Abstract

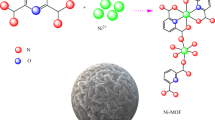

Despite their promise, the low conductivity of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) impedes their effectiveness as electrocatalysts. To address this limitation and boost electron transport and structural stability, functionalization techniques can be applied. This work specifically details the enhancement of Ni-MOF’s electronic structure and activity via TEMPO modification, evaluating its efficacy for alcohol oxidation reactions. The findings are intended to advance the prospects for utilizing MOFs in electrocatalytic applications. The study synthesized TEMPO-modified Ni-MOF (Ni-TEMPO-MOF) via a hydrothermal method and characterized its structure and composition using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). The redox behavior, electrocatalytic activity, and stability were evaluated using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and Chronoamperometry (CA) tests, with a comparative analysis to unmodified Ni-MOF. Experimental results indicate that TEMPO modification optimized the electronic structure of Ni-MOF, enhancing charge transfer efficiency and catalytic performance. The investigation demonstrated that TEMPO functionalization significantly improved the electronic configuration of Ni-MOF, boosting both charge transportation capability and catalytic effectiveness. Electrochemical analysis revealed a 47.0% enhancement in oxidation peak current density for Ni-TEMPO-MOF versus pristine Ni-MOF, along with a 0.04 V reduction in onset potential and improved Tafel slope (86.6 mV/dec), suggesting superior catalytic kinetics. EIS measurements indicated approximately 60% lower charge transfer resistance, while chronoamperometry tests showed enhanced durability with merely 50% current loss after 3600 s, outperforming unmodified Ni-MOF (68% decay). This work establishes that TEMPO incorporation successfully augments the electrical conduction properties and electrocatalytic performance of Ni-MOF, presenting novel approaches for MOF utilization in electrocatalytic oxidation processes and valuable insights for developing efficient electrocatalytic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs), owing to their highly tunable porous structures, abundant active sites, and excellent specific surface area, have demonstrated broad application prospects in areas such as energy conversion and storage, gas separation, and catalysis1,2. In recent years, the application of MOFs in electrocatalysis has emerged as a research hotspot, with transition metal-based MOFs drawing particular attention due to their relatively high conductivity and rich redox activity3. However, MOFs still face two major challenges in electrocatalytic applications: their inherently low conductivity, which restricts efficient electron transport during catalysis,and their susceptibility to structural degradation in complex electrolytic environments such as acidic or alkaline media, which leads to a decline in catalytic activity4,5,6. Previous studies have shown that the chemical stability of MOFs varies depending on the nature of the metal nodes—MOFs constructed with high-valent metals such as Zr and Cr exhibit better stability under acidic conditions, whereas those based on low-valent transition metals such as Ni and Co are more suitable for alkaline systems. This difference primarily arises from the bonding strength between metal nodes and organic ligands, as well as their dissociation tendencies under extreme pH conditions7.

Currently, research on MOFs in the field of electrocatalysis mainly focuses on optimizing their electronic structure and conductivity8. The main strategies include metal center regulation, surface functionalization, and the construction of MOF derivatives. In terms of metal center regulation, researchers have doped transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Mn) into MOFs to modulate their electronic structure, thereby enhancing their electrocatalytic activity9,10. Additionally, some studies have attempted to use post-modification strategies, introducing conductive polymers or carbon-based materials on the surface of MOFs to enhance electron transport capacity and improve the intrinsic conductivity of the materials4,5,11. Another approach is based on the construction of MOF derivatives, where MOFs are converted into metal-carbon composites through high-temperature carbonization to achieve better electrochemical performance12,13). These strategies often face a trade-off between conductivity and structural stability, such as how multi-metal doping may impact the stability of MOFs, while carbonization treatments may lead to a reduction in specific surface area, thus decreasing catalytic activit14. In contrast, TEMPO (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxide) possesses a unique stable free radical feature, which can effectively enhance the electron transport capacity of MOFs and impart redox activity to the materials. Previous studies have further revealed that the N–O radical structure of TEMPO can act as an electron mediator during electrocatalysis, accelerating charge transfer and thereby significantly enhancing catalytic activity15. Meanwhile, its steric hindrance effect and stable radical characteristics provide a buffering protection for metal active sites, effectively suppressing overoxidation and framework degradation, thus improving the long-term stability of the material16. However, there is limited research on the electronic structure regulation and catalytic mechanism of TEMPO-modified MOFs, and the role of TEMPO in MOF catalysis has not been fully revealed. Meanwhile, considering the variations in conductivity and medium stability among different MOFs, Ni-MOF has emerged as a promising framework due to its excellent structural stability in alkaline media and the rich redox characteristics of Ni active sites17. Compared to commonly used frameworks such as Fe-MOF and Co-MOF, Ni-MOF demonstrates superior performance in terms of electron transport efficiency, framework durability, and compatibility with functional modifications, making it particularly well-suited for constructing oxidation-type electrocatalytic systems18,19. To bridge this research gap, we developed a TEMPO-functionalized Ni-MOF derived from conventional Ni-MOF to amplify its electrocatalytic properties. Through strategic structural engineering, the TEMPO units combine cooperatively with the MOF matrix, significantly boosting both charge transfer kinetics and catalytic performance. Our findings demonstrate the superior activity of Ni-TEMPO-MOF in electrocatalytic oxidations, offering an innovative strategy for MOF modification in electrocatalysis while establishing crucial theoretical frameworks and experimental support for designing high-performance, durable electrocatalysts. This work substantially advances MOF applications in energy conversion and catalytic chemistry.

Research design

Material preparation

Copper foam (CF) was sectioned into 2×2 cm2 pieces. These pieces underwent ultrasonic cleaning in acetone, absolute ethanol, and deionized water for 8-12 minutes each to eliminate surface contaminants. Subsequently, the cleaned CF was etched in a 4 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution for 20-30 minutes to remove the oxide layer and increase surface reactivity. The resulting substrate was thoroughly washed with deionized water until a neutral pH was achieved and then dried using a stream of nitrogen gas prior to subsequent applications.

In an appropriately proportioned mixed solvent system (DMF 3 mL, EtOH 1 mL, and H₂O 1 mL), 14.3 mg of NiCl₂·6H₂O (0.06 mmol) and 10.3 mg of the organic ligand H₂tpdc-TEMPO (0.02 mmol) were dissolved, and a homogeneous precursor solution was obtained using a combination of ultrasonic-assisted premixing and magnetic stirring. To ensure uniform dispersion of the active components within the reaction system, the reactants were mixed via controlled constant-rate dropwise addition, thereby improving the homogeneity of the dispersed phase in solution and preventing agglomeration. The resulting solution was transferred to a stainless-steel high-pressure reactor with a PTFE liner, with the pretreated CF substrate vertically suspended and fully immersed in the reaction solution. The system was then placed in a constant temperature environment at 125°C for a hydrothermal reaction lasting 6-10 hours. After the reaction was completed, the system was naturally cooled to room temperature, the CF substrate was removed, and gently washed with deionized water to remove any unbound by-products on the surface. Finally, the obtained sample was vacuum-dried at 60°C for 6 hours, resulting in the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF composite material.

The Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF electrode fabricated under these conditions possessed an effective surface area of 4.0 cm2. Based on gravimetric measurements, the Ni-TEMPO-MOF loading was estimated to be 0.58 ± 0.03 mg per cm2, yielding a total mass loading of 2.32 ± 0.12 mg. The composite was synthesized via in situ deposition on the copper foam support. Characterization samples were prepared using different strategies depending on technical requirements. For methods tolerant to the substrate (e.g., SEM, XRD, and electrochemical characterization), the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF was tested intact. In cases where substrate interference was a concern (e.g., XPS, FTIR, TEM), the material was gently exfoliated by immersing the electrode in deionized water and applying low-intensity ultrasound for 3–5 minutes. The dispersed solid was retrieved and dried under vacuum at 60°C to produce pure Ni-TEMPO-MOF powder for analysis.

Structural characterization of materials

To comprehensively analyze the structural characteristics of the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF, several characterization techniques were employed to reveal its crystal structure, surface morphology, functional group composition, elemental valence states, and thermal stability. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to examine the crystal structure of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF and confirm its crystallinity and phase purity. The XRD measurements were performed using a Rigaku SmartLab 9 kW diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 40 kV and 40 mA, with a scanning range of 2θ = 5°–80°, step size of 0.02°, and a scan rate of 5°/min. In addition to comparing the diffraction peak positions and intensity variations between Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF and unmodified Ni-MOF, full width at half maximum (FWHM) fitting was performed for the main diffraction peaks. The average crystallite size was calculated using the Scherrer equation, and the Williamson–Hall method was applied to linearly fit the peak broadening to evaluate the microstrain of the lattice, thereby obtaining more comprehensive crystallographic parameters. FTIR spectroscopy, performed with a Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer, was used to identify the impact of TEMPO modification on the functional group structure of Ni-MOF, with a focus on characteristic absorption peaks of C=O, C–N, and N–O groups.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to observe the surface morphology and particle distribution of the material. SEM was conducted on a Hitachi SU8020 cold field emission SEM at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV, with the samples coated with an Au/Pd sputter for improved conductivity. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), coupled with high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), was used to further analyze the microstructure of the materials. These experiments were carried out using a JEOL JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. TEM was used to examine the pore structure of the MOF, and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) was employed to confirm the crystallographic orientation of the material. Additionally, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping was used to analyze the distribution of elements such as Ni, O, and N to ensure uniform TEMPO modification within the MOF framework.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was utilized to analyze the changes in the valence states of Ni, O, N, and other elements before and after modification, as well as to assess the effect of TEMPO modification on the electronic structure of Ni-MOF. XPS measurements were performed with a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha XPS instrument, using Al Kα X-ray (hv = 1486.6 eV), with a vacuum pressure of <10⁻⁷ mbar, and an X-ray spot size of 400 μm. Ni 2p, O 1s, and N 1s spectra were used to analyze the electronic environment changes in the modified Ni-MOF. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted to study the thermal stability of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF, evaluating the decomposition behavior of the materials and the desorption of TEMPO molecules at different temperatures. TGA was performed using a NETZSCH STA 449F3 thermogravimetric analyzer, with a heating rate of 10°C/min in a nitrogen atmosphere, within the temperature range of 30–800°C.

Electrochemical characterization

To investigate the electrocatalytic performance of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF, various electrochemical characterization methods, including cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and chronoamperometry (CA), were employed to analyze the material’s redox behavior, electrocatalytic activity, stability, and conductivity. All electrochemical tests were carried out using a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai CH Instruments Co., Ltd.) in a three-electrode system, with Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl (3.5 M KCl) reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode. The electrolyte used was 0.1 M KOH, and the tests were conducted at 25°C. All electrochemical measurements were performed on independently synthesized samples from multiple batches and repeated at least three times under identical conditions to ensure experimental reproducibility and data reliability.

(1) CV Measurement of Redox Behavior

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was used to study the redox characteristics of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF. The scan range was set from −0.2 V to 0.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), and the scan rates ranged from 10 to 100 mV/s. The variation in the oxidation and reduction peak currents was analyzed at different scan rates, and the electron transfer rate constant (k₀) was calculated. By comparing the CV curves of TEMPO-modified and unmodified Ni-MOF, the impact of TEMPO on the electron transport capability of Ni-MOF was assessed.

(2) LSV Analysis of Electrocatalytic Performance

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was used to analyze the electrocatalytic activity of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF for the target catalytic reaction. The scan rate was 5 mV/s, and the potential range was from −0.2 V to 1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). The polarization curves were recorded, and key parameters such as the onset potential (Eonset), Tafel slope, and exchange current density (j₀) were calculated. The LSV curves of TEMPO-Ni-MOF and unmodified Ni-MOF were compared to evaluate the enhancement in electrocatalytic activity by TEMPO.

(3) EIS Analysis of Charge Transfer Ability

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was employed to study the charge transfer ability and interface resistance of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF. EIS measurements were conducted over a frequency range of 10⁻2–105 Hz with a perturbation amplitude of 5 mV, and the measurements were taken at open circuit potential.

(4) CA Test for Catalytic Stability

Chronoamperometry (CA) was used to test the stability of the electrocatalysts by applying a fixed potential of 0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) and recording the current variation over time for 3600 seconds. The current decay of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF was monitored to analyze its catalytic stability, and the results were compared to unmodified Ni-MOF to assess whether the introduction of TEMPO improved the long-term stability of Ni-MOF.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of Ni-MOF

Microstructure and morphological features

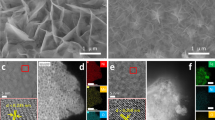

To examine the influence of TEMPO functionalization on the microstructure of Ni-MOF, a comparative analysis of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 1a displays the SEM image of Ni-MOF, showing irregular bulk particles approximately 1–2 μm in diameter grown on the copper foam (CF) substrate. These particles possess indistinct boundaries and display random aggregation, suggesting insufficient self-organization under hydrothermal synthesis conditions. The corresponding TEM image (Fig. 1b) reveals a loosely packed, disordered internal morphology with no clear lattice fringes, indicating low crystallinity and poor structural ordering. Figure 1c exhibits the unmodified CF substrate, which presents a characteristic 3D porous metallic network with thick pore walls and a generally coarse surface without distinct layered features. The TEM image of CF (Fig. 1d) further confirms a dense and irregular metal phase with absence of lattice fringes or ordered lamellar structures.

