechanism, and a deep network design with residual connections, respectively. All comparison models maintain a standard architectural implementation, omitting the multi-scale input path and spatial attention module proposed in this paper. Each model uses the same training set, image preprocessing methods, and label format, and is trained using a unified joint loss function. The experimental setup maintains the same number of training rounds, learning rate scheduling strategy, optimizer type, and batch size, and models are trained on a consistent hardware platform to ensure that performance differences are not due to architectural design differences. After training, the output of each model is saved for subsequent performance comparison and analysis.

Karst structure recognition performance evaluation

Comprehensive comparison of segmentation accuracy and matching

For the task of 3D karst channel segmentation, this method was used to conduct comparative experiments on 3D U-Net, Attention U-Net, and V-Net. Evaluation metrics included the Dice coefficient, Intersection over Union (IoU), and Hausdorff distance. Through repeated experiments, the performance distribution of each model was obtained to reflect the stability and variability of the models under different evaluation dimensions. The results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 shows that proposed method achieves an average Dice coefficient of approximately 0.85 and an average Intersection over Union (IoU) of approximately 0.73. The method also exhibits a more concentrated data distribution and improved stability. The Hausdorff distance shows that proposed method achieves the lowest boundary error, averaging approximately 4.9. The advantages of proposed method stem from its multi-scale input and spatial attention mechanism. Multi-scale input (original, 1/2, and 1/4 resolution) improves the model’s ability to recognize structures of varying sizes, and the spatial attention module enhances boundary response. Standard 3D U-Net suffers from large boundary errors due to its single-scale input and lack of an attention mechanism. The joint loss function further optimizes structural continuity, resulting in superior boundary errors for proposed method compared to other models.

Qualitative visualization analysis of slices

This study addresses the issues of blurred karst structure boundaries and scale variations in CT image segmentation of karst reservoirs. A 128 × 128 pixel region with typical vug features was selected for analysis. By comparing the segmentation performance of 3D U-Net, V-Net, Attention U-Net, and an improved model on eight karst vug structures, the accuracy of each model in identifying vug boundary locations and morphological features was examined. Figure 7 shows a comparison of the boundary matching between the four models’ predictions and the ground truth annotations.

As shown in Fig. 7, proposed method achieves the highest prediction accuracy, while 3D U-Net performs the worst. Proposed method’s advantages stem from its multi-scale input and spatial attention mechanism. The multi-scale path simultaneously captures karst structures of varying sizes, while the attention module enhances boundary feature responses, reducing boundary error to 1.9 pixels. In contrast, the standard 3D U-Net, due to its single-scale input and lack of an attention mechanism, struggles to process multi-scale features, resulting in significant offset.

To evaluate the model’s accuracy in identifying karst boundary features in karst reservoir CT image segmentation, this study used three metrics: boundary intersection over union (IoU), average boundary distance, and maximum boundary distance. This quantified the performance differences in boundary segmentation accuracy among 3D U-Net, V-Net, Attention U-Net, and an improved method. Table 2 presents the quantitative analysis results of each model’s boundary segmentation performance.

Proposed method achieved a boundary IoU of 77.8%, with an average and maximum boundary distance of 1.9 pixels and 6.5 pixels, respectively. Attention U-Net ranked second with an IoU of 71.2%, followed by V-Net and 3D U-Net, with the 3D U-Net achieving a maximum boundary deviation of 12.4 pixels. Proposed method effectively captures karst structures of varying sizes and enhances boundary features through multi-scale feature fusion and a spatial attention mechanism, achieving optimal performance across all metrics. 3D U-Net performs poorly on complex boundaries due to its single-scale receptive field and lack of an attention mechanism. Although Attention U-Net incorporates an attention mechanism, its performance still lags behind improved methods due to its lack of multi-scale input.

Comparative analysis of 3D structure restoration ability

This study addresses key technical challenges in 3D reconstruction of karst reservoirs and systematically evaluates four mainstream deep learning models using three core evaluation metrics: connectivity preservation, structural integrity, and spatial geometric accuracy. The experiment used a connectivity assessment algorithm based on topological analysis to calculate the connectivity rate of the hole network, quantified structural integrity through voxel loss detection, and measured geometric accuracy using spatial error mapping based on distance transforms. Figure 8 shows a comparison of the comprehensive performance of each model on these three key indicators.

