Abstract

Chest X-rays (CXRs) are widely used for diagnosing respiratory diseases, including the recent example of COVID-19. Supervised deep learning techniques can help detect cases faster and monitor disease progression. However, they are usually developed using coarser data annotations, which may insufficiently capture the heterogeneous disease portrait. We propose the pipeline called CIRCA (https://circa.aei.polsl.pl) for a CXR-based screening support system, developed using 6 diverse datasets. Our tool includes lung segmentation, quantitative assessment of data heterogeneity, and a hierarchical three-class decision system using a convolutional network and radiomic features. Lung segmentation showed an accuracy of ~ 94% in the validation and test sets, while classification accuracy was equal 86%, 83%, and 72% for normal, COVID-19, and other pneumonia classes in the independent test set. Three radiomically distinct subtypes were identified per class. In the hold-out set, the classification subtype-specific cross-dataset NPV ranged from 95 to 100%, with PPV from 86 to 100% for all subtypes except N3 (early stage or convalescent) and both C3 and P3 (probable co-occurrence of COVID-19). Using an independent test set gave similar results. The dataset-specific subtype proportions combined with various predictive qualities of subtypes partly explain the widely reported poor generalization of AI-based prediction systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its start in 2019 in China, a new respiratory tract disease COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has spread globally, causing numerous deaths worldwide. The present diagnosis criteria include clinical symptoms, epidemiological history, and laboratory testing; however, the final confirmation of this disease is based on the positive result of the antigenic test or time-consuming reverse-transcription-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) test1. Although the specificity of the latest tests is very high, the sensitivity is only moderate, leading to multiple false negatives, especially at an early stage of the disease. Also, in some regions of the world, the accessibility to a test is still limited.

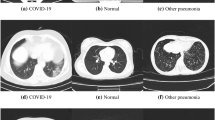

Medical imaging modalities, such as chest X-ray (CXR) and computed tomography (CT), could complement confirmatory tests to provide correct and rapid diagnosis, since lung abnormalities can be detected very early, even in asymptomatic patients2,3. The use of CT in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection showed high sensitivity4 but has limitations, e.g. transit of contagious patients to the radiology department, exposure of radiology staff to SARS-CoV-2, contamination of CT scanner, so it is primarily recommended to be used only in specific clinical situations, changing patient management decisions5,6. In contrast, chest radiography is easily accessible and may be done portably on a patient bed by a single radiographer. However, it shows lower sensitivity and specificity for the detection of lung lesions early in the disease by human experts, so efficient computer-based solutions are needed.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged healthcare systems around the globe to provide all patients with the required medical assistance and exceeded hospitals’ capacity, the importance of automated tools has risen, allowing for rapid and trustworthy diagnostics or screening support with minimal staff exposure to infection. Limited medical staff and equipment, lack of quick diagnostics, and thus the choice of the appropriate treatment options contributed to the bottleneck of effective healthcare management. Increased usage of AI tools assisting diagnostics has also highlighted the need for reliable data collection and the challenges resulting not specifically from COVID-19 itself, but from the specificity of medical datasets.

Although available data collections contain annotations provided by medical experts, label categorization can be insufficient to accurately reflect the heterogeneous picture of various diseases, including respiratory system disorders. Annotations may not adequately represent the diverse clinical outcomes, often reflected by typical or atypical symptoms, radiomic findings, or a mixture of several diseases or dysfunctions. Even though cases varying in clinical course, prognosis, or medical history and comorbidities should often be annotated identically or similarly on the radiomics bases, the computer-aided analysis can discover hidden differences affecting AI system decisions.

Limited data, especially in COVID-19 cases, made the task of creating a good prognostic model difficult7. From the start of the world pandemic in 2020, various deep learning techniques, mostly based on convolutional neural networks (CNN), were applied to detect the disease on CXRs with very high accuracy8,9,10,11. The proposed structures were highly complex, with a very large number of layers inadequate to the size of the datasets (only hundreds of COVID-19 cases were then provided). The classifiers were also trained to distinguish COVID-19 from normal lungs without considering other pneumonias that might show similar symptoms. When new datasets started to appear, it was found that the models worked very poorly on data not seen during model training (lack of model generalization), which eliminated them from the potential clinical use12,13,14. Multiple reasons for such behavior have been given, but the major ones are (i) low quality, small size, and reduced clinical diversity of training datasets; (ii) no evaluation of the model on an independent dataset; (iii) inefficient pre-processing of CXRs leading to the dependency of the model on confounding factors rather than medical pathology. For example, some studies used pediatric data to represent normal and pneumonia classes, so the models probably learned only age-related features to detect COVID-1914. When explainable AI tools, like saliency maps, were used to understand the models better, existing solutions incorrectly highlighted regions outside the lung area to be important for COVID-19 classification13.

Having taken into account the above-mentioned challenges, we propose the screening-support system, which not only considers the clinical diversity of the provided data but also allows for its quantitative assessment. Here, we demonstrate the potential application of the proposed system in a COVID-19 diagnosis example. Using the recommendations provided in the discussed publications, we developed a complete system with an online open-access platform called CIRCA to distinguish SARS-CoV-2 infection from other types of pneumonia and normal (healthy) cases on chest X-Ray images. With limited access to COVID-19 CXRs at the stage of network training, we required the lung segmentation to be done independently as the initial step in data analysis. For classification model building, we used diverse clinical datasets with images gathered at many hospitals from different world regions. The final classification was made using the aggregation of results of two deep learning models: (i) image-based; (ii) radiomic features-based. Finally, the model was validated on the independent clinical dataset, providing additional information about disease subtypes along with a patient diagnosis.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

We demonstrate how integrating image-based deep learning with radiomic analysis can enhance diagnostic accuracy.