In contrast, the SEM image of Ni-TEMPO-MOF (Fig. 1e) displays a distinctly different morphology, showing a uniformly distributed nanoflower-like architecture formed by the interlaced stacking of sheet-like nanolayers. Each nanosheet is approximately several tens of nanometers thick, constructing a three-dimensional open lamellar system. This structure significantly enhances the specific surface area and electrolyte infiltration pathways, thereby increasing the number of accessible catalytic active sites. Additionally, the SEM image shows well-defined particle boundaries with a relatively narrow size distribution and no visible aggregation or heterogeneity, indicating good dispersion during synthesis. The high-resolution TEM image (Fig. 1f) reveals clearly defined and orderly lattice fringes within the nanosheets, reflecting high crystallinity and well-aligned crystal planes. Multiregion image analysis confirms the uniformity of particle morphology. Such a microstructure—with uniform size distribution and excellent dispersibility—facilitates continuous electron transport and improves the stability of the catalyst–electrolyte interface, ultimately enhancing the electrocatalytic performance of the electrode. These observations confirm that the layered and nanocrystalline features observed in Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF are indeed attributed to MOF deposition, rather than arising from the inherent morphology of the copper foam substrate. This comparative analysis provides strong evidence that the formation of ordered lamellar structures and improved crystallinity in Ni-TEMPO-MOF is a result of TEMPO modification, while also excluding the possibility that morphological changes stem from the substrate, thereby reinforcing the credibility of the structural interpretation.

Structural morphology plays a crucial role in electrocatalytic performance. In the case of Ni-MOF, the presence of aggregated and disordered particles restricts charge transport pathways during catalysis, hindering efficient electron migration within the framework. In contrast, the well-aligned layered structure of Ni-TEMPO-MOF offers a larger interfacial reaction area and open interlayer channels that facilitate ion diffusion and rapid electron transfer. Previous studies have shown that two-dimensional layered MOF structures can reduce charge transfer resistance at the nanoscale by providing continuous π–π stacking pathways or metal–ligand conductive networks, thereby enhancing electrocatalytic kinetics20,21. Therefore, the observed features of ordered nanosheet assembly and crystalline plane orientation in Ni-TEMPO-MOF form the structural foundation for its superior charge transport capability compared to Ni-MOF and provide critical support for the enhancement of its catalytic performance.

In summary, Ni-TEMPO-MOF exhibits high consistency in both morphology and crystallinity, indicating that the adopted synthesis method possesses excellent controllability and product uniformity. Based on the structural characterization results, it can be inferred that the two-step hydrothermal method employed in this study demonstrates good process stability. Repeated synthesis under varying batches yielded products with no significant differences in morphology, crystallinity, or porosity, highlighting strong reproducibility. Furthermore, the broad parameter windows of this synthesis route suggest robust process tolerance, providing a feasible foundation for future scale-up or industrial applications.

To further verify the elemental composition and distribution of the materials, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and elemental mapping analyses were conducted on Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF samples in combination with SEM/TEM measurements, as shown in Fig. 2. The EDS spectra indicate that both samples are mainly composed of Ni, O, N, and C elements, with no other impurity elements detected, confirming the high purity of the materials. Compared with Ni-MOF, the Ni-TEMPO-MOF sample exhibits more pronounced N and O signals, which is consistent with the successful introduction of TEMPO groups. The elemental mapping results further demonstrate that all elements are uniformly distributed across the particle surfaces without obvious aggregation or local enrichment. In particular, Ni shows a homogeneous dispersion, indicating the stability of the metal centers, while the uniform distribution of C, N, and O confirms the effective modification of the organic ligands and TEMPO groups.

Structural and chemical composition analysis

To further verify the effect of TEMPO modification on the crystal structure of Ni-MOF, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted for both Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF samples, with the results shown in Fig. 3 Ni-MOF exhibits distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 7.1°, 14.2°, 21.4°, 27.3°, and 50.2°, corresponding to the (100), (110), (210), (300), and (440) crystal planes, respectively. These peaks align well with the standard JCPDS card #15-0806, indicating that the material possesses good crystallinity and characteristic MOF lattice features. In comparison, the XRD pattern of Ni-TEMPO-MOF also displays the main diffraction peaks at the corresponding positions, but the peaks are slightly shifted toward higher angles (e.g., the (100) plane shifts from 7.1° to 7.3°), with broader peak widths and reduced intensities. This variation suggests that TEMPO modification introduces local lattice distortion without disrupting the primary MOF framework. The peak shift may be attributed to the introduction of TEMPO groups, which altered the metal coordination environment and induced a reduction in interplanar spacing, thereby leading to a rightward shift of the XRD peaks. Meanwhile, the increased peak width and decreased intensity reflect a reduction in crystallinity and a weakening of structural order.

In this study, full width at half maximum (FWHM) fitting was performed for the main diffraction peaks. Based on the Scherrer equation, the average crystallite size of Ni-MOF was calculated to be approximately 32.6 nm, whereas that of Ni-TEMPO-MOF decreased to 25.4 nm, indicating that TEMPO modification suppressed excessive grain growth and reduced crystallinity. Meanwhile, linear fitting of peak broadening using the Williamson–Hall method yielded an average lattice strain of 0.21% for Ni-MOF, which increased to 0.34% for Ni-TEMPO-MOF, suggesting that the introduction of TEMPO groups induced stronger microstrain within the framework. These structural features not only reveal the crystallographic changes in Ni-TEMPO-MOF but also provide an important basis for understanding its enhanced electrocatalytic performance. The reduction in crystallite size favors the exposure of more electrochemically active sites and shortens the diffusion pathways for electrons and ions within the crystal, while the increase in lattice strain introduces more defects and tension into the framework, thereby improving electron localization and charge transfer efficiency.

