Abstract

Achieving and maintaining optimal sagittal alignment is a key goal in cervical deformity correction, yet reliable intraoperative tools to guide alignment remain limited. The C2 slope (C2S) is a simple parameter that reflects the relationship between the upper thoracic and cervical spine and has been associated with health-related quality of life. However, its role as an intraoperative guide for alignment correction has not been fully explored. This study analyzed 45 patients with cervical deformity who underwent correction with at least 2-year follow-up. Intraoperative lateral radiographs were obtained before final construct assembly, and C2S was actively measured and used to guide correction through surgical adjustments. Radiographic parameters—including C2S, C2–7 lordosis, T1 slope, T1 slope minus cervical lordosis (T1S–CL), and sagittal vertical axis—were evaluated preoperatively, intraoperatively, and during follow-up. Clinical outcomes included visual analog scale for neck and arm pain, Neck Disability Index, Japanese Orthopedic Association score, and EQ-5D. Both C2S and T1S–CL demonstrated significant correction which remained stable during follow-up. Final C2S and T1S–CL also showed significant correlations with clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that intraoperative C2 slope may serve as a practical reference for guiding alignment correction and could contribute to favorable radiographic and clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical spine deformity (CSD) can lead to substantial impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) by causing pain, functional disability, loss of horizontal gaze, and neurologic deficits1,2. Surgical correction is often associated with meaningful improvement in these symptoms3,4. As a result, recent efforts have increasingly focused on refining the assessment, classification, and management of CSD5,6,7. In particular, numerous radiographic parameters have been proposed to quantify cervical alignment and guide treatment planning8.

Among the proposed parameters, the C2 slope (C2S), T1 slope minus cervical lordosis (T1S-CL), and cervical sagittal vertical axis (SVA), have demonstrated correlations with HRQoL in patients with CSD9,10,11,12. Accordingly, optimal correction is often reflected by improvements in these metrics. However, CSD remains complex and challenging condition to manage, particularly in determining the degree of alignment correction required8. Only recently have studies begun to define radiographic targets for ideal postoperative alignment9,10,13,14. Despite these advances, reliable intraoperative indicators to guide real-time surgical decision-making remain limited.

Given these challenges, we hypothesized that intraoperative measurement of C2S could provide meaningful intraoperative feedback and help predict postoperative alignment. This study aimed to evaluate the utility of intraoperative C2S as a radiographic parameter for guiding alignment correction in CSD surgery.

Material and methods

Patient selection

This retrospective study was approved by the Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval number: 9-2023-0148). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board.

We identified patients aged ≥ 18 years who underwent posterior or combined anterior–posterior cervical fusion spanning ≥ 3 levels between 2014 and 2020. Exclusion criteria included follow-up < 2 years, insufficient radiographic or clinical data, and surgery for trauma, tumor, infection, or cerebral palsy. Patients were also excluded if they had a history of prior cervical spine surgery, underwent additional spinal surgery during the follow-up period, or presented with concomitant upper cervical pathology.

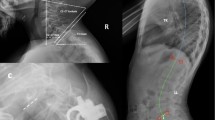

Among eligible cases, patients were included if they met radiographic criteria for cervical deformity, defined by at least one of the following: anteroposterior Cobb angle > 10°, C2–7 kyphosis > 10°, C2–7 sagittal vertical axis > 40 mm, or chin-brow vertical angle > 25°14,15 (Fig. 1).

Demographics and surgical data

Baseline demographic data were collected, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking and alcohol use, presence of osteoporosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, and symptom duration. Surgical and perioperative variables—such as estimated blood loss (EBL), number of fused levels, operative duration, surgical approach, length of hospital stay, and follow-up duration—were also recorded.

Radiographic parameters

Radiographic evaluation included full-length standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral films, as well as cervical spine radiographs in neutral, flexion, and extension positions, obtained preoperatively and postoperatively. Intraoperative imaging consisted of lateral cervical radiographs. The following sagittal alignment parameters were measured at each time point: C2 slope (C2S), T1 slope (T1S), C2–7 lordosis (CL), T1 slope minus C2–7 lordosis (T1S–CL), and C2–7 sagittal vertical axis (SVA).

