Abstract

Simplified (“minimal monitoring”) pathways can expand access to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) by reducing visit burden. In Japan, where hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients are among the oldest worldwide, whether DAA regimens can be delivered safely and effectively with fewer visits remains unclear, and real-world outcomes with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir are scarce. We evaluated effectiveness, safety, and visit frequency in a multicenter cohort. Sixty patients with HCV-infection, with or without compensated liver cirrhosis, received 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir with follow-up to sustained virologic response at 12 weeks post-treatment (SVR12). The visit number was set with no schedule and analyzed post hoc (≤ 3 vs. ≥4 visits). There were 1–8 outpatient visits (median 3). SVR12 was 96.7% by intention-to-treat (ITT; 58/60; 95% CI, 88.6–99.6) and 100% per protocol (57/57; 95% CI, 90.0–100.0). Cure rates were comparable (ITT 95.8–97.2% for ≤ 3 vs. ≥4 visits; p = 1.00; PP 100% in both). Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir was well-tolerated: adverse events were recorded in 10%, none grade ≥ 3, no treatment-related serious events, and no toxicity-related discontinuations. Two patients were lost to follow-up; one who discontinued treatment achieved SVR12. This is the first Japanese real-world evaluation of DAA under simplified monitoring and supports low-burden pathways with high efficacy and safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to the advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) targeting hepatitis C virus (HCV) proteins, nearly all infected individuals are eligible for treatment, with sustained virologic response (SVR) rates exceeding 95% now achievable1. Given their favorable safety profile, DAAs can be administered to older adults and patients with comorbidities, including HIV coinfection and dialysis dependence2,3,4,5. However, the need for frequent outpatient visits during DAA therapy can serve as a barrier, preventing some patients from fully engaging in treatment despite diagnosis. International reports suggest that, with the current DAAs, known for their high safety and efficacy, therapy can be effectively administered with infrequent outpatient monitoring6,7.

In Japan, the situation is complicated by the fact that a large proportion of HCV-infected patients are elderly8, often presenting with multiple comorbidities and requiring concomitant medications. As a result, there is limited real-world data allowing whether reducing monitoring frequency (minimal monitoring) compromises safety or efficacy in this population to be determined. Sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir has exhibited high safety and efficacy across all HCV genotypes9,10,11. Although treatment indications in Japan have recently expanded to include patients with chronic hepatitis C and compensated cirrhosis, clinical data from routine practice remain limited. Furthermore, in a clinical trial involving 37 Japanese patients12, outpatient visits were mandated at treatment initiation and at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-treatment; thus, simplified monitoring has not yet been utilized.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir in a real-world prospective, multicenter trial and to clarify the impact on treatment outcomes and safety in cases where the number of outpatient visits from treatment initiation to SVR12 was three or fewer.

Methods

Patients and study design

This study was conducted as a multicenter prospective study between January 2023 and August 2025; patients with chronic hepatitis C with or without compensated cirrhosis were enrolled at institutions participating in the NORTE Study Group 13,14,15,16, comprising 21 hepatology centers across Hokkaido Prefecture, and received 12-week combination therapy of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir. Patients with chronic HCV infection, with or without compensated cirrhosis, who were receiving outpatient care at the participating institutions between January 2023 and August 2025 were eligible for inclusion. Eligible individuals were required to be at least 20 years of age at the time of obtaining informed consent, be scheduled for 12 weeks of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir treatment as standard clinical care, and provide voluntary informed consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation of this study, demonstrating an adequate understanding of its objectives and potential risks. Patients previously treated with DAAs for their current HCV episode were excluded. In addition, patients with a history of liver transplantation, co-infection with HIV or hepatitis B virus, other significant liver pathology, decompensated cirrhosis (Child–Pugh B or C), or severe renal dysfunction (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), including those undergoing hemodialysis, were excluded from this study. Compensated cirrhosis was defined based on liver function tests, imaging studies, and/or a FibroScan value of ≥ 12.5 kPa according to previous studies17. Prior to treatment initiation, patients underwent imaging to confirm the absence of hepatocellular carcinoma and received laboratory assessments, including HCV serotyping, liver function tests, and renal function tests. In addition, we evaluated the types and counts of concomitant medications used and comorbidities present in all patients. Visit frequency from the start of DAA therapy to SVR12 confirmation was not protocol-mandated. A “visit” was defined as an in-person hospital outpatient encounter, typically involving clinical evaluation and blood sampling. Visit frequency was determined through shared decision-making between the attending physician and the patient, based on clinical status and logistical considerations. The number of visits was primarily aligned with patient preferences. Although DAA clinical trials commonly employ biweekly follow-up, this real-world cohort followed routine care without mandated intervals. Although an increased visit frequency would be anticipated in the presence of serious adverse events, no adverse event-related increase in visit counts was observed in our study. For analysis, we dichotomized the cohort at the observed median number of visits between treatment initiation and SVR12 confirmation (≤ 3 vs. ≥4 visits).