-

We highlight the importance of addressing clinical data heterogeneity to ensure model generalization. Moreover, the characterization of disease heterogeneity is directly incorporated into our pipeline.

-

We discover disease subtypes using only unsupervised methods. However, our findings are further positively validated by clinicians, which proves their reliability.

-

Our solution could advance the clinical field, since it offers a deeper understanding of observed pulmonary disease subtypes. This could influence future biomedical research and clinical practices.

-

The proposed framework can be easily adapted to other complex medical conditions.

Results

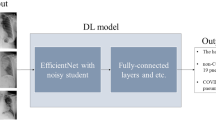

To construct a reliable and complete classification system, we used three different datasets (the clinical POLCOVID database, a collection of images found mostly online called COVIDx set, and the clinical AIforCovid database) and developed the multi-step procedure (Fig. 1). Before model building, we identified and removed low-quality images and duplicates. Then, we constructed a model to identify a clinically relevant region of the CXR that contains the lungs (Fig. 1a). Next, we divided each class (normal, pneumonia, and COVID-19) into subtypes using an unsupervised approach, which allowed us to construct a data division scheme. The entire classification pipeline (Fig. 1b) was evaluated during cross-validation and on hold-out sets. At last, the final classification model was tested on an independent test set.

Description of the subsequent steps of the CIRCA algorithm. (a) Lung region segmentation includes image pre-processing and deep learning-based segmentation. As a result, a lung mask is obtained. (b) The image classification procedure includes region-of-interest (ROI) definition, calculation of radiomic features, and classification using two models: radiomic-based and image-based. As a result, class prediction with class probability is given along with the estimated class subtype.

Lung region segmentation for ROI definition

The raw dataset constructed from 3 databases contained 21,317 CXR images (including images of 10,492 normal lungs, 6,720 pneumonia patients, and 4,105 COVID-19 patients). Most of the data were from the COVIDx dataset (n = 15,403), then from POLCOVID (n = 4,809) and AIforCovid (n = 1,105) databases. In COVIDx and POLCOVID, images from all three classes were provided in different proportions (COVIDx: 52% normal, 36% pneumonia, 12% COVID-19; POLCOVID: 50% normal, 24% pneumonia, 26% COVID-19), while in AIforCovid only CXRs from COVID-19 patients were given (Supplementary Table 1).

The CXR images contain the lung region, together with the heart, blood vessels, airways, and the bones of the chest and spine. However, only the lung region is important for COVID-19 detection; thus, we first constructed the lung region segmentation model. For this, we divided the model development data with manually extracted lung masks into three subsets: a training dataset of 1,844 images, a validation dataset of 200 images, and a test dataset of 250 images. CXRs from healthy donors and patients with various types of pulmonary diseases were distributed across training, validation, and test datasets to enhance generalization. The constructed and optimized U-Net network for lung segmentation demonstrated very high accuracy, as SDC was equal to 94.86% in the validation dataset and 93.36% in the testing dataset.

Inconsistent quality of CXR images

To improve the quality of the data, we first applied our super-resolution model to increase the resolution of all images lower than 512 × 512 (n = 1,694). Only 41% (n = 689) of low-resolution data were properly corrected, showing higher similarity to standard resolution images on UMAP-based data visualization (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We noticed that most of the images that the super-resolution model did not significantly improve have original resolutions lower than 300 × 300 pixels, come from the COVIDx database, and/or are from the COVID-19 class. Image upsampling using the proposed model increased the image resolution and quality without introducing any artifacts (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Next, we removed 159 images with decreased lung segmentation quality (segmentation quality score lower than 0.7259). Most low-quality images were from the pneumonia class and COVIDx dataset. We have found various problems with segmented images, including poor representation of a single lung or completely unsuccessful segmentation (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Finally, 20,153 images remained after data cleaning (including images from 10,474 normal lungs, 6,570 pneumonia patients, and 3,109 COVID-19 patients). Again, most of the data were from the COVIDx dataset (n = 14,261), then from POLCOVID (n = 4,793) and AIforCovid (n = 1,099) databases (Supplementary Table 2).

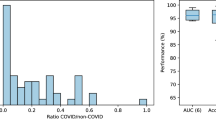

Heterogeneity of lung lesions

Using a clean dataset of 20,153 images, we constructed a 2D nUMAP plot on the features from the deep learning model to assess the homogeneity of the data (Fig. 2a). The density centers of the three classes are distant from each other in the plot, but the class-specific distributions are not separated. In each class, some images are located in the region dominated by the other classes (Supplementary Fig. 3) and hence are expected to get lower classification scores. One can observe at least three local concentration points within each class distribution. We used the 2D GMM model to divide class-specific data in an unsupervised manner into three subtypes named 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Fig. 2b). C1, P1, and N1 are the most different from the others and should present lung characteristics typical of each class, like consolidations and ground-glass opacities in COVID-19 or no changes in a normal class. Other subtypes might include mild symptoms of the disease (Supplementary Fig. 4). Additionally, the GMM-based subtype definition system was further verified using an independent test set (termed BIMCV).

CXR data heterogeneity. (a) The density plot in nUMAP coordinate space created by including images from 3 color-coded classes (Normal, Pneumonia, COVID-19) and three datasets: POLCOVID, COVIDx, and AIforCovid. (b) Results of grouping CXRs into three subtypes per class. NX represents subtype X from the Normal class, PX from the Pneumonia class, and CX from the COVID-19 class.

Development of a comprehensive classification system

We analyzed the frequency of image occurrence in subtypes of each class across all datasets and found significant differences (Supplementary Table 3), which may weigh heavily on the estimates of classification model performance indicators. Thus, we first randomly selected hold-out test cases, keeping a similar ratio between the classes, and then balanced the training sets using two other datasets (Fig. 3).

