Abstract

Boosting psychological capital (PsyCap) has been linked to better mental health and reduced substance abuse. Amidst the current global mental health crisis, emerging trends in short video consumption and information-seeking pave potential pathways for disseminating innovative approaches to boosting PsyCap. Short, animated storytelling (SAS) videos have shown promise for scaling and engaging audiences with preventive public health messages. This study measured the effect of SAS video content on immediate and medium-term PsyCap and two related constructs, gratitude and happiness. In this 4-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial, we collected data from 8612 US adults, enrolled online via Prolific Academic, from June–July 2024. Participants were randomly assigned to watch either a PsyCap-SAS video or an SAS attention placebo control video (APC-SAS), followed by PsyCap, gratitude and happiness surveys. The remaining arms were Do-nothing control arms, the first exposed to the surveys at Timepoint 1 (T1) and the second remaining un-exposed until Timepoint 2 (T2) 2 weeks later. The primary outcome was PsyCap (measured immediately at T1 and in the medium-term, at T2). Secondary outcomes were gratitude and happiness (immediate and medium-term) as well as voluntary engagement with the intervention video. The PsyCap-SAS video did not significantly increase PsyCap, but did significantly boost gratitude (immediately) and happiness (in both the immediate and medium-term). Surprisingly, the APC-SAS video—a short, animated story video promoting healthy eating—did significantly boost PsyCap, as well as happiness, and this effect was still visible 2 weeks later. No significant changes were observed in either of the Do-nothing control groups. Among participants with chronic diseases or disabilities, short, animated storytelling was particularly effect for boosting these positive psychological resources. This study extends the emerging knowledge base on the potential of short, animated storytelling for boosting protective positive psychological resources, including PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. In the midst of a global mental health crisis, SAS content designed to convey basic health promotion messages, may also be a promising and scalable way to bolster psychological resources in the public.

This trial and its outcomes were registered with clinicaltrials.gov on Feb. 7, 2023 under the identifier NCT05718973. The stage 1 protocol for this Registered Report was accepted in principle on 18/09/23. The protocol, as accepted by the journal, can be found at: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24246511.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Boosting psychological capital (PsyCap) has emerged as a promising approach to addressing the heavy global mental health burden resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic1,2. PsyCap is a compound, measurable psychological construct that includes four, well-defined psychological resources: hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism. Together, these resources are referred to by the acronym “HERO”1 and validated scales have been developed to measure the construct3,4. Prior research characterizes PsyCap as a state, rather than a trait, suggesting that it can be shifted by outside interventions1,5. Recent researched suggests that PsyCap has been positively associated with job satisfaction, positive affect, and flourishing, and negatively associated with negative affect, psychological and physical distress, and mental health problems6,7,8. In general, boosting PsyCap has been linked to improved mental health outcomes and the prevention of substance abuse5,9.

Interventions designed to boost PsyCap have taken several forms in recent years, including in-person trainings, family-based interventions, self-help books and web-based tutorials1,5,10,11. A recent meta-analysis suggests that many of these interventions have been effective for boosting PsyCap12 and these findings were replicated and extended in international populations, with improvements in PsyCap proving to be both replicable and durable over time13. Methods for rapidly and cost-effectively scaling PsyCap interventions, to reach broader populations, have yet to be explored.

Media consumption patterns shifted dramatically after the COVID-19 pandemic, with people spending more time on social media and consuming more short-format video content than ever before14,15,16,17. While misinformation on social media remains problematic, novel approaches to health communication, like short, animated storytelling (SAS) have capitalized on this shift to rapidly scale science-based health messages to the public18,19. First developed during the pandemic, SAS videos effectively conveyed critical information in a compelling format, resulting in high voluntary engagement and spontaneous sharing on social media19,20.

This study aims to explore the effect of using the SAS video approach for the promotion of PsyCap, and related psychological resources, in the US public, using a highly engaging, light-touch and easily scalable PsyCap-SAS video intervention. We hypothesize that short, animated storytelling videos will boost PsyCap, gratitude and happiness scores of adults across the US in both the short and medium-term.

Objectives

In this study, we aim:

-

1.

To evaluate the immediate and medium-term effects of a PsyCap-SAS video intervention on PsyCap

-

2.

To measure the immediate effect of a PsyCap-SAS video intervention on gratitude and happiness

-

3.

To measure the effect of exposure to PsyCap, gratitude and happiness scales on PsyCap, gratitude and happiness outcomes in the medium term (after 2 weeks)

-

4.

To measure voluntary engagement with SAS video content aimed at boosting PsyCap.

Methods

Trial design

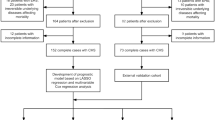

We conducted a parallel-arm, randomized-controlled trial examining the effect of short, animated storytelling video content on PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. We engaged Prolific Academic, an online, academic research platform, aiming to recruit 10,000 US participants (aged 18–59) into four groups: (1) Intervention (PsyCap-SAS), (2) Do-nothing Exposed, (3) Attention Placebo Control (APC-SAS), and (4) Do-nothing Unexposed. Each group’s outcomes were measured at two time points, two weeks apart.

At Timepoint 1, the Intervention Arm watched a PsyCap-SAS video designed to promote PsyCap and, immediately thereafter, completed three surveys: a 12-item validated PsyCap scale (the CPC-12R)3, a 6-item validated gratitude scale (the GQ-6)21 and a single-item validated happiness scale22. The Do-nothing Exposed Control Arm watched no video content at Timepoint 1, but completed all three surveys. The Attention Placebo Control (APC-SAS) Arm viewed a short, animated, storytelling APC video, which we expected to be unrelated to the outcomes measured in this trial. (The APC-SAS was an animated story video aimed at promoting healthy eating.) Thereafter, participants completed all three surveys. The Un-exposed Control Arm watched neither video, nor completed surveys at Timepoint 1.

