Abstract

Job-related exposures play a significant, often disregarded, role in respiratory outcome development. Evaluating how this exposure impacts the incidence of respiratory illnesses in the general population is crucial for prevention and occupational health surveillance. A total of 823 workers/ex-workers from Pisa (Italy) participated in 2 surveys over 18 years (PI2 1991-93, PI3 2009-11). Health status, occupational sector, and individual risk factors were assessed through a questionnaire; airway obstruction (AO) by spirometry. Exposure was defined as working for at least 3 months in a sector at risk for respiratory diseases at PI2. Cumulative incidence was calculated as “incident cases/population at risk”. The relationship between outcome incidence and occupational exposure was assessed through multiple logistic regressions adjusted for baseline (PI2) risk factors. Analysis of covariance estimated the effect of occupational exposure on changes in FEV1/FVC over time. Associations were found among occupational exposure and outcome incidence: agriculture for usual cough/phlegm (OR 2.16, 90% CI 1.17–3.99) and AO ( 3.06, 1.14–8.24); mining industry/quarries/excavation for attacks of shortness of breath with wheezing (SOBWHZ) (2.41, 1.16–5.02) and AO (2.95, 1.20–7.26); textile industry for asthma (2.61, 1.00–6.79), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (2.56, 1.35–4.85), SOBWHZ (3.09, 1.57–6.06) and wheezing (2.00, 1.00–3.97); wood industry for asthma (3.16, 1.21–8.26); mechanical industry for AO (2.34, 1.06–5.18). Agriculture and mining industry/quarries/excavation were also related to a greater decrease in the FEV1/FVC values. Longitudinal analyses confirm that employment in high-risk sectors, particularly the textile industry, is a significant determinant of respiratory disease incidence and lung function decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In middle- and high-income countries, chronic respiratory diseases, together with other noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cancer and cardiovascular disorders, account for the vast majority of work-related illnesses1. External factors significantly contribute to the onset or worsening of NCDs; among them, workplace exposures deserve to be thoroughly studied for preventing and enhancing lung health1,2.

An official statement by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) reported that occupational exposure contributes substantially to the burden of several chronic respiratory diseases in the general population, with population attributable fractions of 16% for asthma, 14% for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and 13% for chronic bronchitis2.

Indeed, there is strong evidence that exposure to various types of dust, either mineral or biological, as well as fumes, increases the risk of COPD and excess of lung function decline1,2,3,4,5,6. In allergic asthma, both high-molecular-weight (HMW) agents (such as flour, fish, and proteins from animals) and low-molecular-weight (LMW) agents (such as platinum salts, di-isocyanates, and phthalic anhydride) are recognized risk factors1. Asthma can be triggered by exposure to an irritant, a condition known as irritant-induced asthma, but strong evidence suggests that even new-onset asthma can occur after exposure to high levels of irritants or due to long-term occupational exposure1,7,8.

When studying the onset of chronic respiratory diseases, long latency periods are to be considered; in fact, disease outbreak may occur long before the start of symptoms. As a consequence, the findings from case‒control studies may be influenced by reverse causation. On the other hand, prospective cohort studies could enhance the early detection of risk factors1,9. In this context, longitudinal epidemiological surveys on general population samples can provide valuable insights into the incidence of respiratory symptoms/diseases, making it possible to assess their natural history and long-term outcomes after adjusting for individual risk factors9,10,11.

Whitin this framework, the “Big data and deep learning in occupational cancer surveillance system” (BEST) multicenter project was designed. The aim of our work was to assess the associations between occupational exposure and the incidence of respiratory symptoms/diseases and lung function changes across 18 years of follow-up in a general population sample.