In the process of selecting images for the hold-out test set, we assumed 50 cases per class subtype and dataset. However, in some cases, there were not enough images in our database (e.g., P1 subtype in the POLCOVID dataset). In this situation, we increased the number of images in other subtypes from the same class to have a total of 150 test images per class and dataset (Supplementary Table 4). Finally, the hold-out test set consisted of 1,050 CXRs. We used Gaussian density functions from the 2D GMM model representing each subtype during the sampling process to provide similar data distributions in the test and train sets.

The remaining data were used for classification model training. The images from 2 other datasets were added to balance the training dataset: (i) CXRs of pneumonia patients from the NIH dataset; (ii) artificially created CXRs of COVID-19 patients using a GAN-based model. We assumed that CXRs from normal patients were the easiest to classify, so this class was not enriched with new data. As before, the selection of the added cases was controlled using the Gaussian density functions from the 2D GMM model, and mostly under-represented subtypes were extended. Finally, 2,061 images were added to the pneumonia class from the NIH database, controlling the age of patients, and 2,635 images to the COVID-19 class using the GAN-based model (Supplementary Table 5). Visual inspection of nUMAP plots proves the similarity of added images to the proper subtype and class (Supplementary Fig. 5). One can also notice that artificially created images look similar to real data (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Evaluation of CIRCA algorithm performance

The performance of the final model was evaluated in three ways: (i) using fivefold cross-validation during model training; (ii) on hold-out sets from 3 datasets used during training (POLCOVID, COVIDx, and AIforCovid); (iii) on the independent test set (BIMCV).

The average results from cross-validation show a very good performance of the CIRCA model (Table 1). The accuracy for all classes ranges from 91 to 93%, keeping slightly higher specificity than sensitivity. Also, NPV was higher than PPV for each class to guarantee a low rate of false negative cases, which is very important in the case of screening supporting systems. For the hold-out and independent test sets, due to the expected different quality of prediction for the identified subtypes, we present the quality assessment at the subtype level, with the final indicators at the class level calculated as weighted averages of partial assessments (Fig. 4, Table 2).

The balanced accuracy ranges across subtypes and datasets between 68% (subtype C3, POLCOVID) and 100% (N1 and P1, COVIDx) (Fig. 4a). As in cross-validation, NPV was higher than PPV, except for N1. For the typical subtypes (N1, P1, and C1), the best performance was obtained within each class, in terms of accuracy, PPV, and NPV (Table 2). As expected, the prediction for CXR images assigned to subtypes N3, P3, or C3 was much more challenging. However, in most cases, the predicted labels have been confused among these subtypes (e.g., an image from subtype C3 was classified as P3 or N3). The highest concordance15 between assigned and predicted classes was observed within the COVIDx dataset (kappa = 0.88, 95% CI 0.85 ÷ 0.92), with worse results for the POLCOVID data, but still at the substantial level (kappa = 0.71, 95% CI 0.67 ÷ 0.76).

The results were then summarised per class (Fig. 4b, Table 2). For normal and pneumonia classes, images from COVIDx were better classified than images from the POLCOVID dataset in terms of all performance measures. For the COVID-19 class, the results were similar between datasets, with high NPV (> 95%) and PPV (> 70%). The CIRCA system was also tested on the independent dataset BIMCV with more than 44,000 images. First, each image was labeled with the CIRCA subtype using the earlier-developed nUMAP projection. Then, the maximum GMM component membership probability rule (maximum a posteriori rule) was applied to identify the most probable subtype within the a priori defined class (Table 3). Finally, the image classification was performed and the confusion matrix was built (Supplementary Table 6).

The CIRCA model performed similarly to hold-out test sets on the independent BIMCV dataset for normal and COVID-19 class subtypes (except for C3, where significantly smaller PPV was noticed) (Table 4), with results being more consistent with POLCOVID than COVIDx dataset. Among the pneumonia patients, a decrease in sensitivity and PPV was noticed for all subtypes, but nUMAP-based visualization showed that BIMCV images of pneumonia patients were more similar to COVID-19 or normal cases than to our training pneumonia data (Fig. 5a,b).

Validation of the GMM-based subtype definition using radiologist-based COVID subgroups from an independent dataset

Images from COVID-19 patients in the BIMCV dataset were annotated by expert radiologists based on the visual inspection of CXR into four categories: (i) typical appearance; (ii) atypical appearance; (iii) indeterminate appearance; (iv) negative for pneumonia.

We compared unsupervised nUMAP-based subtype assignments with the BIMCV annotations (Table 5, Fig. 5c). The images from BIMCV typical category were mainly assigned to C2 and C1 subtypes (55.74% and 32.48%, respectively), while C2 and C3 subtypes were the most frequent for the atypical (60.68% and 30.23%) and indeterminate annotation (66.85% and 21.92%). Only 12 images from the negative for pneumonia group (0.69%) were assigned to the C1 subtype, with the C2 subtype dominating this category (61.94%). It is important to mention that during the CIRCA subtype assignment for BIMCV COVID-19 patients, the COVID-19 class was forced, and choosing another class was not allowed. The comparison study confirmed subtypes C1 and C2 as representing the most typical COVID-19 images at different disease development/recovery stages (C2 being less symptomatic than C1), while subtype C3 represents patients with a mixture of non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 pneumonia characteristics primarily.