The study protocol followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participating patients provided informed consent. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Hokkaido University Hospital (022–0314) and the committee of each participating institution. This multicenter, prospective, observational cohort was registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR; UMIN000050343).

The primary endpoints were the rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks post-treatment (SVR12) and the safety profile during therapy. Additionally, we examined the relationship between the number of clinic visits during treatment and clinical outcomes.

Treatment protocol of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir

All participants were scheduled to receive a once-daily fixed‐dose combination of sofosbuvir (400 mg) and velpatasvir (100 mg) (Epclusa®; Gilead Sciences K.K., Tokyo, Japan) for 12 weeks12.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. SVR rates were evaluated by conducting intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. SVR12 was assessed 12 weeks after treatment completion. The ITT population comprised all patients who initiated sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; patients without an assessable SVR12 (e.g., those who were lost to follow-up) were counted as non-responders for ITT. The per-protocol (PP) population comprised patients who had completed the planned 12-week sofosbuvir/velpatasvir regimen without major protocol deviations and for whom SVR12 was confirmed. Major protocol deviations were prespecified as early treatment discontinuation or missing SVR12 assessment. Accordingly, two patients lost to follow-up were included as non-responders in the ITT analysis and excluded from the PP analysis; one patient who discontinued treatment at week 9 because of suspected pregnancy was excluded from the PP set, but was retained in the ITT analysis and achieved SVR12. All statistical analyses were two-tailed, with significance defined at P < 0.05. Data processing was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Japan, Tokyo) and Prism version 7.03 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Patients

Patients with chronic HCV infection were screened from institutions participating in the NORTE Study Group; a total of 60 patients were included in this multicenter prospective study. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are illustrated in Table 1. The median age was 66 (IQR, 57–74) years, and 34 (56.7%) were male. The baseline median HCV-RNA titer was 6.5 Log IU/mL (IQR, 6.0–6.8). The median aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were 42.5 IU/L (IQR, 32–82) and 44.5 IU/L (IQR, 26–109), respectively. The median number of baseline comorbidities was 2 (IQR, 1–3). In the cohort (n = 60), the most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (20/60, 33.3%), diabetes mellitus (7/60, 11.7%), insomnia (6/60, 10.0%), hyperuricemia/gout (5/60, 8.3%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (4/60, 6.7%), benign prostatic hyperplasia (4/60, 6.7%), dyslipidemia (4/60, 6.7%), history of non-hepatic malignancy (3/60, 5.0%), atrial fibrillation/flutter (3/60, 5.0%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3/60, 5.0%). Each condition was counted once per patient, and synonymous entries were harmonized. The median number of baseline concomitant medications was 3 (IQR, 0–5). Among the 60 patients, the most frequently used concomitant medications were amlodipine (13/60, 21.7%), ursodeoxycholic acid (6/60, 10.0%), vonoprazan (6/60, 10.0%), rosuvastatin (5/60, 8.3%), sacubitril/valsartan (4/60, 6.7%), zolpidem (4/60, 6.7%), lemborexant (4/60, 6.7%), febuxostat (4/60, 6.7%), esomeprazole (3/60, 5.0%), and edoxaban (3/60, 5.0%). The median number of outpatient visits until SVR12 was 3 (IQR, 2–5; range, 1–8 visits). Accordingly, patients were stratified into two groups: those with three or fewer visits (n = 36) and those with four or more visits (n = 24), and treatment efficacy and safety were compared between them. A comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with three or fewer visits and those with four or more visits revealed that baseline profiles were similar across groups (Table 1).