Materials and methods

Sample

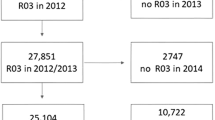

Detailed information on the population characteristics and methods is available elsewhere12. In summary, a multistage stratified family-cluster random sample was utilized to study a general population in Pisa, a city located in the Tuscany region of Italy, across three cross-sectional surveys. The first survey (PI1) took place from 1985 to 1988, the second survey (PI2) from 1991 to 1993, and the third survey (PI3) from 2009 to 2011. Cross-sectional relationships between work exposure to dusts/chemicals/fumes and respiratory symptoms/diseases and lung function impairment have already been demonstrated13. We have now analyzed longitudinal effects on individuals who participated in both PI2 and PI3, with an average follow-up of eighteen years, and who reported at PI2 to be employed or to have previously worked (n = 823).

Methods

Data regarding symptoms/diseases and risk factors were collected through standardized interviewer-administered questionnaires: the one used in PI2 was developed by the National Research Council (CNR) on the basis of the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute questionnaire14,15; the one used in PI3 was developed within the European project “Indicators for Monitoring COPD and Asthma in the EU (IMCA II)”16.

Pre-bronchodilator spirometry was used to measure lung function. In PI2, all individuals aged ≤ 75 years were invited to perform spirometry measurements (forced vital capacity-FVC maneuver) following the ATS protocol17 via a water-sealed spirometer (Baires, Biomedin)18. In PI3, spirometry (FVC maneuver) was performed according to the ATS/ERS protocol19 via a hand-held ultrasonic spirometer (EasyOne Model 2001 Spirometer, NDD Medical Technologies). Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and FVC were analyzed using observed and predicted values, computed using reference equations derived from the same population20. 329 subjects had spirometric values at both baseline and follow-up.

At the time of the PI2 survey, Italian regulations did not require approval from an Ethical Committee. An Internal Review Board within the CNR Preventive Medicine Targeted Project endorsed the protocol. The study protocol, patient information document, and consent forms for the PI3 survey received approval from the Ethics Committee of Pisa University Hospital (Prot. no. 23887, April 16, 2008). The study was carried out in accordance with the fundamental principles of the Helsinki Declaration and informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) prior to participation in the surveys.

Investigated respiratory health outcomes and risk factors

Since different questionnaires were used in PI2 and PI3, only comparable questions were selected for these analyses, as described in the Supplementary Material.

The following self-reported health outcomes were considered: COPD physician diagnosis, asthma physician diagnosis, attacks of shortness of breath with wheezing/whistling (SOBWHZ), wheezing, usual cough/phlegm, and dyspnea grade I+.

Airway obstruction (AO) was derived using two different criteria: (a) the lower limit of the normal (LLN) criterion (AOLLN) (FEV1/FVC percent predicted < LLN)21; (b) Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease criterion (AOGOLD) (FEV1/FVC observed < 70%)22.

For each symptom or diagnosis, the 18-year cumulative incidence value was computed as the proportion of subjects who reported the outcome of interest in PI3 (“incident cases”) to the subjects not reporting it in PI2 (“population at risk”): “cumulative incidence” = “incident cases”/ “population at risk” x 100 (more details are reported in the Supplemental material).

At PI2, subjects were asked to report employment for at least 3 months in specific sectors, without information about the total duration of the employment. The following working sectors deemed at risk for respiratory diseases were considered: agriculture/milling; the mining industry and other similar industries (i.e., stone quarries, road construction, tunnel excavation, cement factories, bricks, glassworks) (“mining industry/quarries/excavation”); the textile industry/grinding; the wood industry; and the mechanical industry. Subjects having worked in these sectors were classified as exposed to “at-risk sector” (i.e., exposed for at least 3 months to substances which are hazardous to the respiratory tract), whereas subjects who had never worked or had worked for less than 3 months in a specific sector were classified as “non-exposed”.