Intraoperative lateral radiographs were acquired with patients in the prone position on a Jackson table (Modular Table System, Mizuho OSI, CA, USA) set to a precise 10° reverse Trendelenburg angle. The imaging cassette was mounted in a frame parallel to the floor, ensuring that the image plane remained orthogonal to gravity. Patients’ hips and knees were fully extended, and the feet were secured against a footboard fixed to the table, keeping the body axis parallel to the tabletop. Images were rotated 90° and uploaded to the picture archiving and communication system (PACS; Enterprise Web ver. 3.0, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). As a result of this consistent setup, intraoperative measurements of C2S and T1S were 10° greater than upright images. Intraoperative C2–7 SVA was similarly affected by this positional deviation (Fig. 2). This positioning protocol was strictly standardized and applied to all patients throughout the procedure.

All patients wore a rigid cervical collar postoperatively. Only radiographs obtained after collar removal—typically at 3 months—were included in the final analysis.

C2S as an intraoperative alignment guide

During surgery, a lateral cervical radiograph was obtained prior to final rod assembly and graft placement. The C2 slope (C2S) measured on this intraoperative image served as a real-time reference for achieving the desired sagittal alignment. Based on previous literature, an ideal postoperative C2S is considered to be < 20°, and preferably < 10°10,13. Given the known 10° overestimation caused by the reverse Trendelenburg setup, a target intraoperative C2S of approximately 0° or slightly below was used. To achieve this alignment, adjustments were made by increasing lordosis—through cervical extension and/or cantilever correction—or by decreasing lordosis using the opposite maneuvers.

Clinical outcome measures

Clinical outcome measures were collected at baseline and during follow-up and included the visual analog scale (VAS) for neck and arm pain, Neck Disability Index (NDI)16, Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score17, patient-reported subjective improvement rate (IR, %), and EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D). The total NDI score was converted into a percentage to account for non-drivers.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, radiographic, and clinical outcome variables are reported as means with standard deviations (± SD) or as frequencies and percentages, as appropriate. After testing for normality, paired t-tests, repeated-measures ANOVA with post hoc comparisons, and Pearson correlation analyses were performed. Subgroup comparisons according to achievement of the intraoperative C2S target were performed using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Cohort overview

Following application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 45 patients were included in the final analysis. The mean age was 60.1 ± 9.8 years, and 26 patients (57.8%) were male. The average BM) was 25.7 ± 3.7 kg/m2. Most patients were non-smokers (n = 34, 75.6%) and non-drinkers (n = 33, 73.3%). Osteoporosis was present in 2 patients (4.4%). The mean CCI was 2.0 ± 1.3, and 19 patients (42.2%) were classified as ASA physical status class III. The mean duration of symptoms prior to surgery was 11.0 ± 15.1 months. None of the patients presented with isolated coronal deformity; all who met the coronal Cobb angle criterion also demonstrated concomitant sagittal deformity.

Surgical data revealed a mean fusion length of 4.3 ± 0.8 levels (range, 3–7), with an average EBL of 490 ± 341.7 mL and mean operative time of 250.3 ± 144.0 min. Two patients (4.4%) underwent posterior-only fusion, while the remainder received combined anterior–posterior procedures. The mean hospital length of stay was 12.4 ± 5.7 days, and the mean follow-up duration was 35.9 ± 15.0 months (Table 1).

Clinical outcomes following deformity correction

Baseline clinical outcome measures included a mean neck pain VAS of 6.3 ± 2.2, arm pain VAS of 6.3 ± 1.0, NDI of 44.7 ± 16.9%, JOA score of 11.6 ± 2.7, and EQ-5D VAS of 45.1 ± 9.9. At final follow-up, all clinical outcomes demonstrated statistically significant improvement. Neck pain VAS improved to 1.1 ± 1.7, arm pain VAS to 0.6 ± 1.3, NDI to 21.6 ± 15.0%, JOA score to 15.9 ± 1.8, and EQ-5D VAS to 80.6 ± 15.4. The mean JOA recovery rate was 77.6 ± 31.9% (Table 2).

Radiographic parameters over time

Radiographic measurements over time are summarized in Table 3 and Figs. 3–7.