Proposed method leads in all metrics (connectivity 92.5%, completeness 88.9%, spatial accuracy 86.6%). Attention U-Net follows closely with 83.7% connectivity and 80.2% completeness. V-Net and 3D U-Net perform in descending order, with 3D U-Net performing the worst in spatial accuracy.

The performance differences primarily stem from the feature extraction mechanisms of each model. Proposed method effectively captures the topological connectivity of karst pores through multi-scale feature fusion and a 3D attention mechanism. Its deep feature aggregation strategy ensures the complete restoration of complex structures. In contrast, the 3D U-Net, limited by its single-scale receptive field, struggles to process multi-scale karst features, resulting in poor spatial accuracy. While the V-Net introduces residual connections to improve gradient flow, it still struggles to preserve fine-grained geometric features.

Ablation experiment evaluation

To analyze the contribution of key modules in the improved model, this study designed a systematic ablation experiment. By gradually removing the multi-scale input path, the spatial attention module, and the boundary-aware loss function, the paper quantitatively evaluated the impact of each component on segmentation performance. Under fixed training strategies and test sets, the experiment measured the performance changes of the full model and three simplified variants using the Dice coefficient, intersection-over-union ratio, and Hausdorff distance metrics. Table 3 presents the quantitative results of the impact of each module’s omission on model performance.

Ablation data show that the complete model achieves the best performance (Dice 87.8%, IoU 80.1%, Hausdorff 3.2 mm). Removing the multi-scale input reduces the Dice by 3.3 percentage points to 84.5%. Disabling the spatial attention module reduces the IoU by 4.7 percentage points to 75.4%. Removing the boundary loss function increases the Hausdorff distance to 4.4 mm. The omission of the spatial attention module has the greatest impact on these metrics. Multi-scale input primarily improves the ability to recognize multi-scale structures, but its absence significantly impacts small pore detection. The spatial attention module contributes most to boundary accuracy, with its removal increasing the Hausdorff distance by 56%. Boundary loss primarily optimizes edge localization and has a relatively minor impact. Experiments confirm that multi-scale input and the spatial attention module are core components of the model, synergistically improving segmentation performance.

Error and error region analysis

To evaluate the error characteristics of the model in karst reservoir CT image processing, this study conducted five sets of repeated experiments, measuring the performance of four mainstream models on three key error metrics: false positive rate (FPR), false negative rate (FNR), and relative volume difference (RVD). By controlling the consistency of experimental conditions, the over-segmentation, under-segmentation, and volume estimation bias of the models in karst structure segmentation were systematically analyzed. Figure 9 shows a comparison of the error metrics of the various models across multiple experimental sets.

Based on the numerical distribution, the proposed method’s FPR ranges from 5.4–6.1%, FNR from 6.5–7.2%, and RVD from 3.4–3.9%, lower than the other three methods. These differences are related to the model’s underlying representation and fusion mechanism. This method combines parallel multi-scale input with spatial attention on skip connections to generate a stronger saliency response at the encoder end for karst caves and fissures with varying sizes and blurred boundaries, suppressing background noise and thereby simultaneously reducing both FPR and FNR. Scale alignment and progressive fusion at the decoder enhance structural continuity and voxel consistency, reducing volumetric deviation, resulting in lower RVD. In contrast, 3D U-Net and V-Net are limited in cross-scale detail aggregation and boundary focus, prone to over- and under-segmentation, resulting in high false positives and false negatives. While Attention U-Net incorporates attention, it is limited by its multi-scale input and fusion strategy, resulting in a lower improvement in boundary and volume consistency than proposed method. Consequently, the overall performance of the three errors is intermediate.