Based on literature evidence, the following baseline (PI2) potentially confounding factors were taken into account in the analyses: sex, age, educational level (≤ 8 years, > 8 years), family history of asthma or chronic bronchitis, smoking habits (smoker, ex-smoker, never-smoker), secondhand smoking, area of residence (urban, suburban), and winter and summer perceived temperature in the last employment (cool/cold, hot/torrid, normal).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 27.0). Comparisons among groups were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Multiple logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between working in the at-risk sector and the cumulative incidence of symptoms/diseases and AO. The models were adjusted for potential confounding factors assessed at baseline (PI2). The odds ratio (OR) and 90% confidence interval (CI) were calculated23. Since we have analyzed the cumulative incidence of respiratory outcomes, OR can be considered as a “cumulative incidence odds ratio”.

Analysis of covariance was used to estimate the effect of the at-risk sector on the longitudinal changes in the observed and percent predicted FEV1/FVC values from PI2 to PI3, adjusting for potential confounding factors at baseline (PI2). The longitudinal changes were computed as Δ%: (PI3 value-PI2 value/PI3 value)*100.

A sensitivity analysis was carried out using only those subjects who had not worked (or had worked for less than 3 months) in any of the predefined high-risk occupational sectors as a reference category. This approach allowed a more specific definition of the unexposed group, although it resulted in a reduced sample size.

Results

The baseline descriptive characteristics are shown in Table 1: 50.8% were females, 38.2% had a family history of respiratory diseases, 70% had a low educational level, approximately 60% were ever smokers and lived in a suburban area, and 56.1% reported secondhand smoke. Approximately 65% of the sample reported that they worked in places with hot/torrid or cool/cold temperatures both in winter and summer (Table 1).

Approximately 7% of the participants had worked for at least 3 months in the agriculture, mining industry/quarries/excavation, or wood industries, 8.5% in the textile industry/grinding and 10.1% in the mechanical industry (Fig. 1).

The eighteen-year follow-up cumulative incidence values for symptoms/diseases were as follows: 3.2%, self-reported asthma physician diagnosis; 7.2%, SOBWHZ; approximately 11%, wheezing, or self-reported COPD physician diagnosis; 15.4%, AOLLN; approximately 23%, usual cough/phlegm or AOGOLD; and 31.6%, dyspnea (Table 2).

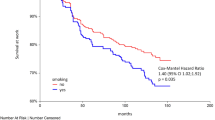

Multiple logistic regression analyses revealed relevant associations among working in the at-risk sector and the incidence of health outcomes: agriculture for usual cough/phlegm (OR 2.16, 90% CI 1.17–3.99) and AOGOLD (OR 3.06, 1.14–8.24); mining industry/quarries/excavation for SOBWHZ (OR 2.41, 1.16–5.02), AOGOLD (OR 2.95, 1.20–7.26) and AOLLN (OR 2.70, 1.06–6.88); textile industry for self-reported asthma physician diagnosis (OR 2.61, 1.00-6.79), self-reported COPD physician diagnosis (OR 2.56, 1.35–4.85), SOBWHZ (OR 3.09, 1.57–6.06) and wheezing (OR 2.00, 1.00-3.97); wood industry for self-reported asthma physician diagnosis (OR 3.16, 1.21–8.26); and mechanical industry for AOGOLD (OR 2.34, 1.06–5.18) and AOLLN (OR 2.47, 1.06–5.77) (Table 3).

Compared with those working in other sectors, those working in agriculture and mining industries/quarries/excavation experienced a greater decline in FEV1/FVC values from baseline to follow-up (Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses, which were carried out considering as reference category subjects who had not worked in any of the predefined high-risk occupational sectors, confirmed the results showing higher ORs related to at-risk sector exposure. In addition, there were new associations: agriculture with self-reported COPD/SOBWHZ and mining industries/quarries/excavation with self-reported COPD. AO did not show relevant associations, probably due to the reduced sample size. No results were shown for asthma because they were considered unreliable because the sample size was too small (Table S1). A greater decrease in FEV1/FVC in subjects working in agriculture was confirmed (Table S2).