When the CIRCA predictions are analyzed (Supplementary Table 7) for the negative for pneumonia group, subtype C2 (44.82%) is the leading decision, with N3 as the second most frequent (30.31%), which confirms our interpretation of the C2 subtype as representing, among others, low symptomatic COVID-19 patients. When the typical appearance group is considered, subtypes C2 and C1 were dominating decisions (51.08% and 30.30%, respectively), with an additional 182 classified as C3 (6.12%), which means an accuracy of 87.49% for that category. In the case of the atypical appearance group, the COVID-19 class was assigned to 69.13% of patients, while among the indeterminate appearance patients, only 48.47% were predicted as COVID-19. Among the misclassified patients, the P3 subtype was the most frequently assigned (230 of 372, 54.57% for typical appearance, 112 of 146, 76.71% for the atypical appearance group, and 129 of 257, 50.19% for indeterminate appearance). Seventy-six percent of COVID-19 patients wrongly classified by CIRCA as normal cases were in the negative for pneumonia category.

Comparison to COVID-Net algorithm

Among the models presented in the literature, we searched for an algorithm that fulfills the following assumptions: (i) it is a deep learning-based model; (ii) it is publicly available to download, and it is possible to re-train the model on a custom dataset; (iii) it performs classification into three classes including healthy individuals, COVID-19, and other pneumonia patients. COVID-Net is the only algorithm that meets all three assumptions. We re-trained the model using our training data and compared the efficiency of CIRCA to COVID-Net using our hold-out test set and an independent test set by calculating differences in several performance metrics on a class level (Table 6) and a subtype level (Supplementary Table 8). The overall accuracy of CIRCA was around 10% higher than COVID-Net for all classes. CIRCA gave higher sensitivity and NPV for normal and pneumonia classes, while for the COVID-19 class, higher specificity and PPV. The F1 index was also better in all cases (Table 6). Similar findings were made on the subtype level (Supplementary Table 8). Overall, the highest advantage was observed for N3, P3, and C3 subtypes, which consist of class borderline images. Similar results were obtained on the hold-out test set and independent BIMCV dataset, which proves a good generalization of the CIRCA model.

Computational time analysis

We measured the time of CIRCA and COVID-Net algorithms using a single thread of the standalone workstation (2.9 GHz 64-core CPU and NVidia V100 GPU) on 450 images from the POLCOVID dataset21. Additionally, we measured the CIRCA calculation time on the server currently hosting the service (https://circa.aei.polsl.pl/) on the same dataset. On the online server, the measurement includes the execution time of the algorithm with a binary classifier determining whether the given image is a lung X-ray, as well as the execution time of the classification for pulmonary disease, including the execution of the visualization algorithm. The reported times refer solely to the execution of the algorithms themselves and do not include any additional overhead or data loading. COVID-Net was faster than CIRCA with a median time of 0.019 s (Q1 = 0.017 s; Q3 = 0.023 s). CIRCA on a standalone workstation had a median time of 50.06 s (Q1 = 40.26 s; Q3 = 65.86 s), while on the online portal, a median time of 66.87 s (Q1 = 52.21 s; Q3 = 81.56 s).

Discussion

The main findings on medical images in patients with COVID-19 include ground-glass opacities, crazy-paving patterns, and areas of consolidation, which usually have bilateral and peripheral distribution and involve multiple lobes. Since the same patterns are often encountered in the pneumonia of other etiologies, including influenza pneumonia, SARS, and MERS pneumonia (as well as respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia, cytomegalovirus pneumonia, adenovirus pneumonia, atypical bacterial pneumonia—mycoplasma pneumonia, chlamydia pneumonia, pulmonary lung edema, and interstitial lung disease), the ability of radiologists to distinguish these diseases is limited, resulting in low specificity of CT (25%)2,4. The combination of two deep learning networks working in the sequential mode and a radiomic-based classifier leads to the achievement of effective lung segmentation and disease classification on X-rays, independently of the image quality. The developed CIRCA model worked well during training (fivefold cross-validation), on hold-out sets, and on the independent test set. Even though the classification accuracy was the highest for the COVIDx dataset, as in other solutions proposed in the literature, results on other clinical datasets were also very promising. The comparison study confirmed subtypes C1 and C2 as representing the most typical COVID-19 images at different disease development/recovery stages (C2 being less symptomatic than C1), while subtype C3 represents patients with a mixture of non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 pneumonia characteristics primarily.

X-ray images of patients with pneumonia from the BIMCV database were closer to the C3 subtype than P1 or P2 in the nUMAP plot (Fig. 5a). It was followed by the worse classification performance of the pneumonia category, but regardless of the original pneumonia nUMAP-based assigned subtype, the patients from BIMCV were classified mostly as the COVID-19 or pneumonia classes (41.43% and 37.00%, respectively). These images were annotated manually by trained physicians (27% of cases) or using a supervised method based on a recurrent neural network with an attention mechanism16, so some of them might be imprecise. Also, for C3 we got lower PPV than for C1 or C2 overall, so patients with even mild COVID-19-like symptoms or with the co-occurrence of non-COVID-19 pneumonia are more likely to be classified as C3 to decrease the chance of missing any COVID-19 patients for treatment.

Multiple deep learning models were developed to predict COVID-19 based on CXR images11,12,17. Most existing solutions used pre-trained, supervised learning architectures, without fine-tuning using a representative dataset of CXRs from COVID-19 patients. While transfer learning gives higher accuracy and faster training in most situations, using models trained on natural images is not the best solution for the analysis of medical images without extensive fine-tuning. Further, only some solutions could be run on independent data or be re-trained on a new dataset. COVID-Net algorithm resulted in the highest number of CXRs predicted as COVID-19 disease compared to CIRCA, both in the hold-out and independent test sets. Even though such model behavior slightly increased model sensitivity to COVID-19, the resulting NPV was similar, while PPV was much better for CIRCA. Thus, CIRCA shows greater implementation potential as a screening or diagnostic test.