Comparative experiments with advanced baseline models

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, this study further compared it with four state-of-the-art baseline models in the fields of medical and industrial image segmentation: 3D nnU-Net, 3D UNet+ + , SwinUNETR, and UNETR. These models represent strong, competitive baselines with automated segmentation, deeply nested structures, and Transformer-based architectures. All comparison models were evaluated under the same experimental setup: using the same training, validation, and test sets as our method, the same image preprocessing pipeline (normalization and data augmentation), and running on the same hardware platform (NVIDIA RTX A6000). 3D nnU-Net, 3D UNet + + , SwinUNETR, and UNETR were trained using their official or widely recognized open-source implementations and their default or recommended hyperparameters to ensure fair comparison. All models were trained using the joint loss function proposed in this paper (Dice + boundary-aware loss) to eliminate the impact of different loss functions. Table 4 reports the performance comparison of the proposed method with these four advanced baseline models on the test set, including Dice coefficient, IoU and Hausdorff distance.

Table 4 compares the performance of our proposed method with four state-of-the-art baseline models: 3D nnU-Net, 3D UNet+ + , UNETR, and SwinUNETR, on a test set of karst reservoir CT images. All models were trained and evaluated using the same dataset, preprocessing pipeline, and joint loss function to ensure a fair comparison. Evaluation metrics include the Dice coefficient, intersection over union (IoU), and Hausdorff distance. The results show that our proposed method achieves optimal performance across all metrics, with a Dice coefficient of 87.8%, an IoU of 80.1%, and the smallest Hausdorff distance of 3.2 mm. SwinUNETR, the strongest baseline model, achieves a Dice coefficient of 86.2%. This comparison fully demonstrates the effectiveness and superiority of our proposed multi-scale input pathway, spatial attention mechanism, and boundary-aware loss function for the specific task of processing karst reservoirs, surpassing current mainstream automated and Transformer architecture models. The method’s advantages stem from its co-designed architecture tailored to geological data characteristics. The parallel multi-scale input pathway effectively captures cross-scale structures from micro-pores to large-scale caverns, while SwinUNETR and UNETR rely on global self-attention mechanisms that are prone to suppressing local details in high-resolution 3D volumetric data and lack sensitivity to small-scale structures. The spatial attention module with embedded skip connections precisely enhances fuzzy boundary responses. In contrast, UNet + + ’ s nested architecture, though improving feature reuse, remains convolution-based with limited receptive fields. Additionally, incorporating boundary-aware loss further optimizes edge geometry accuracy. Therefore, this approach outperforms state-of-the-art architectures that prioritize generalization over task-specific adaptability in specific tasks.

Table 5 compares the computational efficiency and model complexity of the proposed method with current advanced 3D segmentation models. Evaluation metrics include single-iteration time, inference time per sample, and parameter count. The comparison includes 3D nnU-Net, 3D UNet+ + , UNETR, and SwinUNETR, all tested under identical hardware conditions. Results show that despite incorporating multi-scale inputs and spatial attention modules, the proposed method achieves a single-iteration time of 342.1 ms, inference time of 189.3 ms, and 27.8 million parameters. Its overall computational cost is lower than Transformer-based UNETR and SwinUNETR, while delivering faster inference speeds. These results demonstrate that the proposed method maintains high segmentation accuracy while offering excellent computational efficiency and practical deployment potential. This difference primarily stems from the architectural nature: Transformer-based models involve extensive self-attention computations, where time complexity grows quadratically with the number of voxels, resulting in significantly increased computational costs. In contrast, our approach employs a lightweight spatial attention module that operates exclusively at skip connections, achieving lower computational costs. Furthermore, the multi-scale path shares parts of the backbone structure, effectively controlling parameter proliferation. These findings demonstrate that our method achieves superior segmentation performance through targeted design while maintaining efficient inference.

Conclusions

This study addresses the issues of blurred boundaries and significant scale variations in karst structures in CT images of karst reservoirs by proposing an improved 3D U-Net segmentation method. By constructing a multi-scale input path to concurrently extract volumetric features at different resolutions and embedding a spatial attention module within skip connections, the model’s ability to recognize complex karst structures is enhanced. Furthermore, the Dice loss and boundary-aware loss function are combined to optimize the boundary accuracy and structural continuity of the segmentation results. Experimental results demonstrate that this method outperforms competing models in metrics such as the Dice coefficient, Intersection over Union (IoU), and Hausdorff distance, with outstanding performance in terms of boundary error and 3D structural connectivity. Ablation experiments validate the key role of multi-scale input and the spatial attention module. This research provides effective technical support for high-precision modeling of karst reservoirs and has important application value in geological engineering.