Two weeks later, all four arms completed the three surveys. For the first three arms, this was a repeat exposure to the surveys and for the fourth arm, this was their first time completing the surveys. After completion of the trial, all four arms were offered post-trial access to both the PsyCap-SAS and APC-SAS videos.

Figure 1 illustrates the planned trial design, and the research questions to be explored.

Study setting

This trial was conducted entirely online. Participants were recruited through the Prolific Academic ProA (https://www.prolific.co) academic research platform. The study was also hosted online, via the secure, online experiment builder platform, Gorilla, where participants were randomized, took part in the intervention, and responded to the survey questions.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Eligible participants were English-speaking adults, between the ages of 18 and 59 years, living in the US. ProA recruited participants from their registered research participant pool.

Informed consent

The ProA platform obtained informed consent from all participants prior to their enrollment into the study. This process involved thoroughly informing all participants about the purpose, potential benefits, and potential risks of participating in the study. Contact information for both the principal investigator and the Stanford Ethics Review Board was provided to participants. Individuals registered on ProA must agree to the terms and conditions for collection and use of participant data, as well as the privacy policy of ProA, upon registration.

Intervention

Intervention and attention placebo control video descriptions

The PsyCap-SAS intervention used in this trial was a short, 2D animated storytelling video designed to boost positive psychological capital, abbreviated here as PsyCap. The video was developed by a group of educators, psychiatrists, psychologists, communication specialists and global mental health advocates from the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Stanford Medicine, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Medical School, UNICEF and the WHO. The approximately 3.5 min animated video tells the story of Ario, a fantasy creature living in the clouds, who has lost the ability to fly in the post-pandemic environment, which has been described as volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous1. Despite this, Ario is determined to help young people around the world who are struggling to cope after the COVID-19 pandemic. With the help of his friends, Ario reconnects with the four “HERO” elements of his own psychological capital (hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism) and he remembers how to fly. The main character embodies all four PsyCap elements equally and they allow him to travel the world, lifting others up along his journey. Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes the importance of observing and modelling the behaviors, attitudes, and emotional reactions of others, with the result being that the viewer adopts similar behaviors, attitudes and emotions23. The PsyCap-SAS intervention video was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic as an adaptation of the WHO’s children’s book, My Hero is You24.

The attention placebo control (APC) in this trial was also a short, animated storytelling (SAS) video, developed by the same team at Stanford Medicine, in collaboration with faculty at the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health and the Freiberg University Clinic Cardiology Department, in Germany. The APC-SAS video was a short, 2D animated video, focused on boosting knowledge about the sodium content in various foods. The video was created to promote awareness and behavioral intention to reduce dietary sodium, thereby supporting heart health. The APC-SAS video portrays a humorous, animated story in which the main character is a heart, who wakes his owner up complaining that he is under too much pressure, and on the verge of quitting. The owner, shocked and confused, listens as his heart admonishes him for his dietary sodium intake, and then proceeds to educate him about ways in which he can consume a lower sodium diet. The video ends with the owner promising to reduce his dietary sodium if the heart promises not to quit on him. The heart agrees, goes back to work, and the man wakes up to cook a healthy, low-sodium breakfast, telling his wife that he had “the craziest dream”.

Once considered only a young children’s medium, animation has grown in popularity among adolescents and even adults. Recent decades have seen the success of several animated shows aimed primarily at adolescents and adults, (for example, the popular comedy series The Simpsons, Rick and Morty, and Central Park). Today, animation is a driving force in adolescent and adult media25. Since co-viewing of children’s media has been shown to support both children’s and parents’ emotional wellbeing26, this study will explore whether an intervention designed to boost hope and other positive psychological characteristics in children, can measurably boost these characteristics in adults as well. The intervention video contains no dialogue. Instead, it is propelled by an inspiring, original soundtrack, also designed to promote hopefulness. The APC-SAS is a 2D animated video of a similar length, originally created for adults, and focused on educating viewers about how to reduce sodium in their diets. Links to both videos can be found in the Multimedia Appendix. Figure 2 features key screenshots from the intervention and APC videos.

Measures

Control groups and comparators

At Timepoint 1, PsyCap, GQ-6 and happiness scale scores were compared between the Intervention Arm and the Do-Nothing Exposed Control Arm, “Exposed” because they were exposed to the outcome measures at Timepoint 1. Assuming successful randomization, the only difference between these two arms at the first data collection timepoint, was that the Intervention Arm had viewed the Intervention video and the Do-Nothing Exposed Control Arm had not. In order to isolate the effect of the PsyCap messaging specifically, and to exclude the possibility of a general effect on our outcomes from SAS video-viewing, the scores of Arm 1 and Arm 2 were also compared with the scores of Arm 3, the Attention Placebo Control Arm. This third arm watched a short, animated storytelling video about dietary sodium. In this first study phase, the fourth study arm remained un-exposed to both the video content and the surveys. Two weeks later, all four study arms completed the CPC-12R, the GQ-6 as well as a single-item validated happiness scale. The choice of a two-week follow-up for the medium-term data collection point was based on: a) the minimal nature of the intervention—participants received only a single exposure to a short duration (~ 3 min) “micro” intervention and b) published recommendations for conducting online experiments27. Comparisons between the Intervention Arm and the Do-Nothing Un-Exposed Control arm at 2-weeks allowed us to measure the effect of the PsyCap video after two weeks on these psychological constructs. Comparisons between Arm 3 and Arm 4 allowed us to determine whether any observed effect related to viewing of the APC-SAS video persisted after two weeks and comparisons between Arm 2 and Arm 4 allowed us to measure the potential effect of merely exposing participants to these psychological scales, on their PsyCap, gratitude and happiness scores, 2 weeks later.