We think that CIRCA could achieve better results than other approaches, mostly due to its complete framework. The first novel aspect is the quantitative assessment of data heterogeneity by the identification of radiomically distinct subtypes using nUMAP and GMM. This allowed us to account for diverse clinical outcomes and overcome the widely reported poor generalization of models trained on limited, undiverse datasets. It is a significant challenge, since it is very costly and labor-intensive to obtain fully labeled medical data18,19. Next, similar to LCGANT20, we trained a GAN model to generate synthetic images, specifically to enrich and balance the COVID-19 class and the underrepresented subtype. In both cases, classification performance was improved. Lastly, CIRCA utilizes a hybrid classification system that aggregates predictions from both image-based and radiomics-based deep learning models using a decision tree. In that way, CIRCA uses diverse features, which may improve robustness against noisy labels and low-quality data18.

To ensure the robustness and high generalization of the AI-based classification system, it is necessary, together with the development of the core model, to identify potential sources of disturbances and data heterogeneity and to implement actions aimed at their elimination. We focused on two major ones: the first relates to image resolution, while the second concentrates on proper lung segmentation. The CNN-based systems require predefined spatial resolution. As the image resolution varies, image standardization is usually performed at the data pre-processing stage. The most common approach performs image up- or downsampling to fit the required size. As it might result in artifacts being introduced, especially in the case of upsampling, we trained the super-resolution model to avoid such situations. The second crucial issue we address relates to lung tissue segmentation. We should stress that lung extraction is an essential step in the problem of image-based disease detection13. The first deep learning models for COVID-19 diagnosis made their prediction statement based on image artifacts outside lung area, lung size, or other confounders resulting from incorrect dataset usage. However, as pneumonia (both non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 related), especially at the advanced stage, disturbs the lung parenchyma radiomic characteristics, the segmentation model, properly delineating lung parenchyma for pneumonia patients also, is very important. As trained on relatively small data, the publicly available systems did not meet our expectations. Together with CIRCA core classification system, the above-mentioned pre-processing tools were developed and constitute the pivotal parts of the system.

Since the SARS-CoV-2 virus appeared very recently, the number of samples available to properly train the model was small in comparison to other classes (healthy, pneumonia). Also, other biases induced by incorrect use of existing datasets or not considering other confounders prevent the translation of prediction models into clinical practice7,14. Based on these findings, we gathered two clinically relevant datasets from different regions of the world, in addition to other real data and artificially generated CXRs of COVID-19 patients, to construct a large representative and well-balanced dataset for model training. Looking at the independent BIMCV dataset results, this solution increased the generalization of CIRCA model. Our dataset is publicly available and could be used by other researchers to train or validate upcoming models (www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn50877085)21.

Conclusions

The proposed CIRCA system, developed on a large representative dataset, allowed us to successfully distinguish COVID-19 patients from healthy individuals and other pneumonia cases with a class sensitivity of 71% and specificity above 95% for an independent clinically based test set. The obtained results also meet the requirements for medical screening tools by showing high NPV with a satisfactory PPV rate. The proposed method of the class subtype examination revealed the high clinical heterogeneity of the CXR data, which explained the results’ variability and the widely reported poor generalization of existing methods trained on limited datasets. Most COVID-19 patients wrongly classified by CIRCA as normal cases were annotated by radiologists as disease-negative CXRs. Finally, we developed and maintain the online service to provide easy and publicly available access to fast screening support tools. The proposed pipeline may serve to explore the heterogeneity and creation of diagnostics or screening-support systems for any clinically heterogeneous diseases, especially those involving the lung area.

Materials and methods

Super-resolution model development data

High-resolution radiographs gathered from the POLCOVID dataset21 were utilized for creating a supervised dataset of low- and high-resolution image pairs. As the POLCOVID dataset was created from radiographs originating from 15 different medical facilities, this made it a good fit for creating a diverse data source for the super-resolution problem. 2,912 high-resolution images were gathered, including 953 COVID-19,923 pneumonia, and 1,036 normal images. Each radiograph was downsampled to a 512 × 512 resolution as a standard resolution for web-scraped radiographs. Additionally, to be able to analyze very low-quality images, the images were also downsampled to 256 × 256 resolution.

Lung segmentation model development data

A dataset consisting of 2,294 publicly available CXRs was gathered. Among them, 1,124 images were collected from the National Institutes of Health—Clinical Center database22, 662 images from Shenzhen No.3 Hospital in Shenzhen, China23, 138 from the tuberculosis control program of the Department of Health and Human Services of Montgomery County, USA23, and 370 images were acquired from a public database of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou, China24. Lung mask annotation for each X-ray image was generated manually by the experts. The left atrium and left ventricle, together with the aortic knob, were excluded from the mask to ensure proper segmentation of lung tissue.

Classification model development data

The dataset used in the study was created with images from five different sources: our internal POLCOVID database21, COVIDx database17, AIforCovid database25, NIH pneumonia database22, and artificial images generated with Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Each image represented a chest X-ray of a patient with one of the three diagnoses: healthy (normal), pneumonia (not related to COVID-19), or COVID-19.

POLCOVID database contained 4,809 images from 15 medical facilities across Poland, with 2,426 healthy, 1,147 pneumonia, and 1,236 COVID-19 cases. COVIDx database contained 15,403 images with 8,066 normal, 5,573 pneumonia 1,764 COVID-19 cases. AIforCovid included 1,105 COVID-19 images from six Italian hospitals. NIH provided 2,061 pneumonia cases, while 2,635 images resembling COVID-19 cases were generated with GAN.