While this study has achieved promising results, several limitations remain. First, the model may experience undersegmentation or incorrect connections in areas with extremely low CT image grayscale contrast or highly dense karst channel branches, indicating room for improvement in robustness for extreme complexity scenarios. Second, although the model outperforms advanced baselines in accuracy, the introduction of multi-scale paths and attention mechanisms increases computational overhead compared to standard 3D U-Net, which somewhat limits its real-time processing capability on large-scale datasets. Future work will focus on optimizing network lightweight design, exploring knowledge distillation or dynamic inference strategies to enhance efficiency, and constructing datasets with more challenging samples to further improve the model’s generalization ability and robustness.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, D. et al. Statistical evaluation of accuracy of cross-hole CT method in identifying karst caves. Rock Soil Mech. 45(3), 4–19 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Exploring karst caves in an urban area using surface and borehole geophysical methods. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 84(4), 1–12 (2025).

Xie, P. et al. Application of SPAC method and electromagnetic wave CT in karst detection of Wuhan metro line 8. Geod. Geodyn. 14(5), 513–520 (2023).

Cisneros, M. et al. Exploring a mallorca cave flooding during the little ice age using nondestructive techniques on a stalagmite: micro-CT and XRF core scanning. Quatern. Res. 118, 75–87 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. Automatic karst cave detection from seismic images via a convolutional neural network and transfer learning. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1043218–1043235 (2023).

Character, L. D. et al. Machine learning for cave entrance detection in a Maya archaeological area. Phys. Geogr. 45(4), 416–438 (2024).

Deng, H. et al. Learning 3D mineral prospectivity from 3D geological models using convolutional neural networks: Application to a structure-controlled hydrothermal gold deposit. Comput. Geosci. 161, 105074–105115 (2022).

Fu, H. et al. A 3D convolutional neural network model with multiple outputs for simultaneously estimating the reactive transport parameters of sandstone from its CT images. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 5, 100092–100102 (2024).

Xiaobo, L. I. et al. A 3D attention U-Net network and its application in geological model parameterization. Pet. Explor. Dev. 50(1), 183–190 (2023).

Liu, W. Review of artificial intelligence for oil and gas exploration: Convolutional neural network approaches and the U-Net 3D model. Open J. Geol. 14(4), 578–593 (2024).

Yan, B. et al. 3D karst cave recognition using TransUnet with dual attention mechanisms in seismic images. Geophysics 90(5), 1–63 (2025).

Lin, W., Li, X. & Li, T. Multi-source image feature extraction and segmentation techniques for karst collapse monitoring. Front. Earth Sci. 13, 1543271–1543291 (2025).

Gui, Z. et al. Characterization of fault-karst reservoirs based on deep learning and attribute fusion. Acta Geophys. 73(2), 1335–1347 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Seismic fault identification of deep fault-karst carbonate reservoir using transfer learning. Nat. Gas Ind. B 12, 174–185 (2025).

Pan, Y. et al. Research on stability analysis of large karst cave structure based on multi-source point clouds modeling. Earth Sci. Inf. 16(2), 1637–1656 (2023).

Xu, J. & Wang, Y. Stability analysis and support design methods for rock foundation pit with combination of structural plane and karst cave. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022(1), 5662079–5662092 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Application of electrical resistivity tomography method combined with cross-well seismic computed tomography method in Karst detection in complex urban environment. Appl. Sci. 15(10), 5756–5770 (2025).

Weiwei, L. I., Xin, X. & Aijun, M. Simulation study on the influence of the distance between two boreholes on seismic CT in Karst detection. CT Theory Appl. 31(1), 33–45 (2022).

Li, T. & Xing, J. Research on the 3D visualization method of web-based seismic wave CT results and the application in underground caverns. Buildings 14(11), 3622–3636 (2024).

Guo, S. et al. Characteristics of shallow buried karst and its safety distance to tunnel in wuxi city, China. Quat. Sci. Adv. 13, 100139–100151 (2024).