Primary outcome

For our primary outcome, we measured the immediate effect of the PsyCap-SAS Intervention video on psychological capital (PsyCap).

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcomes include quantifying:

-

(a)

the medium-term effect of the PsyCap-SAS intervention video on PsyCap after two weeks

-

(b)

the effect of the PsyCap-SAS intervention video on gratitude and happiness, both related to the construct of positive psychological capital

-

(c)

the effect of exposure to PsyCap and related psychological scales on these same outcomes, measured two weeks later.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size needed for comparison of means between selected arms as detailed in the trial design. This was done independently for the primary and secondary outcomes based on the score of each scale, upon which we selected the most conservative sample size for our study. All the calculations are based on one-tailed comparisons of the mean score with equal variance, equal allocation between arms, a type I error of 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons, and a high power of 95% to detect changes in the mean score.

Recent trends towards increasing social media use and consumption of short video content has shortened consumers’ attention spans28. Content is often posted on social media in real time and social media users around the globe are able to react in seconds. This means that we are increasingly accustomed to consuming information in micro-doses, amplified through the repeat exposure that results from multiple reactions and reposts before moving on to the next sound byte28. As a result of these trends, we assume that short, animated health messages would be most effective if consumed repeatedly over time, with their messages amplified through community engagement. In our study, participants had only one opportunity to engage with the video intervention, before we measured its effect. Thus, we aimed to capture only a very small change in the score of the individual scales, presuming that these small changes could be amplified in the real-world social media environment.

The primary outcome, the PsyCap scale (CPC-12R), consists of 12 items. Participants can score between 12 and 72, but prior research suggests that the mean score is 54.47 (SD = 8.131)3. A recent meta-analysis of PsyCap interventions found the overall effect of the interventions to be significant, but small12. One intervention, described in the literature as an effective “micro-intervention” yielded a 3% increase in PsyCap (an increase of 1.63 points, assuming a mean score of 54.47) however the “micro-intervention” described in that study was more than an hour long10. Given that our intervention is less than 3.5 min long, we would consider an increase of 1 point to be a highly significant effect. The required sample size is calculated as 2087 individuals per arm for this outcome. The secondary outcome, the GQ-6, consists of 6 items on a 7-point Likert scale. Participants can score between 6 and 42, but prior research suggests that the mean score is 34.3 (SD = 8.12)29. We assume that watching the video can move the score up by 1 point, which yields a required sample size of 2081 per arm. The single-item validated happiness scale consists of one question that can be answered by a number from 0 to 10, thus the participants can score between 0 and 10 points. Prior research suggests that the mean score is 6.5 (SD = 2.9)22. Detecting a change of 0.5 points requires a sample size of 1063 per arm.

The largest sample size per arm across the three main outcomes is thus 2087. To account for a potential 20% attrition rate due to the longitudinal design (personal communication with ProA), the sample size for each arm of the study is increased to 2504 participants per arm. For this study, we will recruit 10,000 participants (2500 per arm) which allows us to detect the defined score changes by the intervention with the power approximately 95%.

Assignment of interventions: allocation

The study was hosted on the Gorilla experiment-builder platform.. A random allocation sequence was used to allocate participants 1:1:1:1 to the four trial arms. The randomization algorithm does not allow the investigators to influence the individual trial arm allocations and provides an effective concealment mechanism.

Assignment of interventions: blinding

All study investigators and researchers involved in the data analyses remained blinded to the trial arm allocation for the entire study duration. Unblinding was not needed.

Participant timeline

Over a 4-week period, participants were recruited and enrolled on the ProA platform. The first phase of the trial (involving video viewing and subsequent scale response submission) occurred two weeks before the second phase (follow-up scale response submission). Immediately after the completion of the second phase, all participants were given post-trial access to the SAS video content. Their view times were recorded on Gorilla and used as an indicator of voluntary participant engagement with this type of content. Since the dissemination of SAS interventions relies on spontaneous viewing and sharing, engagement with the content is an important metric.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Participants were informed upon enrolment that they would be paid ($3.50 for 15 min) after completing the entire study. We chose to follow up after two weeks in order to optimize our need to assess the potential transience of our outcomes over time, while minimizing drop-out rates. We also embedded attention-check questions within the surveys to ensure that participants watched the video and were reading the survey questions carefully.

In order to ensure that participants had carefully watched the intervention (or APC) video, they were asked a question related to the content of the video that was straightforward for participants who had watched their assigned video. Participants who had not attended carefully would likely not be able to answer correctly, and these participants were excluded because we considered the intervention (or APC) not to have been delivered.

Throughout the surveys, we also added attention check questions that were unrelated to the PsyCap scales and had an obvious and unmistakable answer, provided the participant read the question. The attentions checks were formatted similarly to the assessment questions, so they were not easily distinguishable if a participant was “clicking through” the survey. A sample attention check question is shown in Appendix Fig. 7. The data of participants who failed two or more attention checks was excluded from the analysis.

Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions

We did not discontinue or modify the allocated interventions during the course of the trial. Participants were aware that they could discontinue and withdraw their consent to participate at any time. We did not use incomplete survey data, except at a meta-level where we reported the aggregate number of incomplete surveys. Participants could only complete the surveys once at each time point.