C2S decreased significantly from 19.9 ± 7.2° preoperatively to 8.8 ± 6.4° intraoperatively (p < 0.001). A significant increase was observed between the intraoperative and 3-month postoperative periods (11.6 ± 6.8°, p = 0.002), with no further significant change between 3 months and final follow-up (12.4 ± 7.1°, p = 0.951) (Fig. 3).

T1S increased significantly from 18.4 ± 10.2° preoperatively to 25.4 ± 8.8° intraoperatively (p < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the intraoperative and 3-month periods (26.7 ± 6.6°, p = 0.280); however, a significant decrease was noted between 3 months and final follow-up (24.8 ± 6.2°, p = 0.010) (Fig. 4).

CL improved significantly from − 3.6 ± 14.6° to 16.8 ± 10.1° intraoperatively (p < 0.001). No significant change occurred between the intraoperative and 3-month measurements (15.3 ± 9.1°, p = 0.897), while a significant decrease was observed between 3 months and final follow-up (13.1 ± 8.6°, p = 0.006) (Fig. 5).

T1S–CL decreased significantly from 21.9 ± 9.0° preoperatively to 8.2 ± 6.5° intraoperatively (p < 0.001), followed by a significant increase at 3 months (11.1 ± 6.5°, p = 0.001). However, no further significant change was noted at final follow-up (11.5 ± 6.9°, p = 0.99) (Fig. 6).

C2–7 SVA did not demonstrate significant differences across any time points (Fig. 7).

Correlation between radiographic parameters and clinical outcomes

Final follow-up C2S values demonstrated significant correlations with several clinical outcome measures, including neck pain VAS (R = 0.514, p < 0.001), NDI (R = 0.380, p = 0.010), JOA score (R = − 0.301, p = 0.044), JOA recovery rate (R = − 0.395, p = 0.007), EQ-5D index (R = − 0.342, p = 0.026), EQ-5D VAS (R = − 0.338, p = 0.025), and improvement rate (IR) (R = − 0.336, p = 0.024).

T1S–CL was also significantly associated with neck pain VAS (R = 0.479, p = 0.001), NDI (R = 0.393, p = 0.008), JOA score (R = − 0.314, p = 0.036), JOA recovery rate (R = − 0.414, p = 0.005), EQ-5D index (R = − 0.329, p = 0.033), EQ-5D VAS (R = − 0.345, p = 0.022), and IR (R = –0.361, p = 0.015).

CL correlated with neck pain VAS (R = − 0.397, p = 0.007), EQ-5D VAS (R = 0.345, p = 0.022), and IR (R = 0.341, p = 0.022). In contrast, neither T1S nor C2–7 SVA showed significant correlations with any clinical outcome parameters (Table 4).

Subgroup analysis

Patients who achieved an intraoperative C2 slope ≤ 0° had significantly lower C2 slope, greater C2–7 lordosis, and reduced T1S–CL mismatch at final follow-up. Clinically, this group reported lower neck pain and a higher proportion achieved JOA recovery MCID. No significant differences were observed in NDI, NDI MCID achievement, and EQ–5D VAS (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that following CSD correction, C2 slope (C2S) and T1 slope minus cervical lordosis (T1S–CL) improved significantly and remained stable throughout follow-up. In contrast, while T1 slope (T1S) and C2–7 lordosis (CL) also improved postoperatively, their correction was not maintained over time. Similar longitudinal stability of C2S and T1S–CL has been reported in asymptomatic populations18,19. In the present surgical cohort, this preservation may be partially attributed to the patients’ capacity to maintain horizontal gaze post-correction.

Both parameters showed significant correlations with HRQoL measures at final follow-up. Given that C2S is a mathematical approximation of T1S–CL, it may serve as a practical surrogate intraoperatively11. The T1S–CL represents the balance between the upper thoracic and cervical spine, which is known to influence neutral head posture and line of sight9,20. Imbalances in this relationship may lead to compensatory muscle overuse, contributing to neck pain and disability—reflected in this study’s correlations between these parameters and both neck pain VAS and NDI scores. Consistent with prior research, C2S and T1S–CL were also significantly associated with JOA scores and JOA recovery rates10,11. In particular, our subgroup analysis demonstrated that achieving an intraoperative C2S ≤ 0° was associated with a higher likelihood of achieving the MCID for JOA recovery. Cervical malalignment may cause spinal cord stretch and draping over ventral pathology, leading to ischemia, increased cord tension, and subsequent neurological decline21,22. Therefore, adequate sagittal correction—as reflected by achieving an appropriate C2S—may contribute not only to sagittal balance but also to neurological recovery in patients with cervical myelopathy. Although not directly evaluated here, optimizing C2S may also help mitigate complications such as distal junctional failure13.