Discussion

Over an 18-year follow-up period, exposure to substances hazardous to the respiratory tract for at least three months was associated with the cumulative incidence of respiratory symptoms/diseases and with a greater decline in lung function in a sample of adults of the general population living in an urban/suburban area in Central Italy. These results accounted for major individual risk factors for respiratory disease/symptom onset and were based not only on self-reported information from questionnaires but also on objective measurements.

There was a strong relationship between agriculture and impairment of lung function, evaluated as the AO, reduction in FEV1/FVC values and usual cough/phlegm; moreover, an association was also found for the SOBWHZ. In a sample of Irish farmers, over 60% reported one or more chronic respiratory symptoms (33% cough), and approximately 12% had AO6. A high prevalence of respiratory symptoms and chronic bronchitis in farmers has been reported in other European and US studies24,25; in US farmers, even among never-smokers, symptoms of current cough and phlegm resulted greater than those in the general population25. A possible explanation is long-term exposure to airway irritants and inflammatory response triggers such as endotoxins, fungal spores, organic dust and biological agents6. A recent review revealed associations of FEV1 decline with ever-exposure to fungicides and cumulative exposure to biological dust, fungicides and insecticides3, risks to which individuals employed in the agricultural sector are exposed. In a European study on a general population sample aged 20–44 years, AO incidence was related to biological dust (OR 1.60) and pesticide exposure (OR 2.2) during a 20-yr follow-up (from 1991-1993 to 2010–2012)10. The same study also reported an accelerated decline in FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio with exposure to biological dust11. In a Scottish longitudinal study, lifetime occupational exposure to biocides/fungicides was independently associated with reduced lung function, with a greater decline in FEV1 in exposed subjects than in nonexposed subjects26.

Similarly, the mining industry/quarries/excavation was associated with the incidence of SOBWHZ, AOGOLD, changes in FEV1/FVC values and COPD. Among coal miners and quarrymen, inhaling dust is a significant cause of emphysema and COPD, and the rate of functional decline is comparable between dust inhalation and tobacco smoking4,27. The same result was also found in two large European cohorts, in which an accelerated decline in FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio were associated with exposure to mineral dust, with values comparable in magnitude to losses associated with long-term smoking11. These results confirmed as mining and quarry are traditionally a very high-risk occupation in terms of inducing accelerated decline in the middle-aged men28. Many miners commonly experience multiple effects, which can include bronchitis, interstitial lung disease, and emphysema4. Several cross-sectional surveys carried out by mining companies in Australia between 2001 and 2012 revealed positive associations between inhalable dust exposure and the prevalence of phlegm (OR 1.033) and impaired lung function parameters29. Indeed, mining involves relevant hazards and risks associated with exposure due to different work processes and the generation or use of hazardous substances. Miners, quarrymen and stone workers are commonly exposed to inhalable fibers and dust that can cause respiratory disorders; there is also significant evidence of an increasing effect of total cumulative dust exposure onbreathlessness27,29.

The textile industry was related to COPD diagnosis, SOBWHZ and wheezing incidence. A recent review confirmed that workers in the textile and fashion industry are exposed to cotton dust and other raw materials, fumes, and chemicals from manufacturing processes; all these exposures are related to respiratory effects such as bronchitis, asthma, cough and byssinosis (characterized by chest tightness, coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath)7. A 15-year follow-up study on cotton textile workers was performed in Shanghai, China (1981–1996), which revealed a significant annual reduction in pulmonary function30. A metanalyses showed that exposure to textile dust was associated with asthma (OR 1.50)31.

Associations with AO incidence have also been reported in the mechanical industry, where the use of metal working fluids (MWFs) for cooling and lubricating is one of the main exposures. MWFs are composed of different chemical compounds, e.g., chlorides, phosphates, nitrates, ethanol amines and bioacids: exposed workers may experience related side effects, such as dermal and respiratory disorders and cancer32. In the Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study, subjects exposed to metals presented greater decreases in FEV1 and FVC than unexposed subjects during a 6-yr follow-up5. In a European study on a general population sample aged 20–44, during a 20-yr follow-up (from 1991-1993 to 2010–2012), an accelerated decline in FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio for exposure to metal and mineral dust was found11.