Relevant concomitant care permitted or prohibited during the trial

Concomitant care was neither permitted nor prohibited during this study.

Provisions for post-trial care

The foreseeable risks associated with participating in this study were extremely minimal. Participants had volunteered and consented to participate in this short, animated storytelling trial, and they were able to withdraw at any time. The investigators could also be contacted at any time after the study.

Data collection and management

Plans for assessment and collection of outcomes

Data was collected by the Gorilla experiment-builder platform. Data was submitted directly to Gorilla by individual participants when they chose their responses to the various scale questions hosted on the platform. We completed data collection over a 4-week period.

Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up

Participants were automatically timed out of the study if they took longer than 45 min to complete either phase of the survey. This ensured that participants did not burden the system with incomplete surveys. Participants remained anonymous to the investigators throughout the study, so there was no way to follow-up with participants.

Data management

All data collected during this study were stored by Gorilla on its secure, encrypted cloud platform. This platform is hosted on Microsoft Azure, Republic of Ireland. Industry-standard cryptography is used to encrypt the Gorilla database but the research team maintained control over the data, with the ability to access the completely anonymized datasets at any time. For statistical analysis purposes, the data was downloaded and safely stored on a secure computing system maintained by our co-investigators at Heidelberg University, in Germany.

Confidentiality

All participants remained completely anonymous to the investigators in this trial. Investigators did not have access to identifying information associated with the participants’ unique IDs. Participants were informed that, if they chose to contact the investigators with concerns or questions about the study, their names may be revealed to the study team however the team would keep all information and correspondence confidential.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods for primary and secondary outcomes

For our study, descriptive statistics were used to describe the distribution of the measured scores by demographics factors, including factors such as gender, age, region/state of residence, political affiliation, socio-economic status, race and ethnicity, that could affect the scoring. Data on demographic characteristics of participants were provided by the Prolific Academic platform.

Primary outcomes

For each participant, we calculated total general item scores as well as scores by sub-domains in the PsyCap scale (CPC-12R; min. = 12, max. = 72 points). The mean score for each study arm at Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 2 were calculated and compared between the intervention arms and the “Do-nothing Exposed” arm at Timepoint 1, using the t-test for two independent groups. We also used multilevel linear regression analyses to control for demographic factors and other potential variables as needed.

Secondary outcomes

As secondary outcomes, we used the statistical methods described above to evaluate both the immediate and medium-term effects of the PsyCap-SAS video intervention on PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. The methods included t-test for independent groups, matched t-test for dependent groups, and multilevel linear regression models. We analyzed the mean scores of the PsyCap scale, the GQ-6 scale, and the single-item validated happiness scale at Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 2, with a focus on the impact of the SAS video content on the score outcomes. We also used STATA and R statistical analysis software for the analyses28.

Methods for additional analyses

To quantify the participants’ engagement, we used the graphical experiment builder in Gorilla to give participants an option, after completing the trial, to rewatch the videos before exiting the platform. We recorded timestamps when the participant finished the experiment, when they clicked on a video to watch it and when they decided to leave after having voluntarily watched. We recorded the length of time spent watching the videos. We used regression models to describe effects of sociodemographic factors and the PsyCap score on engagement time.

Methods in analysis to handle protocol non-adherence and any statistical methods to handle missing data

Participants in the study had a time limit of 45 min to watch the SAS videos and answer the questionnaires. All survey items were designed such that participants were required to complete them before the questionnaire could be submitted, thus no incomplete surveys were included in the analyses. All participants who completed the first round of the study (Timepoint 1) were included in the follow-up study activity at Timepoint 2. If a participant chose not to take part in the second round (Timepoint 2), their data was not included in the analysis of long-term effects. Participants who failed to watch the videos or respond to the questionnaires were excluded.

Access to participant level data and statistical code

Researchers interested in accessing data or documentation should contact the corresponding author. R code for the analyses will be published together with the planned publications on Github.com as appropriate.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Stanford University IRB on June 7th, 2022, protocol #65160 and a modification was approved on Feb 6th, 2023. There were no further amendments and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Oversight and monitoring

Composition of the coordinating center and trial steering committee

A trial steering committee (TSC) oversaw this study. The TSC included an independent chairperson and members as well as the trial collaborators. We held two TSC meetings. Because of the short duration of the study, additional meetings were not necessary.

Adverse event reporting and harms

Because animated health education videos are an extremely low-risk intervention, we did not anticipate or experience any adverse events. These were especially unlikely given the online format of the trial. The TSC audited the trial conduct at our two planned meetings.

Results

Participant demographics

There were 10,727 individuals invited to participate in the study from June–July 2024 via Prolific. Of these, 10,427 (97%) consented and were randomized into one of the four trial arms. Across the arms, 83% (N = 8612) returned after two weeks to complete the second part of the trial, which included follow-up surveys and post-trial voluntary access to the video interventions (82% in the PsyCap-SAS arm, 81% in the APC-SAS arm, 85% in the Do-nothing Exposed arm; 83% in the Do-nothing Unexposed arm). These 8612 individuals were included in the analyses. Figure 3 shows the actual flow of the trial. All demographic characteristics, which are collected by Prolific when participants enroll, were balanced across the study arms (Table 1).

Appendix Table 3 displays the responses to the study outcome measures across each of the participant characteristics. Several characteristics were associated with higher scores in the CPC-12R, GQ-6 and happiness scale outcomes, including older age, higher education, black ethnicity, higher income, republican political affiliation, and absence of a chronic health condition. Student status was additionally associated with higher CPC-12R score. Women had higher GQ-6 scores compared to men (Appendix Table 3).