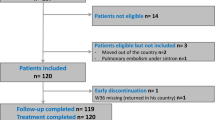

Of these 60 included patients, 59 completed treatments; 1 patient discontinued treatment at week 9 due to pregnancy; nevertheless, she achieved SVR12. She subsequently had an uncomplicated delivery, and no abnormal findings were noted in the neonate. Two patients were lost to follow-up before SVR12 assessment, leaving fifty-seven patients in the PP set. The study flow is summarized in Fig. 1.

Study flow. Sixty patients with chronic hepatitis C were enrolled in this study. Of these, 59 completed treatments, with 1 discontinuation due to suspected pregnancy (who nevertheless achieved SVR12). Two patients were lost to follow-up. The remaining 57 patients were included in the per-protocol analysis, comprising 22 patients who attended ≥ 4 visits before SVR12 and 35 patients who attended ≤ 3 visits.

SVR12 by visit frequency: ITT analysis

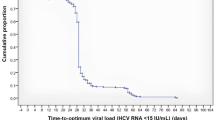

The overall SVR12 rate by ITT analysis was 96.7% (58/60) (95% CI: 88.6%–99.6%).

(Fig. 2). When stratified by the number of outpatient visits from treatment initiation to the SVR12 assessment (≤ 3 vs. ≥4), SVR12 rates were 23/24 (95.8%; 95% CI, 78.9–99.9) in the ≥ 4-visit group and 35/36 (97.2%; 95% CI, 85.5–99.9) in the ≤ 3-visit group (Fig. 2A). There was no significant difference between groups (p = 1.00).

Overall SVR rate and SVR12 rates by visit frequency (≤ 3 vs. ≥4): ITT and per-protocol analyses. (A) SVR and SVR12 rates by visit frequency (per-protocol set). Panel (A) shows SVR12 rates in the per-protocol analysis, comparing patients with ≤ 3 visits with those with ≥ 4 visits before SVR12. (B) SVR12 rates by visit frequency (ITT set). Panel (B) shows SVR12 rates in the ITT analysis across the same groups. In both analyses, cure rates were comparable between groups.

SVR12 by visit frequency: PP analysis

The overall SVR12 rate was 100% (57/57); 95% CI, 90.0–100.0. In the PP set, SVR12 was achieved by 22/22 patients (100.0%; 95% CI, 84.6–100.0) in the ≥ 4-visit group and 35/35 patients (100.0%; 95% CI, 90.0–100.0) in the ≤ 3-visit group (Fig. 2B). The between-group comparison again showed no significant difference (p = 1.00).

Safety

Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir were generally well tolerated (Table 2). Adverse events of any grade occurred in six patients (10%), with no significant differences between groups. No grade-3/4 events, treatment-related serious adverse events, or discontinuations were observed. A single pregnancy was reported as a serious adverse event, but it was not treatment-related. Other minor events, such as headache, rash, or fever, were infrequent and comparable across groups.