Finally, working in the wood industry was related to asthma. The main exposure in this setting is wood dust produced by equipment or tools employed in wood cutting and treatment. The biological mechanisms that link asthma and rhinitis with wood dust are not fully understood33. Although specific IgE sensitization has been reported in wood workers, Type 1 allergy is not considered a major factor, and only a few workers in the wood industry seem to have sensitization33. A metanalysis of 17 studies showed that organic dust exposure was positively associated with asthma (OR 1.48). The subgroup analyses revealed an OR of 1.62 for paper/wood dust31. A recent umbrella review showed that wood dust exposure was associated with adult-onset asthma8. In a Scottish longitudinal study, lifetime occupational exposure to wood dust was independently associated with adult-onset wheezing (OR 2.08)26.

Overall, our findings align with those of a recent review showing consistent evidence that exposure to various types of dust (both mineral and biological) and fumes, particularly coal mine dust, farming dust (grain), textile dust, vapors, gases, dusts or fumes (VGDF, non-specified) and welding fumes1, are risk factors for COPD or an increase in lung function decline. In the same review, consistent evidence was reported for asthma and wood dust1. Moreover, our two previous papers confirmed the association between lifetime exposure to VGDF at work and respiratory outcomes. Viegi et al. reported, in the 1st cross-sectional Po Delta survey, that VGDF exposure was significantly associated with increased risks for all respiratory symptoms/diseases in men and for asthma symptoms/diagnoses in women; exposed men also had significantly increased risks of abnormal values of FEV1% or FEV1/FVC%13. Maio et al. reported that persistent exposure to VGDF within an 18-yr follow-up increased the probability of incident asthma (OR 4.4) and usual phlegm (OR 1.8); incident exposure to fumes/gases/dusts was related to incident usual phlegm (OR 1.5), usual cough (OR 1.6) and dyspnea (OR 1.9)12.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a questionnaire for gathering information on symptoms/diseases could be influenced by reporting bias, which is dependent on personal recall. Nevertheless, the standardized questionnaire stands out as a primary tool for research in respiratory epidemiology34,35. Moreover, we also applied an objective respiratory outcome (lung function) that was not affected by this potential bias.

Moreover, we should consider that COPD diagnosis was based on the self-reported physician diagnosis, not on spirometric values. Thus, a certain degree of misclassification might have occurred: some subjects with AO might not have had a doctor diagnosis, and a non-negligible percentage of subjects who reported a physician diagnosis might not have met the spirometric criteria18. Despite its limitation, physician-diagnosed COPD continues to be widely used in epidemiological surveys since it is simple and cost-saving, and because it provides a ‘real-life’ picture of the percentage of people in a country that are diagnosed by doctors36.

There were some differences in the questionnaire used in PI3, but only those questions that were either similar or the same as those in PI2 were selected. For PI2 and PI3, spirometry was performed using different devices; a correction factor was established to address this issue and allow for a comparison between the two studies, as previously reported16.

Occupational exposure was considered as having worked for at least 3 months in a sector at risk for respiratory diseases. Unfortunately, we did not have information on the total period of exposure to the at-risk sector, and no objective measurement of exposure was available in our study. Moreover, no information on the specific job title was available for the at-risk sectors. Indeed, previous studies have shown that some specific job title may be more exposed and susceptible to health effects due to occupational exposure: for example, drillers and mill operators compared to other job positions in the mining industry37 or welders and assemblers in the mechanical industry38.