Outcomes

At both the immediate and medium-term surveys, more than 99% of participants answered 4 + out of 5 attention check questions correctly. These individuals were included in the analyses of the outcome scores. The overall immediate and medium-term scores across study arms are displayed in Table 2.

We observed no significant increase in PsyCap scores immediately following exposure to the PsyCap-SAS video, (increase of 0.57 points, 95% CI − 0.05, 1.18). However, exposure to the PsyCap-SAS video did result in a statistically significantly increase in immediate gratitude (increase of 0.40 points; 95% CI 0.03, 0.79) and happiness (increase of 0.24 points; 95% CI 0.10, 0.38). The observed increase in happiness remained significant after 2 weeks (Fig. 4).

Exposure to the APC-SAS video, on the other hand, resulted in significantly higher PsyCap (increase of 1.18 points; 95% CI 0.57, 1.80) and happiness scores (increase of 0.19 points; 95% CI 0.06, 0.33) immediately after exposure. These increases also remained significant, although lower, two weeks later (increase of 0.63 points for PsyCap [95% CI 0.01, 1.25] and 0.17 points for happiness score [95% CI 0.04, 0.31]) (Fig. 3). There was no difference between the Do-nothing Exposed and Do-nothing unexposed groups in their scores at T2, and there was no change over time in scores for the Do-nothing Exposed group.

Sub-scale components of PsyCap

Examination of the four sub-scale components of the PsyCap score (Hope, Optimism, Resilience, and Self-Efficacy) revealed that the PsyCap-SAS video primarily increased the Hope sub-score (increase of 0.22 points in the Hope sub-score, 95% CI 0.05, 0.39). Exposure to the APC-SAS video, on the other hand, increased each of the four sub-scores in the immediate survey (0.38 [95% CI 0.21, 0.55] points for Hope; 0.36 [95% CI 0.18, 0.55] points for Optimism; 0.20 [95% CI 0.01, 0.38] points for Resiliency; and 0.24 [95% CI 0.08, 0.40] points for Self-Efficacy), and the effect on the Hope sub-score remained significant two weeks later (increase of 0.21 points [95% CI 0.04, 0.38]) (Fig. 5).

Sensitivity analyses

When we adjusted for baseline sociodemographic characteristics of participants, the directionality and statistical significance of the results remained unchanged, except for the immediate effect of the PsyCap-SAS video on gratitude. This effect was no longer statistically significant in the adjusted model, where we observed an increase of 0.33 points (95% CI − 0.04, 0.70) compared to 0.40 points (95% CI 0.02, 0.79) in the unadjusted model.

Testing interaction terms for each of the participant characteristics in the models showed a significant positive interaction with having a chronic health condition or disability and the PsyCap-SAS video for several outcomes. Among those with a chronic condition, we observed larger positive effects of the PsyCap-SAS video for the Happiness scale and two of the CPC-12R components (hope and optimism). When limiting to the subgroup of individuals with a chronic condition, the PsyCap-SAS arm scored 1.33 points (95% CI 0.05, 2.61) higher in the immediate PsyCap score, 0.47 points (95% CI 0.13, 0.82) higher in the immediate Hope CPC-12R sub-score, 0.43 (95% CI 0.04, 0.81) points higher in the immediate Optimism CPC-12R sub-score, and 0.46 points (95% CI 0.18, 0.73) higher in the immediate Happiness scale, compared to the Do-nothing Exposed arm. There was also a sustained increase in both the Hope sub-score (0.34 points, 95% CI 0.00, 0.68) and the Happiness scale (0.26 points, 95% CI − 0.01, 0.53) among this group for the PsyCap-SAS arm compared to the Do-nothing Exposed arm. Similarly, the APC-SAS video also demonstrated a stronger effect on the CPC-12R scores among the population with a chronic health condition, with an increase of 2.13 points (95% CI 0.83, 3.42) for the immediate overall CPC-12R score, but there was no positive interaction between the APC-SAS video and having a chronic health condition on the Happiness scale.

Post-trial video engagement

After completing the final survey for the study, participants were offered voluntary, post-trial access to one of the SAS videos they had not seen during the trial. They were notified that the trial had been completed, and offered the option to either exit the platform or stay and watch and animated short video. Among these participants, more than half (63%) opted to begin watching the video. Those who watched less than 5 s were counted as not having engaged with the video. Among all participants who completed the study, 30% opted to watch the entire SAS video, until the final scene, (voluntarily watching 3 min:22 s or more) (Fig. 6). Demographic characteristics associated with watching the full video included older age, non-white ethnicity, lower income, and being a non-English-first-language speaker. In adjusted logistic regression models the odds ratios for watching the full video were: 2.36 (95% CI 1.94, 2.88) for age 60 + versus age 18–29; 1.44 (95% CI 1.24, 1.67) for black vs. white ethnicity; 0.69 (95% CI 0.54, 0.88) for income of $150,000 + vs. < $20,000; and 1.30 (95% CI 1.03, 1.65) for non-English-first-language vs. English-first-language speakers. Having a chronic health condition was not associated with voluntary viewing of the PsyCap-SAS video in the post-trial voluntary access phase. Immediate and medium-term survey scores for PsyCap, gratitude and happiness were also not associated with watching the PsyCap-SAS video.