In addition, to eliminate potential interference from the copper foam (CF) substrate in the XRD results, a control sample of pristine CF was analyzed. Its diffraction pattern shows characteristic peaks at approximately 2θ = 43.3°, 50.4°, and 74.1°, corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes, which are consistent with the face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of copper as listed in JCPDS card #04-0836. Compared with the major diffraction peaks of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF, the characteristic peaks of pure CF are clearly distinguishable and show no significant overlap.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) of Ni-TEMPO-MOF reveals the functional group composition and modification effects. By comparing the absorption peaks at different wavenumbers, the successful introduction of TEMPO and its effect on the MOF structure can be analyzed. As shown in Fig. 4, the FTIR spectrum of Ni-TEMPO-MOF displays a broad peak at 3430 cm⁻1, corresponding to O-H or N-H stretching vibrations, which may arise from residual water or hydroxyl groups22. The peak at 1720 cm⁻1 corresponds to C=O stretching vibrations, indicating the successful attachment of the TEMPO group to the surface of Ni-MOF. The characteristic absorption peaks at 1380 cm⁻1 and 1250 cm⁻1 correspond to C-N/C-O and N-O bonds, further confirming the presence of TEMPO groups23. The N-O peak is particularly significant, showing that TEMPO is coordinatively bound to the MOF framework. Additionally, a Ni-O absorption peak is detected at 500 cm⁻1, indicating that the modification process does not disrupt the Ni center of the MOF but rather modifies its surface chemistry24. These structural changes could influence the electronic environment of the Ni centers, providing a structural basis for the subsequent enhancement of catalytic performance.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis further revealed the elemental composition and electronic structure differences between Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF, with the results shown in Fig. 5 In the survey spectra, Ni-TEMPO-MOF exhibits significantly enhanced signal responses in all major binding energy regions, confirming the successful incorporation of TEMPO groups and highlighting their regulatory effect on the electronic environment of Ni-MOF. In the Ni 2p region (850–860 eV), a characteristic doublet is observed, with the main binding energy of Ni-TEMPO-MOF slightly shifting from 855.6 eV (in Ni-MOF) to 855.1 eV. This negative shift suggests a change in the electron cloud density around the Ni2⁺ centers after TEMPO modification, likely due to the electron-donating effect of the N–O radical moiety. This binding energy shift is consistent with previous reports, indicating that the modification does not disrupt the Ni coordination center but rather tunes its local coordination environment25. At 530 eV, the O 1s signal intensity is markedly increased, which is attributed to the combined contributions of Ni–O coordination, carboxyl groups in the MOF framework, and N–O functionalities from TEMPO. Similarly, the N 1s signal at 400 eV is enhanced after TEMPO modification, further indicating that the introduction of the nitrogen-containing radical group increases the electronic density distribution of nitrogen species within the framework26. In contrast, the C 1s region (285 eV) shows similar spectral profiles and intensities for both samples, suggesting that the carbon backbone of the MOF remains largely unaltered upon TEMPO grafting. Taken together, these results confirm that the TEMPO groups effectively modulate the electronic structure of Ni-MOF at the molecular level through electronic interactions, thereby providing a structural and theoretical basis for the subsequent enhancement of electrocatalytic activity.

To verify the elemental composition and surface modification effectiveness of Ni-TEMPO-MOF, this study compared the atomic percentages obtained from XPS survey spectra—corrected using relative sensitivity factors (RSF)—with the results from EDS elemental analysis (Table 1). The findings reveal that while the elemental distribution trends obtained by both methods are generally consistent, certain numerical discrepancies are observed. Specifically, the proportions of C (46.73%) and N (6.85%) detected by XPS are relatively higher, which is closely related to the surface-sensitive nature of XPS (probing depth of approximately 5–10 nm), indicating a high surface coverage of TEMPO organic groups and further confirming the success and uniformity of the surface modification. In contrast, the EDS results show slightly higher contents of Ni (33.67%) and O (28.67%), primarily because EDS reflects the bulk composition of the material and may include contributions from the oxidized layer of the copper foam substrate. Overall, the XPS and EDS results are mutually supportive, demonstrating a uniform elemental distribution within the Ni-TEMPO-MOF material. The effective incorporation of TEMPO on the MOF surface was successfully achieved while maintaining chemical consistency throughout the structure.

To further verify whether TEMPO modification affects the specific surface area and pore structure of the material, nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm tests were conducted on both Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF samples, and the specific surface areas were calculated based on the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model. As shown in Fig. 6, the isotherm of the Ni-MOF sample exhibits a typical type II adsorption behavior with a surface area of 118.6 m2/g, primarily consisting of non-porous and microporous structures. In contrast, the isotherm of the Ni-TEMPO-MOF sample more closely resembles a type IV profile, displaying a pronounced hysteresis loop, with the surface area increasing to 193.2 m2/g and a mesoporous distribution concentrated in the 3–10 nm range. These results indicate that the introduction of TEMPO groups not only regulates the local crystal structure but also improves the pore architecture and surface area of the MOF material at the macroscopic scale. The significant increase in surface area implies a greater number of accessible active sites for electrolyte interaction, thereby enhancing charge transfer efficiency and catalytic activity. This structural enhancement provides a mechanistic explanation for the superior performance of Ni-TEMPO-MOF in electrocatalytic oxidation reactions.

Figure 7 presents the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves of Ni-MOF and Ni-TEMPO-MOF. The Ni-MOF sample undergoes its main weight loss between 229.1 °C and 430 °C, with the residual mass dropping sharply from approximately 99.22% to 61.3%, and stabilizing at 60.00% at 800 °C, indicating partial decomposition of the structure at elevated temperatures. In contrast, Ni-TEMPO-MOF exhibits a distinct two-stage weight loss behavior: the first stage occurs between 229.1 °C and 326.4 °C with a gradual mass reduction to 90.35%, attributed to the decomposition and desorption of the TEMPO free radicals; the second stage involves a rapid weight loss from 326.4 °C to 459 °C , with the residual mass stabilizing at 55.00% by 800 °C . This trend suggests that while TEMPO modification introduces an additional pyrolysis process, the overall thermal stability of Ni-TEMPO-MOF remains acceptable and meets the thermal requirements of electrocatalytic environments. Considering that alkaline electrocatalytic oxidation typically occurs within the temperature range of room temperature to 80 °C, the Ni-TEMPO-MOF constructed in this study exhibits good structural stability within this range, which is well below its thermal decomposition onset temperature. This indicates that the material fully meets the thermal requirements of electrocatalytic reactions.

Analysis of alcohol oxidation performance

Figure 8(a) compares the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF and Ni-MOF at the same scan rate of 50 mV/s. The oxidation peak of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF appears at 0.46 V with a peak current density of 3.94 mA/cm2, which is significantly higher than that of Ni-MOF (2.68 mA/cm2), and the peak potential is negatively shifted by 0.05 V. This indicates a faster electron transfer process and more favorable reaction kinetics, suggesting that TEMPO modification enhances the electron affinity of the Ni centers and effectively promotes substrate oxidation. It is worth noting that the CV curves exhibit crossover behavior within certain potential regions—an occurrence commonly observed in Ni-based MOFs and their derivatives. This phenomenon typically arises from kinetic differences in the Ni2⁺/Ni3⁺ redox transitions during the forward and reverse scans, resulting in current response hysteresis. Additionally, the adsorption and desorption of interfacial OH⁻ species do not proceed simultaneously, which can lead to a stronger current response during the reverse scan compared to the forward scan. Moreover, some reaction intermediates may undergo reversible adsorption on the electrode surface and re-engage in electron transfer during the reverse sweep, further contributing to the crossover. In the case of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF, the introduction of TEMPO groups modifies the electronic environment of the Ni centers, and the radical structure can act as an electron mediator during redox processes. This characteristic amplifies the combined effects of valence-state transitions and interfacial phenomena. Therefore, the observed curve crossover is not an experimental artifact, but rather a reflection of the complex interplay between multivalent transformations and interfacial processes during the electrode reaction.