GAN architecture was composed of two models: a generator that produces new samples and a discriminator that tries to determine if a given sample is real or fake (generated). The generator had one fully connected (dense) and four transposed convolutional layers with the ReLU activation function. After each convolutional layer, a batch normalization with a momentum of 0.8 was used. Images were generated from latent vectors of 256 features. The discriminator was built of four convolutional layers and one fully connected output layer. All but the last layer’s activation function in the decoder was leaky ReLU with the alpha parameter of 0.2. The last layer’s activation function was sigmoid. The GAN model was trained for 1,500 epochs.

Independent test set

BIMCV COVID-19+26 and PadChest COVID-19−16 CXRs datasets served for the independent testing. Both datasets are available on the Valencian Region Medical ImageBank website. Only Posterior-Anterior (PA) and Anterior–Posterior (AP) projections were considered. COVID-19− cases with comorbidities other than pneumonia were removed from the dataset. Finally, the test set consisted of 35,857 healthy cases, 2,119 pneumonia cases, and 6,271 COVID-19 cases. The two datasets were connected and termed BIMCV in the analysis.

Data pre-processing

The raw CXR image undergoes a series of image processing procedures to properly prepare it for the key steps of analysis: lung area segmentation and classification. In the first stage, the images were standardized by analyzing the pixel intensity distribution, where outliers (determined based on calculated 0.0025 and 0.9975 percentiles as cut-off points) were removed, and the pixel values were transformed to the range of [0, 1]. These steps allow for uniformity of X-ray images obtained from different hospitals and the removal of some artifacts (e.g., white letters). After the standardization stage, each image was subjected to the contrast enhancement procedure to better expose the border of the lung area of patients with advanced lesions.

Data cleaning

The data used in the classification task were cleaned by removing: (i) too-small images; (ii) poor segmentation images. The classification model uses images after lung segmentation, so the image was considered too small and discarded if at least one of the lung region dimensions was less than 300 pixels. The procedure for finding images with poor segmentation quality was performed with the following steps. First, four measures quantifying the properties of the binary mask of the lung region were calculated: (i) eccentricity—the segmented lung was approximated by two ellipses (left and right modeled independently), and the smallest ratio of the distance between the foci of the fitted ellipse to the length of its major axis defines the lung eccentricity (range from 0 to 1; higher better); (ii) lung orientation—the mean of the angles between the x-axis and the major axis of the particular model ellipse (range from − 90 to 90; closer to 0 better); (iii) relative lung size—the smallest of the proportions of the number of pixels in the segmented lung parenchyma to the entire image (range from 0 to 1; higher better); (iv) solidity—the smallest of the proportions of the number of pixels in the segmented lung parenchyma related to the number of pixels in the convex hull of the segmented lung parenchyma (0–1; higher better). Next, the lung segmentation quality score was calculated as the arithmetic mean of these four properties and normalized to range from 0 to 1. The threshold for removing poor-quality images was found using the outlier detection method for skewed distributions27.

UMAP-based data visualization

To visualize relations between the data, a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)28 embedding was created using features extracted from the convolutional neural network29 with the umap-learn Python package. The method is termed nUMAP. For feature extraction using a neural network, segmented and processed radiographs were used. Based on the classification model architecture, a model that took into consideration all the data available in the database was trained. From the trained model, the pre-last layer containing a vector of 261 neural network features was extracted. Beforehand, the given features were pre-processed by removing features with zero variance and data scaling. Initial dimensionality reduction was performed using Principal Components Analysis (PCA), leaving components that explain 90% of the variance only. From the acquired feature space, the 2D UMAP embedding was created using the cosine distance metric.

Class subtype prediction

The two-dimensional Gaussian mixture model (GMM)30 was fitted to the nUMAP representation of the complete dataset. Initial conditions were set randomly, and the fitting procedure was repeated 100 times. The best model was found using the Bayesian information criterion. To avoid overfitting, the regularisation parameter was added with a value of 0.1. A constructed GMM model was also used to predict the class subtype of new unseen data from test datasets.

Image super-resolution model

The ESRGAN model31 was utilized as a base architecture for increasing the resolution of the low-resolution radiographs. The model was trained in a GAN framework, where two neural networks aim to minimize a loss function mimicking a zero-sum game. The loss function was the same as in the original paper. The model received the low-resolution representation of the radiograph and upsampled the image in a patch-wise manner. The input image was divided into patches of 50 × 50 resolution. The patches were fed into the neural network, and the resulting patches were formed into a high-resolution representation. The model was constructed from a series of blocks called Residual Dense Blocks (RDBs) designed to enhance the information flow between layers. The blocks contain residual connections between different abstraction layers, which facilitate the aggregation of global and local visual information.

Lung segmentation model

The U-Net architecture was chosen for the lung segmentation32. U-Net is divided into contracting and expansive paths. The contracting track is composed of five blocks of two unpadded convolutional layers (3 × 3 pixel kernel). All but the last block in the contracting path contains a max-pooling operation (2 × 2 pixels kernel, a stride of 2) to downsample the input image. The expansive path consists of four blocks of a transposed convolutional layer (2 × 2 pixel kernel, a stride of 2), two convolutional layers (3 × 3 pixel kernel), and a corresponding feature map from the contracting path. Scaled Exponential Linear Unit (SELU) was applied as an activation function to each but the last convolutional layer of the network, which was followed by a sigmoid activation function to generate a segmentation map for the input image. A 10% dropout33 was introduced after each max-pooling layer in the model to prevent the model from overfitting and to cover for model uncertainty. Additionally, the batch normalization34 was applied after each but the last convolution layer. Data augmentation was used to increase the final model’s generalization. Images from the training set were flipped horizontally, rotated by 0.1 radians in both directions, and zoomed by a factor of 0.1.