Discussion

This study is the first of its kind to investigate the use of scalable, short, animated storytelling (SAS) videos for boosting psychological capital, gratitude and happiness in US adults, living in the midst of a mental health crisis2. We compared a 2D animated SAS-PsyCap video (a short story aimed explicitly at boosting PsyCap) with a second 2D animated SAS-APC video (a short story aimed at promoting healthy eating). We also compared both of these with two do-nothing control conditions—one that was exposed to the outcome surveys at T1 and a second do-nothing control group that remained unexposed to the surveys until T2. We hypothesized that the greatest gains in PsyCap, gratitude and happiness would result from exposure to the short, animated storytelling video focused explicitly on boosting PsyCap. Surprisingly, we found that the second short, animated story video (focused on improving eating habits) outperformed the SAS video that aimed explicitly to boost PsyCap. In fact, the SAS-APC video significantly boosted PsyCap and Happiness (but not gratitude) in both the immediate and medium term, although the T2 effect was reduced. The SAS-PsyCap intervention video, on the other hand, did not significantly boost PsyCap, but effectively boosted gratitude and happiness, immediately after exposure, with only the effect on happiness remaining significant two weeks later.

These findings suggest that short, animated storytelling videos, even if not explicitly designed to boost PsyCap, may be effective for boosting certain psychological resources, like PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. Notably, gratitude is widely considered to be an adjacent resource and Luthans et al, who defined the PsyCap construct, have discussed the possibility of including it in the HERO model30. Across various global regions, PsyCap has also been shown to boost happiness, with researchers proposing both directly and indirect pathways31,32,33,34. While much of the early literature on PsyCap was focused on work-related outcomes, more recent research has explored the effect of PsyCap on general mental health, including outside of the workplace35,36,37.

Prior research has shown some associations between motivational health messages and increased positive affect and psychological well-being38,39. It is plausible that gaining insight, through a narrated SAS video, into actionable behavior change strategies could leave viewers feeling enabled, thereby boosting hope and psychological capital. Engaging and enabling adult audiences to make lifestyle changes could be even more effective than overtly encouraging people to be more hopeful, grateful and optimistic. Another potential explanation for the superior performance of the SAS-APC video is that this video may have resonated particularly well with an adult audience because it was specifically designed for adults, whereas the SAS-PsyCap video was originally designed for children, as a primary audience, and their parents as a secondary target audience26. This design discrepancy manifested itself primarily in the different styles of humor used in the two SAS videos. The SAS-PsyCap video employed a more playful style of humor, including for example several “mishaps” in which the main character tries to fly and falls, landing in comical locations. The SAS-APC, on the other hand, used a more sophisticated style of humor, telling the story of a man who is awoken by his own heart—the animated main character. The Heart threatens to quit on his owner because he is “under too much pressure”. The relatability and relevance of heart health, as well as the more mature style of humor, may have amplified the effect of the SAS-APC video on PsyCap, gratitude and happiness scores within this adult participant. Future studies should explore comparisons between SAS video interventions and non-SAS videos (for example those showing unrelated real-life footage). Questions about the precise mechanism of action of SAS videos remain unanswered, especially exploring the contribution of sound design and comparisons of narrated versus wordless formats. These should also be further investigated.

The lack of any observed effect in both the exposed and unexposed Do-nothing control groups does underscore the potential of short, animated video storytelling, as an approach, for boosting PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. It also highlights the absence of a priming effect in our study—an effect we expected to result from exposure to only the surveys (no videos) at T1. We anticipated that adults in our trial might reflect on their psychological state, just from having been surveyed about this at T1. We anticipated that the act of reflecting might somehow serve as an intervention and boost their outcomes at T2. This was not the case in our study population. The lack of a priming effect suggests that being surveyed about one’s psychological wellbeing may do little to improve the state of that wellbeing. These findings also underscore the potential for scalable media interventions, like short, animated storytelling videos, to help boost psychological resilience, including PsyCap, gratitude and happiness, among US adults. When this media is designed specifically for adults, it may be even more effective.

During the design of this study, we considered potential limitations and gave careful consideration to the fact that our participant population, (US residents, engaged online), may not perfectly represent our global target audience. The demographics of our participants reflect those of the platform on which the trial was delivered. In general, researchers using this platform have reported populations who are slightly younger and have more post-secondary education than the average adult in the US. However, the benefits of using an online platform like ProA greatly outweigh this limitation. These included a large participant pool, broad geographic distribution across the US, an efficient recruitment and data collection process and high participant retention40,41,42. Considering that our intervention would ultimately be delivered online, we also concluded that testing this intervention with a participant population, already engaged online, could ultimately be a strength rather than a limitation. A further limitation was the fact that we did not have the ability to analyze data for participants who were excluded early on because they failed to complete the initial survey. We do not expect there was an issue with selection bias since (a) the population included in the study is similar to the Prolific pool generally, (b) characteristics of the analytic sample were balanced across the four arms, and (c) participation/completion rates were similar across all arms.

Finally, the observation that the majority (63%) of participants were willing to voluntarily engage with the SAS videos, even after the trial had ended, suggests that SAS interventions could be valuable tools for the dissemination of health messages. This observation, supported by the fact that 30% of participants chose to voluntarily watch the entire SAS video, mirrors the findings of other engagement studies documenting high voluntary engagement with SAS interventions43. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the public is increasingly consuming their health information on social media platforms. This is especially true for populations who lack regular access to the healthcare system, like the elderly, adolescents, minorities and those facing language or literacy barriers44. In this study, the observation that demographic characteristics associated with watching the full video included older age, non-white ethnicity, lower income, and being a non-English-first-language speaker, further underscores the potential for scalable, SAS interventions to be used to engage hard-to-reach populations, who often face disparities in access to science-based health information45,46,47,48.