Furthermore, to confirm the diffusion-controlled nature of the electrocatalytic process, Fig. 8(b) shows the CV responses of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF at various scan rates ranging from 10 to 100 mV/s. As the scan rate increases, the oxidation peak current increases continuously without significant peak shifts, indicating that the system follows a classical diffusion-controlled model. This behavior demonstrates that the introduction of TEMPO groups not only optimizes the electronic structure of the catalyst but also improves interfacial charge transfer efficiency and electrochemical response rate. In addition, the fitting results show a strong linear relationship between the oxidation peak current and the square root of the scan rate (R2 = 0.998), further confirming that the redox process of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF is governed by diffusion and exhibits stable and reproducible electrochemical behavior. The above results represent a typical outcome from multiple experimental batches, with repeated measurements consistently exhibiting the same electrochemical trends, thereby ensuring the reliability of the conclusions.

The study employed an electrolyte of 0.1 M KOH with glycerol, using a scan rate of 5 mV/s and a potential range set from 0 to 0.8 V. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) tests were carried out in a three-electrode system, and the potential corresponding to a current density of 0.1 mA/cm2 was defined as the onset potential. As shown in Fig. 9(a), Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF exhibited higher current densities across the entire potential window, with a sharp increase above 0.6 V, indicating that its catalytic activity is significantly superior to that of unmodified Ni-MOF. The onset potential of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF is 0.27 V, which is 0.04 V lower than that of Ni-MOF (0.31 V), suggesting that the oxidation reaction can be initiated at a lower overpotential. This not only reflects the catalyst’s enhanced electronic activation capability toward the substrate but also demonstrates optimization of its electronic structure. The introduction of TEMPO alters the local electronic environment of the Ni centers. The N–O radical structure of TEMPO possesses a highly stable single-electron orbital that can engage in π*–eg orbital coupling with the Ni2⁺ center’s eg orbitals (e.g., d(x2−y2)) during the electrocatalytic process. This orbital interaction induces electronic state redistribution, reducing the electron density at the Ni sites and facilitating coordination and adsorption with the substrate (e.g., hydroxyl groups in glycerol). More importantly, TEMPO undergoes rapid redox cycling between its TEMPO/TEMPO⁺ couple and acts as an “electron mediator” during the reaction, channeling electrons from the electrode to the Ni center. This mechanism significantly reduces interfacial electron transfer resistance and accelerates the reaction rate. Figure 9(b) shows that the Tafel slope of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF is 86.6 mV/dec, a substantial decrease compared to 154.2 mV/dec for Ni-MOF, indicating a more efficient electron transfer step during the catalytic process. This reduction in slope can be attributed to the formation of a radical-assisted electron transfer pathway: the stable N–O π-system in the TEMPO structure facilitates lower-barrier intramolecular electron migration. Simultaneously, the surface of the TEMPO-modified Ni-MOF exhibits a more ordered charge distribution, reducing local electric field inhomogeneity caused by electron accumulation, thereby improving overall catalytic kinetics. Notably, this Tafel slope is superior to that of the Ni-based oxidation catalyst (~92 mV/dec) reported by Zhao et al.27, and also lower than that of the Ni/Co-MOF-derived material (119 mV/dec) developed by Yu et al.28, indicating that the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF system constructed in this study demonstrates more favorable electrocatalytic oxidation kinetics under alkaline conditions. Furthermore, the onset potential of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF (0.27 V vs. Ag/AgCl) is lower than that of the TEMPO-polymer-based system (~0.35 V) reported by Mohamad et al.29, suggesting that this catalyst activates the reaction at a lower overpotential and exhibits stronger electron affinity and oxidation activation capability.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were repeatedly conducted on multiple batches of samples. As shown in Fig. 10(a), the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF was measured to be 0.13 Ω, significantly lower than that of unmodified Ni-MOF (0.32 Ω), corresponding to a reduction of approximately 60%. This substantial decrease reflects an optimized electron transfer pathway at the electrode–electrolyte interface. The incorporation of TEMPO not only improves surface conductivity but also leverages the intrinsic electron affinity of its N–O radical structure to facilitate rapid electron migration between active sites. Additionally, the reversible charge-exchange behavior of TEMPO stabilizes the oxidation state of the Ni centers, mitigating the formation of electron traps due to local charge accumulation. This "soft-coupling electron bridge" mechanism enables high-speed electron transfer between the MOF framework and catalytic centers, enhancing charge utilization efficiency. Moreover, TEMPO modification may also influence the interfacial double-layer structure between the Ni-MOF and electrolyte, reducing interfacial capacitance impedance and promoting ion diffusion at the electrode surface, thereby improving ion migration kinetics during the electrocatalytic reaction. These results indicate that Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF not only optimizes the electronic conduction pathway but also facilitates rapid ion exchange and synergistic interactions at the catalytic interface, thereby further improving the overall catalytic kinetics. Figure 10 (b) presents the equivalent circuit model used for EIS data fitting, which includes four components: Rs (solution resistance), Rct (charge transfer resistance), Cdl (double-layer capacitance), and Zw (Warburg diffusion impedance). This model adequately reflects electron transport behavior, interfacial capacitive effects, and diffusion processes within the system. Nonlinear fitting of the Nyquist plots using ZView software yielded a fitting error below 5%, demonstrating the model’s high accuracy in quantitatively analyzing charge transport behavior. These findings confirm that Ni-TEMPO-MOF effectively enhances both electronic and ionic transport pathways, contributing to improved catalytic kinetics through strengthened charge–ion synergism at the reaction interface.