During network training, resized and padded input images and their corresponding segmentation maps were provided to train the network. Sorensen-Dice coefficient (SDC) served as a similarity measure and was used in the loss function minimized during the training. For an optimization algorithm of the network, a first-order gradient-based method called ADAM (adaptive learning rate optimization algorithm)35 was chosen as being robust for many non-convex optimization problems. Xavier uniform initialization was selected for the network’s parameter initialization36.

During the post-processing phase, the segmentation map produced by U-Net was further converted to ensure whole lung extraction and rejection of any non-lung regions. This phase can be decomposed into several steps. First, the system maintained the two largest segmentation regions and discarded any additional separate segmented regions. Next, the morphological operation of the opening was applied to smooth the contours of the lungs. The morphological operation of closing was applied to fill in any missing pixels inside the segmented region. Finally, the output image was a product of the post-processed mask and the input CXR. The generated lung segmentation undergoes further processing to remove any artifacts and improve its quality by adding a convex hull. After applying the lung mask, all pixels not belonging to the lung area were removed from the original image. The lung pixels were standardized, but the thresholds for outliers have been lowered to 0.0005 and 0.9995 percentiles. The next step was an ROI modification—both lungs were identified in the image and then placed at a minimum distance from each other. At the same time, the image was cropped on each side to the lung border to reduce the background participation in the classification process.

Every image was resized to 512 × 512 pixels while maintaining the aspect ratio to retain the shape of the chest. In cases of different dimensions, padding was added. Standardization was performed by mean subtracting per every pixel and scaling to unit variance. Mean and standard deviation have been saved as pre-processing parameters to perform analogous standardization to new, unseen data before feeding them to the network.

Image-based classification model

The pre-processed lung image was used to perform a diagnosis of normal, non-COVID-19 pneumonia, or COVID-19 class using the InceptionV3 convolution network37. This network consists of 17 convolution layers and one fully connected layer. The convolution layers were grouped into four blocks of 4 layers identical in structure. To accelerate network weight training, neuron weights were initialized using a pre-trained model on the ImageNet dataset. The parameters of the network model (such as batch size and the number of epochs) were selected in the process of cross-validation. Finally, the deep learning model was trained in 100 epochs, using a fivefold cross-validation scheme (5 × 100 epochs). ADAM algorithm was chosen again to solve the optimization problem in the network learning process. The dataset was artificially expanded using image transformations (rotation, pixel shift, reflection) before its use in each epoch.

Radiomics-based classification model

For radiomic features38 extractions, an original radiograph, and its lung segmentation were used. Patient lungs were analyzed independently within obtained by an even split of the segmented lung into three subregions, namely LL (Lower Lung), ML (Middle Lung), and UL (Upper Lung). From each subregion, radiomic features were calculated using pyradiomics Python package39 with a bandwidth of 0.01. As a result, a set of 261 radiomic features from the three lung subregions was obtained for each image. Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA-based η2 was used as a measure of the effect size, and only features with at least a small effect were considered crucial for the differentiation of three classes. It reduced the number of features to 200. To enlarge training data, data augmentation, defined as radiomic feature recalculation for bandwidth of 0.1, was applied, doubling the size of the training set.

The neural network was built of seven dense layers containing 1024, 512, 256, 128, 64, 32, and 3 neurons. All but the last layer had a ReLU activation function, and Nadam was used as the optimizer. The last layer activation was Softmax. After each layer, a dropout of 20% of randomly selected neurons was applied. The L2 regularisation penalty was applied to the kernels. During training, a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 128 were used. The optimal set of parameters was found through random hyperparameter tuning. Features were standardized to have a zero mean and a standard deviation of one.

Aggregation of multiple models’ predictions

The last step of the classification system was the integration of predictions from two CXR classification models. For each image, a vector containing predicted probabilities for each class membership from the image-based network and the radiomic-based network was created. A decision tree was used for the prediction aggregation. The model parameters were found through hyperparameter tuning. The decision tree had a maximum depth of 7, and the quality of a split was measured with the Gini impurity criterion. For each split, the model used three of the features. Each leaf node had a minimum of 100 samples. During the training, class weights were used: normal 0.1, pneumonia 0.3, and COVID-19 0.9. The final class decision was based on the maximum a posteriori rule.

CIRCA portal implementation

The CIRCA system was implemented and made publicly available at https://circa.aei.polsl.pl. The unregistered user can upload CXR and obtain the risk estimates for normal, other pneumonia, and COVID-19 diagnoses. The segmented lung and nUMAP with disease subtype prediction are also provided. For the registered users, the option for uploading the verified cases in both, jpg and DICOM standards is available. Scripts to run CIRCA locally are publicly available on GitHub: https://github.com/ZAEDPolSl/CIRCA.

Data availability

All datasets used in this study are publicly available (see Materials and methods section).

References

Mossa-Basha, M. et al. Radiology department preparedness for COVID-19: Radiology scientific expert review panel. Radiology296, E106–E112. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200988 (2020).

Ai, T. et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A report of 1014 cases. Radiology296, E32-e40. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200642 (2020).

Cellina, M., Martinenghi, C., Marino, P. & Oliva, G. COVID-19 pneumonia-ultrasound, radiographic, and computed tomography findings: A comprehensive pictorial essay. Emerg. Radiol.28, 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-021-01905-6 (2021).

Fang, Y. et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: Comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology296, E115-e117. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200432 (2020).

Ghosh, S. et al. Imaging algorithm for COVID-19: A practical approach. Clin. Imaging72, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.11.022 (2021).

Cieszanowski, A. et al. Indications for imaging studies in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients—Recommendations of the Polish Medical Society of Radiology. Pol. J. Radiol.87, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.5114/pjr.2022.113263 (2022).

Garcia Santa Cruz, B., Bossa, M. N., Sölter, J. & Husch, A. D. Public Covid-19 X-ray datasets and their impact on model bias—A systematic review of a significant problem. Med. Image Anal. 74, 102225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102225 (2021).