In this study, we investigated an innovative approach—short, animated storytelling (SAS)—to boosting PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. PsyCap, gratitude and happiness are psychological resources that have been linked to improved mental health outcomes—a priority in the current global environment, characterized as volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. This environment has precipitated a global mental health crisis, giving rise to an urgent need for rapidly scalable solutions. During the design of SAS interventions, animation serves as a primary means of enhancing accessibility and engagement for the public20,43,49. By leaning on effective approaches deployed by the entertainment industry, like animation and storytelling, SAS interventions are designed to make health communication interventions more engaging than didactic informational messages50. Boosting PsyCap, gratitude and happiness in the general public could serve as a powerful public health approach to offsetting the effects of the current mental health crisis. In recent years, we have witnessed (a) increasing consumption of short video content on social media, including health and wellness information-seeking and (b) the potential for this type of content to “go viral”, spreading rapidly across populations (including hard-to-reach populations) via spontaneous propagation51,52,53. As such, SAS presents an exciting emerging approach to the scalable dissemination of messages that could boost psychological wellbeing.

Boosting PsyCap is a preventive approach—aimed at helping individuals strengthen internal resources to help them thrive, rather than treating the symptoms of mental illness when they appear. As such, further exploration of interventions like SAS, that could promote psychological resilience in the general public, may powerfully support ongoing efforts to address the global mental health crisis.

Data availability

All data and the interventions developed for this study are available, in a fully anonymized format. These have been deposited on the Harvard University Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/SASVideos

Abbreviations

- PsyCap:

-

Psychological Capital

- SAS:

-

Short, animated storytelling

- APC:

-

Attention Placebo Control

- IASC:

-

Inter-Agency Standing Committee

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- TSE:

-

Trial Steering Committee

References

Luthans, F. & Broad, J. D. Positive psychological capital to help combat the mental health fallout from the pandemic and VUCA environment. Organ Dyn 51(2), 100817 (2022).

Reinert M, Fritze D, Nguyen T. The state of mental health in America 2024. (2024).

Dudasova, L., Prochazka, J., Vaculik, M. & Lorenz, T. Measuring psychological capital: Revision of the compound psychological capital scale (CPC-12). PLoS ONE 16(3), e0247114 (2021).

Lorenz, T., Hagitte, L. & Prasath, P. R. Validation of the revised Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12R) and its measurement invariance across the US and Germany. Front. Psychol. 13, 1075031 (2022).

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H., Pieterse, M. E., Walburg, J. A. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Efficacy of a multicomponent positive psychology self-help intervention: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 4(3), e4162 (2015).

Ho, H. C. & Chan, Y. C. Flourishing in the workplace: A one-year prospective study on the effects of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(2), 922 (2022).

Ho, H. C. & Chan, Y. C. The impact of psychological capital on well-being of social workers: A mixed-methods investigation. Soc. Work 67(3), 228–238 (2022).

Ho, H. C., Chui, O. S. & Chan, Y. C. When pandemic interferes with work: Psychological capital and mental health of social workers during COVID-19. Soc. Work 67(4), 311–320 (2022).

Krasikova, D. V., Lester, P. B. & Harms, P. D. Effects of psychological capital on mental health and substance abuse. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 22(3), 280–291 (2015).

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M. & Combs, G. M. Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. J. Org. Behav. 27(3), 387–393 (2006).

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B. & Patera, J. L. Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 7(2), 209–221 (2008).

Lupșa, D., Vîrga, D., Maricuțoiu, L. P. & Rusu, A. Increasing psychological capital: A pre-registered meta-analysis of controlled interventions. Appl. Psychol. 69(4), 1506–1556 (2020).

Dello Russo, S. & Stoykova, P. Psychological capital intervention (PCI): A replication and extension. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 26(3), 329–347 (2015).

Li, H.O.-Y., Bailey, A., Huynh, D. & Chan, J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: A pandemic of misinformation?. BMJ Glob. Health 5(5), e002604 (2020).

Liu, H. L. Vlog: A new communication practice in post pandemic. J. Audiens 2(2), 204–211 (2021).

Teichmann, L., Nossek, S., Bridgman, A., et al. Public health communication and engagement on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020).

Tsao, S.-F. et al. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. Lancet Digit. Health 3(3), e175–e194 (2021).

Adam, M., Bärnighausen, T. & McMahon, S. A. Design for extreme scalability: A wordless, globally scalable COVID-19 prevention animation for rapid public health communication. J. Global Health 10(1), 010343 (2020).

Vandormael, A. et al. The effect of a wordless, animated, social media video intervention on COVID-19 prevention: Online randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7(7), e29060 (2021).

Favaretti, C. et al. Participant engagement with a short, wordless, animated video on COVID-19 prevention: A multi-site randomized trial. Health Promot Int. 38, daab179 (2021).

Bartholomew, E., Iqbal, N. & Medvedev, O. Enhancing the assessment of gratitude in mindfulness research: A Rasch analysis of the 6-item gratitude questionnaire. Mindfulness 13(12), 3017–3027 (2022).

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 34(2), 139–150 (2006).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52(1), 1–26 (2001).

Committee I-AS. Adaptations of "My Hero is You!" - Country level Initiatives. WHO and UNICEF (2021).

Gray, J. Television teaching: Parody, The Simpsons, and media literacy education. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 22(3), 223–238 (2005).

Foulds, K. Co-viewing mass media to support children and parents’ emotional ABCs: An evaluation of Ahlan Simsim. Early Childhood Educ. J. 51(8), 1479–1488 (2023).

Gagné, N. & Franzen, L. How to run behavioural experiments online: Best practice suggestions for cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Swiss Psychol. Open 3(1), 1 (2023).