Epidemiological research on work-related illnesses necessitates an evaluation of earlier exposure, which can range from basic categorizations according to the type of job done (for instance, splitting workers into “exposed” and “unexposed” groups), to individual sampling, or to more advanced evaluations that incorporate statistical models to deliver a numerical estimate of exposure tied to each role in the employment history. Regardless of the approach taken, the common goal of historical exposure studies is to provide an estimate of exposure that is as accurate as possible, given the constraints of available resources39. An improved evaluation of occupational exposure might come from the use of job-exposure matrices that allow estimating workers’ exposure to various agents (like chemicals, dust) based on their job titles or industries rather than individual measurements9. Unfortunately, we did not have enough information for applying job-exposure matrices: thus, our models are based exclusively on employment in an at-risk sector.

However, our findings are in line with recent literature, as discussed above, and with our two previous papers12,13 but add further information on the longitudinal relationship between occupational exposure and outcome incidence and lung function reduction.

The choice of control categories defined as never working or working for less than 3 months in a specific sector could have resulted in misclassification bias, defining as non-exposed subjects those who worki in another sector characterized by similar exposures, with a consequently more conservative estimate of the effect. Sensitivity analyses, carried out considering as reference category subjects unexposed to any of the occupational sectors, and thus reducing the misclassification, confirmed the main results and showed higher ORs and new associations, even in a smaller sample with consequently wider confidence intervals. On the other hand, it should be considered that the different reference categories used in the main analyses do not allow for a comparison of odds ratios among sectors in Tables 3 and 4.

The baseline characteristics and health status of subjects who were followed-up (PI2&PI3 participants) and those of subjects who were not (only PI2 participants) were compared in our previous paper, which revealed that the incidence values were computed in a sample of younger healthy subjects, with a possible conservative estimate of the reported incidence values12. This potential conservative estimate occurrence was found by another article indicating that, among long-term participants in population studies, the rates of disease prevalence are generally slightly lower than those of the complete baseline population, implying that individuals who remain in a study tend to be healthier than those who withdraw40.

A strength of our population-based study is that, over an eighteen-year follow-up, a similar study design, sampling method and study protocol were used in two cross-sectional surveys involving general population groups living in the same area. Additionally, we examined a general population sample that ranged from early to late adulthood (elderly people), using both qualitative and quantitative individual data. The longitudinal approach warranted to fill in important knowledge gaps regarding exposure–response relationships, overcoming the important limitations of cross-sectional studies in which knowledge of disease diagnosis may affect the reporting of exposure.

Another aspect that deserves to be highlighted is the assessment of AO according to the GOLD and LLN criteria. Our choice to use both criteria stems from the long-standing debate over the validity and usability of these two criteria. The GOLD criterion is simple and independent of reference values, since it relates to observed variables. It is easy to be applied in clinical practice and facilitates international standardization and comparison across studies. However, its main limitation lies in the fact that FEV1/FVC ratio naturally declines with age. Therefore, GOLD criterion tends to overdiagnose obstruction in elderly individuals and underdiagnose it in younger patients41,42. In contrast, the LLN criterion is based on the normal distribution and classify the bottom 5% of the healthy population as abnormal. Thus, LLN is highly dependent on the choice of reference equations. This approach better reflects the physiological variability within the population and reduces the risk of age-related misclassification. Nevertheless, its application requires access to appropriate reference values and computational tools41.

Finally, notably, throughout Europe, significant changes have occurred in the primary sources of workplace exposure. This transition moved away from substantial exposure to mineral dust early in the 20th century within large, centralized industries, such as coal and silica dust in mining and metal manufacturing. Currently, the focus has shifted to lower-level allergens, such as flour and enzymes in bakeries and food production, along with irritants, such as cleaning products. This evolution has consequently resulted in considerable changes in the prevalence of related respiratory illnesses in recent years43.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this longitudinal analytical survey showed that working in a sector at risk for respiratory diseases, particularly the textile industry, is a key determinant of the incidence of respiratory symptoms/diseases and bronchial obstruction. Occupational exposure remains an important and preventable contributor to the global burden of chronic respiratory diseases, including COPD and asthma. These findings emphasize the need for increased clinical awareness and public education regarding the role of work-related factors in non-malignant respiratory disease. Greater attention should be directed toward reducing this occupational disease burden by identifying at-risk individuals and implementing effective prevention strategies in the workplace2.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Peters, S. et al. Narrative review of occupational exposures and noncommunicable diseases. Ann. Work Expo Health. 68 (6), 562–580 (2024).