Dong, L. et al. Application of long-range cross-hole acoustic wave detection technology in geotechnical engineering detection: Case studies of tunnel-surrounding rock, foundation and subgrade. Sustainability 14(24), 16947–16968 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Pore structure characteristics of deep carbonate gas reservoir based on CT scanning. Energy Proc. 43, 3–7 (2024).

Pratama, H. & Latiff, A. H. A. Automated geological features detection in 3D seismic data using semi-supervised learning. Appl. Sci. 12(13), 6723–6748 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. A three-dimensional geological structure modeling framework and its application in machine learning. Math. Geosci. 55(2), 163–200 (2023).

Zhang, H., Zhu, P. & Liao, Z. SaltISNet3D: Interactive salt segmentation from 3D seismic images using deep learning. Remote Sens. 15(9), 2319–2339 (2023).

AlSalmi, H. & Elsheikh, A. H. Automated seismic semantic segmentation using attention U-Net. Geophysics 89(1), WA247–WA263 (2024).

Lin, L. et al. Automatic geologic fault identification from seismic data using 2.5 D channel attention U-Net. Geophysics 87(4), IM111–IM124 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Comparative assessment of U-Net-based deep learning models for segmenting microfractures and pore spaces in digital rocks. SPE J. 29(11), 5779–5791 (2024).

Cheng, H., Zhao, Y. & Feng, K. Subsurface cavity imaging based on UNET and cross-hole radar travel-time fingerprint construction. Remote Sens. 17(12), 1986–2002 (2025).

Polat, A., Keskin, İ & Polat, Ö. Automatic detection and mapping of dolines using U-Net model from orthophoto images. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 12(11), 456–472 (2023).

Wan, J. et al. Deep learning approach for studying forest types in restored karst rocky landscapes: A case study of Huajiang, China. Forests 15(12), 2122–2147 (2024).

Alrabayah, O. et al. Deep-learning-based automatic sinkhole recognition: Application to the eastern dead sea. Remote Sens. 16(13), 2264–2296 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Deep transfer learning for seismic characterization of strike-slip faults in karstified carbonates from the northern Tarim basin. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 9242–9260 (2025).

Creati, N. et al. Mapping of karst sinkholes from LIDAR data using machine-learning methods in the Trieste area. J. Spat. Sci. 70(2), 1–16 (2025).

Rafique, M. U., Zhu, J. & Jacobs, N. Automatic segmentation of sinkholes using a convolutional neural network. Earth Space Sci. 9(2), e2021EA002195-e2021EA002210 (2022).

Huang, Y. & Huang, J. Automatic identification of carbonate karst caves using a symmetrical convolutional neural network. J. Seism. Explor. 31(5), 479–488 (2022).

Shan, L. et al. Single image multi-scale enhancement for rock micro-CT super-resolution using residual U-Net. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 22, 100165–100174 (2024).

Gui, Z. et al. Deep learning-based identification method for fracture-cavity bodies using angle-domain data. J. Appl. Geophys. 241, 105832–105844 (2025).

Mahzad, M. & Bagheri, M. Predictive reconstruction of missing geological events and patterns in real-life 3D post-stack seismic images: A novel U-Net based deep learning approach. Carbonates Evaporites 40(1), 12–24 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Three-dimensional inversion for short-offset transient electromagnetic data based on 3D U-Net. J. Geophys. Eng. 21(3), 922–937 (2024).

Tang, Z. et al. Fault detection via 2.5 d transformer u-net with seismic data pre-processing. Remote Sens. 15(4), 1039–1059 (2023).

Zeng, L. et al. UNetGE: A U-Net-based software at automatic grain extraction for image analysis of the grain size and shape characteristics. Sensors 22(15), 5565–5585 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos: 42272125) National Science and Technology Major Project: No. 2024ZD10011005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and H.W. wrote the main manuscript text; G.X. and X.D.prepared figures; L.J. assisted the first two authors to complete their respective work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Z., Wang, H., Xu, G. et al. Automatic segmentation of karst reservoir CT images and identification of karst spatial structure based on 3D U-Net. Sci Rep 15, 39094 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26802-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26802-7