Lorenz-Spreen, P., Mønsted, B. M., Hövel, P. & Lehmann, S. Accelerating dynamics of collective attention. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 1759 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Chen, Z. J. & Ni, S. The security of being grateful: Gratitude promotes risk aversion in decision-making. J. Posit. Psychol. 15(3), 285–291 (2020).

Luthans, F. & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 4(1), 339–366 (2017).

Kawalya, C. et al. Psychological capital and happiness at the workplace: The mediating role of flow experience. Cogent Bus. Manag. 6(1), 1685060 (2019).

Kun, A. & Gadanecz, P. Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Curr. Psychol. 41(1), 185–199 (2022).

Pradhan, R. K., Jandu, K., Panda, M., Hati, L. & Mallick, M. In pursuit of happiness at work: exploring the role of psychological capital and coping in managing COVID-19 stress among Indian employees. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 16(6), 850–867 (2022).

Zhao, X., Liu, Q., Zhang, S., Li, T. & Hu, B. The impact of psychological capital and social capital on residents’ mental health and happiness during COVID-19: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 13, 962373 (2022).

Preston, A., Rew, L. & Young, C. C. A systematic scoping review of psychological capital related to mental health in youth. J. Sch. Nurs. 39(1), 72–86 (2023).

Turliuc, M. N. & Candel, O. S. The relationship between psychological capital and mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: A longitudinal mediation model. J. Health Psychol. 27(8), 1913–1925 (2022).

Youssef-Morgan, C. M. Psychological capital and mental health: Twenty-five years of progress. Organ Dyn. 53(4), 101081 (2024).

Hurling, R., Linley, P. A., Dovey, H., Maltby, J., & Wilkinson, J. Everyday happiness: Gifting and eating as everyday activities that influence general positive affect and discrete positive emotions. Int. J. Wellbeing 5(2) (2015).

Teixeira, P. J., Patrick, H. & Mata, J. Why We Eat What We Eat: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in Eating Behaviour Regulation (Wiley, 2011).

Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J. & Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 18(3), e0279720 (2023).

Palan, S. & Schitter, C. Prolific. ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 17, 22–27 (2018).

Turner, A. M., Engelsma, T., Taylor, J. O., Sharma, R. K., & Demiris, G. Recruiting older adult participants through crowdsourcing platforms: Mechanical Turk versus Prolific Academic. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2021. p. 1230 (2021).

Favaretti, C. et al. Participant engagement and reactance to a short, animated video about added sugars: Web-based randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8(1), e29669 (2022).

Neely, S., Eldredge, C. & Sanders, R. Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among American social networking site users: survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23(6), e29802 (2021).

Chen, K. A. & Kapadia, M. R. Health literacy disparities: Communication strategies to narrow the gap. Am. J. Surg. 223(6), 1046 (2021).

Freimuth, V. S. & Quinn, S. C. The contributions of health communication to eliminating health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 94(12), 2053–2055 (2004).

Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Chatterjee, J. S. & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. Narrative versus nonnarrative: The role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities. J. Commun. 63(1), 116–137 (2013).

Stormacq, C., Van den Broucke, S. & Wosinski, J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promot. Int. 34(5), e1–e17 (2019).

Greuel, M. et al. Parent engagement with a short, animated storytelling video aimed at reducing stigma towards transgender children and adolescents: A post-trial assessment of a randomized controlled trial. SSM-Ment. Health 7, 100410 (2025).

Adam, M., & Bärnighausen, T. Short animated storytelling: designing science-based global health messages for extreme scalability. npj Digit. Public Health. Accepted Oct. 1, 2025.

Chen, J. & Wang, Y. Social media use for health purposes: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23(5), e17917 (2021).

Hagg, E., Dahinten, V. S. & Currie, L. M. The emerging use of social media for health-related purposes in low and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 115, 92–105 (2018).

Merchant, R. M., South, E. C. & Lurie, N. Public health messaging in an era of social media. JAMA 325(3), 223–224 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the animators, Matt Torode, who animated the Intervention video, with scenes developed by CBA animation, under the direction of Chaz Bottoms. David Makadi Fwamba animated the APC video under the direction of MA. We wish to thank Misha Seeff, the teenage musician who composed the original soundtrack for the Intervention video and our collaborators at the IASC, Stanford Medicine, the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Medical School, UNICEF and the WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA created the intervention and APC videos, led the study design, obtained ethics approval from Stanford University, and led the writing of the protocol. JR led the data analysis, interpretation and presentation of results, as well as co-writing and editing the final manuscript. MG built the online experiment and implemented the study, helped to interpret the results, as well as editing the final manuscript. KN conducted the sample size calculation, led the building of the initial online surveys participated in the study design discussions and drafted the statistical analysis portions of the protocol together with co-author, Mirna Abd El Aziz. MAE conducted the sample size calculation, participated in the study design discussions, and drafted the statistical analysis portions of the protocol together with co-author, Kinh Nguyen. JG conducted the literature review, designed the study questionnaires, edited the protocol, and participated in the testing of the online experiment. CU participated extensively in the study design phase, edited the protocol and participated in the testing of the online experiment. AS supervised the study design, registered the trial, advised extensively on the statistical analysis plan, and edited the protocol paper. TB supervised the study design, advised extensively on the intervention development and statistical analysis plan, and edited the protocol paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests and all authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Multimedia appendix

SAS-PsyCap video: https://youtu.be/LRiWQfLvQjQ

SAS-APC video: https://youtu.be/QYqAbbifI9U

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, M., Rohr, J., Greuel, M. et al. Measuring the effect of short, animated storytelling videos to boost psychological capital in US adults: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 40326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26894-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26894-1