Blanc, P. D. et al. The occupational burden of nonmalignant respiratory diseases. An official American thoracic society and European respiratory society statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 199 (11), 1312–1334 (2019).

Rabbani, G. et al. Ever and cumulative occupational exposure and lung function decline in longitudinal population-based studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 80 (1), 51–60 (2023).

Petsonk, E. L., Rose, C. & Cohen, R. Coal mine dust lung disease. New lessons from old exposure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187 (11), 1178–1185 (2013).

Alif, S. M. et al. Occupational exposure to solvents and lung function decline: A population based study. Thorax 74 (7), 650–658 (2019).

Cushen, B. et al. High prevalence of obstructive lung disease in non-smoking farmers: The Irish farmers lung health study. Respir Med. 115, 13–19 (2016).

Seidu, R. K. et al. A systematic review of work-related health problems of factory workers in the textile and fashion industry. J. Occup. Health. 66 (1), uiae007 (2024).

Holtjer, J. C. S. et al. P4O2 consortium. Identifying risk factors for COPD and adult-onset asthma: An umbrella review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 32 (168), 230009 (2023).

Murgia, N. & Gambelunghe, A. Occupational COPD-The most under-recognized occupational lung disease? Respirology 27 (6), 399–410 (2022).

Lytras, T. et al. Occupational exposures and 20-year incidence of COPD: The European community respiratory health survey. Thorax 73 (11), 1008–1015 (2018).

Lytras, T. et al. Cumulative occupational exposures and lung-function decline in two large general-population cohorts. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 18 (2), 238–246 (2021).

Maio, S. et al. 18-yr cumulative incidence of respiratory/allergic symptoms/diseases and risk factors in the Pisa epidemiological study. Respir Med. 158, 33–41 (2019).

Viegi, G. et al. Respiratory effects of occupational exposure in a general population sample in North Italy. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 143 (3), 510–515 (1991).

Viegi, G. et al. Prevalence rates of respiratory symptoms in Italian general population samples exposed to different levels of air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect. 94, 95–99 (1991).

US Department of Health Education and Welfare. In Proceedings of the First NHLBI Epidemiology Workshop (US Government Printing Office, 1971).

Maio, S. et al. Respiratory symptoms/diseases prevalence is still increasing: A 25-yr population study. Respir Med. 110, 58–65 (2016).

Statement of the American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry: 1987 update. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 136 (5), 1285–1298 (1987).

Viegi, G. et al. The proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease in the Italian general population. Chest 126 (4), 1093–1101 (2004).

Miller, M. R. et al. ATS/ERS task force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 26 (2), 319–338 (2005).

Pistelli, F. et al. Reference equations for spirometry from a general population sample in central Italy. Respir Med. 101 (4), 814–825 (2007).

Pellegrino, R. et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 26 (5), 948–968 (2005).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD: 2024 Report. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

Sterne, J. A. & Davey Smith, G. Sifting the evidence-what’s wrong with significance tests? BMJ 322(7280), 226–231 (2001).

Monsó, E. et al. Respiratory symptoms of obstructive lung disease in European crop farmers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162 (4 Pt 1), 1246–1250 (2000).

Hoppin, J. A. et al. Respiratory disease in United States farmers. Occup. Environ. Med. 71 (7), 484–491 (2014).

Tagiyeva, N. et al. Occupational exposure to asthmagens and adult onset wheeze and lung function in people who did not have childhood wheeze: A 50-year cohort study. Environ. Int. 94, 60–68 (2016).