Wang, L., Lin, Z. Q. & Wong, A. COVID-Net: A tailored deep convolutional neural network design for detection of COVID-19 cases from chest X-ray images. Sci. Rep.10, 19549. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76550-z (2020).

Apostolopoulos, I. D., Aznaouridis, S. I. & Tzani, M. A. Extracting possibly representative COVID-19 biomarkers from X-ray images with deep learning approach and image data related to pulmonary diseases. J. Med. Biol. Eng.40, 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-020-00529-4 (2020).

Minaee, S., Kafieh, R., Sonka, M., Yazdani, S. & Soufi, G. J. Deep-COVID: Predicting COVID-19 from chest X-ray images using deep transfer learning. Med. Image Anal.65, 101794 (2020).

Laino, M. E. et al. The applications of artificial intelligence in chest imaging of COVID-19 patients: A literature review. Diagnostics11, 1317 (2021).

Roberts, M. et al. Common pitfalls and recommendations for using machine learning to detect and prognosticate for COVID-19 using chest radiographs and CT scans. Nat. Mach. Intell.3, 199–217 (2021).

DeGrave, A. J., Janizek, J. D. & Lee, S.-I. AI for radiographic COVID-19 detection selects shortcuts over signal. Nat. Mach. Intell.3, 610–619 (2021).

Ahmed, K. B., Goldgof, G. M., Paul, R., Goldgof, D. B. & Hall, L. O. Discovery of a generalization gap of convolutional neural networks on COVID-19 X-rays classification. IEEE Access9, 72970–72979 (2021).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics33, 159–174 (1977).

Bustos, A., Pertusa, A., Salinas, J. M. & de la Iglesia-Vayá, M. PadChest: A large chest X-ray image dataset with multi-label annotated reports. Med. Image Anal.66, 101797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2020.101797 (2020).

Chowdhury, M. E. H. et al. Can AI help in screening viral and COVID-19 pneumonia?. IEEE Access8, 132665–132676. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3010287 (2020).

Ren, Z., Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. Weakly supervised machine learning. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol.8, 549–580 (2023).

Ren, Z., Lan, Q., Zhang, Y. & Wang, S. Exploring simple triplet representation learning. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J.23, 1510–1521 (2024).

Ren, Z., Zhang, Y. & Wang, S. A hybrid framework for lung cancer classification. Electronics11, 1614 (2022).

Suwalska, A. et al. POLCOVID: A multicenter multiclass chest X-ray database (Poland, 2020–2021). Sci. Data10, 348 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. in 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 3462–3471.

Jaeger, S. et al. Two public chest X-ray datasets for computer-aided screening of pulmonary diseases. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg.4, 475–477. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.11.20 (2014).

Kermany, D. S. et al. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell172, 1122-1131.e1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.010 (2018).

Soda, P. et al. AIforCOVID: Predicting the clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 applying AI to chest-X-rays. An Italian multicentre study. Med. Image Anal. 74, 102216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102216 (2021).

Vayá, M. D. L. I. et al. Bimcv covid-19+: a large annotated dataset of rx and ct images from covid-19 patients. arXiv preprintarXiv:2006.01174 (2020).

Hubert, M. & Van der Veeken, S. Outlier detection for skewed data. J. Chemom.22, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/Cem.1123 (2008).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprintarXiv:1802.03426 (2018).

Socha, M., Suwalska, A., Prazuch, W., Marczyk, M. & Polanska, J. in Recent Advances in Computational Oncology and Personalised Medicine Vol. 1 (eds Z. Ostrowski & S. Bajkacz) 100–114 (Silesian University of Technology, 2021).

Marczyk, M. Mixture modeling of 2D gel electrophoresis spots enhances the performance of spot detection. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci.16, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNB.2017.2676725 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. in Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) workshops. 0–0.

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. in International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. 234–241 (Springer).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res.15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. in Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 37 (eds Bach Francis & Blei David) 448--456 (PMLR, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 2015).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. in 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (2015).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. in Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics. 249–256 (JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2818–2826.

Lambin, P. et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer48, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.036 (2012).

van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res.77, e104–e107. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-17-0339 (2017).

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Ministry of Education and Science, Poland grant no MNiSW/2/WFSN/2020, and Silesian University of Technology Grant no. 02/070/BK_25/0068 for Research Potential Support and Development. Calculations were carried out using GeCONiI infrastructure funded by NCBiR Grant no. POIG.02.03.01-24-099/13. AS, WP, and JT are holders of a European Union scholarship through the European Social Fund, Grants POWR.03.05.00-00-Z305 (AS, WP), and POWR.03.02.00-00-I029 (JT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JP and AC conceived the idea of the study. PF created the web service and database and gave technical support. JJ, KG, MSl, JW, TP, GP, MN, PFi, MP, RF, KS, GZ, BG, ES, AC, and POLCOVID Study Group collected the clinical and imaging data. WP, MS, and AS de-identified the data. MM, WP, MS, AS, and JT investigated image quality and data consistency. MM, WP, MS, AS, and JT performed data curation and validation. MM, WP, MS, AS, JT, and JP wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of all medical centers collaborating within the POLCOVID Study Group. The requirement for individual patient consent was waived as we removed all identifiable patient information. We complied with all relevant ethical regulations and guidelines. The Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland consented and financially supported the project for high-priority nationwide research on COVID-19 (Grant no MNiSW/2/WFSN/2020), of which data collection was an integral part.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prazuch, W., Suwalska, A., Socha, M. et al. CIRCA: comprehensible online system in support of chest X-rays-based screening by COVID-19 example. Sci Rep 15, 42732 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26895-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26895-0