The chronoamperometry (CA) test shown in Fig. 11 further verifies the stability of the catalyst. A fixed potential of 0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) was applied during the test, corresponding to the potential range where the catalytic current of Ni-TEMPO-MOF rises sharply in the LSV curve, representing a typical operating condition under moderate overpotential. This potential was chosen to evaluate the long-term operational stability of the catalyst under realistic reaction conditions without inducing structural degradation. At this potential, the initial current density of Ni-TEMPO-MOF was 3.2 mA/cm2, which decreased to 1.6 mA/cm2 after 3600 seconds, corresponding to a decay rate of 50%. In comparison, Ni-MOF showed a greater decline from 2.5 mA/cm2 to 0.8 mA/cm2, with a decay rate of 68%. Although the overall current density values appear relatively low, this is closely related to the experimental conditions. On one hand, a moderate applied potential was deliberately chosen to realistically reflect the long-term operational performance of the catalyst rather than its peak response. On the other hand, the effective reaction area of the copper foam substrate was limited to 4.0 cm2, and the catalyst loading was controlled at 0.58 mg/cm2, resulting in a relatively small amount of active material, which also constrained the absolute current density. The observed current decay over time is primarily attributed to the progressive oxidation of Ni2⁺ to Ni3⁺ under alkaline conditions and the accumulation of gas bubbles on the electrode surface, both of which reduce the effective active area and accelerate performance degradation. During this process, the TEMPO modification played a buffering role: the radical structure facilitated reversible electron transfer that mitigated the overoxidation of Ni active sites, while its steric hindrance suppressed the aggregation of surface species. As a result, Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF exhibited a higher current retention and a lower decay rate compared to unmodified Ni-MOF. To eliminate random errors and ensure the reliability of the results, multiple batches of samples were tested under identical conditions, and the resulting current decay curves showed consistent trends and comparable magnitudes of attenuation.

To further validate the electrocatalytic stability advantage of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF in alcohol oxidation reactions, a comparative performance analysis was conducted using representative MOF-based materials and commercial Pt/C catalysts (and their derivatives) reported in recent literature, with a particular focus on their current retention capability under chronoamperometric testing conditions. As shown in Table 2, after 3600 seconds of testing in 0.1 M KOH containing glycerol, Ni-TEMPO-MOF maintained 50.0% of its initial current density, which is significantly higher than that of most comparable materials. For example, V-doped Ni-BTC MOF exhibited only ~40% retention under alkaline conditions during glycerol oxidation30, while coral-like Co-MOF/C electrodes showed a further reduced retention rate of 35.7% (Amini et al., 2022). Additionally, although a Co-MOF-modified glassy carbon electrode demonstrated relatively good short-term stability in PBS buffer, the total test duration was limited to around 2000 seconds, with a retention rate of less than 10%31. Commercial Pt/C also exhibits limited stability in glycerol oxidation, with an initial current density exceeding 200 mA/cm2, but retaining only about 50% after 3 hours of operation32. This retention level is comparable to the performance of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF in a 1-hour test,however, Pt/C suffers from pronounced rapid deactivation during the early stages, whereas Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF maintains a more stable current response over the same duration. This highlights the advantage of the TEMPO modification strategy in enhancing the long-term stability of MOF-based catalysts. Similarly, Pt/C derivatives also show limited durability under alkaline conditions: Pt/C–Al₂O₃ retains only 35% of its current density after 1 hour in 1 M NaOH + 1 M glycerol33, and Pt/C–Zeolite shows a retention of approximately 45% under 1 M KOH + 1 M glycerol34, both of which are markedly inferior to the stability performance of Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF. These results indicate that TEMPO radical modification not only effectively enhances the initial electrocatalytic activity of Ni-MOF but also plays a critical role in suppressing structural degradation and improving electron transfer efficiency. As a result, the material exhibits excellent current retention and long-term operational stability.

To further investigate the electrocatalytic response of the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF electrode under varying operational current densities, Fig. 12 presents the LSV curves at applied current densities of 1, 2, 5, and 10 mA/cm2. As shown in the figure, the polarization potential exhibits a systematic positive shift with increasing current density, indicating that the system maintains stable catalytic response even under high-rate conditions. This result reflects the excellent rate capability of the Ni-TEMPO-MOF/CF electrode material, demonstrating its ability to retain high electrochemical activity across different loading conditions and highlighting its adaptability and practical potential in multi-scenario applications. Furthermore, the response curvature across different current densities remains relatively consistent, suggesting a stable charge transfer process without significant kinetic hysteresis, thereby further confirming the material’s structural stability and interfacial reaction efficiency.

Post-electrolysis structural stability analysis

To further verify the structural stability of Ni-TEMPO-MOF during the electrocatalytic process, morphology and crystal structure analyses were performed on the catalyst after completion of the CA test (3600 s). As shown in Fig 13(a), the post-electrolysis SEM image reveals that Ni-TEMPO-MOF retains its initial flower-like nanostructure. The stacked nanosheet morphology remains well-defined, with no evident collapse or aggregation, indicating good structural retention under alkaline electrolytic conditions. Fig. 13(b) presents the corresponding TEM image, showing that clear lattice fringes are still present on the catalyst surface, with an interplanar spacing of approximately 0.20 nm. No signs of lattice disorder or diffuse structural degradation were observed, suggesting that the material maintains good crystallinity even after electrochemical operation. These findings are consistent with the electrocatalytic stability results discussed earlier, further confirming that Ni-TEMPO-MOF exhibits strong structural and electrochemical stability, making it well-suited for long-term electrocatalytic oxidation applications.

To verify the structural stability of Ni-TEMPO-MOF after prolonged electrocatalytic operation, XRD characterization was performed on the sample following the cycling test. As shown in Fig. 14, the post-electrolysis diffraction pattern retains the main characteristic peak positions similar to those of the original sample, with only slight shifts observed. No new diffraction peaks or significant intensity reductions were detected, indicating that the crystalline structure remained stable during the electrocatalytic process, with no notable structural reconstruction or phase transformation.

Discussion

This study successfully synthesized TEMPO-modified Ni-MOF (Ni-TEMPO-MOF) composite materials and systematically explored their performance in electrocatalytic alcohol oxidation reactions. The experimental results indicate that the introduction of TEMPO not only preserved the framework structure of Ni-MOF but also significantly optimized its electron transfer capacity, enhanced charge transfer rates, and reduced the energy barrier for oxidation reactions. This, in turn, improved both catalytic activity and stability. Compared to unmodified Ni-MOF, Ni-TEMPO-MOF exhibited a negative shift in oxidation potential, a substantial increase in oxidation-reduction peak currents, a nearly 60% reduction in charge transfer impedance, and better stability during long-term electrocatalytic testing.