Carder, M. et al. Chest physician-reported, work-related, long-latency respiratory disease in great Britain. Eur. Respir. J. 50 (6), 1700961 (2017).

Vinnikov, D., Brimkulov, N. & Redding-Jones, R. Four-year prospective study of lung function in workers in a high altitude (4000 m) mine. High. Alt. Med. Biol. 12 (1), 65–69 (2011).

Rumchev, K., Van Hoang, D. & Lee, A. H. Exposure to dust and respiratory health among Australian miners. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 96 (3), 355–363 (2023).

Christiani, D. C. et al. Longitudinal changes in pulmonary function and respiratory symptoms in cotton textile workers. A 15-yr follow-up study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163 (4), 847–853 (2001).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between organic dust exposure and Adult-Asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 11 (6), 818–829 (2019).

Andani, A. M., Golbabaei, F., Shahtaheri, S. J. & Foroushani, A. R. Evaluating workers’ exposure to metalworking fluids and effective factors in their dispersion in a car manufacturing factory. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 20 (2), 273–280 (2014).

Baatjies, R., Chamba, P. & Jeebhay, M. F. Wood dust and asthma. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 23 (2), 76–84 (2023).

Bakke, P. S. et al. European respiratory society task force. Recommendations for epidemiological studies on COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 38 (6), 1261–1277 (2011).

Pistelli, F. & Maio, S. Questionnaires and lung function. In: I. Annesi-Maesano, B. Lundback, G. Viegi (Eds.) Respiratory Epidemiology. Eur Respir. Monograph., vol. 65, 257–272 (Sheffield (UK), 2014).

de Marco, R. et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLoS ONE. 8, e62985 (2013).

Vinnikov, D. Drillers and mill operators in an open-pit gold mine are at risk for impaired lung function. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 11, 27 (2016).

Vinnikov, D., Tulekov, Z. & Blanc, P. D. Fractional exhaled NO in a metalworking occupational cohort. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 95 (3), 701–708 (2022).

Borghi, F. et al. Retrospective exposure assessment methods used in occupational human health risk assessment: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (17), 6190 (2020).

Johannessen, A. et al. Longterm follow-up in European respiratory health studies: Patterns and implications. BMC Pulm Med. 14, 63 (2014).

Agustí, A. et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 207 (7), 819–837 (2023).

Viegi, G. et al. Prevalence of airways obstruction in a general population: European respiratory society vs American thoracic society definition. Chest 117 (5 Suppl 2), 339S–45S (2000).

De Matteis, S. et al. European respiratory society environment and health Committee. Current and new challenges in occupational lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 26 (146), 170080 (2017).

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Workers’ Compensation Authority (INAIL) within the BEST project (project No. 56/2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM acted as guarantor of the manuscript; SM, CG, AB, DC and GV contributed to the conceptualization of the work; SM, GS, IS, ST, SB, GV contributed to the methodology and validation; SM, GS, AA, SB contributed to the investigation and data curation; SM and AA performed the formal analysis; SB and GV contributed to the supervision; SM, AB and DC contributed to the funding acquisition. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SM and GS, AA, IS, ST, MMR, StM, CG, AB, DC, GV, SB commented and approved the submitted versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human ethics and consent to participate

At the time of the PI2 survey, Italian regulations did not require approval from an Ethical Committee. An Internal Review Board within the CNR Preventive Medicine Targeted Project endorsed the protocol. The study protocol, patient information document, and consent forms for the PI3 survey received approval from the Ethics Committee of Pisa University Hospital (Prot. no. 23887, April 16, 2008). The study was carried out in accordance with the fundamental principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maio, S., Sarno, G., Angino, A. et al. 18-yr cumulative incidence of respiratory outcomes is related to employment sectors in a general population sample. Sci Rep 15, 42887 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26922-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26922-0