Discussion

In this prospective, multicenter study, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C—including those with compensated cirrhosis—achieved an intention-to-treat SVR12 of 96.7% (58/60; 95% CI, 88.6–99.6) and a per-protocol SVR12 of 100% (57/57; 95% CI, 90.0–100.0). The median number of outpatient visits from treatment initiation to SVR12 was 3 (range, 1–8). Importantly, SVR12 did not differ by visit frequency using post hoc stratification at the median, SVR12 was 97.2% (35/36) with ≤ 3 visits and 95.8% (23/24) with ≤ 4 visits by ITT (p = 1.00), and 100% in both strata by PP. Safety was favorable: no grade 3/4 events, no treatment-related serious adverse events, and no discontinuations due to toxicity. A pregnancy-related early discontinuation at week 9 achieved SVR12.

In this study, we confirmed the high efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C and in those with HCV-related compensated liver cirrhosis. Additionally, we clarified that simplified monitoring did not compromise the treatment efficacy or safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in routine Japanese care. Our findings, showing that reduced hospital visit frequency had no significant impact on treatment efficacy or safety, are concordant with the previous trial, which prospectively operationalized a minimal-monitoring algorithm and achieved high SVR12 with excellent tolerability across diverse settings6,18.

Compared with previous minimal monitoring studies (median ages of 516 or 47 years old18, our cohort extends these insights to a predominantly older Japanese population (median age 66 years) examined within a simplified monitoring framework, where concerns about comorbidity and polypharmacy often drive conservative follow-up. The absence of efficacy or safety decrement in patients managed with ≤ 3 visits supports the feasibility of “low-touch” pathways when baseline risk is appropriately assessed and clear routes for unplanned contact are ensured. Of note, visit frequency was separated meaningfully between strata (median [range], 2 [1–3] vs. 5 [4–8] visits to the SVR12 time point; p < 0.0001), confirming that our comparison captures a genuine difference in service intensity within routine practice.

From an implementation perspective, simplified monitoring confers several potential benefits: earlier treatment initiation, reduced travel and time burden, reduced clinic congestion, and lower system costs, without detectable loss of efficacy or safety. The pattern of non-virologic outcomes in our study is informative: one early discontinuation due to pregnancy nevertheless achieved SVR12, whereas two losses to follow-up affected ITT estimates, underscoring that retention—not laboratory frequency—drives differences once modern pan-genotypic DAAs are used.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior real-world prospective study has reported clinical outcomes of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis or compensated cirrhosis. This study is, therefore, the first to demonstrate, in a prospective real-world setting, that sofosbuvir/velpatasvir achieves high efficacy and a favorable safety profile, consistent with phase 3 clinical trial results. These findings extend the generalizability of phase-3 results to routine clinical practice, including patients who are more heterogeneous than those enrolled in clinical trials. Nonetheless, the relatively limited sample size and follow-up period warrant cautious interpretation, and longer-term outcomes, such as hepatocarcinogenesis, remain to be investigated.

This study had some limitations. First, this study was not randomized, and visit frequency reflected shared decision-making by clinicians and patients, which may introduce selection confounding. Second, our limited sample size affected the precision of rare adverse-event estimates and reduced power for subgroup analyses, so this study may have been underpowered for detecting small differences in SVR12 rates or adverse-event frequencies. Third, two participants were lost to follow-up before SVR12 ascertainment—importantly, one was from the higher-visit group, indicating that attrition was not confined to minimal monitoring, and this only modestly affected ITT estimates. Furthermore, owing to the real-world design, AEs may have been underreported. Finally, detailed data on patient preferences were lacking. Despite these considerations, to our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir under minimal monitoring in Japan. Moreover, real-world outcomes in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C, including those with compensated cirrhosis, are rarely reported, which strengthens the relevance of our findings for staged clinical adoption.

Conclusions

In conclusion, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir achieved consistently high SVR rates and excellent tolerability, regardless of visit frequency. These results support the adoption of simplified monitoring pathways that preserve treatment efficacy and safety while reducing both patient and healthcare system burden.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Manns, M. P. & Maasoumy, B. Breakthroughs in hepatitis C research: from discovery to cure. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 533–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00608-8 (2022).