In comparison with existing research on MOFs in electrocatalysis, the methods and conclusions of this study are consistent with some previous works in theory, providing further experimental support for the electronic structure modulation of MOFs. However, it also shows new breakthroughs in material design and catalytic mechanisms. From the perspective of electronic structure optimization, Dai et al.36 studied the application of transition metal-doped MOFs in electrocatalysis and found that the introduction of metal elements such as Fe or Co can effectively modulate the electronic structure of MOFs, thereby enhancing their catalytic activity. However, this strategy depends on metal-metal interactions, which may lead to instability in the MOF framework. The TEMPO modification strategy in this study aligns with their findings, but it innovatively employs a non-metallic functional group (TEMPO radical) for electronic modulation, avoiding the structural instability issues caused by multi-metal systems and offering a milder, more precise method for functionalizing MOFs. Regarding strategies to improve the conductivity of MOFs, Wang et al.37, used a carbonization method to convert MOFs into MOF-derived carbon materials, improving their electrical conductivity and enhancing catalytic activity. While this method has a significant advantage in terms of conductivity, the high-temperature carbonization process can destroy the pore structure of MOFs, leading to a reduction in specific surface area and affecting the utilization of catalytic active sites. In contrast, the innovation in this study lies in optimizing the electron transfer process without damaging the pore structure of MOFs. TEMPO’s redox activity provides an electron transfer channel at the molecular level, lowering charge transfer impedance and improving catalytic efficiency. From the perspective of post-modification strategies, Yan et al.38 investigated the method of modifying MOFs with organic small molecules, where nitrogen-doped conjugated organic groups were grafted onto the surface of MOFs to improve their electron transfer capability in redox reactions. This study shares a similar research direction, utilizing organic group modification of MOFs to optimize their catalytic performance. However, the key difference is that this study directly introduced TEMPO groups during the synthesis process rather than using a post-modification strategy, ensuring uniform distribution of TEMPO and avoiding potential issues of structural inhomogeneity or limited functional group coverage during post-modification, thus enhancing catalyst stability.

Theoretically, this work broadens the investigation of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) within electrocatalysis by demonstrating the pivotal function of TEMPO groups in modulating the electronic configuration and catalytic performance of MOFs. By strategically modifying organic functional groups, it is possible to improve the electrical conductivity of MOFs, optimize reaction pathways, and consequently enhance catalytic efficiency. Although the approach of radical-based modification using TEMPO is introduced here, several limitations remain. Firstly, although TEMPO functionalization successfully tunes the electronic properties of the MOF, its durability across diverse electrolyte systems has not been thoroughly examined, which may influence the catalyst’s long-term stability. Secondly, the study is mainly confined to Ni-MOF, leaving the extension of this modification strategy to other MOF architectures or metal nodes unexplored; thus, the general applicability demands further validation. Moreover, while the involvement of TEMPO in electron transfer during electrocatalysis is illustrated, the precise electron transport routes and the dynamic evolution of radical species throughout the catalytic process necessitate deeper exploration via advanced theoretical simulations and in situ spectroscopic techniques.

Conclusion

This research involved the design and synthesis of a Ni-TEMPO-MOF composite with a radical-functionalized architecture, followed by a comprehensive assessment of its electrocatalytic behavior in alcohol oxidation under alkaline media. The findings revealed that TEMPO functionalization markedly improved both the activity and durability of the Ni-MOF catalyst: a 47.0% rise in oxidation peak current density, a 0.04 V reduction in onset potential, a Tafel slope lowered to 86.6 mV/dec, a nearly 60% decline in charge transfer resistance, and a 50% current retention after 3600 s in chronoamperometry tests—significantly higher than the 32% shown by the pure Ni-MOF. These gains are ascribed to the role of TEMPO in constructing nanoscale electron-hopping pathways and reducing oxidative degradation of Ni active centers, leading to simultaneous enhancement of charge transfer and mechanical integrity. The outcomes confirm the viability and advantage of radical modification tactics in upgrading the electrocatalytic properties of MOF catalysts, providing substantial theoretical value and attractive application prospects.

Further investigations could develop in the following directions. First, factors such as electrolyte pH, ion concentration, and solvent type may alter the chemical robustness and electron shuttle capability of TEMPO units. Therefore, applying in situ spectral methods, long-term cycling tests, and DFT-based computations would allow a thorough assessment of TEMPO’s durability under diverse conditions and its role in governing overall catalytic conductivity and activity. Second, adapting the TEMPO modification method to additional MOF systems—for example, Co- or Fe-MOFs—would help generalize the strategy. Combining empirical studies with theoretical work could illuminate how the metal center affects TEMPO’s electron regulation behavior, thereby expanding the scope and utility of this approach. Third, employing advanced real-time techniques like in situ XAS, EPR, and transient spectroscopy, along with simulated electron transfer routes, could enable precise tracking of radical species’ transformation during electrocatalysis. This would contribute to a more fundamental understanding of the reaction mechanisms in TEMPO-integrated MOF catalysts.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Dutt, S., Kumar, A. & Singh, S. Synthesis of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) and their derived materials for energy storage applications. Clean Technol. 5(1), 140–166. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol5010009 (2023).

Sanati, S., Morsali, A. & García, H. First-row transition metal-based materials derived from bimetallic metal–organic frameworks as highly efficient electrocatalysts for electrochemical water splitting. Energy & Environ. Sci. 15(8), 3119–3151. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EE03614A (2022).

Hoefnagel, M., Rademaker, D. & Hetterscheid, D. Directing the selectivity of oxygen reduction to water by confining a Cu catalyst in a metal organic framework. ChemSusChem https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202300392 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. Etching MOF nanomaterials: precise synthesis and electrochemical applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 517, 216016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216016 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Novel nitrogen-doped carbon-coated SnSe 2 based on a post-synthetically modified MOF as a high-performance anode material for LIBs and SIBs. Nanoscale 16(30), 14339–14349. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4nr02418d (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Interface regulation of Zr-MOF/Ni2P@nickel foam as high-efficient electrocatalyst for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 656, 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2023.11.113 (2023).

Abazari, R. et al. Water-stable pillared three-dimensional Zn–V bimetal–organic framework for promoted electrocatalytic urea oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 63(12), 5642–5651. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c00053 (2024).

Peng, Y., Sanati, S., Morsali, A. & García, H. Metal–organic frameworks as electrocatalysts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 62(9), e202214707. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202214707 (2023).

Lv, Y. et al. Tuning octahedron sites of CoV2O4 via cationic competition for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Small https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202402402 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Regulating the electronic structure of metal-organic frameworks by introducing Mn for enhanced oxygen evolution activity. Inorg. Chem. 63(6), 2997–3004. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03769 (2024).

Fang, X., Choi, J. Y., Stodolka, M., Pham, H. T. & Park, J. Advancing electrically conductive metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic energy conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 57(16), 2316–2325. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00280 (2024).

Hussain, N., Abbas, Z., Ansari, S. N., Kedarnath, G. & Mobin, S. M. Phosphorization engineering on a mof-derived metal phosphide heterostructure (Cu/Cu3P@ NC) as an electrode for enhanced supercapacitor performance. Inorg. Chem. 62(42), 17083–17092. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c01440 (2023).

Shahzadi, S., Akhtar, M., Arshad, M., Ijaz, M. & Janjua, M. A review on synthesis of MOF-derived carbon composites: innovations in electrochemical, environmental and electrocatalytic technologies. RSC Adv. 14, 27575–27607. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra05183a (2024).