Taken together, the reproducibility of C2S over time and its significant association with patient-reported outcomes support its utility as a reliable intraoperative alignment guide. In addition, our subgroup analysis revealed that achieving an intraoperative C2S ≤ 0° was associated with more favorable sagittal alignment and improved clinical outcomes at final follow-up. Given the limited sample size, these findings should be regarded as exploratory, but they suggest that targeting C2S may serve as a practical intraoperative reference.

Surgeons employ various methods to assess spinal alignment intraoperatively. This study focused on using the C2S as a guide due to its potential advantages over alternative parameters. C2S requires only a single angular measurement, simplifying intraoperative assessment and minimizing interobserver variability10,11. Its simplicity and ease of use make it particularly well-suited to the surgical setting, where precise calculations and complex measurements may be impractical. Moreover, the C2 vertebra is consistently visible on cervical spine radiographs, enhancing the reliability of C2S compared to other parameters—such as T1S or CL—that depend on visualization of the lower cervical spine or cervicothoracic junction, which are often obscured in plain radiographs23,24,25.

Some surgeons use the C2–7 SVA to guide intraoperative alignment, as values less than 40 mm have been associated with favorable outcomes12. However, SVA is a linear measurement that requires radiographic calibration, which can vary considerably between imaging setups. This variability makes linear parameters less practical for intraoperative use compared to angular measurements26. Cervical deformity correction often necessitates multilevel fusion, typically performed via posterior or combined anterior–posterior approaches. During posterior procedures, patients are commonly positioned prone in a reverse Trendelenburg orientation to reduce intraocular pressure and intraoperative bleeding4,27. This positioning alters the body axis relative to the imaging plane, complicating the accuracy of C2–7 SVA measurement. In contrast, angular parameters such as C2S are less susceptible to these positional distortions and may offer a more reliable alternative in the operative setting. Moreover, although a C2–7 SVA < 40 mm has been widely cited as a radiographic goal, prior studies have demonstrated that this threshold corresponds to a T1S–CL and C2S of approximately 20°10,28. Thus, while intraoperative SVA measurements may be difficult to standardize, C2S offers an alternative that aligns closely with established SVA targets.

In this study, the reverse Trendelenburg angle was standardized at 10°, resulting in a 10° overestimation of slope angles on intraoperative radiographs. Based on prior studies recommending a final C2S of less than 10°13, the intraoperative target was set to a “level” C2—defined as a C2S of 0°—or slightly negative. This approach provided a simple and reproducible visual reference to guide real-time assessment and determine the extent of alignment correction required.

An alternative method employed by some surgeons is the “occiput-to-back” technique, which involves aligning the patient’s occiput with the posterior thorax while prone. Although this method may help assess translational alignment, it does not account for angular deformity and lacks validated correlation with sagittal balance. Its clinical reliability remains uncertain due to a lack of supporting evidence in the literature. In contrast, C2S has been shown to correlate with both T1S–CL and C2–7 SVA, providing a more evidence-based and quantifiable intraoperative reference.

This study has several limitations. Although data collection followed a prospective protocol, the retrospective nature of the analysis may not have been ideal for evaluating intraoperative decision-making. Final radiographs were not consistently acquired in the same reverse Trendelenburg position due to intraoperative factors such as hypotension or prolonged surgical time. As a result, post-assembly radiographs were excluded from analysis, which may have contributed to the observed variation in C2S between intraoperative imaging and the 3-month follow-up. Nevertheless, the authors believe that using radiographs obtained prior to final construct assembly more accurately reflects alignment adjustments made during surgery.

The relatively small sample size was a consequence of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria designed to minimize bias. In addition, the relative rarity of cervical deformity further limited the patient population. As a result, this constraint substantially restricted our ability to classify deformity subtypes or perform stratified analyses. Larger, preferably multi-institutional studies will be necessary to determine whether intraoperative use of the C2S is broadly applicable across different cervical deformity patterns. Accordingly, our findings should be regarded as preliminary evidence that highlights the potential utility of intraoperative C2S as a practical surgical guide.