Takehara, T. et al. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with or without ribavirin in HCV-infected Japanese patients with decompensated cirrhosis: an open-label phase 3 trial. J. Gastroenterol. 54, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1503-x (2019).

Suda, G., Ogawa, K., Morikawa, K. & Sakamoto, N. Treatment of hepatitis C in special populations. J. Gastroenterol. 53, 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1427-x (2018).

Suda, G. et al. Daclatasvir and asunaprevir in Hemodialysis patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a nationwide retrospective study in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. 53, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1353-y (2018).

Suda, G. et al. The successful retreatment with glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir of genotype 1 or 2 HCV-infected Hemodialysis patients who failed to respond to NS5A and protease inhibitor treatment. Intern. Med. 58, 943–947. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.2077-18 (2019).

Dore, G. J. et al. Simplified monitoring for hepatitis C virus treatment with glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir, a randomised non-inferiority trial. J. Hepatol. 72, 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.010 (2020).

Yang, A., Swamy, N. & Giang, J. Single-center retrospective review of standard versus minimal monitoring for hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral therapy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 65 (102265). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2024.102265. (2025).

Tanaka, J. et al. Burden of chronic hepatitis B and C infections in 2015 and future trends in japan: A simulation study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 22, 100428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100428 (2022).

Foster, G. R. et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 2608–2617. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1512612 (2015).

Gane, E. J. et al. Efficacy of Sofosbuvir, Velpatasvir, and GS-9857 in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 2, 3, 4, or 6 infections in an Open-Label, phase 2 trial. Gastroenterology 151, 902–909. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.038 (2016).

Feld, J. J. et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 2599–2607. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1512610 (2015).

Takehara, T. et al. Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir in adults with hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis in Japan. Hepatol. Res. 52, 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13810 (2022).

Kohya, R. et al. Serum FGF21 as a predictor of response to Atezolizumab and bevacizumab in HCC. JHEP Rep. 7, 101364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2025.101364 (2025).

Suda, G. et al. Prophylactic Tenofovir Alafenamide for hepatitis B virus reactivation and reactivation-related hepatitis. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28452. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28452 (2023).

Suda, G. et al. Efficacy and safety of Daclatasvir and asunaprevir combination therapy in chronic Hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Gastroenterol. 51, 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-016-1162-8 (2016).

Suda, G. et al. Long non-coding RNA PWRN4 associated with post-SVR hepatocellular carcinoma: a genome-wide association study. Biomark. Res. 13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-025-00832-9 (2025).

Kawagishi, N. et al. Serum Angiopoietin-2 Predicts the Occurrence and Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C. Viruses 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010181 (2023).

Solomon, S. S. et al. A minimal monitoring approach for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection (ACTG A5360 [MINMON]): a phase 4, open-label, single-arm trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00397-6 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients who participated in this study and their families.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from Gilead Sciences, Inc, and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; grant numbers: JP25fk0210126, JP25fk0310545, JP24fk0210121, JP25fk0210142, JP25fk0310551, JP25fk0210123, JP25fk0310535, JP25fk0210157, JP25fk0310543, JP25fk0210172 JP25fk0210174, JP25fk0210143).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GS conceived and designed this study, interpreted the data, performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MB, YY, SY, TI, TM, KT, JI, TK, TM, TT, SH, RY, QF, ZY, DY, TT, AM, NY, TK, MO, NK, MN, TS, KO, and NS contributed to patient recruitment, data collection, and clinical management. GS and NS supervised this study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Professor Naoya Sakamoto received lecture fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Gilead Sciences, Inc. and AbbVie Inc, grants and endowments from MSD K.K and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and a research grant from AbbVie Inc. Dr. Goki Suda received research grants from Gilead Sciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suda, G., Baba, M., Yamamoto, Y. et al. Simplified monitoring of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C based on a retrospective analysis of a prospective multicenter cohort. Sci Rep 15, 42628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26891-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26891-4