Li, H. et al. B, N dual-doped porous carbon nanoframeworks as bifunctional peroxymonosulfate activators for ultrafast adsorption and decomposition of microcontaminants in water. Chem. Eng. J. 503, 158349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.158343 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Redox-mediated TEMPO-based donor-acceptor covalent organic framework for efficient photo-induced hydrogen peroxide generation. Angewandte Chemie 137(18), e202500924. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202500924 (2025).

Yin, Y., Fan, T., Fang, L., Wu, G. & Li, L. TEMPO-functionalized porous aromatic framework for efficient and selective electrocatalytic oxidation of cyclooctene. Mol. Catal. 569, 114558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2024.114558 (2024).

Xu, W. et al. Unraveling the potential dependence of active structures and reaction mechanism of Ni-based MOFs electrocatalysts for alkaline OER. Small 20(49), 2407328. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202407328 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synthesizing MOF-derived NiNC catalyst via surfactant modified strategy for efficient electrocatalytic CO2 to CO. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 631, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2022.10.146 (2022).

Rezvani, M. A., Ardeshiri, H. H., Ghafuri, H. & Khalafi, N. Fe2W18Fe4@ MOF-Ni-100 nanocomposite: Insights into synthesis and application as a promising material towards the electrocatalytic water oxidation. Adv. Powder Technol. 35(4), 104380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2024.104380 (2024).

Nyakuchena, J., & Nyakuchena, J. (First Place Poster Award) Probing charge transport mechanisms in 2D metal organic frameworks. in electrochemical society meeting abstracts 243 (No. 17, pp. 2825-2825). The Electrochemical Society, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1149/ma2023-01172825mtgabs 2023

Liu, K. K., Meng, Z., Fang, Y. & Jiang, H. L. Conductive MOFs for electrocatalysis and electrochemical sensor. EScience 3(6), 100133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esci.2023.100133 (2023).

Fischer, T. L., Tepaske, M. A. & Suhm, M. A. Hydrogen sharing between two nitroxyl radicals in the gas phase and other microsolvation effects on the infrared spectrum of a bulky hydroxylamine. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25(16), 11324–11330. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp01156a (2023).

Zheng, Y. Z., Zhao, R., Liu, S. Y., Du, X. Y. & Zhou, Y. The molecular nature of the eliminating azeotropy in water–acetonitrile system by ionic liquid entrainer using FTIR and DFT calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 1324, 140934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.140934 (2025).

Khodair, Z. T., Ibrahim, N. M., Kadhim, T. J. & Mohammad, A. M. Synthesis and characterization of nickel oxide (NiO) nanoparticles using an environmentally friendly method, and their biomedical applications. Chem. Phys. Lett. 797, 139564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2022.139564 (2022).

Rezayati, S., Kalantari, F. & Ramazani, A. Picolylamine–Ni(ii) complex attached on 1,3,5-triazine-immobilized silica-coated Fe3O4 core/shell magnetic nanoparticles as an environmentally friendly and recyclable catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of substituted pyridine derivatives. RSC Adv. 13, 12869–12888. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ra01826a (2023).

Tang, P. et al. Fe, Ni-based metal-organic frameworks embedded in nanoporous nitrogen-doped graphene as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Nanomaterials https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14090751 (2024).

Zhao, Z., Zhao, H., Du, X. & Zhang, X. Controlled synthesis of M-MnS/Ni3S2 (M= Zr, Ce, Bi and V) nanoarrays on nickel foam for overall urea splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 88, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.09.193 (2024).

Yu, L., Ma, X. & Liang, Q. NiMn metal-organic phosphate spheres with potential for electrochemical water oxidation in neutral media. Mater. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2025.130436 (2025).

Mohamad Ali, B. et al. TEMPO-grafted polystyrene/polymethacrylate organosiloxane janus nanohybrids as efficient pickering interfacial catalyst for selective aerobic oxidation of cinnamyl alcohol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16(16), 20409–20418. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c00645 (2024).

Bera, K. et al. Strategically incorporated V in rod-like Ni-MOF as an effective catalyst for the water oxidation reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 14(10), 2858–2867. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3CY01630G (2024).

Si, X., Huang, Y., Han, M. & Luo, L. Electrochemical sensor based on Co-MOF for the detection of dihydromyricetin in ampelopsis grossedentata. Molecules 30(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30010180 (2025).

Kormányos, A., Szirmai, A., Endrodi, B. & Janáky, C. Stable operation of paired CO2 reduction/glycerol oxidation at high current density. ACS Catal. 14(9), 6503–6512. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c05952 (2024).

Luo, H. et al. Selective glycerol to lactic acid conversion via a tandem effect between platinum and metal oxides with abundant acid groups. Ees Catal. 3(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EY00236A (2025).

Aslam, M., Navlani-García, M., Cazorla-Amorós, D. & Luo, H. Efficient and selective glycerol electrolysis for the co-production of lactic acid and hydrogen with multi-component Pt/C-zeolite catalyst. J. Phys.: Mater. 7(1), 015002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7639/ad0561 (2023).

Khakyzadeh, V. & Sediqi, S. The electro-oxidation of primary alcohols via a coral-shaped cobalt metal–organic framework modified graphite electrode in neutral media. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 8560. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12200-w (2022).

Dai, S. et al. Iron-doped novel Co-based metal–organic frameworks for preparation of bifunctional catalysts with an amorphous structure for OER/HER in alkaline solution. Dalton Trans. 51(40), 15446–15457. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2dt01837c (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Core-shell MOF-derived Fe3C-Co-NC as high-performance ORR/OER bifunctional catalyst. J. Alloy. Compd. 948, 169728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169728 (2023).

Yan, X. et al. Redox synergy: enhancing gas sensing stability in 2D conjugated metal-organic frameworks via balancing metal node and ligand reactivity. Angewandte Chemie https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202408189 (2024).

Du, Y. et al. Co-heteroatom-based MOFs for bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions. Inorg. Chem. 60(17), 13434–13439. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01781 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22302180) and the Scientific Research Start-up Fund of Zhengzhou University of Technology and Engineering (Grant No. 22109).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z. conceived and designed the study. W.Z., Y.W., and L.W. performed the material synthesis and structural characterization (including SEM, TEM, XRD, XPS, and FTIR analyses). Y.L. and H.S. conducted the electrochemical experiments (CV, LSV, EIS, and CA tests) and data analysis. C.L. and Y.W. contributed to the interpretation of the experimental results and discussion of the catalytic mechanism. D.Z. and J.Z. assisted in the preparation of samples and optimization of synthesis conditions. W.Z. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Wang, Y., Wang, L. et al. Structural functionalization of TEMPO modified Ni-MOF for electrocatalytic applications. Sci Rep 15, 42694 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26863-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26863-8