Another limitation is that our cohort may not have fully represented the most severe forms of cervical deformity. Although the definition of “severity” remains inconsistent in the existing literature, it is possible that some of the most extreme cases were not included. Nevertheless, the mean preoperative C2S (19.9°) and T1S–CL (21.9°) corresponded to high modifier scores within the Ames–ISSG classification7, indicating at least moderate to markedly abnormal values in our cohort. Even so, the possible absence of the most severe deformities suggests that our findings should be considered preliminary, and validation in larger, more diverse cohorts will be necessary.

The limited sample size and selection of patients may have contributed to the lack of significant changes in C2–7 SVA across follow-up. However, a prospective multicenter study reported that only one-third of adult cervical deformity patients demonstrated improvement in C2–7 SVA modifier grade following surgery, whereas the majority showed no change29. Our findings appear consistent with these results.

Additionally, the lack of long cassette radiographs in the operating room precluded measurement of global sagittal alignment parameters, such as the T1 pelvic angle or cervical-thoracic pelvic angle. Future studies incorporating advanced intraoperative imaging may help overcome this limitation.

Despite these constraints, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to describe the intraoperative application of C2S as an alignment guide and to demonstrate its postoperative preservation over a minimum two-year follow-up period.

Conclusions

C2S is a simple and reproducible radiographic parameter that may serve as a practical and reliable intraoperative guide during cervical deformity correction. Intraoperative correction of C2S was maintained over time and demonstrated significant associations with radiographic restoration and clinical improvement. These findings suggest that intraoperative C2S has potential as a useful real-time reference for optimizing sagittal alignment.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the inclusion of patient clinical information, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Scheer, J. K. et al. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: A review. J. Neurosurg. Spine 19, 141–159. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838 (2013).

Smith, J. S. et al. The health impact of adult cervical deformity in patients presenting for surgical treatment: Comparison to united states population norms and chronic disease states based on the EuroQuol-5 dimensions questionnaire. Neurosurgery 80, 716–725. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx028 (2017).

Passias, P. G. et al. The relationship between improvements in myelopathy and sagittal realignment in cervical deformity surgery outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 43, 1117–1124. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000002610 (2018).

Tan, L. A., Riew, K. D. & Traynelis, V. C. Cervical spine deformity-part 3: Posterior techniques, clinical outcome, and complications. Neurosurgery 81, 893–898. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx477 (2017).

Kim, H. J. et al. The morphology of cervical deformities: A two-step cluster analysis to identify cervical deformity patterns. J. Neurosurg. Spine https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.9.SPINE19730 (2019).

Koller, H. et al. Characteristics of deformity surgery in patients with severe and rigid cervical kyphosis (CK): Results of the CSRS-Europe multi-centre study project. Eur. Spine J. 28, 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5835-2 (2019).

Ames, C. P. et al. Reliability assessment of a novel cervical spine deformity classification system. J. Neurosurg. Spine 23, 673–683. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.12.SPINE14780 (2015).

Lee, S. H., Hyun, S. J. & Jain, A. Cervical sagittal alignment: Literature review and future directions. Neurospine 17, 478–496. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040392.196 (2020).

Hyun, S. J., Kim, K. J., Jahng, T. A. & Kim, H. J. Clinical impact of T1 slope minus cervical lordosis after multilevel posterior cervical fusion surgery: A minimum 2-year follow up data. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 42, 1859–1864. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002250 (2017).

Kim, N. et al. Clinical significance of the C2 slope after multilevel cervical spine fusion. J. Neurosurg. Spine 38, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.6.SPINE22588 (2023).

Protopsaltis, T. S. et al. The importance of C2 slope, a singular marker of cervical deformity, correlates with patient-reported outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 45, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003214 (2020).

Tang, J. A. et al. The impact of standing regional cervical sagittal alignment on outcomes in posterior cervical fusion surgery. Neurosurgery 71, 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826100c9 (2012) (discussion 669).

Passfall, L. et al. Do the newly proposed realignment targets for C2 and T1 slope bridge the gap between radiographic and clinical success in corrective surgery for adult cervical deformity?. J. Neurosurg. Spine https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.2.SPINE211576 (2022).

Virk, S. et al. Intraoperative alignment goals for distinctive sagittal morphotypes of severe cervical deformity to achieve optimal improvements in health-related quality of life measures. Spine J 20, 1267–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2020.03.014 (2020).

Louie, P. K. et al. Classification system for cervical spine deformity morphology: A validation study. J. Neurosurg. Spine 37, 865–873. https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.5.SPINE211537 (2022).

Vernon, H. The neck disability index: State-of-the-art, 1991–2008. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 31, 491–502 (2008).

Yonenobu, K., Abumi, K., Nagata, K., Taketomi, E. & Ueyama, K. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the Japanese orthopaedic association scoring system for evaluation of cervical compression myelopathy. Spine 26, 1890–1894 (2001).

Iorio, J. et al. The effect of aging on cervical parameters in a normative North American population. Global Spine J. 8, 709–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218765400 (2018).

Tang, R., Ye, I. B., Cheung, Z. B., Kim, J. S. & Cho, S. K. Age-related changes in cervical sagittal alignment: A radiographic analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 44, E1144–E1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003082 (2019).

Staub, B. N. et al. Cervical mismatch: The normative value of T1 slope minus cervical lordosis and its ability to predict ideal cervical lordosis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 30, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.5.SPINE171232 (2018).

Ames, C. P. et al. Cervical radiographical alignment: comprehensive assessment techniques and potential importance in cervical myelopathy. Spine 38, S149–S160 (2013).

Shimizu, K. et al. Spinal kyphosis causes demyelination and neuronal loss in the spinal cord: a new model of kyphotic deformity using juvenile Japanese small game fowls. Spine 30, 2388–2392 (2005).

Truong, V. T. et al. Enhanced visualization of the cervical vertebra during intraoperative fluoroscopy using a shoulder traction device. Asian Spine J. 14, 502–506. https://doi.org/10.31616/asj.2019.0255 (2020).

Marques, C. et al. Accuracy and reliability of X-ray measurements in the cervical spine. Asian Spine J. 14, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.31616/asj.2019.0069 (2020).

Zhang, J., Buser, Z., Abedi, A., Dong, X. & Wang, J. C. Can C2–6 cobb angle replace C2–7 cobb angle?: An analysis of cervical kinetic magnetic resonance images and X-rays. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 44, 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000002795 (2019).

Protopsaltis, T. et al. TheT1 pelvic angle, a novel radiographic measure of global sagittal deformity, accounts for both spinal inclination and pelvic tilt and correlates with health-related quality of life. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 96, 1631–1640. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.01459 (2014).

Carey, T. W., Shaw, K. A., Weber, M. L. & DeVine, J. G. Effect of the degree of reverse Trendelenburg position on intraocular pressure during prone spine surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 14, 2118–2126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.12.025 (2014).

Hyun, S. J., Han, S., Kim, K. J., Jahng, T. A. & Kim, H. J. Assessment of T1 slope minus cervical lordosis and C2–7 sagittal vertical axis criteria of a cervical spine deformity classification system using long-term follow-up data after multilevel posterior cervical fusion surgery. Oper. Neurosurg. 16, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy055 (2019).

Passias, P. G. et al. Characterizing adult cervical deformity and disability based on existing cervical and adult deformity classification schemes at presentation and following correction. Neurosurgery 82, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx175 (2018).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Nothing to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. and K.-S.S. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. Data collection and processing were performed by N.K., K.-S.S., J.-W.K., S.-R.P., J.S., and B.H.L. Data analysis was conducted by N.K., K.-S.S., S.-Y.P., J.-O.P., S.-H.M., and H.-S.K. Manuscript drafting and revision were carried out by N.K., K.-S.S., J.-W.K., S.-Y.P., J.-O.P., S.-H.M., and H.-S.K. All authors contributed to the supervision of the study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval number: 9–2023-0148). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. In light of the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, N., Suk, KS., Kwon, JW. et al. Evaluating intraoperative C2 slope as a radiographic guide for cervical deformity correction. Sci Rep 15, 43067 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26914-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26914-0